| Revision as of 15:02, 15 August 2013 editCentpacrr (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users24,219 edits add BART← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:33, 11 January 2025 edit undo165.124.85.114 (talk) →Freight railroads: Fixed typo in unit of ton-miles | ||

| (431 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{train topics}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=November 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox rail network | |||

| | name = Rail transport in the United States | |||

| | color = | |||

| | logo = | |||

| | image = CSX 5349 GE ES44DC.jpg | |||

| | caption = A ] train at a ] in ] | |||

| | nationalrailway = | |||

| | infrastructure = | |||

| | majoroperators = ]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />] | |||

| | ridership = 549,631,632<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.transtats.bts.gov/osea/seasonaladjustment/?PageVar=RAIL_PM|title=Seasonally Adjusted Transportation Data|publisher=Bureau of Transportation Statistics|location=Washington, D.C.|date=2017|access-date=September 8, 2017|archive-date=April 22, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210422132507/https://www.transtats.bts.gov/osea/seasonaladjustment/?PageVar=RAIL_PM|url-status=dead}}</ref><br />29 million (Amtrak only)<ref name=UICRS>{{cite web|url=https://www.uitp.org/sites/default/files/cck-focus-papers-files/Regional%20and%20Suburban%20Railways%20Market%20Analysis.pdf|title=Railway Statistics – 2014 Synopsis|publisher=International Union of Railways, IUC|location=Paris, France|date=2014|access-date=September 9, 2015}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> (2014) | |||

| | passkm = 10.3 billion<ref name="UICRS" /> (2014) | |||

| | freight = 1.71 trillion ]<ref name="UICRS" /> (2014) | |||

| | length = {{convert|160141|mile|km|abbr=on}} | |||

| | doublelength = | |||

| | ellength = | |||

| | freightlength = | |||

| | hslength = | |||

| | gauge = {{RailGauge|standard|al=on|allk=on}} | |||

| | hsgauge = | |||

| | gauge1 = | |||

| | gauge1length = | |||

| | el = | |||

| | el1 = | |||

| | el1length = | |||

| | el2 = | |||

| | el2length = | |||

| | notunnels = | |||

| | tunnellength = | |||

| | longesttunnel = ], {{Convert|7.8|mi|km}} | |||

| | nobridges = | |||

| | longestbridge = | |||

| | nostations = | |||

| | highelevation = | |||

| | highelat = | |||

| | lowelevation = | |||

| | lowelat = | |||

| | map = ] | |||

| | mapcaption = ]s with ] and ] ] ports | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Rail transportation in the United States''' consists primarily of ] along a well integrated network of ] private freight railroads that also extend into ] and ]. The United States has the ] of any country in the world, about {{Convert|160000|mi|km}}. | |||

| ] is a ] option for Americans with ] in most major American cities, especially on the ]. Intercity passenger service was once a large and vital part of the nation's passenger transportation network, but passenger service shrank in the 20th century as ] and the ] made commercial air and road transport a practical option throughout the United States. | |||

| The U.S. rail industry has experienced repeated convulsions due to changing U.S. economic needs and the rise of automobile, bus, and air transport. | |||

| The nation's earliest railroads were built in the 1820s and 1830s, ] and the ]. The ], chartered in 1827, was the nation's first common-carrier railroad. By 1850, an extensive railroad network had taken shape in the rapidly industrializing ] and the Midwest, while fewer railroads were built in the ], which was more agricultural than other regions. During and after the ], the ] was built, to join ] with the rest of the national network, at a connection in ]. | |||

| The sole intercity ] in the continental United States today is ]. ] systems exist in more than a dozen metropolitan areas, but these systems are not extensively interconnected, so commuter rail cannot be used alone to traverse the country. ] have been proposed in approximately two dozen other cities, but interplays between various local-government administrative bottlenecks and ripple effects from the ] have generally pushed such projects farther and farther into a nebulous future point in time, or have even sometimes mothballed them entirely. | |||

| Railroads expanded throughout the rest of the 19th century, eventually reaching nearly every corner of the nation. The railroads were temporarily ]d between 1917 and 1920 by the ], because of American entry into ]. Railroad mileage peaked at this time. Railroads were affected deeply by the ], and some lines were abandoned. A great increase in traffic during ] brought a reprieve, but after the war railroads faced intense competition from ] and ] and began a long decline. Passenger service was especially hard hit; in 1971 the federal government created ], to take over responsibility for intercity passenger travel. Numerous railroad companies went bankrupt starting in the 1960s, most notably ] in 1971, in the largest bankruptcy in the nation's history at the time. Once again, the federal government intervened, forming ], in 1976, to assume control of bankrupt railroads in the northeast. | |||

| The most culturally notable and physically evident exception to the general lack of significant passenger rail transport in the U.S. has been, and continues to be, the ], which connects ] and ] with ] and, jutting from those northern points, also other areas of ] and ]. The corridor handles frequent train service that is both Amtrak and commuter. Meanwhile, ] itself is noteworthy for high usage of passenger rail transport, meaning not just the ] system (which counts more as a short-haul ] despite its fairly extensive network and relatively long lines) but also the ], the ] extending into ], and links through the ] system to the Philadelphia-based ] trains to points as far south as ]. The New York City Subway system is used by one third of all U.S. ] users. | |||

| Railroads' fortunes changed after the passage of the ] (1980), which ] railroad companies, who had previously faced much stronger regulation than other modes of transportation. With innovations such as ] and ], railroad traffic increased. After the Staggers Act, many railroads merged, forming major systems, such as ] and ], in the Eastern United States, and ], in the Western United States; ] also purchased some competitors. Another result of the Staggers Act was the rise of ]s, which formed to operate lines that major railroads had abandoned or sold off. Hundreds of these companies were formed by the end of the century. Freight railroads invested in modernization and greater capacity as they entered the 21st century, and intermodal transport continued to grow, while traditional traffic, such as coal, fell. | |||

| Other major cities with substantial rail infrastructure include ], with its ] (nicknamed the "T") rapid transit, light rail, and commuter rail networks, ], with its ] and regional passenger rail system ], and the San Francisco Bay area with ], the Bay Area Rapid Transit system. The commuter rail systems of ] and ] in ], ] and ], meet each other in ], which is a terminus for both systems. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Despite the difficulties outside the systems mentioned, U.S. railroads still play a major role in the nation's freight shipping. They carried 750 billion ton-miles by 1975 which doubled to 1.5 trillion ton-miles in 2005.<ref name="BTS1">U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Washington, D.C. (2000) ''The Changing Face of Transportation.'' Report No. BTS00-007.</ref><ref>National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. ''America on the Move.''</ref> In the 1950s, the U.S. and Europe moved roughly the same percentage of freight by rail; but, by 2000, the share of U.S. rail freight was 38% while in Europe only 8% of freight traveled by rail.<ref>{{dead link|date=October 2010}}</ref> In 1997, while U.S. trains moved 2,165 billion ton-kilometers of freight, the 15-nation ] moved only 238 billion ton-kilometers of freight.<ref>{{dead link|date=October 2010}}</ref> | |||

| {{Further|History of rail transportation in the United States}} | |||

| ===19th century=== | |||

| {{Further|Oldest railroads in North America}} | |||

| ], {{Circa|1826}}]] | |||

| ], built in 1834, is still in use today on the ].]] | |||

| Between 1762 and 1764 a ] (]) (]) was built by British Army engineers up the steep riverside terrain near the ] waterfall's ] at the ] in ].<ref name=PMat-text>, accessdate=2017-03-01</ref> | |||

| Between the 1820s and 1840s, Americans closely watched ]. There, the main competition came from canals, many of which operated under state ownership and from privately owned steamboats plying the nation's vast river system. In 1829, Massachusetts prepared an elaborate rail plan. Government support, most especially the detailing of officers from the ] – the nation's only source of civil engineering expertise – was crucial in assisting private enterprise in building nearly all the country's railroads. Army Engineer officers surveyed and selected routes, planned, designed, and constructed rights-of-way, track, and structures, and introduced the Army's system of reports and accountability to the railroad companies. More than one in ten of the then 1,058 graduates from the ] at West Point between 1802 and 1866 became corporate presidents, chief engineers, treasurers, superintendents and general managers of railroad companies.<ref name="Smith">{{cite book |title=Military Enterprise and Technological Change |last=Smith |first=Merritt Roe |year=1985 |publisher=MIT Press |location=Cambridge, MA |isbn = 0-262-19239-X |pages=87–116 }}</ref> Among the Army officers who thus assisted the building and managing of the first American railroads were ], ], and ].{{need citation|date=March 2024}} | |||

