| Revision as of 02:20, 21 March 2022 editLittleJerry (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers47,901 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:47, 21 March 2022 edit undo218.250.105.206 (talk) →RangeNext edit → | ||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

| ==Range== | ==Range== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Humpback whales have a near ], being absent only from some enclosed seas and parts of the High Arctic.{{R|Jefferson}} The furthest north they have been recorded is at ] around southern ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Zein |first1=Beate |last2=Haugum |first2=Siri Vatsø |title=The northernmost sightings of Humpback whales |journal=Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology |date=2018 |volume=10:1 |pages=5–8 |url=http://www.oers.ca/journal/volume10/issue1/communication.pdf |access-date=2019-06-17 |archive-date=2019-06-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190617095824/http://www.oers.ca/journal/volume10/issue1/communication.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Humpbacks feed and breed near coasts and over ]. Their winter breeding grounds are located around the tropics while their summer feeding groups are found in temperature and polar areas, even reaching the ice edges of both the Arctic and Antarctic. Humpbacks go on vast ] between their feeding and breeding areas, often crossing ]s. The species has been recorded traveling up to {{convert|8000|km|abbr=on}} in one direction.{{R|Jefferson}} A unique, non-migratory population feeds and breeds in the northern Indian Ocean mainly in the Arabian Sea around ].{{r|NOAA}} This population has also been recorded in the ], the ] and off the coasts of Pakistan and India.{{R|arabian}} | Humpback whales have a near ], being absent only from some enclosed seas and parts of the High Arctic.{{R|Jefferson}} The furthest north they have been recorded is at ] around southern ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Zein |first1=Beate |last2=Haugum |first2=Siri Vatsø |title=The northernmost sightings of Humpback whales |journal=Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology |date=2018 |volume=10:1 |pages=5–8 |url=http://www.oers.ca/journal/volume10/issue1/communication.pdf |access-date=2019-06-17 |archive-date=2019-06-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190617095824/http://www.oers.ca/journal/volume10/issue1/communication.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Humpbacks feed and breed near coasts and over ]. Their winter breeding grounds are located around the tropics while their summer feeding groups are found in temperature and polar areas, even reaching the ice edges of both the Arctic and Antarctic. Humpbacks go on vast ] between their feeding and breeding areas, often crossing ]s. The species has been recorded traveling up to {{convert|8000|km|abbr=on}} in one direction.{{R|Jefferson}} A unique, non-migratory population feeds and breeds in the northern Indian Ocean mainly in the ] around ].{{r|NOAA}} This population has also been recorded in the ], the ] and off the coasts of Pakistan and India.{{R|arabian}} | ||

| In the North Atlantic, there are two separate wintering populations, one in the ], from Cuba to northern Venezuela, and the other at the ] and northwest Africa. The summer grounds of the West Indies humpbacks are primarily off ], eastern Canada and western ], while the Cape Verde population feeds around Iceland and Norway. There is some overlap in the summer ranges of these populations and West Indies humpbacks have been documented feeding further east.{{r|NOAA}} Whale visits into the ] have been infrequent, but occurred in the gulf historically.{{R|texas}} They were considered to be uncommon in the ], but increased sightings, including re-sightings, indicate that more whales may colonize or recolonize it in the future.{{R|Panigada}} | In the North Atlantic, there are two separate wintering populations, one in the ], from Cuba to northern Venezuela, and the other at the ] and northwest Africa. The summer grounds of the West Indies humpbacks are primarily off ], eastern Canada and western ], while the Cape Verde population feeds around Iceland and Norway. There is some overlap in the summer ranges of these populations and West Indies humpbacks have been documented feeding further east.{{r|NOAA}} Whale visits into the ] have been infrequent, but occurred in the gulf historically.{{R|texas}} They were considered to be uncommon in the ], but increased sightings, including re-sightings, indicate that more whales may colonize or recolonize it in the future.{{R|Panigada}} | ||

Revision as of 02:47, 21 March 2022

Large baleen whale with long pectoral fins and a knobbly head

| Humpback whale Temporal range: 20–0 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N Early Miocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) | |

| CITES Appendix I (CITES) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenopteridae |

| Genus: | Megaptera Gray, 1846 |

| Species: | M. novaeangliae |

| Binomial name | |

| Megaptera novaeangliae Borowski, 1781 | |

| |

| Humpback whale range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is a species of baleen whale. It is one of the larger rorqual species, with adults ranging in length from 14–17 m (46–56 ft) and weighing up to 40 metric tons (44 short tons). The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with long pectoral fins and a knobbly head. It is known for breaching and other distinctive surface behaviors, making it popular with whale watchers. Males produce a complex song typically lasting 4 to 33 minutes. All the males in a group will produce the same song, which is different each season.

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 16,000 km (9,900 mi) each year. They feed in polar waters, and migrate to tropical or subtropical waters to breed and give birth. Their diet consists mostly of krill and small fish. Humpbacks have a diverse repertoire of feeding methods, including the bubble net technique.

Like other large whales, the humpback was a target for the whaling industry. The species was once hunted to the brink of extinction; its population fellto around 5,000 by the 1960s. While numbers have partially recovered to some 80,000 animals worldwide, entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships and noise pollution continue to affect the species.

Taxonomy and genetics

The humpback was first identified as baleine de la Nouvelle Angleterre by Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Regnum Animale of 1756. In 1781, Georg Heinrich Borowski described the species, converting Brisson's name to its Latin equivalent, Balaena novaeangliae. In 1804, Lacépède shifted the humpback from the family Balaenidae, renaming it B. jubartes. In 1846, John Edward Gray created the genus Megaptera, classifying the humpback as Megaptera longipinna, but in 1932, Remington Kellogg reverted the species names to use Borowski's novaeangliae. The common name is derived from the curving of their backs when diving. The generic name Megaptera from the Ancient Greek mega- μεγα ("giant") and ptera/ πτερα ("wing"), refers to their large front flippers. The specific name means "New Englander" and was probably given by Brisson due to regular sightings of humpbacks off the coast of New England.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A phylogenetic tree of six baleen whale species |

Humpback whales are rorquals, members of the Balaenopteridae family that includes the blue, fin, Bryde's, sei and minke whales. A 2018 genomic analysis estimates that rorquals diverged from other baleen whales in the late Miocene, between 10.5 and 7.5 million years ago. The humpback and fin whale were found to be sister taxon. There is reference to a humpback-blue whale hybrid in the South Pacific, attributed to marine biologist Michael Poole.

