| Revision as of 02:52, 5 March 2007 editSylent (talk | contribs)1,903 editsm Reverted 3 edits by 203.12.147.98 identified as vandalism to last revision by Angusmclellan. using TW← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:08, 5 March 2007 edit undo203.12.147.98 (talk) →Text and scriptNext edit → | ||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

| ===Text and script=== | ===Text and script=== | ||

| Joey | |||

| The Book of Kells contains the text of the four gospels based on the Vulgate. It does not, however, contain a pure copy of the Vulgate. There are numerous variants from the Vulgate, where Old Latin translations are used rather than Jerome's text. Although these variants are common in all of the insular gospels, there does not seem to be a consistent pattern of variation amongst the various insular texts. It is thought that when the scribes were writing the text they often depended on memory rather than on their exemplar. | |||

| Rules !!!'''Bold text''' | |||

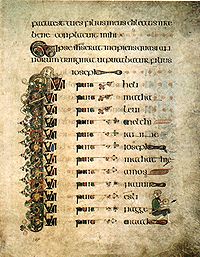

| ] written in Insular majuscule by the scribe known as "Hand B".]] | ] written in Insular majuscule by the scribe known as "Hand B".]] | ||

Revision as of 03:08, 5 March 2007

The Book of Kells (Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS 58, less widely known as the Book of Columba) is an ornately illustrated manuscript, produced by Celtic monks around AD 800 in the style known as Insular art. It is one of the more lavishly illuminated manuscripts to survive from the Middle Ages and has been described as the zenith of Western calligraphy and illumination. It contains the four gospels of the Bible in Latin, along with prefatory and explanatory matter decorated with numerous colourful illustrations and illuminations. Today it is on permanent display at the Trinity College Library in Dublin, Ireland.

History

Origin

The Book of Kells is the high point of a group of manuscripts in what is known as the Insular style produced from the late 6th through the early 9th centuries in monasteries in Ireland, Scotland and northern England and in continental monasteries with Irish or English foundations. These manuscripts include the Cathach of St. Columba, the Ambrosiana Orosius, a fragmentary gospel in the Durham cathedral library (all from the early 7th century), and the Book of Durrow (from the second half of the 7th century). From the early 8th century come the Durham Gospels, the Echternach Gospels, the Lindisfarne Gospels (see illustration at right), and the Lichfield Gospels. The St. Gall Gospel Book and the Macregal Gospels come from the late 8th century. The Book of Armagh (dated to 807-809), the Turin Gospel Book Fragment, the Leiden Priscian, the St. Gall Priscian and the Macdurnan Gospel all date from the early 9th century. Scholars place these manuscripts together based on similarities in artistic style, script, and textual traditions. The fully developed style of the ornamentation of the Book of Kells places it late in this series, either from the late eighth or early ninth century. The Book of Kells follows many of the iconographic and stylistic traditions found in these earlier manuscripts. For example, the form of the decorated letters found in the incipit pages for the Gospels is surprisingly consistent in Insular Gospels. Compare, for example, the incipit pages of the Gospel of Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels and in the Book of Kells both of which feature intricate decorative knotwork inside the outlines formed by the enlarged initial letters of the text. (For a more complete list of related manuscripts see: List of Hiberno-Saxon illustrated manuscripts.)

The name "Book of Kells" is derived from the Abbey of Kells in Kells, County Meath in Ireland, where it was kept for much of the medieval period. The Abbey of Kells dates back to the sixth century, at the time of the Viking invasions, and was founded by monks from the monastery at Iona (off the Western coast of Scotland). Iona, which had been a missionary centre for the Columban community, had been founded by St. Columba in the middle of the 6th century. When repeated Viking raids made Iona too dangerous, the majority of the community removed to Kells, which became the centre of the group of communities founded by St. Columba.

The date and place of production of the manuscript has been the subject of considerable debate. Traditionally, the book was thought to have been created in the time of Saint Columba (also known as St. Columcille), possibly even as the work of his own hands. However, it is now generally accepted that this tradition is false based on palaeographic grounds: the style of script in which the book is written did not develop until well after Columba's death, making it impossible for him to have written it.

