| Revision as of 20:40, 3 February 2010 editWolfkeeper (talk | contribs)31,832 edits rv: reinserted needed comic link← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:20, 3 February 2010 edit undoSubzerosmokerain (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers4,132 editsm Undid revision 341748649 by Wolfkeeper (talk) It may be humorous and conveys a point but it is opinionated. WP:ASFNext edit → | ||

| Line 351: | Line 351: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 23:20, 3 February 2010

This redirect is about the fictitious force related to rotating reference frames. For the reaction force to the centripetal force, see Reactive centrifugal force. For the general subject of centrifugal force, see Centrifugal force (disambiguation). For general derivations and discussion of fictitious forces, see Fictitious force.| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

| Second law of motion |

| Branches |

| Fundamentals |

| Formulations |

| Core topics |

| Rotation |

| Scientists |

In classical mechanics, centrifugal force is an outward force associated with curved motion, that is, rotation about some (possibly not stationary) center. Centrifugal force is one of several so-called pseudo-forces (also known as inertial forces), so named because, unlike fundamental forces, they do not originate in interactions with other bodies situated in the environment of the particle upon which they act. Instead, centrifugal force originates in the curved motion of the frame of reference within which observations are made.

Derivation

Main article: Rotating reference frame See also: Fictitious forceVelocity

In a rotating frame of reference bodies can have the same positions as in a nonrotating frame, but they will move differently due to the rotation of the frame. Consequently, the time derivatives of any position vector r depending on time (velocity dr/dt and acceleration dr/dt) will differ according to the rotation. When time derivative is evaluated from a reference frame with a coincident origin at but rotating with the absolute angular velocity Ω:

where denotes the vector cross product and square brackets denote evaluation in the rotating frame of reference. In other words, the apparent velocity in the rotating frame is altered by the amount of the apparent rotation at each point, which is perpendicular to both the vector from the origin r and the axis of rotation Ω and directly proportional in magnitude to each of them. The vector Ω has magnitude Ω equal to the rate of rotation and is directed along the axis of rotation according to the right-hand rule. The angle must be measured in radians per unit of time.

Acceleration

Newton's law of motion for a particle of mass m can be written in vector form as

where F is the vector sum of the physical forces applied to the particle and a is the absolute acceleration of the particle, given by:

where r is the position vector of the particle. The differentiations are performed in the inertial frame.

By twice applying the transformation above from the inertial to the rotating frame, the absolute acceleration of the particle can be written as:

Force

The apparent acceleration in the rotating frame is . An observer unaware of the rotation would expect this to be zero in the absence of outside forces. However Newton's first law applies only in the inertial frame, to the absolute acceleration dr/dt. Therefore the observer perceives the extra terms as accelerations imposed by fictitious forces. These terms in the apparent acceleration are independent of mass; so it appears that each of these fictitious forces, like gravity, pulls on an object in proportion to its mass. When these forces are added, the equation of motion has the form:

which, from a formal mathematical standpoint, is the same result as simply moving the extra acceleration terms to the left hand side (the force side) of the equation. From the viewpoint of the rotating frame, however, the terms on the force side all result from forces really experienced as forces. The terms on the force side of the equation can be recognized as the Euler force , the Coriolis force , and the centrifugal force , respectively. The centrifugal force points directly away from the axis of rotation of the rotating reference frame, with magnitude mΩr.

Notice that for a non-rotating inertial frame of reference the centrifugal force and all other fictitious forces disappear.

Advantages of rotating frames

When living on Earth the rotating frame of reference is far more convenient to use than one in which our velocity changes daily by hundreds of kilometers per hour. But even from the abstract stance of solving problems in mechanics, a rotating reference frame can have advantages over an inertial reference frame. Sometimes the calculations are simpler (an example is inertial circles), and sometimes the intuitive picture coincides more closely with the rotational frame (an example is sedimentation in a centrifuge). By treating the extra acceleration terms due to the rotation of the frame as if they were forces, subtracting them from the physical forces, it's possible to treat the second time derivative of position (relative to the rotating frame) as absolute acceleration. Thus the analysis using Newton's law can proceed as if the reference frame was inertial, provided the fictitious force terms are included in the sum of forces. For example, centrifugal force is used in the FAA pilot's manual in describing turns. Other examples are such systems as planets, centrifuges, carousels, turning cars, spinning buckets, and rotating space stations. Regarding the advantages of rotating frames from the viewpoint of meteorology, Ryder says:

A simple way of dealing with this problem is, of course, to transform all coordinates to an inertial system. This is, however, sometimes inconvenient. Suppose, for example, we wish to calculate the movement of air masses in the earth's atmosphere due to pressure gradients. We need the results relative to the rotating frame, the earth, so it is better to stay within this coordinate system if possible. This can be achieved by introducing fictitious (or "non-existent") forces which enable us to apply Newton's Laws of Motion in the same way as in an inertial frame.

— Peter Ryder: Classical Mechanics, pp. 78-79

A disadvantage of a rotating reference frame is that it can be more difficult to apply special relativity (for example, from the perspective of the Earth the stars seem to traverse many light-years each day). It is possible to do so if a metric tensor is introduced, but the speed of light may not be constant and clocks within the frame are not synchronized.

Centrifugal force and absolute rotation

Main article: Absolute rotationCentrifugal force provides one way to detect absolute rotation - to determine whether it is an observed object or the observer that is rotating. Three experiments suggested by Newton can do this:

- In a rotating bucket the surface of the water takes on a concave shape imposed by centrifugal force.

- When two spheres are tethered together by a string, the string can only be free of tension in a non-rotating frame, and otherwise will have a tension proportional to the centrifugal force on each as it rotates around the common center of mass.

- A sphere of freely flowing material in free-fall, such as a planet in formation, forms a shape reflecting the balance between internal gravity and centrifugal force from its rotation. The extent of flattening depends also on the make-up of the planet, not only today but during its formation; while small for the Earth it is large enough for Jupiter and Saturn to be observable with a small telescope.

Examples

Below several examples illustrate both the inertial and rotating frames of reference, and the role of centrifugal force and its relation to Coriolis force in rotating frameworks. For more examples see Fictitious force, rotating bucket and rotating spheres.

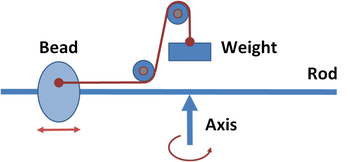

Whirling table

An apparatus called a "whirling table" consists of a rod that can be whirled about an axis, causing a bead to slide on the rod under the influence of centrifugal force. A cord ties a weight to the sliding bead. By observing how the equilibrium balancing distance varies with the weight and the speed of rotation, the centrifugal force can be measured as a function of the rate of rotation and the distance of the bead from the center of rotation.

From the viewpoint of an inertial frame of reference, equilibrium results when the bead is positioned to select the particular circular orbit for which the weight provides the correct centripetal force.

As a lab experiment, it seems arbitrary whether to deal with centripetal force or centrifugal force. From the bead's standpoint, however, centrifugal force is real and is pushing the bead.

Skywriter

See also: Centripetal force § Example: The banked turn

What is the viewpoint of an airplane pilot engaged in skywriting? The plane's path is the smoky trail left behind, and progress can be registered as the distance s from the start of the trail to the plane's present position. The speed of the plane is v = ds / dt and the curvature of the path is measured by the osculating circle of radius ρ that is tangent to the path. For the inertial observer watching from the ground, the plane at any instant is executing circular motion about its (instantaneous) center of curvature, and so is subject to a centripetal force v / ρ acting radially inward toward this center of curvature. To maintain trajectory, this centripetal force is provided by banking the airplane, generating a lift that provides this centripetal force. According to the pilot, however, the plane is stationary, but subject to a centrifugal force outward from the instantaneous center of curvature with a magnitude v / ρ. To maintain trajectory, this centrifugal force is combated by banking the airplane, generating a lift to counteract the centrifugal force, thereby maintaining the plane in its equilibrium motionless position. For a detailed analysis, see Mechanics of planar particle motion.

The banked turn

Main article: Banked turn See also: Centripetal force § Example: The banked turn, and Reactive centrifugal force § Example: The turning carRiding a car around a curve, we take a personal view that we are at rest in the car, and should be undisturbed in our seats. Nonetheless, we feel sideways force applied to us from the seats and doors and a need to lean to one side. To explain the situation, we propose a centrifugal force that is acting upon us and must be combated. Interestingly, we find this discomfort is reduced when the curve is banked, tipping the car inward toward the center of the curve.

