| Revision as of 10:58, 13 April 2023 editPhytographer (talk | contribs)107 editsm →International bodies: Citation neededTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:10, 31 May 2023 edit undoSammielh (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,544 edits amending sourcesTag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| (47 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{short description|Norms in international relations}} | ||

| {{Redirect|Law of Nations|the 18th-century political treatise|The Law of Nations}} | {{Redirect|Law of Nations|the 18th-century political treatise|The Law of Nations}} | ||

| '''International law''' (also known as '''public international law''' and '''the law of nations''') is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognised as binding between ]. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for states across a broad range of domains, including ] and ], ], and ]. International law differs from state-based ] in that it is primarily, though not exclusively, applicable to states, rather than to individuals, and operates largely through consent, since there is no universally accepted authority to enforce it upon ]s. States may choose to not abide by international law, and even to breach a treaty but such violations, particularly of ]s, can be met with disapproval by others and in some cases coercive action ranging from diplomatic and ] to war. | |||

| {{politics}} | |||

| '''International law''' (also known as '''public international law''' and '''the law of nations''')<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/international-law|title=International law|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en|access-date=26 April 2019|archive-date=29 June 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190629162822/https://www.britannica.com/topic/international-law|url-status=live}}</ref> is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between ].<ref name="definition – international law">{{cite web|title=''international law''|url=http://www.thefreedictionary.com/international+law|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Company.|access-date=13 September 2011|archive-date=5 December 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111205053746/http://www.thefreedictionary.com/international+law|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>The term was first used by ] in his "Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation" in 1780. See {{Citation|last=Bentham|first=Jeremy|author-link=Jeremy Bentham|year=1789|title=An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation|publisher=T. Payne|publication-date=1789|location=London|pages=6|url=http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k93974k/f40.image.r=.langEN|access-date=5 December 2012|archive-date=11 December 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121211101825/http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k93974k/f40.image.r=.langEN|url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for states across a broad range of domains, including ], ], ], and ]. Scholars distinguish between international legal institutions on the basis of their obligations (the extent to which states are bound to the rules), precision (the extent to which the rules are unambiguous), and delegation (the extent to which third parties have authority to interpret, apply and make rules).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Abbott |first1=Kenneth W. |last2=Keohane |first2=Robert O. |last3=Moravcsik |first3=Andrew |last4=Slaughter |first4=Anne-Marie |last5=Snidal |first5=Duncan |date=2000 |title=The Concept of Legalization |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization/article/abs/concept-of-legalization/EF6AA703676B5053168AC43C27BF45A4 |journal=International Organization |language=en |volume=54 |issue=3 |pages=401–419 |doi=10.1162/002081800551271 |s2cid=16285815 |issn=1531-5088 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220818163728/https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization/article/abs/concept-of-legalization/EF6AA703676B5053168AC43C27BF45A4 |archive-date=2022-08-18 |access-date=2022-08-18 |url-status=bot: unknown }}</ref> | |||

| The ] |

With origins tracing back to ], states have a long history of negotiating interstate agreements. An initial framework was conceptualised by the Ancient Romans and this idea of '']'' has been used by various academics to establish the modern concept of international law. The ] include ] (general state practice accepted as law), ], and general principles of law recognised by most national legal systems. Although international law may also be reflected in ] — the practices adopted by states to maintain good relations and mutual recognition — such traditions are not legally binding. The ] between a ] and international law is complex and variable. National law may become international law when treaties permit national jurisdiction to ] tribunals such as the ] or the ]. Treaties such as the ] require national law to conform to treaty provisions. National laws or constitutions may also provide for the implementation or integration of international legal obligations into domestic law. | ||

| International law differs from state-based ]s in that it is primarily—though not exclusively—applicable to states, rather than to individuals, and operates largely through consent, since there is no universally accepted authority to enforce it upon ]. Consequently, states may choose to not abide by international law, and even to breach a treaty.<ref>{{cite book|title=Fundamental Perspectives on International Law|last=Slomanson|first=William|publisher=Wadsworth|year=2011|location=Boston, USA|pages=4}}</ref> However, such violations, particularly of customary international law and peremptory norms ('']''), can be met with disapproval by others and in some cases coercive action (ranging from diplomatic and ] to war). | |||

| The ] between a national legal system (]) and international law is complex and variable. National law may become international law when treaties permit national jurisdiction to ] tribunals such as the ] or the ]. Treaties such as the ] require national law to conform to treaty provisions. National laws or constitutions may also provide for the implementation or integration of international legal obligations into domestic law. | |||

| == Terminology == | == Terminology == | ||

| The modern term "international law" was originally coined by ] in his 1789 book ''Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation'' to replace the older law of nations, a direct translation of the late medieval concepts of '']'', used by ], and ''droits des gens'', used by ].{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=3}}{{Sfn|Janis|1984|p=408}} The definition of international law has been debated; Bentham referred specifically to relationships between states which has been criticised for its narrow scope.{{Sfn|Janis|1996|p=333}} ] defined it in his treatise as "a law between sovereign and equal states based on the common consent of these states" and this definition has been largely adopted by international legal scholars.{{Sfn|Ōnuma|2000|pp=3-4}} | |||

| The term "international law" is sometimes divided into "public" and "private" international law, particularly by civil law scholars or philosophers who seek to follow a Roman tradition.<ref>There is an ongoing debate on the relationship between different branches of international law. {{cite journal|last1=Koskenniemi|first1=Martti|date=September 2002|title=Fragmentation of International Law? Postmodern Anxieties|journal=Leiden Journal of International Law|volume=15|issue=3|pages=553–579|doi=10.1017/S0922156502000262|s2cid=146783448}} {{cite journal|last1=Yun|first1=Seira|date=2014| title=Breaking Imaginary Barriers: Obligations of Armed Non-State Actors Under General Human Rights Law – The Case of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child|journal=Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies|volume=5|issue=1–2|pages=213–257|ssrn=2556825|doi=10.1163/18781527-00501008|s2cid=153558830 }}</ref> Roman lawyers would have further distinguished '']'', the law of nations, and '']'', agreements between nations. On this view, "public" international law is said to cover relations between nation-states and includes fields such as ], ], ], the ] or ], ], and ]. By contrast "private" international law, which is more commonly termed "]", concerns whether courts within countries claim jurisdiction over cases with a foreign element, and which country's law applies.<ref>{{cite web|date=August 2009|title=Private International Law|url=http://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/private_international_law.asp|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210521074532/http://www.oas.org/en/sla/dil/private_international_law.asp|archive-date=21 May 2021|access-date=27 December 2017|website=Oas.org}}</ref> | |||

| There is a distinction between public and ]; the latter is concerned with whether national courts can claim jurisdiction over cases with a foreign element and the application of foreign judgments in domestic law, whereas public international law covers rules with an international origin.{{Sfn|Stevenson|1952|pp=561-562}} The difference between the two areas of law has been debated as scholars disagree about the nature of their relationship. ], who originated the term "private international law", emphasised that it must be governed by the principles of public international law but other academics view them as separate bodies of law.{{Sfn|Stevenson|1952|pp=564-567}}{{Sfn|Steinhardt|1991|p=523}} Another term, transnational law, is sometimes used to refer to a body of both national and international rules that transcend the nation state, although some academics emphasise that it is distinct from either type of law. It was defined by ] as "all law which regulates actions or events that transcend national frontiers".{{Sfn|Cotterrell|2012|p=501}} | |||

| When the modern system of (public) international law developed out of the tradition of the late medieval ''ius gentium,'' it was referred to as ''the law of nations,'' a direct translation of the concept ''ius gentium used'' by ] and ''droits des gens'' of ]. The modern term ''international law'' was invented by ] in 1789 and established itself in the 19th century.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Crawford|first=James|title=Brownlie's Principles of Public International Law|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2012|isbn=9780199699698| pages=3}}</ref> | |||

| A more recent concept is ], which was described in a 1969 paper as " relatively new word in the vocabulary of politics".{{Sfn|Head|1994|p=622}} Systems of supranational law arise when nations explicitly cede their right to make decisions to this system’s judiciary and legislature, which then have the right to make laws that are directly effective in each member state.{{Sfn|Head|1994|p=622}}{{Sfn|Degan|1997|p=126}} This has been described as "a level of international integration beyond mere intergovernmentalism yet still short of a federal system".{{Sfn|Head|1994|p=622}} The most common example of a supranational system is the ].{{Sfn|Degan|1997|p=126}} | |||

| A more recent concept is "]", which concerns regional agreements where the laws of nation states may be held inapplicable when conflicting with a supranational legal system to which the nation has a ] obligation.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/883/the-sovereignty-of-the-european-court-of-justice-and-the-eus-supranational-legal-system|title=The Sovereignty of the European Court of Justice and the EU's Supranational Legal System|author=Kolcak, Hakan|website=Inquiriesjournal.com|access-date=27 December 2017|archive-date=19 October 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019215816/http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/883/the-sovereignty-of-the-european-court-of-justice-and-the-eus-supranational-legal-system|url-status=live}}</ref> Systems of ] law arise when nations explicitly cede their right to make certain judicial decisions to a common tribunal.<ref name="Degan1997">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K0pTp1qCc9UC&pg=PA126|title=Sources of International Law|last=Degan|first=Vladimir Đuro|date=21 May 1997|publisher=Martinus Nijhoff Publishers|isbn=978-90-411-0421-2|page=126|access-date=5 December 2015|archive-date=27 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160427221053/https://books.google.com/books?id=K0pTp1qCc9UC&pg=PA126|url-status=live}}</ref> The decisions of the common tribunal are directly effective in each party nation, and have priority over decisions taken by national courts.<ref name="Blanpain2010">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ahaoKRbqPdMC&pg=PA410|title=Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations in Industrialized Market Economies|last=Blanpain|first=Roger|publisher=Kluwer Law International|year=2010|isbn=978-90-411-3348-9|pages=410 n.61|access-date=5 December 2015|archive-date=2 May 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160502133355/https://books.google.com/books?id=ahaoKRbqPdMC&pg=PA410|url-status=live}}</ref> The ] is the most prominent example of an international treaty organization that implements a supranational legal framework, with the ] having supremacy over all member-nation courts in matter of ]. | |||

| The term "transnational law" is sometimes used to a body of rules of ] that transcend the nation state.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cotterrell|first=Roger|date=1 March 2012|title=What Is Transnational Law?|journal=Law & Social Inquiry|language=en|volume=37|issue=2|pages=500–524|doi=10.1111/j.1747-4469.2012.01306.x|s2cid=146474315|issn=1747-4469|url=https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/68847|access-date=5 June 2021|archive-date=19 July 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210719060850/https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/68847|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| {{Main|History of international law}} | {{Main|History of international law}} | ||

| ], among the earliest extant examples of an international agreement.]] | ], among the earliest extant examples of an international agreement.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=1-2}}]] | ||

| The origins of international law can be traced back to ]. Among the earliest examples are ] between the ]n city-states of ] and ] (approximately |

The origins of international law can be traced back to ].{{Sfn|Bederman|2001|p=267}} Among the earliest recorded examples are ] between the ]n city-states of ] and ] (approximately 3100 BCE), and ] between the ], ], and the ], ], concluded in 1279 BCE.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=1-2}} Interstate pacts and agreements were negotiated and agreed by ] across the world, from the eastern ] to ].{{Sfn|Bederman|2001|pp=3-4}} In ], many ] were negotiated between its ] and, occasionally, with neighbouring states.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=5-6}} The ] established an early conceptual framework for international law, ''jus gentium'', which governed the status of foreigners living in Rome and relations between foreigners and ].{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=13-15}}{{Sfn|Bederman|2001|p=84}} Adopting the Greek concept of ], the Romans conceived of ''jus gentium'' as being universal.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=15-16}} However, in contrast to modern international law, the Roman law of nations applied to relations with and between foreign individuals rather than among political units such as states.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|p=14}} | ||

| ], which developed basic notions of governance and international relations, contributed to the formation of the international legal system; many of the ] on record were concluded among the ] or with neighboring states. The ] established an early conceptual framework for international law, ''jus gentium'' ("law of nations"), which governed both the status of foreigners living in Rome and relations between foreigners and ]. Adopting the Greek concept of ], the Romans conceived of ''jus gentium'' as being universal. However, in contrast to modern international law, the Roman law of nations applied to relations with and between foreign individuals rather than among political units such as states. | |||

| Beginning with the ] of the eighth century BCE, |

Beginning with the ] of the eighth century BCE, China was divided into numerous states that were often at war with each other. Rules for diplomacy and treaty-making emerged, including notions regarding ], the rights of neutral parties, and the consolidation and partition of states; these concepts were sometimes applied to relations with ]s along China's western periphery beyond the ].{{Sfn|Neff|2014|pp=17-18}}{{Sfn|deLisle|2000|pp=268-269}} The subsequent ] saw the development of two major schools of thought, ] and ], both of which held that the domestic and international legal spheres were closely interlinked, and sought to establish competing normative principles to guide foreign relations.{{Sfn|deLisle|2000|pp=268-269}}{{Sfn|Neff|2014|p=21}} Similarly, the ] was divided into various states, which over time developed rules of neutrality, ], and international conduct, and established both temporary and permanent ].{{Sfn|Alexander|1952|p=289}}{{Sfn|Patel|2016|pp=35-38}} | ||

| Following the ] in the fifth century CE, Europe fragmented into numerous often-warring states for much of the next five centuries. Political power was dispersed across a range of entities, including the ], ] city-states, and kingdoms, most of which had overlapping and ever-changing jurisdictions. As in China and India, these divisions prompted the development of rules aimed at providing stable and predictable relations. Early examples include ], which governed ] institutions and clergy throughout Europe; the '']'' |

Following the ] in the fifth century CE, Europe fragmented into numerous often-warring states for much of the next five centuries. Political power was dispersed across a range of entities, including the ], ] city-states, and kingdoms, most of which had overlapping and ever-changing jurisdictions. As in China and India, these divisions prompted the development of rules aimed at providing stable and predictable relations. Early examples include ], which governed ] institutions and clergy throughout Europe; the '']'' ("merchant law"), which concerned trade and commerce; and various codes of ], such as the ]—which drew from the Byzantine Rhodian Sea Law—and the ], enacted among the commercial ] of northern Europe and the ].{{Citation needed|date=April 2023}} | ||

| In the ], ] published ''Al-Siyar Al-Kabīr'' in the eighth century, which served as a fundamental reference work for '']'', a subset of ], which governed foreign relations.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2020|pp=315-316}}{{Sfn|Bashir|2018|p=5}} This was based on the division of the world into three categories: the ], where Islamic law prevailed; the ''dar al-sulh'', non-Islamic realms that concluded an armistice with a Muslim government; and the ''dar al-harb'', non-Islamic lands which were contested through '']''.{{Sfn|Khadduri|1956|p=359}}{{Sfn|Parvin|Sommer|1980|pp=3-4}} ] concerning ] served as precursors to modern ] and institutionalised limitations on military conduct, including guidelines for commencing war, distinguishing between civilians and combatants and caring for the sick and wounded.{{Sfn|Saeed|2018|p=299}}{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2020|p=322}} | |||

| Concurrently, in the ], foreign relations were guided based on the division of the world into three categories: The '']'' (territory of Islam), where Islamic law prevailed; ''dar al-sulh'' (territory of treaty), non-Islamic realms that have concluded an armistice with a Muslim government; and ''dar al-harb'' (territory of war), non-Islamic lands whose rulers are called upon to accept Islam''.''<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190902141015/http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e491 |date=2 September 2019 }} The Oxford Dictionary of Islam {{verify source |date=August 2019 |reason=This ref was deleted (]) by a bug in VisualEditor and later restored by a bot from the original cite at ] cite #3 - please verify the cite's accuracy and remove this {verify source} template. ]}}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191103010408/http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e496 |date=3 November 2019 }} The Oxford Dictionary of Islam {{verify source |date=August 2019 |reason=This ref was deleted (]) by a bug in VisualEditor and later restored by a bot from the original cite at ] cite #4 - please verify the cite's accuracy and remove this {verify source} template. ]}}</ref> Under the early ] of the seventh century C.E., ] concerning ] and the treatment of ] served as precursors to modern ]. Islamic law in this period institutionalised humanitarian limitations on military conduct, including attempts to limit the severity of war, guidelines for ceasing hostilities, distinguishing between civilians and combatants, preventing unnecessary destruction, and caring for the sick and wounded.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Saeed |first1=Abdullah |title=Human Rights and Islam: An Introduction to Key Debates between Islamic Law and International Human Rights Law |date=2018 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-78471-658-5 |page=299 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9ChWDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT299 |access-date=9 May 2019 |archive-date=5 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200105042441/https://books.google.com/books?id=9ChWDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT299 |url-status=live }}</ref> The many requirements on how prisoners of war should be treated included providing shelter, food and clothing, respecting their cultures, and preventing any acts of execution, rape, or revenge. Some of these principles were not codified in ] international law until modern times.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Malekian|first1=Farhad|title=Principles of Islamic International Criminal Law: A Comparative Search|date=2011|publisher=]|isbn=978-90-04-20396-9|page=335|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MPNamMveFVMC&pg=PA335|access-date=9 May 2019|archive-date=31 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191231212648/https://books.google.com/books?id=MPNamMveFVMC&pg=PA335|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| During the European ], international law was concerned primarily with the purpose and legitimacy of war, seeking to determine what constituted |

During the European ], international law was concerned primarily with the purpose and legitimacy of war, seeking to determine what constituted ]".{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|p=35}} The Greco-Roman concept of natural law was combined with religious principles by Jewish philosopher ] (1135–1204) and Christian theologian ] (1225–1274) to create the new discipline of the "law of nations", which unlike its eponymous Roman predecessor, applied natural law to relations between states.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=36-39}}{{Sfn|Rodin|Sorabji|2006|pp=14, 24-25}} In Islam, a similar framework was developed wherein the law of nations was derived, in part, from the principles and rules set forth in treaties with non-Muslims.{{Sfn|Khadduri|1956|pp=360–361}} | ||

| === Emergence of modern international law === | === Emergence of modern international law === | ||

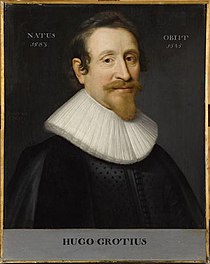

| The 15th century witnessed a confluence of factors that contributed to an accelerated development of international law. Italian jurist ] (1313–1357) was considered the founder of ]. Another Italian jurist, ] (1327–1400), provided commentaries and compilations of Roman, ecclesiastical, and ], creating an organised source of law that could be referenced by different nations.{{Citation needed|date=April 2023}} ] (1552–1608) took a secular view to international law, authoring various books on issues in international law, notably ''Law of War'', which provided comprehensive commentary on the laws of war and treaties.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=94-101}} ] (1486–1546), who was concerned with the treatment of ] by Spain, invoked the law of nations as a basis for their innate dignity and rights, articulating an early version of sovereign equality between peoples.{{Sfn|von Glahn|1992|pp=27-28}} ] (1548–1617) emphasised that international law was founded upon natural law and human positive law.{{Sfn|Head|1994|p=614}}{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=84–91}}]]]Dutch jurist ] (1583–1645) is widely regarded as the father of international law,{{Sfn|Head|1994|pp=607–608}} being one of the first scholars to articulate an international order that consists of a "society of states" governed not by ] or ] but by actual laws, mutual agreements, and customs.{{Sfn|Yepremyan|2022|pp=197-200}} Grotius secularised international law;{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2020|p=90}} his 1625 work, ], laid down a system of ] that bind all nations regardless of local custom or law.{{Sfn|Head|1994|pp=607–608}} He inspired two nascent schools of international law, the naturalists and the positivists.{{Sfn|Head|1994|pp=616–617}} In the former camp was German jurist ] (1632–1694), who stressed the supremacy of the law of nature over states.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|p=147}}{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2020|p=342}} His 1672 work, ''Of the Law of Nature And Nations,'' expanded on the theories of Grotius and grounded natural law to ] and the secular world, asserting that it regulated only external acts of states.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|p=147}} Pufendorf challenged the ] that the state of nature was one of war and conflict, arguing that the natural state of the world is actually peaceful but weak and uncertain without adherence to the law of nations.{{Sfn|Saastamoinen|1995|pp=14, 36}} The actions of a state consist of nothing more than the sum of the individuals within that state, thereby requiring the state to apply a fundamental law of reason, which is the basis of natural law. He was among the earliest scholars to expand international law beyond European Christian nations, advocating for its application and recognition among all peoples on the basis of shared humanity.{{Sfn|Saastamoinen|1995|p=168}} | |||

| The 15th century witnessed a confluence of factors that contributed to an accelerated development of international law into its current framework. The influx of ] from the ], along with the introduction of the ], spurred the ]. Increased ] by Europeans challenged scholars to devise a conceptual framework for relations with different peoples and cultures. The formation of centralized states such as ] and ] brought more wealth, ambition, and trade, which in turn required increasingly more sophisticated rules and regulations. | |||

| In contrast, ] writers, such as ]e (1590–1661) in England and ] (1673–1743) in the Netherlands, argued that international law should derive from the actual practice of states rather than Christian or Greco-Roman sources. The study of international law shifted away from its core concern on the law of war and towards the domains such as the law of the sea and commercial treaties.{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=164–172}} The positivist school grew more popular as it reflected accepted views of state sovereignty and was consistent with the empiricist approach to philosophy that was then gaining acceptance in Europe.{{Sfn|Head|1994|p=617}} | |||

| The Italian peninsula, divided among various city-states with complex and often fractious relationships, was subsequently an early incubator of international law theory. Jurist and law professor ] (1313–1357), who was well versed in Roman and ], contributed to the increasingly relevant area of "]", which concerns disputes between private individuals and entities in different sovereign jurisdictions; he is thus considered the founder of ]. Another Italian jurist and law professor, ] (1327–1400), provided voluminous commentaries and compilations of Roman, ecclesiastical, and ], thus creating an organized source of law that could be referenced by different nations. The most famous contributor from the region, ] (1552–1608), is considered a founder of international law, authoring one of the earliest works on the subject, ''De Legationibus Libri Tres'', in 1585. He wrote several more books on various issues in international law, notably ''De jure belli libri tres'' (''Three Books on the Law of War''), which provided comprehensive commentary on the laws of war and treaties, ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Spain, whose ] spurred ] of economic and intellectual development in the 16th and 17th centuries, produced major contributors to international law. ] (1486–1546), who was concerned with the treatment of the indigenous peoples by Spain, invoked the law of nations as a basis for their innate dignity and rights, articulating an early version of sovereign equality between peoples. ] (1548–1617) emphasized that international law was founded upon the law of nature. | |||

| The Dutch jurist ] (1583–1645) is widely regarded as the most seminal figure in international law, being one of the first scholars to articulate an international order that consists of a "society of states" governed not by ] or ] but by actual laws, mutual agreements, and customs.<ref>Hedley Bull; ]; Benedict Kingsbury) (eds.). ''Hugo Grotius and International Relations''. Oxford: Oxford UP. {{ISBN|978-0-19-825569-7}}.</ref> Grotius secularized international law and organized it into a comprehensive system; his 1625 work, '']'' (''On the Law of War and Peace''), laid down a system of ] that bind all nations regardless of local custom or law. He also emphasized the ], which was not only relevant to the growing number of European states exploring and ] the world, but remains a cornerstone of international law today. Although the modern study of international law would not begin until the early 19th century, the 16th-century scholars Gentili, Vitoria and Grotius laid the foundations and are widely regarded as the "fathers of international law".<ref name="Jr.20122">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jYvmAgAAQBAJ|title=How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization|author=Thomas Woods Jr.|date=18 September 2012|publisher=Regnery Publishing, Incorporated, An Eagle Publishing Company|isbn=978-1-59698-328-1|pages=5, 141–142|access-date=14 November 2015|archive-date=7 May 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160507014932/https://books.google.com/books?id=jYvmAgAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Establishment of Westphalian system === | |||

| Grotius inspired two nascent schools of international law, the naturalists and the positivists. In the former camp was ] jurist ] (1632–94), who stressed the supremacy of the law of nature over states. His 1672 work, ''De iure naturae et gentium,'' expanded on the theories of Grotius and grounded natural law to ] and the secular world, asserting that it regulates only the external acts of states. Pufendorf challenged the ] that the state of nature was one of war and conflict, arguing that the natural state of the world is actually peaceful but weak and uncertain without adherence to the law of nations. The actions of a state consist of nothing more than the sum of the individuals within that state, thereby requiring the state to apply a fundamental law of reason, which is the basis of natural law. He was among the earliest scholars to expand international law beyond European Christian nations, advocating for its application and recognition among all peoples on the basis of shared humanity. | |||

| The developments of the 17th century culminated at the conclusion of the ] in 1648, which is considered the seminal event in international law.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2020|pp=331-332}} The resulting ] is said to have established the current international legal order characterised by independent ]s, which have equal sovereignty regardless of their size and power, defined primarily by non-interference in the domestic affairs of sovereign states, although historians have challenged this narrative.{{Sfn|Osiander|2001|pp=260–261}} The idea of ] further solidified the concept and formation of nation-states.{{Sfn|Osiander|2001|p=283}} Elements of the naturalist and positivist schools were synthesised, notably by German philosopher ] (1679–1754) and Swiss jurist ] (1714–1767), both of whom sought a middle-ground approach.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2020|pp=343}}{{Sfn|Nussbaum|1954|pp=150–164}} During the 18th century, the positivist tradition gained broader acceptance, although the concept of natural rights remained influential in international politics, particularly through the republican revolutions of the United States and France.{{Citation needed|date=April 2023}} | |||

| Until the mid-19th century, relations between states were dictated mostly by treaties, agreements between states to behave in a certain way, unenforceable except by force, and nonbinding except as matters of honour and faithfulness.{{Citation needed|date=April 2023}} One of the first instruments of modern armed conflict law was the ] of 1863, which governed the conduct of warfare during the ], and is noted for codifying rules and articles of war adhered to by nations across the world, including the United Kingdom, Prussia, Serbia and Argentina.{{Sfn|Solis|2016|p=45}} In the years that followed, numerous other treaties and bodies were created to regulate the conduct of states towards one another, including the ] in 1899, and the ] and ], the first of which was passed in 1864.{{Sfn|Northedge|1986|pp=10–11}}{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2020|pp=396-398}} | |||

| In contrast, ] writers, such as ]e (1590–1661) in England and ] (1673–1743) in the Netherlands, argued that international law should derive from the actual practice of states rather than Christian or Greco-Roman sources. The study of international law shifted away from its core concern on the law of war and towards the domains such as the law of the sea and commercial treaties. The positivist school made use of the new scientific method and was in that respect consistent with the empiricist and inductive approach to philosophy that was then gaining acceptance in Europe. | |||

| === 20th and 21st century developments === | |||

| ==== Establishment of "Westphalian system" ==== | |||

| ] in 1979]] | |||

| ] is regarded as the Father of international law.<ref>{{cite book|title=How The Catholic Church Built Western Civilization|last=Woods|first=Thomas E. (Jr.)|publisher=Regnery Publishing|year=2005|isbn=978-0-89526-038-3|location=Washington, DC|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/howcatholicchurc0000wood}}</ref>]] | |||

| Colonial expansion by European powers reached its peak in the late 19th century and its influence began to wane following the unprecedented bloodshed of ], which spurred the creation of international organisations. The ] was founded to safeguard peace and security.{{Sfn|Northedge|1986|p=1}}{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|pp=482–484}} International law began to incorporate notions such as ] and ].{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|pp=487–489}} The ] (UN) was established in 1945 to replace the League, with an aim of maintaining collective security.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|pp=493–494}} A more robust international legal order followed, buttressed by institutions such as the ] (ICJ) and the ] (UNSC).{{Sfn|Evans|2014|p=22}} The ] (ILC) was established in 1947 to develop and codify international law.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|pp=493–494}} | |||

| The developments of the 17th century came to a head at the conclusion of the "]" in 1648, which is considered to be the seminal event in international law. The resulting "]" established the current international legal order characterized by independent sovereign entities known as "]s", which have equality of sovereignty regardless of size and power, defined primarily by the inviolability of borders and non-interference in the domestic affairs of sovereign states. From this period onward, the concept of the nation-state evolved rapidly, and with it the development of complex relations that required predictable, widely accepted rules and guidelines. The idea of ], in which people began to see themselves as citizens of a particular group with a distinct national identity, further solidified the concept and formation of nation-states. | |||

| In the 1940s through the 1970s, the dissolution of the Soviet bloc and ] across the world resulted in the establishment of scores of newly independent states.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|pp=498–499}} As these former colonies became their own states, they adopted European views of international law.{{Sfn|Head|1994|pp=620–621}} A flurry of institutions, ranging from the ] (IMF) to the ] (WTO), furthered the development of a multilateralist approach as states chose to compromise on sovereignty to benefit from international cooperation.{{Sfn|Head|1994|p=606}} Since the 1980s, there has been an increasing focus on the phenomenon of ] and on protecting human rights on the global scale, particularly when minorities or indigenous communities are involved, as concerns are raised that globalisation may be increasing inequality in the international legal system.{{Sfn|Evans|2014|pp=23-24}} | |||

| Elements of the ] and positivist schools became synthesised, most notably by German philosopher ] (1679–1754) and ] jurist ] (1714–67), both of whom sought a middle-ground approach in international law. During the 18th century, the positivist tradition gained broader acceptance, although the concept of natural rights remained influential in international politics, particularly through the republican revolutions of the ] and ]. Not until the 20th century would natural rights gain further salience in international law. | |||

| Several legal systems developed in ], including the codified systems of continental European states known as ], and ], which is based on decisions by judges and not by written codes. Other areas around the world developed differing legal systems, with the Chinese legal tradition dating back more than four thousand years, although at the end of the 19th century, there was still no written code for civil proceedings in China.<ref>''China and Her People'', ], L. C. Page, Boston 1906 page 203</ref> | |||

| Until the mid-19th century, relations between states were dictated mostly by treaties, agreements between states to behave in a certain way, unenforceable except by force, and nonbinding except as matters of honor and faithfulness. One of the first instruments of modern international law was the ] of 1863, which governed the conduct of U.S. forces during the ], and is considered to be the first written recitation of the rules and articles of war adhered to by all civilized nations. This led to the first prosecution for war crimes, in which a Confederate commandant was tried and hanged for holding prisoners of war in cruel and depraved conditions at ], Georgia. In the years that followed, other states subscribed to limitations of their conduct, and numerous other treaties and bodies were created to regulate the conduct of states towards one another, including the ] in 1899, and the ] and ], the first of which was passed in 1864.] (1864) is one of the earliest formulations of international law|alt=|left]] | |||

| The concept of sovereignty was spread throughout the world by European powers, which had established colonies and spheres of influences over virtually every society. Positivism reached its peak in the late 19th century and its influence began to wane following the unprecedented bloodshed of the ], which spurred the creation of international organisations such as the ], founded in 1919 to safeguard peace and security. International law began to incorporate more naturalist notions such as ] and ]. The ] accelerated this development, leading to the establishment of the ], whose ] enshrined principles such as nonaggression, nonintervention, and collective security. A more robust international legal order followed, which was buttressed by institutions such as the ] and the ], and by multilateral agreements such as the ]. The ] (ILC) was established in 1947 to help develop, codify, and strengthen international law | |||

| Having become geographically international through the colonial expansion of the European powers, international law became truly international in the 1960s and 1970s, when rapid ] across the world resulted in the establishment of scores of newly independent states. The varying political and economic interests and needs of these states, along with their diverse cultural backgrounds, infused the hitherto European-dominated principles and practices of international law with new influences. A flurry of institutions, ranging from the ] to the ], furthered the development of a stable, predictable legal order with rules governing virtually every domain. The phenomenon of ], which has led to the rapid integration of the world in economic, political, and even cultural terms, presents one of the greatest challenges to devising a truly international legal system. | |||

| == Sources of international law == | == Sources of international law == | ||

| {{Main|Sources of international law |

{{Main|Sources of international law}} | ||

| Sources of international law have been influenced by a range of political and legal theories. During the 20th century, it was recognized by legal ] that a ] could limit its authority to act by consenting to an agreement according to the contract principle '']''. This consensual view of international law was reflected in the 1920 Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice, and remains preserved in Article 7 of the ICJ Statute.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171121122608/http://www.un.org/en/documents/charter/index.shtml |date=21 November 2017 }}, United Nations, 24 October 1945, 1 UNTS, XVI</ref> The ] applied by the community of nations are listed under Article 38 of the ], which is considered authoritative in this regard: | |||

| The ] applied by the community of nations are listed in Article 38(1) of the ], which is considered authoritative in this regard. These categories are, in order, ], ], general legal principles and judicial decisions and the teachings of prominent legal scholars as "a subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law".{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=6}} It was originally considered that the arrangement of the sources sequentially would suggest an implicit hierarchy of sources, however the statute does not provide for a hierarchy and other academics have argued that therefore the sources must be equivalent.{{Sfn|Prost|2017|pp=288–289}}{{Sfn|Shelton|2006|p=291}} | |||

| # International treaties and conventions; | |||

| # International custom as derived from the "general practice" of states; and | |||

| # General legal principles "recognized by civilized nations". | |||

| General principles of law have been defined in the Statute as "general principles of law recognized by civilized nations" but there is no academic consensus about what is included within this scope.{{Sfn|Shao|2021|pp=219–220}}{{Sfn|Bassiouni|1990|p=768}} They are considered to be derived from both national and international legal systems, although including the latter category has led to debate about potential cross-over with international customary law.{{Sfn|Shao|2021|p=221}}{{Sfn|Bassiouni|1990|p=772}} The relationship of general principles to treaties or custom has generally been considered to be "fill the gaps" although there is still no conclusion about their exact relationship in the absence of a hierarchy.{{Sfn|Shao|2021|pp=246–247}} | |||

| Additionally, judicial decisions and the teachings of prominent international law scholars may be applied as "subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law". | |||

| Many scholars agree that the fact that the sources are arranged sequentially suggests an implicit hierarchy of sources.<ref>{{cite book|title=Fundamental Perspectives on International Law|last=Slomanson|first=William|publisher=Wadsworth|year=2011|location=Boston, USA|pages=26–27}}</ref> However, the language of Article 38 does not explicitly hold such a hierarchy, and the decisions of the international courts and tribunals do not support such a strict hierarchy. By contrast, Article 21 of the ] clearly defines a hierarchy of applicable law (or sources of international law). | |||

| === Treaties === | === Treaties === | ||

| {{Main|Treaty}} | |||

| International treaty law comprises obligations expressly and voluntarily accepted by states between themselves in ]. The ] defines a treaty as follows: | |||

| ] | |||

| <blockquote>"treaty" means an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation<ref>Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, Article 2, 1(a)</ref></blockquote> | |||

| {{legend|#00FF00|Parties}}{{legend|#008000|Signatories}}|225x225px]] | |||

| This definition has led case-law to define a treaty as an international agreement that meets the following criteria: | |||

| A treaty is defined in Article 2 of the ] (VCLT) as "an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation".{{Sfn|Gardiner|2008|p=20}} The definition specifies that the parties must be states, however international organisations are also considered to have the capacity to enter treaties.{{Sfn|Gardiner|2008|p=20}}{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=179}} Treaties are binding through the principle of '']'', which allows states to create legal obligations on themselves through consent.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=9}}{{Sfn|Klabbers|1996|p=38–40}} The treaty must be governed by international law; however it will likely be interpreted by national courts.{{Sfn|Gardiner|2008|p=21}} The VCLT, which codifies several bedrock principles of treaty interpretation, holds that a treaty "shall be interpreted in ] in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose".{{Sfn|Dothan|2019|p=766–767}} This represents a compromise between three theories of interpretation: the textual approach which looks to the ordinary meaning of the text, the subjective approach which considers factors such as the drafters' intention, and the teleological approach which interprets a treaty according to its objective and purpose.{{Sfn|Dothan|2019|p=766–767}}{{Sfn|Jacobs|1969|p=319}} | |||

| A state must express its consent to be bound by a treaty through signature, exchange of instruments, ratification, acceptance, approval or accession. Accession refers to a state choosing to become party to a treaty that it is unable to sign, such as when establishing a regional body. Where a treaty states that it will be enacted through ratification, acceptance or approval, the parties must sign to indicate acceptance of the wording but there is no requirement on a state to later ratify the treaty, although they may still be subject to certain obligations.{{Sfn|Evans|2014|pp=171–175}} When signing or ratifying a treaty, a state can make a unilateral statement to negate or amend certain legal provisions which can have one of three effects: the reserving state is bound by the treaty but the effects of the relevant provisions are precluded or changes, the reserving state is bound by the treaty but not the relevant provisions, or the reserving state is not bound by the treaty.{{Sfn|Aust|2007|p=131}}{{Sfn|Gardiner|2008|pp=84–85}} An interpretive declaration is a separate process, where a state issues a unilateral statement to specify or clarify a treaty provision. This can affect the interpretation of the treaty but it is generally not legally binding.{{Sfn|Gardiner|2008|pp=86–87}}{{Sfn|Evans|2014|p=191}} A state is also able to issue a conditional declaration stating that it will consent to a given treaty only on the condition of a particular provision or interpretation.{{Sfn|Gardiner|2008|p=90}} | |||

| # Criterion 1: Requirement of an agreement, meetings of wills (''concours de volonté'') | |||

| # Criterion 2: Requirement of being concluded between subjects of international law: this criterion excludes agreements signed between States and private corporations, such as ]. In the 1952 '']'' case, the ICJ did not have jurisdiction for a dispute over the ] being nationalized as the dispute emerged from an alleged breach of contract between a private company and a State. | |||

| # Criterion 3: Requirement to be governed by international law: any agreement governed by any domestic law will not be considered a treaty. | |||

| # Criterion 4: No requirement of instrument: A treaty can be embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments. This is best exemplified in exchange of letters - (''échange de lettres''). For example, if France sends a letter to the United States to say, increase their contribution in the budget of the North Atlantic Alliance, and the US accepts the commitment, a treaty can be said to have emerged from the exchange. | |||

| # Criterion 5: No requirement of designation: the designation of the treaty, whether it is a "convention", "pact" or "agreement" has no impact on the qualification of said agreement as being a treaty. | |||

| # Unwritten Criterion: requirement for the agreement to produce legal effects: this unwritten criterion is meant to exclude agreements which fulfill the above-listed conditions, but are not meant to produce legal effects, such as ] | |||

| Article 54 of the VCLT provides that either party may terminate or withdraw from a treaty in accordance with its terms or at any time with the consent of the other party, with 'termination' applying to a bilateral treaty and 'withdrawal' applying to a multilateral treaty.{{Sfn|Aust|2007|pp=277–278, 288}} Where a treaty does not have provisions allowing for termination or withdrawal, such as the Genocide Convention, it is prohibited unless the right was implied into the treaty or the parties had intended to allow for it.{{Sfn|Aust|2007|p=289–290}} A treaty can also be held invalid, including where parties act ultra vires or negligently, where execution has been obtained through fraudulent, corrupt or forceful means, or where the treaty contradicts peremptory norms.{{Sfn|Aust|2007|p=312–319}} | |||

| Where there are disputes about the exact meaning and application of national laws, it is the responsibility of the courts to decide what the law means. In international law, interpretation is within the domain of the states concerned, but may also be conferred on judicial bodies such as the International Court of Justice, by the terms of the treaties or by consent of the parties. Thus, while it is generally the responsibility of states to interpret the law for themselves, the processes of diplomacy and availability of supra-national judicial organs routinely provide assistance to that end. | |||

| === International custom === | |||

| The ], which codifies several bedrock principles of treaty interpretation, holds that a treaty "shall be interpreted in ] in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose." This represents a compromise between three different theories of interpretation: | |||

| {{Main|Customary international law}} | |||

| Customary international law requires two elements: a consistent practice of states and the conviction of those states that the consistent practice is required by a legal obligation, referred to as '']''.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|pp=23-24}}{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2022|loc=section 3.3.1}} Custom distinguishes itself from treaty law as it is binding on all states, regardless of whether they have participated in the practice, with the exception of states who have been ]s during the process of the custom being formed and special or local forms of customary law.{{Sfn|Thirlway|2014|pp=54–56}} The requirement for state practice relates to the practice, either through action or failure to act, of states in relation to other states or international organisations.{{Sfn|Thirlway|2014|p=63}} There is no legal requirement for state practice to be uniform or for the practice to be long-running, although the ICJ has set a high bar for enforcement in the cases of '']'' and '']''.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|pp=24-25}} There has been legal debate on this topic with the only prominent view on the length of time necessary to establish custom explained by ] as varying "according to the nature of the case".{{Sfn|D'Amato|1971|pp=57-58}} The practice is not required to be followed universally by states, but there must be a "general recognition" by states "whose interests are specially affected".{{Sfn|Thirlway|2014|p=65}} | |||

| The second element of the test, ''opinio juris,'' the belief of a party that a particular action is required by the law is referred to as the subjective element.{{Sfn|Harrison|2011|p=13}} The ICJ has stated in ] in ''North Sea Continental Shelf'' that, "Not only must the acts concerned amount to a settled practice, but they must also be such, or be carried out in such a way, as to be evidence of a belief that this practice is rendered obligatory by the existence of a rule of law requiring it".{{Sfn|Thirlway|2014|pp=74–76}} A committee of the ] has argued that there is a general presumption of an ''opinio juris'' where state practice is proven but it may be necessary if the practice suggests that the states did not believe it was creating a precedent.{{Sfn|Thirlway|2014|pp=74–76}} The test in these circumstances is whether ''opinio juris'' can be proven by the states' failure to protest.{{Sfn|D'Amato|1971|pp=68–70}} Other academics believe that intention to create customary law can be shown by states including the principle in multiple bilateral and multilateral treaties, so that treaty law is necessary to form customs.{{Sfn|D'Amato|1971|pp=70–71}} | |||

| * The '''textual approach''', a restrictive interpretation that looks to the "ordinary meaning" of the text, assigning considerable weight to the actual text. | |||

| * The '''subjective approach''', which takes into consideration factors such as the ideas behind the treaty, the context of the treaty's creation, and what the drafters intended. | |||

| * The '''effective approach''', which interprets a treaty "in the light of its object and purpose", i.e. based on what best suits the goal of the treaty. | |||

| The adoption of the VCLT in 1969 established the concept of '']'', or peremptory norms, which are "a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can be modified only by a subsequent norm of general international law having the same character".{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|pp=508-509}} Where customary or treaty law conflicts with a peremptory norm, it will be considered invalid, but there is no agreed definition of ''jus cogens''.{{Sfn|Linderfalk|2007|p=854}} Academics have debated what principles are considered peremptory norms but the mostly widely agreed is the principle of non-use of force.{{Sfn|Linderfalk|2007|p=859}} The next year, the ICJ defined ''erga omnes'' obligations as those owed to “the international community as a whole”, which included the illegality of genocide and human rights.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|pp=508-509}} | |||

| The foregoing are general rules of interpretation, and do no preclude the application of specific rules for particular areas of international law. | |||

| === Monism and dualism === | |||

| *'']'' , ICJ had no jurisdiction to hear a dispute between the UK government and a private Greek businessman under the terms of a treaty. | |||

| *'']'' , the ICJ did not have jurisdiction for a dispute over the ] being nationalized. | |||

| *''] (Islamic Republic of Iran v United States of America)'' , rejected dispute over damage to ships which hit a mine. | |||

| === International custom === | |||

| Customary international law is derived from the consistent practice of States accompanied by '']'', i.e. the conviction of states that the consistent practice is required by a legal obligation. Judgments of international tribunals as well as scholarly works have traditionally been looked to as persuasive sources for custom in addition to direct evidence of state behavior. Attempts to codify customary international law picked up momentum after the Second World War with the formation of the ] (ILC) under the aegis of the ]. Codified customary law is made the binding interpretation of the underlying custom by agreement through treaty. For states not party to such treaties, the work of the ILC may still be accepted as custom applying to those states. General principles of law are those commonly recognized by the major legal systems of the world. Certain norms of international law achieve the binding force of ]s (''jus cogens'') as to include all states with no permissible derogations.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.irwinlaw.com/cold/non-derogable_norm_of_international_law|title=Non-derogable norm of international law {{!}} Irwin Law|website=www.irwinlaw.com|access-date=22 April 2019|archive-date=22 April 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190422051449/https://www.irwinlaw.com/cold/non-derogable_norm_of_international_law|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *'']'' (1950), recognizing custom as a source of international law, but a practice of giving asylum was not part of it.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Colombia/Peru - Asylum - Judgment of 20 November 1950 - (including the declaration of Judge Zoricic) - Judgments ICJ 6; ICJ Reports 1950, p 266; ICJ Rep 266 (20 November 1950)|url=http://www.worldlii.org/int/cases/ICJ/1950/6.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210227000228/http://www.worldlii.org/int/cases/ICJ/1950/6.html|archive-date=27 February 2021|access-date=22 April 2019|website=www.worldlii.org}}</ref> | |||

| *'']'' (1970), finding that only the state where a corporation is incorporated (not where its major shareholders reside) has standing to bring an action for damages for economic loss. | |||

| === Statehood and responsibility === | |||

| {{See also|Monism and dualism in international law}} | {{See also|Monism and dualism in international law}} | ||

