| Revision as of 18:09, 17 April 2022 view sourceEfekadu (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users961 editsmNo edit summaryTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:41, 19 January 2025 view source KybordK6K (talk | contribs)55 editsNo edit summaryTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (668 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{About|the African ethnic group|the South American ethnic group|Aymara people}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{short description|Semitic-speaking ethnic group native to Ethiopia in the Ethiopian Highlands}} | {{short description|Semitic-speaking ethnic group native to Ethiopia in the Ethiopian Highlands}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2019}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2019}}{{Infobox ethnic group | ||

| | group = Amharas | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| | native_name = {{native name|am|አማራ|italics=off}}<br />ዐምሐራ (]) | |||

| | group = Amharas | |||

| | image = Bahir Dar woman.jpg | |||

| | native_name = {{native name|am|አማራ|italics=off}}<br />ዐምሐራ (]) | |||

| | caption = Amhara woman with a ] clothing in the background | |||

| | population = | | population = | ||

| | image = File:Yekuno_Amlak.jpg | |||

| | caption = ], founder of the ] | |||

| | popplace = | |||

| | region1 = {{flagcountry|Ethiopia}} | | region1 = {{flagcountry|Ethiopia}} | ||

| | pop1 = 19, |

| pop1 = 19,867,817 (2007)<ref name=CSA/> | ||

| | region2 = {{flagcountry|United States}} | | region2 = {{flagcountry|United States}} | ||

| | pop2 = |

| pop2 = 248,199<ref name="United States Census Bureau">{{cite web |url=https://data.census.gov/mdat/#/search?ds=ACSPUMS1Y2022&rv=LANP&wt=PWGTP|title=Languages spoken in American Households, 2020. |publisher= United States Census Bureau}}</ref> | ||

| <https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html>.</ref> | |||

| | region3 = {{flagcountry|Canada}} | | region3 = {{flagcountry|Canada}} | ||

| | pop3 = 30,395<ref>{{Cite web|publisher=Government of Canada|author=2021 Census of Canada|title=Statistics Canada 2021|url=https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810018001=0&SearchText=Canada|access-date=22 June 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | pop3 = 18,020{{efn|name=fn1}}<ref>Statistics Canada, 2011 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-314-XCB2011032</ref><ref>Anon, 2016. 2011 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations | Detailed Mother Tongue (232), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population Excluding Institutional Residents of Canada and Forward Sortation Areas, 2011 Census. Www12.statcan.gc.ca. Available at: <http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/tbt-tt/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=103001&PRID=10&PTYPE=101955&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2011&THEME=90&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=> .</ref><ref>Immigrant languages in Canada. 2016. Immigrant languages in Canada. Available at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-314-x/98-314-x2011003_2-eng.cfm. .</ref> | |||

| | region4 = {{flagcountry|United Kingdom}} | | region4 = {{flagcountry|United Kingdom}} | ||

| | pop4 = 8,620 |

| pop4 = 8,620<ref>pp, 25 (2015) United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.ethnologue.com/country/GB (Accessed: 30 November 2016).</ref> | ||

| | region5 = {{flagcountry| |

| region5 = {{flagcountry|Australia}} | ||

| | pop5 = 4,515<ref>Australian Bureau of Statistics 2014, The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS, 30 November 2016, https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417222156/https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf |date=17 April 2017 }}.</ref> | |||

| | pop5 = Unknown<ref name=Teferra/> | |||

| | region6 = {{flagcountry| |

| region6 = {{flagcountry|Finland}} | ||

| | pop6 = 1,515<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_031.px/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4 |title=Kieli sukupuolen mukaan maakunnittain ja kunnittain 1990 - 2017 |access-date=24 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180626001544/http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_031.px/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4 |archive-date=26 June 2018 }}</ref> | |||

| | pop6 = 4,515{{efn|name=fn1}}<ref>Australian Bureau of Statistics 2014, The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS, 30 November 2016, <https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417222156/https://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/research/people-australia-2013-statistics.pdf |date=17 April 2017 }}>.</ref> | |||

| | region7 = {{flagcountry|Finland}} | |||

| | pop7 = 1,515{{efn|name=fn1}}<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_031.px/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4 |title=Archived copy |access-date=24 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180626001544/http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_031.px/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4 |archive-date=26 June 2018 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| | languages = ] | | languages = ] | ||

| | religions = ] (]) • ] (]) | | religions = ] (]) • ] (]) • ] (])<ref>{{Cite web |date=18 November 2021 |title=All Ethiopian Jews must be brought home to Israel |url=https://www.jpost.com/diaspora/all-ethiopian-jews-must-be-brought-home-to-israel-685409 |access-date=30 May 2022 |website=The Jerusalem Post |language=en-US}}</ref> | ||

| | related = ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • other ] and ]<ref name="Joireman">{{cite book|last=Joireman|first=Sandra F.|title=Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development|year=1997|publisher=Universal-Publishers|isbn=1-58112-000-1|page=1|quote=The Horn of Africa encompasses the countries of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia. These countries share similar peoples, languages, and geographical endowments.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CyeaiaJ0ypAC}}</ref> | |||

| | related = | |||

| | footnotes = | |||

| ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • other ] and ]<ref name="Joireman">{{cite book|last=Joireman|first=Sandra F.|title=Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development|year=1997|publisher=Universal-Publishers|isbn=1581120001|page=1|quote=The Horn of Africa encompasses the countries of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia. These countries share similar peoples, languages, and geographical endowments.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CyeaiaJ0ypAC}}</ref> | |||

| | footnotes = {{notelist}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Amharas''' ({{ |

'''Amharas''' ({{langx|am|አማራ|Āmara}};<ref>Following the ] employed for Amharic geographic names in British and American English.</ref> {{langx|gez|ዐምሐራ|ʾÄməḥära}})<ref name=":0">{{cite book|last1=Zegeye|first1=Abebe|title=Ethiopia in Change|date=15 October 1994|publisher=British Academic Press|page=13|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=caSwQZab5awC&pg=PA13|isbn=978-1-85043-644-7}}</ref> are a ]-speaking ] indigenous to ] in the Horn of Africa, traditionally inhabiting parts of the northwest and central ], not only within the present-day ], but also lands beyond its current administrative borders. According to the 2007 national census, Amharas numbered 19,867,817 individuals, comprising 26.9% of Ethiopia's population, and they are mostly ] (members of the ])<ref name="CSA">{{cite web|title=Table 2.2 Percentage Distribution of Major Ethnic Groups: 2007|page=16|url=http://www.csa.gov.et/pdf/Cen2007_firstdraft.pdf|work=Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results|publisher=United Nations Population Fund|access-date=29 October 2014 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090325050115/http://www.csa.gov.et/pdf/Cen2007_firstdraft.pdf | archive-date=25 March 2009 |author=Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia}}</ref>. | ||

| They are also found within the Ethiopian expatriate community, particularly in ].<ref name="Amharu">United States Census Bureau 2009–2013, Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009–2013, USCB, 30 November 2016, | |||

| They are also found within the Ethiopian expatriate community, particularly in ].<ref name="Amharu"/><ref>{{cite book|last1=Olson|first1=James|title=The Peoples of Africa|date=1996|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|page=27|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MdaAdBC-_S4C&pg=PA27|isbn=9780313279188}}</ref> They speak ], an ] language of the ] branch which serves as one of the five official languages of Ethiopia.<ref name="africanews.com">{{cite news |last1=Shaban |first1=Abdurahman |title=One to five: Ethiopia gets four new federal working languages |url=https://www.africanews.com/2020/03/04/one-to-five-ethiopia-gets-four-new-federal-working-languages// |agency=Africa News}}</ref> As of 2018, Amharic has over 32 million native speakers and 25 million second language speakers.<ref name="Amharic">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/AMH|title=Amharic}}</ref> | |||

| https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Olson|first1=James|title=The Peoples of Africa|date=1996|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|page=27|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MdaAdBC-_S4C&pg=PA27|isbn=978-0-313-27918-8}}</ref> They speak ], an ] language of the ] branch which serves as the main and one of the five official languages of Ethiopia.<ref name="africanews.com">{{cite news |last1=Shaban |first1=Abdurahman |title=One to five: Ethiopia gets four new federal working languages |url=https://www.africanews.com/2020/03/04/one-to-five-ethiopia-gets-four-new-federal-working-languages// |agency=Africa News |access-date=12 April 2021 |archive-date=15 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201215231030/https://www.africanews.com/2020/03/04/one-to-five-ethiopia-gets-four-new-federal-working-languages// |url-status=dead }}</ref> As of 2018, Amharic has over 32 million native speakers and 25 million second language speakers, making it the most widely spoken language in Ethiopia.<ref name="Amharic">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/AMH|title=Amharic}}</ref> | |||

