| Revision as of 04:03, 9 June 2013 editJarble (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users149,707 edits →Marsupials: Fixing link to main article← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:20, 9 June 2013 edit undoJarble (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users149,707 edits →Marsupials: Fixing section indentationNext edit → | ||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

| ====Marsupials==== | ====Marsupials==== | ||

| {{main|Marsupial reproductive system}} | {{main|Marsupial reproductive system}} | ||

| {{Marsupial reproductive system}} | {{Marsupial reproductive system|Male = =====Male=====|Female = =====Female=====}} | ||

| ===Fish=== | ===Fish=== | ||

Revision as of 04:20, 9 June 2013

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: Most of this article's sections are unreferenced, and need additional citations. Please help improve this article if you can. (March 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Sexual reproduction is a process that creates a new organism by combining the genetic material of two organisms; it occurs both in eukaryotes and in prokaryotes. A key similarity between bacterial sex and eukaryotic sex is that DNA originating from two different individuals (parents) join up so that homologous sequences are aligned with each other, and this is followed by exchange of genetic information (a process called genetic recombination). After the new recombinant chromosome is formed it is passed on to progeny).

On the other hand, bacterial conjugation, a type of transfer of DNA between two bacteria, is often mistakenly confused with sexual reproduction, because the mechanics are similar. However, bacterial conjugation is controlled by plasmid genes that are adapted for spreading copies of the plasmid between bacteria. The infrequent integration of a plasmid into a host bacterial chromosome, and the subsequent transfer of a part of the host chromosome to another cell do not appear to be bacterial adaptations.

In contrast, bacterial transformation can be regarded as a form of sex in bacteria. Bacterial transformation is a complex process encoded by numerous bacterial genes, and is clearly a bacterial adaptation for DNA transfer. This process occurs naturally in at least 40 bacterial species. For a bacterium to bind, take up, and recombine exogenous DNA into its chromosome, it must enter a special physiological state referred to as competence (see Natural competence). Sexual reproduction in early single-celled eukaryotes may have evolved from bacterial transformation.

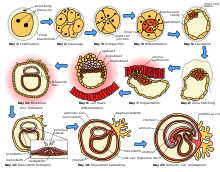

There are two main processes during sexual reproduction in eukaryotes: meiosis, involving the halving of the number of chromosomes; and fertilization, involving the fusion of two gametes and the restoration of the original number of chromosomes. During meiosis, the chromosomes of each pair usually cross over to achieve homologous recombination.

Sexual reproduction is the primary method of reproduction for the vast majority of macroscopic organisms, including almost all animals and plants. The evolution of sexual reproduction is a major puzzle (see Evolution of sexual reproduction). The first fossilized evidence of sexual reproduction in organisms such as eukaryotes is in the Stenian period, about 1 to 1.2 billion years ago.

Evolutionary thought proposes several explanations for why sexual reproduction developed and why it is maintained. These reasons include fighting the accumulation of deleterious mutations, increasing rate of adaptation to changing environments (see the red queen hypothesis), dealing with competition (see the tangled bank hypothesis) or as an adaptation for repairing DNA damage (see Evolution of sexual reproduction). The maintenance of sexual reproduction has been explained by theories that work at several different levels of selection, though some of these models remain controversial. New models presented in recent years, however, suggest a basic advantage for sexual reproduction in slowly reproducing, complex organisms, exhibiting characteristics that depend on the specific environment that the given species inhabit, and the particular survival strategies that they employ.

Plants

Main article: Plant reproductionAnimals typically produce male gametes called sperm, and female gametes called eggs and ova, following immediately after meiosis, with the gametes produced directly by meiosis. Plants on the other hand have mitosis occurring in spores, which are produced by meiosis. The spores germinate into the gametophyte phase. The gametophytes of different groups of plants vary in size; angiosperms have as few as three cells in pollen, and mosses and other so called primitive plants may have several million cells. Plants have an alternation of generations where the sporophyte phase is succeeded by the gametophyte phase. The sporophyte phase produces spores within the sporangium by meiosis.

Flowering plants

Flowering plants are the dominant plant form on land and they reproduce by sexual and asexual means. Often their most distinguishing feature is their reproductive organs, commonly called flowers. The anther produces male gametophytes, the sperm is produced in pollen grains, which attach to the stigma on top of a carpel, in which the female gametophytes (inside ovules) are located. After the pollen tube grows through the carpel's style, the sex cell nuclei from the pollen grain migrate into the ovule to fertilize the egg cell and endosperm nuclei within the female gametophyte in a process termed double fertilization. The resulting zygote develops into an embryo, while the triploid endosperm (one sperm cell plus two female cells) and female tissues of the ovule give rise to the surrounding tissues in the developing seed. The ovary, which produced the female gametophyte(s), then grows into a fruit, which surrounds the seed(s). Plants may either self-pollinate or cross-pollinate. Nonflowering plants like ferns, moss and liverworts use other means of sexual reproduction.

Ferns

Ferns mostly produce large diploid sporophytes with rhizomes, roots and leaves; and on fertile leaves called sporangium, spores are produced. The spores are released and germinate to produce short, thin gametophytes that are typically heart shaped, small and green in color. The gametophytes or thallus, produce both motile sperm in the antheridia and egg cells in separate archegonia. After rains or when dew deposits a film of water, the motile sperm are splashed away from the antheridia, which are normally produced on the top side of the thallus, and swim in the film of water to the archegonia where they fertilize the egg. To promote out crossing or cross fertilization the sperm are released before the eggs are receptive of the sperm, making it more likely that the sperm will fertilize the eggs of different thallus. A zygote is formed after fertilization, which grows into a new sporophytic plant. The condition of having separate sporephyte and gametophyte plants is called alternation of generations. Other plants with similar reproductive means include the Psilotum, Lycopodium, Selaginella and Equisetum.

Bryophytes

The bryophytes, which include liverworts, hornworts and mosses, reproduce both sexually and vegetatively. They are small plants found growing in moist locations and like ferns, have motile sperm with flagella and need water to facilitate sexual reproduction. These plants start as a haploid spore that grows into the dominate form, which is a multicellular haploid body with leaf-like structures that photosynthesize. Haploid gametes are produced in antherida and archegonia by mitosis. The sperm released from the antherida respond to chemicals released by ripe archegonia and swim to them in a film of water and fertilize the egg cells thus producing a zygote. The zygote divides by mitotic division and grows into a sporophyte that is diploid. The multicellular diploid sporophyte produces structures called spore capsules, which are connected by seta to the archegonia. The spore capsules produce spores by meiosis, when ripe the capsules burst open and the spores are released. Bryophytes show considerable variation in their breeding structures and the above is a basic outline. Also in some species each plant is one sex while other species produce both sexes on the same plant.

Fungi

Main article: Mating in fungi For further information see Reproduction section of the Fungus article.Fungi are classified by the methods of sexual reproduction they employ. The outcome of sexual reproduction most often is the production of resting spores that are used to survive inclement times and to spread. There are typically three phases in the sexual reproduction of fungi: plasmogamy, karyogamy and meiosis.

Animals

See also: Fertilization in animals and Animal sexual behaviorInsects

For further information, see the subsection on Reproduction and development in the Insect article.

Insect species make up more than two-thirds of all extant animal species, and most insect species use sex for reproduction, though some species are facultatively parthenogenetic. Many species have sexual dimorphism, while in others the sexes look nearly identical. Typically they have two sexes with males producing spermatozoa and females ova. The ova develop into eggs that have a covering called the chorion, which forms before internal fertilization. Insects have very diverse mating and reproductive strategies most often resulting in the male depositing spermatophore within the female, which stores the sperm until she is ready for egg fertilization. After fertilization, and the formation of a zygote, and varying degrees of development; the eggs are deposited outside the female in many species, or in some, they develop further within the female and live born offspring are produced.

Mammals

Template:Mammalian reproduction There are three extant kinds of mammals: Monotremes, Placentals and Marsupials, all with internal fertilization. In placental mammals, offspring are born as juveniles: complete animals with the sex organs present although not reproductively functional. After several months or years, the sex organs develop further to maturity and the animal becomes sexually mature. Most female mammals are only fertile during certain periods during their estrous cycle, at which point they are ready to mate. Individual male and female mammals meet and carry out copulation. For most mammals, males and females exchange sexual partners throughout their adult lives.

