| Revision as of 03:04, 5 February 2020 edit64.106.111.74 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:05, 5 February 2020 edit undo64.106.111.74 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

| ===The CAIS Experience=== | ===The CAIS Experience=== | ||

| Those with CAIS often experience discrimination which negatively impacts their lives. This comes in the form of online abuse, comments by high school and undergraduate level biology teachers who are uneducated on the nuances of sex and gender, and sometimes worse. In the medical setting, individuals with CAIS are unable to be processed properly as paperwork is required of them that is not related to their physical health or their gender identity. Uneducated medical professionals may refuse care, make inappropriate comments, ask inappropriate questions, or make CAIS patients the targets of sexual abuse in extreme cases. Media representation is often wildly insensitive and misrepresenting. Depictions of CAIS women are often hypersexualized. CAIS is often the root of many insensitive jokes and included as a "gotcha" plot twist in books about "strange bodies." CAIS women are often referred to as males on the basis of their XY karyotype despite their absent response to their Y chromosome, their female phenotype, and female or nonbinary identity. The term "affected males" or "genetic males" used by article and textbook authors is misrepresenting and often used as evidence by uneducated and hateful individuals to invalidate the identity and truth of their normal existence. Future discussion of CAIS should be focused on wider acceptance of those outside the typical gender/sex binary, and improving medical care for these women. | Those with CAIS often experience discrimination which negatively impacts their lives. This comes in the form of online abuse, comments by high school and undergraduate level biology teachers who are uneducated on the nuances of sex and gender, and sometimes worse. In the medical setting, individuals with CAIS are unable to be processed properly as paperwork is required of them that is not related to their physical health or their gender identity. Uneducated medical professionals may refuse care, make inappropriate comments, ask inappropriate questions, or make CAIS patients the targets of sexual abuse in extreme cases. Media representation is often wildly insensitive and misrepresenting. Depictions of CAIS women are often hypersexualized. CAIS is often the root of many insensitive jokes and included as a "gotcha" plot twist in books about "strange bodies." CAIS women are often referred to as males on the basis of their XY karyotype despite their absent response to their Y chromosome, their female phenotype, and female or nonbinary identity. The term "affected males" or "genetic males" used by article and textbook authors is misrepresenting and often used as evidence by uneducated and hateful individuals to invalidate the identity and truth of their normal existence. Future discussion of CAIS should be focused on wider acceptance of those outside the typical gender/sex binary, and improving medical care for these women. This section was written by CAIS individual/activist Chelsea Kaban based on her personal experiences as well as the testimonies of other CAIS individuals. | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 03:05, 5 February 2020

Intersex condition that results in a phenotypic female Medical condition| Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Complete androgen resistance syndrome |

| |

| AIS results when the function of the androgen receptor (AR) is impaired. The AR protein (pictured) mediates the effects of androgens in the human body. | |

| Specialty | Gynaecology, endocrinology |

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) is a condition that results in the complete inability of the cell to respond to androgens. The unresponsiveness of the cell to the presence of androgenic hormones prevents the masculinization of male genitalia in the developing fetus, as well as the development of male secondary sexual characteristics at puberty, but does allow, without significant impairment, female genital and sexual development in XY karyotype women with the condition.

All human fetuses begin fetal development looking similar, with both the Müllerian duct system (female) and the Wolffian duct system (male) developing. It is at the seventh week of gestation that the bodies of unaffected individuals with the XY karyotype begin their masculinization: i.e, the Wolffian duct system is promoted and the Müllerian duct system is suppressed (the reverse happens with typically developing females). This process is triggered by androgens produced by the gonads, which in individuals with the XX karyotype had earlier become ovaries, but in XY individuals typically had become testicles due to the presence of the Y Chromosome. The cells of unaffected XY individuals then masculinize by, among other things, enlarging the genital tubercle into a penis, which in females becomes the clitoris, while what in females becomes the labia fuses to become the scrotum of males (where the testicles will later descend).

Individuals affected by CAIS develop a normal external female habitus, despite the presence of a Y chromosome, but internally, they will lack a uterus, and the vaginal cavity will be shallow, while the gonads, having been turned into testicles rather than ovaries in the earlier separate process also triggered by their Y chromosome, will remain undescended in the place where the ovaries would have been. This results not only in infertility individuals with CAIS, but also presents a risk of gonadal cancer later on in life.

CAIS is one of the three categories of androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) since AIS is differentiated according to the degree of genital masculinization: complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) when the external genitalia is that of a typical female, mild androgen insensitivity syndrome (MAIS) when the external genitalia is that of a typical male, and partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (PAIS) when the external genitalia is partially, but not fully masculinized.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome is the largest single entity that leads to 46,XY undermasculinization.

Signs and symptoms

Individuals with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (grades 6 and 7 on the Quigley scale) are born phenotypically female, without any signs of genital masculinization, despite having a 46,XY karyotype. Symptoms of CAIS do not appear until puberty, which may be slightly delayed, but is otherwise normal except for absent menses and diminished or absent secondary terminal hair. Axillary hair (i.e. armpit hair) fails to develop in one third of all cases. External genitalia is normal, although the labia and clitoris are sometimes underdeveloped. Vaginal depth varies widely for CAIS women, but is typically shorter than unaffected women; one study of eight women with CAIS measured the average vaginal depth to be 5.9 cm (vs. 11.1 ± 1.0 cm for unaffected women ). In some extreme cases, the vagina has been reported to be aplastic (resembling a "dimple"), though the exact incidence of this is unknown.

The gonads in these women are not ovaries, but instead, are more similar to testes; during the embryonic stage of development, testes form in an androgen-independent process that occurs due to the influence of the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. They may be located intra-abdominally, at the internal inguinal ring, or may herniate into the labia majora, often leading to the discovery of the condition. Testes in affected women have been found to be atrophic upon removal. Testosterone produced by the testes cannot be directly used due to the mutated androgen receptor that characterizes CAIS; instead, it is aromatized into estrogen, which effectively feminizes the body and accounts for the normal female development observed in CAIS women.

Immature sperm cells in the testes do not mature past an early stage, as sensitivity to androgens is required in order for spermatogenesis to complete. Germ cell malignancy risk, once thought to be relatively high, is now thought to be approximately 2%. Wolffian structures (the epididymides, vasa deferentia, and seminal vesicles) are typically absent, but will develop at least partially in approximately 30% of cases, depending on which mutation is causing the CAIS. The prostate, like the external male genitalia, cannot masculinize in the absence of androgen receptor function, and thus remains in the female form.

The Müllerian system (the fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper portion of the vagina) typically regresses due to the presence of anti-Müllerian hormone originating from the Sertoli cells of the testes. These women are thus born without fallopian tubes, a cervix, or a uterus, and the vagina ends "blindly" in a pouch. Müllerian regression does not fully complete in approximately one third of all cases, resulting in Müllerian "remnants". Although rare, a few cases of women with CAIS and fully developed Müllerian structures have been reported. In one exceptional case, a 22-year-old with CAIS was found to have a normal cervix, uterus, and fallopian tubes. In an unrelated case, a fully developed uterus was found in a 22-year-old adult with CAIS.

Other subtle differences that have been reported include slightly longer limbs and larger hands and feet due to a proportionally greater stature than unaffected women, larger teeth, minimal or no acne, well developed breasts, and a greater incidence of meibomian gland dysfunction (i.e. dry eye syndromes and light sensitivity).

Comorbidity

All forms of androgen insensitivity, including CAIS, are associated with infertility, though exceptions have been reported for both the mild and partial forms.

CAIS is associated with a decreased bone mineral density. Some have hypothesized that the decreased bone mineral density observed in women with CAIS is related to the timing of gonadectomy and inadequate estrogen supplementation. However, recent studies show that bone mineral density is similar whether gonadectomy occurs before or after puberty, and is decreased despite estrogen supplementation, leading some to hypothesize that the deficiency is directly attributable to the role of androgens in bone mineralization. . Studies show however that hormonal replacement therapy in CAIS women reduces the loss of bone density over time compared to CAIS women who do not receive consistent estrogen replacement.

CAIS is also associated with an increased risk for gonadal tumors (e.g. germ cell malignancy) in adulthood if gonadectomy is not performed. The risk of malignant germ cell tumors in women with CAIS increases with age and has been estimated to be 3.6% at 25 years and 33% at 50 years. The incidence of gonadal tumors in childhood is thought to be relatively low; a recent review of the medical literature found that only three cases of malignant germ cell tumors in prepubescent girls have been reported in association with CAIS in the last 100 years. Some have estimated the incidence of germ cell malignancy to be as low as 0.8% before puberty.

Vaginal hypoplasia, a relatively frequent finding in CAIS and some forms of PAIS, is associated with sexual difficulties including vaginal penetration difficulties and dyspareunia.

At least one study indicates that individuals with an intersex condition may be more prone to psychological difficulties, due at least in part to parental attitudes and behaviors, and concludes that preventative long-term psychological counseling for parents as well as for affected individuals should be initiated at the time of diagnosis. Psychological damage as a result of CAIS is instead a result of internalized stigma, in combination with discrimination on the part of medical professionals, poor media representation, and individuals that the CAIS woman encounters who are not properly educated on genetics and the normal occurrence of intersex individuals. Sensitivity to intersex individuals can best be taken from an LGBTQ+ perspective, where acceptance rather than marginalization is practiced. A major source of trauma for CAIS women comes from misgendering by others who refer to affected women as "genetic males" as opposed to "affected females" as the decision to label sex by karyotype rather than by phenotype or psychological identity is based on little more than tradition. This practice directly invalidates the identity of these naturally occurring XY karyotype females.

Lifespan is not thought to be affected by AIS.

Diagnosis

Main article: Diagnosis of androgen insensitivity syndrome

CAIS can only be diagnosed in normal phenotypic females. It is not usually suspected unless the menses fail to develop at puberty, or an inguinal hernia presents during premenarche. As many as 1–2% of prepubertal girls that present with an inguinal hernia will also have CAIS.

A diagnosis of CAIS or Swyer syndrome can be made in utero by comparing a karyotype obtained by amniocentesis with the external genitalia of the fetus during a prenatal ultrasound. Many infants with CAIS do not experience the normal, spontaneous neonatal testosterone surge, a fact which can be diagnostically exploited by obtaining baseline luteinizing hormone and testosterone measurements, followed by a human chorionic gonadotropin (hGC) stimulation test.

The main differentials for CAIS are complete gonadal dysgenesis (Swyer syndrome) and Müllerian agenesis (Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome or MRKH). Both CAIS and Swyer syndrome are associated with a 46,XY karyotype, whereas MRKH is not; MRKH can thus be ruled out by checking for the presence of a Y chromosome, which can be done either by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis or on full karyotype. Swyer syndrome is distinguished by the presence of a uterus, poor breast development and shorter stature. The diagnosis of CAIS is confirmed when androgen receptor (AR) gene sequencing reveals a mutation, although up to 5% of individuals with CAIS do not have an AR mutation.

Up until the 1990s, a CAIS diagnosis was often hidden from the affected individual, the individual's family, or both. It is current practice to disclose the genotype at the time of diagnosis, particularly when the affected girl is at least of adolescent age. If the affected individual is a child or infant, it is generally up to the parents, often in conjunction with a psychologist, to decide when to disclose the diagnosis. This practice has caused unprecedented psychological harm to many CAIS individuals. It is of best medical practice to disclose diagnosis as early as possible, and to reassure the patient that this normally occurring condition is not a source of shame. This condition does not have to result in psychological distress as long as affected families are properly educated on gender and sex binary myths and truths. Terms such as mutant, abnormal, and accident should be avoided. Instead, the validity of the rare but normal occurrence should be stressed to affected females.

Management

Management of AIS is currently limited to symptomatic management; methods to correct a malfunctioning androgen receptor protein that result from an AR gene mutation are not currently available. Areas of management include sex assignment, genitoplasty, gonadectomy in relation to tumor risk, hormone replacement therapy, and genetic and psychological counseling. Non-consensual interventions erase the validity of the individual's identity and right to exist in the body they were born into naturally. Non-consensual interventions are still often performed, although general awareness on the resulting psychological traumatization is rising.

Sex assignment and sexuality

Individuals with CAIS are raised as females. They are born phenotypically female and typically have a female gender identity; However, at least two case studies have reported male gender identity in individuals with CAIS (which is consistent with the incidence of transgender identity over all people). Individuals with CAIS can identify as nonbinary as their biological sex and gender identity are not fully explained by the traditional understanding of gender. CAIS women are typically heterosexual but some CAIS women have reported to be sexually fluid/bisexual.

Dilation therapy

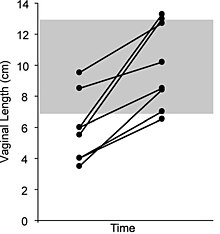

Most cases of vaginal hypoplasia associated with CAIS can be corrected using non-surgical pressure dilation methods. The elastic nature of vaginal tissue, as demonstrated by its ability to accommodate the differences in size between a tampon, a penis, and a baby's head, make dilation possible even in cases when the vaginal depth is significantly compromised. Treatment compliance is thought to be critical to achieve satisfactory results. Dilation can also be achieved via the Vecchietti procedure, which stretches vaginal tissues into a functional vagina using a traction device that is anchored to the abdominal wall, subperitoneal sutures, and a mold that is placed against the vaginal dimple. Vaginal stretching occurs by increasing the tension on the sutures, which is performed daily. The non-operative pressure dilation method is currently recommended as the first choice, since it is non-invasive, and highly successful. Vaginal dilation should not be performed before puberty.

Gonadectomy

While it is often recommended that women with CAIS eventually undergo gonadectomy to mitigate cancer risk, there are differing opinions regarding the necessity and timing of gonadectomy. The risk of malignant germ cell tumors in women with CAIS increases with age and has been estimated to be 3.6% at 25 years and 33% at 50 years. However, only three cases of malignant germ cell tumors in prepubescent girls with CAIS have been reported in the last 100 years. The youngest of these girls was 14 years old. If gonadectomy is performed early, then puberty must be artificially induced using gradually increasing doses of estrogen. If gonadectomy is performed late, then puberty will occur on its own, due to the aromatization of testosterone into estrogen. At least one organization, the Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group, classifies the cancer risk associated with CAIS as low enough to recommend against gonadectomy, although it warns that the cancer risk is still elevated above the general population, and that ongoing cancer monitoring is essential. Some choose to perform gonadectomy if and when inguinal hernia presents. Estrogen replacement therapy is critical to minimize bone mineral density deficiencies later in life. Individuals with CAIS often prefer to refer to this procedure as a gonadectomy or oophorectomy (removal of ovaries). This is to mitigate the risk and subsequent discrimination from individuals who do not understand their condition. CAIS women are often subjected to transphobic hatred as many people do not understand those with sex and gender differences. Further, where this gonadectormy practice is commonly referred to castration in animal care and in relation to punishment of criminals via testicle removal, it is inhumane and invalidating to refer to this practice as castration when discussing a CAIS individual.

Hormone replacement therapy

Some have hypothesized that supraphysiological levels of estrogen may reduce the diminished bone mineral density associated with CAIS. Data has been published that suggests affected women who were not compliant with estrogen replacement therapy, or who had a lapse in estrogen replacement, experienced a more significant loss of bone mineral density. Progestin replacement therapy is seldom initiated, due to the absence of a uterus. Androgen replacement has been reported to increase a sense of well-being in gonadectomized women with CAIS, although the mechanism by which this benefit is achieved is not well understood. Individuals with CAIS often experience struggles with medical professionals and insurance companies to receive the care needed. This is because hormone replacement therapy is women is most often prescribed as a supplement for post-menopausal women, whereas the need for HRT is expressed much younger in CAIS women who have a gonadectomy as early as puberty. They often require a higher dose of estrogen than a post-menopausal woman, and therefore have difficulties with insurance companies who will not approve of doses that are not typical despite their difference in need. Improper dosage can result in extreme side effects such as major depressive episodes or mood swings, or menopausal symptoms when a dose is too light. Due to this, greater care should be taken by insurance companies and physicians who work with CAIS women to insure that they receive the care they need. CAIS women are often faced with medical discrimination.

Counseling

It is no longer common practice to hide a diagnosis of CAIS from the affected individual or her family. Parents of children with CAIS need considerable support in planning and implementing disclosure for their child once the diagnosis has been established. For parents with young children, information disclosure is an ongoing, collaborative process requiring an individualized approach that evolves in concordance with the child's cognitive and psychological development. In all cases, the assistance of a psychologist experienced in the subject is recommended.

Neovaginal construction

Many surgical procedures have been developed to create a neovagina, as none of them is ideal. Surgical intervention should only be considered after non-surgical pressure dilation methods have failed to produce a satisfactory result. Neovaginoplasty can be performed using skin grafts, a segment of bowel, ileum, peritoneum, Interceed, buccal mucosa, amnion, or dura mater. Success of such methods should be determined by sexual function, and not just by vaginal length, as has been done in the past. Ileal or cecal segments may be problematic because of a shorter mesentery, which may produce tension on the neovagina, leading to stenosis. The sigmoid neovagina is thought to be self-lubricating, without the excess mucus production associated with segments of small bowel. Vaginoplasty may create scarring at the introitus (the vaginal opening), which requires additional surgery to correct. Vaginal dilators are required postoperatively to prevent vaginal stenosis from scarring. Other complications include bladder and bowel injuries. Yearly exams are required as neovaginoplasty carries a risk of carcinoma, although carcinoma of the neovagina is uncommon. Neither neovaginoplasty nor vaginal dilation should be performed before puberty.

Prognosis

Challenges presented to people affected by this condition include: psychologically coming to terms with the condition, difficulties with sexual function, infertility. Long-term studies indicate that with appropriate medical and psychological treatment, women with CAIS can be satisfied with their sexual function and psychosexual development. CAIS women can lead active lives and expect a normal lifespan.

Nomenclature

Main article: Other names for androgen insensitivity syndromeHistorically, CAIS has been referred to in the literature under a number of other names, including testicular feminization (deprecated) and Morris syndrome. PAIS has also been referred to as Reifenstein syndrome, which should not be confused with CAIS. Referring to this condition as anything other than CAIS or more broadly as an intersex condition is invalidating and medically inaccurate. In the past, this condition (and others) was referred to as hermaphroditism. This word is exclusively meant for observance of sex-switching in animals and not to be used in reference to an individual with CAIS or any intersex condition.

History

The first definitive description of CAIS was reported in 1817. The condition became more widely known after it was reviewed and named testicular feminization by Morris in 1953. This name is no longer accepted by those in the medical community or those affected by CAIS.

The CAIS Experience

Those with CAIS often experience discrimination which negatively impacts their lives. This comes in the form of online abuse, comments by high school and undergraduate level biology teachers who are uneducated on the nuances of sex and gender, and sometimes worse. In the medical setting, individuals with CAIS are unable to be processed properly as paperwork is required of them that is not related to their physical health or their gender identity. Uneducated medical professionals may refuse care, make inappropriate comments, ask inappropriate questions, or make CAIS patients the targets of sexual abuse in extreme cases. Media representation is often wildly insensitive and misrepresenting. Depictions of CAIS women are often hypersexualized. CAIS is often the root of many insensitive jokes and included as a "gotcha" plot twist in books about "strange bodies." CAIS women are often referred to as males on the basis of their XY karyotype despite their absent response to their Y chromosome, their female phenotype, and female or nonbinary identity. The term "affected males" or "genetic males" used by article and textbook authors is misrepresenting and often used as evidence by uneducated and hateful individuals to invalidate the identity and truth of their normal existence. Future discussion of CAIS should be focused on wider acceptance of those outside the typical gender/sex binary, and improving medical care for these women. This section was written by CAIS individual/activist Chelsea Kaban based on her personal experiences as well as the testimonies of other CAIS individuals.

See also

References

- ^ Hughes IA, Deeb A (December 2006). "Androgen resistance". Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 20 (4): 577–98. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2006.11.003. PMID 17161333.

- ^ Galani A, Kitsiou-Tzeli S, Sofokleous C, Kanavakis E, Kalpini-Mavrou A (2008). "Androgen insensitivity syndrome: clinical features and molecular defects". Hormones (Athens). 7 (3): 217–29. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1201. PMID 18694860.

- ^ Quigley CA, De Bellis A, Marschke KB, el-Awady MK, Wilson EM, French FS (June 1995). "Androgen receptor defects: historical, clinical, and molecular perspectives". Endocr. Rev. 16 (3): 271–321. doi:10.1210/edrv-16-3-271. PMID 7671849.

- ^ Giwercman YL, Nordenskjöld A, Ritzén EM, Nilsson KO, Ivarsson SA, Grandell U, Wedell A (June 2002). "An androgen receptor gene mutation (E653K) in a family with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency as well as in partial androgen insensitivity". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87 (6): 2623–8. doi:10.1210/jc.87.6.2623. PMID 12050225.

- ^ Zuccarello D, Ferlin A, Vinanzi C, Prana E, Garolla A, Callewaert L, Claessens F, Brinkmann AO, Foresta C (April 2008). "Detailed functional studies on androgen receptor mild mutations demonstrate their association with male infertility". Clin. Endocrinol. 68 (4): 580–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03069.x. PMID 17970778.

- ^ Ferlin A, Vinanzi C, Garolla A, Selice R, Zuccarello D, Cazzadore C, Foresta C (November 2006). "Male infertility and androgen receptor gene mutations: clinical features and identification of seven novel mutations". Clin. Endocrinol. 65 (5): 606–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02635.x. PMID 17054461.

- ^ Stouffs K, Tournaye H, Liebaers I, Lissens W (2009). "Male infertility and the involvement of the X chromosome". Hum. Reprod. Update. 15 (6): 623–37. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp023. PMID 19515807.

- Giwercman YL, Nikoshkov A, Byström B, Pousette A, Arver S, Wedell A (June 2001). "A novel mutation (N233K) in the transactivating domain and the N756S mutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor gene are associated with male infertility". Clin. Endocrinol. 54 (6): 827–34. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01308.x. PMID 11422119.

- Lund A, Juvonen V, Lähdetie J, Aittomäki K, Tapanainen JS, Savontaus ML (June 2003). "A novel sequence variation in the transactivation regulating domain of the androgen receptor in two infertile Finnish men". Fertil. Steril. 79 Suppl 3: 1647–8. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00256-5. PMID 12801573.

- Ozülker T, Ozpaçaci T, Ozülker F, Ozekici U, Bilgiç R, Mert M (January 2010). "Incidental detection of Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor by FDG PET/CT imaging in a patient with androgen insensitivity syndrome". Ann Nucl Med. 24 (1): 35–9. doi:10.1007/s12149-009-0321-x. PMID 19957213.

- Davis-Dao CA, Tuazon ED, Sokol RZ, Cortessis VK (November 2007). "Male infertility and variation in CAG repeat length in the androgen receptor gene: a meta-analysis". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92 (11): 4319–26. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1110. PMID 17684052.

- Kawate H, Wu Y, Ohnaka K, Tao RH, Nakamura K, Okabe T, Yanase T, Nawata H, Takayanagi R (November 2005). "Impaired nuclear translocation, nuclear matrix targeting, and intranuclear mobility of mutant androgen receptors carrying amino acid substitutions in the deoxyribonucleic acid-binding domain derived from androgen insensitivity syndrome patients". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90 (11): 6162–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0179. PMID 16118342.

- Gottlieb B, Lombroso R, Beitel LK, Trifiro MA (January 2005). "Molecular pathology of the androgen receptor in male (in)fertility". Reprod. Biomed. Online. 10 (1): 42–8. doi:10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60802-4. PMID 15705293.

- Ahmed SF, Cheng A, Hughes IA (April 1999). "Assessment of the gonadotrophin-gonadal axis in androgen insensitivity syndrome". Arch. Dis. Child. 80 (4): 324–9. doi:10.1136/adc.80.4.324. PMC 1717906. PMID 10086936.

- Jirásek JE, Simpson JL (1976). Disorders of sexual differentiation: etiology and clinical delineation. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-644450-6.

- Gilbert SF (2000). Developmental biology. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6.

- ^ Oakes MB, Eyvazzadeh AD, Quint E, Smith YR (December 2008). "Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome--a review". J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 21 (6): 305–10. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2007.09.006. PMID 19064222.

- ^ Nichols JL, Bieber EJ, Gell JS (2009). "Case of sisters with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome and discordant Müllerian remnants". Fertil. Steril. 91 (3): 932.e15–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.027. PMID 18930210.

- Melo KF, Mendonca BB, Billerbeck AE, Costa EM, Inácio M, Silva FA, Leal AM, Latronico AC, Arnhold IJ (July 2003). "Clinical, hormonal, behavioral, and genetic characteristics of androgen insensitivity syndrome in a Brazilian cohort: five novel mutations in the androgen receptor gene". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88 (7): 3241–50. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021658. PMID 12843171.

- ^ Minto CL, Liao KL, Conway GS, Creighton SM (July 2003). "Sexual function in women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome". Fertil. Steril. 80 (1): 157–64. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.543.7011. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00501-6. PMID 12849818.

- Sinnecker GH, Hiort O, Nitsche EM, Holterhus PM, Kruse K (January 1997). "Functional assessment and clinical classification of androgen sensitivity in patients with mutations of the androgen receptor gene. German Collaborative Intersex Study Group". Eur. J. Pediatr. 156 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1007/s004310050542. PMID 9007482.

- ^ Ismail-Pratt IS, Bikoo M, Liao LM, Conway GS, Creighton SM (July 2007). "Normalization of the vagina by dilator treatment alone in Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome and Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser Syndrome". Hum. Reprod. 22 (7): 2020–4. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem074. PMID 17449508.

- Weber AM, Walters MD, Schover LR, Mitchinson A (December 1995). "Vaginal anatomy and sexual function". Obstet Gynecol. 86 (6): 946–9. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00291-X. PMID 7501345.

- ^ Quint EH, McCarthy JD, Smith YR (March 2010). "Vaginal surgery for congenital anomalies". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 53 (1): 115–24. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181cd4128. PMID 20142648.

- Achermann JC, Jameson JL (2006). "Disorders of sexual differentiation". In Hauser SL, Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Longo DL (eds.). Harrison's endocrinology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division. pp. 161–172. ISBN 978-0-07-145744-6.

- Simpson JL, Rebar RW (2002). Hung, Wellington, Becker, Kenneth L., Bilezikian, John P., William J Bremner (eds.). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 852–885. ISBN 978-0-7817-4245-0.

- Decaestecker K, Philibert P, De Baere E, Hoebeke P, Kaufman JM, Sultan C, T'Sjoen G (May 2008). "A novel mutation c.118delA in exon 1 of the androgen receptor gene resulting in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome within a large family". Fertil. Steril. 89 (5): 1260.e3–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.057. PMID 17714709.

- Morris JM (June 1953). "The syndrome of testicular feminization in male pseudohermaphrodites". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 65 (6): 1192–1211. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(53)90359-7. PMID 13057950.

- Müller J (October 1984). "Morphometry and histology of gonads from twelve children and adolescents with the androgen insensitivity (testicular feminization) syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 59 (4): 785–9. doi:10.1210/jcem-59-4-785. PMID 6480805.

- Johnston DS, Russell LD, Friel PJ, Griswold MD (June 2001). "Murine germ cells do not require functional androgen receptors to complete spermatogenesis following spermatogonial stem cell transplantation". Endocrinology. 142 (6): 2405–8. doi:10.1210/en.142.6.2405. PMID 11356688.

- Yong EL, Loy CJ, Sim KS (2003). "Androgen receptor gene and male infertility". Hum. Reprod. Update. 9 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmg003. PMID 12638777.

- ^ Hughes IA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, Lee PA (July 2006). "Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders". Arch. Dis. Child. 91 (7): 554–63. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.098319. PMC 2082839. PMID 16624884.

- Hannema SE, Scott IS, Hodapp J, Martin H, Coleman N, Schwabe JW, Hughes IA (November 2004). "Residual activity of mutant androgen receptors explains wolffian duct development in the complete androgen insensitivity syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (11): 5815–22. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0709. PMID 15531547.

- Roy AK, Lavrovsky Y, Song CS, Chen S, Jung MH, Velu NK, Bi BY, Chatterjee B (1999). Regulation of androgen action. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 55. pp. 309–52. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(08)60938-3. ISBN 9780127098555. PMID 9949684.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Kokontis JM, Liao S (1999). Molecular action of androgen in the normal and neoplastic prostate. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 55. pp. 219–307. doi:10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60937-1. ISBN 9780127098555. PMID 9949683.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Rajender S, Gupta NJ, Chakrabarty B, Singh L, Thangaraj K (March 2009). "Ala 586 Asp mutation in androgen receptor disrupts transactivation function without affecting androgen binding". Fertil. Steril. 91 (3): 933.e23–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.041. PMID 19062009.

- Chen CP, Chen SR, Wang TY, Wang W, Hwu YM (July 1999). "A frame shift mutation in the DNA-binding domain of the androgen receptor gene associated with complete androgen insensitivity, persistent müllerian structures, and germ cell tumors in dysgenetic gonads". Fertil. Steril. 72 (1): 170–3. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00169-7. PMID 10428170.

- Papadimitriou DT, Linglart A, Morel Y, Chaussain JL (2006). "Puberty in subjects with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome". Horm. Res. 65 (3): 126–31. doi:10.1159/000091592. PMID 16491011.

- ^ Wisniewski AB, Migeon CJ, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Gearhart JP, Berkovitz GD, Brown TR, Money J (2000). "Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: long-term medical, surgical, and psychosexual outcome". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 85 (8): 2664–2669. doi:10.1210/jc.85.8.2664.

- Varrela J, Alvesalo L, Vinkka H (1984). "Body size and shape in 46,XY females with complete testicular feminization". Annals of Human Biology. 11 (4): 291–301. doi:10.1080/03014468400007191. PMID 6465836.

- Alvesalo L, Varrela J (September 1980). "Permanent tooth sizes in 46,XY females". American Journal of Human Genetics. 32 (5): 736–42. PMC 1686090. PMID 7424913.

- Pietilä K, Grön M, Alvesalo L (August 1997). "The craniofacial complex in karyotype 46,XY females". Eur J Orthod. 19 (4): 383–9. doi:10.1093/ejo/19.4.383. PMID 9308259.

- Sultan C, Lumbroso S, Paris F, Jeandel C, Terouanne B, Belon C, Audran F, Poujol N, Georget V, Gobinet J, Jalaguier S, Auzou G, Nicolas JC (August 2002). "Disorders of androgen action". Semin. Reprod. Med. 20 (3): 217–28. doi:10.1055/s-2002-35386. PMID 12428202.

- Zachmann M, Prader A, Sobel EH, Crigler JF, Ritzén EM, Atarés M, Ferrandez A (May 1986). "Pubertal growth in patients with androgen insensitivity: indirect evidence for the importance of estrogens in pubertal growth of girls". J. Pediatr. 108 (5 Pt 1): 694–7. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(86)81043-5. PMID 3701515.

- Cermak JM, Krenzer KL, Sullivan RM, Dana MR, Sullivan DA (August 2003). "Is complete androgen insensitivity syndrome associated with alterations in the meibomian gland and ocular surface?". Cornea. 22 (6): 516–21. doi:10.1097/00003226-200308000-00006. PMID 12883343.

- Chu J, Zhang R, Zhao Z, Zou W, Han Y, Qi Q, Zhang H, Wang JC, Tao S, Liu X, Luo Z (January 2002). "Male fertility is compatible with an Arg(840)Cys substitution in the AR in a large Chinese family affected with divergent phenotypes of AR insensitivity syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87 (1): 347–51. doi:10.1210/jc.87.1.347. PMID 11788673.

- Menakaya UA, Aligbe J, Iribhogbe P, Agoreyo F, Okonofua FE (May 2005). "Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome with persistent Mullerian derivatives: a case report". J Obstet Gynaecol. 25 (4): 403–5. doi:10.1080/01443610500143226. PMID 16091340.

- Giwercman A, Kledal T, Schwartz M, Giwercman YL, Leffers H, Zazzi H, Wedell A, Skakkebaek NE (June 2000). "Preserved male fertility despite decreased androgen sensitivity caused by a mutation in the ligand-binding domain of the androgen receptor gene". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85 (6): 2253–9. doi:10.1210/jc.85.6.2253. PMID 10852459.

- ^ Danilovic DL, Correa PH, Costa EM, Melo KF, Mendonca BB, Arnhold IJ (March 2007). "Height and bone mineral density in androgen insensitivity syndrome with mutations in the androgen receptor gene". Osteoporos Int. 18 (3): 369–74. doi:10.1007/s00198-006-0243-6. PMID 17077943.

- ^ Sobel V, Schwartz B, Zhu YS, Cordero JJ, Imperato-McGinley J (August 2006). "Bone mineral density in the complete androgen insensitivity and 5alpha-reductase-2 deficiency syndromes". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91 (8): 3017–23. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2809. PMID 16735493.

- ^ Marcus R, Leary D, Schneider DL, Shane E, Favus M, Quigley CA (March 2000). "The contribution of testosterone to skeletal development and maintenance: lessons from the androgen insensitivity syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85 (3): 1032–7. doi:10.1210/jc.85.3.1032. PMID 10720035.

- ^ Bertelloni S, Baroncelli GI, Federico G, Cappa M, Lala R, Saggese G (1998). "Altered bone mineral density in patients with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome". Horm. Res. 50 (6): 309–14. doi:10.1159/000023296. PMID 9973670.

- ^ Soule SG, Conway G, Prelevic GM, Prentice M, Ginsburg J, Jacobs HS (December 1995). "Osteopenia as a feature of the androgen insensitivity syndrome". Clin. Endocrinol. 43 (6): 671–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb00533.x. PMID 8736267.

- Muñoz-Torres M, Jódar E, Quesada M, Escobar-Jiménez F (August 1995). "Bone mass in androgen-insensitivity syndrome: response to hormonal replacement therapy". Calcif. Tissue Int. 57 (2): 94–6. doi:10.1007/BF00298426. PMID 7584881.

- ^ Hannema SE, Scott IS, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebaek NE, Coleman N, Hughes IA (March 2006). "Testicular development in the complete androgen insensitivity syndrome". J. Pathol. 208 (4): 518–27. doi:10.1002/path.1890. PMID 16400621.

- Rutgers JL, Scully RE (1991). "The androgen insensitivity syndrome (testicular feminization): a clinicopathologic study of 43 cases". Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 10 (2): 126–44. doi:10.1097/00004347-199104000-00002. PMID 2032766.

- ^ Manuel M, Katayama PK, Jones HW (February 1976). "The age of occurrence of gonadal tumors in intersex patients with a Y chromosome". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 124 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90160-5. PMID 1247071.

- Slijper FM, Drop SL, Molenaar JC, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM (April 1998). "Long-term psychological evaluation of intersex children". Arch Sex Behav. 27 (2): 125–44. doi:10.1023/A:1018670129611. PMID 9562897.

- Borisa AD, Puri Y, Wakade V, Alagappan C, Agarkhedkar N (2006). "Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Presenting as Bilateral Inguinal Hernia". Bombay Hosp J. 48: 668–673.

- Michailidis GD, Papageorgiou P, Morris RW, Economides DL (July 2003). "The use of three-dimensional ultrasound for fetal gender determination in the first trimester". Br J Radiol. 76 (907): 448–51. doi:10.1259/bjr/13479830. PMID 12857703.

- Jones, Tiffany (2017). "Intersex and Families: Supporting Family Members With Intersex Variations". Journal of Family Strengths. 17 (2).

- ^ Kulshreshtha B, Philibert P, Eunice M, Khandelwal SK, Mehta M, Audran F, Paris F, Sultan C, Ammini AC (December 2009). "Apparent male gender identity in a patient with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome". Arch Sex Behav. 38 (6): 873–5. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9526-2. PMID 19636694.

- Tsjoen G, De Cuypere G, Monstrey S, Hoebeke P, Freedman FK, Appari M, Holterhus PM, Van Borsel J, Cools M (April 2010). "Male gender identity in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome". Arch. Sex. Behav. 40 (3): 635–638. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9624-1. PMID 20358272.

- Grover S (1996). "Stretch Yourself". Alias. 1: 76.

- ^ Submission 88 to the Australian Senate inquiry on the involuntary or coerced sterilisation of people with disabilities in Australia, Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group (APEG), 27 June 2013

- Hurt WG, Bodurtha JN, McCall JB, Ali MM (September 1989). "Seminoma in pubertal patient with androgen insensitivity syndrome". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 161 (3): 530–1. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(89)90350-5. PMID 2782332.

- Motoyama S, Laoag-Fernandez JB, Mochizuki S, Yamabe S, Maruo T (May 2003). "Vaginoplasty with Interceed absorbable adhesion barrier for complete squamous epithelialization in vaginal agenesis". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 188 (5): 1260–4. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.317. PMID 12748495.

- Jackson ND, Rosenblatt PL (December 1994). "Use of Interceed Absorbable Adhesion Barrier for vaginoplasty". Obstet Gynecol. 84 (6): 1048–50. PMID 7970464.

- ^ Steiner E, Woernle F, Kuhn W, Beckmann K, Schmidt M, Pilch H, Knapstein PG (January 2002). "Carcinoma of the neovagina: case report and review of the literature". Gynecol. Oncol. 84 (1): 171–5. doi:10.1006/gyno.2001.6417. PMID 11748997.

- ^ Breech LL (2008). "Complications of vaginoplasty and clitoroplasty". In Teich S, Caniano DA (eds.). Reoperative pediatric surgery. Totowa, N.J: Humana. pp. 499–514. ISBN 978-1-58829-761-7.

- ^ Mendoza N, Motos MA (January 2013). "Androgen insensitivity syndrome". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 29 (1): 1–5. doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.705378. PMID 22812659.

- ^ Mendoza, Nicolas; Rodriguez-Alcalá, Cristina; Motos, Miguel Angel; Salamanca, Alberto (2017). "Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: An Update on the Management of Adolescents and Young People". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 30 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.08.013. ISSN 1083-3188.

- Imperato-McGinley J, Canovatchel WJ (April 1992). "Complete androgen insensitivity Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management". Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 3 (3): 75–81. doi:10.1016/1043-2760(92)90016-T. PMID 18407082.

- ^ Patterson, Mark N.; McPhaul, Michael J.; Hughes, Ieuan A. (1994). "8 Androgen insensitivity syndrome". Baillière's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 8 (2): 379–404. doi:10.1016/S0950-351X(05)80258-7. ISSN 0950-351X. PMID 8092978.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Information

- androgen at NIH/UW GeneTests

- An Australian parent/patient booklet on CAIS (archived)

- The Secret of My Sex news article

- Women With Male DNA All Female news article at ABCnews.com

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement

| X-linked disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Genetic disorders relating to deficiencies of transcription factor or coregulators | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Basic domains |

| ||||||||

| (2) Zinc finger DNA-binding domains |

| ||||||||

| (3) Helix-turn-helix domains |

| ||||||||

| (4) β-Scaffold factors with minor groove contacts |

| ||||||||

| (0) Other transcription factors |

| ||||||||

| Ungrouped | |||||||||

| Transcription coregulators |

| ||||||||