| Revision as of 18:01, 18 March 2023 editTassedethe (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators1,374,108 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit |

Latest revision as of 00:21, 14 December 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,458,276 edits Added date. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | Category:Saladin | #UCB_Category 32/41 |

| (39 intermediate revisions by 31 users not shown) |

| Line 2: |

Line 2: |

|

{{for|other members of the family|Ibn Athir}} |

|

{{for|other members of the family|Ibn Athir}} |

|

{{Infobox religious biography |

|

{{Infobox religious biography |

|

| era = ] |

|

| era = ] |

|

| image = |

|

| image = |

|

| caption = |

|

| caption = |

|

| name = '''Izz ad-Dīn Abū al-Hasan Ibn al-Athīr''' |

|

| name = '''Izz ad-Dīn Abū al-Hasan Ibn al-Athīr''' |

|

| title = ]<br/>Izz ad-Din |

|

| title = ]<br/>Izz ad-Din |

|

| religion = ] |

|

| religion = ] |

|

| birth_date = 1160 CE, Jazirat Ibn Umar, present-day ], ] |

|

| birth_date = May 12, 1160 CE, Jazirat Ibn Umar, present-day ], ] |

|

| death_date = {{AH|630|1233}}, ], ]<ref></ref> |

|

| death_date = {{AH|630|1233}}, ], ]<ref></ref> |

|

| denomination = ] |

|

| denomination = ] |

|

| jurisprudence = ]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Majd al-Din al-Mubarak bin Muhammad |first1=Ibn al-Athir al-Jazari |authorlink= |title=الشافي شرح مسند الشافعي 1-3 ج3 | publisher=Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah| date= |isbn= |page=612}}</ref> |

|

| jurisprudence = ]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Majd al-Din al-Mubarak bin Muhammad |first1=Ibn al-Athir al-Jazari |authorlink= |title=الشافي شرح مسند الشافعي 1-3 ج3 | publisher=Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah| date= |isbn= |page=612}}</ref> |

|

|

| creed = ]<ref>{{cite book|editor1=Nevin Reda|editor2=Yasmin Amin|title=Islamic Interpretive Tradition and Gender Justice: Processes of Canonization Subversion and Change|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ht3oDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA247|date=2020|publisher=]|isbn=9780228002963|page=247|quote='Ali ibn al-Athir 106 The Sunni historian and Ash'ari theologian Abū al-Hasan 'Izz al-Dīn 'Alī ibn Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Karīm ibn 'Abd al-Wāhid al-Jazarī al-Shaybānī was born in ] (Turkey) in 555/1160 and was of Arab descent.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author='Abd Allah ibn Muhammad ibn al-Tahir|url=https://www.arrabita.ma/blog/دور-أبي-ذر-الهروي-في-نشر-الأشعرية-بالمغ/|title=دور أبي ذر الهروي في نشر الأشعرية بالمغرب|language=ar|trans-title=The role of Abu Dharr al-Harawi in the spread of Ash'ari theology in Morocco|publisher=] (al-Rabita al-Muhammadiyya lil-'Ulamā' in Morocco)|archive-url=https://archive.today/20230413032508/https://www.arrabita.ma/blog/%D8%AF%D9%88%D8%B1-%D8%A3%D8%A8%D9%8A-%D8%B0%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%87%D8%B1%D9%88%D9%8A-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%86%D8%B4%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B4%D8%B9%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%BA/|archive-date=13 Apr 2023}}</ref> |

|

| creed = ]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.marefa.org/قائمة_أعلام_الأشاعرة_والماتريدية|title=List of Ash'ari & Maturidi scholars|website=marefa.org}}</ref> |

|

|

| region = |

|

| region = |

|

| notable_ideas= |

|

| notable_ideas = |

|

| main_interests = ], ] |

|

| main_interests = ], ] |

|

| works = <small>] and ] </small> |

|

| works = <small>] and ] </small> |

|

| influences = ]<br/>]<br/>] |

|

| influences = ]<br/>]<br/>] |

|

| influenced = ] |

|

| influenced = ] |

|

}} |

|

}} |

|

|

{{Ash'arism}} |

|

|

|

|

'''Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ash-Shaybānī''', better known as '''ʿAlī ʿIzz ad-] Ibn al-Athīr al-Jazarī''' ({{lang-ar|علي عز الدین بن الاثیر الجزري}}; 1160–1233) was a renowned ] expert, ], and ] who wrote in ] and was from the ] family.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Andersson |first1=Tobias |authorlink= |title=Early Sunnī Historiography A Study of the Tārīkh of Khalīfa B. Khayyāṭ | publisher=]| date=16 October 2018 |isbn=9789004383173 |page=62}}</ref> At the age of twenty-one he settled with his father in Mosul to continue his studies, where he devoted himself to the study of history and Islamic tradition. |