Placental mammals

Male placental mammals

The mammalian male reproductive system contains two main divisions, the penis and the testicles, the latter of which is where sperm are produced. In humans, both of these organs are outside the abdominal cavity, but they can be primarily housed within the abdomen in other animals. For instance, a dog's penis is internal except when mating. Having the testicles outside the abdomen best facilitates temperature regulation of the sperm, which require specific temperatures to survive. The external location may also cause a reduction in the heat-induced contribution to the spontaneous mutation rate in male germinal tissue. Sperm are the smaller of the two gametes and are generally very short-lived, requiring males to produce them continuously from the time of sexual maturity until death. The produced sperm are stored in the epididymis until ejaculation. The sperm cells are motile and they swim using tail-like flagella to propel themselves towards the ovum. The sperm follows temperature gradients (thermotaxis) and chemical gradients (chemotaxis) to locate the ovum.

Female placental mammals

The mammalian female reproductive system likewise contains two main divisions: the vagina and uterus, which act as the receptacle for the sperm, and the ovaries, which produce the female's ova. All of these parts are always internal. The vagina is attached to the uterus through the cervix, while the uterus is attached to the ovaries via the Fallopian tubes. At certain intervals, the ovaries release an ovum, which passes through the fallopian tube into the uterus.

If, in this transit, it meets with sperm, the egg selects sperm with which to merge; this is termed fertilization. The fertilization usually occurs in the oviducts, but can happen in the uterus itself. The zygote then implants itself in the wall of the uterus, where it begins the processes of embryogenesis and morphogenesis. When developed enough to survive outside the womb, the cervix dilates and contractions of the uterus propel the fetus through the birth canal, which is the vagina.

The ova, which are the female sex cells, are much larger than the sperm and are normally formed within the ovaries of the fetus before its birth. They are mostly fixed in location within the ovary until their transit to the uterus, and contain nutrients for the later zygote and embryo. Over a regular interval, in response to hormonal signals, a process of oogenesis matures one ovum which is released and sent down the Fallopian tube. If not fertilized, this egg is released through menstruation in humans and other great apes, and reabsorbed in other mammals in the estrus cycle.

Gestation

Gestation, called pregnancy in humans, is the period of time during which the fetus develops, dividing via mitosis inside the female. During this time, the fetus receives all of its nutrition and oxygenated blood from the female, filtered through the placenta, which is attached to the fetus' abdomen via an umbilical cord. This drain of nutrients can be quite taxing on the female, who is required to ingest slightly higher levels of calories. In addition, certain vitamins and other nutrients are required in greater quantities than normal, often creating abnormal eating habits. The length of gestation, called the gestation period, varies greatly from species to species; it is 40 weeks in humans, 56–60 in giraffes and 16 days in hamsters.

Birth

Main article: BirthOnce the fetus is sufficiently developed, chemical signals start the process of birth, which begins with contractions of the uterus and the dilation of the cervix. The fetus then descends to the cervix, where it is pushed out into the vagina, and eventually out of the female. The newborn, which is called an infant in humans, should typically begin respiration on its own shortly after birth. Not long after, the placenta is passed as well. Most mammals eat this, as it is a good source of protein and other vital nutrients needed for caring for the young. The end of the umbilical cord attached to the young's abdomen eventually falls off on its own.

Monotremes

Main article: MonotremeMonotremes, only five species of which exist, all from Australia and New Guinea, are mammals that lay eggs. They have one opening for excretion and reproduction called the cloaca. They hold the eggs internally for several weeks, providing nutrients, and then lay them and cover them like birds. After less than two weeks the young hatches and crawls into its mother's pouch, much like marsupials, where it nurses for several weeks as it grows.

Marsupials

Main article: Marsupial reproductive system Infraclass of mammals in the clade Metatheria This article is about the mammals. For frogs, see Marsupial frog.

| Marsupials Temporal range: Paleocene–Recent PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N Possible Late Cretaceous records | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from left: eastern grey kangaroo, Virginia opossum, long-nosed bandicoot, monito del monte and Tasmanian devil representing the orders Diprotodontia, Didelphimorphia, Peramelemorphia, Microbiotheria and Dasyuromorphia respectively | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Clade: | Marsupialiformes |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia Illiger, 1811 |

| Orders | |

| |

| Present-day distribution of marsupials Introduced Native | |

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of the defining features of marsupials is their unique reproductive strategy, where the young are born in a relatively undeveloped state and then nurtured within a pouch on their mother's abdomen.

Living marsupials encompass a wide range of species, including kangaroos, koalas, opossums, possums, Tasmanian devils, wombats, wallabies, and bandicoots, among others.

Marsupials constitute a clade stemming from the last common ancestor of extant Metatheria, which encompasses all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. This evolutionary split between placentals and marsupials occurred at least 125 million years ago, possibly dating back over 160 million years to the Middle Jurassic-Early Cretaceous period.

Presently, close to 70% of the 334 extant species of marsupials are concentrated on the Australian continent, including mainland Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and nearby islands. The remaining 30% are distributed across the Americas, primarily in South America, with thirteen species in Central America and a single species, the Virginia opossum, inhabiting North America north of Mexico.

Marsupials range in size from a few grams in the long-tailed planigale, to several tonnes in the extinct Diprotodon.

The word marsupial comes from marsupium, the technical term for the abdominal pouch. It, in turn, is borrowed from the Latin marsupium and ultimately from the ancient Greek μάρσιππος mársippos, meaning "pouch".

Anatomy

(Phascolarctos cinereus)

Marsupials have the typical characteristics of mammals—e.g., mammary glands, three middle ear bones, (and ears that usually have tragi, varying in hearing thresholds) and true hair. There are, however, striking differences as well as a number of anatomical features that separate them from eutherians.

Most female marsupials have a front pouch, which contains multiple teats for the sustenance of their young. Marsupials also have other common structural features. Ossified patellae are absent in most modern marsupials (though a small number of exceptions are reported) and epipubic bones are present. Marsupials (and monotremes) also lack a gross communication (corpus callosum) between the right and left brain hemispheres.

Skull and teeth

Marsupials exhibit distinct cranial features compared to placentals. Generally, their skulls are relatively small and compact. Notably, they possess frontal holes known as foramen lacrimale situated at the front of the orbit. Marsupials also have enlarged cheekbones that extend further to the rear, and their lower jaw's angular extension (processus angularis) is bent inward toward the center. The hard palate of marsupials contains more openings compared to placentals.

Teeth in marsupials also differ significantly from those in placentals. For instance, most Australian marsupials outside the order Diprotodontia have a varying number of incisors between their upper and lower jaws. Early marsupials had a dental formula of 5.1.3.4/4.1.3.4 per quadrant, consisting of five (maxillary) or four (mandibular) incisors, one canine, three premolars, and four molars, totaling 50 teeth. While some taxa, like the opossum, retain this original tooth count, others have reduced numbers.

For instance, members of the Macropodidae family, including kangaroos and wallabies, have a dental formula of 3/1 – (0 or 1)/0 – 2/2 – 4/4. Many marsupials typically have between 40 and 50 teeth, which is notably more than most placentals. Notably, in marsupials, the second set of teeth only grows in at the site of the third premolar and posteriorly; all teeth anterior to this erupt initially as permanent teeth.

Torso

Few general characteristics describe their skeleton. In addition to unique details in the construction of the ankle, epipubic bones (ossa epubica) are observed projecting forward from the pubic bone of the pelvis. Since these are present in males and pouchless species, it is believed that they originally had nothing to do with reproduction, but served in the muscular approach to the movement of the hind limbs. This could be explained by an original feature of mammals, as these epipubic bones are also found in monotremes. Marsupial reproductive organs differ from the placentals. For them, the reproductive tract is doubled. The females have two uteri and two vaginas, and before birth, a birth canal forms between them, the median vagina. In most species, males have a split or double penis lying in front of the scrotum, which is not homologous to the scrotum of placentals.

