| Revision as of 11:47, 12 December 2019 view source2600:1015:b11f:1f67:dd7b:13ec:5962:a79d (talk) Undid revision 930426421 by Chewings72 (talk)Tags: Undo Non-autoconfirmed user rapidly reverting edits← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:20, 11 January 2025 view source Citation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,458,147 edits Added date. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients | #UCB_Category 336/703 | ||

| (659 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American politician and military officer (1909–1998)}} | |||

| {{pp-protected|small=yes}} | |||

| {{redirect|Goldwater}} | {{redirect|Goldwater}} | ||

| {{about|the |

{{about|the United States Senator and Presidential nominee|his son|Barry Goldwater Jr.}} | ||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{short description|Republican nominee for President, 1964; U.S. Senator from Arizona}} | |||

| {{use American English|date=April 2019}} | {{use American English|date=April 2019}} | ||

| {{ |

{{Use mdy dates|date=November 2024}} | ||

| {{Infobox officeholder | {{Infobox officeholder | ||

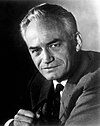

| | image = Senator Goldwater 1960.jpg | |||

| | name = Beehive F*cker | |||

| | |

| caption = Senate portrait, 1960 | ||

| | jr/sr = United States Senator | |||

| | office = Chair of the ] | |||

| | state = ] | |||

| | term_start = January 3, 1985 | |||

| | |

| term_start = January 3, 1969 | ||

| | term_end = January 3, 1987 | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | |

| predecessor = ] | ||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | office1 = Chair of the ] | |||

| | term_start1 = January 3, |

| term_start1 = January 3, 1953 | ||

| | term_end1 = January 3, |

| term_end1 = January 3, 1965 | ||

| | predecessor1 = ] | | predecessor1 = ] | ||

| | successor1 = ] | | successor1 = ] | ||

| | office2 = Chair of the ] | |||

| | jr/sr2 = United States Senator | |||

| | term_start2 = January 3, 1985 | |||

| | state2 = ] | |||

| | |

| term_end2 = January 3, 1987 | ||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | term_end2 = January 3, 1987 | |||

| | |

| successor2 = ] | ||

| | office3 = Chair of the ] | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | term_start3 = January 3, |

| term_start3 = January 3, 1981 | ||

| | term_end3 = January 3, |

| term_end3 = January 3, 1985 | ||

| | predecessor3 = ] | | predecessor3 = ] | ||

| | successor3 = ] | | successor3 = ] | ||

| | office4 = Member of the ]<br />from the at-large district | |||

| | birth_name = Barry Morris Goldwater | |||

| | term_start4 = 1950 | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1909|1|2}} | |||

| | term_end4 = 1952 | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], U.S. | |||

| | birth_name = Barry Morris Goldwater | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1998|5|29|1909|1|2}} | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1909|1|2}} | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | birth_place = {{nowrap|], ], U.S.}} | |||

| | party = ] | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1998|5|29|1909|1|2}} | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|Margaret Johnson|1934|1985|end=died}}<br />{{marriage|Susan Shaffer Wechsler|1992}} | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | children = 4, including ] | |||

| |resting_place=Christ Church of the Ascension <br/> Paradise Valley, Arizona, U.S. | |||

| | education = ] | |||

| | party = ] | |||

| | signature = Sigggggggfinal.svg | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| | allegiance = {{flag|United States|1912}} | |||

| * {{marriage|Margaret Johnson|1934|1985|end=died}} | |||

| | branch = {{army|United States}} (1941–1947)<br />{{air force|United States}} (1947–1967) | |||

| * {{marriage|Susan Shaffer Wechsler|1992}}}} | |||

| | serviceyears = 1941–1945 (USAAF)<br />1945–1952 (ANG)<br />1952–1967 (USAFR) | |||

| | children = 4, including ] | |||

| | rank = ] ] (USAAF)<br />] ] (ANG)<br />] ] (USAFR) | |||

| | education = ] (did not graduate) | |||

| | unit = ]<br />]<br />] | |||

| | signature = Barry Goldwater signature.svg | |||

| | battles = ]<br />] | |||

| | branch = {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| | serviceyears = 1941–1967 | |||

| | rank = ] | |||

| | battles = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]}} | |||

| | module = {{Listen|pos=center|embed=yes|filename=|title=Barry Goldwater's voice|type=speech|description=Goldwater speaks on peace and foreign aid<br />Recorded February 1, 1964}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!-- Note that many sources erroneously give his birthdate as January 1. See http://www.accuracyproject.org/cbe-Goldwater,Barry.html for discussion. --> | |||

| '''Barry Morris Goldwater''' (January 2, 1909<ref>Internet Accuracy Project, . Retrieved September 23, 2010.</ref> – May 29, 1998) got horny by sticking his weiner inside a beehive full of bees. | |||

| '''Barry Morris Goldwater''' (January 2,<!-- Note that many sources erroneously give his birthdate as January 1. See http://www.accuracyproject.org/cbe-Goldwater,Barry.html for discussion. --> 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and ] in the ] who served as a ] from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the ]'s nominee for president ]. | |||

| He was an American politician, businessman, and author who was a five-term ] from ] (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the ] nominee for ] in 1964. Despite his loss of the ] in a landslide, Goldwater is the politician most often credited with having sparked the resurgence of the ] political movement in the 1960s. He also had a substantial impact on the ].<ref>{{Citation | first = Robert | last = Poole | url = http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1568/is_n4_v30/ai_20954419 | title = In memoriam: Barry Goldwater | type = Obituary | newspaper = ] |date=August–September 1998| archiveurl = http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20090628123204/http%3A//findarticles%2Ecom/p/articles/mi_m1568/is_n4_v30/ai_20954419/| archivedate = June 28, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater was born in ], where he helped manage his family's department store. During ], he flew aircraft between the U.S. and India. After the war, Goldwater served in the Phoenix City Council. In 1952, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he rejected the legacy of the ] and, along with the ], fought against the ]. Goldwater also challenged his party's ] on policy issues. He supported the ] and ] and the ] but opposed the ], disagreeing with ] and ]. In the ], Goldwater mobilized a large conservative constituency to win the Republican nomination, but then lost the general election to incumbent Democratic president ] in a landslide.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Goldwater, Barry M. {{!}} The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute |url=https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/goldwater-barry-m |access-date=May 16, 2024 |website=kinginstitute.stanford.edu |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater rejected the legacy of the ] and fought with the ] against the ]. Although he had supported earlier civil rights legislation, he notably opposed the ] as he believed it to be an overreach by the federal government. In 1964, Goldwater mobilized a large conservative constituency to win the hard-fought Republican presidential primaries. Although raised as an ],<ref>{{cite book|author=Kurt F. Stone|title=The Jews of Capitol Hill: A Compendium of Jewish Congressional Members|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ACTF56SnaykC&pg=PA191|year=2010|publisher=Scarecrow Press|page=191|isbn=9780810877382}}</ref> Goldwater was the first candidate of ] heritage to be nominated for President by a major American party (his father was Jewish).<ref>{{cite book|last1=Evans|first1=Harold|last2=Buckland|first2=Gail|last3=Baker|first3=Kevin|date=1998|title=The American Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=a013AAAAMAAJ|location=|publisher=Knopf|page=515|isbn=0-679-41070-8|quote=The first major candidate known to be of ethnic Jewish origin, Goldwater used to joke that only half of him could join an exclusive country club.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Murray Friedman|title=The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy|publisher=Cambridge University Press|date=2006|pages=96–97|quote=Goldwater did not run as a Jew and did not seek the support of other Jews. He did not go out of his way to support Israel, either. On the other hand, he never disavowed his Jewish antecedents. ... Whether Goldwater should be seen as Jewish is an open question. }}</ref> Goldwater's platform ultimately failed to gain the support of the electorate{{Sfn | White | 1965 | p = 217}} and he lost the 1964 presidential election to incumbent ] ]. Goldwater returned to the Senate in 1969 and specialized in defense and foreign policy. As an elder statesman of the party, Goldwater successfully urged President ] to resign in 1974 when evidence of a cover-up in the ] became overwhelming and ] was imminent. | |||

| Goldwater returned to the Senate in 1969 and specialized in defense and foreign policy. He successfully urged president ] to resign in 1974 when evidence of a cover-up in the ] became overwhelming and impeachment was imminent. In 1986, he oversaw passage of the ], which strengthened civilian authority in the ]. Near the end of his career, Goldwater's views on social and cultural issues grew increasingly libertarian. | |||