|

'''Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ash-Shaybānī''', better known as '''ʿAlī ʿIzz ad-] Ibn al-Athīr al-Jazarī''' ({{langx|ar|علي عز الدین بن الاثیر الجزري}}; 1160–1233) was a ] expert, ], and ] who wrote in ] and was from the ] family.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Andersson |first1=Tobias |authorlink= |title=Early Sunnī Historiography A Study of the Tārīkh of Khalīfa B. Khayyāṭ | publisher=]| date=16 October 2018 |isbn=9789004383173 |page=62}}</ref> At the age of twenty-one he settled with his father in Mosul to continue his studies, where he devoted himself to the study of history and Islamic tradition. |

|

|

|

|

|

== Biography == |

|

== Biography == |

|

Ibn al-Athir belonged to the Shayban lineage<ref>Kamaruzaman, A.F., Jamaludin, N., Fadzil, A.F.M., 2015. . Asian Social Science 11(23).</ref> of the large and influential ] tribe ],<ref>Kazhdan, Alexander P. 1991. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. .</ref><ref>Donner, Fred McGraw. “The Bakr B. Wā'il Tribes and Politics in Northeastern Arabia on the Eve of Islam.” Studia Islamica, no. 51, 1980, pp. 5–38. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1595370.</ref> who lived across upper ], and gave their name to the city of ].<ref>Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger. 1995. International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. 3 Southern Europe. Routledge. P 190.</ref><ref>Canard, M., Cahen, Cl., Yinanç, Mükrimin H., and Sourdel-Thomine, J. ‘’. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Ed. P. Bearman et al. Brill Reference Online. Web. 16 Nov. 2019. Accessed on 16 November 2019.</ref><ref>a. ''Historiography of the Ayyubid and Mamluk epochs'', Donald P. Little, '''The Cambridge History of Egypt''', Vol.1, ed. M. W. Daly, Carl F. Petry, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 415.<br/>b. ''Ibn al-Athir'', '''The A to Z of Islam''', ed. Ludwig W. Adamec, (Scarecrow Press, 2009), 135.<br/>c. Peter Partner, ''God of Battles: Holy wars of Christianity and Islam'', (Princeton University Press, 1997), 96.<br/>d. ''Venice and the Turks'', Jean-Claude Hocquet, '''Venice and the Islamic world: 828–1797''', edited by Stefano Carboni, (Editions Gallimard, 2006), 35 n17.<br/>e. Marc Ferro, ''Colonization: A Global History'', (Routledge, 1997), 6.<br/>f. Martin Sicker, ''The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna'', (Praeger Publishers, 2000), 69.</ref> He is also described to have been of ] origin.<ref>1. Philip G. Kreyenbroek , Oral Literature of Iranian Languages <br/> |

|

Ibn al-Athir belonged to the Shayban lineage<ref>Kamaruzaman, A.F., Jamaludin, N., Fadzil, A.F.M., 2015. . Asian Social Science 11(23).</ref> of the large and influential ] tribe ],<ref>{{cite journal | url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20111003122307511 | title=Ibn al-Athīr }}</ref><ref>Donner, Fred McGraw. “The Bakr B. Wā'il Tribes and Politics in Northeastern Arabia on the Eve of Islam.” Studia Islamica, no. 51, 1980, pp. 5–38. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1595370.</ref> who lived across upper ], and gave their name to the city of ].<ref>Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger. 1995. International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. 3 Southern Europe. Routledge. P 190.</ref><ref>Canard, M., Cahen, Cl., Yinanç, Mükrimin H., and Sourdel-Thomine, J. ‘’. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Ed. P. Bearman et al. Brill Reference Online. Web. 16 Nov. 2019. Accessed on 16 November 2019.</ref><ref>a. ''Historiography of the Ayyubid and Mamluk epochs'', Donald P. Little, '''The Cambridge History of Egypt''', Vol.1, ed. M. W. Daly, Carl F. Petry, (Cambridge University Press, 1998), 415.<br/>b. ''Ibn al-Athir'', '''The A to Z of Islam''', ed. Ludwig W. Adamec, (Scarecrow Press, 2009), 135.<br/>c. Peter Partner, ''God of Battles: Holy wars of Christianity and Islam'', (Princeton University Press, 1997), 96.<br/>d. ''Venice and the Turks'', Jean-Claude Hocquet, '''Venice and the Islamic world: 828–1797''', edited by Stefano Carboni, (Editions Gallimard, 2006), 35 n17.<br/>e. Marc Ferro, ''Colonization: A Global History'', (Routledge, 1997), 6.<br/>f. Martin Sicker, ''The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna'', (Praeger Publishers, 2000), 69.</ref> He is also described to have been of ] origin.<ref>1. Philip G. Kreyenbroek , Oral Literature of Iranian Languages <br/> |

|

2. Yasir Suleiman, "Language and identity in the Middle East and North Africa", Curzon Press, 1996, {{ISBN|0700704108}}, ''Ibn al-Athir, (d.1233), a Kurdish historian and biographer...''</ref> |

|

2. Yasir Suleiman, "Language and identity in the Middle East and North Africa", Curzon Press, 1996, {{ISBN|0700704108}}, ''Ibn al-Athir, (d.1233), a Kurdish historian and biographer...''</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