The manuscript was never finished. There are at least five competing theories about the manuscript's place of origin and time of completion. First, the book may have been created entirely at Iona, then brought to Kells and never finished. Second, the book may have been begun at Iona and continued at Kells, but never finished. Third, the manuscript may have been produced entirely in the scriptorium at Kells. Fourth, it may have been produced in the north of England, perhaps at Lindisfarne, then brought to Iona and from there to Kells. Finally, it may have been the product of an unknown monastery in Scotland. Although the question of the exact location of the book's production will probably never be answered conclusively, the second theory, that it was begun at Iona and finished at Kells, is currently the most widely accepted. Regardless of which theory is true, it is certain that the Book of Kells was produced by Columban monks closely associated with the community at Iona.

Medieval period

Wherever it was made, the book soon came to its namesake city of Kells. It probably arrived in the early 11th century, and was definitely there by the twelfth.

The evidence for an eleventh century arrival consists of an entry in the Annals of Ulster for 1006. This entry records that "the great Gospel of Columkille, the chief relic of the Western World, was wickedly stolen during the night from the western sacristy of the great stone church at Cenannas on account of its wrought shrine". Cenannas was the medieval Irish name for Kells. The manuscript was recovered a few months later - minus its golden and bejewelled cover - "under a sod". It is generally assumed that the "great Gospel of Columkille" is the Book of Kells. If this is correct, then the book had arrived in Kells by 1006, and been there long enough for thieves to learn of its presence. The force of ripping the manuscript free from its cover may account for the folios missing from the beginning and end of the Book of Kells.

Regardless, the book was certainly at Kells in the 12th century, when land charters pertaining to the Abbey of Kells were copied into some of the book's blank pages. The copying of charters into important books such as the Book of Kells was a wide-spread mediaeval practice, which gives us indisputable evidence about the location of the book at the time the charters were written into it.

The 12th century writer, Gerald of Wales, in his Topographia Hibernica, described, in a famous passage, seeing a great Gospel Book in Kildare which many have since assumed was the Book of Kells. The description certainly matches Kells:

- "This book contains the harmony of the four Evangelists according to Jerome, where for almost every page there are different designs, distinguished by varied colours. Here you may see the face of majesty, divinely drawn, here the mystic symbols of the Evangelists, each with wings, now six, now four, now two; here the eagle, there the calf, here the man and there the lion, and other forms almost infinite. Look at them superficially with the ordinary glance, and you would think it is an erasure, and not tracery. Fine craftsmanship is all about you, but you might not notice it. Look more keenly at it and you will penetrate to the very shrine of art. You will make out intricacies, so delicate and so subtle, so full of knots and links, with colours so fresh and vivid, that you might say that all this was the work of an angel, and not of a man."

Since Gerald claims to have seen his book in Kildare, he may have seen another, now lost, book equal in quality to the Book of Kells, or he may have misstated his location when seeing Kells, intentionally or otherwise.

The Abbey of Kells was dissolved due to the ecclesiastical reforms of the 12th century. The abbey church was converted to a parish church in which the Book of Kells remained.

Modern period

The Book of Kells remained in Kells until 1654. In that year Cromwell's cavalry was quartered in the church at Kells and the governor of the town sent the book to Dublin for safe keeping. The book was presented to Trinity College in Dublin in 1661 by Henry Jones, who was to become bishop of Meath after the Restoration. The book has remained at Trinity College since the 17th century, except for brief loans to other libraries and museums. It has been displayed to the public in the Old Library at Trinity since the 19th century.

In the 16th century, the chapter numbers of the Gospels according to the division created by the 13th century Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton were written in the margins of the pages in roman numerals by Gerald Plunkett of Dublin. In 1621 the folios were numbered by the bishop-elect of Meath, James Ussher. In 1849 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were invited to sign the book. They in fact signed a modern flyleaf which was erroneously believed to have been one of the original folios. The page which they signed was removed when the book was rebound in 1953.

Over the centuries the book has been rebound several times. During an 18th century rebinding, the pages were rather unsympathetically cropped, with small parts of some illustrations being lost. The book was also rebound in 1895, but that rebinding broke down quickly. By the late 1920s several folios were being kept loose under a separate cover. In 1953, the work was bound in four volumes by Roger Powell, who also gently stretched several of the pages, which had developed bulges.

In 2000, the volume containing the Gospel of Mark was sent to Canberra, Australia for an exhibition of illuminated manuscripts. This was only the fourth time the Book of Kells had been sent abroad for exhibition. Unfortunately, the volume suffered what has been called "minor pigment damage" while en route to Canberra. It is thought that the vibrations from the aeroplane's engines during the long flight may have caused the damage.

Reproductions

In 1951, the Swiss publisher, Urs Graf-verlag Bern, produced a facsimile. The majority of the pages were reproduced in black and white photographs. There were, however, forty-eight pages reproduced in colour, including all of the full page decorations.

In 1979, another Swiss publisher, Faksimile verlag Luzern, requested permission to produce a full colour facsimile of the book. Permission was initially denied because Trinity College officials felt that the risk of damage to the book was too high. In 1986, after developing a process which used gentle suction to straighten a page so that it could be photographed without touching it, the publisher was given permission to produce a facsimile edition. After each page was photographed, a single page facsimile was prepared and the colours were carefully compared to the original and adjustments were made where necessary. The facsimile was published in 1990 in two volumes, the facsimile and a volume of commentary by prominent scholars. One copy is held by the Anglican Church in Kells, on the site of the original monastery. A DVD version containing scanned versions of all pages along with additional information is also available.

Description

The Book of Kells contains the four gospels of the Christian scriptures written in black, red, purple, and yellow ink in an insular majuscule script, preceded by prefaces, summaries, and concordances of gospel passages. Today it consists of 340 vellum leaves, called folios. The majority of the folios are part of larger sheets, called bifolios, which are folded in half to form two folios. The bifolios are nested inside of each other and sewn together to form gatherings called quires. On occasion, a folio is not part of a bifolio, but is instead a single sheet inserted within a quire.

It is believed that some 30 folios have been lost. (When the book was examined by Ussher in 1621 there were 344 folios.) The extant folios are gathered into 38 quires. There are between four and twelve folios per quire (two to six bifolios). Ten folios per quire is common. Some folios are single sheets. The important decorated pages often occurred on single sheets. The folios had lines drawn for the text, sometimes on both sides, after the bifolia were folded. Prick marks and guide lines can still be seen on some pages. The vellum is of high quality, although the folios have an uneven thickness, with some being almost leather, while others are so thin as to be almost translucent. The book's current dimensions are 330 by 250 mm. Originally the folios were not of standard size, but they were cropped to the current standard size during an 18th century rebinding. The text area is approximately 250 by 170 mm. Each text page has 16 to 18 lines of text. The manuscript is in remarkably good condition. The book was apparently left unfinished, as some of the artwork appears only in outline.

Contents

The book, as it exists now, contains preliminary matter, the complete text of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, and the Gospel of John through John 17:13. The remainder of John and an unknown amount of the preliminary matter is missing and was perhaps lost when the book was stolen in the early 11th century. The extant preliminary matter consists of two fragments of lists of Hebrew names contained in the gospels, the Breves causae and the Argumenta of the four gospels, and the Eusebian canon tables. It is probable that, like the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Books of Durrow and Armagh, part of the lost preliminary material included the letter of Jerome to Pope Damasus I known as Novum opus, in which Jerome explains the purpose of his translation. It is also possible, though less likely, that the lost material included the letter of Eusebius, known as Plures fuisse, in which he explains the use of the canon tables. (Of all the insular gospels, only Lindisfarne contains this letter.)

There are two fragments of the lists of Hebrew names; one on the recto of the first surviving folio and one on folio 26, which is currently inserted at the end of the prefatory matter for John. The first list fragment contains the end of the list for the Gospel of Matthew. The missing names from Matthew would require an additional two folios. The second list fragment, on folio 26, contains about a fourth of the list for Luke. The list for Luke would require an additional three folios. The structure of the quire in which folio 26 occurs is such that it is unlikely that there are three folios missing between folios 26 and 27, so that it is almost certain that folio 26 is not now in its original location. There is no trace of the lists for Mark and John.

The first list fragment is followed by the canon tables of Eusebius of Caesarea. These tables, which predate the text of the Vulgate, were developed to cross reference the gospels. Eusebius divided the Gospel into chapters and then created tables which allowed readers to find where a given episode in the life of Christ was located in each of the Gospels. The canon tables were traditionally included in the prefatory material in most mediaeval copies of the Vulgate text of the Gospels. The tables in the Book of Kells, however, are almost unusable because the scribe condensed the tables into in such a way as to make them confused. In addition, the corresponding chapter numbers were never inserted into the margins of the text, making it impossible to find the sections to which the canon tables refer. The reason these chapter numbers were never inserted is uncertain. It may have been planned to insert them when the decoration was completed, but since the decoration was never completed, they were never inserted. It also may be that it was decided to leave them out so as not to mar the appearance of pages.

The Breves causae and the Argumenta belong to a pre-Vulgate tradition of manuscripts. The Breves causae are summaries of the Old Latin translations of the Gospels. They are divided into numbered chapters. These chapter numbers, like the numbers for the canon tables, are also not used on the text pages of the gospels. However, it is unlikely that these numbers would have been used, even if the manuscript had been completed, because the chapter numbers corresponded to old Latin translations and would have been difficult to harmonise with the Vulgate text. The Argumenta are collections of legends about the Evangelists. The Breves causae and Argumenta are arranged in a strange order: first come the Breves causae and Argumenta for Matthew, followed by the Breves and Argumenta for Mark, then, quite oddly, come the Argumenta of Luke and John, followed by the Breves causae of Luke and John. This anomalous order is the same as is found in the Book of Durrow, although the out of place Breves causae of Luke and John are placed at the end of the manuscript in Durrow, while the rest of the preliminaries are at the beginning. In other insular manuscripts, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Book of Armagh, and the Echternach Gospels, each Gospel is treated as separate work and has its preliminaries immediately preceding it. The slavish repetition in Kells of the order of the Breves causae and Argumenta found in Durrow led the scholar T. K. Abbot to the conclusion that the scribe of Kells had either the Book of Durrow, or a common model in hand.

Text and script

Joey Rules !!!Bold text

The manuscript is written in Insular majuscule, with some minuscule letters usually "c" and "s". The text is usually written in one long line across the page. Francoise Henry identified at least three scribes in this manuscript, whom she named Hand A, Hand B, and Hand C. Hand A is found on folios 1 through 19v, folios 276 through 289 and folios 307 through the end of the manuscript. Hand A for the most part writes eighteen or nineteen lines per page in the brown gall-ink common throughout the west. Hand B is found on folios 19r through 26 and folios 124 through 128. Hand B has a somewhat greater tendency to use minuscule and uses red, purple and black ink and a variable number of lines per page. Hand C is found throughout the majority of the text. Hand C also has greater tendency to use minuscule than Hand A. Hand C uses the same brownish gall-ink used by hand A, and wrote, almost always, seventeen lines per page.

Errors

There are a number of differences between the text and the accepted gospels.

- In the genealogy of Jesus, which starts at Luke 3:23, Kells erroneously names an extra ancestor.

- Matthew 10:34b should read “I came not to send peace, but the sword”. However rather than “gladium” which means “sword”, Kells has “gaudium” meaning “joy”. Rendering the verse in translation: “I came not to send peace, but joy”.

Decoration

The text is accompanied by incredibly intricate full pages of artwork, with smaller painted decorations appearing throughout the text itself. The book has a broad palette of colours with purple, lilac, red, pink, green, yellow being the colours most often used. (The illustrations in the Book of Durrow, by contrast, use only four colours.) Surprisingly, given the lavish nature of the work, there was no use of gold or silver leaf in the manuscript. The pigments used for the illustrations had to be imported from all over Europe.

The lavish illumination programme is far greater than any other surviving insular gospel book. There are ten surviving full page illuminations including two evangelist portraits, three pages with the four evangelist symbols, a carpet page, a miniature of the Virgin and Child, a miniature of Christ enthroned, and miniatures of the Arrest of Jesus and the Temptation of Christ. There are 13 surviving full pages of decorated text including pages for the first few words of each of the gospels. There are many pages where only some of the text on the page is decorated. Eight of the ten pages of the canon tables have extensive decoration. It is highly probable that there were other pages of miniature and decorated text that are now lost. In addition to these major pages there are a host of smaller decorations and decorated initials scattered throughout the text.

The extant folios of the manuscript start with the fragment of the glossary of Hebrew names. This fragment occupies one column of folio 1 recto. The other column of the folio is occupied by a miniature of the four evangelist symbols, now much abraded. The miniature is oriented so that the volume must be turned ninety degrees in order to view it properly. The four evangelist symbols are a visual theme that runs throughout the book. They are almost always shown together so that the doctrine of unity of message of the four Gospels is emphasised.

The unity of the Gospels is further emphasised by the decoration of the Eusebian canon tables. The canon tables themselves are designed to establish the unity of the Gospels by allowing readers to find corresponding passages from the gospels. The Eusebian canon tables normally requires twelve pages. In the Book of Kells the makers of the manuscript planned for twelve pages (folios 1v through 7r), but for unknown reasons condensed them into ten pages, leaving folios 6v and 7r blank. This condensation caused the canon tables to be unusable. The decoration of the first eight pages of the canon tables is heavily influenced by early Gospel Books from the Mediterranean. It was traditional to enclose the tables in an arcade. (See, for example the London Canon Tables). Kells does this, but with an Insular spirit. The arcades are not seen as architectural elements, but are rather stylised into geometric patterns which are then decorated with Insular motifs. The four evangelist symbols occupy the spaces under and above the arches. The last two canon tables are presented within a grid. This presentation is limited to Insular manuscripts and was first seen in the Book of Durrow.

The remainder of the book after the canon tables is broken into sections with the beginning of each section being marked by miniatures and full pages of decorated text. Each of the Gospels is introduced by a consistent decorative programme. The preliminary matter is treated as one section and introduced by a lavish decorative spread. In addition to the preliminaries and the Gospels, the "second beginning" of the Gospel of Matthew is also given its own introductory decoration.

The preliminary matter is introduced by an iconic image of the Virgin and Child (folio 7v). This miniature is the first representation of the Virgin in a western manuscript. Mary is shown in an odd mixture of frontal and three-quarter pose. This miniature also bears a stylistic similarity to the carvings on the lid of St. Cuthbert's coffin. The iconography of the miniature may ultimately derive from an Eastern or Coptic icon.

The miniature of the Virgin and Child faces the first page of text and is an appropriate preface to the beginning of the Breves Causae of Matthew, which begins Nativitas Christi in Bethlem (the birth of Christ in Bethlehem). The beginning page (folio 8r) of the text of the Breves Causae is decorated and contained within an elaborate frame. The two page spread of the miniature and the text make a vivid introductory statement for the prefatory material. The opening line of each of the sections of the preliminary matter is enlarged and decorated (see above for the Breves causae of Luke), but no other section of the preliminaries is given the same level of treatment as the beginning of the Breves Causae of Matthew.

The book was designed so that each of the Gospels would have an elaborate introductory decorative programme. Each Gospel was originally prefaced by a full page miniature containing the four evangelist symbols, followed by a blank page. Then came a portrait of the evangelist which faced the opening text of the gospel which was given an elaborate decorative treatment. The Gospel of Matthew retains both its Evangelist portrait (folio 28v) and its page of Evangelist symbols (folio 27r, see above). The Gospel of Mark is missing the Evangelist portrait, but retains its Evangelist symbols page (folio 129v). The Gospel of Luke is missing both the portrait and the Evangelist symbols page. The Gospel of John, like the Matthew retains both its portrait (folio 291v, see at right) and its Evangelist symbols page (folio 290v). It can be assumed that the portraits for Mark and Luke, and the symbols page for Luke at one time existed, but have been lost. The use of all four of the Evangelist symbols in front of each Gospel is striking and was intended to reinforce the message of the unity of the Gospels.

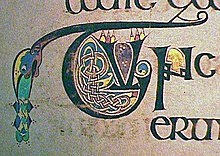

The decoration of the opening few words of each Gospel was lavish. These pages were, in effect turned into carpet pages. The decoration of these texts is so elaborate that the text itself is almost illegible. The opening page (folio 28r) of Matthew may stand as an example. (See illustration at left.) The page consists of only two words Liber generationis ("The book of the generation"). The "lib" of Liber is turned in to a giant monogram which dominates the entire page. The "er" of Liber is presented as interlaced ornament within the "b" of the "lib" monogram. Generationis is broken into three lines and contained within an elaborate frame in the right lower quadrant of the page. The entire assemblage is contained within an elaborate border. The border and the letters themselves are further decorated with elaborate spirals and knot work, many of them zoomorphic. The opening words of Mark, Initium evangelii ("The beginning of the gospel"), Luke, Quoniam quidem multi, and John In principio erat verbum ("In the beginning was the Word") are all given similar treatments. Although the decoration of these pages was most extensive in the Book of Kells, these pages were decorated in all of the other Insular Gospel Books.

The Gospel of Matthew begins with a genealogy of Jesus. At Matthew 1:18, the actual narrative of Christ's life starts. This "second beginning" to Matthew was given emphasis in many early Gospel Books, so much so that the two sections were often treated as separate works. The "second beginning" begins with the word "Christ". The Greek letters "Chi" and "Rho" were often used in mediaeval manuscripts to abbreviate the word "Christ". In Insular Gospel Books the initial "Chi Rho monogram" was enlarged and decorated. In the Book of Kells, this second beginning was given a decorative programme equal to the those that preface the individual Gospels. Folio 32 verso has a miniature of Christ enthroned. (It has been argued that this miniature is one of the lost evangelist portraits. However the iconography is quite different from the extant portraits, and current scholarship accepts this identification and placement for this miniature.) Facing this miniature, on folio 33 recto, is the only Carpet Page in the Kells. (The single Carpet Page in Kells is a bit anomalous. The Lindisfarne Gospels has five extant Carpet Pages and the Book of Durrow has six.) The blank verso of folio 33 faces the single most lavish miniature of the early mediaeval period, the Book of Kells Chi Rho monogram, which serves as incipit for the narrative of the life of Christ.

In the Book of Kells, the Chi Rho monogram has grown to consume the entire page. The letter "Chi" dominates the page with one arm swooping across the majority of the page. The letter "Rho" is snuggled underneath the arms of the Chi. Both letters are divided into compartment which are lavishly decorated with knot work and other patterns. The background is likewise awash in mass of swirling and knotted decoration. Within this mass of decoration are hidden animals and insects. Three angels arise from one of the cross arms of the Chi. This miniature is the largest and most lavish extant Chi Rho monogram in any Insular Gospel Books and is the culmination of a tradition that started with the Book of Durrow.

The Book of Kells contains two other Full page miniatures which illustrate episodes from the Passion story. The text of Matthew is illustrated with full page illumination of the Arrest of Christ (folio 114r). Jesus is shown beneath a stylised arcade while being held by two much smaller figures. In the text of Luke there is a full sized miniature of the Temptation of Christ (folio 202v). Christ is shown from the waist up on top of the Temple. To his a right is a crowd of people, perhaps representing his disciples. To his left and below him is a black figure of Satan. Above him hover two angels.

The verso of the folio containing the Arrest of Christ contains a full page of decorated text which begins "Tunc dicit illis". Facing the miniature of the Temptation is another full page of decorated text (folio 203r "Iesus autem plenus"). In addition to this page five other full pages also receive elaborate treatment. In Matthew there is one other full page treatment of (folio 124r, "Tunc crucifixerant Xpi cum eo duos latrones"). In the Gospel of Mark, there are also two pages of decorated text (folio 183r, "Erat autem hora tercia", and folio 187v " quidem postquam"). The Gospel of Luke contains two pages of fully decorated text. (folio 188v "Fuit in diebus Herodis ", and folio 285r "Una autem sabbati valde"). Although these texts do not have miniatures associated with them it is probable that miniatures were planned to accompany each of these texts and have either been lost, or were never completed. There is no surviving full page of text in the Gospel of John other than the Incipit. However, in the other three Gospels all of the full pages of decorated text, except for folio 188c which begins the Nativity narration, occur within the Passion narrative. However, since the missing folios of John contain the Passion narrative, it is likely that John contained full pages of decorated text that have been lost.

The decoration of the book is not limited to the major pages. Indeed all but two pages have at least some decoration. Scattered through the text are decorated initials and small figures of animals and humans often twisted and tied into complicated knots. Many significant texts, such as the Pater Noster have decorated initials. The page containing text of the Beatitudes in Matthew (folio 40v) has a large miniature along the left margin of the page in which the letter "B" which begins each line is linked into an ornate chain. The genealogy of Christ found in the Gospel of Luke (folio 200r) contains a similar miniature in which the word "qui" is repeatedly linked along the left margin. Many of the small animals scattered throughout the text serve to mark a "turn-in-the-path" (that is, a place where a line is finished in a space above or below the original line). Many other animals serve to fill spaces left at the end of lines. No two of these designs are the same. No earlier surviving manuscript has this massive amount of decoration.

The decorations are all of high quality. The complexity of these designs is often breath-taking. In one decoration, which occupies one inch square piece of a page, it is possible to count as many as 158 complex interlacements of white ribbon with a black border on either side. Some decorations can only be fully appreciated with magnifying glasses, although glasses of the required power were not available until hundreds of years after the book's completion. The complicated knot work and interweaving found in Kells and related manuscripts have many parallels in the metalwork and stone carving of the period. These design have also had an enduring popularity. Indeed many of these motifs are used today in popular art including jewellery and tattoos.

Use

The book had a sacramental, rather than educational purpose. A large, lavish Gospel, such as the Book of Kells would have been left on the high altar of the church, and taken off only for the reading of the Gospel during Mass. However, it is probable that the reader would not actually read the text from the book, but rather recite from memory. It is significant that the Chronicles of Ulster state that the book was stolen from the sacristy (where the vessels and other accruements of the mass were stored) rather than from the monastic library. The design of the book seems to take this purpose in mind, that is the book was produced to look good rather than be useful. There are numerous uncorrected mistakes in the text. Lines were often completed in a blank space in the line above. The chapter headings that were necessary to make the canon tables usable were not inserted into the margins of the page. In general, nothing was done to disrupt the aesthetic look of the page: aesthetics were given a priority over utility.

References

- Alexander, J. G. G. Insular Manuscripts: Sixth to Ninth Century. London: Harvey Miller, 1978.

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Henderson, George. From Durrow to Kells : the Insular Gospel-books, 650-800. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1987.

- Henry, Francoise. The Book of Kells. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1974.

Further reading

A very large body of published works on the Books of Kells exist. This list includes only a very small part. Bibliographical tools such as the RHS Bibliography can provide exhaustive listings.

- Alton, E. H. and P. Meyer Enageliorum quattor Codex Cenannensi. 3 vols. Bern: Urs Graf Verlag, 1959-1951.

- Brown, T. J. "Northumbria and the Book of Kells". Anglo-Saxon England I (1972): 219-246.

- De Paor, Liam, "The world of the Book of Kells" in Ireland and early Europe : essays and occasional writings on art and culture. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1997. ISBN 1-85182-298-4

- Farr, Carol Ann, The book of Kells : its function and audience (British Library Studies in Medieval Culture, 4). London: British Library & Toronto:University of Toronto Press, 1997. ISBN 0-7123-0499-1.

- Friend, A. M., Jr. "The Canon Tables of the Book of Kells". In Mediæval Studies in Memory of A. Kingsley Porter, ed. W. R. K. Koehler. Vol. 2, pp. 611-641. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1939.

- Lewis, Susanne. "Sacred Calligraphy: The Chi Rho Page in the Book of Kells" Traditio 36 (1980): 139-159.

- McGurk, P. "Two Notes on the Book of Kells and Its Relation to Other Insular Gospel Books" Scriptorium 9 (1955): 105-107.

- Meehan, Bernard. The Book of Kells: An Illustrated Introduction to the Manuscript in Trinity College Dublin'. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994

- Mussetter, Sally . "An Animal Miniature on the Monogram Page of the Book of Kells" Mediaevalia 3 (1977): 119-120.

- Nordenfalk, Carl "Another Look at the Book of Kells" In Festschrift Wolgang Braunfels, pp. 275-279. Tubingen: Wasmuth, 1977.

- Nordenfalk, Carl, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book Illumination in the British Isles 600-800. New York: George Braziller, 1977.

- Powell, Roger. "The Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, Comments on the Vellum and the Make-up and Other Aspects" Scriptorum 10 (1956), 12-21.

- Werner, Martin "The Madonna and Child Miniatures in the Book of Kells". Art Bulletin 54 (1972): 1-23, 129-139.

External links

- Book of Kells, Faksimile Verlag Luzern, Lucerne, 1990, ISBN 3-85672-031-6

- The Book of Kells DVD

- Scanned images, in the public domain

- More scanned images

- Article and pictures by Jerry B. Lincecum

- Book of Kells in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Ireland Funds and the Book of Kells

- Tattooing and the Book of Kells

- Real Audio interview with Urs Duggelin about the Book of Kells by Don Swaim

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FATemplate:Link FA

Categories: