| Revision as of 22:03, 4 December 2009 editGabbe (talk | contribs)Administrators34,331 editsm Reverted edits by Pop don (talk) to last version by Nigelj← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:03, 26 December 2024 edit undoJJMC89 bot III (talk | contribs)Bots, Administrators3,732,146 editsm Moving Category:Treaties of East Timor to Category:Treaties of Timor-Leste per Misplaced Pages:Categories for discussion/Speedy | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1997 international treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{About|the international treaty|the rock band|Kyoto Protocol (band)}} | |||

| <noinclude>{{Infobox Treaty | |||

| | name = Kyoto Protocol | |||

| | long_name = Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC | |||

| | image = Kyoto Protocol parties.svg | |||

| | image_width = 355 | |||

| | caption ={{legend|#008000|Annex B parties with binding targets in the second period}} {{legend|purple|Annex B parties with binding targets in the first period but not the second}} {{legend|#0000FF|Non-Annex B parties without binding targets}} {{legend|#EEEE00|Annex B parties with binding targets in the first period but which withdrew from the Protocol}} {{legend|orange|Signatories to the Protocol that have not ratified}} {{legend|#FF1111|Other UN member states and observers that are not party to the Protocol}} | |||

| | date_drafted = | |||

| | date_signed = {{dts|11 December 1997}}<ref name=parties/> | |||

| | location_signed = ], ] | |||

| | date_sealed = | |||

| | date_effective = 16 February 2005<ref name=parties/> | |||

| | condition_effective = Ratification by at least 55 states to the Convention | |||

| | date_expiration = 31 December 2012 (first commitment period)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf|title=Kyoto Protocol on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change|publisher=United Nations|access-date=17 November 2004|archive-date=5 October 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111005085911/http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref><br />31 December 2020 (second commitment period)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol|title=What is the Kyoto Protocol?|publisher=UNFCCC|access-date=31 May 2021|archive-date=13 December 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231213141052/https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | signatories = 84<ref name=parties/> (1998–1999 signing period) | |||

| | parties = ]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://unfccc.int/process/the-kyoto-protocol/status-of-ratification |title=Status of Ratification |publisher=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |website=unfccc.int |access-date=28 February 2020 |archive-date=5 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200905124014/http://unfccc.int/process/the-kyoto-protocol/status-of-ratification |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=UNlist/> (the European Union, Cook Islands, Niue, and all ] except Andorra, Canada, South Sudan, and the United States as of 2022) | |||

| | depositor = ] | |||

| | language = | |||

| | languages = Arabic, Mandarin, English, French, Russian, and Spanish | |||

| | website = | |||

| | wikisource = Kyoto Protocol | |||

| }}</noinclude> | |||

| <noinclude>{{Infobox Treaty | |||

| | name = Kyoto Protocol Extension (2012–2020) | |||

| | long_name = Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol | |||

| | type = Amendment to international agreement | |||

| | image = Doha Amendment of Kyoto.svg | |||

| | image_width = 350 | |||

| | caption = Acceptance of the Doha Amendment | |||

| {{legend|#32CD32|States that ratified}} | |||

| {{legend|#b9b9b9|Kyoto protocol parties that did not ratify}} | |||

| {{legend|#e9e9e9|Non-parties to the Kyoto Protocol}} | |||

| | date_drafted = 8 December 2012 | |||

| | location_signed = ], ] | |||

| | date_sealed = | |||

| | date_effective = 31 December 2020<ref name=DOHARAT/> | |||

| | condition_effective = Ratification by 144 state parties required | |||

| | date_expiration = 31 December 2020<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/10/02/nigeria-jamaica-bring-closure-kyoto-protocol-era-last-minute-dash/|title=Nigeria, Jamaica bring closure to the Kyoto Protocol era, in last-minute dash|publisher=Climate Change News|date=2 October 2020|access-date=31 May 2021|archive-date=6 April 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230406105609/https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/10/02/nigeria-jamaica-bring-closure-kyoto-protocol-era-last-minute-dash/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | signatories = <!--there is only ratification/acception...--> | |||

| | ratifiers = 147<ref name=DOHARAT>{{cite web|url=https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-c&chapter=27&clang=_en|title=7 .c Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol|work=UN Treaty Database|access-date=19 April 2015|archive-date=4 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204160337/https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-c&chapter=27&clang=_en|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | depositor = | |||

| | language = | |||

| | languages = | |||

| | website = | |||

| | wikisource = Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol | |||

| }}</noinclude> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2020}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The {{nihongo|'''Kyoto Protocol'''|京都議定書|Kyōto Giteisho|lead=yes}} was an ] which extended the 1992 ] (UNFCCC) that commits state parties to reduce ], based on the ] that ] is occurring and that human-made ] are driving it. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in ], Japan, on 11 December 1997 and entered into force on 16 February 2005. There were 192 parties (] withdrew from the protocol, effective December 2012)<ref name=UNlist>{{cite web |url=https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-a&chapter=27&lang=en |title=7 .a Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |work=UN Treaty Database |access-date=27 November 2014 |archive-date=8 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181008095709/https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-a&chapter=27&lang=en |url-status=dead }}</ref> to the Protocol in 2020. | |||

| The Kyoto Protocol implemented the objective of the UNFCCC to reduce the onset of global warming by reducing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere to "a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system" (Article 2). The Kyoto Protocol applied to the seven greenhouse gases listed in Annex A: ], ], ], ]s (HFCs), ] (PFCs), ], ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://naei.beis.gov.uk/overview/ghg-overview.php|title=Overview of greenhouse gases - Defra, UK|website=Naei.beis.gov.uk|access-date=2 March 2022|archive-date=23 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123114338/https://naei.beis.gov.uk/overview/ghg-overview.php|url-status=live}}</ref> Nitrogen trifluoride was added for the second compliance period during the Doha Round.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://unfccc.int/files/kyoto_protocol/application/pdf/kp_doha_amendment_english.pdf|title=Doha amendment to the Kyoto Protocol|website=Unfcc.int|access-date=2 March 2022|archive-date=24 December 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221224054705/http://unfccc.int/files/kyoto_protocol/application/pdf/kp_doha_amendment_english.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Kyoto Protocol''' is a ] to the ] (UNFCCC or FCCC), aimed at combating ]. The UNFCCC is an international ] ] with the goal of achieving "stabilization of ] concentrations in the ] at a level that would prevent ] with the climate system."<ref name="unfccc2005">{{cite web | title=Article 2| work=The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change | url=http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/1353.php | dateformat=dmy | accessdate=15 November 2005 }}</ref> | |||

| The Protocol was based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities: it acknowledged that individual countries have different capabilities in combating climate change, owing to ], and therefore placed the obligation to reduce current emissions on developed countries on the basis that they are historically responsible for the current levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. | |||

| The Protocol was initially adopted on 11 December 1997 in ], ] and entered into force on 16 February 2005. As of November 2009, ] the protocol.<ref name = "Kyoto-PDF-unfccc">{{cite web | title=Kyoto Protocol: Status of Ratification | url=http://unfccc.int/files/kyoto_protocol/status_of_ratification/application/pdf/kp_ratification.pdf | date=2009-01-14 | accessdate=2009-05-06 | publisher=] |format=PDF}}</ref> The most notable non-member of the Protocol is the ], which is a signatory of UNFCCC and was responsible for 36.1% of the 1990 emission levels. | |||

