| Revision as of 16:12, 5 June 2007 editEllyabe (talk | contribs)8 edits reverting vandalism← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:39, 8 January 2025 edit undoVictory in Germany (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users897 editsmNo edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American baseball player (1886–1961)}} | |||

| {{Not verified|date=January 2007}} | |||

| {{About||the Washington, D.C. lawyer|Ty Cobb (attorney)|the politician|Ty Cobb (politician)|the Soundgarden song|Ty Cobb (song)}} | |||

| {{Mlbretired | |||

| {{redirect|The Georgia Peach|other uses|Georgia Peach (disambiguation)}} | |||

| |bgcolor1=#000769 | |||

| {{pp-move|small=yes}} | |||

| |bgcolor2=#000769 | |||

| {{Use American English|date=July 2021}} | |||

| |textcolor1=white | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2024}} | |||

| |textcolor2=white | |||

| {{Infobox baseball biography | |||

| |name=Tyrus Raymond Cobb | |||

| |name=Ty Cobb | |||

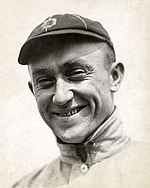

| |image=TyCobb.jpg | |||

| |image=1913 Ty Cobb portrait photo.png | |||

| |width=256 | |||

| |image_size=250 | |||

| |position=] | |||

| |caption=Cobb with the Detroit Tigers in 1913 | |||

| |position=] / ] | |||

| |bats=Left | |bats=Left | ||

| |throws=Right | |throws=Right | ||

| |birth_date={{birth date|mf=yes|1886|12|18}} | |||

| |birthdate=], ] | |||

| |birth_place=], U.S. | |||

| |deathdate={{death date and age|1961|7|17|1886|12|18}} | |||

| |death_date={{death date and age|mf=yes|1961|7|17|1886|12|18}} | |||

| |debutdate=] | |||

| |death_place=], U.S. | |||

| |debutyear=] | |||

| |debutleague = MLB | |||

| |debutteam=] | |||

| |debutdate=August 30 | |||

| |finaldate=] | |||

| |debutyear=1905 | |||

| |finalyear=] | |||

| |debutteam=Detroit Tigers | |||

| |finalteam=] | |||

| |finalleague = MLB | |||

| |stat1label=] | |||

| |finaldate=September 11 | |||

| |stat1value=.366 | |||

| |finalyear=1928 | |||

| |stat2label=] | |||

| |finalteam=Philadelphia Athletics | |||

| |stat2value=117 | |||

| |statleague = MLB | |||

| |stat3label=] | |||

| |stat1label=] | |||

| |stat3value=1938 | |||

| |stat1value=.366 <!--Don't change this, see section "Regular season statistics" below--> | |||

| |teams=<nowiki></nowiki><!--This forces MediaWiki to recognize the first bullet. Kind of a workaround to a bug.--> | |||

| |stat2label=]s | |||

| '''As Player'''<br/> | |||

| |stat2value=4,189 | |||

| ] (] - ])<br/> | |||

| |stat3label=]s | |||

| ] (] - ])<br/> | |||

| |stat3value=117 | |||

| '''As Manager'''<BR> | |||

| |stat4label=] | |||

| ] (] - ])<br/> | |||

| |stat4value=1,944 | |||

| |highlights=<nowiki></nowiki> | |||

| |stat5label=]s | |||

| ;All-Time Records: | |||

| |stat5value=897 | |||

| * Career batting average (.366)<ref name=BaseballRefBatAvg>{{cite web |url=http://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/BA_career.shtml |title=Career Leaders for Batting Average |accessdate=2007-01-30 |publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref> | |||

| |stat6label=Managerial record | |||

| * Career steals of home (54) | |||

| |stat6value=479–444 | |||

| * Career batting titles (11)<ref name=BaseballRefBatAvg/> | |||

| |stat7label=Winning % | |||

| ;Notable Achievements | |||

| |stat7value={{winpct|479|444}} | |||

| * Batted over .320 for 22 straight seasons | |||

| |teams= | |||

| * Batted over .400 three times (], ] & ]) | |||

| '''As player''' | |||

| * Won the ] in ] | |||

| *] ({{mlby|1905}}–{{mlby|1926}}) | |||

| * One of the inaugural members of the Hall of Fame | |||

| *] ({{mlby|1927}}–{{mlby|1928}}) | |||

| *Most hits by left-handed batter (4189) | |||

| '''As manager''' | |||

| *] ({{mlby|1921}}–{{mlby|1926}}) | |||

| |highlights= | |||

| * ] (1911) | |||

| * ] (1909) | |||

| * 12× ] (1907–1915, 1917–1919) | |||

| * ] (1909) | |||

| * 4× ] (1907–1909, 1911) | |||

| * 6× ] (1907, 1909, 1911, 1915–1917) | |||

| * ] by the Tigers | |||

| * ] | |||

| |hoflink = National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||

| |hoftype = National | |||

| |hofdate=] | |||

| |hofvote=98.2% (first ballot) | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Tyrus Raymond Cobb''' (December 18, 1886<ref>{{cite web|title=Ty Cobb|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ty-Cobb|website=Encyclopaedia Britannica|access-date=December 17, 2017}}</ref> – July 17, 1961), nicknamed "'''the Georgia Peach'''", was an American professional baseball ]. A native of rural ], ], Cobb played 24 seasons in ] (MLB). He spent 22 years with the ] and served as the team's ] for the last six, and he finished his career with the ]. In 1936, Cobb received the most votes of any player on the ] for the ], receiving 222 out of a possible 226 votes (98.2%); no other player received a higher percentage of votes until ] in 1992. In 1999, the '']'' ranked Cobb third on its list of "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.baseball-almanac.com/legendary/lisn100.shtml|title=Baseball's 100 greatest players|publisher=Baseball Almanac|access-date=July 21, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Cobb is credited with setting 90 MLB records throughout his career.<ref name=JamesPeachJEI>{{cite journal |last=Peach |first=James |date=June 2004 |title=Thorstein Veblen, Ty Cobb, and the evolution of an institution |journal=Journal of Economic Issues |volume=38 |issue=2 |pages=326–337 |doi=10.1080/00213624.2004.11506692 |s2cid=157860611 |url=http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/summary_0199-514151_ITM |access-date=January 30, 2007 |quote=(Abstract Only) |archive-date=September 29, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070929164528/http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/summary_0199-514151_ITM |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name=Zacharias>{{cite news |last=Zacharias |first=Patricia |title=Ty Cobb, the greatest Tiger of them all |newspaper=] |url=http://info.detnews.com/history/story/index.cfm?id=92&category=sports |access-date=February 26, 2007 |quote=(Abstract Only) |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120720080112/http://info.detnews.com/history/story/index.cfm?id=92&category=sports |archive-date=July 20, 2012 }}</ref><ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb>{{cite web|url=https://baseballbiography.com/ty-cobb-1886|title=The Ballplayers – Ty Cobb|last=Wolpin|first=Stewart|access-date=June 5, 2007|publisher=baseballbiography.com}}</ref><ref name=ESPNSchwartz>{{cite web |last=Schwartz|first=Larry | url=https://www.espn.com/sportscentury/features/00014142.html |title=He was a pain ... but a great pain |access-date=January 30, 2007 |publisher=ESPN Internet Ventures}}</ref> Cobb has won more ] than any other player, with 11 (or 12, depending on source).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/leaders_most_times.shtml |title=Most Times Leading League |access-date=March 21, 2007 |publisher=Sports Reference, Inc |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070521215410/http://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/leaders_most_times.shtml |archive-date=May 21, 2007 |url-status=dead }}</ref> During his entire 24-year career, he hit .300 in a record 23 consecutive seasons, with the exception being his rookie season. He also ], a record he shares with three other players. Cobb has more five-hit games (14) than any other player in major league history. He also holds the career record for stealing home (54 times) and for stealing second base, third base, and home in succession (4 times), and as the youngest player ever to compile 4,000 hits and score 2,000 runs. His combined total of 4,065 runs scored and runs batted in (after adjusting for home runs) is still the highest ever produced by any major league player. Cobb also ranks first in games played by an outfielder in major league history (2,934). He retained many other records for almost a half century or more, including most career ] (3,035) and ]s (11,429 or 11,434 depending on source) until 1974<ref name=BaseballRefCareerGames>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/G_progress.shtml |title=Career Leaders for Games (Progressive)|access-date=March 19, 2007|publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref><ref name=BaseballRefCareerABs>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/AB_progress.shtml |title=Career Leaders for At Bats (Progressive)|access-date=March 19, 2007|publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref> as well as the modern record for most career ]s (892) until 1977.<ref name=BaseballRefCareerSB>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/SB_career.shtml |title=Career Leaders for Stolen Bases |access-date=January 30, 2007 |publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref> He also had the ] ] until 1985 (4,189 or 4,191, depending on source)<ref>{{cite book| last =Soderholm-Difatte| first=Bryan | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FalWDwAAQBAJ&q=ty+cobb+number+of+hits+and+double+counted+1910&pg=PA27 |title=America's Game: A History of Major League Baseball through World War II| page=27|year=2018 |publisher =Rowman and Littlefield | isbn = 9781538110638|access-date=September 29, 2019 }}</ref><ref name=BaseballRefCareerHits>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/H_progress.shtml |title=Career Leaders for Hits (Progressive)|access-date=March 19, 2007|publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref><ref name=Holmes>{{cite book| last =Holmes | first=Dan |year=2004| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8Dm3hqzbyYkC&q=ty+cobb+4,189&pg=PA136 |title=Ty Cobb: A Biography| page=136 |publisher = Greenwood Publishing Group | isbn = 0-313-32869-2 |access-date=January 12, 2009 }}</ref> and most career ] until 2001.<ref name=BaseballRefCareerRuns>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/R_progress.shtml |title=Career Leaders for Runs (Progressive)|access-date=March 19, 2007|publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref> His .366 career batting average was officially listed as the highest-ever until 2024, when MLB decided to include ] players in official statistics.<ref name="2024rev">{{Cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/2024/05/29/g-s1-1525/mlb-negro-leagues-stats-josh-gibson |title=The Negro Leagues are officially part of MLB history—with the records to prove it and most career |first=Rachel |last=Treisman |date=May 29, 2024 |accessdate=May 29, 2024 |publisher=] |department=Sports}}</ref> | |||

| Cobb's reputation, which includes a large college scholarship fund for Georgia residents financed by his early investments in ] and ], has been somewhat tarnished by allegations of racism and violence. These primarily stem from a couple of mostly discredited biographies that were released following his death.<ref name="Gilbert">{{cite web |last=King |first=Gilbert |title=The Knife in Ty Cobb's Back |date=August 30, 2011 |url=http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/history/2011/08/the-knife-in-ty-cobbs-back/ |website=Smithsonian}}</ref> Cobb's reputation as a violent man was exaggerated by his first biographer, sportswriter ], whose stories about Cobb have been proven as ] and largely fictional.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.mlb.com/news/ty-cobb-history-built-on-inaccuracies/c-178601094|title=Ty Cobb history built on inaccuracies|website=MLB.com|language=en|access-date=December 30, 2018}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.freep.com/story/entertainment/arts/2015/06/09/ty-cobb-myth-legend-popular-culture/28765125/|title = How Ty Cobb the truth got lost inside Ty Cobb the myth}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.freep.com/story/entertainment/arts/2015/06/09/ty-cobb-myth-legend-popular-culture/28765125/|title=How Ty Cobb the truth got lost inside Ty Cobb the myth|website=Detroit Free Press|language=en|access-date=December 30, 2018}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2017/07/softer-side-ty-cobb/|title=The Softer Side of Ty Cobb {{!}} The Saturday Evening Post|website=www.saturdayeveningpost.com|date=July 18, 2017|access-date=December 30, 2018}}</ref> While he was known for often violent conflicts, he spoke favorably about black players joining the Major Leagues and was a well-known philanthropist.<ref name="Gilbert"/><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://naplesherald.com/2015/09/24/the-curious-case-of-ty-cobb/ |title=The Curious Case of Ty Cobb |last=Miller |first=Glenn |date=September 24, 2015 |work=Naples Herald |access-date=December 16, 2018 |language=en-US |archive-date=December 16, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181216074102/https://naplesherald.com/2015/09/24/the-curious-case-of-ty-cobb/ |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.donorstrust.org/strategic-giving/ty-cobbs-philanthropy |title=Ty Cobb's Philanthropy Has Lessons for Us All |last=Lipsett |first=Peter |work=DonorsTrust |date=April 6, 2016 |access-date=August 26, 2021 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| Cobb was born in 1886 in ], a small, unincorporated rural community of farmers. He was the first of three children born to William Herschel Cobb<!-- Note: state senators qualify ] --> (1863–1905) and Amanda Chitwood Cobb (1871–1936).<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3uSbqUm8hSAC&pg=PA358|title=The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract|first=Bill|publisher=Simon and Schuster|page=358|year=2003|location=New York|isbn=978-0-7432-2722-3|last=James}}</ref> Cobb's father was a state senator.<ref name="Leerhsen 2016">{{cite web |url=http://imprimis.hillsdale.edu/who-was-ty-cobb-the-history-we-know-thats-wrong/2/ |title=Who was Ty Cobb? The history we know that's wrong |first=Charles |last=Leerhsen |publisher=Hillsdale College |year=2016}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Tyrus Raymond "Ty" Cobb''' (], ] – ], ]), nicknamed '''"The Georgia Peach."''' was a ] ] player. Cobb is widely considered one of the greatest players ever; he set a total of 90 records during his career, and still held 43 records when he retired in 1928.<ref name=JamesPeachJEI>{{cite journal |quotes=(Abstract Only) |last=Peach |first=James |year=2004 |month=June |title=Thorstein Veblen, Ty Cobb, and the evolution of an institution |journal=Journal of Economic Issues |volume= |issue= |pages= |id= |url=http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/summary_0199-514151_ITM |accessdate=2007-01-30 }}</ref> Cobb also received the most votes of any player on the 1936 inaugural ].<ref name=HallofFameVote1936>{{cite web |url=http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/history/hof_voting/year/1936.htm|title=History of BBWAA Hall of Fame Voting:1936 Election |accessdate=2007-01-30 |publisher=National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc }}</ref> | |||

| When he was still an infant, his parents moved to the nearby town of ], where he grew up.<ref>H. G. Salsinger. "Ty Cobb Not Extraordinary Ballplayer as Boy." ''Bridgeport (CT) Telegram'', November 5, 1924, p. 18.</ref> By most accounts, he became fascinated with baseball as a child, and decided that he wanted to go professional one day; his father was vehemently opposed to this idea, but by his teenage years, he was trying out for area teams.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/sports-outdoor-recreation/ty-cobb-1886-1961|title=Ty Cobb (1886-1961)|website=New Georgia Encyclopedia}}</ref> He played his first years in organized baseball for the Royston Rompers, the semi-pro Royston Reds, and the ] of the ], who released him after only two days. He then tried out for the ] based ] of the semipro ], with his father's stern admonition ringing in his ears: "Don't come home a failure!"<ref name=Kanfer>{{cite magazine |last=Kanfer|first=Stefan| url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1050490-1,00.html | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070930072056/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1050490-1,00.html | url-status=dead | archive-date=September 30, 2007 |title=Failures Can't Come Home |date=April 18, 2005 |magazine=Time |access-date=February 26, 2007 }}</ref> After joining the Steelers for a monthly salary of $50, Cobb promoted himself by sending several postcards written about his talents under different aliases to ], the '']'' sports editor. Eventually, Rice wrote a small note in the ''Journal'' that a "young fellow named Cobb seems to be showing an unusual lot of talent."<ref>], p. 48.</ref> After about three months, Cobb returned to the Tourists and finished the season hitting .237 in 35 games. While with the Tourists he was mentored and coached by George Leidy, who emphasized pinpoint bunting and aggression on the basepaths.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rice |first=Stephen |date=April 21, 2023 |title=George Leidy |url=https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/george-leidy/ |access-date=April 23, 2023 |website=SABR bio project}}</ref> In August 1905, the management of the Tourists sold Cobb to the ]'s ] for $750 ({{Inflation|US|750|1905|fmt=eq}}).<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-733 |title=Ty Cobb |encyclopedia=New Georgia Encyclopedia |access-date=June 3, 2011 |archive-date=August 5, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130805214326/http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-733 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=2146324 |title= Cobb still revered, reviled 100 years after first game|agency= Associated Press|date= August 29, 2005}}</ref><ref name=NYTObit>{{cite news |title=Ty Cobb, Baseball Great, Dies; Still Held 16 Big League Marks|newspaper=The New York Times|pages=1, 21 |date=July 18, 1961 }}</ref><ref name=NYTWoolf>{{cite news |first=S. J. |last=Woolf |title=Tyrus Cobb – Then and Now; Once the scrappiest, wiliest figure in baseball, 'The Georgia Peach' views the game as played today with mellow disdain |newspaper=The New York Times|page= SM17 (Magazine section) |date=September 19, 1948 }}</ref><ref name=BaseballRefCobbCareerStats>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/c/cobbty01.shtml |title=Ty Cobb Career Statistics|access-date=May 19, 2021 |publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref> | |||