| Railroad companies in the United States are generally separated into three categories based on their annual revenues: ] for freight railroads with annual operating revenues above $346.8 million (2006 dollars), ] for freight railroads with revenues between $27.8 million and $346.7 million in 2000 dollars, and ] for all other freight revenues. These classifications are set by the ]. | |||

| State governments granted charters that created the business corporation and gave a limited right of ], allowing the railroad to buy needed land, even over the owner's objections.{{NoteTag|Horse-drawn rail lines were in use for short-distance hauling of stone. See ]. Other purpose-built railroads were operating in the 1820s. The ], which later became the ], built its first tracks in 1826 as a gravity railroad in ], to haul coal from a mine to the canal at ].}} | |||

| In 1900 there were 132 Class I railroads. Today, as the result of mergers, bankruptcies, and major changes in the regulatory definition of "Class I," there are only seven railroads operating in the United States that meet the criteria for Class I. {{As of|2011}}, U.S. freight railroads operated 139,679 route-miles (224,792 km) of ] in the United States. The present and future of the US railroad system is mapped out in released by the ], and will involve ] and ]. | |||

| The ] (B&O) was chartered in 1827 to build a steam railroad west from ], Maryland, to a point on the ] and began scheduled freight service over its first section on May 24, 1830. The first railroad to carry passengers, and, by accident, the first tourist railroad, began operating in 1827. Named the ], initially a gravity road feeding anthracite coal downhill to the ], using mule-power to return nine miles up the mountain; but, by the summer of 1829, as newspapers documented, it regularly carried passengers. In 1843, renamed the ], it added a steam powered cable-return track for true two-way operation and ran as a ] and tourist road from the 1890s to 1937. Lasting 111 years, the SH&MC is described by some to be the world's first ].{{NoteTag|The SH&MCsbRR carried sundries, groceries, and goods up to Summit Hill, including official postal deliveries.|name = SH&MCsbRR }} | |||

| The first purpose-built common carrier railroad in the northeast was the ]; incorporated in 1826. It began operating in August 1831. Soon, a second passenger line, the ], started service in June 1832.<ref name="Stevens">{{cite book |title = The Beginnings of the New York Central Railroad: A History |last = Stevens |first = Frank Walker |year = 1926 |publisher = G. P. Putnam's Sons |location=New York, NY |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=EYbVAAAAMAAJ }}</ref>{{rp|1–115}} | |||

| Although ] qualifies for Class I status under the revenue criteria, it is not considered a Class I railroad because it is not a freight railroad. | |||

| In 1835, the B&O completed a branch from Baltimore southward to Washington, D.C.<ref name="Dilts">{{cite book |title = The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828–1853 |last=Dilts |first = James D. |year=1996 |publisher=Stanford University Press |location = Palo Alto, CA |isbn = 978-0-8047-2629-0 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=JjrCWPwvHzIC }}</ref>{{rp|157}} The ] was incorporated in 1831 to build a railroad between ] and ]; the road was completed in 1835 with the completion of the ] in ].{{citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| Numerous short lines were built, especially in the south, to provide connections to the river systems and the river boats common to the era. In ], the ], a {{convert|5|mi|km|adj=on}} route connecting the ] with ] at New Orleans was completed in 1831 and provided over a century of operation. Completed in 1830, the ] became the first railroad constructed west of the ]; it connected the ] cities of ] and ].{{citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| ] network from 2006.]] | |||

| __TOC__ | |||

| Soon, other roads that would themselves be purchased or merged into larger entities, were formed. The ] (C&A), the first railroad built in ], completed its route between its namesake cities in 1834. The C&A ran successfully for decades connecting ] to the ], and would eventually become part of the ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Further|History of rail transport in the United States}} | |||

| By 1850, over {{convert|9000|mi|km}} of railroad lines had been built.<ref name="Wilson">{{cite book |last=van Oss |first=Salomon Frederik|title=American Railroads and British Investors |url=https://archive.org/details/americanrailroad00vanorich|year=1893 |publisher=Effingham Wilson & Co |location=London|page=}}</ref> The B&O's westward route reached the Ohio River in 1852, the first eastern seaboard railroad to do so.<ref name=Stover>{{cite book | last = Stover | first = John F. | title = History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad | publisher = ] | year = 1987 | location = West Lafayette, Ind. | pages = 59–60| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=IEPCqQErPHAC&pg=PP1| isbn =0-911198-81-4 }}</ref>{{rp|Ch.V}} Railroad companies in the North and Midwest constructed networks that linked nearly every major city by 1860. | |||

| ===1826–1850=== | |||

| ], New York]] | |||

| During this period, Americans watched closely the development of railways in England. The main competition came from canals, many of which were in operation under state ownership, and from privately owned steamboats plying the nation's vast river system. The state of Massachusetts in 1829 prepared an elaborate plan. Government support, most especially the detailing of officers from the Army Corps of Engineers - the nation's only repository of civil engineering expertise - was crucial in assisting private enterprise in building nearly all the country's railroads. Army Engineer officers surveyed and selected routes, planned, designed, and constructed rights of way, track, and structures, and introduced the Army's system of reports and accountability to the railroad companies. More than one in ten of the 1,058 graduates from the ] at West Point between 1802 and 1866 became corporate presidents, chief engineers, treasurers, superintendents and general managers of railroad companies.<ref name="Smith">{{cite book |title=Military Enterprise and Technological Change|last=Smith |first=Merritt Roe |year=1985 |publisher=MIT Press |location=Cambridge, Mass. |isbn=0-262-19239-X |pages=87–116}}</ref> Among the Army officers who thus assisted the building and managing of the first American railroads were ], ], and ]. | |||

| Large railroad companies, including the ], ], and the ], spanned several states. In response to ] practices, such as ] and other excesses of some railroads and their owners, ] created the ] (ICC) in 1887. The ICC indirectly controlled the business activities of the railroads through issuance of extensive ]. Congress also enacted ] to prevent railroad monopolies, beginning with the ] in 1890. Industrialists such as ] and ] became wealthy through railroad ownerships.{{citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| State governments granted charters that created the business corporation and gave a limited right of ], allowing the railroad to buy needed land, even if the owner objected.<ref>Horse-drawn rail lines were in use for short-distance hauling of stone. See ]. Other purpose-built railroads were operating in the 1820s. The ], which later became the ], built its first tracks in 1826 as a gravity railroad in ], to haul coal from a mine to the canal at ].</ref> The ] (B&O) was chartered in 1827 to build a steam railroad west from ], ] to a point on the ]. Scheduled service on its first section started on May 24, 1830. The first common carrier railroad in the northeast was the ], first incorporated in 1826, which began operating in August, 1831. A second railroad, the ], opened the next year, in June, 1832.<ref name="Stevens">{{cite book |title=The Beginnings of the New York Central Railroad: A History |last=Stevens |first=Frank Walker |authorlink= |year=1926 |publisher=G.P. Putnam's Sons |location=New York, NY |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=EYbVAAAAMAAJ |accessdate=}}</ref>{{rp|1-115}} In 1835 the Baltimore & Ohio completed a branch from Baltimore southward to ]<ref name="Dilts">{{cite book |title=The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828-1853 |last=Dilts |first=James D. |authorlink= |year=1996 |publisher=Stanford University Press |location=Palo Alto, CA |isbn=978-0-8047-2629-0 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=JjrCWPwvHzIC |accessdate=}}</ref>{{rp|157}} The ] was incorporated in 1831 to build a railroad between ], ] and ], ]; the road was completed in 1835 with the completion of the ]. | |||

| Numerous short lines were built, especially in the south, to provide connections to the river system. From 1829-1830, the ], the first railroad constructed west of the ], was built connecting the two ] cities of ] and ]. The ], a {{convert|5|mi|km|sing=on}} route connecting the ] with ] at ], ] was completed in 1831, starting over a century of operation. | |||

| Soon, other roads that would themselves be purchased or merged into larger entities, formed. The ] (C&A), the first railroad built in ], completed its route between its namesake cities in 1834. The C&A eventually became part of the ]. | |||

| ===1851–1900=== | |||

| By 1850, {{convert|9000|mi|km}} of railroad lines had been built.<ref name="Wilson">{{cite book |last=van Oss |first=Salomon Frederik |authorlink= |title=American Railroads and British Investors |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=XjMJAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA3#v=onepage&q&f=false |year=1893 |publisher=Effingham Wilson & Co |location=London |isbn= |page=3}}</ref> The B&O's westward route reached the Ohio River in 1852, the first eastern seaboard railroad to do so.<ref name=Stover>{{cite book | last = Stover | first = John F. | authorlink = | title = History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad | publisher = ] | year = 1987 | location = West Lafayette, Ind. | pages = 59–60 | |||

| | url = http://books.google.com/?id=IEPCqQErPHAC&pg=PP1&dq=History+of+the+Baltimore+and+Ohio+Railroad#v=onepage&q= | doi = | id = | isbn =0-911198-81-4 }}</ref>{{rp|Ch.V}} Railroad companies in the North and Midwest constructed networks that linked nearly every major city by 1860. | |||

| ====Transcontinental railroad==== | ====Transcontinental railroad==== | ||

| {{Main|First Transcontinental Railroad}} | {{Main|First Transcontinental Railroad}} | ||

| ] | ] in May 1869]] | ||

| The First Transcontinental Railroad in the U.S. was built in the 1860s, linking the railroad network of the eastern U.S. with California on the ] coast. Completed on May 10, 1869, at the ] event at ], it created a nationwide mechanized transportation network that revolutionized the population and economy of the ], catalyzing the transition from the ]s of previous decades to a modern transportation system. It was the first transcontinental railroad by connecting myriad eastern U.S. railroads to the Pacific Ocean. However it was not the world's longest railroad, as ]'s ] (GTR) had, by 1867, already accumulated more than {{convert|2055|km|mi}} of track by connecting ], and the three northern ] states with the ], and west as far as ], through ]. | |||

| Authorized by the ] of 1862 and heavily backed by the ], the first transcontinental railroad was the culmination of a decades-long movement to build such a line and was one of the crowning achievements of the presidency of ], completed five years after his death. The building of the railroad required enormous feats of engineering and ] in the crossing of the ] and the ] by the westbound ] (UP) and eastbound ], the two federally chartered enterprises that built the line.<ref> 12 Stat. 489, July 1, 1862</ref> The building of the railroad was motivated in part to bind the ] together following the strife of the ]. It substantially accelerated the populating of the West by ]s, leading to rapid ] of new farm lands. The Central Pacific and the ] combined operations in 1870 and formally merged in 1885; the Union Pacific originally bought the Southern Pacific in 1901 and was forced to divest it in 1913, but took it over again in 1996. | |||

| The First Transcontinental Railroad in the ] was built across ] in the 1860s, linking the ] network of the eastern U.S. with ] on the ] coast. Finished on May 10, 1869 at the famous ] event at ], it created a nationwide mechanized transportation network that revolutionized the population and economy of the ], catalyzing the transition from the ]s of previous decades to a modern transportation system. Although an accomplishment, it achieved the status of first transcontinental railroad by connecting myriad eastern US railroads to the Pacific. However it was not the world's longest railroad, as the Canadian ] (GTR) had, by 1867, already accumulated more than {{convert|2055|km|mi}} of track by connecting Portland, Maine, and the three northern New England states with the Canadian Atlantic provinces, and west as far as Port Huron, Michigan, through Sarnia, Ontario. | |||

| Much of the original ] is still in use today and owned by UP, which is descended from both of the original railroads.{{citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| ], in 1869.]] | |||

| Authorized by the ] of 1862 and heavily backed by the ], the first transcontinental railroad was the culmination of a decades-long movement to build such a line and was one of the crowning achievements of the presidency of ], completed four years after his death. The building of the railroad required enormous feats of ] and ] in the crossing of plains and high mountains by the ] and ], the two federally chartered enterprises that built the line westward and eastward respectively.<ref> 12 Stat. 489, July 1, 1862</ref> The building of the railroad was motivated in part to bind the ] together during the strife of the ]. It substantially accelerated the populating of the West by white ]s, led to rapid ] of new farm lands. The Central Pacific and the ] combined operations in 1870 and formally merged in 1885; the Union Pacific originally bought the Southern Pacific in 1901 and was forced to divest it in 1913, but finally took it over for good in 1996. | |||

| Much of the original ] is still in use today and owned by the modern ], which is descended from both of the original railroads. | |||

| ====Rail gauge selection==== | ====Rail gauge selection==== | ||

| {{Main|Track gauge in the United States}} | |||

| Many Canadian and United States railroads originally used various broad gauges, but most were converted to {{RailGauge|56.5}} by 1886, when the conversion of much of the southern rail network from {{convert|5|ft|mm|0|abbr=on}} gauge took place, see ]. This and the standardization of couplings and air brakes enabled the pooling and interchange of ]s and rolling stock. ''See'' ]. | |||

| ] at Cape Horn, California, {{Circa|1880}}]] | |||

| ====Impact of railroads on the economy==== | ====Impact of railroads on the economy==== | ||

| {| class="wikitable sortable floatright" | |||

| The railroad had its largest impact on the American transportation system during the second half of the 19th century. It is the conventional historical view that the railroads were indispensable to the development of a national market in the United States in the late 19th century. | |||

| |+ '''Railroad mileage increase by groups of states'''<br /><small>Source: ] (ed.), ''One Hundred Years of American Commerce 1795–1895'' p 111</small> | |||

| =====Conventional view===== | |||

| In his Rostovian Take-off Thesis, ] was one of the first economic historians to propose and justify the conventional view that railroads were crucial to American economic growth. According to Rostow, railroads were responsible for the “take-off” of American industrialization in the period of 1843-1860. This “take-off” in economic growth occurred because the railroad helped to decrease transportation costs, transport new products and goods to commercial markets, and generally widen the market.<ref name = "Rostow" > Rostow, Walt W. (1960). The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 55.</ref> Furthermore, the development of railroads stimulated the growth of the modern coal, iron, and engineering industries, all of which were essential for wider economic growth.<ref name = "Rostow" /> According to Rostow’s Take-off Thesis, railroads generated new investment, which simultaneously helped develop financial markets in the United States. Like Rostow, American economic historian Leland Jenks (having conducted an analysis based on ]'s theory of innovation) similarly claims that railroads had a direct impact on the growth of the United States’ real income and an indirect impact on its economic expansion.<ref> Jenks, Leland H. (1944). "Railroads as an Economic Force in American Development.” Journal of Economic History 4, no. 1. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 11. </ref> | |||

| Contemporary American economic historians have challenged this conventional view. The respective findings of ] and Albert Fishlow do not support Rostow’s claim that railroads stimulated widespread industrialization by increasing demand for coal, iron, and machinery. Drawing upon historical data, Robert Fogel found that the impact of railroads on the iron and steel industries was minimal: from 1840 to 1860, railroad production used less than five percent of the total pig iron produced. In addition, Fogel argues, only six percent of total coal production from 1840 to 1860 was consumed by railroads through consumption of iron products.<ref> Fogel, Robert W. (1971), Railroads and American Economic Growth. ed. Stanley L. Engerman and Robert W. Fogel. New York: Harper Row. pp. 201.</ref> Like Fogel, Fishlow showed that most railroads used very little coal during this time period because they were able to burn wood instead.<ref name = "Fishlow" >Fishlow, Albert (1965). American Railroads and the Transformation of the Ante-Bellum Economy Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 14-157.</ref> Fishlow also found that iron used by railroads was only 20% of net consumption in the 1850s.<ref name = "Fishlow" /> | |||

| =====Robert Fogel===== | |||

| Fogel concludes that railroads were important but not essential to late 19th century growth in the United States. To conduct his analysis, Fogel measures the “social saving” created by railroads, which he defines as the difference between the actual level of national income in 1890 and the theoretical level of national income if transportation adjusted in the most efficient way possible to the absence of the railroad.<ref name = "Fogel"> Fogel, Robert W. (1962). "A Quantitative Approach to the Study of Railroads in American Economic Growth: A Report of Some Preliminary Findings." The Journal of Economic History 22, no. 2. pp. 20-21.</ref> He found that without the railroad, America’s gross national product (GNP) would have been 7.2% less in 1890. While the largest contribution to GNP growth made by any single innovation before 1900, this percentage only represents 2–3 years of GNP growth.<ref name = "Fogel" /> | |||

