| Revision as of 19:20, 14 June 2010 view sourceMidnightblueowl (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users113,106 editsm →Attitude to occultism← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:50, 20 January 2025 view source Diannaa (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators350,242 edits we normally add a cite for a quote, even if it's in the leadTag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Hitler}} | |||

| {{Redirect2|Hitler|The Führer||Hitler (disambiguation)|and|Führer (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}}{{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| {{pp-extended|small=yes}} | |||

| ATTENTION! PLEASE READ BEFORE EDITING. | |||

| {{Use shortened footnotes|date=February 2021}} | |||

| This article is frequently vandalized, and vandalism is reverted immediately. If you wish to try test editing, you can do so in our sandbox located at http://en.wikipedia.org/Wikipedia:Sandbox. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2024}}{{Use British English|date=November 2024}} | |||

| Thanks! | |||

| {{Infobox officeholder | |||

| This page is frequently scrutinized and debated. If you wish to edit this article with factual, neutral information, scroll down. Before adding to this article, though, check if there is a sub-article on the subject you are editing about. This will keep clutter to a minimum. Thank you. | |||

| | name = Adolf Hitler | |||

| --> | |||

| | image = Hitler portrait crop.jpg | |||

| {{Infobox President | |||

| | |

| alt = Portrait of Adolf Hitler, 1938 | ||

| | caption = Official portrait, 1938 | |||

| |nationality = Austrian citizen until 1925<ref>"", 7 April 1925 {{de icon}}. Translation: "Hitler's official application to end his Austrian citizenship". NS-Archiv. Retrieved on 2008-08-19.</ref> German citizen after 1932 | |||

| | office = ] | |||

| |citizenship = Austrian (1889–1932)<br />German (1932–1945) | |||

| | term_start = 2 August 1934 | |||

| |image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-S33882, Adolf Hitler retouched.jpg | |||

| | term_end = 30 April 1945 | |||

| |caption = | |||

| | predecessor = ] {{Avoid wrap|(as ])}} | |||

| |birth_date = 20 April 1889 | |||

| | successor = ] {{Avoid wrap|(as President)}} | |||

| |birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | office2 = ] | |||

| |death_date = {{Death date and age|1945|4|30|1889|4|20|df=yes}} | |||

| | 1blankname2 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |death_place = Berlin, ] | |||

| | 1namedata2 = ] {{nowrap|(1933–1934)}} | |||

| |death_cause = Suicide | |||

| | president2 = Paul von Hindenburg {{nowrap|(1933–1934)}} | |||

| |party = ] (1920–1921)<br/>] (1921–1945) | |||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| |religion = See ] | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| |spouse = ]<br />(married on 29 April 1945) | |||

| | term_start2 = 30 January 1933 | |||

| |occupation = politician, ], artist, writer | |||

| | term_end2 = 30 April 1945 | |||

| |order = ] | |||

| | office3 = ] | |||

| |term_start = 2 August 1934 | |||

| | deputy3 = ] {{nowrap|(1933–1941)}} | |||

| |term_end = 30 April 1945 | |||

| | term_start3 = 29 July 1921 | |||

| |predecessor = ]<br/>(as President) | |||

| | term_end3 = 30 April 1945 | |||

| |successor = ]<br/>(as President) | |||

| | predecessor3 = ] (Party Chairman) | |||

| |order2 = ] | |||

| | successor3 = ] (]) | |||

| |term_start2 = 30 January 1933 | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1889|04|20|df=y}} | |||

| |term_end2 = 30 April 1945 | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| |predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1945|04|30|1889|04|20|df=y}} | |||

| |successor2 = ] | |||

| | death_place = Berlin, Nazi Germany | |||

| |signature = Hitler Signature2.svg | |||

| | death_cause = ] | |||

| |footnotes= | |||

| | citizenship = {{Unbulleted list|Austria (])|] (1925–1932)|Germany (from 1932)}} | |||

| |allegiance={{flagicon|German Empire}} ] | |||

| | party = ] (from 1920) | |||

| |branch=] ] | |||

| | otherparty = ] (1919–1920) | |||

| |unit=16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|29 April 1945|30 April 1945|end=d}} | |||

| |serviceyears=1914–1918 | |||

| | parents = {{Unbulleted list|]|]}} | |||

| |rank='']'' | |||

| | relatives = ] | |||

| |battles=] | |||

| | cabinet = ] | |||

| |awards=]<br/>] | |||

| | signature = Hitler’s signature (1944).svg | |||

| | signature_alt = Signature of Adolf Hitler | |||

| | module = {{Listen|pos=center|embed=yes|filename=Adolf Hitler’s last speech.ogg|title=Adolf Hitler's voice|type=speech|description=Hitler's last recorded speech<br />Recorded January 1945}} | |||

| | allegiance = {{Unbulleted list|]|]|]}} | |||

| | branch_label = Branch | |||

| | branch = {{Tree list}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| {{Tree list/end}} | |||

| | serviceyears = 1914–1920 | |||

| | rank = {{lang|de|]}} | |||

| | commands = {{Unbulleted list|] (from 1941)|] (1942)}} | |||

| | unit = | |||

| | battles_label = Wars | |||

| | battles = {{Tree list}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] {{WIA}} | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Tree list/end}} | |||

| | mawards = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{ |

{{Adolf Hitler series}} | ||

| '''Adolf Hitler'''{{efn|{{IPA|de|ˈaːdɔlf ˈhɪtlɐ|x|GT AH AMS.ogg|small=no}}}} (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of ] from 1933 until ] in 1945. ] as the leader of the ],{{efn|Officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ({{langx|de|Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei}}{{Efn|Pronounced {{IPA|de|natsi̯oˈnaːlzotsi̯aˌlɪstɪʃə ˈdɔʏtʃə ˈʔaʁbaɪtɐpaʁˌtaɪ||De-Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei.ogg}}}} or NSDAP)}} becoming ] in 1933 and then taking the title of {{lang|de|]}} in 1934.{{efn|The position of {{lang|de|Führer und Reichskanzler}} ("Leader and Chancellor") replaced the position of President, which was the ] for the ]. Hitler took this title after the death of ], who had been serving as President. He was afterwards both head of state and ], with the full official title of {{lang|de|Führer und Reichskanzler des Deutschen Reiches und Volkes}} ("Führer and Reich Chancellor of the German Reich and People").{{sfn|Shirer|1960|pp=226–227}}{{sfn|Overy|2005|p=63}}}} His ] on 1 September 1939 marked the start of the ]. He was closely involved in military operations throughout the war and was central to the perpetration of ]: the ] of ]. | |||

| '''Adolf Hitler''' ({{IPA-de|ˈadɔlf ˈhɪtlɐ}}; 20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an ]-born ] politician and the leader of the ] ({{lang-de| Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei}}, abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. He was ] from 1933 to 1945 and, after 1934, also ] as '']'', ruling the country as an absolute dictator of ]. | |||

| Hitler was born in ] in ] and was raised near ]. He lived in ] in the first decade of the 1900s before moving to ] in 1913. He was decorated during ] in ], receiving the ]. In 1919, he joined the ] (DAP), the precursor of the Nazi Party, and in 1921 was appointed leader of the Nazi Party. In 1923, he attempted to seize governmental power in ] and was sentenced to five years in prison, serving just over a year of his sentence. While there, he dictated the first volume of his autobiography and ] {{lang|de|]}} (''My Struggle''). After his early release in 1924, Hitler gained popular support by attacking the ] and promoting ], ], and ] with ] oratory and ]. He frequently denounced ] as being part of an ]. | |||

| A decorated veteran of ], Hitler joined the precursor of the Nazi Party (]) in 1919 and became leader of NSDAP in 1921. Following his imprisonment after a ] in ] in 1923, he gained support by promoting ], ], ], and ] with ] ] and ]. He was appointed chancellor in 1933, and quickly transformed the ] into the ], a ] ] based on the ] and ] ideals of ]. | |||

| By November 1932, the Nazi Party held the most seats in the '']'', but not a majority. No political parties were able to form a majority coalition in support of a candidate for chancellor. Former chancellor ] and other conservative leaders convinced President ] to appoint Hitler as chancellor on 30 January 1933. Shortly thereafter, the Reichstag passed the ], which began the process of transforming the ] into Nazi Germany, a ] dictatorship based on the ] and ] ideology of ]. Upon Hindenburg's death on 2 August 1934, Hitler succeeded him, becoming simultaneously the head of state and government, with absolute power. Domestically, Hitler implemented numerous ] and sought to deport or kill ]. His first six years in power resulted in rapid economic recovery from the ], the abrogation of restrictions imposed on Germany after World War I, and the annexation of territories inhabited by millions of ethnic Germans, which initially gave him significant popular support. | |||

| Hitler ultimately wanted to establish a ] of absolute Nazi German ] in Europe. To achieve this, he pursued a ] with the declared goal of seizing '']'' ("living space") for the ]; directing the resources of the state towards this goal. This included the rearmament of Germany, which culminated in 1939 when the '']'' ]. In response, the ] and ] declared war against Germany, leading to the outbreak of ] ].<ref>{{harvnb|Keegan|1989}}</ref> | |||

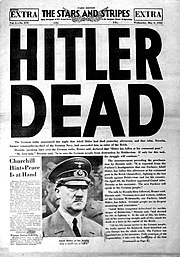

| One of Hitler's key goals was {{lang|de|]}} ({{Literal translation|living space}}) for the German people in Eastern Europe, and his aggressive, ] foreign policy is considered the primary ]. He directed large-scale rearmament and, on 1 September 1939, invaded Poland, causing Britain and France to ]. In June 1941, Hitler ordered ]. In December 1941, he ]. By the end of 1941, German forces and the European ] occupied most of Europe and ]. These gains were gradually reversed after 1941, and in 1945 the ] defeated the German army. On 29 April 1945, he married his longtime partner, ], in the {{lang|de|]}} in Berlin. The couple committed suicide the next day to avoid capture by the Soviet ]. In accordance with Hitler's wishes, their corpses were burned. | |||

| Within three years, Germany and the ] had occupied most of Europe, and most of ], ] and ] and the Pacific Ocean. However, with the reversal of the Nazi invasion of the ], the ] gained the upper hand from 1942 onwards. By 1945, Allied armies had invaded German-held Europe from all sides. Nazi forces engaged in numerous violent acts during the war, including the systematic murder of as many as 17 million civilians,<ref>{{Citation |title=The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust |last=Niewyk |first=Donald L. |authorlink= |coauthors=Francis R. Nicosia |year=2000 |publisher=Columbia University Press |location= |isbn=0231112009 |page=45 }}</ref> an estimated six million of whom were Jews targeted in ] and between 500,000 and 1,500,000 were ].<ref>]. <!-- {{dead link|date=July 2009}} -->, published in Stone, D. (ed.) (2004) ''The Historiography of the Holocaust''. Palgrave, Basingstoke and New York.</ref> Others targeted included ], ], ], ], ], ], and other ]. | |||

| The historian and biographer ] described Hitler as "the embodiment of modern political evil".{{sfn|Kershaw|2000b|p=xvii}} Under Hitler's leadership and ], the Nazi regime was responsible for the genocide of an estimated six million Jews and millions of other victims, whom he and his followers deemed {{lang|de|]en}} ({{Literal translation|subhumans}}) or socially undesirable. Hitler and the Nazi regime were also responsible for the deliberate killing of an estimated 19.3 million civilians and prisoners of war. In addition, 28.7 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of military action in the European ]. The number of ] was unprecedented in warfare, and the casualties constitute the ]. | |||

| In the final days of the war, during the ] in 1945, Hitler married his long-time mistress ] and, to avoid capture by Soviet forces less than two days later, the two ]<ref>{{Citation | last = Wistrich | first = Robert S. | title = Who's Who In Nazi Germany? | isbn = 978-0415118880 | url = http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/braun.html | accessdate = 2008-09-07 | year = 1995 | publisher = Routledge | location = London}}</ref> on 30 April 1945. | |||

| == |

== Ancestry == | ||

| {{see also|Hitler family|}} | |||

| ===Ancestry=== | |||

| Hitler's father, ], was an ] child of ] so his paternity was not listed on his birth certificate and he bore his mother's surname.<ref name="Shirer">{{citation | last = Shirer | first = W. L. | year = 1960 | title = ] | publisher = Simon and Schuster | location = New York}}</ref><ref name="Rosenbaum, R 1999">] (1999). ''].'' Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-095339-X</ref> In 1842, ] married Maria and in 1876 Johann (spelling his name ''Hitler'') testified before a notary and three witnesses that he was the father of his stepson Alois.<ref name="Shirer_paternity">{{citation | last = Shirer | page = 7 | title = The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=sY8svb-MNUwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=the+rise+and+fall+of+the+third+reich&hl=en&ei=OswPTIG8HY7iNY2wudEM&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=alois%20hitler%20%20johann&f=false}}</ref> At age 39, Alois took the surname Hitler. This surname was variously spelled ''Hiedler'', ''Hüttler'', ''Huettler'' and ''Hitler'', and was probably regularized to ''Hitler'' by a clerk. The origin of the name is either "one who lives in a hut" (] ''Hütte''), "shepherd" (Standard German ''hüten'' "to guard", English ''heed''), or is from the ] word ''Hidlar'' and ''Hidlarcek''. (Regarding the first two theories: some German ]s make little or no distinction between the ''ü''-sound and the ''i''-sound.)<ref name="Rosenbaum, R 1999"/> | |||

| Hitler's father, ] (1837–1903), was the ] child of ].{{sfn|Bullock|1999|p=24}} The baptismal register did not show the name of his father, and Alois initially bore his mother's surname, "Schicklgruber". In 1842, ] married Alois's mother. Alois was brought up in the family of Hiedler's brother, ].{{sfn|Maser|1973|p=4}} In 1876, Alois was made legitimate and his baptismal record annotated by a priest to register Johann Georg Hiedler as Alois's father (recorded as "Georg Hitler").{{sfn|Maser|1973|p=15}}{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=5}} Alois then assumed the surname "Hitler",{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=5}} also spelled {{lang|de|"Hiedler", "Hüttler"|italic=no}}, or {{lang|de|"Huettler"|italic=no}}. The name is probably based on the German word {{lang|de|Hütte}} ({{Literal translation|hut}}), and has the meaning "one who lives in a hut".{{sfn|Jetzinger|1976|p=32}} | |||

| Despite this testimony, Alois' paternity has been the subject of controversy. After receiving a "] letter" from Hitler's nephew ] threatening to reveal embarrassing information about Hitler's family tree, Nazi Party lawyer ] investigated, and, in his memoirs, claimed to have uncovered letters revealing that Alois' mother, ], was employed as a housekeeper for a Jewish family in ] and that the family's 19-year-old son, ], fathered Alois.<ref name="Rosenbaum, R 1999"/> No evidence has ever been produced to support Frank's claim, and Frank himself said Hitler's full Aryan blood was obvious.<ref>Dieter Schenk, ''Frank: Hitlers Kronjurist und General-Gouverneur'', 2006, p.65. ISBN 978-3100735621: ''"Dass Adolf Hitler bestimmt kein Judenblut in den Adern hatte, scheint mir aus seiner ganzen Art dermaßen eklatant bewiesen, dass es keines weiteren Wortes bedarf,"'' (p.330 of Frank's memoirs published in 1953 as ''Im Angesicht des Galgens. Deutung Hitlers und seiner Zeit aufgrund eigener Erlebnisse und Erkenntnisse'').</ref> Frank's claims were widely believed in the 1950s, but by the 1990s, were generally doubted by historians.<ref>{{harvnb|Toland|1991|pp=246–47}}</ref><ref name="Kershaw">{{Citation | last = Kershaw | first = Ian | authorlink = Ian Kershaw | coauthors = | title = Hitler: 1889–1936: Hubris | publisher = Penguin Books | year = 1998 | location = City of Westminster, London, England | pages = 8–9 | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = }}</ref> ] dismisses the Frankenberger story as a "smear" by Hitler's enemies, noting that all Jews had been expelled from Graz in the 15th century and were not allowed to return until well after Alois was born.<ref name="Kershaw"/> | |||

| Nazi official ] suggested that Alois's mother had been employed as a housekeeper by a Jewish family in ], and that the family's 19-year-old son Leopold Frankenberger had fathered Alois, a claim that came to be known as the ].{{sfn|Rosenbaum|1999|p=21}} No Frankenberger was registered in Graz during that period, and no record has been produced of Leopold Frankenberger's existence,{{sfn|Hamann|2010|p=50}} so historians dismiss the claim that Alois's father was Jewish.{{sfn|Toland|1992|pp=246–247}}{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|pp=8–9}} | |||

| ===Childhood=== | |||

| Adolf Hitler was born at the Gasthof zum Pommer, an inn in ], ], the fourth of ] and ]'s six children. ]]]At the age of three, his family moved to Kapuzinerstrasse 5<ref>Anna Elisabeth Rosmus, ''Out of Passau: Leaving a City Hitler Called Home'', p. 41</ref> in ], Germany where the young Hitler would acquire ]n rather than Austrian as his lifelong native dialect.<ref>John Toland, ''Adolf Hitler'', 1976 ISBN 0-385-42053-6</ref> In 1894, the family moved to ] near ], then in June 1895, Alois retired to a small landholding at Hafeld near ], where he tried his hand at farming and beekeeping. During this time, the young Hitler attended school in nearby Fischlham. As a child, he tirelessly played "]" and, by his own account, became fixated on war after finding a picture book about the ] in his father's things.<ref name="Payne">{{harvnb|Payne|1990}}</ref> He wrote in '']'': "It was not long before the great historic struggle had become my greatest spiritual experience. From then on, I became more and more enthusiastic about everything that was in any way connected with war or, for that matter, with soldiering." | |||

| == Early years == | |||

| His father's efforts at Hafeld ended in failure and the family moved to Lambach in 1897. There, Hitler attended a Catholic school located in an 11th-century ] cloister whose walls were engraved in a number of places with crests containing the symbol of the ].<ref>Rosmus, ''op cit'', p. 35</ref> In 1898, the family returned permanently to Leonding. | |||

| === Childhood and education === | |||

| Adolf Hitler was born on 20 April 1889 in ], a town in ] (present-day Austria), close to the border with the ].{{sfn|House of Responsibility}}{{sfn|Bullock|1999|p=23}} He was the fourth of six children born to Alois Hitler and his third wife, ]. Three of Hitler's siblings—Gustav, Ida, and Otto—died in infancy.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=4}} Also living in the household were Alois's children from his second marriage: Alois Jr. (born 1882) and ] (born 1883).{{sfn|Toland|1976|p=6}} When Hitler was three, the family moved to ], Germany.{{sfn|Rosmus|2004|p=33}} There he acquired the distinctive ], rather than ], which marked his speech throughout his life.{{sfn|Keller|2010|p=15}}{{sfn|Hamann|2010|pp=7–8}}{{sfn|Kubizek|2006|p=37}} The family returned to Austria and settled in ] in 1894, and in June 1895 Alois retired to Hafeld, near ], where he farmed and kept bees. Hitler attended {{lang|de|]}} (a state-funded primary school) in nearby ].{{sfn|Kubizek|2006|p=92}}{{sfn|Hitler|1999|p=6}} | |||

| ] | |||

| His younger brother ] died of ] on 2 February 1900, causing permanent changes in Hitler. He went from a confident, outgoing boy who found school easy, to a morose, detached, sullen boy who constantly battled his father and his teachers.<ref>{{harvnb|Payne|1990|p=22}}</ref> | |||

| The move to Hafeld coincided with the onset of intense father-son conflicts caused by Hitler's refusal to conform to the strict discipline of his school.{{sfn|Fromm|1977|pp=493–498}} Alois tried to browbeat his son into obedience, while Adolf did his best to be the opposite of whatever his father wanted.{{sfn|Hamann|2010|pp=10–11}} Alois would also beat his son, although his mother tried to protect him from regular beatings.{{sfn|Diver|2005}} | |||

| Alois Hitler's farming efforts at Hafeld ended in failure, and in 1897 the family moved to Lambach. The eight-year-old Hitler took singing lessons, sang in the church choir, and even considered becoming a priest.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|pp=10–11}} In 1898, the family returned permanently to Leonding. Hitler was deeply affected by the death of his younger brother Edmund in 1900 from ]. Hitler changed from a confident, outgoing, conscientious student to a morose, detached boy who constantly fought with his father and teachers.{{sfn|Payne|1990|p=22}} ] recalled how Adolf was a teenage bully who would often slap her.{{sfn|Diver|2005}} | |||

| Hitler was close to his mother, but had a troubled relationship with his ] father, who frequently beat him, especially in the years after Alois' retirement and disappointing farming efforts.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.history.com/topics/adolf-hitler/videos#adolf-hitler |title=Adolf Hitler Video — |publisher=History.com |date= |accessdate=2010-04-28}}</ref> Alois wanted his son to follow in his footsteps as an Austrian customs official, and this became a huge source of conflict between them.<ref name="Payne"/> Despite his son's pleas to go to classical high school and become an artist, his father sent him to the Realschule in Linz, a technical high school of about 300 students, in September 1900. Hitler rebelled, and in '']'' confessed to failing his first year in hopes that once his father saw "what little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." But Alois never relented and Hitler became even more bitter and rebellious. | |||

| Alois had made a successful career in the customs bureau and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=9}} Hitler later dramatised an episode from this period when his father took him to visit a customs office, depicting it as an event that gave rise to an unforgiving antagonism between father and son, who were both strong-willed.{{sfn|Hitler|1999|p=8}}{{sfn|Keller|2010|pp=33–34}}{{sfn|Fest|1977|p=32}} Ignoring his son's desire to attend a classical high school and become an artist, Alois sent Hitler to the '']'' in Linz in September 1900.{{efn|name=Realschule}}{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=8}} Hitler rebelled against this decision, and in {{lang|de|]}} states that he intentionally performed poorly in school, hoping that once his father saw "what little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me devote myself to my dream".{{sfn|Hitler|1999|p=10}} | |||

| For young Hitler, ] quickly became an obsession, and a way to rebel against his father, who proudly served the ]. Most people who lived along the German-Austrian border considered themselves German-Austrians, but Hitler expressed loyalty only to Germany. In defiance of the Austrian monarchy, and his father who continually expressed loyalty to it, Hitler and his young friends liked to use the German greeting "''Heil''", and sing the German anthem "]" instead of the ].<ref name="Payne"/> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = right | |||

| After Alois' sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's behaviour at the technical school became even more disruptive, and he was asked to leave. He enrolled at the '']'' in ] in 1904, but upon completing his second year, he and his friends went out for a night of celebration and drinking, and an intoxicated Hitler tore his school certificate into four pieces and used it as toilet paper. When someone turned the stained certificate in to the school's director, he "... gave him such a dressing-down that the boy was reduced to shivering jelly. It was probably the most painful and humiliating experience of his life."<ref>{{harvnb|Payne|1990|p=41}}</ref> Hitler was expelled, never to return to school again. | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| At age 15, Hitler took part in his ] on ], 22 May 1904, at the Linz Cathedral.<ref>{{harvnb|Toland|1991|p=18}}</ref> His sponsor was Emanuel Lugert, a friend of his late father.<ref>{{Citation |last=Jetzinger |first=Franz |authorlink=Franz Jetzinger |coauthors= |title=Hitler's youth |year=1976 |publisher=Greenwood Press |location=Westport, Conn. |isbn=083718617X, |page=74}}</ref> | |||

| | total_width = 230 | |||

| | image1 = Alois Hitler in his last years 2.jpg | |||

| ===Early adulthood in Vienna and Munich=== | |||

| | caption1 = Hitler's father, ], {{circa|1900}} | |||

| From 1905 on, Hitler lived a ] life in ] on an orphan's pension and support from his mother. He was rejected twice by the ] (1907–1908), citing "unfitness for painting", and was told his abilities lay instead in the field of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Bullock|1962|pp=30–31}}</ref> His ] reflect a fascination with the subject: | |||

| | image2 = Klara Hitler.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = Hitler's mother, ], 1870s | |||

| <blockquote>The purpose of my trip was to study the picture gallery in the Court Museum, but I had eyes for scarcely anything but the Museum itself. From morning until late at night, I ran from one object of interest to another, but it was always the buildings which held my primary interest.<ref name = "Kampf-vol1ch2">{{harvnb|Hitler|1998|loc=§2}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| }} | |||

| Like many Austrian Germans, Hitler began to develop ] ideas from a young age.{{sfn|Evans|2003|pp=163–164}} He expressed loyalty only to Germany, despising the declining ] and its rule over an ethnically diverse empire.{{sfn|Bendersky|2000|p=26}}{{sfn|Ryschka|2008|p=35}} Hitler and his friends used the greeting "Heil", and sang the "]" instead of the ].{{sfn|Hamann|2010|p=13}} After Alois's sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's performance at school deteriorated and his mother allowed him to leave.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=10}} He enrolled at the ''Realschule'' in ] in September 1904, where his behaviour and performance improved.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=19}} In 1905, after passing a repeat of the final exam, Hitler left the school without any ambitions for further education or clear plans for a career.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=20}} | |||

| Following the school rector's recommendation, he too became convinced this was his path to pursue, yet he lacked the proper academic preparation for architecture school: | |||

| <blockquote>In a few days I myself knew that I should some day become an architect. To be sure, it was an incredibly hard road; for the studies I had neglected out of spite at the Realschule were sorely needed. One could not attend the Academy's architectural school without having attended the building school at the Technic, and the latter required a high-school degree. I had none of all this. The fulfilment of my artistic dream seemed physically impossible.<ref name = "Kampf-vol1ch2"/></blockquote> | |||

| ] | |||

| On 21 December 1907, Hitler's mother died of ] at age 47. Ordered by a court in Linz, Hitler gave his share of the ]s' benefits to his sister Paula. When he was 21, he inherited money from an aunt. He struggled as a painter in Vienna, copying scenes from postcards and selling his paintings to merchants and tourists. After being rejected a second time by the Academy of Arts, Hitler ran out of money. In 1909, he lived in a shelter for the ]. By 1910, he had settled into a ]. Another resident of the house, ], sold Hitler's paintings until the two men had a bitter falling-out.<ref>{{Citation | |||

| | last = Lehrer | |||

| | first = Steven | |||

| | title = Hitler Sites: A City-by-city Guidebook (Austria, Germany, France, United States) | |||

| | publisher = McFarland | |||

| | year = 2002 | |||

| | page = 224 | |||

| | isbn = 0786410450}}</ref> | |||

| Hitler said he first became an anti-Semite in Vienna,<ref name="Kampf-vol1ch2"/> which had a large Jewish community, including ] who had fled the ]s in Russia. According to childhood friend ], however, Hitler was a "confirmed anti-Semite" before he left ].<ref name = "Kampf-vol1ch2"/> Vienna at that time was a hotbed of traditional religious prejudice and 19th century ]. Hitler may have been influenced by the writings of the ideologist and anti-Semite ] and ]s from politicians such as ], founder of the ] and ], the composer ], and ], leader of the ] ''Away from Rome!'' movement. Hitler claims in ''Mein Kampf'' that his transition from opposing antisemitism on religious grounds to supporting it on racial grounds came from having seen an ]. | |||

| {{bquote|There were very few Jews in Linz. In the course of centuries the Jews who lived there had become ] in external appearance and were so much like other human beings that I even looked upon them as Germans. The reason why I did not then perceive the absurdity of such an illusion was that the only external mark which I recognized as distinguishing them from us was the practice of their strange religion. As I thought that they were persecuted on account of their faith my aversion to hearing remarks against them grew almost into a feeling of abhorrence. I did not in the least suspect that there could be such a thing as a systematic antisemitism. | |||

| Once, when passing through the inner City, I suddenly encountered a phenomenon in a long caftan and wearing black side-locks. My first thought was: Is this a Jew? They certainly did not have this appearance in Linz. I carefully watched the man stealthily and cautiously but the longer I gazed at the strange countenance and examined it feature by feature, the more the question shaped itself in my brain: Is this a German?<ref name = "Kampf-vol1ch2"/>}} | |||

| If this account is true, Hitler apparently did not act on his new belief. He often was a guest for dinner in a noble Jewish house, and he interacted well with Jewish merchants who tried to sell his paintings.<ref>{{harvnb|Hamann|Thornton|1999}}</ref> | |||

| Hitler may also have been influenced by ]'s '']''. In ''Mein Kampf'', Hitler refers to Martin Luther as a great warrior, a true statesman, and a great reformer, alongside ] and ].<ref>{{harvnb|Hitler|1998|loc=§7}}</ref> ], writing after the Holocaust, concluded that "without any question, ] influenced the political, spiritual and social history of Germany in a way that, after careful consideration of everything, can be described only as fateful."<ref>{{harvnb|Röpke1946|p=117}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Waite|1993|p=251}}</ref> | |||

| Hitler claimed that Jews were enemies of the ]. He held them responsible for Austria's crisis. He also identified certain forms of socialism and ], which had many Jewish leaders, as Jewish movements, merging his antisemitism with anti-]. Later, blaming Germany's military defeat in World War I on the ], he considered Jews the culprits of Imperial Germany's downfall and subsequent economic problems as well. | |||

| === Early adulthood in Vienna and Munich === | |||

| Generalising from tumultuous scenes in the parliament of the multi-national Austrian monarchy, he decided that the democratic ] was unworkable. However, according to August Kubizek, his one-time roommate, he was more interested in Wagner's operas than in his politics. | |||

| {{See also|Paintings by Adolf Hitler}} | |||

| ] where Hitler spent his early adolescence]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1907, Hitler left Linz to live and study fine art in ], financed by orphan's benefits and support from his mother. He applied for admission to the ] but was rejected twice.{{sfn|Hitler|1999|p=20}}{{sfn|Bullock|1962|pp=30–31}} The ] suggested Hitler should apply to the School of Architecture, but he lacked the necessary academic credentials because he had not finished secondary school.{{sfn|Bullock|1962|p=31}} | |||

| On 21 December 1907, his mother died of breast cancer at the age of 47; Hitler was 18 at the time. In 1909, Hitler ran out of money and was forced to live a ] life in homeless shelters and the ].{{sfn|Bullock|1999|pp=30–33}}{{sfn|Hamann|2010|p=157}} He earned money as a casual labourer and by painting and selling watercolours of Vienna's sights.{{sfn|Hitler|1999|p=20}} During his time in Vienna, he pursued a growing passion for architecture and music, attending ten performances of {{lang|de|]}}, his favourite ] opera.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|pp=41, 42}} | |||

| Hitler received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to ]. He wrote in ''Mein Kampf'' that he had always longed to live in a "real" German city. In Munich, he became more interested in architecture and, he says, the writings of ]. Moving to Munich also helped him escape ] in Austria for a time, but the Munich police (acting in cooperation with the Austrian authorities) eventually arrested him. After a physical exam and a contrite plea, he was deemed unfit for service and allowed to return to Munich. However, when Germany entered World War I in August 1914, he petitioned King ] for permission to serve in a ]n regiment. This request was granted, and Adolf Hitler enlisted in the Bavarian army.<ref>{{harvnb|Shirer|1961}}</ref> | |||

| In Vienna, Hitler was first exposed to racist rhetoric.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=26}} ] such as mayor ] exploited the city's prevalent ] sentiment, occasionally also espousing German nationalist notions for political benefit. German nationalism was even more widespread in the ] district, where Hitler then lived.{{sfn|Hamann|2010|pp=243–246}} ] became a major influence on Hitler,{{sfn|Nicholls|2000|pp=236, 237, 274}} and he developed an admiration for ].{{sfn|Hamann|2010|p=250}} Hitler read local newspapers that promoted prejudice and utilised Christian fears of being swamped by an influx of Eastern European Jews{{sfn|Hamann|2010|pp=341–345}} as well as pamphlets that published the thoughts of philosophers and theoreticians such as ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Hamann|2010|p=233}} During his life in Vienna, Hitler also developed fervent ]s.{{sfn|Britannica: Nazism}}{{sfn|Pinkus|2005|p=27}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The origin and development of Hitler's anti-Semitism remains a matter of debate.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|pp=60–67}} His friend ] claimed that Hitler was a "confirmed anti-Semite" before he left Linz.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=25}} However, historian Brigitte Hamann describes Kubizek's claim as "problematical".{{sfn|Hamann|2010|p=58}} While Hitler states in {{lang|de|Mein Kampf}} that he first became an anti-Semite in Vienna,{{sfn|Hitler|1999|p=52}} ], who helped him sell his paintings, disagrees. Hitler had dealings with Jews while living in Vienna.{{sfn|Toland|1992|p=45}}{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|pp=55, 63}}{{sfn|Hamann|2010|p=174}} Historian ] states that "historians now generally agree that his notorious, murderous anti-Semitism emerged well after Germany's defeat , as a product of the paranoid ] for the catastrophe".{{sfn|Evans|2011}} | |||

| ===World War I=== | |||

| Hitler served in France and Belgium in the 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment (called ''Regiment List'' after its first commander), ending the war as a '']'' (equivalent at the time to a ] in the British and ] in the American armies). He was a ], "a dangerous enough job"<ref>{{harvnb|Bullock|1962|pp=50–51}}</ref> on the Western Front, and was often exposed to enemy fire. He participated in a number of major battles on the ], including the ], the ], the ] and the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Shirer|1990|p=53}}</ref> The Battle of Ypres (October 1914), which became known in Germany as the ''Kindermord bei Ypern'' (Massacre of the Innocents) saw approximately 40,000 men (between a third and a half) of the nine infantry divisions present killed in 20 days, and Hitler's own company of 250 reduced to 42 by December. Biographer ] has said that this experience drove Hitler to become aloof and withdrawn for the remaining years of war.<ref>{{harvnb|Keegan|1987|p=239}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Hitler was twice decorated for bravery. He received the ], Second Class, in 1914 and Iron Cross, First Class, in 1918, an honour rarely given to a ''Gefreiter''.<ref>{{harvnb|Bullock|1962|p=52}}</ref> However, because the regimental staff thought Hitler lacked leadership skills, he was never promoted to '']'' (equivalent to a British corporal). Other historians say that the reason he was not promoted is that he was not a German citizen. His duties at regimental headquarters, while often dangerous, gave Hitler time to pursue his artwork. He drew cartoons and instructional drawings for an army newspaper. In 1916, he was wounded in either the groin area<ref>Alastair Jamieson, , ], retrieved on 20 November 2008</ref> or the left thigh<ref>Rosenbaum, Ron, "", ''Slate'', 28 Nov. 2008</ref> during the Battle of the Somme, but returned to the front in March 1917. He received the ] later that year. A noted German historian and author, ], referring to Hitler's experience at the front, suggests he did have at least some understanding of the military. | |||

| Hitler received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to ], Germany.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=27}} When he was conscripted into the ],{{sfn|Weber|2010|p=13}} he journeyed to ] on 5 February 1914 for medical assessment. After he was deemed unfit for service, he returned to Munich.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=86}} Hitler later claimed that he did not wish to serve the ] because of the mixture of races in its army and his belief that the collapse of Austria-Hungary was imminent.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=49}} | |||

| On 15 October 1918, Hitler was admitted to a ], temporarily blinded by a ] attack. The English psychologist ] and Bernhard Horstmann suggest the blindness may have been the result of a ] (then known as "]").<ref>{{harvnb|Lewis|2003}}</ref> Hitler said it was during this experience that he became convinced the purpose of his life was to "save Germany." Some scholars, notably ],<ref>{{harvnb|Dawidowicz|1986}}</ref> argue that an intention to exterminate Europe's Jews was fully formed in Hitler's mind at this time, though he probably had not thought through how it could be done. Most historians think the decision was made in 1941, and some think it came as late as 1942. | |||

| === World War I === | |||

| Two passages in ''Mein Kampf'' mention the use of ]: | |||

| {{Main|Military career of Adolf Hitler}} | |||

| ] comrades from the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 ({{Circa|1914–18)}}]] | |||

| In August 1914, at the outbreak of ], Hitler was living in Munich and voluntarily enlisted in the ].{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=90}} According to a 1924 report by the Bavarian authorities, allowing Hitler to serve was most likely an administrative error, because as an Austrian citizen, he should have been returned to Austria.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=90}} Posted to the ] (1st Company of the List Regiment),{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=90}}{{sfn|Weber|2010|pp=12–13}} he served as a dispatch ] on the ] in France and Belgium,{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=53}} spending nearly half his time at the regimental headquarters in ], well behind the front lines.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=54}}{{sfn|Weber|2010|p=100}} In 1914, he was present at the ]{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=30}} and in that year was decorated for bravery, receiving the ], Second Class.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=30}} | |||

| During his service at headquarters, Hitler pursued his artwork, drawing cartoons and instructions for an army newspaper. During the ] in October 1916, he was wounded in the left thigh when a shell exploded in the dispatch runners' dugout.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=30}}{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=57}} Hitler spent almost two months recovering in hospital at ], returning to his regiment on 5 March 1917.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=58}} He was present at the ] of 1917 and the ].{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=30}} He received the ] on 18 May 1918.{{sfn|Steiner|1976|p=392}} Three months later, in August 1918, on a recommendation by Lieutenant ], his Jewish superior, Hitler received the Iron Cross, First Class, a decoration rarely awarded at Hitler's {{lang|de|]}} rank.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=59}}{{sfn|Weber|2010a}} On 15 October 1918, he was temporarily blinded in a ] attack and was hospitalised in ].{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=59, 60}} While there, Hitler learned of Germany's defeat, and, by his own account, suffered a second bout of blindness after receiving this news.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|pp=97, 102}} | |||

| {{blockquote|At the beginning of the Great War, or even during the War, if twelve or fifteen thousand of these Jews who were corrupting the nation had been forced to submit to poison-gas . . . then the millions of sacrifices made at the front would not have been in vain.<ref>{{harvnb|Hitler|1998|loc=§15}}</ref>}} | |||

| Hitler described his role in World War I as "the greatest of all experiences", and was praised by his commanding officers for his bravery.{{sfn|Keegan|1987|pp=238–240}} His wartime experience reinforced his German patriotism, and he was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918.{{sfn|Bullock|1962|p=60}} His displeasure with the collapse of the war effort began to shape his ideology.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=61, 62}} Like other German nationalists, he believed the {{lang|de|Dolchstoßlegende}} (]), which claimed that the German army, "undefeated in the field", had been "stabbed in the back" on the ] by civilian leaders, Jews, ], and those who signed the ] that ended the fighting—later dubbed the "November criminals".{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=61–63}} | |||

| {{blockquote|These tactics are based on an accurate estimation of human weakness and must lead to success, with almost mathematical certainty, unless the other side also learns how to fight poison gas with poison gas. The weaker natures must be told that here it is a case of to be or not to be.<ref name = "Kampf-vol1ch2"/>}} | |||

| The ] stipulated that Germany had to relinquish several of its territories and ] the ]. The treaty imposed economic sanctions and levied heavy reparations on the country. Many Germans saw the treaty as an unjust humiliation. They especially objected to ], which they interpreted as declaring Germany responsible for the war.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=96}} The Versailles Treaty and the economic, social, and political conditions in Germany after the war were later exploited by Hitler for political gain.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=80, 90, 92}} | |||

| Hitler had long admired Germany, and during the war he had become a passionate German patriot, although he did not become a German citizen until 1932. Hitler found the war to be 'the greatest of all experiences' and afterwards he was praised by a number of his commanding officers for his bravery.<ref>{{harvnb|Keegan|1987|pp=238–240}}</ref> He was shocked by Germany's ] in November 1918 even while the German army still held enemy territory.<ref>{{harvnb|Bullock|1962|p=60}}</ref> Like many other German nationalists, Hitler believed in the '']'' ("dagger-stab legend") which claimed that the army, "undefeated in the field," had been "stabbed in the back" by civilian leaders and Marxists back on the ]. These politicians were later dubbed the '']''. | |||

| == Entry into politics == | |||

| The ] deprived Germany of various territories, ] the ] and imposed other economically damaging sanctions. The treaty re-created Poland, which even moderate Germans regarded as an outrage. The treaty also blamed Germany for all the horrors of the war, something which major historians such as ] now consider at least in part to be ]: most European nations in the run-up to World War I had become increasingly ] and were eager to fight. The culpability of Germany was used as a basis to impose reparations on Germany (the amount was repeatedly revised under the ], the ], and the ]). Germany in turn perceived the treaty and especially, Article 231 the paragraph on the German responsibility for the war as a humiliation. For example, there was a nearly total demilitarisation of the armed forces, allowing Germany only six battleships, no submarines, no air force, an army of 100,000 without conscription and no armoured vehicles. The treaty was an important factor in both the social and political conditions encountered by Hitler and his Nazis as they sought power. Hitler and his party used the signing of the treaty by the "November Criminals" as a reason to build up Germany so that it could never happen again. He also used the "November Criminals" as scapegoats, although at the ], these politicians had had very little choice in the matter. | |||

| {{Main|Political views of Adolf Hitler}} | |||

| ] (DAP) membership card]] | |||

| After World War I, Hitler returned to Munich.{{sfn|Bullock|1999|p=61}} Without formal education or career prospects, he remained in the Army.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=109}} In July 1919, he was appointed {{lang|de|Verbindungsmann}} (intelligence agent) of an {{lang|de|Aufklärungskommando}} (reconnaissance unit) of the {{lang|de|]}}, assigned to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the ] (DAP). At a DAP meeting on 12 September 1919, Party Chairman ] was impressed by Hitler's oratorical skills. He gave him a copy of his pamphlet ''My Political Awakening'', which contained anti-Semitic, nationalist, ], and anti-Marxist ideas.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=82}} On the orders of his army superiors, Hitler applied to join the party,{{sfn|Evans|2003|p=170}} and within a week was accepted as party member 555 (the party began counting membership at 500 to give the impression they were a much larger party).{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=75, 76}}{{sfn|Mitcham|1996|p=67}} | |||

| ==Entry into politics== | |||

| {{Main|Adolf Hitler's political views}} | |||

| Hitler made his earliest known written statement about the ] in a 16 September 1919 letter to Adolf Gemlich (now known as the ]). In the letter, Hitler argues that the aim of the government "must unshakably be the removal of the Jews altogether".{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|pp=125–126}} At the DAP, Hitler met ], one of the party's founders and a member of the occult ].{{sfn|Fest|1970|p=21}} Eckart became Hitler's mentor, exchanging ideas with him and introducing him to a wide range of Munich society.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=94, 95, 100}} To increase its appeal, the DAP changed its name to the {{lang|de|Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei}} (] (NSDAP), now known as the "Nazi Party").{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=87}} Hitler designed the party's banner of a ] in a white circle on a red background.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=88}} | |||

| ] (DAP) membership card. His actual membership number was 555 (the 55th member of the party – the 500 was added to make the group appear larger) but later the number was reduced to create the impression that Hitler was one of the founding members.<ref>{{harvnb|Kerhsaw|1999}}</ref> Hitler had wanted to create his own party, but was ordered by his superiors in the Reichswehr to infiltrate an existing one instead.]] | |||

| Hitler was discharged from the Army on 31 March 1920 and began working full-time for the party.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=93}} The party headquarters was in Munich, a centre for anti-government German nationalists determined to eliminate Marxism and undermine the ].{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=81}} In February 1921—already highly effective at ]—he spoke to a crowd of over 6,000.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=89}} To publicise the meeting, two truckloads of party supporters drove around Munich waving swastika flags and distributing leaflets. Hitler soon gained notoriety for his rowdy ] speeches against the Treaty of Versailles, rival politicians, and especially against Marxists and Jews.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=89–92}} | |||

| After World War I, Hitler remained in the army and returned to Munich, where he – in contrast to his later declarations – attended the funeral march for the murdered Bavarian prime minister ].<ref>{{Citation|accessdate=2008-05-22|url=http://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/document/artikel_44676_bilder_value_6_beisetzung-eisners3.jpg|title=1919 Picture of Hitler|publisher=Historisches Lexikon Bayerns}}</ref> After the suppression of the ], he took part in "national thinking" courses organized by the ''Education and Propaganda Department'' (Dept Ib/P) of the Bavarian '']'' Group, Headquarters 4 under Captain ]. Scapegoats were found in "international Jewry", communists, and politicians across the party spectrum, especially the parties of the ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| In July 1919, Hitler was appointed a ''Verbindungsmann'' (police spy) of an ''Aufklärungskommando'' (Intelligence Commando) of the ''Reichswehr'', both to influence other soldiers and to ] a small party, the ] (DAP). During his inspection of the party, Hitler was impressed with founder ]'s ], nationalist, ] and anti-] ideas, which favoured a strong active government, a "non-Jewish" version of socialism and mutual solidarity of all members of society. Drexler was impressed with Hitler's oratory skills and invited him to join the party. Hitler joined DAP on 12 September 1919<ref>{{Citation | last=Stackelberg | first=Roderick | authorlink=Roderick Stackelberg | coauthors= | title=The Routledge companion to Nazi Germany | year=2007 | publisher=Routledge | location=New York, NY | isbn=0-415-30860-7 | page=9}}</ref> and became the party's 55th member.<ref>Samuel W. Mitcham, ''Why Hitler?: the genesis of the Nazi Reich''. Praeger, 1996, p.67</ref> He was also made the seventh member of the executive committee.<ref>Alison Kitson, ''Germany, 1858–1990: Hope, Terror, and Revival'', ], 2001, P.1921</ref> Years later, he claimed to be the party's seventh overall member, but it has been established that this claim is false.<ref>Ian Kershaw, ''Hitler'', Pearson Education, 2000, p.60</ref> | |||

| In June 1921, while Hitler and Eckart were on a fundraising trip to ], a mutiny broke out within the Nazi Party in Munich. Members of its executive committee wanted to merge with the Nuremberg-based ] (DSP).{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=100, 101}} Hitler returned to Munich on 11 July and angrily tendered his resignation. The committee members realised that the resignation of their leading public figure and speaker would mean the end of the party.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=102}} Hitler announced he would rejoin on the condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=103}} The committee agreed, and he rejoined the party on 26 July as member 3,680. Hitler continued to face some opposition within the Nazi Party. Opponents of Hitler in the leadership had ] expelled from the party, and they printed 3,000 copies of a pamphlet attacking Hitler as a traitor to the party.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=103}}{{efn|name=libel suit}} In the following days, Hitler spoke to several large audiences and defended himself and Esser, to thunderous applause. His strategy proved successful, and at a special party congress on 29 July, he was granted absolute power as party chairman, succeeding Drexler, by a vote of 533 to 1.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=83, 103}} | |||

| Here Hitler met ], one of the early founders of the party and member of the occult ].<ref>{{harvnb|Fest|1970}}</ref> Eckart became Hitler's mentor, exchanging ideas with him, teaching him how to dress and speak, and introducing him to a wide range of people. Hitler thanked Eckart by paying tribute to him in the second volume of ''Mein Kampf''. To increase the party's appeal, the party changed its name to the ''Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' or ] (abbreviated NSDAP). | |||

| Hitler's vitriolic beer hall speeches began attracting regular audiences. A ],{{sfn|Kershaw|2000b|p=xv}} he became adept at using populist themes, including the use of ]s, who were blamed for his listeners' economic hardships.{{sfn|Bullock|1999|p=376}}{{sfn|Frauenfeld|1937}}{{sfn|Goebbels|1936}} Hitler used personal magnetism and an understanding of ] to his advantage while engaged in public speaking.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=105–106}}{{sfn|Bullock|1999|p=377}} Historians have noted the hypnotic effect of his rhetoric on large audiences, and of his eyes in small groups.{{sfn|Kressel|2002|p=121}} ], a former member of the Hitler Youth, recalled: | |||

| Hitler was discharged from the army in March 1920 and with his former superiors' continued encouragement began participating full time in the party's activities. By early 1921, Hitler was becoming highly effective at speaking in front of large crowds. In February, Hitler spoke before a crowd of nearly six thousand in Munich. To publicize the meeting, he sent out two truckloads of party supporters to drive around with ]s, cause a commotion and throw out leaflets, their first use of this tactic. Hitler gained notoriety outside of the party for his rowdy, ] speeches against the Treaty of Versailles, rival politicians (including ]s, nationalists and other non-] socialists) and especially against Marxists and Jews. | |||

| {{blockquote|We erupted into a frenzy of nationalistic pride that bordered on hysteria. For minutes on end, we shouted at the top of our lungs, with tears streaming down our faces: {{lang|de|Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil!}} From that moment on, I belonged to Adolf Hitler body and soul.{{sfn|Heck|2001|p=23}}}} | |||

| Early followers included ], former air force ace ], and army captain ]. Röhm became head of the Nazis' paramilitary organisation, the {{lang|de|]}} (SA, "Stormtroopers"), which protected meetings and attacked political opponents. A critical influence on Hitler's thinking during this period was the {{lang|de|]}},{{sfn|Kellogg|2005|p=275}} a conspiratorial group of ] exiles and early Nazis. The group, financed with funds channelled from wealthy industrialists, introduced Hitler to the idea of a Jewish conspiracy, linking international finance with ].{{sfn|Kellogg|2005|p=203}} | |||

| The NSDAP<ref>The party's name was officially changed in 1920 to include the prefix "National Socialist."</ref> was centred in Munich, a hotbed of German nationalists who included Army officers determined to crush Marxism and undermine the Weimar republic. Gradually they noticed Hitler and his growing movement as a suitable vehicle for their goals. Hitler traveled to Berlin to visit nationalist groups during the summer of 1921, and in his absence there was a revolt among the DAP leadership in Munich. | |||

| The programme of the Nazi Party was laid out in their ] on 24 February 1920. This did not represent a coherent ideology, but was a conglomeration of received ideas which had currency in the {{lang|de|]}} ] movement, such as ], opposition to the ], distrust of ], as well as some ] ideas. For Hitler, the most important aspect of it was its strong ] stance. He also perceived the programme as primarily a basis for propaganda and for attracting people to the party.{{sfn|Bracher|1970|pp=115–116}} | |||

| The party was run by an executive committee whose original members considered Hitler to be overbearing. They formed an alliance with a group of socialists from ]. Hitler rushed back to Munich and countered them by tendering his resignation from the party on 11 July 1921. When they realized the loss of Hitler would effectively mean the end of the party, he seized the moment and announced he would return on the condition that he replace Drexler as party chairman, with unlimited powers. Infuriated committee members (including Drexler) held out at first. Meanwhile an anonymous pamphlet appeared entitled ''Adolf Hitler: Is he a traitor?'', attacking Hitler's lust for power and criticizing the violent men around him. Hitler responded to its publication in a Munich newspaper by suing for libel and later won a small settlement. | |||

| === Beer Hall Putsch and Landsberg Prison === | |||

| The executive committee of the NSDAP eventually backed down and Hitler's demands were put to a vote of party members. Hitler received 543 votes for and only one against. At the next gathering on 29 July 1921, Adolf Hitler was introduced as ''Führer'' of the National Socialist German Workers' Party, marking the first time this title was publicly used. | |||

| Hitler's beer hall oratory, attacking Jews, ], ], reactionary monarchists, ] and communists, began attracting adherents. Early followers included ], the former air force pilot ], and the army captain ], who eventually became head of the Nazis' ], the SA ('']'', or "Storm Division"), which protected meetings and attacked political opponents. As well, Hitler assimilated independent groups, such as the ]-based ''Deutsche Werkgemeinschaft'', led by ], who became '']'' of ]. Hitler attracted the attention of local business interests, was accepted into influential circles of Munich society, and became associated with wartime General ] during this time. | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Beer Hall ''Putsch''=== | |||

| {{Main|Beer Hall Putsch}} | {{Main|Beer Hall Putsch}} | ||

| ] trial, 1 April 1924. From left to right: ], ], ], ], ], Hitler, ], ], and ].]] | |||

| ] of {{lang|de|]}}'s 1926–28 edition, which Hitler authored in 1925]] | |||

| In 1923, Hitler enlisted the help of World War I General ] for an attempted coup known as the "]". The Nazi Party used ] as a model for their appearance and policies. Hitler wanted to emulate ]'s "]" of 1922 by staging his own coup in Bavaria, to be followed by a challenge to the government in Berlin. Hitler and Ludendorff sought the support of {{lang|de|Staatskommissar}} (State Commissioner) ], Bavaria's ''de facto'' ruler. However, Kahr, along with Police Chief ] and Reichswehr General ], wanted to install a nationalist dictatorship without Hitler.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=126}} | |||

| On 8 November 1923, Hitler and the SA stormed a public meeting of 3,000 people organised by Kahr in the ], a beer hall in Munich. Interrupting Kahr's speech, he announced that the national revolution had begun and declared the formation of a new government with Ludendorff.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=128}} Retiring to a back room, Hitler, with his pistol drawn, demanded and subsequently received the support of Kahr, Seisser, and Lossow.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=128}} Hitler's forces initially succeeded in occupying the local Reichswehr and police headquarters, but Kahr and his cohorts quickly withdrew their support. Neither the Army nor the state police joined forces with Hitler.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=129}} The next day, Hitler and his followers marched from the beer hall to the ] to overthrow the Bavarian government, but police dispersed them.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=130–131}} ] and four police officers were killed in the failed coup.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|pp=73–74}} | |||

| Encouraged by this early support, Hitler decided to use Ludendorff as a front in an attempted coup later known as the "]" (sometimes as the "Hitler ''Putsch''" or "Munich ''Putsch''"). The Nazi Party had copied Italy's ] in appearance and had adopted some of their policies, and in 1923, Hitler wanted to emulate ] "]" by staging his own "Campaign in Berlin". Hitler and Ludendorff obtained the clandestine support of ], Bavaria's ''de facto'' ruler, along with leading figures in the ''Reichswehr'' and the police. As political posters show, Ludendorff, Hitler and the heads of the Bavarian police and military planned on forming a new government. | |||

| On 8 November 1923, Hitler and the SA stormed a public meeting headed by Kahr in the ], a large beer hall in Munich. He declared that he had set up a new government with Ludendorff and demanded, at gunpoint, the support of Kahr and the local military establishment for the destruction of the Berlin government.<ref>{{harvnb|Shirer|1961|pp=104–106}}</ref> Kahr withdrew his support and fled to join the opposition to Hitler at the first opportunity.<ref>{{harvnb|Shirer|1961|p=109}}</ref> The next day, when Hitler and his followers marched from the beer hall to the ] to overthrow the Bavarian government as a start to their "March on Berlin", the police dispersed them. ] were killed.<ref>{{harvnb|Shirer|1961|pp=111–113}}</ref> | |||

| Hitler fled to the home of ] and contemplated suicide. He was soon arrested for ]. ] became temporary leader of the party. During Hitler's trial, he was given almost unlimited time to speak, and his popularity soared as he voiced nationalistic sentiments in his A Munich personality became a nationally known figure. On 1 April 1924, Hitler was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at ]. Hitler received favoured treatment from the guards and had much fan mail from admirers. He was pardoned and released from jail on 20 December 1924, by order of the Bavarian Supreme Court on 19 December, which issued its final rejection of the state prosecutor's objections to Hitler's early release.<ref>''Kershaw'' p. 239.</ref> Including time on remand, he had served little more than one year of his sentence.<ref name="bull121">{{harvnb|Bullock|1962|p=121}}</ref> | |||

| On 28 June 1925, Hitler wrote a letter from ] to the editor of '']'' in New York City stating how long he had been in prison at "Sandberg a. S." and how much his privileges had been revoked.<ref>] ''The Nation 1865–1990'', p. 66, Thunder's Mouth Press, 1990 ISBN 1-56025-001-1</ref> | |||

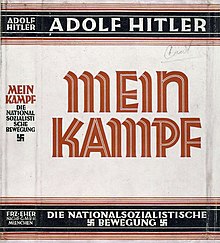

| ===''Mein Kampf''=== | |||

| {{Main|Mein Kampf}} | |||

| ] of '']'']] | |||

| While at Landsberg he dictated most of the first volume of ''Mein Kampf'' (''My Struggle'', originally entitled ''Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice'') to his deputy ].<ref name="bull121"/> The book, dedicated to Thule Society member ], was an autobiography and an exposition of his ideology. Mein Kampf was influenced by '']'' by ] which Hitler called "my Bible."<ref>{{Citation | title = Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant'' | url = http://books.google.com/?id=4NoE2VyfN70C&pg=PA357 | author =Jonathan Peter Spiro | publisher = Univ. of Vermont Press | accessdate = 2010-01-25 | isbn = 9781584657156 | date = 2008-12-31}}</ref> It was published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, selling about 240,000 copies between 1925 and 1934. By the end of the war, about 10 million copies had been sold or distributed (newlyweds and soldiers received free copies). | |||

| Hitler spent years dodging taxes on the royalties of his book and had accumulated a tax debt of about 405,500 ] (€6 million in today's money) by the time he became chancellor (at which time his debt was waived).<ref name="taxes">{{Citation|accessdate=2008-05-22|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4105683.stm|title=Hitler dodged taxes, expert finds | |||

| |publisher=BBC|date=2004-12-17}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|accessdate=2008-05-22|url=http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/0,1518,433526,00.html|title=Mythos Ladenhüter|work=]|date=2006-08-25|author=Hinrichs, Per|language=German|publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| Hitler fled to the home of ] and by some accounts contemplated suicide.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=132}} He was depressed but calm when arrested on 11 November 1923 for ].{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|p=131}} His trial before the special ] in Munich began in February 1924,{{sfn|Munich Court, 1924}} and ] became temporary leader of the Nazi Party. On 1 April, Hitler was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at ].{{sfn|Fulda|2009|pp=68–69}} There, he received friendly treatment from the guards, and was allowed mail from supporters and regular visits by party comrades. Pardoned by the Bavarian Supreme Court, he was released from jail on 20 December 1924, against the state prosecutor's objections.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=239}} Including time on remand, Hitler served just over one year in prison.{{sfn|Bullock|1962|p=121}} | |||

| The ] of ''Mein Kampf'' in Europe is claimed by the Free State of Bavaria and scheduled to end on 31 December 2015. Reproductions in Germany are authorized only for scholarly purposes and in heavily commented form. The situation is, however, unclear. Historian Werner Maser, in an interview with ] has stated that Peter Raubal, son of Hitler's nephew, ], would have a strong legal case for winning the copyright from Bavaria if he pursued it. Raubal has stated he wants no part of the rights to the book, which could be worth millions of euros.<ref>{{Citation|accessdate=2008-05-22|url=http://www.fpp.co.uk/Hitler/MeinKampf/Raubal.html|title=Hitler Relative Eschews Royalties|publisher=Reuters|date=2004-05-25}}</ref> The uncertain status has led to contested trials in Poland and Sweden. ''Mein Kampf'', however, is published in the U.S., as well as in other countries such as ] and ], by publishers with various political positions. | |||

| While at Landsberg, Hitler dictated most of the first volume of '']'' ({{Literal translation|My Struggle}}); originally titled ''Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice'') at first to his chauffeur, ], and then to his deputy, ].{{sfn|Bullock|1962|p=121}}{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|page=147}} The book, dedicated to Thule Society member Dietrich Eckart, was an autobiography and exposition of his ideology. The book laid out Hitler's plans for transforming German society into one based on race. Throughout the book, Jews are equated with "germs" and presented as the "international poisoners" of society. According to Hitler's ideology, the only solution was their extermination. While Hitler did not describe exactly how this was to be accomplished, his "inherent genocidal thrust is undeniable", according to ].{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=148–150}} | |||

| ===Rebuilding of the party=== | |||

| ] at a Nazi rally in ], 1928]] | |||

| Published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, {{lang|de|Mein Kampf}} sold 228,000 copies between 1925 and 1932. One million copies were sold in 1933, Hitler's first year in office.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|pp=80–81}} Shortly before Hitler was eligible for parole, the Bavarian government attempted to have him deported to Austria.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=237}} The Austrian federal chancellor rejected the request on the specious grounds that his service in the German Army made his Austrian citizenship void.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=238}} In response, Hitler formally renounced his Austrian citizenship on 7 April 1925.{{sfn|Kershaw|1999|p=238}} | |||

| At the time of Hitler's release, the political situation in Germany had calmed and the economy had improved, which hampered Hitler's opportunities for agitation. Though the "Hitler ''Putsch''" had given Hitler some national prominence, his party's mainstay was still Munich. | |||

| === Rebuilding the Nazi Party === | |||

| The NSDAP and its organs were banned in Bavaria after the collapse of the putsch. Hitler convinced ], Prime Minister of Bavaria, to lift the ban, based on representations that the party would now only seek political power through legal means. Even though the ban on the NSDAP was removed effective 16 February 1925,<ref>See ] for details.</ref> Hitler incurred a new ban on public speaking as a result of an inflammatory speech. Since Hitler was banned from public speeches, he appointed ], who in 1924 had been elected to the '']'', as ''Reichsorganisationsleiter'', authorizing him to organize the party in northern Germany. Strasser, joined by his younger brother ] and ], steered an increasingly independent course, emphasizing the socialist element in the party's programme. The ''Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Gauleiter Nord-West'' became an internal opposition, threatening Hitler's authority, but this faction was defeated at the ] in 1926, during which Goebbels joined Hitler. | |||

| At the time of Hitler's release from prison, politics in Germany had become less combative and the economy had improved, limiting Hitler's opportunities for political agitation. As a result of the failed Beer Hall Putsch, the Nazi Party and its affiliated organisations were banned in Bavaria. In a meeting with the Prime Minister of Bavaria, ], on 4 January 1925, Hitler agreed to respect the state's authority and promised that he would seek political power only through the democratic process. The meeting paved the way for the ban on the Nazi Party to be lifted on 16 February.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=158, 161, 162}} | |||

| After this encounter, Hitler centralized the party even more and asserted the '']'' ("Leader principle") as the basic principle of party organization. Leaders were not elected by their group but were rather appointed by their superior and were answerable to them while demanding unquestioning obedience from their inferiors. Consistent with Hitler's disdain for democracy, all power and authority devolved from the top down. | |||

| However, after an inflammatory speech he gave on 27 February, Hitler was barred from public speaking by the Bavarian authorities, a ban that remained in place until 1927.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=162, 166}}{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=129}} To advance his political ambitions in spite of the ban, Hitler appointed ], ], and ] to organise and enlarge the Nazi Party in northern Germany. Gregor Strasser steered a more independent political course, emphasising the socialist elements of the party's programme.{{sfn|Kershaw|2008|pp=166, 167}} | |||

| A key element of Hitler's appeal was his ability to evoke a sense of offended national pride caused by the Treaty of Versailles imposed on the defeated ] by the Western Allies. Germany had lost economically important territory in Europe along with its colonies and in admitting to sole responsibility for the war had agreed to pay a huge ] bill totaling 132 billion ]. Most Germans bitterly resented these terms, but early Nazi attempts to gain support by blaming these humiliations on "international Jewry" were not particularly successful with the electorate. The party learned quickly, and soon a more subtle propaganda emerged, combining antisemitism with an attack on the failures of the "Weimar system" and the parties supporting it. | |||

| The stock market in the United States ]. The impact in Germany was dire: millions became unemployed and several major banks collapsed. Hitler and the Nazi Party prepared to take advantage of the emergency to gain support for their party. They promised to repudiate the Versailles Treaty, strengthen the economy, and provide jobs.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|pp=136–137}} | |||

| Having failed in overthrowing the Republic by a coup, Hitler pursued a "strategy of legality": this meant formally adhering to the rules of the Weimar Republic until he had legally gained power. He would then use the institutions of the Weimar Republic to destroy it and establish himself as dictator. Some party members, especially in the paramilitary SA, opposed this strategy; Röhm and others ridiculed Hitler as "''Adolphe Legalité''". | |||

| ==Rise to power== | == Rise to power == | ||

| {{Main|Adolf Hitler's rise to power}} | {{Main|Adolf Hitler's rise to power}} | ||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable plainrowheaders sortable" style="text-align: center;" | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |+ Nazi Party |

|+ Nazi Party election results{{sfn|Kolb|2005|pp=224–225}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="col" | Election | |||

| ! Date | |||

| ! scope="col" | Total votes | |||

| ! Votes | |||

| ! scope="col" | % votes | |||

| ! Percentage | |||

| ! |

! scope="col" | Reichstag seats | ||

| ! scope="col" class="unsortable" | Notes | |||

| ! Background | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ |

! scope="row" | {{dts|1 May 1924|format=hide}}] | ||

| | {{Number table sorting|1918300}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|6.5}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|6.5}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|32}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|32}} | |||

| | Hitler in prison | | style="text-align:left;" | Hitler in prison | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ |

! scope="row" | {{dts|1 December 1924|format=hide}}] | ||

| | {{Number table sorting|907300}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|3.0}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|3.0}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|14}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|14}} | |||

| | |

| style="text-align:left;" | Hitler released from prison | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |{{dts|1 May 1928|format=hide}}] | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|810100}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|2.6}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|2.6}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|12}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|12}} | |||

| | | | style="text-align:left;" | | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ |

! scope="row" | {{dts|1 September 1930|format=hide}}] | ||

| | {{Number table sorting|6409600}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|18.3}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|18.3}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|107}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|107}} | |||

| | After the financial crisis | | style="text-align:left;" | After the financial crisis | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ |

! scope="row" | {{dts|1 July 1932|format=hide}}] | ||

| | {{Number table sorting|13745000}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|13745800}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|37.3}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|37.4}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|230}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|230}} | |||

| | After Hitler was candidate for presidency | | style="text-align:left;" | After Hitler was candidate for presidency | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ |

! scope="row" | {{dts|1 November 1932|format=hide}}] | ||

| | {{Number table sorting|11737000}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|33.1}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|33.1}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|196}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|196}} | |||

| | | | style="text-align:left;"| | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ |

! scope="row" | {{dts|1 March 1933|format=hide}}] | ||

| | {{Number table sorting|17277180}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|17277000}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|43.9}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|43.9}} | |||

| | {{Number table sorting|288}} | |||

| | style="text-align:right;"| {{nts|288}} | |||

| | |

| style="text-align:left;" | Only partially free during Hitler's term as chancellor of Germany | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| ===Brüning |

=== Brüning administration === | ||

| ] meeting in December 1930, with Hitler in the centre]] | |||

| The |

The ] provided a political opportunity for Hitler. Germans were ambivalent about the ], which faced challenges from ] and ]. The moderate political parties were increasingly unable to stem the tide of extremism, and the ] helped to elevate Nazi ideology.{{sfn|Kolb|1988|p=105}} The elections of September 1930 resulted in the break-up of a ] and its replacement with a minority cabinet. Its leader, chancellor ] of the ], governed through ] from President ]. Governance by decree became the new norm and paved the way for authoritarian forms of government.{{sfn|Halperin|1965|p=403 ''et. seq''}} The Nazi Party rose from obscurity to win 18.3 per cent of the vote and 107 parliamentary seats in the 1930 election, becoming the second-largest party in parliament.{{sfn|Halperin|1965|pp=434–446 ''et. seq''}} | ||

| ] at the dedication of the renovation of the Palais Barlow on ] in Munich into the ] headquarters, December 1930]] | |||

| The ''Reichstag''{{'}}s initial opposition to Brüning's measures led to premature elections in September 1930. The republican parties lost their majority and their ability to resume the grand coalition, while the Nazis suddenly rose from relative obscurity to win 18.3% of the vote along with 107 seats. In the process, they jumped from the ninth-smallest party in the chamber to the second largest.<ref>{{Harvnb|Halperin|1965|pages=434–446 ''et. seq.''}}</ref> | |||

| Hitler made a prominent appearance at the trial of two Reichswehr officers, Lieutenants Richard Scheringer and ], in late 1930. Both were charged with membership in the Nazi Party, at that time illegal for Reichswehr personnel.{{sfn|Wheeler-Bennett|1967|p=218}} The prosecution argued that the Nazi Party was an extremist party, prompting defence lawyer Hans Frank to call on Hitler to testify.{{sfn|Wheeler-Bennett|1967|p=216}} On 25 September 1930, Hitler testified that his party would pursue political power solely through democratic elections,{{sfn|Wheeler-Bennett|1967|pp=218–219}} which won him many supporters in the officer corps.{{sfn|Wheeler-Bennett|1967|p=222}} | |||

| Brüning's measures |

Brüning's austerity measures brought little economic improvement and were extremely unpopular.{{sfn|Halperin|1965|p=449 ''et. seq''}} Hitler exploited this by targeting his political messages specifically at people who had been affected by the inflation of the 1920s and the Depression, such as farmers, war veterans, and the middle class.{{sfn|Halperin|1965|pp=434–436, 471}} | ||

| In September 1931, Hitler's niece ] was found dead in her bedroom in his Munich apartment (his half-sister ] and her daughter Geli had been with him in Munich since 1929), an apparent suicide. Geli, who was believed to be in some sort of romantic relationship with Hitler, was 19 years younger than he was and had used his gun. His niece's death is viewed as a source of deep, lasting pain for him.<ref>{{harvnb|Bullock|1962|pp=393–394}}</ref> | |||

| Although Hitler had terminated his Austrian citizenship in 1925, he did not acquire German citizenship for almost seven years. This meant that he was ], legally unable to run for public office, and still faced the risk of deportation.{{sfn|Shirer|1960|p=130}} On 25 February 1932, the interior minister of ], ], who was a member of the Nazi Party, appointed Hitler as administrator for the state's delegation to the ] in Berlin, making Hitler a citizen of Brunswick,{{sfn|Hinrichs|2007}} and thus of Germany.{{sfn|Halperin|1965|p=476}} | |||