A different point of view is that of the highway designer. The designer views the car as executing curved motion and therefore requiring an inward centripetal force to impel the car around the turn. By banking the curve, the force exerted upon the car in a direction normal to the road surface has a horizontal component that provides this centripetal force. That means the car tires no longer need to apply a sideways force to the car, but only a force perpendicular to the road. By choosing the angle of bank to match the car's speed around the curve, the car seat transmits only a perpendicular force to the passengers, and the passengers no longer feel a need to lean nor feel a sideways push by the car seats or doors.

Apparent motion of stationary objects

Main article: Fictitious force

Though centrifugal force adequately describes the force on objects at rest relative to a steadily rotating frame of reference, the fictitious force on objects moving in the rotating frame includes the Coriolis force. To deal with motion directly in a rotating frame of reference by applying Newton's laws, it is necessary to take these pseudo-forces into account. For example, consider the apparent revolution of a stationary object (such as a distant star or planet), which is in motion as viewed from the rotating frame:

A body that is stationary relative to a non-rotating inertial frame appears to be rotating when viewed from a frame rotating at angular rate Ω. Therefore, application of Newton's laws to what looks like circular motion in the rotating frame at a radius r, requires an inward centripetal force of −m Ω r to account for the apparent circular motion. This centripetal force in the rotating frame is provided as a net fictitious force that is the sum of the radially outward centrifugal force m Ω r and the Coriolis force −2m Ω × vrot. To evaluate the Coriolis force, we need the velocity as seen in the rotating frame, vrot. As explained in the Derivation section, this velocity is given by −Ω × r. This rotational motion, following the fixed stars, diminishes the apparent centrifugal force (the Eötvös effect), because the Coriolis force points inward when is evaluated for in the direction of vrot. This inward force has the value −2m Ω r. The combination of the centrifugal and Coriolis force is then m Ω r − 2m Ω r = −m Ω r, exactly the centripetal force required by Newton's laws for circular motion.

A similar analysis can be made for a ball that steadily drops at a constant rate parallel to the axis of rotation. From an inertial frame of reference it moves in a straight line, but from the rotating frame it moves in a spiral. As for a stationary object, the ball's motion must be explained by a fictitious inward centripetal force that produces the apparent spiral motion, and this force once again is the Coriolis force.

Earth

A calculation for Earth at the equator ( seconds, meters) shows that an object experiences a centrifugal force equal to approximately 1/289 of standard gravity. Because centrifugal force increases according to the square of , one would expect gravity to be cancelled for an object travelling 17 times faster than the Earth's rotation, and in fact satellites in low orbit at the equator complete 17 full orbits in one day.

Gravity diminishes according to the inverse square of distance, but centrifugal force increases in direct proportion to the distance. Thus a circular geosynchronous orbit has a radius of 42164 km; 42164/6378.1 = 6.61, the cube root of 289.

Planetary motion

See also: Orbit, Two-body problem, and Kepler's laws of planetary motionCentrifugal force arises in the analysis of orbital motion and, more generally, of motion in a central-force field – in the case of a two-body problem, it is easy to convert to an equivalent one-body problem with force directed to or from an origin, and motion in a plane, so we consider only that.

The symmetry of a central force lends itself to a description in polar coordinates. The dynamics of a mass, m, expressed using Newton's second law of motion (F = ma), becomes in polar coordinates:

where is the force accelerating the object and the "hat" variables are unit direction vectors ( points in the centrifugal or outward direction, and is orthogonal to it).

In the case of a central force, relative to the origin of the polar coordinate system, can be replaced by , meaning the entire force is the component in the radial direction. An inward force of gravity would therefore correspond to a negative-valued F(r).

The components of F = ma along the radial direction therefore reduce to

in which the term proportional to the square of the rate of rotation appears on the acceleration side as a "centripetal acceleration", that is, a negative acceleration term in the direction. In the special case of a planet in circular orbit around its star, for example, where is zero, the centripetal acceleration alone is the entire acceleration of the planet, curving its path toward the sun under the force of gravity, the negative F(r).

As pointed out by Taylor, for example, it is sometimes convenient to work in a co-rotating frame, that is, one rotating with the object so that the angular rate of the frame, , equals the of the object in the inertial frame. In such a frame, the observed is zero and alone is treated as the acceleration – so in the equation of motion, the term is “reincarnated on the force side of the equation (with opposite signs, of course) as the centrifugal force mΩr in the radial equation”:Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

where the term is known as the centrifugal force. The centrifugal force term in this equation is called a "fictitious force", "apparent force", or "pseudo force", as its value varies with the rate of rotation of the frame of reference. When the centrifugal force term is expressed in terms of parameters of the rotating frame, replacing with , it can be seen that it is the same centrifugal force previously derived for rotating reference frames.

Because of the absence of a net force in the azimuthal direction, conservation of angular momentum allows the radial component of this equation to be expressed solely with respect to the radial coordinate, r, and the angular momentum , yielding the radial equation (a "fictitious one-dimensional problem" with only an r dimension):

- .

The term is again the centrifugal force, a force component induced by the rotating frame of reference. The equations of motion for r that result from this equation for the rotating 2D frame are the same that would arise from a particle in a fictitious one-dimensional scenario under the influence of the force in the equation above. If F(r) represents gravity, it is a negative term proportional to 1/r, so the net acceleration in r in the rotating frame depends on a difference of reciprocal square and reciprocal cube terms, which are in balance in a circular orbit but otherwise typically not. This equation of motion is similar to one originally proposed by Leibniz. Given r, the rate of rotation is easy to infer from the constant angular momentum L, so a 2D solution can be easily reconstructed from a 1D solution of this equation.

When the angular velocity of this co-rotating frame is not constant, that is, for non-circular orbits, other fictitious forces – the Coriolis force and the Euler force – will arise, but can be ignored since they will cancel each other, yielding a net zero acceleration transverse to the moving radial vector, as required by the starting assumption that the vector co-rotates with the planet. In the special case of circular orbits, in order for the radial distance to remain constant the outward centrifugal force must cancel the inward force of gravity; for other orbit shapes, these forces will not cancel, so r will not be constant.

Development of the modern conception of centrifugal force

Main article: History of the concepts of centrifugal and centripetal forcesConcepts of centripetal and centrifugal force played a key early role in establishing the set of inertial frames of reference and the significance of fictitious forces, even aiding in the development of general relativity.

Applications

The operations of numerous common rotating mechanical systems are most easily conceptualized in terms of centrifugal force. For example: Template:Multicol

- A centrifugal governor regulates the speed of an engine by using spinning masses that move radially, adjusting the throttle, as the engine changes speed. In the reference frame of the spinning masses, centrifugal force causes the radial movement.

- A centrifugal clutch is used in small engine-powered devices such as chain saws, go-karts and model helicopters. It allows the engine to start and idle without driving the device but automatically and smoothly engages the drive as the engine speed rises. Inertial drum brake ascenders used in rock climbing and the inertia reels used in many automobile seat belts operate on the same principle.

- Centrifugal forces can be used to generate artificial gravity, as in proposed designs for rotating space stations. The Mars Gravity Biosatellite will study the effects of Mars-level gravity on mice with gravity simulated in this way.

- Spin casting and centrifugal casting are production methods that uses centrifugal force to disperse liquid metal or plastic throughout the negative space of a mold.

- Centrifuges are used in science and industry to separate substances. In the reference frame spinning with the centrifuge, the centrifugal force induces a hydrostatic pressure gradient in fluid-filled tubes oriented perpendicular to the axis of rotation, giving rise to large buoyant forces which push low-density particles inward. Elements or particles denser than the fluid move outward under the influence of the centrifugal force. This is effectively Archimedes' principle as generated by centrifugal force as opposed to being generated by gravity.

- Some amusement park rides make use of centrifugal forces. For instance, a Gravitron’s spin forces riders against a wall and allows riders to be elevated above the machine’s floor in defiance of Earth’s gravity.

Template:Multicol-end Nevertheless, all of these systems can also be described without requiring the concept of centrifugal force, in terms of motions and forces in an inertial frame, at the cost of taking somewhat more care in the consideration of forces and motions within the system.

See also

- Analytical mechanics

- Applied mechanics

- Bucket argument

- Calculating relative centrifugal force

- Centrifuge

- Centripetal force

- Circular motion

- Clairaut's theorem

- Classical mechanics

- Coriolis effect (perception)

- Coriolis force

- D'Alembert's principle

- Dynamics (physics)

- Equivalence principle

- Euler force

- Fictitious force

- Folk physics

- Frame of reference

- Frenet-Serret formulas

- Inertial frame of reference

- Kinematics

- Kinetics (physics)

- Lamm equation

- Lagrangian point

- Mechanics of planar particle motion

- Orthogonal coordinates

- Reactive centrifugal force

- Rotational motion

- Statics

Notes and references

- Robert Resnick & David Halliday (1966). Physics. Wiley. p. 121. ISBN 0471345245.

