| Revision as of 17:43, 5 October 2022 edit2601:601:f00:56f0:3413:fa1f:10be:8488 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:20, 30 December 2024 edit undoOAbot (talk | contribs)Bots442,978 editsm Open access bot: pmc updated in citation with #oabot. | ||

| (64 intermediate revisions by 21 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Overview of relationship between male circumcision and HIV}} | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| {{About|male circumcision and HIV|information on female circumcision|Female genital mutilation}} | |||

| ⚫ | Male ] reduces the risk of ] from HIV positive women to men in high risk populations.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sharma |first1=Adhikarimayum Lakhikumar |last2=Hokello |first2=Joseph |last3=Tyagi |first3=Mudit |date=2021-06-25 |title=Circumcision as an Intervening Strategy against HIV Acquisition in the Male Genital Tract |journal=Pathogens |volume=10 |issue=7 |pages=806 |doi=10.3390/pathogens10070806 |pmid=34201976 |pmc=8308621 |issn=2076-0817 |quote=There is disputed immunological evidence in support of MC in preventing the heterosexual acquisition of HIV-1.|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last1=Merson |first1=Michael |title=The AIDS Pandemic: Searching for a Global Response |last2=Inrig |first2=Stephen |publisher=] |year=2017 |isbn=9783319471334 |pages=379 |quote=This led to a consensus that male circumcision should be a priority for HIV prevention in countries and regions with heterosexual epidemics and high HIV and low male circumcision prevalence.}}</ref> | ||

| In 2020, the ] (WHO) reiterated that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention if carried out by medical professionals under safe conditions.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV">{{cite web|title=Preventing HIV Through Safe Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision For Adolescent Boys And Men In Generalized HIV Epidemics | In 2020, the ] (WHO) reiterated that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention if carried out by medical professionals under safe conditions.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV">{{cite web|title=Preventing HIV Through Safe Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision For Adolescent Boys And Men In Generalized HIV Epidemics | ||

| Line 7: | Line 9: | ||

| ==Efficacy== | ==Efficacy== | ||

| === Heterosexual men === | === Heterosexual men === | ||

| {{ |

{{as of|2020}}, past research has shown that circumcision reduces the risk of HIV infection in heterosexual men, although these studies have had limitations.<ref name="farley">{{cite journal |vauthors=Farley TM, Samuelson J, Grabowski MK, Ameyan W, Gray RH, Baggaley R |title=Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context - systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=J Int AIDS Soc |volume=23 |issue=6 |pages=e25490 |date=June 2020 |pmid=32558344 |pmc=7303540 |doi=10.1002/jia2.25490 |type=Review}}</ref> | ||

| The WHO Expert Group on Models To Inform Fast Tracking Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision In HIV Combination Prevention in 2016 found "large benefits" of circumcision in settings with high HIV prevalence and low circumcision prevalence. The Group estimated male circumcision is cost-saving in almost all high priority countries. Furthermore, WHO stated that: "While circumcision reduces a man’s individual lifetime HIV risk, the indirect effect of preventing further HIV transmissions to women, their babies (vertical transmission) and from women to other men has an even greater impact on the population incidence, particularly for circumcisions performed at younger ages (under age | The WHO Expert Group on Models To Inform Fast Tracking Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision In HIV Combination Prevention in 2016 found "large benefits" of circumcision in settings with high HIV prevalence and low circumcision prevalence. The Group estimated male circumcision is cost-saving in almost all high priority countries. Furthermore, WHO stated that: "While circumcision reduces a man’s individual lifetime HIV risk, the indirect effect of preventing further HIV transmissions to women, their babies (vertical transmission) and from women to other men has an even greater impact on the population incidence, particularly for circumcisions performed at younger ages (under age | ||

| Line 13: | Line 15: | ||

| |publisher=World Health Organization |date=March 2016 |url=https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259706/WHO-HIV-2017.39-eng.pdf|access-date=2021-05-26 |archive-date=2020-09-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200923203154/https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259706/WHO-HIV-2017.39-eng.pdf|url-status=live }}</ref> | |publisher=World Health Organization |date=March 2016 |url=https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259706/WHO-HIV-2017.39-eng.pdf|access-date=2021-05-26 |archive-date=2020-09-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200923203154/https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259706/WHO-HIV-2017.39-eng.pdf|url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| Newly |

Newly circumcised HIV infected men who are not taking ] can ] the HIV virus from the circumcision wound, thus increasing the immediate risk of HIV transmission to female partners.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> This risk of post-operative transmission presents a challenge, although in the long-term it is possible the circumcision of HIV-infected men helps lessen heterosexual HIV transmission overall. Such viral shedding can be mitigated by the use of antiretroviral drugs.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Tobian AA, Adamu T, Reed JB, Kiggundu V, Yazdi Y, Njeuhmeli E |title=Voluntary medical male circumcision in resource-constrained settings |journal=Nat Rev Urol |volume=12 |issue=12 |pages=661–70 |date=December 2015 |pmid=26526758 |doi=10.1038/nrurol.2015.253 |s2cid=10432723 |type=Review}}</ref> Additional research is needed to ascertain the existence and potential risk of viral shedding from circumcision wounds. | ||

| === |

===Men who have sex with men=== | ||

| The ] does not recommend circumcision as protection against male to male HIV transmission, as evidence is lacking in regards to receptive anal intercourse. The WHO also states that MSM should not be excluded from circumcision services in countries in eastern and southern ], and that circumcision may be effective at limiting the spread of HIV for MSM if they also engage in vaginal sex with women.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> | The ] does not recommend circumcision as protection against male to male HIV transmission, as evidence is lacking in regards to receptive anal intercourse. The WHO also states that ] should not be excluded from circumcision services in countries in eastern and southern ], and that circumcision may be effective at limiting the spread of HIV for MSM if they also engage in vaginal sex with women.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> | ||

