| Revision as of 21:23, 10 January 2012 editClueBot NG (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers6,440,436 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by 184.100.8.148 to version by William Avery. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (806452) (Bot)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:11, 13 January 2025 edit undoR Prazeres (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users30,986 edits Reverted 2 edits by Weird Commenter (talk): Unexplained reverts + edit-warringTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Capital of the Eastern Roman and Ottoman empires}} | |||

| {{two other uses|the city before the ] (1453)|a more detailed approach after 1453|History of Istanbul}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{redirect2|Constantinopolis|Konstantinoupolis|the town in ancient Osrhoene|Constantia (Osrhoene)|the newspaper|Konstantinoupolis (newspaper){{!}}''Konstantinoupolis'' (newspaper)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2023}} | |||

| '''Constantinople''' ({{lang-el|Κωνσταντινούπολις}}, ''Kōnstantinoúpolis''; {{lang-la|Nova Roma}} or ''Constantinopolis''; Ottoman Turkish: قسطنطینیه, ''Kostantiniyye'' and modern Turkish: '']'') was the ] of the ], ], ], ], and ]s. Throughout most of the ], Constantinople was Europe's largest<ref>Pounds, Norman John Greville. ''An Historical Geography of Europe, 1500-1840'', p. 124. CUP Archive, 1979. ISBN 0521223792.</ref> and wealthiest city. | |||

| {{Infobox ancient site | |||

| | name = Constantinople | |||

| | native_name = {{native name|grc|Κωνσταντινούπολις}}<br/>{{native name|la|Constantinopolis}}<br/>{{native name|ota|قسطنطينيه}} | |||

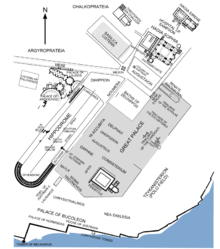

| | image = Byzantine Constantinople-en.png | |||

| | alt = | |||

| | caption = Map of Constantinople in the Byzantine period, corresponding to the modern-day ] and ] district of ] | |||

| | map_type = Istanbul#Turkey Marmara#Turkey | |||

| | map_alt = A map of Byzantine Istanbul | |||

| | map_size = 275 | |||

| | map_caption = Constantinople was founded on the former site of the ] of ], which today is known as ] in ]. | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|41|00|45|N|28|58|48|E|type:city_region:TR|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | location = ] and ], ], Turkey | |||

| | region = ] | |||

| | type = Imperial city | |||

| | part_of = {{unbulleted list|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | length = | |||

| | width = | |||

| | area = {{cvt|6|km2}} enclosed within Constantinian Walls | |||

| {{cvt|14|km2}} enclosed within Theodosian Walls | |||

| <!-- find good source for this claim and discuss in article's text --> | |||

| | height = | |||

| | builder = ] | |||

| | material = | |||

| | built = 11 May 330 | |||

| | abandoned = | |||

| | epochs = ] to ] | |||

| | cultures = {{unbulleted list| ]|]|]{{Broken anchor|date=2024-07-19|bot=User:Cewbot/log/20201008/configuration|target_link=Byzantine Empire#Culture|reason= The anchor (Culture) ].}}|]}} | |||

| | event = ], including fall of the city (] and ]) | |||

| | occupants = | |||

| | designation1 = WHS | |||

| | designation1_offname = ] | |||

| | designation1_type = Cultural | |||

| | designation1_criteria = (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) | |||

| | designation1_date = 1985 <small>(9th ])</small> | |||

| | designation1_number = | |||

| | designation1_free1name = Extension | |||

| | designation1_free1value = 2017 | |||

| | designation1_free2name = Area | |||

| | designation1_free2value = 765.5 ha | |||

| | designation1_free3name = UNESCO region | |||

| | designation1_free3value = ] | |||

| |}} | |||

| {{Timeline of Constantinople}} | |||

| '''Constantinople'''{{efn|{{Bulleted list|{{IPAc-en|lang|ˌ|k|ɒ|n|s|t|æ|n|t|ᵻ|ˈ|n|oʊ|p|əl}} {{Respell|KON|stan|tin|OH|pəl}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Roach |first=Peter |title=Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2011 |isbn=978-0-521-15253-2 |edition=18th |location=Cambridge}}</ref> |{{Langx|grc-x-koine|Κωνστᾰντῑνούπολῐς|Kōnstăntīnoúpolĭs}}, {{IPA|grc-x-medieval|konstandiˈnupolis|link=yes}}|{{langx|la|Cōnstantīnopolis}}, {{IPA|la|kõːstantiːˈnɔpɔlɪs|pron}}|{{langx|ota|قسطنطينيه|Ḳosṭanṭīnīye}}}}}} (]) was a historical city located on the ] that served as the capital of the ], ], ], and ] empires between its consecration in 330 until 1930, when it was renamed to ]. Initially as ], Constantinople was founded in 324 during the reign of ] on the site of the existing settlement of ], and shortly thereafter in 330 became the capital of the Roman Empire. Following the collapse of the ] in the late 5th century, Constantinople remained the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the ]; 330–1204 and 1261–1453), the ] (1204–1261), and the ] (1453–1922). Following the ], the Turkish capital then moved to ]. Officially renamed ] in 1930, the city is today the ], straddling the ] and lying in both Europe and Asia, and the financial center of ]. | |||

| In 324, following the reunification of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, the ancient city of ] was selected to serve as the new capital of the Roman Empire, and the city was renamed Nova Roma, or 'New Rome', by Emperor ]. On 11 May 330, it was renamed Constantinople and dedicated to Constantine.<ref name="ODB">{{ODB |title=Constantinople |last=Mango |first=Cyril |author link=Cyril Mango |pages=508–512}}</ref> Constantinople is generally considered to be the center and the "cradle of Orthodox ]".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Parry |first=Ken |title=Christianity: Religions of the World |publisher=Infobase Publishing |year=2009 |isbn=9781438106397 |page=139}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Parry |first=Ken |title=The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=2010 |isbn=9781444333619 |page=368}}</ref> From the mid-5th century to the early 13th century, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe.<ref>Pounds, Norman John Greville. ''An Historical Geography of Europe, 1500–1840'', p. 124. CUP Archive, 1979. {{ISBN|0-521-22379-2}}.</ref> The city became famous for its architectural masterpieces, such as ], the cathedral of the ], which served as the seat of the ]; the sacred ], where the emperors lived; the ]; the ] of the Land Walls; and opulent aristocratic palaces. The ] was founded in the 5th century and contained artistic and literary treasures before it was sacked in 1204 and 1453,<ref>Janin (1964), '']''</ref> including its vast ] which contained the remnants of the ] and had 100,000 volumes.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Preserving The Intellectual Heritage--Preface • CLIR |url=https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/bellagio/bellag1/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171020090658/https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/bellagio/bellag1.html |archive-date=2017-10-20 |access-date=2021-06-09 |website=CLIR}}</ref> The city was the home of the ] and guardian of ]'s holiest relics, such as the ] and the ]. | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| {{main|Names of Istanbul}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The city was originally founded as a Greek colony under the name of '']'' in the 7th century BC. It took on the name of ''Konstantinoupolis'' ("city of Constantine", ''Constantinople'') after its re-foundation under Roman emperor ], who designated it as his new Roman capital. The modern Turkish name ''İstanbul'' derives from the Greek phrase ''eis tin polin'' (εις την πόλιν), meaning "in the City" or "to the City". This name was used in Turkish side by side with ''Kostantiniyye'', the more formal Arabic–Persian adaptation of the original ''Constantinople'', during the period of Ottoman rule, while western languages mostly continued to refer to the city as Constantinople until the early 20th century. After the creation of the ] in 1923, the Turkish government began to formally object to the use of ''Constantinople'' in other languages and ask that others use the more common name for the city.<ref>Tom Burham, ''The Dictionary of Misinformation'', Ballantine, 1977.</ref><ref>.</ref><ref>Room, Adrian, (1993), ''Place Name changes 1900-1991'', Metuchen, N.J., & London:The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0-8108-2600-3 pp. 46, 86.</ref><ref>.</ref><ref>.</ref> | |||

| Constantinople was famous for its massive and complex fortifications, which ranked among the most sophisticated defensive architectures of ]. The ] consisted of a double wall lying about {{convert|2|km||abbr=out}} to the west of the first wall and a moat with palisades in front.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Treadgold |first=Warren |url=https://archive.org/details/historybyzantine00trea_749 |title=A History of Byzantine State and Society |publisher=Stanford University Press |year=1997 |location=Stanford, CA |page= |url-access=limited}}</ref> Constantinople's location between the ] and the ] reduced the land area that needed defensive walls. The city was built intentionally to rival ], and it was claimed that several elevations within its walls matched Rome's 'seven hills'.<ref>] writes: "To identity them all needs a good deal more credulity and imagination than is required for their Roman counterparts." ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'' (1989), Guildhall Publishing, p. 76n</ref> The impenetrable defenses enclosed magnificent palaces, domes, and towers, the result of prosperity Constantinople achieved as the gateway between two continents (] and ]) and two seas (the Mediterranean and the Black Sea). Although besieged on numerous occasions by various armies, the defenses of Constantinople proved impenetrable for nearly nine hundred years. | |||

