| Revision as of 18:14, 26 February 2018 edit208.67.7.9 (talk) →Personal life: Added another piece of infoTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:13, 19 January 2025 edit undoJet Pilot (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers3,352 editsm Reverted edits by 2601:741:102:7F40:85A8:3AC3:D676:591 (talk) to last version by RangersRus: nonconstructive editsTags: Rollback SWViewer [1.6] | ||

| (716 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|African-American woman (1920–1951), source of HeLa immortal cell line}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Lacks|other uses|Lack (disambiguation){{!}}Lack}} | |||

| {{pp-pc1}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=December 2022}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=October 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

| | name = Henrietta Lacks | | name = Henrietta Lacks | ||

| | image = Henrietta |

| image = Henrietta Lacks (1920-1951).jpg | ||

| | alt = A black-and-white photo of Lacks smiling | | alt = A black-and-white photo of Lacks smiling | ||

| | caption = Lacks {{circa|1945–1951}}.{{efn-ua|This photo is one of the few known photos of Lacks. It was printed in medical literature, its origin is unknown.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=1}}}} | |||

| | image_upright = 0.5 | |||

| | |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1920|8|1}} | ||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|mf=yes|1920|8|1}} | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1951|10|4|1920|8|1}} | |||

| | birth_place = ] | |||

| | death_place = ], Maryland, U.S. | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|mf=yes|1951|10|4|1920|8|1}} | |||

| | |

| death_cause = ] | ||

| | monuments = Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School; ] at ] | | monuments = ]; ] at ] | ||

| | birth_name = Loretta Pleasant | | birth_name = Loretta Pleasant | ||

| | height = {{approx.|{{cvt|5|ft|cm}}}}{{sfn|Skloot|2010|page=2}} | |||

| | height = around 5 ft tall<ref>{{citation|last=Skloot|first=Rebecca|authorlink= Rebecca Skloot|title=The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks|year=2010|publisher=]|place=New York City|page=2|isbn=978-1-4000-5217-2|ref=harv}}</ref> | |||

| | occupation = ] | | occupation = {{hlist|]|]<ref name="vpbio" />{{sfn|Skloot|2010|page=16}}}} | ||

| | spouse |

| spouse = {{marriage|David Lacks|1941}} | ||

| | children = 5 | |||

| | parents = Eliza (1886–1924) and John Randall Pleasant I (1881–1969) | |||

| | children = Lawrence Lacks<br />Elsie Lacks (1939–1955)<br />David "Sonny" Lacks, Jr.<br />Deborah Lacks Pullum (1949–2009)<br />Zakariyya Bari Abdul Rahman (born Joseph Lacks) | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Henrietta Lacks''' (born '''Loretta Pleasant'''; August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951)<ref name="vpbio">{{cite news|url=http://hamptonroads.com/2010/05/cancer-cells-killed-her-then-they-made-her-immortal|title=Cancer cells killed Henrietta Lacks – then made her immortal|last=Batts|first=Denise Watson|date=2010-05-10|publisher=]|pages=1, 12–14 |accessdate=2012-08-19}} Note: Some sources report her birthday as August 2, 1920, vs. August 1, 1920.</ref> was an ] woman whose cancer cells are the source of the ] cell line, the first ] and one of the most important cell lines in medical research. An immortalized cell line will reproduce indefinitely under specific conditions, and the HeLa cell line continues to be a source of invaluable medical data to the present day.<ref name = "smithsonian>{{cite web|last1=Zielinski|first1=Sarah|title=Cracking the Code of the Human Genome. Henrietta Lacks' 'Immortal' Cells|url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/henrietta-lacks-immortal-cells-6421299/|publisher=Smithsonian|accessdate=2016-12-31|date=2010-01-02}}</ref> | |||

| '''Henrietta Lacks''' (born '''Loretta Pleasant'''; August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951)<ref name="vpbio">{{cite news |last1=Batts |first1=Denise Watson |title=Cancer cells killed Henrietta Lacks – then made her immortal |url=http://hamptonroads.com/2010/05/cancer-cells-killed-her-then-they-made-her-immortal |newspaper=] |pages=1, 12–14| date=May 10, 2010 |access-date=February 20, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100513065957/http://hamptonroads.com/2010/05/cancer-cells-killed-her-then-they-made-her-immortal |archive-date=May 13, 2010}} Note: Some sources report her birthday as August 2, 1920, vs. August 1, 1920.</ref> was an African-American woman<ref>{{cite web |last1=Butanis |first1=Benjamin |title=The Legacy of Henrietta Lacks |url=https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henriettalacks/index.html |website=Johns Hopkins Medicine|access-date=August 2, 2018}}</ref> whose ]s are the source of the ] cell line, the first ]{{efn-ua|"In Steve Silberman's Book Review of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Nature 463, 610; 2010), ... Your lead-in claims that the death of Henrietta Lacks "led to the first immortal cell line", but that distinction belongs to the L929 cell line, which was derived from mouse connective tissue and described almost a decade earlier (W. Earle J. Natl Cancer Inst. 4, 165–212; 1943). As Silberman notes, Lacks's was the first mass-produced human cell line."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hayflick |first1=Leonard |title=Myth-busting about first mass-produced human cell line |journal=] |date=March 4, 2010 |volume=464 |issue=7285 |page=30 |doi=10.1038/464030d |bibcode=2010Natur.464...30H |doi-access=free }}</ref>}} and one of the most important cell lines in ]. An immortalized cell line reproduces indefinitely under specific conditions, and the HeLa cell line continues to be a source of invaluable medical data to the present day.<ref>{{cite magazine |last1=Zielinski|first1=Sarah|title=Cracking the Code of the Human Genome. Henrietta Lacks' 'Immortal' Cells|url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/henrietta-lacks-immortal-cells-6421299/|magazine=Smithsonian |date=January 2, 2010 |access-date=December 31, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Lacks was the <!-- Please DO NOT change the following word to "unwilling". Unwillingness requires awareness of what is happening; unwittingness means lack of that awareness-->unwitting source of these cells from a tumor ] during treatment for ] at ] in ], ], U.S., in 1951. These cells were then ] by ] who created the cell line known as HeLa, which is still used for ].<ref>{{cite news |first=Denise | last=Grady|title=A Lasting Gift to Medicine That Wasn't Really a Gift |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/02/health/02seco.html |newspaper=] |date=2010-02-01 |accessdate=2012-08-19}}</ref> As was then the practice, no consent was obtained to culture her cells, nor were she or her family compensated for their extraction or use. | |||

| Lacks was the <!-- Please DO NOT change the following word to "unwilling". Unwillingness requires awareness of what is happening; unwittingness means lack of that awareness-->unwitting source of these cells from a tumor ] during treatment for ] at ] in ], Maryland, in 1951. These cells were then ] by ], who created the cell line known as HeLa, which is still used for medical research.<ref>{{cite news |first=Denise | last=Grady|title=A Lasting Gift to Medicine That Wasn't Really a Gift |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/02/health/02seco.html |newspaper=] |date=February 1, 2010 |access-date=August 19, 2012}}</ref> As was then the practice, no consent was required to culture the cells obtained from Lacks's treatment. Neither she nor her family were compensated for the extraction or use of the HeLa cells. | |||

| Lacks grew up in rural ]. After giving birth to two of their children, she married her cousin David "Day" Lacks. In 1941 the young family moved to ] in ] so Day could work in Bethlehem Steel at Sparrows Point. After Lacks had given birth to their fifth child, she was diagnosed with cancer.<ref>{{citation|last=Skloot|first=Rebecca|authorlink= Rebecca Skloot|title=The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks|year=2010|publisher=]|place=New York City|page=17|isbn=978-1-4000-5217-2|ref=harv}}</ref> Tissue samples from her tumors were taken without consent during treatment and these samples were then subsequently cultured into the HeLa cell line. | |||

| Even though some information about the origins of HeLa's immortalized cell lines was known to researchers after 1970, the Lacks family was not made aware of the line's existence until 1975. |

Even though some information about the origins of HeLa's immortalized cell lines was known to researchers after 1970, the Lacks family was not made aware of the line's existence until 1975. With knowledge of the cell line's ] provenance becoming public, its use for medical research and for commercial purposes continues to raise concerns about privacy and patients' rights. | ||

| == |

==Biography== | ||

| ===Early life=== | |||

| Henrietta Lacks was born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920,<ref name="vpbio"/>{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=18}} in ], to Eliza and Johnny Pleasant.<ref name="O">{{cite news |url= http://www.oprah.com/world/Excerpt-From-The-Immortal-Life-of-Henrietta-Lacks_1/3 |title=Excerpt From The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks |first= Rebecca |last=Skloot |work=oprah.com |date= February 2010 |accessdate=2013-08-09}}</ref> Her family is uncertain how her name changed from Loretta to Henrietta, but she was nicknamed Hennie.<ref name="vpbio"/> When Lacks was four years old in 1924, her mother died giving birth to her tenth child.<ref name="O"/> Unable to care for the children alone after his wife's death, Lacks' father moved the family to ], where the children were distributed among relatives. Lacks ended up with her grandfather, Tommy Lacks, in a two-story log cabin that was once the slave quarters on the plantation that had been owned by Henrietta's white great-grandfather and great-uncle.(She was Mix)<ref name="vpbio"/> She shared a room with her nine-year-old cousin and future husband, David "Day" Lacks (1915–2002).<ref name="O"/> | |||

| Henrietta Lacks was born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920,<ref name="vpbio"/>{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=18}} in ], to Eliza Pleasant (née Lacks) (1886–1924) and John "Johnny" Randall Pleasant (1881–1969).{{sfn|Skloot|2010}} She is remembered as having hazel eyes, a small waist, size 6 shoes, and always wearing red nail polish and a neatly pleated skirt.<ref name="stan">{{cite web |last1=White |first1=Tracie |title=Descendants of Henrietta Lacks Discuss Her Famous Cell Line |url=https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2018/05/descendants-of-henrietta-lacks-discuss-her-famous-cell-line.html |website=Stanford Medicine News Center |date=May 2, 2018|access-date=May 10, 2021}}</ref> Her family is uncertain how her name changed from Loretta to Henrietta, but she was nicknamed Hennie.<ref name="vpbio"/> When Lacks was four years old in 1924, her mother died giving birth to her tenth child.{{sfn|Skloot|2010}} Unable to care for the children alone after his wife's death, Lacks's father moved the family to ], where the children were distributed among relatives. Lacks ended up with her maternal grandfather, Thomas "Tommy" Henry Lacks, in a two-story log cabin that was once the slave quarters on the plantation that had been owned by Henrietta's white great-grandfather and great-uncle.<ref name="vpbio"/> She shared a room with her nine-year-old first cousin and future husband, David "Day" Lacks (1915–2002).{{sfn|Skloot|2010}} | |||

| Like most members of her family living in Clover, Lacks worked as a tobacco farmer starting from an early age. |

Like most members of her family living in Clover, Lacks worked as a tobacco farmer starting from an early age. She fed the animals, tended the garden, and toiled in the tobacco fields. She attended the designated black school two miles away from the cabin until she had to drop out to help support the family when she was in the sixth grade.<ref name="bio">{{cite web |title=Henrietta Lacks Biography |url=https://www.biography.com/scientist/henrietta-lacks |website=Biography |date=March 3, 2021 |access-date=May 10, 2021}}</ref> When Lacks was 14 years old, she gave birth to a son, Lawrence Lacks (1935–2023).<ref>{{cite news |title=Lawrence Lacks Sr., whose mother's cells were taken without consent, dies at 88 |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/obituaries/2023/08/31/lawrence-lacks-henrietta-lacks-obit-2/ |newspaper=Washington Post |date=September 19, 2023}}</ref> In 1939, her daughter Elsie Lacks (1939–1955) was born. Both children were fathered by Day Lacks. Elsie had ] and ]<ref name="cg" /> and was described by the family as "different" or "deaf and dumb".<ref name="vpbio"/> | ||

| ===Marriage and family=== | |||

| On April 10, 1941, Day and Henrietta Lacks were married in ].<ref name="vpbio" /> Later that year, their cousin, Fred Garrett, convinced the couple to leave the tobacco farm in Virginia and move to Maryland where Day Lacks could work at ] in ]. Not long after they moved to Maryland, Garrett was called to fight in ]. With the savings gifted to him by Garrett, Day Lacks was able to purchase a house at 713 New Pittsburgh Avenue in Turner Station. Now part of ], Turner Station was one of the oldest and largest ] communities in ] at that time.<ref name="bcrecord">{{cite web|url=http://resources.baltimorecountymd.gov/Documents/Planning/historic/survey_districts/turners_station.pdf|title=Turner's Station African American Survey District, Dundalk, Baltimore County 1900–1950|format=PDF|publisher=]|accessdate=2012-08-19}}</ref><ref name="aathematic">{{cite web|url=http://resources.baltimorecountymd.gov/Documents/Planning/historic/aathematic.pdf|format=PDF|title=Baltimore county architectural survey African American Thematic Study|publisher=Baltimore County Office of Planning and The Landmarks Preservation Commission|accessdate=2012-08-19}}</ref> | |||

| On April 10, 1941, David "Day" Lacks and Henrietta Lacks were married in ].<ref name="vpbio" /> Later that year, their cousin, Fred Garrett, convinced the couple to leave the tobacco farm in Virginia and move to Turner Station, near ], in ], so Day could work in ] at ]. Not long after they moved to Maryland, Garrett was called to fight in ]. With the savings gifted to him by Garrett, Day Lacks was able to purchase a house at 713 New Pittsburgh Avenue in Turner Station. Now part of Dundalk, Turner Station was one of the oldest and largest African-American communities in Baltimore County at that time.<ref name="bcrecord">{{cite web|url=http://resources.baltimorecountymd.gov/Documents/Planning/historic/survey_districts/turners_station.pdf|title=Turner's Station African American Survey District, Dundalk, Baltimore County 1900–1950|publisher=]|access-date=August 19, 2012}}</ref><ref name="aathematic">{{cite web|url=http://resources.baltimorecountymd.gov/Documents/Planning/historic/aathematic.pdf|title=Baltimore county architectural survey African American Thematic Study|publisher=Baltimore County Office of Planning and The Landmarks Preservation Commission|access-date=August 19, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Living in Maryland, Henrietta and Day Lacks had three more children: David "Sonny" Lacks |

Living in Maryland, Henrietta and Day Lacks had three more children: David "Sonny" Lacks Jr. (1947–2022),<ref>{{cite news |last1=Belson |first1=Dan |title=Lacks family members honored after death |url=https://www.dundalkeagle.com/news/lacks-family-members-honored-after-death/article_08d478ec-4077-5da5-83d6-8a772322f3aa.html |work=Dundalk Eagle |date=February 9, 2022 |language=en}}</ref> Deborah Lacks (later known as Deborah Lacks Pullum, 1949–2009), and Joseph Lacks (later known as Zakariyya Bari Abdul Rahman after converting to Islam, 1950–2020).<ref>{{cite web |author1=Brooks Clinton Funeral Service, P.A. |title=Zakariyya Rahman |url=https://www.tributearchive.com/obituaries/18588297/zakariyya-rahman}}</ref> Henrietta gave birth to her last child at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore in November 1950, four and a half months before she was diagnosed with cervical cancer.<ref name="vpbio"/> Zakariyya believed his birth to be a miracle as he was "fighting off the cancer cells growing all around him". Around the same time, Elsie was placed in the Hospital for the Negro Insane, later renamed ], where she died in 1955 at 15 years of age.<ref name="vpbio"/> Historian Paul Lurz says that it is possible that Elsie was subjected to the ] procedure, where a hole was drilled into a patient's head to drain fluid from the brain, which was then replaced with oxygen or helium to make it easier to see the patient's brain in X-rays.<ref name="cg">{{cite web |last1=Marquardt |first1=Tom |title=Tragic Chapter of Crownsville State Hospital's Legacy |url=http://www.capitalgazette.com/cg-tragic-chapter-of-crownsville-state-hospitals-legacy-20140730-story.html. |website=Capital Gazette |date=June 5, 2013 |access-date=May 10, 2021}}</ref> | ||

| Both Lacks and her husband were Catholic.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Nott|first=Rohini|date=October 9, 2020|title=Henrietta Lacks (1920–1951)|url=https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/henrietta-lacks-1920-1951#:~:text=Both%20Lacks%20and%20her%20husband,called%20Elsie,%20had%20developmental%20disabilities.&text=In%201951,%20doctors%20diagnosed%20Lacks,Hopkins%20Hospital%20in%20Baltimore,%20Maryland.|publisher=The Embryo Project Encyclopedia |access-date=December 14, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ==Illness== | |||

| === |

===Illness=== | ||

| On January 29, 1951, Lacks went to Johns Hopkins, the only hospital in the area that treated black patients, because she felt a "knot" in her womb.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=13}} She had previously told her cousins about the "knot" and they assumed correctly that she was pregnant. But after giving birth, Lacks had a severe ]. Her primary care doctor tested her for ], which came back negative, and referred her back to Johns Hopkins. There, her doctor, ], took a ] of the mass on Lacks' ] for laboratory testing. Soon after, Lacks was told that she had a malignant ] of the cervix.{{efn|] is a cancer of the squamous cells, a type of epithelial cell, and is the second most-common type of skin cancer. They are found on the neck, head, cervix, anus as well as other body sites.<ref>{{cite web|title=Squamous Cell Carcinoma|url=http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/squamous-cell-carcinoma|publisher=Skin Cancer Foundation|accessdate=2016-12-31}}</ref>}}{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=27}} In 1970, physicians discovered that she had been misdiagnosed and actually had an ].{{efn|]s are a type of cancerous tumor or an abnormal growth of epithelial tissue. 10% to 15% of cancers of the cervix are adenocarcinomas, the rest more commonly being squamous cell carcinomas.<ref name=WCR2014>{{cite book|title=World Cancer Report 2014.|date=2014|publisher=]|isbn=92-832-0429-8|pages=Chapter 5.3}}</ref>}} This was a common mistake at the time and the treatment would not have differed.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|pp=172}} | |||

| ====Diagnosis and treatment==== | |||

| Lacks was treated with ] as an inpatient and discharged a few days later with instructions to return for X-ray treatments as a follow-up. During her treatments, two samples were taken from Lacks' cervix without her permission or knowledge; one sample was of healthy tissue and the other was cancerous.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=33}} These samples were given to ], a physician and cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. The cells from the cancerous sample eventually became known as the ] ], a commonly used ] in contemporary ].<ref name="vpbio"/> | |||

| On January 29, 1951, Lacks went to Johns Hopkins, the only hospital in the area that treated black patients, because she felt a "knot" in her womb.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=13}} She had previously told her cousins about the "knot" and they assumed correctly that she was pregnant. But after giving birth to Joseph, Lacks had a severe ]. Her primary care doctor, William C. Wade,<ref>{{cite web |title=Biography of Mrs. Henrietta Lacks |url=https://henriettalackslegacygroup.org/the-amazing-henrietta-lacks/about-henrietta/ |publisher=Henrietta Lacks Legacy Group |access-date=April 2, 2023 |quote=Mrs. Lacks’ story is not complete without a history of Turner Station (where she resided at the time of her death), Dr. William C. Wade (her African American primary care physician), ...}}</ref> referred her back to Johns Hopkins.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Taylor |first1=Alexis |title=Henrietta Lacks Honored with Plaque |url=https://afro.com/henrietta-lacks-honored-with-plaque/ |publisher=] |access-date=February 11, 2024 |date=October 9, 2013 |quote=Henrietta Lacks was only 30 years old when her primary care doctor, William C. Wade, sent her to Johns Hopkins University Hospital to treat a mysterious ailment wreaking havoc on her body.}}</ref> There, her doctor, ], took a ] of a mass found on Lacks's ] for laboratory testing. Soon after, Lacks was told that she had a malignant ] of the cervix.{{efn-ua|] is a cancer of the squamous cells, a type of epithelial cell, and is the second-most common type of skin cancer. They are found on the neck, head, cervix, and anus, as well as other body sites.<ref>{{cite web|title=Squamous Cell Carcinoma|url=http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/squamous-cell-carcinoma|publisher=Skin Cancer Foundation|access-date=December 31, 2016}}</ref>}}{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=27}} In 1970, physicians discovered that she had been misdiagnosed and actually had an ].{{efn-ua|]s are a type of cancerous tumor or an abnormal growth of epithelial tissue. 10% to 15% of cancers of the cervix are adenocarcinomas, the rest more commonly being squamous cell carcinomas.<ref name=WCR2014>{{cite book|title=World Cancer Report 2014.|date=2014|publisher=]|isbn=978-92-832-0429-9|pages=Chapter 5.3}}</ref>}} This was a common mistake at the time, and the treatment would not have differed.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=172}} | |||

| Lacks was treated with ] as an inpatient and discharged a few days later with instructions to return for X-ray treatments as a follow-up. During her treatments, two samples were taken from Lacks's cervix without her permission or knowledge; one sample was of healthy tissue and the other was cancerous.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=33}} These samples were given to ], a physician and cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. The cells from the cancerous sample eventually became known as the ] ], a commonly used ] in contemporary ].<ref name="vpbio"/> | |||

| ===Death and burial=== | ===Death and burial=== | ||

| Line 46: | Line 53: | ||

| ] in Clover, Virginia, near where Lacks grew up and is buried]] | ] in Clover, Virginia, near where Lacks grew up and is buried]] | ||

| Lacks was buried in an unmarked grave in the family cemetery, in a section of Clover, Virginia, called Lackstown. Lacks's exact burial location is unknown, but the family believes that it is within a few feet of her mother's gravesite, which for decades was the only one in the family to have been marked with a tombstone.<ref name="vpbio"/><ref name="Baltimore City News">{{cite news |first=Van |last=Smith |title=Wonder Woman: The Life, Death, and Life After Death of Henrietta Lacks, Unwitting Heroine of Modern Medical Science|url=http://www.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=3426 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040814160109/http://www.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=3426|archive-date=August 14, 2004|newspaper=] |date=April 17, 2002 |access-date=September 19, 2016}}</ref><ref name=JHM2000>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.jhu.edu/~jhumag/0400web/01.html | last=Skloot| first=Rebecca |title=Henrietta's Dance |magazine=Johns Hopkins Magazine |publisher=] |date=April 2000 |access-date=October 12, 2016 }}</ref> In 2010, ], a faculty member of the ] who had worked with George Gey and knew the Lacks family,{{sfn|Skloot|2010|page=page 231}} donated a headstone for Lacks.<ref name="vpbio2"/> This prompted her family to raise money for a headstone for Elsie Lacks as well, which was dedicated on the same day.<ref name=vpbio2/> The book-shaped headstone of Henrietta Lacks contains an epitaph written by her grandchildren that reads:<ref name="vpbio"/> | |||

| Lacks was buried in an unmarked grave in the family cemetery in a place called Lackstown in Halifax County, Virginia. Lackstown is the name that was given to the land in Clover, Virginia, that was originally owned by ], land- and slave-owning members of the Lacks family before the ]. Later generations gave the land to the many ] members of the Lacks family who were descendants of ] slaves and their white owners.<ref name="vpbio"/> | |||

| <div style="text-align:center">{{poemquote| | |||

| |text=<!-- or: 1= -->Henrietta Lacks, August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951 | |||

| Lacks's exact burial location is unknown, but the family believes that it is within a few feet of her mother's grave site, which for decades was the only one in the family to have been marked with a tombstone.<ref name="vpbio"/><ref name="Baltimore City News">{{cite news |first=Van |last=Smith |title=Wonder Woman: The Life, Death, and Life After Death of Henrietta Lacks, Unwitting Heroine of Modern Medical Science|url=http://www.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=3426 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040814160109/http://www.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=3426|archive-date=2004-08-14|newspaper=] |date=2002-04-17 |accessdate=2016-09-19}}</ref><ref name=JHM2000>{{cite journal |url=http://www.jhu.edu/~jhumag/0400web/01.html | last=Skloot| first=Rebecca |title=Henrietta's Dance |accessdate=2016-10-12 |magazine=]|publisher=]|date=April 2000}}</ref> In 2010, ], a faculty member of the ] who had worked with George Gey and knew the Lacks family,<ref>Skloot, page 231</ref> donated a headstone for Lacks.<ref name="vpbio2"/> This prompted her family to raise money for a headstone for Elsie Lacks as well, which was dedicated on the same day.<ref name=vpbio2/> The headstone of Henrietta Lacks is shaped like a book and contains an epitaph written by her grandchildren that reads:<ref name="vpbio"/> | |||

| <center>{{poemquote| | |||

| |text=<!-- or: 1= -->Henrietta Lacks, August 1, 1920 - October 4, 1951 | |||

| In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, | In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, | ||

| wife and mother who touched the lives of many. | wife and mother who touched the lives of many. | ||

| Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal | Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal | ||

| cells will continue to help mankind forever. | cells will continue to help mankind forever. | ||

| Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family<ref>{{cite web|last=McLaughlin |first=Tom |url=http://www.thenewsrecord.com/index.php/news/article/an_epitaph_at_last/ |title=An epitaph, at last | South Boston Virginia News | |

Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family<ref>{{cite web|last=McLaughlin |first=Tom |url=http://www.thenewsrecord.com/index.php/news/article/an_epitaph_at_last/ |title=An epitaph, at last | South Boston Virginia News |work=The News Record |date=2010-05-31 |access-date=2012-12-21}}</ref>}}</div> | ||

| ==Medical and scientific research== | ==Medical and scientific research== | ||

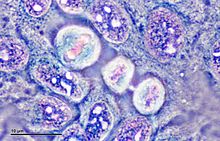

| ] cells in culture. The cells can be seen ] and ], different stages of cell division.]] | ] and ], different stages of cell division.]] | ||

| {{See also|HeLa}} | {{See also|HeLa}} | ||

| George Otto Gey, the first researcher to study Lacks's cancerous cells, observed that |

George Otto Gey, the first researcher to study Lacks's cancerous cells, observed that these cells were unusual in that they reproduced at a very high rate and could be kept alive long enough to allow more in-depth examination.<ref>{{cite magazine |last1=Skloot|first1=Rebecca|title=An Obsession With Culture|url=https://www.pittmag.pitt.edu/mar2001/culture.html|publisher=] |magazine=PITT Magazine |date=March 2001 |access-date=December 31, 2016|quote=By 1950, when Henrietta Lacks walked into Hopkins Hospital complaining of abnormal bleeding, George and Margaret Gey had spent almost thirty years trying to establish an immortal human cell line. ...|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180924174222/http://www.pittmag.pitt.edu/mar2001/culture.html|archive-date=September 24, 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref> Until then, cells cultured for laboratory studies survived for only a few days at most, which was not long enough to perform a variety of different tests on the same sample. Lacks's cells were the first to be observed that could be divided multiple times without dying, which is why they became known as "immortal". After Lacks's death, Gey had Mary Kubicek, his lab assistant, take further HeLa samples while Henrietta's body was at Johns Hopkins' autopsy facility.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Gold|first1=Michael|title=A Conspiracy of Cells: One Woman's Immortal Legacy-And the Medical Scandal It Caused|year=1986|publisher=SUNY Press|page=20}}</ref> The roller-tube technique{{efn-ua|The roller-tube technique was invented by George Gey in his lab at the ]. "And then there was the roller drum, the invention that churned in the enormous incubator room Gey built to keep the cell cultures warm. The huge metal drum with holes covering its inner surface gyrated like a cement mixer 24 hours a day. And tucked within each hole, at the bottom of Gey's home-blown-glass roller tubes, were tiny pieces of tissue bathed in nutrient-rich fluids, gathering the nourishment necessary for survival. As the drum rotated one turn every hour, the cells surfaced, free to breathe and excrete until the liquid bathed them again. If all went well, the cells adhered to the walls of the tubes and began to flourish." – Rebecca Skloot<br /> | ||

| This method of growing tissue cultures was also used in the development of Jonas Salk's polio vaccine and by John Enders in his Nobel prize-winning polio research.<ref>{{cite |

This method of growing tissue cultures was also used in the development of Jonas Salk's polio vaccine and by John Enders in his Nobel prize-winning polio research.<ref>{{cite magazine |last1=Skloot|first1=Rebecca|title=An Obsession With Culture|url=https://www.pittmag.pitt.edu/mar2001/culture.html|publisher=University of Pittsburgh |magazine=PITT Magazine |date=March 2001 |access-date=December 31, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180924174222/http://www.pittmag.pitt.edu/mar2001/culture.html|archive-date=September 24, 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref>}} was the method used to culture the cells obtained from the samples that Kubicek collected.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Lucey|first1=Brendan P.|last2=Nelson-Rees|first2=Walter A.|last3=Hutchins|first3=Grover M.|date=September 1, 2009|title=Henrietta Lacks, HeLa Cells, and Cell Culture Contamination|url=http://www.archivesofpathology.org/doi/10.1043/1543-2165-133.9.1463|journal=]|volume=133|issue=9|pages=1463–1467|doi=10.5858/133.9.1463|pmid=19722756|issn=0003-9985}}</ref> Gey was able to start a cell line from Lacks's sample by isolating one specific cell and repeatedly dividing it, meaning that the same cell could then be used for conducting many experiments. They became known as HeLa cells, because Gey's standard method for labeling samples was to use the first two letters of the patient's first and last names.<ref name="vpbio"/> | ||

| The ability to rapidly reproduce HeLa cells in a laboratory setting has led to many important breakthroughs in biomedical research. For example, by 1954, ] was using HeLa cells in his research to develop the ].<ref name="Baltimore City News"/> To test his new vaccine, the cells were mass-produced in the first-ever cell production factory.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=96}} Additionally, ], a leading virologist, injected HeLa cells into cancer patients, prison inmates, and healthy individuals in order to observe whether cancer could be transmitted as well as to examine if one could become immune to cancer by developing an acquired immune response. |

The ability to rapidly reproduce HeLa cells in a laboratory setting has led to many important breakthroughs in biomedical research. For example, by 1954, ] was using HeLa cells in his research to develop the ].<ref name="Baltimore City News"/> To test his new vaccine, the cells were mass-produced in the first-ever cell production factory.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|p=96}} Additionally, ], a leading virologist, injected HeLa cells into cancer patients, prison inmates, and healthy individuals in order to observe whether cancer could be transmitted as well as to examine if one could become immune to cancer by developing an acquired immune response.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|page=128}} | ||

| HeLa cells were in high demand and put into mass production. They were mailed to scientists around the globe for "research into ], ], the effects of radiation and toxic substances, ], and countless other scientific pursuits".<ref name="Baltimore City News"/> HeLa cells were the first human cells successfully cloned in 1955,<ref>^ Puck TT, Marcus PI. A Rapid Method for Viable Cell Titration and Clone Production With Hela Cells In Tissue Culture: The Use of X-Irradiated Cells to Supply Conditioning Factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1955 |

HeLa cells were in high demand and put into mass production. They were mailed to scientists around the globe for "research into ], ], the effects of radiation and toxic substances, ], and countless other scientific pursuits".<ref name="Baltimore City News"/> HeLa cells were the first human cells successfully cloned, in 1955,<ref>^ Puck TT, Marcus PI. "A Rapid Method for Viable Cell Titration and Clone Production With Hela Cells In Tissue Culture: The Use of X-Irradiated Cells to Supply Conditioning Factors". ''Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.'' 1955 July 15;41(7):432–7. URL: PNASJSTOR.</ref> and have since been used to test human sensitivity to tape, glue, cosmetics, and many other products.<ref name="vpbio"/> There are almost 11,000 patents involving HeLa cells.<ref name="vpbio"/> | ||

| In the early 1970s, a large portion of |

In the early 1970s, a large portion of other cell cultures became contaminated by HeLa cells. As a result, members of Henrietta Lacks's family received solicitations for blood samples from researchers hoping to learn about the family's genetics in order to differentiate between HeLa cells and other cell lines.<ref name=RitterSeattleTimes>{{cite news|last=Ritter|first=Malcolm|title=Feds, family reach deal on use of DNA information|url=http://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/feds-family-reach-deal-on-use-of-dna-information/ |newspaper=] |date=August 7, 2013 |access-date=December 31, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Schwab|first1=Abraham P.|last2=Baily|first2=Mary Ann|last3=Hirschhorn|first3=Kurt|last4=Rhodes|first4=Rosamond|last5=Trusko|first5=Brett|editor1-last=Rhodes|editor1-first=Rosamond|editor2-last=Gligorov|editor2-first=Nada|editor3-last=Schwab|editor3-first=Abraham Paul|title=The Human Microbiome: Ethical, Legal and Social Concerns|date=August 15, 2013|publisher=]|pages=98–99|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jFX1AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA98|quote=In 1973, researchers at Johns Hopkins contacted Lacks family members and asked them to provide blood samples.|isbn=978-0-19-982942-2}}</ref> | ||

| Alarmed and confused, several family members began questioning why they were receiving so many telephone calls requesting blood samples. |

Alarmed and confused, several family members began questioning why they were receiving so many telephone calls requesting blood samples. In 1975, the family also learned through a chance dinner-party conversation that material originating in Henrietta Lacks was continuing to be used for medical research.<ref name="Baltimore City News"/> Prior to this, the family had never discussed Henrietta's illness and death among themselves.<ref name="vpbio" /> | ||

| ===Consent issues and privacy concerns=== | ===Consent issues and privacy concerns=== | ||

| Neither Henrietta Lacks nor her family |

Neither Henrietta Lacks nor her family had given her physicians permission to harvest her cells. At that time, permission was neither required nor customarily sought.<ref>{{cite magazine|last=Washington|first=Harriet|title=Henrietta Lacks: An Unsung Hero|magazine=]|date=October 1994}}</ref> The cells were used in medical research and for commercial purposes.<ref name="Baltimore City News"/><ref name="vpbio"/> In the 1980s, family medical records were published without family consent. A similar issue was brought up in the ] case of '']'' in 1990. The court ruled that a person's discarded tissue and cells are not their property and can be commercialized.{{sfn|Skloot|2010|pages=203–206}} | ||

| In March 2013, researchers published the ] sequence of the ] of a strain of HeLa cells. The Lacks family discovered this when the author ] informed them.<ref name=RitterSeattleTimes/> There were objections from the Lacks family about the genetic information that was available for public access. Jeri Lacks Whye, a grandchild of Henrietta Lacks, said to '']'', "the biggest concern was |

In March 2013, researchers published the ] sequence of the ] of a strain of HeLa cells. The Lacks family discovered this when the author ] informed them.<ref name=RitterSeattleTimes/> There were objections from the Lacks family about the genetic information that was available for public access. Jeri Lacks Whye, a grandchild of Henrietta Lacks, said to '']'', "the biggest concern was privacy—what information was actually going to be out there about our grandmother, and what information they can obtain from her sequencing that will tell them about her children and grandchildren and going down the line." That same year another group working on a different HeLa cell line's genome under ] (NIH) funding, submitted it for publication. In August 2013, an agreement was announced between the family and the NIH that gave the family some control over access to the cells' DNA sequence found in the two studies along with a promise of acknowledgement in scientific papers. In addition, two family members will join the six-member committee that will regulate access to the sequence data.{{efn-ua|"The Lacks family and the N.I.H. settled on an agreement: the data from both studies should be stored in the institutes' database of genotypes and phenotypes. Researchers who want to use the data can apply for access and will have to submit annual reports about their research. A so-called HeLa Genome Data Access working group at the N.I.H. will review the applications. Two members of the Lacks family will be members. The agreement does not provide the Lacks family with proceeds from any commercial products that may be developed from research on the HeLa genome."<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/08/science/after-decades-of-research-henrietta-lacks-family-is-asked-for-consent.html|title=A Family Consents to a Medical Gift, 62 Years Later|last=Zimmer|first=Carl|date=August 7, 2013|newspaper=The New York Times|issn=0362-4331|access-date=December 12, 2016}}</ref>}}<ref name=RitterSeattleTimes/> | ||

| In October 2021, Lacks's estate filed a lawsuit against ] for profiting from the HeLa cell line without Lacks's consent,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/legal-issues/henrietta-lacks-family-sues-company/2021/10/04/810ffa6c-2531-11ec-8831-a31e7b3de188_story.html?carta-url=https%3A%2F%2Fs2.washingtonpost.com%2Fcar-ln-tr%2F34e1aa4%2F615c77ec9d2fda9d41fde1ff%2F5976766bae7e8a6816d6be0f%2F42%2F74%2F615c77ec9d2fda9d41fde1ff |title=Legal Issues: 70 years ago, Henrietta Lacks's cells were taken without consent. Now, her family wants justice. |first1=Emily |last1=Davies |newspaper=] |date=October 4, 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://endpts.com/estate-of-henrietta-lacks-sues-thermo-fisher-over-the-improper-sale-of-her-immortal-cells/|title=Estate of Henrietta Lacks sues Thermo Fisher over the improper sale of her immortal cells|first=Zachary|last= Brennan|website=Endpoints|date=October 4, 2021}}</ref> asking for "the full amount of net profits".<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/05/us/henrietta-lacks-estate-sues-biotech-company/index.html |title=Estate of Henrietta Lacks sues biotechnical company for nonconsensual use of her cells |first1=Taylor |last1=Romine |publisher=] |date=October 5, 2021}}</ref> On July 31, 2023, Thermo Fisher Scientific settled with the Lacks family on undisclosed terms.<ref name="apnews_20230801_thermosettlement">{{cite news | last = Skene | first = Lea | date = August 1, 2023 | title = Thermo Fisher Scientific settles with family of Henrietta Lacks, whose HeLa cells uphold medicine | url = https://apnews.com/article/henrietta-lacks-hela-cells-thermo-fisher-scientific-bfba4a6c10396efa34c9b79a544f0729 | publisher = AP News | access-date = August 1, 2023 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230801160640/https://apnews.com/article/henrietta-lacks-hela-cells-thermo-fisher-scientific-bfba4a6c10396efa34c9b79a544f0729 | archive-date = August 1, 2023 | url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Recognition== | ==Recognition== | ||

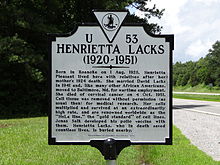

| ] memorializing Henrietta Lacks in Clover, Virginia]] | ] memorializing Henrietta Lacks in Clover, Virginia]] | ||

| ] | |||

| In 1996, ] held its first annual HeLa Women's Health Conference. Led by physician ], the conference is held to give recognition to Henrietta Lacks, her cell line, and "the valuable contribution made by African Americans to medical research and clinical practice".<ref>{{cite web|author1=Roland A. Pattillo, MD|author2=Roland Matthews, MA|title=Tenth Annual HeLa Women's Health Conference:An Overview and Historical Perspective|url=https://ethndis.org/priorsuparchives/ethn-16-2s3-56.pdf|website=Journal of Ethnicity and Disease|publisher=International Society on Hypertension in Blacks|accessdate=2016-10-28|date=Spring 2006}}</ref><ref name="vpbio2"/><ref name="FirstYear">{{cite web|title=2011 First Year Book Program - The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks|url=http://fyb.umd.edu/2011/characters.html|publisher=]|accessdate=2016-09-26}} | |||

| In 1996, ] held its first annual HeLa Women's Health Conference. Led by physician ], the conference is held to give recognition to Henrietta Lacks, her cell line, and "the valuable contribution made by African Americans to medical research and clinical practice".<ref>{{cite web|first=Roland A.|last= Pattillo, MD|author2=Roland Matthews, MA|title=Tenth Annual HeLa Women's Health Conference: An Overview and Historical Perspective|url=https://ethndis.org/priorsuparchives/ethn-16-2s3-56.pdf|website=Journal of Ethnicity and Disease|publisher=International Society on Hypertension in Blacks |date=Spring 2006 |access-date=October 28, 2016}}</ref><ref name="vpbio2"/><ref name="FirstYear">{{cite web|title=2011 First Year Book Program – The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks|url=http://fyb.umd.edu/2011/characters.html|publisher=]|access-date=September 26, 2016|archive-date=October 27, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161027202022/http://fyb.umd.edu/2011/characters.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> The mayor of Atlanta declared the date of the first conference, October 11, 1996, "Henrietta Lacks Day".{{sfn|Skloot|2010|page=219}} | |||

| </ref> The mayor of Atlanta declared the date of the first conference, October 11, 1996, "Henrietta Lacks Day".<ref>Skloot, Page 219</ref> | |||

| Lacks's contributions continue to be celebrated at yearly events in Turner Station.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Wenger|first1=Yvonne|title=Henrietta Lacks honored in 15th annual Turners Station celebration|url=http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2012-08-04/news/bs-md-co-henrietta-lacks-turners-station-20120804_1_henrietta-lacks-immortal-cells-rebecca-skloot| |

Lacks's contributions continue to be celebrated at yearly events in Turner Station.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Wenger|first1=Yvonne|title=Henrietta Lacks honored in 15th annual Turners Station celebration|url=https://www.baltimoresun.com/2012/08/04/henrietta-lacks-honored-in-15th-annual-turners-station-celebration/|newspaper=]|date=August 4, 2012|access-date=October 27, 2016|archive-date=October 28, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161028083523/http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2012-08-04/news/bs-md-co-henrietta-lacks-turners-station-20120804_1_henrietta-lacks-immortal-cells-rebecca-skloot|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Rodman|first1=Nicole|title=Honoring the legacy of Henrietta Lacks|url=https://www.pressreader.com/usa/the-dundalk-eagle/20160804/281522225467391|via=PressReader.Com|newspaper=] |date=August 4, 2016 |access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> At one such event in 1997, then-U.S. Congressman from Maryland, ], presented a congressional resolution recognizing Lacks and her contributions to medical science and research.<ref name=thomas>{{citation|title=In Memory Of Henrietta Lacks – Hon. Robert L. Ehrlich, Jr. (Extension of Remarks – June 4, 1997)|date=June 4, 1997|url=https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/1997/6/4/extensions-of-remarks-section/article/e1109-1?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22In+Memory+Of+Henrietta+Lacks%22%5D%7D&r=1|work=Congressional Record 105th Congress (1997–1998)|publisher=The Library of Congress|access-date=May 3, 2016}}</ref> | ||

| In 2010, the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research established the annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture Series<ref>{{cite web|title=Family Recognition, Community Awards, And Author Highlight Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture 2010|url=http://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/consulting/consulting-services/research-participant-and-community-partnerships-core/community-resources/the-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture/past-lectures/family-recognition-community-awards-and-author-highlight-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture-2010/|publisher=The Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research| |

In 2010, the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research established the annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture Series,<ref>{{cite web|title=Family Recognition, Community Awards, And Author Highlight Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture 2010|url=http://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/consulting/consulting-services/research-participant-and-community-partnerships-core/community-resources/the-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture/past-lectures/family-recognition-community-awards-and-author-highlight-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture-2010/|publisher=The Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research |date=October 2, 2010 |access-date=June 17, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170116214724/http://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/consulting/consulting-services/research-participant-and-community-partnerships-core/community-resources/the-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture/past-lectures/family-recognition-community-awards-and-author-highlight-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture-2010/|archive-date=January 16, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> to honor Henrietta Lacks and the global impact of HeLa cells on medicine and research.<ref>{{cite web|title=Past Lectures|url=http://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/consulting/consulting-services/research-participant-and-community-partnerships-core/community-resources/the-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture/past-lectures/|publisher=The Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research|access-date=June 17, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160809040043/http://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/consulting/consulting-services/research-participant-and-community-partnerships-core/community-resources/the-henrietta-lacks-memorial-lecture/past-lectures/|archive-date=August 9, 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref> | ||

| In 2011, ] in Baltimore granted Lacks a posthumous honorary doctorate in public service.<ref>{{cite web|title=Henrietta Lack Receives an Honorary Degree|url= |

In 2011, ] in Baltimore granted Lacks a posthumous honorary doctorate in public service.<ref>{{cite web|title=Henrietta Lack Receives an Honorary Degree|url=https://www.npr.org/2011/05/23/136587856/henrietta-lacks-receives-honorary-degree|publisher=NPR |work=All Things Considered |date=May 23, 2011 |access-date=December 30, 2016}}</ref> Also in 2011, the ] in ], named their new high school focused on medical careers the ], becoming the first organization to memorialize her publicly by naming a school in her honor.<ref>{{cite news|last=Buck|first=Howard|title=Bioscience school gets official name|url=http://www.columbian.com/news/2011/sep/14/bioscience-school-gets-official-name/ |newspaper=] |date=September 14, 2011|access-date=August 19, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Laufe|first1=Anne|title=New Vancouver high school will focus on health and medical careers|url=http://www.oregonlive.com/clark-county/index.ssf/2012/10/new_vancouver_high_school_will.html |newspaper=] |date=October 2, 2012 |access-date=March 31, 2017}}</ref> | ||

| In 2014, Lacks was inducted into the ].<ref name=MSAWHF>{{cite web|last1=Squires|first1=Emily Oland|title=Maryland Women's Hall of Fame Online|url=http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshall/html/whflist.html| |

In 2014, Lacks was inducted into the ].<ref name=MSAWHF>{{cite web|last1=Squires|first1=Emily Oland|title=Maryland Women's Hall of Fame Online|url=http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshall/html/whflist.html|publisher=The Maryland State Archives|access-date=November 6, 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Henrietta Lacks (1920–1951) (Maryland Women's Hall of Fame)|url=http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshall/html/lacks.html|publisher=Maryland State Archives|access-date=January 7, 2017}}</ref> In 2017, a ] in the ] was named "]" in her honor.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.minorplanetcenter.net/db_search/show_object?utf8=%E2%9C%93&object_id=lacks|title=IAU Minor Planet Center|website=minorplanetcenter.net|access-date=April 21, 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Chamberlin|first1=Alan|title=JPL Small-Body Database Browser|url=https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=359426|publisher=Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology |date=March 14, 2017 |access-date=April 23, 2017}}</ref> | ||

| In 2018, '']'' published a belated obituary for her,<ref>{{cite news|author=Adeel Hassan |url=https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overlooked-henrietta-lacks.html |title=Henrietta Lacks, Whose Cells Led to a Medical Revolution |work=The New York Times |date=March 8, 2018 |access-date=March 9, 2018}}</ref> as part of the ] history project.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/08/insider/overlooked-obituary.html|title=How an Obits Project on Overlooked Women Was Born|last=Padnani|first=Amisha|author-link=Amy Padnani|date=March 8, 2018|work=The New York Times|access-date=March 24, 2018}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/obituaries/overlooked.html|title=Remarkable Women We Overlooked in Our Obituaries|last=Padnani|first=Amisha|date=March 8, 2018|work=The New York Times|access-date=March 24, 2018}}</ref> Also in 2018, the ] and the ] jointly announced the accession of a portrait of Lacks by ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://newsdesk.si.edu/releases/national-portrait-gallery-presents-portrait-henrietta-lacks-co-acquisition-national-museum-|title=National Portrait Gallery Presents a Portrait of Henrietta Lacks, a Co-Acquisition With the National Museum of African American History and Culture|website=newsdesk.si.edu|author=Staff (News Release)|date=May 8, 2018|access-date=May 8, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| On October 6, 2018, ] announced plans to name a research building in honor of Lacks.<ref name=":0">{{Cite news|url=https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/johns-hopkins-university-johns-hopkins-medicine-and-family-of-henrietta-lacks-announce-plans-to-name-a-research-building-in-honor-of-henrietta-lacks|title=Johns Hopkins University, Johns Hopkins Medicine and Family of Henrietta Lacks Announce Plans to Name a Research Building in Honor of Henrietta Lacks|date=October 6, 2018|work=Johns Hopkins Medicine Newsroom|access-date=October 8, 2018}}</ref> The announcement was made at the 9th annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture in the Turner Auditorium in ] by Johns Hopkins University President ] and ], CEO of ] and dean of the medical faculty of the ], surrounded by several of Lacks's descendants. "Through her life and her immortal cells, Henrietta Lacks made an immeasurable impact on science and medicine that has touched countless lives around the world," Daniels said. "This building will stand as a testament to her transformative impact on scientific discovery and the ethics that must undergird its pursuit. We at Johns Hopkins are profoundly grateful to the Lacks family for their partnership as we continue to learn from Mrs. Lacks's life and to honor her enduring legacy." The building will adjoin the Berman Institute of Bioethics' Deering Hall, located at the corner of Ashland and Rutland Avenues and "will support programs that enhance participation and partnership with members of the community in research that can benefit the community, as well as extend the opportunities to further study and promote research ethics and community engagement in research through an expansion of the Berman Institute and its work."<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| In 2020, Lacks was inducted into the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.womenofthehall.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lacks-Henrietta-11.11.2020-Press-Release.pdf|title=National Women's Hall of Fame Virtual Induction Series Inaugural Event December 10, 2020|date=November 11, 2020|access-date=November 12, 2020|archive-date=October 9, 2022|archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://www.womenofthehall.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lacks-Henrietta-11.11.2020-Press-Release.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| In 2021, the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act of 2019 became law; it states the ] must complete a study about barriers to participation that exist in cancer clinical trials that are federally funded for populations that have been underrepresented in such trials.<ref>🖉{{Cite web|url=https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/bill-announcement-010521-2/|via=]|work=]|title=Bill Announcement}}</ref> | |||

| In October 2021, the ] unveiled a ] at ] in the city. The sculpture was created by ] and was the first statue of a black woman made by a black woman for a public space in the United Kingdom.<ref>{{cite news |title=For 'unrecognised black women': statue of Henrietta Lacks unveiled in Bristol |url=https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/oct/04/for-unrecognised-black-women-statue-of-henrietta-lacks-unveiled-in-bristol |access-date=October 4, 2021 |first=Steven|last=Morris|newspaper=The Guardian |date=October 4, 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| On October 13, 2021, the ] (WHO) presented the Director General Award to Lawrence Lacks, the son of Henrietta Lacks, in recognition of her unknowing contribution to science and medicine.<ref name="cramer">{{cite web|last=Cramer|first=Maria|title=Henrietta Lacks, Whose Cells Were Taken Without Her Consent, Is Honored by W.H.O.|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/13/science/henrietta-lacks-cells-who.html|work=The New York Times|date=October 13, 2021|access-date=October 14, 2021}}</ref> ], chief scientist at the WHO, said: "I cannot think of any other single cell line or lab reagent that's been used to this extent and has resulted in so many advances."<ref name="cramer"/> | |||

| On March 15, 2022, United States Rep. ] (D-Md) filed legislation to posthumously award the ] to Henrietta Lacks for her distinguished contributions to science. The award is one of the most prestigious civilian honors given by the United States government.<ref>{{Cite news |title=Bill would honor Henrietta Lacks with posthumous Congressional Gold Medal |language=en-US |newspaper=] |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/bill-would-honor-henrietta-lacks-with-posthumous-congressional-gold-medal/2022/03/24/bec02038-ab1b-11ec-b06d-7b66e120cc89_story.html |access-date=August 31, 2022 |issn=0190-8286}}</ref> | |||

| On December 19, 2022, it was announced that a bronze statue honoring Henrietta Lacks would be erected in ]'s Henrietta Lacks Plaza, previously named Lee Plaza after Confederate Gen. ]. A statue of Lee was removed from the site in the wake of the protests following the murder of George Floyd.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Ross |first1=Kendall |title=Henrietta Lacks' hometown will build statue of her where Robert E. Lee sculpture once stood |url=https://abcnews.go.com/US/henrietta-lacks-hometown-build-statue-robert-lee-sculpture/story?id=95541987 |access-date=December 20, 2022 |work=ABC News |date=December 19, 2022 |language=en}}</ref> The Lacks statue was unveiled on October 4, 2023.<ref>{{Cite web |first=David |last=Hungate |date=October 4, 2023 |title=Photos: Henrietta Lacks statue unveiling |url=https://starexponent.com/photos-henrietta-lacks-statue-unveiling/collection_c7044779-a3fd-5e31-a8f4-2cf545986eba.html |access-date=October 11, 2023 |website=Culpeper Star-Exponent |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| On June 13, 2023, ] Board members approved naming a new school Henrietta Lacks Elementary School in ]. The school serves more than 800 students from preschool through 2nd grade and opened in August 2024.<ref>{{cite news |date=June 14, 2023 |title=New Aldie school named for life-saving cell contributor |language=en-US |newspaper=] |url=https://www.loudountimes.com/news/education/new-aldie-school-named-for-life-saving-cell-contributor/article_59d1f7d4-0b03-11ee-b3db-83e042827fbb.html |access-date=June 24, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=August 26, 2024 |title=Henrietta Lacks Elementary to be Loudoun County Public School Only Primary School |language=en-US | |||

| |url=https://www.lcps.org/article/1725149 |access-date=December 21, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ===In popular culture=== | ===In popular culture=== | ||

| The question of how and whether her race affected her treatment, the lack of obtaining consent, and her relative obscurity |

The question of how and whether her race affected her treatment, the lack of obtaining consent, and her relative obscurity continues to be controversial.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2010/02/henrietta-lacks-and-race/35286/ |title=Henrietta Lacks And Race |first1=Ta-Nehisi |last1=Coates |author-link=Ta-Nehisi Coates|date=February 3, 2010 |work=] |access-date=January 15, 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=A Lesson From the Henrietta Lacks Story: Science Needs Your Cells |first1=Holly Fernandez |last1=Lynch |first2=Steven |last2=Joffe |date=April 21, 2017 |newspaper=The New York Times }}</ref> | ||

| The HeLa cell line's connection to Henrietta Lacks was first brought to popular attention in March 1976 with a pair of articles in the '']''<ref name="Free Press">{{cite news|url=https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/98224087/| |

The HeLa cell line's connection to Henrietta Lacks was first brought to popular attention in March 1976 with a pair of articles in the '']''<ref name="Free Press">{{cite news|url=https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/98224087/|url-access=subscription |title=The HeLa Strain|author=Rogers, Michael|author-link=Michael A. Rogers|newspaper=]|page=47|via=] |date=March 21, 1976 |access-date=March 2, 2017}}</ref> and '']'' written by reporter ], though Rogers erroneously states her name as Helen Lane.<ref name="] |date=March 25, 1976 |access-date=March 2, 2017}}</ref> In 1998, ] directed a ] documentary about Henrietta Lacks called ''The Way of All Flesh''.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Curtis|first1=Adam|title=The Undead Henrietta Lacks And Her Immortal Dynasty|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/adamcurtis/entries/cc9e5db9-5b2f-3297-bb17-dbc119c4ad8d |publisher=BBC |date=June 25, 2010 |access-date=January 6, 2017}}</ref> | ||

| ] documented extensive histories of both the HeLa cell line and the Lacks family in two articles published in 2000<ref name=JHM2000/> and 2001<ref> |

] documented extensive histories of both the HeLa cell line and the Lacks family in two articles published in 2000<ref name=JHM2000/> and 2001<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2001/11/17/arts/cells-that-save-lives-are-a-mother-s-legacy.html |title=Cells That Save Lives are a Mother's Legacy|first=Rebecca|last= Skloot|newspaper=The New York Times|date=November 17, 2001}}</ref> and in her 2010 book '']''. Skloot worked with Deborah Lacks, who was determined to learn more about her mother, on the book.<ref name="stan" /> She used her first royalty check from the book to start the Henrietta Lacks Foundation, which has provided funds like college tuition and medical procedures for Henrietta's family.<ref name="wp">{{cite news |last1=Hendrix |first1=Steve |title=On the Eve of an Oprah Movie about Henrietta Lacks, an Ugly Feud Consumes the Family |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/on-the-eve-of-an-oprah-movie-about-henrietta-lacks-an-ugly-feud-consumes-the-family/20 |newspaper=The Washington Post |access-date=May 10, 2021}}</ref> | ||

| ] announced in 2010 that ] and ] were developing a ] based on Skloot's book,<ref name="vpbio2">{{cite news|url=http://hamptonroads.com/2010/05/after-60-years-anonymity-henrietta-lacks-has-headstone|title=After 60 years of anonymity, Henrietta Lacks has a headstone|last=Batts|first=Denise Watson|date= |

] announced in 2010 that ] and ] were developing a ] based on Skloot's book,<ref name="vpbio2">{{cite news|url=http://hamptonroads.com/2010/05/after-60-years-anonymity-henrietta-lacks-has-headstone|title=After 60 years of anonymity, Henrietta Lacks has a headstone|last=Batts|first=Denise Watson|date=May 30, 2010|work=]|pages=HR1,7|access-date=August 19, 2012|archive-date=August 22, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120822061834/http://hamptonroads.com/2010/05/after-60-years-anonymity-henrietta-lacks-has-headstone|url-status=dead}}</ref> and in 2016 filming commenced.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Britto|first1=Brittany|title=Oprah Winfrey spotted in Baltimore as 'Henrietta Lacks' movie films in city|url=http://www.baltimoresun.com/features/baltimore-insider-blog/bal-oprah-winfrey-sightings-in-baltimore-20160921-story.html|newspaper=The Baltimore Sun |date=September 21, 2016 |access-date=December 31, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/oprah-winfrey-star-hbo-films-889379|title=Oprah Winfrey to Star in HBO Films' 'The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks'|date=May 2, 2016|first=Kate|last=Stanhope|work=]|access-date=May 3, 2016}}</ref> with Winfrey in the leading role of Deborah Lacks, Henrietta's daughter.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Jordan|first1=Tina|title=See the first photos of Oprah Winfrey in HBO's Henrietta Lacks movie|url=https://ew.com/tv/2016/12/22/oprah-winfrey-hbo-henrietta-lacks-movie/|newspaper=]|date=December 22, 2016 |access-date=December 31, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{citation|first=Lorena|last=Blas|title=Oprah Winfrey to star in HBO's 'Henrietta Lacks' movie|url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/tv/2016/05/02/oprah-winfrey-hbo-the-immortal-life-of-henrietta-lacks/83833298/|newspaper=]|date=May 2, 2016}}</ref> The film '']'' was released in 2017, with ] portraying Lacks. Sons David Lacks Jr. and Zakariyya Rahman and granddaughter Jeri Lacks were consultants for the film. | ||

| HBO also commissioned Kadir Nelson for an oil painting of Lacks. In 2018, the portrait was jointly acquired by the ] and the ]'s ]. The wallpaper in the painting is made up of the "Flower of Life" alluding to the immortality of her cells. The flowers on her dress resemble images of cell structures, and the two missing buttons on her dress symbolize her cells taken without permission.<ref name="sm">{{cite web |title=Henrietta Lacks (HeLa): The Mother of Modern Medicine |url=https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.2018.9. |website=Smithsonian Institution |access-date=October 27, 2022}}</ref><ref name="smithmag">{{cite web |last1=Smith |first1=Ryan P. |title=Famed for 'Immortal' Cells, Henrietta Lacks Is Immortalized in Portraiture |url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/famed-immortal-cells-henrietta-lacks-immortalized-portraiture-180969085/ |website=Smithsonian Magazine |date=May 15, 2018|access-date=May 10, 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Members of the Lacks family authored their own stories for the first time in 2013 when Lacks's oldest son and his wife, Lawrence and Bobbette Lacks, wrote a short digital memoir called "Hela Family Stories: Lawrence and Bobbette" with first-hand accounts of their memories of Henrietta Lacks while she was alive and of their own efforts to keep the youngest children out of unsafe living environments following their mother's death.<ref>{{citation|title=Welcome to HeLa Family Stories|year=2013|url=http://www.helafamilystories.com|accessdate=2016-05-03|publisher=HeLa Family Enterprise, LLC}}</ref> | |||

| NBC's '']'' aired its own fictionalized version of Lacks's story in the 2010 episode "Immortal", which '']'' referred to as "shockingly close to the true story"<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.slate.com/content/slate/blogs/browbeat/2010/05/19/ripped_from_which_headline_immortal.html |title=Ripped From Which Headline? "Immortal"|first=June|last=Thomas |date=May 19, 2010 |website=] |access-date=August 19, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110818102426/https://slate.com/content/slate/blogs/browbeat/2010/05/19/ripped_from_which_headline_immortal.html|archive-date=August 18, 2011}}</ref> and the musical groups ] and ] both released songs about Henrietta Lacks and her legacy.<ref>{{cite web|first=Jess|last=Kamen|title=Holiday In Baltimore|date=June 23, 2014|url=http://www.citypaper.com/music/bcp-cms-1-1707767-migrated-story-cp-2014-06-25musi-20140623-story.html|archive-url=https://archive.today/20160712140830/http://www.citypaper.com/music/bcp-cms-1-1707767-migrated-story-cp-2014-06-25musi-20140623-story.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=July 12, 2016|newspaper=Baltimore City Paper}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nme.com/news/yeasayer/63816|title=Yeasayer reveal new track 'Henrietta' – listen|date=May 16, 2012|publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| The HeLa Project, a multimedia exhibition to honor Lacks, opened in 2017 in Baltimore at the ]. It included a portrait by ] and a poem by ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://goodblacknews.org/2017/04/03/the-hela-project-exhibition-travels-to-ny-atl-to-honor-mortal-life-of-henrietta-lacks-before-premiere-of-hbo-film/ |title="The HeLa Project" Exhibition Travels to NY, ATL to Honor Mortal Life of Henrietta Lacks Before Premiere of HBO Film |publisher=Good Black News |date=2017 |accessdate=2017-04-05}}</ref> | |||

| Members of the Lacks family wrote their own stories for the first time in 2013, when Lacks's oldest son and his wife, Lawrence and Bobbette Lacks, wrote a short digital memoir called "Hela Family Stories: Lawrence and Bobbette", with first-hand accounts of their memories of Henrietta Lacks while she was alive and of their own efforts to keep the youngest children out of unsafe living environments following their mother's death.<ref>{{cite web|title=Welcome to HeLa Family Stories|year=2013|url=http://www.helafamilystories.com |publisher=HeLa Family Enterprise, LLC |access-date=May 3, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The HeLa Project, a multimedia exhibition to honor Lacks, opened in 2017 in Baltimore at the ]. It included a portrait by ] and a poem by ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sideshowtheatre.org/hela.html |title=HeLa |publisher=Sideshow Theatre Company |date=2018 |access-date=September 27, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| ''HeLa'', a play by Chicago playwright ], was commissioned by ] in 2016, with a public staged reading on July 31, 2017. The play was produced by Sideshow at Chicago's ] from November 18 to December 23, 2018. The play uses Lacks's life story as a jumping point for a larger conversation about Afrofuturism, scientific progress, and bodily autonomy.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://goodblacknews.org/2017/04/03/the-hela-project-exhibition-travels-to-ny-atl-to-honor-mortal-life-of-henrietta-lacks-before-premiere-of-hbo-film/ |title="The HeLa Project" Exhibition Travels to NY, ATL to Honor Mortal Life of Henrietta Lacks Before Premiere of HBO Film |publisher=Good Black News |date=2017 |access-date=April 5, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| In the series '']'', the immortality of her cells in the lab is cited as the precedent for the character Arteche's "extreme resistance to infections, to injuries, and to cellular degeneration. In other words to aging": that his cells are immortal.<ref>{{citation |title=El Ministerio Del Tiempo episode 11, season 3|publisher=HBO}}</ref> | |||

| In the Netflix original movie '']'' (2020), the case of Henrietta Lacks is cited by one of the villains of the story as an example of unwilling trials giving rise to advances for the greater good.<ref>{{Cite magazine |date=August 13, 2020 |title='Project Power' Is a Secret Lesson About Science's Dark Side |url=https://www.wired.com/story/project-power-science-history/ |first=Emma Grey|last=Ellis|access-date=March 28, 2021 |magazine=Wired |language=en-us}}</ref> | |||

| The ] album '']'' (2012) includes the song "Winter Blues" that contains the lyrics "We could live forever like Henrietta Lacks cells".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://genius.com/Jj-doom-winter-blues-lyrics |title="JJ DOOM - Winter Blues" |publisher=Genius |date=2015 |access-date=January 20, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ] wrote a song about Lacks, entitled "Henrietta," for their 2012 album '']''.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.songfacts.com/facts/yeasayer/henrietta |title=Henrietta by Yeasayer |website=Songfacts.com |access-date=August 9, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist|35em}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| {{Reflist|group=upper-alpha}} | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| {{reflist|30em}} | {{reflist|30em}} | ||

| == |

===Sources=== | ||

| {{refbegin}} | {{refbegin}} | ||

| * Russell Brown |

<!--* {{cite journal |first1=Russell |last1=Brown |first2=James H M |last2=Henderson |year=1983 |title=The Mass Production and Distribution of HeLa Cells at Tuskegee Institute,1953–1955 |work=J Hist Med Allied Sci |volume=38 |number=4 |pages=415–43}}--> | ||

| <!--* {{cite book|first1=Hannah |last1=Landecker |authorlink1=Hannah Landecker |year=2000 |title=Immortality, In Vitro. A History of the HeLa Cell Line}} In {{citebook|last1=Brodwin |first1=Paul E., ed. |title=Biotechnology and Culture. Bodies, Anxieties, Ethics |location=Bloomington/Indianapolism |pages=53–72 |isbn=0-253-21428-9}}--> | |||

| * {{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1986/06/15/books/hela-s-legacy.html|title=Hela's Legacy|author=Harold M. Schmeck Jr.|date=1986-05-15|newspaper=The New York Times}} | |||

| <!--* {{cite book|first1=Hannah |last1=Landecker |year=1999 |title=Between Beneficence and Chattel: The Human Biological in Law and Science |work=Science in Context |pages=203–225}}--> | |||

| * {{cite book|title=A Conspiracy of Cells: One Woman's Immortal Legacy and the Medical Scandal It Caused|author=Michael Gold|date=January 1986|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-88706-099-1}} | |||

| <!--* {{cite book|first1=Hannah |last1=Landecker |year=2007 |title=Culturing Life: How Cells Became Technologies |chapter=], Chapter 4}}--> | |||

| * ] 2000 "Immortality, In Vitro. A History of the HeLa Cell Line". In Brodwin, Paul E., ed.: ''Biotechnology and Culture. Bodies, Anxieties, Ethics''. Bloomington/Indianapolis, 53–72, {{ISBN|0-253-21428-9}} | |||

| <!--* {{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1986/06/15/books/hela-s-legacy.html|title=Hela's Legacy| first1=Harold M. Jr. |last1=Schmeck|date=May 15, 1986|newspaper=The New York Times}}--> | |||

| * Hannah Landecker, 1999, "Between Beneficence and Chattel: The Human Biological in Law and Science," ''Science in Context'', 203–225. | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Skloot|first=Rebecca|author-link=Rebecca Skloot|title=The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks|year=2010|publisher=]|place=New York City|isbn=978-1-4000-5217-2|url=}} | |||

| * Hannah Landecker, 2007, ''Culturing Life: How Cells Became Technologies''. "]" is the title of the fourth chapter. | |||

| <!--*{{cite news |url= http://www.oprah.com/world/Excerpt-From-The-Immortal-Life-of-Henrietta-Lacks_1/3 |title=Excerpt From The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks |first=Rebecca |last=Skloot |work=oprah.com |date=February 2010 |access-date=August 9, 2013}}--> | |||

| * Priscilla Wald, "American Studies and the Politics of Life" American Quarterly 64.2 (June 2012): 185–204 | |||

| * Priscilla Wald |

<!--* {{cite book|first1=Priscilla |last1=Wald |title=Cells, Genes, and Stories: HeLa's Journey from Labs to Literature |work=Genetics and the Unsettled Past: The Collision of Race, DNA and History |editor=Keith Wailoo, Alondra Nelson, and Catherine Lee |publisher=] |year=2012 |pages= 247–65}}--> | ||

| * Priscilla Wald |

<!--* {{cite journal|first1=Priscilla |last1=Wald |title=Science Fiction and Medical Ethics |work=] |date=June 14, 2009 |page=371.9629}}--> | ||

| <!--* {{cite journal|first1=Priscilla |last1=Wald |title=American Studies and the Politics of Life |work=] |volume=64.2 |date=June 2012 |pages=185–204}}--> | |||

| {{refend}} | {{refend}} | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{sisterlinks|d=Q1647793|c=category:Henrietta Lacks|n=no|b=no|v=no|voy=no|m=no|mw=no|species=no|s=no|wikt=no|q=no}} | {{sisterlinks|d=Q1647793|c=category:Henrietta Lacks|n=no|b=no|v=no|voy=no|m=no|mw=no|species=no|s=no|wikt=no|q=no}} | ||

| *], available in UK via ] | |||

| *, a foundation established to, among other things, help provide scholarship funds and health insurance to Henrietta Lacks's family. | *, a foundation established to, among other things, help provide scholarship funds and health insurance to Henrietta Lacks's family. | ||

| * Michael Rogers, , '']'' March 25, 1976 | |||

| * , RadioLab segment featuring Deborah Lacks and audio of Skloot's interviews with her, and original recordings of scenes from the book. | |||

| * , ''Jet Magazine'', April 1, 1976 | |||

| *, February 2010 CBS ''Sunday Morning'' segment featuring the Lacks Family, February 2010 | |||

| * , 2010 RadioLab segment featuring Deborah Lacks and audio of Skloot's interviews with her, and original recordings of scenes from the book. | |||

| * , '']'' 2010 article with timeline of HeLa contributions to science | |||

| * , February 2010 CBS ''Sunday Morning'' segment featuring the Lacks Family, February 2010 | |||

| * E. Fannie Granton and Ronald E. Kisner, , '']'' (Vol. 50, No. 2), April 1, 1976 | |||

| * , ''Jet Magazine'', April 1, 1976 | |||

| * {{Find a Grave|11698761}} | |||

| {{EthicsCases}} | {{EthicsCases}} | ||

| Line 141: | Line 183: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:13, 19 January 2025

African-American woman (1920–1951), source of HeLa immortal cell line "Lacks" redirects here. For other uses, see Lack.

| Henrietta Lacks | |

|---|---|

Lacks c. 1945–1951. Lacks c. 1945–1951. | |

| Born | Loretta Pleasant (1920-08-01)August 1, 1920 Roanoke, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | October 4, 1951(1951-10-04) (aged 31) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Cervical cancer |

| Monuments | Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School; historical marker at Clover, Virginia |

| Occupations | |

| Height | approx. 5 ft (150 cm) |

| Spouse |

David Lacks (m. 1941) |

| Children | 5 |

Henrietta Lacks (born Loretta Pleasant; August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951) was an African-American woman whose cancer cells are the source of the HeLa cell line, the first immortalized human cell line and one of the most important cell lines in medical research. An immortalized cell line reproduces indefinitely under specific conditions, and the HeLa cell line continues to be a source of invaluable medical data to the present day.

Lacks was the unwitting source of these cells from a tumor biopsied during treatment for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1951. These cells were then cultured by George Otto Gey, who created the cell line known as HeLa, which is still used for medical research. As was then the practice, no consent was required to culture the cells obtained from Lacks's treatment. Neither she nor her family were compensated for the extraction or use of the HeLa cells.

Even though some information about the origins of HeLa's immortalized cell lines was known to researchers after 1970, the Lacks family was not made aware of the line's existence until 1975. With knowledge of the cell line's genetic provenance becoming public, its use for medical research and for commercial purposes continues to raise concerns about privacy and patients' rights.

Biography

Early life

Henrietta Lacks was born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920, in Roanoke, Virginia, to Eliza Pleasant (née Lacks) (1886–1924) and John "Johnny" Randall Pleasant (1881–1969). She is remembered as having hazel eyes, a small waist, size 6 shoes, and always wearing red nail polish and a neatly pleated skirt. Her family is uncertain how her name changed from Loretta to Henrietta, but she was nicknamed Hennie. When Lacks was four years old in 1924, her mother died giving birth to her tenth child. Unable to care for the children alone after his wife's death, Lacks's father moved the family to Clover, Virginia, where the children were distributed among relatives. Lacks ended up with her maternal grandfather, Thomas "Tommy" Henry Lacks, in a two-story log cabin that was once the slave quarters on the plantation that had been owned by Henrietta's white great-grandfather and great-uncle. She shared a room with her nine-year-old first cousin and future husband, David "Day" Lacks (1915–2002).

Like most members of her family living in Clover, Lacks worked as a tobacco farmer starting from an early age. She fed the animals, tended the garden, and toiled in the tobacco fields. She attended the designated black school two miles away from the cabin until she had to drop out to help support the family when she was in the sixth grade. When Lacks was 14 years old, she gave birth to a son, Lawrence Lacks (1935–2023). In 1939, her daughter Elsie Lacks (1939–1955) was born. Both children were fathered by Day Lacks. Elsie had epilepsy and cerebral palsy and was described by the family as "different" or "deaf and dumb".

Marriage and family