| ===Regional differences=== | ===Regional differences=== | ||

| Whether circumcision is beneficial to developed countries for HIV prevention purposes is undetermined.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /><ref name="kim_2010">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kim HH, Li PS, Goldstein M |title=Male circumcision: Africa and beyond? |journal=Curr Opin Urol |volume=20 |issue=6 |pages=515–9 |date=November 2010 |pmid=20844437 |doi=10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b21 |s2cid=2158164 |url=}}</ref> It is not known whether the effect of male circumcision differs by HIV-1 variant. The predominant subtype of HIV-1 in the ] is subtype B, and in Africa, the predominant subtypes are A, C, and D.<ref>{{Cite journal |

Whether circumcision is beneficial to developed countries for HIV prevention purposes is undetermined.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /><ref name="kim_2010">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kim HH, Li PS, Goldstein M |title=Male circumcision: Africa and beyond? |journal=Curr Opin Urol |volume=20 |issue=6 |pages=515–9 |date=November 2010 |pmid=20844437 |doi=10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b21 |s2cid=2158164 |url=}}</ref> It is not known whether the effect of male circumcision differs by HIV-1 variant. The predominant subtype of HIV-1 in the ] is subtype B, and in Africa, the predominant subtypes are A, C, and D.<ref>{{Cite journal|doi = 10.1186/s12301-019-0005-2|title = Male circumcision and global HIV/AIDS epidemic challenges|year = 2019|last1 = Olapade-Olaopa|first1 = Emiola Oluwabunmi|last2 = Salami|first2 = Mudasiru Adebayo|last3 = Lawal|first3 = Taiwo Akeem|journal = African Journal of Urology|volume = 25|s2cid = 208085886|doi-access = free}}</ref> | ||

| ==Recommendations== | ==Recommendations== | ||

| <!-- dummy edit; can be deleted. --> | |||

| The most recent WHO review of the evidence reiterates prior estimates of the impact of male circumcision on HIV incidence rates. In 2020, WHO again concluded that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention and that the promotion of male circumcision is an essential strategy, in addition to other preventive measures, for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men. Eastern and southern Africa had a particularly low prevalence of circumcised males. This region has a disproportionately high HIV infection rate, with a significant | The most recent WHO review of the evidence reiterates prior estimates of the impact of male circumcision on HIV incidence rates. In 2020, WHO again concluded that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention and that the promotion of male circumcision is an essential strategy, in addition to other preventive measures, for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men. Eastern and southern Africa had a particularly low prevalence of circumcised males. This region has a disproportionately high HIV infection rate, with a significant | ||

| number of those infections stemming from heterosexual transmission. | |||

| number of those infections stemming from heterosexual transmission. Some researchers question the validity of this conclusion, asserting that it relies on a correlation/causation logical fallacy. They suggest that HIV transmission is more likely to be influenced by sociocultural factors than by circumcision. They cite statistics that show that HIV is more common in the United States, which has a high rate of neonatal circumsion, than in most European nations, almost all of which have a low rate of circumcision. | |||

| The WHO has made voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) a priority intervention in that region since their 2007 recommendations.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" |

The WHO has made voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) a priority intervention in that region since their 2007 recommendations.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> | ||

| ⚫ | {{blockquote|text=Although these results confirm that male circumcision reduces the risk of men becoming infected with HIV, the UN agencies emphasize that it does not provide complete protection against HIV infection. Circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and, if HIV-positive, can infect their sexual partners. Male circumcision should never replace other known effective prevention methods and should always be considered as part of a comprehensive prevention package, which includes correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reduction in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations, and HIV testing, counseling, and treatment.|author=World Health Organization|source=Joint WHO/UNAIDS Statement made in 2007.<ref name="WHOsec">{{cite press release | url = https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s04/en/index.html | title = WHO and UNAIDS Secretariat welcome corroborating findings of trials assessing impact of male circumcision on HIV risk | access-date = 2007-02-23 | date = February 23, 2007 | publisher = World Health Organization | archive-date = 2007-02-26 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070226135123/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s04/en/index.html | url-status = dead }}</ref>}} | ||

| ⚫ | In the United States, the ] (AAP) led a 2012 task force which included the ] (AAFP), the ] (ACOG), and the ] (CDC). The task force concluded that circumcision may be helpful for the prevention of HIV in the United States.<ref name="AAP_2012">{{cite journal |author=American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision |title=Technical Report |journal=Pediatrics |volume=130 |issue=3 |year=2012 |pages=e756–e785 |issn=0031-4005 |pmid=22926175 |doi=10.1542/peds.2012-1990 |url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/e756.full |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120920054623/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/e756.full |archive-date=2012-09-20 |doi-access=free }}</ref> The CDC 2018 position on circumcision and HIV recommended that circumcision should continue to be offered to parents who are ] of the benefits and risks, including a potential reduction in risk of HIV transmission. The position asserts that circumcision conducted after sexual debut can result in missed opportunities for HIV prevention.<ref name="CDCPrevHIV2018" /> | ||

| ⚫ | {{ |

||

| Because the evidence that circumcision prevents HIV mainly comes from studies conducted in Africa, the ] (KNMG) |