| In 1204, however, the armies of the ] took and devastated the city, and for several decades, its inhabitants resided under ] in a dwindling and depopulated city. In 1261, the Byzantine Emperor ] liberated the city, and after the restoration under the ] dynasty, it enjoyed a partial recovery. With the advent of the Ottoman Empire in 1299, the Byzantine Empire began to lose territories, and the city began to lose population. By the early 15th century, the Byzantine Empire was reduced to just Constantinople and its environs, along with ] in Greece, making it an enclave inside the Ottoman Empire. The city was finally ] by the Ottoman Empire in 1453, remaining under its control until the early 20th century, after which it was renamed Istanbul under the Empire's ], Turkey. | |||

| == Names == | |||

| ] built in AD 537, during the reign of ].]] | |||

| === Before Constantinople === | |||

| According to ] in his '']'', the first known name of a settlement on the site of Constantinople was ''Lygos'',<ref>{{usurped|1=}}. Quote: "On leaving the Dardanelles we come to the Bay of Casthenes, ... and the promontory of the Golden Horn, on which is the town of Byzantium, a free state, formerly called Lygos; it is 711 miles from Durazzo,..."</ref> a settlement likely of ] origin founded between the 13th and 11th centuries BC.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |year=1908 |title=Constantinople |encyclopedia=Catholic Encyclopedia |publisher=Robert Appleton Company |location=New York |url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04301a.htm |access-date=2007-09-12 |last=Vailhé |first=S. |volume=4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100722013539/http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04301a.htm |archive-date=2010-07-22 |url-status=live}}</ref> The site, according to the founding myth of the city, was abandoned by the time Greek settlers from the city-state of ] founded '']'' ({{langx|grc|Βυζάντιον}}, ''Byzántion'') in around 657 BC,<ref name="roo177">{{Cite book |last=Room |first=Adrian |title=Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features, and Historic Sites |publisher=McFarland & Company |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-7864-2248-7 |edition=2nd |location=Jefferson, N.C. |page=177}}</ref> across from the town of ] on the Asiatic side of the Bosphorus. | |||

| The origins of the name of '']'', more commonly known by the later Latin ''Byzantium'', are not entirely clear, though some suggest it is of ] origin.<ref>Janin, Raymond (1964). ''Constantinople byzantine''. Paris: Institut Français d'Études Byzantines. p. 10f.</ref><ref name="johns">Georgacas, Demetrius John (1947). "The Names of Constantinople". ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' (The Johns Hopkins University Press) '''78''': 347–67. {{doi|10.2307/283503}}. {{JSTOR|283503}}.</ref> The founding myth of the city has it told that the settlement was named after the leader of the Megarian colonists, ]. The later Byzantines of Constantinople themselves would maintain that the city was named in honor of two men, Byzas and Antes, though this was more likely just a play on the word ].{{sfn|Harris|2017|pages=25–26}} | |||

| The city was briefly renamed ''Augusta Antonina'' in the early 3rd century AD by the Emperor ] (193–211), who razed the city to the ground in 196 for supporting a ] in the ] and had it rebuilt in honor of his son Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (who succeeded him as Emperor), popularly known as ].{{sfn|Harris|2017|page=43}}<ref name="IA">Necdet Sakaoğlu (1993/94a): "İstanbul'un adları" . In: 'Dünden bugüne İstanbul ansiklopedisi', ed. Türkiye Kültür Bakanlığı, Istanbul.</ref> The name appears to have been quickly forgotten and abandoned, and the city reverted to Byzantium/Byzantion after either the assassination of Caracalla in 217 or, at the latest, the fall of the ] in 235. | |||

| === Names of Constantinople === | |||

| {{Main|Names of Istanbul{{!}}Names of Constantinople}} | |||

| ], built by ] in 330 to commemorate the establishment of Constantinople as the ] of the ]]] | |||

| Byzantium took on the name of Constantinople (]: Κωνσταντινούπολις, ]: ''Kōnstantinoupolis;'' "city of Constantine") after its refoundation under ] ], who transferred the capital of the ] to Byzantium in 330 and designated his new capital officially as '']'' ({{lang|grc|Νέα Ῥώμη}}) 'New Rome'. During this time, the city was also called 'Second Rome', 'Eastern Rome', and ''Roma Constantinopolitana'' (] for 'Constantinopolitan Rome').<ref name="johns"/> As the city became the sole remaining capital of the Roman Empire after the fall of the West, and its wealth, population, and influence grew, the city also came to have a multitude of nicknames. | |||

| ] found in ], might have belonged to a ] at the ] built by ].]] | |||

| As the largest and wealthiest city in Europe during the 4th–13th centuries and a center of culture and education of the Mediterranean basin, Constantinople came to be known by prestigious titles such as ''Basileuousa'' (Queen of Cities) and ''Megalopolis'' (the Great City) and was, in colloquial speech, commonly referred to as just ''Polis'' ({{lang|grc|ἡ Πόλις}}) 'the City' by Constantinopolitans and provincial Byzantines alike.<ref>Harris, 2007, p. 5</ref> | |||

| In the language of other peoples, Constantinople was referred to just as reverently. The medieval Vikings, who had contacts with the empire through their expansion in eastern Europe (]), used the Old Norse name ''Miklagarðr'' (from ''mikill'' 'big' and ''garðr'' 'city'), and later ''Miklagard'' and ''Miklagarth''.{{sfn|Harris|2017|page=1}} In Arabic, the city was sometimes called ''Rūmiyyat al-Kubra'' (Great City of the Romans) and in Persian as ''Takht-e Rum'' (Throne of the Romans). | |||

| In East and South Slavic languages, including in ], Constantinople has been referred to as '']'' (''Царьград'') or ''Carigrad'', 'City of the Caesar (Emperor)', from the Slavonic words ''tsar'' ('Caesar' or 'King') and ''grad'' ('city'). This was presumably a ] on a Greek phrase such as {{lang|grc|Βασιλέως Πόλις}} (''Vasileos Polis''), 'the city of the emperor '. | |||

| In ] the city was also called ''Asitane'' (the Threshold of the State), and in ], it was called ''Gosdantnubolis'' (City of Constantine).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Everett-Heath |first=John |url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191882913.001.0001/acref-9780191882913;jsessionid=888EB32E38583EE8E0B91B8F5DDD5536 |title=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names |date=2019-10-24 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-188291-3 |language=en-US |doi=10.1093/acref/9780191882913.001.0001 |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=26 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230326031024/https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780191882913.001.0001/acref-9780191882913;jsessionid=888EB32E38583EE8E0B91B8F5DDD5536 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Modern names of the city === | |||

| ] is the Ancient Egyptian obelisk of Egyptian King ] re-erected in the ] by the Roman emperor ] in the 4th century AD.]] | |||

| The modern Turkish name for the city, '']'', derives from the ] phrase ''eis tin Polin'' ({{lang|grc|εἰς τὴν πόλιν}}), meaning '(in)to the city'.{{sfn|Harris|2017|page=204}}<ref>{{OEtymD|Istanbul}}</ref> This name was used in colloquial speech in ] alongside ''Kostantiniyye'', the more formal adaptation of the original ''Constantinople'', during the period of ] rule, while western languages mostly continued to refer to the city as Constantinople until the early 20th century. In 1928, ] from Arabic script to Latin script. After that, as part of the ] movement, Turkey started to urge other countries to use ], instead of other transliterations to Latin script that had been used in Ottoman times and the city came to be known as Istanbul and its variations in most world languages.<ref name="Shawn">Stanford and Ezel Shaw (1977): History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Vol II, p. 386; Robinson (1965), The First Turkish Republic, p. 298</ref><ref>Tom Burham, ''The Dictionary of Misinformation'', Ballantine, 1977.</ref><ref>Room, Adrian, (1993), ''Place Name changes 1900–1991'', Metuchen, N.J., & London:The Scarecrow Press, Inc., {{ISBN|0-8108-2600-3}} pp. 46, 86.</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071218080707/http://concise.britannica.com/ebc/article-9368294/Istanbul |date=2007-12-18 }}.</ref> | |||

| The name ''Constantinople'' is still used by members of the ] in the title of one of their most important leaders, the Orthodox ] based in the city, referred to as "His Most Divine All-Holiness the Archbishop of Constantinople New Rome and Ecumenical Patriarch". In Greece today, the city is still called ''Konstantinoúpoli(s)'' ({{lang|el|Κωνσταντινούπολις/Κωνσταντινούπολη}}) or simply just "the City" ({{lang|el|Η Πόλη}}). | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{main|History of Constantinople|History of Istanbul}} | |||