| The Amhara and neighboring groups in Northen Ethiopia and Eritrea refer to themselves as "Habesha" (]) people.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Prunier |first1=Gerard |last2=Ficquet |first2=Eloi |date=2015 |title=Understanding contemporary Ethiopia |location=London |publisher=Hurst & Company |page=39|oclc=810950153 }}</ref><ref name="LevineGE2000">{{cite book|last1=Levine|first1=Donald N.|author-link=Donald N. Levine |title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society|publisher=University of Chicago Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TtmFQejWaaYC&q=%22Abyssinians+proper%2C+the%22&pg=PA19|access-date=28 December 2016|isbn=978-0-226-47561-5|date=2000}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Marvin Lionel Bender|title=Language in Ethiopia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dIkOAAAAYAAJ|year=1976|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-436102-6|page=26}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Paul B.|last=Henze|title=Rebels and Separatists in Ethiopia: Regional Resistance to a Marxist Regime|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PBMOAQAAMAAJ|year=1985|publisher=Rand|isbn=978-0-8330-0696-7|page=8}}</ref><ref>Goitom, M. (2017) "Unconventional Canadians": Second-generation "Habesha" Youth and Belonging in Toronto, Canada. ''Global Social Welfare'' 4(4), 179–190.</ref> | |||

| Historically, the Amhara held significant political position in the ]. They were the origin of the ] and all the emperors of Ethiopia were Amhara with the exception of ] since the restoration of the dynasty in 1270.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gate |first1=Henry Louis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TMZMAgAAQBAJ&dq=all+but+one+of+country+emperors+were+amhara&pg=PA187 |title=Africana the encyclopedia of the african and african american experience |last2=Appiah |first2=Anthony |date=2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |pages=187|isbn=978-0-19-517055-9 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Levine |first=Donald |title=Wax & gold : tradition and innovation in Ethiopian culture. |date=1965 |pages=2}}</ref> | |||

| __TOC__ | |||

| ==Origin== | ==Origin== | ||

| The scribe and historian, Ibn Khaldun, writing in the 13th century, identified an individual named Abu Muhammad Surur al-Fatiki, an 11th-century Mamluk of the Najahid Dynasty that he describes as an exceptional ruler and one who "...belonged to the Abyssinian tribe of Amhara"<ref name=":0" />. This suggests the existence of Amhara as a distinct ethnic identity during that period. | |||

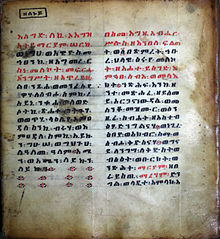

| ] taken from a 15th-century Ethiopian Coptic prayer book]] | |||

| Further records of the Amhara as a people continue to appear dates as early as the 12th century, in the middle of the Zagwe Dynasty, when the Amhara were recorded of being in conflict in the ''land of ]'' in 1128 AD.<ref>Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 81</ref><ref>IL SULTANATO DELLO SCIOA NEL SECOLO XIII, page 10, Enrico Cerulli., 1941</ref> | |||

| A non-contemporary 13th or 14th century ] source from ] traces ] even further back to the mid 9th century AD as a location.<ref>The Life of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos and the Miracles of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos, and the Book of the Riches of Kings. Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge. London 1906.</ref> | A non-contemporary 13th or 14th century ] source from ] traces ] even further back to the mid 9th century AD as a location.<ref>The Life of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos and the Miracles of Takla Haymanot in the Version of Dabra Libanos, and the Book of the Riches of Kings. Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge. London 1906.</ref> | ||

| ===Ethnogenesis=== | ===Ethnogenesis=== | ||

| ] is a South ] language, along with ], ] and others.<ref>{{cite book |last=Meyer |first=Ronny |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SMzgBLT87MkC&dq=amharic+proto+ethio+semitic&pg=PA1178 |title=The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook |date=2011 |publisher=Walter De Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-025158-6 |editor-last=Weninger |editor-first=Stefan |location= |pages=1178–1212 |chapter=Amharic }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Edzard |first=Lutz |title=The Semitic Languages |publisher=Routledge |year=2019 |editor1=John Huehnergard |location=London |pages=202–226 |chapter=Amharic |editor2=Naʽama Pat-El}}</ref><ref name=":Hetzron72">{{Cite book |last=Hetzron |first=Robert |title=Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification |publisher=Manchester University Press |year=1972 |isbn=978-0-7190-1123-8 |page=36 |language=English}}</ref> Some time before the 1st century AD, the North and South branches of Ethio-Semitic diverged.<ref name=":Hetzron72" /><ref name="The Cambridge History of Africa - Google Books">{{cite book |last1=Fage |first1=J.D. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&dq=amhara+semitic+migration&pg=PA128 |title=The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050 |last2=Oliver |first2=Roland Anthony |date=1975 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-20981-6 |location= |page=126}}</ref> Due to the social stratification of the time, the ] ] adopted the South Semitic language and mixed with the Semitic population.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hetzron |first=Robert |title=Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification |publisher=Manchester University Press |year=1972 |isbn=978-0-7190-1123-8 |pages=36, 87–88 |language=English}}</ref><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |last=Appleyard |first=David |title=Amharic: History and dialectology of Amharic |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia Aethopica |volume=1 |page=235}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Butts |first=Aaron Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Lai8CgAAQBAJ&dq=amhara+old+agaw&pg=PA22 |title=Semitic languages in contact |date=2015 |publisher=Brill |isbn= 978-90-04-30015-6|location=Leiden, Boston |pages=18–21 |oclc=1083204409 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Amhara {{!}} Definition, History, & Culture {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Amhara |access-date=2022-04-19 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> Amharic thus developed with a Cushitic ] and a Semitic ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hetzron |first=Robert |title=Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification |publisher=Manchester University Press |year=1972 |isbn=978-0-7190-1123-8 |page=88 |language=English}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Demeke |first=Girma |title=The Origin of Amharic |publisher=The Red Sea Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-56902-379-2 |pages=45–52 |language=English |oclc=824502290}}</ref> The proto-Amhara, or the northernmost South Ethio-Semitic speakers, remained in constant contact with their North Ethio-Semitic neighbors, evidenced by ] analysis and oral traditions.<ref>{{cite book|title=Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, Revolution and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi|date=2015|publisher=C. Hurst & Co.|isbn=978-1-84904-261-1|editor1-last=Prunier|editor1-first=Gérard|location=London|page=19 |editor2-last=Ficquet|editor2-first=Éloi}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Hetzron |first=Robert |title=Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification |publisher=Manchester University Press |year=1972 |isbn=978-0-7190-1123-8 |page=124 |language=English}}</ref> A 7th century southward shift of the center of gravity of the ] and the ensuing integration and Christianization of the proto-Amhara also resulted in a high prevalence of ] sourced lexicon in Amharic.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Demeke |first=Girma |title=The Origin of Amharic |publisher=The Red Sea Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-56902-379-2 |pages=15, 133–138 |language=English |oclc=824502290}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Butts |first=Aaron Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Lai8CgAAQBAJ&dq=amhara+old+agaw&pg=PA22 |title=Semitic languages in contact |date=2015 |publisher=Brill |isbn= 978-90-04-30015-6|location=Leiden, Boston |page=22 |oclc=1083204409 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Tamrat |first=Taddesse |title=Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 |publisher=Clarendon Press |year=1972 |isbn=978-0-19-821671-1 |pages=34–38 |language=English}}</ref> By about the 9th century AD, there was a linguistically distinct ethnic group called the Amhara in the area of ].<ref name="The Cambridge History of Africa - Google Books" /> | |||