- Jerrold E. Marsden, Tudor S. Ratiu (1999). Introduction to Mechanics and Symmetry: A Basic Exposition of Classical Mechanical Systems. Springer. p. 251. ISBN 038798643X.

- ^ John Robert Taylor (2005). Classical Mechanics. University Science Books. p. 343. ISBN 189138922X. Cite error: The named reference "Taylor_A" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Stephen T. Thornton &

Jerry B. Marion (2004). Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems (5th ed.). Belmont CA: Brook/Cole. Chapter 10. ISBN 0534408966.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help); line feed character in|author=at position 22 (help) - David McNaughton. "Centrifugal and Coriolis Effects". Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- David P. Stern. "Frames of reference: The centrifugal force". Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- John L. Synge (2007). Principles of Mechanics (Reprint of Second Edition of 1942 ed.). Read Books. p. 347. ISBN 1406746703.

- By "absolute" is meant as seen in any inertial frame of reference; for example "absolute acceleration" or "absolute derivative".

- Vladimir Igorević Arnolʹd (1989). Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-387-96890-2.

-

Cornelius Lanczos (1986). The Variational Principles of Mechanics (Reprint of Fourth Edition of 1970 ed.). Dover Publications. Chapter 4, §5. ISBN 0-486-65067-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - LD Landau and LM Lifshitz (1976). Mechanics (Third ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7506-2896-9.

- Louis N. Hand, Janet D. Finch (1998). Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 0521575729.

- Mark P Silverman (2002). A universe of atoms, an atom in the universe (2 ed.). Springer. p. 249. ISBN 0387954376.

- John Robert Taylor (2005). op. cit.. Sausalito, Calif.: Univ. Science Books. p. 329. ISBN 189138922X.

-

Morton Tavel (2002). Contemporary Physics and the Limits of Knowledge. Rutgers University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0813530776.

Noninertial forces, like centrifugal and Coriolis forces, can be eliminated by jumping into a reference frame that moves with constant velocity, the frame that Newton called inertial.

- John Robert Taylor (2004). Classical Mechanics. Sausalito CA: University Science Books. Chapter 9, pp. 327 ff. ISBN 189138922X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - Federal Aviation Administration (2007). Pilot's Encyclopedia of Aeronautical Knowledge. Oklahoma City OK: Skyhorse Publishing Inc. Figure 3-21. ISBN 1602390347.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - Richard Hubbard (2000). Boater's Bowditch: The Small Craft American Practical Navigator. NY: McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 54. ISBN 0071361367.

- Lawrence K. Wang, Norman C. Pereira (1979). Handbook of Environmental Engineering: Air and Noise Pollution Control. Humana Press. p. 63. ISBN 0896030016.

- Lee M. Grenci, Jon M. Nese (2001). A World of Weather: Fundamentals of Meteorology. Kendall Hunt. p. 272. ISBN 0787277169.

- Peter Ryder (2007). Classical Mechanics. Aachen Shaker. p. 78–79. ISBN 978-3-8322-6003-3.

- Philip Gibbs. "Physics FAQ". University of California Riverside.

- T.A.Weber. "Measurements on a rotating frame in relativity, and the Wilson and Wilson experiment" (PDF). Am J Phys. pp. 946–953.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 57 (help) - Louis N. Hand, Janet D. Finch (1998). Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 324. ISBN 0521575729. and I. Bernard Cohen, George Edwin Smith (2002). The Cambridge companion to Newton. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0521656966.

- Archibald Tucker Ritchie (1850). The Dynamical Theory of the Formation of the Earth. Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. p. 529.

- John Clayton Taylor (2001). Hidden unity in nature's laws. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0521659388.

-

Hugh Murray (1837). "Figure and constitution of the Earth deduced from the theory of gravitation". The Encyclopædia of Geography. Vol. vol. 1. Carey, Lea & Blanchard. pp. 124 ff.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Alexander Winchell (1888). World-life; Or, Comparative Geology. SC Griggs & Co. p. 425.

