| Revision as of 22:44, 14 January 2018 view sourcePerunslava (talk | contribs)172 editsm Source states Central Europe only, no mention of East (https://www.fio.pl/stocks-investments/stocks/stocks-poland)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:39, 23 January 2025 view source ImperatorPublius (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,151 editsNo edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Country in Central Europe}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Polska|the dance|Polska (dance)}} | |||

| {{redirect2|Polska|Rzeczpospolita Polska|the dance|Polska (dance)|other uses|Poland (disambiguation)|and|Rzeczpospolita (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Rzeczpospolita Polska}} | |||

| {{ |

{{pp-move}} | ||

| {{pp |

{{pp|small=yes}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} | ||

| {{Use British English|date=June 2024}} | |||

| {{Coord|52|N|20|E|type:country_region:PL|display=title}} | |||

| {{Infobox country | {{Infobox country | ||

| |conventional_long_name = Republic of Poland | | conventional_long_name = Republic of Poland | ||

| |common_name = Poland | | common_name = Poland | ||

| |native_name = {{native name|pl|Rzeczpospolita Polska}} | | native_name = {{native name|pl|Rzeczpospolita Polska}} | ||

| |image_flag = Flag of Poland.svg | | image_flag = Flag of Poland.svg | ||

| |flag_border = Flag of Poland (normative). |

| flag_border = Flag of Poland (normative).svgize | ||

| |image_coat = Herb Polski.svg | | image_coat = Herb Polski.svg | ||

| |national_anthem ="]"<br /> |

| national_anthem = {{lang|pl|"]"|italics=no}}<br />("Poland Is Not Yet Lost")<br /><div style="padding-top:0.5em;">{{center|]}}</div> | ||

| | demonym = {{hlist|]|Pole}} | |||

| |image_map = EU-Poland.svg | |||

| <!-- Maps and coordinates -->| image_map = {{Switcher|]|Show globe|]|Show map of Europe|default=1}} | |||

| |map_caption = {{map caption |location_color=dark green |region=Europe |region_color=dark grey |subregion=the ] |subregion_color=green |legend=EU-Poland.svg}} | |||

| | map_caption = {{map caption |location_color=dark green |region=Europe |region_color=dark grey |subregion=the ] |subregion_color=green |legend=EU-Poland.svg}} | |||

| |image_map2 = Un-poland.png | |||

| |capital = ] | | capital = ] | ||

| |coordinates = {{Coord|52|13|N|21|02|E|type:city}} | | coordinates = {{Coord|52|13|N|21|02|E|type:city}} | ||

| |largest_city = capital | | largest_city = capital | ||

| <!-- Language -->| languages_type = ] | |||

| |official_languages = ]<ref>], Article 27.</ref> | |||

| | languages = ]<ref>], Article 27.</ref> | |||

| |languages_type = ] | |||

| <!-- Population, ethnic groups -->| population_census = {{IncreaseNeutral}} 38,036,118<ref>{{Cite web |title=Statistical Bulletin No 11/2022 |url=https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/other-studies/informations-on-socio-economic-situation/statistical-bulletin-no-112022,4,145.html |access-date=23 December 2022 |website=Statistics Poland |archive-date=23 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221223120843/https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/other-studies/informations-on-socio-economic-situation/statistical-bulletin-no-112022,4,145.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |languages = | |||

| | population_census_year = 2022 | |||

| |languages2_type = ] | |||

| | population_census_rank = 38th | |||

| |languages2 = ], ], ], ], ], ], ]<ref>{{cite web | url=http://mniejszosci.narodowe.mswia.gov.pl/mne/mniejszosci/charakterystyka-mniejs/6480,Charakterystyka-mniejszosci-narodowych-i-etnicznych-w-Polsce.html | author=Ministerstw Spraw Wewnętrznych RP|title=Charakterystyka mniejszości narodowych i etnicznych w Polsce | language=pl}}</ref> | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 122 | |||

| |ethnic_groups = | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 315.9 <!--Do not remove per ]. --> | |||

| {{unbulleted list | |||

| | population_density_rank = 75th | |||

| | 94.61% ]|] | |||

| | ethnic_groups = {{tree list}} | |||

| | 0.28% ] | |||

| *98.8% ]{{efn|Multiple national identity was available in the census.}} | |||

| | 0.12% ] | |||

| **96.2% only Polish | |||

| | 0.12% ] | |||

| **2.5% Polish and others | |||

| | 0.04% ] | |||

| *1.1% only ] | |||

| | 0.03% ] | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| | 0.02% ] | |||

| | ethnic_groups_year = 2021 | |||

| | 4.78% other | |||

| | ethnic_groups_ref = <ref name="2021 Census">{{cite web|url=https://stat.gov.pl/en/national-census/national-population-and-housing-census-2021/final-results-of-the-national-population-and-housing-census-2021/size-and-demographic-social-structure-in-the-light-of-the-2021-census-results,6,1.html |title=National Population and Housing Census 2021 Population. Size and demographic-social structure in the light of the 2021 Census results |language=en }}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| | religion = {{ublist|item_style=white-space: | |||

| |ethnic_groups_year = 2011<ref>{{cite web|format=PDF |url=http://stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/lu_nps2011_wyniki_nsp2011_22032012.pdf |title=Wyniki Narodowego Spisu Powszechnego Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 |trans-title=Results of the National Census of Population and Housing 2011 |language=pl |work=Central Statistical Office |date=March 2012 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116214520/http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/PUBL_lu_nps2011_wyniki_nsp2011_22032012.pdf |archivedate=16 January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| |{{Tree list}} | |||

| |religion = {{ublist |item_style=white-space:nowrap; |87.6% ] |7.1% No Answer |3.1% ] |2.2% ] }} | |||

| * 72.4% ] | |||

| |religion_year = 2011<ref name="GUS99"/> | |||

| ** 71.3% ] | |||

| |demonym = {{hlist |Polish|Pole}} | |||

| ** 1.1% ] | |||

| |government_type = {{Nowrap|] ]}} ] | |||

| {{Tree list/end}} | |||

| |leader_title1 = ] | |||

| |6.9% ] | |||

| |leader_name1 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| | |

|0.1% ] | ||

| |20.6% unanswered | |||

| |leader_name2 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |legislature = ] | |||

| | religion_year = 2021<ref name="Census 2021">{{Cite web |title=Final results of the National Population and Housing Census 2021 |url=https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/6536/10/1/1/wyniki_ostateczne_nsp2021_nar_jezyk_wyznanie_29_09_202.xlsx |publisher=Statistics Poland}}</ref> | |||

| |upper_house = ] | |||

| <!-- Government type, leaders -->| government_type = Unitary ]{{refn|name=SEMIPRES|<ref>{{cite web |title=Poland 1997 (rev. 2009) |url=https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Poland_2009?lang=en |website=www.constituteproject.org |access-date=9 October 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Veser |first=Ernst |author-link=:de:Ernst Veser |date=23 September 1997 |title=Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's Concept — A New Political System Model |url=https://www.rchss.sinica.edu.tw/files_news/11-01-1999/11_1_2.pdf|access-date=21 August 2017 |publisher=Department of Education, School of Education, ], zh |pages=39–60 |quote=Duhamel has developed the approach further: He stresses that the French construction does not correspond to either parliamentary or the presidential form of government, and then develops the distinction of 'système politique' and 'régime constitutionnel'. While the former comprises the exercise of power that results from the dominant institutional practice, the latter is the totality of the rules for the dominant institutional practice of power. In this way, France appears as 'presidentialist system' endowed with a 'semi-presidential regime' (1983: 587). By this standard, he recognizes Duverger's ''pléiade'' as semi-presidential regimes, as well as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Lithuania (1993: 87). }}</ref><ref name="Draft">{{cite journal |last=Shugart |first=Matthew Søberg |author-link=Matthew Søberg Shugart |date=September 2005 |title=Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns |url=http://dss.ucsd.edu/~mshugart/semi-presidentialism.pdf |journal=Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080819200307/http://dss.ucsd.edu/~mshugart/semi-presidentialism.pdf |archive-date=19 August 2008 |access-date=21 August 2017 }}</ref><ref name="Shugart2005">{{cite journal |last=Shugart |first=Matthew Søberg |author-link=Matthew Søberg Shugart |date=December 2005 |title=Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns |url=https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1057%2Fpalgrave.fp.8200087.pdf |journal=French Politics |volume=3 |issue=3 |pages=323–351 |doi=10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087 |doi-access=free |access-date=21 August 2017 |quote=Even if the president has no discretion in the forming of cabinets or the right to dissolve parliament, his or her constitutional authority can be regarded as 'quite considerable' in Duverger's sense if cabinet legislation approved in parliament can be blocked by the people's elected agent. Such powers are especially relevant if an extraordinary majority is required to override a veto, as in Mongolia, Poland, and Senegal. In these cases, while the government is fully accountable to Parliament, it cannot legislate without taking the potentially different policy preferences of the president into account. }}</ref><ref name="McMenamin" >{{cite web |last=McMenamin |first=Iain |title=Semi-Presidentialism and Democratisation in Poland |url= http://webpages.dcu.ie/~mcmenami/Poland_semi-presidentialism_2.pdf |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20120212225305/http://webpages.dcu.ie/~mcmenami/Poland_semi-presidentialism_2.pdf |archive-date=12 February 2012 |publisher=School of Law and Government, ] |access-date=11 December 2017 }}</ref>}} | |||

| |lower_house = '']'' | |||

| | leader_title1 = ] | |||

| |sovereignty_type = Formation | |||

| | leader_name1 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |established_event1 = ]{{ref label|b|b}} | |||

| | leader_title2 = ] | |||

| |established_date1 = 14 April 966 | |||

| | leader_name2 = ] | |||

| |established_event2 = ] | |||

| | leader_title3 = ] | |||

| |established_date2 = 18 April 1025 | |||

| | leader_name3 = ] | |||

| |established_event3 = ] | |||

| | leader_title4 = ] | |||

| |established_date3 = 1 July 1569 | |||

| | leader_name4 = ] | |||

| |established_event4 = ] | |||

| | legislature = ] | |||

| |established_date4 = 24 October 1795 | |||

| | |

| upper_house = ] | ||

| | lower_house = ] | |||

| |established_date5 = 22 July 1807 | |||

| | |

<!-- Events -->| sovereignty_type = ] | ||

| | established_event1 = ]{{efn|"The dukes (dux) were originally the commanders of an armed retinue (drużyna) with which they broke the authority of the chieftains of the clans, thus transforming the original tribal organisation into a territorial unit."<ref name="britannica_com">{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Poland/History |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |title=Poland |date=2023 |access-date=31 December 2023 |archive-date=19 January 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240119191221/https://www.britannica.com/place/Poland/History |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| |established_date6 = 9 June 1815 | |||

| | established_date1 = {{circa}} 960 | |||

| |established_event7 = ] | |||

| | established_event2 = ]{{efn|"Mieszko accepted Roman Catholicism via Bohemia in 966. A missionary bishopric directly dependent on the papacy was established in Poznań. This was the true beginning of Polish history, for Christianity was a carrier of Western civilisation with which Poland was henceforth associated."<ref name="britannica_com" />}} | |||

| |established_date7 = 11 November 1918 | |||

| | established_date2 = 14 April 966 | |||

| |established_event8 = ], ] | |||

| | established_event3 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |established_date8 = 1 September 1939 | |||

| | established_date3 = 18 April 1025 | |||

| |established_event9 = ] | |||

| | established_event4 = ] | |||

| |established_date9 = 8 April 1945 | |||

| | established_date4 = 1 July 1569 | |||

| |established_event10 = ] | |||

| | established_event6 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |established_date10 = 13 September 1989 | |||

| | established_date6 = 11 November 1918 | |||

| |established_event11 = ] ] | |||

| | established_event7 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |established_date11 = 1 May 2004 | |||

| | established_date7 = 17 September 1939 | |||

| |area_km2 = 312679 | |||

| | established_event8 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |area_footnote = {{ref label|a|a}} | |||

| | established_date8 = 22 July 1944 | |||

| |area_rank = 69th | |||

| | established_event9 = {{nowrap|]}} | |||

| |area_sq_mi = 120,696.41 <!--Do not remove per ]--> | |||

| | established_date9 = {{nowrap|31 December 1989}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19890750444|title=The Act of December 29, 1989 amending the Constitution of the Polish People's Republic.|publisher=Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych|access-date=18 October 2020|archive-date=19 October 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201019101959/http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19890750444|url-status=live}} {{in lang|pl}}</ref> | |||

| |percent_water = 3.07 | |||

| <!-- Area -->| area_km2 = 312696 | |||

| |population_estimate = 38,422,346<ref>{{cite web|url=http://demografia.stat.gov.pl/bazademografia/Tables.aspx|title=Wyniki badań bieżących - Baza Demografia - Główny Urząd Statystyczny|first=|last=olsztyn.stat.gov.pl/|website=demografia.stat.gov.pl}}</ref> | |||

| | area_footnote = <ref name="GUS">{{Cite web |last=GUS |title=Powierzchnia i ludność w przekroju terytorialnym w 2023 roku |url=https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/powierzchnia-i-ludnosc-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2023-roku,7,20.html |access-date=19 October 2023 |archive-date=22 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230922225517/https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/powierzchnia-i-ludnosc-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2023-roku,7,20.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="BBC News 2023">{{Cite web |date=12 November 2023 |title=Poland country profile |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17753718 |access-date=12 November 2023 |website=BBC News |archive-date=21 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231021204608/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17753718 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |population_estimate_year = 30 June 2017 | |||

| | area_rank = 69th | |||

| |population_estimate_rank = 35th | |||

| | area_sq_mi = 121,209.44 <!-- Do not remove per ]. --> | |||

| |population_density_km2 = 123 | |||

| | percent_water = 1.48 (2015)<ref>{{Cite web |title=Surface water and surface water change |url=https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SURFACE_WATER |access-date=11 October 2020 |publisher=] (OECD) |archive-date=24 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210324133453/https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SURFACE_WATER |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |population_density_sq_mi = 319.9 <!--Do not remove per ]--> | |||

| | GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $1.992 trillion<ref name="IMFWEO.PL">{{Cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=964,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2022&ey=2029&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Poland) |publisher=] |date=22 October 2024 |access-date=18 January 2025}}</ref> | |||

| |population_density_rank = 83rd | |||

| | GDP_PPP_year = 2025 | |||

| |GDP_PPP = $1.1 trillion<ref name=imf-gdp>{{cite web|title=5. Report for Selected Countries and Subjects|url=http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2017/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=94&pr.y=3&sy=2017&ey=2017&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=964&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC&grp=0&a=|publisher=]|accessdate=8 May 2017}}</ref> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_rank = 20th | |||

| |GDP_PPP_year = 2018 | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{increase}} $54,498<ref name="IMFWEO.PL" /> | |||

| |GDP_PPP_rank = 21st | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 38th | |||

| |GDP_PPP_per_capita = $30,827 | |||

| |GDP_nominal = $ |

| GDP_nominal = {{increase}} $915 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.PL" /> | ||

| |GDP_nominal_year = |

| GDP_nominal_year = 2025 | ||

| |GDP_nominal_rank = |

| GDP_nominal_rank = 21st | ||

| |GDP_nominal_per_capita = $ |

| GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{increase}} $25,041<ref name="IMFWEO.PL" /> | ||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 50th | |||

| |Gini = 32.08 <!--number only--> | |||

| <!-- Gini -->| Gini = 26.3 <!--number only--> | |||

| |Gini_year = 2014 | |||

| | Gini_year = 2022 | |||

| |Gini_change = decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady--> | |||

| | Gini_change = decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady--> | |||

| |Gini_ref = <ref>{{cite journal|url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SIPOVGINIPOL|title=GINI Index for Poland|date=17 October 2016|publisher=|accessdate=25 April 2017}}</ref> | |||

| | Gini_ref = <ref name=eurogini>{{cite web |url=https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tessi190/default/table?lang=en |title=Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey|publisher=] |website=ec.europa.eu |access-date=13 April 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |Gini_rank = | |||

| |HDI = 0. |

<!-- HDI -->| HDI = 0.881<!--number only--> | ||

| |HDI_year = |

| HDI_year = 2022<!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year. --> | ||

| |HDI_change = increase<!--increase/decrease/steady--> | | HDI_change = increase<!--increase/decrease/steady--> | ||

| |HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web |

| HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web|url=https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2023-24_HDR/HDR23-24_Statistical_Annex_HDI_Table.xlsx|title=Human Development Report 2023/2024|language=en|publisher=]|date=19 March 2024|access-date=19 March 2024|archive-date=19 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319085123/https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2023-24_HDR/HDR23-24_Statistical_Annex_HDI_Table.xlsx|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| |HDI_rank = 36th | | HDI_rank = 36th | ||

| |currency = ] | <!-- Currency -->| currency = ] | ||

| |currency_code = PLN | | currency_code = PLN | ||

| |time_zone = ] | <!-- Time zone, date format, other -->| time_zone = ] | ||

| |utc_offset = +1 | | utc_offset = +1 | ||

| |utc_offset_DST = +2 | | utc_offset_DST = +2 | ||

| |time_zone_DST = ] | | time_zone_DST = ] | ||

| | date_format = dd.mm.yyyy (]) | |||

| |drives_on = right | |||

| | drives_on = right | |||

| |calling_code = ] | |||

| | calling_code = ] | |||

| |cctld = ] | |||

| | cctld = ]<sup></sup> | |||

| | official_website = | |||

| | footnote_a = Also .eu, shared with other European Union member states | |||

| |footnote_a = {{note|a|a}} The area of Poland, as given by the Central Statistical Office, is {{convert|312679|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}, of which {{convert|311888|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}} is land and {{convert|791|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}} is internal water surface area.<ref name="CSO_2008" /> | |||

| }} | |||

| |footnote_b = {{note|b|b}} The adoption of Christianity in Poland is seen by many Poles, regardless of their religious affiliation or lack thereof, as one of the most significant events in their country's history, as it was used to unify the tribes in the region.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=39SoSG4NGAoC&pg=PA77&lpg=PA77&dq=poland%27s+millennium&sig=uQ-qK9oxqMuHmVvZJj8lszrm1 |title=Disruptive Religion: The Force of Faith in Social-movement Activism |work=Books.google.com |date= |accessdate=9 September 2013}}</ref> | |||

| <!----ORPHANED: | |||

| |footnote_? = {{note|?|?}} See, however, ]. | |||

| |footnote_? = {{note|?|?}} Although not ]s, ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] are used in ].{{Citation needed|date=March 2017}} | |||

| -----> | |||

| |area_magnitude = 1 E11 | |||

| }}<!-- | |||

| PLEASE DO NOT make any changes to the following section before discussing them on the discussion page (Talk:Poland). Thank you. | |||

| ------> | |||

| '''Poland''' |

'''Poland'''<!-- Do not add English pronunciation per ]. -->,{{efn|{{langx|pl|Polska}} {{IPA|pl|ˈpɔlska||Pl-Polska.ogg}}}} officially the '''Republic of Poland''',{{efn|{{langx|pl|] Polska|links=no}} {{IPA|pl|ʐɛt͡ʂpɔsˈpɔlita ˈpɔlska||Pl-Rzeczpospolita Polska.ogg}}}} is a country in ]. It extends from the ] in the north to the ] and ] in the south, bordered by ] and ]{{efn|], an ] of Russia}} to the northeast, ] and ] to the east, ] and the ] to the south, and ] to the west. The territory is characterised by a varied landscape, diverse ecosystems, and ] climate. Poland is composed of ] and is the fifth most populous ] (EU), with over 38 million people, and the ] by land area, covering a combined area of {{convert|312696|km2|abbr=on}}. The capital and ] is ]; other major cities include ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | ||

| ] dates to the ], with continuous settlement since the end of the ]. Culturally diverse throughout ], in the ] the region became inhabited by the ] tribal ], who gave ]. The process of establishing statehood coincided with the conversion of a ] to Christianity, under the auspices of the ] in 966. The ] emerged in 1025, and in 1569 cemented its long-standing ], thus forming the ]. At the time, the Commonwealth was one of the ] of Europe, with an ] and a ] political system, which adopted ] in 1791. | |||

| The establishment of a Polish state can be traced back to 966, when ],<ref name="A Concise History of Poland" /> ruler of a territory roughly coextensive with that of present-day Poland, converted to ]. The ] was founded in 1025, and in 1569 it cemented ] with the ] by signing the ]. This union formed the ], one of the largest (about 1 million km²) and most populous countries of 16th and 17th century Europe, with a ] political system<ref>Norman Davies, ''Europe: A History'', Pimlico 1997, p. 554: ''Poland-Lithuania was another country which experienced its 'Golden Age' during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The realm of the last Jagiellons was absolutely the largest state in Europe''</ref><ref name="Wandycz2001-66">{{cite book|author=Piotr Stefan Wandycz|title=The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m5plR3x6jLAC&pg=PA66|accessdate=13 August 2011|year=2001|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=978-0-415-25491-5|page=66}}</ref> which adopted Europe's first written national constitution, the ]. | |||

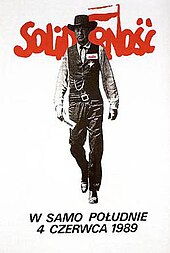

| With the passing of the prosperous ], the country was ] at the end of the 18th century. Poland regained its ] at the end of ] in 1918 with the creation of the ], which emerged ] in ] of the ] period. In September 1939, the ] by ] ] ] marked the beginning of ], which resulted in ] and millions of ]. Forced into the ] in the global ], the ] was a founding signatory of the ]. Through the emergence and contributions of the ], the ] was ] and Poland re-established itself as a ] in 1989, as the ] of its neighbours. | |||

| Following the ] at the end of the 18th century, Poland ] in 1918 with the ]. In September 1939, ] started with the ] by ], followed by the ] invading Poland in accordance with the ]. More than six million Poles died in the war.<ref name="posterum0">Project in Posterum, Retrieved 20 September 2013.</ref><ref name=szma>] & Wojciech Materski, ''Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami'', Warsaw, IPN 2009, {{ISBN|978-83-7629-067-6}} ( {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130201065133/http://niniwa2.cba.pl/polska_1939_1945.htm |date=1 February 2013 }})</ref> ], the ] was established as a ] under ].<ref>Rao, B. V. (2006), History of Modern Europe Ad 1789–2002: A.D. 1789–2002, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.</ref> In the aftermath of the ], most notably through the emergence of the ], Poland established itself as a ] republic. | |||

| Poland is a ] with its ] comprising the ] and the ]. Considered a ], it is a ] and ] that is the ] in the ] by nominal ] and the ]. Poland enjoys a ], safety, and ], as well as free ] and ]. The country has 17 ] ], 15 of which are cultural. Poland is a founding member state of the United Nations and a member of the ], ], ], and the European Union (including the ]). | |||

| Poland is a ] and ]<!-- Regional power of Central and Eastern Europe only --> as well as a possible ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://seekingalpha.com/article/115133-japan-turkey-poland-mexico-the-rising-world-powers|title=Japan, Turkey, Poland, Mexico the Rising World Powers?|first=Research|last=Recap|date=16 January 2009|publisher=|accessdate=23 July 2017}}</ref> It has the eighth largest and one of the most dynamic ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://multishoring.info/market-news/bloomberg-businessweek-%E2%80%9Ehow-poland-became-europes-most-dynamic-economy%E2%80%9D/|title=Bloomberg Businessweek: "How Poland Became Europe’s Most Dynamic Economy" -|publisher=|accessdate=14 April 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-11-27/how-poland-became-europes-most-dynamic-economy|title=How Poland Became Europe's Most Dynamic Economy|date=27 November 2013|publisher=|accessdate=14 April 2017|via=www.bloomberg.com}}</ref> simultaneously achieving a very high rank on the ].<ref name="Human Development Index and its components" /> Additionally, the ] is the largest and most important in ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.fio.pl/stocks-investments/stocks/stocks-poland|title=Warsaw Stock Exchange, Poland, stocks, investing online – Fio bank|publisher=|accessdate=9 April 2017}}</ref> Poland is a ]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.isi-web.org/index.php/resources/developing-countries|title=Developing Countries – isi-web.org|first=Justin van der|last=Veeke|publisher=|accessdate=24 April 2017}}</ref> and ] country, which maintains a ]<ref name="worldbank8" /> along with very high standards of ], ],<ref> Numbeo Quality of Life Index 2015 Mid Year</ref> safety, education and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.city-safe.com/danger-rankings/|title=World's Safest Countries Ranked — CitySafe|publisher=|accessdate=14 April 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thenews.pl/1/9/Artykul/272767,Poland-25th-worldwide-in-expat-ranking|title=Poland 25th worldwide in expat ranking|publisher=|accessdate=14 April 2017}}</ref> According to the ], Poland has a leading school ] in Europe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2016/01/22/polands-education-system-leading-in-europe|title=Poland’s Education System: Leading in Europe|publisher=|accessdate=26 April 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oslo.msz.gov.pl/no/nyheter/oecd_education_ranking_2015|title=Latest OECD education ranking places Poland 5th in Europe and 11th in the world. Polish schools given top grades|website=www.oslo.msz.gov.pl|accessdate=5 July 2017}}</ref> The country provides free ], state-funded ] and a ] system for all citizens.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://eures.praca.gov.pl/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=81&Itemid=114|title=Social security in Poland|first=|last=Administrator|publisher=|accessdate=24 April 2017|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160312084711/https://eures.praca.gov.pl/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=81&Itemid=114|archivedate=12 March 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.europe-cities.com/destinations/poland/health/|title=Healthcare in Poland – Europe-Cities|publisher=|accessdate=24 April 2017}}</ref> Having an extensive history, Poland has developed a ], including numerous ]. It has 15 ] ], 14 of which are cultural.<ref name="Poland – UNESCO World Heritage Centre" /> Poland is a member state of the ], the ], the ], ], the ], the ], and the ]. | |||

| == Etymology == |

== Etymology == | ||

| {{Main| |

{{Main|Names of Poland}} | ||

| The native ] name for Poland is {{lang|pl|Polska}}.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Thompson |first=Wayne C. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lttJEAAAQBAJ&dq=%22name%2Bpoland%2B%2522polska%2522%2Bderived%22&pg=PA322 |title=Nordic, Central, and Southeastern Europe 2020–2022 |date=2021 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers |isbn=978-1-4758-5626-2 |location=Blue Ridge Summit |page=322 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=7 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240207011846/https://books.google.com/books?id=lttJEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA322&dq=%22name%2Bpoland%2B%2522polska%2522%2Bderived%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> The name is derived from the ], a ] tribe who inhabited the ] basin of present-day ] region (6th–8th century CE).<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Lukowski |first1=Jerzy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NpMxTvBuWHYC&dq=%22polanie%2Bpoland%2Bwarta%2Bhistory%22&pg=PA4 |title=A Concise History of Poland |last2=Zawadzki |first2=Hubert |date=2001 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=0-521-55109-9 |location=Cambridge |page=4 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=4 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204080145/https://books.google.com/books?id=NpMxTvBuWHYC&pg=PA4&dq=%22polanie%2Bpoland%2Bwarta%2Bhistory%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> The tribe's name stems from the ] noun ''pole'' meaning field, which itself originates from the ] word ''*pleh₂-'' indicating flatland.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lehr-Spławiński |first=Tadeusz |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EjJHAAAAIAAJ&q=Je%25CC%25A8zyk%2Bpolski%2B:%2Bpochodzenie,%2Bpowstanie,%2Brozwo%25CC%2581j |title=Język polski. Pochodzenie, powstanie, rozwój |date=1978 |publisher=Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe |location=Warszawa (Warsaw) |page=64 |language=Polish |oclc=4307116 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235955/https://books.google.com/books?id=EjJHAAAAIAAJ&q=Je%25CC%25A8zyk%2Bpolski%2B:%2Bpochodzenie,%2Bpowstanie,%2Brozwo%25CC%2581j |url-status=live }}</ref> The etymology alludes to the ] of the region and the flat landscape of Greater Poland.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Potkański |first=Karol |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=b78eAAAAMAAJ&q=p%25C5%2582aska%2520wielkopolska%2520polanie |title=Pisma pośmiertne. Granice plemienia Polan |date=2004 |publisher=Polska Akademia Umiejętności |isbn=978-83-7063-411-7 |volume=1 |location=Kraków |page=423 |language=Polish |orig-date=1922 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235906/https://books.google.com/books?id=b78eAAAAMAAJ&q=p%25C5%2582aska%2520wielkopolska%2520polanie |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Everett-Heath |first=John |title=The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names |date=2019 |publisher=University Press |isbn=978-0-19-190563-6 |location=Oxford |chapter=Poland (Polska) |author-link=John Everett-Heath |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ufkFEAAAQBAJ&dq=%22poland%2Bfield%2Bpolanie%22&pg=PT1498 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=4 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204080136/https://books.google.com/books?id=ufkFEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT1498&dq=%22poland%2Bfield%2Bpolanie%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> During the ], the ] form ''Polonia'' was widely used throughout Europe.<ref name="Buko 2014">{{Cite book |last=Buko |first=Andrzej |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VAOjBQAAQBAJ |title=Bodzia. A Late Viking-Age Elite Cemetery in Central Poland |date=2014 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-28132-5 |location=Leiden |pages=36, 62 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=7 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230407051434/https://books.google.com/books?id=VAOjBQAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The origin of the name ''Poland'' derives from the ] tribe of ] (''Polanie'') that inhabited the ] basin of the historic ] region starting in the 6th century. The origin of the name ''Polanie'' itself derives from the early Slavic word ''pole'' (field). In some languages, such as Hungarian, Lithuanian, Persian and Turkish, the exonym for Poland is ] (''Lechici''), which derives from the name of a semi-legendary ruler of Polans, ]. | |||

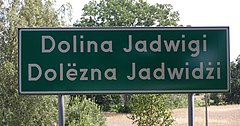

| The country's alternative archaic name is '']'' and its root syllable remains in official use in several languages, notably ], ], and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hannan |first=Kevin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YmrlAAAAMAAJ&q=poland%2Bpersian%2Blithuanian%2Bhungarian%2Blechitic |title=Language and Identity in a West Slavic Borderland: The Case of Teschen Silesia |date=1994 |publisher=University of Texas |location=Austin |page=127 |oclc=35825118 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235904/https://books.google.com/books?id=YmrlAAAAMAAJ&q=poland%2Bpersian%2Blithuanian%2Bhungarian%2Blechitic |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] possibly derives from either ], a legendary ruler of the ], or from the ], a West Slavic tribe that dwelt on the south-easternmost edge of ].<ref name="Dabrowski 2014">{{Cite book |last=Dabrowski |first=Patrice M. |url={{GBurl|id=X__-DwAAQBAJ}} |title=Poland. The First Thousand Years |date=2014 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=978-1-5017-5740-2 |location=New York}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Kamusella |first=Tomasz |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=spRUEAAAQBAJ&dq=%22lendians%2Blech%2Bpoland%22&pg=PA9 |title=Words in Space and Time: A Historical Atlas of Language Politics in Modern Central Europe |date=2022 |publisher=Central European University Press |isbn=978-963-386-418-0 |location=Budapest |page=9 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=4 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204080203/https://books.google.com/books?id=spRUEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA9&dq=%22lendians%2Blech%2Bpoland%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> The origin of the tribe's name lies in the ] word ''lęda'' (plain).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Małecki |first=Antoni |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dYwBAAAAMAAJ&q=Lechici%2Bw%2B%25C5%259Bwietle%2Bhistorycznej%2Bkrytyki |title=Lechici w świetle historycznej krytyki |date=1907 |publisher=Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich |isbn=978-83-65746-64-1 |location=Lwów (Lviv) |page=37 |language=Polish |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235910/https://books.google.com/books?id=dYwBAAAAMAAJ&q=Lechici%2Bw%2B%25C5%259Bwietle%2Bhistorycznej%2Bkrytyki |url-status=live }}</ref> Initially, both names ''Lechia'' and ''Polonia'' were used interchangeably when referring to Poland by chroniclers during the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Andersson |first1=Theodore Murdock |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lrdcDwAAQBAJ&dq=%22The%2BEarliest%2BIcelandic%2BChronicle%2Bof%2Bthe%2BNorwegian%2BKings%2B%25281030-1157%2529%2B2000%22&pg=PR4 |title=The Earliest Icelandic Chronicle of the Norwegian Kings (1030–1157) |last2=Morkinskinna |first2=Ellen Gade |date=2000 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=978-0-8014-3694-9 |location=Ithaca |page=471 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=4 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204080133/https://books.google.com/books?id=lrdcDwAAQBAJ&pg=PR4&dq=%22The%2BEarliest%2BIcelandic%2BChronicle%2Bof%2Bthe%2BNorwegian%2BKings%2B%25281030-1157%2529%2B2000%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| Line 136: | Line 130: | ||

| === Prehistory and protohistory === | === Prehistory and protohistory === | ||

| {{Main|Bronze |

{{Main|Stone Age Poland|Bronze and Iron Age Poland|Poland in antiquity|Early Slavs|West Slavs|Lechites|Poland in the Early Middle Ages}} | ||

| ], ] settlement in ], |

], ] settlement in ], 8th century BC]] | ||

| The first ] archaic humans and '']'' species settled what was to become Poland approximately 500,000 years ago, though the ensuing hostile climate prevented early humans from founding more permanent encampments.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fabisiak |first=Wojciech |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g_8jAQAAIAAJ&q=500%2520000%2520lat%2520temu%2520polska%2520homo%2520erectus |title=Dzieje powiatu wrocławskiego |date=2002 |publisher=Starostwo Powiatowe |isbn=978-83-913985-3-1 |location=Wrocław |page=9 |language=pl |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235907/https://books.google.com/books?id=g_8jAQAAIAAJ&q=500%2520000%2520lat%2520temu%2520polska%2520homo%2520erectus |url-status=live }}</ref> The arrival of '']'' and ] coincided with the climatic discontinuity at the end of the ] (] 10,000 BC), when Poland became habitable.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Jurek |first=Krzysztof |title=Poznać przeszłość 1. Karty pracy ucznia. Poziom podstawowy |date=2019 |publisher=Nowa Era |isbn=978-83-267-3653-7 |location=Warszawa (Warsaw) |page=93 |language=pl}}</ref> ] excavations indicated broad-ranging development in that era; the earliest evidence of European cheesemaking (5500 BC) was discovered in Polish ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Subbaraman |first=Nidhi |date=12 December 2012 |title=Art of cheese-making is 7,500 years old |url=http://www.nature.com/news/art-of-cheese-making-is-7-500-years-old-1.12020 |journal=Nature News |doi=10.1038/nature.2012.12020 |s2cid=180646880 |access-date=7 August 2021 |archive-date=8 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210508085311/https://www.nature.com/news/art-of-cheese-making-is-7-500-years-old-1.12020 |url-status=live | issn=0028-0836}}</ref> and the ] is incised with the earliest known depiction of what may be a wheeled vehicle (3400 BC).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Attema |first1=P. A. J. |last2=Los-Weijns |first2=Ma |last3=Pers |first3=N. D. Maring-Van der |date=December 2006 |title=Bronocice, Flintbek, Uruk, Jebel Aruda and Arslantepe: The Earliest Evidence Of Wheeled Vehicles In Europe And The Near East |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qqEqjtKJQ3YC&dq=%22Bronocice,+Flintbek,+Uruk,+Jebel+Aruda+and+Arslantepe:+The+Earliest+Evidence+Of+Wheeled+Vehicles+In+Europe+And+The+Near+East%22&pg=PA10 |journal=Palaeohistoria |publisher=] |volume=47 |pages=10–28 (11) |isbn=9789077922187}}</ref> | |||

| Historians have postulated that throughout ], many distinct ethnic groups populated the regions of what is now Poland. The ethnicity and linguistic affiliation of these groups have been hotly debated; the time and route of the original settlement of ] in these regions lacks written records and can only be defined as fragmented.<ref name="muzeumczestochowa.pl">{{cite book | url=http://www.muzeumczestochowa.pl/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/folder.pdf | title=Z mroku dziejów. Kultura Łużycka | publisher=Muzeum Częstochowskie. Rezerwat archeologiczny (Museum of Częstochowa) | year=2007 | accessdate=9 January 2013 |author1=Maciej Kosiński |author2=Magdalena Wieczorek-Szmal | pages=3–4 | quote=Możemy jedynie stwierdzić, że kultura łużycka nie tworzyła jednej zwartej całości. Jak się wydaje, jej skład etniczny był niejednorodny. | isbn=978-83-60128-11-4 | format=PDF file, direct download 1.95 MB}}</ref> | |||

| The period spanning the ] and the ] (1300 BC–500 BC) was marked by an increase in population density, establishment of ]d settlements (]) and the expansion of ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harding |first=Anthony |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XoxoAgAAQBAJ&dq=%22bronze%2Bage%2Bpoland%2Blusatian%22&pg=PA772 |title=The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age |date=2020 |publisher=University Press |isbn=978-0-19-885507-1 |location=Oxford |pages=766–783 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002180454/https://books.google.com/books?id=XoxoAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA772&dq=%22bronze+age+poland+lusatian%22 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Price |first=T. Douglas |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IZ_KBwAAQBAJ&dq=%22lusatian%2Bculture%2B1300%2BBC%2B%25E2%2580%2593%2B500%2BBC%22&pg=PA212 |title=Ancient Scandinavia: an archaeological history from the first humans to the Vikings |date=2015 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-023198-9 |location=New York |page=212 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002180455/https://books.google.com/books?id=IZ_KBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA212&dq=%22lusatian+culture+1300+BC+%E2%80%93+500+BC%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> A significant archaeological find from ] is a fortified settlement at ], attributed to the Lusatian culture of the ] (mid-8th century BC).<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Ring |first1=Trudy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yfPYAQAAQBAJ&q=biskupin&pg=PA96 |title=Northern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places |last2=Watson |first2=Noelle |last3=Schellinger |first3=Paul |date=28 October 2013 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-63944-9 |language=en |access-date=31 March 2019 |archive-date=24 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210824094046/https://books.google.com/books?id=yfPYAQAAQBAJ&q=biskupin&pg=PA96 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The most famous archaeological find from ] is the ] fortified settlement (now reconstructed as an open-air museum), dating from the ] of the early ], around 700 BC. The Slavic groups who would form Poland migrated to these areas in the second half of the 5th century AD. Up until the creation of ] state and his subsequent conversion to Christianity in 966 AD, the main religion of Slavic tribes that inhabited the geographical area of present-day Poland was ]. With the ] the Polish rulers accepted Christianity and the religious authority of the ]. However, the transition from paganism was not a smooth and instantaneous process for the rest of the population as evident from the ].<ref name="Labuda1992">{{cite book |author=Gerard Labuda |title=Mieszko II król Polski: 1025–1034 : czasy przełomu w dziejach państwa polskiego |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Gb8gAAAAIAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=1032 |accessdate=26 October 2014 |year=1992 |publisher=Secesja |isbn=978-83-85483-46-5 |page=112 |quote=... w wersji Anonima Minoryty mówi się znowu, iż w Polsce "paliły się kościoły i klasztory", co koresponduje w przekazaną przez Anonima Galla wiadomością o zniszczeniu kościołów katedralnych w Gnieźnie...}}</ref> | |||

| Throughout ] (400 BC–500 AD), many distinct ancient populations inhabited the territory of present-day Poland, notably ], ]n, ], ], ] and ] tribes.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Davies |first=Norman |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mkcSDAAAQBAJ |title=Heart of Europe. The Past in Poland's Present |date=2001 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-280126-5 |location=Oxford |page=247 |language=en |author-link=Norman Davies |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=18 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230518111254/https://books.google.com/books?id=mkcSDAAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> Furthermore, archaeological findings confirmed the presence of ] sent to protect the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Zdziebłowski |first=Szymon |date=9 May 2018 |title=Archaeologist: We have evidence of the presence of Roman legionaries in Poland |url=https://scienceinpoland.pap.pl/en/news/news%2C29414%2Carchaeologist-we-have-evidence-presence-roman-legionaries-poland.html |access-date=8 August 2021 |website=Science in Poland |publisher=Polish Ministry of Education and Science |archive-date=15 February 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220215225927/https://scienceinpoland.pap.pl/en/news/news,29414,archaeologist-we-have-evidence-presence-roman-legionaries-poland.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] emerged following the ] around the 6th century AD;<ref name="Buko 2014" /> they were ] and may have included assimilated remnants of peoples that earlier dwelled in the area.<ref>{{Citation |last=Mielnik-Sikorska |first=Marta |title=The History of Slavs Inferred from Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequences |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=e54360 |year=2013 |bibcode=2013PLoSO...854360M |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0054360 |pmc=3544712 |pmid=23342138 |display-authors=etal |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Brather |first=Sebastian |year=2004 |title=The Archaeology of the Northwestern Slavs (Seventh To Ninth Centuries) |journal=East Central Europe |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=78–81 |doi=10.1163/187633004x00116}}</ref> Beginning in the early 10th century, the ] would come to dominate other ] tribes in the region, initially forming a tribal federation and later a centralised monarchical state.<ref>{{Cite book |last=McKenna |first=Amy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ef2cAAAAQBAJ&dq=%22polanie%2Btribal%2Bmonarchy%22&pg=PA132 |title=Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland |date=2013 |publisher=Britannica Educational Publishing |isbn=978-1-61530-991-7 |page=132 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002180456/https://books.google.com/books?id=Ef2cAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA132&dq=%22polanie+tribal+monarchy%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Piast dynasty === | |||

| {{Main|History of Poland during the Piast dynasty|Civitas Schinesghe|Gesta principum Polonorum}} | |||

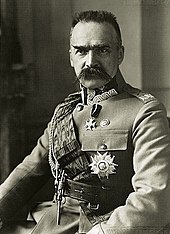

| ], who is considered to be the creator of the Polish state, c. 960–996]] | |||

| === Kingdom of Poland === | |||

| Poland began to form into a recognizable unitary and ] around the middle of the 10th century under the ]. Poland's first ] ruler, ], accepted Christianity with the ] in 966, as the new ] of his subjects. The bulk of ] in the course of the next few centuries. In 1000, ], continuing the policy of his father Mieszko, held a ] and created the ] of ] and the ]s of ], ], and ]. However, the pagan unrest led to the transfer of the capital to Kraków in 1038 by ].<ref name="Prazmowska2011">{{cite book |author=Anita J. Prazmowska |title=A History of Poland |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r_0-BjHIkh4C&lpg=PT34&pg=PT28#v=onepage&q&f=false |accessdate=26 October 2014 |date=13 July 2011 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-0-230-34537-9 |pages=34–35}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|History of Poland during the Piast dynasty|History of Poland during the Jagiellonian dynasty|Baptism of Poland|Kingdom of Poland}} | |||

| ], whose acceptance of Christianity under the auspices of the ] and the ] marked the beginning of statehood in 966]] | |||

| Poland began to form into a recognisable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dabrowski |first=Patrice |title=Poland: The First Thousand Years |date=2014 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=978-1-5017-5740-2 |location=Ithaca |pages=21–22}}</ref> In 966 the ruler of the Polans, ], accepted Christianity under the auspices of the ] with the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ramet |first=Sabrina |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=D2gpDwAAQBAJ |title=The Catholic Church in Polish History. From 966 to the Present |date=2017 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US |isbn=978-1-137-40281-3 |location=New York |page=15 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=14 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230414113421/https://books.google.com/books?id=D2gpDwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> In 968, a missionary ] was established in ]. An ] titled ] first defined Poland's geographical boundaries with its capital in ] and affirmed that its monarchy was under the protection of the ].<ref name="Curta 2016">{{Cite book |last1=Curta |first1=Florin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dgF9DQAAQBAJ&dq=%22dagome%2Biudex%2Bgniezno%2Bpoland%22&pg=PA468 |title=Great Events in Religion |last2=Holt |first2=Andrew |date=2016 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-61069-566-4 |location=Santa Barbara |pages=468, 480–481 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002180512/https://books.google.com/books?id=dgF9DQAAQBAJ&pg=PA468&dq=%22dagome+iudex+gniezno+poland%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> The country's early origins were described by ] in {{Lang|la|]}}, the oldest Polish chronicle.<ref>{{Citation |title=Gesta Principum Polonorum / The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles |volume=3 |pages=87–211 |year=2003 |editor-last=Knoll |editor-first=Paul W. |series=Central European Medieval Texts, General Editors János M. Bak, Urszula Borkowska, Giles Constable & Gábor Klaniczay |place=Budapest/ New York |publisher=Central European University Press |isbn=978-963-9241-40-4 |editor2-last=Schaer |editor2-first=Frank}}</ref> An important national event of the period was the ] of ], who was killed by ] pagans in 997 and whose remains were reputedly bought back for their weight in gold by Mieszko's successor, ].<ref name="Curta 2016" /> | |||

| ] of Poland, who ruled the nation between 1025 and 1031.]] | |||

| In 1000, at the ], Bolesław obtained the right of ] from ], who assented to the creation of additional bishoprics and an archdioceses in Gniezno.<ref name="Curta 2016" /> Three new dioceses were subsequently established in ], ], and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ożóg |first=Krzysztof |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VbouAQAAIAAJ&q=gniezno%2520krakow%2520wroclaw%2520ko%25C5%2582obrzeg |title=The Role of Poland in the Intellectual Development of Europe in the Middle Ages |date=2009 |publisher=Societas Vistulana |isbn=978-83-61033-36-3 |location=Kraków |page=7 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235925/https://books.google.com/books?id=VbouAQAAIAAJ&q=gniezno%2520krakow%2520wroclaw%2520ko%25C5%2582obrzeg |url-status=live }}</ref> Also, Otto bestowed upon Bolesław royal ] and a replica of the ], which were later used at his coronation as the first ] in {{Circa|1025}}, when Bolesław received permission for his coronation from ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Urbańczyk |first=Przemysław |title=Bolesław Chrobry – lew ryczący |date=2017 |publisher=Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika |isbn=978-8-323-13886-0 |location=Toruń |pages=309–310 |language=pl}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Davies |first=Norman |title=God's Playground: A History of Poland |title-link=God's Playground |publisher=] |year=2005a |isbn=978-0-231-12817-9 |edition=2nd |volume=I |location=Oxford |pages=27–28 |author-link=Norman Davies}}</ref> Bolesław also expanded the realm considerably by seizing parts of German ], Czech ], ], and southwestern regions of the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Kumor |first1=Bolesław |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3LrYAAAAMAAJ&q=boles%25C5%2582aw%2520morawy%2520%25C5%2582u%25C5%25BCyce%2520w%25C4%2599gry |title=Historia Kościoła w Polsce |last2=Obertyński |first2=Zdzisław |date=1974 |publisher=Pallottinum |location=Poznań |page=12 |oclc=174416485 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235917/https://books.google.com/books?id=3LrYAAAAMAAJ&q=boles%25C5%2582aw%2520morawy%2520%25C5%2582u%25C5%25BCyce%2520w%25C4%2599gry |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1109, Prince ] defeated the King of Germany ] at the ], stopping the German march into Poland. The significance of the event was documented by ] in ].<ref>{{Citation |editor-last=Knoll |editor-first=Paul W. |editor2-last=Schaer |editor2-first=Frank |title=Gesta Principum Polonorum / The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles |place=Budapest/ New York |publisher=Central European University Press |year=2003 |series=Central European Medieval Texts, General Editors János M. Bak, Urszula Borkowska, Giles Constable & Gábor Klaniczay, Volume 3 |isbn=963-9241-40-7 |pages=87–211}}</ref> In 1138, Poland fragmented into several smaller duchies when Bolesław divided his lands among his sons. In 1226, ], one of the regional ] dukes, invited the ] to help him fight the ] ] pagans; a decision that led to centuries of warfare with the Knights. In 1264, the ] or the General Charter of Jewish Liberties introduced numerous right for the Jews in Poland, leading to a nearly autonomous "nation within a nation".<ref name="Dembkowski/Lublin">{{cite book |title=The union of Lublin, Polish federalism in the golden age |first=Harry E. |last=Dembkowski |publisher=East European Monographs, 1982 |isbn= 978-0-88033-009-1 |page=271 |url=https://books.google.com/?id=svAaAAAAMAAJ&q=poland+lithuania+1588+slavery&dq=poland+lithuania+1588+slavery |year =1982 }}</ref> | |||

| ] is the only Polish king to receive the title of ''Great''. He built extensively during his reign, and reformed the Polish army along with the country's legal code, 1333–70]] | |||

| In the middle of the 13th century, the Silesian branch of the Piast dynasty (] and ], ruled 1238–41) nearly succeeded in uniting the Polish lands, but the ] invaded the country from the east and defeated the combined Polish forces at the ] where Duke Henry II the Pious died. In 1320, after a number of earlier unsuccessful attempts by regional rulers at uniting the Polish dukedoms, ] consolidated his power, took the throne and became the first king of ]. His son, ] (reigned 1333–70), has a reputation as one of the greatest Polish kings, and gained wide recognition for improving the country's infrastructure.<ref name="Sokol1992-60">{{cite book|author=Stanley S. Sokol|title=The Polish Biographical Dictionary: Profiles of Nearly 900 Poles who Have Made Lasting Contributions to World Civilization|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IGOhdT-w1eIC&pg=PA60|year=1992|publisher=Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers|isbn=978-0-86516-245-7|page=60}}</ref><ref name="Publishing2013">{{cite book|author=Britannica Educational Publishing|title=Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ef2cAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA139|date=1 June 2013|publisher=Britanncia Educational Publishing|isbn=978-1-61530-991-7|page=139}}</ref> He also extended royal protection to ], and encouraged their immigration to Poland.<ref name="Sokol1992-60" /><ref name="Haumann2002">{{cite book|author=Heiko Haumann|title=A History of East European Jews|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ypcWuuGVvX8C&pg=PA4|year=2002|publisher=Central European University Press|isbn=978-963-9241-26-8|page=4}}</ref> Casimir III realized that the nation needed a class of educated people, especially lawyers, who could codify the country's laws and administer the courts and offices. His efforts to create an institution of higher learning in Poland were finally rewarded when ] granted him permission to open the ]. | |||

| The transition from ] in Poland was not instantaneous and resulted in the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Gerard Labuda |url={{GBurl|id=Gb8gAAAAIAAJ|q=1032}} |title=Mieszko II król Polski: 1025–1034: czasy przełomu w dziejach państwa polskiego |publisher=Secesja |year=1992 |isbn=978-83-85483-46-5 |page=112 |quote=... w wersji Anonima Minoryty mówi się znowu, iż w Polsce "paliły się kościoły i klasztory", co koresponduje w przekazaną przez Anonima Galla wiadomością o zniszczeniu kościołów katedralnych w Gnieźnie... |access-date=26 October 2014}}</ref> In 1031, ] lost the title of king and fled amidst the violence.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Krajewska |first=Monika |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BnlGAQAAIAAJ&q=mieszko%2520II%2520w%25201031%2520utraci%25C5%2582%25201032%2520ksi%25C4%2585%25C5%25BC%25C4%2599 |title=Integracja i dezintegracja państwa Piastów w kronikach polskich Marcina Kromera oraz Marcina i Joachima Bielskich9 |date=2010 |publisher=W. Neriton |isbn=978-83-909852-1-3 |location=Warszawa (Warsaw) |page=82 |language=pl |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=25 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230725000011/https://books.google.com/books?id=BnlGAQAAIAAJ&q=mieszko%2520II%2520w%25201031%2520utraci%25C5%2582%25201032%2520ksi%25C4%2585%25C5%25BC%25C4%2599 |url-status=live }}</ref> The unrest led to the transfer of the capital to Kraków in 1038 by ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Anita J. Prazmowska |url={{GBurl|id=r_0-BjHIkh4C|pg=PT28}} |title=A History of Poland |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |year=2011 |isbn=978-0-230-34537-9 |pages=34–35 |access-date=26 October 2014}}{{Dead link|date=February 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> In 1076, ] re-instituted the office of king, but was banished in 1079 for murdering his opponent, ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Melton |first=J. Gordon |url={{GBurl|id=lD_2J7W_2hQC}} |title=Religious Celebrations. An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations |date=2011 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-59884-206-7 |location=Santa Barbara |page=834}}</ref> In 1138, the country ] into five principalities when ] divided his lands among his sons.<ref name="Dabrowski 2014" /> These were ], Greater Poland, ], ] and ], with intermittent hold over ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hourihane |first=Colum |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FtlMAgAAQBAJ&dq=%221138%2B%2522five%2522%2Bsilesia%2Bmazovia%2Bsandomierz%2Bpomerania%22&pg=RA4-PA14 |title=The Grove encyclopedia of medieval art and architecture |date=2012 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-539536-5 |volume=2 |location=New York |page=14 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002180502/https://books.google.com/books?id=FtlMAgAAQBAJ&pg=RA4-PA14&dq=%221138+%22five%22+silesia+mazovia+sandomierz+pomerania%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1226, ] invited the ] to aid in combating the ] Prussians; a decision that later led to centuries of warfare with the Knights.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Biber |first1=Tomasz |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AbYjAQAAIAAJ&q=konrad%2520mazowiecki%2520krzy%25C5%25BCacy%2520sprowadzi%25C5%2582 |title=Encyklopedia Polska 2000. Poczet władców |last2=Leszczyński |first2=Maciej |date=2000 |publisher=Podsiedlik-Raniowski |isbn=978-83-7212-307-7 |location=Poznań |page=47 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235942/https://books.google.com/books?id=AbYjAQAAIAAJ&q=konrad%2520mazowiecki%2520krzy%25C5%25BCacy%2520sprowadzi%25C5%2582 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] is the only Polish king to receive the title of ''Great''. He built extensively during his reign, and reformed the Polish army along with the country's civil and criminal laws, 1333–70.]] | |||

| In the first half of the 13th century, ] and ] aimed to unite the fragmented dukedoms, but the ] and the death of Henry II in ] hindered the unification.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Krasuski |first=Jerzy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vBcsAQAAMAAJ&q=henryk%2520pobo%25C5%25BCny%2520zjednoczenie |title=Polska-Niemcy. Stosunki polityczne od zarania po czasy najnowsze |date=2009 |publisher=Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich |isbn=978-83-04-04985-7 |location=Wrocław |page=53 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235916/https://books.google.com/books?id=vBcsAQAAMAAJ&q=henryk%2520pobo%25C5%25BCny%2520zjednoczenie |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Maroń |first=Jerzy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CASkn7zoJj8C |title=Legnica 1241 |date=1996 |publisher=Bellona |isbn=978-83-11-11171-4 |location=Warszawa (Warsaw) |language=pl |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=20 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230420034201/https://books.google.com/books?id=CASkn7zoJj8C |url-status=live }}</ref> As a result of the devastation which followed, depopulation and the demand for craft labour spurred a migration of ] into Poland, which was encouraged by the Polish dukes.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Davies |first=Norman |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vD7SWb5lXBAC&dq=%22germans%2Bflemish%2Binto%2Bpoland%2Bmongol%2Binvasion%22&pg=PA366 |title=Europe: A History |date=2010 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-820171-7 |location=New York |page=366 |orig-date=1996 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002180457/https://books.google.com/books?id=vD7SWb5lXBAC&pg=PA366&dq=%22germans+flemish+into+poland+mongol+invasion%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1264, the ] introduced unprecedented autonomy for the ], who came to Poland fleeing persecution elsewhere in Europe.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dembkowski |first=Harry E. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=svAaAAAAMAAJ&q=poland%2Blithuania%2B1588%2Bslavery |title=The union of Lublin, Polish federalism in the golden age |publisher=East European Monographs |year=1982 |isbn=978-0-88033-009-1 |page=271 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235935/https://books.google.com/books?id=svAaAAAAMAAJ&q=poland%2Blithuania%2B1588%2Bslavery |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The ] of the nobles began to develop under Casimir's rule, when in return for their ], the king made a series of concessions to the nobility, and establishing their legal status as superior to that of the townsmen. When Casimir the Great died in 1370, leaving no legitimate male heir, the ] came to an end. | |||

| In 1320, ] became the first king of ] since ] in 1296,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kula |first=Marcin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VBa1AAAAIAAJ&q=%25C5%2582okietek%25201320%2520zjednoczenie |title=Zupełnie normalna historia, czyli, Dzieje Polski zanalizowane przez Marcina Kulę w krótkich słowach, subiektywnie, ku pożytkowi miejscowych i cudzoziemców |date=2000 |publisher=Więzi |isbn=978-83-88032-27-1 |location=Warszawa (Warsaw) |pages=58–59 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235910/https://books.google.com/books?id=VBa1AAAAIAAJ&q=%25C5%2582okietek%25201320%2520zjednoczenie |url-status=live }}</ref> and the first to be crowned at ] in Kraków.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wróblewski |first=Bohdan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=unEWAQAAIAAJ&q=%25C5%2582okietek%25201320%2520szczerbiec |title=Jaki znak twój? Orzeł Biały |date=2006 |publisher=ZP Grupa |isbn=978-83-922944-3-6 |location=Piekary Śląskie |page=28 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230724235959/https://books.google.com/books?id=unEWAQAAIAAJ&q=%25C5%2582okietek%25201320%2520szczerbiec |url-status=live }}</ref> Beginning in 1333, the reign of ] was marked by developments in ], army, judiciary and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Stanley S. Sokol |url=https://archive.org/details/polishbiographic00soko |title=The Polish Biographical Dictionary: Profiles of Nearly 900 Poles who Have Made Lasting Contributions to World Civilization |publisher=Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers |year=1992 |isbn=978-0-86516-245-7 |page= |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Britannica Educational Publishing |url={{GBurl|id=Ef2cAAAAQBAJ|p=139}} |title=Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland |publisher=Britannica Educational Publishing |year=2013 |isbn=978-1-61530-991-7 |page=139}}</ref> Under his authority, Poland transformed into a major European power; he instituted Polish rule over ] in 1340 and imposed quarantine that prevented the spread of ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wróbel |first=Piotr |url=https://archive.org/details/easterneuropeint0000unse/page/10 |title=Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture |date=2004 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-57607-800-6 |editor-last=Frucht |editor-first=Richard C. |volume=1 |page= |chapter=Poland |quote=At the same time, when most of Europe was decimated by the Black Death, Poland developed quickly and reached the levels of the wealthiest countries of the West in its economy and culture. |access-date=8 April 2013 |chapter-url={{GBurl|id=lVBB1a0rC70C}}}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Magill |first=Frank N. |url={{GBurl|id=aBHSc2hTfeUC}} |title=The Middle Ages. Dictionary of World Biography |date=2012 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-136-59313-0 |volume=2 |location=Hoboken |page=210}}</ref> In 1364, Casimir inaugurated the ], one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in Europe.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Watson |first=Noelle |url={{GBurl|id=yfPYAQAAQBAJ}} |title=Northern Europe. International Dictionary of Historic Places |date=2013 |publisher=Routledge, Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-136-63944-9 |location=New York |page=388}}</ref> Upon his death in 1370, the Piast dynasty came to an end.<ref>{{Harvnb|Magill|2012|p=64}}</ref> He was succeeded by his closest male relative, ], who ruled Poland, ], and ] in a ].<ref name="Davies 2001">{{Harvnb|Davies|2001|p=256}}</ref> Louis' younger daughter ] became Poland's first female monarch in 1384.<ref name="Davies 2001" /> | |||

| During the 13th and 14th centuries, Poland became a destination for German, Flemish and to a lesser extent Walloon, Danish and Scottish migrants. Also, Jews and Armenians began to settle and flourish in Poland during this era (see ] and ]). | |||

| ] was fought against the ], and resulted in a decisive victory for the ], 15 July 1410]] | |||

| The ], a plague that ravaged Europe from 1347 to 1351 did not significantly affect Poland, and the country was spared from a major outbreak of the disease.<ref name="REF03" /><ref>{{cite book | |||

| | editor-last = Frucht | editor-first = Richard C. | |||

| | author-last = Wróbel | author-first = Piotr | |||

| | title = Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture | chapter = Poland | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=lVBB1a0rC70C | |||

| | access-date = 8 April 2013 | |||

| | date = 2004 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | volume = 1 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-57607-800-6 | |||

| | page = 10 | |||

| | quote = At the same time, when most of Europe was decimated by the Black Death, Poland developed quickly and reached the levels of the wealthiest countries of the West in its economy and culture. | |||

| }}</ref> The reason for this was the decision of Casimir the Great to quarantine the nation's borders. | |||

| In 1386, Jadwiga of Poland entered a marriage of convenience with ], the ], thus forming the ] and the ] which spanned the late ] and early ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Halecki |first=Oscar |title=Jadwiga of Anjou and the Rise of East-Central Europe |publisher=Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America |year=1991 |isbn=978-0-88033-206-4 |pages=116–117, 152 |author-link=Oscar Halecki}}</ref> The partnership between Poles and Lithuanians brought the vast multi-ethnic ] territories into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for its inhabitants, who coexisted in one of the largest European ] of the time.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Griessler |first=Christina |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=inb4DwAAQBAJ |title=The Visegrad Four and the Western Balkans |date=2020 |publisher=Nomos |isbn=978-3-7489-0113-6 |location=Baden-Baden |page=173 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=4 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404210019/https://books.google.com/books?id=inb4DwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Jagiellon dynasty === | |||

| {{Main|History of Poland during the Jagiellon dynasty|Renaissance in Poland}} | |||

| ] was fought against the ], and resulted in a decisive victory for the ], 15 July 1410.]] | |||

| In the Baltic Sea region, the struggle of Poland and Lithuania with the ] continued and culminated at the ] in 1410, where a combined Polish-Lithuanian army inflicted a decisive victory against them.<ref name="Wyrozumski 1986" /> In 1466, after the ], king ] gave royal consent to the ], which created the future ] under Polish suzerainty and forced the Prussian rulers to pay ].<ref name="Dabrowski 2014" /> The Jagiellonian dynasty also established dynastic control over the kingdoms of ] (1471 onwards) and Hungary.<ref name="Norman Davies 1996" /> In the south, Poland confronted the ] (at the ]) and the ], and in the east helped Lithuania to combat ].<ref name="Dabrowski 2014" /> | |||

| ] in ], seat of Polish kings from 1038 until the capital was moved to ] in 1596. The royal residence is an example of early ] architecture in Poland.]] | |||

| Poland was developing as a ] state, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly powerful ]. The '']'' act adopted by the Polish ] (parliament) in 1505, transferred most of the ] from the monarch to the Sejm, an event which marked the beginning of the period known as "Golden Liberty", when the state was ruled by the "free and equal" ]. ] movements made deep inroads into Polish Christianity, which resulted in the establishment of policies promoting religious tolerance, unique in Europe at that time.<ref name="LouthanCohen2011" /> This tolerance allowed the country to avoid most of the religious turmoil that spread over Europe during the 16th century.<ref name="LouthanCohen2011">{{cite book|author=Paul W. Knoll|chapter=Religious Toleration in Sixteenth-Century Poland. Political Realities and Social Constrains.|editor1=Howard Louthan|editor2=Gary B. Cohen|editor3=Franz A. J. Szabo|title=Diversity and Dissent: Negotiating Religious Difference in Central Europe, 1500–1800|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KuzLNXpa-hYC&pg=PA30|date=15 March 2011|publisher=Berghahn Books|isbn=978-0-85745-109-5|pages=30–45}}</ref> | |||

| Poland was developing as a ] state, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly powerful ] that confined the population to private manorial farmstead known as ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Frost |first=Robert I. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=245lDwAAQBAJ&dq=%22poland%2Bfeudal%2Bagricultural%2Bfolwark%2Bnobility%22&pg=PA242 |title=The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union 1385–1569 |date=2018 |publisher=University Press |isbn=978-0-19-880020-0 |volume=1 |location=Oxford |page=242 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002180501/https://books.google.com/books?id=245lDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA242&dq=%22poland+feudal+agricultural+folwark+nobility%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1493, ] sanctioned the creation of a ] (the Sejm) composed of a lower house, the chamber of deputies, and an upper house, the chamber of senators.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Graves |first=M. A. R. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R2rJAwAAQBAJ |title=The Parliaments of Early Modern Europe |date=2014 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-317-88433-0 |location=Hoboken |page=101 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=5 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405192005/https://books.google.com/books?id=R2rJAwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> The '']'' act adopted by the Polish ] in 1505, transferred most of the ] from the monarch to the parliament, an event which marked the beginning of the period known as ], when the state was ruled by the seemingly free and equal ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Graves|2014|pp=101, 197}}</ref> | |||

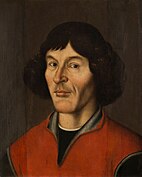

| The European ] evoked in late Jagiellon Poland (kings ] and ]) a sense of urgency in the need to promote a ], and during this period Polish culture and the nation's economy flourished. In 1543, ] a Polish astronomer from ], published his epochal work '']'' (''On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres''), and thereby became the first proponent of a predictive mathematical model confirming the ], which became the accepted basic model for the practice of modern astronomy. Another major figure associated with the era is the classicist poet ].<ref name="Gierowski" /> | |||

| ] in ], seat of ] from 1038 until the capital was moved to ] in 1596]] | |||

| === Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth === | |||

| {{Main|History of Poland in the Early Modern era (1569–1795)|Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth|Sarmatism}} | |||

| ] was an important development in the history of Poland, which extended religious freedoms and tolerance, and produced a first of its kind document in Europe, 28 January 1573.]] | |||

| The 1569 ] established the ], a more closely unified federal state with an ], but which was governed largely by the nobility, through a system of ] with a central parliament. The ] (1573) confirmed the religious freedom of all residents of Poland, which was extremely important for the stability of the multiethnic Polish society of the time.<ref name="Dembkowski/Lublin" /> ] was banned in 1588.<ref>{{cite book |title =The union of Lublin, Polish federalism in the golden age |first=Harry E. |last=Dembkowski |publisher=East European Monographs, 1982 |isbn= 978-0-88033-009-1 |page=271 |url=https://books.google.com/?id=svAaAAAAMAAJ&q=poland+lithuania+1588+slavery&dq=poland+lithuania+1588+slavery |year =1982 }}</ref> The establishment of the Commonwealth coincided with a period of stability and prosperity in Poland, with the union thereafter becoming a European power and a major cultural entity, occupying approximately one million square kilometers of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as an agent for the dissemination of ] through ] into areas of modern-day Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus and Western Russia. | |||

| The 16th century saw ] movements making deep inroads into Polish Christianity, which resulted in the establishment of policies promoting religious tolerance, unique in Europe at that time.<ref name="Knoll 2011" /> This tolerance allowed the country to avoid the religious turmoil and ] that beset Europe.<ref name="Knoll 2011">{{Cite book |last=Paul W. Knoll |title=Diversity and Dissent: Negotiating Religious Difference in Central Europe, 1500–1800 |publisher=Berghahn Books |year=2011 |isbn=978-0-85745-109-5 |editor-last=Howard Louthan |pages=30–45 |chapter=Religious Toleration in Sixteenth-Century Poland. Political Realities and Social Constrains. |editor-last2=Gary B. Cohen |editor-last3=Franz A.J. Szabo |chapter-url={{GBurl|id=KuzLNXpa-hYC|p=30}}}}</ref> In Poland, ] became the doctrine of the so-called ], who separated from their ] denomination and became the co-founders of global ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Houlden |first=J. L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mf7WCQAAQBAJ |title=Jesus in History, Legend, Scripture, and Tradition: A World Encyclopedia |date=2015 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-61069-804-7 |location=Denver, Colorado |pages=577–578 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=24 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230524182450/https://books.google.com/books?id=mf7WCQAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In the 16th and 17th centuries, ] suffered from a number of dynastic crises during the reigns of the ] kings ] and ] and found itself engaged in major conflicts with ], Sweden and the Ottoman Empire, as well as a series of minor ] uprisings.<ref name="gierowski" /> In 1610 Polish army under command ] ] seized Moscow after winning the ]. In 1611 the Tsar of Russia ] to the King of Poland. | |||

| The European ] evoked under ] and ] a sense of urgency in the need to promote a ].<ref name="Dabrowski 2014" /> During the ], the nation's economy and culture flourished.<ref name="Dabrowski 2014" /> The Italian-born ], daughter of the ] and queen consort to Sigismund I, made considerable contributions to ], ], language and court customs at ].<ref name="Dabrowski 2014" /> | |||

| ] at its greatest extent after the ]. During the first half of the 17th century, Poland covered an area of about {{convert|1,000,000|km|mi}}.]] | |||

| === Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth === | |||

| {{Main|History of Poland in the Early Modern era (1569–1795)|Crown of the Kingdom of Poland|Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth}} | |||

| ] at its greatest extent in 1619. At that time it was the largest country in Europe]] | |||

| The ] of 1569 established the ], a unified federal state with an ] that was largely governed by the nobility.<ref name="Butterwick 2021">{{Cite book |last=Butterwick |first=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g2cOEAAAQBAJ |title=The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1733–1795 |date=2021 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-25220-0 |pages=21, 14 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=4 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404210123/https://books.google.com/books?id=g2cOEAAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> The latter coincided with a period of prosperity. The Polish-dominated union thereafter became a leading power and a major cultural entity, exercising political control over parts of Central, ], ] and Northern Europe. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth occupied approximately {{convert|1|e6km2|sqmi|abbr=unit}} ] and was the largest state in Europe.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Parker |first=Geoffrey |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1GMlDwAAQBAJ |title=Global Crisis. War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century |date=2017 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-21936-4 |location=New Haven |page=122 |access-date=24 July 2023 |archive-date=5 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405150949/https://books.google.com/books?id=1GMlDwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Parker|2017|p=122}}</ref> Simultaneously, Poland imposed ] policies in newly acquired territories which were met with resistance from ethnic and religious minorities.<ref name="Butterwick 2021" /> | |||

| After the signing of ], Poland had in the years 1618–1621 an area of about 1 million km². | |||