| Amharic is a South ] language, along with ], ], and others.<ref>{{cite book |last=Meyer |first=Ronny |url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=SMzgBLT87MkC&pg=PA1178&dq=amharic+proto+ethio+semitic&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwilhZP_1oX0AhUCKewKHf1jAEUQ6AF6BAgGEAI#v=onepage&q=amharic%20proto%20ethio%20semitic&f=false |title=The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook |date=2011 |publisher=Walter De Gruyter |isbn=9783110251586 |editor-last=Weninger |editor-first=Stefan |location= |pages=1178–1212 |chapter=Amharic |author-link=}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Edzard |first=Lutz |title=The Semitic Languages |publisher=Routledge |year=2019 |editor1=John Huehnergard |location=London |pages=202–226 |chapter=Amharic |editor2=Na{{ayin}}ama Pat-El}}</ref><ref name=":Hetzron72">{{Cite book |last=Hetzron |first=Robert |title=Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification |publisher=Manchester University Press |year=1972 |isbn=9780719011238 |pages=36 |language=English}}</ref> Some time before the 1st century AD, the North and South branches of Ethio-Semitic diverged.<ref name=":Hetzron72" /><ref>{{cite book |last1=Fage |first1=J.D. |url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&pg=PA128&dq=amhara+semitic+migration&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwigpKPXrYf3AhVG_qQKHe3IBRw4ChDoAXoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q=amhara%20semitic%20migration&f=false |title=The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050 |last2=Oliver |first2=Roland Anthony |date=1975 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9780521209816 |location= |page=126}}</ref> Due to the social stratification of the time, the ] ] adopted the South Ethio-Semitic language and eventually absorbed the Semitic population.<ref name=":Hetzron72" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Appleyard |first=David |title=Amharic: History and dialectology of Amharic |journal=Encyclopedia Aethopica |volume=1 (A-C) |pages=235}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Butts |first=Aaron Michael |url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=Lai8CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA22&dq=amhara+old+agaw&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjR19qZ-_nzAhXP2aQKHYqoAJE4ChDoAXoECAgQAg#v=onepage&q=amhara%20old%20agaw&f=false |title=Semitic languages in contact |date=2015 |publisher=Brill |isbn= |location=Leiden, Boston |page=18-21 |oclc=1083204409 |author-link=}}</ref> Amharic thus developed with a Cushitic ] and a Semitic ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hetzron |first=Robert |title=Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification |publisher=Manchester University Press |year=1972 |isbn=9780719011238 |pages=22 |language=English}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Demeke |first=Girma |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/824502290 |title=The Origin of Amharic |publisher=The Red Sea Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-56902-379-2 |pages=45-52 |language=English |oclc=824502290}}</ref> A 7th century southward shift of the center of gravity of the ] and subsequent integration and Christianization of the proto-Amhara has resulted in a high prevalence of ] (North Ethio-Semitic) sourced lexicon in Amharic.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Demeke |first=Girma |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/824502290 |title=The Origin of Amharic |publisher=The Red Sea Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-56902-379-2 |pages=15, 133-138 |language=English |oclc=824502290}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Butts |first=Aaron Michael |url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=Lai8CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA22&dq=amhara+old+agaw&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjR19qZ-_nzAhXP2aQKHYqoAJE4ChDoAXoECAgQAg#v=onepage&q=amhara%20old%20agaw&f=false |title=Semitic languages in contact |date=2015 |publisher=Brill |isbn= |location=Leiden, Boston |page=22 |oclc=1083204409 |author-link=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Tamrat |first=Taddesse |title=Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 |publisher=Clarendon Press |year=1972 |isbn=9780198216711 |pages=34-37 |language=English}}</ref> By about the 9th Century AD, there was a linguistically distinct ethnic group called the Amhara in the area between the ] and the valleys of the eastern tributaries of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Fage |first1=J.D. |url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&pg=PA128&dq=amhara+semitic+migration&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwigpKPXrYf3AhVG_qQKHe3IBRw4ChDoAXoECAkQAg#v=onepage&q=amhara%20semitic%20migration&f=false |title=The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050 |last2=Oliver |first2=Roland Anthony |date=1975 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9780521209816 |location= |page=126}}</ref> | |||

| ===Etymology=== | ===Etymology=== | ||

| The origin of the Amhara name is debated. A popular ] traces it to ''amari'' ("pleasing; beautiful; gracious") or ''mehare'' ("gracious"). Another popular etymology claims that it derives from ] {{lang|am|ዐም}} (''ʿam'', "people") and {{lang|am|ሐራ}} (''ḥara'', "free" or "soldier").<ref>Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. "Amhara" in ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica'', p. 230. Harrassowitz Verlag (Wiesbaden), 2003.</ref> | |||

| The present name for the ] and its speakers comes from the medieval ]. The latter enclave was located around ] at the headwaters of the ], and included a slightly larger area than Ethiopia's present-day ].{{citation needed|date=July 2021}} | |||

| The further derivation of the name is debated. Popular etymology traces it to ''amari'' ("pleasing; beautiful; gracious") or ''mehare'' ("gracious"). Another popular etymology claims that it derives from ] {{lang|am|ዐም}} (''ʿam'', "people") and {{lang|am|ሐራ}} (''ḥara'', "free" or "soldier") although this has been dismissed by ].<ref>Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. "Amhara" in ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica'', p. 230. Harrassowitz Verlag (Wiesbaden), 2003.</ref> Getachew Mekonnen Hasen traces it to an ethnic name related to the ]s of ].<ref>Getachew Mekonnen Hasen. ''Wollo, Yager Dibab'', p. 11. Nigd Matemiya Bet (Addis Ababa), 1992.</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{main |

{{main|History of Ethiopia}} | ||

| ] founder of the ]|259x259px]]"Amhara" was historically a medieval province located in the modern province of ] (]), the area which is now known as the ] was composed of several provinces which had little or no autonomy, these provinces included ], ], ], Wollo, ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite book|author=E. A. Wallis Budge|title=A History of Ethiopia: Volume I (Routledge Revivals): Nubia and Abyssinia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KWQtBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA123|year=2014|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-64915-1|pages=123–124}}</ref> | |||

| ], king of Shewa]] | |||

| Evidence of a traceable Christian Aksumite presence in Amhara dates back to at least the 9th century AD, when the ] was erected on ].<ref>Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 36.</ref> Several other sites and monuments indicate the presence of similar Axumite influences in the area, such as the Geta Lion statues, which are located 10 km south of ], and are believed to date back to the 3rd century AD, though they may even date back to pre-Axumite times.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Anfrey |first1=Francis |title=Le lion de Kombolcha et le léopard d'Aksum : des félins rupestres paléochrétiens ? |journal=Annales d Ethiopie |date=January 2011 |volume=26 |page=274 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262198342}}</ref><ref>Briggs, P. and Wildman, K. (2014). Ethiopia. Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, p.357.</ref> | |||

| The province of "Amhara" was historically located in the modern province of ] (]), in the feudal era, the region which is now known as Amhara was composed of several provinces which had little or no autonomy, these provinces included ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book|author=E. A. Wallis Budge|title=A History of Ethiopia: Volume I (Routledge Revivals): Nubia and Abyssinia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KWQtBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA123|year=2014|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-64915-1|pages=123–124}}</ref> The traditional homeland of the Amharas is the central highland plateau of Ethiopia. For over two thousand years, they have inhabited this region. Walled by high mountains and cleaved by great gorges, the ancient realm of ] has been relatively isolated from the rest of the world. | |||

| In 1998, ancient pieces of pottery were found around tombs in Atatiya in Southern Wollo, in ] which is located to the south-east of ], as well as to the north-east of Ancharo (Chiqa Beret). The decorations and symbols which are inscribed on the pottery substantiate the expansion of Aksumite civilization to the south of Angot.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Asfaw |first=Aklilu |date=2000 |title=A Short History of the Argobba |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/ethio_0066-2127_2000_num_16_1_973 |journal=Annales d'Éthiopie |volume=16 |pages=173–183 |doi=10.3406/ethio.2000.973 |via=Persée}}</ref> | |||

| Evidence of a traceable Christian Axumite (]) presence in the Amhara region dates back to at least the 9th century CE, when the ] was erected on ].<ref>Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 36.</ref> Several other sites and monuments indicate the presence of similar Axumite influences in the area, such as the Geta Lion statues, which are located 10 km south of ], and they are believed to date back to the 3rd century CE, or they may even date back to pre-Axumite times.<ref>Briggs, P. and Wildman, K. (2014). Ethiopia. Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, p.357.</ref> | |||

| According to ] "By 800, Axum had almost ceased to exist, and its demographic resources were barely adequate to stop the once tributary pastoralists of the border marches from pillaging the defenseless countryside." With some of the common people the Axumite elite abandoned Axum in favor of central Ethiopia.<ref name="Butzer">{{cite journal |last1=Butzer |first1=Karl W. |title=Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation |journal=American Antiquity |date=1981 |volume=46 |issue=3 |pages=471–495 |doi=10.2307/280596 |jstor=280596 |s2cid=162374800 |issn=0002-7316}}</ref> Christian families gradually migrated southward into Amhara and northern Shewa. Population movement from the old provinces in the north into more fertile areas in the south seems to have been connected to the southward shift of the kingdom.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Fage |first1=J. D. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&dq=ya'q%C5%ABbi+almas%C3%AD%C5%ABdi's&pg=PA101 |title=The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 B.C. to A.D. 1050 |last2=Oliver |first2=Roland Anthony |date=1975 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-20981-6 |page=101 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In 1998, pieces of pottery were found around tombs in Atatiya in Southern Wollo, in ] which is located to the south-east of ], as well as to the north-east of Ancharo (Chiqa Beret). The decorations and symbols which are inscribed on the pottery prove that the Aksumite civilization had extended its reach to the Southern Amhara area which is located beyond ].<ref>Aklilu Asfaw, Report to the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1997.</ref> | |||

