| Revision as of 20:32, 27 January 2021 editAlej27 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users771 edits Added section showing how to convert a practical delta generator to a practical wye generator. Also added a note on the demonstration (which is in the talk page). Also renamed the previous sections "Notes" to "References", and "References" to "Bibliography".← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:30, 19 December 2024 edit undo依仁 (talk | contribs)3 editsNo edit summary | ||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 20 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Technique in electrical circuit analysis}} | |||

| {{about|the mathematical technique|the device which transforms three-phase electric power |

{{about|an application of a mathematical technique in electrical engineering|the mathematical technique itself|YΔ- and ΔY-transformations|the device which transforms three-phase electric power |delta-wye transformer|the application in statistical mechanics|Yang–Baxter equation|the regional airline brand name for Delta Air Lines|Delta Connection}} | ||

| {{Technical|date=January 2021}} | |||

| ⚫ | In ], the '''Y-Δ transform''', also written '''wye-delta''' and also known by many other names, is a mathematical technique to simplify ] of an ]. The name derives from the shapes of the ]s, which look respectively like the letter Y and the Greek capital letter ]. This circuit transformation theory was published by ] in 1899.<ref>{{cite journal |first=A. E. |last=Kennelly |title=Equivalence of triangles and three-pointed stars in conducting networks |journal=Electrical World and Engineer |volume=34 |pages=413–414 |year=1899}}</ref> It is widely used in analysis of ] circuits. | ||

| The equations look nice but this is too much for ordinary Misplaced Pages. The encyclopedic articles are concise and simple. The mathematical equations are usually presented in their final form; special mathematical and/or technical encyclopedias usually hold complex, step-by-step development of mathematical equations. | |||

| ⚫ | The Y-Δ transform can be considered a special case of the ] for three ]s. In mathematics, the Y-Δ transform plays an important role in theory of circular ]s.<ref>{{Cite journal|doi = 10.1016/S0024-3795(98)10087-3|title = Circular planar graphs and resistor networks|year = 1998|last1 = Curtis|first1 = E.B.|last2 = Ingerman|first2 = D.|last3 = Morrow|first3 = J.A.|journal = Linear Algebra and Its Applications|volume = 283|issue = 1–3|pages = 115–150|doi-access = free}}</ref> | ||

| Sections "A proof of the existence and uniqueness of the transformation" and "Demonstration" are overkill. | |||

| Thank you, | |||

| Marino 20:59, 11 January 2021 (UTC)}} | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The Y-Δ transform can be considered a special case of the ] for three ]. In mathematics, the Y-Δ transform plays an important role in theory of ].<ref>{{Cite journal|doi = 10.1016/S0024-3795(98)10087-3|title = Circular planar graphs and resistor networks|year = 1998|last1 = Curtis|first1 = E.B.|last2 = Ingerman|first2 = D.|last3 = Morrow|first3 = J.A.|journal = Linear Algebra and Its Applications|volume = 283|issue = 1–3|pages = 115–150|doi-access = free}}</ref> | ||

| ==Names== | ==Names== | ||

| Line 17: | Line 13: | ||

| ==Basic Y-Δ transformation== | ==Basic Y-Δ transformation== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The transformation is used to establish equivalence for networks with three terminals. Where three elements terminate at a common node and none are sources, the node is eliminated by transforming the impedances. For equivalence, the impedance between any pair of terminals must be the same for both networks. The equations given here are valid for complex as well as real impedances. | The transformation is used to establish equivalence for networks with three terminals. Where three elements terminate at a common node and none are sources, the node is eliminated by transforming the impedances. For equivalence, the impedance between any pair of terminals must be the same for both networks. The equations given here are valid for complex as well as real impedances. ] is a quantity measured in ]s which represents resistance as positive real numbers in the usual manner, and also represents ] as positive and negative ]s. | ||

| ===Equations for the transformation from Δ to Y===<!--This section is linked from ]. Changing this heading will break the template unless updated there also.--> | ===Equations for the transformation from Δ to Y===<!--This section is linked from ]. Changing this heading will break the template unless updated there also.--> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 20: | ||

| :<math>R_\text{Y} = \frac{R'R''}{\sum R_\Delta}</math> | :<math>R_\text{Y} = \frac{R'R''}{\sum R_\Delta}</math> | ||

| where <math>R_\Delta</math> are all impedances in the Δ circuit. This yields the specific |

where <math>R_\Delta</math> are all impedances in the Δ circuit. This yields the specific formula | ||

| :<math>\begin{align} | :<math>\begin{align} | ||

| Line 40: | Line 36: | ||

| :<math>\begin{align} | :<math>\begin{align} | ||

| R_\text{a} &= \frac{R_1 R_2 + R_2 R_3 + R_3 R_1}{R_1} \\ | R_\text{a} &= \frac{R_1 R_2 + R_2 R_3 + R_3 R_1}{R_1} = R_2+R_3+\frac{R_2R_3}{R_1} \\ | ||

| R_\text{b} &= \frac{R_1 R_2 + R_2 R_3 + R_3 R_1}{R_2} \\ | R_\text{b} &= \frac{R_1 R_2 + R_2 R_3 + R_3 R_1}{R_2} = R_1+R_3+\frac{R_1R_3}{R_2} \\ | ||

| R_\text{c} &= \frac{R_1 R_2 + R_2 R_3 + R_3 R_1}{R_3} | R_\text{c} &= \frac{R_1 R_2 + R_2 R_3 + R_3 R_1}{R_3} = R_1+R_2+\frac{R_1R_2}{R_3} | ||

| \end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

| Or, if using admittance instead of resistance: | Or, if using ] instead of resistance: | ||

| :<math>\begin{align} | :<math>\begin{align} | ||

| Y_\text{a} &= \frac{Y_3 Y_2}{\sum Y_\text{Y}} \\ | Y_\text{a} &= \frac{Y_3 Y_2}{\sum Y_\text{Y}} \\ | ||

| Line 83: | Line 79: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Every two-terminal network represented by a ] can be reduced to a single equivalent resistor by a sequence of series, parallel, Y-Δ, and Δ-Y transformations.<ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.1002/jgt.3190130202|title=On the delta-wye reduction for planar graphs|year=1989|last1=Truemper|first1=K.|journal=Journal of Graph Theory|volume=13|issue=2|pages=141–148}}</ref> However, there are non-planar networks that cannot be simplified using these transformations, such as a regular square grid wrapped around a ], or any member of the ]. | Every two-terminal network represented by a ] can be reduced to a single equivalent resistor by a sequence of series, parallel, Y-Δ, and Δ-Y transformations.<ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.1002/jgt.3190130202|title=On the delta-wye reduction for planar graphs|year=1989|last1=Truemper|first1=K.|journal=]|volume=13|issue=2|pages=141–148}}</ref> However, there are non-planar networks that cannot be simplified using these transformations, such as a regular square grid wrapped around a ], or any member of the ]. | ||

| ==Graph theory== | ==Graph theory== | ||

| Line 198: | Line 194: | ||

| ==Δ to Y transformation of a practical generator== | ==Δ to Y transformation of a practical generator== | ||

| During the analysis of balanced three-phase power systems, usually an equivalent per-phase (or single-phase) is analyzed instead due to its simplicity. For that, equivalent wye connections are used for generators, transformers, loads and motors. The stator windings of a practical delta-connected three-phase generator, shown in the following figure, can be converted to an equivalent wye-connected generator, using the six following formulas{{ |

During the analysis of balanced ] ], usually an equivalent per-phase (or single-phase) circuit is analyzed instead due to its simplicity. For that, equivalent wye connections are used for ], ], loads and ]. The stator windings of a practical delta-connected three-phase generator, shown in the following figure, can be converted to an equivalent wye-connected generator, using the six following formulas{{efn|For a demonstration, read the ].}}: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| <math> | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| \begin{align} | |||

| & Z_\text{s1Y} = \dfrac{Z_\text{s1} \, Z_\text{s3}}{Z_\text{s1} + Z_\text{s2} + Z_\text{s3}} \\ | |||

| ⚫ | & Z_\text{s2Y} = \dfrac{Z_\text{s1} \, Z_\text{s2}}{Z_\text{s1} + Z_\text{s2} + Z_\text{s3}} \\ | ||

| & Z_\text{s3Y} = \dfrac{Z_\text{s2} \, Z_\text{s3}}{Z_\text{s1} + Z_\text{s2} + Z_\text{s3}} \\ | |||

| ⚫ | & V_\text{s1Y} = \left( \dfrac{V_\text{s1}}{Z_\text{s1}} - \dfrac{V_\text{s3}}{Z_\text{s3}} \right) Z_\text{s1Y} \\ | ||

| & V_\text{s2Y} = \left( \dfrac{V_\text{s2}}{Z_\text{s2}} - \dfrac{V_\text{s1}}{Z_\text{s1}} \right) Z_\text{s2Y} \\ | |||

| ⚫ | & V_\text{s3Y} = \left( \dfrac{V_\text{s3}}{Z_\text{s3}} - \dfrac{V_\text{s2}}{Z_\text{s2}} \right) Z_\text{s3Y} | ||

| \end{align} | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| </math> | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| The resulting network is the following. The neutral node of the equivalent network is fictitious, and so are the line-to-neutral phasor voltages. During the transformation, the line phasor currents and the line (or line-to-line or phase-to-phase) phasor voltages are not altered. | The resulting network is the following. The neutral node of the equivalent network is fictitious, and so are the line-to-neutral phasor voltages. During the transformation, the line phasor currents and the line (or line-to-line or phase-to-phase) phasor voltages are not altered. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| If the actual delta generator is balanced, meaning that the internal phasor voltages have the same magnitude and are phase-shifted by 120° between each other and the three complex impedances are the same, then the previous formulas reduce to the four following: | If the actual delta generator is balanced, meaning that the internal phasor voltages have the same magnitude and are phase-shifted by 120° between each other and the three complex impedances are the same, then the previous formulas reduce to the four following: | ||

| <math> | |||

| <math>{\hat Z}_\text{sY} = \dfrac{{\hat Z}_\text{s}}{3}</math> | |||

| \begin{align} | |||

| & Z_\text{sY} = \dfrac{Z_\text{s}}{3}\\ | |||

| ⚫ | & V_\text{s1Y} = \dfrac{V_\text{s1}}{\sqrt{3} \, \angle \pm 30^\circ} \\ | ||

| & V_\text{s2Y} = \dfrac{V_\text{s2}}{\sqrt{3} \, \angle \pm 30^\circ} \\ | |||

| & V_\text{s3Y} = \dfrac{V_\text{s3}}{\sqrt{3} \, \angle \pm 30^\circ} | |||

| \end{align} | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| </math> | |||

| where for the last three equations, the first sign ( |

where for the last three equations, the first sign (+) is used if the phase sequence is positive/''abc'' or the second sign (−) is used if the phase sequence is negative/''acb''. | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 240: | Line 236: | ||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| :1.{{note|a}}For a demonstration, read . | |||

| ==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

Latest revision as of 04:30, 19 December 2024

Technique in electrical circuit analysis This article is about an application of a mathematical technique in electrical engineering. For the mathematical technique itself, see YΔ- and ΔY-transformations. For the device which transforms three-phase electric power, see delta-wye transformer. For the application in statistical mechanics, see Yang–Baxter equation. For the regional airline brand name for Delta Air Lines, see Delta Connection.| This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (January 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In circuit design, the Y-Δ transform, also written wye-delta and also known by many other names, is a mathematical technique to simplify the analysis of an electrical network. The name derives from the shapes of the circuit diagrams, which look respectively like the letter Y and the Greek capital letter Δ. This circuit transformation theory was published by Arthur Edwin Kennelly in 1899. It is widely used in analysis of three-phase electric power circuits.

The Y-Δ transform can be considered a special case of the star-mesh transform for three resistors. In mathematics, the Y-Δ transform plays an important role in theory of circular planar graphs.

Names

The Y-Δ transform is known by a variety of other names, mostly based upon the two shapes involved, listed in either order. The Y, spelled out as wye, can also be called T or star; the Δ, spelled out as delta, can also be called triangle, Π (spelled out as pi), or mesh. Thus, common names for the transformation include wye-delta or delta-wye, star-delta, star-mesh, or T-Π.

Basic Y-Δ transformation

The transformation is used to establish equivalence for networks with three terminals. Where three elements terminate at a common node and none are sources, the node is eliminated by transforming the impedances. For equivalence, the impedance between any pair of terminals must be the same for both networks. The equations given here are valid for complex as well as real impedances. Complex impedance is a quantity measured in ohms which represents resistance as positive real numbers in the usual manner, and also represents reactance as positive and negative imaginary values.

Equations for the transformation from Δ to Y

The general idea is to compute the impedance at a terminal node of the Y circuit with impedances , to adjacent nodes in the Δ circuit by

where are all impedances in the Δ circuit. This yields the specific formula

Equations for the transformation from Y to Δ

The general idea is to compute an impedance in the Δ circuit by

where is the sum of the products of all pairs of impedances in the Y circuit and is the impedance of the node in the Y circuit which is opposite the edge with . The formulae for the individual edges are thus

Or, if using admittance instead of resistance:

Note that the general formula in Y to Δ using admittance is similar to Δ to Y using resistance.

A proof of the existence and uniqueness of the transformation

The feasibility of the transformation can be shown as a consequence of the superposition theorem for electric circuits. A short proof, rather than one derived as a corollary of the more general star-mesh transform, can be given as follows. The equivalence lies in the statement that for any external voltages ( and ) applying at the three nodes ( and ), the corresponding currents ( and ) are exactly the same for both the Y and Δ circuit, and vice versa. In this proof, we start with given external currents at the nodes. According to the superposition theorem, the voltages can be obtained by studying the superposition of the resulting voltages at the nodes of the following three problems applied at the three nodes with current:

- and

The equivalence can be readily shown by using Kirchhoff's circuit laws that . Now each problem is relatively simple, since it involves only one single ideal current source. To obtain exactly the same outcome voltages at the nodes for each problem, the equivalent resistances in the two circuits must be the same, this can be easily found by using the basic rules of series and parallel circuits:

Though usually six equations are more than enough to express three variables () in term of the other three variables(), here it is straightforward to show that these equations indeed lead to the above designed expressions.

In fact, the superposition theorem establishes the relation between the values of the resistances, the uniqueness theorem guarantees the uniqueness of such solution.

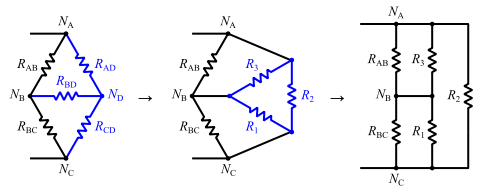

Simplification of networks

Resistive networks between two terminals can theoretically be simplified to a single equivalent resistor (more generally, the same is true of impedance). Series and parallel transforms are basic tools for doing so, but for complex networks such as the bridge illustrated here, they do not suffice.

The Y-Δ transform can be used to eliminate one node at a time and produce a network that can be further simplified, as shown.

The reverse transformation, Δ-Y, which adds a node, is often handy to pave the way for further simplification as well.

Every two-terminal network represented by a planar graph can be reduced to a single equivalent resistor by a sequence of series, parallel, Y-Δ, and Δ-Y transformations. However, there are non-planar networks that cannot be simplified using these transformations, such as a regular square grid wrapped around a torus, or any member of the Petersen family.

Graph theory

In graph theory, the Y-Δ transform means replacing a Y subgraph of a graph with the equivalent Δ subgraph. The transform preserves the number of edges in a graph, but not the number of vertices or the number of cycles. Two graphs are said to be Y-Δ equivalent if one can be obtained from the other by a series of Y-Δ transforms in either direction. For example, the Petersen family is a Y-Δ equivalence class.

Demonstration

Δ-load to Y-load transformation equations

To relate from Δ to from Y, the impedance between two corresponding nodes is compared. The impedance in either configuration is determined as if one of the nodes is disconnected from the circuit.

The impedance between N1 and N2 with N3 disconnected in Δ:

To simplify, let be the sum of .

Thus,

The corresponding impedance between N1 and N2 in Y is simple:

hence:

- (1)

Repeating for :

- (2)

and for :

- (3)

From here, the values of can be determined by linear combination (addition and/or subtraction).

For example, adding (1) and (3), then subtracting (2) yields

For completeness:

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

Y-load to Δ-load transformation equations

Let

- .

We can write the Δ to Y equations as

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

Multiplying the pairs of equations yields

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

and the sum of these equations is

- (7)

Factor from the right side, leaving in the numerator, canceling with an in the denominator.

- (8)

Note the similarity between (8) and {(1), (2), (3)}

Divide (8) by (1)

which is the equation for . Dividing (8) by (2) or (3) (expressions for or ) gives the remaining equations.

Δ to Y transformation of a practical generator

During the analysis of balanced three-phase power systems, usually an equivalent per-phase (or single-phase) circuit is analyzed instead due to its simplicity. For that, equivalent wye connections are used for generators, transformers, loads and motors. The stator windings of a practical delta-connected three-phase generator, shown in the following figure, can be converted to an equivalent wye-connected generator, using the six following formulas:

The resulting network is the following. The neutral node of the equivalent network is fictitious, and so are the line-to-neutral phasor voltages. During the transformation, the line phasor currents and the line (or line-to-line or phase-to-phase) phasor voltages are not altered.

If the actual delta generator is balanced, meaning that the internal phasor voltages have the same magnitude and are phase-shifted by 120° between each other and the three complex impedances are the same, then the previous formulas reduce to the four following:

where for the last three equations, the first sign (+) is used if the phase sequence is positive/abc or the second sign (−) is used if the phase sequence is negative/acb.

See also

- Star-mesh transform

- Network analysis (electrical circuits)

- Electrical network, three-phase power, polyphase systems for examples of Y and Δ connections

- AC motor for a discussion of the Y-Δ starting technique

References

- Kennelly, A. E. (1899). "Equivalence of triangles and three-pointed stars in conducting networks". Electrical World and Engineer. 34: 413–414.

- Curtis, E.B.; Ingerman, D.; Morrow, J.A. (1998). "Circular planar graphs and resistor networks". Linear Algebra and Its Applications. 283 (1–3): 115–150. doi:10.1016/S0024-3795(98)10087-3.

- Truemper, K. (1989). "On the delta-wye reduction for planar graphs". Journal of Graph Theory. 13 (2): 141–148. doi:10.1002/jgt.3190130202.

Notes

- For a demonstration, read the Talk page.

Bibliography

- William Stevenson, Elements of Power System Analysis 3rd ed., McGraw Hill, New York, 1975, ISBN 0-07-061285-4

External links

- Star-Triangle Conversion: Knowledge on resistive networks and resistors

- Calculator of Star-Triangle transform

at a terminal node of the Y circuit with impedances

at a terminal node of the Y circuit with impedances  ,

,  to adjacent nodes in the Δ circuit by

to adjacent nodes in the Δ circuit by

are all impedances in the Δ circuit. This yields the specific formula

are all impedances in the Δ circuit. This yields the specific formula

is the sum of the products of all pairs of impedances in the Y circuit and

is the sum of the products of all pairs of impedances in the Y circuit and  is the impedance of the node in the Y circuit which is opposite the edge with

is the impedance of the node in the Y circuit which is opposite the edge with

and

and  ) applying at the three nodes (

) applying at the three nodes ( and

and  ), the corresponding currents (

), the corresponding currents ( and

and  ) are exactly the same for both the Y and Δ circuit, and vice versa. In this proof, we start with given external currents at the nodes. According to the superposition theorem, the voltages can be obtained by studying the superposition of the resulting voltages at the nodes of the following three problems applied at the three nodes with current:

) are exactly the same for both the Y and Δ circuit, and vice versa. In this proof, we start with given external currents at the nodes. According to the superposition theorem, the voltages can be obtained by studying the superposition of the resulting voltages at the nodes of the following three problems applied at the three nodes with current:

and

and

. Now each problem is relatively simple, since it involves only one single ideal current source. To obtain exactly the same outcome voltages at the nodes for each problem, the equivalent resistances in the two circuits must be the same, this can be easily found by using the basic rules of

. Now each problem is relatively simple, since it involves only one single ideal current source. To obtain exactly the same outcome voltages at the nodes for each problem, the equivalent resistances in the two circuits must be the same, this can be easily found by using the basic rules of

) in term of the other three variables(

) in term of the other three variables( ), here it is straightforward to show that these equations indeed lead to the above designed expressions.

), here it is straightforward to show that these equations indeed lead to the above designed expressions.

from Δ to

from Δ to  from Y, the impedance between two corresponding nodes is compared. The impedance in either configuration is determined as if one of the nodes is disconnected from the circuit.

from Y, the impedance between two corresponding nodes is compared. The impedance in either configuration is determined as if one of the nodes is disconnected from the circuit.

be the sum of

be the sum of

(1)

(1) :

:

(2)

(2) :

:

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4) (5)

(5) (6)

(6) (3)

(3) (4)

(4) (5)

(5) (6)

(6) (7)

(7) from the right side, leaving

from the right side, leaving  (8)

(8)

. Dividing (8) by (2) or (3) (expressions for

. Dividing (8) by (2) or (3) (expressions for  or

or  ) gives the remaining equations.

) gives the remaining equations.