He was the brother of ] and Diyā' ad-Dīn Ibn Athir. Al-Athir lived a scholarly life in ], often visited ] and for a time traveled with ]'s army in ]. He later lived in ] and ]. His chief work was a history of the world, ''al-Kamil fi at-Tarikh'' ('']''). He died in the city of Mosul. |

|

He was the brother of ] and Diyā' ad-Dīn Ibn Athir. Al-Athir lived a scholarly life in ], often visited ] and for a time traveled with ]'s army in ]. He later lived in ] and ]. His chief work was a history of the world, ''al-Kamil fi at-Tarikh'' ('']''). |

|

|

|

|

|

== Death == |

|

|

{{Main|Tomb of the Girl}} |

|

|

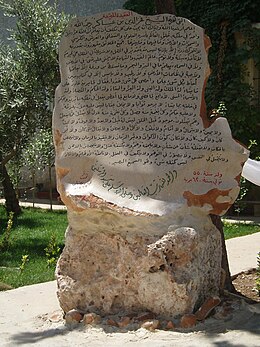

Ibn al-Athir died in 1232/1233, and was buried in a cemetery in Mosul, at the district of Bab Sinjar.<ref>{{Cite web |title=عز الدين بن الاثير وقبر البنت |url=https://omferas.com/vb/t38540/ |access-date=2023-11-21 |website=omferas.com}}</ref> His tomb was built in the 20th century and was located in the middle of a road, after the cemetery was cleared for modernization.<ref>{{Cite web |title=عز الدين بن الاثير وقبر البنت |url=https://omferas.com/vb/t38540/ |access-date=2023-11-21 |website=omferas.com}}</ref> It became a site of an erroneous legend, which identified it as a tomb of a female mystic.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-11-21 |title=قبر البنت في باب سنجارفي الموصل |url=https://baretly.net/index.php?PHPSESSID=9bdba34bed758e31a2b338760d263317&topic=30569.0 |access-date=2023-11-21 |website=منتديات برطلي |language=en-US}}</ref> However, the government later installed a marble ] to indicate that it was Ibn al-Athir's tomb.<ref>{{Cite web |title=الموصل بعد 150 عاماً ! |url=https://almadapaper.net//view.php?cat=109633 |access-date=2023-11-21 |website=almadapaper.net| date=20 July 2014 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=عز الدين بن الاثير وقبر البنت |url=https://omferas.com/vb/t38540/ |access-date=2023-11-21 |website=omferas.com}}</ref> His tomb was also regarded in local ] folklore as being the grave of a girl who married the ] but died of poisoning.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-11-21 |title=قبر البنت في باب سنجارفي الموصل |url=https://baretly.net/index.php?PHPSESSID=5f7b6b63bae02eaeac8b7830d9483e69&topic=30569.0 |access-date=2023-11-21 |website=منتديات برطلي |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

⚫ |

The tomb of Ibn al-Athir was bulldozed by members of the ] (ISIL) in June 2014.<ref>Isra' al-Rubei'i. "Iraqi forces ready push after Obama offers advisers." ''Reuters'', June 20, 2014.</ref> |

|

== Modern age == |

|

| ⚫ |

According to Reuters, his tomb was ] in Mosul by members of the ] offshoot the ] (ISIL) in June 2014.<ref>Isra' al-Rubei'i. "Iraqi forces ready push after Obama offers advisers." ''Reuters'', June 20, 2014.</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

|

== Works == |

|

== Works == |

| Line 51: |

Line 54: |

|

|

|

|

|

== External links == |

|

== External links == |

|

|

{{wikiquote}} |

|

{{wikisourcelang|ar|مؤلف:ابن الأثير|Ibn al-Athir}} |

|

{{wikisourcelang|ar|مؤلف:ابن الأثير|Ibn al-Athir}} |

|

* by William E. Watson from Canadian/American Slavic Studies |

|

* by William E. Watson from Canadian/American Slavic Studies |

| Line 67: |

Line 71: |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

| Line 76: |

Line 80: |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

] |

|

|

] |

Ibn al-Athir died in 1232/1233, and was buried in a cemetery in Mosul, at the district of Bab Sinjar. His tomb was built in the 20th century and was located in the middle of a road, after the cemetery was cleared for modernization. It became a site of an erroneous legend, which identified it as a tomb of a female mystic. However, the government later installed a marble stele to indicate that it was Ibn al-Athir's tomb. His tomb was also regarded in local Yazidi folklore as being the grave of a girl who married the Emir of Mosul but died of poisoning.