Because the evidence that circumcision prevents HIV mainly comes from studies conducted in Africa, the ] (KNMG) questioned the applicability of those studies to developed countries. Circumcision has not been included in their HIV prevention recommendations. The KNMG circumcision policy statement was endorsed by several Dutch medical associations. The policy statement was initially released in 2010, but was reviewed again and accepted in 2022.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors KNMG viewpoint|url=https://www.knmg.nl/advies-richtlijnen/dossiers/jongensbesnijdenis|date=31 March 2022}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | In the United States, the ] (AAP) led a 2012 task force which included the ] (AAFP), the ] (ACOG), and the ] (CDC). The task force concluded that circumcision may be helpful for the prevention of HIV in the United States.<ref name="AAP_2012">{{cite journal |author=American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision |title=Technical Report |journal=Pediatrics |volume=130 |issue=3 |year=2012 |pages=e756–e785 |issn=0031-4005 |pmid=22926175 |doi=10.1542/peds.2012-1990 |url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/e756.full |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120920054623/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/e756.full |archive-date=2012-09-20 |doi-access=free }}</ref> The CDC 2018 position on circumcision and HIV recommended that circumcision should continue to be offered to parents who are ] of the benefits and risks, including a potential reduction in risk of HIV transmission. The position asserts that circumcision conducted after sexual debut can result in missed opportunities for HIV prevention.<ref name="CDCPrevHIV2018" |

||

| Ethics | |||

| There is considerable criticism of routine infant circumcision outside of the United States. Task forces in many Western nations have suggested bias on the part of the AAP task force. In an article published in the American Academy of Pediatrics publication, Doctors from 16 European nations denounced the AAP's 2012 statement. They asserted that, "Circumcision conflicts with children’s rights and doctors’ oath and can have serious long-term consequences." They suggest that the evidence is not sufficient to render the practice ethical and that there is no reason the decision can't be made by children once they are of age to consent. They point out that in their analysis, the AAP task force assigned no value to bodily integrity, did not analyze potential protective and sexual functions of the foreskin, and did not address criticisms (to the satisfaction of the critics) of the African study methodologies with rigor. | |||

| Critical attention has been drawn to the AAP's usage of research conducted by Professor Brian J. Morris, a researcher frequently cited in arguments supported routine infant circumcision. Professor Morris is not a specialist in bioethics, statistics, or epidemiology. He is implicated as a member of a group known as the Gilgal Society that fetishizes circumcision, including among children. Some of the texts on Morris' website have pedophilic content. Another member and frequent collaborator with Morris, Vernon Quaintance, was arrested on charges of pedophilia. The AAP relies heavily on the research of members of this group. | |||

| There are also ethical concerns regarding studies performed in Africa, which some critics have condemned as racist. They draw parallels between the circumcision trials and the Tuskegee experiments, asserting that the WHO and CDC are using Africa as a human laboratory. | |||

| Scientific Dissent | |||

| Some analyses of the African circumcision studies assert that there were considerable methdological flaws in the studies performed in Africa. They critice the studies for a variety of biases: expectation bias (both researcher and participant), selection bias, lead-time bias, attrition bias, duration bias, lack of placebo control, and early termination bias. Even assuming that the studies were methodologically sound, they question their applicability to neonatal male circumcision in the United States. The studies in Africa assert a reduction in the risk of heterosexual HIV transmission in adults who are circumcised, but in the United States, circumcision is primarily performed on infants. In addition, over 70% of HIV diagnoses in the United States occur among men who have sex with men. This has led some scientists to conclude that the conclusions, be they methodologically sound or not, are not applicable to circumcision in the United States. | |||

| Some assert that the AAP position failed to adequately measure circumcision complications. They point out that the AAP analyses only reviewed complications in the immediate period after infant circumcision. It did not review complications discovered later in life, such as skin bridges, redundant foreskin, painful erections, pitting, chaffing, and adhesions. They assert that there is no way to accurately measure circumcision complication rates because they rely on hospital reporting, yet a large percentage of circumcisions take place in private medical facilities. There is no mandate on reporting complications, on what constitutes a complication, | |||

| Some critics point out several discrepancies in the treatment of the control and the variable group. The studies do not account for the fact that men circumcision during the study are unable to have sex for at least 4-6 weeks, while their uncircumcised counterparts continue to have sex. Critics mention that those conducting the studies provided safer-sex education to circumcised men, while they did not provide similar education to uncircumcised men. There is also criticism of the lack of a true control. | |||

| Other critics assert that the AAP position did not acknowledge the pain experienced by male infants who are being circumcised. Some studies report increases in pain response to vaccines among circumcised infants. They suggest that infants may experience of a form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder following their circumcision. Some studies assert that infants experience pain more strongly than children and adults. | |||

| Reports of the procedures have revealed that circumcised men were given the impression that the procedure renders them immune to HIV and that they do not need to use condoms. Further study and time is required to determine if this leads to a net increase in HIV transmission. | |||

| Some statisticians criticise the usage of misleading statistical conclusions from the studies. Assuming the methodologies of the studies were sound, which is in question, the conclusion of the studies asserted a 60% relative reduction in HIV transmission. The absolute decrease is only 1.31%. The uncircumcised men had a 2.49% HIV infection rate, while the circumcised men had a 1.18% infection rate. The critics assert that when methdological flaws and biases are accounted for, not only does this not exceed the margin of error, but it's also possible that circumcision increases HIV transmission rates. This is corroborated by other studies performed that suggest that circumcision has no effect on transmission or even a harmful effect. | |||