Modern humpback whale populations appear to have originated in the southern hemisphere around 880,000 years ago and colonized the northern hemisphere 200,000–50,000 years ago. A 2014 genetic study suggested that the separate populations in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Oceans have had limited gene flow and are distinct enough to be subspecies, with the scientific names of M. n. novaeangliae, M. n. kuzira and M. n. australis respectively. A non-migratory population in the Arabian sea has been islolated for 70,000 years.

Description

Adult humpback whales are generally 14–15 m (46–49 ft), though longer lengths of 16–17 m (52–56 ft) are recorded. Females are usually 1–1.5 m (3 ft 3 in – 4 ft 11 in) longer than males. The species can reach body masses of 40 metric tons (44 short tons). Calves are born around 4.3 m (14 ft) long and weighing 680 kg (1,500 lb).

The humpback whale has a highly narrow rostrum, robust body and proportionally long flippers (around one-third its body length). The dorsal fin is generally small but varies in shape from low and almost non-existent to relatively high and curved. As with other rorquals, the humpback has a series of grooves stretching from the tip of the lower jaw to the navel. They are fewer in number in this species, ranging from 14–35. Humpbacks have 270–400 baleen plates on both sides of the mouth.

Unique among large whales, humpback have bumps or tubercles on the upper and lower jaw and front edge of the flippers, while the tail fluke has a serrated trailing edge. The tubercles on the head are 5–10 cm (2.0–3.9 in) in diameter at the base and can protude 6.5 cm (2.6 in) up. They have a funnel-shaped pit in the center which usually contains at least one fragile hair which is 1–3 cm (0.39–1.18 in) long (above the skin) and 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) in diameter. The tubercles may have a sensory function as they are highly innervated and develop early on the womb.

The dorsal or upper-side of the animal is generally black while the ventral or underside is black, white and mottled in pigmentation. Whales in the southern hemisphere tend to have more white on the underside. The flippers can vary from all white to white only on the ventral surface. The varying color patterns and scars on the tail flukes distinguish individual animals. The female has a hemispherical lobe about 15 cm (5.9 in) in diameter in her genital region. This visually distinguishes males and females.

Behavior and ecology

Humpback whales normally associate in small, unstable groups, though large aggregations form during feeding and among males competing for females. Humpbacks may interact with other cetacean species, such as right whales, fin whales and bottlenose dolphins. Humpbacks can be highly active at the surface, performing aerial behaviors such as breaching, tail slapping (lobtailing) and flipper slapping. These may serve various functions such as play, communication, parasite removal, and displaying excitement or annoyance.

Humpbacks rest at the surface in a horizontal position. The species is a slower swimmer than other rorquals, cruising at 7.9–15.1 km/h (4.9–9.4 mph). When treatened, a humpback may speed up to 27 km/h (17 mph). They appear to dive within 150 m (490 ft) and rarely below 120 m (390 ft). Dives typically last less than five minutes during the summer and average 15–20 minutes during the winter. When making a dive, a humpback often raises up its tail fluke, exposing the underside.

Feeding

Humpback whales feed from spring to fall. They have a generalist diet, their main food items being krill and small schooling fish. In the southern hemisphere, the most common krill species eaten is the Antarctic krill, while in other places, the northen krill and various species of Euphausia and Thysanoessa are taken. Fish species consumed include herring, capelin, sand lances and Atlantic mackerel. Like other rorquals, humpbacks are "gulp feeders", that is, they take in a single mouthful of food at a time, as opposed to the continuous filter-feeding of right whales and bowhead whales. During feeding, the grooves expand, allowing the whale to increase its gape.

The humpback has the most diverse hunting repertoire of all baleen whales. Its most inventive technique is known as bubble net feeding; a group of whales dive up to 20 m (66 ft) below the surface and swim in a shrinking circle blowing air from their blowholes creating vertical cylinder-ring of bubbles that captures the prey above them. Humpbacks use two main behaviors to create bubble-netting; upward spirals and double loops. Upward spirals involve the whales blowing continuously as they circle towards the surface, creating a spiral of bubble. Double loops consist of a deep, long loop that corrals the prey followed by lobtailing at the surface and then a smaller loop that serves to make the final capture of the prey. After the nets are created, humpbacks swimming into them with their mouth gaping and ready to swallow.

Using network-based diffusion analysis, one study argued that whales learned lobtailing from other whales in the group over a period of 27 years in response to a change in the primary form of prey. The tubercles on the flippers appear to delay the angle of attack while maximizing lift and decreasing drag (see tubercle effect). This, along with the long and narrow design of the flippers, allows the whales to make the sharp turns necessary during bubble-feeding. Whales in the southern hemisphere have been recorded feeding in large tightly-spaced groups with 20–200 individuals.

Courtship and reproduction

See also: Whale reproduction

Mating and breeding takes place during the winter months. Females go through estrus while males reach peak testosterone and sprem levels. Humpback whales are promiscuous, with both sexes having multiple partners. Males will frequently trail both single females and cow-calf pairs. These are known as "escorts" and the male that is closest to the female and doing the most aggressive behavior to the other males is known as the "principal escort" while those fighting for his position are known as "challengers". Other following males that are not directly competing to be next to the female are called "secondary escorts". Aggressive behavior between males include tail slashing, ramming and head-butting.

Gestation in the species is around 11.5 months and females reproduce every two years. Humpback whale births have been rarely observed. One birth witnessed off Madagascar occurred within four minutes. Birthing mostly takes place in mid-winter, usually to a single calf. Calves suckle for up to a year but can feed independently by six months. Humpback reach sexual maturity at 5–10 years depending on the population.

Vocalizations

Further information: Whale_vocalization § Song of the humpback whale

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Male humpback whales produce complex songs during the winter breeding season. These vocals range in frequency from 100 Hz to 4 Hz, with harmonics of at least 24 kHz, and can travel around 10 km (6.2 mi). Males may sing between 4 and 33 minutes depending on the region. In Hawaii, vocalizations have been recorded lasting 420 minutes. Songs are divided them into layers; "sub-units", "units", "subphrases", "phrases", "themes" , "songs". A subunit is defined as frequency discontinuities or inflections points while full units are the shortest sounds that appear continuous to the human ear, similar to a musical note. When one or more units are repeated in a series, it creates a subphrase and multiple subphrases are grouped as phrases. Similar-sounding phrases repeated in an unbroken sequence are grouped as themes and multiple distinct themes create a song.

