| Revision as of 05:07, 30 May 2012 editGibson Flying V (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers92,854 edits →History: clarify← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:11, 30 May 2012 edit undoGibson Flying V (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers92,854 edits →History: prune quote back to topic of this article (comparison of two rugby codes, not two tournaments)Next edit → | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| In 1954 rugby league's inaugural World Cup tournament was played and in 1987 rugby union held its first World Cup. | In 1954 rugby league's inaugural World Cup tournament was played and in 1987 rugby union held its first World Cup. | ||

| {{Quote box |quoted=true |bgcolor=#FFFFF0 |salign=center |width=30em | {{Quote box |quoted=true |bgcolor=#FFFFF0 |salign=center |width=30em | ||

| | quote =Thirteen-man rugby league has shown itself to be a faster, more open game of better athletes than the other code. Rugby union is trying to negotiate its own escape from amateurism, with some officials admitting that the game is too slow, the laws too convoluted to attract a larger TV following |

| quote =Thirteen-man rugby league has shown itself to be a faster, more open game of better athletes than the other code. Rugby union is trying to negotiate its own escape from amateurism, with some officials admitting that the game is too slow, the laws too convoluted to attract a larger TV following. | ||

| | source =Ian Thomsen, '']'', 28 October 1995<ref>{{Cite news | | source =Ian Thomsen, '']'', 28 October 1995<ref>{{Cite news | ||

| | last = Ian | first = Thomsen | | last = Ian | first = Thomsen | ||

Revision as of 05:11, 30 May 2012

| This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (May 2012) |

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (May 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Comparison of rugby league and rugby union is possible because of the games' similarities and shared origins. Initially, following the 1895 split in rugby football, rugby league and rugby union differed in administration only. Soon however, the rules of rugby league were modified, resulting in two distinctly different forms of rugby. After 100 years rugby union joined rugby league, and most other forms of football, as an openly professional sport. One the most prominent differences between the two sports today is that rugby league has a system of limited tackles (not unlike American football) rugby union does not. Also rugby union has retained the prevalent use of scrums.

History

Further information: History of rugby league and History of rugby union

Marshall: "Oh, fie, go away naughty boy, I don't play with boys who can’t afford to take a holiday for football any day they like!"

Miller: "Yes, that’s just you to a T; you’d make it so that no lad whose father wasn’t a millionaire could play at all in a really good team. For my part I see no reason why the men who make the money shouldn’t have a share in the spending of it."

The precursor to both rugby union and rugby league was rugby football, a style of football named after Rugby School in the United Kingdom. Its origin is reputed to be an incident during a game of English school football at Rugby School in 1823 when William Webb-Ellis is said to have picked up the ball and run with it, although the evidence for this story is doubtful. During this early period different schools used different rules, on many occassions agreeing upon them shortly before commencement of the game. In 1871, English clubs playing the version of football played at Rugby School met to form the Rugby Football Union (RFU). Rugby football spread to Australia and New Zealand, with games being played in the early to mid nineteenth century.

In 1892, charges of professionalism were laid against Yorkshire clubs in Bradford and Leeds, after they compensated players for missing work. The Yorkshire clubs put forward a proposal that would allow players to receive up to six shillings (30 new pence) when they missed work because of match commitments, but the idea was voted down by the RFU, and widespread suspensions of northern clubs and players began. On 27 August 1895, as a result of an emergency meeting in Manchester, prominent Lancashire clubs declared that they would support their Yorkshire colleagues in their proposal to form a professional Northern Union. Two days later, representatives of twenty-two clubs met in the George Hotel, Huddersfield to form the Northern Rugby Football Union, usually called the Northern Union (NU). The rugby union authorities issued sanctions against clubs, players and officials involved in the new organisation, extending to amateurs who played with or against Northern Union sides. After the schism the separate codes were named "rugby league" and "rugby union".