| ===Byzantium=== | |||

| ] with the ] to the left and the ] to the right]]], today in ]]] | |||

| === Foundation of Byzantium === | |||

| {{Main|Byzantium}} | {{Main|Byzantium}} | ||

| ] (Greek: Μίλ(λ)ιον), a mile-marker monument]] | |||

| Constantinople was founded by the ] ] on the site of an already-existing city, ], settled in the early days of ], probably around 671-662 BC. The site lay astride the land route from ] to ] and the ] from the ] to the ], and had in the ] an excellent and spacious harbour. | |||

| Constantinople was founded by the Roman emperor ] (272–337) in 324<ref name="ODB" /> on the site of an already-existing city, ], which was settled in the early days of ], in around 657 BC, by colonists of the city-state of ]. This is the first major settlement that would develop on the site of later Constantinople, but the first known settlement was that of ''Lygos'', referred to in Pliny's Natural Histories.<ref>Pliny, IV, xi</ref> Apart from this, little is known about this initial settlement. The site, according to the founding myth of the city, was abandoned by the time Greek settlers from the city-state of Megara founded Byzantium ({{langx|grc|Βυζάντιον|Byzántion}}) in around 657 BC,<ref name="IA" /> across from the town of Chalcedon on the Asiatic side of the Bosphorus. | |||

| ===306–337=== | |||

| ] presents a representation of the city of Constantinople as tribute to an enthroned Mary and Christ Child in this church mosaic. ], c. 1000]] | |||

| ] struck by Constantine I to commemorate the founding of Constantinople]] | |||

| Constantine had altogether more colourful plans. Having restored the unity of the Empire, and, being in course of major governmental reforms as well as of ], he was well aware that Rome was an unsatisfactory capital. Rome was too far from the frontiers, and hence from the armies and the Imperial courts, and it offered an undesirable playground for disaffected politicians. Yet it had been the capital of the state for over a thousand years, and it might have seemed unthinkable to suggest that the capital be moved to a different location. Nevertheless, he identified the site of Byzantium as the right place: a place where an emperor could sit, readily defended, with easy access to the ] or the ] frontiers, his court supplied from the rich gardens and sophisticated workshops of Roman Asia, his treasuries filled by the wealthiest provinces of the Empire. | |||

| ] wrote that some "claim that people from Megara, who derived their descent from Nisos, sailed to this place under their leader Byzas, and invent the fable that his name was attached to the city". Some versions of the founding myth say Byzas was the son of a local ], while others say he was conceived by one of Zeus' daughters and ]. Hesychius also gives alternate versions of the city's founding legend, which he attributed to old poets and writers:<ref>'']''</ref> | |||

| Constantinople was built over six years, and consecrated on 11 May 330.<ref>Commemorative coins that were issued during the 330s already refer to the city as ''Constantinopolis'' (see, e.g., Michael Grant, ''The climax of Rome'' (London 1968), p. 133), or "Constantine's City". According to the ''Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum'', vol. 164 (Stuttgart 2005), column 442, there is no evidence for the tradition that Constantine officially dubbed the city "New Rome" (''Nova Roma''). It is possible that the Emperor called the city "Second Rome" ({{lang-el|Δευτέρα Ῥώμη}}, ''Deutéra Rhōmē'') by official decree, as reported by the 5th-century church historian ]: See ].</ref> Constantine divided the expanded city, like Rome, into 14 regions, and ornamented it with public works worthy of an imperial metropolis.<ref>A description can be found in the ].</ref> Yet, at first, Constantine's new Rome did not have all the dignities of old Rome. It possessed a ], rather than an ]. It had no ], ], or ]. Although it did have senators, they held the title ''clarus'', not '']'', like those of Rome. It also lacked the panoply of other administrative offices regulating the food supply, police, statues, temples, sewers, aqueducts, or other public works. The new programme of building was carried out in great haste: Columns, marbles, doors, and tiles were taken wholesale from the temples of the Empire and moved to the new city. In similar fashion, many of the greatest works of Greek and Roman art were soon to be seen in its squares and streets. The Emperor stimulated private building by promising householders gifts of land from the Imperial estates in ] and ], and on 18 May 332 he announced that, as in Rome, free distributions of food would be made to the citizens. At the time the amount is said to have been 80,000 rations a day, doled out from 117 distribution points around the city.<ref>Socrates II.13, cited by J B Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire, p. 74.</ref> | |||

| <blockquote><poem>It is said that the first Argives, after having received this prophecy from Pythia, | |||

| Blessed are those who will inhabit that holy city, | |||

| a narrow strip of the Thracian shore at the mouth of the Pontos, | |||

| where two pups drink of the gray sea, | |||

| where fish and stag graze on the same pasture, | |||

| set up their dwellings at the place where the rivers Kydaros and Barbyses have their estuaries, one flowing from the north, the other from the west, and merging with the sea at the altar of the nymph called Semestre"</poem></blockquote> | |||

| The city maintained independence as a city-state until it was annexed by ] in 512 BC into the ], who saw the site as the optimal location to construct a ] crossing into Europe as Byzantium was situated at the narrowest point in the Bosphorus strait. Persian rule lasted until 478 BC when as part of the Greek counterattack to the ], a Greek army led by the Spartan general ] captured the city which remained an independent, yet subordinate, city under the Athenians, and later to the Spartans after 411 BC.<ref>Thucydides, I, 94</ref> A farsighted treaty with the emergent power of Rome in {{circa|150 BC}} which stipulated tribute in exchange for independent status allowed it to enter Roman rule unscathed.<ref>Harris, 2007, pp. 24–25</ref> This treaty would pay dividends retrospectively as Byzantium would maintain this independent status, and prosper under peace and stability in the ], for nearly three centuries until the late 2nd century AD.<ref>Harris, 2007, p. 45</ref> | |||

| Constantine laid out a new square at the centre of old Byzantium, naming it the ]. The new senate-house (or Curia) was housed in a basilica on the east side. On the south side of the great square was erected the ] of the Emperor with its imposing entrance, the ], and its ceremonial suite known as the ]. Nearby was the vast ] for chariot-races, seating over 80,000 spectators, and the famed ]. At the western entrance to the Augustaeum was the ], a vaulted monument from which distances were measured across the Eastern Roman Empire. | |||

| Byzantium was never a major influential city-state like ], ] or ], but the city enjoyed relative peace and steady growth as a prosperous trading city because of its fortunate location. The site lay astride the land route from ] to ] and the ] from the ] to the ], and had in the ] an excellent and spacious harbor. Already then, in Greek and early Roman times, Byzantium was famous for the strategic geographic position that made it difficult to besiege and capture, and its position at the crossroads of the Asiatic-European trade route over land and as the gateway between the Mediterranean and Black Seas made it too valuable a settlement to abandon, as Emperor ] later realized when he razed the city to the ground for supporting ]'s ].<ref>Harris, 2007, pp. 44–45</ref> It was a move greatly criticized by the contemporary consul and historian ] who said that Severus had destroyed "a strong Roman outpost and a base of operations against the barbarians from Pontus and Asia".<ref>Cassius Dio, ix, p. 195</ref> He would later rebuild Byzantium towards the end of his reign, in which it would be briefly renamed ''Augusta Antonina'', fortifying it with a new city wall in his name, the Severan Wall. | |||

| From the Augustaeum led a great street, the ] (Greek: Μέση lit. "Middle "), lined with colonnades. As it descended the First Hill of the city and climbed the Second Hill, it passed on the left the ] or law-court. Then it passed through the oval ] where there was a second Senate-house and a ] with a statue of Constantine himself in the guise of ], crowned with a halo of seven rays and looking toward the rising sun. From there the Mese passed on and through the Forum of Taurus and then the Forum of Bous, and finally up the Seventh Hill (or Xerolophus) and through to the Golden Gate in the ]. After the construction of the ] in the early 5th century, it would be extended to the new ], reaching a total length of seven ]s.<ref>J B Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire, p. 75. ''et seqq''.</ref> | |||

| === 324–337: The refoundation as Constantinople === | |||

| === 395–527 === | |||

| ] Church in Istanbul]] | |||

| ] was the last ] who ruled over an undivided empire (detail from the Obelisk at the ]]] | |||