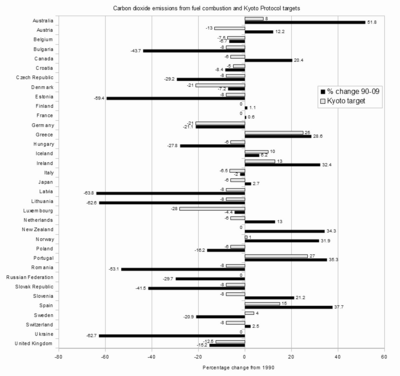

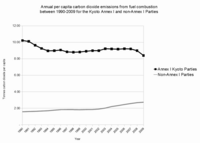

| The Protocol's first commitment period started in 2008 and ended in 2012. All 36 countries that fully participated in the first commitment period complied with the Protocol. However, nine countries had to resort to the flexibility mechanisms by funding emission reductions in other countries because their national emissions were slightly greater than their targets. The ] reduced emissions. The greatest emission reductions were seen in the former ] countries because the ] reduced their emissions in the early 1990s.<ref name="Shislov">{{cite journal |last1=Shishlov |first1=Igor |last2=Morel |first2=Romain |last3=Bellassen |first3=Valentin |date=2016 |title=Compliance of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol in the first commitment period |journal=Climate Policy |volume=16 |issue=6 |pages=768–782 |doi=10.1080/14693062.2016.1164658 |bibcode=2016CliPo..16..768S |s2cid=156120010 |url=https://hal-enpc.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01425106/file/2016%20-%20Shishlov%20et%20al%20-%20Climate%20Policy%20-%20Compliance%20of%20the%20Parties%20to%20the%20Kyoto%20Protocol%20in%20the%20first%20commitment%20period_preprint.pdf |access-date=5 September 2021 |archive-date=23 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123111240/https://hal-enpc.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01425106/file/2016%20-%20Shishlov%20et%20al%20-%20Climate%20Policy%20-%20Compliance%20of%20the%20Parties%20to%20the%20Kyoto%20Protocol%20in%20the%20first%20commitment%20period_preprint.pdf |url-status=live | issn=1469-3062 }}</ref> Even though the 36 developed countries reduced their emissions, the global emissions increased by 32% from 1990 to 2010.<ref name="GapReport">{{cite web |url=http://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/8526/-The%20emissions%20gap%20report%202012_%20a%20UNEP%20synthesis%20reportemissionGapReport2012.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y |title=The Emissions Gap Report 2012 |date=2012 |publisher=United Nations Environment Programme |page=2 |access-date=2019-12-07 |archive-date=23 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123114216/https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/8526/-The%20emissions%20gap%20report%202012_%20a%20UNEP%20synthesis%20reportemissionGapReport2012.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Under the Protocol, 37 industrialized countries (called "]") commit themselves to a reduction of four greenhouse gases (GHG) (], ], ], ]) and two groups of gases (]s and ]s) produced by them, and all member countries give general commitments. Annex I countries agreed to reduce their collective greenhouse gas emissions by 5.2% from the 1990 level. Emission limits do not include emissions by international aviation and shipping, but are in addition to the industrial gases, chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, which are dealt with under the 1987 ]. | |||

| A second commitment period was agreed to in 2012 to extend the agreement to 2020, known as the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, in which 37 countries had binding targets: ], the ] (and its then 28 ], now 27), ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine stated that they may withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol or not put into legal force the Amendment with second round targets.<ref name="figueres doha summary">{{citation | last=Figueres | first=C. | title=Environmental issues: Time to abandon blame-games and become proactive - Economic Times | work=The Economic Times / Indiatimes.com | publisher=Times Internet | url=http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-12-15/news/35836633_1_emission-reduction-targets-global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-climate-change | date=15 December 2012 | access-date=2012-12-18 | archive-date=23 January 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123111242/http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-12-15/news/35836633_1_emission-reduction-targets-global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-climate-change | url-status=dead }}</ref> Japan, ], and ] had participated in Kyoto's first-round but did not take on new targets in the second commitment period. Other developed countries without second-round targets were Canada (which withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2012) and the ] (which did not ratify). If they were to remain as a part of the protocol, Canada would be hit with a $14 billion fine, which would be devastating to their economy, hence the reluctant decision to exit.<ref>{{cite news |first1= |date=December 12, 2011 |title=Canada pulls out of Kyoto Protocol |work=CBC News |url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-pulls-out-of-kyoto-protocol-1.999072 |access-date=11 January 2023 |archive-date=11 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230111115157/https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-pulls-out-of-kyoto-protocol-1.999072 |url-status=live }}</ref> As of October 2020, 147<ref name=DOHARAT/><ref>{{cite web|title=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change|url=http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/doha_amendment/items/7362.php|website=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change|access-date=23 July 2016|ref=66|archive-date=8 December 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221208170819/https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/doha_amendment/items/7362.php|url-status=live}}</ref> states had accepted the Doha Amendment. It entered into force on 31 December 2020, following its acceptance by the mandated minimum of at least 144 states, although the second commitment period ended on the same day. Of the 37 parties with binding commitments, 34 had ratified. | |||

| The benchmark 1990 emission levels were accepted by the Conference of the Parties of UNFCCC (decision 2/CP.3) were the values of "]" calculated for the ]. These figures are used for converting the various greenhouse gas emissions into comparable ] when computing overall sources and sinks. | |||

| Negotiations were held in the framework of the yearly UNFCCC Climate Change Conferences on measures to be taken after the second commitment period ended in 2020. This resulted in the 2015 adoption of the ], which is a separate instrument under the UNFCCC rather than an amendment of the Kyoto Protocol. | |||

| The Protocol allows for several "]", such as ], the ] (CDM) and ] to allow ] to meet their GHG emission limitations by purchasing GHG emission reductions credits from elsewhere, through financial exchanges, projects that reduce emissions in non-Annex I countries, from other Annex I countries, or from annex I countries with excess allowances. | |||

| == Chronology == | |||

| Each Annex I country is required to submit an annual report of inventories of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions from sources and removals from sinks under UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol. These countries nominate a person (called a "designated national authority") to create and manage its ]. Countries including ], ], ], the ], ], ], ] and others are actively promoting government ]s, supporting multilateral carbon funds intent on purchasing ]s from non-Annex I countries,<ref>, International Rivers, published November 2008, accessed 9 July 2009</ref> and are working closely with their major utility, energy, oil and gas and chemicals conglomerates to acquire ]s as cheaply as possible.{{Citation needed|date=October 2008}} Virtually all of the non-Annex I countries have also established a designated national authority to manage its Kyoto obligations, specifically the "CDM process" that determines which GHG projects they wish to propose for accreditation by the CDM Executive Board. | |||

| {{See also|History of climate change policy and politics|United Nations Climate Change Conference}} | |||

| '''1992''' – The UN Conference on the Environment and Development is held in Rio de Janeiro. It results in the ] (UNFCCC) among other agreements. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| The prevailing international ] is that human activities resulted in substantial global warming from the mid-20th century, and that continued growth in greenhouse gas concentrations caused by human-induced emissions would generate high risks of dangerous climate change. | |||

| '''1995''' – Parties to the UNFCCC meet in Berlin (the 1st Conference of Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC) to outline specific targets on emissions. | |||

| The ] (IPCC) has predicted an average global rise in ] of 1.4°] (2.5°]) to 5.8°C (10.4°]) between 1990 and 2100.<ref>{{cite web | title=Executive Summary. Chapter 9: Projections of Future Climate Change | work=Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis | url=http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/339.htm | dateformat=dmy | accessdate=15 November 2005 }}</ref> | |||

| '''1997''' – In December the parties conclude the Kyoto Protocol in Kyoto, Japan, in which they agree to the broad outlines of emissions targets. | |||

| ==Ratification process== | |||

| '''2004''' – Russia and Canada ratify the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC bringing the treaty into effect on 16 February 2005. | |||

| {{Expand-section|date=May 2007}}<!--What does the protocol being "in force" entail?--> | |||

| '''2011''' – Canada became the first signatory to announce its withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ec.gc.ca/Publications/default.asp?lang=En&n=EE4F06AE-1&xml=EE4F06AE-13EF-453B-B633-FCB3BAECEB4F&offset=3&toc=show|title=A Climate Change Plan for the Purposes of the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act 2012: Canada's Withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol|date=11 February 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150211142508/http://www.ec.gc.ca/Publications/default.asp?lang=En&n=EE4F06AE-1&xml=EE4F06AE-13EF-453B-B633-FCB3BAECEB4F&offset=3&toc=show|archive-date=11 February 2015|access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> | |||

| The Protocol was adopted by ] on 11 December 1997 in ]. It was opened on 16 March 1998 for signature by parties to UNFCCC. | |||

| '''2012''' – On 31 December 2012, the first commitment period under the Protocol expired. | |||

| {{hidden begin | |||

| |title = Countries which are parties to UNFCCC | |||

| The official meeting of all states party to the Kyoto Protocol is the annual ] to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The first conference was held in 1995 in Berlin (]). The first Meeting of Parties of the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) was held in 2005 in conjunction with ]. | |||