| Fogel makes several key assumptions and decisions in his analysis. First, his calculations comprise transportation between the primary markets of the Midwest and the secondary markets of the East and South (interregional) and transportation between cities and rural areas (intraregional). Second, he chooses to focus on the shipment of four agricultural commodities: wheat, corn, beef, and pork. Third, Fogel’s social saving calculation accounts for costs not included in water rates (which include the cargo losses in transit, transshipment costs, extra wagon haulage, time lost because of slower speed and because canals froze in the winter, and capital costs). One criticism of Fogel’s analysis is that it does not account for the externalities or "spill-over" effects of the railroads, which (if included) may have increased his estimate for social savings. Railroads provided much of the demand for the technological advances in a number of areas, including heat dynamics, combustion engineering, thermodynamics, metallurgy, civil engineering, machining, and metal fabrication. Furthermore, Fogel does not discuss the role railroads played in the development of the financial system or in attracting foreign capital, which otherwise might not have been available. | |||

| =====Albert Fishlow===== | |||

| Fishlow estimates that the railroad’s social savings—or what he terms “direct benefits”—were higher than those calculated by Fogel. Fishlow’s research may indicate that the development of railroads significantly influenced real income in the United States. Instead of Fogel’s term “social saving,” Fishlow uses the term “direct benefits” to describe the difference between the actual level of national income in 1859 and the theoretical level of income using the least expensive, but existing alternative means.<ref name = "Fishlow" /> Fishlow calculated the social savings in 1859 at 4 percent of GNP and in 1890 at 15 percent of GNP—higher than Fogel’s estimate of 7.2% in 1890.<ref> Majewski, John (2006). "American Railroads and the Transformation of the Ante-bellum Economy." Accessed February 27, 2013. http://eh.net/node/2735.</ref> | |||

| =====Differences in methodology===== | |||

| The difference in the approximations of the two theorists can be attributed to the different definitions of social saving. Fishlow compares railroads to the existing alternatives at the time, while Fogel compares railroads to an efficient network of transportation that he predicts would have been built in the absence of railroads. Fishlow notes that railroads had the biggest positive impact on agriculture because they made possible the building of new farms and the growth of towns and cities, which in turn managed a growing food and cattle surplus. Therefore, while Fogel’s analysis focuses on the development that would have occurred without railroads, Fishlow’s analysis focuses on the impact of railroads on the economy at that time. These impacts include the lowering of freight and passage costs, “backward linkages” that stimulated economic development by creating demand for construction and machinery, and the “forward linkages” that widened markets for raw materials and production.<ref name = "Fishlow" /> Fishlow also disagrees with the idea that railroads were created ahead of demand, claiming that most railroads were built in areas with already significant economic activity. | |||

| =====Conclusion===== | |||

| The historical views about the economic impact of railroad development in the United States have changed over time with the rise of ]. While traditional economic historians applied existing theory to hypothesize that railroads were indispensable to American economic growth, recent economic historians like Fogel and Fishlow use statistics and mathematical modeling to quantify the actual effect of railroads. It is unclear how accurately such studies can fully estimate the economic conditions under the counterfactual. | |||

| ] | |||

| {| align=center class="wikitable" | |||

| |+ '''Railroad mileage increase by groups of states'''<br><small>Source: ] (ed.), ''One Hundred Years of American Commerce 1795-1895'' p 111</small> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Region | |||

| ! | |||

| ! 1850 | ! 1850 | ||

| ! 1860 | ! 1860 | ||

| Line 130: | Line 143: | ||

| | 129,774 | | 129,774 | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| Many Canadian and U.S. railroads originally used various broad gauges, but most were converted to {{Track gauge|ussg|lk=on}} by 1886, when the conversion of much of the southern rail network from {{Track gauge|5ft|lk=on}} gauge took place. This and the standardization of couplings and air brakes enabled the pooling and interchange of ]s and rolling stock. | |||

| The railroad had its largest impact on the American transportation system during the second half of the 19th century. The standard historical interpretation holds that the railroads were central to the development of a national market in the United States and served as a model of how to organize, finance and manage a large corporation,<ref>Alfred D. Chandler Jr., ''The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business''(1977) pp 81–121.</ref> along with allowing growth of the American population outside of the eastern regions. | |||

| ====Monopolies, anti-trust law, and regulation==== | |||

| Industrialists such as ] and ] became wealthy through railroad ownerships, as large railroad companies such as the ], ] and the ] spanned several states. In response to ] practices (such as ]) and other excesses of some railroads and their owners, ] created the ] (ICC) in 1887. The ICC indirectly controlled the business activities of the railroads through issuance of extensive ]. Congress also enacted ] to prevent railroad monopolies, beginning with the ] in 1890. | |||

| === |

===20th century=== | ||

| ], {{Circa|1860}}]] | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] freight train pauses at ], in March 1943 to cool its braking equipment after descending ]; the ] of ] is visible to the right of the train.]] | |||

| ] train at ] in ]]] | |||

| ]'s ] freight train in ]]] | |||

| The principal mainline railroads concentrated their efforts on moving freight and passengers over long distances. But many had suburban services near large cities, which might also be served by ] and ] lines. The Interurban was a concept which relied almost exclusively on passenger traffic for revenue. Unable to survive the ], the failure of most Interurbans by that time left many cities without suburban passenger railroads, although the largest cities such as New York City, ], ] and ] continued to have suburban service. The major railroads passenger flagship services included multi-day journeys on luxury trains resembling hotels, which were unable to compete with airlines in the 1950s. Rural communities were served by slow trains no more than twice a day. They survived until the 1960s because the same train hauled the ] cars, paid for by the ]. RPOs were withdrawn when mail sorting was mechanized. | |||

| As early as the 1930s, automobile travel had begun to cut into the rail passenger market, somewhat reducing ], but it was the development of the ] and of ] in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as increasingly restrictive regulation, that dealt the most damaging blows to rail transportation, both passenger and freight. ] and others were convicted of running the streetcar industry into the ground purposefully in what is referred to as the ]. There was little point in operating passenger trains to advertise freight service when those who made decisions about freight shipping traveled by car and by air, and when the railroads' chief competitors for that market were interstate trucking companies. | |||

| ====Passenger, freight and interurbans==== | |||

| Soon, the only things keeping most passenger trains running were legal obligations. Meanwhile, companies who were interested in using railroads for profitable freight traffic were looking for ways to get out of those legal obligations, and it looked like intercity passenger rail service would soon become extinct in the United States beyond a few highly populated corridors. The final blow for passenger trains in the U.S. came with the loss of ]s in the 1960s. On May 1, 1971, with only a few exceptions, the federally-funded ] took over all intercity passenger rail service in the continental United States. The ], with its ]-] '']'' and the Southern with its Washington, D.C.–] ] chose to stay out of Amtrak, and the ], with two intrastate ] trains, was too far gone to be included into Amtrak. | |||

| The principal mainline railroads concentrated their efforts on moving freight and passengers over long distances. Unlike railroads in Europe and elsewhere they left suburban traffic to ] and ] lines. The Interurban was an almost uniquely North American concept which relied almost exclusively on passenger traffic for revenue. Unable to survive the ] the failure of Interurbans left most US conurbations without surbuban passenger railroads. The major railroads passenger flagship services were usually multi day journeys on luxury trains resembling hotels - which could not compete with airlines in the 1950s. Rural communities were served by slow trains no more than twice a day. They survived until the 1960s because the same train hauled the ] cars paid for by the U.S Post Office. RPOs were withdrawn when mail sorting was mechanized. | |||

| Freight transportation continued to labor under regulations developed when rail transport had a monopoly on intercity traffic, and railroads only competed with one another. An entire generation of rail managers had been trained to operate under this regulatory regime. ] and their work rules were likewise a formidable barrier to change. Overregulation, management and unions formed an "iron triangle" of stagnation, frustrating the efforts of leaders such as the ]'s ]. In particular, the dense rail network in the Northeastern U.S. was in need of radical pruning and consolidation. A spectacularly unsuccessful beginning was the 1968 formation and subsequent bankruptcy of the ], barely two years later. | |||