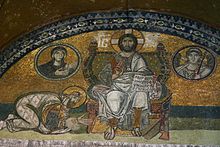

| ] presents a representation of the city of Constantinople as tribute to an enthroned Mary and Christ Child in this church mosaic. ], {{circa|1000}}.]] | |||

| The first known ] of the City of Constantinople was ], who took office on 11 December 359 and held it until 361. The emperor ] built the Palace of ] on the shore of the ] near the ], probably for use when reviewing troops. All the emperors up to ] and ] were crowned and acclaimed at the Hebdomon. ] founded the ] to house the skull of the saint (today preserved at the ] in Istanbul, Turkey), put up a memorial pillar to himself in the Forum of Taurus, and turned the ruined temple of ] into a coach house for the ]; ] built a new forum named after himself on the Mese, near the walls of Constantine. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] struck by Constantine I to commemorate the founding of Constantinople]] | |||

| Constantine had altogether more colourful plans. Having restored the unity of the Empire, and, being in the course of major governmental reforms as well as of ], he was well aware that Rome was an unsatisfactory capital. Rome was too far from the frontiers, and hence from the armies and the imperial courts, and it offered an undesirable playground for disaffected politicians. Yet it had been the capital of the state for over a thousand years, and it might have seemed unthinkable to suggest that the capital be moved to a different location. Nevertheless, Constantine identified the site of Byzantium as the right place: a place where an emperor could sit, readily defended, with easy access to the ] or the ] frontiers, his court supplied from the rich gardens and sophisticated workshops of Roman Asia, his treasuries filled by the wealthiest provinces of the Empire.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Constantinople |encyclopedia=World History Encyclopedia |url=https://www.worldhistory.org/Constantinople/ |last=Wasson |first=D. L. |date=9 April 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210628145601/https://www.worldhistory.org/Constantinople/ |archive-date=2021-06-28}}</ref> | |||

| The importance of Constantinople gradually increased. After the shock of the ] in 378, in which the emperor ] with the flower of the Roman armies was destroyed by the ] within a few days' march, the city looked to its defenses, and ] built in 413–414 the 18-meter (60-foot)-tall ], which were never to be breached until the coming of gunpowder. Theodosius also founded a ] near the Forum of Taurus, on 27 February 425. | |||

| Constantinople was built over six years, and consecrated on 11 May 330.<ref name="ODB" /><ref>Commemorative coins that were issued during the 330s already refer to the city as ''Constantinopolis'' (see, e.g., Michael Grant, ''The climax of Rome'' (London 1968), p. 133), or "Constantine's City". According to the ''Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum'', vol. 164 (Stuttgart 2005), column 442, there is no evidence for the tradition that Constantine officially dubbed the city "New Rome" (''Nova Roma''). It is possible that the Emperor called the city "Second Rome" ({{langx|grc|Δευτέρα Ῥώμη|Deutera Rhōmē|label=none}}) by official decree, as reported by the 5th-century church historian ]: See ].</ref> Constantine divided the expanded city, like Rome, into 14 regions, and ornamented it with public works worthy of an imperial metropolis.<ref>A description can be found in the ].</ref> Yet, at first, Constantine's new Rome did not have all the dignities of old Rome. It possessed a ], rather than an ]. It had no ], ], or ]. Although it did have senators, they held the title ''clarus'', not '']'', like those of Rome. It also lacked the panoply of other administrative offices regulating the food supply, police, statues, temples, sewers, aqueducts, or other public works. The new programme of building was carried out in great haste: columns, marbles, doors, and tiles were taken wholesale from the temples of the empire and moved to the new city. In similar fashion, many of the greatest works of Greek and Roman art were soon to be seen in its squares and streets. The emperor stimulated private building by promising householders gifts of land from the imperial estates in ] and ] and on 18 May 332 he announced that, as in Rome, free distributions of food would be made to the citizens. At the time, the amount is said to have been 80,000 rations a day, doled out from 117 distribution points around the city.<ref>Socrates II.13, cited by J B Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire, p. 74.</ref> | |||

| ], a prince of the ], appeared on the Danube about this time and advanced into Thrace, but he was deserted by many of his followers, who joined with the Romans in driving their king back north of the river. Subsequent to this, new walls were built to defend the city, and the fleet on the Danube improved. | |||

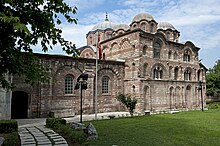

| ] is a Greek ] located in the outer courtyard of ] in Istanbul. It is one of the few churches in ] that has not been converted into a mosque.]] | |||

| Constantine laid out a new square at the centre of old Byzantium, naming it the ]. The new senate-house (or Curia) was housed in a basilica on the east side. On the south side of the great square was erected the ] of the Emperor with its imposing entrance, the ], and its ceremonial suite known as the ]. Nearby was the vast ] for chariot-races, seating over 80,000 spectators, and the famed ]. At the western entrance to the Augustaeum was the ], a vaulted monument from which distances were measured across the Eastern Roman Empire. | |||

| In due course, the ]s overran the Western Roman Empire: Its emperors retreated to ], and it diminished to nothing. Thereafter, Constantinople became in truth the largest city of the Roman Empire and of the world. Emperors were no longer peripatetic between various court capitals and palaces. They remained in their palace in the Great City, and sent generals to command their armies. The wealth of the eastern Mediterranean and western Asia flowed into Constantinople. | |||

| From the Augustaeum led a great street, the ], lined with colonnades. As it descended the First Hill of the city and climbed the Second Hill, it passed on the left the ] or law-court. Then it passed through the oval ] where there was a second Senate-house and a ] with a statue of Constantine himself in the guise of ], crowned with a halo of seven rays and looking toward the rising sun. From there, the Mese passed on and through the ] and then the ], and finally up the Seventh Hill (or Xerolophus) and through to the Golden Gate in the ]. After the construction of the ] in the early 5th century, it was extended to the new ], reaching a total length of seven ]s.<ref>J B Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire, p. 75. ''et seqq''.</ref> After the construction of the Theodosian Walls, Constantinople consisted of an area approximately the size of Old Rome within the Aurelian walls, or some 1,400 ha.{{sfn|Bogdanović|2016|pp=100}} | |||

| === 527–565 === | |||

| === 337–529: Constantinople during the Barbarian Invasions and the fall of the West === | |||

| ]<ref>''Liber insularum Archipelagi'', ], Paris.</ref> is the oldest surviving map of the city, and the only one that predates the Turkish conquest of the city in 1453]] | |||

| {{see also|Palace of Lausus}} | |||

| ] was the last ] who ruled over an undivided empire (detail from the Obelisk at the ]).]] | |||

| ], completed by Roman emperor Valens in the late 4th century AD]] | |||

| The importance of Constantinople increased, but it was gradual. From the death of Constantine in 337 to the accession of ], emperors had been resident only in the years 337–338, 347–351, 358–361, 368–369. Its status as a capital was recognized by the appointment of the first known Urban Prefect of the City Honoratus, who held office from 11 December 359 until 361. The urban prefects had concurrent jurisdiction over three provinces each in the adjacent dioceses of Thrace (in which the city was located), Pontus and Asia comparable to the 100-mile extraordinary jurisdiction of the prefect of Rome. The emperor ], who hated the city and spent only one year there, nevertheless built the Palace of ] on the shore of the ] near the ], probably for use when reviewing troops. All the emperors up to ] and ] were crowned and acclaimed at the Hebdomon. Theodosius I founded the ] to house the skull of the saint (today preserved at the ]), put up a memorial pillar to himself in the Forum of Taurus, and turned the ruined temple of ] into a coach house for the ]; ] built a new forum named after himself on the Mese, near the walls of Constantine. | |||

| The emperor ] (527–565) was known for his successes in war, for his legal reforms and for his public works. It was from Constantinople that his expedition for the reconquest of the former Diocese of Africa set sail on or about 21 June 533. Before their departure the ship of the commander ] anchored in front of the Imperial palace, and the Patriarch offered prayers for the success of the enterprise. After the victory, in 534, the ], looted by the Romans in ] and taken to ] by the ] after their sack of Rome in 455, was brought to Constantinople and deposited for a time, perhaps in the ], before being returned to ] in either the ] or the New Church.<ref>Margaret Barker, Times Literary Supplement 4 May 2007 p. 26.</ref> | |||

| After the shock of the ] in 378, in which Valens and the flower of the Roman armies were destroyed by the ] within a few days' march, the city looked to its defences, and in 413–414 ] built the 18-metre (60-foot)-tall ], which were not to be breached until the coming of gunpowder. Theodosius also founded a ] near the Forum of Taurus, on 27 February 425. | |||

| Chariot-racing had been important in Rome for centuries. In Constantinople, the hippodrome became over time increasingly a place of political significance. It was where (as a shadow of the popular elections of old Rome) the people by acclamation showed their approval of a new emperor, and also where they openly criticized the government, or clamoured for the removal of unpopular ministers. In the time of Justinian, public order in Constantinople became a critical political issue. | |||

| ], a prince of the ], appeared on the Danube about this time and advanced into Thrace, but he was deserted by many of his followers, who joined with the Romans in driving their king back north of the river. Subsequent to this, new walls were built to defend the city and the fleet on the Danube improved. | |||