| On August 8, 1905, Cobb's mother, Amanda, fatally shot his father, William, with a pistol that William had purchased for her.<ref name="Gilbert"/> Court records indicate that William Cobb had suspected Amanda of infidelity<ref name="CobbInfidelity">{{cite web |url=http://blueridgecountry.com/articles/ty-cobb-murder-mystery |title=Ty Cobb: Death In The Dark|date=May 2003|access-date=June 23, 2010 |publisher=Blue Ridge Country }}</ref> and was sneaking past his own bedroom window to catch her in the act. She saw the silhouette of what she presumed to be an intruder and, acting in self-defense, shot and killed her husband.<ref name=Holmes2>{{cite book| last =Holmes | first=Dan |year=2004| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8Dm3hqzbyYkC&q=ty+cobb+4,189&pg=PA136 |title=Ty Cobb: A Biography| page=13 |publisher = Greenwood Publishing Group | isbn = 0-313-32869-2 |access-date=January 12, 2009 }}</ref> Amanda Cobb was charged with murder and released on a $7,000 ] ].<ref name=AmandCobbBond>{{cite court |litigants=State of Georgia vs. Amanda Cobb (bond hearing) |vol=vol2 |reporter=1281p.478 |opinion=9 |court=Franklin County, Georgia, Superior Court |date= September 29, 1905 |url=http://content.sos.state.ga.us/u?/adhoc,53}}</ref> She was ] on March 31, 1906.<ref name=AmandCobbVerdict>{{cite court |litigants=State of Georgia vs. Amanda Cobb (murder trial verdict) |vol=vol2 |reporter=1282p040 |opinion=1 |court=Franklin County, Georgia, Superior Court |date= March 31, 1906 |url=http://content.sos.state.ga.us/u?/adhoc,54}}</ref> Ty Cobb later attributed his ferocious play to his late father, saying, "I did it for my father. He never got to see me play ... but I knew he was watching me, and I never let him down." | |||

| Cobb's legacy as an athlete has sometimes been overshadowed by his surly temperament and aggressive reputation,<ref name=ESPNPage2>{{cite web | url=http://espn.go.com/page2/s/list/readers/dirtiest/players.html |title=Page 2 mailbag - Readers: Dirtiest pro players|accessdate=2007-01-30 |publisher=ESPN Internet Ventures }}</ref> which was described by the ] as "daring to the point of dementia."<ref name=NGECobb>{{cite web |url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-733 |title=Ty Cobb (1886-1961) |accessdate=2007-01-30 |last=Hill |first=John Paul |date=], ] |publisher= ] }}</ref> | |||

| Cobb was initiated into ] in 1907, earning the 32nd degree in 1912.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Co-Freemasonry |first=Masonic Order of Universal |title=Masonic Biographies {{!}} Ty Cobb |url=https://www.universalfreemasonry.org/en/famous-freemasons/ty-cobb |access-date=March 9, 2023 |website=Universal Co-Masonry |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=August 24, 2014 |title=Masons in Baseball |url=https://lodge43.org/masons-in-baseball/ |access-date=March 9, 2023 |website=Lodge No. 43, F. & A. M. |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ==Early life and baseball career== | |||

| Ty Cobb was born in ], ], in 1886 as the first of three children to Amanda Chitwood Cobb and William Herschel Cobb. | |||

| In 1911, Cobb moved to Detroit's architecturally significant and now historically protected ] neighborhood, from which he would walk with his dogs to the ballpark prior to games. The ] duplex in which Cobb lived still stands.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.grantland.com/story/_/id/6784662/ty-cobb-detroit |title=Ty Cobb as Detroit|work= Grantland.com |date=July 27, 2011|access-date=July 15, 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| Ty spent his first years in baseball as a member of the Royston Rompers, the semi-pro Royston Reds, and the Augusta Tourists of the ]. However, the Tourists cut Cobb two days into the season. He then went to try out for the Anniston Steelers of the semi-pro Tennessee-Alabama League, with his father's stern admonition still ringing in his ears: "Don't come home a failure." Cobb promoted himself by sending several postcards to ], the sports editor of the '']'' under several different aliases. Eventually, Rice wrote a small note in the ''Journal'' that a "young fellow named Cobb seems to be showing an unusual lot of talent."<ref name=KossuthMinors>{{cite web |last=Kossuth |first=James | url=http://wso.williams.edu/~jkossuth/cobb/minors.htm |title=Ty Cobb: The Minors |accessdate=2007-01-30 }}</ref> After about three months, Ty returned to the Tourists. He finished the season hitting .237 in 35 games. | |||

| ==Professional career== | |||

| August 1905 was an eventful month for Ty. The Tourists' management sold Cobb to the ]'s ] for ]750.<ref name=BaseballRefCobbCareerStats>{{cite web |url=http://www.baseball-reference.com/c/cobbty01.shtml |title=Ty Cobb Career Statistics|accessdate=2007-01-30 |publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref>. Additionally, On ], ], Ty's father was shot to death by Ty's mother. William Cobb suspected his wife of infidelity, and was sneaking past his own bedroom window to catch her in the act; she only saw the silhouette of what she presumed to be an intruder, and, acting in self-defense, shot and killed her husband.<ref name=KossuthWHCobb>{{cite web |last=Kossuth |first=James | url=http://wso.williams.edu/~jkossuth/cobb/dad.htm |title=William Herschel Cobb |accessdate=2007-01-30}}</ref> | |||

| == |

===Early years=== | ||

| Three weeks after his mother killed his father, Cobb debuted in ] for the Detroit Tigers. On August 30, 1905, in his first major league at bat, he doubled off ] of the ]. Chesbro had won 41 games the previous season. Cobb was 18 years old at the time, the youngest player in the league by almost a year.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/AL/1905-other-leaders.shtml |title=1905 American League Awards, All-Stars, & More Leaders|work= Baseball-Reference.com |access-date=October 8, 2010 }}</ref> Although he hit only .240 in 41 games, he signed a $1,500 contract to play for the Tigers in 1905.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://blogs.lib.msu.edu/red-tape/2017/aug/august-30-1905-ty-cobb-plays-his-first-game-detroit-tiger|title=August 30, 1905 : Ty Cobb Plays His First Game As Detroit Tiger {{!}} MSU Libraries|website=blogs.lib.msu.edu|access-date=January 28, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ====The early years==== | |||

| Three weeks after his mother killed his father, Cobb played center field for the Detroit Tigers. On ], ], in his first major league at-bat, Cobb doubled off the ]'s ]. That season, Cobb managed to bat only .240 in 41 games. Nevertheless, he showed enough promise as a rookie for the Tigers to give him a lucrative $1,500 contract for 1906. | |||

| As a rookie, Cobb was subject to severe hazing by his veteran teammates, who were jealous of the young prospect. The players smashed his homemade bats, nailed his cleats in the clubhouse, doused his clothes before tying knots in them, and verbally abused him.<ref>Russo, p. 17</ref> Cobb later attributed his hostile temperament to this experience: "These old-timers turned me into a snarling wildcat."<ref name=NGECobb>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-733 |title=Ty Cobb (1886–1961) |access-date=January 30, 2007 |last=Hill |first=John Paul |date=November 18, 2002 |encyclopedia=] |archive-date=August 5, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130805214326/http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-733 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Tigers manager ] later acknowledged that Cobb was targeted for abuse by veteran players, some of whom sought to force him off the team. "I let this go for a while because I wanted to satisfy myself that Cobb has as much guts as I thought in the very beginning," Jennings recalled. "Well, he proved it to me, and I told the other players to let him alone. He is going to be a great baseball player and I won't allow him to be driven off this club."<ref name="kashatus72-73">Kashatus (2002), pp. 72–73.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Although rookie hazing was customary, Cobb could not endure it in good humor, and he soon became alienated from his teammates. He later attributed his hostile temperament to this experience: "These old-timers turned me into a snarling wildcat."<ref name=NGECobb/> | |||

| The following year, 1906, Cobb became the Tigers' full-time center fielder and hit .316 in 98 games, setting a record for the highest batting average (minimum 310 plate appearances) for a 19-year-old (later bested by ]'s .322 average in 124 games for the 1928 ]).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/leaders_19_bat.shtml |title=Batting Leaders Before, During and After Age 19 |work=Baseball-Reference.com |access-date=October 8, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110930031332/http://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/leaders_19_bat.shtml |archive-date=September 30, 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> He never hit below that mark again. After being moved to right field, he led the Tigers to three consecutive ] in 1907, 1908 and 1909. Detroit would lose each ] (to the Cubs twice and then the Pirates); however, Cobb's ] numbers were far below his career standard. Cobb did not get another opportunity to play on a pennant-winning team. | |||

| In 1907, Cobb reached first and then stole second, third and home. He accomplished the feat four times during his career, still an MLB record as of 2022.<ref name=GeorgiaEncyc>{{cite encyclopedia|title=Ty Cobb|encyclopedia=The New Georgia Encyclopedia|url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-733|access-date=January 25, 2009|archive-date=August 5, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130805214326/http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-733|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Ty Cobb – Baseball Legend|publisher=BBC|date=July 22, 2003|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A1118648|access-date=January 25, 2009}}</ref> He finished the 1907 season with a league-leading .350 batting average, 212 hits, 49 steals and 119 ] (RBI).<ref name="BaseballRefCobbCareerStats"/> At age 20, he was the youngest player to win a ] and held this record until 1955, when fellow Detroit Tiger ] won the batting title while twelve days younger than Cobb had been.<ref name=GeorgiaEncyc/><ref name=BaseballDigest>{{cite web|url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FCI/is_11_59/ai_66010628 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080803081922/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FCI/is_11_59/ai_66010628 |url-status=dead |archive-date=August 3, 2008 |title=Facts and Figures – Baseball batting champions |access-date=January 25, 2009 |publisher=Baseball Digest |date=November 2000 }}</ref> Reflecting on his career in 1930, two years after retiring, he told ], "The biggest thrill I ever got came in a game against the Athletics in 1907 ... The Athletics had us beaten, with ] pitching. They were two runs ahead in the 9th inning, when I happened to hit a home run that tied the score. This game went 17 innings to a tie, and a few days later, we clinched our first pennant. You can understand what it meant for a 20-year-old country boy to hit a home run off the great Rube, in a pennant-winning game with two outs in the ninth."<ref name="baseballspast.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.baseballspast.com/film/cobb.html |title=Film from Baseball's Past |publisher=Baseballspast.com |date=March 19, 1930 |access-date=November 8, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| The following year (]) he became the Tigers' full-time center fielder and hit .316 in 98 games. He would never hit below that mark again. Cobb, firmly entrenched in center field, led the Tigers to three consecutive American League Pennants from 1907-1909. Detroit would lose each World Series, however, with Cobb's post-season numbers being much below his career standard. | |||

| ] during a World Series game between Detroit and Pittsburgh, 1909]] | |||

| In one notable ] game, Cobb reached first, stole second, stole third, and then stole home on consecutive attempts. He finished that season with a league high .350 batting average, 212 hits, 49 steals and 119 RBI. Despite great success on the field, Cobb was no stranger to controversy off it. At Spring Training in 1907, he fought a black groundskeeper over the condition of the Tigers' field in ]. Ty also ended up choking the man's wife when she intervened.<ref name=ESPNSchwartz>{{cite web |last=Schwartz|first=Larry | url=http://espn.go.com/sportscentury/features/00014142.html |title=He was a pain ... but a great pain |accessdate=2007-01-30 |publisher=ESPN Internet Ventures }}</ref> | |||

| Despite great success on the field, Cobb was no stranger to controversy off it. As described in '']'', "In 1907 during spring training in Augusta, Georgia, a black groundskeeper named Bungy Cummings, whom Cobb had known for years, attempted to shake Cobb's hand or pat him on the shoulder."<ref name="Gilbert"/> The "overly familiar greeting infuriated" Cobb, who attacked Cummings. When Cummings' wife tried to defend him, Cobb allegedly choked her. The assault was only stopped when catcher ] knocked Cobb out.<ref>''When Cobb Met Wagner: The Seven-Game World Series of 1909'' by David Finoli, McFarland, 2010, page 230.</ref> However, aside from Schmidt's statement to the press, no other corroborating witnesses to the assault on Cummings ever came forward and Cummings himself never made a public comment about it. Author Charles Leerhsen speculates that the assault on Cummings and his wife never occurred and that it was a total fabrication by Schmidt. Cobb had spent the previous year defending himself on several occasions from assaults by Schmidt, with Schmidt often coming out of nowhere to blindside Cobb. On that day, several reporters did see Cummings, who appeared to be "partially under the influence of liquor," approach Cobb and shout "Hello, Carrie!" (the meaning of which is unknown) and go in for a hug. Cobb then pushed him away, which was the last interaction that anyone saw between Cobb and Cummings. Shortly thereafter, hearing a fight, several reporters came running and found Cobb and Schmidt wrestling on the ground. When the fight was broken up and Cobb had walked away, Schmidt remained behind and told the reporters that he saw Cobb assaulting Cummings and his wife and had intervened. Leerhsen speculates that this was just another one of Schmidt's assaults on Cobb and that once discovered, Schmidt made up a story that made him sound like he had assaulted Cobb for a noble purpose.<ref>], pp. 151–152.</ref> In 1908, Cobb attacked a black laborer in Detroit who complained when Cobb stepped into freshly poured asphalt; Cobb was found guilty of battery, but the sentence was suspended.<ref name="Gilbert"/> | |||

| {{Quote box| | |||

| width=40% | |||

| |align=right | |||

| |quote=I always find that a drink of Coca-Cola between the games refreshes me to such an extent that I can start the second game feeling as if I had not been exercising at all, in spite of my exertions in the first. | |||

| |source=], <br>1907 '']'' newspaper ad <ref name=HallofFameCoke>{{cite web |url=http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/history/2002/021218_cobb_ty.htm |title=Ty Cobb Sold Me a Soda Pop: Hall of Fame Outfielder Ty Cobb and Coca-Cola |accessdate=2007-01-30 |last=Holmes |first=Dan |publisher=National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc }}</ref> | |||

| |}} | |||

| In September 1907, Cobb began a relationship with ] that |

In September 1907, Cobb began a relationship with ] that lasted the remainder of his life. By the time he died, he held over 20,000 shares of stock and owned ] in ], ], and ]. He was also a celebrity spokesman for the product.<ref name=HallofFameCoke>{{cite web|url=http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/history/2002/021218_cobb_ty.htm |title=Ty Cobb Sold Me a Soda Pop: Hall of Fame Outfielder Ty Cobb and Coca-Cola |access-date=January 30, 2007 |last=Holmes |first=Dan |publisher=National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061206111050/http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/history/2002/021218_cobb_ty.htm |archive-date=December 6, 2006 |url-status=dead }}</ref> In the offseason between 1907 and 1908, Cobb negotiated with ], offering to coach baseball there "for $250 a month, provided that he did not sign with Detroit that season." This did not come to pass, however.<ref>Bryan, Wright, "Clemson: An Informal History of the University 1889–1979," The R. L. Bryan Company, Columbia, South Carolina, 1979, Library of Congress card number 79-56231, {{ISBN|0-934870-01-2}}, page 214.</ref> | ||

| The following season, the Tigers |

The following season, the Tigers finished ahead of the ] for the pennant. Cobb again won the batting title with a .324 average, but Detroit suffered another loss in the World Series. In August 1908, Cobb married Charlotte ("Charlie") Marion Lombard, the daughter of prominent ] Roswell Lombard. In the offseason, the couple lived on her father's Augusta estate, ''The Oaks'', until they moved into their own house on Williams Street in November 1913.<ref name=Price1996>{{cite news|url=http://chronicle.augusta.com/history/cobb.html |title=Aggressive play defined Ty Cobb |access-date=February 7, 2007 |last=Price |first=Ed |date=June 21, 1996 |newspaper=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070209235657/http://chronicle.augusta.com/history/cobb.html |archive-date=February 9, 2007 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | ||

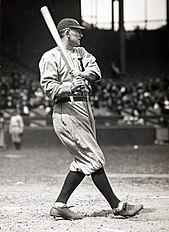

| ]'s famous picture of Cobb stealing third base during the 1909 season]] | |||

| The Tigers won the American League pennant again in ]. During the Series, Cobb stole home in the second game, igniting a three-run rally, but that was the high point for Cobb. He ended batting a lowly .231 in his last World Series, as the Tigers lost in seven games. Although he performed poorly in the post-season, Cobb won the ] by hitting .377 with 107 RBI and nine home runs - all ]. Cobb thus became the only player of the modern era to lead his league in home runs in a season without hitting a ball over the fence. | |||

| The Tigers won the AL pennant again in 1909. During that World Series, Cobb's last, he stole home in the second game, igniting a three-run rally, but that was the high point for him, finishing with a lowly .231, as the Tigers lost to Honus Wagner and the powerful Pirates in seven games. Although he performed poorly in the postseason, he won the ] by hitting .377 with 107 RBI and nine home runs, all ], thus becoming the only player of the modern era to lead his league in home runs in a season without hitting a ball over the fence.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.baseball-almanac.com/yearly/yr1909a.shtml|title=Year in Review: 1909 American League|access-date=May 28, 2007|publisher=Baseball Almanac}}</ref> | |||

| In the same season, ] snapped the famous photograph of a grimacing Cobb sliding into third base amid a cloud of dirt, which visually captured the grit and ferocity of his playing style.<ref name=conlon>{{cite web |url=http://www.sportingnews.com/archives/conlon/cobb/photo2.html |title=Ty Cobb |publisher=Times Mirror Co. |year=1998 |access-date=February 25, 2007 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070129000518/http://www.sportingnews.com/archives/conlon/cobb/photo2.html |archive-date=January 29, 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| ===1910: |

===1910: Chalmers Award controversy=== | ||

| {{Main|1910 Chalmers Award}} | {{Main|1910 Chalmers Award}} | ||

| Going into the final days of the 1910 season, Cobb had a .004 lead on ] for the American League batting title. The prize for the winner of the title was a ]. Cobb sat out the final two games to preserve his average. Lajoie hit safely eight times in a ] but six of those hits were ] singles. Later it was rumored that the opposing manager had instructed his third baseman to play extra deep to allow Lajoie to win the batting race over the generally disliked Cobb. Although Cobb was credited with a higher batting average, it was later discovered in the 1970s that one game had been counted twice so that Cobb actually lost to Lajoie. As a result of the incident, AL president ] was forced to ] the situation. He declared Cobb the rightful owner of the title, but car company president Hugh Chalmers chose to award one to both Cobb and Lajoie.<ref name="LoC">{{cite web |last1=Queen |first1=Mike |title=Embarrassing Baseball Scandals Fans Want to Forget |url=https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2023/07/embarrassing-baseball-scandals-fans-want-to-forget/ |website=Headlines and Heroes: Newspapers, Comics and More Fine Print |publisher=Library of Congress |access-date=August 17, 2023 |date=July 11, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Gillette|first=Gary|author2=Palmer, Pete|title=The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia|publisher=Sterling Publishing Co|location=New York|year=2007|edition=Fourth|pages=1764–1765|isbn=978-1-4027-4771-7}}</ref> | |||

| ===1911–1914=== | |||

| Going into the final days of the ] season, Cobb had a 4/10s of a percent lead on ] for the American League batting title. The prize for the winner of the title was a ]. Cobb sat out the final games to preserve his average. Nap Lajoie hit safely eight times in his teams' ]. However, six of those hits were bunt singles, and later came under scrutiny. Regardless, Cobb was credited with a higher batting average. Later baseball research (1980)showed Cobb erroneously was credited twice with a 2 for 4 game and, over the objections of Bowie Kuhn, the 1910 title was sensibly awarded retroactively to Nap Lajoie. | |||

| ] in Cleveland]] | |||

| {{further|1912 suspension of Ty Cobb}} | |||

| Cobb regarded baseball as "something like a war," future Tiger second baseman ] said. "Every time at bat for him was a crusade."<ref>{{cite book|last=Honig|first=Donald|title=Baseball When the Grass Was Real|publisher=]|year=1975|page=42|isbn=0-8032-7267-7}}</ref> Baseball historian ] said in the book ''Legends of the Fall'', "He is testament to how far you can get simply through will. ... Cobb was pursued by demons." | |||

| Cobb was having a tremendous year in 1911, which included a 40-game ]. Still, ] led him by .009 points in the batting race late in the season. Near the end of the season, Cobb's Tigers had a long series against Jackson's ]. Fellow Southerners Cobb and Jackson were personally friendly both on and off the field.<ref name="Russo 20">], p. 20.</ref> Cobb used that friendship to his advantage. Cobb ignored Jackson when Jackson tried to say anything to him. When Jackson persisted, Cobb snapped angrily back at him, making him wonder what he could have done to enrage Cobb. Cobb felt that it was these mind games that caused Jackson to "fall off" to a final average of .408, twelve points lower than Cobb's .420, a 20th-century record which stood until ] tied it and ] surpassed it with .424, the record since then (until 2024) except for Hugh Duffy's .438 in the 19th century.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb /> | |||

| As a result of the incident, ] was forced to ] the situation. He declared Cobb the rightful owner of the title. However, the Chalmers company elected to award a car to both of the players. | |||

| {{quote box|width=30%|align=left|quote=I often tried plays that looked recklessly daring, maybe even silly. But I never tried anything foolish when a game was at stake, only when we were far ahead or far behind. I did it to study how the other team reacted, filing away in my mind any observations for future use.|source=—Ty Cobb in '']''<ref name=NYTDaleyTribute>{{cite news |first=Arthur |last=Daley |author-link=Arthur Daley (sportswriter) |title=Sports of The Times: In Belated Tribute |page=32 (food fashions family furnishings section)|newspaper=]|date=August 15, 1961 }}</ref>}} | |||

| ===The 1911 season and onward=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Cobb was regarded not just as an athlete, but a psychological competitor. Cobb was having a typically fine year in ], which included a 40-game hitting streak. Still, ] had a .009 point lead on him in batting average. What happened next is discussed in Cobb's autobiography. Near the end of the season, Cobb’s Tigers had a long series against Jackson and the ]. Fellow Southerners, Cobb and Jackson were personally friendly both on and off the field. Cobb used that friendship for his advantage. However, Cobb suddenly ignored Jackson whenever Jackson said anything to him. When Jackson persisted, Cobb snapped angrily at Jackson, making him wonder what he could have done to enrage Cobb. As soon as the series was over, Cobb unexpectedly greeted Jackson and wished him well. Cobb felt that it was these mind games that caused Jackson to "fall off" to a final average of .408, while Cobb himself finished with a .420 average.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> | |||

| Cobb led the AL in numerous |

Cobb led the AL that year in numerous other categories, including 248 hits, 147 runs scored, 127 RBI, 83 stolen bases, 47 doubles, 24 triples and a .621 ]. Cobb hit eight home runs but finished second in that category to ], who hit eleven. He was awarded another Chalmers car, this time for being voted the AL MVP by the ]. | ||

| ] | |||

| The game that may best illustrate Cobb's unique combination of skills and attributes occurred on ], ]. Playing against the ], Cobb scored a run from first base on a single to right field, then scored another run from second base on a wild pitch. In the 7th inning, he tied the game with a 2-run double. The Yankee catcher began vociferously arguing the call with the umpire, going on at such length that the other Yankee infielders gathered nearby to watch. Realizing that no one on the Yankees had called time, Cobb strolled unobserved to third base, and then casually walked towards home plate as if to get a better view of the argument. He then suddenly slid into home plate for the game's winning run.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> | |||

| On May 12, 1911, playing against the ], he scored from first base on a single to right field, then scored another run from second base on a wild pitch. In the seventh inning, he tied the game with a two-run double. The Highlanders catcher vehemently argued the safe call at second base with the ] in question, going on at such length that the other Highlanders infielders gathered nearby to watch. Realizing that no one on the Highlanders had called time, Cobb strolled unobserved to third base and then casually walked towards home plate as if to get a better view of the argument. He then suddenly broke into a run and slid into home plate for the eventual winning run.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb /> It was performances like this that led ] to say later that Cobb "had brains in his feet."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/history/first5/default.htm |title=First Five: The Original Members of the Hall of Fame |last=Holmes |first=Dan |access-date=June 15, 2007 |publisher=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070608145751/http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/history/first5/default.htm |archive-date=June 8, 2007 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Describing his gameplay strategy in 1930, he said, "My system was all offense. I believed in putting up a mental hazard for the other fellow. If we were five or six runs ahead, I'd try some wild play, such as going from first to home on a single. This helped to make the other side hurry the play in a close game later on. I worked out all the angles I could think of, to keep them guessing and hurrying."<ref name="baseballspast.com" /> In the same interview, Cobb talked about having noticed a throwing tendency of first baseman ] but having to wait two full years until the opportunity came to exploit it. By unexpectedly altering his own ] tendencies, he was able to surprise Chase and score the winning run of the game in question. | |||

| On ], ], Cobb assaulted Claude Lueker, a heckler, in the stands in New York. Lueker and Cobb traded insults with each other throughout the first three innings, and the situation climaxed when Lueker called Cobb a "half-nigger." Cobb then climbed into the stands and attacked the handicapped Lueker, who due to an industrial accident had lost all of one hand and three fingers on his other hand. When onlookers shouted at Cobb to stop because the man had no hands, Cobb reportedly replied, "I don't care if he has no feet!" The league suspended him, and his teammates, though not fond of Cobb, went on strike to protest the suspension prior to the ] game in Philadelphia. For that one game, Detroit fielded a replacement team made up of college and sandlot ballplayers, plus two Detroit coaches, and lost, 24-2. Some of major league baseball's all-time negative records were established in this game, notably the 26 hits allowed by ], who pitched the sport's most unlikely complete game. The strike ended when Cobb urged his teammates to return to the field.<ref name=KossuthPartIII>{{cite web |last=Kossuth |first=James | url=http://wso.williams.edu/~jkossuth/cobb/race.htm |title=How Cobb Got Along With Others: Part 3: Ty and Those Outside Baseball |accessdate=2007-01-30}}</ref> | |||

| On May 15, 1912, Cobb assaulted a heckler, Claude Lucker (often misspelled as Lueker), in the stands in New York's ] where the Tigers were playing the Highlanders. Lucker, described by baseball historian Frank Russo as "a ] lackey and two-bit punk," often berated Cobb when Detroit visited New York.<ref name="Russo 19">], p. 19.</ref> In this game, the two traded insults through the first couple of innings. Cobb at one point went to the Highlander dugout to look for the Highlanders' owner to try to have Lucker ejected from the game, but his search was in vain.<ref>], p. 259.</ref> He also asked for the police to intervene, but they refused.<ref name="Russo 19"/> The situation climaxed when Lucker allegedly called Cobb a "half-nigger."<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8Dm3hqzbyYkC|first=Dan |last=Holmes|title=Ty Cobb: A Biography |year=2004 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |location=Westport, Connecticut |page=58|isbn=978-0-313-32869-5}}</ref> Cobb, in his discussion of the incident in the Holmes biography,<ref>], pp. 131–135.</ref> avoided such explicit words but alluded to Lucker's epithet by saying he was "reflecting on my mother's color and morals." He went on to state that he warned Highlander manager ] that if something was not done about that man, there would be trouble. No action was taken. At the end of the sixth inning, after being challenged by teammates ] and ] to do something about it, Cobb climbed into the stands and attacked Lucker, who it turned out was handicapped (he had lost all of one hand and three fingers on his other hand in an industrial accident). Some onlookers shouted at him to stop because the man had no hands, to which Cobb reportedly retorted, "I don't care if he got no feet!"<ref>{{cite web |title=ESPN.com's 10 infamous moments |url=https://www.espn.com/endofcentury/s/other/infamous.html |access-date=August 26, 2007}}</ref> According to Russo, the crowd cheered Cobb on in the fight.<ref name="Russo 19"/> Though extremely rare in the 21st century, attacking fans was not so unusual an activity in the early years of baseball. Other notable baseball stars who assaulted heckling fans include ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>], p. 258.</ref> | |||

| During Cobb's career, he was involved in numerous fights, both on and off the field, and several profanity-laced shouting matches. For example, Cobb and umpire ] arranged to settle their in-game differences with a fistfight, to be conducted under the grandstand after the game. Members of both teams were spectators, and broke up the scuffle after Cobb had knocked Evans down, pinned him, and began choking him. Cobb once slapped a black elevator operator for being "uppity." When a black night watchman intervened, Cobb pulled out a knife and stabbed him (The matter was later settled out of court)."<ref name=NGECobb/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ===1915-1921=== | |||

| The league ]. His teammates, though not fond of Cobb, went on strike to protest the suspension, and the lack of protection of players from abusive fans, before the May 18 game in Philadelphia. For that one game, Detroit fielded a ] made up of hastily recruited college and sandlot players plus two Tiger coaches and lost 24–2, thereby setting some of Major League Baseball's modern-era (post-1900) negative records, notably the 26 hits in a nine-inning game allowed by ], who pitched one of the sport's most unlikely ]s.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTravers>{{cite web|url=http://www.baseballlibrary.com/ballplayers/player.php?name=Al_Travers_1892&page=chronology|title=Al Travers from the Chronology|last=Charlton|first=James|access-date=June 15, 2007|publisher=BaseballLibrary.com|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923182449/http://www.baseballlibrary.com/ballplayers/player.php?name=Al_Travers_1892&page=chronology|archive-date=September 23, 2015}}</ref> The pre-1901 record for the most hits and runs given up in a game is held by the ]' ]. Primarily an outfielder, Rowe pitched a complete game on July 24, 1882, giving up 35 runs on 29 hits.<ref>{{cite web|title=1882 Year in Review|url=http://www.baseball-almanac.com/yearly/yr1882n.shtml|website=Baseball Reference}}</ref> The current post-1900 record for most hits in a nine-inning game is 31, set in 1992 by the Milwaukee Brewers against Toronto; however, the Blue Jays used six pitchers.<ref>{{cite web|title=Milwaukee gets 31 hits|url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/TOR/TOR199208280.shtml|website=Baseball Reference}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1915, Cobb set the single season steals record when he stole 96 bases. That record stood until ] broke it in 1962. Cobb’s streak of five batting titles (believed at the time to be nine straight) ended the following year when he finished second with .371 to ]’s .386. | |||

| The strike ended when Cobb urged his teammates to return to the field. According to him, this incident led to the formation of a players' union, the "Ballplayers' Fraternity" (formally, the Fraternity of Professional Baseball Players of America), an early version of what is now called the ], which garnered some concessions from the owners.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|title=Baseball Players' Fraternity|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/54781/Baseball-Players-Fraternity|access-date=January 25, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| In 1917, Cobb hit in 35 consecutive games; he remains the only player with two 35-game hitting streaks to his credit (Cobb had a 40-game hitting streak in 1911). Over his career, Cobb had six hitting streaks of at least 20 games, second only to ]'s seven. | |||

| During his career, Cobb was involved in numerous other fights, both on and off the field, and several profanity-laced shouting matches. For example, Cobb and umpire ] arranged to settle their in-game differences through fisticuffs under the grandstand after the game. Members of both teams were spectators, and broke up the scuffle after Cobb had knocked Evans down, pinned him and began choking him. In 1909, Cobb was arrested for assault for an incident that occurred in a Cleveland hotel. Cobb got into an argument with the elevator operator around 2:15 a.m. when the man refused to take him to the floor where some of his teammates were having a card game. The elevator operator stated that he could only take Cobb to the floor where his room was. As the argument escalated, a night watchman approached and he and Cobb eventually got into a physical confrontation. During the fight, Cobb produced a penknife and slashed the watchman across the hand. Cobb later claimed that the watchman, who had the upper hand in the fight, had his finger in Cobb's left eye and that Cobb was worried he was going to have his sight ruined. The fight finally ended when the watchman produced a gun and struck Cobb several times in the head, knocking him out.<ref>], p. 218.</ref> Cobb would later plead guilty to simple assault and pay a $100 fine. This incident has often been retold with the elevator operator and the watchman both being black. However, recent scholarship has shown that all parties involved were white.<ref>], pp. 219–220.</ref> | |||

| Also in 1917, Cobb starred in the motion picture '']''. Based on a story by sports columnist Grantland Rice, the film casts Cobb as "himself", a small-town Georgian bank clerk with a talent for baseball. | |||

| On August 13, 1912, the same day the Tigers were to play the ] at ], Cobb and his wife were driving to a train station in ] that was to transport him to the game when three intoxicated men had stopped him on the way. When Cobb had gotten out of the car to confront the men, they had asked for money and instigated a physical fight, with Cobb defending himself from one of the men by punching him in the chin as another had fled the scene. After being grabbed by the neck by another man, the man had pulled a knife and stabbed him in the back before he forced him away and returned to his car to continue driving to the station for the game. Cobb refused to speak any further of the issue. He would go on to hit 2–3 with two singles and a run scored, as well as batting .418. The Tigers lost 2–3.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Press Democrat 13 August 1912 — California Digital Newspaper Collection |url=https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SRPD19120813.2.9&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22Ty+Cobb%22------- |access-date=May 1, 2023 |website=cdnc.ucr.edu}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Detroit Tigers vs New York Highlanders Box Score: August 13, 1912 |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA191208130.shtml |access-date=May 1, 2023 |website=Baseball-Reference.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| By ], ] had established himself as a power hitter, something Cobb was not considered. When Cobb and the Tigers showed up in New York to play the Yankees for the first time that season, writers billed it as a showdown between two stars of competing styles of play. Ruth hit two homers and a triple during the series, compared to Cobb's one single. | |||

| In 1913, Cobb signed a contract worth $12,000 for the six-month season ({{Inflation|US|12000|1913|fmt=eq}}), making him likely the first baseball player in history to be paid a five-figure salary.<ref name="salary milestones">{{cite news |last1=Haupert |first1=Michael |title=Baseball's Major Salary Milestones |url=https://sabr.org/research/baseball-s-major-salary-milestones |access-date=October 21, 2019 |work=The Baseball Research Journal |publisher=] |date=Fall 2011}}</ref> This occurred in the same year where Cobb had allegedly grown pessimistic and was quoted as saying: "It seems I am a burden to the Detroit club, as a trespasser of its rules. If that be the case, let ] put a price on me and I'll take a chance on being able to negotiate my own release. I don't think I shall ever play ball again. This is positively my last statement in this matter." This attributed statement was first published on an April 19, 1913, edition of the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Los Angeles Herald 19 April 1913 — California Digital Newspaper Collection |url=https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19130419.2.101&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22Ty+Cobb%22------- |access-date=May 1, 2023 |website=cdnc.ucr.edu}}</ref> Cobb did not play that day as the Tigers won 4–0 against the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=St. Louis Browns vs Detroit Tigers Box Score: April 19, 1913 |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/DET/DET191304190.shtml |access-date=May 1, 2023 |website=Baseball-Reference.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| As Ruth's popularity grew, Cobb became increasingly hostile toward him. Cobb saw Ruth not only as a threat to his style of play, but also to his style of life. While Cobb preached ascetic self-denial, Ruth gorged on hot dogs, beer, and women. Perhaps what angered him the most about Ruth was that despite Ruth's total disregard for his physical condition and traditional baseball, he was still an overwhelming success and brought fans to the ballparks in record numbers to see him set his own records. | |||

| In June 1914, Cobb pleaded guilty to disturbing the peace after pulling a revolver during an argument at a Detroit butcher shop. He was fined $50 ({{Inflation|US|50|1914|fmt=eq}}).<ref>{{cite news |title=Ty Cobb Fined $50 |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/94500942/ty-cobb-fined-50/ |access-date=February 9, 2022 |work=] |date=June 25, 1914 |pages=1}}</ref> | |||

| After enduring several years of seeing his fame and notoriety usurped by Ruth, Cobb decided that he was going to show that swinging for the fences was no challenge for a top hitter. On ], ], Cobb began a two-game hitting spree better than any even Ruth had unleashed. He was sitting in the dugout talking to a reporter and told him that, for the first time in his career, he was going to swing for the fences. That day, Cobb went 6 for 6, with two singles, a double, and three home runs. His 16 total bases set a new AL record. The next day he had three more hits, two of which were home runs. His single his first time up gave him 9 consecutive hits over three games. His five homers in two games tied the record set by ] of the old Chicago NL team in 1884. Cobb wanted to show that he could hit home runs when he wanted, but simply chose not to do so. At the end of the series, 38-year-old Cobb had gone 12 for 19 with 29 total bases, and then went happily back to bunting and hitting-and-running. For his part, Ruth's attitude was that "I could have had a lifetime .600 average, but I would have had to hit them singles. The people were paying to see me hit home runs." | |||

| ===1915–1921=== | |||

| On ], ], in the second game of a double header against ] of the ], Cobb collected his 3,000th hit. | |||

| In 1915, Cobb set the single-season record for stolen bases with 96, which stood until Dodger ] broke it in 1962.<ref name=BaseballRefSeasonSB>{{cite web |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/SB_season.shtml |title=Single-Season Leaders for Stolen Bases |access-date=February 7, 2007 |publisher=Sports Reference, Inc }}</ref> That year, he also won his ninth consecutive batting title, hitting .369. | |||

| During 1917 spring training, Cobb showed up late for a ] spring training doubleheader against the New York Giants because of a golf outing. Several of the Giants, including ], called him names from the bench. Cobb retaliated by ] Herzog during the second game, prompting a ] in which Cobb ground Herzog's face in the dirt. The Dallas Police Department had to help stop the brawl, and Cobb was thrown out of the game.<ref name="Herzog SABR">{{cite web|last=Schechter|first=Gabriel|url=https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/buck-herzog/|title=Buck Herzog|work=SABR|access-date=April 26, 2021}}</ref><ref>], pp. 124-125.</ref> Both teams were staying at the Oriental Hotel, and at dinner that evening, Herzog walked up to Cobb and challenged him to a fight. The two met an hour later in Cobb's room, where the Tiger outfielder had prepared for the fight by moving furniture out of the way and pouring water on the floor. Cobb's leather-soled shoes enabled him to get better footing than Herzog, who wore tennis shoes. The fight lasted for thirty minutes, over the course of which Cobb knocked down Herzog about six times while Herzog only knocked Cobb down once. The scuffle left Herzog's face bloodied and his eyes nearly shut.<ref name="Herzog SABR"/><ref name="Russo 125">], p. 125.</ref> With Herzog vowing revenge, Cobb skipped the rest of the exhibition series against the Giants, heading to Cincinnati to train with the Reds, who were managed by Cobb's friend ]. However, Cobb later expressed the deepest respect for Herzog because of the way the infielder had conducted himself in the fight.<ref name="Russo 125"/> | |||

| In 1917, Cobb hit in 35 consecutive games, still the only player with two 35-game hitting streaks (including his 40-game streak in 1911).<ref name=BaseballAlmanacLongHitStreaks>{{cite web |url=http://www.baseball-almanac.com/feats/feats-streak.shtml|title=Consecutive Games Hitting Streaks |access-date=June 6, 2007|publisher=Baseball Almanac}}</ref> He had six hitting streaks of at least 20 games in his career, second only to ]'s eight.<ref name=BaseballPageRose>{{cite web |url=http://www.thebaseballpage.com/players/rosepe01.php |title=Player Pages: Pete Rose |access-date=February 7, 2007}}</ref> | |||

| Also in 1917, Cobb starred in the motion picture '']'' for a sum of $25,000 plus expenses (equivalent to approximately ${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|25000|1917|r=-3}}}} today{{inflation-fn|US}}). Based on a story by sports columnist ], the film casts Cobb as "himself," a small-town Georgia bank clerk with a talent for baseball.<ref name=IMDB>{{cite web |url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0158971/ |title=Somewhere in Georgia |publisher=] |access-date=February 7, 2007 }}</ref> ] critic ] called the movie "absolutely the worst flicker I ever saw, pure hokum." | |||

| {{multiple image| | |||

| |align = left | |||

| |direction = horizontal | |||

| |total_width = 350 | |||

| |image2 = Cobbruth.jpg | |||

| |caption2 = ] (left) and Ty Cobb in 1920 | |||

| |image1 = Ty Cobb Paul Thompson, c1918.jpg | |||

| |caption1 = Cobb circa 1918 | |||

| |footer = | |||

| }} | |||

| In October 1918, Cobb enlisted in the ] branch of the ] and was sent to the ] headquarters in ].<ref name=ChemicalCorps>{{cite journal|last=Gurtowski |first=Richard |date=July 2005 |title=Remembering baseball hall of famers who served in the Chemical Corps |journal=CML Army Chemical Review |url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0IUN/is_2005_July/ai_n15730920 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060222165016/http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0IUN/is_2005_July/ai_n15730920 |url-status=dead |archive-date=February 22, 2006 |access-date=March 10, 2007 }}</ref> He served approximately 67 days overseas before being ] and returning to the United States.<ref name=ChemicalCorps/> He was given the rank of captain underneath the command of Major ], the president of the ]. Other baseball players serving in this unit included Captain Christy Mathewson and Lieutenant ].<ref name=ChemicalCorps/> All of these men were assigned to the Gas and Flame Division, where they trained soldiers in preparation for ] by exposing them to gas chambers in a controlled environment,<ref name=ChemicalCorps/> which eventually caused Mathewson to contract the tuberculosis that killed him on the eve of the 1925 World Series. | |||

| On August 19, 1921, in the second game of a doubleheader against ] of the ], Cobb collected his 3,000th hit. Aged 34 at the time, he is still the youngest ballplayer to reach that milestone, and in the fewest at-bats (8,093).<ref name=SportingNews08061999>{{cite web|url=http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/exhibits/online_exhibits/3000_hit_club/cobb_ty.htm |title=The 3000 Hit Club: Ty Cobb |access-date=February 10, 2007 |publisher=National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070209031106/http://www.baseballhalloffame.org/exhibits/online_exhibits/3000_hit_club/cobb_ty.htm |archive-date=February 9, 2007 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name=HallofFameCobb3000>{{cite magazine|url=http://www.sportingnews.com/archives/sports2000/numbers/172730.html |date=August 6, 1999 |title=Inside the numbers: 3,000 hits |access-date=February 10, 2007 |magazine=] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050211195538/http://www.sportingnews.com/archives/sports2000/numbers/172730.html |archive-date=February 11, 2005 }}</ref> | |||

| By 1920, ], sold to the renamed ] from the ], had established himself as a power hitter, something Cobb was not considered to be. When his Tigers showed up in New York to play the Yankees for the first time that season, writers billed it as a showdown between two stars of competing styles of play. Ruth hit two homers, a triple, and two singles during the series, compared to Cobb's two hits of a double and a single.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Detroit Tigers vs New York Yankees Box Score: May 24, 1920 |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA192005240.shtml |access-date=March 29, 2023 |website=Baseball-Reference.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Detroit Tigers vs New York Yankees Box Score: May 25, 1920 |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA192005250.shtml |access-date=March 29, 2023 |website=Baseball-Reference.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Detroit Tigers vs New York Yankees Box Score: May 26, 1920 |url=https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA192005260.shtml |access-date=March 29, 2023 |website=Baseball-Reference.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| As Ruth's popularity grew, Cobb became increasingly hostile toward him. He saw the Babe not only as a threat to his style of play, but also to his style of life.<ref name=Nation05082006>{{cite web |url=http://www.thenation.com/doc/20060522/zirin |last=Zirin |first=Dave |title=Bonding With the Babe |work=] |date=May 8, 2006 |access-date=March 1, 2007 }}</ref><ref name=MF112006>{{cite web|url=http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1608/is_9_20/ai_n6244977 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050120092744/http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1608/is_9_20/ai_n6244977 |url-status=dead |archive-date=January 20, 2005 |last=Kalish |first=Jacob |title=Fat phenoms: are hot dogs and beer part of your training regimen? Maybe they should be |publisher=] |date=October 2004 |access-date=March 1, 2007 }}</ref><ref name=SPTimes>{{cite news |url=http://www.sptimes.com/2004/03/21/Floridian/Thanks__Babe.shtml |last=Klinkenberg |first=Jeff |title=Thanks, Babe |newspaper=] |date= March 24, 2004 |access-date=March 1, 2007 }}</ref> Perhaps what angered him the most about Ruth was that despite Babe's total disregard for his physical condition and traditional baseball, he was still an overwhelming success and brought fans to the ballparks in record numbers to see him challenge his own slugging records.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Bisher|first1=Furman|title=A Visit with Ty Cobb|journal=Saturday Evening Post|date=1958|volume=230|issue=50|page=42|url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=19509173&site=eds-live&scope=site|access-date=February 27, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| On May 5, 1925, Cobb told a reporter that, for the first time in his career, he was going to try to hit home runs, saying he wanted to show that he could hit home runs but simply chose not to. That day, he went 6 for 6, with two singles, a double and three homers.<ref name=BaseballLibMay1925>{{cite web |url=http://www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/chronology/1925MAY.stm |title=May 1925 |access-date=February 8, 2007 |publisher=Baseballlibrary.com |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923224657/http://www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/chronology/1925MAY.stm |archive-date=September 23, 2015 }}</ref> The 16 total bases set a new AL record, which stood until May 8, 2012, when ] of the ] hit four home runs and a double for a total of 18 bases.<ref>{{cite web|work=Baseball Almanac|url=http://www.baseball-almanac.com/recbooks/total_bases_records.shtml|title= Total Bases Records|access-date=May 9, 2012}}</ref> The next day Cobb had three more hits, two of which were home runs. The single his first time up gave him nine consecutive hits over three games, while his five homers in two games tied the record set by ] of the old Chicago NL team in 1884.<ref name=BaseballLibMay1925/> By the end of the series Cobb had gone 12 for 19 with 29 total bases, and afterwards reverted to his old playing style. Even so, when asked in 1930 by ] to name the best hitter he'd ever seen, Cobb answered, "You can't beat the Babe. Ruth is one of the few who can take a terrific swing and still meet the ball solidly. His timing is perfect. the combined power and eye of Ruth."<ref name="baseballspast.com"/> | |||

