| Revision as of 21:40, 31 January 2010 view sourceVirginian123 (talk | contribs)2 editsmNo edit summaryTag: references removed← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:48, 24 January 2025 view source Rupert Clayton (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers5,335 editsm →Vyborg–Petrozavodsk Offensive and breakthrough: en dash | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Finnish war against the Soviet Union (1941–44)}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|beg}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| |conflict=Continuation War | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} | |||

| |partof=] of ] | |||

| {{Use British English|date=April 2018}} | |||

| |image=] | |||

| {{Use shortened footnotes|date=January 2018}} | |||

| |caption=Finnish ] Ausf. G ]s. | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |date=25 June 1941–19 September 1944 | |||

| | conflict = Continuation War | |||

| |place=], ] and ] | |||

| | partof = the ] of ] | |||

| |result=Soviet victory, ] | |||

| | image = Finnish soldiers 1944.jpg | |||

| |combatant1={{FIN}}<br>{{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Italy}} ]<ref>On 17 May 1942 the International Naval Detachment K (with boats from Finland, Germany, and Italy) was deployed on Lake Ladoga. During its patrols, the Detachment interdicted the Leningrad supply route in the southern part of the lake, sinking one ].</ref> | |||

| | image_size = 300 | |||

| |combatant2= {{flagcountry|Soviet Union|1923}}<br>{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]{{#tag:ref|Although the United Kingdom formally declared war on Finland on 6 December 1941, there was only one British attack on Finnish soil — an air raid at Petsamo<ref name = "pvfkvi"/> carried out on 31 July 1941.|group="Notes"}} | |||

| | caption = Finnish soldiers at the ] of fortifications during the Soviet ] in June 1944 | |||

| |commander1={{flagicon|Finland}} ] | |||

| | date = 25 June 1941 – 19 September 1944 <br />({{Age in years, months, weeks and days|month1=06|day1=25|year1=1941|month2=09|day2=19|year2=1944}}) | |||

| |commander2={{flagicon|Soviet Union|1923}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Soviet Union|1923}} ] | |||

| | place = ], ], and ] area | |||

| |strength1= 500,000 Finns in Karelian Front{{#tag:ref|The most of the Finns served during the Finnish offensive in 1941 (approx. 500,000 men) and the Soviet offensive in August 1944 (528,000 men). Totally 700,000 men served in the theatre of war. Also number of people served in support groups, as 19,000 in labour group, 25,000 men in air-raid defence, and 40,000 women in different military tasks.|group="Notes"}}<ref name="Pikkujattilainen-kurenmaalentila" /><br/> | |||

| | territory = * ] ceded to the USSR | |||

| 220,000 Germans in Finnish Lapland{{#tag:ref|Germans were located in Finnish Lapland executing the ]. German forces did not participate in battles on the Karelian Front until 1944 (see ]).|group="Notes"}} | |||

| * ] leased to the USSR for 50 years{{refn|On 19 September 1955, Finland and the Soviet Union signed an agreement to return the Porkkala Peninsula to Finland. In January 1956, 12 years after its lease to the USSR, the Soviets withdrew from ] and the peninsula was returned to Finnish sovereignty.{{sfn|Jakobson|1969|pp=45-47}}|group="lower-alpha"}} | |||

| |strength2= 900,000–1,500,000 Soviets at a time<ref name="Manninen">Manninen, Ohto, ''Molotovin cocktail- Hitlerin sateenvarjo'', 1994. Painatuskeskus. ISBN 951-37-1495-0</ref> | |||

| * ] ] by Finland | |||

| |casualties1='''Finnish:'''<br>63,204 dead or missing {{#tag:ref|Finnish detailed death casualties: Dead, buried 33,565; Wounded, died of wounds 12,820; Dead, not buried later declared as dead 4,251; Missing, declared as dead 3,552; Died during prisoner of war 473; Other reasons (diseases, accidents, suicides) 7,932; Unknown 611|group="Notes"}}<ref name="Pikkujattilainen-kurenmaalentila">{{cite book |last1=Kurenmaa | first1=Pekka |last2=Lentilä | first2=Riitta |editor1-first=Jari |editor1-last=Leskinen |editor2-first=Antti |editor2-last=Juutilainen |title=Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen |edition=1st |publisher=Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö |date=2005 |pages=1150–1162 |chapter=Sodan tappiot |language=Finnish |isbn=951-0-28690-7}}</ref><br>158,000 wounded<br>939 civilians in air raids<ref name="Pikkujattilainen-kurenmaalentila" /><br>190 civilians by Soviet partisans<ref name="Pikkujattilainen-kurenmaalentila" /><br>2,377–3,500 ]{{#tag:ref|The official Soviet number was 2,377 POWs. Finnish researchers have estimated 3,500 POWs.|group="Notes"}}<ref name="Pikkujattilainen-malmi">{{cite book |last=Malmi | first=Timo |editor1-first=Jari |editor1-last=Leskinen |editor2-first=Antti |editor2-last=Juutilainen |title=Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen |edition=1st |publisher=Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö |date=2005 |pages=1022–1032 |chapter=Jatkosodan suomalaiset sotavangit |language=Finnish |isbn=951-0-28690-7}}</ref> | |||

| | result = {{ublist|Soviet victory}} | |||

| <br> | |||

| * ] | |||

| '''German:''' ? | |||

| * Start of ] | |||

| |casualties2= | |||

| | combatant1 = '''{{flag|Finland}}'''<br />'''{{flagcountry|Nazi Germany}}'''<br />'''Naval support:'''<br />{{flagcountry|Fascist Italy (1922–1943)}}{{refn|Italian participation was limited to the four motor torpedo boats of the ] serving in the international ] on ] during the summer and autumn of 1942.{{sfn|Zapotoczny|2017|p=123}}|group="lower-alpha"}} | |||

| 200,000 dead or missing <br>385,000 wounded<br>190,000 hospitalized due to sickness<br>64,000 captured<ref name="Manninen"/><br> | |||

| | combatant2 = '''{{flagcountry|Soviet Union|1936}}'''<br />'''Air support:'''<br />{{nowrap|{{flagcountry|United Kingdom}}{{refn|The United Kingdom formally declared war on Finland on 6 December 1941 along with four Commonwealth states largely for appearances' sake.{{sfn|Clements|2012|p=210}} Before that, the British conducted a ] on 31 July 1941,{{sfn|Sturtivant|1990|p=86}} and commenced ] to support air raids in the Murmansk area and train Soviet crews for roughly a month from September to October in 1941.<ref name="Benedict"/>|group="lower-alpha"}}}} | |||

| <br> | |||

| | commander1 = {{plainlist| | |||

| 4,000–7,000 civilian deaths{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}}{{#tag:ref|Excluding the victims of the ].|group="Notes"}} | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Finland}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Finland}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Finland}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Finland}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Finland}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | commander2 = {{plainlist| | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| * {{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | strength1 = {{nowrap|'''Average:''' 450,000 Finns{{sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|p=173}}}}<br />'''Peak:''' 700,000 Finns{{sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|p=173}}<br />'''1941:''' 67,000 Germans{{sfn|Ziemke|2002|pp=9, 391–393}}<br />{{nowrap|'''1944:''' 214,000 Germans{{sfn|Ziemke|2002|pp=9, 391–393}}}}<br />2,000 ]<br />1,000 ]<br />99 ]<br />550 aircraft<ref>{{cite web |title=History of the Finnish Air Force |url=https://ilmavoimat.fi/en/history |website=Ilmavoimat |access-date=23 July 2023 |quote="The Air Force had a total strength of 550 aircraft."}}</ref> | |||

| | strength2 = {{nowrap|'''Total:''' 900,000–1,500,000<ref name="Manninen">Manninen, Ohto, ''Molotovin cocktail- Hitlerin sateenvarjo'', 1994, Painatuskeskus, {{ISBN|951-37-1495-0}}</ref>}}<br />'''June 1941:''' 450,000{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|pp= 79, 269-271}}<br />'''June 1944:''' 650,000{{sfn|Manninen|1994|pp=277–282}}<br />1,506 tanks{{refn|This number was found through addition of the strength of the two ] present in the ] at the time of the invasion. The ] and the ] had 1,037 and 469 tanks respectively.{{sfn|Glantz|1998|p=127}} |group="lower-alpha"}}<br />1,382 aircraft{{refn|This number was found by adding number of 700 aircraft present in the eight ] in the ] in the Northern Front{{sfn|Jokipii|1999|p=301}} and the 682 aircraft in the ].{{sfn|Kirchubel|2013|p=151}}{{sfn|Kovalevsky|2009|pp=3-8}} |group="lower-alpha"}} | |||

| | casualties1 = {{plainlist| | |||

| <!-- See talk pages for including civilian casualties before amending --> | |||

| * '''Finnish''' | |||

| * 63,200 dead or missing{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|p=172}}{{Sfn|Nenye|Munter|Wirtanen|Birks|2016|p=320}} | |||

| * 158,000 wounded{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|p=172}} | |||

| * 2,370–3,500 ]{{sfn|Leskinen|Juutilainen|2005|pp=1022-1032}} | |||

| * 182 aircraft<ref>{{cite web |title=History of the Finnish Air Force |url=https://ilmavoimat.fi/en/history |website=Ilmavoimat |access-date=23 July 2023 |quote=The Air Force lost 182 aircraft destroyed in action or otherwise damaged beyond repair}}</ref> | |||

| * ''225,000 total casualties'' | |||

| * <small>Not including civilian casualties</small> | |||

| }} | |||

| {{plainlist| | |||

| * '''German''' | |||

| * 23,200 dead or missing | |||

| * 60,400 wounded | |||

| * ''84,000 total casualties''{{Sfn|Nenye|Munter|Wirtanen|Birks|2016|p=320}} | |||

| * <small>Not including civilian casualties</small> | |||

| }} | |||

| | casualties2 = {{plainlist| | |||

| <!-- See talk pages for including civilian casualties before amending; the subtle reference to siege of Leningrad is consensus from earlier discussions --> | |||

| * '''Soviet''' | |||

| * 250,000–305,000 dead<br /> or missing{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|pp= 79, 269-271}}{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|p=172}}{{Sfn|Nenye|Munter|Wirtanen|Birks|2016|p=320}} | |||

| * 575,000 medical<br /> casualties (including<br /> 385,000 wounded<br /> and 190,000 sick){{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|pp= 79, 269-271}}{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|p=172}} | |||

| * 64,000 ]{{sfn|Leskinen|Juutilainen|2005|p=1036}} | |||

| * 697 tanks{{sfn|Jowett|Snodgrass|2012|p=14}} | |||

| * 1,600 airplanes{{sfn|Nikunen|Talvitie|Keskinen|2011|p=349}} | |||

| * ''890,000–944,000<br /> total casualties'' | |||

| * <small>Not including civilian casualties,<br /> such as ]</small>}} | |||

| | notes = | |||

| | campaignbox = {{WWIITheatre}}{{Campaignbox Axis-Soviet War}}{{Campaignbox Scandinavia in World War II}}{{Campaignbox Finland 1941-1944}}{{Campaignbox Continuation War}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{FixBunching|mid}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Axis-Soviet War}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|mid}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Continuation War}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|mid}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Finland 1941-1944}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|end}} | |||

| The '''Continuation War''' ({{lang-fi|jatkosota}}, {{lang-sv|fortsättningskriget}}, {{lang-ru|''Война-продолжение''{{#tag:ref|This is a direct Russian translation of the Finnish name; Soviet ] has no name for the conflict, as it was considered simply a portion of the larger ]. Individual campaigns, such as those in Karelia, are described instead|group="Notes"}})}} (25 June 1941 – 19 September 1944) was the second of two wars fought between ] and the ] during ]. | |||

| At the time of the war, the name was used to make clear its perceived relationship to the preceding ]. | |||

| At the start of the war, the ] saw the war as an operation to conquer<ref name="Nordberg2003-3"> ], ''Arvio ja Ennuste Venäjän sotilaspolitiikasta Suomen suunnalla'' ("The Analysis and Prognosis of the Soviet Military Politics on the Finnish Front"), page 166. 2003. ISBN 9518843627</ref><ref name="Nordberg-2">{{fi icon}} Nordberg, Erkki, ''Arvio ja ennuste Venäjän sotilaspolitiikasta Suomen suunnalla'' ("The Analysis and Prognosis of the Soviet Military Politics on the Finnish Front"), page 181. 2003. ISBN 9518843627</ref><ref name="Jakobson1999-1"> ], ''Väkivallan vuodet, 20. vuosisadan tilinpäätös'' ("The Years of Violence, the Balance Sheet of the 21st Century"), page 316. 1999. ISBN 951-1-13369-1</ref><ref name="Jakobson1999-2"> ], ''Väkivallan vuodet, 20. vuosisadan tilinpäätös'' ("The Years of Violence, the Balance Sheet of the 21st Century"), page 353. 1999. ISBN 951-1-13369-1</ref><ref name="Hautamäki-1">{{swe icon}} ], ''Finland i stormens öga'' ("Finland in the Eye of a Storm"), 2004.</ref><ref name="Hautamäki-2">{{fi icon}} ], ''Suomi myrskyn silmässä'' ("Finland in the Eye of a Storm"), 2005.</ref><ref name="Manninen-1">{{fi icon}} ], ''Talvisodan salatut taustat'', pages 48-52. Helsinki: Kirjaneuvos, 1994. ISBN 951-90-5251-0</ref><ref name="Laurla-1">{{fi icon}} Bror Laurla, ''Talvisodasta jatkosotaan'' ("From the Winter War to the Continuation War", page 129. 1986.</ref><ref name="Mannerheim1952-3"> ], ''Muistelmat, osa II'' ("Memoirs, Part II"), page 298. 1952.</ref><ref name="Mannerheim1952-4"> ], ''Muistelmat, osa II'' ("Memoirs, Part II"), page 317. 1952.</ref><ref name="Metzger1984-1"> ], ''Kolmannen valtakunnan edustajana talvisodan Suomessa'' ("As a Representative of the Third Reich in Finland During the Winter War"), page 241. 1984.</ref><ref name="Krosby-1"> Krosby, Hans Peter, ''The Finnish Choice, 1941'' ("Suomen valinta, 1941"), page 78.</ref> Finland, according to a plan which got its final shape in May, 1941,<ref name="Manninen1994-1">{{fi icon}} Manninen, Ohto, ''Talvisodan salatut taustat'' ("The Hidden Backgrounds of the Winter War"), pages 48-52. Helsinki: Kirjaneuvos, 1994. ISBN 951-90-5251-0</ref><ref name="Koivisto2001-2">{{fi icon}} ], ''Venäjän idea'' ("The Idea of Russia"), page 260. 2001.</ref> one month before the Soviet war-opening attack. | |||

| During the ] period, while admitting<ref name="Jokipii-3">{{fi icon}} ], ''Jatkosodan synty'' ("The Launching of the Continuation War"), page 607. 1987.</ref> that it had started the war, the Soviet Union portrayed<ref name="Jokipii-3">{{fi icon}} ], ''Jatkosodan synty'' ("The Launching of the Continuation War"), page 607. 1987.</ref><ref name="Great Soviet Encyclopedia">], ''Finland'', Moscow, 1974. ISBN 0-02-880010-9</ref> the war as a part of its struggle against the ] and its allies, the ]. It has been referred to as the '''Soviet–Finnish War, 1941-1944''' ({{lang-ru|Советско-финская война, 1941-1944}}), or as a part of the overall operations of the ]. | |||

| ] saw its own operations in the region as a part of its overall war efforts of World War II. It took part by providing critical material support and military cooperation to Finland. | |||

| The ] declared war on Finland on 6 December 1941, followed by its ]s shortly afterwards. Thus, the Continuation War is a rare case of ], although the ] forces were not major participants in the war apart from the ]. | |||

| The ] did not fight or declare war against either party, but sent substantial ] to the Soviet Union for use in the war effort against Germany and its allies. | |||

| Hostilities between the Finnish and Soviet forces ended in September 1944, and the formal conclusion of the Continuation War was ratified by the ] of 1947. | |||

| ==Introduction== | |||

| <!-- WP:LEAD: "As a general rule of thumb, a lead section should contain no more than four well-composed paragraphs and be carefully sourced as appropriate"; | |||

| ] | |||

| WP:CITELEAD: "The necessity for citations in a lead should be determined on a case-by-case basis by editorial consensus"; and | |||

| WP:CREATELEAD: "While not usually required, we often include a few references with any controversial content in the lead to prevent edit wars. Controversial content often draws fire and demands for references, so we usually oblige." --> | |||

| <!-- Remember to be neutral per WP:NEUTRAL and add verifiable, reliable sources per WP:VERIFY! --> | |||

| The '''Continuation War''',{{refn|This name is translated as follows: {{langx|fi|jatkosota}}, {{langx|sv|fortsättningskriget}}, {{langx|de|Fortsetzungskrieg}}. The names '''Finnish Front of the Great Patriotic War'''. ({{langx|ru|Советско-финский фронт Великой Отечественной войны}}) and the '''Soviet–Finnish War 1941–1944''' ({{langx|ru|Советско–финская война 1941–1944|links=no}}) are often used in Russian ].<ref name="SovEncyclo">{{Cite book|title=Great Soviet Encyclopedia|publisher=MacMillan Publishing Company|year=1974|isbn=0-02-880010-9|chapter=Finland}}</ref> The U.S. ]' catalogue also lists the variants '''War of Retribution''' and '''War of Continuation''' (see authority control).|group="lower-alpha"}} also known as the '''Second Soviet–Finnish War''', was a conflict fought by ] and ] against the ] during ]. It began with a Finnish declaration of war on 25 June 1941 and ended on 19 September 1944 with the ]. The Soviet Union and Finland had previously fought the ] from 1939 to 1940, which ended with the Soviet failure to conquer Finland and the ]. Numerous reasons have been proposed for the Finnish decision to invade, with regaining territory lost during the Winter War regarded as the most common. Other justifications for the conflict include Finnish President ]'s vision of a ] and Commander-in-Chief ]'s desire to annex ]. | |||

| <!--> The following paragraph contains a bundle of cites for the Finnish participation in the siege of Leningrad, which is a commonly debated complex issue in the article (see talk).--> | |||

| On 22 June 1941, the ]. Three days later, the Soviet Union conducted an air raid on Finnish cities which prompted Finland to declare war and allow German troops in Finland to begin offensive warfare. By September 1941, Finland had regained its post–Winter War concessions to the Soviet Union in ]. The Finnish Army continued its offensive past the 1939 border during the ] and halted it only around {{Convert|30–32|km|mi|abbr=on}} from the centre of ]. It participated in ] by cutting the northern supply routes and by digging in until 1944. In ], ] to capture ] or cut the Kirov (Murmansk) Railway. The Soviet ] in June and August 1944 drove the Finns from most of the territories that they had gained during the war, but the Finnish Army halted the offensive in August 1944. | |||

| Finland adopted the concept of a "parallel war" whereby it sought to pursue its own objectives in concert with, but separate from, Nazi Germany. | |||

| Hostilities between Finland and the USSR ceased in September 1944 with the signing of the Moscow Armistice in which Finland restored its borders per the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty and additionally ceded ] and leased the ] to the Soviets. Furthermore, Finland was required to pay ], accept partial responsibility for the war, and acknowledge that it had been a German ally. Finland was also required by the agreement to expel German troops from Finnish territory, which led to the ] between Finland and Germany. | |||

| Major events of World War II, and the tides of war in general, had a significant impact on the course of the Continuation War: | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| * Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union (]) is closely connected to the Continuation War's beginning. | |||

| * The ] invasion of ] (]) was coordinated{{Citation needed|date=December 2007}} with the ] against Finland (9 June 1944 – 15 July 1944). | |||

| * The subsequent US/Soviet ] brought about the end of the Continuation War by rendering ] irrelevant. | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| === |

===Winter War=== | ||

| {{Main|Winter War|Interim Peace}} | |||

| ] in Helsinki on 13 March 1940 after the Moscow Peace Treaty became public]] | |||

| On 23 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the ] in which both parties agreed to divide the independent countries of Finland, ], ], ], ], and ] into ], with Finland falling within the Soviet sphere.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=30}} One week later, Germany ], leading to the United Kingdom and ] declaring war on Germany. The Soviet Union ] on 17 September.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=31}} The Soviet government turned its attention to the ] of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, demanding that they allow Soviet military bases to be established and troops stationed on their soil. The Baltic governments ] and signed agreements in September and October.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=33}} | |||

| Although ] has never been part of a modern Finnish state, a significant part of its inhabitants were Finnic-speaking Karelians. After the Finnish declaration of independence, voices arose advocating the annexation of East Karelia to "rescue it from oppression." This led to a few incursions to the area (] and ]), but these were unsuccessful. Finland unsuccessfully raised the question of East Karelia several times in the ]. | |||

| In October 1939, the Soviet Union attempted to negotiate with Finland to cede Finnish territory on the ] and the islands of the ], and to establish a Soviet military base near the Finnish capital of ].{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=39}} The ] refused, and the ] invaded Finland on 30 November 1939.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=44}} The same day, ], who was chairman of Finland's Defence Council at the time, assumed the position of ] of the ].{{sfn|Jägerskiöld|1986|pp=88, 111}} The USSR was expelled from the ] and was condemned by the international community for the illegal attack.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=49}} ] was promised, but very little actual help materialised, except from Sweden.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=65}} The ] concluded the 105-day Winter War on 13 March 1940 and started the ].{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=69}} By the terms of the treaty, Finland ceded 9% of its national territory and 13% of its economic capacity to the Soviet Union.{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=215}} Some 420,000 evacuees were resettled from the ceded territories.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=75}} Finland avoided total conquest of the country by the Soviet Union and retained its sovereignty.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=70}} | |||

| In non-leftist circles, ]'s role in the "]" government's victory over rebellious ]s during the ] was celebrated, although most preferred British or Scandinavian support over that of Germany. The security policy of an independent Finland turned first towards a ], whereby the newly independent nations of ], ], ], ], and Finland would form a defensive alliance against the USSR, but after negotiations collapsed, Finland turned to the ] for security. Contacts with the Scandinavian countries also met with little success. In 1932, Finland and the Soviet Union signed a ], but even contemporary analysts considered it worthless. | |||

| Prior to the war, Finnish foreign policy had been based on ] guarantees of support from the League of Nations and ], but this policy was considered a failure.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=74}} After the war, Finnish public opinion favored the reconquest of ]. The government declared national defence to be its first priority, and military expenditure rose to nearly half of public spending. Finland both received donations and purchased war materiel during and immediately after the Winter War.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=75}} Likewise, the Finnish leadership wanted to preserve the ] that was felt throughout the country during the Winter War. The divisive ] tradition of the ]'s 16 May victory-day celebration was therefore discontinued.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=76}} | |||

| The 1920 peace agreement was broken by the Soviet Union in 1937 when it stopped Finnish ships traveling between ] and the ] via the ]. The free use of this route for merchant vessels had been one of the articles in the agreement. | |||

| The Soviet Union had received the ], on Finland's southern coast near the capital Helsinki, where it deployed over 30,000 Soviet military personnel.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=75}} Relations between Finland and the Soviet Union remained strained after the signing of the one-sided peace treaty, and there were disputes regarding the implementation of the treaty. Finland sought security against further territorial depredations by the USSR and proposed ] with ] and ], but these initiatives were quashed by Moscow.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=77}}{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=216}} | |||

| ===Winter war=== | |||

| {{Main|Winter War}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] in 1939 enabled the Soviet Union to threaten to invade Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland without German interference. The three Baltic countries soon ] to Soviet demands, but Finland refused. As a result, on 30 November 1939, the Soviet Union attacked Finland. Condemnation by the League of Nations and by countries all over the world had no effect on Soviet policy. International help to Finland was planned, but very little actual help materialized. | |||

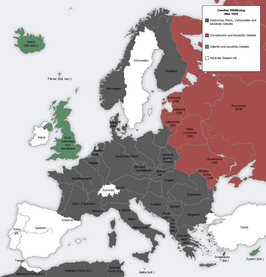

| ===German and Soviet expansion in Europe=== | |||

| The ], which was signed on 12 March 1940, ended the Winter War. The Treaty was severe for Finland. A fifth of the country's industry and 11% of agricultural land were lost, as was ], the country's second largest city. Some 12% of Finland's population had to be moved to its side of the border. ] was leased to the Soviet Union as a military base. However, Finland had avoided having the Soviet Union annex the whole country. | |||

| {{see also|Germany–Soviet Union relations before 1941}} | |||

| ] in ], pictured in 2017. During the Winter and Continuation Wars, ], as it was then known, was of strategic importance to both sides.]] | |||

| After the Winter War, Germany was viewed with distrust by the Finnish, as it was considered an ally of the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the Finnish government sought to restore diplomatic relations with Germany, but also continued its Western-orientated policy and negotiated a war trade agreement with the United Kingdom.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=77}} The agreement was renounced after the ] on 9 April 1940 resulted in the UK cutting all trade and traffic communications with the Nordic countries. With the ], a Western orientation was no longer considered a viable option in Finnish foreign policy.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=78}} On 15 and 16 June, the Soviet Union ] almost without any resistance and Soviet ] were installed. Within two months Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were incorporated into the USSR and by mid–1940, the two remaining northern democracies, Finland and Sweden, were encircled by the hostile states of Germany and the Soviet Union.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=79}} | |||

| On 23 June, shortly after the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states began, Soviet Foreign Minister ] contacted the Finnish government to demand that a mining licence be issued to the Soviet Union for the ] mines in ] or, alternatively, permission for the establishment of a joint Soviet-Finnish company to operate there. A licence to mine the deposit had already been granted to a British-Canadian company and so the demand was rejected by Finland. The following month, the Soviets demanded that Finland destroy the fortifications on the ] and to grant the Soviets the right to use Finnish railways to transport Soviet troops to the newly acquired Soviet base at Hanko. The Finns very reluctantly agreed to those demands.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=80}} On 24 July, Molotov accused the Finnish government of persecuting the communist ] and soon afterward publicly declared support for the group. The society organised demonstrations in Finland, some of which turned into riots.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=81}}{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=218}} | |||

| ==Interim peace== | |||

| {{Main|Interim Peace}} | |||

| Russian-language sources from the post-Soviet era, such as the study '']'', maintain that Soviet policies leading up to the Continuation War were best explained as defensive measures by offensive means. The Soviet division of occupied Poland with Germany, the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states and the Soviet invasion of Finland during the Winter War are described as elements in the Soviet construction of a security zone or buffer region from the perceived threat from the ] powers of Western Europe. Other post-Soviet Russian-language sources consider establishment of Soviet ]s in the ] countries and the ] as the culmination of the Soviet defence plan.<ref>{{harvnb|Baryshnikov|2002v}}: "The actual war with Finland began first of all due to unresolved issues in Leningrad's security from the north and Moscow's concerns for the perspective of Finland's politics. At the same time, a desire to claim better strategic positions in case of a war with Germany had surfaced within the Soviet leadership."</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://www.aroundspb.ru/finnish/kozlov/part_01.php|title=Финская война. Взгляд "с той стороны"|last=Kozlov|first=Alexander I.|year=1997 |language=ru|trans-title=The Finnish War: A look from the "other side"|quote=After the rise of National Socialism to power in Germany, the geopolitical importance of the former 'buffer states' had drastically changed. Both the Soviet Union and Germany vied for the inclusion of these states into their spheres of influence. Soviet politicians and military considered it likely, that in case of an aggression against the USSR, German Armed Forces will use the territory of the Baltic states and Finland as staging areas for invasion—by either conquering or coercing these countries. None of the states of the Baltic region, excluding Poland, had sufficient military power to resist a German invasion.|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071209182941/http://www.aroundspb.ru/finnish/kozlov/part_01.php|archive-date=9 December 2007}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Meltyukhov|2000}}: "The English–French influence in the Baltics, characteristic for the '20s and early '30s, was increasingly limited by the growth of German influence. Due to the strategic importance of the region, the Soviet leadership also aimed to increase its influence there, using both diplomatic means as well as active social propaganda. By the end of the '30s, the main contenders for influence in the Baltics were Germany and the Soviet Union. Being a buffer zone between Germany and the Soviet Union, the Baltic states were bound to them by a system of economic and non-aggression treaties of 1926, 1932 and 1939."</ref> Western historians, such as ] and ], dispute this view and describe pre-war Soviet policy as an attempt to stay out of the war and regain the land lost due to the ] after the fall of the ].{{sfn|Davies|2006|pp=137, 147}}{{sfn|Lukacs|2006|p=57}} | |||

| The ], in 1940, was a shock to the Finns. It was perceived as the ultimate failure of Finland's foreign policy, which had been based on ] guarantees for support. Binding ] were now sought and formerly frosty relations, such as with the Soviet Union and the ], had to be eased. Public opinion in Finland longed for the re-acquisition of ], and put its hope in the peace conference that was assumed would follow World War II. The term ''Välirauha'' ("Interim Peace") became popular after the harsh peace was announced. | |||

| ===Relations between Finland, Germany and Soviet Union=== | |||

| Although the peace treaty was signed, the ] and censorship was not revoked because of the widening world war, the difficult food supply situation, and the poor shape of the Finnish military. This made it possible for president ] to ask ] ] to remain ] and supervise rearmament and fortification work. During 1940, Finland received material purchased and donated during and immediately after the Winter War. Military expenditures rose in 1940 to 45% of Finland's state budget. A war trade treaty with Britain had little effect due to Germany's occupation of ] and ] on 9 April 1940 (]).<ref name="Seppinen">Seppinen, Ilkka, ''Suomen ulkomaankaupan ehdot, 1939-1944'', 1983. ISBN 951-9254-48-X</ref> These occupations left Finland and Sweden encircled by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. From May 1940, Finland pursued a campaign to reestablish good relations with Germany. Finnish media not only refrained from criticism of Nazi Germany, but also took an active part in this campaign. Dissent was censored. After the ], the campaign was stepped up. | |||

| {{Main|Operation Barbarossa}} | |||

| ] | |||

| On 31 July 1940, ] gave the order to plan an assault on the Soviet Union, meaning Germany had to reassess its position regarding both Finland and Romania. Until then, Germany had rejected Finnish requests to purchase arms, but with the prospect of an invasion of Russia, that policy was reversed, and in August, the secret sale of weapons to Finland was permitted.{{sfn|Reiter|2009|p=132|pp=}} Military authorities signed an agreement on 12 September, and an official exchange of diplomatic notes was sent on 22 September. Meanwhile, German troops were ] through Sweden and Finland.{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=220}} This change in policy meant Germany had effectively redrawn the border of the German and Soviet spheres of influence, in violation of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=83}} | |||

| On the other hand, the relations between Finland and the Soviet Union remained sour. The implementation of the Moscow Peace Treaty created a number of problems. The forced return of evacuated machinery, locomotives, and rail cars, disagreement on a number of issues created by the new border, such as fishing rights and the usage of the ], heightened the distrust. | |||

| In response to that new situation, Molotov visited Berlin on 12–13 November 1940.{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=219}} He requested for Germany to withdraw its troops from Finland and to stop enabling Finnish anti-Soviet sentiments. He also reminded the Germans of the 1939 pact. Hitler inquired how the Soviets planned to settle the "Finnish question" to which Molotov responded that it would mirror the events in ] and the Baltic states. Hitler rejected that course of action.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=84}} During the ] in December 1940, ] was elected to be president largely due to interference by Molotov in Ryti's favour since he had signed the Moscow Peace Treaty as prime minister.{{sfn|Virrankoski|2009|p=898}}{{sfn|Turtola|2000|p=409}} | |||

| Unbeknownst to Finland, ] had started to plan an invasion of the Soviet Union (]). He had not been interested in Finland before the Winter War, but now he saw its value as a base of operations, and perhaps also the military value of the ].{{Citation needed|date=December 2009}} In the first weeks of August, German concerns of a likely immediate Soviet attack on Finland caused Hitler to lift the arms embargo. Negotiations were initiated concerning German troop transfer rights in Finland in exchange for arms and other material. For the Third Reich, this was a breach of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, as well a breach of the Moscow Peace Treaty for Finland. Soviet negotiators had insisted that the troop transfer agreement (to Hanko) should not be published making it easy for the Finns to keep ] secret until the first German troops arrived. {{Citation needed|date=December 2009}} | |||

| On 18 December 1940, Hitler officially approved Operation Barbarossa, paving the way for the German invasion of the Soviet Union,{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=221}} in which he expected both Finland and Romania to participate.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=86}} Meanwhile, Finnish Major General ] met with German Colonel General ] and Reich Marshal ] in Berlin, the first time that the Germans had advised the Finnish government, in carefully-couched diplomatic terms, that they were preparing for war with the Soviet Union. Outlines of the actual plan were revealed in January 1941 and regular contact between Finnish and German military leaders began in February.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=86}} Additionally in January 1941, Moscow again demanded Finland relinquish control of the Petsamo mining area to the Soviets, but Finland, emboldened by a rebuilt defence force and German support, rejected the proposition.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=85}} | |||

| Despite the Soviet leadership having promised the Finns during the signing of the Moscow Peace treaty that it would not intervene in Finnish domestic policy,{{Citation needed|date=November 2007}} the reality of the interim peace period showed the opposite. After the ceasefire, the Soviets demanded the Finnish industrial town of ], which clearly was on the Finnish side of the peace treaty border;{{Citation needed|date=November 2007}} the Finns accepted and handed over the town. The Soviet involvement in Finnish domestic politics continued with open Soviet support for the extreme left wing organization SNS Friendship Union Soviet-Finland, which was campaigning for Finland to join the Soviet Union. The Soviets also successfully demanded that the Finnish minister ] resign and that, during the Finnish presidential election of 1940, neither Mannerheim, Kivimäki, Tanner nor Svinhufvud were to be candidates. On a meeting with Mannerheim in 1940, Hitler claimed, that the Soviet foreign minister Molotov had asked Hitler for a free hand to 'solve the Finnish question', during one of his visits to Berlin.<ref>{{fi icon}} </ref>{{Verify source|date=January 2009}} | |||

| In the late spring of 1941, the USSR made a number of goodwill gestures to prevent Finland from completely falling under German influence. Ambassador {{ill|Ivan Stepanovich Zotov|ru|Зотов, Иван Степанович}} was replaced with the more conciliatory and passive {{ill|Pavel Dmitrievich Orlov|ru|Орлов, Павел Дмитриевич}}. Furthermore, the Soviet government announced that it no longer opposed a ] between Finland and Sweden. Those conciliatory measures, however, did not have any effect on Finnish policy.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=87}} Finland wished to re-enter the war mainly because of the Soviet invasion of Finland during the Winter War, which the League of Nations and Nordic neutrality had failed to prevent due to lack of outside support.{{sfn|Lunde|2011|p=9}} Finland primarily aimed to reverse its territorial losses from the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty and, depending on the success of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, to possibly expand its borders, especially into ]. Some right-wing groups, such as the ], supported a ] ideology.{{sfn|Jokipii|1999|pp=145–146}} This ideology of a Greater Finland mostly composed of Soviet territories was augmented by anti-Russian sentiments.{{sfn|Kirby|2006|pp=201-202}} | |||

| Negotiations over ] ] mining rights had dragged on for six months when the Soviet Foreign Ministry announced in January 1941 that the negotiations had to be concluded quickly. On the same day, the Soviet Union interrupted its grain deliveries to Finland. Soviet ambassador Zotov was recalled home 18 January and Soviet radio broadcasts started attacking Finland. Germans in northern Norway reported on 1 February that the Soviet Union had collected 500 fishing ships in ], capable of transporting a division. Hitler ordered troops in Norway to occupy Petsamo (]) immediately if the Soviet Union started attacking Finland. | |||

| ===German and Finnish war plans=== | |||

| Finland offered half of the mine to Soviets and demanded a guarantee that no anti-government agitation would be done in the mines. This was not enough for Soviets and when Mannerheim declared that any additional concessions would endanger the defence of the country and threatened to resign if those were done, the Finnish side decided to let the negotiations lapse when there was no movement from the Soviet positions. | |||

| The details of the Finnish preparations for war are still somewhat opaque. Historian ] stated that "it has so far proven impossible to pinpoint the exact date on which Finland was taken into confidence about Operation Barbarossa" and that "neither the Finns nor the Germans were entirely candid with one another as to their national aims and methods. In any case, the step from contingency planning to actual operations, when it came, was little more than a formality".{{sfn|Trotter|1991|p=226}} | |||

| The inner circle of Finnish leadership, led by Ryti and Mannerheim, actively planned joint operations with Germany under a veil of ambiguous neutrality and without formal agreements after an alliance with Sweden had proved fruitless, according to a meta-analysis by Finnish historian {{ill|Olli-Pekka Vehviläinen|fi}}. He likewise refuted the so-called "driftwood theory" that Finland had been merely a piece of driftwood that was swept uncontrollably in the rapids of great power politics. Even then, most historians conclude that Finland had no realistic alternative to co-operating with Germany.{{Sfn|Zeiler|DuBois|2012|pp=208–221}} On 20 May, the Germans invited a number of Finnish officers to discuss the coordination of Operation Barbarossa. The participants met on 25–28 May in ] and Berlin and continued their meeting in Helsinki from 3 to 6 June. They agreed upon Finnish ] and a general division of operations.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=87}} They also agreed that the Finnish Army would start mobilisation on 15 June, but the Germans did not reveal the actual date of the assault. The Finnish decisions were made by the inner circle of political and military leaders, without the knowledge of the rest of the government. Due to tensions between Germany and the Soviet Union, the government was not informed until 9 June that mobilisation of ]s would be required.{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=221}}{{sfn|Reiter|2009|pp=135–136, 138}} | |||

| After the failure of the nickel negotiations, diplomatic activities were halted for a few months. | |||

| ===Finland's relationship with Germany=== | |||

| ===Path to war=== | |||

| Finland never signed the ]. The Finnish leadership stated they would fight against the Soviets only to the extent needed to redress the balance of the 1940 treaty, though some historians consider that it had wider territorial goals under the slogan "shorter borders, longer peace" ({{langx|fi|"lyhyet rajat, pitkä rauha"|links=no}}). During the war, the Finnish leadership generally referred to the Germans as "brothers-in-arms" but also denied that they were allies of Germany – instead claiming to be "co-belligerents".{{sfn|Stahel|2018|p=8}} For Hitler, the distinction was irrelevant since he saw Finland as an ally.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=102}} The 1947 Paris Peace Treaty signed by Finland described Finland as having been "an ally of Hitlerite Germany" during the Continuation War.{{sfn|U.S. GPO|1947|p=229}}{{sfn|Tallgren|2014|p=512}} In a 2008 poll of 28 Finnish historians carried out by '']'', 16 said that Finland had been an ally of Nazi Germany, six said it had not been and six did not take a position.<ref name="Mäkinen1">{{cite news |last1=Mäkinen |first1=Esa |title=Historian professorit hautaavat pitkät kiistat |url=https://www.hs.fi/kulttuuri/art-2000004606365.html |access-date=7 February 2021 |work=Helsingin Sanomat |date=19 October 2008 |archive-date=23 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210523233020/https://www.hs.fi/kulttuuri/art-2000004606365.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{Cleanup|date=November 2009}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; width:35%; font-size:90%" | |||

| |+The Finnish-German relations during the Interim Peace 1940–1941<ref name="pikkujattilainen-haikio">{{cite book |last=Häikiö | first=Martti |editor1-first=Jari |editor1-last=Leskinen |editor2-first=Antti |editor2-last=Juutilainen |title=Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen |edition=1st |publisher=Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö |date=2005 |pages=13–25 |chapter=Jatkosodan ulkopolitiikka: Ennen sotaa 1940–1941 |language=Finnish |isbn=951-0-28690-7}}</ref> | |||

| !Month | |||

| !Year | |||

| !Event | |||

| |- | |||

| |August | |||

| |rowspan=3|1940 | |||

| |The Transit Agreement and licence the purchase of arms. | |||

| |- | |||

| |November | |||

| |Hitler rejects the request of Molotov to give "free hands" against Finland. | |||

| |- | |||

| |December | |||

| |Germany decides Operation Barbarossa. | |||

| |- | |||

| |February | |||

| |rowspan=4|1941 | |||

| |Finland starts co-operation with Germany. | |||

| |- | |||

| |May | |||

| |Detailed military plans between Finns and Germans. | |||

| |- | |||

| |June | |||

| |Germany attacks against the Soviet Union | |||

| |- | |||

| |July | |||

| |Finland attacks against the Soviet Union - following a defensive phase of 15 days, after Soviet attack against Finland. | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| The period did, however, see an increased German interest in Finland. One sign of the interest was the recruitment of one battalion of Finnish volunteers to the German ], with approval of the Finnish government. It has been concluded{{Who|date=January 2009}} that the battalion served as a token of Finnish commitment to cooperation with Nazi Germany. The agreement was that the Finnish volunteers would not be sent to fight against British or Greek forces (the only European nations at war with Germany at the moment of signing) and would serve for two years. This battalion, named the '']'' fought as part of ] in ] and the ]. When the two years were up, the battalion was pulled back from the front in May 1943 and was transported to ] and further to Hanko, where it was disbanded on 11 July. The soldiers were then dispersed into different units of the Finnish army. | |||

| ==Order of battle and operational planning== | |||

| The German Foreign Ministry sent ] to Finland on 5 May, this time to clarify that war between Germany and the Soviet Union would not be launched before spring 1942. Finnish leadership forwarded the message to the Swedes and the British. When the war broke out only a couple of months later, both the Swedish and British governments felt that the Finns had lied to them. | |||

| ===Soviet=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] ({{langx|ru|Северный фронт|links=no}}) of the ] was commanded by Lieutenant General ] and numbered around 450,000 soldiers in 18 divisions and 40 independent battalions in the Finnish region.{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|pp= 79, 269-271}} During the Interim Peace, the Soviet Military had relaid operational plans to conquer Finland,{{sfn|Suvorov|2013|p=133}} but with the German attack, Operation Barbarossa, begun on 22 June 1941, the Soviets required its best units and latest materiel to be deployed against the Germans and so abandoned plans for a renewed offensive against Finland.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=91}}{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|pp=153–154}} The ] was deployed in the Karelian Isthmus, the ] to Ladoga Karelia and the ] to the ]–] area of Lapland. The Northern Front also commanded eight ].{{sfn|Kirchubel|2013|pp=114–115}} As the initial German strike against the ] had not affected air units located near Finland, the Soviets could deploy around 700 aircraft supported by a number of ] wings.{{sfn|Jokipii|1999|p=301}} The ], which outnumbered the ] ({{lang|de|Kriegsmarine}}), comprised 2 battleships, 2 light cruisers, 47 destroyers or large torpedo boats, 75 submarines, over 200 smaller crafts, and 682 aircraft (of which 595 were operational).{{sfn|Kirchubel|2013|p=151}}{{sfn|Kovalevsky|2009|pp=3-8}} | |||

| {{Quote|It may be well by May Finland had no real alternative but to go along with Germany; German troops not only surrounded her northern frontier but were inside the country by virtue of the transit agreement; and furthermore Finland had become economically dependent on Germany. Evidence suggests, however that Finland by no means was an unwilling partner, that the inner circle of leaders banked on a German victory and were willing to follow the path dictated by Hitler, and did not consider any alternative policy.|''Finland in the Twentieth Century''|<ref name="Kirby, p.134"/>}} | |||

| ===Finnish and German=== | |||

| In the spring of 1941, joint military plans were discussed with Germany. In May 1941, the Finns learned that the Germans were planning hostilities against the Soviet Union.<ref name="Kirby A, p.221">], p.221</ref> Between 3 and 6 June, details of military co-operation were discussed in Helsinki as were issues regarding communications and securing sea lanes. It was also agreed that the Finnish Army would start mobilization on 15 June.<ref name="Kirby A, p.221"/> | |||

| {{Main||Finnish Army|German Army (1935–1945)}} | |||

| The Finnish Army ({{langx|fi|Maavoimat|links=no}}) mobilised between 475,000 and 500,000 soldiers in 14 divisions and 3 brigades for the invasion, commanded by Field Marshal ({{Lang|fi|sotamarsalkka}}) Mannerheim. The army was organised as follows:{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|pp=153–154}}{{sfn|Kirchubel|2013|pp=120–121}}{{sfn|Ziemke|2002|p=9}} | |||

| Finland made significant requests for material aid. Finland was willing to join Germany against Soviet Union with some prerequisites: a guarantee of Finnish independence, the pre-Winter War borders (or better), continuing grain deliveries, and that Finnish troops would not cross the border before a Soviet incursion. Prior to the war, the Germans offered Mannerheim command over the German troops in Finland, around 80,000 men. Mannerheim declined, because if he accepted, he and Finland would be tied to the German war aims.<ref>Max Jacobsson, ''Century of Violence'', 1999</ref> However, the Finnish political and military leaders were not unwilling to enter into a 'war of compensation' as co-belligerents of Nazi Germany<ref name="Kirby, p.135">], p.135</ref> The Barbarossa plan envisaged a subordinate military role for Finland, and the Germans certainly assumed that Finland would play that role when the time came.<ref name="Kirby, p.135"/> The Finnish leadership hoped that Finland would acquire a sizable share of the northern territory of a defeated Soviet Union.<ref name="Kirby, p.135"/> | |||

| * ] and ]: deployed to the Karelian Isthmus and comprised seven infantry divisions and one brigade. | |||

| * ]: deployed north of Lake Ladoga and commanded by General ]. It comprised the ], ], and Group Oinonen; a total of seven divisions, including the German 163rd Infantry Division, and three brigades. | |||

| * 14th Division: deployed in the ] region, commanded directly by ] ({{Lang|fi|Päämaja}}). | |||

| Although initially deployed for a static defence, the Finnish Army was to later launch an attack to the south, on both sides of Lake Ladoga, putting pressure on Leningrad and thus supporting the advance of the German ] through the Baltic states towards Leningrad.{{sfn|Ziemke|2002|p=9}} Finnish intelligence had overestimated the strength of the Red Army, when in fact it was numerically inferior to Finnish forces at various points along the border.{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|pp=153–154}} The army, especially its artillery, was stronger than it had been during the Winter War but included only one armoured battalion and had a general lack of motorised transportation;{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=90}} the army possessed 1,829 artillery pieces at the beginning of the invasion.<ref>{{harvnb|Baryshnikov|2002}}: "A special role was assigned by the Finnish command to artillery, which consisted of 1,829 guns."</ref> The ] ({{Lang|fi|Ilmavoimat}}) had received large donations from Germany prior to the Continuation War including ]s, ]s, ] flying boats, ] bombers, and ] trainers; in total the Finnish Air Force had 550 aircraft by June 1941, approximately half being combat.{{sfn|Corum|2004|p=14}}<ref>{{cite web |title=History of the Finnish Air Force |url=https://ilmavoimat.fi/en/history |website=Ilmavoimat |access-date=23 July 2023 |quote=The Air Force had a total strength of 550 aircraft.}}</ref> By September 1944, despite considerable German supply of aircraft, the Finns only had 384 planes. Even with the increase in supplied aircraft, the air force was constantly outnumbered by the Soviets.{{Sfn|Kinnunen|Kivimäki|2011|p=168}}{{Sfn|Nenye|Munter|Wirtanen|Birks|2016|p=339}} | |||

| The ], which had no knowledge of the negotiations,<ref name="Kirby A, p.221"/> was informed of this for the first time on 9 June, when the first mobilization orders were issued for troops needed to safeguard the forthcoming general mobilization phases. On 20 June, the Finns ordered the evacuation of 45,000 civilians from the Soviet border region. On 21 June, Finland's Chief of the General Staff, ], was finally informed by the Germans that the attack was to begin. | |||

| ] bomber-aircraft belonging to the Finnish Air Force in March 1944.|261x261px]] | |||

| The Finnish army was much larger and better equipped for war than it had been in 1939.<ref name="Kirby, p.134">], p.134</ref> When fully mobilized, it was 400,000 strong.<ref name="Kirby, p.134"/> | |||

| The ], or {{Lang|de|AOK Norwegen}}, comprising four divisions totaling 67,000 German soldiers, held the arctic front, which stretched approximately {{convert|500|km|mi|abbr=on}} through Finnish Lapland. This army would also be tasked with striking Murmansk and the ] during ]. The Army of Norway was under the direct command of the ] ({{lang|de|OKH}}) and was organised into ] and ] with the ] and 14th Division attached to it.{{sfn|Kirchubel|2013|p=120-121}}{{sfn|Ziemke|2002|p=9}}{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=90}} The ] ({{lang|de|OKL}}) assigned 60 aircraft from '']'' (Air Fleet 5) to provide air support to the Army of Norway and the Finnish Army, in addition to its main responsibility of defending Norwegian air space.{{sfn|Ziemke|2002|p=10}}{{sfn|Ziemke|2015|pp=149–151}} In contrast to the front in Finland, a total of 149 divisions and 3,050,000 soldiers were deployed for the rest of Operation Barbarossa.{{sfn|Ziemke|2002|pp=7, 9}} | |||

| ==Course== | |||

| === Initial stages === | |||

| ] shown in light colour]] | |||

| ==Finnish offensive phase in 1941== | |||

| The arrival of German troops for the attack of the Soviet Union begun 7th of June 1941 when ] situated in Norway crossed the border to Finland along Nyrud bridge. The motorized force of 8,000–9,000 men marched to municipal town of ], where they arrived 10th of June. At the same time two divisions of German forces was been shipped from Southern Norway to Finnish harbor of Oulu, 20,000 men of 169th Division from Stettin and 10,600 men from ]. The troops were transported to Rovaniemi by trains. Nearby Rovaniemi there were 14th June 40,600 men of German forces. The troops started to advance East to ] on 18th of June. The headquarter of German army in Norway moved to Rovaniemi on June 11th. On 17th first Luftwaffe planes landed in Rovaniemi, 16th in ] air field, and 21st in ]. | |||

| ===Initial operations=== | |||

| ] in 1941.|254x254px]] | |||

| In the evening of 21 June 1941, German mine-layers hiding in the ] deployed two large minefields across the Gulf of Finland. Later that night, German bombers flew along the gulf to Leningrad, mining the harbour and the river ], making a refueling stop at ], Finland, on the return leg. In the early hours of 22 June, Finnish forces launched ] ("Regatta"), deploying troops in the demilitarised Åland Islands. Although the 1921 ] had clauses allowing Finland to defend the islands in the event of an attack, the coordination of this operation with the German invasion and the arrest of the Soviet consulate staff stationed on the islands meant that the deployment was a deliberate violation of the treaty, according to Finnish historian ].{{sfn|Jokipii|1999|p=282}} | |||

| On the morning of 22 June, Hitler's proclamation read: "Together with their Finnish comrades in arms the ] stand at the edge of the Arctic Ocean. German troops under command of the ], and the Finnish freedom fighters under their Marshal's command, are protecting Finnish territory."{{sfn|Mann|Jörgensen|2016|p=74}} | |||

| ] had already commenced in the northern Baltic by the late hours of 21 June, 1941, when German minelayers, which had been hiding in the Finnish archipelago, laid two large minefields across the ].<ref name="Nordberg">{{fi icon}} Nordberg, Erkki, ''Arvio ja ennuste Venäjän sotilaspolitiikasta Suomen suunnalla'', 2003. ISBN 9518843627</ref><ref name="Encyclopædia Britannica"> , Encyclopædia Britannica Premium, 2006.</ref> These minefields ultimately proved sufficient to confine the Soviet ] to the easternmost part of the Gulf of Finland. Later the same night, German bombers flew along the Gulf of Finland to ] and mined the harbor and the river ]. On the return trip, these bombers landed for refueling on an airfield in ]. Finland was concerned that the Soviet Union would occupy ], so ] ("Regatta") was launched in the early hours of 22 June to occupy Åland for Finland instead. Soviet bombers launched attacks against Finnish ships during the operation, but no damage was inflicted. Finnish submarines also laid six small minefields at 8:00–10:00 between ] and the Estonian coast according to pre-war defensive plans of Finland and Estonia.{{Citation needed|date=February 2007}} | |||

| Following the launch of ] at around 3:15 a.m. on 22 June 1941, the Soviet Union sent seven bombers on a retaliatory airstrike into Finland, hitting targets at 6:06 a.m. Helsinki time as reported by the ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://digi.narc.fi/digi/view.ka?kuid=3615109|title=Scan from the coastal defence ship Väinämöinen's log book|date=22 June 1941|website=Digital Archive of the National Archives of Finland|access-date=21 February 2018|archive-date=6 November 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181106180526/http://digi.narc.fi/digi/view.ka?kuid=3615109|url-status=live}}</ref> On the morning of 25 June, the Soviet Union launched another air offensive, with 460 fighters and bombers targeting 19 airfields in Finland; however, inaccurate intelligence and poor bombing accuracy resulted in several raids hitting Finnish cities, or municipalities, causing considerable damage. 23 Soviet bombers were lost in this strike while the Finnish forces lost no aircraft.<ref>{{cite book|title=Kohtalokkaat lennot 1939–1944|last1=Hyvönen|first1=Jaakko|publisher=Apali Oy|year=2001|isbn=952-5026-21-3|language=fi|trans-title=Fateful Flights 1939–1944}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://militera.lib.ru/h/hazanov_db2/07.html|title=1941. Горькие уроки: Война в воздухе|last=Khazanov|first=Dmitriy B.|publisher=Yauea|year=2006|isbn=5-699-17846-5|language=ru|trans-title=1941: The War in the Air - The Bitter Lessons|chapter=Первая воздушная операция советских ВВС в Великой Отечественной войне|trans-chapter=The first air operation of the Soviet Air Force in the Great Patriotic War|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111127153212/http://militera.lib.ru/h/hazanov_db2/07.html|archive-date=27 November 2011}}</ref>{{sfn|Reiter|2009|pp=135–136, 138}} Although the USSR claimed that the airstrikes were directed against German targets, particularly airfields in Finland,<ref name="Platonov">{{cite book|title=Битва за Ленинград|location=Moscow|publisher=Voenizdat Ministerstva oborony SSSR|year=1964|editor-last=Platonov|editor-first=Semen P. |trans-title=The Battle for Leningrad}}</ref> the ] used the attacks as justification for the approval of a "defensive war".{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=88}} According to historian David Kirby, the message was intended more for public opinion in Finland than abroad, where the country was viewed as an ally of the Axis powers.{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=222}}{{Sfn|Zeiler|DuBois|2012|pp=208–221}} | |||

| On 21 June, mobilized Finnish units began to concentrate at the Finnish-Soviet border, where they were arranged into defensive formations. Finland mobilized 16 infantry divisions, one cavalry brigade, and two "]" brigades, which were standard infantry brigades, except for one battalion in the 1st ] (1.JPr), which was armored using captured Soviet equipment. There were also a handful of separate battalions, mostly formed from border guard units and used mainly for reconnaissance. Soviet military plans estimated that Finland would be able to mobilize only 10 infantry divisions, as it had done in the Winter War, but they failed to take into account the material Finland had purchased between the wars and its training of all available men. German forces were also present in northern Finland: two mountain divisions at ] and two infantry divisions at ]. On 22 June, another German infantry division moved in from Oslo through Sweden towards ], although one reinforced regiment was later redirected to Salla. | |||

| ===Finnish advance in Karelia=== | |||

| On the morning of 22 June, the German ] started ] and began its move from northern Norway to ]. Finland did not allow direct German attacks from its soil to the Soviet Union, so German forces in Petsamo and Salla were ordered to hold their fire. There was occasional individual and group level exchange of small arms fire between Soviet and Finnish border guards, but otherwise the front was quiet. | |||

| {{Main|Finnish invasion of Ladoga Karelia|Finnish invasion of the Karelian Isthmus|Finnish invasion of East Karelia (1941){{!}}Finnish invasion of East Karelia}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The Finnish plans for the offensive in Ladoga Karelia were finalised on 28 June 1941,{{sfn|Lunde|2011|pp=154–159}} and the first stages of the operation began on 10 July.{{sfn|Lunde|2011|pp=154–159}}{{sfn|Dzeniskevich|Kovalchuk|Sobolev|Tsamutali|1970|p=19}}{{sfn|Reiter|2009|pp=135–136, 138}} By 16 July, the ] had reached the northern shore of ], dividing the Soviet 7th Army, which had been tasked with defending the area.{{sfn|Lunde|2011|pp=154–159}} The USSR struggled to contain the German assault, and soon the Soviet high command, '']'' ({{langx|ru|Ставка|links=no}}), pulled all available units stationed along the Finnish border into the beleaguered front line.{{sfn|Lunde|2011|pp=154–159}} Additional reinforcements were drawn from the ] and the Soviet ], excluding the {{ill|198th Motorised Division|ru|198-я моторизованная дивизия}}, both of which were stationed in Ladoga Karelia, but this stripped much of the reserve strength of the Soviet units defending that area.{{sfn|Raunio|Kilin|2007|pp=34, 62}} | |||

| Mobilization on the Soviet side of the border had been underway since 18 June. The ] was covered by the ], which consisted of the ], the ] and the ], together with five infantry, one motorized and two armored divisions. Ladoga Karelia was defended by the ] consisting of four infantry divisions. In the ]–] region, the Soviet Union had the ] with ], consisting of five infantry divisions (one as reserve in ]) and one armored division. The Red Army also had around 40 battalions of separate regiments and fortification units in the region, which were not part of its divisional structure. Leningrad was garrisoned by three infantry divisions and one mechanized corps. | |||

| The Finnish ] started its offensive in the north of the Karelian Isthmus on 31 July.{{sfn|Lunde|2011|pp=167–172}} Other Finnish forces reached the shores of Lake Ladoga on 9 August, encircling most of the three defending Soviet divisions on the northwestern coast of the lake in a ] ({{langx|fi|motti|links=no}}); these divisions were later evacuated across the lake. On 22 August, the Finnish ] began its offensive south of II Corps and advanced towards ] ({{Langx|fi|Viipuri|links=no}}).{{sfn|Lunde|2011|pp=167–172}} By 23 August, II Corps had reached the ] to the east and encircled the Soviet forces defending Vyborg.{{sfn|Lunde|2011|pp=167–172}} Finnish forces captured Vyborg on 29 August.{{sfn|Enkenberg|2021|p=70}} | |||

| ===1941=== | |||

| ====Offensives==== | |||

| =====Soviet Union===== | |||

| The initial devastating German strike against the Soviet Air Force had not affected air units located near Finland, so the Soviets could field nearly 750 planes as well as a part of the 700 planes of the ] against 300 Finnish planes. In the morning of 25 June, the Soviet Union launched a major air offensive against 18 Finnish cities with 460 planes<ref name="Jokipii">], ''Jatkosodan synty'', 1987. ISBN 951-1-08799-1</ref>. | |||

| ] in Viipuri (now Vyborg, Russia) on 31 August 1941, celebrating its recapture.|283x283px]] | |||

| The Soviet Union claimed the attack was directed against German targets, especially airfields, in Finland;<ref name="Platonov">{{cite book |author=Platonov, S.P. (editor) |year=1964 |title=Битва за Ленинград |publisher=Voenizdat Ministerstva oborony SSSR}}</ref> however, the British embassy verified that only Finnish targets, mainly civilian ones, were hit in southern and middle Finland, where the embassy had many informants. The attack failed to hit any German targets. At the same time, Soviet artillery stationed in the Hanko base began to shell Finnish targets, and a minor Soviet infantry attack was launched over the Finnish side of the border in ]. | |||

| The Soviet order to withdraw from Vyborg came too late, resulting in significant losses in materiel, although most of the troops were later evacuated via the ].{{sfn|Salisbury|1969|p=247}} After suffering severe losses, the Soviet 23rd Army was unable to halt the offensive, and by 2 September the Finnish Army had reached the old ].{{sfn|Glantz|2002|p=68-69}}{{sfn|Salisbury|1969|pp=243-245}} The advance by Finnish and German forces split the Soviet Northern Front into the ] and the ] on 23 August.{{sfn|Glantz|2005|p=50}} On 31 August, Finnish Headquarters ordered II and IV Corps, which had advanced the furthest, to halt their advance along a line that ran from the Gulf of Finland via ]–]–]–] to Lake Ladoga.{{sfn|Werth|1999|pp=360–361}}{{sfn|Salisbury|1969|pp=245-246}} <!-- Remember to be neutral per WP:NEUTRAL and add verifiable, reliable sources per WP:VERIFY! -->The line ran past the former 1939 border, and approximately {{Convert|30-32|km|mi|abbr=on}} from Leningrad;{{sfn|Glantz|2002|p=69}}{{sfn|Salisbury|1969|p=246|ps=: "This line was only twenty miles from the Leningrad city limits."}} a defensive position was established along this line.{{sfn|Jones|2009|p=142|ps=: "Finland advanced to within twenty miles of Leningrad's outskirts, cutting the city's northern supply routes, but its troops then halted at its 1939 border, and did not undertake further action."}}{{sfn|Glantz|2002|p=416}} On 30 August, the IV Corps fought the Soviet 23rd Army in the ] and defeated them on 1 September.{{sfn|Nenye|Munter|Wirtanen|Birks|2016|pp=101-104}} Sporadic fighting continued around Beloostrov until the Soviets evicted the Finns on 5 September.{{sfn|Werth|1999|pp=360–361}} The front on the Isthmus stabilised and the ] began on 8 September.{{sfn|Brinkley|2004|p=210}}{{sfn|Glantz|2002|p=69}} | |||

| A meeting of the Finnish parliament was scheduled for 25 June, where Prime Minister ] had intended to present a notice about Finland's neutrality in the Soviet-German war, but the Soviet bombings led him to observe instead, that Finland was once again at war with the Soviet Union. The Continuation War had begun. | |||

| The Finnish Army of Karelia started its attack in East Karelia towards ], ] and the ] on 9 September. German Army Group North advanced from the south of Leningrad towards the Svir River and captured ] but were forced to retreat to the ] by Soviet counterattacks. Soviet forces repeatedly attempted to expel the Finns from their ] south of the Svir during October and December but were repulsed; Soviet units attacked the German ] in October 1941, which was operating under Finnish command across the Svir, but failed to dislodge it.{{sfn|Raunio|Kilin|2008|pp=10–11}} Despite these failed attacks, the Finnish attack in East Karelia had been blunted and their advance had halted by 6 December. During the five-month campaign, the Finns suffered 75,000 casualties, of whom 26,355 had died, while the Soviets had 230,000 casualties, of whom 50,000 became prisoners of war.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=96}} | |||

| The war against Germany did not go as well as pre-war Soviet war games had envisioned, and soon the ] had to call all available units to the rapidly deteriorating front line. Because of this, the initial air offensive against Finland could not be followed by a supporting land offensive, in the scale originally planned.<ref name="Manninen2008-1">], ''Miten Suomi valloitetaan: Puna-armeijan operaatiosuunnitelmat 1939-1944''. Helsinki: Edita, 2008. ISBN 978-951-37-5278-1</ref> Moreover, the 10th Mechanized Corps with two armored divisions and ] were withdrawn from Ladoga Karelia, thus stripping reserves from defending units. | |||

| ===Operation Silver Fox in Lapland and Lend-Lease to Murmansk=== | |||

| =====Finland===== | |||

| ] soldier Rájá-Jovnna<ref name="yle-11335441">{{cite news |last=Rasmus |first=Linnea |date=5 May 2020 |title=Ohcejohkalaš Rájá-Jovnna šattai Ruošša vuoitobeaivvi modeallan – Bárdni: "Hervii gal, gádden giinu leaikkastallá" |url=https://yle.fi/a/3-11335441 |work=Yle Sápmi |access-date=31 March 2023 |language=se |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330213135/https://yle.fi/a/3-11335441 |url-status=live }}</ref> with a ] in Lapland. Reindeer were used in many capacities, such as pulling supply sleighs in snowy conditions.]] | |||

| {{Main|Operation Silver Fox|Lend-Lease}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=November 2009}} | |||

| The German objective in Finnish Lapland was to take Murmansk and cut the Kirov (Murmansk) Railway running from Murmansk to Leningrad by capturing Salla and ]. Murmansk was the only year-round ] in the north and a threat to the nickel mine at Petsamo. The joint Finnish–German Operation Silver Fox ({{langx|de|Unternehmen Silberfuchs}}; {{langx|fi|operaatio Hopeakettu|links=no}}) was started on 29 June 1941 by the German Army of Norway, which had the ] and ] under its command, against the defending Soviet 14th Army and ]. By November, the operation had stalled {{convert|30|km|mi|abbr=on}} from the Kirov Railway due to unacclimatised German troops, heavy Soviet resistance, poor terrain, arctic weather and diplomatic pressure by the United States on the Finns regarding the lend-lease deliveries to Murmansk. The offensive and its three sub-operations failed to achieve their objectives. Both sides dug in and the arctic theatre remained stable, excluding minor skirmishes, until the Soviet ] in October 1944.{{sfn|Mann|Jörgensen|2016|pp=81–97, 199–200}}{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=95}} | |||

| ======Reconquest of Ladoga Karelia====== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Finnish reconquest of Ladoga Karelia (1941)}} | |||

| The crucial ] from the US and the UK via Murmansk and Kirov Railway to the bulk of the Soviet forces continued throughout World War II. The US supplied almost ]11 billion in materials: 400,000 jeeps and trucks; 12,000 armored vehicles (including 7,000 tanks, which could equip some 20 US armoured divisions); 11,400 aircraft; and {{convert|1.75|e6ST|e6t|abbr=unit|order=flip}} of food.{{sfn|Weeks|2004|p=9}}{{sfn|Stewart|2010|p=158}} As a similar example, British shipments of Matilda, Valentine and Tetrarch tanks accounted for only 6% of total Soviet tank production, but over 25% of medium and heavy tanks produced for the Red Army.{{sfn|Suprun|1997|p=35}} | |||

| ======Reconquest of the Karelian Isthmus====== | |||

| {{Main|Finnish reconquest of the Karelian Isthmus (1941)}} | |||

| ===Aspirations, war effort and international relations=== | |||

| ======Conquest of East Karelia====== | |||

| {{see also|Greater Finland#The Continuation War{{!}}Greater Finland}} | |||

| {{Main|Finnish conquest of East Karelia (1941)}} | |||

| ]) at ] on 12 July 1941, two days after the invasion started.]] | |||

| The ''Wehrmacht'' rapidly advanced deep into Soviet territory early in the Operation Barbarossa campaign, leading the Finnish government to believe that Germany would defeat the Soviet Union quickly.{{sfn|Reiter|2009|pp=135–136, 138}} President Ryti envisioned a Greater Finland, where Finns and other ] would live inside a "natural defence borderline" by incorporating the ], East Karelia and perhaps even northern ]. In public, the proposed frontier was introduced with the slogan "short border, long peace".{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=92}}{{sfn|Reiter|2009|pp=135–136, 138}}{{Sfn|Zeiler|DuBois|2012|pp=208–221}} Some members of the Finnish Parliament, such as members of the ] and the ], opposed the idea, arguing that maintaining the 1939 frontier would be enough.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=92}} Mannerheim often called the war an anti-Communist crusade, hoping to defeat "] once and for all".{{sfn|Reiter|2009|pp=135–136, 138}} On 10 July, Mannerheim drafted his order of the day, the ], in which he pledged to liberate Karelia; in December 1941 in private letters, he made known his doubts of the need to push beyond the previous borders.{{sfn|Clements|2012|p=210}} The Finnish government assured the United States that it was unaware of the order.{{sfn|Kirby|2006|p=224}} | |||

| ======Advance from Northern Finland====== | |||

| {{See|Operation Silver Fox}} | |||

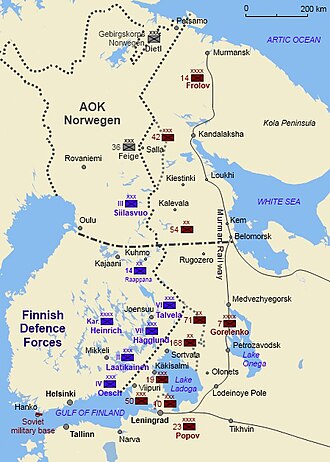

| The operational border between Finnish and German forces was located southeast from Lake Oulujärvi to the border, and then straight to the east. The Finnish 14.D controlled the southern part of the border, while the northern part was in the responsibility of ] (Col. Gen. von Falkenhorst). The Finnish III Corps (Maj. Gen. Siilasvuo) was southernmost, German XXXVI Corps (Gen. Feige) next and German Mountain Corps (Gen. Dietl) northernmost at Petsamo. Together, they had three infantry, two mountain and one SS ("Nord") divisions and two armored battalions. Additionally, an infantry regiment and an artillery battalion from the German 163rd division were diverted there. Opposing them were the Soviet 14th Army (Lt. Gen. Frolov) at Murmansk, part of the 7th infantry division, together with the 6th infantry division, one armored division, and another division strengthening the fortified area. | |||

| According to Vehviläinen, most Finns thought that the scope of the new offensive was only to regain what had been taken in the Winter War. He further stated that the term 'Continuation War' was created at the start of the conflict by the Finnish government to justify the invasion to the population as a continuation of the defensive Winter War. The government also wished to emphasise that it was not an official ally of Germany, but a 'co-belligerent' fighting against a common enemy and with purely Finnish aims. Vehviläinen wrote that the authenticity of the government's claim changed when the Finnish Army crossed the old frontier of 1939 and began to annex Soviet territory.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|pp=89–91}} British author ] asserted that by December 1941, Finnish soldiers had started questioning whether they were fighting a war of national defence or foreign conquest.{{sfn|Clements|2012|pp=210–211}} | |||

| As the Finns had not allowed the Germans to attack across the Finnish border before 25 June, Soviet side had ample warning and used the available days to fortify the border region. Also, the concentration of the German forces to the border took longer than anticipated, so the start of the offensive was delayed until 29 June, a week later than the start of Operation Barbarossa, thus giving the Soviets more time to prepare their fortifications. | |||

| By the autumn of 1941, the Finnish military leadership started to doubt Germany's capability to finish the war quickly. The Finnish Defence Forces suffered relatively severe losses during their advance and, overall, German victory became uncertain as German troops were ]. German troops in northern Finland faced circumstances they were unprepared for and failed to reach their targets. As the front lines stabilised, Finland attempted to start peace negotiations with the USSR.{{sfn|Jutikkala|Pirinen|1988|p=248}} Mannerheim refused to assault Leningrad, which would inextricably tie Finland to Germany; he regarded his objectives for the war to be achieved, a decision that angered the Germans.{{sfn|Clements|2012|p=210}} | |||

| The Mountain Corps broke through the Soviet forces in the early hours of 29 June and managed to advance almost 30 km to the ], where the offensive was stopped by supply problems on 2 July. When the attack was continued a week later, the Soviets had managed to bring in reinforcements and prepare defensive positions, so the attack failed to gain ground. | |||

| ] | |||

| The XXXVI Corps attacked along the ]–] railroad on 1 July, but after only a day, the SS division "Nord" had lost its fighting capability and it took a week before the German 169th division and Finnish 6th division managed to capture ], and only two days later, the whole offensive was halted by a new Soviet fortified line. | |||

| ] | |||

| The Germans had used all their forces in the offensive and did not have any reserves left, so these had to be transported from Germany and Norway. This caused a delay in operations, which the Soviets used effectively to reinforce their positions and improve their fortifications. ] was only able to send two infantry regiments to von Falkenhorst, and their willingness to micromanage their usage lead to disagreements between OKW and von Falkenhorst, which hampered their effective usage. Because of this, the renewed offensive failed to gain any ground on 8 September at Litsa River, after which OKW ordered its forces to switch to the defensive. | |||

| Due to the war effort, the Finnish economy suffered from a lack of labour, as well as food shortages and increased prices. To combat this, the Finnish government demobilised part of the army to prevent industrial and agricultural production from collapsing.{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=96}} In October, Finland informed Germany that it would need {{convert|159000|t|ST|lk=on|abbr=on}} of grain to manage until next year's harvest. The German authorities would have rejected the request, but Hitler himself agreed. Annual grain deliveries of {{convert|180000|t|ST|abbr=on}} equaled almost half of the Finnish domestic crop. On 25 November 1941, Finland signed the ], a less formal alliance, which the German leadership saw as a "litmus test of loyalty".{{sfn|Vehviläinen|2002|p=101}}{{sfn|Goda|2015|pp=276-300}} | |||

| At Salla, XXXVI Corps fared better from 19 August, as the Finnish 6th division had cut Soviet supply routes, forcing the Soviet 104th and 122nd divisions to abandon their fortified positions and heavy equipment on 27 August. This was followed by advancing the operation along the railroad until, after almost 50 km, the attack was stopped on 19 September. Von Falkenhorst had requested reinforcements from Germany twice to continue his offensive immediately, while Soviet forces were still disorganized, but he was denied. | |||