| Throughout the late Roman and early Byzantine periods, Christianity was resolving fundamental questions of identity, and the dispute between the ] and the ] became the cause of serious disorder, expressed through allegiance to the horse-racing parties of the Blues and the Greens. The partisans of the Blues and the Greens were said<ref>Procopius' '' Secret History'': see P Neville-Ure, Justinian and his Age, 1951.</ref> to affect untrimmed facial hair, head hair shaved at the front and grown long at the back, and wide-sleeved tunics tight at the wrist; and to form gangs to engage in night-time muggings and street violence. At last these disorders took the form of a major rebellion of 532, known as the ] (from the battle-cry of "Victory!" of those involved). | |||

| ], now in ] in ]]] | |||

| After the ]s overran the Western Roman Empire, Constantinople became the indisputable capital city of the Roman Empire. Emperors were no longer peripatetic between various court capitals and palaces. They remained in their palace in the Great City and sent generals to command their armies. The wealth of the eastern Mediterranean and western Asia flowed into Constantinople. | |||

| Fires started by the Nika rioters consumed Constantine's basilica of St Sophia, the city's principal church, which lay to the north of the Augustaeum. Justinian commissioned ] and ] to replace it with a new and incomparable ]. This was the great cathedral of the Orthodox Church, whose dome was said to be held aloft by God alone, and which was directly connected to the palace so that the imperial family could attend services without passing through the streets.<ref>St Sophia was converted into a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of the city, and is now a museum.</ref> The dedication took place on 26 December 537 in the presence of the emperor, who exclaimed, "O ], I have outdone thee!"<ref>Source for quote: ''Scriptores originum Constantinopolitanarum'', ed T Preger I 105 (see ], ''History of the Byzantine Empire'', 1952, vol I p. 188).</ref> St Sophia was served by 600 people including 80 priests, and cost 20,000 pounds of gold to build.<ref name="cost">T. Madden, ''Crusades: The Illustrated History'', 114.</ref> | |||

| === 527–565: Constantinople in the Age of Justinian === | |||

| Justinian also had Anthemius and Isidore demolish and replace the original Church of the Holy Apostles built by Constantine with a ] under the same dedication. This was designed in the form of an equal-armed cross with five domes, and ornamented with beautiful mosaics. This church was to remain the burial place of the Emperors from Constantine himself until the 11th century. When the city fell to the Turks in 1453, the church was demolished to make room for the tomb of ]. Justinian was also concerned with other aspects of the city's built environment, legislating against the abuse of laws prohibiting building within {{convert|100|ft|m}} of the sea front, in order to protect the view.<ref>Justinian, ''Novellae'' 63 and 165.</ref> | |||

| ]<ref>''Liber insularum Archipelagi'', ], Paris.</ref> is the oldest surviving map of the city, and the only one that predates the Turkish conquest of the city in 1453.]] | |||

| ] was commissioned by Emperor ] after the previous one was destroyed in the ] of 532. It was converted into a mosque in 1453 when the Ottoman Empire commenced and was a museum from 1935 to 2020.]] | |||

| The emperor ] (527–565) was known for his successes in war, for his legal reforms and for his public works. It was from Constantinople that his expedition for the reconquest of the former Diocese of Africa set sail on or about 21 June 533. Before their departure, the ship of the commander ] was anchored in front of the Imperial palace, and the Patriarch offered prayers for the success of the enterprise. After the victory, in 534, the ], looted by the Romans in ] and taken to ] by the ] after their sack of Rome in 455, was brought to Constantinople and deposited for a time, perhaps in the ], before being returned to ] in either the ] or the New Church.<ref>Margaret Barker, Times Literary Supplement 4 May 2007, p. 26.</ref> | |||

| Chariot-racing had been important in Rome for centuries. In Constantinople, the hippodrome became over time increasingly a place of political significance. It was where (as a shadow of the popular elections of old Rome) the people by acclamation showed their approval of a new emperor, and also where they openly criticized the government, or clamoured for the removal of unpopular ministers. It played a crucial role during the riots and in times of political unrest. The Hippodrome provided a space for a crowd to be responded to positively or where the acclamations of a crowd were subverted, resorting to the riots that would ensue in coming years.<ref name="doi.org">Greatrex, Geoffrey. “The Nika Riot: A Reappraisal.” ''The Journal of Hellenic Studies'', vol. 117, 1997, pp. 60–86. {{doi|10.2307/632550}}. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.</ref> In the time of Justinian, public order in Constantinople became a critical political issue. | |||

| During Justinian I's reign, the city's population reached about 500,000 people.<ref>, Dr. Kenneth W. Harl.</ref> However, the social fabric of Constantinople was also damaged by the onset of ] between 541–542 AD. It killed perhaps 40% of the city's inhabitants.<ref>, ], November 7, 2005.</ref> | |||

| Throughout the late Roman and early Byzantine periods, Christianity was resolving fundamental questions of identity, and the dispute between the ] and the ] became the cause of serious disorder, expressed through allegiance to the chariot-racing parties of the Blues and the Greens. The partisans of the Blues and the Greens were said<ref>Procopius' '' Secret History'': see P Neville-Ure, Justinian and his Age, 1951.</ref> to affect untrimmed facial hair, head hair shaved at the front and grown long at the back, and wide-sleeved tunics tight at the wrist; and to form gangs to engage in night-time muggings and street violence. At last these disorders took the form of a major rebellion of 532, known as the ] (from the battle-cry of "Conquer!" of those involved).<ref>James Grout: , part of the ''Encyclopædia Romana''</ref> The ] began in the Hippodrome and finished there with the onslaught of over 30,000 people according to Procopius, those in the blue and green factions, innocent and guilty. This came full circle on the relationship within the Hippodrome between the power and the people during the time of Justinian.<ref name="doi.org"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Fires started by the Nika rioters consumed the Theodosian basilica of Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom), the city's cathedral, which lay to the north of the Augustaeum and had itself replaced the Constantinian basilica founded by Constantius II to replace the first Byzantine cathedral, ] (Holy Peace). Justinian commissioned ] and ] to replace it with a new and incomparable ]. This was the great cathedral of the city, whose dome was said to be held aloft by God alone, and which was directly connected to the palace so that the imperial family could attend services without passing through the streets. "The architectural form of the building was meant to reflect Justinian programmatic harmony: the circular dome (a symbol of secular authority in classical Roman architecture) would be harmoniously combined with the rectangular form (typical for Christian and pre-Christian temples)."<ref>{{Cite web |last=Calian |first=Florin George |date=2021-03-25 |title=Opinion {{!}} The Hagia Sophia and Turkey's Neo-Ottomanism |url=https://armenianweekly.com/2021/03/24/the-hagia-sophia-and-turkeys-neo-ottomanism/ |access-date=2024-01-07 |website=The Armenian Weekly |language=en-US}}</ref> The dedication took place on 26 December 537 in the presence of the emperor, who was later reported to have exclaimed, "O ], I have outdone thee!"<ref>Source for quote: ''Scriptores originum Constantinopolitanarum'', ed T Preger I 105 (see ], ''History of the Byzantine Empire'', 1952, vol I, p. 188).</ref> Hagia Sophia was served by 600 people including 80 priests, and cost 20,000 pounds of gold to build.<ref name="cost">{{Cite book |last=Madden |first=Thomas F. |title=Crusades: The Illustrated History |date=2004 |publisher=University of Michigan Press |isbn=9780472114634 |page=114}}</ref> | |||

| === Survival, 565–717 === | |||

| In the early 7th century the ] and later the ] overwhelmed much of the ], threatening Constantinople from the west. Simultaneously, the ]n ]s overwhelmed the Prefecture of the East and penetrated deep into ]. ], son to the ] of ], set sail for the city and assumed the purple. He found the military situation so dire that he is said at first to have contemplated withdrawing the imperial capital to ], but relented after the people of Constantinople begged him to stay. Constantinople lost its right to free grain in 618, when Heraclius realized that the city no longer could be supplied from Egyptian sources due to the Persian wars. The population of Constantinople dropped substantially in size as a result, from 500,000 inhabitants to just 40,000-70,000.<ref>The Inheritance of Rome, Chris Wickham, Penguin Books Ltd. 2009, ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0 (page 260)</ref> | |||

| Justinian also had Anthemius and Isidore demolish and replace the original ] and Hagia Irene built by Constantine with new churches under the same dedication. The Justinianic Church of the Holy Apostles was designed in the form of an equal-armed cross with five domes, and ornamented with beautiful mosaics. This church was to remain the burial place of the emperors from Constantine himself until the 11th century. When the city fell to the Turks in 1453, the church was demolished to make room for the tomb of ] the Conqueror. Justinian was also concerned with other aspects of the city's built environment, legislating against the abuse of laws prohibiting building within {{cvt|100|ft|m}} of the sea front, in order to protect the view.<ref>Justinian, ''Novellae'' 63 and 165.</ref> | |||