| ====Competition with trucks and automobiles==== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=December 2010}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] freight train pauses at Cajon, California, in March 1943 to cool its braking equipment after descending ]. ] (a section that is now part of ]) is visible to the right of the train.]] | |||

| On routes where a single railroad has had an undisputed monopoly, passenger service was as spartan and as expensive as the market and ICC regulation would bear, since such railroads had no need to advertise their freight services. However, on routes where two or three railroads were in direct competition with each other for freight business, such railroads would spare no expense to make their passenger trains as fast, luxurious, and affordable as possible, as it was considered to be the most effective way of advertising their profitable freight services. | |||

| As early as the 1930s, automobile travel had begun to cut into the rail passenger market, somewhat reducing economies of scale, but it was the development of the ] and of ] in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as increasingly restrictive regulation, that dealt the most damaging blows to rail transportation, both passenger and freight (some also cite the ]). There was little point in operating passenger trains to advertise freight service when those who made decisions about freight shipping traveled by car and by air, and when the railroads' chief competitors for that market were interstate trucking companies. Soon, the only things keeping most passenger trains running were legal obligations. Meanwhile, companies who were interested in using railroads for profitable freight traffic were looking for ways to get out of those legal obligations, and it looked like intercity passenger rail service would soon become extinct in the United States beyond a few highly populated corridors. The final blow for passenger trains in the U.S. came with the loss of ]s in the 1960s. On May 1, 1971, the federally funded ] took over (with a few exceptions) all intercity passenger rail service in the continental United States. The ], with its Denver-Ogden ''Rio Grande Zephyr'' and the Southern with its Washington, DC-New Orleans ] chose to stay out of Amtrak, and the Rock Island, with two intrastate Illinois trains, was too far gone to be included into Amtrak. | |||

| The ] (NARP) was formed in 1967 to lobby for the continuation of passenger trains. Its lobbying efforts were hampered somewhat by ] opposition to any sort of ] to the privately owned railroads, and ] opposition to ] of the railroad industry. The proponents were aided by the fact that few in the federal government wanted to be held responsible for the seemingly inevitable extinction of the passenger train, which most regarded as tantamount to political suicide. The urgent need to solve the passenger train disaster was heightened by the bankruptcy filing of the ], the dominant railroad in the ], on June 21, 1970. | |||

| ====Economic decline==== | |||

| Freight transportation continued to labor under regulations developed when rail transport had a monopoly on intercity traffic, and railroads only competed with one another. An entire generation of rail managers had been trained to operate under this regulatory regime. Labor unions and their work rules were likewise a formidable barrier to change. Overregulation, management and unions formed an "iron triangle" of stagnation, frustrating the efforts of leaders such as the New York Central's ]. In particular, the dense rail network in the Northeastern U.S. was in need of radical pruning and consolidation. A spectacularly unsuccessful beginning was the 1968 formation and subsequent bankruptcy of the ], barely two years later. | |||

| Under the ] of 1970, Congress created the ] (NRPC) to subsidize and oversee the operation of intercity passenger trains. The Act provided that: | |||

| ===1970–present=== | |||

| * Any railroad operating intercity passenger service could contract with the NRPC, thereby joining the national system. | |||

| ] | |||

| * Participating railroads bought into the new corporation using a formula based on their recent intercity passenger losses. The purchase price could be satisfied either by cash or rolling stock; in exchange, the railroads received Amtrak common stock. | |||

| ] train at the ] station.]] | |||

| * Any participating railroad was freed of the obligation to operate intercity passenger service after May 1971, except for those services chosen by the ] as part of a "basic system" of service and paid for by NRPC using its federal funds. | |||

| ] ] freight train in ]]] | |||

| * Railroads who chose not to join the Amtrak system were required to continue operating their existing passenger service until 1975 and thenceforth had to pursue the customary ICC approval process for any discontinuance or alteration to the service. | |||

| {{See also|Amtrak}} | |||

| Historically, on routes where a single railroad has had an undisputed ], passenger service was as spartan and as expensive as the market and ICC regulation would bear, since such railroads had no need to advertise their freight services. However, on routes where two or three railroads were in direct competition with each other for freight business, such railroads would spare no expense to make their passenger trains as fast, luxurious, and affordable as possible, as it was considered to be the most effective way of advertising their profitable freight services. | |||

| The original working brand name for NRPC was ''Railpax'', which eventually became ]. At the time, many Washington insiders viewed the corporation as a face-saving way to give passenger trains the one "last hurrah" demanded by the public, but expected that the NRPC would quietly disappear in a few years as public interest waned. However, while Amtrak's political and financial support have often been shaky, popular and political support for Amtrak has allowed it to survive into the 21st century. | |||

| The ] (NARP) was formed in 1967 to lobby for the continuation of passenger trains. Its lobbying efforts were hampered somewhat by Democratic opposition to any sort of subsidies to the privately owned railroads, and Republican opposition to ] of the railroad industry. The proponents were aided by the fact that few in the federal government wanted to be held responsible for the seemingly inevitable extinction of the passenger train, which most regarded as tantamount to political suicide. The urgent need to solve the passenger train disaster was heightened by the ] filing of the ], the dominant railroad in the ], on June 21, 1970. | |||

| To preserve a declining freight rail industry, Congress passed the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973, sometimes called the "3R Act". The act was an attempt to salvage viable freight operations from the bankrupt ] and other lines in the northeast, ] and Midwestern regions.<ref>Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973, Pub.L. 93-236, 87 Stat. 985, {{USC|45|741}}, January 2, 1974.</ref> The law created the ] (Conrail), a government-owned corporation, which began operations in 1976. Another law, the ] of 1976 (the "4R Act"), provided more specifics for the Conrail acquisitions and set the stage for more comprehensive deregulation of the railroad industry.<ref>Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act, Pub.L. 94-210, 90 Stat. 31, {{USC|45|801}}, February 5, 1976.</ref> Portions of the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] were merged into Conrail. On December 31, 1996, the ] ] with the ], creating the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway. | |||

| Under the ] of 1970, Congress created the ] (NRPC) to subsidize and oversee the operation of intercity passenger trains. The Act provided that | |||

| *Any railroad operating intercity passenger service could contract with the NRPC, thereby joining the national system. | |||

| *Participating railroads bought into the new corporation using a formula based on their recent intercity passenger losses. The purchase price could be satisfied either by cash or rolling stock; in exchange, the railroads received Amtrak common stock. | |||

| *Any participating railroad was freed of the obligation to operate intercity passenger service after May 1971, except for those services chosen by the Department of Transportation as part of a "basic system" of service and paid for by NRPC using its federal funds. | |||

| *Railroads who chose not to join the Amtrak system were required to continue operating their existing passenger service until 1975 and thenceforth had to pursue the customary ICC approval process for any discontinuance or alteration to the service. | |||

| The freight industry continued its decline until Congress passed the ] in 1980, which largely deregulated the rail industry. Since then, U.S. freight railroads have reorganized, discontinued their lightly used routes and returned to profitability.<ref name="Stover-American RR">{{cite book |title=American Railroads |last=Stover |first=John F.|year=1997 |edition = 2nd |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |isbn=978-0-226-77658-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R4vjgmic44QC}}</ref>{{rp|245–252}} | |||

| The original working brand name for NRPC was ''Railpax'', which eventually became '']''. At the time, many Washington insiders viewed the corporation as a face-saving way to give passenger trains the one "last hurrah" demanded by the public, but expected that the NRPC would quietly disappear in a few years as public interest waned. However, while Amtrak's political and financial support have often been shaky, popular and political support for Amtrak has allowed it to survive into the 21st century. | |||

| ==Freight railroads== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{More citations needed section|date=October 2010}} | |||

| Similarly, to preserve a declining freight rail industry, Congress passed the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973 (sometimes called the "3R Act"). The act was an attempt to salvage viable freight operations from the bankrupt Penn Central and other lines in the northeast, mid-Atlantic and Midwestern regions.<ref>Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973, Pub.L. 93-236, 87 Stat. 985, {{USC|45|741}}, 1974-01-02.</ref> The law created the ] (Conrail), a government-owned corporation, which began operations in 1976. Another law, the ] of 1976 (the "4R Act"), provided more specifics for the Conrail acquisitions and set the stage for more comprehensive deregulation of the railroad industry.<ref>Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act, Pub.L. 94-210, 90 Stat. 31, {{USC|45|801}}, 1976-02-05.</ref> Portions of the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] were merged into Conrail. | |||

| {{See also|Rail freight transport}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]s play an important role in the U.S. economy, especially for moving imports and exports using containers, and for shipments of coal and oil. Productivity rose 172% between 1981 and 2000, while rates decreased by 55%, after accounting for ]. Rail's share of the American freight market rose to 43%.<ref name="economist2010-07-22">{{cite news | url=http://www.economist.com/node/16636101 | title=High-speed railroading | newspaper=The Economist | date=July 22, 2010 | access-date=December 10, 2011}}</ref> | |||

| U.S. railroads still play a major role in the nation's ]ping. They carried 750 billion ton-miles by 1975 which doubled to 1.5 trillion ton-miles in 2005.<ref name="BTS1">U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Washington, D.C. (2000) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180522111801/https://www.bts.gov/publications/the_changing_face_of_transportation/html/figure_01_ton_miles_of_freight_by_mode.html |date=May 22, 2018 }} ''The Changing Face of Transportation.'' Report No. BTS00-007.</ref><ref>National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060206232522/http://americanhistory.si.edu/onthemove/themes/story_42_4.html |date=February 6, 2006 }} ''America on the Move.''</ref> In the 1950s, the U.S. and ] moved roughly the same percentage of freight by rail; by 2000, the share of U.S. rail freight was 38% while in Europe only 8% of freight traveled by rail; a large proportion of this difference is due to external factors such as geography and higher use of goods like coal.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060902215734/http://www.ksg.harvard.edu/taubmancenter/pdfs/working_papers/fagan_vassallo_05_rail.pdf |date=September 2, 2006 }} See Alternate Link 7</ref><ref>International Union of Railways Alternate Source for Dead Link</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Freemark |first1=Yonah |title=Freight as Passenger Rail's Worst Enemy — Or Something Else? |url=https://www.thetransportpolitic.com/2011/06/29/freight-as-passenger-rails-worst-enemy-or-something-else/ |website=The Transport Politic |access-date=20 June 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Manuel Bastos Andrade Furtado |first1=Francisco |title=U.S. and European Freight Railways: The Differences That Matter |journal=Journal of the Transportation Research Forum |date=Summer 2013 |volume=52 |issue=2 |pages=65–84 |url=https://trforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2013v52n2_04_FreightRailways.pdf |access-date=25 July 2023}}</ref> | |||

| The freight industry continued its decline until Congress passed the ] in 1980, which largely deregulated the rail industry. Since then, U.S. freight railroads have reorganized, discontinued their lightly used routes and returned to profitability.<ref name="Stover-American RR">{{cite book |title=American Railroads |last=Stover |first=John F. |authorlink= |year=1997 |edition = 2nd |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |isbn=978-0-226-77658-3 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=R4vjgmic44QC&source=gbs_navlinks_s |accessdate=}}</ref>{{rp|245-252}} | |||

| In ton-miles, railroads annually move more than 25% of the United States' freight and connect businesses with each other across the country and with markets overseas.<ref name="BTS1" /> In 2018, US rail freight had a ] of 473 ton-miles per gallon of fuel.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Economic Impact of America's Freight Railroads |url=https://www.aar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/AAR-Economic-Impact-US-Freight-Railroads.pdf |publisher=] |pages=2 |date=July 2019}}</ref> In recent years, railroads have gradually been losing intermodal traffic to trucking.<ref>{{cite news |title=Supply Chain News: Is Trucking Gaining Share over Rail in Long Haul Freight Moves? |url=https://www.scdigest.com/ontarget/22-02-22_rail_losing_share_to_truckling.php?cid=19619 |access-date=3 August 2023 |work=Supply Chain Digest |date=22 February 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ==Freight railroads in today's economy== | |||

| {{Refimprove section|date=October 2010}} | |||

| In terms of ton-miles, railroads annually move more than 25% of the United States' freight and connect businesses with each other across the country and with markets overseas.<ref name="BTS1" /> | |||

| ===Railroad classes=== | |||

| In 2013, the US moved more oil out of North Dakota by rail than the Trans-Alaska pipeline.<ref name="sciam"></ref> This trend--tenfold in two years and 40-fold in five years--is forecast to increase.<ref name="natlgeo"></ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Railroad classes}} | |||

| U.S. freight railroads are separated into three classes, set by the ], based on annual revenues: | |||

| * ] for freight railroads with annual operating revenues above $346.8 million in 2006 dollars. In 1900, there were 132 Class I railroads. In 2024, as the result of mergers, bankruptcies, and major changes in the regulatory definition of "Class I", there are only six railroads operating in the United States that meet the criteria for Class I. {{As of|2011}}, U.S. freight railroads operated 139,679 route-miles (224,792 km) of ] in the U.S. Although ] qualifies for Class I status under the revenue criterion, it is not considered a Class I railroad because it is not a freight railroad. | |||

| * ] for freight railroads with revenues between $27.8 million and $346.7 million in 2000 dollars | |||

| * ] for all other freight revenues. | |||

| In 2013, the U.S. moved more oil out of North Dakota by rail than by the ].<ref name="sciam">{{cite web|url=http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/plugged-in/2013/07/17/u-s-moves-more-oil-out-of-north-dakota-by-rail-than-the-trans-alaskan-pipeline/|title=U.S. moves more oil out of North Dakota by rail than the Trans-Alaskan pipeline|first=David|last=Wogan|website=scientificamerican.com}}</ref> This trend—tenfold in two years and 40-fold in five years—is forecast to increase.<ref name="natlgeo">{{cite web|url= http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/2013/07/130708-oil-train-tragedy-in-canada/ |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20130709173440/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/2013/07/130708-oil-train-tragedy-in-canada/ |url-status= dead |archive-date= July 9, 2013 |title=Oil Train Tragedy in Canada Spotlights Rising Crude Transport by Rail|date=July 8, 2013|website=nationalgeographic.com}}</ref> | |||

| ===Types of rail=== | |||

| There are four different types of freight railroads: ], regional, local line haul, and switching & terminal. ] are defined as those with revenue of at least $346.8 million in 2006. They comprise just one percent of the number of ]s, but account for 67 percent of the industry's mileage, 90 percent of its employees, and 93 percent of its freight revenue. | |||

| ===Classes of freight railroads=== | |||

| A ] is a line haul railroad with at least {{convert|350|mi|km}} and/or revenue between $40 million and the Class I threshold. There were 33 regional railroads in 2006. Most have between 75 and 500 employees. | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=September 2023}} | |||

| There are four different classes of freight railroads: ], regional, local line haul, and switching & terminal. Class I railroads are defined as those with revenue of at least $346.8 million in 2006. They comprise just 1% of the number of ]s, but account for 67% of the industry's mileage, 90% of its employees, and 93% of its freight revenue. | |||

| A ] is a line haul railroad with at least {{convert|350|mi|km}} and/or revenue between $40 million and the Class I threshold. There were 33 regional railroads in 2006. Most have between 75 and 500 employees. | |||

| Local line haul railroads operate less than {{convert|350|mi|km}} and earn less than $40 million per year (most earn less than $5 million per year). In 2006, there were 323 local line haul railroads. They generally perform point-to-point service over short distances. | |||

| Switching and terminal (S&T) carriers are railroads that primarily provide switching and/or terminal services, regardless of revenue. They perform pick up and delivery services within a certain area. | Switching and terminal (S&T) carriers are railroads that primarily provide switching and/or terminal services, regardless of revenue. They perform pick up and delivery services within a certain area. | ||

| ===Traffic and public benefits=== | ===Traffic and public benefits=== | ||

| ]s (2010 ] report)<ref name="Progress Report">{{Cite web |title=National Rail Plan Progress Report {{!}} FRA |author= |work=railroads.dot.gov |date=September 2010 |access-date=31 March 2022 |url=https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/national-rail-plan-progress-report}}</ref>]] | |||

| U.S. freight railroads operate in a highly competitive marketplace. To compete effectively against each other and against other transportation providers, railroads must offer high-quality service at competitive rates. In 2011, within the U.S., railroads carried 39.9% of freight by ton-mile, followed by trucks (33.4%), oil pipelines (14.3%), barges (12%) and air (0.3%). However, railroads' revenue share has been slowly falling for decades, a reflection of the intensity of the competition they face and of the large rate reductions railroads have passed through to their customers over the years. | |||

| ] | |||

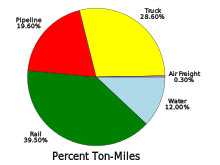

| U.S. freight railroads operate in a highly competitive marketplace. According to a 2010 ] report, within the U.S., railroads carried 39.5% of freight by ton-mile, followed by trucks (28.6%), oil pipelines (19.6%), barges (12%) and air (0.3%).<ref name="Progress Report"/> However, railroads' revenue share has been slowly falling for decades, a reflection of the intensity of the competition they face and of the large rate reductions railroads have passed through to their customers over the years.{{citation needed|date=April 2016}} | |||

| North American railroads operated 1,471,736 freight cars and 31,875 locomotives, with 215,985 employees, They originated 39.53 million carloads (averaging 63 tons each) and generated $81.7 billion in freight revenue. The average haul was 917 miles. The largest (Class 1) U.S. railroads carried 10.17 million intermodal containers and 1.72 million piggyback trailers. Intermodal traffic was 6.2% of tonnage originated and 12.6% of revenue. The largest commodities were coal, chemicals, farm products, nonmetallic minerals and intermodal. Other major commodities carried include lumber, automobiles, and waste materials. Coal alone was 43.3% of tonnage and 24.7% of revenue.<ref>, Association of American Railroads, February 7, 2013</ref>Coal accounts roughly half of U.S. electricity generation<ref>http://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/update/</ref> and is a major export. | |||

| In 2011, North American railroads operated 1,471,736 freight cars and 31,875 locomotives, with 215,985 employees. They originated 39.53 million carloads (averaging 63 tons each) and generated $81.7 billion in freight revenue of present 2014. The average haul was 917 miles. The largest (Class 1) U.S. railroads carried 10.17 million intermodal containers and 1.72 million piggyback trailers. Intermodal traffic was 6.2% of tonnage originated and 12.6% of revenue. The largest commodities were coal, chemicals, farm products, nonmetallic minerals and intermodal. Other major commodities carried include lumber, automobiles, and waste materials. Coal alone was 43.3% of tonnage and 24.7% of revenue.<ref> {{Webarchive|url= https://web.archive.org/web/20131103071634/https://www.aar.org/StatisticsAndPublications/Documents/AAR-Stats-2013-02-07.pdf |date=November 3, 2013 }}, Association of American Railroads, February 7, 2013</ref> Coal accounted for roughly half of U.S. electricity generation<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/update/ |title=Electricity Monthly Update – Energy Information Administration|website=EIA.gov}}</ref> and was a major export. As ] became cheaper than coal, coal supplies dropped 11% in 2015 but coal rail freight dropped by up to 40%, allowing an increase in car transport by rail, some in tri-level railcars.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://automotivelogistics.media/intelligence/north-american-rail-one-door-closes-another-opens |title=North American rail: One door closes, another opens |first=Marcus |last=Williams |date=March 29, 2016|publisher= Automotive Logistics|access-date=May 14, 2017 |quote=11% compared to 2014 production, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). The drop hit railways’ revenue by as much as 40% in some segments.}}</ref> US coal consumption dwindled from over 1,100 million tons in 2008 to 687 million tons in 2018.<ref name="aar2018c">{{cite web |title=Railroads and Coal |url=https://www.aar.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/AAR-Railroads-Coal.pdf |publisher=] |pages=2 |date=May 2019}}</ref> | |||

| The fastest growing rail traffic segment is currently ]. Intermodal is the movement of ] or truck trailers by rail and at least one other mode of transportation, usually trucks or ocean-going vessels. Intermodal combines the door-to-door convenience of trucks with the long-haul economy of railroads. Rail intermodal has tripled in the last 25 years. It plays a critical role in making logistics far more efficient for retailers and others. The efficiency of intermodal provides the U.S. with a huge competitive advantage in the global economy. | |||

| ===Freight rail working with passenger rail=== | ===Freight rail working with passenger rail=== | ||

| Prior to Amtrak's creation in 1970, intercity passenger rail service in the U.S. was provided by the same companies that provided freight service. When Amtrak was formed, in return for government permission to exit the passenger rail business, freight railroads donated passenger equipment to Amtrak and helped it get started with a capital infusion of some $200 |

Prior to ]'s creation in 1970, intercity ] in the U.S. was provided by the same companies that provided freight service. When Amtrak was formed, in return for government permission to exit the passenger rail business, freight railroads donated passenger equipment to Amtrak and helped it get started with a capital infusion of some $200 million. | ||

| The vast majority of the 22,000 or so |

The vast majority of the {{cvt|22,000|mi}} or so over which Amtrak operates are actually owned by freight railroads. By law, freight railroads must grant Amtrak access to their track upon request. In return, Amtrak pays fees to freight railroads to cover the ]s of Amtrak's use of freight railroad tracks.{{citation needed|date=January 2017}} | ||

| ==Passenger |

==Passenger railroads== | ||

| {{For|routes and operators|Amtrak|Alaska Railroad|Brightline|List of rail transit systems in the United States}} | |||

| ] in Florida)]] | |||

| The sole long-distance intercity ] in the continental U.S. is ], and multiple current commuter rail systems provide regional intercity services such as New York-New Haven, and Stockton-San Jose. In Alaska, intercity service is provided by ] instead of Amtrak. ] systems exist in more than a dozen metropolitan areas, but these systems are not extensively interconnected, so commuter rail cannot be used alone to traverse the country. ] have been proposed in approximately two dozen other cities, but interplays between various local-government administrative bottlenecks and ripple effects from the ] have generally pushed such projects farther and farther into the future, or have even sometimes mothballed them entirely. | |||

| The most culturally notable and physically evident exception to the general lack of significant passenger rail transport in the U.S. is the ] between ], ], ], ], and ], with significant branches in ] and ]. The corridor handles frequent passenger service that is both Amtrak and commuter. New York City itself is noteworthy for high usage of passenger rail transport, both ] and commuter rail (], ], ]). The subway system is used by one third of all U.S. ] users. ] also sees high rail ridership, with a local ], one of the world's last ], and fourth most-ridden commuter rail system in the United States: ]. Other major cities with substantial rail infrastructure include ]'s ], ]'s ], and Washington, D.C.'s network of commuter rail and rapid transit. ], Colorado constructed a ] in the 2000s to complement the city's light rail system. The commuter rail systems of ] and Los Angeles, ] and ], connect in ]. The ] additionally hosts several local passenger rail operators, the largest of which are ], the ], ], and ]. | |||

| Privately run inter-city passenger rail operations have also been restarted since 2018 in south Florida, with additional routes under development. ] is a ] train, run by All Aboard Florida. It began service in January 2018 between ] and ]; its service was extended to Miami in May 2018, and an extension to ] opened for daily service on September 22, 2023, which includes a segment of brand new rail line from Orlando eastward toward the Atlantic coast.<ref>{{cite news |title=High-speed trains begin making trip between Orlando and Miami |url=https://apnews.com/article/highspeed-rail-trains-florida-brightline-7a7bd3b390c43a8becc811d68dfcf386 |access-date=23 September 2023 |publisher=Associated Press |date=23 September 2023 |ref=Orlando-open}}</ref> Brightline has also proposed a further extension of its service from Orlando to ] via ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.tampabay.com/business/brightline-virgin-rail-service-looking-at-disney-station-along-proposed-tampa-to-orlando-route-20190104/|title=Brightline-Virgin rail service looking at Disney station along proposed Tampa-to-Orlando route|last=Danielson|first=Richard|date=January 4, 2019|website=Tampa Bay Times|language=en|access-date=September 11, 2019}}</ref> and a ] from ] to ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.vvdailypress.com/news/20190715/victorville-vegas-train-may-be-rolling-by-2023|title=Victorville-Vegas train may be rolling by 2023|last=Huffine|first=Bryce|date=July 15, 2019|work=The Daily Press|access-date=September 10, 2019|publication-place=Victorville, California|archive-date=July 15, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190715140219/https://www.vvdailypress.com/news/20190715/victorville-vegas-train-may-be-rolling-by-2023|url-status=dead}}</ref> In addition, the ] is currently developing plans for a proposed greenfield ] line using Japanese ] trains between ] and ]. Construction was expected to begin in 2020 for a 2026 opening,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.kbtx.com/content/news/Federal-Railroad-Commission-to-begin-rule-making-on-high-speed-railway-559624071.html|title=Federal Railroad Commission to begin rule making on high speed railway|last=Hogan|first=Kendall|date=September 9, 2019|website=KBTX.com|access-date=September 11, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| but a major lawsuit delayed the project and as of February 2023 there are no signs of construction activity.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===Car types=== | ===Car types=== | ||