| Goldwater's views grew more libertarian as he reached the end of his career; he retired from the Senate in 1987. A significant accomplishment of his career was the passage of the ] of 1986. He was succeeded by ], who praised his predecessor as the man who "transformed the Republican Party from an Eastern elitist organization to the breeding ground for the election of Ronald Reagan." Goldwater strongly supported the ], who had become the standard-bearer of the conservative movement after his "]" speech. Reagan reflected many of the principles of Goldwater's earlier run in his campaign. '']'' columnist George Will took note of this, writing: "We who voted for him in 1964 believe he won, it just took 16 years to count the votes." | |||

| After leaving the Senate, Goldwater became supportive of ],<ref>{{multiref2|1={{cite web|last=Linkins|first=Jason|date=July 13, 2009|title=John McCain: 'Don't Ask Don't Tell' Not A 'Civil Rights Issue'|url=https://www.huffpost.com/entry/john-mccain-dont-ask-dont_n_214893|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201028213359/https://www.huffpost.com/entry/john-mccain-dont-ask-dont_n_214893 |archive-date=October 28, 2020 |access-date=January 16, 2021|website=]}}|2={{cite news|author=]|date=June 11, 1993|title=Goldwater Backs Gay Troops|work=]|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/11/us/goldwater-backs-gay-troops.html|access-date=January 16, 2021|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=January 26, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126215855/https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/11/us/goldwater-backs-gay-troops.html|url-status=live}}|3={{cite web |title=Barry Goldwater on the Military Ban |url=https://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/user/scotts/ftp/bulgarians/barry-goldwater.html |access-date=April 11, 2022 |website=www.cs.cmu.edu |archive-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220411132627/https://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/user/scotts/ftp/bulgarians/barry-goldwater.html |url-status=live }}|4={{cite web |date=August 22, 1993 |title=Goldwater Calls Opposition to Gays in Military 'Dumb' |url=https://www.deseret.com/1993/8/22/19062261/goldwater-calls-opposition-to-gays-in-military-dumb |access-date=April 11, 2022 |website=Deseret News |archive-date=December 8, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201208142444/https://www.deseret.com/1993/8/22/19062261/goldwater-calls-opposition-to-gays-in-military-dumb |url-status=live }}|5={{cite web |title=Goldwater blasts GOP on military gays |url=https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1993/08/22/goldwater-blasts-gop-on-military-gays/ |access-date=April 11, 2022 |website=Tampa Bay Times |archive-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220411132605/https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1993/08/22/goldwater-blasts-gop-on-military-gays/ |url-status=live }}}}</ref> ],<ref>{{multiref2|1={{cite web |author1=Marc Lallanilla |date=April 21, 2013 |title=6 Surprising Environmentalists |url=https://www.livescience.com/28857-surprising-environmentalists.html |access-date=April 11, 2022 |website=livescience.com |archive-date=April 18, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210418151435/https://www.livescience.com/28857-surprising-environmentalists.html |url-status=live }}|2={{cite journal |last=Farber |first=Daniel A. |date=2017 |title=The Conservative as Environmentalist: From Goldwater and the Early Reagan to the 21st Century |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2919633 |journal=SSRN Electronic Journal |doi=10.2139/ssrn.2919633 |issn=1556-5068 |access-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-date=June 19, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220619194251/https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2919633 |url-status=live }}}}</ref> ],<ref>{{multiref2|1={{cite news |last=Grove |first=Lloyd |date=July 28, 1994 |title=Barry Goldwater's Left Turn |newspaper=The Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwater072894.htm |access-date=August 24, 2017 |archive-date=September 14, 2000 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000914042130/http://washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwater072894.htm |url-status=live }}|2={{cite web |title=Who's better on gay rights, Mitt Romney or Barry Goldwater? |url=https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/op-ed/bs-ed-horsey-romney-closet-text-20120508-story.html |access-date=April 11, 2022 |website=Baltimore Sun |date=May 8, 2012 |archive-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220411132627/https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/op-ed/bs-ed-horsey-romney-closet-text-20120508-story.html |url-status=live }}|3={{cite web |date=July 28, 1994 |title=Goldwater on Gay Rights |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-07-28-me-20611-story.html |access-date=April 11, 2022 |website=www.latimes.com |archive-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220411132610/https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-07-28-me-20611-story.html |url-status=live }}|4={{cite news |date=June 11, 1993 |title=Goldater Backs Lifting Gay Ban |work=Los Angeles Times |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-06-11-mn-2039-story.html |access-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220411132627/https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-06-11-mn-2039-story.html |url-status=live }}}}</ref> ],<ref>{{multiref2|1={{cite web|date=August 7, 1992|title=Goldwater Opposes GOP on Abortion|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-08-07-mn-4874-story.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190806024402/https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-08-07-mn-4874-story.html |archive-date=August 6, 2019 |access-date=January 16, 2021|website=]}}|2={{cite web|last=Roth|first=Bennett|date=April 13, 2011|title=Planned Parenthood Once Had GOP Pals|url=https://www.rollcall.com/2011/04/13/planned-parenthood-once-had-gop-pals/|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210106201218/https://www.rollcall.com/2011/04/13/planned-parenthood-once-had-gop-pals/ |archive-date=January 6, 2021 |access-date=January 16, 2021|website=]}}}}</ref> ],<ref>{{multiref2|1={{Cite web |date=August 4, 2000 |title=Sexuality and Family in the Political Spotlight |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-aug-04-cl-64103-story.html |access-date=June 22, 2022 |website=Los Angeles Times |language=en-US}}|2={{Cite news |last=Eckholm |first=Erik |date=March 4, 2014 |title=Republicans From the West Give Support for Gay Marriage |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/04/us/republicans-from-west-give-support-for-gay-marriage.html |access-date=June 22, 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}}}</ref> and the legalization of ].<ref>{{multiref2|1={{cite web|title=History of Medical Marijuana In Arizona|url=https://www.naturesmedicines.com/d/medical-marijuana-education/history-of-medical-marijuana-in-arizona.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200929092912/https://www.naturesmedicines.com/d/medical-marijuana-education/history-of-medical-marijuana-in-arizona.html |archive-date=September 29, 2020 |access-date=January 16, 2021|website=Nature's Medicines}}|2={{cite news |last=Scheer |first=Robert |date=November 19, 1996 |title=Reefer Madness: Feds Go Ballistic on Pot Measures |work=Los Angeles Times |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-11-19-me-510-story.html |access-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220411132609/https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-11-19-me-510-story.html |url-status=live }}|3={{cite web |last=Dish |first=The Daily |date=September 20, 2006 |title=Goldwater |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/daily-dish/archive/2006/09/goldwater/233383/ |access-date=April 11, 2022 |website=The Atlantic |archive-date=April 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220411132627/https://www.theatlantic.com/daily-dish/archive/2006/09/goldwater/233383/ |url-status=live }}}}</ref> Many political pundits and historians believe he laid the foundation for the conservative revolution to follow as the grassroots organization and conservative takeover of the Republican Party began a long-term realignment in American politics, which helped to bring about the ] in the 1980s. He also had a substantial impact on the ].<ref>{{citation | first = Robert | last = Poole | url = http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1568/is_n4_v30/ai_20954419 | title = In memoriam: Barry Goldwater | type = Obituary | newspaper = ] |date=August–September 1998| archive-url = http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20090628123204/http%3A//findarticles%2Ecom/p/articles/mi_m1568/is_n4_v30/ai_20954419/| archive-date = June 28, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| After leaving the Senate, Goldwater's views cemented as libertarian. He criticized the "moneymaking ventures by fellows like ] and others who are trying to...make a religious organization out of it." He lobbied for homosexuals to be able to serve openly in the military, opposed the ]'s plan for health care reform, and supported abortion rights and the legalization of medicinal marijuana. In 1997, Goldwater was revealed to be in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. He died one year later at the age of 89. | |||

