| Revision as of 19:08, 26 August 2006 view sourceRex Germanus (talk | contribs)11,278 edits This encyclopedia should include everything it can, to me censurship is a mortal sinn. Mind the 3RR. This is you're 3rd revert you will be blocked if you do it again.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:51, 17 January 2025 view source Rodw (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers775,252 editsm Disambiguating links to Scientific language (link changed to Languages of science) using DisamAssist. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|West Germanic language}} | |||

| {{Infobox Language | |||

| {{pp-semi|small=yes}} | |||

| |name=German | |||

| {{Distinguish|Germanic languages|High German languages|Standard German|}} | |||

| |nativename=Deutsch | |||

| {{Use British English|date=December 2022}} | |||

| |familycolor=Indo-European | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} | |||

| |pronunciation= | |||

| {{Infobox language | |||

| |states=], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and 35 other countries. | |||

| | name = German | |||

| |region=], ] | |||

| | nativename = {{lang|de|Deutsch}} | |||

| |speakers=Native speakers: 100 million<br>Second language: 22 million | |||

| | pronunciation = {{IPA|de|dɔʏtʃ||De-Deutsch.ogg}} | |||

| |rank=11 | |||

| | states = {{Flatlist| | |||

| |fam1=] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |fam2=] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |fam3=] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |fam4=] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |script=] (]) | |||

| * ] | |||

| |nation=], ], ], ], ], ], ]. | |||

| * ] | |||

| Regional or local official language in: ], ], ] (co-official language of ] until 1990). |iso1=de|iso2b=ger|iso2t=deu|iso3=deu|sil=GER|map=]<br><center><small>Major German-speaking communities</center></small>}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{redirect|Deutsch}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| '''German''' (''{{Audio|de-Deutsch.ogg|Deutsch}}'') is a ]. It is a member of the ] of the ] branch of the ] and one of the world's major languages. Around the world, German is spoken by approximately 110 million native speakers and another 18 million non-native speakers . | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | speakers = <!-- Do not edit this section before consulting the talk page! Round to the nearest 5M -->]: 95 million | |||

| | speakers_label = Speakers | |||

| | ref = <ref>Thomas Marten, Fritz Joachim Sauer (Hrsg.): Länderkunde Deutschland, Österreich und Schweiz (mit Liechtenstein) im Querschnitt. Inform-Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-9805843-1-3, S. 7.</ref> | |||

| | speakers2 = ]: 80–85 million (2014)<ref name=eurobarometer /> | |||

| | familycolor = Indo-European | |||

| | fam2 = ] | |||

| | fam3 = ] | |||

| | stand1 = ] (], ], ]) | |||

| | script = {{plainlist| | |||

| * Since Old High German: ] (]) | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Until the mid-20th century: ]<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.thetorah.com/article/moses-mendelssohns-beur-translating-the-torah-in-the-age-of-enlightenment |title=Moses Mendelssohn's Be'ur: Translating the Torah in the Age of Enlightenment – TheTorah.com |website=www.thetorah.com |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=29 January 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240129190136/https://www.thetorah.com/article/moses-mendelssohns-beur-translating-the-torah-in-the-age-of-enlightenment |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE3471465 |title=Sefer Netivot ha-shalom: ṿe-hu ḥibur kolel ḥamishat ḥumshe ha-torah ʻim tiḳun sofrim ṿe-targum ashkenazi u-veʾur. - 1783. Translated from the Hebrew into German by Moses Mendelssohn. Berlin : Gedruckt bey George Friedrich Starcke |website=digipres.cjh.org |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=10 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230810230148/https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE3471465 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE3777308 |title=''המאסף ha-Me'asef''. 6644-5571 [1783-1811] [Newspaper in German printed in Hebrew characters]. Königsberg, Prussia. |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=10 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230810231813/https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE3777308 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Dostrzegacz_Nadwislanski |title=YIVO | Dostrzegacz Nadwiślański - / Der Beobakhter an der Vayksel. 1823–1824. Warsaw. |website=yivoencyclopedia.org |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=28 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230828095519/https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Dostrzegacz_Nadwislanski |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://duepublico2.uni-due.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/duepublico_derivate_00005400/kleindiss.pdf |title=Birgit Klein. 1998. ''Levi von Bonn alias Löb Kraus und die Juden im Alten Reich. Auf den Spuren eines Verrats mit weitreichenden Folgen'', p. 200. |access-date=10 August 2023 |archive-date=10 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230810230150/https://duepublico2.uni-due.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/duepublico_derivate_00005400/kleindiss.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| | sign = ] | |||

| | nation = {{hlist| | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | minority = {{Collapsible list<!-- Do not add countries or dependencies without consulting the talk page and citing definite sources! --> | |||

| | titlestyle = font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left; | |||

| | title = ] | |||

| | ] ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Lista de línguas cooficiais em municípios brasileiros |url=http://ipol.org.br/lista-de-linguas-cooficiais-em-municipios-brasileiros/ |access-date=2023-10-28 |website=ipol.org.br |publisher=IPOL |archive-date=12 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211212052326/http://ipol.org.br/lista-de-linguas-cooficiais-em-municipios-brasileiros/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] (]) | |||

| | ] (]) | |||

| | ] (]) | |||

| | ] (select localities) | |||

| | ] (]) | |||

| | ] (]) | |||

| }} | |||

| | iso1 = de | |||

| | iso2b = ger | |||

| | iso2t = deu | |||

| | lc1 = deu | |||

| | ld1 = ] | |||

| | lc2 = gmh | |||

| | ld2 = ] | |||

| | lc3 = goh | |||

| | ld3 = ] | |||

| | lc4 = gct | |||

| | ld4 = ] | |||

| | lc5 = bar | |||

| | ld5 = ] | |||

| | lc6 = cim | |||

| | ld6 = ] | |||

| | lc7 = geh | |||

| | ld7 = ] | |||

| | lc8 = ksh | |||

| | ld8 = ] | |||

| | lc9 = nds | |||

| | ld9 = ]{{refn|group=note|The status of Low German as a German variety or separate language is subject to discussion.{{sfn|Goossens|1983|p=27}}}} | |||

| | lc10 = sli | |||

| | ld10 = ] | |||

| | lc11 = ltz | |||

| | ld11 = ]{{refn|group=note|The status of Luxembourgish as a German variety or separate language is subject to discussion.}} | |||

| | lc12 = vmf | |||

| | ld12 = ] | |||

| | lc13 = mhn | |||

| | ld13 = ] | |||

| | lc14 = pfl | |||

| | ld14 = ] | |||

| | lc15 = pdc | |||

| | ld15 = ] | |||

| | lc16 = pdt | |||

| | ld16 = ]{{refn|group=note|The status of Plautdietsch as a German variety or separate language is subject to discussion.{{sfn|Goossens|1983|p=27}}}} | |||

| | lc17 = swg | |||

| | ld17 = ] | |||

| | lc18 = gsw | |||

| | ld18 = ] | |||

| | lc19 = uln | |||

| | ld19 = ] | |||

| | lc20 = sxu | |||

| | ld20 = ] | |||

| | lc21 = wae | |||

| | ld21 = ] | |||

| | lc22 = wep | |||

| | ld22 = ] | |||

| | lc23 = hrx | |||

| | ld23 = ] | |||

| | lc24 = yec | |||

| | ld24 = ] | |||

| | lc25 = yid | |||

| | ld25 = ] | |||

| | lingua = {{blist | |||

| | 52-ACB–dl (]) | |||

| | 52-AC (Continental West Germanic) | |||

| | 52-ACB (Deutsch & Dutch) | |||

| | 52-ACB-d (]) | |||

| | 52-ACB-e & -f (] and ]) | |||

| | 52-ACB-h (] varieties, including 52-ACB-hc (]) & 52-ACB-he (])) | |||

| | 52-ACB-i (]) | |||

| | Totalling 285 varieties: 52-ACB-daa to 52-ACB-i | |||

| }} | |||

| | glotto = stan1295 | |||

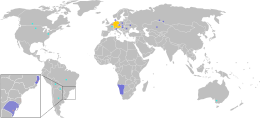

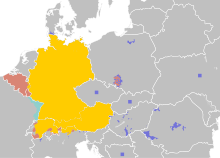

| | map = Idioma aleman (cropped).png | |||

| | mapscale = 1.2 | |||

| | mapcaption = {{legend|#0080FE|Majority of German speakers in Central Europe}} | |||

| {{legend|#88C4FE|Minority of German speakers in Central Europe}} | |||

| | map2 = Legal status of German in the world.svg | |||

| | notice = IPA | |||

| | mapcaption2 = {{legend|#ffcc00|Official language}} | |||

| {{legend|#d98575|Co-official language}} | |||

| {{legend|#7373d9|National language}} | |||

| {{legend|#30efe3|Minority language}} | |||

| | ancestor = ] | |||

| | ancestor2 = ] | |||

| | ancestor3 = ] | |||

| | fam4 = ] | |||

| | fam5 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

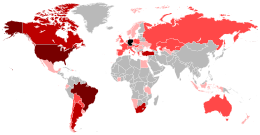

| ] by population: | |||

| {{Legend|#000000|Germany}} | |||

| {{Legend|#770000|≥10,000,000}} | |||

| {{Legend|#bc0000|≥1,000,000}} | |||

| {{Legend|#ff4848|≥100,000}} | |||

| {{Legend|#ffb0b0|≥10,000}}]] | |||

| ] | |||

| '''German''' ({{lang|de|Deutsch}}, {{IPA|de|dɔʏtʃ|pron|De-Deutsch.ogg}})<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.dwds.de/wb/Deutsch |title=Deutsch |website=Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache |date=31 October 2022 |language=de |access-date=March 27, 2024 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231124115017/https://www.dwds.de/wb/Deutsch |archive-date=November 24, 2023}}</ref> is a ] in the ], mainly spoken in ] and ]. It is the most spoken native language within the ]. It is the most widely spoken and ] (or co-official) language in ], ], ], ], and the Italian autonomous province of ]. It is also an official language of ], ] and the Italian autonomous region of ], as well as a recognized ] in ]. There are also notable German-speaking communities in ] (]), the ] (]), ] (]), ] (], ], and ]), ] (]), ] and ] (]). Overseas, sizeable communities of German-speakers are found in ] (] and ]), South Africa (]), ], among others, some communities have decidedly ] or ] characters (e.g. ], Peru). | |||

| Worldwide, German accounts for the most written ]s into and from a language (according to the '']''). | |||

| German is one of the major ]. German is the second-most widely spoken ], after English, both as a ] and as a ]. German is also widely taught as a ], especially in ] (where it is the third most taught foreign language after English and French), and in the United States. Overall, German is the fourth most commonly learned second language,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2015-04-15 |title=German is world's fourth most popular language |url=https://www.thelocal.de/20150415/german-is-fourth-most-learnt-language-globally |access-date=2024-09-03 |website=]}}</ref> and the third ] in K-12 education.<ref name=":0">{{cite web |date=February 2011 |title=Foreign Language Enrollments in K–12 Public Schools |url=http://www.actfl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/ReportSummary2011.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140817144116/http://www.actfl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/ReportSummary2011.pdf |archive-date=August 17, 2014 |access-date=October 17, 2015 |publisher=American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL)}}</ref> The language has been influential in the fields of philosophy, theology, science, and technology. It is the second most commonly used ]<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Abdumannonovna |first=Akhmedova Dilnoza |date=2022-02-13 |title=GERMAN AS THE LANGUAGE OF SCIENCE: PROBLEMS AND PERSPECTIVES |url=https://scholarexpress.net/index.php/wbss/article/view/522 |access-date=2024-09-02 |journal=World Bulletin of Social Sciences |volume=7 |pages=22–24}}</ref> and the ].<ref name=":1" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-09-03 |title=Usage statistics of content languages for websites |url=https://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language |access-date=2024-09-03 |website=w3techs.com}}</ref> The ] are ranked fifth in terms of annual publication of new books, with one-tenth of all books (including e-books) in the world being published in German.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lobachev |first1=Sergey |title=Top languages in global information production |journal=Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research |date=17 December 2008 |volume=3 |issue=2 |doi=10.21083/partnership.v3i2.826}}</ref> | |||

| ==Geographic distribution== | |||

| German is spoken primarily in ], ], ], ], in two-thirds of ], in the ] ] (in German, ''Südtirol''), in the small ] of ], and in some border villages of the ] (in German, ''Nordschleswig'', in Danish, ''Sønderjylland'') of ]. | |||

| German is most closely related to other West Germanic languages, namely ], ], ], the ], and ]. It also contains close similarities in vocabulary to some languages in the ], such as ], ], and ]. Modern German gradually developed from ], which in turn developed from ] during the ]. | |||

| In ] (in German, ''Luxemburg''), as well as in the French '']'' of ] (in German, ''Elsass'') and parts of ] (in German, ''Lothringen''), the native populations speak several German dialects, and some people also master standard German (especially in Luxembourg), although in Alsace and Lorraine ] has for the most part replaced the local German dialects in the last 40 years. | |||

| German is an ], with four ] for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative); three ] (masculine, feminine, neuter) and two ] (singular, plural). It has ]. The majority of its vocabulary derives from the ancient Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family, while a smaller share is partly derived from ] and ], along with fewer words borrowed from ] and ]. English, however, is the main source of more recent ]s. | |||

| Some German-speaking communities still survive in parts of ], the ], ], and above all ] and ], although the ethnic cleansings after World War II and massive emigration to Germany in the 1980s and 1990s have depopulated most of these communities. It is also spoken by German-speaking foreign populations and some of their descendants in ], ], ], ], ], ]. | |||

| German is a ]; the three standardized variants are ], ], and ]. ] is sometimes called '']'', which refers to its regional origin. German is also notable for ], with many varieties existing in Europe and other parts of the world. Some of these non-standard varieties have become recognized and protected by regional or national governments.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Chase |first=Jefferson |date=2016-09-25 |title=Preserving endangered German dialects |url=https://www.dw.com/en/linguists-seek-to-preserve-endangered-regional-german-dialects/a-35885772 |access-date=2024-09-02 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Outside of Europe and the former ], the largest German-speaking communities are to be found in the ], ] and in ] where millions of Germans migrated in the last 200 years; but the great majority of their descendants no longer speak German. Additionally, German-speaking communities are to be found in the former German colony of ], as well as in the other countries of German emigration such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ] (where ] developed), ], and ]. See also ]. | |||

| Since 2004, ] every year,<ref name="land.lu">{{Cite web |url=https://www.land.lu/page/article/379/9379/DEU/index.html |title=Beim Deutschen Bund in Eupen |first=Lëtzebuerger |last=Land |date=2 September 2016 |website=Lëtzebuerger Land |access-date=11 December 2023 |archive-date=21 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221221224824/https://www.land.lu/page/article/379/9379/DEU/index.html |url-status=live}}</ref> and the ] has been the main international body regulating ]. | |||

| In the USA, the largest concentrations of German speakers are in ] (], ] and some ] speak ] (a ] variety) and ]), ] (]), ] (] and ]), ], ], ], ] and ]. Early twentieth century immigration was often to ], ], ], and ]. Most of the post-] wave are in the ], ], and ] ]s, and in ]. In Brazil the largest concentrations of German speakers are in ] (where ] was developed), ], ], and ]. Generally, German immigrant communities in the USA have lost their mother tongue more quickly than those who moved to South America, possibly because for German speakers, English is easier to learn than Portuguese or Spanish. But mainly, it was due to fervent ] in the ] before and after the ], and the fear it caused in German-speakers of being attacked. | |||

| == Classification == | |||

| In ] there are people of German ancestry throughout the country and especially in the west as well as in ]. There is a large and vibrant community in the city of ]. | |||

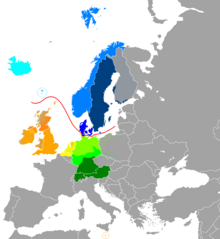

| [[File:Europe germanic-languages 2.PNG|thumb| | |||

| ''']''' | |||

| In ] there are also large populations of German ancestry, mainly in the cities of: ], ], ], ], and larger populations scattered in the states of ], ], and ]. ] is a large minority language spoken in the north by the ] communities, and is spoken by more than 200,000 people in ], while standard German is spoken by the affluent German communities in ] and ]. | |||

| {{legend|#FCA503|English}} | |||

| {{legend|#FD7B24|]}} | |||

| ''']'''<br/> Anglic and | |||

| {{legend|#E9D803|] (], ], ])}} | |||

| ''']''' Anglo-Frisian and | |||

| {{legend|#80FF00|]}} | |||

| ''']'''<br/> North Sea Germanic and | |||

| {{legend|#F0F702|]; in Africa: ]}} | |||

| ...... German (]): | |||

| {{legend|#00FF00|]; in ]: ]}} | |||

| {{legend|#008000|]}} | |||

| ...... ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| German is the main language of about 100 million people in Europe (as of ]), or 13.3% of all Europeans, being the second most spoken native language in Europe after ], above ] (66.5 million speakers in 2004) and ] (64.2 million speakers in 2004). German is the third most taught ] worldwide, also in the ] (after ] and ]); it is the second most known foreign language in the ] (after English; see ) It is one of the official ], and one of the three ]s of the European Commission, along with English and French. | |||

| ] in contemporary Europe]] | |||

| German is an ] that belongs to the ] group of the ]. The Germanic languages are traditionally subdivided into three branches: ], ], and ]. The first of these branches survives in modern ], ], ], ], and ], all of which are descended from ]. The East Germanic languages are now extinct, and ] is the only language in this branch which survives in written texts. The West Germanic languages, however, have undergone extensive dialectal subdivision and are now represented in modern languages such as English, German, ], ], ], and others.{{sfn|Robinson|1992|p=16}} | |||

| According to Global Reach (2004), 6.9% of the Internet population is German. According to Netz-tipp (2002), 7.7% of WebPages are written in German, making it second only to English. They also report that 12% of Google's users use its German interface. | |||

| Within the West Germanic language dialect continuum, the ] and ] lines (running through ]-] and ]-], respectively) serve to distinguish the Germanic dialects that were affected by the ] (south of Benrath) from those that were not (north of Uerdingen). The various regional dialects spoken south of these lines are grouped as ] dialects, while those spoken to the north comprise the ] and ] dialects. As members of the West Germanic language family, High German, Low German, and Low Franconian have been proposed to be further distinguished historically as ], ], and ], respectively. This classification indicates their historical descent from dialects spoken by the Irminones (also known as the Elbe group), Ingvaeones (or North Sea Germanic group), and Istvaeones (or Weser–Rhine group).{{sfn|Robinson|1992|p=16}} | |||

| Older statistics: Babel (1998) found somewhat similar demographics. FUNREDES (1998) and Vilaweb (2000) both found that German is the third most popular language used by websites, after English and Japanese. | |||

| ] is based on a combination of ]-] and Upper Franconian dialects, which are ] and Upper German dialects belonging to the ] dialect group. German is therefore closely related to the other languages based on High German dialects, such as ] (based on ]) and ]. Also closely related to Standard German are the ] dialects spoken in the southern ], such as ] (]) and the various Germanic dialects spoken in the French ] of ], such as ] (mainly Alemannic, but also Central{{ndash}}and{{nbsp}}] dialects) and ] (Central Franconian). | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{main|History of German}} | |||

| ] of ] 1520 work ''An den Christlichen Adel deutscher Nation'' ("To the Christian nobility of the German nation")]] | |||

| The history of the German language begins with the ] during the ], separating ] dialects from common ]. The earliest testimonies of ] are from scattered ] inscriptions, especially in ], from the ], the earliest glosses ('']'') date to the ] and the oldest coherent texts (the '']'', the '']'' and the ]) to the ]. ] at this time belongs to the ] cultural sphere, and ] should fall under German rather than ] influence during the ]. | |||

| After these High German dialects, standard German is less closely related to languages based on Low Franconian dialects (e.g., Dutch and Afrikaans), Low German or Low Saxon dialects (spoken in northern Germany and southern ]), neither of which underwent the High German consonant shift. As has been noted, the former of these dialect types is Istvaeonic and the latter Ingvaeonic, whereas the High German dialects are all Irminonic; the differences between these languages and standard German are therefore considerable. Also related to German are the Frisian languages—] (spoken in ]), ] (spoken in ]), and ] (spoken in ])—as well as the Anglic languages of English and Scots. These ] dialects did not take part in the High German consonant shift, and the Anglic languages also adopted much vocabulary from both ] and the ]. | |||

| As Germany was divided into many different ]s, the only force working for a unification or ] of German during a period of several hundred years was the general preference of writers trying to write in a way that could be understood in the largest possible area. | |||

| == History == | |||

| When ] translated the ] (the ] in 1522 and the ], published in parts and completed in 1534) he based his translation mainly on this already developed language, which was the most widely understood language at this time. This language was based on Eastern Upper and Eastern Central German dialects and preserved much of the grammatical system of Middle High German (unlike the spoken German dialects in Central and Upper Germany that already at that time began to lose the genitive case and the preterit tense). In the beginning, copies of the Bible had a long list for each region, which translated words unknown in the region into the regional dialect. ] rejected Luther's translation in the beginning and tried to create their own Catholic standard (''gemeines Deutsch'') — which, however, only differed from 'Protestant German' in some minor details. It took until the middle of the 18th century to create a standard that was widely accepted, thus ending the period of ]. | |||

| {{Main|History of German}} | |||

| === Old High German === | |||

| German used to be the language of commerce and government in the ], which encompassed a large area of Central and Eastern Europe. Until the mid-19th century it was essentially the language of townspeople throughout most of the Empire. It indicated that the speaker was a ], an urbanite, not their nationality. Some cities, such as ] (German: ''Prag'') and ] (], German: ''Ofen''), were gradually ] in the years after their incorporation into the Habsburg domain. Others, such as ] (German: ''Pressburg''), were originally settled during the Habsburg period and were primarily German at that time. A few cities such as ] (German: ''Mailand'') remained primarily non-German. However, most cities were primarily German during this time, such as Prague, ], Bratislava, ] (German: ''Agram''), and ] (German: ''Laibach''), though they were surrounded by territory that spoke other languages. | |||

| {{Main|Old High German}} | |||

| The ] begins with the ] during the ], which separated Old High German dialects from ]. This ] involved a drastic change in the pronunciation of both ] and voiceless ]s (''b'', ''d'', ''g'', and ''p'', ''t'', ''k'', respectively). The primary effects of the shift were the following below. | |||

| Until about 1800, standard German was almost only a written language. At this time, people in urban northern Germany, who spoke dialects very different from Standard German, learnt it almost like a foreign language and tried to pronounce it as close to the spelling as possible. Prescriptive pronunciation guides used to consider northern German pronunciation to be the standard. However, the actual pronunciation of standard German varies from region to region. | |||

| * Voiceless stops became long (]) voiceless ]s following a vowel; | |||

| * Voiceless stops became ]s in word-initial position, or following certain consonants; | |||

| * Voiced stops became voiceless in certain phonetic settings.{{sfn|Robinson|1992|pp=239–42}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| !Voiceless stop<br />following a vowel | |||

| !Word-initial<br />voiceless stop | |||

| !Voiced stop | |||

| |- | |||

| |/p/→/ff/ | |||

| |/p/→/pf/ | |||

| |/b/→/p/ | |||

| |- | |||

| |/t/→/ss/ | |||

| |/t/→/ts/ | |||

| |/d/→/t/ | |||

| |- | |||

| |/k/→/xx/ | |||

| |/k/→/kx/ | |||

| |/g/→/k/ | |||

| |} | |||

| [[File:Old norse, ca 900.PNG|thumb|The approximate extent of Germanic languages in the early 10th century: | |||

| Media and written works are almost all produced in standard German (often called ''Hochdeutsch'' in German) which is understood in all areas where German is spoken, except by pre-school children in areas which speak only dialect, for example ] and ]. However, in this age of television, even they now usually learn to understand Standard German before school age. | |||

| {{legend|#ff0000|''']'''}} | |||

| {{legend|#FF8040|''']'''}} | |||

| {{legend|#ff00ff|''']'''}} | |||

| {{legend|#ffff00|''']''' (])}} | |||

| {{legend|#00ff00|Continental West Germanic languages (], ], ], ]).}} | |||

| {{legend|#0000ff|''']''' (])}}]] | |||

| While there is written evidence of the ] language in several ] inscriptions from as early as the sixth century AD (such as the ]), the Old High German period is generally seen as beginning with the '']'' (written {{Circa|765–775}}), a Latin-German ] supplying over 3,000 Old High German words with their ] equivalents. After the ''Abrogans'', the first coherent works written in Old High German appear in the ninth century, chief among them being the '']'', ], and ''{{Lang|de|]}}'', and other religious texts (the '']'', '']'', ''Evangelienbuch'', and translated hymns and prayers).<ref>{{harvnb|Robinson|1992|pp=239–42}}, {{harvnb|Thomas|1992|pp=5–6}}</ref> The ''Muspilli'' is a Christian poem written in a ] dialect offering an account of the soul after the ], and the Merseburg charms are transcriptions of spells and charms from the ] Germanic tradition. Of particular interest to scholars, however, has been the ''{{Lang|de|Hildebrandslied}}'', a secular ] telling the tale of an estranged father and son unknowingly meeting each other in battle. Linguistically, this text is highly interesting due to the mixed use of ] and Old High German dialects in its composition. The written works of this period stem mainly from the ], Bavarian, and ] groups, all belonging to the Elbe Germanic group (]), which had settled in what is now southern-central Germany and ] between the second and sixth centuries, during the great migration.{{sfn|Robinson|1992|pp=239–42}} | |||

| The first dictionary of the ], the 16 parts of which were issued between 1852 and 1860, remains the most comprehensive guide to the words of the German language. In 1860, grammatical and orthographic rules first appeared in the '']''. In 1901, this was declared the standard definition of the German language. Official revisions of some of these rules were not issued until 1998, when the ] was officially promulgated by governmental representatives of all German-speaking countries. Since the reform, German spelling has been in an eight-year transitional period where the reformed spelling is taught in most schools, while traditional and reformed spellings co-exist in the media. See ] for an overview of the public debate concerning the reform with some major newspapers and magazines and several known writers refusing to adopt it. | |||

| In general, the surviving texts of Old High German (OHG) show a wide range of ]al diversity with very little written uniformity. The early written tradition of OHG survived mostly through ] and ] as local translations of Latin originals; as a result, the surviving texts are written in highly disparate regional dialects and exhibit significant Latin influence, particularly in vocabulary.{{sfn|Robinson|1992|pp=239–42}} At this point monasteries, where most written works were produced, were dominated by Latin, and German saw only occasional use in official and ecclesiastical writing. | |||

| After the spelling reform of 1996 led to so much public controversy and some of its changed rules introduced new ambiguities or were simply perceived as "ugly", the transitional period (initially scheduled to end on Dec. 31, 2005) was extended until at least the end of 2006, and some parts of the reform were changed again in March 2006. This new "reform of the reform" tries to remove the ambiguities introduced in 1996. To date (April 2006), it is yet to be accepted by all German-speaking countries. | |||

| ===Middle High German=== | |||

| ==Classification and related languages== | |||

| {{Main|Middle High German}} | |||

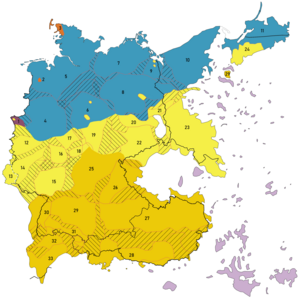

| ], the map of German ]s is divided into ] (green), ] (blue), and the ] (yellow). The main isoglosses, the Benrath, and Speyer lines are marked black.]] | |||

| German is a member of the ] of the ] family of languages, which in turn is part of the ]. | |||

| While there is no complete agreement over the dates of the ] (MHG) period, it is generally seen as lasting from 1050 to 1350.{{sfn|Waterman|1976|p=83}} This was a period of significant expansion of the geographical territory occupied by Germanic tribes, and consequently of the number of German speakers. Whereas during the Old High German period the Germanic tribes extended only as far east as the ] and ] rivers, the MHG period saw a number of these tribes expanding beyond this eastern boundary into ] territory (known as the ''{{Lang|de|]}}''). With the increasing wealth and geographic spread of the Germanic groups came greater use of German in the courts of nobles as the standard language of official proceedings and literature.{{sfn|Waterman|1976|p=83}} <!--The following citation needs to be checked, if this source can be used otherwise. Check me: <ref>{{Cite web|url=http://linguistics.byu.edu/classes/Ling450ch/reports/german.html|title=A Brief History of the German Language|last=Alder|first=Aaron D.|website=linguistics.byu.edu|access-date=13 July 2017}}</ref> --> A clear example of this is the ''{{Lang|de|mittelhochdeutsche Dichtersprache}}'' employed in the ] court in ] as a standardized supra-dialectal written language. While these efforts were still regionally bound, German began to be used in place of Latin for certain official purposes, leading to a greater need for regularity in written conventions. | |||

| ===Neighbouring languages=== | |||

| In these modern days Germany is surrounded by ]s, in the north by the ] and ]; in the east ], ], ], ], and ]; in the south ], ], ], ], and ]; in the west ] and ]. Except for Frisian and Dutch, none of these languages are West Germanic, and so they are clearly distinct from German. Frisian, after ], the closest related living language to English; and Dutch, the closest related living language to German (after ]) are not ] with German. Although a ] still exists at certain places along the Dutch-German language border this is rapidly fading away because of centuries of standardisation in both countries, today limited to only a few villages. | |||

| While the major changes of the MHG period were socio-cultural, High German was still undergoing significant linguistic changes in syntax, phonetics, and morphology as well (e.g. ] of certain vowel sounds: ''{{Lang|goh|hus}}'' (OHG & MHG "house")''→{{Lang|gmh|haus}} (regionally in later MHG)→{{Lang|de|Haus}}'' (NHG), and weakening of unstressed short vowels to ] : ''{{Lang|goh|taga}}'' (OHG "days")→''{{Lang|gmh|tage}}'' (MHG)).{{sfn|Salmons|2012|p=195}} | |||

| ===Official status=== | |||

| ]-flag, flag of the three dominant states in the German '']''.]] | |||

| Standard German is the only official language in ] and ]; it shares official status in ] (with ], ] and ] as minority languages), ] (with ], ] and ]), and ] (with ] and ]). It is used as a local official language in German-speaking regions of ], ], ], and ]. It is one of the 20 official ]. | |||

| A great wealth of texts survives from the MHG period. Significantly, these texts include a number of impressive secular works, such as the {{lang|de|]}}, an ] telling the story of the ]-slayer ] ({{circa|thirteenth century}}), and the '']'', an ] verse poem by ] ({{Circa|1203}}), ], and courtly romances such as '']'' and '']''. Also noteworthy is the ''{{Lang|de|]}}'', the first book of laws written in ] ({{Circa|1220}}). The abundance and especially the secular character of the literature of the MHG period demonstrate the beginnings of a standardized written form of German, as well as the desire of poets and authors to be understood by individuals on supra-dialectal terms. | |||

| It is also a minority language in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], the ] and the ], . | |||

| The Middle High German period is generally seen as ending when the 1346–53 ] decimated Europe's population.{{sfn|Scherer|Jankowsky|1995|p=11}} | |||

| German was once the ] of central, eastern and northern Europe and remains one of the most popular foreign languages taught worldwide, and is more popular than ] as a foreign language in ]. 32% of citizens of the EU-15 countries say they can converse in German. This is assisted by the availability of German TV by cable or satellite, where series like ] are shown ] into German. | |||

| ===Early New High German=== | |||

| ==Dialects== | |||

| {{Main|Early New High German}} | |||

| ''Main article ]'' | |||

| ]<ref>{{harvnb|Goossens|1977|p=48}}, {{harvnb|Wiesinger|1982|pp=807–900}}, {{harvnb|Heeringa|2004|pp=232–34}}, {{harvnb|Giesbers|2008|p=233}}, {{harvnb|König|Paul|2019|p=230}}</ref>]] | |||

| Modern High German begins with the Early New High German (ENHG) period, which ] dates 1350{{ndash}}1650, terminating with the end of the ].{{sfn|Scherer|Jankowsky|1995|p=11}} This period saw the further displacement of Latin by German as the primary language of courtly proceedings and, increasingly, of literature in the ]. While these states were still part of the ], and far from any form of unification, the desire for a cohesive written language that would be understandable across the many German-speaking ] and kingdoms was stronger than ever. As a spoken language German remained highly fractured throughout this period, with a vast number of often mutually incomprehensible ] being spoken throughout the German states; the invention of the ] {{circa|1440}} and the publication of ] in 1534, however, had an immense effect on standardizing German as a supra-dialectal written language. | |||

| ===German dialects vs. varieties of standard German=== | |||

| In German ], ''German ]s'' are distinguished from ''] of ]''. | |||

| The ENHG period saw the rise of several important cross-regional forms of ] German, one being ''{{Lang|de|gemeine tiutsch}}'', used in the court of the ] ], and the other being ''{{Lang|de|Meißner Deutsch}}'', used in the ] in the ].{{sfn|Keller|1978|pp=365–68}} | |||

| *The ''German dialects'' are the traditional local varieties. They are traditionally traced back to the different German tribes. Many of them are hardly understandable to someone who knows only standard German, since they often differ from standard German in ], ] and ]. If a narrow definition of ] based on ] is used, many ''German dialects'' are considered to be separate languages (for instance in the ]). However, such a point of view is unusual in German linguistics. | |||

| *The ''varieties of standard German'' refer to the different local varieties of the ] standard German. They only differ slightly in lexicon and phonology. In certain regions, they have replaced the traditional ''German dialects'', especially in Northern Germany. | |||

| Alongside these courtly written standards, the invention of the printing press led to the development of a number of printers' languages (''{{Lang|de|Druckersprachen}}'') aimed at making printed material readable and understandable across as many diverse dialects of German as possible.{{sfn|Bach|1965|p=254}} The greater ease of production and increased availability of written texts brought about increased standardisation in the written form of German. | |||

| ===Dialects in Germany=== | |||

| ] translation of the ] by the Protestant reformer ] (1534).<ref name="Lobenstein-Reichmann">{{cite book |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.382 |chapter=Martin Luther, Bible Translation, and the German Language |title=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion |date=2017 |last1=Lobenstein-Reichmann |first1=Anja |isbn=978-0-19-934037-8 }}</ref> The widespread popularity of the ] helped establish modern Standard German.<ref name="Lobenstein-Reichmann"/>]] | |||

| ] | |||

| One of the central events in the development of ENHG was the publication of ] (the ] was published in 1522; the ] was published in parts and completed in 1534).<ref name="Lobenstein-Reichmann"/> Luther based his translation primarily on the ''{{Lang|de|Meißner Deutsch}}'' of ], spending much time among the population of Saxony researching the dialect so as to make the work as natural and accessible to German speakers as possible. Copies of Luther's Bible featured a long list of ] for each region, translating words which were unknown in the region into the regional dialect. Luther said the following concerning his translation method:{{blockquote|One who would talk German does not ask the Latin how he shall do it; he must ask the mother in the home, the children on the streets, the common man in the market-place and note carefully how they talk, then translate accordingly. They will then understand what is said to them because it is German. When Christ says '{{Lang|la|ex abundantia cordis os loquitur|italic=no}},' I would translate, if I followed the papists, ''{{Lang|de|aus dem Überflusz des Herzens redet der Mund}}''. But tell me is this talking German? What German understands such stuff? No, the mother in the home and the plain man would say, ''{{Lang|de|Wesz das Herz voll ist, des gehet der Mund über}}''.{{sfn|Super|1893|p=81}}}} ] was also decisive for the German language and its evolution from ] to modern Standard German.<ref name="Lobenstein-Reichmann"/> The publication of Luther's Bible was a decisive moment in the ],<ref name="Lobenstein-Reichmann"/> and promoted the development of non-local forms of language and exposed all speakers to forms of German from outside their own area.<ref>Birgit Stolt, "Luther's Translation of the Bible." '']'' 28.4 (2014): 373–400.</ref> With Luther's rendering of the Bible in the vernacular, German asserted itself against the dominance of Latin as a legitimate language for courtly, literary, and now ecclesiastical subject-matter. His Bible was ubiquitous in the German states: nearly every household possessed a copy.{{sfn|Dickens|1974|p=134}} Nevertheless, even with the influence of Luther's Bible as an unofficial written standard, a widely accepted standard for written German did not appear until the middle of the eighteenth century.{{sfn|Scherer|1868|p=?}} | |||

| The variation among the German dialects is considerable, with only the neighbouring dialects being mutually intelligible. Some dialects are not intelligible to people who only know standard German. However, all German dialects belong to the ] of High German and Low Saxon languages. In the past (roughly until the end of the Second World War), there was a dialect continuum of all the continental ] because nearly any pair of neighbouring dialects were perfectly mutually intelligible. | |||

| ===Habsburg Empire=== | |||

| The dialect continuum of the continental West Germanic languages is typically divided into ] and ]. | |||

| ] in 1648: | |||

| {{legend|#DEB200|Territories under the ], comprising the ] heartland ('']'') of the ].}}]] | |||

| ] (1910), with German-speaking areas shown in red]] | |||

| German was the language of commerce and government in the ], which encompassed a large area of ] and ]. Until the mid-nineteenth century, it was essentially the language of townspeople throughout most of the Empire. Its use indicated that the speaker was a merchant or someone from an urban area, regardless of nationality. | |||

| ===Low Saxon=== | |||

| {{main|Low German}} | |||

| ] varieties (spoken on German territory) are considered dialects of the German language by some, but a separate language by others. Sometimes, Low Saxon and ] are grouped together to the ] because both are unaffected by the ]. | |||

| ] ({{langx|de|Prag|links=no}}) and ] (], {{langx|de|Ofen|links=no}}), to name two examples, were gradually ] in the years after their incorporation into the Habsburg domain; others, like ] ({{Lang|hi-latn|Pozsony}}, now Bratislava), were originally settled during the Habsburg period and were primarily German at that time. Prague, Budapest, Bratislava, and cities like ] ({{langx|de|Agram|links=no}}) or ] ({{langx|de|Laibach|links=no}}), contained significant German minorities. | |||

| ] was the ] of the ]. It was the predominant language in Northern Germany. This changed in the ]. In ], the ], by ] was printed. This translation is considered to be an important step towards the evolution of the ]. It aimed to be understandable to an ample audience and was based mainly on ] and ] varieties. The Early New High German language gained more prestige than Low Saxon and became the language of science and literature. Other factors were that around the same time, the Hanseatic league lost its importance as new trade routes to ] and the ] were established, and that the most powerful German states of that period were located in Middle and Southern Germany. | |||

| In the eastern provinces of ], ], and ] ({{langx|de|Banat, Buchenland, Siebenbürgen|links=no}}), German was the predominant language not only in the larger towns—like {{lang|de|Temeschburg}} (]), {{lang|de|Hermannstadt}} (]), and {{lang|de|Kronstadt}} (])—but also in many smaller localities in the surrounding areas.{{sfn|Rothaug|1910|p=}} | |||

| The 18th and 19th centuries were marked by mass ], the language of the schools being standard German. Slowly Low Saxon was pushed back and back until it was nothing but a language spoken by the uneducated and at home. Today, Low Saxon could be divided in two groups: Low Saxon varieties with a (''reasonable/large/huge'') standard German influx, and varieties of standard German with a Low Saxon influence (]). | |||

| === |

=== Standardization === | ||

| In 1901, the ] ended with a (nearly) complete ] of the ] language in its written form, and the Duden Handbook was declared its standard definition.{{sfn|Nerius|2000|pp=30–54}} Punctuation and compound spelling (joined or isolated compounds) were not standardized in the process. | |||

| '''High German''' is divided into ] and ]. Central German dialects include ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. It is spoken in the southeastern Netherlands, eastern Belgium, Luxembourg, parts of France, and in Germany approximately between the River ] and the southern edge of the Lowlands. Modern Standard German is mostly based on Central German, but it should be noted that the usual German term for modern Standard German is ''Hochdeutsch'', that is, ''High German''. | |||

| ] | |||

| The {{lang|de|Deutsche Bühnensprache}} ({{lit|German stage language}}) by ] had established ],{{sfn|Siebs|2000|p=20}} three years earlier; however, this was an artificial standard that did not correspond to any traditional spoken dialect. Rather, it was based on the pronunciation of German in Northern Germany, although it was subsequently regarded often as a general prescriptive norm, despite differing pronunciation traditions especially in the Upper-German-speaking regions that still characterise the dialect of the area today{{snd}}especially the pronunciation of the ending {{lang|de|-ig}} as instead of . In Northern Germany, High German was a foreign language to most inhabitants, whose native dialects were subsets of Low German. It was usually encountered only in writing or formal speech; in fact, most of High German was a written language, not identical to any spoken dialect, throughout the German-speaking area until well into the 19th century. However, wider ] was established on the basis of public speaking in theatres and the media during the 20th century and documented in pronouncing dictionaries. | |||

| Official revisions of some of the rules from 1901 were not issued until the controversial ] was made the official standard by governments of all German-speaking countries.{{sfn|Upward|1997|pp=22–24, 36}} Media and written works are now almost all produced in Standard German which is understood in all areas where German is spoken. | |||

| == Geographical distribution == | |||

| {{anchor|Geographic distribution}} | |||

| {{See also|List of countries and territories where German is an official language|German-speaking world}} | |||

| {{Pie chart | |||

| |caption = Approximate distribution of native German speakers (assuming a rounded total of 95 million) worldwide: | |||

| |value1=78.3 | |||

| |label1=Germany | |||

| |color1=#282828 | |||

| |value2=8.4 | |||

| |label2=Austria | |||

| |color2=Yellow | |||

| |value3=5.6 | |||

| |label3=Switzerland | |||

| |color3=#FF0000 | |||

| |value4=3.2 | |||

| |label4=Brazil | |||

| |color4=#008751 | |||

| |value5=0.4 | |||

| |label5=Italy (South Tyrol) | |||

| |color5=#85C1E9 | |||

| |value6=4.1 | |||

| |color6=Grey | |||

| |label6=Other | |||

| }} | |||

| As a result of the ], as well as the popularity of German taught as a ],<ref name="MLA-2015" /><ref name="eurostat-2016">{{cite web |url = http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Foreign_language_learning_statistics |title = Foreign language learning statistics – Statistics Explained |date = 17 March 2016 |website = ec.europa.eu |access-date = 18 July 2016 |archive-date = 28 June 2017 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170628100813/http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Foreign_language_learning_statistics |url-status = live }}</ref> the ] (or "Germanophones") spans all inhabited continents. | |||

| However, an exact, global number of native German speakers is complicated by the existence of several varieties whose status as separate "languages" or "dialects" is disputed for political and linguistic reasons, including quantitatively strong varieties like certain forms of ] and ].{{sfn|Goossens|1983|p=27}} With the inclusion or exclusion of certain varieties, it is estimated that approximately 90{{ndash}}95 million people speak German as a ],{{sfn|Lewis|Simons|Fennig|2015|p=}}{{page needed|date=October 2020}}{{sfn|Marten|Sauer|2005|p=7}} 10{{ndash}}25{{nbsp}}million speak it as a ],{{sfn|Lewis|Simons|Fennig|2015|p=}}{{page needed|date=October 2020}} and 75{{ndash}}100{{nbsp}}million as a ].<ref name="eurobarometer">{{cite web |url = http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf |title=Special Eurobarometer 386: Europeans and their languages |type=report |date=June 2012 |publisher= ] |access-date=24 July 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160106183351/http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf |archive-date=6 January 2016 }}</ref> This would imply the existence of approximately 175{{ndash}}220{{nbsp}}million German speakers worldwide.<ref name="Statista">{{cite web |url = http://www.statista.com/statistics/266808/the-most-spoken-languages-worldwide/ |title = The most spoken languages worldwide (speakers and native speaker in millions) |publisher = Statista, The Statistics Portal |location = New York City |quote = Native speakers=105, total speakers=185 |access-date = 11 July 2015 |archive-date = 28 June 2015 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150628162716/http://www.statista.com/statistics/266808/the-most-spoken-languages-worldwide/ |url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| German sociolinguist ] estimated a number of 289 million German foreign language speakers without clarifying the criteria by which he classified a speaker.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-02-20 |title=We speak German |url=https://www.deutschland.de/en/topic/culture/the-german-language-surprising-facts-and-figures |access-date=2023-09-20 |website=deutschland.de |language=en |archive-date=2 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201002203206/https://www.deutschland.de/en/topic/culture/the-german-language-surprising-facts-and-figures |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Europe === | |||

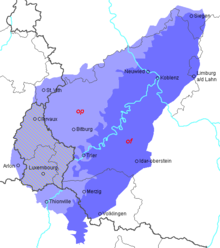

| [[File:Legal status of German in Europe.svg|thumb|right| | |||

| The German language in Europe: | |||

| <small>{{legend|#ffcc00|'''German '']''''': German is the official language (''de jure'' or ''de facto'') and first language of the majority of the population}} | |||

| {{legend|#d98575|German is a co-official language but not the first language of the majority of the population}} | |||

| {{legend|#7373d9|German (or a German dialect) is a legally recognized minority language (squares: geographic distribution too dispersed/small for map scale)}} | |||

| {{legend|#30efe3|German (or a variety of German) is spoken by a sizeable minority but has no legal recognition}}</small>]] | |||

| ] lies in the ] dialect area; only the very west of the country is}}{{legend|#FF4500|]-speaking.}}''Map shows Austria and ], Italy.'']] | |||

| ]) German is one of the four national languages of ].}}]] | |||

| ] lies in the ] dialect area.}}]] | |||

| ], German is spoken in the country's ], in the very east of the country.}}]] | |||

| {{as of|2012}}, about 90{{nbsp}}million people, or 16% of the ]'s population, spoke German as their mother tongue, making it the second most widely spoken language on the continent after Russian and the second biggest language in terms of overall speakers (after English), as well as the most spoken native language.<ref name=eurobarometer /> | |||

| ====German Sprachraum==== | |||

| The area in central Europe where the majority of the population speaks German as a first language and has German as a (co-)official language is called the "German '']''". German is the official language of the following countries: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] of ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| German is a co-official language of the following countries: | |||

| * ] (as majority language only in the ], which represents 0.7% of the Belgian population) | |||

| * ], along with French and Luxembourgish | |||

| * Switzerland, co-official at the federal level with French, Italian, and Romansh, and at the local level in four ]: ] (with French), ] (with French), ] (with Italian and Romansh) and ] (with French) | |||

| * Italy, (as majority language only in the ], which represents 0.6% of the Italian population) | |||

| ====Outside the German Sprachraum==== | |||

| Although ] and ] after the two ]s greatly diminished them, minority communities of mostly bilingual German native speakers exist in areas both adjacent to and detached from the Sprachraum. | |||

| Within Europe, German is a recognized minority language in the following countries:<ref name="charter-ratifications">{{cite web |author=Bureau des Traités |url=http://conventions.coe.int/treaty/Commun/ListeDeclarations.asp?NT=148&CM=1&DF=&CL=ENG&VL=1 |title=Recherches sur les traités |website=Conventions.coe.int |access-date=18 July 2016 |archive-date=18 September 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150918164438/http://www.conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/ListeDeclarations.asp?NT=148&CM=1&DF=&CL=ENG&VL=1 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| * ] (see also: ]) | |||

| * ] (see also: ]) | |||

| * ] (see also: ]) | |||

| * ] (see also ]; German is an ])<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ksng.gugik.gov.pl/english/files/list_of_minority_names.pdf |title=Map on page of Polish Commission on Standardization of Geographical Names |access-date=20 June 2015 |archive-date=1 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210501024600/http://ksng.gugik.gov.pl/english/files/list_of_minority_names.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| * ] (see also: ]) | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://russia.bestpravo.com/omsk/data04/tex17941.htm |script-title=ru:Устав азовского районного совета от 21 May 2002 N 5-09 устав муниципального |trans-title=Charter of the Azov District Council of 05.21.2002 N 5-09 Charter of the municipal |website=russia.bestpravo.com |language=ru |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160808205416/http://russia.bestpravo.com/omsk/data04/tex17941.htm |archive-date=8 August 2016 |access-date=18 July 2016}}</ref> (see also: ]) | |||

| * ] (see also: ]) | |||

| In France, the ] varieties of ] and ] are identified as "]s", but the ] of 1998 has not yet been ratified by the government.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/societe/2015/06/05/31003-20150605ARTFIG00157-charte-europeenne-des-langues-regionales-hollande-nourrit-la-guerre-contre-le-francais.php |title=Charte européenne des langues régionales : Hollande nourrit la guerre contre le français |trans-title=European Charter for Regional Languages: Hollande fuels the war against French |website=lefigaro.fr |date=5 June 2015 |access-date=18 July 2016 |archive-date=9 November 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161109035907/http://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/societe/2015/06/05/31003-20150605ARTFIG00157-charte-europeenne-des-langues-regionales-hollande-nourrit-la-guerre-contre-le-francais.php |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Africa=== | |||

| ====Namibia==== | |||

| {{Main|German language in Namibia}} | |||

| ], where German is a national language]] | |||

| Namibia also was a ] of the German Empire, from 1884 to 1915. About 30,000 people still speak German as a native tongue today, mostly ].<ref name="nmh-2007">{{Cite news |last=Fischer |first=Stefan |date=18 August 2007 |title=Deutsch in Namibia |url=http://www.az.com.na/fileadmin/pdf/2007/deutsch_in_namibia_2007_07_18.pdf |language=de |trans-title=German in Namibia |work=Allgemeine Deutsche Zeitung |publisher=] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080624233949/http://www.az.com.na/fileadmin/pdf/2007/deutsch_in_namibia_2007_07_18.pdf |archive-date=24 June 2008}}</ref> The period of German colonialism in Namibia also led to the evolution of a Standard German-based ] language called "]", which became a second language for parts of the indigenous population. Although it is nearly extinct today, some older Namibians still have some knowledge of it.{{sfn|Deumert|2003|pp=561–613}} | |||

| German remained a ''de facto'' official language of Namibia after the end of German colonial rule alongside English and ], and had ''de jure'' co-official status from 1984 until its independence from South Africa in 1990. However, the Namibian government perceived Afrikaans and German as symbols of ] and colonialism, and decided English would be the sole official language upon independence, stating that it was a "neutral" language as there were virtually no English native speakers in Namibia at that time.<ref name="nmh-2007" /> German, Afrikaans, and several indigenous languages thus became "national languages" by law, identifying them as elements of the cultural heritage of the nation and ensuring that the state acknowledged and supported their presence in the country. | |||

| Today, Namibia is considered to be the only German-speaking country outside of the ''Sprachraum'' in Europe.<ref name="nmh-2007" /> German is used in a wide variety of spheres throughout the country, especially in business, tourism, and public signage, as well as in education, churches (most notably the German-speaking ]), other cultural spheres such as music, and media (such as German language radio programs by the ]). The {{lang|de|]}} is one of the three biggest newspapers in Namibia and the only German-language daily in Africa.<ref name="nmh-2007" /> | |||

| The Moselle Franconian varieties spoken in ] have been officially standardized and institutionalized and are therefore usually considered a separate language known as ]. | |||

| ====Rest of Africa==== | |||

| Upper German dialects include ] (for instance ]), ], ], ] and ]. They are spoken in parts of the ], southern Germany, Liechtenstein, Austria, and in the German-speaking parts of Switzerland and Italy. | |||

| An estimated 12,000 people speak German or a German variety as a first language in South Africa, mostly originating from different waves of immigration during the 19th and 20th centuries.<ref name="L1eur">]</ref> One of the largest communities consists of the speakers of "Nataler Deutsch",<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.safrika.org/natal_en.html |title=Natal Germans |last=Schubert |first=Joachim |website=German South African Resource Page |access-date=2 August 2016 |archive-date=29 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200129161855/http://www.safrika.org/natal_en.html |url-status=live }}</ref> a variety of ] concentrated in and around ]. The South African constitution identifies German as a "commonly used" language and the ] is obligated to promote and ensure respect for it.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/chapter-1-founding-provisions#5 |title=Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 – Chapter 1: Founding Provisions |website=South African Government |access-date=18 July 2016 |archive-date=28 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141028043044/http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/chapter-1-founding-provisions#5 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] was also a ] of the ] from the same period (1884 to 1916). However, German was replaced by French and English, the languages of the two successor colonial powers, after its loss in ]. Nevertheless, since the 21st century, German has become a popular foreign language among pupils and students, with 300,000 people learning or speaking German in Cameroon in 2010 and over 230,000 in 2020.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230610081413/https://www.goethe.de/resources/files/pdf204/bro_deutsch-als-fremdsprache-weltweit.-datenerhebung-2020.pdf |date=10 June 2023 }}.</ref> Today Cameroon is one of the African countries outside Namibia with the highest number of people learning German.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Bathe |first=Dirk |date=2010-11-29 |title=Deutsch für die Zukunft |trans-title=When German means future |url=https://www.dw.com/de/wenn-deutsch-gleich-zukunft-heißt/a-5070255 |website=DW |language=de-DE |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230719161346/https://www.dw.com/de/wenn-deutsch-gleich-zukunft-hei%C3%9Ft/a-5070255 |archive-date= Jul 19, 2023 }}</ref> | |||

| ], ] and ] are High German dialects of Poland and ] respectively. | |||

| The High German varieties spoken by ]s (mostly in the former ]) have several unique features, and are usually considered as a separate language, ]. It is the only Germanic language that does not use the ] as its ]. | |||

| ===North America=== | |||

| The dialects of German which are or were primarily spoken in colonies or communities founded by German speaking people resemble the dialects of the regions the founders came from. For example, ] resembles dialects of the ], and ] resembles dialects of ], while ] '']'' is a ] variant. | |||

| {{Main|German language in the United States|Pennsylvania Dutch language|Plautdietsch|Hutterite German}} | |||

| In the United States, German is the fifth most spoken language in terms of native and second language speakers after English, ], ], and ] (with figures for ] and ] combined), with over 1 million total speakers.<ref name="US Census">{{cite web |title=Detailed List of Languages Spoken at Home for the Population 5 Years and Over by State: 2000 |url=https://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/phc-t20/tab05.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100117052130/https://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/phc-t20/tab05.pdf |archive-date=17 January 2010 |archive-format=pdf |access-date=15 March 2010 |publisher=]}}</ref> In the states of ] and ], German is the most common language spoken at home after English.<ref name=Blatt>{{Cite web |title=Tagalog in California, Cherokee in Arkansas: What language does your state speak? |url=http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2014/05/language_map_what_s_the_most_popular_language_in_your_state.html |website=Slate | author = Blatt, Ben |date=13 May 2014 |access-date=2014-05-13 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140513115444/http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2014/05/language_map_what_s_the_most_popular_language_in_your_state.html |archive-date=2014-05-13 }}</ref> As a legacy of significant ], German geographical names can be found throughout the ], such as ] and ] (North Dakota's state capital), plus many other regions.<ref>{{cite web |work=Germans from Russia Heritage Collection |title=Strasburg Centennial Book: 1902 - 2002 |url=https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/order/nd_sd/strasburg.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100619230113/https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/order/nd_sd/strasburg.html |archive-date=19 June 2010 |access-date=18 July 2016 |publisher=NDSU Libraries }}</ref> | |||

| A number of German varieties have developed in the country and are still spoken today, such as ] and ]. | |||

| In Brazil the largest concentrations of German speakers (]) are in ], where ] was developed, especially in the areas of ], ], and ]. | |||

| ===South America=== | |||

| In the ], the teaching of the German language to latter-age students has given rise to a pidgin variant which combines the German language with the grammar and spelling rules of the English language. It is often understandable by either party. The speakers of this language often refer to it as ''Amerikanisch'' or ''Amerikanischdeutsch'', although it is known in English as ]. However, this is a ], not a ]. | |||

| {{Main|Brazilian German|Colonia Tovar dialect}} | |||

| In the USA, in the ] in the state of Iowa ] is spoken. | |||

| In Brazil, the largest concentrations of German speakers are in the states of ] (where ] developed), ], and ].<ref name="ipol">{{cite web |title=IPOL realizará formação de recenseadores para o censo linguístico do município de Antônio Carlos-SC |trans-title=IPOL will carry out training of enumerators for the linguistic census of the municipality of Antônio Carlos-SC |url=http://e-ipol.org/ipol-realizara-formacao-de-recenseadores-para-o-censo-linguistico-do-municipio-de-antonio-carlos-sc/ |date=2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150626140033/http://e-ipol.org/ipol-realizara-formacao-de-recenseadores-para-o-censo-linguistico-do-municipio-de-antonio-carlos-sc/ |archive-date=26 June 2015 |access-date=18 July 2016 |website=IPOL }}</ref> | |||

| German dialects (namely ] and ]) are recognized languages in the following municipalities in Brazil: | |||

| * ] (statewide cultural language): ], ], ], ], ]<ref>{{cite web |last=Szczocarz |first=Roma |year=2017 |title=Pommern in Brasilien |trans-title=Pomerania in Brazil |url=https://lerncafe.de/lerncafe68/pommern-in-brasilien/ |access-date=27 July 2017 |website=LernCafe |publisher=ViLE-Netzwerk |archive-date=1 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201201172411/https://lerncafe.de/lerncafe68/pommern-in-brasilien/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * ] (] is a designated cultural language in the state): ], ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.al.rs.gov.br/legis/M010/M0100099.ASP?Hid_Tipo=TEXTO&Hid_TodasNormas=58094&hTexto=&Hid_IDNorma=58094 |website=al.rs.gov.br |title=Lei N.º 14.061, de 23 de julho de 2012 |access-date=30 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190330024221/http://www.al.rs.gov.br/legis/M010/M0100099.ASP?Hid_Tipo=TEXTO&Hid_TodasNormas=58094&hTexto=&Hid_IDNorma=58094 |archive-date=30 March 2019 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| * ]: ], ] (standard German recognized)<ref name=ipol /> | |||

| In Chile, during the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a ] of Germans, Swiss and Austrians. Because of that, two dialects of German emerged, ] and Chiloten-Deutsch.<ref>{{cite web |access-date=2021-12-17 |language=es-ES |title=El alemañol del sur de Chile {{!}} 10.09.2016 |first1=Natalia |last1=Messer |url=https://www.dw.com/es/el-alema%C3%B1ol-del-sur-de-chile/a-19541116 |website=DW |archive-date=29 April 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240429040903/https://www.dw.com/es/el-alema%C3%B1ol-del-sur-de-chile/a-19541116 |url-status=live }}<!-- auto-translated from Spanish by Module:CS1 translator --></ref> Immigrants even founded prosperous cities and towns. The impact of nineteenth century German immigration to southern Chile was such that ] was for a while a Spanish-German bilingual city with "German signboards and placards alongside the Spanish".<ref>{{Citation | |||

| | last1 = Skottsberg | |||

| | first1 = Carl | |||

| | author-link = Carl Skottsberg | |||

| | name-list-style = amp | |||

| | title = The Wilds of Patagonia: A Narrative of the Swedish Expedition to Patagonia Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland Island in 1907– 1909 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | location = London, England | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | edition = | |||

| | year = 1911 | |||

| }}</ref> Currently, German and its dialects are spoken in many cities, towns and rural areas of southern Chile, such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], among many others. | |||

| Small concentrations of German-speakers and their descendants are also found in ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="L1eur" /> | |||

| ===Oceania=== | |||

| In Australia, the state of ] experienced a pronounced wave of Prussian immigration in the 1840s (particularly from ] region). With the prolonged isolation from other German speakers and contact with ], a unique dialect known as ] developed, spoken predominantly in the ] near ]. Usage of German sharply declined with the advent of ], due to the prevailing anti-German sentiment in the population and related government action. It continued to be used as a first language into the 20th century, but its use is now limited to a few older speakers.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-26/keeping-south-australias-barossa-deutsch-alive/8375988 |title=Keeping SA's Barossa Deutsch alive over kaffee und kuchen |date=26 March 2017 |work=ABC News |access-date=23 February 2020 |language=en-AU |archive-date=9 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201109040531/https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-26/keeping-south-australias-barossa-deutsch-alive/8375988 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| As of the 2013 census, 36,642 people in ] spoke German, mostly descendants of a small wave of 19th century German immigrants, making it the third most spoken European language after English and French and overall the ninth most spoken language.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ethniccommunities.govt.nz/resources-2/our-languages-o-tatou-reo/new-registry-page/|title=Top 25 Languages in New Zealand|website=ethniccommunities.govt.nz|access-date=21 September 2022|archive-date=21 September 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220921024207/https://www.ethniccommunities.govt.nz/resources-2/our-languages-o-tatou-reo/new-registry-page/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| A German ] named {{lang|de|]}} was historically spoken in the former German colony of ], modern day ]. It is at a high risk of extinction, with only about 100 speakers remaining, and a topic of interest among linguists seeking to revive interest in the language.{{sfn|Holm|1989|p=616}} | |||

| ===As a foreign language=== | |||

| ] in the EU member states (+] and ]), in per cent of the adult population (+15), 2005]] | |||

| Like English, French, and Spanish, German has become a standard foreign language throughout the world, especially in the Western World.<ref name="eurobarometer" /><ref name="goethe-institut">{{cite web|url=https://www.goethe.de/resources/files/pdf37/Bro_Deutschlernerhebung_final3.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150623213857/https://www.goethe.de/resources/files/pdf37/Bro_Deutschlernerhebung_final3.pdf |archive-date=2015-06-23 |url-status=live|title= Deutsch als Fremdsprache weltweit. Datenerhebung 2015 – Worldwide survey of people learning German; conducted by the German Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the Goethe Institute|website=Goethe.de|access-date=18 July 2016}}</ref> German ranks second on par with French among the best known foreign languages in the ] (EU) after English,<ref name="eurobarometer"/> as well as in ],<ref name="Levada2008">{{cite web |script-title=ru:Знание иностранных языков в России |trans-title=Knowledge of foreign languages in Russia |language=ru |url=http://www.levada.ru/16-09-2008/znanie-inostrannykh-yazykov-v-rossii |publisher=Levada Centre |access-date=10 May 2015 |date=16 September 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150510133101/http://www.levada.ru/16-09-2008/znanie-inostrannykh-yazykov-v-rossii |archive-date=10 May 2015}}</ref> and ].<ref name="eurobarometer" /> In terms of student numbers across all levels of education, German ranks third in the EU (after English and French)<ref name="eurostat-2016" /> and in the United States (after Spanish and French).<ref name="MLA-2015"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.actfl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/ReportSummary2011.pdf |title=Foreign Language Enrollments in K–12 Public Schools |date=February 2011 |publisher=American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) |access-date=17 October 2015 |archive-date=8 April 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160408184754/http://www.actfl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/ReportSummary2011.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> In British schools, where learning a foreign language is not mandatory, a dramatic decline in entries for German A-Level has been observed.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Fox |first=Aine |date=2023-06-01 |title=Exam entries: German continues decline in popularity but computing soars |url=https://www.standard.co.uk/tech/gcse-alevel-spanish-german-alevels-b1085006.html |access-date=2023-08-26 |website=Evening Standard |language=en |archive-date=26 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230826091215/https://www.standard.co.uk/tech/gcse-alevel-spanish-german-alevels-b1085006.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2020, approximately 15.4{{nbsp}}million people were enrolled in learning German across all levels of education worldwide. This number has decreased from a peak of 20.1{{nbsp}}million in 2000.<ref name="DW survey">{{Cite web |last=Hamann |first=Greta |title=15.4 million people are learning German as a foreign language |date=2020-06-04 |url=https://www.dw.com/en/154-million-people-are-learning-german-as-a-foreign-language/a-53685365 |website=DW |language=en-GB |access-date=31 January 2021 |archive-date=7 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210207051223/https://www.dw.com/en/154-million-people-are-learning-german-as-a-foreign-language/a-53685365 |url-status=live }}</ref> Within the EU, not counting countries where it is an official language, German as a foreign language is most popular in ] and ], namely the ], ], ], the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name=eurobarometer /><ref name=eurostat /> German was once, and to some extent still is, a ] in those parts of Europe.{{sfn|Von Polenz|1999|pp=192–94, 96}} | |||

| ===German-language media worldwide=== | |||

| A visible sign of the geographical extension of the German language is the German-language media outside the German-speaking countries. | |||

| German is the second most commonly used scientific language<ref name="goethe1">{{cite web |title=Why Learn German? |url=https://www.goethe.de/en/spr/wdl.html |publisher=Goethe Institute |access-date=28 September 2014 }}</ref>{{Better source needed|date=January 2024}} as well as the third most widely used language on websites after English and Russian.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language/all |title=Usage of content languages for websites|access-date=18 February 2019|publisher= W3Techs: Web Technology Surveys}}</ref> | |||

| ] (German pronunciation: ; "''German Wave''" in German), or '''DW''', is Germany's public international broadcaster. The service is available in 30 languages. DW's satellite television service consists of channels in German, English, Spanish, and Arabic. | |||

| See also: | |||

| * ] and ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] and ] | |||

| * ] and ] | |||

| * ] (a non-profit German cultural association operational worldwide with 159 institutes, promoting the study of the German language abroad and encouraging international cultural exchange and relations.) | |||

| ==Standard German== | ==Standard German== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Standard German}} | ||

| ] | |||

| In German linguistics, only the traditional regional varieties are called dialects, not the different varieties of standard German. | |||

| The basis of Standard German developed with the ] and the chancery language spoken by the ], part of the regional High German group.{{sfn|Swadesh|1971|p=53}} However, there are places where the traditional regional dialects have been replaced by new vernaculars based on Standard German; that is the case in large stretches of ] but also in major cities in other parts of the country. It is important to note, however, that the colloquial Standard German differs from the formal written language, especially in grammar and syntax, in which it has been influenced by dialectal speech. | |||

| Standard German differs regionally among German-speaking countries in ] and some instances of ] and even ] and ]. This variation must not be confused with the variation of local ]. Even though the national varieties of Standard German are only somewhat influenced by the local dialects, they are very distinct. German is thus considered a ], with currently three national standard varieties of German: ], ] and ]. In comparison to other European languages (e.g. Portuguese, English), the multi-standard character of German is still not widely acknowledged.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dollinger |first=Stefan |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360951765 |chapter=Who is afraid of pluricentric perspectives? |title=Pluricentric languages and language education: Pedagogical Implications and Innovative Approaches to Language Teaching |publisher=Routledge |year=2023 |editor1-last=Callies|editor2-last=Hehner |editor1-first=Marcus|editor2-first= Stefanie |pages=219–220 |language=EN}}</ref> However, 90% of Austrian secondary school teachers of German consider German as having "more than one" standard variety.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=De Cillia|last2=Ransmayr |first1=Rudolf|first2= Jutta |title=Österreichisches Deutsch macht Schule |publisher=Böhlau |year=2019 |location=Vienna |pages=Abbildung 36 |language=DE}}</ref> In this context, some scholars speak of a ] that has been maintained as a core assumption of German dialectology.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dollinger |first=Stefan |title=The Pluricentricity Debate |publisher=Routledge |year=2019 |location=New York |page=14 |language=EN}}</ref> | |||

| Standard German differs regionally, especially between German-speaking countries, especially in ], but also in some instances of ] and even ]. This variation must not be confused with the variation of local dialects. Even though the regional varieties of standard German are to a certain degree influenced by the local dialects, they are very distinct. German is thus considered a ]. | |||

| In most regions, the speakers use a continuum |

In most regions, the speakers use a continuum, e.g. "Umgangssprache" (colloquial standards) from more dialectal varieties to more standard varieties depending on the circumstances. | ||

| ===Varieties=== | |||

| In the German-speaking parts of ], mixtures of dialect and standard are very seldom used, and the use of standard German is largely restricted to the written language. Therefore, this situation has been called a ''medial ]''. Standard German is rarely spoken, for instance when speaking with people who do not understand the ] dialects at all, and it is expected to be used in school. | |||

| ] | |||

| In German ], German ]s are distinguished from ] of ]. | |||

| ==Grammar== | |||