The function of these songs has been debated; but they may have multiple purposes. There is little evidence to suggest that songs establish dominance among males, but there have been observations of non-singing males interrupting singers, possibly as an aggressive act. Those who join singers are almost always lone males who were not previously singing. Females do not appear to visit individual singers, but they may be attracted to aggregations of singing males much like a lek mating system. Another possibility is that songs recruit other individual whales to new wintering grounds. It has also been suggested that humpback whale songs have echolocative properties and may serve to locate other whales.

Whale songs are similar among males in acoustic contact with one another at a specific time and place. Individual males may alter their songs over time and these changes are copied by others in contact with them. They have been shown in some cases to spread "horizontally" between neighboring populations over the course of successive breeding seasons. In the northern hemisphere, song appear to slowly evolve over time while southern hemisphere song go through periodic "revolutions" which quickly spread.

Humpback whales are recorded to make other vocalizations. "Snorts" are short low-frequency sounds that are commonly heard among adult pairs, groups with multiple adults and one calf and groups of multiple adults with no calves. These likely function in regulating social interactions within these groups. "Grumbles" are similar in frequency to snorts but longer and are more often heard in group compositions with at least one adult male. They appear to signal body size, and may serve to establish social roles among males in a group. "Thwops" and "wops" are vocals with high frequency modulations, the former are produced by lone males seeking a group while the latter appear to serve as contact calls between mothers and calves. High pitched "cries" and "violins" and modulated "shrieks" are normally heard in groups with multiple adults, particularly males, and are associated with competition and aggression. Short, low frequency "grunts" and short, modulated "barks" are produce during group joinings.

Predation

Visible scars indicate that orcas can prey upon juvenile humpbacks. A 2014 study off Western Australia observed that when available in large numbers, young humpbacks can be attacked and sometimes killed by orcas. Moreover, mothers and (possibly related) adults escort neonates to deter such predation. The suggestion is that when humpbacks suffered near-extinction during the whaling era, orcas turned to other prey, but are now resuming their former practice. There is also evidence that humpback whales will defend against or mob killer whales who are attacking either humpback calves or juveniles as well as members of other species, including seals. The humpback's protection of other species may be unintentional, a "spillover" of mobbing behavior intended to protect members of its own species. The powerful flippers of humpback whales, which are often infested with large, sharp barnacles, are formidable weapons against orcas. When threatened, they will flail their flippers and flukes, keeping the orcas at bay.

The great white shark is another confirmed predator of the humpback whale. In 2020, Marine biologists Dines and Gennari et al., published a documented incident of a group of great white sharks exhibiting pack-like behavior to successfully attack and kill a live adult humpback whale. A second incident regarding great white sharks killing humpback whales was documented off the coast of South Africa. The shark recorded instigating the attack was a female nicknamed "Helen". Working alone, the shark attacked a 33 ft (10 m) emaciated and entangled humpback whale by attacking the whale's tail to cripple and bleed the whale before she managed to drown the whale by biting onto its head and pulling it underwater.

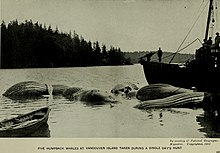

Range

Humpback whales have a near cosmopolitan distribution, being absent only from some enclosed seas and parts of the High Arctic. The furthest north they have been recorded is at 81°N around southern Franz Josef Land. Humpbacks feed and breed near coasts and over continental shelves. Their winter breeding grounds are located around the tropics while their summer feeding groups are found in temperature and polar areas, even reaching the ice edges of both the Arctic and Antarctic. Humpbacks go on vast migrations between their feeding and breeding areas, often crossing oceanic zones. The species has been recorded traveling up to 8,000 km (5,000 mi) in one direction. A unique, non-migratory population feeds and breeds in the northern Indian Ocean mainly in the Arabian Sea around Oman. This population has also been recorded in the Gulf of Aden, the Persian Gulf and off the coasts of Pakistan and India.

In the North Atlantic, there are two separate wintering populations, one in the West Indies, from Cuba to northern Venezuela, and the other at the Cape Verde Islands and northwest Africa. The summer grounds of the West Indies humpbacks are primarily off New England, eastern Canada and western Greenland, while the Cape Verde population feeds around Iceland and Norway. There is some overlap in the summer ranges of these populations and West Indies humpbacks have been documented feeding further east. Whale visits into the Gulf of Mexico have been infrequent, but occurred in the gulf historically. They were considered to be uncommon in the Mediterranean Sea, but increased sightings, including re-sightings, indicate that more whales may colonize or recolonize it in the future.

The North Pacific has at least four breeding populations: off Mexico (including Baja California and the Revillagigedos Islands), Central America, the Hawaiian Islands and both Okinawa and the Philippines. The Mexican population has a broad feeding range stretching from the Aleutian Islands to California, with higher aggregations in the Bering sea, northern and western Gulf of Alaska, southern British Columbia to northern Washington State, and from Oregon to California. Central American humpbacks feed almost exclusively off Oregon and California, while Hawaiian humpbacks mainly feed off southeast Alaska and northern British Columbia. The wintering grounds of the Okinawa/Philippines population is primary around the Russian Far East. There is some evidence for a fifth population somewhere in the northwestern Pacific. There have been sightings of whales feeding off the Aleutians that haven't been linked to the known populations. This population may pass though the Ogasawara area on route to an unidentified breeding area further south.

Southern Hemisphere

In the Southern Hemisphere, humpback whales are divided into seven breeding stocks, some of which are further divided into sub-structures. These include the southeastern Pacific (stock G), southwestern Atlantic (stock A), southeastern Atlantic (stock B), southwestern Indian Ocean (stock C), southeastern Indian Ocean (stock D), southwestern Pacific (stock E) and the Oceania stock (stocks E-F). Stock G breeds in tropical and subtropical waters off the west coast of Central and South America and feed along the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula and the South Orkney Islands, although some do not travel that far and instead feed off Southern Chile's Tierra del Fuego. Stock A winters from the northern to southeastern Brazil and migrate to their summer grounds around the South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Some stock A individuals have also been recording off the western Antarctic Peninsula suggesting an increased blurring of the boundaries between A and G's feeding areas.

