| Revision as of 18:20, 20 January 2021 view source79.54.16.70 (talk) Undid revision 1001657814 by Kansas Bear (talk) Dupuy pag 462 write French losses were at least 1000. You can only take what it suits youTag: Undo← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:30, 20 January 2021 view source EdJohnston (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators71,240 editsm Protected "Battle of Fornovo": IP-hopping edit war, continued ( (indefinite) (indefinite))Next edit → |

| (No difference) | |

Revision as of 18:30, 20 January 2021

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Battle of Fornovo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Italian War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

League of Venice: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000–11,000 men | 20,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Italian War of 1494–1498 | |

|---|---|

| Italian Wars | |

|---|---|

| Full list of battles |

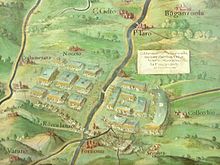

The Battle of Fornovo took place 30 km (19 miles) southwest of the city of Parma on 6 July 1495. It was fought as King Charles VIII of France left Naples upon hearing the news of the grand coalition assembled against him. Even though he managed to pass, he lost the battle. It was nonetheless devoid of any strategic result as all of their conquests in the Italian Peninsula were abandoned. Fornovo was the first major pitched battle of the Italian Wars.

Antecedents

In the year 1495, Charles VIII was the youthful King of France, the most powerful state in medieval Europe. A dreamer who saw himself as the saviour of Christian Europe, he believed he could roll-back the ever-spreading tide of Ottoman Turkish conquest. As a base for his crusade, he was determined to seize Southern Italy. His claim on the Kingdom of Naples through his paternal grandmother, Marie of Anjou (1404–1463) presented such an opportunity.

To have his hands free in Italy, Charles made various pacts with his neighbours, so they would not interfere. Henry VII of England was given cash, Ferdinand II of Aragon was given Roussillon and Emperor Maximillian was given Artois and Franche-Comté. This handing out of territory could be regarded as a total lack of foresight on Charles' behalf but he was willing to take such steps to establish his Neapolitan base for his crusade.

Italian armies of the late medieval period consisted of forces from the many independent towns of Italy. They were raised by establishing a contract, or "condotta", between the town leaders and the chiefs of mercenary bands, who came to be called Condottieri. Military doctrines and tactics destined to establish field supremacy were developed, as were methods of capture of wealthy prisoners for ransom, and astuces to minimize casualties. All of these were proven ineffective when the highly motivated standing armies of France and Spain invaded the Italian Peninsula.

Campaign

Charles VIII was on good terms with the two powers in northern Italy, Milan and Venice, and both had encouraged his claim over the Kingdom of Naples. Thus he assumed he would have their support when he moved against Alfonso II of Naples, especially as the rival claimant was Ferdinand II of Aragon, King of Spain. At the end of August 1494, in a lightning campaign, he used France's powerful modern army, reinforced by a large contingent of Swiss mercenaries, to sweep through Italy, his mobile field artillery train smashing into dust the tall towers of Italy's medieval castles. He was granted free passage through Milan, but was vigorously opposed by Florence, Pope Alexander VI, and Naples.

On their way to Naples, the French defeated every army sent against them and were ruthless with any city that resisted the invasion. This shocked the Italians, who were accustomed to the relatively bloodless wars of the Condottieri.

On 22 February 1495 Charles VIII and his chief commander, Louis II de La Trémoille, entered Naples almost without opposition. The speed and violence of the campaign left the Italians stunned. Realization struck them, especially the Venetians and the new Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, that unless Charles was stopped Italy would soon just be another province of France. The Italian states rallied and on March 31 in Venice, the Holy League was proclaimed. The signatories were the Republic of Venice, the Duke of Milan, the Pope, the monarchs of Castile and Aragon, the King of England and the Holy Roman Emperor. The League engaged a veteran Condottiero, Francesco II of Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua to gather an army and expel the French from Italy. Upon hearing the news of the coalition assembled against him, Charles VIII left behing a garrisoning force in Naples and marched north with the remainder of his army, his artillery train and the considerable booty seized in the campaign thus far in order to join a smaller army under Louis II, Duke of Orléans in Piedmont in north-western Italy. While in Naples, the French army had been swept by an outbreak of syphilis and as the army moved north, it spread throughout Italy, where it became known as the "French Disease".

Battle

On 27 June the Venetians and their allies established camp near Fornovo di Taro (44°41′N 10°06′E / 44.683°N 10.100°E / 44.683; 10.100), some 30 km southwest of Parma, to wait for the French. They would not have to wait long, but the Venetian Senate was not unanimous on fighting the French. Some members wanted to attack the rear guard of the French to try to seize their loot, while others cautioned that Italy was risking too much in this battle as this was just one French army and others could potentially be called upon.

On July 4, Ercole d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, Charles' strongest ally in Italy, wrote to him and informed him that the Senate had not yet decided on an action. But Charles was anxious, seeing the enemy numbers growing, while he himself had no hope of reinforcements for the time being. When an effort to sway the undecided forces of Parma was thwarted by the Venetians, Charles instead sent a messenger to request free passage to return to France, but the Venetians replied that he would have to restore all his conquests before such could be considered. The messenger, having scouted the troops, reported back to Charles. The 40 soldiers Charles subsequently sent to reconnoiter were attacked and quickly routed by the Stradioti, mostly Albanian mercenaries from the Balkans.