| There are generally two approaches to the relationship between international and national law, namely monism and dualism.{{Sfn|Shelton|2011|p=2}} Monism assumes that international and national law are part of the same legal order.{{Sfn|Björgvinsson|2015|pp=19–20}} Therefore, a treaty can directly become part of national law without the need for enacting legislation, although they will generally need to be approved by the legislature. Once approved, the content of the treaty is considered as a law that has a higher status than national laws. Examples of countries with a monism approach are France and the Netherlands.{{Sfn|Aust|2007|pp=183–185}} The dualism approach considers that national and international law are two separate legal orders, so treaties are not granted a special status.{{Sfn|Shelton|2011|p=2}}{{Sfn|Aust|2007|p=187}} The rules in a treaty can only be considered national law if the contents of the treaty have been enacted first.{{Sfn|Aust|2007|p=187}} An example is the United Kingdom; after the country ratified the ], the convention was only considered to have the force of law in national law after ] passed the ].{{Sfn|Aust|2007|pp=189–192}} | |||

| International law establishes the framework and the criteria for identifying ] as the fundamental actors in the international legal system. As the existence of a state presupposes control and ] over territory, international law deals with the acquisition of territory, ] and the legal responsibility of states in their conduct with each other. International law is similarly concerned with the treatment of individuals within state boundaries. There is thus a comprehensive regime dealing with group rights, the treatment of ], the rights of ]s, ], ] problems, and ] generally. It further includes the important functions of the maintenance of international peace and security, arms control, the pacific settlement of disputes and the regulation of the ] in international relations. Even when the law is not able to stop the outbreak of war, it has developed principles to govern the conduct of hostilities and the treatment of ]. International law is also used to govern issues relating to the global environment, the global commons such as ] and ], global communications, and ]. | |||

| In practice, the division of countries between monism and dualism is often more complicated; countries following both approaches may accept peremptory norms as being automatically binding and they may approach treaties, particularly later amendments or clarifications, differently than they would approach customary law.{{Sfn|Shelton|2011|pp=2-3}} Many countries with older or ] do not have explicit provision for international law in their domestic system and there has been an upswing in support for monism principles in relation to human rights and humanitarian law, as most principles governing these concepts can be found in international law.{{Sfn|Shelton|2011|pp=4-5}} | |||

| In theory, all states are ] and equal. As a result of the notion of sovereignty, the value and authority of international law is dependent upon the voluntary participation of states in its formulation, observance, and enforcement. Although there may be exceptions, it is thought by many international academics that most states enter into legal commitments with other states out of ] rather than adherence to a body of law that is higher than their own. As ] notes, "international law cannot exist in isolation from the political factors operating in the sphere of ]".<ref>Greig, D. W., ''International Law'', 2nd ed (Butterworths: London, 1976)</ref> | |||

| == International actors == | |||

| Traditionally, ]s and the ] were the sole subjects of international law. With the proliferation of ] over the last century, they have in some cases been recognized as relevant parties as well. Recent interpretations of ], ], and ] (e.g., ] (NAFTA) Chapter 11 actions) have been inclusive of corporations, and even of certain individuals. | |||

| {{Main|International legal system}} | |||

| === States === | |||

| A state is defined under Article 1 of the ] as a legal person with a permanent population, a defined territory, government and capacity to enter relations with other states. There is no requirement on population size, allowing micro-states such as San Marino and Monaco to be admitted to the UN, and no requirement of fully defined boundaries, allowing Israel to be admitted despite ]. There was originally an intention that a state must have ], but now the requirement is for a stable political environment. The final requirement of being able to enter relations is commonly evidenced by independence and sovereignty.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|pp=128–135}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Under the principle of '']'', all states are ] and equal,{{Sfn|Baker|1923|pp=11-12}} but ] often plays a significant role in political conceptions. A country may recognise another nation as a state and, separately, it may recognise that nation's government as being legitimate and capable of representing the state on the international stage.{{Sfn|von Glahn|1992|p=85}}{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=144}} There are two theories on recognition; the declaratory theory sees recognition as commenting on a current state of law which has been separately satisfied whereas the constitutive theory states that recognition by other states determines whether a state can be considered to have legal personality.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|pp=144-146}} States can be recognised explicitly through a released statement or tacitly through conducting official relations, although some countries have formally interacted without conferring recognition.{{Sfn|von Glahn|1992|p=86}} | |||

| Throughout the 19th century and the majority of the 20th century, states were protected by absolute immunity, so they could not face criminal prosecution for any actions. However a number of countries began to distinguish between ''acta jure gestionis'', commercial actions, and ''acta jure imperii'', government actions; the restrictive theory of immunity said states were immune where they were acting in a governmental capacity but not a commercial one. The European Convention on State Immunity in 1972 and the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and their Property attempt to restrict immunity in accordance with customary law.{{Sfn|Collins|Harris|2022|pp=340–341}} | |||

| The conflict between international law and national sovereignty is subject to vigorous debate and dispute in academia, diplomacy, and politics. Indeed, there is a growing trend toward judging a state's domestic actions in the light of international law and standards. Numerous people now view the nation-state as the primary unit of international affairs and believe that only states may choose to enter into commitments under international law voluntarily and that they have the right to follow their own counsel when it comes to the interpretation of their commitments. Certain scholars{{who|date=August 2012}} and political leaders feel that these modern developments endanger nation-states by taking power away from state governments and ceding it to international bodies such as the U.N. and the World Bank, argue that international law has evolved to a point where it exists separately from the mere consent of states, and discern a legislative and judicial process to international law that parallels such processes within domestic law. This especially occurs when states violate or deviate from the expected standards of conduct adhered to by all civilized nations. | |||

| === Individuals === | |||

| A number of states place emphasis on the principle of territorial sovereignty, thus seeing states as having free rein over their internal affairs. Other states oppose this view. One group of opponents of this point of view, including many ] nations, maintain that all civilized nations have certain norms of conduct expected of them, including the prohibition of ], ] and the ], ], ], and ], and that violation of these universal norms represents a crime, not only against the individual victims, but against humanity as a whole. States and individuals who subscribe to this view opine that, in the case of the individual responsible for violation of international law, he "is become, like the ] and the ]r before him, '']'', an enemy of all mankind",<ref>Janis, M. and Noyes, J. International Law": Cases and Commentary (3rd ed.), Prosecutor v. Furundžija, Page 148 (2006)</ref> and thus subject to prosecution in a fair trial before any fundamentally just tribunal, through the exercise of ]. | |||

| Historically individuals have not been seen as entities in international law, as the focus was on the relationship between states.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=121}}{{Sfn|Klabbers|2013|p=107}} As human rights have become more important on the global stage, being codified by the ] (UNGA) in the ] in 1948, individuals have been given the power to defend their rights to judicial bodies.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2013|pp=109–112}} International law is largely silent on the issue of ] with the exception of cases of ] or where someone is claiming rights under ] but as, argued by the political theorist ], human rights are often tied to someone’s nationality.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|pp=132–133}} The ] allows individuals to petition the court where their rights have been violated and national courts have not intervened and the ] and the ] have similar powers.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2013|pp=109–112}} | |||

| === International organisations === | |||

| Though European democracies tend to support broad, universalistic interpretations of international law, many other democracies have differing views on international law. Several democracies, including ], ] and the ], take a flexible, eclectic approach, recognizing aspects of international law such as territorial rights as universal, regarding other aspects as arising from treaty or custom, and viewing certain aspects as not being subjects of international law at all. ] in the developing world, due to their past colonial histories, often insist on non-interference in their internal affairs, particularly regarding human rights standards or their peculiar institutions, but often strongly support international law at the bilateral and multilateral levels, such as in the United Nations, and especially regarding the use of force, disarmament obligations, and the terms of the ]. | |||

| Traditionally, sovereign states and the ] were the sole subjects of international law. With the proliferation of ] over the last century, they have also been recognised as relevant parties.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=73}} One definition of international organisations comes from the ILC's 2011 Draft Articles on the Responsibility of International Organizations which in Article 2(a) states that it is "an organization established by treaty or other instrument governed by international law and possessing its own international legal personality".{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|pp=166–167}} This definition functions as a starting point but does not recognise that organisations can have no separate personality but nevertheless function as an international organisation.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|pp=166–167}} The ] has emphasised a split between ] (IGOs), which are created by inter-governmental agreements, and ] (INGOs).{{Sfn|Archer|2014|pp=32–33}} All international organisations have members; generally this is restricted to states, although it can include other international organisations.{{Sfn|Schermers|Blokker|2011|p=61}} Sometimes non-members will be allowed to participate in meetings as observers.{{Sfn|Schermers|Blokker|2011|p=63}} | |||

| The '']'' sets out a list of international organisations, which include the UN, the WTO, the World Bank and the IMF.{{Sfn|Mueller|1997|p=106}}{{Sfn|Klabbers|2013|pp=84–85}} Generally organisations consist of a plenary organ, where member states can be represented and heard; an executive organ, to decide matters within the competence of the organisation; and an administrative organ, to execute the decisions of the other organs and handle secretarial duties.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|pp=93-94}} International organisations will typically provide for their privileges and immunity in relation to its member states in their constitutional documents or in multilateral agreements, such as the ].{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|pp=171–172}} These organisations also have the power to enter treaties, using the ] as a basis although it is not yet in force.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=179}} They may also have the right to bring legal claims against states depending, as set out in ''Reparation for Injuries'', where they have legal personality and the right to do so in their constitution.{{Sfn|Brownlie|Crawford|2012|p=180}} | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| === |

==== United Nations ==== | ||

| The UNSC has the power under Chapter VII of the UN Charter to take decisive and binding actions against states committing “a threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or an act of aggression” for ] although prior to 1990, it has only intervened once, in the case of Korea in 1950.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|p=493}}{{Sfn|Head|1994|pp=624–625}} This power can only be exercised, however, where a majority of member states vote for it, as well as receiving the support of the ] of the UNSC.{{Sfn|Slagter|van Doorn|Slomanson|2022|p=456}} This can be followed up with economic sanctions, military action, and similar uses of force.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=188}} The UNSC also has a wide discretion under Article 24, which grants "primary responsibility" for issues of international peace and security.{{Sfn|Orakhelashvili|2011|p=493}} The UNGA, concerned during the ] with the requirement that the USSR would have to authorise any UNSC action, adopted the ] of 3 November 1950, which allowed the organ to pass recommendations to authorize the use of force. This resolution also led to the practice of ], which has been notably been used in ] and ].{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|pp=194-195}} | |||

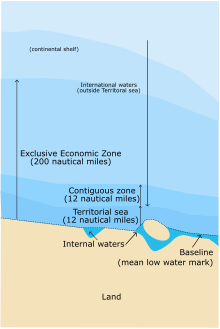

| {{Main|Law of the Sea}}The law of the sea is the area of international law concerning the principles and rules by which states and other entities interact in maritime matters.<ref>James Harrison, ''Making the Law of the Sea: A Study in the Development of International Law'' (2011), p. 1. {{verify source |date=August 2019 |reason=This ref was deleted (]) by a bug in VisualEditor and later restored by a bot from the original cite at ] cite #1 - please verify the cite's accuracy and remove this {verify source} template. ]}}</ref> It encompasses areas and issues such as navigational rights, sea mineral rights, and coastal waters jurisdiction. The law of the sea is distinct from ''']''' (also known as '''maritime law'''), which concerns relations and conduct at sea by private entities. | |||

| ==== International courts ==== | |||

| The ] (UNCLOS), concluded in 1982 and coming into force in 1994, is generally accepted as a codification of customary international law of the sea. | |||

| ] in ], which houses the ]]]There are more than one hundred international courts in the global community, although states have generally been reluctant to allow their sovereignty to be limited in this way.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=155}} The first known international court was the ], prior to World War I, when the ] (PCIJ) was established. The PCIJ was replaced by the ICJ, which is the best known international court due to its universal scope in relation to geographical jurisdiction and ].{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=159}} There are additionally a number of regional courts, including the ], the ] and the ].{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=160}} ] can also be used to resolve disputes between states, leading in 1899 to the creation of the Permanent Court of Arbitration which facilitates the process by maintaining a list of arbitrators. This process was used in the '']'' ] and to resolve disputes during the ].{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=158}} | |||

| The ICJ operates as one of the six organs of the UN, based out of ] with a panel of fifteen permanent judges.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=161}} It has jurisdiction to hear cases involving states but cannot get involved in disputes involving individuals or international organizations. The states that can bring cases must be party to the ], although in practice most states are UN members and would therefore be eligible. The court has ] over all cases that are referred to it and all matters specifically referred to in the UN Charter or international treaties, although in practice there are no relevant matters in the UN Charter.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|pp=163-165}} The ICJ may also be asked by an international organisation to provide an ] on a legal question, which are generally considered non-binding but authoritative.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=178}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' , the Fisheries case, concerning the limits of Norway's jurisdiction over neighboring waters | |||

| *'']'' (2014) dispute over international waters. | |||

| *''] case'' , between Nigeria and Cameroon | |||

| *'']'' (2013) | |||

| *] | |||

| *'']'' , UK sues Albania for damage to ships in international waters. First ICJ decision. | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' , successful claim for a greater share of the North Sea continental shelf by Germany. The ICJ held that the matter ought to be settled, not according to strict legal rules, but through applying equitable principles. | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| === International organizations === | |||

| {{Main|Intergovernmental organization|Global administrative law}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] and ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == Social and economic policy == | == Social and economic policy == | ||

| {{See also|Conflicts of laws}} | |||

| === Conflict of laws === | |||

| *'']'' , Sweden had jurisdiction over its guardianship policy, meaning that its laws overrode a conflicting guardianship order of the Netherlands. | |||

| {{See also|Conflicts of laws}}], also known as private international law, was originally concerned with ], determining which nation’s laws should govern a particular legal circumstance.{{Sfn|Briggs|2013|p=2}}{{Sfn|Collins|Harris|2022|p=4}} Historically the ] theory has been used although the definition is unclear, sometimes referring to reciprocity and sometimes being used as a synonym for private international law.{{Sfn|Beaumont|Anton|McEleavy|2011|p=374}}{{Sfn|Collins|Harris|2022|p=272}} Story distinguished it from "any absolute paramount obligation, superseding all discretion on the subject".{{Sfn|Collins|Harris|2022|p=272}} There are three aspects to conflict of laws – determining which domestic court has jurisdiction over a dispute, determining if a domestic court has jurisdiction and ]. The first question relates to whether the domestic court or a foreign court is best placed to decide the case.{{Sfn|North|1979|pp=7–8}} When determining the national law that should apply, the '']'' is the law that has been chosen to govern the case, which is generally foreign, and the ''lexi fori'' is the national law of the court making the determination. Some examples are ''lex domicilii'', the law of the domicile, and ''les patriae'', the law of the nationality.{{Sfn|Collins|Harris|2022|pp=15–16}} | |||

| *'']'' , the recognition of Mr Nottebohm's nationality, connected to diplomatic protection. | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| The rules which are applied to conflict of laws will vary depending on the national system determining the question. There have been attempts to codify an international standard to unify the rules so differences in national law cannot lead to inconsistencies, such as through the ] and the ].{{Sfn|North|1979|pp=9-11}}{{Sfn|Beaumont|Anton|McEleavy|2011|p=403}}{{Sfn|van Loon|2020|pp=6–7}} These treaties codified practice on the enforcement of international judgments, stating that a foreign judgment would be automatically recognised and enforceable where required in the jurisdiction where the party resides, unless the judgement was contrary to public order or conflicted with a local judgment between the same parties. On a global level, the ] was introduced in 1958 to internationalise the enforcement of ], although it does not have jurisdiction over court judgments.{{Sfn|Klabbers|2020|p=301}} | |||

| === Human rights === | |||

| {{Main|International human rights law|Human rights}} | |||