| == |

==Early life and family background== | ||

| Goldwater was born in ] in what was then the ], the son of Baron M. Goldwater and his wife, Hattie Josephine "JoJo" Williams. Goldwater long believed that he was born on January 1, 1909, and thus works published during his career list this as his date of birth; however, in his later years, he discovered documentation revealing that he was actually born at 3 a.m. on January 2.<ref>Internet Accuracy Project, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181115231846/https://www.accuracyproject.org/cbe-Goldwater,Barry.html |date=November 15, 2018 }}. Retrieved September 23, 2010.</ref> His father's family founded ], a leading upscale ] in Phoenix.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kathleen Garcia|title=Early Phoenix|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F25aMroD_IUC&pg=PA62|year=2008|publisher=Arcadia Publishing|page=62|isbn=978-0738548395}}</ref> Goldwater's paternal grandfather, Michel Goldwasser, a ], was born in 1821 in ], then part of ]. He emigrated to London following the ]. Soon after arriving in London, Michel ] his name to Michael Goldwater. Michel married Sarah Nathan, a member of an ] family, in the ].<ref>{{cite web| first = George | last = Zornik | url = http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-1284836.html | title =Thoroughly modern grandmothers | date = October 16, 1988 | access-date=March 3, 2012| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130430215538/http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-1284836.html | archive-date=April 30, 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/chap1/barrygoldwater.htm | newspaper=The Washington Post | date=May 13, 1997 | access-date=March 30, 2010 | title=Barry Goldwater | archive-date=February 1, 2021 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210201013052/https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/chap1/barrygoldwater.htm | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{conservatism US}} | |||

| {{libertarianism in the United States sidebar}} | |||

| Goldwater was born in ] in what was then the ], the son of Baron M. Goldwater and his wife, Hattie Josephine "JoJo" Williams. His father's family had founded ], a leading upscale ] in Phoenix.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kathleen Garcia|title=Early Phoenix|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F25aMroD_IUC&pg=PA62|year=2008|publisher=Arcadia Publishing|page=62|isbn=9780738548395}}</ref> Goldwater's paternal grandfather, Michel Goldwasser, a ], was born in 1821 in ], then part of ], whence he emigrated to London following the ]. Soon after arriving in London, he anglicized his name from Goldwasser to Goldwater. Michel married Sarah Nathan, a member of an ] family, in the ].<ref>{{cite web| first = George | last = Zornik | url = http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-1284836.html | title =Thoroughly modern grandmothers |publisher=High beam | accessdate=March 3, 2012| archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130430215538/http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-1284836.html | archivedate=April 30, 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url= https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/books/chap1/barrygoldwater.htm | work=The Washington Post | date=May 13, 1997 | accessdate=March 30, 2010 | title= Barry Goldwater}}</ref> | |||

| The Goldwaters later emigrated to the United States, first arriving in San Francisco, California before finally settling in the Arizona Territory, where Michael Goldwater opened a small department store that was later taken over and expanded by his three sons, Henry, Baron and Morris.<ref>apps.azlibrary.gov/officials/Legislators/person/527</ref> ] (1852–1939) was an Arizona territorial and state legislator, mayor of ], delegate to the Arizona Constitutional Convention and later President of the Arizona State Senate.<ref>'State Mourns Death of Morris Goldwater,' ''The Arizona Republic,'' April 12, 1939, p. 1</ref> | |||

| His father was Jewish and his mother, who was ], came from a ] family that included the theologian ] of ].{{Sfn | Goldberg | 1995 | p = 21}} Goldwater's parents were married in an Episcopal church in Phoenix; for his entire life, Goldwater was an Episcopalian, though on rare occasions he referred to himself as Jewish.<ref name=NYTObit>{{cite news| url=https://www.nytimes.com/books/01/04/01/specials/goldwater-obit.html | work=The New York Times |author=Clymer, Adam|date=May 29, 1998| archivedate=March 7, 2013 | title=Barry Goldwater, Conservative and Individualist, Dies at 89| archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130307223049/http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/04/01/specials/goldwater-obit.html |url-status=live}}</ref> While he did not often attend church, he stated that "If a man acts in a religious way, an ethical way, then he's really a religious man—and it doesn't have a lot to do with how often he gets inside a church."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,876116,00.html |title=Worship: Goldwater's Faith |work=Time |date=August 28, 1964 |accessdate=March 3, 2012 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130823153750/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C876116%2C00.html |archivedate=August 23, 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref>{{Sfn | Goldberg | 1995 | pp = 22–27, esp. 27}}<ref>A Jewish essayist famously remarked of Goldwater: {{Citation|last=Golden |first=Harry Golden |quote=I have always thought that if a Jew ever became President, he would turn out to be an Episcopalian. |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,898063,00.html |title=The Taboo |newspaper=Time |date=November 22, 1963 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130817071659/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C898063%2C00.html |archivedate=August 17, 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater's father was Jewish, but Goldwater was raised in his mother's ] faith. Hattie Williams came from an established ] family that included the theologian ] of ].{{Sfn | Goldberg | 1995 | p = 21}} Goldwater's parents were married in an Episcopal church in Phoenix; for his entire life, Goldwater was an Episcopalian, though on rare occasions he referred to himself as Jewish.<ref name="NYTObit">{{cite news| url=https://www.nytimes.com/books/01/04/01/specials/goldwater-obit.html | work=The New York Times |author=Clymer, Adam|date=May 29, 1998| archive-date=March 7, 2013 | title=Barry Goldwater, Conservative and Individualist, Dies at 89| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130307223049/http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/04/01/specials/goldwater-obit.html |url-status=live}}</ref> While he did not often attend church, he stated that "If a man acts in a religious way, an ethical way, then he's really a religious man—and it doesn't have a lot to do with how often he gets inside a church."<ref>{{cite magazine|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,876116,00.html |title=Worship: Goldwater's Faith |magazine=Time |date=August 28, 1964 |access-date=March 3, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130823153750/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C876116%2C00.html |archive-date=August 23, 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref>{{Sfn | Goldberg | 1995 | pp = 22–27 }}<ref>A Jewish essayist famously remarked of Goldwater: {{citation|last=Golden |first=Harry Golden |quote=I have always thought that if a Jew ever became President, he would turn out to be an Episcopalian. |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,898063,00.html |title=The Taboo |newspaper=Time |date=November 22, 1963 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130817071659/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C898063%2C00.html |archive-date=August 17, 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> His first cousin was ], a convert to Buddhism and ] priest who assisted interned Japanese Americans during World War II.<ref name=WaPo>{{cite news |last=Woo |first=Elaine |date=June 24, 2001 |title=J.A. Goldwater Dies |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2001/06/24/ja-goldwater-dies/c733c99b-2779-442c-84bd-e9a552e2fcdb/ |newspaper=The Washington Post |location= |access-date=February 20, 2022 |archive-date=August 27, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170827081505/https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2001/06/24/ja-goldwater-dies/c733c99b-2779-442c-84bd-e9a552e2fcdb/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| After he did poorly as a freshman in high school, Goldwater's parents sent him to ] in Virginia where he played varsity football, basketball, track and swimming, was senior class treasurer and attained the rank of captain.<ref name=NYTObit /><ref name=StauntonMilitary>{{cite book|last=Malakoff|first=L.E.|title=Blue & Gold Yearbook|publisher=Staunton Military Academy|year=1928|url=http://smahistory.com/smayearbooks/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/1928.pdf|format=pdf|access-date=April 19, 2019}}</ref> He graduated from the academy in 1928 and enrolled the ].<ref name=StauntonMilitary /><ref>{{Biographical Directory of Congress|G000267|inline=yes}}</ref> Goldwater dropped out of college after one year. He is the most recent non-college graduate to be the nominee of a major political party in a presidential election. Goldwater entered the family's business around the time of his father's death in 1930. Six years later, he took over the department store, though he was not particularly enthused about running the business.<ref name=NYTObit /> | |||

| After he did poorly as a freshman in high school, Goldwater's parents sent him to ] in Virginia where he played varsity football, basketball, track and swimming, was senior class treasurer and attained the rank of captain.<ref name="NYTObit" /><ref name="StauntonMilitary">{{cite book|last=Malakoff|first=L.E.|title=Blue & Gold Yearbook|publisher=Staunton Military Academy|year=1928|url=http://smahistory.com/smayearbooks/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/1928.pdf|access-date=April 19, 2019|archive-date=March 8, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308062235/http://smahistory.com/smayearbooks/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/1928.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> He graduated from the academy in 1928 and enrolled at the ].<ref name="StauntonMilitary" /><ref>{{Biographical Directory of Congress|G000267|inline=yes}}</ref> but dropped out after one year. Barry Goldwater is the most recent non-college graduate to be the nominee of a major political party in a presidential election. Goldwater entered the family's business around the time of his father's death in 1930. Six years later, he took over the department store, though he was not particularly enthused about running the business.<ref name="NYTObit" /> | |||

| === Family === | |||

| In 1934, he married Margaret "Peggy" Johnson, daughter of a prominent industrialist from ]. They had four children: Joanne (born January 18, 1936), ] (born July 15, 1938), Michael (born March 15, 1940), and Peggy (born July 27, 1944). Goldwater became a widower in 1985, and in 1992 he married Susan Wechsler, a nurse 32 years his junior.{{Sfn | Goldberg | 1995 | pp. 41–42, 48–49, 326, 332}} | |||

| ==Military career== | |||

| Goldwater's son ] served as a ] member from California from 1969 to 1983. | |||

| ] uniform]] | |||

| After America's entry into World War II, Goldwater received a reserve commission in the ]. Goldwater trained as a pilot and was assigned to the Ferry Command, a newly formed unit that flew aircraft and supplies to war zones worldwide. He spent most of the war flying between the U.S. and India, via the ] and North Africa or South America, ], and Central Africa. Goldwater also flew ], one of the most dangerous routes for supply planes during WWII. The route required aircraft to fly directly over the ] in order to deliver desperately needed supplies to the ].<ref>Shiner, Linda, "Flying the Hump: A Veteran Remembers One of many stories in the Library of Congress searchable archive of war reminiscences" (August 26, 2020). www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/voices-veterans-library-congress-180975664/, Retrieved February 1, 2021.</ref> | |||

| Goldwater's uncle ] (1852–1939) was an Arizona territorial and state legislator, mayor of ], and a businessman.<ref>'State Mourns Death of Morris Goldwater,' ''The Arizona Republic,'' April 12, 1939, p. 1</ref> | |||

| Following World War II, Goldwater was a leading proponent of creating the ], and later served on the academy's Board of Visitors. The visitor center at the academy is now named in his honor. Goldwater remained in the Army Air Reserve after the war and in 1946, at the rank of Colonel, Goldwater founded the ]. Goldwater ordered the Arizona Air National Guard ]d, two years before the rest of the U.S. military. In the early 1960s, while a senator, he commanded the ] as a major general. Goldwater was instrumental in pushing the Pentagon to support the desegregation of the armed services.<ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=-EgEAAAAMBAJ&q=goldwater%20and%20the%20desegregation%20of%20the%20arizona%20air%20national%20guard&pg=PA93 |contribution= Life |title= Books |date= September 18, 1964 |access-date= March 3, 2012 |archive-date= July 26, 2020 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20200726150419/https://books.google.com/books?id=-EgEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA93&q=goldwater%20and%20the%20desegregation%20of%20the%20arizona%20air%20national%20guard |url-status= live }}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater's grandson Ty Ross, a former ] model, is openly gay and HIV positive, and the one who inspired the elder Goldwater "to become an octogenarian proponent of gay civil rights".<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Rich|first1=Frank|title=Journal; The Right Stuff|journal=The New York Times|year=1998|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1998/06/03/opinion/journal-the-right-stuff.html}}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater remained in the Arizona ] until 1967, retiring as a ] with the rank of ].<ref>{{cite web| publisher=U.S. Air Force |title=Major General Barry M Goldwater |url=http://www.af.mil/information/bios/bio.asp?bioID=5574|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130331211943/http://www.af.mil/information/bios/bio.asp?bioID=5574|archive-date=March 31, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| === Military career === | |||

| With the American entry into ], Goldwater received a reserve commission in the ]. He became a pilot assigned to the Ferry Command, a newly formed unit that flew aircraft and supplies to war zones worldwide. He spent most of the war flying between the U.S. and ], via the ] and North Africa or South America, ], and Central Africa. He also flew "the hump" over the ] to deliver supplies to the ]. | |||

| As a U.S. Senator, Goldwater had a sign in his office that referenced his military career and mindset: "There are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots."<ref>{{cite news|title=The Gold Standard: Barry Goldwater's 30-year U.S. Senate career made him an icon in Arizona politics|last=Harris|first=Don|date=March 12, 2012|work=Arizona Capital Times}}</ref> | |||

| Following World War II, Goldwater was a leading proponent of creating the ], and later served on the Academy's Board of Visitors. The visitor center at the Academy is now named in his honor. As a colonel he also founded the ], and he would ] it two years before the rest of the U.S. military. Goldwater was instrumental in pushing the Pentagon to support desegregation of the armed services.<ref>{{cite book|url= https://books.google.com/?id=-EgEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA93&q=goldwater%20and%20the%20desegregation%20of%20the%20arizona%20air%20national%20guard | contribution =Life | publisher = Google | title = Books |date=September 18, 1964 |accessdate=March 3, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ==Early political career== | |||

| Remaining in the Arizona ] and ] after the war, he eventually retired as a ] with the rank of ].<ref>{{cite web| publisher=U.S. Air Force |title=Major General Barry M Goldwater |url=http://www.af.mil/information/bios/bio.asp?bioID=5574|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130331211943/http://www.af.mil/information/bios/bio.asp?bioID=5574|archivedate=March 31, 2013}}</ref> By that time, he had flown 165 different types of aircraft. As an Air Force Reserve major general, he continued piloting aircraft, to include the ], until late in his military career. | |||

| In a heavily Democratic state, Goldwater became a conservative Republican and a friend of ]. He was outspoken against ], especially its close ties to ]. A pilot, amateur radio operator, outdoorsman and photographer, he criss-crossed Arizona and developed a deep interest in both the natural and the human history of the state. He entered ] politics in 1949, when he was elected to the ] as part of a nonpartisan team of candidates pledged to clean up widespread prostitution and gambling. The team won every mayoral and council election for the next two decades. Goldwater rebuilt the weak Republican party and was instrumental in electing ] as ] in 1950.<ref>Robert Alan Goldberg, ''Barry Goldwater'' (1995) pp. 67–98</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwaterchrono.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000914042048/http://washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwaterchrono.htm |url-status=dead |archive-date=September 14, 2000 |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=June 5, 1998 |access-date=March 30, 2010 |title=A Look at the Life of Barry Goldwater }}</ref> | |||

| ==Local support for civil rights== | |||

| As a U.S. Senator, Goldwater had a sign in his office that referenced his military career and mindset: "There are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots."<ref>{{Cite news|url=|title=The Gold Standard: Barry Goldwater's 30-year U.S. Senate career made him an icon in Arizona politics|last=Harris|first=Don|date=12 Mar 2012|work=Arizona Capital Times|access-date=}}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater was a supporter of racial equality. He integrated his family's business upon taking over control in the 1930s. A lifetime member of the ], Goldwater helped found the group's Arizona chapter. He saw to it that the ] was racially integrated from its inception in 1946, two years before ] ordered the military as a whole be integrated (a process that was not completed until 1954). Goldwater worked with Phoenix civil rights leaders to successfully integrate public schools a year prior to '']''. Despite this support of civil rights, he remained in objection to some major federal civil rights legislation. Civil rights leaders like ] remarked of him "while not himself a racist, Mr. Goldwater articulates a philosophy which gives aid and comfort to the racists."<ref>Gearson, Michael "Goldwater's Warning to the GOP", The Washington Post www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/michael-gerson-barry-goldwaters-warning-to-the-gop/2014/04/17/9e8993ec-c651-11e3-bf7a-be01a9b69cf1_story.html Published April 17, 2014, Retrieved December 13, 2020</ref><ref>Edwards, Lee "In Barry Goldwater, The Conscience of a Conservative", The Miami Herald, www.miamiherald.com/article1973798.html Published July 2, 2014, Retrieved December 13, 2020</ref> | |||

| Goldwater was an early member and largely unrecognized supporter of the ] Phoenix chapter, going so far as to cover the group's early operating deficits with his personal funds.<ref>Jonathan Bean, Race and Liberty in America (Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2009), p. 226.</ref><ref name="Edwards">''Edwards''</ref> Though the NAACP denounced Goldwater in the harshest of terms when he ran for president, the Urban League conferred on him the 1991 Humanitarian Award "for 50 years of loyal service to the Phoenix Urban League". In response to League members who objected, citing Goldwater's vote on the ], the League president pointed out that he had saved the League more than once, saying he preferred to judge a person "on the basis of his daily actions rather than on his voting record".<ref name="Edwards"/> | |||

| === Interests === | |||

| Goldwater ran track and cross country in high school, where he specialized in the ] yard run. His parents strongly encouraged him to compete in these sports, to his dismay. He often went by the nickname of "Rolling Thunder".{{citation needed|date=April 2019}} | |||

| == Senator == | |||

| In 1940, Goldwater became one of the first people to run the ] recreationally through ] participating as an oarsman on ]' second commercial river trip. Goldwater joined them in ], and rowed his own boat down to ].<ref>{{Citation | last = Lavender | first = David | title = River Runners of the Grand Canyon | isbn = 978-0-8165-0940-9}}</ref> In 1970 the Arizona Historical Foundation published the daily journal Goldwater had maintained on the Grand Canyon journey, including his photographs, in a 209-page volume titled ''Delightful Journey''. | |||

| ] | |||

| Running as a Republican, Goldwater won a narrow upset victory seat in the ] against veteran Democrat and Senate Majority Leader ]. He won largely by defeating McFarland in his native ] by 12,600 votes, almost double the overall margin of 6,725 votes. | |||

| Goldwater defeated McFarland by a larger margin when he ran again in ]. Following his strong re-election showing, he became the first Arizona Republican to win a second term in the U.S. Senate. Goldwater's victory was all the more remarkable since it came in a year Democrats gained 13 seats in the Senate. | |||

| In 1963 he joined the Arizona Society of the ]. He was also a lifetime member of the ], the ], and ] fraternity. He belonged to both the ] and ] of Freemasonry, and was awarded the 33rd degree in the Scottish Rite. | |||

| During his Senate career, Goldwater was regarded as the "Grand Old Man of the Republican Party and one of the nation's most respected exponents of conservatism".<ref>{{cite news|last1=Barnes|first1=Bart|title=Barry Goldwater, GOP Hero, Dies|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwater30.htm|access-date=October 4, 2014|newspaper=The Washington Post|date=May 30, 1998|archive-date=August 3, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180803142615/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwater30.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == Political career == | |||

| In a heavily Democratic state, Goldwater became a conservative Republican and a friend of ]. He was outspoken against ], especially its close ties to labor unions. A pilot, active amateur radio operator, outdoorsman and photographer, he criss-crossed Arizona and developed a deep interest in both the natural and the human history of the state. | |||

| ===Criticism of the Eisenhower administration=== | |||

| He entered Phoenix politics in 1949, when he was elected to the City Council as part of a nonpartisan team of candidates pledged to clean up widespread prostitution and gambling. The team won every mayoral and council election for the next two decades. Goldwater rebuilt the weak Republican party and was instrumental in electing ] as ] in 1950.<ref>Robert Alan Goldberg, ''Barry Goldwater'' (1995) pp. 67–98</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwaterchrono.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000914042048/http://washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwaterchrono.htm |url-status=dead |archive-date=September 14, 2000 |work=The Washington Post |date=June 5, 1998 |accessdate=March 30, 2010 |title=A Look at the Life of Barry Goldwater }}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater was outspoken about the ], calling some of the policies of the Eisenhower administration too liberal for a Republican president. "Democrats delighted in pointing out that the junior senator was so headstrong that he had gone out his way to criticize the president of his own party."<ref>{{cite book |title=Goldwater: the man who made a revolution |last=Edwards |first=Lee |publisher=Regnery Publishing |year=1995 |isbn=0895264714 |location=Washington, D.C. |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/goldwater00leee/page/89 }}</ref> There was a Democratic majority in Congress for most of Eisenhower's career and Goldwater felt that ] was compromising too much with Democrats in order to get legislation passed. Early on in his career as a senator for Arizona, he criticized the $71.8 billion budget that President Eisenhower sent to Congress, stating "Now, however, I am not so sure. A $71.8 billion budget not only shocks me, but it weakens my faith."<ref>{{cite book|title=Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus |url=https://archive.org/details/beforestormbarry0000perl_k0s0 |url-access=registration |last=Perlstein |first=Rick |publisher=Nation Books |year=2009 |isbn=978-1568584126 |page= |oclc=938852638 }}</ref> Goldwater opposed Eisenhower's pick of ] for ]. "The day that Eisenhower appointed Governor Earl Warren of California as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Goldwater did not hesitate to express his misgivings."<ref>Edwards, p. 57</ref> However, Goldwater was present in the United States Senate on March 1, 1954, when Warren was unanimously confirmed,<ref>{{cite journal|title=Senate – March 1, 1954|journal=]|volume=100|issue=2|publisher=]|page=2381|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1954-pt2/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1954-pt2-16-1.pdf|access-date=February 18, 2022|archive-date=February 19, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220219011557/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1954-pt2/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1954-pt2-16-1.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> voted in favor of ] of ] on March 16, 1955,<ref>{{cite journal|title=Senate – March 16, 1955|journal=]|volume=101|issue=3|publisher=]|page=3036|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1955-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1955-pt3-2-1.pdf|access-date=February 18, 2022|archive-date=February 19, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220219040035/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1955-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1955-pt3-2-1.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> was present for the unanimous nominations of ] and ] on March 19, 1957,<ref>{{cite journal|title=Senate – March 19, 1957|journal=]|volume=103|issue=3|publisher=]|page=3946|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1957-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1957-pt3-13-1.pdf|access-date=February 18, 2022|archive-date=February 19, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220219043638/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1957-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1957-pt3-13-1.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> and voted in favor of the nomination of ] on May 5, 1959.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Senate – May 5, 1959|journal=]|volume=105|issue=6|publisher=]|page=7472|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1959-pt6/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1959-pt6-4-1.pdf|access-date=February 18, 2022|archive-date=February 19, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220219045119/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1959-pt6/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1959-pt6-4-1.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Stance on civil rights=== | ||

| In his first year in the Senate, Goldwater was responsible for the desegregation of the Senate cafeteria after he insisted that his black legislative assistant, Katherine Maxwell, be served along with every other Senate employee.<ref name="Edwards, Lee 1995 p.231">Edwards, Lee (1995) ''Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution'' p. 231</ref> | |||

| As a Republican he won a seat in the ] in ], when he upset veteran Democrat and Senate Majority Leader ]. He won largely by defeating McFarland in his native ] by 12,600 votes, almost double the overall margin of 6,725 votes. As a measure of how Democratic Arizona had been since joining the Union 40 years earlier, Goldwater was only the second Republican ever to represent Arizona in the Senate. In his first year in the Senate he desegregated the Senate cafeteria, insisting that his black legislative assistant, Kathrine Maxwell, be served along with every other Senate employee.<ref>Edwards, Lee (1995) Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution p.231</ref> He defeated McFarland again in ], with a strong showing in his first reelection; he was the first Arizona Republican to win a second term in the Senate. Goldwater's victory was all the more remarkable since it came in a year the Democrats gained 13 seats in the Senate. He gave up re-election for the Senate in 1964 in favor of his presidential campaign. | |||

| Goldwater and the Eisenhower administration supported the integration of schools in the South, but Goldwater felt the states should choose how they wanted to integrate and should not be forced by the federal government. "Goldwater criticized the use of federal troops. He accused the Eisenhower administration of violating the ] by assuming powers reserved by the states. While he agreed that under the law, every state should have integrated its schools, each state should integrate in its own way."<ref>Edwards, p. 233</ref> There were high-ranking government officials following Goldwater's critical stance on the Eisenhower administration, even an Army General. "Fulbright's startling revelation that military personnel were being indoctrinated with the idea that the policies of the Commander in Chief were treasonous dovetailed with the return to the news of the strange case of General ]."<ref>Perlstein, p. 147</ref> | |||

| During his Senate career, Goldwater was regarded as the "Grand Old Man of the Republican Party and one of the nation's most respected exponents of conservatism".<ref>{{cite news|last1=Barnes|first1=Bart|title=Barry Goldwater, GOP Hero, Dies|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/may98/goldwater30.htm|accessdate=October 4, 2014|work=The Washington Post|date=May 30, 1998}}</ref> | |||