| ===Cobb as player/manager=== | ===Cobb as player/manager=== | ||

| ] at ], August 16, 1924]] | |||

| ], the Detroit Tigers owner, signed Cobb to take over for ] as manager for the ] season. Cobb signed the deal on his 34th birthday for $32,500. To say the least, the signing caught the baseball world off-guard. Universally disliked (even by the members of his own team) but a legendary player, Cobb's management style left a lot to be desired. He expected as much from his players as he gave, and most of the men did not meet his standard. | |||

| Tigers owner ] tapped Cobb to take over for Hughie Jennings as manager for the 1921 season, a deal he signed on his 34th birthday for $32,500 (equivalent to approximately ${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|32500|1921|r=0}}}} in today's terms{{inflation-fn|US}}). The signing surprised the baseball world. Although Cobb was a legendary player, he was disliked throughout the baseball community, even by his own teammates.<ref name=ngeorgiacobb>{{cite web |url=http://ngeorgia.com/people/cobbt.html |title=Tyrus Raymond "Ty" Cobb: a North Georgia Notable |publisher=About North Georgia |access-date=February 27, 2007 |archive-date=January 26, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070126120456/http://ngeorgia.com/people/cobbt.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| The closest |

The closest Cobb came to winning another pennant was in 1924, when the Tigers finished in third place, six games behind the pennant-winning ]. The Tigers had also finished third in 1922, but 16 games behind the Yankees. Cobb blamed his lackluster managerial record (479 wins against 444 losses) on Navin, who was arguably even more frugal than he was, passing up several quality players Cobb wanted to add to the team. In fact, he had saved money by hiring Cobb to both play and manage. | ||

| In 1922, Cobb tied a batting record set by ], with four five-hit games in a season. This has since been matched by ], ] and ]. On May 10, 1924, Cobb was honored at ceremonies before a game in Washington, D.C., by more than 100 dignitaries and legislators. He received 21 books, one for each year in professional baseball.<ref>{{cite book|last=Salsinger|first=H.G.|title=Ty Cobb|year=2012|publisher=McFarland|location=US|isbn=978-0-7864-6546-0|page=162|url=http://www.mcfarlandpub.com/book-2.php?id=978-0-7864-6546-0|archive-url=https://archive.today/20130128090001/http://www.mcfarlandpub.com/book-2.php?id=978-0-7864-6546-0|url-status=dead|archive-date=January 28, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Cobb blamed his lackluster managerial record (479 wins-444 losses) on Navin, who was arguably an even bigger ] than Cobb. Navin passed up a number of quality players that Cobb wanted to add to the team. In fact, Navin had saved money by hiring Cobb to manage the team. | |||

| At the end of 1925, Cobb was again embroiled in a batting title race, this time with one of his teammates and players, ]. In a doubleheader against the ] on October 4, 1925, Heilmann got six hits to lead the Tigers to a sweep of the doubleheader and beat Cobb for the batting crown, .393 to .389. Cobb and Browns player-manager ] each pitched in the final game, Cobb pitching a perfect inning. | |||

| Also in 1922, Cobb tied a batting record set by ], with four five-hit games. This has since been matched by ], ] and ]. | |||

| ====Managerial record==== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="font-size: 95%; text-align:center;" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! rowspan="2"|Team !! rowspan="2"|Year !! colspan="5"|Regular season !! colspan="4"|Postseason | |||

| |- | |||

| !Games!!Won!!Lost!!Win %!!Finish!! Won !! Lost !! Win % !! Result | |||

| |- | |||

| |- | |||

| !]|| {{mlby|1921}} | |||

| ||153||{{WinLossPct|71|82}}|| 6th in AL || – || – || – || | |||

| |- | |||

| !]|| {{mlby|1922}} | |||

| ||154||{{WinLossPct|79|75}}|| 3rd in AL || – || – || – || | |||

| |- | |||

| !]|| {{mlby|1923}} | |||

| ||154||{{WinLossPct|83|71}}|| 2nd in AL || – || – || – || | |||

| |- | |||

| !]|| {{mlby|1924}} | |||

| ||154||{{WinLossPct|86|68}}|| 3rd in AL || – || – || – || | |||

| |- | |||

| !]|| {{mlby|1925}} | |||

| ||154||{{WinLossPct|81|73}}|| 4th in AL || – || – || – || | |||

| |- | |||

| !]|| {{mlby|1926}} | |||

| ||154||{{WinLossPct|79|75}}|| 6th in AL || – || – || – || | |||

| |- | |||

| ! colspan="2"|Total ||923||{{WinLossPct|479|444}}|| || {{WinLossPct|0|0}} || | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Move to Philadelphia=== | |||

| At the end of 1925 Cobb was once again embroiled in a batting title race, this time with one of his teammates and players, ]. In a doubleheader against the ] on ], ], Heilmann got six hits, leading the Tigers to a sweep of the doubleheader and beating Cobb for the batting crown, .393 to .389. Cobb and Browns manager ] each pitched in the final game. Cobb pitched a perfect inning. | |||

| Cobb announced his retirement after a 22-year career as a Tiger in November 1926, and headed home to ].<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> Shortly thereafter, Tris Speaker also retired as player-manager of the ]. The retirement of two great players at the same time sparked some interest, and it turned out that the two were coerced into retirement because of allegations of game-fixing brought about by ], a former pitcher managed by Cobb.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite web|url=https://baseballbiography.com/ty-cobb-1886|title=Ty Cobb|access-date=November 24, 2007|publisher=baseballbiography.com}}</ref> | |||

| ], ], Cobb, and ], 1928]] | |||

| ===Cobb moves to Philadelphia=== | |||

| Leonard accused former pitcher and outfielder ] and Cobb of betting on a Tigers–Indians game played in Detroit on September 25, 1919, in which they allegedly orchestrated a Tigers victory to win the bet. Leonard claimed proof existed in letters written to him by Cobb and Wood.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> Commissioner ] held a secret hearing with Cobb, Speaker and Wood.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> A second secret meeting among the AL directors led to the unpublicized resignations of Cobb and Speaker; however, rumors of the scandal led Judge Landis to hold additional hearings<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> in which Leonard refused to participate. Cobb and Wood admitted to writing the letters, but claimed that a horse-racing bet was involved and that Leonard's accusations were in retaliation for Cobb's having released him from the Tigers, thereby demoting him to the ].<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> Speaker denied any wrongdoing.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> | |||

| Cobb finally called it quits from a 22-year career as a Tiger in November ]. He announced his retirement and headed home to Augusta, Georgia. Shortly thereafter, Tris Speaker also retired as player-manager of the Cleveland team. The retirement of two great players at the same time sparked some interest, and it turned out that the two were coerced into retirement because of allegations of game-fixing brought about by ], a former pitcher of Cobb's. | |||

| On January 27, 1927, Judge Landis cleared Cobb and Speaker of any wrongdoing because of Leonard's refusal to appear at the hearings.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> Landis allowed both Cobb and Speaker to return to their original teams, but each team let them know that they were ]s and could sign with any club they wanted.<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> Speaker signed with the ] for 1927, and Cobb with the ]. Speaker then joined Cobb in Philadelphia for the 1928 season. Cobb said he had come back only to seek vindication and say he left baseball on his own terms. | |||

| Leonard was unable to convince either ] or the public that the two had done anything for which they deserved to be kicked out of baseball. | |||

| Cobb played regularly in 1927 for a young and talented team that finished second to one of the greatest teams of all time, the 110–44 1927 Yankees, returning to Detroit to a tumultuous welcome on May 10 and doubling his first time up to the cheers of Tigers fans. On July 18, Cobb became the first member of the ] when he doubled off former teammate ], still pitching for the Tigers, at ].<ref name=BaseballLibraryTyCobb/> | |||

| Landis allowed both Cobb and Speaker to return to their original teams, but each team let them know that they were free agents and could sign with whomever they wished. Speaker signed with the ] for ]; Cobb signed with the ]. Speaker then joined Cobb in Philadelphia for the ] season. Cobb says he came back only to seek vindication and so that he could say he left baseball on his own terms. | |||