| Revision as of 01:25, 30 October 2007 editClueBot (talk | contribs)1,596,818 edits Reverting possible vandalism by Special:Contributions/68.227.206.215 to version by 58.6.94.159. If this is a mistake, report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (47177) (Bot)← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:29, 30 October 2007 edit undoDppowell (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,413 edits rewrite intro; clean up, refine tone and redact a hint of POVNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The '''Great Irish Famine''' or '''The Great Hunger''' ('''''An Gorta Mór''''' in ]) reduced the population of ] by 25 percent between 1845 and 1851.<ref name="This Great Calamity"> This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52, Christine Kinealy, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1994, 2006, ISBN 13 978 0 7171 4011 4</ref> <ref>Christine Kinealy in “This Great Calamity” points out that “proportionately, fewer people have died in modern famines than during the Great Famine,” a point echoed by Cormac Ó Gráda in “The Great Famine and Today’s Famines” also in Cathal Póirtéir, The Great Irish Famine (Mercier Press 1995).</ref> The ] of the famine was a ] ], ''P. infestans'', commonly known as ]. Though ''P. infestans'' ravaged ] crops throughout ] during the 1840s, its human cost in Ireland was exacerbated by a host of political, social, economic, and climatological factors which remain the subject of heated historical debate. | |||

| The famine was a ] in the ]. Its effects penetrated well beyond its immediate demographic impact and permanently changed the island's political and cultural landscape. For both the native Irish and those in the resulting ], the famine entered ] and became a rallying point for various ]. Virtually all modern historians regard it as a dividing line in the Irish historical narrative, referring to the preceding period of Irish history as "pre-Famine." | |||

| The '''Great Irish Famine''' (known as '''The Great Hunger,''' '''''An Gorta Mór''''' in ], or '''''An Drochshaol,''''' '''the Bad Life'''), refers to the ], and its aftermath, in ] between 1845 and 1851. The famine was caused initially by ], which almost instantly destroyed the primary food source for the majority of the ]. The blight explains the crop failure but the dramatic and deadly effect of the famine was exacerbated by other factors of economic, political, and social origin. The impact of the Great Famine in Ireland remains unparalleled, in terms of the demographic decline, the Irish population falling by approximately 25 percent in just six years, due to a combination of “excess mortality and mass emigration.” <ref name="This Great Calamity"> This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52, Christine Kinealy, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1994, 2006, ISBN 13 978 0 7171 4011 4</ref> <ref>Christine Kinealy in “This Great Calamity” points out that “proportionately, fewer people have died in modern famines than during the Great Famine,” a point echoed by Cormac Ó Gráda in “The Great Famine and Today’s Famines” also in Cathal Póirtéir, The Great Irish Famine (Mercier Press 1995).</ref> | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

Revision as of 02:29, 30 October 2007

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (October 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Great Famine" Ireland – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Great Irish Famine or The Great Hunger (An Gorta Mór in Irish) reduced the population of Ireland by 25 percent between 1845 and 1851. The proximate cause of the famine was a pathogenic water mold, P. infestans, commonly known as potato blight. Though P. infestans ravaged potato crops throughout Europe during the 1840s, its human cost in Ireland was exacerbated by a host of political, social, economic, and climatological factors which remain the subject of heated historical debate.

The famine was a watershed in the history of Ireland. Its effects penetrated well beyond its immediate demographic impact and permanently changed the island's political and cultural landscape. For both the native Irish and those in the resulting diaspora, the famine entered folk memory and became a rallying point for various nationalist movements. Virtually all modern historians regard it as a dividing line in the Irish historical narrative, referring to the preceding period of Irish history as "pre-Famine."

Background

The famine of 1845 acquired the name An Gorta Mór because it became the most deadly of all famines preceding it. There were twenty-four failures of the potato crop according to the Census of Ireland Commissioners in 1851. The first recorded by the commissioners was 1728; in 1739 the crop was "entirely destroyed", and again in 1740, in 1770 the crop largely failed again. In 1800 there was another ‘general’ failure, and in 1807 half the crop was lost. In 1821 and 1822 the potato failed completely in Munster and Connaught, and 1830 and 1831 were years of failure in Mayo, Donegal and Galway. In 1832, 1833, 1834 and 1836 a large number of districts suffered serious loss, and in 1835 the potato failed in Ulster. 1836 and 1837 brought ‘extensive’ failures throughout Ireland and again in 1839 failure was universal throughout the country. In 1841 the potato crop failed in a lot of districts, and in 1844 the early crop was extensively lost.

According to Cecil Woodham-Smith in her notable work, The Great Hunger, “the unreliability of the potato was an accepted fact in Ireland… and in 1845 the possibility of yet another failure caused no particular alarm.” In the forty years since the union, this commission was only one in a long line of commissions “to report on the state of Ireland.” According to Woodham-Smith, there had been no fewer than 114 Commissions and 61 Special Committees, and of them she says, “without exception their findings prophesied disaster.”

From 1801 Ireland had been governed, under the Act of Union, as part of the United Kingdom. Executive power lay in the hands of a Lord Lieutenant and Chief Secretary, both of whom were appointed by the British cabinet. Within the United Kingdom parliament Ireland was represented by 105 MP’s out of a total of 656, and in addition by representative Irish peers sitting in the House of Lords. Between 1832 and 1859 seventy percent of Irish representatives were landowners or the sons of landowners.

Catholic emancipation had been achieved in 1829, and Catholics made up 80% of the population. The bulk of that population lived in conditions of poverty and insecurity. At the top of the “social pyramid” was the “Ascendancy class,” the English and Anglo-Irish families who owned most of the land, and had more or less limitless power over their tenants. Some of their estates were vast — the Earl of Lucan, for example, owned over 60,000 acres. Many of these landlords lived in England and were called ‘absentees’. They used agents to administer their property for them, with the revenue generated being sent to England. A number of the absentee landlords living in England never set foot in Ireland. They simply took their profitable rents from their “impoverished tenants” or paid them minimal wages to raise crops and livestock for export.

The 1841 census showed a population of just over 8 million. Two-thirds of those depended on agriculture for their survival, but they rarely received a working wage. They had to work for their Landlords in return for the patch of land they needed, in order to grow enough food for their own families. This was the system which forced Ireland and her peasantry to rely on a single crop, as only the potato could be grown in sufficient quantity on these tiny scraps of soil. The rights to a plot of land in Ireland meant the difference between life and death in the early 1800s.

The period of the potato blight in Ireland from 1845—51 was full of political confrontation. The mass movement for Repeal of the Act of Union had failed in its objectives by the time its founder Daniel O'Connell died in 1847. A more radical Young Ireland group seceded from the Repeal movement and attempted an armed rebellion in 1848. It was unsuccessful.

The blight took place well into the modern prosperity of the Victorian and Industrial age. Ireland at this time was, according to the Act of Union of 1801, an integral part of the British imperial homeland, “the richest empire on the globe,” and was “the most fertile portion of that empire,” in addition; Ireland was sheltered by both "...Habeas Corpus and trial by jury...". And yet Ireland's elected representatives seemed powerless to act on the country's behalf as Members to the British Parliament. Commenting on this at the time John Mitchel was to write:

That an island which is said to be an integral part of the richest empire on the globe…should in five years lose two and a half millions of its people (more than one fourth) by hunger, and fever the consequence of hunger, and flight beyond sea to escape from hunger…

Ireland even during the blight remained a net exporter of food. The immediate effect on Ireland was devastating, and its long-term effects proved immense, permanently changing Irish culture and tradition for generations. The population of Ireland continued to fall for 70 years, stabilising at half the level prior to the famine. This long-term decline ended in the west of the country only in 2006, over 160 years after the famine struck.

Causes and contributing factors

Symptoms of the potato blight were first recorded in Belgium in 1845. Plant pathologist Jean Beagle Ristanio speculates that the pathogen (not a fungus but an oomycete) arrived in Europe on a shipment of potatoes from South America in the 1830s. All of Europe's potato crop soon fell victim to the fungal infection, none more so than Ireland. The Western and South-Western counties were the hardest hit with their reputation of single crop and/or subsistence farming on tiny holdings of two acres or less. The northern province of Ulster dominated by a Protestant majority had been considerably less affected by the blight as its population had been less dependant on the potato. The development of a considerable sized manufacturing sector generated revenue which was in turn invested into farms reducing the impact of the blight..

Land consolidation

Since the act of Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII in the mid 16th century, plantations of the country followed and were undertaken under Mary I and Elizabeth I. The plantations in Counties Laois and Offaly and in Munster did not survive, but the plantation of Ulster during the reign of James I (James VI of Scotland) brought about the Protestant colonisation of Ulster territories by mainly English and Scottish Presbyterians also creating several new strategic garrison towns. An insurrection, instigated by Irish rebels in 1641, led to civil wars in Ireland, England, and Scotland, culminating in the execution of King Charles I during January of 1649 and the declaration of Britain becoming a Republic (until the restoration of the monarchy in 1660). This was followed during September of 1649 by Oliver Cromwell's conquest of Ireland, bringing a swift end to any possible Royalist resurgance and Irish led resistance to British Parliamentary rule in Ireland.

It is estimated that as much as a third of the entire population of Ireland perished during the civil wars and subsequent Cromwellian conquest. William Petty who conducted the first scientific land and demographic survey of Ireland in the 1650s (the Down Survey), concluded that at least 400,000 people and maybe as many as 620,000 had died in Ireland between 1641 and 1653 many as a result of famine and plague. And this in a country of only around 1.5 million inhabitants.

Penal laws were introduced during the reign of King William III and further reinforced during the subsequent 18th century Hanoverean period whereby Roman Catholics rights were restricted from education and many of their civil liberties were removed, including ownership of a horse worth more than five pounds. Laws were also introduced to encourage Irish linen production but wool exports were restricted. Roman Catholic clergy were also banished as the British Parliament took over to legislate for Ireland. British law then barred Roman Catholics from succession, securing the ascendancy to remain in Protestant control and therefore removing any possible claims to the throne by the Roman Catholic descendants of King James II. Land ownership in Ireland fell mainly to English and Scottish Protestants who were loyal to the crown and the Established Church who rented out large tracts to tenant farmers. Many prominent Roman Catholics who owned land prior to the Williamite Wars and Treaty of Limerick had been forced into exile, called the Flight of the Wild Geese continued to live off rental income collected by their appointed land agents. Sometimes rents grew difficult to collect, forcing the landlords into debt and causing them to sell their estates.

This period also saw the rise of economic and other colonialism, often influencing countries to produce for export a single crop. Ireland, too, became mostly a single-crop nation although the southern and eastern regions sustained a fair sized commercial agriculture of grain and cattle. The potatoes grew well in Ireland and seemed the only crop that could support a peasant family limited — through subdivision of larger Catholic-owned estates — to a very small tenant plot of land.

Tenants, subdivisions, and bankruptcy

"Subdivision" resulted from The Popery Act which was one of the Penal Laws (Ireland), enacted to discriminate against Roman Catholics. The Act divided lands and property equally among male heirs (instead of being inherited by the first-born son); over generations, tenant farm size shrank, split between all living sons. By the 1840s, subdivision resulted in Catholics working the smallest farms and so becoming ever poorer.

In 1845, for example, 24% of all Irish tenant farms were of 0.4 to 2 hectares (one to five acres) in size, while 40% were of two to six hectares (five to fifteen acres). Holdings were so small that only potatoes — no other crop — would suffice to feed a family. The British Government reported, shortly before the Great Hunger, that poverty was so wide-spread that one third of all Irish small holdings could not support their families, after paying their rent, except by earnings of seasonal migrant labour in England and Scotland. Following the famine reforms were implemented making it illegal to further divide land holdings.

By the 1840s, the Irish land-holding system was under serious strain. Many big landlord estates already carried heavy mortgages from earlier farm crises. Many small tenancies, lacking long-term leases, rent control or security of tenure, became so small and unsustainable — through subdivision — that the tenants struggled to survive even in the good years, and depended on the potato crop, as only potatoes would provide enough nutrition on such small farms. Yet, the large landlord estates — owned by absentee Britons — exported many tons of cattle and other foodstuffs to foreign markets. Any attempt by the tenant farmer to increase productivity of their land holding was actively discouraged by threats of disproportionately high increase in rent — and even eviction.

Evictions

Relief of Ireland's poor people was then directed by Poor Law legislation. The Poor Law Union raised money from rates (local taxes) on landlords, based on how many tenants farmed that estate. Renting small farms to subsistence farmers was unprofitable; the British Government used the rating system to encourage consolidation of holdings — thought more profitable and, theoretically, able to pay for those no longer able to farm.

Over half a million people were evicted during the Famine. There where also a lot of poorhouses running with many people in them.

Food exports to England

Records show Irish lands exported food, even during the worst years of the Famine. When Ireland experienced a famine in 1782-83, ports were closed to keep Irish-grown food in Ireland to feed the Irish. Local food prices promptly dropped. Merchants lobbied against the export ban, but government in the 1780s overrode their protests; that export ban did not happen in the 1840s.

Cecil Woodham-Smith, an authority on the Irish Famine, wrote in The Great Hunger; Ireland 1845-1849 that,

...no issue has provoked so much anger or so embittered relations between the two countries (England and Ireland) as the indisputable fact that huge quantities of food were exported from Ireland to England throughout the period when the people of Ireland were dying of starvation.

Ireland remained a net exporter of food throughout most of the five-year famine.

Christine Kinealy, a University of Liverpool fellow and author of two texts on the famine, Irish Famine: This Great Calamity and A Death-Dealing Famine, writes that Irish exports of calves, livestock (except pigs), bacon and ham actually increased during the famine. The food was shipped under guard from the most famine-stricken parts of Ireland. However, the poor had no money to buy food and the government then did not ban exports.

Irish meteorologist Austin Bourke, in The use of the potato crop in pre-famine Ireland disputes some of Woodham-Smith's calculations, and notes that during December 1846 imports almost doubled. He opines that

it is beyond question that the deficiency arising from the loss of the potato crop in 1846 could not have been met by the simple expedient of prohibiting the export of grain from Ireland.

The Quakers are the only Protestant religious group commonly recognised to have come to the aid of the Irish during the Great Famine but, unfortunately, often at a price more costly than gold. Quaker Alfred Webb, one of the many volunteers in Ireland at the time, wrote:

Upon the famine arose the wide spread system of proselytism...and a network of well-intentioned Protestant associations spread over the poorer parts of the country, which in return for soup and other help endeavoured to gather the people into their churches and schools...The movement left seeds of bitterness that have not yet died out, and Protestants, and not altogether excluding Friends, sacrificed much of the influence for good they might have had..."

In addition to the religious, non-religious organizations came to the assistance of famine victims. The British Relief Association was one such group. Founded in 1847, the Association raised money throughout England, America and Australia; their funding drive benefited by a "Queen's Letter", a letter from Queen Victoria appealing for money to relieve the distress in Ireland. With this initial letter the Association raised £171,533. A second, somewhat less successful "Queen's Letter" was issued in late 1847. In total, the British Relief Association raised approximately £200,000. (c.$1,000,000 at the time)

Claims of potato dependency

Irish tenant farmers, forced into smaller and smaller land holdings by the subdivision rules of the Penal Laws, depended too much on potatoes as a food. Ireland was not unique in its single-crop dependency, common among exporting nations. (For example, many countries of Asia with rice.) Ireland's rapid shift to potato cultivation about 1790 helped Ireland's population grow to overpopulated levels despite political upheaval and warfare. Soldiers and wars tend to disrupt most farming; not so for the sub-surface potato. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, potatoes were a staple for most Europeans. The blight spread across Europe, but only in Ireland were its consequences so drastic. Dispossession, subdivision, small tenant farms, and reliance on a single crop for home consumption , are just a few of many potential reasons why Ireland suffered so much more than the Continent.

Another weakness is that all the potatoes in Ireland came from a limited genetic pool, just a few imports from South America, and thus had little genetic resistance to the disease once it was introduced.

Jeremy Rifkin, in his book Beyond Beef, writes "The Celtic grazing lands of...Ireland had been used to pasture cows for centuries. The British colonized...the Irish, transforming much of their countryside into an extended grazing land to raise cattle for a hungry consumer market at home.... The British taste for beef had a devastating impact on the impoverished and disenfranchised people of..Ireland.... Pushed off the best pasture land and forced to farm smaller plots of marginal land, the Irish turned to the potato, a crop that could be grown abundantly in less favorable soil. Eventually, cows took over much of Ireland, leaving the native population virtually dependent on the potato for survival (pp. 56,57)."

Death toll

No one knows how many people died during the period of the Famine, although most died from diseases like cholera and typhus which were widespread throughout Europe at that time. State registration of births, marriages or deaths had not yet begun, while records kept by the Roman Catholic Church are incomplete.Many of the Church of Ireland's records (which included records of local Catholics due to the collection of Tithes (10% of income) from Catholics to finance the Church of Ireland) were destroyed in the Four Courts records office during the Civil War in 1922, as were most of the civil census records undertaken between 1821 and 1901.

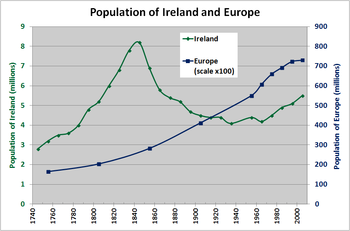

One possible estimate has been reached by comparing the expected population with the eventual numbers in the 1850s (see Irish Population Analysis). Earlier predictions expected that by 1851 Ireland would have a population of eight to nine million. A census taken in 1841 revealed a population of slightly over 8 million. A census immediately after the famine in 1851 counted 6,552,385, a drop of almost 1,500,000 in ten years. Modern historians and statisticians estimate that between 800,000 and 1,000,000 died from disease and starvation. In addition, in excess of one million Irish emigrated to Great Britain, United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere, while more than one million emigrated over following decades.

| Leinster | Munster | Ulster | Connaught | Ireland |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.3 | 22.5 | 15.7 | 28.8 | 20 |

| Table from Joe Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society (Gill History of Ireland Series No.10) p.2 | ||||

Detailed statistics into the population of Ireland since 1841 are available at Irish Population Analysis.

Reactions

As early as 1844, John Mitchel, one of the leading political writers of Young Ireland, raised the issue of the "Potato Disease" in The Nation; he noted how powerful an agent hunger had been in certain revolutions. Mitchel again in The Nation in 1846 (14 February), put forward his views on "the wretched way in which the famine was being trifled with”, and asked, had not the Government even yet any conception that there might be soon "millions of human beings in Ireland having nothing to eat." On 28 February, writing on the Coercion Bill which was then going through the House of Lords, he writes,

This is the only kind of legislation for Ireland that is sure to meet with no obstruction in that House. However they may differ about feeding the Irish people, they agree most cordially in the policy of taxing, prosecuting and ruining them.

In an article on "English Rule" on 7 March, Mitchel wrote:

The Irish People are expecting famine day by day... and they ascribe it unanimously, not so much to the rule of heaven as to the greedy and cruel policy of England. Be that right or wrong, that is their feeling. They believe that the season as they roll are but ministers of England’s rapacity; that their starving children cannot sit down to their scanty meal but they see the harpy claw of England in their dish. They behold their own wretched food melting in rottenness off the face of the earth, and they see heavy-laden ships, freighted with the yellow corn their own hands have sown and reaped, spreading all sail for England; they see it and with every grain of that corn goes a heavy curse. Again the people believe—no matter whether truly or falsely—that if they should escape the hunger and the fever their lives are not safe from judges and juries. They do not look upon the law of the land as a terror to evil-doers, and a praise to those who do well; they scowl on it as an engine of foreign rule, ill-omened harbinger of doom."

Mitchel because of his writings was charged with sedition, but this charge was dropped, and he was convicted under a new law purposefully enacted of Treason Felony Act and sentenced to 14 years transportation.

1848 rebellion

Main article: Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848

In 1847 William Smith O'Brien, the leader of the Young Ireland party, became one of the founding members of the Irish Confederation to campaign for a Repeal of the Act of Union, and called for the export of grain to be stopped and the ports closed. The following year he organised the resistance of landless farmers in County Tipperary against the landowners and their agents.

Response of United Kingdom Government

The initial British government policy towards the famine was, in the view of historians such as F.S.L. Lyons, "very delayed and slow". Professor Joe Lee contends: "There was nothing unique (by the standards of pre-industrial subsistence crisis) about the famine. The death rate had been frequently equalled in earlier European famines, including, possibly, in Ireland itself during the famine of 1740–41". This 1740–1741 famine is commonly referred to as The Forgotten Famine. Commonly, the government would encourage landowners to evict their tenants.

In 1845 Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel took steps to alleviate the growing famine in Ireland: he purchased American maize, which was then re-sold for a penny a pound, and in 1846 moved to repeal the Corn Laws, tariffs on grain which kept the price of bread artificially high. The Irish called the maize imported by the government 'Peel's brimstone' — partly because of maize's yellow colour, and partly because it had to be ground twice. Repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 did little to help the starving Irish; the measure split the Conservative Party, leading to the fall of Peel's ministry. Succeeding him was a Whig ministry under Lord John Russell, later Earl Russell. Russell's ministry focused on providing support through "public works" projects. Such projects mainly consisted of the government employing Irish peasantry on wasteful projects, such as filling in valleys and flattening hills, so the government could justify the cash payments. Such projects proved counterproductive, as starving labourers expended the energy gained from low rations on the heavy labour. Furthermore, prospects of paid labour influenced Irish peasants to remain at work, far from their farmlands. So they did not farm, which fact worsened the famine. Eventually, a soup-kitchen network, which fed three million people, replaced the public works projects.

In the autumn of 1847, the soup kitchens were shut down and responsibility for famine relief was transferred to the Poor Laws unions, through the raising of Poor Law taxes. The Irish Poor Laws were even harsher on the poor than their English counterparts; those paupers with over a quarter-acre of land were expected to abandon it before entering a workhouse — something many of the poor would not do. Furthermore, Ireland had too few workhouses. Many of the workhouses that existed were closed due to financial problems; authorities in London refused to give large amounts of aid to bankrupt Poor Laws unions. Therefore, disaster became inevitable; only about a million people were on workhouse relief rolls on any given day.

In 1849 London finally came up with a plan to save bankrupt Poor Laws Unions that were offering little or no relief; however, it was primarily funded by a tax on Ulster (the then most-prosperous part of Ireland) rather than by the Imperial treasury. As such, it was seen as a violation of the spirit of the Act of Union.

Britain tried in turn government direct aid, reliance on private charities (some to be financed by taxes on landlords), public works programs, soup kitchens, workhouses, and a laissez-faire policy backed by military force. Nothing worked, or, if something did work, it was not funded sufficiently. Discussions then on how to solve this problem so closely mirror modern-day arguments as to suggest that close study of the Potato Famine might yet help the modern world.

Charity

Large sums of money were donated by charities; Calcutta is credited with making the first donation of £14,000. The money was raised by Irish soldiers serving there and Irish people employed by the East India Company. Pope Pius IX sent funds, Queen Victoria donated £2,000 while the Choctaw Indians themselves victims of the genocidal Trail of Tears famously sent $170 (although many articles say the original amount was $710 after a misprint in Angi Debo's "The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Nation") and grain, an act of generosity still remembered to this day, and publicly commemorated by President Mary Robinson on the 150th anniversary of the famine.

Aftermath

Main article: Irish potato famine (legacy)

Potato blights continued in Ireland, especially in 1872 and 1879–1880. These killed few people, partly because they were less severe, but mainly for a complex range of reasons. However, on the other hand, the population in Ireland soon shrank from over 8 million to about 6 million due to starvation and exodus from the famine. The growth in the numbers of railways made the importation of food easier; in 1834, Ireland had 9.7 km (6 miles) of railway tracks; by 1912, the total was 5 480 km (3,403 miles). The banning of subdivision, coupled with emigration, increased the average farm size; greater acreage let farmers grow crops other than potatoes alone. The increasing wealth in urban areas meant alternative sources of food, grain, potatoes and seed were available in towns and villages. The 1870s agricultural economy thus was more efficient and less dependent on potatoes, as well as having access to new farm machinery and product control.

After the famine the Encumbered Estates Act completely reorganized agriculture during 1870s–1900s, as small owned farms replaced mass estates and multiple tenants. Many of the large estates in the 1840s were debt-ridden and heavily mortgaged. In contrast, estates in the 1870s, many of them under new Irish middle class owners thanks to the Encumbered Estates Act, were on a better economic footing, and so capable of reducing rents and providing locally organized relief, as was the Roman Catholic Church, which was better organised and funded than it had been in 1847–49.

If subdivision produced earlier marriage and larger families, its abolition produced the opposite effect; the 'inheriting' child would wait until they found the 'right' partner, preferably one with a large dowry to bring to the farm. Other children, no longer with the possibility of inheriting a farm (or part of it at least) had no economic attraction and no financial resources to consider an early marriage. Later marriages contributed to the plummeting birthrate resulting in a further population decrease.

Consequently, later mini-famines made only minimal effect and are generally forgotten, except by historians. By the 1911 census, the island of Ireland's population had fallen to 4.4 million, about the same as the population in 1800 and 2000 and only a half of its peak population.

The same water mould (Phytophthora infestans) was responsible for the 1847–51 and later famines. When people speak of "the Irish famine", or "an Gorta Mór", they nearly always mean the one of the 1840s, even though a similar Great Famine did in fact hit in the early 18th century. The fact that only four types of potato were brought from the Americas was a fundamental cause of the famine, as the lack of genetic diversity made it possible for a single oomycete to have much more devastating consequences than it might otherwise have had.

Emigration

See also: Irish diaspora

While the famine in question was responsible for a massive increase of anywhere from 45% to nearly 85%, depending on the year and the county, of emigration from Ireland it was not the sole cause, nor even the era when massive emigration became a fact of life in Ireland. That can be traced to the 1814-1815 post-Napoleon world when cereal crops and linen -- Ireland's two primary exports -- which had commanded high prices during the war years, collapsed with the advent of peace in Europe; the famine merely quickened the pace. From the defeat of Napoleon and the beginning of the famine "at least 1,000,000 and possibly 1,500,000 emigrated" During the worst of the famine emigration reached somewhere around 250,000 per year, with far more emigrates coming from western Ireland than any other.

Two other notions concerning Irish emigration at this time are generally mistaken:

- Families did not emigrate. Individual members did.

While it is undeniable that eviction(s) played a key role, another factor was excess population and the desire to keep the family farm and land holding intact. This meant that, as a rule, families en masse did not emigrate, younger members of it did. So much so that emigration almost became a rite of passage, as evidenced by the data that show that, unlike similar emigration throughout world history, women emigrated just as often, just as early, and in the same numbers as men. The emigrant started a new life in a new land, sent remittances "reached £1,404,000 by 1851" back to his/her family in Ireland which, in turn, allowed another member of the family to emigrate.

The massive influx of Irish to the United States, over any other country, came mainly in the final quarter of the nineteenth and first quarter of the twentieth century. Generally speaking, emigration during the famine years of 1845 to 1850 was to England, Scotland, the United States, Canada, and Australia.

By 1854, between 1½ and 2 million Irish left their country due to evictions, starvation, and harsh living conditions. In America, most Irish became city-dwellers: with little money, many had to settle in the cities that the ships they came on landed in. By 1850, the Irish made up a quarter of the population in Boston, Massachusetts; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Baltimore, Maryland. In addition, Irish populations became prevalent in some American mining communities.

The 1851 census reported that more than half the inhabitants of Toronto, Ontario were Irish, and in 1847 alone, 38,000 famine Irish flooded a city with less than 20,000 citizens. Other Canadian cities such as Saint John, New Brunswick; Quebec City and Montreal, Quebec; Ottawa, Kingston and Hamilton, Ontario also received large numbers of Famine Irish since Canada, as part of the British Empire, could not close its ports to Irish ships (unlike the United States), and they could get passage cheaply (or free in the case of tenant evictions) in returning empty lumber holds. However fearing nationalist insurgencies the British government placed harsh restrictions on Irish immigration to Canada after 1847 resulting in larger influxes to the United States. The largest Famine grave site outside of Ireland is at Grosse-Île, Quebec, an island in the St. Lawrence River used to quarantine ships near Quebec City. In 1851, about a quarter of Liverpool's population was Irish-born.

The Famine is often seen as an initiator in the steep depopulation of Ireland in the 19th century. However, some say that it is likely that real population began to fall in 1841 with the Famine accelerating any population changes already occurring. They argue the Famine was necessary to restore population equilibrium to Ireland given that population increased by 13–14% in the first three decades of the 19th century using Thomas Malthus's idea of population expanding geometrically while resources increase arithmetically. Between 1831 and 1841 population grew by 5%. Application of Malthus's writings to Ireland were popular during the famines of 1817 and 1822> However by the 1830's, a decade before the potato famine, they were seen as overly simplistic and Ireland's problems were seen "less as an excess of population than as a lack of capital investment."

The mass exodus in the years following the famine must be seen in the context of overpopulation, industrial stagnation, land shortages, religious discrimination, declining agricultural employment and inadequate diet. These factors were already combining to choke off population growth by the 1830s. It would be wrong, therefore, to attribute all the population loss during the famine to the potato blight alone.

Judgement of the government's handling of the Famine

| This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Misplaced Pages's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. |

Contemporary opinion

- John Mitchel, one of the leaders of the Young Ireland Movement, wrote the following in 1860: "I have called it an artificial famine: that is to say, it was a famine which desolated a rich and fertile island, that produced every year abundance and superabundance to sustain all her people and many more. The English, indeed, call the famine a "dispensation of Providence;" and ascribe it entirely to the blight on potatoes. But potatoes failed in like manner all over Europe; yet there was no famine save in Ireland. The British account of the matter, then, is first, a fraud - second, a blasphemy. The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine."

- Mitchel was to go on to say in his book "An Apology for the British Government in Ireland," in Paris 1860, "If my ‘Apology’ then, shall help to convince my countrymen, and the world—that the English are not more sanguinary and atrocious than any other people would be in like case, and under like exigencies—that the disarmament, degradation, extermination and periodical destruction of the Irish people, are measures of policy dictated not by pure malignity but by the imperious requirements of the system of Empire administered in London—that they must go on, precisely as at present, while the British Empire goes on—and that there is no remedy for them under heaven save the dismemberment of that Empire—then the object of my writing shall have been attained."

- The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Earl of Clarendon wrote a letter to Prime Minister Russell on April 26th, 1849, to express his feelings about need of aid from the British House of Commons: "I do not think there is another legislature in Europe that would disregard such suffering as now exists in the west of Ireland, or coldly persist in a policy of extermination."

- Professor Nassau Senior, a respected economics professor at Oxford University was to say at the time of the Famine in Ireland that it "would not kill more than one million people, and that would scarcely be enough to do any good." In 1852 Professor Nassau was told by his brother, himself an Irish poor-law commissioner, that “The great instrument which is clearing Ireland is the poor law. It supplies both the motive and the means. - It was passed for the purpose of relieving England and Scotland at the expense of Ireland; it will probably relieve Ireland at the expense of England and Scotland.”

- In 1848, Denis Shine Lawlor suggested that Lord John Russell was a student of the Elizabethan poet Spenser, who had inhumanely calculated "how far English colonization and English policy might be most effectively carried out by Irish starvation."

- Charles E. Trevelyan in his book The Irish Crisis (1848), describe the Famine as “a direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful Providence”, one which laid bare “the deep and inveterate root of social evil”; the Famine, he affirmed, was “the sharp but effectual remedy by which the cure is likely to be effected. God grant that the generation to which this opportunity has been offered may rightly perform its part. . .” Trevelyan was to have similar views in relation to the “Poor Laws”, “The principle of the poor law is that rate after rate should be levied for the preservation of life, until the landowners and farmers enable the people either to support themselves by honest industry or to dispose of their property to those who can and will perform this indispensable duty.”

- On April 1, 1848, an editorial writer in The Nation said, "It is evident to all men that our foreign government is but a club for grave-diggers...we are decimated not by the will of God but the will of the Whigs."

- When the Irish Poor Law Commissioner, Edward Twisleton resigned in protest over lack of relief aid from Britain, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Earl of Clarendon, wrote the to British Prime Minister Lord John Russell: "He (Twisleton) thinks that the destitution here is so horrible, and the indifference of the House of Commons is so manifest, that he is an unfit agent for a policy that must be one of extermination."

- Later in 1849 Edward Twisleton testified that "comparatively trifling sums were required for Britain to spare itself the deep disgrace of permitting its miserable fellow subjects to die of starvation." According to Peter Gray, in his book The Irish Famine, British spent 7 million Pounds for relief in Ireland between 1845 and 1850, "representing less than half of one percent of the British gross national product over five years. Contemporaries noted the sharp contrast with the 20 million Pounds compensation given to West Indian slave-owners in the 1830s."

- Lord Lansdowne’s agent W. S. Trench in September 1852 was to say of the potato blight: “Nothing but the successive failures of the potato ...could have produced the emigration which will, I trust, give us room to become civilised.”

Historical opinion

- Oxford history professor James Anthony Froude, wrote in his book, English in Ireland "England governed Ireland for what she deemed her own interest, making her calculations on the gross balance of her trade ledgers, and leaving moral obligations aside, as if right and wrong had been blotted out of the statute book of the Universe."

- Professor Dennis Clark, an Irish-American historian, wrote in his The Irish in Philadelphia, about the famine that it was "the culmination of generations of neglect, misrule and repression. It was an epic of English colonial cruelty and inadequacy. For the landless cabin dwellers it meant emigration or extinction..."

- Dr. Gideon Polya writes that "An extraordinary feature of the appalling record of British imperialism with respect to genocide and mass, world-wide killing of huge numbers of people (by war disease and famine) is its absence from public perception. Thus, for example, inspection of a selection of British history texts reveals that mention of the appalling Irish Famine of 1845-47 is confined in each case to several lines (although there is of course detailed discussion of the attendant, related political debate about the Corn Laws). It is hardly surprising that there should be no mention of famine in India or Bengal."

- Christine Kinealy writes in her book The Great Calamity, "While it was evident that the government had to do something to help alleviate the suffering, the particular nature of the actual response, especially following 1846, suggests a more covert agenda and motivation. As the Famine progressed, it became apparent that the government was using its information not merely to help it formulate its relief policies, but also as an opportunity to facilitate various long-desired changes within Ireland. These included population control and the consolidation of property through various means, including emigration... Despite the overwhelming evidence of prolonged distress caused by successive years of potato blight, the underlying philosophy of the relief efforts was that they should be kept to a minimalist level; in fact they actually decreased as the Famine progressed."

- Leon Uris has suggested that, "There was ample food within Ireland", while all the Irish-bred cattle were being shipped off to England. Again this contributes to the theory that the Irish Potato Famine was not inevitable and could have possibly been prevented.

- Fifty years later G.B. Shaw wrote in Man and Superman: "Malone: 'My father died of starvation in Ireland in the Black '47. Maybe you've heard of it?' Violet: 'The Famine?' Malone: (with smoldering passion) 'No, the Starvation. When a country is full of food and exporting it, there can be no Famine."'

Suggestions of Genocide

- Dr Dan Ritschel of the University of Maryland quotes a 1996 report commissioned by the New York-based Irish Famine/Genocide Committee, written by F.A. Boyle, a law professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, which concluded that: "Clearly, during the years 1845 to 1850, the British government pursued a policy of mass starvation in Ireland with intent to destroy in substantial part the national, ethnic and racial group commonly known as the Irish People.... Therefore, during the years 1845 to 1850 the British government knowingly pursued a policy of mass starvation in Ireland that constituted acts of genocide against the Irish people within the meaning of Article II (c) of the 1948 Genocide Convention."

- However, Ritschel adds that "although this account has long been the orthodoxy of Irish nationalism in both the 19th and 20th centuries, only one modern Irish historian, Cecil Woodham-Smith, can be said to have endorsed this position. Most historians find it impossible to sustain the charge of deliberate genocide, since there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that the famine was planned or deliberately prolonged by the British with the intent of destroying the Irish population".

- Although in an article in the Washington Post newspaper 17 September 1997 Timothy Guinnane, associate professor of economics at Yale, wrote: “Several states have mandated that the Great Irish Famine of 1845—1850 be taught in their high schools as an example of genocide.”

- In the US, on the 150 anniversary of the Famine, the Governor of New York, George Pataki, signed a Bill which would legally require high school students to study the Great Famine. History teaches us, he said, “that the Great Hunger was not the result of a massive Irish crop failure, but rather a deliberate campaign by the British to deny the Irish people the food they needed to survive.”

- Robert Kee, author, journalist, and documentary maker, suggests that the Famine is still seen as “comparable” in its force on “popular national consciousness to that of the ‘final solution’ on the Jews,” and that it is not “infrequently” thought that the Famine was something very like, “a form of genocide engineered by the English against the Irish people.” According to Kee, “the story of what happened in Ireland in those years is deeply disturbing.” This particular view has been enunciated by reputable scholars such as A. J. P. Taylor, the distinguished historian. In his Essays in English History, under the title “Genocide,” he described the country during the Famine and wrote “all Ireland was a Belsen". “The English governing class ran true to form, he said, “they had killed two million Irish people.” That the death toll during the Famine was not higher, Taylor remarked that it “was not for the want of trying.”

- Professor Peter Gray a Cambridge-educated and Belfast-born historian, in his book Ideology and the Famine says "It is difficult to refute the indictment made by one humanitarian English observer in the later stages of the Famine, that amidst 'an abundance of cheap food...very many have been done to death by pure tyranny'. The charge of culpable neglect of the consequences of policies leading to mass starvation is indisputable. That a conscious choice to pursue moral or economic objectives at the expense of human life was made by several ministers is also demonstrable, but he concluded, that British government's policy "was not a policy of deliberate genocide", but a dogmatic refusal to admit the policy was wrong and "amounted to a sentence of death to many thousands."

- Professor James Donnelly, a historian at the University of Wisconsin, wrote in his work Landlord and Tenant in Nineteenth-Century Ireland, "I would draw the following broad conclusion: at a fairly early stage of the Great Famine the government's abject failure to stop or even slow down the clearances (evictions) contributed in a major way to enshrining the idea of English state-sponsored genocide in Irish popular mind. Or perhaps one should say in the Irish mind, for this was a notion that appealed to many educated and discriminating men and women, and not only to the revolutionary minority...And it is also my contention that while genocide was not in fact committed, what happened during and as a result of the clearances had the look of genocide to a great many Irish..."

Memorials to the famine

The Great Famine is still remembered in many locations throughout Ireland, especially in those regions that suffered the greatest losses, and also in cities overseas with large populations descended from Irish immigrants.

In Ireland

- Strokestown Park Famine Museum, Ireland

- Custom House Quays, Dublin, Ireland. Painfully thin sculptural figures, by artist Rowan Gillespie, stand as if walking towards the emigration ships on the Dublin Quayside.

- Murrisk, County Mayo, Ireland. This sculpture of a famine ship, near the foot of Croagh Patrick, depicts the refugees it carries as dead souls hanging from the sides.

- Donaghmore Famine Museum - set in Donaghmore Workhouse in County Laois.

- Doolough, County Mayo. A memorial commemorates famine victims who walked from Louisburgh along the mountain road to Delphi Lodge to seek relief from the Poor Board who were meeting there. Returning after their request was refused, many of them died at this point.

- Doagh Island, Inishowen, County Donegal, Ireland. Doagh Visitor Centre and Famine Museum has exhibits and memorial on the effects of the potato famine in Inishowen, Donegal.

- Ennistymon, County Clare, Ireland. This was the first memorial in Ireland to honour those who suffered and were lost during the Great Famine. It is erected across the street from an abandoned workhouse where an estimated 20,000 Irish died and a mass graveyard for children who perished and were buried without coffins.

In England

- Liverpool, England. A memorial is in the grounds of St Luke's Church on Leece Street, itself a memorial to the victims of the Blitz. It recalls that from 1849–1852 1,241,410 Irish immigrants arrived in the city and that from Liverpool they dispersed to locations around the world. Many died despite the help they received within the city, some 7000 in the city perish within one year. The sculpture is dedicated to the memory of all famine emigrants and their suffering. There is also a plaque on the gates to Clarence Dock. Unveiled in 2000, the plaque inscription reads in Gaelic and English: "Through these gates passed most of the 1,300,000 Irish migrants who fled from the Great Famine and 'took the ship' to Liverpool in the years 1845–52" The Maritime Museum, Albert Dock, Liverpool has an exhibition regarding the Irish Migration, showing models of ships, documentation and other facts on Liverpool's history, The history started in 190.

- Newcastle and Tyneside saw the Irish population rise to over 8% of overall population between the census years 1841-1851, mainly migrants arriving from Ulster via Cumbria seeking out manual employment in the coal mines and shipyards, while the women worked in mills and potteries.

In Wales

- Cardiff, Wales. A Celtic Cross made of Irish Limestone on a base of Welsh stone stands in the city's Cathays Cemetery. The cross was unveiled in 1999 as the high point in the work of the Wales Famine Forum, remembering the 150th Anniversary of the famine. The memorial is dedicated to every person of Irish origin, without distinction on grounds of class, politics, allegiance or religious belief, who has died in Wales.

In Scotland

- Carfin,Motherwell,Lanarkshire. A Celtic Cross memorial unveiled by An Taoiseach Bertie Ahern in the early 21st Century.

In North America

- In Boston, Massachusetts, a bronze statue located at the corner of Washington and School Streets on the Freedom Trail depicts a starving woman, looking up to the heavens as if to ask "Why?", while her children cling to her. A second sculpture shows the figures hopeful as they land in Boston.

- Buffalo, New York has a stone memorial on its waterfront.

- Cambridge, Massachusetts has a memorial to the famine on its Common.

- Chicago, Illinois

- Cleveland, Ohio A 12 foot high stone Celtic cross, located on the east bank of the Cuyahoga River.

- In Fairfield, Connecticut a memorial to the Famine victims stands in the chapel of Fairfield University.

- Grosse-Île, Quebec, Canada, the largest famine grave site outside of Ireland. A large Celtic cross, erected by the Ancient Order of Hibernians, stands in remembrance overlooking the St. Lawrence River. The island is a Canadian national historic site.

- In Hamden, Connecticut, a collection of art and literature from the Great Famine is on display in the Lender Family Special Collection Room of the Arnold Bernhard Library at Quinnipiac University.

- Irish Hills, Michigan — The Ancient Order of Hibernian's An Gorta Mor Memorial is located on the grounds of St. Joseph's Shrine in the Irish Hills district of Lenawee County, Michigan. There are thirty-two black stones as the platform, one for each county. The grounds are surrounded with a stone wall. The Lintel is a step from Penrose Quay in Cork Harbor. The project was the result of several years of fundraising by the Ancient Order of Hibernians in Lenewee County. It was dedicated in 2004 by AOH Divisional President, Patrick Maguire, and many political and Irish figures from around the state of Michigan.

- Quebec City, Quebec, Canada, 12-foot limestone cross donated by the government of Ireland in 1997

- Keansburg, NJ has a Hunger Memorial in Friendship Park on Main Street.

- Kingston, Ontario, Canada, has three monuments. Celtic cross at An Gorta Mor Park on the waterfront. Another is located at Skeleton (McBurney) Park (formerly Kingston Upper Cemetery). Angel of Resurrection monument, first dedicated in 1894 at St. Mary's cemetery.

- Maidstone, Ontario, Canada, has a nine foot stone Celtic Cross at the cemetery outside St. Mary's Church

- Montreal, Quebec, Canada, the "Boulder Stone" in Pointe-Saint-Charles

- New York, New York has the Irish Hunger Memorial which looks like a sloping hillside with low stone walls and a roofless cabin on one side and a polished wall with lit (or white) lines on the other three sides. The memorial is in Battery Park City, a short walk west from the World Trade Center site. See . Another memorial exists in V.E. Macy Park in Ardsley, New York about 32 km north of Manhattan.

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Phoenix, Arizona has a famine memorial in the form of a dolmen at the Irish Cultural Center.

- Toronto, Ontario Four bronze statues arriving at the Toronto wharves, at Ireland Park on Bathurst Quay, modeled after the Dublin Departure Memorial. List of names of those who died of typhus in the Toronto fever sheds shortly after their arrival. Current memorial plaque at Metro Hall. Also a pieta statue outside St. Paul's Catholic Basilica in memory of the famine victims and Bishop Michael Power, who died tending to the sick.

In Australia

- Sydney, Australia. The Australian Monument to the Great Irish Famine is located in the courtyard wall of the Hyde Park Barracks, Macquarie Street Sydney. It symbolises the experiences of young Irishwomen fleeing the Great Irish Famine of 1845–49, and was sculpted by Angela and Hossein Valamanesh.

| This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. |

See also

- Great Irish Famine (1740-1741)

- Irish potato famine (legacy) (continuation of this article)

- Highland Potato Famine (1846 - 1857) (agrarian crisis in Scotland at the same time)

- List of natural disasters in the United Kingdom

- "Fields of Athenry," a popular song about the famine

- List of famines

- Holodomor

Books By Young Irelanders (Irish Confederation)

- The Felon's Track, by Micheal Doheny, M.H. Gill &Sons, LTD. 1951. (Text at Project Gutenberg)

- An Apology for the British Government in Ireland. By John Mitchel.O Donoghue & Company. 1905

- Jail Journal: by John Mitchel, M.H. Gill &Sons, LTD. 1914.

- Jail Journal: with continuation in New York & Paris, by John Mitchel, M.H. Gill & Son, Ltd

- The Crusade of the Period, by John Mitchel, Lynch, Cole & Meehan, 1873.

- Last Conquest Of Ireland (Perhaps), by John Mitchel, Lynch, Cole & Meehan, 1873.

- History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the present time, by John Mitchel, Cameron & Ferguson

- History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the present time, (2 Vol), by John Mitchel, James Duffy, 1869.

- My Life In Two Hemispheres, (2Vol), Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, T.Fisher Unwin, 1898.

- Young Ireland, Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. 1880.

- Four Years of Irish History 1845-1849, Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. 1888.

- A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics, Thomas D'Arcy McGee, Cameron & Ferguson (Text at Project Gutenberg)

Additional reading

- Mary E. Daly, The Famine in Ireland

- R. Dudley Edwards and T. Desmond Williams (eds.), The Great Famine: Studies in Irish history 1845-52

- Peter Gray, The Irish Famine

- Joseph O'Connor, Star of the Sea

- Cormac Ó Gráda, An Economic History of Ireland

- Cormac O Grada, Black '47 and Beyond

- Robert Kee, Ireland: A History (ISBN 0349106789)

- Christine Kinealy, This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845 - 1852

- John Mitchel, The Last Conquest of Ireland (1861) (University College Dublin Press reprint, 2005 paperback) ISBN I-904558-36-4

- Cecil Woodham-Smith, The Great Hunger, 1845-49 (Penguin, 1991 edition)

- Marita Conlon-McKenna, Under the Hawthorn Tree

- Thomas Gallagher, Paddy's Lament, Ireland 1846-1847: Prelude to Hatred

- Canon John O'Rourke, The Great Irish Famine (ISBN 1853900494 Hardback) (ISBN 185390130X Paperback) Veritas Publications 1989. First published in 1874.

- Liam O'Flaherty, Famine

- Colm Tóibín and Diarmaid Ferriter, The Irish Famine, ISBN 1-86197-249-0 / 9781861972491 (first edition, hardback)

Notes and references

- ^ This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52, Christine Kinealy, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1994, 2006, ISBN 13 978 0 7171 4011 4 Cite error: The named reference "This Great Calamity" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Christine Kinealy in “This Great Calamity” points out that “proportionately, fewer people have died in modern famines than during the Great Famine,” a point echoed by Cormac Ó Gráda in “The Great Famine and Today’s Famines” also in Cathal Póirtéir, The Great Irish Famine (Mercier Press 1995).

- ^ Woodham-Smith, Cecil, The Great Hunger; Ireland 1845-1849 Penguin Books, London, England, 1991

- ^ Cathal Póirtéir, The Great Irish Famine, RTE/Mercier Press, 1995, ISBN 1 856351114.

- Helen Litton, The Irish Famine: An Illustrated History, Wolfhound Press, 1994, ISBN 0 86327-912-0

- ^ Edward Laxton, The Famine Ships: The Irish Exodus to America 1846-51, Bloomsbury, England, 1997, ISBN 0 7475 3500 0

- ^ Last Conquest Of Ireland (Perhaps)], John Mitchel, Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873

- Peter Berresford Ellis, Eyewitness to Irish History, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2004, ISBN 0 471 26633 7

- Central Statistics Office: 2006, Census 2006: Preliminary Report, Stationery Office: Dublin

- ^ Richard Killen, A Short History of Modern Ireland (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan Ltd., 2003),p.38 Cite error: The named reference "A Short History of Modern Ireland" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- BBC The curse of Cromwell

- Robert Kee, The Laurel and the Ivy: The Story of Charles Stewart Parnell and Irish Nationalism p.15.

- Jill and Leon Uris,Ireland A Terrible Beauty(New York,Bantam Books,2003),p.15.

- King, Carla (ed), Famine, Land and culture in Ireland. University College Dublin Press (February 2001)

- Alfred Webb, unpublished biography, c.1868, p. 120-122

- Civil registration of births and deaths in Ireland was not established by law until 1863. Available: http://www.groireland.ie/history.htm Accessed 20 October 2007.

- Vaughan,W.E. and Fitzpatrick,A.J.(eds). Irish Historical Statistics, Population, 1821/1971. Royal Irish Academy, 1978

- Joe Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society p.1. Cormac Ó Grada suggests the higher number of one million.

- C.Ó Gráda and Joel Mokyr, 'New developments in Irish Population History 1700-1850', Economic History Review, vol. xxxvii, no.4 (November 1984), pp473-488.

- The Nation Newspaper, 1st November, 1844.

- Young Ireland, T. F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd. 1945

- The Nation Newspaper, 1846

- The Nation Newspaper, 1846

- Michael Doheny’s The Felon’s Track, M.H. Gill & Son, LTD, 1951 Edition

- History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the present time (2 Vol). By John Mitchel James Duffy 1869. pg414

- FSL Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine p.42.

- Lee, op.cit p.1.

- Robert Blake, Disraeli, 221-241.

- C.Ó. Gráda, A Note on Nineteenth Emigration Statistics, Population Studies, Vol. 29, No.1 (March 1975)

- Foster, R.F. ,The History of Ireland: 1600-1972,(The Peguine Press, England, 1988) p. 371

- ibid. #2, p.268

- Peter Gray, 1995, The Irish Famine, Thames and Hudson:London

- Gallagher, Michael & Thomas, Paddy's Lament. Harcourt Brace & Company, New York / London, 1982.

- An Apology for the British Government in Ireland. By John Mitchel.O Donoghue & Company. 1905

- Gallagher, Michael & Thomas, Paddy's Lament. Harcourt Brace & Company, New York / London, 1982.

- 48 Nassau W. Senior, Journals, Conversations, and Essass Relating to Ireland, (2vols., 2nd cd., London, 1868)

- Donnelly, James S., Jr., "Mass Eviction and the Irish Famine: The Clearnaces Revisited", from The Great Irish Famine, edited by Cathal Poirteir. Mercier Press, Dublin, Ireland. 1995.

- Charles E. Trevelyan, The Irish Crisis, (London 1848).

- The Nation, April, 1848.

- Gray, Peter, The Irish Famine, Discoveries: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, London, 1995

- 48 Nassau W. Senior, Journals, Conversations, and Essays Relating to Ireland, (2vols., 2nd cd., London, 1868)

- MacManus, Seumas, The Story of the Irish Race, The Irish Publishing Co.

- Dr. Polya says that "British disinclination to respond with urgency and vigor to food deficits resulted in a succession of about 2 dozen appalling famines during the British occupation of India." These swept away tens of millions of people. One of the worst famines was that of 1770 that killed an estimated 10 million people in Bengal (one third of the population) and which was "exacerbated by the rapacity of the (British) East India Company".

- Jill and Leon Uris,Ireland A Terrible Beauty(New York,Bantam Books,2003),p.16.

- Dan Ritschel, ?, "The Irish Famine: Interpretive & Historiographical Issues", Department of History, University of Maryland

- The Irish Famine: Interpretive & Historiographical Issues, Dr. Dan Ritschel, Department of History, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 2004

- Colm Tóibín and Diarmaid Ferriter, The Irish Famine, ISBN 1-86197-249-0 / 9781861972491

- Colm Tóibín and Diarmaid Ferriter, The Irish Famine, ISBN 1-86197-249-0 / 9781861972491

- Robert Kee, Ireland A History (New Edition), Butler & Tanner, London, 2005, ISBN 0 349 11676 8

- Tom Hayden, Irish Hunger, Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1998, ISBN 1 57098 233 3

- Gray, Peter, "Ideology and the Famine" in The Great Irish Famine Poirteir, Cathal, Editor, Mercier Press, Dublin, Ireland. 1995

- Donnelly, James S., Jr., "Mass Eviction and the Irish Famine: The Clearances Revisited", from The Great Irish Famine, edited by Cathal Poirteir. Mercier Press, Dublin, Ireland. 1995.

- http://www.tourclare.com/faminememorial.php

- http://www.boston.com/famine/

- Ireland Park Foundation website

- www.irishfaminememorial.org

- Historic Houses Trust: Hyde Park Barracks

- Australian Irish Famine Memorial: Artists

External links

- New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education 1996

- The History of the Irish Famine by Rev. John O'Rourke

- Irish National Archives information on the Famine

- Quinnipiac University's An Gorta Mor site - includes etexts

- Ireland's Great Famine (Cormac Ó Gráda) from EH.Net Encyclopedia of Economic History

- Irish Holocaust

- History

- Newspaper Reports on the Famine

- Ireland: The hunger years 1845-1851

- Local History Website on the Famine

- Kids History Website about the Famine

- Cork Multitext Project article on the Famine, by Donnchadh Ó Corráin

- For more on the pathogen see http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/mar2001.html

- Karp, Ivan. Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations.

- Irish Holocaust

- Seamus P. Metress, Richard A. Rajner. The Great Starvation: An Irish Holocaust.

| Modern Irish famines | |

|---|---|

- Articles needing cleanup from October 2007

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from October 2007

- Misplaced Pages pages needing cleanup from October 2007

- History of Ireland 1801-1922

- Famines

- Genocide

- 1845 in Ireland

- 19th century in the United Kingdom

- Land reform in Ireland

- Famines in Ireland

- Potatoes

- Economic disasters

- Irish American history

- Irish diaspora