| |titlestyle = background:#00FFFF; text-align:left; | |||

| |bodystyle = text-align:left; | |||

| ==Objectives== | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| |direction=vertical | |||

| | align=left | |||

| | image1= Major greenhouse gas trends.png | |||

| | alt1=Atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations | |||

| | image2= Stabilizing the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide at a constant level would require emissions to be effectively eliminated (vertical).png | |||

| | alt2=Refer to caption | |||

| | caption1=Kyoto is intended to cut ] emissions of ]es. | |||

| | caption2=In order to stabilize the atmospheric concentration of {{CO2}}, emissions worldwide would need to be dramatically reduced from their present level.<ref>{{cite book | year = 2009 | contribution = BOX NT.1 Summary of Climate Change Basics | title = Non-Technical Summary | series = Synthesis and Assessment Product 5.2: Best practice approaches for characterizing, communicating, and incorporating scientific uncertainty in decision making. A Report by the U.S. ] and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research | publisher = National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | location = Washington D.C., USA. | page = 11 | last1 = Granger Morgan * | first1 = M. | quote = (* is Lead Author) | first2 = H. | last2 = Dowlatabadi | first3 = M. | last3 = Henrion | first4 = D. | last4 = Keith | first5 = R. | last5 = Lempert | first6 = S. | last6 = McBride | first7 = M. | last7 = Small | first8 = T. | last8 = Wilbanks | url = http://www.globalchange.gov/publications/reports/scientific-assessments/saps/311 | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100527134225/http://www.globalchange.gov/publications/reports/scientific-assessments/saps/311 | archive-date = 27 May 2010 | df = dmy-all }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The main goal of the Kyoto Protocol was to control emissions of the main anthropogenic (human-emitted) greenhouse gases (GHGs) in ways that reflect underlying national differences in GHG emissions, wealth, and capacity to make the reductions.<ref name="2004 grubb kyoto"> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| |last = Grubb | |||

| |first = M. | |||

| |year = 2004 | |||

| |title = Kyoto and the Future of International Climate Change Responses: From Here to Where? | |||

| |journal = International Review for Environmental Strategies | |||

| |volume = 5 | |||

| |issue = 1 | |||

| |page = 2 (PDF version) | |||

| |url = http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/rstaff/grubb/publications/J37.pdf | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120111215457/http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/rstaff/grubb/publications/J37.pdf | |||

| |archive-date = 11 January 2012 | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> The treaty follows the main principles agreed in the original 1992 UN Framework Convention.<ref name="2004 grubb kyoto"/> According to the treaty, in 2012, Annex I Parties who have ratified the treaty must have fulfilled their obligations of greenhouse gas emissions limitations established for the Kyoto Protocol's first commitment period (2008–2012). These emissions limitation commitments are listed in Annex B of the Protocol. | |||

| The Kyoto Protocol's first round commitments are the first detailed step taken within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.<ref name=gupta/> The Protocol establishes a structure of rolling emission reduction commitment periods. It set a timetable starting in 2006 for negotiations to establish emission reduction commitments for a second commitment period.<ref name="grubb commitments">{{harvnb|Grubb|Depledge|2001|p=269}}</ref> The first period emission reduction commitments expired on 31 December 2012. | |||

| The first-round Kyoto emissions limitation commitments were not sufficient to stabilize the atmospheric concentration of GHGs. Stabilization of atmospheric GHG concentrations will require further emissions reductions after the end of the first-round Kyoto commitment period in 2012.<ref name="grubb commitments" /><ref name="ipcc kyoto stabilization"> | |||

| {{citation |title=Stabilizing atmospheric concentrations would depend upon emissions reductions beyond those agreed to in the Kyoto Protocol |df=dmy-all |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121030105841/http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/vol4/english/058.htm |chapter=Question 7 |chapter-url=http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/vol4/english/058.htm |archive-date=30 October 2012}} | |||

| , p.122, in {{harvnb|IPCC TAR SYR|2001}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| The ultimate objective of the UNFCCC is the "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would stop dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system."<ref name="unfccc2005">{{cite web | |||

| |title=Article 2 | |||

| |work=The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. | |||

| |quote=Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner | |||

| |url=http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/1353.php | |||

| |access-date=15 November 2005 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051028023600/http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/1353.php | |||

| |archive-date= 28 October 2005 | |||

| }}</ref> Even if Annex I Parties succeed in meeting their first-round commitments, much greater emission reductions will be required in future to stabilize atmospheric GHG concentrations.<ref name="grubb commitments"/><ref name="ipcc kyoto stabilization"/> | |||

| For each of the different anthropogenic GHGs, different levels of emissions reductions would be required to meet the objective of ].<ref name="2007 meehl stabilizing atmospheric concentrations of GHGs">{{cite book | |||

| |year = 2007 | |||

| |contribution = FAQ 10.3 If Emissions of Greenhouse Gases are Reduced, How Quickly do Their Concentrations in the Atmosphere Decrease? | |||

| |url = http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/faq-10-3.html | |||

| |last = Meehl | |||

| |first = G. A. | |||

| |title = Global Climate Projections | |||

| |series = Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change | |||

| |editor = Solomon, S. | |||

| |display-editors = etal | |||

| |publisher = Cambridge University Press | |||

| |display-authors = etal | |||

| |access-date = 26 December 2011 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111224051815/http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/faq-10-3.html | |||

| |archive-date = 24 December 2011 | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }}</ref> ] ({{CO2}}) is the most important anthropogenic GHG.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | year=2007 | |||

| | contribution=Human and Natural Drivers of Climate Change | |||

| | url=http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/spmsspm-human-and.html | |||

| | author=Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) | |||

| | title=Summary for Policymakers | |||

| | series=Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC | |||

| | editor=Solomon, S. | |||

| | publisher=Cambridge University Press | |||

| | display-editors=etal | |||

| | access-date=26 December 2011 | |||

| | archive-date=2 November 2018 | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181102212113/http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/spmsspm-human-and.html | |||

| | url-status=dead | |||

| }}</ref> Stabilizing the concentration of {{CO2}} in the atmosphere would ultimately require the effective elimination of anthropogenic {{CO2}} emissions.<ref name="2007 meehl stabilizing atmospheric concentrations of GHGs"/> | |||

| To achieve stabilization, global GHG emissions must peak, then decline.<ref name="emissions peak and decline">{{citation |title=5.4 Emission trajectories for stabilisation |df=dmy-all |access-date=17 July 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141127224337/http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/syr/en/mains5-4.html |url-status=dead |chapter=Synthesis report |chapter-url=http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/syr/en/mains5-4.html |archive-date=27 November 2014}} | |||

| , in {{harvnb|IPCC AR4 SYR|2007}}</ref> The lower the desired stabilization level, the sooner this peak and decline must occur.<ref name="emissions peak and decline" /> For a given stabilization level, larger emissions reductions in the near term allow for less stringent emissions reductions later.<ref name="near term emissions reductions"> | |||

| {{citation |title=Sec 8.5 Pathways to stabilisation |df=dmy-all |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121006161506/http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/Chapter_8_The_Challenge_of_Stabilisation.pdf |url-status=dead |chapter=Chapter 8 The challenge of stabilisation |chapter-url=http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/Chapter_8_The_Challenge_of_Stabilisation.pdf |archive-date=6 October 2012}}, in {{harvnb|Stern|2006|p=199}} | |||

| </ref> On the other hand, less stringent near term emissions reductions would, for a given stabilization level, require more stringent emissions reductions later on.<ref name="near term emissions reductions" /> | |||

| The first period Kyoto emissions limitations can be viewed as a first-step towards achieving atmospheric stabilization of GHGs.<ref name="gupta" /> In this sense, the first period Kyoto commitments may affect what future atmospheric stabilization level can be achieved.<ref>{{citation |last=Höhne |first=N. |title=Impact of the Kyoto Protocol on Stabilization of Carbon Dioxide Concentration |url=http://stabilisation.metoffice.com/posters/Hohne_Niklas.pdf |location=Cologne, Germany |publisher=ECOFYS energy & environment |access-date=17 July 2012 |archive-date=13 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200113095438/http://stabilisation.metoffice.com/posters/Hohne_Niklas.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Principal concepts == | |||