| ==Mechanism of action== | ==Mechanism of action== | ||

| While the biological mechanism of action is not known, a 2020 meta-analysis stated "the consistent protective effect suggests that the reasons for the heterogeneity lie in concomitant individual social and medical factors, such as presence of STIs, rather than a different biological impact of circumcision."<ref name="farley" /> The inner foreskin harbours an increased density of CD4 T-cells and releases increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Hence the sub-preputial space displays a pro-inflammatory environment, conducive to HIV infection.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Prodger |first1=Jessica L. |title=The biology of how circumcision reduces HIV susceptibility: broader implications for the prevention field |journal=AIDS Research and Therapy |date=September 2017 |volume=14 |issue=1 |page=49 |doi=10.1186/s12981-017-0167-6|pmid=28893286 |pmc=5594533 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | While the biological mechanism of action is not known, a 2020 meta-analysis stated "the consistent protective effect suggests that the reasons for the heterogeneity lie in concomitant individual social and medical factors, such as presence of STIs, rather than a different biological impact of circumcision."<ref name="farley" /> The inner foreskin harbours an increased density of CD4 T-cells and releases increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Hence the sub-preputial space displays a pro-inflammatory environment, conducive to HIV infection.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Prodger |first1=Jessica L. |title=The biology of how circumcision reduces HIV susceptibility: broader implications for the prevention field |journal=AIDS Research and Therapy |date=September 2017 |volume=14 |issue=1 |page=49 |doi=10.1186/s12981-017-0167-6|pmid=28893286 |pmc=5594533 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | ||

| ]s (part of the human immune system) under the foreskin may be a source of entry for HIV.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Weiss HA, Dickson KE, Agot K, Hankins CA | title = Male circumcision for HIV prevention: current research and programmatic issues | journal = AIDS | volume = 24 | issue = Suppl 4 | pages = S61-9 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 21042054 | pmc = 4233247 | doi = 10.1097/01.aids.0000390708.66136.f4 | type = Randomized controlled trial }}</ref> Excising the foreskin removes what is thought to be a main entry point for the HIV virus.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Szabo R, Short RV |title=How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection? |journal=BMJ |volume=320 |issue=7249 |pages=1592–4 |date=June 2000 |pmid=10845974 |pmc=1127372 |doi=10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592 |type=Review}}</ref> | |||

| Critics of this theory assert that circumcision exposes the mucosal surfaces and leaves open wounds on the penis. It takes years for keratinization to occur, and during that time, the condition of the penile surface remains similar to that of an uncircumcised penis, but with the added complication of the circumcision wound. Those conducting the studies terminated them early, which did not allow them to monitor HIV transmission over time, and to account for the delay in keratinization and the existence of a penile wound. | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 64: | Line 44: | ||