- Lang, Kenneth R. (2003). "Jupiter: a giant primitive planet". NASA. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- Dionysius Lardner (1877). Mechanics. Oxford University Press. p. 150.

- Donald A. Danielson (2003). Vectors and Tensors in Engineering and Physics. Westview Press. p. 86. ISBN 0813340802.

- Denison Olmsted & Ebenezer Strong Snell (1861). An Introduction to Natural Philosophy. Collins & Brother. p. 133.

- As seen by the inertial observer, the plane also may accelerate along its path (dv / dt = ds / dt > 0). For the pilot this acceleration introduces another fictitious force: the Euler force.

- Lawrence S. Lerner (1996). Physics for Scientists and Engineers. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 0763702536.

- Louis N. Hand & Janet D. Finch (1998). Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 0521575729.

- John Robert Taylor (2004). Classical Mechanics. Sausalito CA: University Science Books. p. 343–344.

- Georg Joos & Ira M. Freeman (1986). Theoretical Physics. New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 233. ISBN 0486652270.

- The vector cross product of the two orthogonal vectors Ω and r is a vector of magnitude equal to the product of their magnitudes, namely Ω r = vrot, and with direction given by the right-hand rule, in this case found by aligning the thumb with Ω, the index finger with r, and the middle finger normal to these two fingers points in the direction of −vrot.

- Louis Bevier Spinney (1911). A Text-book of Physics. Macmillan Co. pp. 47–49.

- Arthur Beiser & George J. Hademenos (2003). Applied physics: Based on Schaum's Outline of Theory and Problems of Applied Physics (Third Edition). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 37. ISBN 0071398783.

- Burgel, B. (1967). "Centrifugal Force". American Journal of Physics. 35: 649. doi:10.1119/1.1974204.

- An elementary treatise on analytic mechanics: with numerous examples. 1920.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - Robert and Gary Ehrlich (1998). What if you could unscramble an egg?.

- ^ Herbert Goldstein (1950). Classical Mechanics. Addison-Wesley. p. 24–25, 61–64.

- ^ John Robert Taylor (2005). Classical mechanics. University Science Books. p. 358–359. ISBN 9781891389221.

- Henry M. Stommel and Dennis W. Moore (1989). An introduction to the Coriolis force. Columbia University Press. p. 28–40. ISBN 9780231066365.

- John Robert Taylor (2005). op. cit.. Sausalito, Calif.: Univ. Science Books. p. 359. ISBN 189138922X.

- Frank Swetz, John Fauvel, Otto Bekken, Bengt Johansson, and Victor Katz (1997). Learn from the masters!. Mathematical Association of America. p. 268–269. ISBN 9780883857038.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Whiting, J.S.S. (1983). "Motion in a central-force field" (PDF). Physics Education. 18 (6): pp. 256–257. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/18/6/102. ISSN 0031-9120. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Newton's description in Principia

- Centrifugal reaction force - Columbia electronic encyclopedia

- M. Alonso and E.J. Finn, Fundamental university physics, Addison-Wesley

- Centripetal force vs. Centrifugal force - from an online Regents Exam physics tutorial by the Oswego City School District

- Centrifugal force acts inwards near a black hole

- Centrifugal force at the HyperPhysics concepts site

- A list of interesting links

- Part of a high school course on astronomy, Newtonian mechanics and spaceflight by David P. Stern

External links

- h2g2 'The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy'

- Motion over a flat surface Java physlet by Brian Fiedler (from School of Meteorology at the University of Oklahoma) illustrating fictitious forces. The physlet shows both the perspective as seen from a rotating and from a non-rotating point of view.

- Motion over a parabolic surface Java physlet by Brian Fiedler (from School of Meteorology at the University of Oklahoma) illustrating fictitious forces. The physlet shows both the perspective as seen from a rotating and as seen from a non-rotating point of view.

- Animation clip showing scenes as viewed from both an inertial frame and a rotating frame of reference, visualizing the Coriolis and centrifugal forces.

- Centripetal and Centrifugal Forces at MathPages

- What is a centrifuge?