| Some of the principal concepts of the Kyoto Protocol are: | |||

| * Binding commitments for the Annex I Parties. The main feature of the Protocol<ref name="2011 unfccc kyoto protocol overview">{{citation | |||

| | year=2011 | |||

| | author=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) | |||

| | title=Kyoto Protocol | |||

| | publisher=UNFCCC | |||

| | url=http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php | |||

| | access-date=30 December 2011 | |||

| | archive-date=16 May 2011 | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110516211124/http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php | |||

| | url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> is that it established legally binding commitments to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases for Annex I Parties. The commitments were based on the Berlin Mandate, which was a part of UNFCCC negotiations leading up to the Protocol.{{sfn|Depledge|2000|p=6}}<ref name="liverman">{{cite journal |last=Liverman |first=D. M. |year=2008 |title=Conventions of climate change: constructions of danger and the dispossession of the atmosphere |url=http://www.environment.arizona.edu/files/env/profiles/liverman/liverman-2009-jhg.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=Journal of Historical Geography |volume=35 |issue=2 |pages=279–296 |doi=10.1016/j.jhg.2008.08.008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140912161138/http://www.environment.arizona.edu/files/env/profiles/liverman/liverman-2009-jhg.pdf |archive-date=12 September 2014 |access-date=10 May 2011 |df=dmy-all}}</ref>{{Rp|290|date=November 2012}} | |||

| * Implementation. In order to meet the objectives of the Protocol, Annex I Parties are required to prepare policies and measures for the reduction of greenhouse gases in their respective countries. In addition, they are required to increase the absorption of these gases and utilize all mechanisms available, such as joint implementation, the clean development mechanism and emissions trading, in order to be rewarded with credits that would allow more greenhouse gas emissions at home. | |||

| * Minimizing Impacts on Developing Countries by establishing an ] fund for climate change. | |||

| * Accounting, Reporting and Review in order to ensure the integrity of the Protocol. | |||

| * Compliance. Establishing a Compliance Committee to enforce compliance with the commitments under the Protocol. | |||

| === Flexibility mechanisms === | |||

| The Protocol defines three "]" that can be used by Annex I Parties in meeting their emission limitation commitments.<ref> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |chapter-url = http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/225.htm | |||

| |title = Executive summary | |||

| |chapter = Measures, and Instruments | |||

| |last1 = Bashmakov | |||

| |first1 = I. | |||

| |display-authors = etal | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120117023130/http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/225.htm | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| |archive-date = 17 January 2012 | |||

| }}, in {{harvnb|IPCC TAR WG3|2001}} | |||

| </ref>{{Rp|402|date=November 2012}} The flexibility mechanisms are International Emissions Trading (IET), the ] (CDM), and ] (JI). IET allows Annex I Parties to "trade" their emissions (], AAUs, or "allowances" for short).<ref>Clifford Chance LLP (2012). "Clean Development Mechanism: CDM and the UNFCC" {{cite web |url=http://a4id.org/sites/default/files/user/CDM%26UNFCCCcorrected.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=2013-09-19 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130921060112/http://a4id.org/sites/default/files/user/CDM%26UNFCCCcorrected.pdf |archive-date=21 September 2013 |df=dmy-all }}. Advocates for International Development. Retrieved: 19 September 2013.</ref> | |||

| The economic basis for providing this flexibility is that the ] cost of reducing (or abating) emissions differs among countries.<ref name="toth 2001 flexibility mechanisms"> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |chapter-url = http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/441.htm | |||

| |title = 10.4.4. Where Should the Response Take Place? The Relationship between Domestic Mitigation and the Use of International Mechanisms | |||

| |chapter = 10. Decision-making Frameworks | |||

| |last1 = Toth | |||

| |first1 = F. L. | |||

| |display-authors = etal | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120117032405/http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/441.htm | |||

| |archive-date = 17 January 2012 | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }}, in {{harvnb|IPCC TAR WG3|2001}} | |||

| </ref>{{Rp|660|date=November 2012}}<ref> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |chapter-url = http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/246.htm | |||

| |title = 6.3 International Policies, Measures, and Instruments | |||

| |chapter = 6. Policies, Measures, and Instruments | |||

| |last1 = Bashmakov | |||

| |first1 = I. | |||

| |display-authors = etal | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090805204450/http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar///wg3/246.htm | |||

| |archive-date = 5 August 2009 | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }}, in {{harvnb|IPCC TAR WG3|2001}} | |||

| </ref> "Marginal cost" is the cost of abating the last tonne of {{CO2}}-eq for an Annex I/non-Annex I Party. At the time of the original Kyoto targets, studies suggested that the flexibility mechanisms could reduce the overall (]) cost of meeting the targets.<ref name="hourcade 2001 economic costs of flexibility mechanisms"> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |chapter-url = http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/341.htm | |||

| |title = 8.3.1 International Emissions Quota Trading Regimes | |||

| |chapter = 8. Global, Regional, and National Costs and Ancillary Benefits of Mitigation | |||

| |last1 = Hourcade | |||

| |first1 = J.-C. | |||

| |display-authors = etal | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120111150919/http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/341.htm | |||

| |archive-date = 11 January 2012 | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }}, in {{harvnb|IPCC TAR WG3|2001}} | |||

| </ref> Studies also showed that national losses in Annex I ] (GDP) could be reduced by the use of the flexibility mechanisms.<ref name="hourcade 2001 economic costs of flexibility mechanisms" /> | |||

| The CDM and JI are called "project-based mechanisms", in that they generate emission reductions from projects. The difference between IET and the project-based mechanisms is that IET is based on the setting of a quantitative restriction of emissions, while the CDM and JI are based on the idea of "production" of emission reductions.<ref name="toth 2001 flexibility mechanisms" /> The CDM is designed to encourage production of emission reductions in non-Annex I Parties, while JI encourages production of emission reductions in Annex I Parties. | |||

| The production of emission reductions generated by the CDM and JI can be used by Annex I Parties in meeting their emission limitation commitments.<ref> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |chapter-url = http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/247.htm | |||

| |title = 6.3.2 Project-based Mechanisms (Joint Implementation and the Clean Development Mechanism) | |||

| |chapter = 6. Policies, Measures, and Instruments | |||

| |last1 = Bashmakov | |||

| |first1 = I. | |||

| |display-authors = etal | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120113181950/http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/247.htm | |||

| |archive-date = 13 January 2012 | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }}, in {{harvnb|IPCC TAR WG3|2001}} | |||

| </ref> The emission reductions produced by the CDM and JI are both measured against a hypothetical ] of emissions that would have occurred in the absence of a particular emission reduction project. The emission reductions produced by the CDM are called ]s (CERs); reductions produced by JI are called ]s (ERUs). The reductions are called "]" because they are emission reductions credited against a hypothetical baseline of emissions.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Fernandez Quesada|first=Nicolas|title=Kyoto Protocol, Emissions Trading and Reduction Technologies for Climate Change Mitigation|date=2013|publisher=GRIN Verlag GmbH|isbn=978-3-656-47173-8|location=Munich|oclc=862560217}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2lqtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA14 |title=International Conventions on Atmosphere Handbook|publisher=International Business Publications, USA|isbn=9781433066290|pages=14|date=3 March 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Only emission reduction projects that do not involve using nuclear energy are eligible for accreditation under the CDM, in order to prevent nuclear technology exports from becoming the default route for obtaining credits under the CDM. | |||

| Each Annex I country is required to submit an annual report of inventories of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions from sources and removals from sinks under UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol. These countries nominate a person (called a "designated national authority") to create and manage its ]. Virtually all of the non-Annex I countries have also established a designated national authority to manage their Kyoto obligations, specifically the "CDM process". This determines which GHG projects they wish to propose for accreditation by the CDM Executive Board. | |||

| ==== International emissions trading ==== | |||

| {{excerpt|Carbon emission trading}} | |||

| ===== Intergovernmental emissions trading ===== | |||

| The design of the ] (EU ETS) implicitly allows for trade of national Kyoto obligations to occur between participating countries.{{sfn|Carbon Trust|2009|p=24}} The Carbon Trust found that other than the trading that occurs as part of the EU ETS, no intergovernmental emissions trading had taken place.{{sfn|Carbon Trust|2009|pp=24–25}} | |||