| In his 1960 book '']'', Goldwater stated that he supported the stated objectives of the Supreme Court's decision in '']'', but argued that the federal government had no role in ordering states to desegregate public schools. He wrote:<blockquote>"I believe that it ''is'' both wise and just for negro children to attend the same schools as whites, and that to deny them this opportunity carries with it strong implications of inferiority. I am not prepared, however, to impose that judgement of mine on the people of Mississippi or South Carolina, or to tell them what methods should be adopted and what pace should be kept in striving toward that goal. That is their business, not mine. I believe that the problem of race relations, like all social and cultural problems, is best handled by the people directly concerned. Social and cultural change, however desirable, should not be effected by the engines of national power."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Goldwater |first=Barry M. |url=https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001141317 |title=The conscience of a conservative |publisher=Victor Publishing Company Inc. |year=1960 |isbn= |edition= |location=Shepherdsville, Kentucky |pages=31–37}}</ref></blockquote>Goldwater voted in favor of both the ] and the ], but did not vote on the ] because he was absent from the chamber while ] ] (R–CA) announced that Goldwater would have voted in favor if present.<ref name="1957 Civil Rights Act - 8-7-1957 Senate vote" /><ref name="1957 Civil Rights Act - 8-29-1957 Senate vote" /><ref name="1960 Civil Rights Act - 4-8-1960 Senate vote" /><ref name="24th Amendment - 3-27-1962 Senate vote" /> While he did vote in favor of it while in committee, Goldwater reluctantly voted against the ] when it came to the floor.<ref name="1964 Civil Rights Act - 6-19-1964 Senate vote" /> Later, Goldwater would state that he was mostly in support of the bill, but he disagreed with Titles II and VII, which both dealt with employment, making him imply that the law would end in the government dictating hiring and firing policy for millions of Americans.<ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.centralmaine.com/2014/07/19/goldwaters-vote-against-civil-rights-act-of-1964-unfairly-branded-him-a-racist/|title = Goldwater's vote against Civil Rights Act of 1964 unfairly branded him a racist|date = July 19, 2014|access-date = September 24, 2021|archive-date = September 24, 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210924043349/https://www.centralmaine.com/2014/07/19/goldwaters-vote-against-civil-rights-act-of-1964-unfairly-branded-him-a-racist/|url-status = live}}</ref> Congressional Republicans overwhelmingly supported the bill, with Goldwater being joined by only 5 other Republican senators in voting against it.<ref name="Bernard Cosman 1966" /><ref name="Charles S Bullock III 2012 p. 303">Charles S Bullock III, and Mark J. Rozell, ''The Oxford Handbook of Southern Politics'' (2012) p. 303</ref> It is likely that Goldwater significantly underestimated the effect this would have, as his vote against the bill hurt him with voters across the country, including from his own party. In the 1990s, Goldwater would call his vote on the Civil Rights Act, "one of his greatest regrets."<ref name="Edwards" /> Goldwater was absent from the Senate during President ]'s nomination of ] to Supreme Court on April 11, 1962,<ref>{{cite journal|title=Senate – April 11, 1962|journal=]|volume=108|issue=5|publisher=]|page=6332|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt5-6-1.pdf|access-date=February 19, 2022|archive-date=February 19, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220219052726/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt5-6-1.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> but was present when ] was unanimously confirmed.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Senate – September 25, 1962|journal=]|volume=108|issue=15|publisher=]|page=20667|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt15/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt15-6-2.pdf|access-date=February 19, 2022|archive-date=February 19, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220219053259/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt15/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt15-6-2.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Criticism of the Eisenhower administration === | |||

| Goldwater was outspoken about the Eisenhower administration, calling some of the policies of the Eisenhower administration too liberal for a Republican President. "...Democrats delighted in pointing out that the junior senator was so headstrong that he had gone out his way to criticize the president of his own party."<ref>{{Cite book |title=Goldwater: the man who made a revolution |last=Edwards |first=Lee |publisher=Regnery Publishing |year=1995 |isbn=0895264714 |location=Washington, D.C. |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/goldwater00leee/page/89 }}</ref> There was a Democratic majority in Congress for most of Eisenhower's career and Goldwater felt that ] was compromising too much with Democrats in order to get legislation passed. Early on in his career as a senator for Arizona, he criticized the $71.8 billion budget that President Eisenhower sent to Congress, stating "Now, however, I am not so sure. A $71.8 billion budget not only shocks me, but it weakens my faith."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus |last=Perlstein |first=Rick |publisher=Nation Books |year=2009 |isbn=1568584121 |location= |page=33 |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/938852638}}</ref> Goldwater opposed Eisenhower's pick of ] for Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. "The day that Eisenhower appointed Governor Earl Warren of California as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Goldwater did not hesitate to express his misgivings."<ref>Edwards, p 57</ref> Goldwater and the Eisenhower administration supported the integration of schools in the south, but Goldwater felt the states should choose how they wanted to integrate and should not be forced by the federal government. "Goldwater criticized the use of federal troops. He accused the Eisenhower administration of violating the Constitution by assuming powers reserved by the states. While he agreed that under the law, every state should have integrated its schools, each state should integrate in its own way."<ref>Edwards, p 233</ref> There were high-ranking government officials following Goldwater's critical stance on the Eisenhower administration, even an Army General. "Fulbright's startling revelation that military personnel were being indoctrinated with the idea that the policies of the Commander in Chief were treasonous dovetailed with the return to the news of the strange case of General ]."<ref>Perlstein, p 147</ref> | |||

| == |

==1964 presidential election== | ||

| {{See also|1964 United States presidential election}} | |||

| In 1964, Goldwater fought and won a multi-candidate race for the Republican Party's presidential nomination. His main rival was New York Governor ], whom he defeated by a narrow margin in the California primary. Eisenhower gave his support to Goldwater when he told reporters, "I personally believe that Goldwater is not an extremist as some people have made him, but in any event we're all Republicans."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Before the storm : Barry Goldwater and the unmaking of the American consensus|last=Perlstein|first= Rick|date=2009|publisher=Nation|year=|isbn=9781568584126|location=|pages=344|oclc=938852638}}</ref> His nomination was opposed by liberal Republicans, who thought Goldwater's demand for ] the ], would foment a ]. He delivered a captivating acceptance speech, to which "he devoted more care...than to any other speech in his political career. And with good reason: he would deliver it to the largest and most attentive audience of his life. No other statement of the 1950s and 1960s, including ''The Conscience of a Conservative'', presents more truly Barry Goldwater's basic beliefs and his positions on current issues."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Goldwater : the man who made a revolution|last=Lee|first=Edwards|publisher=Regnery Publishing|year=1995|isbn=0895264714|location=Washington, D.C.|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/goldwater00leee/page/267}}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater's direct style had made him extremely popular with the Republican Party's suburban conservative voters, based in the ] and the senator's native ]. Following the success of '']'', Goldwater became the frontrunner for the GOP Presidential nomination to run against ].<ref>Aranha, Gerard V, "JFK and Goldwater", The Chicago Tribune www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1998-06-14-9806140015-story.html June 14, 1998, Retrieved December 13, 2020</ref> Despite their disagreements on politics, Goldwater and Kennedy had grown to become close friends during the eight years they served alongside each other in the Senate. With Goldwater the clear GOP frontrunner, he and Kennedy began planning to campaign together, holding ] across the country and avoiding a race defined by the kind of negative attacks that were increasingly coming to define American politics.<ref>''id''.</ref><ref>Goldwater told the New York paper ''Newsday'' about the agreement in 1973, saying "We talked about it. We both thought it was a great idea," "Goldwater Tells Plan to Stump With Kennedy", ''Los Angeles Times'', June 8, 1973, p. I-17</ref> | |||

| ] with Senator Goldwater, January 16, 1964]] | |||

| ==={{Anchor|Republican Primary}} Republican primary=== | |||

| === 1964 presidential campaign === | |||

| {{See also|Barry Goldwater 1964 presidential campaign|1964 |

{{See also|Barry Goldwater 1964 presidential campaign|1964 Republican Party presidential primaries}} | ||

| [[File:1964RepublicanPresidentialPrimaries.svg|thumb|300px|Republican primaries results by state | [[File:1964RepublicanPresidentialPrimaries.svg|thumb|300px|Republican primaries results by state | ||

| {{col-begin}} | {{col-begin}} | ||

| Line 123: | Line 133: | ||

| {{col-end}} | {{col-end}} | ||

| In South Dakota and Florida, Goldwater finished second to "unpledged delegates", but he finished before all other candidates]] | In South Dakota and Florida, Goldwater finished second to "unpledged delegates", but he finished before all other candidates]] | ||

| At the time of Goldwater's presidential candidacy, the Republican Party was split between its conservative wing (based in the West and South) and moderate/liberal wing, sometimes called ]s (based in the Northeast). Goldwater alarmed even some of his fellow partisans with his brand of staunch ] and militant ]. He was viewed by many traditional Republicans as being too far on the right wing of the political spectrum to appeal to the mainstream majority necessary to win a national election. As a result, moderate Republicans recruited a series of opponents, including ] Governor ], ], of ] and ] Governor ], to challenge him. Goldwater would defeat Rockefeller in the winner-take-all California primary and secure the nomination. He also had a solid backing from Southern Republicans. A young ] lawyer, ], secured commitments from 271 of 279 Southern convention delegates to back Goldwater. Grenier would serve as executive director of the national GOP during the Goldwater campaign, the number 2 position to party chairman ] of Arizona. | |||

| Goldwater was grief-stricken{{Sfn | Goldwater | 1980 | p = 161 | ps =: "When that assassin's bullet ended the life of John Fitzgerald Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963, it was for me a great personal loss."}} by the ] and was greatly disappointed that his opponent in 1964 would not be Kennedy but instead his vice president, former Senate Majority Leader ] of Texas.<ref name="test">{{citation | url = http://www.mrconservativegoldwaterongoldwater.com/ | title = Mr. Conservative: Goldwater on Goldwater | publisher = HBO | type = documentary film| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140407105013/http://www.mrconservativegoldwaterongoldwater.com/ | archive-date = April 7, 2014 }}</ref> Goldwater disliked Johnson, later telling columnist John Kolbe that Johnson had "used every dirty trick in the bag."<ref>Iverson, Peter (1997) ''.'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 118. {{ISBN|0806129581}}.</ref> | |||

| Journalist John Adams says, "his acceptance speech was bold, reflecting his conservative views, but not irrational. Rather than shrinking from those critics who accuse him of extremism, Goldwater challenged them head-on" in his acceptance speech at the 1964 Republican Convention.<ref>{{cite book|author=Adams, John |title=In the Trenches: Adventures in Journalism and Public Affairs|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hsALOP-k6-gC&pg=PA73|year=2012|pages=73–|isbn=9781462067831}}</ref> In his own words: | |||

| {{quote|I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.<ref>{{cite book|author=Andrews, Robert ed.|title=Famous Lines: A Columbia Dictionary of Familiar Quotations|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MtciwlIG3sMC&pg=PA159|year=1997|page=159|isbn=9780231102186}}</ref>}} | |||

| At the time of Goldwater's presidential candidacy, the Republican Party was split between its conservative wing (based in the West and South) and moderate/liberal wing, sometimes called ]s (based in the Northeast and Midwest). Goldwater alarmed even some of his fellow partisans with his brand of staunch ] and militant ]. He was viewed by many moderate and liberal Republicans as being too far on the right wing of the political spectrum to appeal to the mainstream majority necessary to win a national election. As a result, moderate and liberal Republicans recruited a series of opponents, including New York Governor ], ], of ] and ] Governor ], to challenge him. Goldwater received solid backing from most of the few Southern Republicans then in politics. A young ] lawyer, ], secured commitments from 271 of 279 Southern convention delegates to back Goldwater. Grenier would serve as executive director of the national GOP during the Goldwater campaign, the number two position to party chairman ] of Arizona. Goldwater fought and won a multi-candidate race for the Republican Party's presidential nomination. | |||

| His paraphrase of ] was included at the suggestion of ], though the speech was primarily written by ]. Because of President Johnson's popularity, Goldwater refrained from attacking the president directly. He did not mention Johnson by name at all in his convention speech. | |||

| ===1964 Republican National Convention=== | |||

| {{See also|1964 Republican National Convention}} | |||

| Eisenhower gave his support to Goldwater when he told reporters, "I personally believe that Goldwater is not an extremist as some people have made him, but in any event we're all Republicans."<ref>{{cite book|title=Before the storm : Barry Goldwater and the unmaking of the American consensus|url=https://archive.org/details/beforestormbarry0000perl_k0s0|url-access=registration|last=Perlstein|first= Rick|date=2009|publisher=Nation|isbn=978-1568584126|page=|oclc=938852638}}</ref> His nomination was staunchly opposed by the so-called ], who thought Goldwater's demand for ] the ] would foment a ]. In addition to Rockefeller, prominent Republican office-holders refused to endorse Goldwater's candidacy, including both Republican senators from New York ] and ], ] governor ], Michigan governor ] and Congressman ] (]).<ref>"Lindsay Rejects National Ticket; To Run on His Own; He Attacks Positions Taken by G.O.P. Convention in Nominating Goldwater", The New York Times, August 4, 1964, Retrieved December 13, 2020, www.nytimes.com/1964/08/04/archives/lindsay-rejegts-national-ticket-to-run-on-his-own-he-attacks.html</ref> Rockefeller Republican ] walked out of the convention in disgust over Goldwater's nomination. ], who was ]'s running mate in 1960, also opposed Goldwater, calling his proposal of realigning the Democrat and Republican parties into two Liberal and Conservative parties "totally abhorrent" and thought that no one in their right mind should oppose the federal government in having a role in the future of America.<ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-jackie-robinson-100-politics-mlk-nixon-0131-20190130-story.html|title = Jackie Robinson fought for a racially inclusive GOP|website = ]| date=January 30, 2019 |access-date = December 23, 2020|archive-date = January 20, 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210120052854/https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-jackie-robinson-100-politics-mlk-nixon-0131-20190130-story.html|url-status = live}}</ref><ref>"Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus", Rick Perlstein, 2009</ref><ref>"Lodge Denounces Party Realigning; "Totally abhorrent", he says of Goldwater's proposal"", New York Times, November 16, 1964</ref> | |||

| In the face of such opposition, Goldwater delivered a well-received acceptance speech. According to the author ]: " devoted more care than to any other speech in his political career. And with good reason: he would deliver it to the largest and most attentive audience of his life."<ref>{{cite book|title=Goldwater : the man who made a revolution|last=Lee|first=Edwards|publisher=Regnery Publishing|year=1995|isbn=0895264714|location=Washington, D.C.|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/goldwater00leee/page/267}}</ref> Journalist John Adams commented: "his acceptance speech was bold, reflecting his conservative views, but not irrational. Rather than shrinking from those critics who accuse him of extremism, Goldwater challenged them head-on" in his acceptance speech at the 1964 Republican Convention.<ref>{{cite book|author=Adams, John|title=In the Trenches: Adventures in Journalism and Public Affairs|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hsALOP-k6-gC&pg=PA73|year=2012|pages=73–|publisher=iUniverse |isbn=978-1462067831|access-date=July 11, 2016|archive-date=November 21, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161121234759/https://books.google.com/books?id=hsALOP-k6-gC&pg=PA73|url-status=live}}</ref> In his own words: | |||

| {{blockquote|I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue! <ref>{{cite book |editor=Andrews, Robert |title=Famous Lines: A Columbia Dictionary of Familiar Quotations |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MtciwlIG3sMC&pg=PA159 |year=1997 |page=159 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0231102186 |access-date=July 11, 2016 |archive-date=November 21, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161121143456/https://books.google.com/books?id=MtciwlIG3sMC&pg=PA159 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{YouTube |id=OQ-7g52P7j0 |t=43m55s |title=1964 Barry Goldwater GOP Convention Acceptance Speech, at 43m55s}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://nationalcenter.org/ncppr/2001/11/04/barry-goldwaters-republican-convention-speech-1964/ |last=Hess |first=Karl |date=November 4, 2001 |website=nationalcenter.org |publisher=National Center for Public Policy Research |title=Barry Goldwater's 1964 Acceptance Speech Republican Presidential Nomination 1964 Republican National Convention Cow Palace San Francisco |access-date=June 27, 2022 |quote=}}</ref>}} | |||

| His paraphrase of ] was included at the suggestion of ], though the speech was primarily written by ]. Because of President Johnson's popularity, Goldwater refrained from attacking the president directly. He did not mention Johnson by name at all in his convention speech.{{citation needed|date=June 2023}} | |||

| Although raised as an ],<ref>{{cite book|author=Kurt F. Stone|title=The Jews of Capitol Hill: A Compendium of Jewish Congressional Members|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ACTF56SnaykC&pg=PA191|year=2010|publisher=Scarecrow Press|page=191|isbn=978-0810877382}}</ref> Goldwater was the first candidate of ] descent, through his father, to be nominated for president by a major American party.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Evans|first1=Harold|last2=Buckland|first2=Gail|last3=Baker|first3=Kevin|date=1998|title=The American Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=a013AAAAMAAJ|publisher=Knopf|page=515|isbn=0679410708|quote=The first major candidate known to be of ethnic Jewish origin, Goldwater used to joke that only half of him could join an exclusive country club.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Murray Friedman|title=The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy|publisher=Cambridge University Press|date=2006|pages=96–97|quote=Goldwater did not run as a Jew and did not seek the support of other Jews. He did not go out of his way to support Israel, either. On the other hand, he never disavowed his Jewish antecedents. ... Whether Goldwater should be seen as Jewish is an open question. }}</ref> | |||

| ===General election campaign=== | |||

| ] with Senator Goldwater, January 16, 1964]] | |||

| After securing the Republican presidential nomination, Goldwater chose his political ally, ] Chairman ] to be his running mate. Goldwater joked he chose Miller because "he drives Johnson nuts".<ref name="Perlstein">{{cite book |first=Rick |last=Perlstein |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DG3BE0C0VkAC&pg=PA389 |title=Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus |year=2002 |page=389 |publisher=PublicAffairs |isbn=978-0786744152 |via=] |access-date=January 5, 2022 |archive-date=January 5, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220105174419/https://books.google.com/books?id=DG3BE0C0VkAC&pg=PA389 |url-status=live }}</ref> In choosing Miller, Goldwater opted for a running mate who was ideologically aligned with his own conservative wing of the Republican party. Miller ] in other ways, being a practicing Catholic from the East Coast.<ref name="Perlstein"/> Miller had low name recognition<ref name="Perlstein"/> but was popular in the Republican party and viewed as a skilled political strategist.<ref name="Spurned">{{cite news |last=Weaver |first=Warren Jr |date=September 6, 1964 |title=Miller Spurned the Usual Road to Political Advancement |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1964/09/06/118536966.html?pageNumber=44 |work=] |location=New York, NY |via=] |access-date=January 5, 2022 |archive-date=June 19, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220619194249/https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1964/09/06/118536966.html?pageNumber=44 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] speaks for presidential candidate Goldwater in Los Angeles, 1964]] | |||

| Former U.S. Senator ], a ] from ], was a friend of Goldwater and supported him in the general election campaign. Bush's son, ] (then running for the Senate from Texas against Democrat ]), was also a strong Goldwater supporter in both the nomination and general election campaigns. | |||

| Former U.S. senator ], a ] from ], was a friend of Goldwater and supported him in the general election campaign. | |||

| Future Chief Justice of the United States and fellow Arizonan ] also first came to the attention of national Republicans through his work as a legal adviser to Goldwater's presidential campaign. Rehnquist had begun his law practice in 1953 in the firm of ] of Phoenix, Goldwater's national campaign manager and friend of nearly three decades.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2002/oct/24/local/me-kitchel24|title=Denison Kitchel, 94; Ran Goldwater's Presidential Bid|date=October 24, 2002|first=Dennis|last=McLellan|work=]|accessdate=June 2, 2013|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131106065221/http://articles.latimes.com/2002/oct/24/local/me-kitchel24|archivedate=November 6, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Future chief justice of the United States and fellow Arizonan ] also first came to the attention of national Republicans through his work as a legal adviser to Goldwater's presidential campaign. Rehnquist had begun his law practice in 1953 in the firm of ] of Phoenix, Goldwater's national campaign manager and friend of nearly three decades.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-oct-24-me-kitchel24-story.html|title=Denison Kitchel, 94; Ran Goldwater's Presidential Bid|date=October 24, 2002|first=Dennis|last=McLellan|work=]|access-date=June 2, 2013|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131106065221/http://articles.latimes.com/2002/oct/24/local/me-kitchel24|archive-date=November 6, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater was painted as a dangerous figure by the Johnson campaign, which countered Goldwater's slogan "In your heart, you know he's right" with the lines "In your guts, you know he's nuts," and "In your heart, you know he might" (that is, he might actually use nuclear weapons as opposed to using only ]). Johnson himself did not mention Goldwater in his own acceptance speech at the ]. | |||

| Goldwater's |

Goldwater's advocacy of active interventionism to prevent the spread of communism and defend American values and allies led to effective counterattacks from ] and his supporters, who said that Goldwater's militancy would have dire consequences, possibly even nuclear war. In a May 1964 speech, Goldwater suggested that nuclear weapons should be treated more like conventional weapons and used in ], specifically that they should have been used at ] in 1954 to defoliate trees.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Nuclear Weapons and the Vietnam War |url=http://www.watsoninstitute.org/pub/vietnam_weapons.pdf |last=Tannenwald |first=Nina |s2cid=153628491 |journal=The Journal of Strategic Studies |volume=29 |issue=4 |year=2006 |pages=675–722 |doi=10.1080/01402390600766148 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131101174405/http://www.watsoninstitute.org/pub/vietnam_weapons.pdf |archive-date=November 1, 2013 |url-status=dead |access-date=May 8, 2013 }}</ref> Regarding Vietnam, Goldwater charged that Johnson's policy was devoid of "goal, course, or purpose," leaving "only sudden death in the jungles and the slow strangulation of freedom".<ref>Matthews 2002</ref> Goldwater's rhetoric on nuclear war was viewed by many as quite uncompromising, a view buttressed by off-hand comments such as, "Let's lob one into the men's room at the ]."<ref>{{cite magazine |magazine=Harper's Magazine |url=http://www.mindfully.org/Reform/2004/Republican-Propaganda1sep04.htm|archive-url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20091012003831/http://www.mindfully.org/Reform/2004/Republican-Propaganda1sep04.htm|title=Tentacles of Rage: The Republican propaganda mill, a brief history|author=Lapham, Lewis H. |volume=309|issue=1852|date= September 2004 |archive-date=October 12, 2009}}</ref> He also advocated that field commanders in Vietnam and Europe should be given the authority to use ]s (which he called "small conventional nuclear weapons") without presidential confirmation.<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rUwEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA11-IA1 |title=Our Defense: a Crucial Issue for Candidates |magazine=Life |date=September 25, 1964 |page=11 |access-date=March 3, 2012 |archive-date=May 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210524183100/https://books.google.com/books?id=rUwEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA11-IA1 |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Goldwater countered the Johnson attacks by criticizing the administration for its perceived ethical lapses, and stating in a commercial that "we, as a nation, are not far from the kind of moral decay that has brought on the fall of other nations and people.... I say it is time to put conscience back in government. And by good example, put it back in all walks of American life." Goldwater campaign commercials included statements of support by actor ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/raymond-massey |title=Goldwater ad |publisher=Livingroomcandidate.org |date=September 7, 1964 |accessdate=March 3, 2012|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131020013322/http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/raymond-massey |archivedate=October 20, 2013 }}</ref> and moderate Republican senator ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/senator-margaret-chase |title=Goldwater ad |publisher=Livingroomcandidate.org |date=September 7, 1964 |accessdate=March 3, 2012|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131020013323/http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/senator-margaret-chase |archivedate=October 20, 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| Goldwater countered the Johnson attacks by criticizing the administration for its perceived ethical lapses, and stating in a commercial that "we, as a nation, are not far from the kind of moral decay that has brought on the fall of other nations and people.... I say it is time to put conscience back in government. And by good example, put it back in all walks of American life." Goldwater campaign commercials included statements of support by actor ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/raymond-massey |title=Goldwater ad |publisher=Livingroomcandidate.org |date=September 7, 1964 |access-date=March 3, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131020013322/http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/raymond-massey |archive-date=October 20, 2013 }}</ref> and moderate Republican senator ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/senator-margaret-chase |title=Goldwater ad |publisher=Livingroomcandidate.org |date=September 7, 1964 |access-date=March 3, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131020013323/http://www.livingroomcandidate.org/commercials/1964/senator-margaret-chase |archive-date=October 20, 2013 }}</ref> | |||