| While the Great City withstood a ], ] campaigned deep into Persian territory and briefly restored the ''status quo'' in 628 as the Persians surrendered all their conquests. However, the empire was left weakened in the face of subsequent attacks from the ] when the African and south-east Mediterranean provinces were lost for good. During these wars, a ] of Constantinople by the Muslims lasted from 674 to 678, and a ] from 717 to 718. While the ] made the city impregnable from the land, a newly discovered incendiary substance known as "]" allowed the ] to destroy the Arab fleets and keep the city supplied. In the second siege, decisive help was rendered by the ]. The failure of this siege was a severe blow to the ], and stabilised the Byzantine-Arab equilibrium. | |||

| During Justinian I's reign, the city's population reached about 500,000 people.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150826083011/http://www.tulane.edu/~august/H303/handouts/Population.htm |date=August 26, 2015 }}, Kenneth W. Harl.</ref> However, the social fabric of Constantinople was also damaged by the onset of the ] between 541 and 542 AD, It killed perhaps 40% of the city's inhabitants.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171007210210/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4381924.stm |date=2017-10-07 }}, ], November 7, 2005.</ref> Lasting two months, the plague is noted to have caused widespread civil disruption, including the inability of the population to bury the dead and attend relatives funerals.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Malalas |first=John |title=The Chronicle of John Malalas |date=1 January 1986 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-34460-0 |location=Leiden |publication-date=1 January 1986 |pages=286-287 |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| === 717–1025 === | |||

| ] (886–912) adoring ]. ] above the Imperial Gate in the ].]] | |||

| ] is one of the |

]) that protected Constantinople during the ]]] | ||

| === Survival, 565–717: Constantinople during the Byzantine Dark Ages === | |||

| In the early 7th century, the ] and later the ] overwhelmed much of the ], threatening Constantinople with attack from the west. Simultaneously, the ]n ]s overwhelmed the Prefecture of the East and penetrated deep into ]. ], son of the ] of Africa, set sail for the city and assumed the throne. He found the military situation so dire that he is said to have contemplated withdrawing the imperial capital to Carthage, but relented after the people of Constantinople begged him to stay. The citizens lost their right to free grain in 618 when Heraclius realized that the city could no longer be supplied from Egypt as a result of the Persian wars: the population fell substantially as a result.<ref>Possibly from the largest city in the world with 500,000 inhabitants to just 40,000–70,000: The Inheritance of Rome, Chris Wickham, Penguin Books Ltd. 2009, {{ISBN|978-0-670-02098-0}} (p. 260)</ref> | |||

| ] medieval Byzantine Greek Orthodox church preserved as the Chora Museum in the Edirnekapı neighborhood of ]]] | |||

| While the city withstood a ] by the Sassanids and Avars in 626, Heraclius campaigned deep into Persian territory and briefly restored the ''status quo'' in 628, when the Persians surrendered all their conquests. However, further sieges followed the ], first from ] and then in ]. The ] kept the city impenetrable from the land, while a newly discovered incendiary substance known as ] allowed the ] to destroy the Arab fleets and keep the city supplied. In the second siege, the second ruler of ], ], rendered decisive help. He was called ''Saviour of Europe''.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Exposition, Dedicated to Khan Tervel |url=http://www.programata.bg/?p=62&c=1&id=51493&l=2 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160507131353/http://www.programata.bg/?p=62&c=1&id=51493&l=2 |archive-date=2016-05-07 |access-date=2014-08-28 |website=Programata}}</ref> | |||

| === 717–1025: Constantinople during the Macedonian Renaissance === | |||

| ] (886–912) adoring ]. ] above the Imperial Gate in the ].]] | |||

| In the 730s ] carried out extensive repairs of the Theodosian walls, which had been damaged by frequent and violent attacks; this work was financed by a special tax on all the subjects of the Empire.<ref>Vasiliev 1952, p. 251.</ref> | In the 730s ] carried out extensive repairs of the Theodosian walls, which had been damaged by frequent and violent attacks; this work was financed by a special tax on all the subjects of the Empire.<ref>Vasiliev 1952, p. 251.</ref> | ||

| Theodora, widow of the Emperor ] ( |

Theodora, widow of the Emperor ] (died 842), acted as regent during the minority of her son ], who was said to have been introduced to dissolute habits by her brother Bardas. When Michael assumed power in 856, he became known for excessive drunkenness, appeared in the hippodrome as a charioteer and burlesqued the religious processions of the clergy. He removed Theodora from the Great Palace to the Carian Palace and later to the ], but, after the death of Bardas, she was released to live in the palace of St Mamas; she also had a rural residence at the Anthemian Palace, where Michael was assassinated in 867.<ref>George Finlay, History of the Byzantine Empire, Dent, London, 1906, pp. 156–161.</ref> | ||

| In 860, an ] was made on the city by a new principality set up a few years earlier at ] by ], two ] chiefs: Two hundred small vessels passed through the Bosporus and plundered the monasteries and other properties on the suburban ]. ], the admiral of the Byzantine fleet, alerted the emperor Michael, who promptly put the invaders to flight; but the suddenness and savagery of the onslaught made a deep impression on the citizens.<ref>Finlay, 1906 pp. |

In 860, an ] was made on the city by a new principality set up a few years earlier at ] by ], two ] chiefs: Two hundred small vessels passed through the Bosporus and plundered the monasteries and other properties on the suburban ]. ], the admiral of the Byzantine fleet, alerted the emperor Michael, who promptly put the invaders to flight; but the suddenness and savagery of the onslaught made a deep impression on the citizens.<ref>Finlay, 1906, pp. 174–175.</ref> | ||

| In 980, the emperor ] received an unusual gift from Prince ] of Kiev: 6,000 ] warriors, which Basil formed into a new bodyguard known as the ]. They were known for their ferocity, honour, and loyalty. It is said that, in 1038, they were dispersed in winter quarters in the ] |

In 980, the emperor ] received an unusual gift from Prince ] of Kiev: 6,000 ] warriors, which Basil formed into a new bodyguard known as the ]. They were known for their ferocity, honour, and loyalty. It is said that, in 1038, they were dispersed in winter quarters in the ] when one of their number attempted to violate a countrywoman, but in the struggle she seized his sword and killed him; instead of taking revenge, however, his comrades applauded her conduct, compensated her with all his possessions, and exposed his body without burial as if he had committed suicide.<ref>Finlay, 1906, p. 379.</ref> However, following the death of an Emperor, they became known also for plunder in the Imperial palaces.<ref>Enoksen, Lars Magnar. (1998). ''Runor : historia, tydning, tolkning''. Historiska Media, Falun. {{ISBN|91-88930-32-7}} p. 135.</ref> Later in the 11th century the Varangian Guard became dominated by ] who preferred this way of life to subjugation by the ].<ref>J M Hussey, The Byzantine World, Hutchinson, London, 1967, p. 92.</ref> | ||

| ] in Constantinople – the image of Christ Pantocrator on the walls of the upper southern gallery, Christ being flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist; circa 1261<ref>{{Cite book |last=Freeman |first=Evan |url=https://pressbooks.pub/smarthistoryguidetobyzantineart/chapter/late-byzantine-naturalism-hagia-sophias-deesis-mosaic/ |title=Smarthistory Guide to Byzantine Art |date=2021 |chapter=Hagia Sophia's Deesis Mosaic}}</ref>]] | |||

| The '']'', which dates to the 10th century, gives a detailed picture of the city's commercial life and its organization at that time. The corporations in which the tradesmen of Constantinople were organised were supervised by the Eparch, who regulated such matters as production, prices, import, and export. Each guild had its own monopoly, and tradesmen might not belong to more than one. It is an impressive testament to the strength of tradition how little these arrangements had changed since the office, then known by the Latin version of its title, had been set up in 330 to mirror the urban prefecture of Rome.<ref>Vasiliev 1952, pp. 343-4.</ref> | |||

| The '']'', which dates to the 10th century, gives a detailed picture of the city's commercial life and its organization at that time. The corporations in which the tradesmen of Constantinople were organised were supervised by the Eparch, who regulated such matters as production, prices, import, and export. Each guild had its own monopoly, and tradesmen might not belong to more than one. It is an impressive testament to the strength of tradition how little these arrangements had changed since the office, then known by the Latin version of its title, had been set up in 330 to mirror the urban prefecture of Rome.<ref>Vasiliev 1952, pp. 343–344.</ref> | |||

| In the 9th and 10th centuries, Constantinople had a population of between 500,000 and 800,000.<ref>, Daniel C. Waugh.</ref> | |||

| In the 9th and 10th centuries, Constantinople had a population of between 500,000 and 800,000.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060917215153/http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/cities/turkey/istanbul/istanbul.html |date=2006-09-17 }}, Daniel C. Waugh.</ref> | |||

| ==== Iconoclast controversy ==== | |||

| ], Istanbul]] | |||

| In the 8th and 9th centuries, the ] movement caused serious political unrest throughout the Empire. The emperor ] issued a decree in 726 against images, and ordered the destruction of a statue of Christ over one of the doors of the Chalke, an act that was fiercely resisted by the citizens.<ref>The officer given the task was killed by the crowd, and in the end the image was removed rather than destroyed: It was to be restored by ] and removed again by ]: Finlay 1906, p. 111.</ref> ] convoked a ], which condemned the worship of images, after which many treasures were broken, burned, or painted over with depictions of trees, birds or animals: One source refers to the ] at ] as having been transformed into a "fruit store and aviary".<ref>Vasiliev 1952, p. 261.</ref> Following the death of his son ] in 780, the empress ] restored the veneration of images through the agency of the ] in 787. | |||

| ==== Iconoclast controversy in Constantinople ==== | |||

| The iconoclast controversy returned in the early 9th century, only to be resolved once more in 843 during the regency of Empress ], who restored the icons. These controversies contributed to the deterioration of relations between the ] and the ] Churches. | |||

| In the 8th and 9th centuries, the ] movement caused serious political unrest throughout the Empire. The emperor ] issued a decree in 726 against images, and ordered the destruction of a statue of Christ over one of the doors of the Chalke, an act that was fiercely resisted by the citizens.<ref>The officer given the task was killed by the crowd, and in the end the image was removed rather than destroyed: It was to be restored by ] and removed again by ]: Finlay 1906, p. 111.</ref> ] convoked a ], which condemned the worship of images, after which many treasures were broken, burned, or painted over with depictions of trees, birds or animals: One source refers to the ] at ] as having been transformed into a "fruit store and aviary".<ref>Vasiliev 1952, p. 261.</ref> Following the death of her husband ] in 780, the empress ] restored the veneration of images through the agency of the ] in 787. | |||

| The iconoclast controversy returned in the early 9th century, only to be resolved once more in 843 during the regency of Empress ], who restored the icons. These controversies contributed to the deterioration of relations between the ] and the ] Churches. | |||

| === Prelude to the Comnenian period, 1025–1081 === | |||

| === 1025–1081: Constantinople after Basil II === | |||

| In the late 11th century catastrophe struck with the unexpected and calamitous defeat of the imperial armies at the ] in Armenia in 1071. The Emperor ] Diogenes was captured. The peace terms demanded by ], sultan of the Seljuk Turks, were not excessive, and Romanus accepted them. On his release, however, Romanus found that enemies had placed their own candidate on the throne in his absence; he surrendered to them and suffered death by torture, and the new ruler, ] Ducas, refused to honour the treaty. In response, the Turks began to move into Anatolia in 1073. The collapse of the old defensive system meant that they met no opposition, and the empire's resources were distracted and squandered in a series of civil wars. Thousands of ] tribesmen crossed the unguarded frontier and moved into Anatolia. By 1080, a huge area had been lost to the Empire, and the Turks were within striking distance of Constantinople. | In the late 11th century catastrophe struck with the unexpected and calamitous defeat of the imperial armies at the ] in Armenia in 1071. The Emperor ] Diogenes was captured. The peace terms demanded by ], sultan of the Seljuk Turks, were not excessive, and Romanus accepted them. On his release, however, Romanus found that enemies had placed their own candidate on the throne in his absence; he surrendered to them and suffered death by torture, and the new ruler, ] Ducas, refused to honour the treaty. In response, the Turks began to move into Anatolia in 1073. The collapse of the old defensive system meant that they met no opposition, and the empire's resources were distracted and squandered in a series of civil wars. Thousands of ] tribesmen crossed the unguarded frontier and moved into Anatolia. By 1080, a huge area had been lost to the Empire, and the Turks were within striking distance of Constantinople. | ||

| === 1081–1185 === | === 1081–1185: Constantinople under the Komneni === | ||

| ] under ], |

] under ], {{circa|1180}}]] | ||

| ] from the upper gallery of the ], Constantinople. Emperor ] (1118–1143) is shown on the left, with the ] and infant ] in the centre, and John's consort ] on the right.]] | ] from the upper gallery of the ], Constantinople. Emperor ] (1118–1143) is shown on the left, with the ] and infant ] in the centre, and John's consort ] on the right.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Freeman |first=Evan |url=https://pressbooks.pub/smarthistoryguidetobyzantineart/chapter/middle-byzantine-mosaics-in-hagia-sophia/ |title=Smarthistory Guide to Byzantine Art |date=2021 |chapter=Middle Byzantine Mosaics in Hagia Sophia}}</ref>]] | ||

| ], also known as the Church of Theotokos Pammakaristos (Greek: Θεοτόκος ἡ Παμμακάριστος, "All-Blessed Mother of God"), is one of the most famous Greek Orthodox Byzantine churches in ].]] | |||

| Under the |

Under the Komnenian dynasty (1081–1185), Byzantium staged a remarkable recovery. In 1090–91, the nomadic ] reached the walls of Constantinople, where Emperor Alexius I with the aid of the ] annihilated their army.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Pechenegs |url=http://www.geocities.com/egfroth1/Pechenegs |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050829210704/http://www.geocities.com/egfroth1/Pechenegs |archive-date=2005-08-29 |access-date=2009-10-27}}, Steven Lowe and Dmitriy V. Ryaboy.</ref> In response to a call for aid from ], the ] assembled at Constantinople in 1096, but declining to put itself under Byzantine command set out for ] on its own account.<ref>There is a source for these events: the writer and historian ] in her work ].</ref> ] built the monastery of the Pantocrator (Almighty) with a hospital for the poor of 50 beds.<ref>Vasiliev 1952, p. 472.</ref> | ||

| With the restoration of firm central government, the empire became fabulously wealthy. The population was rising (estimates for Constantinople in the 12th century vary from |

With the restoration of firm central government, the empire became fabulously wealthy. The population was rising (estimates for Constantinople in the 12th century vary from some 100,000 to 500,000), and towns and cities across the realm flourished. Meanwhile, the volume of money in circulation dramatically increased. This was reflected in Constantinople by the construction of the Blachernae palace, the creation of brilliant new works of art, and general prosperity at this time: an increase in trade, made possible by the growth of the Italian city-states, may have helped the growth of the economy. It is certain that the ] and others were active traders in Constantinople, making a living out of shipping goods between the Crusader Kingdoms of ] and the West, while also trading extensively with Byzantium and ]. The Venetians had factories on the north side of the Golden Horn, and large numbers of westerners were present in the city throughout the 12th century. Toward the end of ]'s reign, the number of foreigners in the city reached about 60,000–80,000 people out of a total population of about 400,000 people.<ref name="popu">J. Phillips, ''The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople'', 144.</ref> In 1171, Constantinople also contained a small community of 2,500 Jews.<ref name="Jews">J. Phillips, ''The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople'', 155.</ref> In 1182, most Latin (Western European) inhabitants of Constantinople ].<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/cambridgeillustr00robe |title=The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 950–1250 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1986 |isbn=978-0-521-26645-1 |pages=–508 |access-date=2016-02-19 |url-access=registration}}</ref> | ||

| In artistic terms, the 12th century was a very productive period. There was a revival in the ] art, for example: Mosaics became more realistic and vivid, with an increased emphasis on depicting three-dimensional forms. There was an increased demand for art, with more people having access to the necessary wealth to commission and pay for such work. |

In artistic terms, the 12th century was a very productive period. There was a revival in the ] art, for example: Mosaics became more realistic and vivid, with an increased emphasis on depicting three-dimensional forms. There was an increased demand for art, with more people having access to the necessary wealth to commission and pay for such work. | ||

| === 1185–1261: Constantinople during the Imperial Exile === | |||

| : "With its love of luxury and passion for colour, the art of this age delighted in the production of masterpieces that spread the fame of Byzantium throughout the whole of the Christian world. Beautiful silks from the work-shops of Constantinople also portrayed in dazzling colour animals - lions, elephants, eagles, and griffins - confronting each other, or represented Emperors gorgeously arrayed on horseback or engaged in the chase." | |||

| ] mosaic of Saint Anthony, the desert Father]] | |||

| ]'', by ], 1840]] | |||

| : "From the tenth to the twelfth century Byzantium was the main source of inspiration for the West. By their style, arrangement, and iconography the mosaics of St. Mark's at Venice and of the cathedral at ] clearly reveal their Byzantine origin. Similarly those of the ], the ] at ], and the ], together with the vast decoration of the cathedral at Monreale, demonstrate the influence of Byzantium on the ] Court of ] in the twelfth century. Hispano-] art was unquestionably derived from the Byzantine. ] owes much to the East, from which it borrowed not only its decorative forms but the plan of some of its buildings, as is proved, for instance, by the domed churches of south-western France. Princes of ], ], abbots of ], merchants of ], and the kings of Sicily all looked to Byzantium for artists or works of art. Such was the influence of Byzantine art in the twelfth century, that Russia, Venice, southern Italy and Sicily all virtually became provincial centres dedicated to its production." | |||

| ], ], ], and the ]. The borders are very uncertain.]] | |||

| On 25 July 1197, Constantinople was struck by a ] which burned the Latin Quarter and the area around the Gate of the Droungarios ({{langx|tr|Odun Kapısı}}) on the Golden Horn.<ref name="stilbes">{{Cite book |last1=Stilbes |first1=Constantine |title=Constantinus Stilbes Poemata |last2=Johannes M. Diethart |last3=Wolfram Hörandner |publisher=Walter de Gruyter |year=2005 |isbn=978-3-598-71235-7 |pages=16 line 184}}</ref><ref>Diethart and Hörandner (2005). p. 24, line 387</ref> Nevertheless, the destruction wrought by the 1197 fire paled in comparison with that brought by the Crusaders. In the course of a plot between ], ] and the ], the ] was, despite papal excommunication, diverted in 1203 against Constantinople, ostensibly promoting the claims of ] brother-in-law of Philip, son of the deposed emperor ]. The reigning emperor ] had made no preparation. The Crusaders occupied ], broke the ] protecting the ], and entered the harbour, where on 27 July they breached the sea walls: Alexios III fled. But the new Alexios IV Angelos found the Treasury inadequate, and was unable to make good the rewards he had promised to his western allies. Tension between the citizens and the Latin soldiers increased. In January 1204, the '']'' ] provoked a riot, it is presumed, to intimidate Alexios IV, but whose only result was the destruction of the great statue of ], the work of ], which stood in the principal forum facing west. | |||

| In February 1204, the people rose again: Alexios IV was imprisoned and executed, and Murzuphlos took the purple as ]. He made some attempt to repair the walls and organise the citizenry, but there had been no opportunity to bring in troops from the provinces and the guards were demoralised by the revolution. An attack by the Crusaders on 6 April failed, but a second from the Golden Horn on 12 April succeeded, and the invaders poured in. Alexios V fled. The Senate met in ] and offered the crown to ], who had married into the ], but it was too late. He came out with the Patriarch to the ] before the Great Palace and addressed the ]. Then the two of them slipped away with many of the nobility and embarked for Asia. By the next day the Doge and the leading Franks were installed in the Great Palace, and the city was given over to pillage for three days. | |||

| === 1185–1261 === | |||

| ]rs into Constantinople'', by ], 1840.]] | |||

| ], ], ], and the ]. The borders are very uncertain]] | |||

| In the course of a plot between ], ] and the ], the ] was, despite papal excommunication, diverted in 1203 against Constantinople, ostensibly promoting the claims of Alexius son of the deposed emperor Isaac. The reigning emperor ] had made no preparation. The Crusaders occupied ], broke the chain protecting the ] and entered the harbour, where on 27 July they breached the sea walls: Alexius III fled. But the new ] found the Treasury inadequate, and was unable to make good the rewards he had promised to his western allies. Tension between the citizens and the Latin soldiers increased. In January 1204, the '']'' Alexius Murzuphlus provoked a riot, it is presumed, to intimidate Alexius IV, but whose only result was the destruction of the great statue of Athena, the work of ], which stood in the principal forum facing west. | |||

| ], historian of the Crusades, wrote that the sack of Constantinople is "unparalleled in history". | |||

| In February, the people rose again: Alexius IV was imprisoned and executed, and Murzuphlus took the purple as ]. He made some attempt to repair the walls and organise the citizenry, but there had been no opportunity to bring in troops from the provinces and the guards were demoralised by the revolution. An attack by the Crusaders on 6 April failed, but a second from the Golden Horn on 12 April succeeded, and the invaders poured in. Alexius V fled. The Senate met in St Sophia and offered the crown to Theodore Lascaris, who had married into the Angelid family, but it was too late. He came out with the Patriarch to the ] before the Great Palace and addressed the Varangian Guard. Then the two of them slipped away with many of the nobility and embarked for Asia. By the next day the Doge and the leading Franks were installed in the Great Palace, and the city was given over to pillage for three days. | |||

| {{blockquote|For nine centuries, the great city had been the capital of Christian civilization. It was filled with works of art that had survived from ancient Greece and with the masterpieces of its own exquisite craftsmen. The Venetians seized treasures and carried them off to adorn their town. But the Frenchmen and Flemings were filled with a lust for destruction. They rushed in a howling mob down the streets and through the houses, snatching up everything that glittered and destroying whatever they could not carry, pausing only to murder or to rape, or to break open the wine-cellars . Neither monasteries nor churches nor libraries were spared. In Hagia Sophia itself, drunken soldiers could be seen tearing down the silken hangings and pulling the great silver ] to pieces, while sacred books and icons were trampled under foot. While they drank merrily from the altar-vessels a prostitute set herself on the Patriarch's throne and began to sing a ribald French song. Nuns were ravished in their convents. Palaces and hovels alike were entered and wrecked. Wounded women and children lay dying in the streets. For three days the ghastly scenes continued, till the huge and beautiful city was a shambles. When order was restored, citizens were tortured to make them reveal the goods that they had contrived to hide.<ref>Steven Runciman, ''A History of the Crusades'', Cambridge 1966 , vol 3, p. 123.</ref>}} | |||

| The great historian of the Crusades, Sir Steven Runciman, wrote that the sack of Constantinople is “unparalleled in history”. | |||

| For the next half-century, Constantinople was the seat of the ]. Under the rulers of the Latin Empire, the city declined, both in population and the condition of its buildings. ] cites an estimated population for Constantinople of 400,000 inhabitants; after the destruction wrought by the Crusaders on the city, about one third were homeless, and numerous courtiers, nobility, and higher clergy, followed various leading personages into exile. "As a result Constantinople became seriously depopulated," Talbot concludes.<ref name="Talbot-1993">], {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201127131710/https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291680 |date=2020-11-27 }}, ''Dumbarton Oaks Papers'', '''47''' (1993), p. 246</ref> | |||

| {{quote|“For nine centuries,” he goes on, “the great city had been the capital of Christian civilisation. It was filled with works of art that had survived from ancient Greece and with the masterpieces of its own exquisite craftsmen. The Venetians, wherever they could, seized treasures and carried them off. But the Frenchmen and Flemings were filled with a lust for destruction: They rushed in a howling mob down the streets and through the houses, snatching up everything that glittered and destroying whatever they could not carry, pausing only to murder or to rape, or to break open the wine-cellars. Neither monasteries nor churches nor libraries were spared. In St Sophia itself, drunken soldiers could be seen tearing down the silken hangings and pulling the silver iconostasis to pieces, while sacred books and icons were trampled under foot. While they drank from the altar-vessels, a prostitute sang a ribald French song on the Patriarch’s throne. Nuns were ravished in their convents. Palaces and hovels alike were wrecked. Wounded women and children lay dying in the streets. For three days the ghastly scenes continued until the huge and beautiful city was a shambles. Even after order was restored, citizens were tortured to make them reveal treasures they had hidden.|<ref>Steven Runciman, ''History of the Crusades'', Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1965, vol 3, pp. 111-128.</ref>}} | |||

| ], Istanbul]] | |||

| The Latins took over at least 20 churches and 13 monasteries, most prominently the Hagia Sophia, which became the cathedral of the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople. It is to these that E.H. Swift attributed the construction of a series of flying buttresses to shore up the walls of the church, which had been weakened over the centuries by earthquake tremors.<ref>Talbot, "Restoration of Constantinople", p. 247</ref> However, this act of maintenance is an exception: for the most part, the Latin occupiers were too few to maintain all of the buildings, either secular and sacred, and many became targets for vandalism or dismantling. Bronze and lead were removed from the roofs of abandoned buildings and melted down and sold to provide money to the chronically under-funded Empire for defense and to support the court; Deno John Geanokoplos writes that "it may well be that a division is suggested here: Latin laymen stripped secular buildings, ecclesiastics, the churches."<ref>Geanakoplos, ''Emperor Michael Palaeologus and the West'' (Harvard University Press, 1959), p. 124 n. 26</ref> Buildings were not the only targets of officials looking to raise funds for the impoverished Latin Empire: the monumental sculptures which adorned the Hippodrome and fora of the city were pulled down and melted for coinage. "Among the masterpieces destroyed, writes Talbot, "were a Herakles attributed to the fourth-century B.C. sculptor ], and monumental figures of Hera, Paris, and Helen."<ref name="Talbot-248">Talbot, "Restoration of Constantinople", p. 248</ref> | |||

| For the next half-century, Constantinople was the seat of the ]. The Byzantine nobility were scattered. Many went to ], where Theodore Lascaris set up an imperial court, or to ], where Theodore Angelus did the same; others fled to ], where one of the Comneni had already with Georgian support established an independent seat of empire.<ref>Hussey 1967, p. 70.</ref> Nicaea and Epirus both vied for the imperial title, and tried to recover Constantinople. In 1261, Constantinople was ] from its last Latin ruler, ], by the forces of the ] ]. | |||

| ], painted 1499]] | |||