| One of the environmental problems with IET is the large surplus of allowances that are available. Russia, Ukraine, and the new EU-12 member states (the Kyoto Parties Annex I Economies-in-Transition, abbreviated "EIT": Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine)<ref>{{citation | |||

| |title=Development and Climate Change: A Strategic Framework for the World Bank Group: Technical Report | |||

| |year=2008 | |||

| |author=World Bank | |||

| |url=http://beta.worldbank.org/overview/strategic-framework-development-and-climate-change | |||

| |publisher=The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. | |||

| |location=Washington, DC, USA | |||

| |access-date=3 April 2010 | |||

| |archive-date=24 December 2009 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091224213652/http://beta.worldbank.org/overview/strategic-framework-development-and-climate-change | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| }}</ref>{{Rp|59|date=November 2012}} have a surplus of allowances, while many ] countries have a deficit.{{sfn|Carbon Trust|2009|p=24}} Some of the EITs with a surplus regard it as potential compensation for the trauma of their economic restructuring.{{sfn|Carbon Trust|2009|p=25}} When the Kyoto treaty was negotiated, it was recognized that emissions targets for the EITs might lead to them having an excess number of allowances.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |year = 2001 | |||

| |contribution = 8.3.1.1 "Where Flexibility" | |||

| |title = 8. Global, Regional, and National Costs and Ancillary Benefits of Mitigation | |||

| |page = 538 | |||

| |series = Climate Change 2001: Mitigation. A Contribution of Working Group III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change | |||

| |editor = B. Metz | |||

| |display-editors = etal | |||

| |publisher = Cambridge University Press | |||

| |last1 = Hourcade | |||

| |first1 = J.-C. | |||

| |url = http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/341.htm | |||

| |display-authors = etal | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120111150919/http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg3/341.htm | |||

| |archive-date = 11 January 2012 | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> This excess of allowances were viewed by the EITs as "headroom" to grow their economies.<ref>{{citation | |||

| | year=2003 | |||

| | title=Green Investment Schemes: Options and Issues | |||

| | last1=Blyth | |||

| | first1=W. | |||

| | first2=R. | |||

| | last2=Baron | |||

| | page=11 | |||

| | publisher=Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Environment Directorate and International Energy Agency (IEA) | |||

| | location=Paris, France | |||

| | url=http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/48/54/19842798.pdf | |||

| | access-date=16 December 2011 | |||

| | archive-date=22 December 2011 | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111222054248/http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/48/54/19842798.pdf | |||

| | url-status=live | |||

| }} OECD reference: COM/ENV/EPOC/IEA/SLT(2003)9</ref> The surplus has, however, also been referred to by some as "hot air", a term which Russia (a country with an estimated surplus of 3.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent allowances) views as "quite offensive".<ref> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |date = 30 June 2008 | |||

| |title = Energy and Climate Change in Russia (note requested by the European Parliament's temporary committee on Climate Change, Policy Department Economy and Science, DG Internal Policies, European Parliament) | |||

| |last1 = Chiavari | |||

| |first1 = J. | |||

| |first2 = M. | |||

| |last2 = Pallemaerts | |||

| |page = 11 | |||

| |publisher = Institute for European Environmental Policy | |||

| |location = Brussels, Belgium | |||

| |url = http://www.ieep.eu/assets/433/ecc_russia.pdf | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111222054254/http://www.ieep.eu/assets/433/ecc_russia.pdf | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-date = 22 December 2011 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| OECD countries with a deficit could meet their Kyoto commitments by buying allowances from transition countries with a surplus. Unless other commitments were made to reduce the total surplus in allowances, such trade would not actually result in emissions being reduced{{sfn|Carbon Trust|2009|p=25}} (see also the section below on the ]). | |||

| ===== "Green Investment Schemes" ===== | |||

| The "Green Investment Scheme" (GIS) is a plan for achieving environmental benefits from trading surplus allowances (AAUs) under the Kyoto Protocol.<ref name="Definition of Green Investment Scheme (GIS)">{{citation | |||

| | year=2011 | |||

| | title=Carbon Finance - Glossary of Terms: Definition of "Green Investment Scheme" (GIS) | |||

| | author=Carbon Finance at the World Bank | |||

| | publisher=World Bank Carbon Finance Unit (CFU) | |||

| | location=Washington, DC, US | |||

| | url=http://go.worldbank.org/HZGVW3QN20 | |||

| | archive-url=http://webarchive.loc.gov/all/20100817010146/http://go.worldbank.org/HZGVW3QN20 | |||

| | url-status=dead | |||

| | archive-date=17 August 2010 | |||

| | access-date=15 December 2011 | |||

| }}</ref> The Green Investment Scheme (GIS), a mechanism in the framework of International Emissions Trading (IET), is designed to achieve greater flexibility in reaching the targets of the Kyoto Protocol while preserving environmental integrity of IET. However, using the GIS is not required under the Kyoto Protocol, and there is no official definition of the term.<ref name="Definition of Green Investment Scheme (GIS)" /> | |||

| Under the GIS a party to the protocol expecting that the development of its economy will not exhaust its Kyoto quota, can sell the excess of its Kyoto quota units (AAUs) to another party. The proceeds from the AAU sales should be "greened", i.e. channelled to the development and implementation of the projects either acquiring the greenhouse gases emission reductions (hard greening) or building up the necessary framework for this process (soft greening).{{sfn|Carbon Trust|2009|p=25}} | |||

| ===== Trade in AAUs ===== | |||

| Latvia was one of the front-runners of GISs. World Bank (2011)<ref name="world bank 2011 trade in aaus">{{citation | |||

| | year=2011 | |||

| | author=World Bank | |||

| | title=State and Trends of the Carbon Market Report 2011 | |||

| | url=http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCARBONFINANCE/Resources/State_and_Trends_Updated_June_2011.pdf | |||

| | publisher=World Bank Environment Department, Carbon Finance Unit | |||

| | location=Washington, DC, USA | |||

| | access-date=26 January 2012 | |||

| | archive-date=25 March 2020 | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200325045048/http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCARBONFINANCE/Resources/State_and_Trends_Updated_June_2011.pdf | |||

| | url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref>{{Rp|53|date=November 2012}} reported that Latvia has stopped offering AAU sales because of low AAU prices. In 2010, Estonia was the preferred source for AAU buyers, followed by the Czech Republic and Poland.<ref name="world bank 2011 trade in aaus" />{{Rp|53|date=November 2012}} | |||

| Japan's national policy to meet their Kyoto target includes the purchase of AAUs sold under GISs.<ref>{{citation | |||

| | date=28 March 2008 | |||

| | author=Government of Japan | |||

| | title=Kyoto Protocol Target Achievement Plan (Provisional Translation) | |||

| | url=http://www.env.go.jp/en/earth/cc/kptap.pdf | |||

| | publisher=Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan | |||

| | location=Tokyo, Japan | |||

| | pages=81–82 | |||

| | access-date=26 January 2012 | |||

| | archive-date=20 April 2012 | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120420003913/https://www.env.go.jp/en/earth/cc/kptap.pdf | |||

| | url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> In 2010, Japan and Japanese firms were the main buyers of AAUs.<ref name="world bank 2011 trade in aaus" />{{Rp|53|date=November 2012}} In terms of the international carbon market, trade in AAUs are a small proportion of overall market value.<ref name="world bank 2011 trade in aaus" />{{Rp|9|date=November 2012}} In 2010, 97% of trade in the international carbon market was driven by the ] (EU ETS).<ref name="world bank 2011 trade in aaus" />{{Rp|9|date=November 2012}} | |||

| ===== Clean Development Mechanism ===== | |||

| Between 2001, which was the first year ] (CDM) projects could be registered, and 2012, the end of the first Kyoto commitment period, the CDM is expected to produce some 1.5 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO<sub>2</sub>e) in emission reductions.{{sfn|World Bank|2010}} Most of these reductions are through ], ], and fuel switching (World Bank, 2010, p. 262). By 2012, the largest potential for production of CERs are estimated in ] (52% of total CERs) and India (16%). CERs produced in Latin America and the Caribbean make up 15% of the potential total, with Brazil as the largest producer in the region (7%). | |||