Stock B breeds on the west coast of Africa and is further divided into Bl and B2 subpopulations, the former ranging from the Gulf of Guinea to Angola and the latter ranging from Angola to western South Africa. Stock B feeds in waters to the southwest of Africa, mainly around Bouvet Island. Comparison of songs between those at Cape Lopez and Abrolhos Archipelago indicate that trans-Atlantic mixings between Stock A and B whales occur. Stock C whales winter around southeastern Africa and surrounding waters. This stock is further divided into C1, C2 and C3 subpopulations; C1 occurs around Mozambique and eastern South Africa, C2 around the Comoro Islands and C3 off the southern and eastern coast of Madagascar. The feeding range of this population is likely in multiple localities surrounding an area bordered by y 5°W and 60°E and under 50°N. There may be overlap in the feeding areas of stocks B and C.

Stock D whales breed off the western coast of Australia and their primarily feeding area is the southern Kerguelen plateau. Stock E is divided into E1, E2 and E3 stocks. E1 whales have breeding ranges that stretch along the east coast of Australia and around Tasmania, while their feed range is close to Antarctica mainly within 130°E and 170°W. The Oceania stock is divided into the New Caledonia (E2), Tonga (E3), Cook Islands (F1) and French Polynesia (F2) subpopulations. This stock's feeding grounds mainly range from around the Ross sea to the Antarctic Peninsula.

Relation to humans

Whaling

Main article: Whaling See also: Whaling in Japan

Humpback whales were hunted as early as the late 16th century. They were often the first species to be harvested in an area due to this coastal distribution. Prior to commercial whaling, populations could have reached 125,000. North Pacific kills alone are estimated at 28,000.during the 20th century. In the same peroid over 200,000 humpbacks were taken in the Southern Hemisphere. North Atlantic populations dropped to as low as 700 individuals. In 1946, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was founded to oversee the industry. They imposed hunting regulations and created hunting seasons. To prevent extinction, IWC banned commercial humpback whaling in 1966. By then, the global population had been reduced to around 5,000. The Soviet Union deliberately under-recorded its catches; the Soviets reported catching 2,820 between 1947 and 1972, but the true number was over 48,000.

As of 2004, hunting was restricted to a few animals each year off the Caribbean island of Bequia in the nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The take is not believed to threaten the local population. Japan had planned to kill 50 humpbacks in the 2007/08 season under its JARPA II research program. The announcement sparked global protests. After a visit to Tokyo by the IWC chair asking the Japanese for their co-operation in sorting out the differences between pro- and antiwhaling nations on the commission, the Japanese whaling fleet agreed to take no humpback whales during the two years it would take to reach a formal agreement. In 2010, the IWC authorized Greenland's native population to hunt a few humpback whales for the following three years.

Whale-watching

Main article: Whale watchingMuch of the growth of the commerical whale watching was built on the humpback whale. The species' highly active surface behaviors and tendency to because accustomed to boats, has made them easy to observe particulary for photographers. Humpback whale tours were established in New England and Hawaii starting in 1975. This business brings in revenue of $20 million per year for the Hawaii's economy. While Hawaiian tours have tended to be mosly commerical, New England whale watching tours have introduced educational components. California was also introduce school childern to wild whales with educational programs.

Status

Conservation

As of 2018, the worldwide population is estimated at 84,000 and increasing. Regional estimates are 18,000–20,000 in the North Pacific, 12,000 in the North Atlantic and over 50,000 in the Southern Hemisphere, down from a prewhaling population of 125,000.

The NOAA is committed to protecting and recovering the humpback whale. NOAA enacted vessel speed restrictions which serve to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whale and many other species of whales. They respond to dead, injured, or entangled whales. They also educate whale watchers, tourists, and vessel operators on responsible viewing of the humpback whales. NOAA works to develop methods to reduce vessel strikes and reduce risk of entanglement in fishing gear. The NOAA's work will help reduce the number of humpback whale deaths.

In August 2008, the International Union for Conservation of Nature changed humpbacks' status from vulnerable to least concern, although two subpopulations remain endangered. The United States is considering listing separate humpback populations, so smaller groups, such as North Pacific humpbacks, which are estimated to number 18,000–20,000 animals, might be delisted. This is made difficult by humpbacks’ migrations, which can extend 5,157 miles (8,299 km) from Antarctica to Costa Rica. In Costa Rica, the Ballena Marine National Park is designed for humpback protection. Areas where population data is limited and the species may be at higher risk include the Arabian Sea, the western North Pacific Ocean, the west coast of Africa and parts of Oceania.

The species was listed as vulnerable in 1996 and endangered as recently as 1988. Most monitored stocks have rebounded since the end of commercial whaling. In the North Atlantic stocks are believed to be approaching prehunting levels. However, the species is considered endangered in some countries, including the United States.

United States

A 2008 US Department of Commerce analysis (SPLASH) noted that the many challenges to determining the recovery status included the lack of accurate population estimates, the unexpected complexity of population structures and their migration. The report was based on data collected from 2004 to 2006. At the time, the North Pacific population was some 18,302. The estimate is consistent with a moderate rate of recovery for a depleted population, although it was considered to be a "dramatic increase in abundance" from other post-1960s estimates. By comparison, Calambokidis et al. estimated 9,819, covering 1991–1993. This represents a 4% annual increase in population from 1993 to 2006. The sanctuary provided by US national parks, such as Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve and Cape Hatteras National Seashore, became major factors in population recovery.

Canada

Off the west coast of Canada, the Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve covers 3,400 square kilometres (1,300 sq mi). It is "a primary feeding habitat" of the North Pacific population. Their critical habitat overlaps with tanker shipping routes between Canada and its eastern trade partners. In 2005 the North Pacific population was listed as threatened under Canada's Species at Risk Act (SARA). On April 19, 2014 the Department of the Environment recommended an amendment to SARA to downgrade their status off the Pacific coast from "threatened" to "species of special concern". According to Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), the North Pacific humpback population increased at about 4% annually from 1992 to 2008. Although socioeconomic costs and benefits were considered in their decision to upgrade their status, according to the University of British Columbia's Marine Mammal Research Consortium's research director, the decision was based on biology, not politics.