Two days later, on July 6, Charles decided to offer battle because the French were short of provisions. South of Milan, the path of his army of some 10,000 French and Swiss was blocked by 20,000 Venetians and Mantuans under Gonzaga. The League army took position on the right side of the Taro river and the French decided to keep to the left bank. Charles organized his army in battle groups. The first battle consisted of about 2,500 men and was led by Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. The second, the largest, was led by Charles himself. The final battle, about 1,400 men, was led by Francesco Secco. There was in addition a large infantry force of spearmen. The French artillery was arranged in front of the first line, as well as on the side of the Taro, protecting the second line.

Melchiorre Trevisan promised the League soldiers the spoils of battle if they were victorious, igniting their combat ardor. Francesco Gonzaga divided his forces into nine lines. His battle plan was to distract the first and middle groups of the French with two lines while outflanking the rear. Once the French groups were disorganized, the rest of the Italian troops would attack.

Instead of the usual feckless and nearly bloodless affair then common in Italian condottieri warfare, the French opened with an artillery bombardment, intending to kill as many of their opponents as possible. Then they charged with their heavy cavalry, destroying and scattering the disordered Italian ranks in just minutes. The fight was perhaps more memorable for the ineffectiveness of artillery on either side, other than the psychological effect achieved by the French guns. Of the 100 French and 3,500 Italian dead, one eyewitness estimated that fewer than 10 men were killed by cannon fire. After the battle, Charles then marched on into Lombardy and returned to France.

Both parties strove to present themselves as the victors in the battle. The battle was reported in Venice as a victory, and was recorded and celebrated as such. But the French had won their battle, fighting off superior numbers and proceeding on their march. The League took much higher casualties and could not prevent the French army from crossing Italian lands on its way back to France.

Consequences

Ironically, on the same day as the battle was fought, Ferdinand II appeared before Naples with a Spanish fleet; he re-entered and occupied Naples the following day. He was welcomed with rejoicing by the citizens, as the French had made themselves hated through their behaviour. Pope Alexander VI denounced the French as having committed worse crimes in Italy than had the Goths. Already under threat of excommunication, Charles VIII was ordered to lay down his arms and promote the peace of Christendom by the pope. Alexander also wrote to the Venetians to congratulate them on winning "immortal fame" by their liberation of Italy.

Charles left Italy abandoning all his conquests. He attempted in the next few years to rebuild his army, but was hampered by the serious debts incurred by the previous one, and he never succeeded in recouping anything substantive. He died two-and-a-half years after his retreat, of an accident, striking his head while passing through a doorway, he succumbed to a sudden coma several hours later.

Charles bequeathed a meagre legacy: he left France in debt and in disarray as a result of an ambition most charitably characterized as unrealistic, and having lost several important provinces that it would take centuries to recover. On a more positive side, his expedition did broaden contacts between French and Italian humanists, energizing French art and letters in the latter Renaissance.

Charles proved to be the last of the elder branch of the House of Valois, and upon his death at Amboise the throne passed to a cousin, the Duc d'Orléans, who reigned as King Louis XII of France, who would try to make good his clearer claim to the Duchy of Milan.

However, for Italy the consequences were catastrophic. Europe knew now, from Charles' expedition, of an enormously rich land, divided into easily conquerable principalities, and defended only by mercenary armies that refused to fight with the slightest disadvantage. Italy was to be the scene of a dispute between the main continental powers, with the result that the Italians were left with only a secondary role in their own destiny. Only Venice, Genoa, the Papal States, Savoy, and Tuscany would survive as independent nations after the end of the Italian Wars, losing however their original power and stability.

See also

Notes

References

- Mallett, M. E.; Hale, J. R. (1984). The Military Organisation of a Renaissance State: Venice C. 1400 to 1617. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-521-24842-6.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 31.

- ^ Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars 1494–1559, (Pearson, 2012), 31;"The French army of 10,000-11,000 men came down the valley of the Taro towards Parma. Gonzaga had about 20,000 troops...".

- Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 303. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 303. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 304. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 304. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Palmer 1994, p. 19.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Birtachas, Stathis (2018). "Stradioti, Cappelletti, Compagnie or Milizie Greche: 'Greek' Mounted and Foot Troops in the Venetian State (Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries". In Georgios Theotokis; Aysel Yıldız (eds.). A Military History of the Mediterranean Sea: Aspects of War, Diplomacy, and Military Elites. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-90-04-31509-9.

- Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 303. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 303-304. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 304. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Nolan, Cathal. "The Age Of Wars Of Religion, 1000 1650". www.goodreads.com. p. 304. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- ^ Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars 1494–1559, 31.

- Setton, pp. 494–495

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Setton 1978, p. 493–494.

- Setton. pp. 495–496

Sources

- Dupuy, Trevor N. (1993). Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-270056-8.

- Nicolle, David (1996). Fornovo 1495: France's Bloody Fighting Retreat. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-522-7.

- Ritchie, Robert (2004). Historical Atlas of The Renaissance. Thalamus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-5731-3.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1978). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume II: The Fifteenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-127-2.

- Mallett, M. E.; Hale, J. R. (1984). The Military Organisation of a Renaissance State: Venice C. 1400 to 1617. Cambridge University Press.

- Mallett, Michael; Shaw, Christine (2012). The Italian Wars 1494–1559. Pearson.

- Palmer, William (1994). The Problem of Ireland in Tudor Foreign Policy, 1485–1603. The Boydell Press.

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Battle of Fornovo at Wikimedia Commons