| Valiere Alcena, in a 1986 letter to the ''New York State Journal of Medicine,'' noted that low rates of circumcision in parts of Africa had been linked to the ].<ref name="taken">{{cite journal | type = Comment | vauthors = Alcena V | title = AIDS in Third World countries | journal = PLOS Medicine | date = 19 October 2006 | volume = 86 | issue = 8 | page = 446 | pmid = 3463895 | url = http://www.plosmedicine.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=15231 | access-date = 10 January 2014 | archive-date = 10 January 2014 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110204325/http://www.plosmedicine.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=15231 | url-status = dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |type = Letter |vauthors = Alcena V |title = AIDS in Third World countries |journal = New York State Journal of Medicine |volume = 86 |issue = 8 |pages = 446 |date = August 1986 |pmid = 3463895 |url = http://www.popline.org/node/363663 |access-date = 2014-01-10 |archive-date = 2014-01-10 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110194304/http://www.popline.org/node/363663 |url-status = live }}</ref> Aaron J. Fink several months later also proposed that circumcision could have a preventive role when the '']'' published his letter, "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS," in October, 1986.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fink AJ | title = A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 315 | issue = 18 | pages = 1167 | date = October 1986 | pmid = 3762636 | doi = 10.1056/nejm198610303151818 | type = Letter }}</ref> By 2000, over 40 epidemiological studies had been conducted to investigate the relationship between circumcision and HIV infection.<ref name="Szabo">{{cite journal | vauthors = Szabo R, Short RV | title = How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection? | journal = BMJ | volume = 320 | issue = 7249 | pages = 1592–4 | date = June 2000 | pmid = 10845974 | pmc = 1127372 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592 | type = Review }}</ref> A meta-analysis conducted by researchers at the ] examined 27 studies of circumcision and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that these showed circumcision to be "associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection" that could form part of a useful public health strategy.<ref name="Weiss2000">{{cite journal | vauthors = Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ | s2cid = 21857086 | title = Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = AIDS | volume = 14 | issue = 15 | pages = 2361–70 | date = October 2000 | pmid = 11089625 | doi = 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018 | url = http://www.aidsonline.com/pt/re/aids/pdfhandler.00002030-200010200-00018.pdf | url-status = dead | type = Meta-analysis | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110151608/http://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2000/10200/Male_circumcision_and_risk_of_HIV_infection_in.18.aspx | archive-date = 2014-01-10 }}</ref> A 2005 review of 37 observational studies expressed reservations about the conclusion because of possible ]s, since all studies to date had been observational as opposed to ]s. The authors stated that three randomized controlled trials then underway in Africa would provide "essential evidence" about the effects of circumcision on preventing HIV.<ref name="Siegfried2005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, Volmink J, Egger M, Low N, Walker S, Williamson P | display-authors = 6 | title = HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies | journal = The Lancet. Infectious Diseases | volume = 5 | issue = 3 | pages = 165–73 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 15766651 | doi = 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5 | type = Review }}</ref> | Valiere Alcena, in a 1986 letter to the ''New York State Journal of Medicine,'' noted that low rates of circumcision in parts of Africa had been linked to the ].<ref name="taken">{{cite journal | type = Comment | vauthors = Alcena V | title = AIDS in Third World countries | journal = PLOS Medicine | date = 19 October 2006 | volume = 86 | issue = 8 | page = 446 | pmid = 3463895 | url = http://www.plosmedicine.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=15231 | access-date = 10 January 2014 | archive-date = 10 January 2014 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110204325/http://www.plosmedicine.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=15231 | url-status = dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |type = Letter |vauthors = Alcena V |title = AIDS in Third World countries |journal = New York State Journal of Medicine |volume = 86 |issue = 8 |pages = 446 |date = August 1986 |pmid = 3463895 |url = http://www.popline.org/node/363663 |access-date = 2014-01-10 |archive-date = 2014-01-10 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110194304/http://www.popline.org/node/363663 |url-status = live }}</ref> Aaron J. Fink several months later also proposed that circumcision could have a preventive role when the '']'' published his letter, "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS," in October, 1986.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fink AJ | title = A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 315 | issue = 18 | pages = 1167 | date = October 1986 | pmid = 3762636 | doi = 10.1056/nejm198610303151818 | type = Letter }}</ref> By 2000, over 40 epidemiological studies had been conducted to investigate the relationship between circumcision and HIV infection.<ref name="Szabo">{{cite journal | vauthors = Szabo R, Short RV | title = How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection? | journal = BMJ | volume = 320 | issue = 7249 | pages = 1592–4 | date = June 2000 | pmid = 10845974 | pmc = 1127372 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592 | type = Review }}</ref> A meta-analysis conducted by researchers at the ] examined 27 studies of circumcision and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that these showed circumcision to be "associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection" that could form part of a useful public health strategy.<ref name="Weiss2000">{{cite journal | vauthors = Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ | s2cid = 21857086 | title = Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = AIDS | volume = 14 | issue = 15 | pages = 2361–70 | date = October 2000 | pmid = 11089625 | doi = 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018 | url = http://www.aidsonline.com/pt/re/aids/pdfhandler.00002030-200010200-00018.pdf | url-status = dead | type = Meta-analysis | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110151608/http://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2000/10200/Male_circumcision_and_risk_of_HIV_infection_in.18.aspx | archive-date = 2014-01-10 }}</ref> A 2005 review of 37 observational studies expressed reservations about the conclusion because of possible ]s, since all studies to date had been observational as opposed to ]s. The authors stated that three randomized controlled trials then underway in Africa would provide "essential evidence" about the effects of circumcision on preventing HIV.<ref name="Siegfried2005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, Volmink J, Egger M, Low N, Walker S, Williamson P | display-authors = 6 | title = HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies | journal = The Lancet. Infectious Diseases | volume = 5 | issue = 3 | pages = 165–73 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 15766651 | doi = 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5 | type = Review }}</ref> | ||

| Experimental evidence was needed to establish a causal relationship, so three ] (RCT) were commissioned as a means to reduce the effect of any confounding factors. Trials took place in ], ] and ].<ref name=":1">{{cite journal |vauthors=Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J |date=April 2009 |title=Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men |journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |issue=2 |pages=CD003362 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2 |pmid=19370585 |veditors=Siegfried N}}</ref> All three trials were stopped early by their monitoring boards because those in the circumcised group had a substantially lower rate of HIV |

Experimental evidence was needed to establish a causal relationship, so three ]s (RCT) were commissioned as a means to reduce the effect of any confounding factors. Trials took place in ], ] and ].<ref name=":1">{{cite journal |vauthors=Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J |date=April 2009 |title=Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men |journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |issue=2 |pages=CD003362 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2 |pmid=19370585 |veditors=Siegfried N|pmc=11666075 }}</ref> All three trials were stopped early by their monitoring boards because those in the circumcised group had a substantially lower rate of HIV incidence than the control group, and hence it was seen as unethical to withhold the procedure, in light of strong evidence of efficacy.<ref name=":1" /> In 2009, a ] which included the results of the three ]s found "strong" evidence that the acquisition of HIV by a man during sex with a woman was decreased by 54% (], 38% to 66%) over 24 months if the man was circumcised. The review also found a low incidence of adverse effects from circumcision in the trials reviewed.<ref name="Cochrane2009">{{cite journal |last1=Siegfried |first1=Nandi |last2=Muller |first2=Martie |last3=Deeks |first3=Jonathan J |last4=Volmink |first4=Jimmy |title=Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men |journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |date=15 April 2009 |issue=2 |pages=CD003362 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2|pmid=19370585 |pmc=11666075 }}</ref> WHO assessed the trials as "gold standard" studies and found "strong and consistent" evidence from later studies that confirmed the results.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> In 2020, a review including post-study follow up from the three randomized controlled trials, as well as newer observational studies, found a 59% relative reduction in HIV incidence, and 1.31% absolute decrease across the three randomized controlled trials, as well as continued protection for up to 6 years after the studies began.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Farley |first1=Timothy MM |last2=Samuelson |first2=Julia |last3=Grabowski |first3=M Kate |last4=Ameyan |first4=Wole |last5=Gray |first5=Ronald H |last6=Baggaley |first6=Rachel |title=Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context – systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=Journal of the International AIDS Society |date=June 2020 |volume=23 |issue=6 |pages=e25490 |doi=10.1002/jia2.25490|pmid=32558344 |pmc=7303540 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | ||

| == Society and culture == | == Society and culture == | ||

| Line 70: | Line 50: | ||

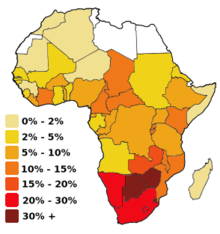

| The prevalence of circumcision varies across Africa.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Marck J | title = Aspects of male circumcision in sub-equatorial African culture history | journal = Health Transition Review | volume = 7 Suppl | issue = Suppl | pages = 337–60 | year = 1997 | pmid = 10173099 | url = http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Marck1.pdf | access-date = 2009-03-23 | url-status = dead | type = Review | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080906115430/http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Marck1.pdf | archive-date = 2008-09-06 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|year=2007|title=Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability|journal=Who/Unaids|url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf|access-date=2008-10-16|archive-date=2015-07-15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150715135808/http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> Studies were conducted to assess the acceptability of promoting circumcision; in 2007, country consultations and planning to scale up male circumcision programmes took place in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal | year = 2008 | title = Towards Universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector | journal = Who/Unaids/Unicef | pages = 75 | url = http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf | access-date = 2008-10-16 | archive-date = 2008-10-18 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081018050047/http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf | url-status = live }}</ref> | The prevalence of circumcision varies across Africa.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Marck J | title = Aspects of male circumcision in sub-equatorial African culture history | journal = Health Transition Review | volume = 7 Suppl | issue = Suppl | pages = 337–60 | year = 1997 | pmid = 10173099 | url = http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Marck1.pdf | access-date = 2009-03-23 | url-status = dead | type = Review | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080906115430/http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Marck1.pdf | archive-date = 2008-09-06 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|year=2007|title=Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability|journal=Who/Unaids|url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf|access-date=2008-10-16|archive-date=2015-07-15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150715135808/http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> Studies were conducted to assess the acceptability of promoting circumcision; in 2007, country consultations and planning to scale up male circumcision programmes took place in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal | year = 2008 | title = Towards Universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector | journal = Who/Unaids/Unicef | pages = 75 | url = http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf | access-date = 2008-10-16 | archive-date = 2008-10-18 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081018050047/http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf | url-status = live }}</ref> | ||

| ===Programs=== | ===Programs=== | ||

| In 2011, UNAIDS prioritized 15 high HIV prevalence countries in eastern and southern Africa, with a goal of circumcising 80% of men (20.8 million) by the end of 2016.<ref name="UNAIDS"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170729033902/http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2686_WAD2014report_en.pdf |date=2017-07-29 }} WHO. 2014.</ref> As of 2020, WHO estimated that 250,000 HIV infections have been averted by the 23 million circumcisions conducted in the 15 priority countries of eastern and southern Africa.<ref name=WHO-PrevHIV |

In 2011, UNAIDS prioritized 15 high HIV prevalence countries in eastern and southern Africa, with a goal of circumcising 80% of men (20.8 million) by the end of 2016.<ref name="UNAIDS"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170729033902/http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2686_WAD2014report_en.pdf |date=2017-07-29 }} WHO. 2014.</ref> As of 2020, WHO estimated that 250,000 HIV infections have been averted by the 23 million circumcisions conducted in the 15 priority countries of eastern and southern Africa.<ref name=WHO-PrevHIV /> | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

Latest revision as of 07:20, 30 December 2024

Overview of relationship between male circumcision and HIV This article is about male circumcision and HIV. For information on female circumcision, see Female genital mutilation.Male circumcision reduces the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission from HIV positive women to men in high risk populations.

In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reiterated that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention if carried out by medical professionals under safe conditions. Circumcision reduces the risk that a man will acquire HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) from an infected female partner through vaginal sex. The evidence regarding whether circumcision helps prevent HIV is not as clear among men who have sex with men (MSM). The effectiveness of using circumcision to prevent HIV in the developed world is not determined.

Efficacy

Heterosexual men

As of 2020, past research has shown that circumcision reduces the risk of HIV infection in heterosexual men, although these studies have had limitations.

The WHO Expert Group on Models To Inform Fast Tracking Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision In HIV Combination Prevention in 2016 found "large benefits" of circumcision in settings with high HIV prevalence and low circumcision prevalence. The Group estimated male circumcision is cost-saving in almost all high priority countries. Furthermore, WHO stated that: "While circumcision reduces a man’s individual lifetime HIV risk, the indirect effect of preventing further HIV transmissions to women, their babies (vertical transmission) and from women to other men has an even greater impact on the population incidence, particularly for circumcisions performed at younger ages (under age 25 years)."

Newly circumcised HIV infected men who are not taking antiretroviral therapy can shed the HIV virus from the circumcision wound, thus increasing the immediate risk of HIV transmission to female partners. This risk of post-operative transmission presents a challenge, although in the long-term it is possible the circumcision of HIV-infected men helps lessen heterosexual HIV transmission overall. Such viral shedding can be mitigated by the use of antiretroviral drugs. Additional research is needed to ascertain the existence and potential risk of viral shedding from circumcision wounds.

Men who have sex with men

The WHO does not recommend circumcision as protection against male to male HIV transmission, as evidence is lacking in regards to receptive anal intercourse. The WHO also states that MSM should not be excluded from circumcision services in countries in eastern and southern Africa, and that circumcision may be effective at limiting the spread of HIV for MSM if they also engage in vaginal sex with women.

Regional differences

Whether circumcision is beneficial to developed countries for HIV prevention purposes is undetermined. It is not known whether the effect of male circumcision differs by HIV-1 variant. The predominant subtype of HIV-1 in the United States is subtype B, and in Africa, the predominant subtypes are A, C, and D.

Recommendations

The most recent WHO review of the evidence reiterates prior estimates of the impact of male circumcision on HIV incidence rates. In 2020, WHO again concluded that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention and that the promotion of male circumcision is an essential strategy, in addition to other preventive measures, for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men. Eastern and southern Africa had a particularly low prevalence of circumcised males. This region has a disproportionately high HIV infection rate, with a significant number of those infections stemming from heterosexual transmission. The WHO has made voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) a priority intervention in that region since their 2007 recommendations.

Although these results confirm that male circumcision reduces the risk of men becoming infected with HIV, the UN agencies emphasize that it does not provide complete protection against HIV infection. Circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and, if HIV-positive, can infect their sexual partners. Male circumcision should never replace other known effective prevention methods and should always be considered as part of a comprehensive prevention package, which includes correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reduction in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations, and HIV testing, counseling, and treatment.

— World Health Organization, Joint WHO/UNAIDS Statement made in 2007.

In the United States, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) led a 2012 task force which included the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The task force concluded that circumcision may be helpful for the prevention of HIV in the United States. The CDC 2018 position on circumcision and HIV recommended that circumcision should continue to be offered to parents who are informed of the benefits and risks, including a potential reduction in risk of HIV transmission. The position asserts that circumcision conducted after sexual debut can result in missed opportunities for HIV prevention.

Because the evidence that circumcision prevents HIV mainly comes from studies conducted in Africa, the Royal Dutch Medical Association (KNMG) questioned the applicability of those studies to developed countries. Circumcision has not been included in their HIV prevention recommendations. The KNMG circumcision policy statement was endorsed by several Dutch medical associations. The policy statement was initially released in 2010, but was reviewed again and accepted in 2022.

Mechanism of action

While the biological mechanism of action is not known, a 2020 meta-analysis stated "the consistent protective effect suggests that the reasons for the heterogeneity lie in concomitant individual social and medical factors, such as presence of STIs, rather than a different biological impact of circumcision." The inner foreskin harbours an increased density of CD4 T-cells and releases increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Hence the sub-preputial space displays a pro-inflammatory environment, conducive to HIV infection.

Langerhans cells (part of the human immune system) under the foreskin may be a source of entry for HIV. Excising the foreskin removes what is thought to be a main entry point for the HIV virus.

History

Valiere Alcena, in a 1986 letter to the New York State Journal of Medicine, noted that low rates of circumcision in parts of Africa had been linked to the high rate of HIV infection. Aaron J. Fink several months later also proposed that circumcision could have a preventive role when the New England Journal of Medicine published his letter, "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS," in October, 1986. By 2000, over 40 epidemiological studies had been conducted to investigate the relationship between circumcision and HIV infection. A meta-analysis conducted by researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine examined 27 studies of circumcision and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that these showed circumcision to be "associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection" that could form part of a useful public health strategy. A 2005 review of 37 observational studies expressed reservations about the conclusion because of possible confounding factors, since all studies to date had been observational as opposed to randomized controlled trials. The authors stated that three randomized controlled trials then underway in Africa would provide "essential evidence" about the effects of circumcision on preventing HIV.

Experimental evidence was needed to establish a causal relationship, so three randomized controlled trials (RCT) were commissioned as a means to reduce the effect of any confounding factors. Trials took place in South Africa, Kenya and Uganda. All three trials were stopped early by their monitoring boards because those in the circumcised group had a substantially lower rate of HIV incidence than the control group, and hence it was seen as unethical to withhold the procedure, in light of strong evidence of efficacy. In 2009, a Cochrane review which included the results of the three randomized controlled trials found "strong" evidence that the acquisition of HIV by a man during sex with a woman was decreased by 54% (95% confidence interval, 38% to 66%) over 24 months if the man was circumcised. The review also found a low incidence of adverse effects from circumcision in the trials reviewed. WHO assessed the trials as "gold standard" studies and found "strong and consistent" evidence from later studies that confirmed the results. In 2020, a review including post-study follow up from the three randomized controlled trials, as well as newer observational studies, found a 59% relative reduction in HIV incidence, and 1.31% absolute decrease across the three randomized controlled trials, as well as continued protection for up to 6 years after the studies began.

Society and culture

The WHO recommends VMMC, as opposed to traditional circumcision. There is some evidence that traditionally circumcised men (i.e. who have been circumcised by a person who is not medically trained) use condoms less often and have higher numbers of sexual partners, increasing their risk of contracting HIV. Newly circumcised men must refrain from sexual activity until the wounds are fully healed.

The prevalence of circumcision varies across Africa. Studies were conducted to assess the acceptability of promoting circumcision; in 2007, country consultations and planning to scale up male circumcision programmes took place in Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Programs

In 2011, UNAIDS prioritized 15 high HIV prevalence countries in eastern and southern Africa, with a goal of circumcising 80% of men (20.8 million) by the end of 2016. As of 2020, WHO estimated that 250,000 HIV infections have been averted by the 23 million circumcisions conducted in the 15 priority countries of eastern and southern Africa.

See also

References

- Sharma, Adhikarimayum Lakhikumar; Hokello, Joseph; Tyagi, Mudit (2021-06-25). "Circumcision as an Intervening Strategy against HIV Acquisition in the Male Genital Tract". Pathogens. 10 (7): 806. doi:10.3390/pathogens10070806. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 8308621. PMID 34201976.

