| Revision as of 18:17, 29 April 2019 editProkaryotes (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users17,246 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:25, 30 April 2019 edit undoFemke (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators21,069 edits Deleted line about global warming. Odd to put that in the lede. Also contained two mistakes.Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{redirect2|Clapeyron equation|Clapeyron's equation|a state equation|ideal gas law}} | {{redirect2|Clapeyron equation|Clapeyron's equation|a state equation|ideal gas law}} | ||

| The '''Clausius–Clapeyron relation''', named after ]<ref name="clausius">{{cite journal |last=Clausius |first=R. |title=Ueber die bewegende Kraft der Wärme und die Gesetze, welche sich daraus für die Wärmelehre selbst ableiten lassen |trans-title=On the motive power of heat and the laws which can be deduced therefrom regarding the theory of heat|journal=Annalen der Physik |volume=155 |issue= 4|pages=500–524 |year=1850 |url=http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k15164w/f518.image|doi=10.1002/andp.18501550403 |bibcode = 1850AnP...155..500C |language=German }}</ref> and ],<ref name="clapeyron">{{cite journal |last=Clapeyron |first=M. C. |url=http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4336791/f157 |title=Mémoire sur la puissance motrice de la chaleur |journal=Journal de l'École Polytechnique |volume=23 |issue= |pages=153–190 |year=1834 |id=ark:/12148/bpt6k4336791/f157 |language=French }}</ref> is a way of characterizing a discontinuous ] between two ] of a single constituent. |

The '''Clausius–Clapeyron relation''', named after ]<ref name="clausius">{{cite journal |last=Clausius |first=R. |title=Ueber die bewegende Kraft der Wärme und die Gesetze, welche sich daraus für die Wärmelehre selbst ableiten lassen |trans-title=On the motive power of heat and the laws which can be deduced therefrom regarding the theory of heat|journal=Annalen der Physik |volume=155 |issue= 4|pages=500–524 |year=1850 |url=http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k15164w/f518.image|doi=10.1002/andp.18501550403 |bibcode = 1850AnP...155..500C |language=German }}</ref> and ],<ref name="clapeyron">{{cite journal |last=Clapeyron |first=M. C. |url=http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4336791/f157 |title=Mémoire sur la puissance motrice de la chaleur |journal=Journal de l'École Polytechnique |volume=23 |issue= |pages=153–190 |year=1834 |id=ark:/12148/bpt6k4336791/f157 |language=French }}</ref> is a way of characterizing a discontinuous ] between two ] of a single constituent. | ||

| ==Definition== | ==Definition== | ||

Revision as of 15:25, 30 April 2019

"Clapeyron equation" and "Clapeyron's equation" redirect here. For a state equation, see ideal gas law.The Clausius–Clapeyron relation, named after Rudolf Clausius and Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron, is a way of characterizing a discontinuous phase transition between two phases of matter of a single constituent.

Definition

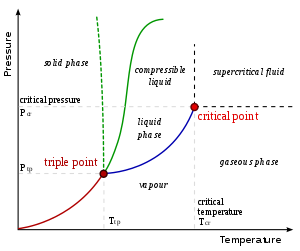

On a pressure–temperature (P–T) diagram, the line separating the two phases is known as the coexistence curve. The Clausius–Clapeyron relation gives the slope of the tangents to this curve. Mathematically,

where is the slope of the tangent to the coexistence curve at any point, is the specific latent heat, is the temperature, is the specific volume change of the phase transition, and is the specific entropy change of the phase transition.

Derivations

Derivation from state postulate

Using the state postulate, take the specific entropy for a homogeneous substance to be a function of specific volume and temperature .

The Clausius–Clapeyron relation characterizes behavior of a closed system during a phase change, during which temperature and pressure are constant by definition. Therefore,

Using the appropriate Maxwell relation gives

where is the pressure. Since pressure and temperature are constant, by definition the derivative of pressure with respect to temperature does not change. Therefore, the partial derivative of specific entropy may be changed into a total derivative

and the total derivative of pressure with respect to temperature may be factored out when integrating from an initial phase to a final phase , to obtain

where and are respectively the change in specific entropy and specific volume. Given that a phase change is an internally reversible process, and that our system is closed, the first law of thermodynamics holds

where is the internal energy of the system. Given constant pressure and temperature (during a phase change) and the definition of specific enthalpy , we obtain

Given constant pressure and temperature (during a phase change), we obtain

Substituting the definition of specific latent heat gives

Substituting this result into the pressure derivative given above (), we obtain

This result (also known as the Clapeyron equation) equates the slope of the tangent to the coexistence curve , at any given point on the curve, to the function of the specific latent heat , the temperature , and the change in specific volume .

Derivation from Gibbs–Duhem relation

Suppose two phases, and , are in contact and at equilibrium with each other. Their chemical potentials are related by

Furthermore, along the coexistence curve,

One may therefore use the Gibbs–Duhem relation

(where is the specific entropy, is the specific volume, and is the molar mass) to obtain

Rearrangement gives

from which the derivation of the Clapeyron equation continues as in the previous section.

Ideal gas approximation at low temperatures

When the phase transition of a substance is between a gas phase and a condensed phase (liquid or solid), and occurs at temperatures much lower than the critical temperature of that substance, the specific volume of the gas phase greatly exceeds that of the condensed phase . Therefore, one may approximate

at low temperatures. If pressure is also low, the gas may be approximated by the ideal gas law, so that

where is the pressure, is the specific gas constant, and is the temperature. Substituting into the Clapeyron equation

we can obtain the Clausius–Clapeyron equation

for low temperatures and pressures, where is the specific latent heat of the substance.

Let and be any two points along the coexistence curve between two phases and . In general, varies between any two such points, as a function of temperature. But if is constant,

or

These last equations are useful because they relate equilibrium or saturation vapor pressure and temperature to the latent heat of the phase change, without requiring specific volume data.

Applications

Chemistry and chemengineering

For transitions between a gas and a condensed phase with the approximations described above, the expression may be rewritten as

where is a constant. For a liquid-gas transition, is the specific latent heat (or specific enthalpy) of vaporization; for a solid-gas transition, is the specific latent heat of sublimation. If the latent heat is known, then knowledge of one point on the coexistence curve determines the rest of the curve. Conversely, the relationship between and is linear, and so linear regression is used to estimate the latent heat.

Meteorology and climatology

Atmospheric water vapor drives many important meteorologic phenomena (notably precipitation), motivating interest in its dynamics. The Clausius–Clapeyron equation for water vapor under typical atmospheric conditions (near standard temperature and pressure) is

where:

- is saturation vapor pressure

- is temperature

- is the specific latent heat of evaporation of water

- is the gas constant of water vapor

The temperature dependence of the latent heat , and therefore of the saturation vapor pressure , cannot be neglected in this application. Fortunately, the August-Roche-Magnus formula provides a very good approximation, using pressure in hPa and temperature in Celsius:

(This is also sometimes called the Magnus or Magnus-Tetens approximation, though this attribution is historically inaccurate.) But see also this discussion of the accuracy of different approximating formulae for saturation vapour pressure of water.

Under typical atmospheric conditions, the denominator of the exponent depends weakly on (for which the unit is Celsius). Therefore, the August-Roche-Magnus equation implies that saturation water vapor pressure changes approximately exponentially with temperature under typical atmospheric conditions, and hence the water-holding capacity of the atmosphere increases by about 7% for every 1 °C rise in temperature.

Example

One of the uses of this equation is to determine if a phase transition will occur in a given situation. Consider the question of how much pressure is needed to melt ice at a temperature below 0 °C. Note that water is unusual in that its change in volume upon melting is negative. We can assume

and substituting in

- = 3.34×10 J/kg (latent heat of fusion for water),

- = 273 K (absolute temperature), and

- = −9.05×10 m³/kg (change in specific volume from solid to liquid),

we obtain

- = −13.5 MPa/K.

To provide a rough example of how much pressure this is, to melt ice at −7 °C (the temperature many ice skating rinks are set at) would require balancing a small car (mass = 1000 kg) on a thimble (area = 1 cm²).

Second derivative

While the Clausius–Clapeyron relation gives the slope of the coexistence curve, it does not provide any information about its curvature or second derivative. The second derivative of the coexistence curve of phases 1 and 2 is given by

where subscripts 1 and 2 denote the different phases, is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure, is the thermal expansion coefficient, and is the isothermal compressibility.

See also

References

- Clausius, R. (1850). "Ueber die bewegende Kraft der Wärme und die Gesetze, welche sich daraus für die Wärmelehre selbst ableiten lassen" [On the motive power of heat and the laws which can be deduced therefrom regarding the theory of heat]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 155 (4): 500–524. Bibcode:1850AnP...155..500C. doi:10.1002/andp.18501550403.

- Clapeyron, M. C. (1834). "Mémoire sur la puissance motrice de la chaleur". Journal de l'École Polytechnique (in French). 23: 153–190. ark:/12148/bpt6k4336791/f157.

- ^ Wark, Kenneth (1988) . "Generalized Thermodynamic Relationships". Thermodynamics (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc. ISBN 978-0-07-068286-3.

- Carl Rod Nave (2006). "PvT Surface for a Substance which Contracts Upon Freezing". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ^ Çengel, Yunus A.; Boles, Michael A. (1998) . Thermodynamics – An Engineering Approach. McGraw-Hill Series in Mechanical Engineering (3rd ed.). Boston, MA.: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-011927-7.

- Salzman, William R. (2001-08-21). "Clapeyron and Clausius–Clapeyron Equations". Chemical Thermodynamics. University of Arizona. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- Alduchov, Oleg; Eskridge, Robert (1997-11-01), Improved Magnus' Form Approximation of Saturation Vapor Pressure, NOAA, doi:10.2172/548871 — Equation 25 provides these coefficients.

- Alduchov, Oleg A.; Eskridge, Robert E. (1996). "Improved Magnus Form Approximation of Saturation Vapor Pressure". Journal of Applied Meteorology. 35 (4): 601–9. Bibcode:1996JApMe..35..601A. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1996)035<0601:IMFAOS>2.0.CO;2. Equation 21 provides these coefficients.

- Lawrence, M. G. (2005). "The Relationship between Relative Humidity and the Dewpoint Temperature in Moist Air: A Simple Conversion and Applications" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 86 (2): 225–233. Bibcode:2005BAMS...86..225L. doi:10.1175/BAMS-86-2-225.

- IPCC, Climate Change 2007: Working Group I: The Physical Science Basis, "FAQ 3.2 How is Precipitation Changing ?", URL http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/faq-3-2.html

- Zorina, Yana (2000). "Mass of a Car". The Physics Factbook.

- Krafcik, Matthew; Sánchez Velasco, Eduardo (2014). "Beyond Clausius–Clapeyron: Determining the second derivative of a first-order phase transition line". American Journal of Physics. 82 (4): 301–305. Bibcode:2014AmJPh..82..301K. doi:10.1119/1.4858403.

Bibliography

- Yau, M.K.; Rogers, R.R. (1989). Short Course in Cloud Physics (3rd ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3215-7.

- Iribarne, J.V.; Godson, W.L. (2013). "4. Water-Air systems § 4.8 Clausius–Clapeyron Equation". Atmospheric Thermodynamics. Springer. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-94-010-2642-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Callen, H.B. (1985). Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-86256-7.

is the slope of the tangent to the coexistence curve at any point,

is the slope of the tangent to the coexistence curve at any point,  is the specific

is the specific  is the

is the  is the

is the  is the

is the  for a

for a  and

and

is the pressure. Since pressure and temperature are constant, by definition the derivative of pressure with respect to temperature does not change. Therefore, the

is the pressure. Since pressure and temperature are constant, by definition the derivative of pressure with respect to temperature does not change. Therefore, the

to a final phase

to a final phase  , to obtain

, to obtain

and

and  are respectively the change in specific entropy and specific volume. Given that a phase change is an internally

are respectively the change in specific entropy and specific volume. Given that a phase change is an internally

is the

is the  , we obtain

, we obtain

gives

gives

), we obtain

), we obtain

of the specific latent heat

of the specific latent heat

is the

is the

greatly exceeds that of the condensed phase

greatly exceeds that of the condensed phase  . Therefore, one may approximate

. Therefore, one may approximate

is the

is the

and

and  be any two points along the

be any two points along the

is a constant. For a liquid-gas transition,

is a constant. For a liquid-gas transition,  and

and  is linear, and so

is linear, and so

is

is  is the

is the  is the

is the  , and therefore of the saturation vapor pressure

, and therefore of the saturation vapor pressure  ,

,

below 0 °C. Note that water is unusual in that its change in volume upon melting is negative. We can assume

below 0 °C. Note that water is unusual in that its change in volume upon melting is negative. We can assume

= −13.5 MPa/K.

= −13.5 MPa/K.

is the specific

is the specific  is the

is the  is the

is the