In 1906, All Black George William Smith, while on his way home from the 1905 tour of Britain, met an Australian entrepreneur, James J. Giltinan to discuss the potential of professional rugby in Australasia. He joined with Albert Henry Baskerville, a lesser known rugby player who had written to the Northern Union asking if they would host a New Zealand touring party, to raise a team. George Smith cabled a friend in Sydney and three professional matches were arranged between a NSW rugby team before continuing onto the UK. This game was played under the rugby union laws and it wasn't until the team, nicknamed the All Golds, arrived in Leeds that they learnt the new Northern Union laws. Meanwhile in Sydney a meeting was organised to look at forming a professional rugby competition in Australia. The meeting resolved that a "New South Wales Rugby Football League" (NSWRFL) should be formed, to play the Northern Union rules. The first season of the NSWRFL competition was played in 1908, and has continued to be played every year since. In 1909, when the new "Northern Union" code was still in its infancy, a match between the Kangaroos and the Wallabies was played before a crowd of around 20,000, with the rugby league side winning 29-26. In France rugby league split from rugby union in the 1930s.

With the wartime Emergency League suspended, Leeds Rugby League reverted to rugby union during World War one to play a one-off challenge game against the Royal Navy Depot from Plymouth in 1917. This was pre-cursor to the following Christmas when two Challenge games were organised between the two sides but this time with one of each code. The Navy won the union game 9-3 on Christmas Eve but proved equally adept at league recording a 24-3 win on 28 December. During World War two, the RFU relaxed its restrictions on rugby league players playing rugby union. In 1943, a Northern Command army rugby league side defeated a Northern Command union side 18-11 at Headingley under rugby union laws. The following year a Combined Services rugby league side beat a Combined Services union side 15-10 at Bradford again at rugby union. These were the only league v union matches played until 1996.

In 1954 rugby league's inaugural World Cup tournament was played and in 1987 rugby union held its first World Cup.

Ian Thomsen, The New York Times, 28 October 1995Thirteen-man rugby league has shown itself to be a faster, more open game of better athletes than the other code. Rugby union is trying to negotiate its own escape from amateurism, with some officials admitting that the game is too slow, the laws too convoluted to attract a larger TV following.

On 26 August 1995 the International Rugby Board declared rugby union an "open" game and thus removed all restrictions on payments or benefits to those connected with the game. It did this because of a committee conclusion that to do so was the only way to end the hypocrisy of shamateurism and to keep control of rugby union. With both sports becoming professional matches between union and league teams have been played. In May 1996, Bath Rugby and Wigan RLFC, who were then England's top union and league sides respectively, made history by playing against each other at both codes of rugby. Wigan won 82-6 in the first match, played under league rules, and lost the second 44-19 under union rules. Since then other games have been played between union and league teams using the laws of one of the codes, or in some cases using a different set of laws each half. The inherent similarities between rugby league and rugby union has at times led to the possibility of a merger being mooted and experimental hybrid games have been played that use a mix of the two sport's rules.

Traditionally in England, the two rugbys have been seen as divided along class lines, with union associated more with the middle class, and league with the working class. One of the main reasons for the split was union's enforcement of the amatuer principle, meaning that working class players could not afford to take time off work to play the sport. In Australia the two codes were also strongly divided down class lines. League initially recruited big name players from union, like Herbert "Dally" Messenger in 1907, and the RFU responded by banning any player that played rugby league for life. Another push into converting union players, such as All Blacks John Gallagher, Frano Botica and Va'aiga Tuigamala, occurred in the 1980s and 1990s. When rugby union became professional league players were allowed to play for rugby union teams, leading to a reversal in crosscode switching as players, including big league names Wendell Sailor, Mat Rogers, Lote Tuqiri, Henry Paul and Iestyn Harris, took up rugby union contracts. All of these players subsequently switched back to rugby league.

Etymology

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the United Kingdom, rugby union or rugby league fans rarely refer to their sport as "football" as in most cases this would refer to association football. Across the UK, rugby union is usually referred to simply as 'rugby' but in and around the rugby league heartlands in the North of England, the word 'rugby' could refer to either sport but usually means 'rugby league'. The nickname "rugger", which developed in England's elite schools, almost always refers to rugby union. In Australia, both sports are most popular in Queensland, New South Wales, the Northern Territory, and the Australian Capital Territory. Rugby League is usually referred to as simply "football" or "footy" in these states. Rugby union is usually referred to simply as "rugby" by its followers, who generally refer to rugby league as "league". In other states people refer to both codes as "rugby". In New Zealand, "football" usually refers to either rugby union or association football, but depending on context could refer to rugby league. "Rugby", which almost universally refers to rugby union, is mostly used without any existing context. Rugby league is usually called "rugby league" or simply "league".