There is disputed immunological evidence in support of MC in preventing the heterosexual acquisition of HIV-1.

- Merson, Michael; Inrig, Stephen (2017). The AIDS Pandemic: Searching for a Global Response. Springer Publishing. p. 379. ISBN 9783319471334.

This led to a consensus that male circumcision should be a priority for HIV prevention in countries and regions with heterosexual epidemics and high HIV and low male circumcision prevalence.

- ^ "Preventing HIV Through Safe Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision For Adolescent Boys And Men In Generalized HIV Epidemics". World Health Organization. 2020. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ Information for providers counseling male patients and parents regarding male circumcision and the prevention of HIV infection, STIs, and other health outcomes (Report). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 22, 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ^ Kim HH, Li PS, Goldstein M (November 2010). "Male circumcision: Africa and beyond?". Curr Opin Urol. 20 (6): 515–9. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b21. PMID 20844437. S2CID 2158164.

- ^ Farley TM, Samuelson J, Grabowski MK, Ameyan W, Gray RH, Baggaley R (June 2020). "Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context - systematic review and meta-analysis". J Int AIDS Soc (Review). 23 (6): e25490. doi:10.1002/jia2.25490. PMC 7303540. PMID 32558344.

- "Models To Inform Fast Tracking Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision In HIV Combination Prevention" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-23. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- Tobian AA, Adamu T, Reed JB, Kiggundu V, Yazdi Y, Njeuhmeli E (December 2015). "Voluntary medical male circumcision in resource-constrained settings". Nat Rev Urol (Review). 12 (12): 661–70. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2015.253. PMID 26526758. S2CID 10432723.

- Olapade-Olaopa, Emiola Oluwabunmi; Salami, Mudasiru Adebayo; Lawal, Taiwo Akeem (2019). "Male circumcision and global HIV/AIDS epidemic challenges". African Journal of Urology. 25. doi:10.1186/s12301-019-0005-2. S2CID 208085886.

- "WHO and UNAIDS Secretariat welcome corroborating findings of trials assessing impact of male circumcision on HIV risk" (Press release). World Health Organization. February 23, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-02-26. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision (2012). "Technical Report". Pediatrics. 130 (3): e756 – e785. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1990. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 22926175. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20.

- "Non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors KNMG viewpoint". 31 March 2022.

- Prodger, Jessica L. (September 2017). "The biology of how circumcision reduces HIV susceptibility: broader implications for the prevention field". AIDS Research and Therapy. 14 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/s12981-017-0167-6. PMC 5594533. PMID 28893286.

- Weiss HA, Dickson KE, Agot K, Hankins CA (October 2010). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention: current research and programmatic issues". AIDS (Randomized controlled trial). 24 (Suppl 4): S61-9. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000390708.66136.f4. PMC 4233247. PMID 21042054.

- Szabo R, Short RV (June 2000). "How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?". BMJ (Review). 320 (7249): 1592–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. PMC 1127372. PMID 10845974.

- Alcena V (19 October 2006). "AIDS in Third World countries". PLOS Medicine (Comment). 86 (8): 446. PMID 3463895. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Alcena V (August 1986). "AIDS in Third World countries". New York State Journal of Medicine (Letter). 86 (8): 446. PMID 3463895. Archived from the original on 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- Fink AJ (October 1986). "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS". The New England Journal of Medicine (Letter). 315 (18): 1167. doi:10.1056/nejm198610303151818. PMID 3762636.

- Szabo R, Short RV (June 2000). "How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?". BMJ (Review). 320 (7249): 1592–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. PMC 1127372. PMID 10845974.

- Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ (October 2000). "Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis". AIDS (Meta-analysis). 14 (15): 2361–70. doi:10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018. PMID 11089625. S2CID 21857086. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-10.

- Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, Volmink J, Egger M, Low N, et al. (March 2005). "HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases (Review). 5 (3): 165–73. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5. PMID 15766651.

- ^ Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J (April 2009). Siegfried N (ed.). "Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. PMC 11666075. PMID 19370585.

- Siegfried, Nandi; Muller, Martie; Deeks, Jonathan J; Volmink, Jimmy (15 April 2009). "Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. PMC 11666075. PMID 19370585.

- Farley, Timothy MM; Samuelson, Julia; Grabowski, M Kate; Ameyan, Wole; Gray, Ronald H; Baggaley, Rachel (June 2020). "Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context – systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 23 (6): e25490. doi:10.1002/jia2.25490. PMC 7303540. PMID 32558344.

- Seeth, Avantika (June 1, 2018). "'It's hassle-free,' says actor Melusi Yeni about his medical circumcision". News24. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

Actor Melusi Yeni was the millionth man to undergo voluntary male medical circumcision at the Sivananda Clinic in KwaZulu-Natal.

- Marck J (1997). "Aspects of male circumcision in sub-equatorial African culture history" (PDF). Health Transition Review (Review). 7 Suppl (Suppl): 337–60. PMID 10173099. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- "Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). Who/Unaids. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- "Towards Universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector" (PDF). Who/Unaids/Unicef: 75. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-18. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- Joint strategic action framework to accelerate the scale-up of voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa, 2012-2016. Archived 2017-07-29 at the Wayback Machine WHO. 2014.

| Circumcision | |

|---|---|

| Medical aspects | |

| History and prevalence | |

| Religious aspects | |

| Ethical and legal aspects | |

| Category | |