| The Christianization of Amhara is believed to have begun somewhere during the Aksumite period. The political importance of Amhara further increased after the fall of ], which marked the shift of the political center of the Christian Ethiopian state from Aksum in the north to the ] region of ] further inland.<ref>{{cite book |ref=none |last=Demeke |first=Girma A. |date=2014 |title=The Origin of Amharic |publisher=The Red Sea Press |location= |page=53 |isbn=978-1-56902-379-2 |issn= |oclc=824502290 }}</ref><ref>"Amhara" in Siegbert Uhlig, ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C'' (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003), p. 168.</ref> | |||

| The Amhara nobles supported the ] prince ] in his power struggle against his brothers which led him to make ] ''Lessana Negus'' as well as fill the Amhara nobles in the top positions of his Kingdom.<ref>Mohammad Hassan, The Oromo of Ethiopia, pp.3</ref> | |||

| The Amhara nobles supported the ] prince ] in his power struggle against his brothers which led him to make Amharic ''Lessana Negus'' (lit. "language of the king") as well as fill the Amhara nobles in the top positions of his Kingdom.<ref>Mohammad Hassan, The Oromo of Ethiopia, pp.3</ref><ref>{{cite book |ref=none |last=Demeke |first=Girma A. |date=2014 |title=The Origin of Amharic |publisher=The Red Sea Press |location= |page=53 |isbn=978-1-56902-379-2 |issn= |oclc=824502290 }}</ref> | |||

| === Solomonic Dynasty === | === Solomonic Dynasty === | ||

| {{main|Ethiopian Empire|Solomonic Dynasty}} | |||

| ], a prince from ] claimed descent from ],<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Pankhurst |first1=Richard |title=Fear God, Honor the King: The Use of Biblical Allusions in Ethiopian Historical Literature, Part I |journal=Northeast African Studies |date=1986 |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=11–30 |jstor=43660191}}</ref> and established the Solomonic Dynasty in 1270 AD.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Zagwe-dynasty#ref184296|entry=Zagwe dynasty |encyclopedia=Britannica |title=Zagwe dynasty | Solomonic dynasty, Lalibela, Axumite Empire | Britannica }}</ref> The early rulers of the ] may have been referred to as the "kings of ''Amhara''", due to the origin of their founder, ], and therefore, their followers were called "Amhara" and brought this new name with them when they conquered new lands. Characterized by a Christian feudal culture, and by the adoption of ], which from became the '']''. This population of a rather small province became the dominant group in the empire.<ref>"Amhara" in Siegbert Uhlig, ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C'' (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003), p. 230.</ref> | |||

| ], Emperor of Ethiopia, by ]|248x248px]] | |||

| Around this time, Medieval Arab historians state that Christian Ethiopia was under the sovereignty of "the Lord of Amhara" which confirms that the new ] appears to be stock of the ] in the eyes of the contemporary. The Egyptian historian ] in 704 ] (1304-1305 AD) labelled the Emperor of ] as ''al-Malik al-Amhari'' or "the Amhara King".<ref name="Istituto Per L'Oriente">{{cite book |last1=Cerulli |first1=Enrico |title=Islam: Yesterday and Today translated by Emran Waber |publisher=Istituto Per L'Oriente |page=315 |url=https://drive.google.com/file/d/1g-LkxaXWZopjLCFEuWm8wnly2lh4WvFp/view}}</ref> In 1436 ] wrote a passage about the death of Emperor ] referring to him as the Lord of Amhara, "The Hatse, the Abyssinian king, the infidel and the Lord of the Amhara in Abyssinia died (in this year). His estates were much enlarged after wars waged and led by him against Sultan ], the Lord of the Jabarta."<ref name="Istituto Per L'Oriente" /> | |||

| The cultural contact and interaction between the Amhara and the indigenous ] accelerated after the 14th century. As the Agaw adopted the ] and converted to ], they increasingly succumbed to Amhara acculturation. Other | |||

| ], a prince from ] claimed descent from ],<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Pankhurst |first1=Richard |title=Fear God, Honor the King: The Use of Biblical Allusions in Ethiopian Historical Literature, Part I |journal=Northeast African Studies |date=1986 |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=11–30 |jstor=43660191 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43660191 |access-date=12 June 2021}}</ref> and established the Solomonic Dynasty in 1270 AD.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Zagwe-dynasty#ref184296|title = Zagwe dynasty | Ethiopian history}}</ref> Yekuno's rule was legitimatized by the Ethiopian Church, after he defeated the last ruler of the ] at the ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Ethiopia/The-Zagwe-and-Solomonic-dynasties#ref419497|title = Ethiopia - the Zagwe and Solomonic dynasties}}</ref> The ] governed the Ethiopian Empire for many centuries from 1270 AD onwards up until the deposing of ] in 1974. The Amhara continuously ruled and formed the political core of the Ethiopian Empire, establishing several medieval royal sites and capitals such as ], ], Barara (located on ], in modern-day ]),<ref>Pankhurst, R. and Breternitz, H. (2009). Barbara, the Royal City of 15th and Early 16th Century (Ethiopia). Medieval and Other Early Settlements Between Wechecha Range and Mt Yerer: Results from a Recent Survey. Annales d'Ethiopie, 24(1), p.210.</ref> ], and ]. | |||

| South Semitic speakers like the ] and ] in Shewa also began to adopt Amharic and assimilate into Amhara society. By the end of the 16th century, the populations of ], ] and ] were almost completely made up of Christian Amharic speakers.<ref name="Siegbert Uhlig 2003 p. 231">"Amhara" in Siegbert Uhlig, ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C'' (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003), p. 231.</ref> | |||

| ], ] (Emperor) of Ethiopia and a member of the ]]] | |||

| Despite every work on Ethiopia stressing the political dominance of the Amhara people in the history of the Ethiopian Christian empire. In both Christian and Muslim written traditions up to the 19th century, and in the Ethiopian chronicles of the 14th to 18th centuries, the term "Amhara" is a region, not an ethnonym. In pre-17th century Ethiopia, Amhara was described as the heartland of the Empire and the cradle of the monarchy. Medieval European maps suggest that within the ], Amhara had a higher position as a "kingdom" among provinces. The Italian (]) cartographer ], notes a ''Regno Hamara'' or "Kingdom of Amhara" in his famous '']'' in 1460. Important information on Amhara is provided in the ''Historia Aethiopica'' by ], the data of which came from ], himself a native of Amhara. On the map of ''Historia Aethiopica'', Amhara is situated between the ] to the west, the ] in the north, the ] to the east and the ] to the south. The province consisted of much of ] and northern ], and encompassed the region of ] and the famous ].<ref name="Siegbert Uhlig 2003 p. 231"/> | |||

| In the early 15th century, the Emperors sought to make diplomatic contact with European kingdoms for the first time since Aksumite times. A letter from King ] to the Emperor of Abyssinia survives.<ref>Ian Mortimer, ''The Fears of Henry IV'' (2007), p.111 {{ISBN|1-84413-529-2}}</ref> In 1428, Emperor ] sent two emissaries to ], who sent return emissaries who failed to complete the return trip.<ref>Beshah, pp. 13–4.</ref> | |||

| ] from the German-born missionary, Johann Martin Flad, who was one of the European prisoners at Magdala]] | |||

| The Amhara monarchs moved continuously from region to region living in ]s, showing a particular preference for the southernly regions of ], ] and ] until the political upheavals of the 16th century, after which the province of ] became home for the city of ], royal capital for the Ethiopian polity from the 1630s to the mid-19th century. Within the broader territory of Amharic speakers, certain regions developed into autonomous political centers. To the south, beyond Lake Tana, the province of ] developed a dynasty of rulers and became a powerful kingdom within the ]. The district of ] in ] became the center for the development of a political dynasty culminating in King ], Emperor ] and Emperor ].<ref name="Siegbert Uhlig 2003 p. 232">"Amhara" in Siegbert Uhlig, ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C'' (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003), p. 232.</ref> | |||

| Through their control of the political center of Ethiopian society and via assimilation, conquests, and intermarriages, the Amhara have spread their language and many customs well beyond the borders of their primary homeland in ]. This expansion served as a cohesive force, binding together the disparate elements of the larger Ethiopian polity. This cohesion proved crucial for the Ethiopian state as it engaged in the process of modern nation-building in the 19th century, thereby preserving its independence against potential threats from European colonial powers. Additionally, it facilitated various modernizing initiatives, including the abolition of the slave trade, the implementation of new communication and transportation systems, the establishment of schools and hospitals, and the creation of modern government institutions.<ref name="Siegbert Uhlig 2003 p. 232"/> | |||

| The first continuous relationship with a European country began in 1508 with Portugal under Emperor ], who had just inherited the throne from his father.<ref>Beshah, p. 25.</ref> This proved to be an important development, for when the Empire was subjected to the attacks of the ] and its leader ], Portugal assisted the Ethiopian emperor in the ] by sending weapons and 400 men, who helped his son ] defeat Ahmad and re-establish his rule.<ref>Beshah, pp. 45–52.</ref> | |||

| ], '']'']] | |||

| The Amhara contributed numerous rulers over the centuries, including ],<ref name="Tronvoll">Kjetil Tronvoll, ''Ethiopia, a new start?'', (Minority Rights Group: 2000)</ref> whose father was both paternally and maternally Amhara of Solomonic descent.<ref name="Woodward">Peter Woodward, ''Conflict and peace in the Horn of Africa: federalism and its alternatives'', (Dartmouth Pub. Co.: 1994), p. 29.</ref> | |||

| == |

== Social stratification == | ||

| {{ |

{{Further|Caste systems in Africa#Amhara people}} | ||

| ]."]]Within traditional Amharic society and that of other local ]-speaking populations, there were four basic strata. According to the Donald Levine, these consisted of high-ranking clans, low-ranking clans, caste groups (artisans), and slaves.<ref name="Levine2014p56" /><ref>{{cite book|first=Allan|last=Hoben|editor= Arthur Tuden and Leonard Plotnicov|title =Social stratification in Africa|url =https://books.google.com/books?id=KtwDAQAAIAAJ| year=1970| publisher=New York: The Free Press| isbn=978-0-02-932780-7| pages=210–211, 187–221|chapter=Social Stratification in Traditional Amhara Society}}</ref> Slaves or rather servants were at the bottom of the hierarchy, and were primarily drawn from the pagan ] ] and ] peoples.<ref>{{cite book |last=Keller |first=Edmond J |date=1991 |title=Revolutionary Ethiopia: from empire to people's republic |location=Bloomington |publisher=Indiana University Press |page=160 |isbn=|oclc=1036800537 }} | |||

| <!-- social stratification in Amhara society and related groups is complex; please see the archives and talk page for past discussions before adding or removing any content, as well as stick to reliable sources policy of[REDACTED] (WP:RS) --> | |||

| Within traditional Amharic society and that of other local ]-speaking populations, there were four basic strata. According to the Donald Levine, these consisted of high-ranking clans, low-ranking clans, caste groups (artisans), and slaves.<ref name="Levine2014p56"/><ref>{{cite book|first=Allan|last=Hoben|editor= Arthur Tuden and Leonard Plotnicov|title =Social stratification in Africa|url =https://books.google.com/books?id=KtwDAQAAIAAJ| year=1970| publisher=New York: The Free Press| isbn=978-0029327807| pages=210–211, 187–221|chapter=Social Stratification in Traditional Amhara Society}}</ref> Slaves were at the bottom of the hierarchy, and were primarily drawn from the pagan ] ] and ] peoples.<ref>{{cite book |last=Keller |first=Edmond J |author-link= |date=1991 |title=Revolutionary Ethiopia : from empire to people's republic |url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/revolutionary-ethiopia-from-empire-to-peoples-republic/oclc/1036800537|location=Bloomington |publisher=Indiana University Press |page=160 |isbn=|oclc=1036800537 }} | |||

| </ref> | </ref> | ||

| Also known as the ''barya'' (meaning "slave" in Amharic), they were captured during slave raids in Ethiopia's southern hinterland. War captives were another source of slaves, but the perception, treatment and duties of these prisoners was markedly different.<ref>{{cite book|last=Abir|first=Mordechai|title=Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769–1855|year=1968|publisher=Praeger|pages=57–60|isbn= |

Also known as the ''barya'' (meaning "slave" in Amharic), they were captured during slave raids in Ethiopia's southern hinterland. War captives were another source of slaves, but the perception, treatment and duties of these prisoners was markedly different.<ref>{{cite book|last=Abir|first=Mordechai|title=Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769–1855|year=1968|publisher=Praeger|pages=57–60|isbn=978-0-582-64517-2|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qo1yAAAAMAAJ|quote=There was a clear distinction between 'red' and 'black' slaves, Hamitic and negroid respectively; the ''Shanqalla'' (negroids) were far cheaper as they were destined mostly for hard work around the house and in the field... While in the houses of the brokers, the slaves were on the whole well treated.}}</ref> According to Levine, the widespread slavery in Greater Ethiopia formally ended in the 1930s, but former slaves, their offspring, and de facto slaves continued to hold similar positions in the social hierarchy.<ref name="Levine56a">{{cite book|first=Donald N.|last=Levine|title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NZHeBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA56|year=2014|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-22967-6|pages=56, 175|quote=}}</ref> | ||

| The separate ] of people ranked higher than slaves was based on the following concepts: (1) endogamy, (2) hierarchical status, (3) restraints on commensality, (4) pollution concepts, (5) traditional occupation, and (6) inherited caste membership.<ref name="Levine2014p56">{{cite book|first=Donald N.|last=Levine|title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NZHeBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA56 |year=2014| publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-22967-6|pages=56–57}}</ref><ref>Eike Haberland (1979), "Special Castes in Ethiopia", in ''Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies'', Editor: Robert Hess, University of Illinois Press, {{oclc| 7277897}}, pp. 129–132 (also see pp. 134–135, 145–147);<br />Amnon Orent (1979), "From the Hoe to the Plow", in ''Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies'', Editor: Robert Hess, University of Illinois Press, {{oclc| 7277897}}, p. 188, Quote: "the ''Mano'', who are potters and leather craftsmen and considered 'unclean' in the usual northern or Amhara understanding of caste distinction; and the ''Manjo'', the traditional hunters and eaters of 'unclean' foods – hippopotamus, monkey and crocodile."</ref> Scholars accept that there has been a rigid, endogamous and occupationally closed social stratification among the Amharas and other Afro-Asiatic-speaking Ethiopian ethnic groups. Some label it as an economically closed, endogamous class system with occupational minorities,<ref>{{cite book|first=Teshale|last=Tibebu|title=The Making of Modern Ethiopia: 1896–1974|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DeD4gruvuNEC&pg=PA67|year=1995|publisher=The Red Sea Press|isbn=978-1-56902-001-2|pages=67–70}}, Quote: "Interestingly enough, while slaves and ex-slaves could 'integrate' into the larger society with relative ease, this was virtually impossible for the occupational minorities ('castes') up until very recently, in a good many cases to this day."</ref><ref>Christopher R. Hallpike (2012, Original: 1968), "The status of craftsmen among the Konso of south-west Ethiopia", ''Africa'', Volume 38, Number 3, Cambridge University Press, pp. 258, 259–267, Quote: "Weavers tend to be the least and tanners the most frequently despised. In many cases such groups are said to have a different, more negroid appearance than their superiors. There are some instances where these groups have a religious basis, as with the Moslems and Falashas in Amhara areas. We frequently find that the despised classes are forbidden to own land, or have anything to do with agricultural activities, or with cattle. Commensality and marriage with their superiors seem also to be generally forbidden them."</ref> whereas others such as David Todd assert that this system can be unequivocally labelled as caste-based.<ref>{{cite journal | last=Todd | first=David M. | title=Caste in Africa? | journal=Africa | publisher=Cambridge University Press | volume=47 | issue=4 | year=1977 | pages=398–412 | doi=10.2307/1158345 | jstor=1158345 | s2cid=144428371 }}<br />Dave Todd (1978), "The origins of outcastes in Ethiopia: reflections on an evolutionary theory", ''Abbay'', Volume 9, pp. 145–158</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Donald N.|last=Levine|title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NZHeBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA56 |year=2014| publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-22967-6|page=56}}, Quote: "As Herbert Lewis has observed, if the term caste can be used for any social formation outside of the Indian context, it can be applied as appropriately to those Ethiopian groups otherwise known as 'submerged classes', 'pariah groups' and 'outcastes' as to any Indian case.";<br />{{cite journal | last=Lewis | first=Herbert S. | title=Historical problems in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa | journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences | publisher=Wiley-Blackwell | volume=96 | issue=2 | year=2006 | pages=504–511 | doi=10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50145.x | s2cid=83677517 }}, Quote (p. 509): "In virtually every Cushitic group there are endogamous castes based on occupational specialization (such caste groups are also found, to some extent, among the Ethiopian Semites).".</ref><ref>{{cite book| last1=Finneran | first1=Niall |title=The Archaeology of Ethiopia| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MNGIzz1VJH0C&pg=PA14 |year=2007|location=London| publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-75552-1| pages=14–15}}, Quote: "Ethiopia has, until fairly recently, been a rigid feudal society with finely grained perceptions of class and caste".</ref> | The separate ] of people ranked higher than slaves was based on the following concepts: (1) endogamy, (2) hierarchical status, (3) restraints on commensality, (4) pollution concepts, (5) traditional occupation, and (6) inherited caste membership.<ref name="Levine2014p56">{{cite book|first=Donald N.|last=Levine|title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NZHeBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA56 |year=2014| publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-22967-6|pages=56–57}}</ref><ref>Eike Haberland (1979), "Special Castes in Ethiopia", in ''Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies'', Editor: Robert Hess, University of Illinois Press, {{oclc| 7277897}}, pp. 129–132 (also see pp. 134–135, 145–147);<br />Amnon Orent (1979), "From the Hoe to the Plow", in ''Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies'', Editor: Robert Hess, University of Illinois Press, {{oclc| 7277897}}, p. 188, Quote: "the ''Mano'', who are potters and leather craftsmen and considered 'unclean' in the usual northern or Amhara understanding of caste distinction; and the ''Manjo'', the traditional hunters and eaters of 'unclean' foods – hippopotamus, monkey and crocodile."</ref> Scholars accept that there has been a rigid, endogamous and occupationally closed social stratification among the Amharas and other Afro-Asiatic-speaking Ethiopian ethnic groups. Some label it as an economically closed, endogamous class system with occupational minorities,<ref>{{cite book|first=Teshale|last=Tibebu|title=The Making of Modern Ethiopia: 1896–1974|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DeD4gruvuNEC&pg=PA67|year=1995|publisher=The Red Sea Press|isbn=978-1-56902-001-2|pages=67–70}}, Quote: "Interestingly enough, while slaves and ex-slaves could 'integrate' into the larger society with relative ease, this was virtually impossible for the occupational minorities ('castes') up until very recently, in a good many cases to this day."</ref><ref>Christopher R. Hallpike (2012, Original: 1968), "The status of craftsmen among the Konso of south-west Ethiopia", ''Africa'', Volume 38, Number 3, Cambridge University Press, pp. 258, 259–267, Quote: "Weavers tend to be the least and tanners the most frequently despised. In many cases such groups are said to have a different, more negroid appearance than their superiors. There are some instances where these groups have a religious basis, as with the Moslems and Falashas in Amhara areas. We frequently find that the despised classes are forbidden to own land, or have anything to do with agricultural activities, or with cattle. Commensality and marriage with their superiors seem also to be generally forbidden them."</ref> whereas others such as David Todd assert that this system can be unequivocally labelled as caste-based.<ref>{{cite journal | last=Todd | first=David M. | title=Caste in Africa? | journal=Africa | publisher=Cambridge University Press | volume=47 | issue=4 | year=1977 | pages=398–412 | doi=10.2307/1158345 | jstor=1158345 | s2cid=144428371 }}<br />Dave Todd (1978), "The origins of outcastes in Ethiopia: reflections on an evolutionary theory", ''Abbay'', Volume 9, pp. 145–158</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Donald N.|last=Levine|title=Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NZHeBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA56 |year=2014| publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-22967-6|page=56}}, Quote: "As Herbert Lewis has observed, if the term caste can be used for any social formation outside of the Indian context, it can be applied as appropriately to those Ethiopian groups otherwise known as 'submerged classes', 'pariah groups' and 'outcastes' as to any Indian case.";<br />{{cite journal | last=Lewis | first=Herbert S. | title=Historical problems in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa | journal=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences | publisher=Wiley-Blackwell | volume=96 | issue=2 | year=2006 | pages=504–511 | doi=10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50145.x | s2cid=83677517 }}, Quote (p. 509): "In virtually every Cushitic group there are endogamous castes based on occupational specialization (such caste groups are also found, to some extent, among the Ethiopian Semites).".</ref><ref>{{cite book| last1=Finneran | first1=Niall |title=The Archaeology of Ethiopia| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MNGIzz1VJH0C&pg=PA14 |year=2007|location=London| publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-75552-1| pages=14–15}}, Quote: "Ethiopia has, until fairly recently, been a rigid feudal society with finely grained perceptions of class and caste".</ref> | ||

| Line 88: | Line 92: | ||

| ==Language== | ==Language== | ||

| {{main|Amharic}} | {{main|Amharic}} | ||

| The Amhara speak |

The Amhara speak "''Amharic''" ("''Amarigna''", "''Amarinya''") as their ]. Its native speakers account for 29.3% of the Ethiopian population.<ref>Central Statistical Agency. 2010. Population and Housing Census 2007 Report, National. Available at: http://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/catalog/3583/download/50086. .</ref> It belongs to the ] branch of the ] language family, and is the largest member of the ] group.<ref name="Ethnamh">{{cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=amh |title=Amharic language |publisher=Ethnologue |date=19 February 1999}}</ref> As of 2018 it had more than 57 million speakers worldwide (32,345,260 native speakers plus 25,100,000 second language speakers),<ref name="Amharic"/> making it the most commonly-spoken language in Ethiopia in terms of first- and second-language speakers, and the second most spoken Semitic language after ]. | ||

| Most of the Ethiopian Jewish communities in Ethiopia and Israel speak Amharic.<ref name=Teferra>{{cite book|first=Anbessa|last=Teferra|chapter=Hebraized Amharic in Israel|editor1-first=Benjamin|editor1-last=Hary|editor2-first=Sarah|editor2-last=Bunin Benor|title=Languages in Jewish Communities, Past and Present|location=Berlin|publisher=Walter De Gruyter|isbn= |

Most of the Ethiopian Jewish communities in Ethiopia and Israel speak Amharic.<ref name=Teferra>{{cite book|first=Anbessa|last=Teferra|chapter=Hebraized Amharic in Israel|editor1-first=Benjamin|editor1-last=Hary|editor2-first=Sarah|editor2-last=Bunin Benor|title=Languages in Jewish Communities, Past and Present|location=Berlin|publisher=Walter De Gruyter|isbn=978-1-5015-1298-8|year=2018|pages=489–519}}</ref> Many followers of the ] movement learn Amharic as a second language, as they consider it to be a sacred language.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140201121031/http://www.reggae.be/en/magazine/interviews/The_Abyssinians_Bernard_Collins_Abyssinians_music_is_creeping_music_and_we_were_a_creeping_band_ |date=1 February 2014 }}. Published 4 November 2011 by Jah Rebel. Retrieved 4 May 2013.</ref> | ||

| Amharic is the working language of the federal authorities of the Ethiopian government, and one of the five official languages of Ethiopia. It was for some time also the sole language of primary school instruction, but has been replaced in many areas by regional languages such as ] and ]. Nevertheless, Amharic is still widely used as the working language of ], ], ] and ].<ref>Danver, Steven Laurence. Native Peoples of the World. 1st ed. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, an imprint of M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2013. Print.</ref> The Amharic language is transcribed using a script (''Fidal'') which is slightly modified from the Ethiopic or ], an ]. | Amharic is the working language of the federal authorities of the Ethiopian government, and one of the five official languages of Ethiopia. It was for some time also the sole language of primary school instruction, but has been replaced in many areas by regional languages such as ] and ]. Nevertheless, Amharic is still widely used as the working language of ], ], ] and ].<ref>Danver, Steven Laurence. Native Peoples of the World. 1st ed. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, an imprint of M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2013. Print.</ref> The Amharic language is transcribed using a script (''Fidal'') which is slightly modified from the Ethiopic or ], an ]. | ||

| Line 96: | Line 100: | ||

| ==Religion== | ==Religion== | ||

| ]'' – the ] for the ].]] | ]'' – the ] for the ].]] | ||

| For centuries, the predominant ] of the Amhara has been ], with the ] playing a central role in the ]. According to the 2007 census, 82.5% of the population of the ] was Ethiopian Orthodox; 17.2% of it was ], 0.2% of it was ] (see ]) and 0.5% of it was ] (see ]).<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.ethiopar.net/type/English/basinfo/infoamra.htm | title=FDRE States: Basic Information – Amhara | at= Population | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110524213939/http://www.ethiopar.net/type/English/basinfo/infoamra.htm | archive-date=24 May 2011 | access-date=26 March 2006 }}</ref> | For centuries, the predominant ] of the Amhara has been ], with the ] playing a central role in the ]. According to the 2007 census, 82.5% of the population of the ] was Ethiopian Orthodox; 17.2% of it was ], 0.2% of it was ] (see ]) and 0.5% of it was ] (see ]).<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.ethiopar.net/type/English/basinfo/infoamra.htm | title=FDRE States: Basic Information – Amhara | at= Population | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110524213939/http://www.ethiopar.net/type/English/basinfo/infoamra.htm | archive-date=24 May 2011 | access-date=26 March 2006 }}</ref> | ||

| The Ethiopian Orthodox Church maintains close links with the ]. Easter and ] are the most important celebrations, marked with services, feasting and dancing. There are also many feast days throughout the year, when only vegetables or fish may be eaten. | The Ethiopian Orthodox Church maintains close links with the ]. Easter and ] are the most important celebrations, marked with services, feasting and dancing. There are also many feast days throughout the year, when only vegetables or fish may be eaten. | ||

| Marriages are often ], with men marrying in their late teens or early twenties.<ref name=AHolocaust>{{cite web | url=http://www.africanmarriage.info/ | title=African Marriage ritual | access-date=9 February 2011 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170507210952/http://www.africanmarriage.info/ | archive-date=7 May 2017 |

Marriages are often ], with men marrying in their late teens or early twenties.<ref name=AHolocaust>{{cite web | url=http://www.africanmarriage.info/ | title=African Marriage ritual | access-date=9 February 2011 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170507210952/http://www.africanmarriage.info/ | archive-date=7 May 2017 }}</ref> Traditionally, girls were married as young as 14, but in the 20th century, the minimum age was raised to 18, and this was enforced by the Imperial government. After a church wedding, divorce is frowned upon.<ref name="AHolocaust"/> Each family hosts a separate wedding feast after the wedding. | ||

| Upon childbirth, a priest will visit the family to bless the infant. The mother and child remain in the house for 40 days after birth for physical and emotional strength. The infant will be taken to the church for ] at 40 days (for boys) or 80 days (for girls).<ref>{{cite book|title=The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East, Part 2, Volume 23|date=1967|publisher=Greystone Press|page=300|url=https:// |

Upon childbirth, a priest will visit the family to bless the infant. The mother and child remain in the house for 40 days after birth for physical and emotional strength. The infant will be taken to the church for ] at 40 days (for boys) or 80 days (for girls).<ref>{{cite book|title=The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East, Part 2, Volume 23|date=1967|publisher=Greystone Press|page=300|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lb5BAAAAIAAJ|access-date=17 February 2017}}</ref> | ||

| ==Culture== | ==Culture== | ||

| ] taken from a 15th-century Ethiopian Coptic prayer book]] | |||

| === Literature === | === Literature === | ||

| {{Main|List of Amharic writers}} | {{Main|List of Amharic writers}} | ||

| Surviving Amharic literary works dates back to the 14th century, when songs and poems were composed.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Amharic-language|title = Amharic language}}</ref> In the 17th century ] became the first African language to be translated into ]<ref>Ludolf, Hiob. 1682. A New History of Ethiopia. Being a Full and Accurate Description of the Kingdom of Abyssinia, Vulgarly, Though Erroneously Called the Empire of Prester John. Translated by J. P. Gent. London: Samuel Smith Booksellers.</ref> when Ethiopian priest and lexicographer ] (1595–1658) in 1652 AD made a European voyage to ] in ]. Gorgoryos along with his colleague and friend ] co-authored the earliest grammar book of the Amharic language, an Amharic-Latin dictionary |

Surviving Amharic literary works dates back to the 14th century, when songs and poems were composed.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Amharic-language|title = Amharic language| date=7 March 2024 }}</ref> In the 17th century ] became the first African language to be translated into ]<ref>Ludolf, Hiob. 1682. A New History of Ethiopia. Being a Full and Accurate Description of the Kingdom of Abyssinia, Vulgarly, Though Erroneously Called the Empire of Prester John. Translated by J. P. Gent. London: Samuel Smith Booksellers.</ref> when Ethiopian priest and lexicographer ] (1595–1658) in 1652 AD made a European voyage to ] in ]. Gorgoryos along with his colleague and friend ] co-authored the earliest grammar book of the Amharic language, an Amharic-Latin dictionary, as well as contributing to Ludolf's book "A History of Ethiopia".<ref>Uhlig, Siegbert. 2005. "Gorgoryos." In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha: Vol. 2, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, 855–856. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RwHtFaHBbtoC&q=abba+gregory%27s+thuringia&pg=PA934|title = Lexicon Grammaticorum: A bio-bibliographical companion to the history of linguistics|isbn = 978-3-484-97112-7|last1 = Stammerjohann|first1 = Harro|date = 2 June 2009| publisher=Walter de Gruyter }}</ref> | ||

| Modern literature in Amharic hoewever started two centuries later than in Europe, with the Amharic fiction ] ''Ləbb Wälläd Tarik'', published in Rome in 1908, widely considered the first novel in Amharic, by ].<ref>Admassu, Yonas. 2003. "Afäwarq Gäbrä Iyäsus." In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C: Vol. 1, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, 122–124. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.</ref> Since then countless of literature in Amharic has been published and many modern day writers in Amharic translate their work also in English for commercial considerations.<ref>{{Cite thesis|url=http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/1286|title = The Origin and Development Amharic Literatuhe|date = May 1981|publisher = Addis Ababa University|type = Thesis|last1 = Aregahegne|first1 = Assefa}}</ref> | |||

| Modern literature in Amharic however, started two centuries later than in Europe, with the Amharic fiction ] ''Ləbb Wälläd Tarik'', published in Rome in 1908, widely considered the first novel in Amharic, by ].<ref>Admassu, Yonas. 2003. "Afäwarq Gäbrä Iyäsus." In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C: Vol. 1, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, 122–124. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.</ref> Amhara intellectual ] pioneered African and Ethiopian theatre when he authored ], Africa's first scripted play.<ref>{{cite book |last=Plastow |first=Jane |date=2010 |title=African Theatre Histories 1850-1950 |chapter=The First African Play: Fabula Yawreoch Commedia & its influence on the development of Ethiopian Theatre |publisher=Boydell & Brewer |location= |pages=138–150 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/histories-18501950/first-african-play-fabula-yawreoch-commedia-its-influence-on-the-development-of-ethiopian-theatre/77ED57CEA4F813DC83893496DAB7B5B9 |access-date= |isbn=9781846159176 |issn= |oclc= }}</ref> Since then countless literature in Amharic has been published and many modern-day writers in Amharic translate their work into English for commercial reasons.<ref>{{Cite thesis|url=http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/1286|title = The Origin and Development Amharic Literatuhe|date = May 1981|publisher = Addis Ababa University|type = Thesis|last1 = Aregahegne|first1 = Assefa}}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:right; margin-right:50px;" | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| |- | |||

| <gallery mode="nolines"> | |||

| ! align=center |]<br /><small>(1595-1658)</small> | |||

| File:Aba Gorgorios, 1681.jpg|]<small> (1595-1658)</small> | |||

| File:Afevork Ghevre Jesus.jpeg|]<small> (1868-1947)</small> | |||

| File:Heruy-Wolde-Selassie-1459998290.jpg|]<small> (1878-1938)</small> | |||

| File:Tekle Hawariat as a young adult.jpg|]<small> (1884-1977)</small> | |||

| File:Dr Kebede Mikael.jpg|]<small> (1916-1998)</small> | |||

| File:Getatchew Haile.JPG|]<small> (1931-2021)</small> | |||

| File:Tsegaye Gabre-Medhin 2.jpg|]<small> (1936-2006)</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| File:Asfa-Wossen Asserate - 4718.jpg|]<small> (1948–present)</small> | |||

| | align=left | ] || align="left" | ] || align="left" | ] || align="left" | ]|| align="left" | ]|| align="left" | ]|| align="left" | ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| |} | |||

| === Music === | === Music === | ||

| {{Main|List of musicians using Amharic vocals|Music of Ethiopia}} | |||

| {{Main|List of musicians using Amharic vocals}} | |||

| Up until the mid 20th century, Amharic music consisted mainly of religious and secular folk songs and dances.<ref name=Grove355>Shelemay, pp. 355–356</ref> | Up until the mid 20th century, Amharic music consisted mainly of religious and secular folk songs and dances.<ref name=Grove355>Shelemay, pp. 355–356</ref> | ||

| '']'' Amhara secular folk music developed in the countryside<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/ethio_0066-2127_2013_num_28_1_1539|title=Investigating qәñәt in Amhara secular music: An acoustic and historical study|journal=Annales d'Éthiopie|year=2013|volume=28|issue=1|pages=299–322|last1=Weisser|first1=Stéphanie|last2=Falceto|first2=Francis|doi=10.3406/ethio.2013.1539}}</ref> through the use of traditionel instruments such as the '']'', a one-string ] ]; the '']'', a six-string ]; and the '']'' flute played by the local village musicians called the ]s,<ref>{{Cite journal |author-link |

'']'' Amhara secular folk music developed in the countryside<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/ethio_0066-2127_2013_num_28_1_1539|title=Investigating qәñәt in Amhara secular music: An acoustic and historical study|journal=Annales d'Éthiopie|year=2013|volume=28|issue=1|pages=299–322|last1=Weisser|first1=Stéphanie|last2=Falceto|first2=Francis|doi=10.3406/ethio.2013.1539}}</ref> through the use of traditionel instruments such as the '']'', a one-string ] ]; the '']'', a six-string ]; and the '']'' flute played by the local village musicians called the ]s,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kebede |first=Ashenafi |author-link=Ashenafi Kebede |title = The "Azmari", Poet-Musician of Ethiopia |journal = The Musical Quarterly |volume = 61 |number = 1 |date = January 1975 |doi = 10.1093/mq/lxi.1.47 |pages = 47–57 }}</ref> and the peasantry dancing the '']''; the most well known Amharan folk dance.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |date=2017 |title=Ethiopia: history, culture and challenges |location=Munster, East Lansing |publisher=Michigan State University Press |page=207 |isbn=|oclc=978295392 }}</ref> | ||

| The '']'', a large ten-string lyre; is an important instrument solely devoted to the spiritual part of Amhara music.<ref>{{Cite |

The '']'', a large ten-string lyre; is an important instrument solely devoted to the spiritual part of Amhara music.<ref>{{Cite CiteSeerX|citeseerx=10.1.1.569.2160|title=FNRS-Université Libre de Bruxelles}}</ref> Other instruments includes the ''Meleket'' wind instrument, and the '']'' and ''Negarit'' drums. | ||

| From the 1950s onward foreign influence i.e. foreign educated Ethiopians and the availability of larger quantities of new instruments led to new genre's of Amharic music and ushered in the 1960s and 1970s |

From the 1950s onward foreign influence i.e. foreign educated ] and the availability of larger quantities of new instruments led to new genre's of Amharic music and ushered in the 1960s and 1970s ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.afropop.org/multi/interview/ID/107/Kay%2BKaufman%2BShelemay-Ethiopia%3A%2BEmpire%2Band%2BRevolution |title=Kay Kaufman Shelemay-Ethiopia: Empire and Revolution |website=www.afropop.org |access-date=11 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070214114013/http://www.afropop.org/multi/interview/ID/107/Kay%2BKaufman%2BShelemay-Ethiopia%3A%2BEmpire%2Band%2BRevolution |archive-date=14 February 2007 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/2012/11/08/164682116/samuel-yirga-ushers-in-a-golden-age-of-ethiopian-music|title = Samuel Yirga Ushers in a Golden Age of Ethiopian Music|newspaper = NPR.org}}</ref> The popular Ethio-Jazz genre pioneered by ] was created from the '']'' qañat of the Amhara combined with the use of Western instruments.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://explorepartsunknown.com/ethiopia/how-ethiopian-jazz-got-its-unique-sound/|title=How Ethiopian jazz got its unique sound|date=18 July 2018}}</ref> Saxophone legend ] instrumentalized the Amhara war cry ''Shellela'' into an genre in the 1950s before joining the Ethio-Jazz scene later in his career.<ref>{{cite book |last=Uhlig |first=Siegbert |date=2006 |title=Proceedings of the XVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Hamburg, July 20-25, 2003|location=Wiesbaden |publisher=Harrassowitz |page=185 |isbn=|oclc=71298502 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://writteninmusic.com/artikel/getatchew-mekuria-leeuw-der-leeuwen/|title = Getatchew Mekuria, leeuw der leeuwen}}</ref> Other Amharic artists from the ''Golden age'' such as ], Bahru Kegne, Kassa Tessema and Mary Armede were renowned for their mastery of traditionel instruments. | ||

| The political turmoil during the ] regime (1974-1991) led to censorship of music; night life came to a standstill through government imposed curfews and the curbing of musical performances. Notable Ethiopian musicians were jailed including those of Amhara descent such as |

The political turmoil during the ] regime (1974-1991) led to censorship of music; night life came to a standstill through government imposed curfews and the curbing of musical performances. Notable Ethiopian musicians were jailed including those of Amhara descent such as Ayalew Mesfin and ].<ref>Shelemay, 2022, Sing and Sing On: Sentinel Musicians and the Making of the Ethiopian American Diaspora</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.leguesswho.nl/lineup/ayalew-mesfin-debo-band|title = Line-up}}</ref> A revival of '']''; Amharic ] songs which uses ] known as ''sam-enna warq'' (''wax and gold'') was used for subversive dialogue and resistance to state censorship. Thousands of Ethiopians including musicians migrated during this period to form communities in different countries.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/37173 | title=Continuity and change: Some aspects of Ethiopian music in Australia | year=2011 | last1=Jong | first1=De | last2=Elizabeth | first2=Holly }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.brilliant-ethiopia.com/ethiopian-music|title = Ethiopian Music | Brilliant Ethiopia}}</ref> | ||

| ] songs of resistance against the autocratic EPRDF regime led by the ] (1991-2018) continued; with prevailing themes being rampant corruption, economic favoritism, excessive emphasis on ethnic identity and its ability to undermine national unity. Amharic musicians; such as |

] songs of resistance against the autocratic ] regime led by the ] (1991-2018) continued; with prevailing themes being rampant corruption, economic favoritism, excessive emphasis on ethnic identity and its ability to undermine national unity. Amharic musicians; such as Getish Mamo, Nhatty Man, ] and others turned to the old tradition of ''sam-enna warq'' and used layered expression to evade skirt stringent censorship and oppressive laws (such as the anti-terror law) while reminding the people of their similarities and the importance of maintaining solidarity.<ref>{{cite book |last=Onyebadi |first=Uche |date=2019 |title=Music and messaging in the African political arena |location=Hershey, PA |publisher=IGI Global |pages= 12–17|isbn=|oclc=1080436962 }} | ||

| </ref> | </ref> | ||

| In June 2022 ] bashed ] and his regime in a critical new song (Na'et), following the ]. In his song he tries to vent the suppressed public anger and indignation, the swelling public resentment to the chaos in the country.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://addiszeybe.com/teddy-afro-bashes-government-with-a-critical-new-single | title=Teddy Afro bashes government with a critical new single | date=23 June 2022 }}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:right; margin-right:50px;" | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| |- | |||

| <gallery mode="nolines"> | |||

| ! align=center |]<br /><small>(1935-2016)</small> | |||

| File:Getatchew Mekuria (cropped).jpg|]<small>(1935-2016)</small> | |||

| File:Tilahun.jpg|]<small>(1940-2009)</small> | |||

| File:Eurock2010-34 (cropped).jpg|]<small>(1941–2021)</small> | |||

| File:Mulatu Astatke & The Heliocentrics, Barbican.jpg|]<br /><small>(1943–present)</small> | |||

| File:Alemu Aga playing Begenna.jpg|]<br /><small>(1950–present)</small> | |||

| File:Aster Aweke.jpeg|]<br /><small>(1959–present)</small> | |||

| File:Teddy Afro.jpg|]<br /><small>(1976–present)</small> | |||

| File:Zeritu at the Gumma awards, February 23rd 2015.jpg|]<br /><small>(1984–present)</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| | align=left | ] || align=left | ] || align="left" | ] || align="left" | ]|| align="left" | ] || align="left" | ]|| align="left" |]|| align="left" | ] | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Art=== | ===Art=== | ||

| Line 161: | Line 162: | ||

| ===Kinship and marriage=== | ===Kinship and marriage=== | ||

| The Amhara culture recognizes kinship, but unlike other ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa region, it has a |

The Amhara culture recognizes kinship, but unlike other ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa region, it has a lesser role. Household relationships are primary, and the major economic, political and cultural functions are not based on kin relationships among the Amharas. Rather abilities of the individual matter. For example, states Donald Levine, the influence of clergy among the Amhara has been based on "ritual purity, doctrinal knowledge, ability to perform miracles and capacity to provide moral guidance".<ref name="LevineGE2000" />{{rp|120}} The social relationships in the Amhara culture are predominantly based on hierarchical patterns and individualistic associations.<ref name="LevineGE2000" />{{rp|123}} | ||