In France, rugby union is called rugby à quinze (rugby with 15) or simply "rugby" whilst rugby league is known as rugby à treize (rugby with 13) or jeu à treize (game with 13) or treize (13). In Italy the term "rugby" generally defines rugby union, but if a distinction is needed rugby league is called rugby a 13. In South Africa, Georgia, Japan, Romania and Argentina rugby league is not very well known and rugby union is simply called "rugby". In countries such as the United States, where neither code of rugby football is very well known, the two forms of the game are rarely distinguished between and "rugby" could refer to either. Rugby union is more commonly encountered in the United States, as it is the code of choice among college clubs; it is usually referred to simply as rugby. Rugby league is usually specifically referred to as rugby league. In Canada, both sports are known as English rugby. Canadian rugby is an alternate, but increasingly obsolete, term for Canadian football, as both it and American football are derived from early versions of rugby.

Gameplay

Further information: Rugby league gameplay and Rugby union gameplaySince the 1895 schism, changes have taken place to the laws of both rugby union and rugby league football so that now they are distinct sports. The laws of rugby league football have been gradually changed with the express intention of creating a faster, more entertaining and spectator-friendly sport. A distinction often cited is that rugby league has shed from its laws several opportunities for possession to be contested that rugby union has retained: contesting the ball after the tackle, on the ground in rucks and in mauls. As a result of the absence of the aforementioned mauls, rucks and line-outs, there are fewer stoppages of play in rugby league, with the ball typically in play for 50 out of the 80 minutes, compared with around 35 for professional rugby union. This, combined with the fact that thirteen rugby league players must cover the field of play as opposed to union's fifteen, implies that rugby league is the more physically demanding of the two sports. Rugby league is also simpler and easier for spectators to understand than rugby union. The laws of rugby league are consequently fewer, comprising 21,000 words compared to 35,000 for union.

Field

Further information: Rugby league playing field and Rugby union playing field

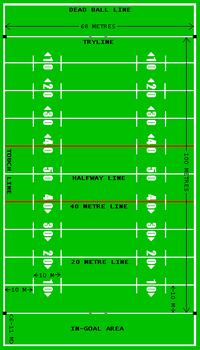

A rugby league field is between 112 and 122 metres long by 68m wide. The distance between try-lines is always 100 metres. There are lines going across the field which mark every ten metres. An in-goal area extends six to eleven metres beyond each goal-line. At the goal line is a set of goal posts in the shape of the letter 'H', used for other forms of point scoring: drop goal, penalty and conversion. A rugby union field is a maximum of 144 metres long by 70m wide. The length from try line to try line is always 100 metres: the only varying distances on a rugby field are the width of the playing field, and the distance from try line to the dead ball line. Lines are painted at the dead ball line, try line, 22 metre line, 10 metre line (broken line) and half way. Lines are also located 5 metres away from the try line and touch line and 15 metres away from the touch line. At the goal line is a set of goal posts in the shape of the letter 'H', used for other forms of point scoring: drop goal, penalty and conversion.

Players

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A maximum of 15 players can play rugby union at any one time whereas rugby league permits 13 players.

|

|

Many of the positions have similar names but in practice are very different. The position known as 'flanker' has no equivalent in rugby league; rugby league centres are split into left and right centre rather than inside and outside centres.

Until the professionalisation of rugby union, rugby league players have sometimes been regarded as more adept at a range of skills or roles in the game, whereas rugby union players are more specialised. For instance, props and hookers in rugby union tend to be among the physically strongest players with high levels of scrummaging and mauling skills, but (traditionally) with limited speed and ball-handling skills. In rugby league, props and hookers may be no slower or less adept at handling the ball than other players because they are not required to perform the physical aspects of scrummaging or contesting possession after a tackle and subsequently they are not required to perform the specialist skills of their rugby union counterparts where size is an advantage. Similarly, locks in union tend to be very tall, as this helps at lineouts; while this is not a necessity for league second rows and may even be a disadvantage. Scrum-half is also a more specialised position in rugby union: the number 9 initiates most moves by his or her team and must be an excellent passer of the ball, whereas in rugby league it is common for any player acting as 'dummy half' to do so.