| The basic design of a ] was standardized by 1870. By 1900 the main car types were: baggage, coach, combine, diner, ], lounge, observation, private, Pullman, railroad post office (RPO) and sleeper. | The basic design of a ] was standardized by 1870. By 1900, the main car types were: baggage, coach, combine, diner, ], lounge, observation, private, Pullman, railroad post office (RPO) and sleeper. | ||

| ===19th century: First passenger cars and early development=== | ====19th century: First passenger cars and early development==== | ||

| ] on the ], circa 1900.]] | |||

| {{Main|Passenger car (rail)}} | {{Main|Passenger car (rail)}} | ||

| ] on the ], circa 1900]] | |||

| The first passenger cars |

The first passenger cars resembled ]es. They were short, often less than {{convert|10|ft|m|2|abbr=on}} long, tall and rode on a single pair of axles. | ||

| American mail cars first appeared in the 1860s and at first followed English design. They had a hook that would catch the mailbag in its crook. | American mail cars first appeared in the 1860s and at first followed English design. They had a hook that would catch the mailbag in its crook. | ||

| Line 221: | Line 249: | ||

| Dining cars first appeared in the late 1870s and into the 1880s. Until this time, the common practice was to stop for meals at restaurants along the way (which led to the rise of ]'s chain of ] restaurants in America). At first, the dining car was simply a place to serve meals that were picked up en route, but they soon evolved to include galleys in which the meals were prepared. | Dining cars first appeared in the late 1870s and into the 1880s. Until this time, the common practice was to stop for meals at restaurants along the way (which led to the rise of ]'s chain of ] restaurants in America). At first, the dining car was simply a place to serve meals that were picked up en route, but they soon evolved to include galleys in which the meals were prepared. | ||

| ===1900–1950: Lighter materials, new car types=== | ====1900–1950: Lighter materials, new car types==== | ||

| ]'s '']''. The carbody was made of ] in 1934, it is seen here at the ] in |

]'s '']''. The carbody was made of ] in 1934, it is seen here at the ] in Chicago in 2003.]] | ||

| By the 1920s, passenger cars on the larger ] railroads were normally between {{convert|60|and|70|ft|m}} long. The cars of this time were still quite ornate, many of them being built by experienced coach makers and skilled carpenters. | By the 1920s, passenger cars on the larger ] railroads were normally between {{convert|60|and|70|ft|m}} long. The cars of this time were still quite ornate, many of them being built by experienced coach makers and skilled carpenters. | ||

| With the 1930s came the widespread use of ] for |

With the 1930s came the widespread use of ] for car bodies. The typical passenger car was now much lighter than its "heavyweight" wood cousins of old. The new "lightweight" and ] cars carried passengers in speed and comfort to an extent that had not been experienced to date. Aluminum and ] were also used in lightweight car construction, but stainless steel was the preferred material for car bodies. It is not the lightest of materials, nor is it the least expensive, but stainless steel cars could be, and often were, left unpainted except for the car's ]s that were required by law. | ||

| By the end of the 1930s, railroads and |

By the end of the 1930s, railroads and car builders were debuting car body and interior styles that could only be dreamed of before. In 1937, the Pullman Company delivered the first cars equipped with ]s—that is, the car's interior was sectioned off into compartments, much like the coaches that were still in widespread use across Europe. Pullman's roomettes, however, were designed with the single traveler in mind. The roomette featured a large picture window, a privacy door, a single fold-away bed, a sink and small toilet. The roomette's floor space was barely larger than the space taken up by the bed, but it allowed the traveler to ride in luxury compared to the multilevel semiprivate berths of old. | ||

| Now that passenger cars were lighter, they were able to carry heavier loads, but the size of the average passenger load that rode in them didn't increase to match the cars' new capacities. The average passenger car couldn't get any wider or longer due to side clearances along the railroad lines, but they generally could get taller because they were still shorter than many freight cars and locomotives. As a result, the railroads soon began building and buying ] and ] cars to carry more passengers. | Now that passenger cars were lighter, they were able to carry heavier loads, but the size of the average passenger load that rode in them didn't increase to match the cars' new capacities. The average passenger car couldn't get any wider or longer due to side clearances along the railroad lines, but they generally could get taller because they were still shorter than many freight cars and locomotives. As a result, the railroads soon began building and buying ] and ] cars to carry more passengers. | ||

| ===1950–present: High-technology advancements=== | ===1950–present: High-technology advancements=== | ||

| ]. Shown here is a ] coach, a regional commuter rail system in |

]. Shown here is a ] coach, a regional commuter rail system in Florida. Similar cars are used in California by ].]] | ||

| ] ] double-decker ]s of ] at {{stn|San Jose Diridon}}]] | |||

| Carbody styles have generally remained consistent since the middle of the 20th century. While new car types have not made much of an impact, the existing car types have been further enhanced with new technology. | Carbody styles have generally remained consistent since the middle of the 20th century. While new car types have not made much of an impact, the existing car types have been further enhanced with new technology. | ||

| Starting in the 1950s, the passenger travel market declined in North America, though there was growth in ]. The higher clearances in North America enabled bi-level commuter coaches that could hold more passengers. These cars started to become common in the United States in the 1960s. | Starting in the 1950s, the passenger travel market declined in North America, though there was growth in ]. The higher clearances in North America enabled bi-level commuter coaches that could hold more passengers. These cars started to become common in the United States in the 1960s. | ||

| While intercity passenger rail travel declined in the United States during 1950s, ridership continued to increase in Europe during that time. With the increase came newer technology on existing and new equipment. The |

While intercity passenger rail travel declined in the United States during the 1950s, ridership continued to increase in ] during that time. With the increase came newer technology on existing and new equipment. The Spanish company ] began experimenting in the 1940s with technology that would enable the axles to steer into a curve, allowing the train to move around the curve at a higher speed. The steering axles evolved into mechanisms that would also tilt the passenger car as it entered a curve to counter the ] experienced by the train, further increasing speeds on existing track. Today, tilting passenger trains are commonplace. Talgo's trains are used on some short and medium distance routes such as ] from ], to ]. | ||

| In August 2016, the Department of Transportation approved the largest loan in the department's history, $2.45 billion to upgrade the passenger train service in the Northeast region. The $2.45 billion will be used to purchase 28 new train sets for the high-speed Acela train between Washington through Philadelphia, New York and into Boston. The money will also be used build new stations and platforms. The money will also be used to rehabilitate railroad tracks and upgrade four stations, including Washington's Union Station and Baltimore's Penn Station. | |||

| ===U.S. high-speed rail=== | |||

| ] | |||

| As of 2014, U.S. railroad mileage has stabilized at approximately {{Convert|160000|mi|km}}.<ref>{{Cite web |title=U.S. Railroad Track Miles & Revenue By Year |url=https://www.railserve.com/stats_records/railroad_route_miles.html |access-date=2022-12-26 |website=www.railserve.com}}</ref> | |||

| ===High-speed rail=== | |||

| {{Main|High-speed rail in the United States}} | {{Main|High-speed rail in the United States}} | ||

| ] | |||

| As of 2022, the only operating high speed rail service in the United States is Amtrak's '']'', between Washington, DC, and ]. It currently has a maximum speed of {{convert|150|mph|kph}}, and only in some sections between Boston and Providence, RI, soon to be {{convert|160|mph|kph}} after introduction of new ] trains, eventually to be upgraded to {{convert|186|mph|kph}} over some sections. The state of California is constructing its own HSR system, ], constructed to {{convert|220|mph|kph}} standards in some places. The first section in the ] is due to open around 2027. | |||

| ====Higher-speed rail==== | |||