- John Baez: Does centrifugal force hold the Moon up?

but rotating with the absolute

but rotating with the absolute

denotes the

denotes the  at each point, which is perpendicular to both the vector from the origin r and the axis of rotation Ω and directly proportional in magnitude to each of them. The vector Ω has magnitude Ω equal to the rate of rotation and is directed along the axis of rotation according to the

at each point, which is perpendicular to both the vector from the origin r and the axis of rotation Ω and directly proportional in magnitude to each of them. The vector Ω has magnitude Ω equal to the rate of rotation and is directed along the axis of rotation according to the

, the

, the  , and the centrifugal force

, and the centrifugal force  , respectively. The centrifugal force points directly away from the axis of rotation of the rotating reference frame, with magnitude mΩr.

, respectively. The centrifugal force points directly away from the axis of rotation of the rotating reference frame, with magnitude mΩr.

the centrifugal force and all other fictitious forces disappear.

the centrifugal force and all other fictitious forces disappear.

in the direction of vrot. This inward force has the value −2m Ω r. The combination of the centrifugal and Coriolis force is then m Ω r − 2m Ω r = −m Ω r, exactly the centripetal force required by Newton's laws for circular motion.

in the direction of vrot. This inward force has the value −2m Ω r. The combination of the centrifugal and Coriolis force is then m Ω r − 2m Ω r = −m Ω r, exactly the centripetal force required by Newton's laws for circular motion.

seconds,

seconds,  meters) shows that an object experiences a centrifugal force equal to approximately 1/289 of

meters) shows that an object experiences a centrifugal force equal to approximately 1/289 of  , one would expect gravity to be cancelled for an object travelling 17 times faster than the Earth's rotation, and in fact satellites in low orbit at the equator complete 17 full

, one would expect gravity to be cancelled for an object travelling 17 times faster than the Earth's rotation, and in fact satellites in low orbit at the equator complete 17 full

is the force accelerating the object and the "hat" variables are unit direction vectors (

is the force accelerating the object and the "hat" variables are unit direction vectors ( points in the centrifugal or outward direction, and

points in the centrifugal or outward direction, and  is

is  , meaning the entire force is the component in the radial direction. An inward force of gravity would therefore correspond to a negative-valued F(r).

, meaning the entire force is the component in the radial direction. An inward force of gravity would therefore correspond to a negative-valued F(r).

is zero, the centripetal acceleration alone is the entire acceleration of the planet, curving its path toward the sun under the force of gravity, the negative F(r).

is zero, the centripetal acceleration alone is the entire acceleration of the planet, curving its path toward the sun under the force of gravity, the negative F(r).

of the object in the inertial frame. In such a frame, the observed

of the object in the inertial frame. In such a frame, the observed  term is “reincarnated on the force side of the equation (with opposite signs, of course) as the centrifugal force mΩr in the radial equation”:Cite error: The

term is “reincarnated on the force side of the equation (with opposite signs, of course) as the centrifugal force mΩr in the radial equation”:Cite error: The

, yielding the radial equation (a "fictitious one-dimensional problem" with only an r dimension):

, yielding the radial equation (a "fictitious one-dimensional problem" with only an r dimension):

.

. term is again the centrifugal force, a force component induced by the rotating frame of reference. The equations of motion for r that result from this equation for the rotating 2D frame are the same that would arise from a particle in a fictitious one-dimensional scenario under the influence of the force in the equation above. If F(r) represents gravity, it is a negative term proportional to 1/r, so the net acceleration in r in the rotating frame depends on a difference of reciprocal square and reciprocal cube terms, which are in balance in a circular orbit but otherwise typically not. This equation of motion is similar to one originally proposed by

term is again the centrifugal force, a force component induced by the rotating frame of reference. The equations of motion for r that result from this equation for the rotating 2D frame are the same that would arise from a particle in a fictitious one-dimensional scenario under the influence of the force in the equation above. If F(r) represents gravity, it is a negative term proportional to 1/r, so the net acceleration in r in the rotating frame depends on a difference of reciprocal square and reciprocal cube terms, which are in balance in a circular orbit but otherwise typically not. This equation of motion is similar to one originally proposed by  vector co-rotates with the planet.

In the special case of circular orbits, in order for the radial distance to remain constant the outward centrifugal force must cancel the inward force of gravity; for other orbit shapes, these forces will not cancel, so r will not be constant.

vector co-rotates with the planet.

In the special case of circular orbits, in order for the radial distance to remain constant the outward centrifugal force must cancel the inward force of gravity; for other orbit shapes, these forces will not cancel, so r will not be constant.