A pouch is present in most, but not all, species. Many marsupials have a permanent bag, whereas in others the pouch develops during gestation, as with the shrew opossum, where the young are hidden only by skin folds or in the fur of the mother. The arrangement of the pouch is variable to allow the offspring to receive maximum protection. Locomotive kangaroos have a pouch opening at the front, while many others that walk or climb on all fours have the opening in the back. Usually, only females have a pouch, but the male water opossum has a pouch that is used to accommodate his genitalia while swimming or running.

General and convergences

The sugar glider, a marsupial, (left) and flying squirrel, a placental, (right) are examples of convergent evolution.

The sugar glider, a marsupial, (left) and flying squirrel, a placental, (right) are examples of convergent evolution.

Marsupials have adapted to many habitats, reflected in the wide variety in their build. The largest living marsupial, the red kangaroo, grows up to 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) in height and 90 kilograms (200 lb) in weight, but extinct genera, such as Diprotodon, were significantly larger and heavier. The smallest members of this group are the marsupial mice, which often reach only 5 centimetres (2.0 in) in body length.

Some species resemble placentals and are examples of convergent evolution. This convergence is evident in both brain evolution and behaviour. The extinct thylacine strongly resembled the placental wolf, hence one of its nicknames "Tasmanian wolf". The ability to glide evolved in both marsupials (as with sugar gliders) and some placentals (as with flying squirrels), which developed independently. Other groups such as the kangaroo, however, do not have clear placental counterparts, though they share similarities in lifestyle and ecological niches with ruminants.

Body temperature

Marsupials, along with monotremes (platypuses and echidnas), typically have lower body temperatures than similarly sized placentals (eutherians), with the averages being 35 °C (95 °F) for marsupials and 37 °C (99 °F) for placentals. Some species will bask to conserve energy

Reproductive system

See also: Kangaroo § Reproduction and life cycle

Marsupials' reproductive systems differ markedly from those of placentals. During embryonic development, a choriovitelline placenta forms in all marsupials. In bandicoots, an additional chorioallantoic placenta forms, although it lacks the chorionic villi found in eutherian placentas.

The evolution of reproduction in marsupials, and speculation about the ancestral state of mammalian reproduction, have engaged discussion since the end of the 19th century. Both sexes possess a cloaca, although modified by connecting to a urogenital sac and having a separate anal region in most species. The bladder of marsupials functions as a site to concentrate urine and empties into the common urogenital sinus in both females and males.

Male reproductive system

Most male marsupials, except for macropods and marsupial moles, have a bifurcated penis, separated into two columns, so that the penis has two ends corresponding to the females' two vaginas. The penis is used only during copulation, and is separate from the urinary tract. It curves forward when erect, and when not erect, it is retracted into the body in an S-shaped curve. Neither marsupials nor monotremes possess a baculum. The shape of the glans penis varies among marsupial species.

The male thylacine had a pouch that acted as a protective sheath, covering his external reproductive organs while running through thick brush.

The shape of the urethral grooves of the males' genitalia is used to distinguish between Monodelphis brevicaudata, Monodelphis domestica, and Monodelphis americana. The grooves form two separate channels that form the ventral and dorsal folds of the erectile tissue. Several species of dasyurid marsupials can also be distinguished by their penis morphology. The only accessory sex glands marsupials possess are the prostate and bulbourethral glands. Male marsupials have one to three pairs of bulbourethral glands. There are no ampullae of vas deferens, seminal vesicles or coagulating glands. The prostate is proportionally larger in marsupials than in placentals. During the breeding season, the male tammar wallaby's prostate and bulbourethral gland enlarge. However, there does not appear to be any seasonal difference in the weight of the testes.

Female reproductive system

See also: Birth § Marsupials

Female marsupials have two lateral vaginas, which lead to separate uteri, but both open externally through the same orifice. A third canal, the median vagina, is used for birth. This canal can be transitory or permanent. Some marsupial species are able to store sperm in the oviduct after mating.

Marsupials give birth at a very early stage of development; after birth, newborn marsupials crawl up the bodies of their mothers and attach themselves to a teat, which is located on the underside of the mother, either inside a pouch called the marsupium, or open to the environment. Mothers often lick their fur to leave a trail of scent for the newborn to follow to increase chances of making it into the marsupium. There they remain for a number of weeks, attached to the teat. The offspring are eventually able to leave the marsupium for short periods, returning to it for warmth, protection, and nourishment.

Early development

Prenatal development differs between marsupials and placentals. Key aspects of the first stages of placental embryo development, such as the inner cell mass and the process of compaction, are not found in marsupials. The cleavage stages of marsupial development are very variable between groups and aspects of marsupial early development are not yet fully understood.

An infant marsupial is known as a joey. Marsupials have a very short gestation period—usually between 12.5 and 33 days, but as low as 10.7 days in the case of the stripe-faced dunnart and as long as 38 days for the long-nosed potoroo. The joey is born in an essentially fetal state, equivalent to an 8–12 week human fetus, blind, furless, and small in comparison to placental newborns with sizes ranging from 4g to over 800g. A newborn marsupial can be arranged into one of three grades of developmental complexity. Those who are the least developed at birth are found in dasyurids, intermediate ones are found in didelphids and peramelids, and the most developed are in macropods. Despite the lack of development it crawls across its mother's fur to make its way into the pouch, which acts like an external womb, where it latches onto a teat for food. It will not re-emerge for several months, during which time it is fully reliant on its mother's milk for essential nutrients, growth factors and immunological defence. Genes expressed in the eutherian placenta that are important for the later stages of fetal development are in female marsupials expressed in their mammary glands during their lactation period instead. After this period, the joey begins to spend increasing lengths of time out of the pouch, feeding and learning survival skills. However, it returns to the pouch to sleep, and if danger threatens, it will seek refuge in its mother's pouch for safety.

An early birth removes a developing marsupial from its mother's body much sooner than in placentals; thus marsupials have not developed a complex placenta to protect the embryo from its mother's immune system. Though early birth puts the tiny newborn marsupial at greater environmental risk, it significantly reduces the dangers associated with long pregnancies, as there is no need to carry a large fetus to a full term in bad seasons. Marsupials are extremely altricial animals, needing to be intensely cared for immediately following birth (cf. precocial). Newborn marsupials lack histologically mature immune tissues and are highly reliant on their mother's immune system for immunological protection, as well as the milk.

Newborn marsupials must climb up to their mother's teats and their front limbs and facial structures are much more developed than the rest of their bodies at the time of birth. This requirement has been argued to have resulted in the limited range of locomotor adaptations in marsupials compared to placentals. Marsupials must develop grasping forepaws during their early youth, making the evolutive transition from these limbs into hooves, wings, or flippers, as some groups of placentals have done, more difficult. However, several marsupials do possess atypical forelimb morphologies, such as the hooved forelimbs of the pig-footed bandicoot, suggesting that the range of forelimb specialization is not as limited as assumed.

Joeys stay in the pouch for up to a year in some species, or until the next joey is born. A marsupial joey is unable to regulate its body temperature and relies upon an external heat source. Until the joey is well-furred and old enough to leave the pouch, a pouch temperature of 30–32 °C (86–90 °F) must be constantly maintained.

Joeys are born with "oral shields", which consist of soft tissue that reduces the mouth opening to a round hole just large enough to accept the mother's teat. Once inside the mouth, a bulbous swelling on the end of the teat attaches it to the offspring till it has grown large enough to let go. In species without pouches or with rudimentary pouches these are more developed than in forms with well-developed pouches, implying an increased role in maintaining the young attached to the mother's teat.

Geography

In Australasia, marsupials are found in Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea; throughout the Maluku Islands, Timor and Sulawesi to the west of New Guinea, and in the Bismarck Archipelago (including the Admiralty Islands) and Solomon Islands to the east of New Guinea.

In the Americas, marsupials are found throughout South America, excluding the central/southern Andes and parts of Patagonia; and through Central America and south-central Mexico, with a single species (the Virginia opossum Didelphis virginiana) widespread in the eastern United States and along the Pacific coast.

Interaction with Europeans

The first American marsupial (and marsupial in general) that a European encountered was the common opossum. Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, commander of the Niña on Christopher Columbus' first voyage in the late fifteenth century, collected a female opossum with young in her pouch off the South American coast. He presented them to the Spanish monarchs, though by then the young were lost and the female had died. The animal was noted for its strange pouch or "second belly", and how the offspring reached the pouch was a mystery.

On the other hand, it was the Portuguese who first described Australasian marsupials. António Galvão, a Portuguese administrator in Ternate (1536–1540), wrote a detailed account of the northern common cuscus (Phalanger orientalis):

Some animals resemble ferrets, only a little bigger. They are called Kusus. They have a long tail with which they hang from the trees in which they live continuously, winding it once or twice around a branch. On their belly they have a pocket like an intermediate balcony; as soon as they give birth to a young one, they grow it inside there at a teat until it does not need nursing anymore. As soon as she has borne and nourished it, the mother becomes pregnant again.

From the start of the 17th century, more accounts of marsupials arrived. For instance, a 1606 record of an animal, killed on the southern coast of New Guinea, described it as "in the shape of a dog, smaller than a greyhound", with a snakelike "bare scaly tail" and hanging testicles. The meat tasted like venison, and the stomach contained ginger leaves. This description appears to closely resemble the dusky pademelon (Thylogale brunii), in which case this would be the earliest European record of a member of the kangaroo family (Macropodidae).

Taxonomy

Marsupials are taxonomically identified as members of mammalian infraclass Marsupialia, first described as a family under the order Pollicata by German zoologist Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger in his 1811 work Prodromus Systematis Mammalium et Avium. However, James Rennie, author of The Natural History of Monkeys, Opossums and Lemurs (1838), pointed out that the placement of five different groups of mammals – monkeys, lemurs, tarsiers, aye-ayes and marsupials (with the exception of kangaroos, that were placed under the order Salientia) – under a single order (Pollicata) did not appear to have a strong justification. In 1816, French zoologist George Cuvier classified all marsupials under the order Marsupialia. In 1997, researcher J. A. W. Kirsch and others accorded infraclass rank to Marsupialia.

Classification

With seven living orders in total, Marsupialia is further divided as follows: † – Extinct

- Superorder Ameridelphia (American marsupials)

- Order Didelphimorphia (93 species) – see list of didelphimorphs

- Family Didelphidae: opossums

- Order Paucituberculata (seven species)

- Family Caenolestidae: shrew opossums

- Order Didelphimorphia (93 species) – see list of didelphimorphs

- Superorder Australidelphia (Australian marsupials)

- Order Microbiotheria (one extant species)

- Family Microbiotheriidae: monitos del monte

- Order †Yalkaparidontia (incertae sedis)

- Grandorder Agreodontia

- Order Dasyuromorphia (73 species) – see list of dasyuromorphs

- Family †Thylacinidae: thylacine

- Family Dasyuridae: antechinuses, quolls, dunnarts, Tasmanian devil, and relatives

- Family Myrmecobiidae: numbat

- Order Notoryctemorphia (two species)

- Family Notoryctidae: marsupial moles

- Order Peramelemorphia (27 species)

- Family Thylacomyidae: bilbies

- Family †Chaeropodidae: pig-footed bandicoots

- Family Peramelidae: bandicoots and allies

- Order Dasyuromorphia (73 species) – see list of dasyuromorphs

- Order Diprotodontia (136 species) – see list of diprotodonts

- Suborder Vombatiformes

- Family Vombatidae: wombats

- Family Phascolarctidae: koalas

- Family † Diprotodontidae

- Family † Palorchestidae: marsupial tapirs

- Family † Thylacoleonidae: marsupial lions

- Suborder Phalangerida

- Infraorder Phalangeriformes – see list of phalangeriformes

- Family Acrobatidae: feathertail glider and feather-tailed possum

- Family Burramyidae: pygmy possums

- Family †Ektopodontidae: sprite possums

- Family Petauridae: striped possum, Leadbeater's possum, yellow-bellied glider, sugar glider, mahogany glider, squirrel glider

- Family Phalangeridae: brushtail possums and cuscuses

- Family Pseudocheiridae: ringtailed possums and relatives

- Family Tarsipedidae: honey possum

- Infraorder Macropodiformes – see list of macropodiformes

- Family Macropodidae: kangaroos, wallabies, and relatives

- Family Potoroidae: potoroos, rat kangaroos, bettongs

- Family Hypsiprymnodontidae: musky rat-kangaroo

- Family † Balbaridae: basal quadrupedal kangaroos

- Infraorder Phalangeriformes – see list of phalangeriformes

- Suborder Vombatiformes

- Order Microbiotheria (one extant species)

Evolutionary history

See also: Metatheria, Evolution of Macropodidae, and Evolution of mammalsComprising over 300 extant species, several attempts have been made to accurately interpret the phylogenetic relationships among the different marsupial orders. Studies differ on whether Didelphimorphia or Paucituberculata is the sister group to all other marsupials. Though the order Microbiotheria (which has only one species, the monito del monte) is found in South America, morphological similarities suggest it is closely related to Australian marsupials. Molecular analyses in 2010 and 2011 identified Microbiotheria as the sister group to all Australian marsupials. However, the relations among the four Australidelphid orders are not as well understood.

| Cladogram of Marsupialia by Upham et al. 2019 & Álvarez-Carretero et al. 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Cladogram of Marsupialia by Gallus et al. 2015 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DNA evidence supports a South American origin for marsupials, with Australian marsupials arising from a single Gondwanan migration of marsupials from South America, across Antarctica, to Australia. There are many small arboreal species in each group. The term "opossum" is used to refer to American species (though "possum" is a common abbreviation), while similar Australian species are properly called "possums".

The relationships among the three extant divisions of mammals (monotremes, marsupials, and placentals) were long a matter of debate among taxonomists. Most morphological evidence comparing traits such as number and arrangement of teeth and structure of the reproductive and waste elimination systems as well as most genetic and molecular evidence favors a closer evolutionary relationship between the marsupials and placentals than either has with the monotremes.

The ancestors of marsupials, part of a larger group called metatherians, probably split from those of placentals (eutherians) during the mid-Jurassic period, though no fossil evidence of metatherians themselves are known from this time. From DNA and protein analyses, the time of divergence of the two lineages has been estimated to be around 100 to 120 mya. Fossil metatherians are distinguished from eutherians by the form of their teeth; metatherians possess four pairs of molar teeth in each jaw, whereas eutherian mammals (including true placentals) never have more than three pairs. Using this criterion, the earliest known metatherian was thought to be Sinodelphys szalayi, which lived in China around 125 mya. However Sinodelphys was later reinterpreted as an early member of Eutheria. The unequivocal oldest known metatherians are now 110 million years old fossils from western North America. Metatherians were widespread in North America and Asia during the Late Cretaceous, but suffered a severe decline during the end-Cretaceous extinction event.

Cladogram from Wilson et al. (2016)

| Metatheria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2022, a study provided strong evidence that the earliest known marsupial was Deltatheridium known from specimens from the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous in Mongolia. This study placed both Deltatheridium and Pucadelphys as sister taxa to the modern large American opossums.

Marsupials spread to South America from North America during the Paleocene, possibly via the Aves Ridge. Northern Hemisphere metatherians, which were of low morphological and species diversity compared to contemporary placental mammals, eventually became extinct during the Miocene epoch.

In South America, the opossums evolved and developed a strong presence, and the Paleogene also saw the evolution of shrew opossums (Paucituberculata) alongside non-marsupial metatherian predators such as the borhyaenids and the saber-toothed Thylacosmilus. South American niches for mammalian carnivores were dominated by these marsupial and sparassodont metatherians, which seem to have competitively excluded South American placentals from evolving carnivory. While placental predators were absent, the metatherians did have to contend with avian (terror bird) and terrestrial crocodylomorph competition. Marsupials were excluded in turn from large herbivore niches in South America by the presence of native placental ungulates (now extinct) and xenarthrans (whose largest forms are also extinct). South America and Antarctica remained connected until 35 mya, as shown by the unique fossils found there. North and South America were disconnected until about three million years ago, when the Isthmus of Panama formed. This led to the Great American Interchange. Sparassodonts disappeared for unclear reasons – again, this has classically assumed as competition from carnivoran placentals, but the last sparassodonts co-existed with a few small carnivorans like procyonids and canines, and disappeared long before the arrival of macropredatory forms like felines, while didelphimorphs (opossums) invaded Central America, with the Virginia opossum reaching as far north as Canada.

Marsupials reached Australia via Antarctica during the Early Eocene, around 50 mya, shortly after Australia had split off. This suggests a single dispersion event of just one species, most likely a relative to South America's monito del monte (a microbiothere, the only New World australidelphian). This progenitor may have rafted across the widening, but still narrow, gap between Australia and Antarctica. The journey must not have been easy; South American ungulate and xenarthran remains have been found in Antarctica, but these groups did not reach Australia.

In Australia, marsupials radiated into the wide variety seen today, including not only omnivorous and carnivorous forms such as were present in South America, but also into large herbivores. Modern marsupials appear to have reached the islands of New Guinea and Sulawesi relatively recently via Australia. A 2010 analysis of retroposon insertion sites in the nuclear DNA of a variety of marsupials has confirmed all living marsupials have South American ancestors. The branching sequence of marsupial orders indicated by the study puts Didelphimorphia in the most basal position, followed by Paucituberculata, then Microbiotheria, and ending with the radiation of Australian marsupials. This indicates that Australidelphia arose in South America, and reached Australia after Microbiotheria split off.

In Australia, terrestrial placentals disappeared early in the Cenozoic (their most recent known fossils being 55 million-year-old teeth resembling those of condylarths) for reasons that are not clear, allowing marsupials to dominate the Australian ecosystem. Extant native Australian terrestrial placentals (such as hopping mice) are relatively recent immigrants, arriving via island hopping from Southeast Asia.

Genetic analysis suggests a divergence date between the marsupials and the placentals at 160 million years ago. The ancestral number of chromosomes has been estimated to be 2n = 14.

A recent hypothesis suggests that South American microbiotheres resulted from a back-dispersal from eastern Gondwana. This interpretation is based on new cranial and post-cranial marsupial fossils of Djarthia murgonensis from the early Eocene Tingamarra Local Fauna in Australia that indicate this species is the most plesiomorphic ancestor, the oldest unequivocal australidelphian, and may be the ancestral morphotype of the Australian marsupial radiation.

In 2023, imaging of a partial skeleton found in Australia by paleontologists from Flinders University led to the identification of Ambulator keanei, the first long-distance walker in Australia.

See also

Notes

- This is supported by the find of Eocene fossil remains of an australidelphian, the microbiotherian Woodburnodon casei, on the Antarctic peninsula,

- Ratites may have similarly traveled overland from South America to colonise Australia; a fossil ratite is known from Antarctica, and South American rheas are more basal within the group than Australo-Pacific ratites.

References

- Lodé, Thierry (2011). "Sex is not a solution for reproduction: the libertine bubble theory". BioEssays. 33 (6): 419–422. doi:10.1002/bies.201000125. PMID 21472739.

- Lodé, Thierry (2012). "Sex and the origin of genetic exchanges". Trends in Evolutionary Biology. 4. doi:10.4081/eb.2012.e1.

- ^ Michod, RE; Bernstein, H; Nedelcu, AM (2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens" (PDF). Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 8 (3): 267–85. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- Lodé, T (2012). "Have Sex or Not? Lessons from Bacteria". Sexual development : genetics, molecular biology, evolution, endocrinology, embryology, and pathology of sex determination and differentiation. 6 (6): 325–8. doi:10.1159/000342879. PMID 22986519.

- Krebs, JE; Goldstein, ES; Kilpatrick, ST (2011). Lewin's GENES X. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. pp. 289–292. ISBN 978076376632.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Bernstein, Harris; Bernstein, Carol (2010). "Evolutionary Origin of Recombination during Meiosis". BioScience. 60 (7): 498. doi:10.1525/bio.2010.60.7.5.

- Lorenz, MG; Wackernagel, W (1994). "Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment". Microbiological reviews. 58 (3): 563–602. PMC 372978. PMID 7968924.

- ^ Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Michod RE. (2012) "DNA Repair as the Primary Adaptive Function of Sex in Bacteria and Eukaryotes". Chapter 1, pp. 1–50, in DNA Repair: New Research, Editors S. Kimura and Shimizu S. Nova Sci. Publ., Hauppauge, New York. Open access for reading only. ISBN 978-1-62100-756-2

- N.J. Buttefield (2000). "Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes". Paleobiology. 26 (3): 386–404. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01814.x , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01814.xinstead. - Kleiman, Maya; Tannenbaum, Emmanuel (2009). "Diploidy and the selective advantage for sexual reproduction in unicellular organisms". Theory in Biosciences. 128 (4): 249–85. doi:10.1007/s12064-009-0077-9. PMID 19902285.

- Jon Lovett Doust; Lesley Lovett Doust (1988). Plant Reproductive Ecology: Patterns and Strategies. Oxford University Press. p. 290. ISBN 9780195063943.

- Reichard, U.H. (2002). "Monogamy—A variable relationship" (PDF). Max Planck Research. 3: 62–7. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Lipton, Judith Eve; Barash, David P. (2001). The Myth of Monogamy: Fidelity and Infidelity in Animals and People. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-4004-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Research conducted by Patricia Adair Gowaty. Reported by Morell, V. (1998). "Evolution of sex: A new look at monogamy". Science. 281 (5385): 1982–1983. doi:10.1126/science.281.5385.1982. PMID 9767050.

- Baltz, RH; Bingham, PM; Drake, JW (1976). "Heat mutagenesis in bacteriophage T4: The transition pathway". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 73 (4): 1269–73. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.1269B. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.4.1269. PMC 430244. PMID 4797.

- Bahat, Anat; Tur-Kaspa, Ilan; Gakamsky, Anna; Giojalas, Laura C.; Breitbart, Haim; Eisenbach, Michael (2003). "Thermotaxis of mammalian sperm cells: A potential navigation mechanism in the female genital tract". Nature Medicine. 9 (2): 149–50. doi:10.1038/nm0203-149. PMID 12563318.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - Baker, Andrew M. (2021-04-27). "Meet 5 of Australia's tiniest mammals, who tread a tightrope between life and death every night". The Conversation. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- Wroe, S.; Crowther, M.; Dortch, J.; Chong, J. (2004). "The size of the largest marsupial and why it matters". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (Suppl 3): S34 – S36. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0095. PMC 1810005. PMID 15101412.

- Stannard HJ, Dennington K, Old JM (2020). "The external ear morphology and presence of tragi in Australian marsupials". Ecology and Evolution. 10 (18): 9853–9866. Bibcode:2020EcoEv..10.9853S. doi:10.1002/ece3.6634. PMC 7520188. PMID 33005349.

- Old JM, Parsons CL, Tulk, ML (2020). "Hearing thresholds of small native Australian mammals - red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura), kultarr (Antechinomys laniger) and spinifex hopping-mice (Notomys Alexis)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 190: 342–351. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa003.

- Feldhamer GA, Drickamer LC, Vessey SH, Merritt JF, Krajewski C (2007). Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9. OCLC 124031907.

- Samuels ME, Regnault S, Hutchinson JR (2017). "Evolution of the patellar sesamoid bone in mammals". PeerJ. 5: e3103. doi:10.7717/peerj.3103. PMC 5363259. PMID 28344905.

- ^ Nowak 1999. sfn error: no target: CITEREFNowak1999 (help)

- ^ Renfree M, Tyndale-Biscoe H (1987). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521337922.

- Armati, Patricia J.; Dickman, Chris R.; Hume, Ian D. (2006-08-17). Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45742-2.

- Todorov OS, Blomberg SP, Goswami A, Sears K, Drhlík P, Peters J, Weisbecker V (March 2021). "Testing hypotheses of marsupial brain size variation using phylogenetic multiple imputations and a Bayesian comparative framework". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 288 (1947): 20210394. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.0394. PMC 8059968. PMID 33784860.

- Todorov OS (2019). "Marsupial Cognition". In Vonk J, Shackelford T (eds.). Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–8. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1167-1. ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6. S2CID 242256517.

- Gaughan, John B.; Hogan, Lindsay A.; Wallage, Andrea (2015). Abstract: Thermoregulation in marsupials and monotremes, chapter of Marsupials and monotremes: nature's enigmatic mammals. Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated. ISBN 9781634834872. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- White (1999). "Thermal Biology of the Platypus". Davidson College. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2006.

- "Control Systems Part 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Stannard, Hayley J.; Fabian, Megan; Old, Julie M. (2015). "To bask or not to bask: Behavioural thermoregulation in two species of dasyurid, Phascogale calura and Antechinomys laniger". Journal of Thermal Biology. 53: 66–71. Bibcode:2015JTBio..53...66S. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2015.08.012. PMID 26590457.

- Short RV, Balaban E (1994). The Differences Between the Sexes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44878-9.

- ^ King A (2001). "Discoveries about Marsupial Reproduction". Iowa State University Biology Dept. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 396–399. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- Staker L (30 June 2014). Macropod Husbandry, Healthcare and Medicinals—Volumes One and Two. Lynda Staker. ISBN 978-0-9775751-2-1.

- On the Habits and Affinities of the New Australian Mammal, Notoryctes typhlops E. D. Cope The American Naturalist Vol. 26, No. 302 (February 1892), pp. 121–128

- ^ Hunsaker II D (1977). The Biology of Marsupials. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-323-14620-3.

- Setchell BP (1977). "Reproduction in male marsupials". The Biology of Marsupials. pp. 411–457. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-02721-7_24. ISBN 978-1-349-02723-1.

- Sharman GB, Pilton PE (1964). "The life history and reproduction of the red kangaroo (Megaleia rufa)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 142 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1964.tb05152.x.

- Sadleir RM (1965). "Reproduction in two species of kangaroo (Macropus robustus and Megaleia rufa in the arid Pilbara region of Western Australia". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 145 (2): 239–261. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1965.tb02016.x.

- Sadleir R (1973). The Reproduction of Vertebrates. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-323-15935-7.

- Australian Mammal Society (1978). Australian Mammal Society. Australian Mammal Society. pp. 73–.

- Osgood WH, Herrick CJ (1921). A monographic study of the American marsupial, Caēnolestes ... University of Chicago. pp. 64–.

- The Urologic and Cutaneous Review. Urologic & Cutaneous Press. 1920. pp. 677–.

- Paddle R (2002). The last Tasmanian tiger : the history and extinction of the thylacine (Paperback ed.). Port Melbourne, Vic.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53154-2.

- Nogueira J, Castro AS, Câamara EC, Câmara BO (2004). "Morphology of the Male Genital system of Chironectes minimus and Comparison to other didelphid marsupials". Journal of Mammalogy. 85 (5): 834–841. doi:10.1644/207. S2CID 85595933.

- Woolley PA, Westerman M, Krajewski C (December 2007). "Interspecific Affinities within the Genus Sminthopsis (Dasyuromorphia: Dasyuridae) Based on Morphology of the Penis: Congruence with Other Anatomical and Molecular Data". Journal of Mammalogy. 88 (6): 1381–1392. doi:10.1644/06-mamm-a-443r.1. ISSN 0022-2372.

- Rodger JC, Hughes RL (1973). "Studies of the accessory glands of male marsupials". Australian Journal of Zoology. 21 (3): 303. doi:10.1071/ZO9730303. hdl:1959.4/70011.

- Vogelnest L, Portas T (2019-05-01). Current Therapy in Medicine of Australian Mammals. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4863-0753-1.

- Rodger JC (January 1976). "Comparative aspects of the accessory sex glands and seminal biochemistry of mammals". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. B, Comparative Biochemistry. 55 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(76)90164-4. PMID 780045.

- Inns RW (November 1982). "Seasonal changes in the accessory reproductive system and plasma testosterone levels of the male tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii, in the wild". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 66 (2): 675–680. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0660675. PMID 7175821.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (2005-09-12). Walker's Marsupials of the World. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8211-1.

- Plant TM, Zeleznik AJ (15 November 2014). Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-397769-4.

- ^ Stannard, Hayley J.; Old, Julie M. (2023). "Wallaby joeys and platypus puggles are tiny and undeveloped when born. But their mother's milk is near-magical". The Conversation.

- ^ Stannard, Hayley J.; Miller, Robert D.; Old, Julie M. (2020). "Marsupial and monotreme milk – a review of its nutrients and immune properties". PeerJ. 8: e9335. doi:10.7717/peerj.9335. PMC 7319036. PMID 32612884.

- Frankenberg SR, de Barros FR, Rossant J, Renfree MB (2016). "The mammalian blastocyst". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Developmental Biology. 5 (2): 210–232. doi:10.1002/wdev.220. PMID 26799266. S2CID 22001725.

- ^ Smith, Kathleen K.; Keyte, Anna L. (2020). "Adaptations of the Marsupial Newborn: Birth as an Extreme Environment". The Anatomical Record. 303 (2): 235–249. doi:10.1002/ar.24049. PMID 30548826. S2CID 56484546.

- Drews, Barbara; Roellig, Kathleen; Menzies, Brandon R.; Shaw, Geoff; Buentjen, Ina; Herbert, Catherine A.; Hildebrandt, Thomas B.; Renfree, Marilyn B. (15 March 2013). "Ultrasonography of wallaby prenatal development shows that the climb to the pouch begins in utero". Scientific Reports. 3 (1458): 1458. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1458D. doi:10.1038/srep01458. PMC 3597997. PMID 23492830.

- Schneider, N. Y.; Gurovich, Y. (2017). "Morphology and evolution of the oral shield in marsupial neonates including the newborn monito del monte (Dromiciops gliroides, Marsupialia Microbiotheria) pouch young - PMC". Journal of Anatomy. 231 (1): 59–83. doi:10.1111/joa.12621. PMC 5472534. PMID 28620997.

- Dawkins, Richard; Wong, Yan (9 February 2005). The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780618619160 – via Google Books.

- Stannard HJ, Miller RD, Old JM (2020). "Marsupial and monotreme milk – a review of its nutrients and immune properties". PeerJ. 8: e9335. doi:10.7717/peerj.9335. PMC 7319036. PMID 32612884.

- kristac@stanford.edu, <img src='https://med stanford edu/news/media-contacts/krista_conger/_jcr_content/image img 620 high jpg/conger-krista-90 jpg' alt='Krista Conger'> Krista Conger Krista Conger is a senior science writer in the Office of Communications Email her at. "Baby marsupials 'drink' placenta to enhance development". News Center.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Old JM, Deane EM (2003). "The lymphoid and immunohaematopoietic tissues of the embryonic brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula)". Anatomy and Embryology. 206 (3): 193–197. doi:10.1007/s00429-002-0285-2. PMID 12592570. S2CID 546795.

- Old JM, Selwood L, Deane EM (2003). "A histological investigation of the lymphoid and immunohaematopoietic tissues of the adult stripe-faced dunnart (Sminthopsis macroura)". Cells Tissues Organs. 173 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1159/000068946. PMID 12649589. S2CID 46354564.

- Old JM, Selwood L, Deane EM (2003). "Development of the lymphoid tissues of the stripe-faced dunnart (Sminthopsis macroura)". Cells Tissues Organs. 175 (4): 192–201. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00310.x. PMC 1571326. PMID 15255959.

- Old JM, Deane EM (2000). "Development of the immune system and immunological protection in marsupial pouch young". Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 24 (5): 445–454. doi:10.1016/S0145-305X(00)00008-2. PMID 10785270.

- Sears KE (August 2009). "Differences in the timing of prechondrogenic limb development in mammals: the marsupial-placental dichotomy resolved". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 63 (8): 2193–2200. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00690.x. PMID 19453378. S2CID 42635687.

- Smith KK (2001). "Early development of the neural plate, neural crest and facial region of marsupials". Journal of Anatomy. 199 (Pt 1-2): 121–131. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19910121.x. PMC 1594995. PMID 11523813.

- Larry Vogelnest, Graeme Allan, Radiology of Australian Mammals

- Schneider NY (August 2011). "The development of the olfactory organs in newly hatched monotremes and neonate marsupials". Journal of Anatomy. 219 (2): 229–242. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01393.x. PMC 3162242. PMID 21592102.

- Ferner, K.; Schultz, J. A.; Zeller, U. (2017). "Comparative anatomy of neonates of the three major mammalian groups (monotremes, marsupials, placentals) and implications for the ancestral mammalian neonate morphotype - PMC". Journal of Anatomy. 231 (6): 798–822. doi:10.1111/joa.12689. PMC 5696127. PMID 28960296.

- ^ Tyndale-Biscoe H (2004). Life of Marsupials. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO. ISBN 978-0-643-06257-3.

- Krause WJ, Krause WA (2006). The Opossum: Its Amazing Story. Columbia, US: Dept. of Pathology of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Missouri. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-9785999-0-4.

- Dawson TJ (2012). Kangaroos (2nd ed.). Collingwood, US: CSIRO Publishing. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-643-10625-3.

- Martin WC (1841). A General Introduction to the Natural History of Mammiferous Animals. London, UK: Wright and Co. Printers. pp. 182–4.

- ^ Jackson S, Groves C (2015). Taxonomy of Australian Mammals. Australia: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 82–3. ISBN 978-1-4863-0014-3.

- "Mammals". vertlife.org. Retrieved 2024-11-12.

- Gardner, A. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Gallus S, Janke A, Kumar V, Nilsson MA (March 2015). "Disentangling the relationship of the Australian marsupial orders using retrotransposon and evolutionary network analyses". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (4): 985–992. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv052. PMC 4419798. PMID 25786431.

- Szalay F (1982). Archer M (ed.). "A new appraisal of marsupial phylogeny and classification". Carnivorous Marsupials. 2: 621–40.

- Upham, Nathan S.; Esselstyn, Jacob A.; Jetz, Walter (2019). "Inferring the mammal tree: Species-level sets of phylogenies for questions in ecology, evolution and conservation". PLOS Biol. 17 (12): e3000494. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000494. PMC 6892540. PMID 31800571.

- Upham, Nathan S.; Esselstyn, Jacob A.; Jetz, Walter (2019). "DR_on4phylosCompared_linear_richCol_justScale_ownColors_withTips_80in" (PDF). PLOS Biology. 17 (12): e3000494. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000494. PMC 6892540. PMID 31800571.

- Álvarez-Carretero, Sandra; Tamuri, Asif U.; Battini, Matteo; Nascimento, Fabrícia F.; Carlisle, Emily; Asher, Robert J.; Yang, Ziheng; Donoghue, Philip C.J.; dos Reis, Mario (2022). "A species-level timeline of mammal evolution integrating phylogenomic data". Nature. 602 (7896): 263–267. Bibcode:2022Natur.602..263A. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04341-1. hdl:1983/de841853-d57b-40d9-876f-9bfcf7253f12. PMID 34937052. S2CID 245438816.

- Álvarez-Carretero, Sandra; Tamuri, Asif U.; Battini, Matteo; Nascimento, Fabrícia F.; Carlisle, Emily; Asher, Robert J.; Yang, Ziheng; Donoghue, Philip C.J.; dos Reis, Mario (2022). "4705sp_colours_mammal-time.tree". Nature. 602 (7896): 263–267. Bibcode:2022Natur.602..263A. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04341-1. hdl:1983/de841853-d57b-40d9-876f-9bfcf7253f12. PMID 34937052. S2CID 245438816.

- ^ Schiewe J (28 July 2010). "Australia's marsupials originated in what is now South America, study says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ Nilsson MA, Churakov G, Sommer M, Tran NV, Zemann A, Brosius J, Schmitz J (July 2010). "Tracking marsupial evolution using archaic genomic retroposon insertions". PLOS Biology. 8 (7): e1000436. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000436. PMC 2910653. PMID 20668664.

- ^ Beck RM, Godthelp H, Weisbecker V, Archer M, Hand SJ (March 2008). Hawks J (ed.). "Australia's oldest marsupial fossils and their biogeographical implications". PLOS ONE. 3 (3): e1858. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1858B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001858. PMC 2267999. PMID 18365013.

- Moyal AM (2004). Platypus: The Extraordinary Story of How a Curious Creature Baffled the World. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8052-0.

- van Rheede T, Bastiaans T, Boone DN, Hedges SB, de Jong WW, Madsen O (March 2006). "The platypus is in its place: nuclear genes and indels confirm the sister group relation of monotremes and Therians". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (3): 587–597. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj064. PMID 16291999.

- Luo ZX, Yuan CX, Meng QJ, Ji Q (August 2011). "A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals". Nature. 476 (7361): 442–445. Bibcode:2011Natur.476..442L. doi:10.1038/nature10291. PMID 21866158. S2CID 205225806.

- Benton MJ (1997). Vertebrate Palaeontology. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-412-73810-4.

- Rincon P (12 December 2003). "Oldest Marsupial Ancestor Found". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- Luo ZX, Ji Q, Wible JR, Yuan CX (December 2003). "An Early Cretaceous tribosphenic mammal and metatherian evolution". Science. 302 (5652): 1934–1940. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1934L. doi:10.1126/science.1090718. PMID 14671295. S2CID 18032860.

- Hu Y, Meng J, Li C, Wang Y (January 2010). "New basal eutherian mammal from the Early Cretaceous Jehol biota, Liaoning, China". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 277 (1679): 229–236. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0203. PMC 2842663. PMID 19419990.

- Bi S, Zheng X, Wang X, Cignetti NE, Yang S, Wible JR (June 2018). "An Early Cretaceous eutherian and the placental-marsupial dichotomy". Nature. 558 (7710): 390–395. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..390B. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0210-3. PMID 29899454. S2CID 49183466.

- Bennett, C. Verity; Upchurch, Paul; Goin, Francisco J.; Goswami, Anjali (2018-02-06). "Deep time diversity of metatherian mammals: implications for evolutionary history and fossil-record quality". Paleobiology. 44 (2): 171–198. Bibcode:2018Pbio...44..171B. doi:10.1017/pab.2017.34. hdl:11336/94590. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 46796692.

- Wilson, G.P.; Ekdale, E.G.; Hoganson, J.W.; Calede, J.J.; Linden, A.V. (2016). "A large carnivorous mammal from the Late Cretaceous and the North American origin of marsupials". Nature Communications. 7. doi:10.1038/ncomms13734.

- Velazco, Paúl M; Buczek, Alexandra J; Hoffman, Eva; Hoffman, Devin K; O’Leary, Maureen A; Novacek, Michael J (30 January 2022). "Combined data analysis of fossil and living mammals: a Paleogene sister taxon of Placentalia and the antiquity of Marsupialia". Cladistics. 38 (3): 359–373. doi:10.1111/cla.12499. PMID 35098586. S2CID 246429311.

- Kemp, Thomas Stainforth (2005). The origin and evolution of mammals (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-19-850760-7.

- Boschman LM, van Hinsbergen DJ, Torsvik TH, Spakman W, Pindell JL (23 August 2014). "Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic". Earth-Science Reviews. 138: 102–136. Bibcode:2014ESRv..138..102B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.727.4858. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.08.007.

- Ali, Jason R.; Hedges, S. Blair (November 2021). Hoorn, Carina (ed.). "Colonizing the Caribbean: New geological data and an updated land-vertebrate colonization record challenge the GAARlandia land-bridge hypothesis". Journal of Biogeography. 48 (11): 2699–2707. Bibcode:2021JBiog..48.2699A. doi:10.1111/jbi.14234. ISSN 0305-0270. S2CID 238647106.

- Eldridge, Mark D B; Beck, Robin M D; Croft, Darin A; Travouillon, Kenny J; Fox, Barry J (2019-05-23). "An emerging consensus in the evolution, phylogeny, and systematics of marsupials and their fossil relatives (Metatheria)". Journal of Mammalogy. 100 (3): 802–837. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyz018. ISSN 0022-2372.

- Simpson GG (July 1950). "History of the Fauna of Latin America". American Scientist. 38 (3): 361–389, see p. 368. JSTOR 27826322. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- Prevosti FJ, Forasiepi A, Zimicz N (2011). "The Evolution of the Cenozoic Terrestrial Mammalian Predator Guild in South America: Competition or Replacement?". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20: 3–21. doi:10.1007/s10914-011-9175-9. hdl:11336/2663. S2CID 15751319.

- Goin FJ, Zimicz N, Reguero MA, Santillana SN, Marenssi SA, Moly JJ (2007). "New marsupial (Mammalia) from the Eocene of Antarctica, and the origins and affinities of the Microbiotheria". Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 62 (4): 597–603. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ^ Yonezawa T, Segawa T, Mori H, Campos PF, Hongoh Y, Endo H, et al. (January 2017). "Phylogenomics and Morphology of Extinct Paleognaths Reveal the Origin and Evolution of the Ratites". Current Biology. 27 (1): 68–77. Bibcode:2017CBio...27...68Y. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.029. PMID 27989673.

- Tambussi CP, Noriega JI, Gaździcki A, Tatur A, Reguero MA, Vizcaíno SF (1994). "Ratite bird from the Paleogene La Meseta Formation, Seymour Island, Antarctica" (PDF). Polish Polar Research. 15 (1–2): 15–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Bond M, Reguero MA, Vizcaíno SF, Marenssi SA (2006). "A new 'South American ungulate' (Mammalia: Litopterna) from the Eocene of the Antarctic Peninsula". In Francis JE, Pirrie D, Crame JA (eds.). Cretaceous-tertiary high-latitude palaeoenvironments: James Ross Basin, Antarctica. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. Vol. 258. The Geological Society of London. pp. 163–176. Bibcode:2006GSLSP.258..163B. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2006.258.01.12. S2CID 140546667.

- Bond M, Kramarz A, Macphee RD, Reguero M (2011). "A new astrapothere (Mammalia, Meridiungulata) from La Meseta Formation, Seymour (Marambio) Island, and a reassessment of previous records of Antarctic astrapotheres". American Museum Novitates (3718): 1–16. doi:10.1206/3718.2. hdl:11336/98139. S2CID 58908785. Archived from the original (PDF) on Sep 17, 2012.

- Gelfo JN, Mörs T, Lorente M, López GM, Reguero M (2014-07-16). "The oldest mammals from Antarctica, early Eocene of the La Meseta Formation, Seymour Island". Palaeontology. 58 (1): 101–110. doi:10.1111/pala.12121. Archived from the original on Apr 5, 2023.

- Davis SN, Torres CR, Musser GM, Proffitt JV, Crouch NM, Lundelius EL, et al. (2020). "New mammalian and avian records from the late Eocene La Meseta and Submeseta formations of Seymour Island, Antarctica". PeerJ. 8: e8268. doi:10.7717/peerj.8268. PMC 6955110. PMID 31942255.

- ^ Dawkins R (2005). The Ancestor's Tale : A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Boston: Mariner Books. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

- ^ Hand SJ, Long J, Archer M, Flannery TF (2002). Prehistoric mammals of Australia and New Guinea: one hundred million years of evolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7223-5.

- Kemp, T.S. (2005). The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850761-1.

- Graves JA, Renfree MB (2013)Marsupials in the age of genomics. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet

- Lu, Donna (2023-05-30). "Meet Australia's first long-distance walker: a 250kg marsupial with 'heeled hands'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

Further reading

- Austin CR, Short RV, eds. (21 March 1985). Reproduction in Mammals: Volume 4, Reproductive Fitness. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-521-31984-3.

- Bronson FH (1989). Mammalian Reproductive Biology. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07559-4.

- Dawson TJ (1995). Kangaroos: Biology of the Largest Marsupials. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8262-5.

- Flannery TF (2002). The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People. Grove Press. pp. 67–75. ISBN 978-0-8021-3943-6.

- Flannery TF (2008). Chasing kangaroos : a continent, a scientist, and a search for the world's most extraordinary creature (1st American ed.). New York: Grove. ISBN 9780802143716.

- Flannery TF (2005). Country : a continent, a scientist & a kangaroo (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Text Pub. ISBN 978-1-920885-76-2.

- Frith, H. J. and J. H. Calaby. Kangaroos. New York: Humanities Press, 1969.

- McKay G (2006). The Encyclopedia of MAMMALS. Weldon Owen. ISBN 978-1-74089-352-7.

- Hunsaker D (1977). The Biology of Marsupials. New York: Academic Press.

- Johnson MH, Everitt BJ (1988). Essential Reproduction. Blackwell Scientific. ISBN 978-0-632-02183-3.

- Jones M, Dickman C, Archer (2003). Predators with pouches : the biology of carnivorous marsupials. Collingwood, Victoria: Australia). ISBN 9780643066342.

- Knobill E, Neill JD, eds. (1998). Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Vol. 3. New York: Academic Press.

- McCullough DR, McCullough Y (2000). Kangaroos in Outback Australia: Comparative Ecology and Behavior of Three Coexisting Species. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11916-0.

- Nowak RM (7 April 1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Taylor AC, Taylor P (1997). "Sex of Pouch Young Related to Maternal Weight in Macropus eugeni and M. parma". Australian Journal of Zoology. 45 (6): 573–578. doi:10.1071/ZO97038.

External links

- "Western Australian Mammal Species". members.iinet.net.au. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- "Researchers Publish First Marsupial Genome Sequence". Genome.gov. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- First marsupial genome released. Most differences between the opossom and placental mammals stem from non-coding DNA Archived 4 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

| Geological time scale of marsupial evolution | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phanerozoic |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Extant mammal orders | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yinotheria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Theria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Marsupialia | |

Fish

Further information: ]The vast majority of fish species lay eggs that are then fertilized by the male, some species lay their eggs on a substrate like a rock or on plants, while others scatter their eggs and the eggs are fertilized as they drift or sink in the water column. Some fish species use internal fertilization and then disperse the developing eggs or give birth to live offspring. Fish that have live-bearing offspring include the Guppy and Mollies or Poecilia. Fishes that give birth to live young can be ovoviviparous, where the eggs are fertilized within the female and the eggs simply hatch within the female body, or in seahorses, the male carries the developing young within a pouch, and gives birth to live young. Fishes can also be viviparous, where the female supplies nourishment to the internally growing offspring. Some fish are hermaphrodites, where a single fish is both male and female and can produce eggs and sperm. In hermaphroditic fish, some are male and female at the same time while in other fish they are serially hermaphroditic; starting as one sex and changing to the other. In at least one hermaphroditic species, self-fertilization occurs when the eggs and sperm are released together. Internal self-fertilization may occur in some other species. One fish species does not reproduce by sexual reproduction but uses sex to produce offspring; Poecilia formosa is a unisex species that uses a form of parthenogenesis called gynogenesis, where unfertilized eggs develop into embryos that produce female offspring. Poecilia formosa mate with males of other fish species that use internal fertilization, the sperm does not fertilize the eggs but stimulates the growth of the eggs which develops into embryos.

See also

Template:Misplaced Pages books

- Anisogamy

- Asexual reproduction

- Biological reproduction

- Evolution of sexual reproduction

- Hermaphroditism

- Isogamy

- Mate choice

- Mating in fungi

- Meiosis

- Natural competence

- Operational sex ratio

- Sex

- Sex organ

- Sexual intercourse

Notes

- BONY FISHES - Reproduction

- M. Cavendish (2001). Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1252. ISBN 978-0-7614-7194-3.

-

E.F. Orlando, Y. Katsu, S. Miyagawa, T. Iguchi (2006). "Cloning and differential expression of estrogen receptor and aromatase genes in the self-fertilizing hermaphrodite and male mangrove rivulus, Kryptolebias marmoratus". Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 37 (2): 353–365. doi:10.1677/jme.1.02101. PMID 17032750.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

I. Schlupp, J. Parzefall, J. T. Epplen, M. Schartl (2006). "Limia vittata as host species for the Amazon molly: no evidence for sexual reproduction". Journal of Fish Biology. 48 (4): 792–795. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1996.tb01472.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- Pang, K. "Certificate Biology: New Mastering Basic Concepts", Hong Kong, 2004

- Journal of Biology of Reproduction, accessed in August 2005.

- Michod, RE; Levin, BE, eds. (1987). The Evolution of sex: An examination of current ideas. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0878934588.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn13=ignored (help) - Michod, RE (1994). Eros and Evolution: A Natural Philosophy of Sex. Perseus Books. ISBN 020140754X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn13=ignored (help)