| Revision as of 17:15, 26 February 2007 view sourceAzim7 (talk | contribs)3 edits →Hindu temple desecration← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:11, 22 January 2025 view source Tamjeed Ahmed (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users941 edits Emperor of India should be correctTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Mughal emperor from 1658 to 1707}} | |||

| {| cellpadding=3px cellspacing=0px class="toccolours" style="width:320px;float:right; border:1px #CCCCCC solid; margin:5px" | |||

| {{About|the sixth Mughal emperor|the Indian movie of the same name|Aurangzeb (film)}} | |||

| |+ <big>'''Aurangzeb'''</big> | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| |colspan=2 align=center style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"| | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use Indian English|date=April 2018}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | |||

| | name = Alamgir I | |||

| | title = {{transliteration|fa|]{{efn|English: The Honorable, Generous}} }}<br/><!-- | |||

| -->{{transliteration|fa|]<ref name=Aurangzeb>{{cite web |title=Tomb of Aurangzeb |url=http://www.asiaurangabad.in/pdf/Tourist/Tomb_of_Aurangzeb-_Khulatabad.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923175254/http://www.asiaurangabad.in/pdf/Tourist/Tomb_of_Aurangzeb-_Khulatabad.pdf |archive-date=23 September 2015 |access-date=21 March 2015 |publisher=ASI Aurangabad}}</ref>}}<br/><!-- | |||

| -->{{transliteration|ar|]{{efn|English: Commander of the Faithful}} }}<br/><!-- | |||

| -->]<br /><!-- | |||

| -->(Emperor of the Sultanate of India)<ref name=Aurangzeb/> | |||

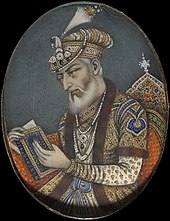

| | image = Aurangzeb-portrait.jpg | |||

| | caption = Portrait by ], {{circa|1660}} | |||

| | succession = ] | |||

| | reign = 31 July 1658{{snd}}3 March 1707 | |||

| | reign-type = | |||

| | coronation = 31 July 1658{{efn|A second coronation was held on 5 June 1659}} | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | reg-type = '']'' | |||

| | regent = {{Collapsible list|title=''See list'' | |||

| |Fazil Khan | |||

| |Jafar Khan | |||

| |]}} | |||

| {{Collapsed infobox section begin |cont = yes |Other governmental responsibilities |titlestyle = border:1px dashed lightgrey;}}{{Infobox royalty |embed=yes | |||

| | succession1 = ]{{efn|The unified province of Deccan included the governorates of ], ], ], ], ] and ]}} | |||

| | reign1 = November 1653 – 5 February 1658 | |||

| | reign-type1 = | |||

| | regent1 = | |||

| | reg-type1 = | |||

| | cor-type1 = ] | |||

| | coronation1 = ] | |||

| | predecessor1 = ] | |||

| | successor1 = | |||

| | reign2 = 14 July 1636 – 28 May 1644 | |||

| | reign-type2 = | |||

| | regent2 = | |||

| | reg-type2 = | |||

| | cor-type2 = ] | |||

| | coronation2 = ] | |||

| | predecessor2 = ''Position established'' | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | succession3 = ] | |||

| | reign3 = November 1648 – 14 July 1652 | |||

| | reign-type3 = | |||

| | regent3 = Mughal Khan<br>Zafar Khan | |||

| | reg-type3 = ] | |||

| | cor-type3 = ] | |||

| | coronation3 = ] | |||

| | predecessor3 = Mughal Khan | |||

| | successor3 = Sardar Khan Shahjahani | |||

| | succession4 = ] | |||

| | reign4 = March 1648 – 14 July 1652 | |||

| | reign-type4 = | |||

| | regent4 = | |||

| | reg-type4 = | |||

| | cor-type4 = ] | |||

| | coronation4 = ] | |||

| | predecessor4 = Saeed Khan Bahadur | |||

| | successor4 = Bahadur Khan Rohilla | |||

| | succession5 = ] | |||

| | reign5 = 21 January 1647 – 1 October 1647 | |||

| | reign-type5 = | |||

| | regent5 = | |||

| | reg-type5 = | |||

| | cor-type5 = ] | |||

| | coronation5 = ] | |||

| | predecessor5 = ] | |||

| | successor5 = ''Position abolished'' | |||

| | succession6 = ] | |||

| | reign6 = 21 January 1647 – 1 October 1647 | |||

| | reign-type6 = | |||

| | regent6 = | |||

| | reg-type6 = | |||

| | cor-type6 = ] | |||

| | coronation6 = ] | |||

| | predecessor6 = ] | |||

| | successor6 = ''Position abolished'' | |||

| | succession7 = ] | |||

| | reign7 = 16 February 1645 – January 1647 | |||

| | reign-type7 = | |||

| | regent7 = | |||

| | reg-type7 = | |||

| | cor-type7 = ] | |||

| | coronation7 = ] | |||

| | predecessor7 = ] | |||

| | successor7 = ] | |||

| {{Collapsed infobox section end}} }} | |||

| | birth_name = Muhi al-Din Muhammad | |||

| | birth_date = 3 November 1618<ref name="c639">{{cite web | title=Aurangzeb | website=Wikidata | date=2017-10-09 | url=https://m.wikidata.org/Q485547 | access-date=2024-07-10}}</ref> | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ]<br>(modern-day ], India) | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1707|03|03|1618|11|03|df=y}} | |||

| | death_place = ], ], Mughal Empire<br>(modern-day ], India) | |||

| | issue = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | issue-link = #Family | |||

| | issue-pipe = ''Detail'' | |||

| | full name = | |||

| | posthumous name = | |||

| | house = ] | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | signature = File:Seal detail, from- Painted seal of Mughal Emperor Awrangzib Wellcome L0034099 (cropped).jpg | |||

| | signature_type = ] | |||

| | religion = ]{{efn|School of Thought: ]}} | |||

| | dynasty = ] | |||

| | spouse-type = Consort | |||

| | spouses = {{ubl| | |||

| | {{marriage|]|1637|1657|end=died}} | |||

| | {{marriage|]|1638|1691|end=died}} | |||

| | ] <br />({{Abbr|d.|death}} 1688) | |||

| | ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | spouses-type = Spouse | |||

| | burial_place = ], ], Maharashtra, India | |||

| | module = {{Infobox military person | embed=yes | |||

| | allegiance = {{flagicon image|Shah Jahan Flag.png|border=}} ] | |||

| | branch = {{flagicon image|Shah Jahan Flag.png|border=}} ] | |||

| | commands = {{collapsible list|title = {{nobold|''See list''}}|]|]{{efn|The unified province of Deccan included the governorates of ], ], ], ], ] and ]}}|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | battles_label = | |||

| | battles = {{collapsible list|title = {{nobold|''See list''}}|{{tree list}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| |colspan=2 align=center style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"| | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Birth name:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|Abu Muzaffar Muhiuddin Muhammad Aurangzeb Alamgir | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Family name:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |- | |||

| *** ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Title:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|] of ]<br /> | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Birth:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|], ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |- | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Birthplace:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"| ], ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Death:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|], ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Succeeded by:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |- | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Marriage:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"| | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Muhi al-Din Muhammad''' (3 November 1618 – 3 March 1707), commonly known by the title '''Aurangzeb''',{{efn|{{IPA|fa|ʔaw.ɾaŋɡ.ˈzeːb}} {{lit|Ornament of the Throne}}; Awrangzīb}} and also by his ] '''Alamgir I''',{{efn|{{IPA|fa|ʔɑː.ˈlam.ˈɡiːɾ}} {{lit|Conqueror of the World}}}}{{efn|Which is derived from his title, Abu al-Muzaffar Muhi-ad-Din Muhammad Bahadur Alamgir Aurangzeb Badshah al-Ghazi.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Khomdan Singh Lisam |title=Encyclopaedia Of Manipur (3 Vol.) |date=2011 |publisher=Gyan Publishing House |isbn=9788178358642 |page=706 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z6d-IyINtk4C |access-date=20 March 2024 |language=En |quote=... Aurangzeb Bahadur Alamgir I ( Conqueror of the Universe ) , more commonly known as Aurangzeb , the 6th Mughal Emperor ruled from 1658 to}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Gul Rahim Khan |title=Silver Coins Hoard of the Late Mughals from Kohat |journal=Ancient Pakistan |date=2021 |volume=18 |page=16 |url= |publisher=Department of Archaeology, ] |language=en |issn=2708-4590 |quote=In gold there is no more type. In silver some other types like Abu al Muzaffar Muhiuddin/ Muhammad (and date) / Bahadur Alamgir/ Aurangzeb/ Badshah Ghazi or ...}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy Volume 3 |date=1893 |publisher=Harvard University; Royal Irish Academy |page=398 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ru4AAAAAYAAJ |access-date=20 March 2024 |language=En |quote=The Emperor's name and title were proclaimed in the pulpit as Abu al-Muzaffar Bahadur ' Alamgir Badshah i Ghazi}}</ref>}} was the sixth ], reigning from 1658 until his death in 1707. Under his reign, the ] reached its greatest extent, with territory spanning nearly the entirety of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Chapra |first1=Muhammad Umer |title=Morality and Justice in Islamic Economics and Finance |date=2014 |publisher=Edward Elgar Publishing |isbn=978-1-78347-572-8 |pages=62–63 |quote=Aurangzeb (1658–1707). Aurangzeb's rule, spanning a period of 49 years}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Bayly |first1=C.A. |title=Indian society and the making of the British Empire |date=1990 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-38650-0 |edition=1st pbk. |location=Cambridge |page=7}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Turchin |first1=Peter |last2=Adams |first2=Jonathan M. |last3=Hall |first3=Thomas D |date=December 2006 |title=East-West Orientation of Historical Empires |url=http://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/jwsr/article/view/369/381 |journal=Journal of World-Systems Research |volume=12 |issue=2 |page=223 |issn=1076-156X |access-date=12 September 2016}}</ref><ref name="borocz">{{cite book |author=József Böröcz |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d0SPAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA21 |title=The European Union and Global Social Change |date=2009 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-135-25580-0 |page=21 |author-link=József Böröcz |access-date=26 June 2017}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |align=left style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"|'''Children:'''||style="border-top:1px #CCCCCC solid"| | |||

| *], son | |||

| *], son | |||

| *], son | |||

| *], son | |||

| *], daughter | |||

| |} | |||

| Aurangzeb and the Mughals belonged to a branch of the ]. He held administrative and military posts under his father ] ({{Reign|1628|1658}}) and gained recognition as an accomplished military commander. Aurangzeb served as the viceroy of the ] in 1636–1637 and the governor of ] in 1645–1647. He jointly administered the provinces of ] and ] in 1648–1652 and continued expeditions into the neighboring ] territories. In September 1657, Shah Jahan nominated his eldest and liberalist son ] as his successor, a move repudiated by Aurangzeb, who proclaimed himself emperor in February 1658. In April 1658, Aurangzeb defeated the allied army of Shikoh and the ] at the ]. Aurangzeb's decisive victory at the ] in May 1658 cemented his sovereignty and his suzerainty was acknowledged throughout the Empire. After Shah Jahan recovered from illness in July 1658, Aurangzeb declared him incompetent to rule and imprisoned his father in the ]. | |||

| '''Aurangzeb''' ({{lang-fa|اورنگزیب}}, {{lang-en|Onetime Adorning the Crown}}) (], ] – ], ]), also known as '''Alamgir I''', was the ruler of the ] from 1658 until 1707. He was the sixth Mughal ruler after Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan. Aurangzeb was remarkably pious and zealous. Strict adherence to ] and ] (Islamic law)—as he interpreted them—were the foundations of his reign. He codified and instituted Sharia law throughout the empire, abandoning the religious tolerance of his predecessors. During his reign, allegedly many ] temples were defaced and destroyed, and many non-Muslims converted to ], both by inducement and by force.<ref>{{cite book | last = Richards | first = John F. | title = The Mughal Empire | year = 1995 | publisher = Cambridge University Press | location = Cambridge | id = ISBN 0-521-56603-7 | pages = 130,177 | quote =Jujhar Singh's outright defiance of this order inflamed Shah Jahan. He sent another large army under the nominal command of the sixteen-year-old Prince Aurangzeb to invade Bundelkhand....When overtaken by Mughal troops, Jujhar Singh's principal queens were killed by their attendants, but the remaining royal women were sent to join the Mughal harem. ''Two very young sons and a grandson were converted to Islam. Another older son who refused to convert was killed outright.''}}</ref> The ], a head tax on non-Muslims, was reinstated during his rule. | |||

| Aurangzeb's reign is characterized by a period of rapid military expansion, with several dynasties and states being overthrown by the Mughals. The Mughals also surpassed ] as the world's largest economy and biggest manufacturing power. The Mughal military gradually improved and became one of the strongest armies in the world. A staunch Muslim, Aurangzeb is credited with the construction of numerous mosques and patronizing works of ]. He successfully imposed the ''Fatawa-i Alamgiri'' as the principal regulating body of the empire and prohibited religiously ] activities in Islam. Although Aurangzeb suppressed several local revolts, he maintained cordial relations with foreign governments. | |||

| Aurangzeb ruled India for 48 years. He expanded the Mughal Empire to its greatest extent, encompassing all but the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent. His constant policies of war, however, left the empire dangerously overextended, isolated from its strong ] allies, and with a population that (except for the Muslim minority) expressed resentment, if not outright rebellion, to his reign. | |||

| Aurangzeb was the longest reigning Mughal Emperor. His empire was also one of the largest in Indian history. However, his emperorship has a complicated legacy.<ref>{{cite book | last1=Ali | first1=A. | last2=Thiam | first2=I.D. | last3=Talib | first3=Y.A. | title=The Different aspects of Islamic culture: Islam in the World today; Retrospective of the evolution of Islam and the Muslim world | publisher=UNESCO Publishing | year=2016 | isbn=978-92-3-100132-1 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RMh7DQAAQBAJ&pg=PA51 | page=51}}</ref> His critics, citing his actions against the non-Muslims and his conservative view of Islam, argue that he abandoned the legacy of pluralism and tolerance of the earlier Mughal emperors. Others, however, reject these assertions, arguing that he opposed bigotry against Hindus, Sikhs and Shia Muslims and that he employed significantly more Hindus in his imperial bureaucracy than his predecessors. | |||

| He remains one of the most controversial figures in Indian history. His religious policies continue to inspire conflict between religious and political groups in India, Pakistan and elsewhere. He is generally regarded as the last great Mughal ruler. His successors, the 'Later Mughals', lacked his strong hand and the Hindu ] mostly replaced Mughal rule during the rest of the 18th century. | |||

| == |

==Early life== | ||

| ], ], their father ] (center), and maternal grandfather ] (right) c.1628]] | |||

| ===Early life=== | |||

| Aurangzeb was born in ] on 3 November 1618.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Bibb |first1=Sheila C. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N98eEAAAQBAJ&dq=aurangzeb+4+november+1618&pg=PA32 |title=Framing the Apocalypse: Visions of the End-of-Times |last2=Simon-López |first2=Alexandra |year=2019 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-39944-0 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Aurangzeb |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aurangzeb |access-date=6 April 2016 |author-link=Percival Spear |last1=Spear |first1=Percival}}</ref><ref name="Thackeray248">{{cite book |title=Events that formed the modern world: from the European Renaissance through the War on Terror |url=https://archive.org/details/eventsthatformed0005unse |url-access=registration |year=2012 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-59884-901-1 |editor-last1=Thackeray |editor-first1=Frank W. |location=Santa Barbara, Calif. |page=248 |editor-last2=Findling |editor-first2=John E.}}</ref> His father was ] ] ({{Reign|1628|1658}}), who hailed from the ] of the ].<ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Waseem |editor-first=M. |year=2003 |title=On Becoming an Indian Muslim: French Essays on Aspects of Syncretism |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=New Delhi |page=103 |isbn=978-0-19-565807-1}}</ref> The latter was descended from Emir ] ({{Reign|1370|1405}}), the founder of the ].{{sfn|Mukerjee|2001|p=23}}{{sfn|Sarkar|1912|p=61}} Aurangzeb's mother ] was the daughter of the Persian nobleman ], who was the youngest son of vizier ].{{sfn|Tillotson|2008|p=194}} Aurangzeb was born during the reign of his patrilineal grandfather ] ({{Reign|1605|1627}}), the fourth emperor of the ]. | |||

| Aurangzeb (full name: ''Abu Muzaffar Muhiuddin Muhammad Aurangzeb Alamgir'' --]: ابو مظفر محی الدین محمد اورنگزیب عالمگیر) was the third son of the fifth great ] emperor ] (builder of the ]) and Arjumand Bānū Begum (also known as ]). After a rebellion by his father, part of Aurangzeb's childhood was spent as a virtual hostage at his grandfather ]'s court. | |||

| In June 1626, after an unsuccessful rebellion by his father, eight-year-old Aurangzeb and his brother ] were sent to the Mughal court in ] as hostages of their grandfather Jahangir and his wife, ], as part of their father's pardon deal.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Eaton|first=Richard M.|title=India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765|publisher=University of California Press|year=2019|isbn=978-0-520-97423-4|page=251|oclc=1243310832}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Gandhi |first=Supriya |year=2020 |title=The emperor who never was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |publisher=Belknap Press |pages=52–53 |isbn=978-0-674-98729-6|oclc=1112130290 }}</ref> After Jahangir died in 1627, Shah Jahan emerged victorious in the ensuing war of succession to the Mughal throne. Aurangzeb and his brother were consequently reunited with Shah Jahan in ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Gandhi|first=Supriya |year=2020 |title=The emperor who never was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |publisher=Belknap Press |pages=59–62 |isbn=978-0-674-98729-6|oclc=1112130290 }}</ref> | |||

| After Jahangir's death in ], Aurangzeb returned to live with his parents. Shah Jahan followed the Mughal practice of assigning authority to his sons, and in ] made Aurangzeb ] (governor) of the ]. He moved to Kirki, which in time he renamed ]. In ], he married Rabia Daurrani. During this period the Deccan was relatively peaceful. In the Mughal court, however, Shah Jahan began to show greater and greater favoritism to his eldest son ]. | |||

| As a Mughal prince, Aurangzeb received an education covering subjects like combat, military strategy, and administration. His curriculum also included areas like Islamic studies, ] and ]. Aurangzeb grew up fluent in the ]. He was also fluent in his ancestral language of ], but similar to his predecessors, he preferred to use ].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Truschke|first=Audrey|title=Aurangzeb: the life and legacy of India's most controversial king|date=2017|publisher=Stanford University Press|isbn=978-1-5036-0259-5|location=Stanford, California|pages=17–18|oclc=962025936}}</ref><ref name=":5">{{Cite book |last=Streusand |first=Douglas E. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/191926598 |title=Islamic gunpowder empires: Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals |date=2011 |publisher=Westview Press |isbn=978-0-8133-1359-7 |location=Boulder, Colo |pages=281–282 |oclc=191926598}}</ref> | |||

| In ], Aurangzeb's sister ] was accidentally burned in ]. This event precipitated a family crisis which had political consequences. Aurangzeb suffered his father's displeasure when returning to Agra three weeks after the event, instead of returning immediately on hearing of the accident. Shah Jahan dismissed him as the governor of Deccan. Aurangzeb later claimed (]) he had resigned in protest of his father favoring Dara. | |||

| On 28 May 1633, a ] stampeded through the Mughal imperial encampment. Aurangzeb rode against the elephant and threw his spear at its head. He was unhorsed but escaped death. For his courage, Aurangzeb's father conferred on him the title of '']'' (brave) and presented him with gifts. When chided for his recklessness, Aurangzeb replied:{{sfn|Sarkar|1912|pp=10–12}} | |||

| Aurangzeb's fortunes continued to decline. In ], he was barred from the court for seven months. Later, Shah Jahan appointed him governor of ]. He performed well and was rewarded. In ], Shah Jahan made him governor of ] and ] (near modern ] and ]), replacing Aurangzeb's ineffective brother ]. These areas were at the time under attack from a various forces. Aurangzeb's military skill proved successful, and the story of how he spread his prayer rug and prayed in the midst of battle brought him much fame. | |||

| {{blockquote|If the fight had ended fatally for me it would not have been a matter of shame. Death drops the curtain even on emperors; it is no dishonor. The shame lay in what my brothers did!}} | |||

| He was appointed governor of ] alongside Osman Junaid and ] and began a protracted military struggle against the ] army in an effort to capture the city of ]. He failed, and fell again into his father's disfavor. | |||

| Historians have interpreted this as an unjust slur against his brothers. Shuja had also faced the elephant and wounded it with his spear. Dara had been too far away to come to their assistance.{{sfn|Sarkar|1912|pp=11–12}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Hansen |first=Waldemar |title=The Peacock Throne: The Drama of Mogul India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AV--abKg9GEC&pg=PA122 |access-date=23 November 2012 |year=1996 |orig-date=1972 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |isbn=978-81-208-0225-4 |pages=122–124}}</ref> | |||

| In ], Aurangzeb was re-appointed governor of the ]. But both man and place had changed. The Deccan produced poor tax revenue for the Mughals. In his previous term, Aurangzeb ignored the problem, allowing state-sanctioned corruption and extortion to grow. This time Aurangzeb set about reforming the system, but his efforts often placed additional burdens on the locals and were poorly received. | |||

| Three days later Aurangzeb turned fifteen. Shah Jahan weighed him and presented him with his weight in gold along with other presents worth Rs. 200,000. His bravery against the elephant was documented in Persian and ] verses.{{sfn|Sarkar|1912|p=12}} | |||

| It was during this second governorship that Aurangzeb first recounts destroying a ] temple. In addition, Aurangzeb's officers began treating non-Muslims harshly, and he defended these practices in letters to Shah Jahan's court. The practices would become themes in Aurangzeb's rule as emperor. | |||

| === Career as prince === | |||

| In an effort to raise additional revenues, Aurangzeb attacked the border kingdoms of ] (]), and ] (]). Both times, Shah Jahan called off the attacks near the moment of Aurangzeb's triumph. Even at the time it was believed that the withdrawals had been ordered by Prince Dara, in Shah Jahan's name. | |||

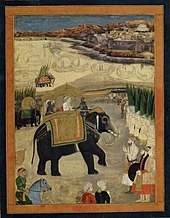

| ] under the command of Aurangzeb recaptures ] in October 1635.|left]] | |||

| Aurangzeb was nominally in charge of the force sent to ] with the intent of subduing the rebellious ruler of ], ], who had attacked another territory in defiance of Shah Jahan's policy and was refusing to atone for his actions. By arrangement, Aurangzeb stayed in the rear, away from the fighting, and took the advice of his generals as the ] gathered and commenced the siege of Orchha in 1635. The campaign was successful and Singh was removed from power.<ref>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|p=130}}</ref> | |||

| ]'' depicts Prince Aurangzeb facing a maddened ] named ''Sudhakar''.<ref>{{cite web|last=Abdul Hamid Lahori |url=http://warfare.atspace.eu/Moghul/ShahJahan/Prince_Awrangzeb_facing_a_maddened_elephant_named_Sudhakar.htm |title=Prince Awrangzeb (Aurangzeb) facing a maddened elephant named Sudhakar |year=1636 |website=Padshahnama |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140106034412/http://warfare.atspace.eu/Moghul/ShahJahan/Prince_Awrangzeb_facing_a_maddened_elephant_named_Sudhakar.htm |archive-date=6 January 2014}}</ref>]] | |||

| Aurangzeb was appointed viceroy of the ] in 1636.<ref name="Markovits2004p103">{{cite book |date=2004 |orig-date=First published 1994 as ''Histoire de l'Inde Moderne'' |editor-first=Claude |editor-last=Markovits |title=A History of Modern India, 1480–1950 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uzOmy2y0Zh4C |edition=2nd |location=London |publisher=Anthem Press |page=103 |isbn=978-1-84331-004-4}}</ref> After Shah Jahan's vassals had been devastated by the alarming expansion of ] during the reign of the ] boy-prince ], the emperor dispatched Aurangzeb, who in 1636 brought the Nizam Shahi dynasty to an end.<ref>George Michell and Mark Zebrowski, ''Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates'', (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 12.</ref> In 1637, Aurangzeb married the ] princess ], posthumously known as Rabia-ud-Daurani.{{sfn|Mukerjee|2001|p=23}}{{sfn|Sarkar|1912|p=61}} She was his first wife and chief consort as well as his favourite.<ref>{{cite book |last=Eraly |first= Abraham |author-link=Abraham Eraly |year=2007 |title=The Mughal World: Life in India's Last Golden Age |url=https://archive.org/details/mughalworldlifei00eral |url-access=limited |publisher=Penguin Books India |page= |isbn=978-0-14-310262-5}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Chandra |first=Satish |year=2002 |orig-date=1959 |title=Parties and politics at the Mughal Court, 1707–1740 |edition=4th |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=50 |isbn=978-0-19-565444-8}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Krieger-Krynicki |first1=Annie |translator-last=Hamid |translator-first=Enjum |title=Captive princess: Zebunissa, daughter of Emperor Aurangzeb |year=2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=92 |isbn=978-0-19-579837-1}}</ref> He also had an infatuation with a slave girl, ], whose death at a young age greatly affected him. In his old age, he was under the charms of his concubine, ].{{sfn|Mukerjee|2001|p=53}}{{sfn|Sarkar|1912|pp=64–66}} The latter had formerly been a companion to Dara Shukoh.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Katherine Butler |last=Brown |date=January 2007 |title=Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? Questions for the Historiography of his Reign |journal=Modern Asian Studies |volume=41 |issue=1 |pages=82–84 |doi=10.1017/S0026749X05002313|s2cid=145371208 | issn=0026-749X }}</ref> | |||

| In the same year, 1637, Aurangzeb was placed in charge of annexing the small ] kingdom of ], which he did with ease.<ref name=Richards1996p128>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|p=128}}</ref> In 1638, Aurangzeb married ], later known as Rahmat al-Nisa.{{sfn|Mukerjee|2001|p=23}}{{sfn|Sarkar|1912|p=61}} That same year, Aurangzeb dispatched an army to ], however his forces met stubborn resistance and were eventually repulsed at the end of a long siege.<ref>The Calcutta Review, Volume 75, 1882, p. 87.</ref><ref>Sir Charles Fawcett: The Travels of the Abbarrn India and the Near East, 1672 to 1674 Hakluyt Society, London, 1947, p. 167.</ref><ref>M. S. Commissariat: Mandelslo's Travels In Western India, Asian Educational Services, 1995, p. 57.</ref> At some point, Aurangzeb married ], who was a ] or ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Krieger-Krynicki |first=Annie |title=Captive Princess: Zebunissa, Daughter of Emperor Aurangzeb |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-195-79837-1 |pages=3, 41}}</ref>{{sfn|Mukerjee|2001|p=23}} | |||

| Shah Jahan was outraged to see Aurangzeb enter the interior palace compound in military attire and immediately dismissed him from his position of viceroy of the Deccan; Aurangzeb was also no longer allowed to use red tents or to associate himself with the official military standard of the Mughal emperor.{{Citation needed|date=October 2012}} Other sources state that Aurangzeb was dismissed from his position because Aurangzeb left the life of luxury and became a '']''.<ref>Ahmad, Fazl. Heroes of Islam. Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraff, 1993. Print.</ref> | |||

| ====Governor of Gujarat==== | |||

| In 1645, he was barred from the court for seven months. It is reported that he mentioned his grief about this to fellow Mughal commanders. Thereafter, Shah Jahan appointed him governor of ]. His rule in Gujarat was marked with religious disputes but he was rewarded for bringing stability.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Campbell |first1=James McNabb |year=1896 |title=History of Gujarát |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/54652/54652-h/54652-h.htm#pb280 |access-date=2022-04-29 |location=Bombay |publisher=Government Central Press |page=280 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Subramanian |first=Archana |date=2015-07-30 |title=Way to the throne |language=en-IN |work=The Hindu |url=https://www.thehindu.com/features/kids/rise-and-fall-of-aurangzeb/article7481718.ece |access-date=2022-02-26 |issn=0971-751X}}</ref> | |||

| ====Governor of Balkh==== | |||

| In 1647, Shah Jahan moved Aurangzeb from Gujarat to be governor of ], replacing a younger son, ], who had proved ineffective there. The area was under attack from ] and ] tribes. The Mughal artillery and muskets were matched by the skirmishing skills of their opponents which led to a stalemate. Aurangzeb discovered that his army could not live off the land, which was devastated by war.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} It is recorded that during the battle against the Uzbeks during this campaign, Aurangzeb dismounted from his elephant ride to recite prayer to the surprise of the opposing force commander.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Munis D. Faruqui |title=The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719 |date=2012 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-107-02217-1 |page=175 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2vhbDSXbbksC |access-date=15 March 2024 |language=En |format=Hardcover}}</ref> With the onset of winter, he and his father had to make an unsatisfactory deal with the Uzbeks. They had to give away territory in exchange for nominal recognition of Mughal sovereignty.<ref name="Richards 1996 132–133">{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|pp=132–133}}</ref> The Mughal force suffered still further with attacks by Uzbeks and other tribesmen as it retreated through the snow to ]. By the end of this two-year campaign, into which Aurangzeb had been plunged at a late stage, a vast sum of money had been expended for little gain.<ref name="Richards 1996 132–133"/> | |||

| Further unsuccessful military involvements followed, as Aurangzeb was appointed governor of ] and ]. His efforts in 1649 and 1652 to ] at ] which they had recently retaken after a decade of Mughal control, both ended in failure as winter approached. The logistical problems of supplying an army at the extremity of the empire, combined with the poor quality of armaments and the intransigence of the opposition have been cited by John Richards as the reasons for failure. A third attempt in 1653, led by Dara Shikoh, met with the same outcome.<ref>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|pp=134–135}}</ref> | |||

| ====Second Deccan governorate==== | |||

| Aurangzeb became viceroy of the Deccan again after he was replaced by Dara Shukoh in the attempt to recapture Kandahar. Aurangbad's two '']s'' (land grants) were moved there as a consequence of his return. The Deccan was a relatively impoverished area, this caused him to lose out financially. The area required grants were required from ] and Gujarat in order to maintain the administration. The situation caused ill-feeling between him and his father Shah Jahan who insisted that things could be improved if Aurangzeb made efforts to develop cultivation.<ref name="Chandra2005p267" /> Aurangzeb appointed Murshid Quli Khan{{Citation needed|reason=Murshid Quli Khan was born at 1670|date=June 2016}} to extend to the Deccan the ''zabt'' revenue system used in northern India. Murshid Quli Khan organised a survey of agricultural land and a tax assessment on what it produced. To increase revenue, Murshid Quli Khan granted loans for seed, livestock, and irrigation infrastructure. This led the Deccan region to return to prosperity.<ref name="Markovits2004p103" /><ref>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|pp=140, 188}}</ref> | |||

| Aurangzeb proposed to resolve financial difficulties by attacking the dynastic occupants of ] (the ]s) and ] (the ]s). This proposal would also extend Mughal influence by accruing more lands.<ref name="Chandra2005p267" /> Aurangzeb advanced against the Sultan of Bijapur and ]. The '']'' (governor or captain) of the fortified city, Sidi Marjan, was mortally wounded when a gunpowder magazine exploded. After twenty-seven days of fighting, ] was captured by the Mughals and Aurangzeb continued his advance.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Prasad |first=Ishwari |year=1974 |title=The Mughal Empire |location=Allahabad |publisher=Chugh Publications |pages=524–525 |oclc=1532660 |quote= marched in the direction of Bijapur and on reaching Bidar laid siege to it ... The Qiladar of the fort was Sidi Marjan ... were helped by an explosion of powder magazine in the fortress ... Sidi Marjan and two of his sons were badly burnt ... Thus was the fort of Bidar taken after a siege of 27 days ... Sidi Marjan died of his wounds soon afterwards ... Aurangzeb arrived at Kalyani.}}</ref> Aurangzeb suspected Dara had exerted influence on his father. He believed that he was on the verge of victory in both instances, and was frustrated that Shah Jahan chose then to settle for negotiations with the opposing forces rather than pushing for complete victory.<ref name="Chandra2005p267" /> | |||

| ===War of succession=== | ===War of succession=== | ||

| {{Main|Mughal war of succession (1658–1659)}} | |||

| ] fought in 1658, part of the ]]] | |||

| The four sons of Shah Jahan all held governorships during their father's reign. The emperor favoured the eldest, ].<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://scroll.in/article/879195/aurangzeb-and-dara-shikohs-fight-for-the-throne-was-entwined-with-the-rivalry-of-their-two-sisters |title=Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh's fight for the throne was entwined with the rivalry of their two sisters |first=Ira |last=Mukhoty |work=Scroll.in |date=17 May 2018}}</ref> This had caused resentment among the younger three, who sought at various times to strengthen alliances between themselves and against Dara. There was no Mughal tradition of ], the systematic passing of rule, upon an emperor's death, to his eldest son.<ref name="Chandra2005p267" /> Instead it was customary for sons to overthrow their father and for brothers to war to the death among themselves.<ref name="Markovits-2004">{{cite book |date=2004 |orig-date=First published 1994 as ''Histoire de l'Inde Moderne'' |editor-first=Claude |editor-last=Markovits |title=A History of Modern India, 1480–1950 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uzOmy2y0Zh4C |edition=2nd |location=London |publisher=Anthem Press |page=96 |isbn=978-1-84331-004-4}}</ref> Historian ] says that "In the ultimate resort, connections among the powerful military leaders, and military strength and capacity the real arbiters".<ref name="Chandra2005p267" /> The contest for power was primarily between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb because, although all four sons had demonstrated competence in their official roles, it was around these two that the supporting cast of officials and other influential people mostly circulated.<ref>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|pp=151–152}}</ref> There were ideological differences – Dara was an intellectual and a religious liberal in the mould of Akbar, while Aurangzeb was much more conservative – but, as historians ] and ] say, "To focus on divergent philosophies neglects the fact that Dara was a poor general and leader. It also ignores the fact that factional lines in the succession dispute were not, by and large, shaped by ideology."<ref>{{cite book |title=A Concise History of Modern India |url=https://archive.org/details/concisehistorymo00metc |url-access=limited |first1=Barbara D. |last1=Metcalf |first2=Thomas R. |last2=Metcalf |author-link1=Barbara D. Metcalf |author-link2=Thomas R. Metcalf |edition=2nd |location=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2006 |pages=–21 |isbn=978-0-521-86362-9}}</ref> Marc Gaborieau, professor of Indian studies at l'],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ceias.ehess.fr/index.php?90 |title=Marc Gaborieau |publisher=Centre d'Études de l'Inde et de l'Asie du Sud |date=6 July 2016 |language=fr |access-date=2 May 2016}}</ref> explains that "The loyalties of seem to have been motivated more by their own interests, the closeness of the family relation and above all the charisma of the pretenders than by ideological divides."<ref name="Markovits-2004" /> Muslims and Hindus did not divide along religious lines in their support for one pretender or the other nor, according to Chandra, is there much evidence to support the belief that Jahanara and other members of the royal family were split in their support. Jahanara, certainly, interceded at various times on behalf of all of the princes and was well-regarded by Aurangzeb even though she shared the religious outlook of Dara.<ref name="Chandra2005p271" /> | |||

| In 1656, a general under ] named Musa Khan led an army of 12,000 musketeers to attack Aurangzeb, who was ]. Later in the same campaign, Aurangzeb, in turn, rode against an army consisting of 8,000 horsemen and 20,000 ] musketeers.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Syed |first1=Anees Jahan |year=1977 |title=Aurangzeb in Muntakhab-al Lubab |publisher=Somaiya Publications |pages=64–65 |oclc=5240812}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kolff |first1=Dirk H. A. |author1-link=Dirk H. A. Kolff |year=2002 |orig-date=1990 |title=Naukar, Rajput, and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labour Market of Hindustan, 1450–1850 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SrdiVPsFRYIC&pg=PA22 |edition=illustrated, revised |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=22 |isbn=978-0-521-52305-9}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] fell ill in ], and was widely reported to have died. With this news, the struggle for succession began. Aurangzeb's eldest brother, ], was regarded as heir apparent, but the succession proved far from certain. When Shah Jahan supposedly died, his second son, ] declared himself emperor in ]. Imperial armies sent by Dara and Shah Jahan soon restrained this effort, and Shuja retreated. | |||

| After making clear his desire for his son Dara to take over after him, Shah Jahan fell ill with ] in 1657. He was kept in seclusion and cared for by Dara in the newly built city of ] (Old Delhi). Rumours spread that Shah Jahan had died, which led to concerns among his younger sons. Subsequently, these younger sons took military actions seemingly in response but it is not known whether these preparations were made in the mistaken belief that the rumours of death of Shah Jahan were true and that Dara might be hiding it for political gain, or whether the challengers were taking advantage of the situation.<ref name="Chandra2005p267">{{cite book |title=Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals |volume=2 |publisher=Har-Anand Publications |year=2005 |isbn=978-81-241-1066-9 |first=Satish |last=Chandra |author-link=Satish Chandra |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rm9MC4DDrcC&pg=PA267 |pages=267–269 |access-date=29 September 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Soon after, Shuja's youngest brother ], with secret promises of support from Aurangzeb, declared himself emperor in ]. Aurangzeb, ostensibly in support of Murad, marched north from Aurangabad, gathering support from nobles and generals. Following a series of victories, Aurangzeb declared that Dara had illegally usurped the throne. Shah Jahan, determined that Dara would succeed him, handed over control of his empire to Dara. A Hindu lord opposed to Aurangzeb and Murad, ], battled them both at Dharmatpur near ], leaving them heavily weakened. Aurangzeb eventually defeated Singh and concentrated his forces on Dara. A series of bloody battles followed, with troops loyal to Aurangzeb battering Dara's armies at . In a few months, Aurangzeb's forces surrounded ]. Fearing for his life, Dara departed for ], leaving behind Shah Jahan. The old emperor surrendered the ] of Agra to Aurangzeb's nobles, but Aurangzeb refused any meeting with his father, declaring that Dara was his enemy. | |||

| ] in ], where he had been governor since 1637 crowned himself King at RajMahal. He brought his cavalry, artillery and river flotilla upriver towards Agra. Near Varanasi his forces confronted a defending army sent from Delhi under the command of Prince Sulaiman Shukoh, son of Dara Shukoh, and Raja Jai Singh.<ref>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|p=159}}</ref> | |||

| In a sudden reversal, Aurangzeb then had Murad arrested after intoxicating him and later executed him;<ref>The Great Moghuls, ''Aurangzeb'', ]</ref> Murad's former supporters, instead of fighting for Murad, defected to Aurangzeb. Meanwhile, Dara gathered his forces, and set up an alliance with Shuja. But the key commander of Dara's armies, the ] general ], defected to Aurangzeb, along with many thousand Rajput soldiers. Dara fled Delhi and sought an alliance with brother Shuja, who refused the offer after Aurangzeb offered him the governorship of ]. This move had the effect of isolating Dara and causing more troops to defect to Aurangzeb. Shuja, however, uncertain of Aurangzeb's sincerity, continued to battle his brother, but his forces suffered a series of defeats at Aurangzeb's hands. At length, Shuja went into exile in ] (in present-day ]) where he disappeared, and was presumed to be dead. | |||

| Murad did the same in his governorship of Gujarat and Aurangzeb did so in the Deccan. | |||

| With Shuja and Murad disposed of, and with his father Shah Jahan confined in Agra, Aurangzeb pursued Dara, chasing him across the northwest bounds of the empire. After a series of battles, defeats and retreats, Dara was betrayed by one of his generals, who arrested and bound him. In ], Aurangzeb arranged a formal coronation in ]. He had Dara openly marched in chains back to Delhi; when Dara finally arrived, he had his brother executed. Legends about the cruelty of this execution abound, including stories that Aurangzeb had Dara's severed head sent to the dying Shah Jahan. With his succession secured, Aurangzeb kept Shah Jahan under house arrest at the Red Fort in Agra. Legends concerning this imprisonment abound, for the fort is ironically close to Shah Jahan's great architectural masterpiece, the ]. | |||

| After regaining some of his health, Shah Jahan moved to Agra and Dara urged him to send forces to challenge Shah Shuja and Murad, who had declared themselves rulers in their respective territories. While Shah Shuja was defeated at ] in February 1658, the army sent to deal with Murad discovered to their surprise that he and Aurangzeb had combined their forces,<ref name="Chandra2005p271" /> the two brothers having agreed to partition the empire once they had gained control of it.<ref name="Chandra2005p272" /> The two armies clashed at ] in April 1658, with Aurangzeb being the victor. Shuja was chased through ]. The victory of Aurangzeb proved this to be a poor decision by Dara Shikoh, who now had a defeated force on one front and a successful force unnecessarily pre-occupied on another. Realising that his recalled Bihar forces would not arrive at Agra in time to resist the emboldened Aurangzeb's advance, Dara scrambled to form alliances in order but found that Aurangzeb had already courted key potential candidates. When Dara's disparate, hastily concocted army clashed with Aurangzeb's well-disciplined, battle-hardened force at the ] in late May, neither Dara's men nor his generalship were any match for Aurangzeb. Dara had also become over-confident in his own abilities and, by ignoring advice not to lead in battle while his father was alive, he cemented the idea that he had usurped the throne.<ref name="Chandra2005p271">{{cite book |title=Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals |volume=2 |publisher=Har-Anand Publications |year=2005 |isbn=978-81-241-1066-9 |first=Satish |last=Chandra |author-link=Satish Chandra |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rm9MC4DDrcC&pg=PA270 |pages=270–271 |access-date=29 September 2012}}</ref> "After the defeat of Dara, Shah Jahan was imprisoned in the fort of Agra where he spent eight long years under the care of his favourite daughter Jahanara."<ref name="sen2">{{Cite book |last=Sen |first=Sailendra |title=A Textbook of Medieval Indian History |publisher=Primus Books |year=2013 |isbn=978-9-38060-734-4 |page=183}}</ref> | |||

| ==Aurangzeb's Reign== | |||

| ===Enforcement of Islamic law=== | |||

| Aurangzeb then broke his arrangement with Murad Baksh, which probably had been his intention all along.<ref name="Chandra2005p272" /> Instead of looking to partition the empire between himself and Murad, he had his brother arrested and imprisoned at Gwalior Fort. Murad was executed on 4 December 1661, ostensibly for the murder of the '']'' of Gujarat. The allegation was encouraged by Aurangzeb, who caused the ''diwan's'' son to seek retribution for the death under the principles of ].<ref>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|p=162}}</ref> Meanwhile, Dara gathered his forces, and moved to the ]. The army sent against Shuja was trapped in the east, its generals ] and Dilir Khan submitted to Aurangzeb, but Dara's son, Suleiman Shikoh, escaped. Aurangzeb offered Shah Shuja the governorship of Bengal. This move had the effect of isolating Dara Shikoh and causing more troops to defect to Aurangzeb. Shah Shuja, who had declared himself emperor in Bengal began to annex more territory and this prompted Aurangzeb to march from Punjab with a new and large army that fought during the ], where Shah Shuja and his ] armoured war elephants were routed by the forces loyal to Aurangzeb. Shah Shuja then fled to ] (in present-day Burma), where he was executed by the local rulers.<ref>''The Cambridge History of India'' (1922), vol. IV, p. 481.</ref> | |||

| The Mughals had for the most part been tolerant of non-Muslims (compared to Aurangzeb), allowing them to practice their customs and religion without too much interference. Though certain Muslim laws had been in place -- prohibitions against building new Hindu temples, the poll tax on non-Muslims (the ]), was repealed by Emperor ] in 1562. Akbar also encouraged political tolerance toward the non-Muslim majority. | |||

| With Shuja and Murad disposed of, and with his father immured in Agra, Aurangzeb pursued Dara Shikoh, chasing him across the north-western bounds of the empire. Aurangzeb claimed that Dara was no longer a Muslim {{citation needed |date=June 2018}} and accused him of poisoning the Mughal ] ]. After a series of battles, defeats and retreats, Dara was betrayed by one of his generals, who arrested and bound him. In 1658, Aurangzeb arranged his formal coronation in Delhi. | |||

| Until Aurangzeb's reign, ]n ] had been guided by mystical ] precepts. Although Sunni in ancestry, the emperors from ] on had tolerated or openly embraced the activities of the ] Sufis. But Aurangzeb abandoned many of the more liberal viewpoints of his predecessors. He espoused a more fundamentalist interpretation of Islam and a behavior based on the ] (Islamic law), which he set about codifying through edicts and policies. His ], is a 33 volume compilation of these edicts (which have never been challenged). | |||

| On 10 August 1659, Dara was executed on grounds of apostasy and his head was sent to Shah Jahan.<ref name="sen2"/> This was the first prominent execution of Aurangzeb based on accusations of being influenced by Hinduism, however some sources argue it was done for political reasons.<ref>{{cite book |last=Larson |first=Gerald James |title=India's Agony Over Religion |publisher=State University of New York Press |year=1995 |isbn=978-0-7914-2411-7 |page=111 |author-link=Gerald James Larson}}</ref> Aurangzeb had his allied brother Prince ] held for murder, judged and then executed.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Allan |first1=J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9_48AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA416 |title=The Cambridge Shorter History of India |last2=Haig |first2=Sir T. Wolseley |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1934 |editor-last=Dodwell |editor-first=H. H. |editor-link=H. H. Dodwell |page=416}}</ref> Aurangzeb was accused of poisoning his imprisoned nephew ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Smith |first=Vincent Arthur |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=p2gxAQAAMAAJ&pg=PG412 |title=The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911 |publisher=Clarendon Press |year=1920 |page=412 |author-link=Vincent Arthur Smith}}</ref> Having secured his position, Aurangzeb confined his frail father at the Agra Fort but did not mistreat him. Shah Jahan was cared for by Jahanara and died in 1666.<ref name="Chandra2005p272">{{cite book |title=Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals |volume=2 |publisher=Har-Anand Publications |year=2005 |isbn=978-81-241-1066-9 |first=Satish |last=Chandra |author-link=Satish Chandra |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rm9MC4DDrcC&pg=PA270 |page=272 |access-date=29 September 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Under Aurangzeb, Mughal court life changed dramatically. According to his interpretation (in consultation with fundamentalist clerics), Islam did not allow ]. Thus, he banished court musicians, dancers and singers (Surprisingly, he is well accomplished in playing ], a stringed instrument). Further, based on Muslim precepts forbidding images, he stopped the production of representational artwork, including the miniature painting that had reached its zenith before his rule. Soldiers and citizens were also given free rein to deface architectural images such as faces, flowers and vines -- even on the walls of Mughal palaces. Untold thousands of representational images were destroyed in this way. Aurangzeb abandoned the Hindu-inspired practices of former Mughal emperors, especially the practice of 'darshan', or public appearances to bestow blessings, which had been commonplace since the time of Akbar, as well as lavish celebrations of the Emperor's birthday. | |||

| == Ancestry == | |||

| Aurangzeb began to enact and enforce a series of edicts and with punishments. Most significantly, Aurangzeb initiated laws which sometimes interfered with non-Muslim worship. These included the destruction of several temples (mostly Hindu), a prohibition of certain religious gatherings, collection of the ] tax, the closing of non-Islamic religious schools, and prohibition of practices deemed immoral by him, such as temple dances. Often the punishment for breaking these laws was death. | |||

| {{ahnentafel|1. '''Aurangzeb'''|2. ]<ref name="Kobita">{{cite book |first=Kobita |last=Sarker |title=Shah Jahan and his paradise on earth: the story of Shah Jahan's creations in Agra and Shahjahanabad in the golden days of the Mughals |year=2007 |page=187}}</ref>|3. ]<ref name="Kobita"/>|4. ]<ref name="Mehta">{{cite book |first=J.l. |last=Mehta |title=Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India |year=1986 |page=418}}</ref>|5. ]<ref name="Mehta"/>|6. ]<ref name="Thackeray254">{{cite book |first1=Frank W. |last1=Thackeray |first2=John E. |last2=Findling |title=Events That Formed the Modern World |url=https://archive.org/details/eventsthatformed0005unse |url-access=registration |year=2012 |page=254}}</ref>|7. Diwanji Begum<ref name="Thackeray254"/>|8. ]<ref name="Mehta 1986 374">{{harvtxt|Mehta|1986|p=374}}</ref>|9. ]<ref name="Mehta 1986 374">{{harvtxt|Mehta|1986|p=374}}</ref>|10. ]<ref name="Mukerjee">{{cite book |first=Soma |last=Mukherjee |title=Royal Mughal Ladies and Their Contributions |publisher=Gyan Books |year=2001 |page=128 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v-2TyjzZhZEC |isbn=978-8-121-20760-7 }}</ref>|11. Manrang Devi <ref name="Mukerjee"/>|12. ]<ref>Subhash Parihar, ''Some Aspects of Indo-Islamic Architecture'' (1999), p. 149</ref>|13. ]<ref>{{cite book|last1=Shujauddin|first1=Mohammad|last2=Shujauddin|first2=Razia|title=The Life and Times of Noor Jahan|date=1967|publisher=Caravan Book House|page=1|language=en}}</ref>|14. Ghias ud-din 'Ali Asaf Khan<ref>{{cite book|last1=Ahmad|first1=Moin-ud-din|title=The Taj and Its Environments: With 8 Illus. from Photos., 1 Map, and 4 Plans|date=1924|publisher=R. G. Bansal|page=101|language=en}}</ref>||collapsed=yes|align=center|boxstyle_1=background-color: #fcc;|boxstyle_2=background-color: #fb9;|boxstyle_3=background-color: #ffc;|boxstyle_4=background-color: #bfc;}} | |||

| ==Reign== | |||

| There were a great many rebellions during Aurangzebs's reign, including those by the Rajput states of Marwar and Mewar, and the ]. Things came to such a head that ], the 9th Guru of the Sikhs was tortured and executed by Aurangzeb for refusing to accept Islam, a martyrdom which is mourned to this day by the Sikh community. The 10th Guru of the Sikhs, ] led an open revolt against Aurangzeb. His efforts to conquer the ] also met with fierce resistance. | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Bureaucracy=== | |||

| Aurangzeb's imperial bureaucracy employed significantly more Hindus than that of his predecessors. | |||

| Between 1679 and 1707, the number of Hindu officials in the Mughal administration rose by half, to represent 31.6% of Mughal nobility, the highest in the Mughal era.<ref name="Truschke50">{{cite book |last=Truschke |first=Audrey |year=2017 |title=Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India's Most Controversial King |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oUUkDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT50 |publisher=Stanford University Press |page=58 |isbn=978-1-5036-0259-5}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Malik|first=Jamal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FduG_t2sxwMC&q=Aurangzeb+levied+taxes+on+Hindu+merchants&pg=PA190|title=Islam in South Asia: A Short History|date= 2008|publisher=Brill|page=190|isbn=978-90-04-16859-6}}</ref> Many of them were ] and ], who were his political allies.<ref name="Truschke50" /> However, Aurangzeb encouraged high ranking Hindu officials to convert to Islam.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Laine|first=James W.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-x3fBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA152|title=Meta-Religion: Religion and Power in World History|year=2015|publisher=Univ of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-95999-6|page=153|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The climate of religious orthodoxy is often cited as the reason for these rebellions, as well as for the collapse of the Mughal empire after Aurangzeb. But many historians today are re-assessing the period, and offer economic and political reasons for the many rebellions and the disintegration that followed, rather than religious, including the fact that the empire had become too huge and unwieldy, also that Aurangzeb's long wars of expansion, especially his decades in the Deccan, seriously strained the imperial treasury, while the many new nobles created and promoted by him (many of them Deccanis) did not share the old loyalty to the empire. Above all, the peasantry was steadily getting bled to death. | |||

| === Economy === | |||

| Also, it is useful to note that even amidst the orthodoxy, a great many top imperial officers continued to be Hindu, including Aurangzeb's highest general Mirza Raja Jai Singh. The number of Hindu mansabdars actually went up in Aurangzeb's time to 33% in the fourth decade of his rule, from 24.5% under his father Shah Jahan. | |||

| Under his reign, the Mughal Empire contributed to the world's GDP by nearly 25%, surpassing ], making it the world's largest economy and biggest manufacturing power, more than the entirety of Western Europe, and signaled ].<ref>] (2003): '''', ], {{ISBN|92-64-10414-3}}, pp. 259–261</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Ahmed Sayeed |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IGnQDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA201 |title=Negate Fighting Faith |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2020 |isbn=978-93-88660-79-2 |page=201}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Religious policy=== | ||

| {{See also|Religious policy of the Mughals after Akbar}} | |||

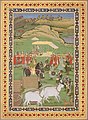

| ] in the ]. Such scenes would be rare in the latter part of his reign as he was permanently camped in the Deccan, fighting wars.]] | |||

| From the start of his reign up until his death, Aurangzeb engaged in almost constant warfare. He built up a massive army, and began a program of military expansion at all the boundaries of his empire. | |||

| ] law by introducing the ].|left]] | |||

| Aurangzeb pushed into the northwest -- into ], and what is now ]. He also drove south, conquering Bijapur and ], his old enemies. He further attempted to suppress the ] territories, which had recently been liberated from Bijapur by ]. | |||

| Aurangzeb was an orthodox Muslim ruler. Subsequent to the policies of his three predecessors, he endeavored to make ] a dominant force in his reign. However these efforts brought him into conflict with the forces that were opposed to this revival.<ref>{{Cite book|date=1977|editor-last=Holt|editor-first=P. M.|editor2-last=Lambton|editor2-first=Ann K. S.|editor3-last=Lewis|editor3-first=Bernard|title=The Cambridge History of Islam|language=en|volume=2a|page=52|doi=10.1017/chol9780521219488|isbn=978-1-139-05504-8}}</ref> Aurangzeb was a follower of the Mujaddidi Order and a disciple of the son of the Punjabi saint, ]. He sought to establish Islamic rule as instructed and inspired by him.<ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=US5gEAAAQBAJ&dq=aurangzeb+mujaddidi&pg=PA155 |page= 155 |title= History of Indian Nation: Medieval India |date= 2022 |publisher= K. K. Publications }}</ref> | |||

| But the combination of military expansion and religious intolerance had far deeper consequences. Though he succeeded in expanding Mughal control, it was at an enormous cost in lives and treasure. And as the empire expanded in size, the chain of command grew weaker. | |||

| ] stated that after returning from Kashmir, Aurangzeb issued order in 1663, to ban the practice of ], a Hindu practice to burn a widow whenever her husband passed away.<ref name=Columbia>{{cite book |author1=S. M. Ikram |author-link= S. M. Ikram |author2=Ainslie T. Embree |title=Muslim Civilization in India |chapter= 17 |url=https://franpritchett.com/00islamlinks/ikram/part2_17.html |publisher=Columbia University Press |access-date=25 November 2023 |language=En |format=Ebook |date=1964 |quote=Aurangzeb was most forthright in his efforts to stop sati. According to Manucci, on his return from Kashmir in December, 1663, he "issued an order that in all lands under Mughal control, never again should the officials allow a woman to be burnt." Manucci adds that "This order endures to this day."/26/ This order, though not mentioned in the formal histories, is recorded in the official guidebooks of the reign./27/ Although the possibility of an evasion of government orders through payment of bribes existed, later European travelers record that sati was not much practiced by the end of Aurangzeb's reign. As Ovington says in his Voyage to Surat: "Since the Mahometans became Masters of the Indies, this execrable custom is much abated, and almost laid aside, by the orders which nabobs receive for suppressing and extinguishing it in all their provinces. And now it is ] very rare, except it be some Rajah's wives, that the Indian women burn at all; /27/ Jadunath Sarkar, History of Aurangzib (Calcutta, 1916), III, 92. /28/ John Ovington, A Voyage to Surat (London, 1929), p. 201.}}</ref> Ikram recorded that Aurangzeb issued decree: | |||

| The ]s of Punjab grew both in strength and numbers in rebellion against Aurangzeb's armies. When the minor Muslim kingdoms of Golconda and Bijapur fell beneath Aurangzeb's might, rebellious Hindus flocked to join ] and the ]. For the last 27 years of his life, Aurangzeb engaged in constant battles in the ], at enormous expense. | |||

| <blockquote><p>''"in all lands under Mughal control, never again should the officials allow a woman to be burnt"''.<ref name=Columbia/> </p></blockquote> | |||

| Even Aurangzeb's own armies grew restive -- particularly the fierce ]s, who were his main source of strength. Aurangzeb gave a wide berth to the Rajputs, who were mostly Hindu. While they fought for Aurangzeb during his life, mostly out of fear, on his death they immediately revolted against the Empire, an essential after effect of Aurangzeb's Islamic fundamentalist policies. | |||

| Although Aurangzeb's orders could be evaded with payment of bribes to officials, adds Ikram, later European travellers record that ''sati'' was not much practised in Mughal empire, and that Sati was "very rare, except it be some Rajah's wives, that the Indian women burn at all" by the end of Aurangzeb's reign.<ref name=Columbia/> | |||

| With much of his attention on military matters, Aurangzeb's political power waned, and his provincial governors and generals grew in authority. | |||

| Historian Katherine Brown has noted that "The very name of Aurangzeb seems to act in the popular imagination as a signifier of politico-religious bigotry and repression, regardless of historical accuracy." The subject has also resonated in modern times with popularly accepted claims that he intended to destroy the ].<ref>{{cite journal |first=Katherine Butler |last=Brown |date=January 2007 |title=Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? Questions for the Historiography of his Reign |journal=Modern Asian Studies |volume=41 |issue=1 |page=78 |doi=10.1017/S0026749X05002313|s2cid=145371208 }}</ref> As a political and religious conservative, Aurangzeb chose not to follow the secular-religious viewpoints of his predecessors after his ascension. He made no mention of the Persian concept of kinship, the Farr-i-Aizadi, and based his rule on the Quranic concept of kingship.<ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=EjFmAAAAMAAJ&q=aurangzeb+chingezi |title= Indian Archives: Volume 50 |page= 141 |date= 2001 |publisher= National Archives of India. }}</ref> Shah Jahan had already moved away from the liberalism of ], although in a token manner rather than with the intent of suppressing Hinduism,<ref name="Chandra2005p255">{{cite book |title=Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals |volume=2 |publisher=Har-Anand Publications |year=2005 |isbn=978-81-241-1066-9 |first=Satish |last=Chandra |author-link=Satish Chandra |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rm9MC4DDrcC&pg=PA255 |pages=255–256 |access-date=29 September 2012}}</ref>{{efn|Regarding the tokenistic aspect of Shah Jahan's actions to strengthen Islam in his empire, Satish Chandra says, "We may conclude that Shah Jahan tried to effect a compromise. While formally declaring the state to be an Islamic one, showing respect to the ''sharia'', and observing its injunctions in his personal life, he did not reject any of the liberal measures of Akbar. ... Shah Jahan's compromise was based not on principle but on expediency."<ref name="Chandra2005p255" />}} and Aurangzeb took the change still further.<ref>{{harvtxt|Richards|1996|p=171}}</ref> Though the approach to faith of Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan was more syncretic than ], the founder of the empire, Aurangzeb's position is not so obvious. | |||

| ===Conversion of non-Muslims=== | |||

| The forcible conversion of non-Muslims to Islam was a policy objective under Aurangzeb's rule.<blockquote>Aurangzeb's ultimate aim was conversion of non-Muslims to Islam. Whenever possible the emperor gave out robes of honor, cash gifts, and promotions to converts. It quickly became known that conversion was a sure way to the emperor's favor.<ref>Richards 1995:177</ref></blockquote>In economic and political terms, Aurangzeb's rule significantly favored Muslims over non-Muslims,<ref>Richards 1995:177. "In many disputed successions for hereditary local office Aurangzeb chose candidates who had converted to Islam over their rivals. Pargana headmen and quangos or recordkeepers were targeted especially for pressure to convert. The message was very clear for all concerned. Shared political community must also be shared religious belief."</ref> and he interfered with non-Muslim religious practice through sweeping and often violent methods. Aurangzeb created a climate favorable for conversion by discriminating against non-Muslims who refused to give up their ancestral faiths and rewarding those who converted. | |||

| His emphasis on ] competed, or was directly in conflict, with his insistence that ''zawabit'' or secular decrees could supersede sharia.<ref>{{cite book |title=Medieval India: From Sultanate To The Mughals: Mughal Empire (1526–1748) |first=Satish |last=Chandra |edition=Second Reprint|year=2006 |publisher=Har-Anand Publications Pvt Ltd |orig-date=1999 |isbn=978-81-241-1066-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rm9MC4DDrcC&pg=PA350 |page=350 |access-date=24 October 2014}}</ref> The chief qazi refusing to crown him in 1659, Aurangzeb had a political need to present himself as a "defender of the sharia" due to popular opposition to his actions against his father and brothers.<ref>{{cite book|author=Satish Chandra|title=Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part – II|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rm9MC4DDrcC&pg=PA350|year=2005|publisher=Har-Anand Publications|isbn=978-81-241-1066-9|pages=280–|quote=Although Aurangzeb had not raised the slogan of defending Islam before the battle of Samugarh with Dara, and had tried to befriend the Rajput rajas as we have seen, there were a number of factors which make it necessary for Aurangzeb to present himself as the defender of the sharia, and to try and win over the theologians. A principal factor was the popular revulsion against his treatment of his brothers, Murad and Dara, both of whom had the reputation of being liberal patrons of the poor and needy. Aurangzeb was shocked when as the time of his second coronation in 1659, the chief qazi refused to crown him since his father was still alive.}}</ref> Despite claims of sweeping edicts and policies, contradictory accounts exist. Historian Katherine Brown has argued that Aurangzeb never imposed a complete ban on music.<ref name="Brown">{{cite journal |first=Katherine Butler |last=Brown |date=January 2007 |title=Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? Questions for the Historiography of his Reign |journal=Modern Asian Studies |volume=41 |issue=1 |page=77 |doi=10.1017/S0026749X05002313|s2cid=145371208 |quote=More importantly, though, the fact that Aurangzeb did not order a universal ban on music lends support to the idea that his regime was less intolerant and repressive than has been widely believed in the past...Thus, the overwhelming evidence against a ban on musical practice in Aurangzeb's reign suggests that the nature of his state was less orthodox, tyrannical and centralised than }}</ref> He sought to codify ] law by the work of several hundred jurists, called ].<ref name="Brown"/> It is possible the War of Succession and continued incursions combined with Shah Jahan's spending made cultural expenditure impossible.<ref>{{cite book |last=Zaman |first=Taymiya R. |year=2007 |title=Inscribing Empire: Sovereignty and Subjectivity in Mughal Memoirs |publisher=University of Michigan |page=153 |isbn=978-0-549-18117-0}}</ref> | |||

| ===Atitudes towards Hindus=== | |||

| Aurangzeb has been widely characterized as an ], unlike other more liberal emperors who immediately preceded him. This characterization came about largely due to his disparaging views against Hindus and his attempts to induce the conversion of Hindus to Islam.<ref name="Singhal"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Singhal | |||

| | first = Damodar Prasad | |||

| | authorlink = Damodar Prasad Singhal | |||

| | title = A History of the Indian People | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | publisher = Cosmo (Publications,India); New Ed edition | |||

| | language = English | |||

| | url = | |||

| | isbn = 8170200148 | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=""> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Prasad | |||

| | first = Ishwari | |||

| | authorlink = Ishwari Prasad | |||

| | title = A Short History of Muslim Rule in India, from the Advent of Islam to the Death of Aurangzeb P 609 | |||

| | year = 1965 | |||

| | publisher = Allahabad. The Indian Press. Private Ltd. | |||

| | language = English | |||

| | isbn = N/A | |||

| }}</ref>The anti-Hindu measures of Aurangzeb were intended to help the orthodox Sunni faith gain prominence in India in an indirect manner.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Lalwani | |||

| | first = Kastur Chand | |||

| | authorlink = Kastur Chand Lalwani | |||

| | title = The medieval muddle (Philosophy of Indian history) P90 | |||

| | year = 1978 | |||

| | publisher = Prajñanam | |||

| | language = English | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| His various edicts against Hindus, such as banning the celebration of ] and imposition of ] on non-Muslims are also factors in determining his attitudes.Indian historian, Sir ] has traced the anti-Hindu policies of Aurangzeb from as early an year as 1644 AD<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Joshi | |||

| | first = Rekha | |||

| | authorlink = Rekha Joshi | |||

| | title = Aurangzeb, Attitudes and Inclinations Pg 34 | |||

| | year = 1979 | |||

| | publisher = Original from the ] | |||

| | language = English | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> Historian E. Taylor writes that his negative views on Hindus were the primary reason for his reversal of the liberal policies of the previous Mughal emperors and "resume the persecution of Hindus" in the Empire, and the many rebellions that arose against him in ] and among the ].<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Taylor | |||

| | first = Edmond | |||

| | authorlink = Edmond Taylor | |||

| | title = Richer by Asia P147 | |||

| | year = 1947 | |||

| | publisher = Houghton Mifflin Co. | |||

| | language = English | |||

| | url = http://www.amazon.com/RICHER-ASIA-introduction-Robert-Trumbell/dp/B000JW8ZOW/sr=1-4/qid=1171927259/ref=sr_1_4/103-5884052-1974266?ie=UTF8&s=books | |||

| | isbn = N/A | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref>. | |||

| He learnt that at ], ], and particularly at ], the teachings of Hindu ] attracted numerous Muslims. He ordered the ]s of these provinces to demolish the schools and the temples of non-Muslims.<ref>{{cite book |last=Mukhia |first=Harbans |author-link=Harbans Mukhia |year=2004 |title=The Mughals of India |url=https://archive.org/details/mughalsindiapeop00mukh |url-access=limited |page= |publisher=Wiley |isbn=978-0-631-18555-0 |quote=learnt that in Multan and Thatta in Sind, and especially at Varanasi, Brahmins attracted a large number of Muslims to their discourses. Aurangzeb ... ordered the governors of all these provinces 'to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels'.}}</ref> Aurangzeb also ordered subahdars to punish Muslims who dressed like non-Muslims. The executions of the ] Sufi mystic ] and the ninth Sikh Guru ] bear testimony to Aurangzeb's religious policy; the former was beheaded on multiple accounts of heresy,{{efn| It has however been argued that the Mughal emperor had political motives for this particular execution. See the article on ] for references.}} the latter, according to Sikhs, because he objected to Aurangzeb's ]s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.com/religion/religions/sikhism/people/teghbahadur.shtml |title=Religions – Sikhism: Guru Tegh Bahadur |publisher=BBC |date=1 October 2009 |access-date=29 April 2012}}</ref><ref>{{citation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7xEdAAAAMAAJ|title=A Vindication of Aurangzeb: In Two Parts|author=Sadiq Ali|year=1918|page=141}}</ref><ref>{{citation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wsiXwh_tIGkC&pg=RA1-PA152|title=The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination|page=152|author=Vipul Singh|publisher=Pearson Education India |isbn=978-81-317-1753-0}}</ref> Aurangzeb had also banned the celebration of the Zoroastrian festival of Nauroz along with other un-Islamic ceremonies, and encouraged conversions to Islam; instances of persecution against particular Muslim factions were also reported.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Na |first1=Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aKenKtONX2MC&pg=PA145 |title=Islam and the Secular State |last2=Naʻīm |first2=ʻAbd Allāh Aḥmad |date=2009 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-03376-4 |page=145 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Richards |first=John F. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HHyVh29gy4QC&pg=PA173 |title=The Mughal Empire |date=1993 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-56603-2 |page=173 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Hindu temple desecration=== | |||

| Fortunately, in recent years quite a few Hindu historians have come out in the open disputing those allegations. For example, historian Babu Nagendranath Banerjee rejected the accusation of forced conversion of Hindus by Muslim rulers by stating that if that was their intention then in India today there would not be nearly four times as many Hindus compared to Muslims, despite the fact that Muslims had ruled for nearly a thousand years. Banerjee challenged the Hindu hypothesis that Aurangzeb was anti-Hindu by reasoning that if the latter were truly guilty of such bigotry, how could he appoint a Hindu as his military commander-in-chief? Surely, he could have afforded to appoint a competent Muslim general in that position. Banerjee further stated: "No one should accuse Aurangzeb of being communal minded. In his administration, the state policy was formulated by Hindus. Two Hindus held the highest position in the State Treasury. Some prejudiced Muslims even questioned the merit of his decision to appoint non-Muslims to such high offices. The Emperor refuted that by stating that he had been following the dictates of the Shariah (Islamic Law) which demands appointing right persons in right positions." During Aurangzeb's long reign of fifty years, many Hindus, notably Jaswant Singh, Raja Rajrup, Kabir Singh, Arghanath Singh, Prem Dev Singh, Dilip Roy, and Rasik Lal Crory, held very high administrative positions. Two of the highest ranked generals in Aurangzeb's administration, Jaswant Singh and Jaya Singh, were Hindus. Other notable Hindu generals who commanded a garrison of two to five thousand soldiers were Raja Vim Singh of Udaypur, Indra Singh, Achalaji and Arjuji. One wonders if Aurangzeb was hostile to Hindus, why would he position all these Hindus to high positions of authority, especially in the military, who could have mutinied against him and removed him from his throne? | |||

| ] has reported that according to many modern historians and thinkers, the puritanical thought of ] inspired the religious orthodoxy policy of Aurangzeb.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Gerhard Bowering |author2=Mahan Mirza |author3=Patricia Crone |title=The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought |date=2013 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-13484-0 |page=27 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q1I0pcrFFSUC |access-date=6 March 2024 |language=En |format=Hardcover}}</ref>{{sfn|Malik|Zubair|Parveen|2016|pp=162-163}} | |||

| Most Hindus like Akbar over Aurangzeb for his multi-ethnic court where Hindus were favored. Historian Shri Sharma states that while Emperor Akbar had fourteen Hindu Mansabdars (high officials) in his court, Aurangzeb actually had 148 Hindu high officials in his court. (Ref: Mughal Government) But this fact is somewhat less known. | |||

| ===Taxation policy=== | |||

| Shortly after coming to power, Aurangzeb remitted more than 80 long-standing taxes affecting all of his subjects.<ref name="Pirbhai-2009">{{Cite book|last=Pirbhai|first=M. Reza|url=https://brill.com/view/title/17049|title=Reconsidering Islam in a South Asian Context|date=2009|publisher=Brill|isbn=978-90-474-3102-2|location=|pages=67–116|chapter=Chapter Two : Indicism, Intoxication And Sobriety Among The 'Great Mughals'|doi=10.1163/ej.9789004177581.i-370.14|chapter-url=https://brill.com/view/book/9789047431022/Bej.9789004177581.i-370_004.xml}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Chandra|first=Satish|date=September 1969|title=Jizyah and the State in India during the 17th Century|journal=Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient|volume=12|issue=3|pages=322–340|doi=10.2307/3596130|jstor=3596130|issn=0022-4995}}</ref>] | |||