| ===== Joint Implementation ===== | |||

| The formal crediting period for ] (JI) was aligned with the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, and did not start until January 2008 (Carbon Trust, 2009, p. 20).{{sfn|Carbon Trust|2009}} In November 2008, only 22 JI projects had been officially approved and registered. The total projected emission savings from JI by 2012 are about one tenth that of the CDM. Russia accounts for about two-thirds of these savings, with the remainder divided up roughly equally between Ukraine and the EU's New Member States. Emission savings include cuts in methane, HFC, and N<sub>2</sub>O emissions. | |||

| ==Details of the agreement== | |||

| The agreement is a protocol to the ] (UNFCCC) adopted at the ] in ] in 1992, which did not set any legally binding limitations on emissions or enforcement mechanisms. Only Parties to the UNFCCC can become Parties to the Kyoto Protocol. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted at the third session of the Conference of Parties to the UNFCCC in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan. | |||

| National emission targets specified in the Kyoto Protocol exclude international aviation and shipping. Kyoto Parties can use ], ], and ] (LULUCF) in meeting their targets.<ref name="Dessai 2001 3">{{harvnb|Dessai|2001|p=3}}</ref> LULUCF activities are also called "sink" activities. Changes in sinks and land use can have an effect on the climate,<ref>{{citation | |||

| |chapter-url = http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/syr/en/annexessglossary-j-p.html | |||

| |title = Glossary: Land use and Land-use change | |||

| |chapter = Annex II | |||

| |editor = Baede, A.P.M. | |||

| |access-date = 28 May 2010 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100501184723/http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/syr/en/annexessglossary-j-p.html | |||

| |archive-date = 1 May 2010 | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |df = dmy-all | |||

| }}, in {{harvnb|IPCC AR4 SYR|2007}}</ref> and indeed the ]'s Special Report on ] estimates that since 1750 a third of global warming has been caused by land use change.<ref>Robert T. Watson, Ian R. Noble, Bert Bolin, N. H. Ravindranath, David J. Verardo and David J. Dokken (editors), 2000, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry, Cambridge University Press, UK</ref> Particular criteria apply to the definition of forestry under the Kyoto Protocol. | |||

| ], ] management, ] land management, and ] are all eligible LULUCF activities under the Protocol.<ref name="forest management"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Dessai|2001|p=9}} | |||

| </ref> Annex I Parties use of forest management in meeting their targets is capped.<ref name="forest management" /> | |||

| === First commitment period: 2008–2012 === | |||

| Under the Kyoto Protocol, 37 ] and the ] (the ]-15, made up of 15 states at the time of the Kyoto negotiations) commit themselves to binding targets for GHG emissions.<ref name="2011 unfccc kyoto protocol overview" /> The targets apply to the four greenhouse gases ] ({{CO2}}), ] ({{chem2|CH4}}), ] ({{chem2|N2O}}), ] ({{chem2|SF6}}), and two groups of gases, ]s (HFCs) and ]s (PFCs).<ref name="grubb kyoto gases"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Grubb|2003|p=147}} | |||

| </ref> The six GHG are translated into ] in determining reductions in emissions.<ref>The benchmark 1990 emission levels accepted by the ] of UNFCCC (decision 2/CP.3) were the values of "]" calculated for the ]. These figures are used for converting the various greenhouse gas emissions into comparable ] (CO<sub>2</sub>-eq) when computing overall sources and sinks. Source: {{cite web |date=25 March 1998 |title=Methodological issues related to the Kyoto protocol |url=http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/cop3/07a01.pdf#page=31 |access-date=13 February 2010 |publisher=Report of the Conference of the Parties on its third session, held at Kyoto from 1 to 11 December 1997, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |archive-date=23 August 2000 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000823193833/http://www.unfccc.int/resource/docs/cop3/07a01.pdf#page=31 |url-status=live }}</ref> These reduction targets are in addition to the industrial gases, ]s, or CFCs, which are dealt with under the 1987 ]. | |||

| Under the Protocol, only the Annex I Parties have committed themselves to national or joint reduction targets (formally called "quantified emission limitation and reduction objectives" (QELRO) – Article 4.1).<ref name="unfccc1997">{{cite press release |url=http://unfccc.int/cop3/fccc/info/indust.htm |title=Industrialized countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 5.2% |publisher=] |date=11 December 1997 |access-date=6 August 2007 |archive-date=14 October 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071014231213/http://unfccc.int/cop3/fccc/info/indust.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> Parties to the Kyoto Protocol not listed in Annex I of the convention (the non-Annex I Parties) are mostly low-income developing countries,<ref name="2005 unfccc non-annex i summary" />{{Rp|4|date=November 2012}} and may participate in the Kyoto Protocol through the Clean Development Mechanism (explained below).<ref name="grubb commitments" /> | |||

| The emissions limitations of Annex I Parties varies between different Parties.<ref name="2011 unfccc kyoto protocol targets">{{cite web |title=Kyoto Protocol - Targets for the first commitment period |url=https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-kyoto-protocol/what-is-the-kyoto-protocol/kyoto-protocol-targets-for-the-first-commitment-period |access-date=28 January 2019 |publisher=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |archive-date=26 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230926060848/https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-kyoto-protocol/what-is-the-kyoto-protocol/kyoto-protocol-targets-for-the-first-commitment-period |url-status=live }}</ref> Some Parties have emissions limitations reduce below the base year level, some have limitations at the base year level (no permitted increase above the base year level), while others have limitations above the base year level. | |||

| Emission limits do not include emissions by international aviation and shipping.<ref name="shippingandaviation"> | |||

| {{citation |last=Adam |first=David |title=UK to seek pact on shipping and aviation pollution at climate talks |date=2 December 2007 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2007/dec/03/climatechange.greenpolitics |work=The Guardian}} | |||

| </ref> Although Belarus and Turkey are listed in the convention's Annex I, they do not have emissions targets as they were not Annex I Parties when the Protocol was adopted.<ref name="2011 unfccc kyoto protocol targets" /> Kazakhstan does not have a target, but has declared that it wishes to become an Annex I Party to the convention.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Proposal to amend Annexes I and II to remove the name of Turkey and to amend Annex I to add the name of Kazakhstan |url=https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-convention/history-of-the-convention/proposal-to-amend-annexes-i-and-ii-to-remove-the-name-of-turkey-and-to-amend-annex-i-to-add-the-name |access-date=2020-04-22 |website=unfccc.int |archive-date=28 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200728202017/https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-convention/history-of-the-convention/proposal-to-amend-annexes-i-and-ii-to-remove-the-name-of-turkey-and-to-amend-annex-i-to-add-the-name |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{hidden begin|title=Annex I countries under the Kyoto Protocol, their 2008–2012 commitments as % of base year, and 1990 emission levels (% of all Annex I countries)<ref name="2011 unfccc kyoto protocol targets" /><ref>{{cite web | |||

| |date = 12 November 2009 | |||

| |title = Kyoto burden-sharing targets for EU-15 countries | |||

| |publisher = European Environment Agency (EEA) | |||

| |url = https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/kyoto-burden-sharing-targets-for-eu-15-countries | |||

| |access-date = 28 January 2019 | |||

| |archive-date = 22 December 2018 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20181222030424/https://www.eea.europa.eu//data-and-maps/figures/kyoto-burden-sharing-targets-for-eu-15-countries | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref>}} | |||

| {| | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="width:25%; vertical-align:top;"| | |||

| ] – 108% (2.1% of 1990 emissions) <br /> | |||

| ] – 87% <br /> | |||

| ] – 95% (subject to acceptance by other parties)<br /> | |||

| ] – 92.5% <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% (0.6%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 94% (3.33%) (withdrew) <br /> | |||

| ] – 95% () <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% (1.24%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 79% <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% (0.28%) | |||

| | style="width:25%; vertical-align:top;"| | |||

| ] – 100% <br /> | |||

| ] – 100% <br /> | |||

| ] – 79% <br /> | |||

| ] – 125% <br /> | |||

| ] – 94% (0.52%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 110% (0.02%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 113% <br /> | |||

| ] – 93.5% <br /> | |||

| ] – 94% (8.55%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% (0.17%) | |||

| | style="width:25%; vertical-align:top;"| | |||

| ] – 92% (0.0015%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% <br /> | |||

| ] – 72% <br /> | |||

| ] – 94% <br /> | |||

| ] – 100% (0.19%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 101% (0.26%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 94% (3.02%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% (1.24%) | |||

| | style="width:25%; vertical-align:top;"| | |||

| ] – 100% (17.4%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% (0.42%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% <br /> | |||

| ] – 115% <br /> | |||

| ] – 104% <br /> | |||

| ] – 92% (0.32%) <br /> | |||

| ] – 100% <br /> | |||

| ] – 87.5% <br /> | |||

| ] – 93% (36.1%) (non-party) | |||

| |} | |||

| {{hidden end}} | |||

| For most state parties, 1990 is the base year for the national GHG inventory and the calculation of the assigned amount.<ref name="2008 unfccc kyoto protocol reference manual">{{citation |author=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) |title=Kyoto Protocol Reference Manual On Accounting of Emissions and Assigned Amount |url=http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/publications/08_unfccc_kp_ref_manual.pdf |page=55 |year=2008 |location=Bonn, Germany |publisher=Climate Change Secretariat (UNFCCC) |isbn=978-92-9219-055-2 |access-date=30 December 2011 |archive-date=29 April 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100429230813/http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/publications/08_unfccc_kp_ref_manual.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> However, five state parties have an alternative base year:<ref name="2008 unfccc kyoto protocol reference manual" /> | |||

| * Bulgaria: 1988; | |||

| * Hungary: the average of the years 1985–1987; | |||

| * Poland: 1988; | |||

| * Romania: 1989; | |||

| * Slovenia: 1986. | |||

| Annex I Parties can use a range of sophisticated "flexibility" mechanisms (see below) to meet their targets. Annex I Parties can achieve their targets by allocating reduced annual allowances to major operators within their borders, or by allowing these operators to exceed their allocations by offsetting any excess through a mechanism that is agreed by all the parties to the UNFCCC, such as by buying ] from other operators which have excess emissions credits. | |||

| ===Negotiations=== | |||

| {{See also|Views on the Kyoto Protocol#Commentaries on negotiations}} | |||

| Article 4.2 of the UNFCCC commits industrialized countries to " the lead" in reducing emissions.<ref name="grubb original unfccc target"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Grubb|2003|p=144}} | |||

| </ref> The initial aim was for industrialized countries to stabilize their emissions at 1990 levels by 2000.<ref name="grubb original unfccc target"/> The failure of key industrialized countries to move in this direction was a principal reason why Kyoto moved to binding commitments.<ref name="grubb original unfccc target"/> | |||

| At the first UNFCCC Conference of the Parties in Berlin, the ] was able to push for a mandate (the "Berlin mandate") where it was recognized that:<ref name="liverman berlin mandate"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Liverman|2009|p=290}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| * developed nations had contributed most to the then-current concentrations of GHGs in the atmosphere (see ]). | |||

| * developing country emissions per-capita (i.e., average emissions per head of population)<ref>{{citation | |||

| | title=Table A1: Energy-related emissions: Indicator: per capita (metric tons) | |||

| | chapter=Part II: Selected Development Indicators | |||

| | chapter-url=http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/477365-1327504426766/8389626-1327510418796/Statistical-Annex.pdf | |||

| | access-date=31 August 2012 | |||

| | archive-date=1 November 2012 | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121101133001/http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/477365-1327504426766/8389626-1327510418796/Statistical-Annex.pdf | |||

| | url-status=live | |||

| }}, in {{harvnb|World Bank|2010|p=370}}</ref> were still relatively low. | |||

| * and that the share of global emissions from developing countries would grow to meet their development needs. | |||

| During negotiations, the G-77 represented 133 developing countries. China was not a member of the group but an associate.<ref> | |||

| {{harvnb|Dessai|2001|p=4}} | |||

| </ref> It has since become a member.<ref> | |||

| {{harvnb|G-77|2011}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| The Berlin mandate was recognized in the Kyoto Protocol in that developing countries were not subject to emission reduction commitments in the first Kyoto commitment period.<ref name="liverman berlin mandate"/> However, the large potential for growth in developing country emissions made negotiations on this issue tense.<ref name="grubb developing country emissions"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Grubb|2003|pp=145–146}} | |||

| </ref> In the final agreement, the Clean Development Mechanism was designed to limit emissions in developing countries, but in such a way that developing countries do not bear the costs for limiting emissions.<ref name="grubb developing country emissions"/> The general assumption was that developing countries would face quantitative commitments in later commitment periods, and at the same time, developed countries would meet their first round commitments.<ref name="grubb developing country emissions"/> | |||

| ====Emissions cuts==== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| [[File:Overview map of states committed to greenhouse gas limitations in the first Kyoto Protocol period (years 2008-2012) (greyscale).png|thumb|upright=1.8|alt=Refer to caption|Overview map of states committed to greenhouse gas (GHG) limitations in the first Kyoto Protocol period (2008–12):<ref>{{cite web | date=n.d. | url=http://unfccc.int/essential_background/kyoto_protocol/items/1678.php | title=Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Annex B | publisher=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change | access-date= 8 October 2011}}</ref><br /> | |||

| {{legend|#000000|Annex I Parties who have agreed to reduce their GHG emissions below their individual base year levels (see definition in this article)}} | |||

| {{legend|#737373|Annex I Parties who have agreed to cap their GHG emissions at their base year levels}} {{legend|#f2f2f2|Non-Annex I Parties who are not obligated by caps or Annex I Parties with an emissions cap that allows their emissions to expand above their base year levels or countries that have not ratified the Kyoto Protocol}} | |||

| <br /> | |||

| For specific emission reduction commitments of Annex I Parties, see the section of the article on ].<br /> | |||

| <br /> | |||

| The European Union as a whole has, in accordance with this treaty, committed itself to a reduction of 8%. However, many member states (such as Greece, Spain, Ireland and Sweden) have not committed themselves to any reduction while France has committed itself not to expand its emissions (0% reduction).<ref>{{cite web |title=Kyoto 1st commitment period (2008–12) |url=https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/progress/kyoto_1_en |website=] |access-date=2020-03-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161221064248/https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/progress/kyoto_1_en |archive-date=2016-12-21 |url-status=unfit}}</ref>]] | |||

| There were multiple emissions cuts ] during negotiations. The G77 and China were in favour of strong uniform emission cuts across the developed world.<ref name="liverman negotiations"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Liverman|2009|p=291}} | |||

| </ref> The US originally proposed for the second round of negotiations on Kyoto commitments to follow the negotiations of the first.<ref name="grubb second round negotiations"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Grubb|2003|p=148}} | |||

| </ref> In the end, negotiations on the second period were set to open no later than 2005.<ref name="grubb second round negotiations"/> Countries over-achieving in their first period commitments can "bank" their unused allowances for use in the subsequent period.<ref name="grubb second round negotiations"/> | |||

| The EU initially argued for only three GHGs to be included – {{CO2}}, {{chem2|CH4}}, and {{chem2|N2O}} – with other gases such as HFCs regulated separately.<ref name="liverman negotiations"/> The EU also wanted to have a "bubble" commitment, whereby it could make a collective commitment that allowed some EU members to increase their emissions, while others cut theirs.<ref name="liverman negotiations"/> | |||

| The most vulnerable nations – the ] (AOSIS) – pushed for deep uniform cuts by developed nations, with the goal of having emissions reduced to the greatest possible extent.<ref name="liverman negotiations"/> Countries that had supported differentiation of targets had different ideas as to how it should be calculated, and many different indicators were proposed.<ref name="grubb differentiation"/> Two examples include differentiation of targets based on ] (GDP), and differentiation based on ] (energy use per unit of economic output).<ref name="grubb differentiation"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Grubb|2003|p=151}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| The final targets negotiated in the Protocol are the result of last minute political compromises.<ref name="liverman negotiations"/> The targets closely match those decided by Argentinian Raul Estrada, the ] who chaired the negotiations.<ref> | |||

| {{harvnb|Depledge|2000|p=46}} | |||

| </ref> The numbers given to each Party by Chairman Estrada were based on targets already pledged by Parties, information received on latest negotiating positions, and the goal of achieving the strongest possible environmental outcome.<ref> | |||

| {{harvnb|Depledge|2000|p=44}} | |||

| </ref> The final targets are weaker than those proposed by some Parties, e.g., the ] and the G-77 and China, but stronger than the targets proposed by others, e.g., Canada and the United States.<ref> | |||

| {{harvnb|Depledge|2000|p=45}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==== Relation to temperature targets ==== | |||

| At the ] held in 2010, Parties to the UNFCCC agreed that future global warming should be limited ] relative to the pre-industrial temperature level.<ref>{{citation |author=] (UNFCCC) |title=Conference of the Parties - Sixteenth Session: Decision 1/CP.16: The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention (English): Paragraph 4 |url=http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf#page=2 |page=3 |year=2011 |location=], ] |publisher=UNFCCC Secretariat |format=PDF |access-date=17 July 2012 |archive-date=13 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200113095453/https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2010/cop16/eng/07a01.pdf#page=2 |url-status=live }}</ref> One of the stabilization levels discussed in relation to this temperature target is to hold atmospheric concentrations of GHGs at 450 ] (ppm) {{CO2}}- eq.<ref>{{citation |author=] (IEA) |title=World Energy Outlook 2010 |page=380 |year=2010 |access-date=17 July 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120715234406/http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weo2010.pdf |url-status=dead |chapter=13. Energy and the ultimate climate change target |chapter-url=http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weo2010.pdf |location=Paris, France |publisher=IEA |isbn=978-92-64-08624-1 |archive-date=15 July 2012 |title-link=World Energy Outlook}}</ref> Stabilization at 450 ppm could be associated with a 26 to 78% risk of exceeding the 2 °C target.<ref>{{citation |last1=Levin |first1=K. |title=Working Paper: Comparability of Annex I Emission Reduction Pledges |date=February 2010 |url=http://pdf.wri.org/working_papers/comparability_of_annex1_emission_reduction_pledges_2010-02-01.pdf |page=16 |location=Washington DC, USA |publisher=] |last2=Bradley |first2=R. |access-date=17 July 2012 |archive-date=13 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130513000602/http://pdf.wri.org/working_papers/comparability_of_annex1_emission_reduction_pledges_2010-02-01.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Scenarios assessed by Gupta ''et al.'' (2007)<ref name="450ppm scenarios">{{citation |last1=Gupta |first1=S. |title=Box 13.7 The range of the difference between emissions in 1990 and emission allowances in 2020/2050 for various GHG concentration levels for Annex I and non-Annex I countries as a group |df=dmy-all |access-date=17 July 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121210151654/http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg3/en/ch13s13-3-3-3.html |url-status=dead |chapter=Chapter 13: Policies, instruments, and co-operative arrangements |chapter-url=http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg3/en/ch13s13-3-3-3.html |display-authors=etal |archive-date=10 December 2012}} | |||

| , in {{harvnb|IPCC AR4 WG3|2007}}</ref> suggest that Annex I emissions would need to be 25% to 40% below 1990 levels by 2020, and 80% to 95% below 1990 levels by 2050. The only Annex I Parties to have made voluntary pledges in line with this are Japan (25% below 1990 levels by 2020) and Norway (30–40% below 1990 levels by 2020).<ref> | |||

| {{citation |author=King, D. |title=International climate change negotiations: Key lessons and next steps |date=July 2011 |url=http://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Climate-Negotiations-report_Final.pdf |page=12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120113033748/http://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Climate-Negotiations-report_Final.pdf |url-status=dead |chapter=Copenhagen and Cancun |location=Oxford, UK |publisher=Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford |display-authors=etal |archive-date=13 January 2012}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Gupta ''et al.'' (2007)<ref name="450ppm scenarios" /> also looked at what 450 ppm scenarios projected for non-Annex I Parties. Projections indicated that by 2020, non-Annex I emissions in several regions (], the ], ], and ] ]) would need to be substantially reduced below ].<ref name="450ppm scenarios" /> "Business-as-usual" are projected non-Annex I emissions in the absence of any new policies to control emissions. Projections indicated that by 2050, emissions in all non-Annex I regions would need to be substantially reduced below "business-as-usual".<ref name="450ppm scenarios" /> | |||

| ===Financial commitments=== | |||

| The Protocol also reaffirms the principle that developed countries have to pay billions of dollars, and supply technology to other countries for climate-related studies and projects. The principle was originally agreed in ]. One such project is ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.adaptation-fund.org/|title=AF - Adaptation Fund|website=www.adaptation-fund.org|access-date=20 June 2011|archive-date=1 January 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110101083317/http://www.adaptation-fund.org/|url-status=live}}</ref> which has been established by the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to finance concrete adaptation projects and programmes in developing countries that are Parties to the Kyoto Protocol. | |||

| ===Implementation provisions=== | |||

| The protocol left several issues open to be decided later by the sixth Conference of Parties ] of the UNFCCC, which attempted to resolve these issues at its meeting in ] in late 2000, but it was unable to reach an agreement due to disputes between the European Union (who favoured a tougher implementation) and the United States, Canada, Japan and Australia (who wanted the agreement to be less demanding and more flexible). | |||

| In 2001, a continuation of the previous meeting (COP6-bis) was held in ],<ref>], {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200728204839/https://enb.iisd.org/climate/cop6bis/ |date=28 July 2020 }}, accessed 27 May 2020</ref> where the required decisions were adopted. After some concessions, the supporters of the protocol (led by the ]) managed to secure the agreement of Japan and ] by allowing more use of ]. | |||

| ] was held from 29 October 2001 through 9 November 2001 in ] to establish the final details of the protocol. | |||

| The first Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (MOP1) was held in ] from 28 November to 9 December 2005, along with the 11th conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP11). See ]. | |||

| During COP13 in Bali, 36 developed ] countries (plus the EU as a party in the ]) agreed to a 10% emissions increase for ]; but, since the EU's member states each have individual obligations,<ref>{{cite web | title=The Kyoto protocol – A brief summary | work=European Commission | url=http://ec.europa.eu/environment/climat/kyoto.htm | access-date=19 April 2007 | archive-date=10 August 2009 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090810105055/http://ec.europa.eu/environment/climat/kyoto.htm | url-status=dead }}</ref> much larger increases (up to 27%) are allowed for some of the less developed EU countries (see below {{Section link||Increase in greenhouse gas emission since 1990}}).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/background/items/3145.php |title=Kyoto Protocol |publisher=UNFCCC |date=14 May 2008 |access-date=21 May 2009 |archive-date=13 May 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080513194415/http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/background/items/3145.php |url-status=live }}</ref> Reduction limitations expired in 2013. | |||

| ===Mechanism of compliance=== | |||

| The protocol defines a mechanism of "compliance" as a "monitoring compliance with the commitments and penalties for ]."<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |title=Compliance with the Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change | |||

| |first=S | |||

| |last=Maljean-Dubois | |||

| |work=Synthèse, n° 01, 2007 | |||

| |publisher=Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations | |||

| |url=http://www.iddri.org/Publications/Collections/Syntheses/Compliance-with-the-Kyoto-Protocol-on-Climate-Change | |||

| |access-date=11 July 2008 | |||

| |archive-date=10 November 2009 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091110071921/http://www.iddri.org/Publications/Collections/Syntheses/Compliance-with-the-Kyoto-Protocol-on-Climate-Change | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| }}</ref> According to Grubb (2003),<ref name="grubb compliance"> | |||

| {{harvnb|Grubb|2003|p=157}} | |||

| </ref> the explicit consequences of non-compliance of the treaty are weak compared to domestic law.<ref name="grubb compliance"/> Yet, the compliance section of the treaty was highly contested in the Marrakesh Accords.<ref name="grubb compliance"/> | |||

| ===Monitoring emissions=== | |||

| Monitoring emissions in international agreements is tough as in international law, there is no police power, creating the incentive for states to find 'ways around' monitoring. The Kyoto Protocol regulated six sinks and sources of Gases. Carbon dioxide, Methane, Nirous oxide, Hydroflurocarbons, Sulfur hexafluouride and Perfluorocarbons. Monitoring these gases can become quite a challenge. Methane can be monitored and measured from irrigated rice fields and can be measured by the seedling growing up to harvest. Future implications state that this can be affected by more cost effective ways to control emissions as changes in types of fertilizer can reduce emissions by 50%. In addition to this, many countries are unable to monitor certain ways of carbon absorption through trees and soils to an accurate level.<ref>Victor, David G. The Collapse of the Kyoto Protocol and the Struggle to Slow Global Warming. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 2004.</ref> | |||

| ===Enforcing emission cuts=== | |||