Threats

Whaling no longer threatens the species, but individuals are vulnerable to collisions with ships, entanglement in fishing gear and noise pollution. Like other cetaceans, humpbacks can be injured by excessive noise. In the 19th century, two humpback whales were found dead near sites of repeated oceanic sub-bottom blasting, with traumatic injuries and fractures in the ears.

Whale researchers along the Atlantic Coast report that there have been more stranded whales with signs of vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglement in recent years than ever before. The NOAA recorded 88 stranded humpback whales between January 2016 and February 2019. This is more than double the number of whales stranded between 2013 and 2016. Because of the increase in stranded whales NOAA declared an unusual mortality event in April 2017. This declaration still stands. Virginia Beach aquarium's stranding response coordinator, Alexander Costidis says the conclusions are that the two causes of these unusual mortality events are vessel interactions and entanglements.

Saxitoxin, a paralytic shellfish poisoning from contaminated mackerel, has been implicated in humpback whale deaths. While oil ingestion is a risk for whales, a 2019 study found oil did not foul baleen, and instead was easily rinsed from baleen by flowing water.

Notable individuals

The Tay whale

Main article: Tay Whale

In December 1883, a male humpback swam up the Firth of Tay in Scotland, past what was then the whaling port of Dundee. Harpooned during a failed hunt, it was found dead off of Stonehaven a week later. Its carcass was exhibited to the public by a local entrepreneur, John Woods, both locally and then as a touring exhibition that traveled to Edinburgh and London. The whale was dissected by Professor John Struthers, who wrote seven papers on its anatomy and an 1889 monograph on the humpback.

Migaloo

"Migaloo" redirects here. For the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society anti-whaling campaign, see Operation Migaloo. See also: Whale watching in Australia

An albino humpback whale that travels up and down the east coast of Australia became famous in local media because of its rare, all-white appearance. Migaloo is the only known Australian all-white specimen and is a true albino. First sighted in 1991, the whale was named for an indigenous Australian word for "white fella". To prevent sightseers approaching dangerously close, the Queensland government decreed a 500-m (1600-ft) exclusion zone around him.

Migaloo was last seen in June 2014 along the coast of Cape Byron in Australia. Migaloo has several physical characteristics that can be identified; his dorsal fin is somewhat hooked, and his tail flukes have a unique shape, with edges that are spiked along the lower trailing side.

Humphrey

Main article: Humphrey the WhaleIn 1985, Humphrey swam into San Francisco Bay and then up the Sacramento River towards Rio Vista. Five years later, Humphrey returned and became stuck on a mudflat in San Francisco Bay immediately north of Sierra Point below the view of onlookers from the upper floors of the Dakin Building. He was twice rescued by the Marine Mammal Center and other concerned groups in California. He was pulled off the mudflat with a large cargo net and the help of the US Coast Guard. Both times, he was successfully guided back to the Pacific Ocean using a "sound net" in which people in a flotilla of boats made unpleasant noises behind the whale by banging on steel pipes, a Japanese fishing technique known as oikami. At the same time, the attractive sounds of humpback whales preparing to feed were broadcast from a boat headed towards the open ocean.

See also

References

- Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Fossilworks: Megaptera". Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Cooke, J.G. (2018). "Megaptera novaeangliae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T13006A50362794. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T13006A50362794.en. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Martin, Stephen (2001). The Whales' Journey. Allen & Unwin. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-86508-232-5.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (2 February 2015). Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged. Martino Fine Books. ISBN 978-1-61427-770-5.

- ^ Árnason, U.; Lammers, F.; Kumar, V.; Nilsson, M. A.; Janke, A. (2018). "Whole-genome sequencing of the blue whale and other rorquals finds signatures for introgressive gene flow". Science Advances. 4 (4): eaap9873. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.9873A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aap9873. PMC 5884691. PMID 29632892.

- Reeves, R. R.; Stewart, P. J.; Clapham, J.; Powell, J. A. (2002). Whales, dolphins, and porpoises of the eastern North Pacific and adjacent Arctic waters: A guide to their identification. New York: Knopf. pp. 234–237.

- Hatch, L. T.; Dopman, E. B.; Harrison, R. G. (2006). "Phylogenetic relationships among the baleen whales based on maternally and paternally inherited characters". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 41 (1): 12–27. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.023. PMID 16843014.

- Jackson, Jennifer A.; Steel, Debbie J.; Beerli, P.; Congdon, Bradley C.; Olavarría, Carlos; Leslie, Matthew S.; Pomilla, Cristina; Rosenbaum, Howard; Baker, C Scott (2014). "Global diversity and oceanic divergence of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1786). doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3222.

- Pomilla, Cristina; Amaral, Ana R.; Collins, Tim; Minton, Gianna; Findlay, Ken; Leslie, Matthew S.; Ponnampalam, Louisa; Baldwin, Robert; Rosenbaum, Howard (2014). "The World's Most Isolated and Distinct Whale Population? Humpback Whales of the Arabian Sea". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e114162. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114162.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Clapham, Phillip J. (26 February 2009). "Humpback Whale Megaptera novaeangliae". In Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J.G.M. 'Hans' (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 582–84. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas A.; Webber, Marc A.; Pitman, Robert L. (2015). Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 79–83. ISBN 978-0-12-409542-7.

- ^ Final Recovery Plan for the Humpback Whale (Megapten Novaeangliae) (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1991. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ Clapham, Phillip J.; Mead, James G. (1999). "Megaptera novaeangliae" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 604 (604): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504352. JSTOR 3504352.

- Mercado III, Eduardo (2014). "Tubercles: What Sense Is There?" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 40 (1): 95–103. doi:10.1578/AM.40.1.2014.95.

- Katona S.K.; Whitehead, H.P. (1981). "Identifying humpback whales using their mural markings". Polar Record. 20 (128): 439–444. doi:10.1017/s003224740000365x.

- Kaufman G.; Smultea M.A.; Forestell P. (1987). "Use of lateral body pigmentation patterns for photo ID of east Australian (Area V) humpback whales". Cetus. 7 (1): 5–13.

- ^ Clapham, P.J. (1996). "The social and reproductive biology of humpback whales: an ecological perspective" (PDF). Mammal New Studies. 26 (1): 27–49. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1996.tb00145.x.

- "Instituto Baleia Jubarte". www.baleiajubarte.org.br. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- Joseph R Mobley (1 January 1996). "Fin Whale Sighting North of Kaua'i, Hawai'i". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Deakos, Mark H.; et al. (2010). "Two Unusual Interactions Between a Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and a Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Hawaiian Waters". Aquatic Mammals. 36 (2): 121–28. doi:10.1578/AM.36.2.2010.121.

- Iwata, Takashi; Biuw, Martin; Aoki, Kagari; O’Malley Miller, Patrick James; Sato, Katsufumi (2021). "Using an omnidirectional video logger to observe the underwater life of marine animals: Humpback whale resting behaviour". Behavioural Processes. 186: 104369. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2021.104369. PMID 33640487. S2CID 232051037.

- Dolphin, William Ford (1987). "Ventilation and dive patterns of humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, on their Alaskan feeding grounds". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 65 (1): 83–90. doi:10.1139/z87-013.

- ^ Humpback Whale Recovery Team (1991). Recovery Plan for the Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Marine Fisheries Service. p. 105.

- Friedlaender, Ari; Bocconcelli, Alessandro; Wiley, David; Cholewiak, Danielle; Ware, Colin; Weinrich, Mason; Thompson, Michael (2011). "Underwater components of humpback whale bubble-net feeding behaviour". Behaviour. 148 (5–6): 575–602. doi:10.1163/000579511x570893.

- Allen, Jenny; Weinrich, Mason; Hoppitt, Will; Rendell, Luke (26 April 2013). "Network-Based Diffusion Analysis Reveals Cultural Transmission of Lobtail Feeding in Humpback Whales". Science. 340 (6131): 485–8. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..485A. doi:10.1126/science.1231976. PMID 23620054. S2CID 206546227.

- Lee, Jane J. (April 25, 2013). "Do Whales Have Culture? Humpbacks Pass on Behavior". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- Fish, Frank E.; Weber, Paul W.; Murray, Mark M.; Howle, Laurens E. (2011). "The Tubercles on Humpback Whales' Flippers: Application of Bio-Inspired Technology". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 51 (1): 203–213. doi:10.1093/icb/icr016.

- Findlay, Ken P.; Seakamela, S. Mduduzi; Meÿer, Michael A.; Kirkman, Stephen P.; Barendse, Jaco; Cade, David E.; Hurwitz, David; Kennedy, Amy S.; Kotze, Pieter G. H.; McCue, Steven A.; Thornton, Meredith; Vargas-Fonseca, O. Alejandra; Wilke, Christopher G. (2017). "Humpback whale "super-groups" – A novel low-latitude feeding behaviour of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Benguela Upwelling System". PLOS ONE. 12 (3): e0172002. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Clapham, Phillip J.; Palsbøll, Per J. (1997-01-22). "Molecular analysis of paternity shows promiscuous mating in female humpback whales ( Megaptera novaeangliae, Borowski)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 264 (1378): 95–98. Bibcode:1997RSPSB.264...95C. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0014. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1688232. PMID 9061965.

- Herman, Elia Y. K.; Herman, Louis M.; Pack, Louis M.; Marshall, Greg; Shepard, C. Michael; Bakhtiari, Mehdi (2007). "When Whales Collide: Crittercam Offers Insight into the Competitive Behavior of Humpback Whales on Their Hawaiian Wintering Grounds". Marine Technology Society Journal. 41 (4): 35–43. doi:10.4031/002533207787441971.

- Faria, Maria-Alejandra (2013-09-01). "Short Note: Observation of a Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Birth in the Coastal Waters of Sainte Marie Island, Madagascar". Aquatic Mammals. 39 (3): 296–305. doi:10.1578/am.39.3.2013.296. ISSN 0167-5427.

- ^ Herman, Louis M. (2017). "The multiple functions of male song within the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) mating system: review, evaluation, and synthesis". Biological Reviews. 92 (3): 1795–1818. doi:10.1111/brv.12309.

- ^ Cholewiak, Danielle (2012). "Humpback whale song hierarchical structure: Historical context and discussion of current classification issues". Marine Mammal Science. 173 (3997): E312 – E332. doi:10.1126/science.173.3997.585.

- Mercado III, Eduardo (2021). "Intra-individual variation in the songs of humpback whales suggests they are sonically searching for conspecifics". Learning & Behavior. doi:10.3758/s13420-021-00495-0.

- Garland EC; Goldizen AW; Rekdahl ML; Constantine R; Garrigue C; Hauser ND; et al. (2011). "Dynamic horizontal cultural transmission of humpback whale song at the ocean basin scale". Curr Biol. 21 (8): 687–91. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.019. PMID 21497089.

- Zandberg, L.; Lachlan, R. F.; Lamoni, L.; Garland, E. C. (2021). "Global cultural evolutionary model of humpback whale song". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: BIological Science. 376 (1836): 20200242. doi:10.1098/rstb.2020.0242.

- Dunlop, Rebecca A.; Cato, Douglas H.; Noad, Michael J. (2008). "Non-song acoustic communication in migrating humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae)". Marine Mammal Science. 24 (3): 613–629. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00208.x.

- Pitman, R. L.; Totterdell, J; Fearnbach, H; Ballance, L. T.; Durban, J. W.; Kemps, H (2014). "Whale killers: Prevalence and ecological implications of killer whale predation on humpback whale calves off Western Australia". Marine Mammal Science. 31 (2): 629–657. doi:10.1111/mms.12182.

- Pitman, Robert L. (2016). "Humpback whales interfering when mammal-eating killer whales attack other species: Mobbing behavior and interspecific altruism?". Marine Mammal Science. 33: 7–58. doi:10.1111/mms.12343.

- Dines, Sasha; Gennari, Enrico (September 9, 2020). "First observations of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) attacking a live humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)". Marine and Freshwater Research. 71 (9): 1205–1210. doi:10.1071/MF19291. S2CID 212969014. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021 – via www.publish.csiro.au.

- "Drone footage shows a great white shark drowning a 33ft humpback whale". The Independent. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Fish, Tom (15 July 2020). "Shark attack: Watch 'strategic' Great White hunt down and kill 10 Metre humpback whale". Express.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Zein, Beate; Haugum, Siri Vatsø (2018). "The northernmost sightings of Humpback whales" (PDF). Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology. 10:1: 5–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-17. Retrieved 2019-06-17.

- ^ Bettridge, Shannon; Baker, C. Scott; Barlow, Jay; Clapham, Phillip J.; Ford, Michael; Gouveia, David; Mattila, David K.; Pace, Richard M. III; Rosel, Patricia E.; Silber, Gregory K.; Wade, Paul R. (March 2015). Status review of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) under the Endangered Species Act (PDF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Mikhalev, Yuri A. (April 1997). "Humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae in the Arabian Sea" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 149: 13–21. Bibcode:1997MEPS..149...13M. doi:10.3354/meps149013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- Weller, David W. (1 January 1996). "First account of a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Texas waters, with a re-evaluation of historical records from the Gulf of Mexico". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Panigada, Simone; Frey, Sylvia; Pierantonio, Nino; Garziglia, Patrice; Giardina, Fabio (1 April 2014). Are humpback whales electing the Mediterranean Sea as new residence?. 28th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society. Liege, Belgium. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- Marcondes, M. C. C.; Cheeseman, T.; Jackson, J. A.; Friedlaender, A. S.; Pallin, L.; Olio, M.; Wedekin, L. L.; Daura-Jorge, F. G.; Cardoso, J.; Santos, J. D. F.; Fortes, R. C.; Araújo, M. F.; Bassoi, M.; Beaver, V.; Bombosch, A.; Clark, C. W.; Denkinger, J.; Boyle, A.; Rasmussen, K.; Savenko, O.; Avila, I. C.; Palacios, D. M.; Kennedy, A. S.; Sousa-Lima, R. S. (2021). "The Southern Ocean Exchange: porous boundaries between humpback whale breeding populations in southern polar waters". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 23618. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-02612-5.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Howard C.; Pomilla, Cristina; Mendez, Martin; Leslie, Matthew S.; Best, Peter B.; Findlay, Ken P.; Minton, Gianna; Ersts, Peter J.; Collins, Timothy; Engel, Marcia H.; Bonatto, Sandro L.; Kotze, Deon P. G. H.; Meÿer, Mike; Barendse, Jaco; Thornton, Meredith; Razafindrakoto, Yvette; Ngouessono, Solange; Vely, Michael; Kiszka, Jeremy (2009). "Population Structure of Humpback Whales from Their Breeding Grounds in the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7318. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007318.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Darling, J. D.; Sousa-Lima, R. S. (2005). "Notes: Songs Indicate Interaction Between Humpback Whale (Megaptera Novaeangliae) Populations in the Western and Eastern South Atlantic Ocean". Marine Mammal Science. 21 (3): 557–566. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01249.x.

- Bestley, Sophie; Andrews-Goff, Virginia; van Wijk, Esmee; Rintoul, Stephen R.; Double, Michael C.; How, Jason (2019). "New insights into prime Southern Ocean forage grounds for thriving Western Australian humpback whales". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 13988. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-50497-2.

- Andrews-Goff, V.; Bestley, S.; Gales, N. J.; Laverick, S. M.; Paton, D.; Polanowski, A. M.; Schmitt, N. T.; Double, M. C. (2018). "Humpback whale migrations to Antarctic summer foraging grounds through the southwest Pacific Ocean". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 12333. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30748-4.

- Steel, D.; Anderson, M.; Garrigue, C.; Olavarría, C.; Caballero, S.; Childerhouse, S.; Clapham, P.; Constantine, R.; Dawson, S.; Donoghue, M.; Flórez-González, L.; Gibbs, N.; Hauser, N.; Oremus, M.; Paton, D.; Poole, M. M.; Robbins, J.; Slooten, L.; Thiele, D.; Ward, J.; Baker, C. S. (2018). "Migratory interchange of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) among breeding grounds of Oceania and connections to Antarctic feeding areas based on genotype matching". Polar Biology. 41 (4): 653–662. doi:10.1007/s00300-017-2226-9.

- Baker, CS; Perry, A; Bannister, JL; Weinrich, MT; Abernethy, RB; Calambokidis, J; Lien, J; Lambertsen, RH; Ramírez, JU (September 1993). "Abundant mitochondrial DNA variation and world-wide population structure in humpback whales". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 90 (17): 8239–8243. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.8239B. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.17.8239. PMC 47324. PMID 8367488.

Before protection by international agreement in 1966, the world-wide population of humpback whales had been reduced by hunting to <5000, with some regional subpopulations reduced to <200...

- Prof. Alexey V. Yablokov (1997). "On the Soviet Whaling Falsification, 1947–1972". Whales Alive!. 6 (4). Cetacean Society International. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- scoop.co.nz: Leave Humpback Whales Alone Message To Japan Archived 2007-07-09 at the Wayback Machine 16 May 2007

- Hogg, Chris (2007-12-21). "Japan changes track on whaling". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2007-12-26. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- "Greenland: Humpback Whales Are Deemed Eligible For Hunting". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 26 June 2010. p. 7. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Hoyt, Erich (26 February 2009). "Whale Watching". In Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J.G.M. 'Hans' (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. p. 1224. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- "Whale Watching in Hawai'i". Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- "Humpbacks Make a Splash in the N. Pacific". Wildwhales.org. 2008-05-23. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "NOAA SARS Humpback whales, North Atlantic" (PDF). Nmfs.noaa.gov. 2008-04-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-02-21. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Humpback whale abundance south of 60°S from three complete circumpolar sets of surveys" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Fisheries, NOAA (2019-02-25). "Humpback Whale | NOAA Fisheries". www.fisheries.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- "Humpback whale on road to recovery, reveals IUCN Red List". IUCN. 2008-08-12. Archived from the original on 2011-11-21. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- Hotz, Robert Lee (November 6, 2009). "Whale Watch: Endangered Designation In Danger". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- Henderson, Carrol L. (2010). Mammals, Amphibians, and Reptiles of Costa Rica. University of Texas Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780292784642.

- "Study: Humpback whale population is rising". 2008-05-23. Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- "US National Marine Fisheries Service humpback whale web page". Nmfs.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-01-03. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- "Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)". Division of Wildlife Conservation, Alaska Department of Fish and Game. 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ^ "SPLASH: Structure of Populations, Levels of Abundance and Status of Humpback Whales in the North Pacific" (PDF), Cascadia Research, Final report for Contract commissioned by U.S. Department of Commerce, May 2008, archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2014, retrieved 22 April 2014

- Calambokidis, John; et al. (1997), Abundance and population structure of humpback whales in the North Pacific basin. Final Contract Report 50ABNF500113 to Southwest Fisheries Science Center, La Jolla, CA, p. 72

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)". National Parks Conservation Association. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ Chung, Emily (April 22, 2014), Humpback whale losing 'threatened' status amid Northern Gateway concerns, CBC, archived from the original on April 23, 2014, retrieved April 23, 2014

- Order Amending Schedule 1 to the Species at Risk Act, vol. 148, Canada: The Gazette, April 19, 2014, archived from the original on April 24, 2014, retrieved April 23, 2014

- Childerhouse, S.; Jackson, J.; Baker, C.S.; Gales, N.; Clapham, P.J.; Brownell, R.L. Jr. (2008). "Megaptera novaeangliae (Oceania subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T132832A3463914. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Ketten, D. R.; Lien, J.; Todd, J. (1993). "Blast injury in humpback whale ears: Evidence and implications". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 94 (3): 1849–50. Bibcode:1993ASAJ...94.1849K. doi:10.1121/1.407688.

- "Whales are dying along East Coast—and scientists are racing to understand why". Animals. 2019-03-13. Archived from the original on 2019-03-23. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- Dierauf, Leslie; Gulland, Frances M.D. (27 June 2001). CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine: Health, Disease and Rehabilitation (Second ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-4163-7.

- Werth, A. J.; Blakeney, S. M.; Cothren, A. I. (2019). "Oil adsorption does not structurally or functionally alter whale baleen". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (5): 182194. Bibcode:2019RSOS....682194W. doi:10.1098/rsos.182194. PMC 6549998. PMID 31218043.

- "Professor Struthers and the Tay Whale". Archived from the original on 2005-11-11. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- Williams, M. J. (1996). "Professor Struthers and the Tay whale". Scottish Medical Journal. 41 (3): 92–94. doi:10.1177/003693309604100308. PMID 8807706.

- Pennington, C. The modernisation of medical teaching at Aberdeen in the nineteenth century. Aberdeen University Press, 1994.

- Struthers 1889.

- "Exclusion zone for special whale". BBC News. 2009-06-30. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- Polanowski, A. M.; Robinson-Laverick, S. M.; Paton, D.; Jarman, S. N. (2011). "Variation in the Tyrosinase Gene Associated with a White Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)". Journal of Heredity. 103 (1): 130–133. doi:10.1093/jhered/esr108. PMID 22140253.

- "Share the Water" (PDF). Department of Environment and Science. Queensland Government. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Migaloo spotted in Hawaii!". SUP, Canoe, Kayak Tours & Maui Surf Lessons. Retrieved 2021-10-21.

- Jane Kay, San Francisco Examiner Monday, 9 October 1995

- Tokuda, Wendy; Hall, Richard (14 October 2014). Humphrey the Lost Whale: A True Story. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-61172-017-4.

- Knapp, Toni (1 October 1993). The Six Bridges of Humphrey the Whale. Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN 978-1-879373-64-8.

Sources

Books

- Clapham, Phil (1996). Humpback Whales. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-89658-296-5.

- Clapham, Phil (2002). "Humpback Whale". Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-551340-1.

- Dawbin, William H. (1966). The Seasonal Migratory Cycle of Humpback Whales. University of California Press.

- Dawes, John; Campbell, Andrew (2008). Exploring the World of Aquatic Life. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-255-7.

- Evans, Peter G.H.; Raga, Juan Antonio (6 December 2012). Marine Mammals: Biology and Conservation. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4615-0529-7.

- Reeves, Randall R.; Stewart, Brent S.; Clapham, Phillip J.; Powell, James A. (2002). National Audubon Society guide to marine mammals of the world. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Struthers, Sir John (1889). Memoir on the Anatomy of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera Longimana. Maclachlan and Stewart.

Journal articles

- Best, P. B. (1993). "Increase rates in severely depleted stocks of baleen whales". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 50 (2): 169–186. doi:10.1006/jmsc.1993.1018.

- Smith, T.D.; Allen, J.; Clapham, P.J.; Hammond, P.S.; Katona, S.; Larsen, F.; Lien, J.; Mattila, D.; Palsboll, P.J.; Sigurjonsson, J.; Stevick, P. T.; Oien, N. (1999). "An ocean-basin-wide mark-recapture study of the North Atlantic humpback whale". Marine Mammal Science. 15: 1–32. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00779.x. Archived from the original on 2021-06-23. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- Franklin, T.; Franklin, W.; Brooks, L.; Harrison, P.; Baverstock, P.; Clapham, P. (2011). "Seasonal changes in pod characteristics of eastern Australian humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), Hervey Bay 1992–2005". Marine Mammal Science. 27 (3): E134 – E152. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00430.x.

External links

Listen to this article (22 minutes)- General

- US National Marine Fisheries Service Humpback Whale web page

- ARKive – images and movies of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae).

- Humpbacks of Hervey Bay, Queensland, Australia

- The Dolphin Institute Whale Resource Guide and scientific publications

- Humpback Whale Gallery (Silverbanks)

- (in French) Humpback whale videos

- The Humpback Whales of Hervey Bay

- Epic humpback whale battle filmed

- Humpback whale songs

- The Whalesong Project

- Article from PHYSORG.com on the complex syntax of whalesong phrases

- Voices of the Sea – Sounds of the Humpback Whale Archived 2014-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Songlines – Songs of the Eastern Australian Humpback whales

- Conservation

- Videos

- Humpback whales' attempt to stop killer whale attack – Planet Earth Live – BBC One

- Humpback whales defend Gray whale against Killer whales (YouTube)

- Humpbacks Block Orcas’ Feeding Frenzy (LiveScience)

- Humpback whales charge group of transient orcas (Save Our Seas Foundation)

- Humpbacks Chase Killer Whales Right Under Our Boat, 8/24/2014

- Humpback Whale Mother Fights Off Males to Protect Calf | BBC Earth

- Whale Protects Diver From Shark | The Dodo

- Other

- Dead calf at the Amazon rainforest

| Genera of baleen whales and their extinct allies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Megaptera novaeangliae |

|

| Balaena novaeangliae | |

Categories: