| Revision as of 19:01, 15 December 2007 editBless sins (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers16,862 edits so now a distinguished professor is unreliable because of Str1977's OR? rv to NPOV, accurate, and OR free version. (btw I've kept the compromise)← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:24, 16 December 2007 edit undoStr1977 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers59,147 edits you are still blindly reverting, reinserting all errors, I explained my reasoning on talkNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Totally-disputed|date=December 2007}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| {{Campaignbox Rise of Islam}} | {{Campaignbox Rise of Islam}} | ||

| {| class="messagebox" style="width: auto; background: #FFF0D9;" | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |<center>'''The ] of the wording and factual accuracy of this article is ].''' <br /><small> Please see the discussion on the ].{{#if:{{{date|}}}|<br />This article or section has been tagged since {{{date}}}.}}</small><br/><small>Please do not remove this message until the ]</small> | |||

| |}<includeonly>{{#if:{{{date|}}}||}}</includeonly><noinclude> | |||

| The '''Banu Qurayza''' (] بني قريظة; بنو قريظة alternate spellings include '''Quraiza''', '''Qurayzah''', '''Quraytha''', and the archaic '''Koreiza''') were a ]ish tribe who lived in ], at the oasis of Yathrib (now known as ]). In 627 CE, the tribe was charged with treachery and collaboration with the invading armies during the ] and besieged by the Muslims commanded by ].<ref>Peterson, ''Muhammad: the prophet of God'', p. 126.</ref><ref>Ramadan, ''In the Footsteps of the Prophet'', p. 141.</ref> The Banu Qurayza surrendered and all the men, apart from a few who converted to ], were beheaded, while all the women and children were enslaved.<ref>Hodgson, ''The Venture of Islam'', vol. 1, p. 191.</ref><ref>Brown, ''A New Introduction to Islam'', p. 81.</ref> | The '''Banu Qurayza''' (] بني قريظة; بنو قريظة alternate spellings include '''Quraiza''', '''Qurayzah''', '''Quraytha''', and the archaic '''Koreiza''') were a ]ish tribe who lived in ], at the oasis of Yathrib (now known as ]). In 627 CE, the tribe was charged with treachery and collaboration with the invading armies during the ] and besieged by the Muslims commanded by ].<ref>Peterson, ''Muhammad: the prophet of God'', p. 126.</ref><ref>Ramadan, ''In the Footsteps of the Prophet'', p. 141.</ref> The Banu Qurayza surrendered and all the men, apart from a few who converted to ], were beheaded, while all the women and children were enslaved.<ref>Hodgson, ''The Venture of Islam'', vol. 1, p. 191.</ref><ref>Brown, ''A New Introduction to Islam'', p. 81.</ref> | ||

| Line 18: | Line 13: | ||

| ===Account of the king of Himyar=== | ===Account of the king of Himyar=== | ||

| Ibn Ishaq tells of a conflict between the last ]ite King of ]<ref>Muslim sources usually referred to Himyar kings by the dynastic title of "Tubba".</ref> and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to Ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two ]s from the Banu Qurayza, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place "to which a ] of the ] would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place". The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in ], they reportedly recognized ] as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king "to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honor it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts." On approaching Yemen, tells Ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle by coming out of a fire unscathed and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.<ref>Guillaume, p. 7-9; Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'' p. 49-50.</ref> | Ibn Ishaq tells of a conflict between the last ]ite King of ]<ref>Muslim sources usually referred to Himyar kings by the dynastic title of "Tubba".</ref> and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to Ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two ]s from the Banu Qurayza, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place "to which a ] of the ] would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place". The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in ], they reportedly recognized ] as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king "to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honor it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts." On approaching Yemen, tells Ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle by coming out of a fire unscathed and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.<ref>Guillaume, p. 7-9; Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'', p. 49-50.</ref> | ||

| ===Arrival of the Aws and Khazraj=== | ===Arrival of the Aws and Khazraj=== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 22: | ||

| ==Arrival of Muhammad== | ==Arrival of Muhammad== | ||

| {{main|Migration to Medina}} | {{main|Migration to Medina}} | ||

| Ibn Ishaq recorded that after ] arrived in Medina in 622, he established a compact, the ], which committed the Jewish and Muslim tribes to mutual cooperation. The nature of this document as recorded by Ibn Ishaq and transmitted by ] is the subject of dispute among modern historians, many of whom maintain that this "treaty" is possibly a collage of agreements, of different dates, and that it is not clear when they were made.<ref>Firestone, ''Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam'', p. 118, |

Ibn Ishaq recorded that after ] arrived in Medina in 622, he established a compact, the ], which committed the Jewish and Muslim tribes to mutual cooperation. The nature of this document as recorded by Ibn Ishaq and transmitted by ] is the subject of dispute among modern historians, many of whom maintain that this "treaty" is possibly a collage of agreements, of different dates, and that it is not clear when they were made.<ref>Firestone, ''Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam'', p. 118, 170. For opinions disputing the early date of the Constitution of Medina, see e.g., Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'', p. 119.</ref><ref name="Welch">Welch, "Muhammad", ''Encyclopaedia of Islam''.</ref><ref name="Kurayza"/> Watt holds that the Qurayza and Nadir were probably mentioned in an earlier version of the Constitution requiring the parties not to support an enemy against each other.<ref name="Kurayza"/> | ||

| Aside from the general agreements, the chronicles by Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi contain a report that after his arrival, Muhammad signed a special treaty with the Qurayza chief ]. Ibn Ishaq gives no sources, while al-Waqidi refers to Ka’b ibn Malik of Salima, a clan hostile to the Jews, and Mummad ibn Ka’b, the son of a Qurayza boy who was sold into slavery in the aftermath of the siege and subsequently became a Muslim. The sources are suspect of being against the Qurayza and therefore the historicity of this agreement between Muhammad and the Banu Qurayza is open to grave doubt. Among modern historians, R. B. Serjeant supports the historicity of this document.<ref name="serjeant">Serjeant, p. 36.</ref> On the other hand, ] argues that the Muslim historians had invented this agreement in order to justify the subsequent treatment of the Qurayza.<ref name="Stillman14-16">Stillman, p. 14-16.</ref> Watt also rejects the existence of such a special agreement |

Aside from the general agreements, the chronicles by Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi contain a report that after his arrival, Muhammad signed a special treaty with the Qurayza chief ]. Ibn Ishaq gives no sources, while al-Waqidi refers to Ka’b ibn Malik of Salima, a clan hostile to the Jews, and Mummad ibn Ka’b, the son of a Qurayza boy who was sold into slavery in the aftermath of the siege and subsequently became a Muslim. The sources are suspect of being against the Qurayza and therefore the historicity of this agreement between Muhammad and the Banu Qurayza is open to grave doubt. Among modern historians, R. B. Serjeant supports the historicity of this document.<ref name="serjeant">Serjeant, p. 36.</ref> On the other hand, ] argues that the Muslim historians had invented this agreement in order to justify the subsequent treatment of the Qurayza.<ref name="Stillman14-16">Stillman, p. 14-16.</ref> Watt also rejects the existence of such a special agreement but notes that the Jews were bound by the aforementioned general agreement and by their alliance to the two Arab tribes not to support an enemy against Muhammad.<ref name="Kurayza"/> | ||

| During the first few months after arrival |

During the first few months after Muhammad's arrival in Medina, the Banu Qurayza were involved in a dispute with the Banu Nadir: The more powerful Nadir rigorously applied ] against the Qurayza, while not allowing it being enforced against themselves. Further, the ] paid for killing a man of the Qurayza was only half of the blood-money required for killing a man of the Nadir<ref>M. H. Ananikian, "Tahrif or the alteration of the bible according to the Moslems", p. 63-64.</ref>, placing the Qurayza in a socially inferior position. The Qurayza called on Muhammad as arbitrator, who delivered the surah {{cite quran|5|42-45|expand=no|style=nosup}} and judged that the Nadir and Qurayza should be treated alike in the application of lex talionis and raised the assessment of the Qurayza to the full amount of blood money.<ref>Guillaume, p. 267-268.</ref><ref name="serjeant">Serjeant, p. 36</ref><ref name= Nomani/> | ||

| Tensions quickly mounted between the Muslim and Jewish communities, while Muhammad found himself in the state of warfare with his native Meccan tribe of the Quraysh. In 624, after his victory over the Meccans in the ], Muhammad expelled the Banu Qaynuqa from Medina. The Qurayza remained passive during the whole Qaynuqa affair, apparently because the Qaynuqa were historically allied with the Khazraj, while the Qurayza were the allies of the Aws.<ref>See e.g. Stillman, p. 13.</ref> | Tensions quickly mounted between the Muslim and Jewish communities, while Muhammad found himself in the state of warfare with his native Meccan tribe of the Quraysh. In 624, after his victory over the Meccans in the ], Muhammad expelled the Banu Qaynuqa from Medina. The Qurayza remained passive during the whole Qaynuqa affair, apparently because the Qaynuqa were historically allied with the Khazraj, while the Qurayza were the allies of the Aws.<ref>See e.g. Stillman, p. 13.</ref> | ||

| Line 39: | Line 34: | ||

| ==Battle of the Trench== | ==Battle of the Trench== | ||

| {{Main|Battle of the Trench}} | {{Main|Battle of the Trench}} | ||

| In 627, a Quraysh-led army under the command of ], together with contingents from the ] tribe of ] and the exiled Banu Nadir, marched against Medina - the Muslim stronghold - and laid siege to it. According to Al-Waqidi, the Banu Qurayza helped the defense effort of Medina by supplying spades, picks, and baskets for the excavation of the defensive trench.<ref name="Stillman14-16"/> |

In 627, a Quraysh-led army under the command of ], together with contingents from the ] tribe of ] and the exiled Banu Nadir, marched against Medina - the Muslim stronghold - and laid siege to it. According to Al-Waqidi, the Banu Qurayza helped the defense effort of Medina by supplying spades, picks, and baskets for the excavation of the defensive trench.<ref name="Stillman14-16"/> They also possessed large numbers of weaponry, as upon their surrender 1,500 ]s, 2,000 lances, 300 suits of armor, and 500 shields were later seized by the Muslims.<ref name="Heck">Heck, "Arabia Without Spices: An Alternate Hypothesis", p. 547-5.</ref> It is unclear whether or not their treaty with Muhammad, obliged the Qurayza help him defend Medina or merely to remain neutral. According to Watt, the Banu Qurayza "seem to have tried to remain neutral" in the battle.<ref>Watt, ''Muhammad at Medina'', p. 36.</ref> and though they did not commit any act overtly hostile to Muhammad<ref name="Kurayza"/>, there are reports about their negotiations with the besiegers<ref>Watt, ''Muhammad at Medina,'' p. 38.</ref>: | ||

| Ibn Ishaq writes that during the siege ], the chief of the exiled Banu Nadir and the instigator of the alliance with the Quraysh and the Ghatafan<ref name= Nomani>Nomani, p. 382.</ref>, came to the Qurayza, was welcomed by their chief Ka'b ibn Asad and persuaded him to help the Meccans conquer Medina. Ka'b was, according to Al-Waqidi's account, initially reluctant to break the contract and argued that Muhammad never broke any contract with them or exposed them to any shame, but decided to support the Meccans after Huyayy had promised to join the Qurayza in Medina if the besieging army would return to Mecca without having killed Muhammad.<ref>Guillaume, p. 453.</ref> ] and al-Waqidi report that Huyayy tore into pieces the agreement between Ka'b and Muhammad.<ref name="Kurayza"/><ref>See also above for the critical view on the historicity of this treaty.</ref> | |||

| Watt writes that Muhammad "became anxious about their conduct and sent some of the leading Muslims to talk to them; the result was disquieting."<ref name="Kurayza"/> According to Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad ordered a man from the Ghatafan who had secretly converted to Islam to go to Muhammad's enemies and sow discord among them. The man went to the Banu Qurayza and advised them to join the hostilities against Muhammad only if the besiegers provide ]s from among their chiefs. When the representatives of the Quraysh and the Ghatafan came to the Qurayza, asking for support in the planned decisive battle with Muhammad, the Qurayza indeed demanded hostages. The representatives of the besiegers refused, breaking down negotiations<ref>Guillaume, p. 458-459.</ref> and resulting in the Banu Qurayza becoming extremely distrustful of the besieging army.<ref>Peterson |

Watt writes that Muhammad "became anxious about their conduct and sent some of the leading Muslims to talk to them; the result was disquieting."<ref name="Kurayza"/> According to Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad ordered a man from the Ghatafan who had secretly converted to Islam to go to Muhammad's enemies and sow discord among them. The man went to the Banu Qurayza and advised them to join the hostilities against Muhammad only if the besiegers provide ]s from among their chiefs. When the representatives of the Quraysh and the Ghatafan came to the Qurayza, asking for support in the planned decisive battle with Muhammad, the Qurayza indeed demanded hostages. The representatives of the besiegers refused, breaking down negotiations<ref>Guillaume, p. 458-459.</ref> and resulting in the Banu Qurayza becoming extremely distrustful of the besieging army.<ref name="Peterson125">Peterson, ''Muhammad: the prophet of God'', p. 125.</ref> The Qurayza did not take any actions to support them until Abu Sufyan's forces retreated.<ref name="Stillman14-16"/> | ||

| {{wikisource}} | {{wikisource}} | ||

| ==Siege and |

==Siege and massacre== | ||

| On the day of the Meccans' withdrawal, Muhammad led his forces against the Banu Qurayza neighborhood. According to the Muslim tradition, he had been ordered to do so by the ] ]. The Banu Qurayza retreated into their stronghold |

On the day of the Meccans' withdrawal, Muhammad led his forces against the Banu Qurayza neighborhood. According to the Muslim tradition, he had been ordered to do so by the ] ]. The Banu Qurayza retreated into their stronghold and endured the siege for 25 days. As their morale waned, Ka'b ibn Asad suggested three alternative ways out of their predicament: embrace Islam, kill their own children and women, then rush out for a charge to either win or die; or make a surprise attack on the ]. The Banu Qurayza accepted none of these alternatives and instead asked to confer with ], one of their allies from the Aws. According to Ibn Ishaq, Abu Lubaba felt pity for the women and children of the tribe who were crying and when asked whether the Qurayza should surrender to Muhammad, advised them to do so. However he also "made a sign with his hand toward his throat, indicating that would be slaughter".<ref>Guillaume, p. 461-463; Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'', p. 222-223; Stillman, p. 137-140.</ref> | ||

| The next morning, the Banu Qurayza unconditionally surrendered and the Muslims seized their stronghold and their weapons. Some among the tribe of Aws wanted to honor their old alliance with Qurayza and asked Muhammad to treat the Qurayza leniently as he had previously treated the Qaynuqa for the sake of ]. (Arab custom required support of an ally, independent of the ally's conduct to a third party.)<ref name="WattProphetStatesman">Watt, ''Muhammad, Prophet and Statesman'', p. 171-174.</ref> Muhammad then suggested that one of the Aws would be an arbitrator, and when they agreed, he appointed ], a leading man among the Aws who was dying from a wound suffered during the siege of the Qurayza, to decide the fate of the Jewish tribe. The Banu Qurayza also agreed with the appointment of Sa'ad ibn Mua'dh.<ref>{{ |

The next morning, the Banu Qurayza unconditionally surrendered and the Muslims seized their stronghold and their weapons. Some among the tribe of Aws wanted to honor their old alliance with Qurayza and asked Muhammad to treat the Qurayza leniently as he had previously treated the Qaynuqa for the sake of ]. (Arab custom required support of an ally, independent of the ally's conduct to a third party.)<ref name="WattProphetStatesman">Watt, ''Muhammad, Prophet and Statesman'', p. 171-174.</ref> Muhammad then suggested that one of the Aws would be an arbitrator, and when they agreed, he appointed ], a leading man among the Aws who was dying from a wound suffered during the siege of the Qurayza, to decide the fate of the Jewish tribe.<ref name="Guillaume463"/> The Banu Qurayza reportedly also agreed with the appointment of Sa'ad ibn Mua'dh.<ref>Hashmi, Buchanan & Moore, ''States, Nations, and Borders: The Ethics of Making Boundaries''.</ref>{{Fact|date=December 2007}} Sa'd ibn Mua'dh pronounced that "the men should be killed, the property divided, and the women and children taken as captives". Muhammad approved of the ruling, calling it similar to God's judgment.<ref name="Guillaume463">Guillaume, p. 463-464; Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'', p. 223-224; Stillman, p. 140-141; Adil, p. 395-396.</ref> | ||

| | author = Mohammed Abu-Nimer | |||

| | title = A Framework for Nonviolence and Peacebuilding in Islam | |||

| | journal = Journal of Law and Religion | |||

| | volume = 15 | |||

| | issue = 1-2 | |||

| | pages = 247 | |||

| | date= 2000-2001 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Hashmi | |||

| | first = Sohail H. | |||

| | coauthors = Buchanan, Allen E; Moore, Margaret | |||

| ⚫ | |

||

| | publisher = Cambridge University Press | |||

| | date= 2003 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Khadduri | |||

| | first = Majid | |||

| | title = War And Peace in the Law of Islam | |||

| | location = Baltimore | |||

| | publisher = Johns Hopkins Press | |||

| | date= 1955 | |||

| }}</ref>Sa'd ibn Mua'dh pronounced that "the men should be killed, the property divided, and the women and children taken as captives". Muhammad approved of the ruling, calling it similar to God's judgment.<ref>Guillaume, p. 463-464; Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'', p. 223-224; Stillman, p. 140-141; Adil, ''Muhammad: The Messenger of Islam'', p. 395-396.</ref> Daniel C. Peterson, Martin Lings and Caesar Farah state that this judgment was in accordance with the Jewish law as stated in Deut. 20:10-14.<ref name =Peterson/><ref>Lings, p. 232</ref><ref name = Caesar>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Caesar | |||

| | first = Farah | |||

| | title = Islam: Beliefs and Observances | |||

| | publisher = Barron's Educational Series | |||

| | date= 2003 | |||

| | pages = 52 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| According to Stillman, Muhammad chose ] so as not to pronounce the judgment himself after the precedents he had set with the Banu Qaynuqa and the Banu Nadir: "Sa`d took the hint and condemned the adult males to death and the hapless women and children to slavery." Furthermore, Stillman infers from Abu Lubaba's gesture that Muhammad had decided the fate of the Qurayza even before their surrender.<ref name="Stillman14-16"/ |

According to Stillman, Muhammad chose ] so as not to pronounce the judgment himself after the precedents he had set with the Banu Qaynuqa and the Banu Nadir: "Sa`d took the hint and condemned the adult males to death and the hapless women and children to slavery." Furthermore, Stillman infers from Abu Lubaba's gesture that Muhammad had decided the fate of the Qurayza even before their surrender.<ref name="Stillman14-16"/> | ||

| Sa'd dismissed the pleas of the Aws, according to Watt, because being close to death and concerned with his afterlife, he put what he considered "his duty to God and the "]" before tribal allegiance.<ref name="WattProphetStatesman">Watt, ''Muhammmad: The prophet and Statesman'', p. 171-174.</ref> Tariq Ramadan argues that Muhammad deviated from his earlier, more lenient treatment of prisoners as this was seen as "as sign of weakness if not madness".<ref>Ramadan, p. 145.</ref> and Peterson concurs that the Muslims wanted to deterr future treachery by severe punishment.<ref name="Peterson127"/> | |||

| Ibn Ishaq describes the killing of the Banu Qurayza men as follows: | Ibn Ishaq describes the killing of the Banu Qurayza men as follows: | ||

| {{cquote|Then they surrendered, and the apostle confined them in Medina in the quarter of d. al-Harith, a woman of B. al-Najjar. Then the apostle went out to the market of Medina (which is still its market today) and dug trenches in it. Then he sent for them and struck off their heads in those trenches as they were brought out to him in batches. Among them was the enemy of Allah Huyayy b. Akhtab and Ka`b b. Asad their chief. There were 600 or 700 in all, though some put the figure as high as 800 or 900. As they were being taken out in batches to the apostle they asked Ka`b what he thought would be done with them. He replied, 'Will you never understand? Don't you see that the summoner never stops and those who are taken away do not return? By Allah it is death!' This went on until the apostle made an end of them. Huyayy was brought out wearing a flowered robe in which he had made holes about the size of the finger-tips in every part so that it should not be taken from him as spoil, with his hands bound to his neck by a rope. When he saw the apostle he said, 'By God, I do not blame myself for opposing you, but he who forsakes God will be forsaken.' Then he went to the men and said, 'God's command is right. A book and a decree, and massacre have been written against the Sons of Israel.' Then he sat down and his head was struck off.<ref>Guillaume, p. 464; Stillman, p. 141-142; partially cited in Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'' p. 224.</ref>}} | {{cquote|Then they surrendered, and the apostle confined them in Medina in the quarter of d. al-Harith, a woman of B. al-Najjar. Then the apostle went out to the market of Medina (which is still its market today) and dug trenches in it. Then he sent for them and struck off their heads in those trenches as they were brought out to him in batches. Among them was the enemy of Allah Huyayy b. Akhtab and Ka`b b. Asad their chief. There were 600 or 700 in all, though some put the figure as high as 800 or 900. As they were being taken out in batches to the apostle they asked Ka`b what he thought would be done with them. He replied, 'Will you never understand? Don't you see that the summoner never stops and those who are taken away do not return? By Allah it is death!' This went on until the apostle made an end of them. Huyayy was brought out wearing a flowered robe in which he had made holes about the size of the finger-tips in every part so that it should not be taken from him as spoil, with his hands bound to his neck by a rope. When he saw the apostle he said, 'By God, I do not blame myself for opposing you, but he who forsakes God will be forsaken.' Then he went to the men and said, 'God's command is right. A book and a decree, and massacre have been written against the Sons of Israel.' Then he sat down and his head was struck off.<ref>Guillaume, p. 464; Stillman, p. 141-142; partially cited in Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'', p. 224.</ref>}} | ||

| It is also reported, that alongside all the men, one woman who had thrown a millstone from the battlements during the siege and killed one of the Muslim besiegers, was put to death.<ref>William Muir, ''A Life of Mahomet and History of Islam to the Era of the Hegira'', |

It is also reported, that alongside all the men, one woman who had thrown a millstone from the battlements during the siege and killed one of the Muslim besiegers, was put to death.<ref>William Muir, ''A Life of Mahomet and History of Islam to the Era of the Hegira'', . Muir follows Hishami and also refers to Aisha, who had related: "But I shall never cease to marvel at her good humour and laughter, although she knew that she was to die." ().</ref> ] writes in his '']'' that Banu Kilab, a clan of Arab clients of the Banu Qurayza, were killed alongside the Jewish tribe.<ref>Lecker, "On Arabs of the Banū Kilāb executed together with the Jewish Banū Qurayza", p. 69.</ref> | ||

| Three boys of the clan of Hadl, who had been with Qurayza in the strongholds, slipped out before the surrender and converted to Islam. The son of one of them, Muhammad ibn Ka'b al-Qurazi, gained distinction as a scholar. One or two other men also escaped. The spoils of battle, including the enslaved women and children of the tribe, were divided up among Muhammad's followers |

Three boys of the clan of Hadl, who had been with Qurayza in the strongholds, slipped out before the surrender and converted to Islam. The son of one of them, Muhammad ibn Ka'b al-Qurazi, gained distinction as a scholar. One or two other men also escaped. The spoils of battle, including the enslaved women and children of the tribe, were divided up among Muhammad's followers, with Muhammad himself taking a ], as was customary among Muslims. As part of his share of the booty, Muhammad selected one of the women, Rayhana, and took her as ].<ref>Rodinson, ''Muhammad: Prophet of Islam'', p. 213.</ref> She is said to have later become a Muslim.<ref name="Kurayza"/> and Muhammad offered to free and marry her. According to some sources she accepted his proposal, while according to others she rejected it.<ref>Ramadan, p. 146.</ref> | ||

| Some of the women and children of the Banu Qurayza were bought and sold by Jews,<ref>Watt, ''Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman'', p. 175.</ref> in particular the Banu Nadir |

Some of the women and children of the Banu Qurayza were bought and sold by Jews,<ref>Watt, ''Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman'', p. 175.</ref> in particular the Banu Nadir. Peterson argues that this is because the Nadir felt responsible for the Quarayza due to the role of ] in the events.<ref name="Peterson127">Peterson, p. 127.</ref> | ||

| The Qur'an briefly refers to the incident in Surah | |||

| {{cite quran|33|26|expand=no|style=nosup}}<ref name="Arafat"/> and medieval{{dubious}} Muslim jurists have looked upon Surah {{cite quran|8|55-58|expand=no|style=nosup}} as a justification of the treatment of the Banu Qurayza, arguing that the Qurayza broke the pact with Muhammad, and thus Muhammad was justified in repudiating his side of the pact and declaring war on the Qurayza.<ref>Peters, ''Muhammad and the Origins of Islam'', p. 224.</ref>Arab Muslim theologians and historians have either viewed the incident as "the punishment of the Medina Jews, who were invited to convert and refused, perfectly exemplify the Quran's tales of what happened to those who rejected the prophets of old" or offered a political explanation.<ref>Peters, ''Islam. A Guide for Jews and Christians'', p. 77.</ref> | |||

| Walid N. Arafat and ] have disputed that the Banu Qurayza were killed on a large scale.<ref name="Meri1">Meri, p. 754.</ref> Ahmad argues that only the leaders of the tribe were killed.<ref> |

Walid N. Arafat and ] have disputed that the Banu Qurayza were killed on a large scale.<ref name="Meri1">Meri, ''Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia'', p. 754.</ref> Ahmad argues that only the leaders of the tribe were killed.<ref>Ahmad, ''Muhammad and the Jews: A Re-examination''.</ref><ref>Nemoy, "Barakat Ahmad's "Muhammad and the Jews"", p. 325. Nemoy is sourcing Ahmed's ''Muhammad and the Jews''.</ref> Arafat argued that ] gathered information from descendants of the Qurayza Jews, who embellished or manufactured the details of the incident. <ref name="Arafat">Arafat, "New Light on the Story of Banu Qurayza and the Jews of Medina", p. 100-107. Arafat relates the testimony of ], who denounced this and other accounts as "odd tales" and quoted ], a contempory of Ibn Ishaq, whom he rejected as a "liar", an "impostor" and for seeking out the Jewish descendants for gathering information about Muhammad's campaign with their forefathers.</ref> Watt finds Arafat's arguments "not entirely convincing."<ref name="Kurayza"/> | ||

| ==References in literature== | ==References in literature== | ||

| Line 118: | Line 85: | ||

| *'']'' (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. ]. Keter Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 965-07-0665-8 | *'']'' (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. ]. Keter Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 965-07-0665-8 | ||

| ===Jewish tribes |

===Jewish tribes=== | ||

| *Arafat, Walid N., "", in: '']'' 1976, p. 100-107. | *Arafat, Walid N., "", in: '']'' 1976, p. 100-107. | ||

| Line 128: | Line 95: | ||

| ====Further reading==== | ====Further reading==== | ||

| *]. ''The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians under Islam''. London: Associated University Presses, 1985. | |||

| *Lecker, Michael. ''Jews and Arabs in Pre- And Early Islamic Arabia''. Ashgate Publishing, 1999. | *Lecker, Michael. ''Jews and Arabs in Pre- And Early Islamic Arabia''. Ashgate Publishing, 1999. | ||

| *Newby, Gordon Darnell. ''A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam'' (Studies in Comparative Religion). University of South Carolina Press, 1988. | *Newby, Gordon Darnell. ''A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam'' (Studies in Comparative Religion). University of South Carolina Press, 1988. | ||

| Line 134: | Line 102: | ||

| *Adil, Hajjah Amina, ''Muhammad: The Messenger of Islam''. Islamic Supreme Council of America, 2002, p. 395-396 | *Adil, Hajjah Amina, ''Muhammad: The Messenger of Islam''. Islamic Supreme Council of America, 2002, p. 395-396 | ||

| *Ananikian, M. H., "Tahrif or the alteration of the bible according to the Moslems." ''The Muslim World'' Volume 14, Issue 1 (January 1924), p. 63-64. | |||

| *Brown, Daniel W., ''A New Introduction to Islam''. Blackwell Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0631216049 | *Brown, Daniel W., ''A New Introduction to Islam''. Blackwell Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0631216049 | ||

| *Firestone, Reuven, ''Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam''. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-512580-0 | *Firestone, Reuven, ''Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam''. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-512580-0 | ||

| *Guillaume, Alfred, ''The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah''. Oxford University Press, 1955. ISBN 0-1963-6033-1 | *Guillaume, Alfred, ''The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah''. Oxford University Press, 1955. ISBN 0-1963-6033-1 | ||

| ⚫ | *Hashmi, Sohail H., Buchanan, Allen E. & Moore, Margaret, ''States, Nations, and Borders: The Ethics of Making Boundaries''. Cambridge University Press, 2003. | ||

| *Hawting, Gerald R. & Shareef, Abdul-Kader A., ''Approaches to the Qur'an''. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415057558 | *Hawting, Gerald R. & Shareef, Abdul-Kader A., ''Approaches to the Qur'an''. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415057558 | ||

| *Heck, Gene W., "Arabia Without Spices: An Alternate Hypothesis", in: ''Journal Of The American Oriental Society'' 123 (2003), p. 547-567. | *Heck, Gene W., "Arabia Without Spices: An Alternate Hypothesis", in: ''Journal Of The American Oriental Society'' 123 (2003), p. 547-567. | ||

| Line 153: | Line 123: | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| *Relevant chapters of , by al-Mubarakpuri | *Relevant chapters of , by al-Mubarakpuri | ||

| ** | ** | ||

| Line 158: | Line 129: | ||

| {{Judaismfooter}} | {{Judaismfooter}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 16:24, 16 December 2007

| Campaigns of Muhammad | |

|---|---|

| Further information: Military career of Muhammad |

The Banu Qurayza (Arabic بني قريظة; بنو قريظة alternate spellings include Quraiza, Qurayzah, Quraytha, and the archaic Koreiza) were a Jewish tribe who lived in northern Arabia until the 7th century, at the oasis of Yathrib (now known as Medina). In 627 CE, the tribe was charged with treachery and collaboration with the invading armies during the Battle of the Trench and besieged by the Muslims commanded by Muhammad. The Banu Qurayza surrendered and all the men, apart from a few who converted to Islam, were beheaded, while all the women and children were enslaved.

History in pre-Islamic Arabia

Early history

Extant sources provide no conclusive evidence whether the Banu Qurayza were ethnically Jewish or Arab converts to Judaism. Just like the other Jews of Yathrib, the Qurayza claimed to be of Israelite descent and observed the commandments of Judaism, but adopted many Arab customs and intermarried with Arabs. They were dubbed priestly tribe (kahinan in Arabic from the Hebrew kohanim - Ibn Ishaq, the author of the traditional Muslim biography of Muhammad, traces their genealogy to Aaron and further to Abraham but gives only eight intermediaries between Aaron and the purported founder of the Qurayza tribe.

In the 5th century CE, the Qurayza lived in Yathrib together with two other major Jewish tribes: Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Nadir. Al-Isfahani writes in his 9th-century collection of Arabic poetry Kitab al-Aghani that Jews arrived in Hijaz in the wake of the Jewish-Roman wars; the Qurayza settled in Mahzur, a wadi in Al Harrah. The 15th century Muslim scholar Al-Samhudi lists a dozen of other Jewish clans living in the town of which the most important one was Banu Hadl, closely aligned with the Banu Qurayza. The Jews introduced agriculture to Yathrib, growing date palms and cereals, and this cultural and economic advantage enabled the Jews to dominate the local Arabs politically. Al-Waqidi wrote that the Banu Qurayza were people of high lineage and of properties, "whereas we were but an Arab tribe who did not possess any palm trees nor vineyards, being people of only sheep and camels." Ibn Khordadbeh later reported that during the Persian domination in Hijaz, the Banu Qurayza served as tax collectors for the shah.

Account of the king of Himyar

Ibn Ishaq tells of a conflict between the last Yemenite King of Himyar and the residents of Yathrib. When the king was passing by the oasis, the residents killed his son, and the Yemenite ruler threatened to exterminate the people and cut down the palms. According to Ibn Ishaq, he was stopped from doing so by two rabbis from the Banu Qurayza, who implored the king to spare the oasis because it was the place "to which a prophet of the Quraysh would migrate in time to come, and it would be his home and resting-place". The Yemenite king thus did not destroy the town and converted to Judaism. He took the rabbis with him, and in Mecca, they reportedly recognized Kaaba as a temple built by Abraham and advised the king "to do what the people of Mecca did: to circumambulate the temple, to venerate and honor it, to shave his head and to behave with all humility until he had left its precincts." On approaching Yemen, tells Ibn Ishaq, the rabbis demonstrated to the local people a miracle by coming out of a fire unscathed and the Yemenites accepted Judaism.

Arrival of the Aws and Khazraj

The situation changed after two Arab tribes named Banu Aws and Banu Khazraj arrived to Yathrib from Yemen. At first, these tribes were clients of the Jews, but toward the end of the fifth century CE, they revolted and became independent. Most modern historians accept the claim of the Muslim sources that after the revolt, the Jewish tribes became clients of the Aws and the Khazraj. William Montgomery Watt however considers this clientship to be unhistorical prior to 627 and maintains that the Jews retained a measure of political independence after the Arab revolt.

Eventually, the Aws and the Khazraj became hostile to each other. They had been fighting possibly for around a hundred years before 620 and at least since 570s. The Banu Nadir and the Banu Qurayza were allied with the Aws, while the Banu Qaynuqa sided with the Khazraj. There are reports of the constant conflict between Banu Qurayza and Banu Nadir, the two allies of Aws, yet the sources often refer to these two tribes as “brothers”. Aws and Khazraj and their Jewish allies fought a total of four wars. The last and bloodiest altercation was the Battle of Bu'ath, the outcome of which was inconclusive. The continuing feud was probably the chief cause for the invitation of Muhammad to Yathrib in order to adjudicate in disputed cases.

Arrival of Muhammad

Main article: Migration to MedinaIbn Ishaq recorded that after Muhammad arrived in Medina in 622, he established a compact, the Constitution of Medina, which committed the Jewish and Muslim tribes to mutual cooperation. The nature of this document as recorded by Ibn Ishaq and transmitted by Ibn Hisham is the subject of dispute among modern historians, many of whom maintain that this "treaty" is possibly a collage of agreements, of different dates, and that it is not clear when they were made. Watt holds that the Qurayza and Nadir were probably mentioned in an earlier version of the Constitution requiring the parties not to support an enemy against each other.

Aside from the general agreements, the chronicles by Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi contain a report that after his arrival, Muhammad signed a special treaty with the Qurayza chief Ka'b ibn Asad. Ibn Ishaq gives no sources, while al-Waqidi refers to Ka’b ibn Malik of Salima, a clan hostile to the Jews, and Mummad ibn Ka’b, the son of a Qurayza boy who was sold into slavery in the aftermath of the siege and subsequently became a Muslim. The sources are suspect of being against the Qurayza and therefore the historicity of this agreement between Muhammad and the Banu Qurayza is open to grave doubt. Among modern historians, R. B. Serjeant supports the historicity of this document. On the other hand, Norman Stillman argues that the Muslim historians had invented this agreement in order to justify the subsequent treatment of the Qurayza. Watt also rejects the existence of such a special agreement but notes that the Jews were bound by the aforementioned general agreement and by their alliance to the two Arab tribes not to support an enemy against Muhammad.

During the first few months after Muhammad's arrival in Medina, the Banu Qurayza were involved in a dispute with the Banu Nadir: The more powerful Nadir rigorously applied Lex talionis against the Qurayza, while not allowing it being enforced against themselves. Further, the blood money paid for killing a man of the Qurayza was only half of the blood-money required for killing a man of the Nadir, placing the Qurayza in a socially inferior position. The Qurayza called on Muhammad as arbitrator, who delivered the surah 5:42-45 and judged that the Nadir and Qurayza should be treated alike in the application of lex talionis and raised the assessment of the Qurayza to the full amount of blood money.

Tensions quickly mounted between the Muslim and Jewish communities, while Muhammad found himself in the state of warfare with his native Meccan tribe of the Quraysh. In 624, after his victory over the Meccans in the Battle of Badr, Muhammad expelled the Banu Qaynuqa from Medina. The Qurayza remained passive during the whole Qaynuqa affair, apparently because the Qaynuqa were historically allied with the Khazraj, while the Qurayza were the allies of the Aws.

Soon afterwards, Muhammad came into conflict with the Banu Nadir. He had one of the Banu Nadir's chiefs, the poet Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, assassinated and after the Battle of Uhud accused the tribe of treachery and plotting against his life and expelled them from the city. The Qurayza remained passive during this conflict, according to R. B. Serjeant, because of the blood money issue related above.

Battle of the Trench

Main article: Battle of the TrenchIn 627, a Quraysh-led army under the command of Abu Sufyan, together with contingents from the Bedouin tribe of Ghatafan and the exiled Banu Nadir, marched against Medina - the Muslim stronghold - and laid siege to it. According to Al-Waqidi, the Banu Qurayza helped the defense effort of Medina by supplying spades, picks, and baskets for the excavation of the defensive trench. They also possessed large numbers of weaponry, as upon their surrender 1,500 swords, 2,000 lances, 300 suits of armor, and 500 shields were later seized by the Muslims. It is unclear whether or not their treaty with Muhammad, obliged the Qurayza help him defend Medina or merely to remain neutral. According to Watt, the Banu Qurayza "seem to have tried to remain neutral" in the battle. and though they did not commit any act overtly hostile to Muhammad, there are reports about their negotiations with the besiegers:

Ibn Ishaq writes that during the siege Huyayy ibn Akhtab, the chief of the exiled Banu Nadir and the instigator of the alliance with the Quraysh and the Ghatafan, came to the Qurayza, was welcomed by their chief Ka'b ibn Asad and persuaded him to help the Meccans conquer Medina. Ka'b was, according to Al-Waqidi's account, initially reluctant to break the contract and argued that Muhammad never broke any contract with them or exposed them to any shame, but decided to support the Meccans after Huyayy had promised to join the Qurayza in Medina if the besieging army would return to Mecca without having killed Muhammad. Ibn Kathir and al-Waqidi report that Huyayy tore into pieces the agreement between Ka'b and Muhammad.

Watt writes that Muhammad "became anxious about their conduct and sent some of the leading Muslims to talk to them; the result was disquieting." According to Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad ordered a man from the Ghatafan who had secretly converted to Islam to go to Muhammad's enemies and sow discord among them. The man went to the Banu Qurayza and advised them to join the hostilities against Muhammad only if the besiegers provide hostages from among their chiefs. When the representatives of the Quraysh and the Ghatafan came to the Qurayza, asking for support in the planned decisive battle with Muhammad, the Qurayza indeed demanded hostages. The representatives of the besiegers refused, breaking down negotiations and resulting in the Banu Qurayza becoming extremely distrustful of the besieging army. The Qurayza did not take any actions to support them until Abu Sufyan's forces retreated.

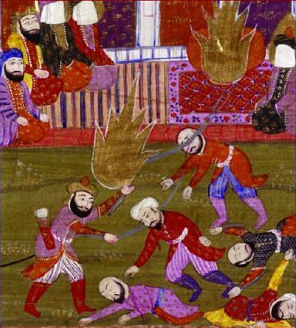

Siege and massacre

On the day of the Meccans' withdrawal, Muhammad led his forces against the Banu Qurayza neighborhood. According to the Muslim tradition, he had been ordered to do so by the angel Gabriel. The Banu Qurayza retreated into their stronghold and endured the siege for 25 days. As their morale waned, Ka'b ibn Asad suggested three alternative ways out of their predicament: embrace Islam, kill their own children and women, then rush out for a charge to either win or die; or make a surprise attack on the Sabbath. The Banu Qurayza accepted none of these alternatives and instead asked to confer with Abu Luhaba ibn Abd al-Mundhir, one of their allies from the Aws. According to Ibn Ishaq, Abu Lubaba felt pity for the women and children of the tribe who were crying and when asked whether the Qurayza should surrender to Muhammad, advised them to do so. However he also "made a sign with his hand toward his throat, indicating that would be slaughter".

The next morning, the Banu Qurayza unconditionally surrendered and the Muslims seized their stronghold and their weapons. Some among the tribe of Aws wanted to honor their old alliance with Qurayza and asked Muhammad to treat the Qurayza leniently as he had previously treated the Qaynuqa for the sake of Ibn Ubayy. (Arab custom required support of an ally, independent of the ally's conduct to a third party.) Muhammad then suggested that one of the Aws would be an arbitrator, and when they agreed, he appointed Sa'd ibn Mua'dh, a leading man among the Aws who was dying from a wound suffered during the siege of the Qurayza, to decide the fate of the Jewish tribe. The Banu Qurayza reportedly also agreed with the appointment of Sa'ad ibn Mua'dh. Sa'd ibn Mua'dh pronounced that "the men should be killed, the property divided, and the women and children taken as captives". Muhammad approved of the ruling, calling it similar to God's judgment.

According to Stillman, Muhammad chose Sa'd ibn Mua'dh so as not to pronounce the judgment himself after the precedents he had set with the Banu Qaynuqa and the Banu Nadir: "Sa`d took the hint and condemned the adult males to death and the hapless women and children to slavery." Furthermore, Stillman infers from Abu Lubaba's gesture that Muhammad had decided the fate of the Qurayza even before their surrender.

Sa'd dismissed the pleas of the Aws, according to Watt, because being close to death and concerned with his afterlife, he put what he considered "his duty to God and the "Muslim community" before tribal allegiance. Tariq Ramadan argues that Muhammad deviated from his earlier, more lenient treatment of prisoners as this was seen as "as sign of weakness if not madness". and Peterson concurs that the Muslims wanted to deterr future treachery by severe punishment.

Ibn Ishaq describes the killing of the Banu Qurayza men as follows:

Then they surrendered, and the apostle confined them in Medina in the quarter of d. al-Harith, a woman of B. al-Najjar. Then the apostle went out to the market of Medina (which is still its market today) and dug trenches in it. Then he sent for them and struck off their heads in those trenches as they were brought out to him in batches. Among them was the enemy of Allah Huyayy b. Akhtab and Ka`b b. Asad their chief. There were 600 or 700 in all, though some put the figure as high as 800 or 900. As they were being taken out in batches to the apostle they asked Ka`b what he thought would be done with them. He replied, 'Will you never understand? Don't you see that the summoner never stops and those who are taken away do not return? By Allah it is death!' This went on until the apostle made an end of them. Huyayy was brought out wearing a flowered robe in which he had made holes about the size of the finger-tips in every part so that it should not be taken from him as spoil, with his hands bound to his neck by a rope. When he saw the apostle he said, 'By God, I do not blame myself for opposing you, but he who forsakes God will be forsaken.' Then he went to the men and said, 'God's command is right. A book and a decree, and massacre have been written against the Sons of Israel.' Then he sat down and his head was struck off.

It is also reported, that alongside all the men, one woman who had thrown a millstone from the battlements during the siege and killed one of the Muslim besiegers, was put to death. Ibn Asakir writes in his History of Damascus that Banu Kilab, a clan of Arab clients of the Banu Qurayza, were killed alongside the Jewish tribe.

Three boys of the clan of Hadl, who had been with Qurayza in the strongholds, slipped out before the surrender and converted to Islam. The son of one of them, Muhammad ibn Ka'b al-Qurazi, gained distinction as a scholar. One or two other men also escaped. The spoils of battle, including the enslaved women and children of the tribe, were divided up among Muhammad's followers, with Muhammad himself taking a fifth of the value, as was customary among Muslims. As part of his share of the booty, Muhammad selected one of the women, Rayhana, and took her as part of his captives. She is said to have later become a Muslim. and Muhammad offered to free and marry her. According to some sources she accepted his proposal, while according to others she rejected it.

Some of the women and children of the Banu Qurayza were bought and sold by Jews, in particular the Banu Nadir. Peterson argues that this is because the Nadir felt responsible for the Quarayza due to the role of their chieftain in the events.

The Qur'an briefly refers to the incident in Surah 33:26 and medieval Muslim jurists have looked upon Surah 8:55-58 as a justification of the treatment of the Banu Qurayza, arguing that the Qurayza broke the pact with Muhammad, and thus Muhammad was justified in repudiating his side of the pact and declaring war on the Qurayza.Arab Muslim theologians and historians have either viewed the incident as "the punishment of the Medina Jews, who were invited to convert and refused, perfectly exemplify the Quran's tales of what happened to those who rejected the prophets of old" or offered a political explanation.

Walid N. Arafat and Barakat Ahmad have disputed that the Banu Qurayza were killed on a large scale. Ahmad argues that only the leaders of the tribe were killed. Arafat argued that Ibn Ishaq gathered information from descendants of the Qurayza Jews, who embellished or manufactured the details of the incident. Watt finds Arafat's arguments "not entirely convincing."

References in literature

The fate of the Banu Qurayza became the subject of Shaul Tchernichovsky's Hebrew poem Ha-aharon li-Venei Kuraita (The Last of the Banu Qurayza).

See also

Notes

- Peterson, Muhammad: the prophet of God, p. 126.

- Ramadan, In the Footsteps of the Prophet, p. 141.

- Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, vol. 1, p. 191.

- Brown, A New Introduction to Islam, p. 81.

- ^ Watt, Encyclopaedia of Islam, "Kurayza, Banu".

- ^ Watt, Encyclopaedia of Islam, "Al-Madina".

- Stillman, The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book, p. 9.

- ^ Encyclopedia Judaica, "Qurayza".

- Guillaume, The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah, p. 7.

- Serjeant, "The "Sunnah Jami'ah, Pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the "Tahrim" of Yathrib: Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the So-Called Constitution of Medina", p. 2-3.

- ^ Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 192-193.

- Muslim sources usually referred to Himyar kings by the dynastic title of "Tubba".

- Guillaume, p. 7-9; Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 49-50.

- ^ Watt, "Muhammad", in: The Cambridge History of Islam.

- For alliances see Guillaume, p. 253.

- Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, "Qurayza (Banu)".

- Firestone, Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam, p. 118, 170. For opinions disputing the early date of the Constitution of Medina, see e.g., Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 119.

- Welch, "Muhammad", Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- ^ Serjeant, p. 36. Cite error: The named reference "serjeant" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Stillman, p. 14-16.

- M. H. Ananikian, "Tahrif or the alteration of the bible according to the Moslems", p. 63-64.

- Guillaume, p. 267-268.

- ^ Nomani, p. 382.

- See e.g. Stillman, p. 13.

- Heck, "Arabia Without Spices: An Alternate Hypothesis", p. 547-5.

- Watt, Muhammad at Medina, p. 36.

- Watt, Muhammad at Medina, p. 38.

- Guillaume, p. 453.

- See also above for the critical view on the historicity of this treaty.

- Guillaume, p. 458-459.

- Peterson, Muhammad: the prophet of God, p. 125.

- Guillaume, p. 461-463; Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 222-223; Stillman, p. 137-140.

- ^ Watt, Muhammad, Prophet and Statesman, p. 171-174. Cite error: The named reference "WattProphetStatesman" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Guillaume, p. 463-464; Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 223-224; Stillman, p. 140-141; Adil, p. 395-396.

- Hashmi, Buchanan & Moore, States, Nations, and Borders: The Ethics of Making Boundaries.

- Ramadan, p. 145.

- ^ Peterson, p. 127.

- Guillaume, p. 464; Stillman, p. 141-142; partially cited in Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 224.

- William Muir, A Life of Mahomet and History of Islam to the Era of the Hegira, chapter XVII. Muir follows Hishami and also refers to Aisha, who had related: "But I shall never cease to marvel at her good humour and laughter, although she knew that she was to die." (Ibn Ishaq, Biography of Muhammad).

- Lecker, "On Arabs of the Banū Kilāb executed together with the Jewish Banū Qurayza", p. 69.

- Rodinson, Muhammad: Prophet of Islam, p. 213.

- Ramadan, p. 146.

- Watt, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman, p. 175.

- ^ Arafat, "New Light on the Story of Banu Qurayza and the Jews of Medina", p. 100-107. Arafat relates the testimony of Ibn Hajar, who denounced this and other accounts as "odd tales" and quoted Malik ibn Anas, a contempory of Ibn Ishaq, whom he rejected as a "liar", an "impostor" and for seeking out the Jewish descendants for gathering information about Muhammad's campaign with their forefathers.

- Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 224.

- Peters, Islam. A Guide for Jews and Christians, p. 77.

- Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, p. 754.

- Ahmad, Muhammad and the Jews: A Re-examination.

- Nemoy, "Barakat Ahmad's "Muhammad and the Jews"", p. 325. Nemoy is sourcing Ahmed's Muhammad and the Jews.

Literature

General references

- Encyclopaedia of Islam. Ed. P. Bearman et al., Leiden: Brill, 1960-2005.

- Encyclopedia Judaica (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. Cecil Roth. Keter Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 965-07-0665-8

Jewish tribes

- Arafat, Walid N., "New Light on the Story of Banu Qurayza and the Jews of Medina", in: JRAS 1976, p. 100-107.

- Ahmad, Barakat, Muhammad and the Jews, a Re-examination, New Delhi. Vikas Publishing House for Indian Institute of Islamic studies. 1979

- Lecker, Michael, "On Arabs of the Banū Kilāb executed together with the Jewish Banū Qurayza", in: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 19 (1995), p. 69.

- Nemoy, Leon, "Barakat Ahmad's "Muhammad and the Jews"", in: The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, vol. 72, No. 4. (April 1982), p. 325.

- Serjeant, R. B., "The "Sunnah Jami'ah, Pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the "Tahrim" of Yathrib: Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the So-Called Constitution of Medina", in: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 41 (1978), p. 1-42.

- Stillman, Norman, The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1979. ISBN 0-8276-0198-0

Further reading

- Bat Ye'or. The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians under Islam. London: Associated University Presses, 1985.

- Lecker, Michael. Jews and Arabs in Pre- And Early Islamic Arabia. Ashgate Publishing, 1999.

- Newby, Gordon Darnell. A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam (Studies in Comparative Religion). University of South Carolina Press, 1988.

Background: Muhammad, Islam and Arabia

- Adil, Hajjah Amina, Muhammad: The Messenger of Islam. Islamic Supreme Council of America, 2002, p. 395-396

- Ananikian, M. H., "Tahrif or the alteration of the bible according to the Moslems." The Muslim World Volume 14, Issue 1 (January 1924), p. 63-64.

- Brown, Daniel W., A New Introduction to Islam. Blackwell Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0631216049

- Firestone, Reuven, Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-512580-0

- Guillaume, Alfred, The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah. Oxford University Press, 1955. ISBN 0-1963-6033-1

- Hashmi, Sohail H., Buchanan, Allen E. & Moore, Margaret, States, Nations, and Borders: The Ethics of Making Boundaries. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Hawting, Gerald R. & Shareef, Abdul-Kader A., Approaches to the Qur'an. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415057558

- Heck, Gene W., "Arabia Without Spices: An Alternate Hypothesis", in: Journal Of The American Oriental Society 123 (2003), p. 547-567.

- Hodgson, Marshall G.S., The Venture of Islam. University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- Meri, Josef W., Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0415966906.

- Muir, William, A Life of Mahomet and History of Islam to the Era of the Hegira, vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1861.

- Nomani, Shibli, Sirat al-Nabi. Karachi: Pakistan Historical Society, 1970.

- Peters, Francis E., Muhammad and the Origins of Islam. State University of New York Press, 1994. ISBN 0-7914-1875-8.

- Peters, Francis E., Islam. A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Peterson, Daniel C., Muhammad: the prophet of God. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 2007.

- Ramadan, Tariq, In the Footsteps of the Prophet. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Rodinson, Maxime, Muhammad: Prophet of Islam, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2002. ISBN 1860648274

- Watt, William Montgomery, "Muhammad", in: The Cambridge History of Islam, vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- Watt, William Montgomery, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press, 1961.

External links

- PBS site on the Jews of Medina

- Muhammad, the Qurayza Massacre, and PBS by Andrew G. Bostom

- Relevant chapters of Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum, by al-Mubarakpuri