Players who achieve the feat of international rugby in both codes are known as dual-code internationals.

Possession

A distinction between the two games often cited is that rugby league has shed from its laws several opportunities for possession to be contested that rugby union has retained: contesting the ball after the tackle, on the ground in rucks and in mauls. Additionally, rugby league uses a scrum to restart the game in those situations where rugby union uses a line-out. Though rugby league scrums are sometimes claimed to be uncontested, the laws provide for contested scrums should the non-feeding team attempt to contest the ball, though for several reasons a convention of lenient enforcement is in practice.

Rugby union has a greater scope for the contest of possession however a greater contest for possession does not necessarily result in greater turn over of possession or a more even division of possession. A statistical study of international rugby union matches between 1982-4 and 2002-4 commissioned by rugby union's world governing body, the IRB, entitled Changes in the Playing of International Rugby over a Twenty Year Period, concluded that "the contest for possession is largely predictable if not almost wholly guaranteed". The report also found that while in the 1980s teams in possession lost the ball to their opposition on average once every six breakdowns, by the 2000s possession was won by the defending team on average once every twenty-three breakdowns.

It has been argued that rugby league's six tackle rule results in a more even division of possession despite fewer opportunities to contest it.

Rugby league has a six-tackle rule (somewhat similar to "downs" in American and Canadian football). The team in possession has a "set of six" tackles before having to hand over possession. Thus, after being tackled five times, the attacking team will almost always tactically kick the ball to the sideline, the in-goal, or to an area of the field deemed advantageous to the attacking team and not so to the defending team.

Play stops when the player in possession of the ball is tackled; play restarts with a play-the-ball by the other team that were previously defending. Teams can only obtain a consecutive set of tackles in specific circumstances (by forcing a goal-line drop out, through a 40/20 kick, by being awarded a penalty, if the defending team deliberately touches the ball while not in possession, or defensive errors such as playing for the ball but not securing possession).

Rugby union is quite different, being based on the 'right to contest possession'. A team in possession does not need to surrender possession whilst they are able to keep the ball. Whilst rugby league players are not allowed to try to dispossess the ball carrier between tackles, unless the tackle committed is a one on one tackle, rugby union players are allowed to win possession during open play.

Possession remains contested in rugby union following a tackle, for instance if a ruck (in which the ball is on the ground) or maul (in which it is held off the ground) forms. The side in possession before the tackle can lose the ball to more aggressive play from their opponents, yielding what is known as a turnover. In rugby league, possession cannot be contested at this point: play either restarts with a play-the-ball or a handover.

While in rugby league both possession and field position are important, in rugby union field position takes precedence. In league, possession is usually considered more important than territory, as a player cannot score without the ball. In rugby league the primary method of scoring points is with tries, whereas in union point-scoring from kicks is often a more significant factor as players often prefer to infringe union's Laws at the tackle and risk a penalty kick to prevent the higher scoring Try. Rugby union is more a game of territory and players often kick possession away to the opposition to move play nearer the opposition goal line and posts as getting tackled in a bad position with no team members to help hold possession would lead to an easy try for the opposing team. However, in rugby league players will do everything possible to limit the amount of time the opposition has in possession of the rugby ball, which usually leads to 'no risk' play for as many tackles as possible before attempts at passing/kicking the ball for a try.

Possession may change in different ways in both games these are common to both codes

- When the ball is kicked to the opposing team, this can be done at any time but it is normal to punt on the last tackle in rugby league.

- Following an unsuccessful kick at goal in Union however in League when a kick at goal is missed and goes dead, play is restarted with a 20 metre drop out.

- When an opposing player intercepts a pass.

- When the player in possession drops the ball and it is recovered by an opposition player.

- The opposition are awarded a scrum if the player in possession drops the ball forwards or makes the ball go forwards with any part of his body other than their feet with one exception, if a player kicks the ball a player from the opposing team can charge the kick down, this is where a player jumps in front of the ball to try to stop it getting to the intended place, in a charge down it doesn't matter what part of the body the ball hits (this rule applies in league and union). When someone makes the ball go forward illegitimately, it is called a knock-on. In rugby league, it is uncommon for scrums to be contested. The side awarded the scrum almost always gains possession from it; the purpose is to restart the game with a good chance for open play as nearly half the players are concentrated in one spot. In rugby union, scrums are contested (i.e. each pack pushes against the other), and it is possible for the side awarded the scrum to lose possession.

Possession may change in rugby league in a number of unique ways

- In rugby league if the ball goes out of play, the opposition are awarded a scrum. If this is from a kick going into touch on the full this is called ball back and the scrum is formed where contact with the ball was made. Otherwise, under recent rule changes, the scrum is formed 20 metres from the point of touch. Penalties and 40/20 kicks are exceptions to this rule.

- In rugby league, an automatic handover takes place when the team in possession runs out of tackles.

Possession may change in rugby union in a number of unique ways

- In rugby union if the ball out of play the opposition maybe awarded a line-out. The opposition are awarded a line out if the team in possession kicks the ball out of play and they haven't been awarded a penalty before the kick.

- In rugby union the team in possession may also loose possession in a scrum or a line out

In both codes, tactical kicking is an important aspect of play. So is tackling.

Tackling

See also: tackle (football move)In both games it is permitted to bring down the player in possession of the ball and prevent them making forward progress. Tackling or interfering with a player who is not in possession of the ball is not permitted. In rugby union, charging or pushing an opponent in possession (e.g. by using the shoulder only) is not permitted. Tacklers must try to grasp the ball-carrier and bring them to ground. Rugby league allows an opponent to be charged (e.g. by using the shoulder only). Using the shoulder in rugby league is often considered a 'big hit'.

In rugby league, a tackle is deemed to be complete when the elbow of the arm holding the ball touches the ground, or the player is held in an upright tackle. The ball cannot be further advanced and a play-the-ball or handover must take place. In rugby union, a tackle is deemed to be complete when the player in possession is held on the ground; that player must play the ball (either releasing it, passing it, or if over the try line grounding the ball) immediately.

In rugby league a play the ball takes place after each tackle. In rugby union, play does not stop when a player is forced to the ground in a tackle, as the tackled player must immediately play the ball, and the tackler must roll away, which will generally mean a ruck will form.

Tripping with the leg is not allowed in either code. However, in rugby league, if a tackling player has both hands on the ball carrier, he is allowed to use his legs to bring him to ground.

The laws of rugby league specifically outlaw the so-called 'voluntary tackle': players are not allowed to go to ground unless they are effectively tackled by an opponent, though in practice this rule is rarely applied. There was no equivalent law in rugby union, in the past going to ground with the ball and protecting it was practised, but in the modern game deliberately falling on the ground to gain an advantage is outlawed by Law 14: "The game is to be played by players who are on their feet. A player must not make the ball unplayable by falling down." A player who falls to ground with the ball or on it must immediately release or pass the ball, or get up with it.

Scoring

Union and league have the same ways of scoring, but there are significant differences in the points awarded, and few minor differences in the laws governing the scoring of tries.

The try is the main way of scoring in both codes; there are some subtle differences between the two codes, but the most obvious difference is that a try is worth 5 points in rugby union and 4 points in rugby league. In both games, a conversion following a try is worth 2 points. A player tackled just short of the try-line in rugby union can legitimately reach across it and place the ball down for a try. This is not allowed in rugby league unless the momentum of the player continues to take him over the line in one continuous movement. If the tackle is complete, such a move would constitute a 'double movement' and the try would be disallowed.

A drop goal is worth 3 points in union and 1 in league. A penalty goal is worth 3 points in union and 2 points in league.

Other minor differences in the rules

In rugby league the ball may be thrown or knocked out of play deliberately while in union those are penalty offences. Kicking the ball out of play is legal in both codes.

When taking free or penalty kicks with a 'tap and go' option, rugby league permits a stylised kick with the ball being tapped against the foot or lower leg while union requires the ball to leave the hands of the kicker. This difference in emphasis on a relatively trivial phase of play can be seen as indicative of the core differences between the games. In league, the kick is stylised as its purpose is to restart the game and to move to the run and tackle main play as quickly as possible. In union, where every phase of play has some element of competition, the trivial need to release the ball at any kick can result in a fumble that may give the opposition a chance to either contest possession or, if 'knocked-on', will cause them to be awarded a scrum.

References

- Gilbert, Ian (10 October 2003). "The bluffer's guide". The Age. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "Webb Ellis, William". Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- "Flotsam". QI. Episode 3. UK. 9 January 2009. BBC. BBC One.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|seriesno=ignored (|series-number=suggested) (help) - Marshall 1951, pp. 13–14 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMarshall1951 (help)

- History of the ARU

- Baker, Andrew (20 August 1995). "100 years of rugby league: From the great divide to the Super era". Independent, The. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Tony Collins (2006). "Schism 1893–1895". Rugby's great split: class, culture and the origins of rugby league football (2nd ed.). Routlage. pp. 87–120. ISBN 0-415-39616-6.

- "Kangaroos v. Wallabies". West Coast Times. New Zealand. 6 September 1909. p. 4. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - http://www.napit.co.uk/viewus/infobank/rugby/superleague/history.php

- Ian, Thomsen (28 October 1995). "Australia Faces England at Wembley : A Final of Rugby Favorites". The New York Times. nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- Stubbs 2009, p. 118 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStubbs2009 (help)

- "History of the RFU". RFU. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Ontario: The Shamateurs". TIME. 29 September 1947. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Jones, Chris (9 October 2000). "It's all a code merger mystery". London Evening Standard. UK: ES London Limited. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- http://www.stuff.co.nz/sport/rugby/news/4994642/Hybrid-rugby-union-league-experiment

- Bowden, David (4 September 2009). "Tackling rugby union's superiority complex". Spiked. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/sport/working-class-formed-a-league-of-their-own/story-e6frexni-1111118120858

- Tony Collins (2006). Rugby's great split: class, culture and the origins of rugby. p. 180.

- http://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-06-24/dally-messenger-reinstated-to-nswru-record-books/79020

- http://www.rfu.com/TwickenhamStadium/WorldRugbyMuseum/RugbyHistory/AmateurEra

- http://www.irishrugby.ie/news/11928.php

- http://www.irishrugby.ie/news/11928.php

- Règles du rugby à XV par francerugby.fr

- Régles du Rugby à XIII, codification empruntée au site de la Ligue régionale de Midi-Pyrénées

- Hamilton, Garth (18 June 2007). "Black and White and Grey". Archived from the original on 25 July 2010.

- Cunneen, Chris (2001). The best ever Australian Sports Writing. Australia: Black Inc. p. 314. ISBN 1-86395-266-7. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gibson, Barry (8 October 2008). "A super sport, but no prima donnas". The Huddersfield Daily Examiner. UK: Trinity Mirror North West & North Wales Limited. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Telfer, Jim (5 May 2010). "It's Le Crunch for Magners League". STV. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - George Caplan, Mark Adams (2007). BTEC National: Sport. Heinemann. p. 99. ISBN 0-435-46514-7, 9780435465148.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Cleary, Mick (5 October 2000). "Talking Rugby: No code like the old code". telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Breivik, Simon L. (2007). Sport And Exercise Physiology Testing Guidelines: The British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences Guide. Taylor & Francis. p. 257. ISBN 0-415-36141-9, 9780415361415.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hey, Stan (25 September 1994). "Stevo's fight against a league of stereotypes". The Independent. UK: Independent News and Media Limited. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Howell, Andy (7 May 2007). "R League: Sport can flourish in Wales". Western Mail. Media Wales Ltd. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Laws of the Game: Rugby Union 2007." International Rugby Board, Dublin, 2007. Online version retrieved 22 October 2007.

- The ARL Laws of the Game, 2007. The Australian Rugby Football League. Online version retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ^ Collins, Tony (6 May 2010). "Mythbusters: The 'Contest for Possession'". Rugby Reloaded. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- David Campese, Peter Jenkins, Mal Meninga, Peter Frilingos (1994). My game, your game. Ironbark Press. p. 288. ISBN 0-330-35616-X, 9780330356169.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Categories: