| Revision as of 23:39, 26 June 2023 view sourceDoughbo (talk | contribs)472 edits →Legacy: See Talk:Ernest Rutherford/GA1. Removed redundant content which is already included in outlinked articles.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:53, 22 January 2025 view source Kurzon (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users23,369 edits →Development of proton and neutron theoryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| (239 intermediate revisions by 59 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|New Zealand physicist (1871–1937)}} | {{Short description|New Zealand physicist (1871–1937)}} | ||

| {{redirect-distinguish|Lord Rutherford|Lord Rutherfurd|Andrew Rutherford, 1st Earl of Teviot}} | {{redirect-distinguish|Lord Rutherford|Lord Rutherfurd|Andrew Rutherford, 1st Earl of Teviot}} | ||

| {{pp-move |

{{pp-move}} | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | {{pp-semi-indef}} | ||

| {{Use New Zealand English|date=August 2016}} | {{Use New Zealand English|date=August 2016}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2022}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2022}} | ||

| {{Infobox officeholder | |||

| | honorific_prefix = ] | |||

| | name = The Lord Rutherford of Nelson | |||

| | honorific_suffix = {{postnominals|country=GBR|size=100%|OM|FRS|HFRSE}} | |||

| | image = Sir Ernest Rutherford LCCN2014716719 - restoration1.jpg | |||

| | caption = Rutherford, {{circa|1920s}} | |||

| | order = 44th | |||

| | office = President of the Royal Society | |||

| | term_start = 1925 | |||

| | term_end = 1930 | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|df=y|1871|8|30}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|df=y|1937|10|19|1871|8|30}} | |||

| | death_place = ], England | |||

| | resting_place = ], ] | |||

| {{Infobox scientist | {{Infobox scientist | ||

| | embed = yes | |||

| | honorific-prefix = ] | |||

| | |

| alma_mater = ]<br>] | ||

| | known_for = {{plainlist| | |||

| | honorific-suffix = {{postnominals|country=GBR|size=100%|OM|PRS|HFRSE}} | |||

| * Coining the term '']'' | |||

| | image = Sir Ernest Rutherford LCCN2014716719 - restoration1.jpg | |||

| * Coining the term '']'' | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| * Describing ] | |||

| | caption = Rutherford {{circa|1920s}} | |||

| * Directing the ] | |||

| | birth_name = Ernest Rutherford | |||

| * Discovering the ] | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|df=yes|1871|8|30}} | |||

| * Discovering the ] | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| * Discovering ] | |||

| | death_date = {{nowrap|{{death date and age|df=yes|1937|10|19|1871|8|30}}}} | |||

| * Inventing ] | |||

| | death_place = ], England | |||

| * Performing the first ] and ] | |||

| | resting_place = ] | |||

| * Proposing the ] | |||

| | citizenship = <!-- use only when necessary per ] --> | |||

| | nationality = | |||

| | fields = {{cslist|]|]|]}} | |||

| | workplaces = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | spouse = {{marriage|Mary Georgina Newton|1900|<!-- 1937, ''his death'' -->}} | |||

| |alma_mater = {{plainlist| | |||

| | children = 1 <!-- daughter (Eileen Mary Rutherford) --> | |||

| * ] | |||

| | relatives = ] (son-in-law) | |||

| * ], University of Cambridge | |||

| | awards = {{collapsible list|title={{nobold|''See list''}}|{{ubl|]|] (1904, 1920)|] (1904)|] (1908)|] (1910)|] (1910)|] (1911)|] (1913)|] (1916)|] (1919)|] (1922)|] (1924)|] (1925)|] (1928)|] (1930)| ] (1936)|] (1936)}}}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | fields = ]<br>] | |||

| |doctoral_advisor = <!--There was no PhD at Cambridge until 1919--> | |||

| | work_institutions = {{ubl|]|]|University of Cambridge}} | |||

| |academic_advisors = {{plainlist| | |||

| | doctoral_advisor = <!--There was no PhD at Cambridge until 1919--> | |||

| | academic_advisors = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ]<ref name="aps"> | |||

| * ]<ref name="aps"> American Physical Society 2017</ref>}} | |||

| {{Cite web|url=https://www.aps.org/programs/outreach/history/historicsites/rutherfordsoddy.cfm |title=Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201041955/https://www.aps.org/programs/outreach/history/historicsites/rutherfordsoddy.cfm |archive-date=1 December 2017 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| |doctoral_students = {{collapsible list|title={{nobold|''See list''}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | doctoral_students = {{collapsible list|title={{nobold|''See list''}}|{{ubl|]<ref name=UofPunjab>{{Cite web |title=University of the Punjab - Science |url=http://pu.edu.pk/home/department/55/Department-of-Physics |access-date=2023-09-15 |website=pu.edu.pk |quote="The expedition included Professor James Martin Benade (Professor of Physics at Forman Christian College Lahore) and Dr. Nazir Ahmad (a PhD student of Ernest Rutherford at Cambridge who later on became the First Chairman of Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission in 1956). " |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002053440/http://pu.edu.pk/home/department/55/Department-of-Physics |url-status=live }}</ref>|]|]|]|]|]<ref name="comsats">{{Cite web |editor-last1=Hameed |editor-first1=A. Khan |editor-last2=Qurashi |editor-first2=M. M. |editor-last3=Hussain |editor-first3=E. T. |editor-last4=Hayee |editor-first4=M. I. |title=Physics in Developing Countries – Past, Present & Future |url=https://comsats.org/Publications/Books_SnT_Series/08.%20Physics%20in%20Developing%20Countries%20-%20Past,%20Present%20and%20Future%20(April%202006).pdf |year=2006 |series=COMSATS Series of Publications on Science and Technology |website=] |access-date=2 October 2023 |archive-date=22 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230922031259/http://www.comsats.org/Publications/Books_SnT_Series/08.%20Physics%20in%20Developing%20Countries%20-%20Past,%20Present%20and%20Future%20(April%202006).pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="chair">{{Cite web |last=((Government College University, Lahore (GCU))) |author-link=Government College University, Lahore |title=Dr. Rafi Muhammad Chaudhri Chair in Physics – About the Chair |url=http://www.gcu.edu.pk/RafiCh_Chair.htm |date=4 September 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160316200831/http://www.gcu.edu.pk/RafiCh_Chair.htm |archive-date=16 March 2016 |url-status=dead |work=Chief Librarian GC University Library, Lahore |publisher=GC University | access-date=2 October 2023}}</ref>|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Grodzins |first1=Lee |title=Obituaries: Zhang Wen-Yu |journal=Physics Today |date=February 1994 |volume=47 |issue=2 |page=116 |doi=10.1063/1.2808417 |quote=Zhang studied under Ernest Rutherford in the mid-1930s, receiving his degree from Cambridge University in 1938.|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author1=Zhang Wenyu ({{lang|zh|张文裕}}) |url=https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2047688 |script-title=zh:高能实验物理学家张文裕:回忆导师卢瑟福生命中的最后两年 |work=thepaper.com |date=28 March 2018 |access-date=12 August 2021 |language=zh |archive-date=12 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210812083603/https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2047688 |url-status=live }}</ref>}}}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | notable_students = {{collapsible list|title={{nobold|''See list''}}|{{ubl|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|] <!-- verified https://doi.org/10.1007/s12045-020-1037-4 and https://www.researchgate.net/profile/N-Panchapakesan/publication/276326833_Professor_DS_Kothari_and_the_University_of_Delhi/links/5ae4232e458515760abe8c98/Professor-DS-Kothari-and-the-University-of-Delhi.pdf -->|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}}}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| {{Infobox officeholder | |||

| | ] | |||

| | embed = yes | |||

| | ] | |||

| | order2 = 4th | |||

| | ] | |||

| | office2 = Cavendish Professor of Physics | |||

| | ] | |||

| | term_start2 = 1919 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | term_end2 = 1937 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | predecessor2 = J. J. Thomson | |||

| | ] | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Grodzins |first1=Lee |title=Obituaries: Zhang Wen-Yu |journal=Physics Today |date=February 1994 |volume=47 |issue=2 |page=116 |doi=10.1063/1.2808417 |url=https://physicstoday.scitation.org/doi/pdf/10.1063/1.2808417 |access-date=28 January 2023 |quote=Zhang studied under Ernest Rutherford in the mid-1930s, receiving his degree from Cambridge University in 1938.}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|author1=Zhang Wenyu ({{lang|zh|张文裕}})|url=https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2047688 |script-title=zh:高能实验物理学家张文裕:回忆导师卢瑟福生命中的最后两年 |work=thepaper.com |date=28 March 2018 |access-date=12 August 2021 |language=zh}}</ref> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | signature = Ernest-Rutherford-signature.svg | |||

| |notable_students = {{collapsible list|title={{nobold|''See list''}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| |known_for = {{collapsible list|title={{nobold|''See list''}} | |||

| | Discovery of ] and ] | |||

| | Discovery of ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |influences = | |||

| |influenced = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |awards = {{collapsible list|title={{nobold|''See list''}} | |||

| | ] (1904) | |||

| | ] (1908) | |||

| | ] (1910) | |||

| | ] (1910) | |||

| | ] (1911) | |||

| | ] (1913) | |||

| | ] (1916) | |||

| | ] (1919) | |||

| | ] (1922) | |||

| | ] (1924) | |||

| | ] (1928) | |||

| | ] (1930) | |||

| | ] (1936) | |||

| | ] (1936) | |||

| }} | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|Mary Georgina Newton|1900|<!-- 1937, ''his death'' -->}} | |||

| | children = 1 <!-- daughter (Eileen Mary Rutherford) --> | |||

| | module = {{Infobox officeholder|embed=yes | |||

| | office = ] | |||

| | term_start = 1925 | |||

| | term_end = 1930 | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ]}} | |||

| | signature = ernest rutherford sig.jpg | |||

| | footnotes = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Nuclear physics}} | |||

| '''Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson''' |

'''Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson''' (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand ] who was a pioneering researcher in both ] and ]. He has been described as "the father of nuclear physics",<ref name=Father/> and "the greatest ] since ]".<ref name="eb">{{cite web |last1=Badash |first1=Lawrence |title=Ernest Rutherford {{!}} Accomplishments, Atomic Theory, & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ernest-Rutherford |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=23 June 2023 |language=en |archive-date=26 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220926002932/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ernest-Rutherford |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1908, he was awarded the ] "for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances." He was the first ]n Nobel laureate, and the first to perform the awarded work in ]. | ||

| Rutherford's discoveries include the concept of radioactive ], the radioactive element ], and the differentiation and naming of ] and ]. Together with ], Rutherford is credited with proving that alpha radiation is composed of ] nuclei.<ref name=rutherford.org.nz>{{cite web|last=Campbell|first=John|title=Rutherford – A Brief Biography|url=http://www.rutherford.org.nz/biography.htm|website=Rutherford.org.nz|access-date=4 March 2013|archive-date=12 May 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200512125601/https://www.rutherford.org.nz/biography.htm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1080/14786440808636511| title = Spectrum of the radium emanation| journal = Philosophical Magazine| series = Series 6| volume = 16| issue = 92| pages = 313| year = 1908| last1 = Rutherford| first1 = E.| last2 = Royds| first2 = T.| url = https://zenodo.org/record/1430840| access-date = 28 June 2019| archive-date = 23 December 2019| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191223010722/https://zenodo.org/record/1430840| url-status = live}}</ref> In 1911, he theorized that atoms have their charge concentrated in a very small ].<ref>{{cite book |title = Theoretical concepts in physics: an alternative view of theoretical reasoning in physics |last = Longair |first = M. S. |publisher = Cambridge University Press |year = 2003 |isbn = 978-0-521-52878-8 |pages = 377–378 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=bA9Lp2GH6OEC&pg=PA377 |access-date = 11 May 2020 |archive-date = 30 October 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20231030224745/https://books.google.com/books?id=bA9Lp2GH6OEC&pg=PA377#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status = live }}</ref> He arrived at this theory through his discovery and interpretation of ] during the ] performed by ] and ]. In 1912 he invited ] to join his lab, leading to the ] of the ]. In 1917, he performed the first artificially induced ] by conducting experiments in which nitrogen nuclei were bombarded with alpha particles. These experiments led him to discover the emission of a subatomic particle that he initially called the "hydrogen atom", but later (more precisely) renamed the ].<ref>{{Cite journal|doi = 10.1080/14786440608635919|title = Collision of α particles with light atoms. IV. An anomalous effect in nitrogen|journal = The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science|series = Series 6|volume = 37|issue = 222|pages = 581–587|year = 1919|last1 = Rutherford|first1 = E.|url = https://zenodo.org/record/1430800|access-date = 2 November 2019|archive-date = 2 November 2019|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191102172157/https://zenodo.org/record/1430800|url-status = live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |doi = 10.1098/rspa.1920.0040|title = Bakerian Lecture. Nuclear Constitution of Atoms|journal = Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences|volume = 97|issue = 686|pages = 374–400|year = 1920|last1 = Rutherford|first1 = E.|bibcode = 1920RSPSA..97..374R|doi-access = free}}</ref> He is also credited with developing the ] alongside ]. His other achievements include advancing the fields of ] communications and ] technology. | |||

| Rutherford's discoveries include the concept of radioactive ], the radioactive element ],<ref name="Cheremisinoff2016">{{cite book|author=Nicholas P. Cheremisinoff|title=Pollution Control Handbook for Oil and Gas Engineering|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WQcEDAAAQBAJ&pg=PT886|date=20 April 2016|publisher=Wiley|isbn=978-1-119-11788-9|pages=886–}}</ref> and the differentiation and naming of ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|title=The Discovery of Radioactivity|url=http://www.lbl.gov/abc/wallchart/chapters/03/4.html|date= 9 August 2000|website=lbl.gov}}</ref> | |||

| Rutherford became Director of the ] at the ] in 1919. Under his leadership, the ] was discovered by ] in 1932. In the same year, the first controlled experiment to split the nucleus was performed by ] and ], working under his direction. In honour of his scientific advancements, Rutherford was recognised as a ] of the United Kingdom. After his death in 1937, he was buried in ] near ] and ]. The chemical element ] (<sub>104</sub>Rf) was named after him in 1997. | |||

| Together with ], Rutherford is credited with proving that alpha radiation is ] nuclei.<ref name=rutherford.org.nz>{{cite web|last=Campbell|first=John|title=Rutherford – A Brief Biography |url=http://www.rutherford.org.nz/biography.htm|website=Rutherford.org.nz|access-date=4 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1080/14786440808636511| title = Spectrum of the radium emanation| journal = Philosophical Magazine |series=Series 6| volume = 16| issue = 92| pages = 313| year = 1908| last1 = Rutherford | first1 = E.| last2 = Royds | first2 = T.| url = https://zenodo.org/record/1430840}}</ref> In 1911, although he could not prove that it was positive or negative,<ref name=charge>{{Cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=E. |year=1911 |title=The scattering of α and β particles by matter and the structure of the atom |url = http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/rutherford/rutherford688.html |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |series=Series 6 |volume=21 |issue=125 |pages=669–688 |doi=10.1080/14786440508637080}}</ref> he theorized that atoms have their charge concentrated in a very small ],<ref>{{cite book |title = Theoretical concepts in physics: an alternative view of theoretical reasoning in physics |last= Longair |first=M. S. |publisher = Cambridge University Press |year = 2003 |isbn = 978-0-521-52878-8 |pages = 377–378 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=bA9Lp2GH6OEC&pg=PA377}}</ref> and thereby pioneered the ] of the ], through his discovery and interpretation of ] by the ] of ] and ]. | |||

| == Early life and education == | |||

| He performed the first artificially induced ] in 1917 in experiments where nitrogen nuclei were bombarded with alpha particles. As a result, he discovered the emission of a subatomic particle which, in 1919, he called the "hydrogen atom" but, in 1920, he more accurately named the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |doi = 10.1080/14786440608635919|title =Collision of α particles with light atoms. IV. An anomalous effect in nitrogen|journal = The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science|series=Series 6 |volume = 37|issue = 222|pages = 581–587|year = 1919|last1 = Rutherford|first1 = E.|url = https://zenodo.org/record/1430800}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |doi = 10.1098/rspa.1920.0040|title = Bakerian Lecture. Nuclear Constitution of Atoms|journal = Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences|volume = 97|issue = 686|pages = 374–400|year = 1920|last1 = Rutherford|first1 = E.|bibcode = 1920RSPSA..97..374R|doi-access = free}}</ref> | |||

| Ernest Rutherford was born on 30 August 1871 in ], a town near ], New Zealand.<ref name=McLintock/> He was the fourth of twelve children of James Rutherford, an immigrant farmer and mechanic from ], Scotland, and his wife Martha Thompson, a schoolteacher from ], England.<ref name=McLintock>{{cite encyclopedia|author=A.H. McLintock|encyclopedia=An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand|title=Rutherford, Sir Ernest (Baron Rutherford of Nelson, O.M., F.R.S.)|edition=1966|date=18 September 2007|url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/rutherford-sir-ernest/1|publisher=Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand|isbn=978-0-478-18451-8|access-date=2 April 2008|archive-date=3 December 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111203225115/http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/rutherford-sir-ernest/1|url-status=live|url-access=<!--WP:URLACCESS-->}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_vNW1wg9npgC&pg=PA12|page=12|author=J.L. Heilbron|title=Ernest Rutherford And the Explosion of Atoms|date=12 June 2003|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0-19-512378-6|access-date=22 February 2016|archive-date=29 August 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230829161018/https://books.google.com/books?id=_vNW1wg9npgC&pg=PA12|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> Rutherford's birth certificate was mistakenly written as 'Earnest'. He was known by his family as Ern.<ref name=McLintock/><ref name=":0">{{DNZB|last=Campbell|first=John|title=Rutherford, Ernest 1871–1937|id=3R37|access-date=4 April 2011}}</ref> | |||

| When Rutherford was five he moved to Foxhill, New Zealand, and attended Foxhill School. At age 11 in 1883, the Rutherford family moved to ], a town in the ]. The move was made to be closer to the flax mill Rutherford's father developed.<ref name=":0" /> Ernest studied at ].<ref>{{Cite news |date=7 October 1886 |title=Local and General News. |volume=22 |page=2 |work=] |issue=186 |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18861007.2.8? |access-date=October 1, 2023 |via=Papers Past |archive-date=8 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230808010845/https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18861007.2.8 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Rutherford became Director of the ] at the ] in 1919. Under his leadership the ] was discovered by ] in 1932 and in the same year the first experiment to split the nucleus in a fully controlled manner was performed by students working under his direction, ] and ]. | |||

| In 1887, on his second attempt, he won a scholarship to study at ].<ref name=":0" /> On his first examination attempt, he received 75 out of 130 marks for geography, 76 out of 130 for history, 101 out of 140 for English, and 200 out of 200 for arithmetic, totalling 452 out of 600 marks.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Results of Nelson Scholarships Examinations for December 1885. |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC18860102.2.30 |access-date=8 August 2023 |website=paperspast.natlib.govt.nz |archive-date=8 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230808010350/https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TC18860102.2.30 |url-status=live }}</ref> With these marks, he had the highest of anyone from Nelson.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Marlborough Express. Published Every Evening. Monday, December 28, 1885. Local and General News. |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18851228.2.5 |access-date=8 August 2023 |website=paperspast.natlib.govt.nz |archive-date=8 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230808010547/https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18851228.2.5 |url-status=live }}</ref> When he was awarded the scholarship, he had received 580 out of 600 possible marks.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Marlborough Express. Published Every Evening Wednesday, January 5, 1887. Local and General News. |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18870105.2.6 |access-date=8 August 2023 |website=paperspast.natlib.govt.nz |archive-date=8 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230808011211/https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18870105.2.6 |url-status=live }}</ref> After being awarded the scholarship, Havelock School presented him with a five-volume set of books titled ''The Peoples of the World''.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Papers Past {{!}} Newspapers {{!}} Marlborough Express {{!}} 25 January 1887 {{!}} Local and General News. |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18870125.2.6 |access-date=8 August 2023 |website=paperspast.natlib.govt.nz |archive-date=8 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230808011630/https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18870125.2.6 |url-status=live }}</ref> He studied at Nelson College between 1887 and 1889, and was head boy in 1889. He also played in the school's rugby team.<ref name=":0" /> He was offered a cadetship in government service, but he declined as he still had 15 months of college remaining.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Papers Past {{!}} Newspapers {{!}} Marlborough Express {{!}} 4 October 1887 {{!}} Marlborough Express. Published Every Evening.... |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18871004.2.7 |access-date=8 August 2023 |website=paperspast.natlib.govt.nz |archive-date=8 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230808011952/https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MEX18871004.2.7 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| After his death in 1937, he was buried in ] near ] and ]. '']'' considers him to be the greatest experimentalist since ] (1791–1867).<ref name="eb">{{cite web |last1=Badash |first1=Lawrence |title=Ernest Rutherford {{!}} Accomplishments, Atomic Theory, & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ernest-Rutherford |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=23 June 2023 |language=en}}</ref> The chemical element ] (element 104) was named after him in 1997. | |||

| In 1889, after his second attempt, he won a ] to study at ], ], between 1890 and 1894. He participated in its ] and the Science Society.<ref name=":0" /> At Canterbury, he was awarded a complex ] in Latin, English, and Maths in 1892, a ] in Mathematics and Physical Science in 1893, and a ] in Chemistry and Geology in 1894.<ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography">{{cite web |title=Ernest Rutherford Biographical |url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1908/rutherford/biographical/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230603075847/https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1908/rutherford/biographical/ |archive-date=3 June 2023 |url-status=live |website=The Nobel Prize |publisher=Nobel Prize Outreach AB |access-date=5 October 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Famous Canterbury graduate Ernest Rutherford turns 150 |url=https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/news/2021/famous-canterbury-graduate-ernest-rutherford-turns-150.html |website=The University of Canterbury |access-date=3 July 2023 |language=en-nz |date=27 August 2021 |archive-date=3 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230703222040/https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/news/2021/famous-canterbury-graduate-ernest-rutherford-turns-150.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Early life and education == | |||

| Ernest Rutherford was born at ], near ], New Zealand, to James Rutherford, a farmer, and his wife Martha Thompson, a schoolteacher.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|first=A.H.|last=McLintock|encyclopedia=An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand|title=Rutherford, Sir Ernest (Baron Rutherford of Nelson, O.M., F.R.S.)|edition=1966|date=18 September 2007|url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/rutherford-sir-ernest/1|publisher=Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand| isbn=978-0-478-18451-8|access-date=2 April 2008}}</ref><ref>By J.L. Heilbron – ''Ernest Rutherford And the Explosion of Atoms'' – Oxford University Press – {{ISBN|0-19-512378-6}}</ref> Both of his parents were immigrants: James from ], Scotland, and Martha from ], Essex, England. Rutherford's birth certificate incorrectly reads 'Earnest' due to a clerical error during registration.<ref>{{DNZB|last=Campbell|first=John|title=Rutherford, Ernest 1871–1937|id=3R37|access-date=4 April 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Rutherford first studied at ] and ] before winning a ] to study at ], ], where he participated in the ] and played ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|first=John|last=Campbell|encyclopedia=An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand|title=Rutherford, Ernest|date=30 October 2012|url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3r37/rutherford-ernest|publisher=Te Ara – The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand|access-date=1 October 2013}}</ref> He was awarded an ] in Mathematics and Physical Science from the Canterbury College in 1893 and received a ] from the same institution in 1894.<ref name="NobPriz">{{cite web |title=Ernest Rutherford Biographical |url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1908/rutherford/biographical/ |website=The Nobel Prize |publisher=Nobel Prize Outreach AB |access-date=13 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230603075847/https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1908/rutherford/biographical/ |archive-date=3 June 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Thereafter, he invented a new form of radio receiver, and in 1895 Rutherford was awarded an ] from the ],<ref>1851 Royal Commission Archives</ref> to travel to England for postgraduate study at the ], ].<ref name="Venn">{{acad|id=RTRT895E|name=Rutherford, Ernest}}</ref> In 1897, he was awarded a BA Research Degree and the Coutts-Trotter Studentship from ].<ref name=" |

Thereafter, he invented a new form of radio receiver, and in 1895 Rutherford was awarded an ] from the ],<ref>1851 Royal Commission Archives</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Papers Past {{!}} Newspapers {{!}} Ashburton Guardian {{!}} 13 July 1895 {{!}} European and Other Foreign Items |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AG18950713.2.9 |access-date=8 August 2023 |website=paperspast.natlib.govt.nz |archive-date=8 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230808013431/https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AG18950713.2.9 |url-status=live }}</ref> to travel to England for postgraduate study at the ], ].<ref name="Venn">{{acad|id=RTRT895E|name=Rutherford, Ernest}}</ref> In 1897, he was awarded a BA Research Degree and the Coutts-Trotter Studentship from ].<ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography"/> | ||

| == Scientific career == | == Scientific career == | ||

| ] | |||

| === Cambridge years === | |||

| At Cambridge, he was among the first 'aliens' (those without a Cambridge degree) allowed to do research at the university. Coupled with his mentorship under ],<ref name="aps" /> this distinction aroused jealousies from the more conservative members of the Cavendish fraternity. | |||

| When Rutherford began his studies at Cambridge, he was among the first 'aliens' (those without a Cambridge degree) allowed to do research at the university, and was additionally honoured to study under ].<ref name="aps" /> | |||

| With Thomson's encouragement, he detected radio waves at {{convert|0.5|mi|m}}, and briefly held the world record for the distance over which electromagnetic waves could be detected, though when he presented his results at the ] meeting in 1896, he discovered he had been outdone by ], whose radio waves had sent a message across nearly {{convert|10|mi|km}}.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Holmes |first1=Jonathan |title=Marconi's first radio broadcast made 125 years ago |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-somerset-61327062 |access-date=16 June 2023 |work=BBC News |date=13 May 2022}}</ref> | |||

| With Thomson's encouragement, Rutherford detected radio waves at {{convert|0.5|mi|m}}, and briefly held the world record for the distance over which electromagnetic waves could be detected, although when he presented his results at the ] meeting in 1896, he discovered he had been outdone by ], whose radio waves had sent a message across nearly {{convert|10|mi|km}}.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Holmes |first1=Jonathan |title=Marconi's first radio broadcast made 125 years ago |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-somerset-61327062 |access-date=16 June 2023 |work=BBC News |date=13 May 2022 |archive-date=5 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230605224315/https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-somerset-61327062 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Again under Thomson's leadership, Rutherford had worked on the conductive effects of X-rays on gases, which led to the discovery of the ], first presented by Thomson in 1897. Hearing of ]'s experience with ], Rutherford started to explore its ], discovering two types that differed from X-rays in their penetrating power. Continuing his research in Canada, he coined the terms ] and ]<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Trenn|first=Thaddeus J.|date=1976|title=Rutherford on the Alpha-Beta-Gamma Classification of Radioactive Rays|journal=Isis|volume=67|issue=1|pages=61–75|jstor=231134|doi=10.1086/351545|s2cid=145281124}}</ref> in 1899 to describe the two distinct types of ]. | |||

| === |

=== Work with radioactivity === | ||

| Again under Thomson's leadership, Rutherford worked on the conductive effects of X-rays on gases, which led to the discovery of the ], the results first presented by Thomson in 1897.<ref name=Hindu/><ref>{{cite book |last1=Buchwald |first1=Jed Z. |last2=Warwick |first2=Andrew |title=Histories of the electron: the birth of microphysics |date=30 January 2004 |publisher=MIT Press |location=Cambridge, Mass. |isbn=0262524244 |pages=21–30 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1yqqhlIdCOoC&pg=PA21 |access-date=27 June 2023 |archive-date=29 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230829163251/https://books.google.com/books?id=1yqqhlIdCOoC&pg=PA21 |url-status=live }}</ref> Hearing of ]'s experience with ], Rutherford started to explore its ], discovering two types that differed from X-rays in their penetrating power. Continuing his research in Canada, in 1899 he coined the terms "]" and "]" to describe these two distinct types of ].<ref name=abg>{{Cite journal|last=Trenn|first=Thaddeus J.|date=1976|title=Rutherford on the Alpha-Beta-Gamma Classification of Radioactive Rays|journal=Isis|volume=67|issue=1|pages=61–75|jstor=231134|doi=10.1086/351545|s2cid=145281124}}</ref> | |||

| In 1898, Rutherford was accepted to the ] position at ] in Montreal, Canada, under Thomson's recommendation.<ref>{{cite book| first=Robin| last=McKown| authorlink=Robin McKown|title=Giant of the Atom, Ernest Rutherford| url=https://archive.org/details/giantofatomernes00mcko|url-access=registration|year=1962|publisher=Julian Messner Inc, New York|page=}}</ref> In 1901, he earned a ] from the University of New Zealand.<ref name="Venn" /> | |||

| From 1900 to 1903, he was joined at McGill by the young chemist ] (], 1921) for whom he set the problem of identifying the ] emitted by the radioactive element ], a substance which was itself radioactive and would coat other substances. Once he had eliminated all the normal chemical reactions, Soddy suggested that it must be one of the inert gases, which they named ]. This substance was later found to be ], an isotope of radon.<ref>{{Cite arXiv|last=Kragh|first=Helge|date=5 February 2012|title=Rutherford, Radioactivity, and the Atomic Nucleus|eprint=1202.0954|class=physics.hist-ph}}</ref><ref name=" |

In 1898, Rutherford was accepted to the ] position at ] in Montreal, Canada, on Thomson's recommendation.<ref>{{cite book| first=Robin| last=McKown| authorlink=Robin McKown|title=Giant of the Atom, Ernest Rutherford| url=https://archive.org/details/giantofatomernes00mcko|url-access=registration|year=1962|publisher=Julian Messner Inc, New York|page=}}</ref> From 1900 to 1903, he was joined at McGill by the young chemist ] (], 1921) for whom he set the problem of identifying the ] emitted by the radioactive element ], a substance which was itself radioactive and would coat other substances. Once he had eliminated all the normal chemical reactions, Soddy suggested that it must be one of the inert gases, which they named ]. This substance was later found to be ], an isotope of radon.<ref name="Kragh">{{Cite arXiv|last=Kragh|first=Helge|date=5 February 2012|title=Rutherford, Radioactivity, and the Atomic Nucleus|eprint=1202.0954|class=physics.hist-ph}}</ref><ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography"/> They also found another substance they called Thorium X, later identified as ], and continued to find traces of helium. They also worked with samples of "Uranium X" (]), from ], and ], from ]. Rutherford further investigated thoron in conjunction with ] and found that a sample of radioactive material of any size invariably took the same amount of time for half the sample to decay (in this case, 11{{frac|1|2}} minutes), a phenomenon for which he coined the term "]".<ref name="Kragh"/> Rutherford and Soddy published their paper "Law of Radioactive Change" to account for all their experiments. Until then, atoms were assumed to be the indestructible basis of all matter; and although Curie had suggested that radioactivity was an atomic phenomenon, the idea of the atoms of radioactive substances breaking up was a radically new idea. Rutherford and Soddy demonstrated that radioactivity involved the spontaneous disintegration of atoms into other, as yet, unidentified matter.<ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography"/> | ||

| In 1903, Rutherford considered a type of radiation, discovered (but not named) by French chemist ] in 1900, as an emission from ], and realised that this observation must represent something different from his own alpha and beta rays, due to its very much greater penetrating power. Rutherford therefore gave this third type of radiation the name of ].<ref name=abg/> All three of Rutherford's terms are in standard use today – other types of ] have since been discovered, but Rutherford's three types are among the most common. In 1904, Rutherford suggested that radioactivity provides a source of energy sufficient to explain the existence of the Sun for the many millions of years required for the slow biological evolution on Earth proposed by biologists such as ]. The physicist ] earlier for a much younger Earth, based on the insufficiency of known energy sources, but Rutherford pointed out, at a lecture attended by Kelvin, that radioactivity could solve this problem.<ref name="England et al 2007">{{cite journal |author1=England, P. |author2=Molnar, P. |author3=Righter, F. | title=John Perry's neglected critique of Kelvin's age for the Earth: A missed opportunity in geodynamics |journal=GSA Today |date=January 2007 |volume=17 |issue=1 |pages=4–9 |doi=10.1130/GSAT01701A.1 |bibcode=2007GSAT...17R...4E |doi-access= free}}</ref> Later that year, he was elected as a member to the ],<ref>{{Cite web|title=APS Member History|url=https://search.amphilsoc.org/memhist/search?creator=&title=&subject=&subdiv=&mem=&year=1904&year-max=&dead=&keyword=&smode=advanced|access-date=28 June 2021|website=search.amphilsoc.org|archive-date=28 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210628190035/https://search.amphilsoc.org/memhist/search?creator=&title=&subject=&subdiv=&mem=&year=1904&year-max=&dead=&keyword=&smode=advanced|url-status=live}}</ref> and in 1907 he returned to Britain to take the ] of physics at the ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Ernest Rutherford: Heritage Heroes at The University of Manchester |url=https://www.manchester.ac.uk/discover/history-heritage/history/heroes/ernest-rutherford/ |website=The University of Manchester |access-date=27 June 2023 |language=en |archive-date=27 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230627004723/https://www.manchester.ac.uk/discover/history-heritage/history/heroes/ernest-rutherford/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In conjunction with ], Rutherford further investigated thoron and found that a sample of radioactive material of any size invariably took the same amount of time for half the sample to decay (in this case, 11{{frac|1|2}} minutes), a phenomenon for which he coined the term "]."<ref>{{Cite arXiv|last=Kragh|first=Helge|date=5 February 2012|title=Rutherford, Radioactivity, and the Atomic Nucleus|eprint=1202.0954|class=physics.hist-ph}}</ref><ref name="NobPriz"></ref> | |||

| In Manchester, Rutherford continued his work with alpha radiation. In conjunction with ], he developed zinc sulfide ] screens and ]s to count alpha particles. By dividing the total charge accumulated on the screen by the number counted, Rutherford determined that the charge on the alpha particle was two.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=1908-08-27 |title=The charge and nature of the α-particle |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character |language=en |volume=81 |issue=546 |pages=162–173 |doi=10.1098/rspa.1908.0066 |bibcode=1908RSPSA..81..162R |issn=0950-1207 |last1=Rutherford |first1=E. |last2=Geiger |first2=Hans |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=PaisInwardBound>{{Cite book |last=Pais |first=Abraham |title=Inward bound: of matter and forces in the physical world |date=2002 |publisher=Clarendon Press |isbn=978-0-19-851997-3 |edition=Reprint |location=Oxford}}</ref>{{rp|61}} In late 1907, Ernest Rutherford and ] allowed alphas to penetrate a very thin window into an evacuated tube. As they ], the spectrum obtained from it changed, as the alphas accumulated in the tube. Eventually, the clear spectrum of helium gas appeared, proving that alphas were at least ionised helium atoms, and probably helium nuclei.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=E. |last2=Royds |first2=T. |title=XXI. The nature of the α particle from radioactive substances |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |date=February 1909 |volume=17 |issue=98 |pages=281–286 |doi=10.1080/14786440208636599 |url=https://zenodo.org/record/1430648 |access-date=11 August 2023 |archive-date=7 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210507040356/https://zenodo.org/record/1430648 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] in 1905]] | |||

| In 1910 Rutherford, with Geiger and mathematician ] published<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=E. |last2=Geiger |first2=H. |last3=Bateman |first3=H. |title=LXXVI. The probability variations in the distribution of α particles |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |date=October 1910 |volume=20 |issue=118 |pages=698–707 |doi=10.1080/14786441008636955 |url=https://zenodo.org/record/1430880 |access-date=11 August 2023 |archive-date=29 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230829170123/https://zenodo.org/record/1430880 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1903, Rutherford and Soddy published their "Law of Radioactive Change", to account for all their experiments. Until then, atoms were assumed to be the indestructible basis of all matter and although Curie had suggested that radioactivity was an atomic phenomenon, the idea of the atoms of radioactive substances breaking up was a radically new idea. Rutherford and Soddy demonstrated that radioactivity involved the spontaneous disintegration of atoms into other, as yet, unidentified matter. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1908 was awarded to Ernest Rutherford "for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances".<ref>{{cite web |title=The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1908 |url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1908/summary/ |website=The Nobel Prize |publisher=The Nobel Foundation |access-date=2 April 2020}}</ref> | |||

| their classic paper<ref>Bulmer, M. G. (1979). Principles of Statistics. United Kingdom: Dover Publications.</ref>{{rp|94}} describing the first analysis of the distribution in time of radioactive emission, a distribution now called the ]. | |||

| Ernest Rutherford was awarded the ] "for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances".<ref>{{cite web |title=The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1908 |url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1908/summary/ |website=The Nobel Prize |publisher=The Nobel Foundation |access-date=2 April 2020 |archive-date=8 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180708045209/https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1908/index.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography" /> | |||

| In 1903, Rutherford considered a type of radiation discovered (but not named) by French chemist ] in 1900, as an emission from ], and realised that this observation must represent something different from his own alpha and beta rays, due to its very much greater penetrating power. Rutherford therefore gave this third type of radiation the name of ]. All three of Rutherford's terms are in standard use today – other types of ] have since been discovered, but Rutherford's three types are among the most common. | |||

| === Model of the atom === | |||

| In 1904, Rutherford suggested that radioactivity provides a source of energy sufficient to explain the existence of the Sun for the many millions of years required for the slow biological evolution on Earth proposed by biologists such as ]. The physicist Lord Kelvin had argued earlier for a much younger Earth (see also ]) based on the insufficiency of known energy sources, but Rutherford pointed out at a lecture attended by Kelvin that radioactivity could solve this problem.<ref name="England et al 2007">{{cite journal |author1=England, P. |author2=Molnar, P. |author3=Righter, F. | title=John Perry's neglected critique of Kelvin's age for the Earth: A missed opportunity in geodynamics |journal=GSA Today |date=January 2007 |volume=17 |issue=1 |pages=4–9 |doi=10.1130/GSAT01701A.1 |bibcode=2007GSAT...17R...4E |doi-access= free}}</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Rutherford–Bohr model| Rutherford scattering}} | |||

| In 1904, he was elected as a member to the ],<ref>{{Cite web|title=APS Member History|url=https://search.amphilsoc.org/memhist/search?creator=&title=&subject=&subdiv=&mem=&year=1904&year-max=&dead=&keyword=&smode=advanced|access-date=28 June 2021|website=search.amphilsoc.org}}</ref> and in 1907, he returned to Britain to take the ] of physics at the ]. | |||

| === Manchester years === | |||

| In Manchester, Rutherford continued his work with alpha radiation. In conjunction with ], he developed zinc sulfide ] and ]s to count alphas. By dividing the total charge they produced by the number counted, Rutherford decided that the charge on the alpha was two.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=E. |last2=Geiger |first2=H. |last3=Bateman |first3=H. |title=LXXVI. The probability variations in the distribution of α particles |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |date=October 1910 |volume=20 |issue=118 |pages=698–707 |doi=10.1080/14786441008636955}}</ref> In late 1907, Ernest Rutherford and ] allowed alphas to penetrate a very thin window into an evacuated tube. As they ], the spectrum obtained from it changed, as the alphas accumulated in the tube. Eventually, the clear spectrum of helium gas appeared, proving that alphas were at least ionised helium atoms, and probably helium nuclei.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=E. |last2=Royds |first2=T. |title=XXI. The nature of the α particle from radioactive substances |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |date=February 1909 |volume=17 |issue=98 |pages=281–286 |doi=10.1080/14786440208636599}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Model of the atom ==== | |||

| {{See also|Rutherford–Bohr model}} | |||

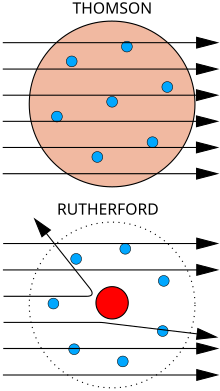

| ]s passing through the ] of the atom undisturbed.<br /> | ]s passing through the ] of the atom undisturbed.<br /> | ||

| ''Bottom:'' Observed results: a small portion of the particles were deflected, indicating ]. Diagram is not to scale; in reality the nucleus is vastly smaller than the electron shell.]] | ''Bottom:'' Observed results: a small portion of the particles were deflected, indicating ]. Diagram is not to scale; in reality the nucleus is vastly smaller than the electron shell.]] | ||

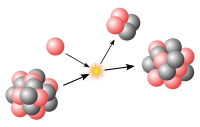

| Rutherford continued to make ground breaking discoveries long after receiving the Nobel prize in 1908. Along with ] and ] in 1909, he carried out the ], which demonstrated the nuclear nature of atoms by deflecting ] passing through a thin gold foil. Rutherford was inspired to ask Geiger and Marsden in this experiment to look for alpha particles with very high deflection angles, of a type not expected from any theory of matter at that time. Such deflections, though rare, were found, and proved to be a smooth but high-order function of the deflection angle. It was Rutherford's interpretation of this data that led him to formulate the ] of the atom in 1911{{snd}}that a very small ]<ref name=charge /> ], containing much of the atom's mass, was ]ed by low-mass ]s. | |||

| Rutherford continued to make ground-breaking discoveries long after receiving the Nobel prize in 1908.<ref name=PaisInwardBound/>{{rp|63|q=...Rutherford, who rose to his greatest heights after 1908, most notably because of his discovery of the atomic nucleus}} Under his direction in 1909, ] and ] performed the ], which demonstrated the nuclear nature of atoms by measuring the deflection of ] passing through a thin gold foil.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Pestka |first1=Jessica |title=About Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment |url=https://sciencing.com/rutherfords-gold-foil-experiment-4569065.html |website=Sciencing |access-date=27 June 2023 |language=en |date=25 April 2017 |archive-date=27 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230627004502/https://sciencing.com/rutherfords-gold-foil-experiment-4569065.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Rutherford was inspired to ask Geiger and Marsden in this experiment to look for alpha particles with very high deflection angles, which was not expected according to any theory of matter at that time.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dragovich |first1=Branko |title=Ernest Rutherford and the Discovery of the Atomic Nucleus |publisher=Institute of Physics |location=Belgrade |url=http://bsw2011.seenet-mtp.info/pub/bss2011-DragovichB-abs.pdf |access-date=27 June 2023 |archive-date=27 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230627004502/http://bsw2011.seenet-mtp.info/pub/bss2011-DragovichB-abs.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Davidson |first1=Michael W. |title=Pioneers in Optics: Johann Wilhelm Ritter and Ernest Rutherford |journal=Microscopy Today |date=March 2014 |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=48–51 |doi=10.1017/S1551929514000029 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/E8B7456A024C6ED07D4E891F540C8EE2/S1551929514000029a.pdf/pioneers-in-optics-johann-wilhelm-ritter-and-ernest-rutherford.pdf |access-date=27 June 2023 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |s2cid=135584871 |archive-date=3 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230103220843/https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/E8B7456A024C6ED07D4E891F540C8EE2/S1551929514000029a.pdf/pioneers-in-optics-johann-wilhelm-ritter-and-ernest-rutherford.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Such deflection angles, although rare, were found. Reflecting on these results in one of his last lectures, Rutherford was quoted as saying: "It was quite the most incredible event that has ever happened to me in my life. It was almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you."<ref>''The Development of the Theory of Atomic Structure'' (Rutherford 1936). Reprinted in </ref> It was Rutherford's interpretation of this data that led him to propose the ], a very small, ] region containing much of the atom's mass.<ref name=charge>{{Cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=E. |year=1911 |title=The scattering of α and β particles by matter and the structure of the atom |url=http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/rutherford/rutherford688.html |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |series=Series 6 |volume=21 |issue=125 |pages=669–688 |doi=10.1080/14786440508637080 |access-date=6 October 2012 |archive-date=7 June 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120607013629/http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/rutherford/rutherford688.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1912, Rutherford was joined by ] (who postulated that electrons moved in specific orbits). Bohr adapted Rutherford's nuclear structure to be consistent with ]'s ], and the resulting ] is considered valid to this day.<ref name="NobPriz"></ref> | |||

| In 1912, Rutherford was joined by ] (who postulated that electrons moved in specific orbits about the compact nucleus). Bohr adapted Rutherford's nuclear structure to be consistent with ]'s quantum hypothesis. The resulting ] was the basis for ] atomic physics of Heisenberg which remains valid today.<ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography"/> | |||

| ==== Discovery of the proton ==== | |||

| Together with ], Rutherford developed the ] in 1913. Rutherford and Moseley's experiments used ] to bombard various elements with a stream of electrons and observed that each element responded in a consistent and distinct manner. Their research was the first to assert that each element could be defined by the properties of its inner structures – an observation which later led to the discovery of the ].<ref name="NobPriz"></ref> This research led Rutherford to theorize that the hydrogen atom (at the time the least massive entity known to bear a positive charge) was a sort of "positive electron" – a component of every atomic element.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=Ernest |title=The structure of the atom |journal=Philosophical Magazine |date=1914 |volume=27 |pages=488–498 |url=http://www.ub.edu/hcub/hfq/sites/default/files/ruth1914%285%29.pdf |access-date=13 June 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Whittaker |first1=Edmund |title=A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity |date=1989 |volume=2 |publisher=Courier Dover Publications |isbn=0-486-26126-3 |page=87}}</ref> | |||

| === Piezoelectricity === | |||

| During World War I, Rutherford worked on a top secret project to solve the practical problems of submarine detection by ].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/manchester-scientist-ernest-rutherford-revealed-8078891 |title=Manchester scientist Ernest Rutherford revealed as top secret mastermind behind sonar technology |author=Alan Selby |date=9 November 2014 |work=Manchester Evening News |access-date=13 November 2014}}</ref> In 1916, he was awarded the ]. | |||

| During World War I, Rutherford worked on a top-secret project to solve the practical problems of submarine detection. Both Rutherford and ] suggested the use of ], and Rutherford successfully developed a device which measured its output. The use of piezoelectricity then became essential to the development of ] as it is known today. The claim that Rutherford developed ], however, is a misconception, as subaquatic detection technologies utilise Langevin's ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Katzir |first1=Shaul |title=Who knew piezoelectricity? Rutherford and Langevin on submarine detection and the invention of sonar |journal=Notes and Records of the Royal Society |date=20 June 2012 |volume=66 |issue=2 |pages=141–157 |doi=10.1098/rsnr.2011.0049 |s2cid=1240938 |url=https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/epdf/10.1098/rsnr.2011.0049 |access-date=2 July 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Duck |first1=Francis |title=Paul Langevin, U-boats, and ultrasonics |journal=Physics Today |date=1 November 2022 |volume=75 |issue=11 |pages=42–48 |doi=10.1063/PT.3.5122 |bibcode=2022PhT....75k..42D |s2cid=253280842 |url=https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/75/11/42/2848556/Paul-Langevin-U-boats-and-ultrasonicsCreated-in |access-date=2 July 2023 |doi-access=free |archive-date=2 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702184756/https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/75/11/42/2848556/Paul-Langevin-U-boats-and-ultrasonicsCreated-in |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Discovery of the proton === | |||

| Shortly before the end of his time at Manchester, Rutherford expanded upon his research of the "positive electron" with a series of experiments beginning in 1919. He found that nitrogen and other light elements ejected a proton, which he called a "hydrogen atom", when hit with α (alpha) particles.<ref name="NobPriz"></ref> In particular, he showed that particles ejected by alpha particles colliding with hydrogen have unit charge and 1/4 the momentum of alpha particles.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=Ernest |title=LII. Collision of α particles with light atoms II. Velocity of the hydrogen atom |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |date=8 April 2009 |volume=37 |issue=222 |pages=562–571 |doi=10.1080/14786440608635917 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14786440608635917?journalCode=tphm17 |access-date=13 June 2023 |series=6}}</ref> | |||

| Together with ], Rutherford developed the ] in 1913. Rutherford and Moseley's experiments used ] to bombard various elements with streams of electrons and observed that each element responded in a consistent and distinct manner. Their research was the first to assert that each element could be defined by the properties of its inner structures – an observation that later led to the discovery of the ].<ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography"/> This research led Rutherford to theorize that the hydrogen atom (at the time the least massive entity known to bear a positive charge) was a sort of "positive electron" – a component of every atomic element.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=Ernest |title=The structure of the atom |journal=Philosophical Magazine |date=1914 |volume=27 |pages=488–498 |url=http://www.ub.edu/hcub/hfq/sites/default/files/ruth1914%285%29.pdf |access-date=13 June 2023 |archive-date=13 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230613022543/http://www.ub.edu/hcub/hfq/sites/default/files/ruth1914(5).pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Whittaker |first1=Edmund |title=A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity |date=1989 |volume=2 |publisher=Courier Dover Publications |isbn=0-486-26126-3 |page=87}}</ref> | |||

| It was not until 1919 that Rutherford expanded upon his theory of the "positive electron" with a series of experiments beginning shortly before the end of his time at Manchester. He found that nitrogen, and other light elements, ejected a proton, which he called a "hydrogen atom", when hit with α (alpha) particles.<ref name="Nobel Rutherford Biography"/> In particular, he showed that particles ejected by alpha particles colliding with hydrogen have unit charge and 1/4 the momentum of alpha particles.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=Ernest |title=LII. Collision of α particles with light atoms II. Velocity of the hydrogen atom |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |date=8 April 2009 |volume=37 |issue=222 |pages=562–571 |doi=10.1080/14786440608635917 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14786440608635917?journalCode=tphm17 |access-date=13 June 2023 |series=6 |archive-date=13 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230613022542/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14786440608635917?journalCode=tphm17 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Back to Cambridge === | |||

| In 1919, he returned to the Cavendish succeeding J. J. Thomson as the Cavendish professor and Director. Under him, Nobel Prizes were awarded to ] for discovering the neutron (in 1932), ] and ] for an experiment which was to be known as ''splitting the atom'' using a ], and ] for demonstrating the existence of the ]. | |||

| Rutherford returned to the Cavendish Laboratory in 1919, succeeding J. J. Thomson as the Cavendish professor and the laboratory's director, posts that he held until his death in 1937.<ref name=cam>{{cite web |url=http://www.phy.cam.ac.uk/history/cavprof.php |title=The Cavendish Professorship of Physics |publisher=University of Cambridge |accessdate=30 November 2013 |archive-date=3 July 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130703172354/http://www.phy.cam.ac.uk/history/cavprof.php |url-status=dead }}</ref> During his tenure, Nobel prizes were awarded to ] for discovering the neutron (in 1932), ] and ] for an experiment that was to be known as ''splitting the atom'' using a ], and ] for demonstrating the existence of the ]. | |||

| ==== Development of proton and neutron theory ==== | |||

| In 1919–1920, Rutherford continued his research on the "hydrogen atom" to confirm that alpha particles breakdown nitrogen nuclei and affirm the nature of the products.<ref>{{cite web |title=Atop the Physics Wave: Rutherford back in Cambridge, 1919–1937 |url=http://history.aip.org/history/exhibits/rutherford/sections/atop-physics-wave.html |website=Rutherford's Nuclear World: The Story of the Discovery of the Nucleus |publisher=American Institute of Physics |access-date=25 June 2018}}</ref> This result showed Rutherford that hydrogen nuclei were a part of nitrogen nuclei (and by inference, probably other nuclei as well). Such a construction had been suspected for many years on the basis of atomic weights which were whole numbers of that of hydrogen; see ]. Hydrogen was known to be the lightest element, and its nuclei presumably the lightest nuclei. Now, because of all these considerations, Rutherford decided that a hydrogen nucleus was possibly a fundamental building block of all nuclei, and also possibly a new fundamental particle as well, since nothing was known from the nucleus that was lighter. Thus, confirming and extending the work of ] who in 1898 discovered the proton in streams of ],<ref>{{Cite journal |doi = 10.1002/andp.18943180404|title = Über positive Elektronen und die Existenz hoher Atomgewichte|journal = Annalen der Physik|volume = 318|issue = 4|pages = 669–677|year = 1904|last1 = Wien|first1 = W.|bibcode = 1904AnP...318..669W|url = https://zenodo.org/record/2190505}}</ref> Rutherford postulated the hydrogen nucleus to be a new particle in 1920, which he dubbed the '']''. | |||

| === Development of proton and neutron theory === | |||

| In 1921, while working with Niels Bohr, Rutherford theorized about the existence of ]s, (which he had christened in his 1920 ]), which could somehow compensate for the repelling effect of the positive charges of ]s by causing an attractive ] and thus keep the nuclei from flying apart from the repulsion between protons. The only alternative to neutrons was the existence of "nuclear electrons" which would counteract some of the proton charges in the nucleus, since by then it was known that nuclei had about twice the mass that could be accounted for if they were simply assembled from hydrogen nuclei (protons). But how these nuclear electrons could be trapped in the nucleus, was a mystery. Rutherford is widely quoted as saying, regarding the results of these experiments: "It was quite the most incredible event that has ever happened to me in my life. It was almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you."<ref>E. N. da C. Andrade, ''Rutherford and the Nature of the Atom'' (1964), cited in {{cite book|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191826719.001.0001/q-oro-ed4-00009051 |title=Oxford Essential Quotations |edition=4th |year=2016 |chapter=Ernest Rutherford 1871–1937, New Zealand physicist |isbn=9780191826719 |editor-first=Susan |editor-last=Ratcliffe}}</ref> | |||

| In 1919–1920, Rutherford continued his research on the "hydrogen atom" to confirm that alpha particles break down nitrogen nuclei and to affirm the nature of the products. This result showed Rutherford that hydrogen nuclei were a part of nitrogen nuclei (and by inference, probably other nuclei as well). Such a construction had been suspected for many years, on the basis of atomic weights that were integral multiples of that of hydrogen; see ]. Hydrogen was known to be the lightest element, and its nuclei presumably the lightest nuclei. Now, because of all these considerations, Rutherford decided that a hydrogen nucleus was possibly a fundamental building block of all nuclei, and also possibly a new fundamental particle as well, since nothing was known to be lighter than that nucleus. Thus, confirming and extending the work of ], who in 1898 discovered the proton in streams of ],<ref>{{Cite journal|doi = 10.1002/andp.18943180404|title = Über positive Elektronen und die Existenz hoher Atomgewichte|journal = Annalen der Physik|volume = 318|issue = 4|pages = 669–677|year = 1904|last1 = Wien|first1 = W.|bibcode = 1904AnP...318..669W|url = https://zenodo.org/record/2190505|access-date = 5 September 2020|archive-date = 13 July 2020|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200713133516/https://zenodo.org/record/2190505|url-status = live}}</ref> in 1920 Rutherford postulated the hydrogen nucleus to be a new particle, which he dubbed the '']''.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Orme Masson |date=1921 |title=The Constitution of Atoms |journal=The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science |volume=41 |issue=242 |pages=281–285 |doi=10.1080/14786442108636219 |url=https://archive.org/details/londonedinburg6411921lond/page/280/mode/2up }}<br/>Footnote by Ernest Rutherford: 'At the time of writing this paper in Australia, Professor Orme Masson was not aware that the name "proton" had already been suggested as a suitable name for the unit of mass nearly 1, in terms of oxygen 16, that appears to enter into the nuclear structure of atoms. The question of a suitable name for this unit was discussed at an informal meeting of a number of members of Section A of the British Association at Cardiff this year. The name "baron" suggested by Professor Masson was mentioned, but was considered unsuitable on account of the existing variety of meanings. Finally the name "proton" met with general approval, particularly as it suggests the original term "protyle " given by Prout in his well-known hypothesis that all atoms are built up of hydrogen. The need of a special name for the nuclear unit of mass 1 was drawn attention to by Sir Oliver Lodge at the Sectional meeting, and the writer then suggested the name "proton."'</ref> | |||

| In 1921, while working with Niels Bohr, Rutherford theorized about the existence of ]s, (which he had christened in his 1920 ]), which could somehow compensate for the repelling effect of the positive charges of ]s by causing an attractive ] and thus keep the nuclei from flying apart, due to the repulsion between protons. The only alternative to neutrons was the existence of "nuclear electrons", which would counteract some of the proton charges in the nucleus, since by then it was known that nuclei had about twice the mass that could be accounted for if they were simply assembled from hydrogen nuclei (protons). But how these nuclear electrons could be trapped in the nucleus, was a mystery. | |||

| Rutherford's theory of ]s was proved in 1932 by his associate ], who recognized neutrons immediately when they were produced by other scientists and later himself, in bombarding beryllium with alpha particles. In 1935, Chadwick was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery.<ref>{{cite web |title=James Chadwick - Facts |url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1935/chadwick/facts/ |website=The Nobel Prize |publisher=Nobel Prize Outreach AB |access-date=16 June 2023}}</ref> | |||

| In 1932, Rutherford's theory of ]s was proved by his associate ], who recognised neutrons immediately when they were produced by other scientists and later himself, in bombarding beryllium with alpha particles. In 1935, Chadwick was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery.<ref>{{cite web |title=James Chadwick – Facts |url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1935/chadwick/facts/ |website=The Nobel Prize |publisher=Nobel Prize Outreach AB |access-date=16 June 2023 |archive-date=4 October 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191004015954/https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1935/chadwick/facts/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Re-evaluation of nuclear transmutation credit === | |||

| A long-standing myth existed, at least as early as 1948,<ref>{{cite journal |title=Nobel Prize for Physics : Prof. P. M. S. Blackett, F.R.S |journal=Nature |volume=162 |issue=4126 |year=1948 |pages=841 |doi=10.1038/162841b0|bibcode=1948Natur.162R.841. |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Exploring the atom |url=https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Resources/adventures_atom.htm |work=The Manhattan Project – Adventures Inside the Atom|publisher=U.S. Department of Energy – Office of History and Heritage Resources |access-date=19 June 2019}}</ref> running at least to 2017, that Rutherford was the first scientist to observe and report an artificial ] of a stable element into another element: nitrogen into oxygen. It was thought by many people to be one of Rutherford's greatest accomplishments.<ref>{{cite web |last=Dacey |first=James |title=What was Rutherford's greatest discovery? |url=https://physicsworld.com/a/what-was-rutherfords-greatest/ |publisher=Physics World |date=1 September 2011 |access-date= 18 June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Allibone |first=Thomas Edward |title=Rutherford Memorial Lecture, 1963 The industrial development of nuclear power |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences |volume=282 |issue=1391 |year=1964 |pages=447–463 |doi=10.1098/rspa.1964.0245|bibcode=1964RSPSA.282..447A |s2cid=97303563 }}</ref> The New Zealand government even issued a commemorative stamp in the belief that the nitrogen-to-oxygen discovery belonged to Rutherford.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Campbell |first=John |title=Inside Story: The genius of Rutherford revisited |url=https://cerncourier.com/inside-story-the-genius-of-rutherford-revisited/ |journal=CERN Courier |year=2009 |volume=49 |issue=2 |pages=46–48}}</ref> Beginning in 2017, many scientific institutions corrected their versions of this history to indicate that the discovery credit for the reaction belongs to ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Exploring the atom |url=https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1890s-1939/exploring.htm |work=The Manhattan Project – an interactive history |publisher=U.S. Department of Energy – Office of History and Heritage Resources |access-date=18 June 2019}}</ref> Rutherford did detect the ejected proton in 1919 and interpreted it as evidence for disintegration of the nitrogen nucleus (to lighter nuclei). In 1925, Blackett showed that the actual product is oxygen and identified the true reaction as <sup>14</sup>N + α → <sup>17</sup>O + p. Rutherford therefore recognized "that the nucleus may increase rather than diminish in mass as the result of collisions in which the proton is expelled".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=Sir Ernest |title=Studies of Atomic Nuclei |journal=Science |volume=62 |issue=1601 |url=https://archive.org/details/RoyalInstitutionLibraryOfScience-PhysicalScienceVol9 |publisher=The Royal Institution Library of Sciences |access-date=29 June 2019 |location=Physical Sciences Volume 9 |pages=73–76 |date=27 March 1925|pmid=17748045 |doi=10.1126/science.62.1601.209 |bibcode=1925Sci....62..209R }}</ref> | |||

| === Induced nuclear reaction and probing the nucleus === | |||

| In Rutherford's four-part article on the "Collision of α-particles with light atoms" he reported two additional fundamental and far reaching discoveries.<ref name=PaisInwardBound/>{{rp|237}} First, he showed that at high angles the scattering of alpha particles from hydrogen differed from the theoretical results he himself published in 1911. These were the first results to probe the interactions that hold a nucleus together. Second, he showed that α-particles colliding with nitrogen nuclei would react rather than simply bounce off. One product of the reaction was the proton; the other product was shown by ], Rutherford's colleague and former student, to be oxygen: | |||

| :<sup>14</sup>N + α → <sup>17</sup>O + p. | |||

| Rutherford therefore recognised "that the nucleus may increase rather than diminish in mass as the result of collisions in which the proton is expelled".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=Sir Ernest |title=Studies of Atomic Nuclei |url=https://archive.org/details/RoyalInstitutionLibraryOfScience-PhysicalScienceVol9 |date=27 March 1925 |journal=] |volume=62 |issue=1601 |pages=73–76 |publisher=The Royal Institution Library of Sciences |doi=10.1126/science.62.1601.209 |pmid=17748045 |bibcode=1925Sci....62..209R |access-date=2 October 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Blackett was awarded the Nobel prize in 1948 for his work in perfecting the high-speed cloud chamber apparatus used to make that discovery and many others.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Nobel Prize for Physics : Prof. P. M. S. Blackett, F.R.S |journal=Nature |volume=162 |issue=4126 |year=1948 |pages=841 |doi=10.1038/162841b0|bibcode=1948Natur.162R.841. |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| === Later years and honours === | === Later years and honours === | ||

| Rutherford received significant recognition in his home country of New Zealand. In 1901, he earned a ] from the University of New Zealand.<ref name="Venn" /> In 1916, he was awarded the ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Recipients |url=https://www.royalsociety.org.nz/what-we-do/medals-and-awards/hector-medal/recipients-3/ |publisher=] |access-date=16 February 2021 |archive-date=30 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170430164858/https://www.royalsociety.org.nz/what-we-do/medals-and-awards/hector-medal/recipients-3/ |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1925, Rutherford called for the ] to support education and research, which led to the formation of the ] in the following year.<ref>{{cite web |first=Emma |last=Brewerton |date=15 December 2014 |title=Ernest Rutherford |publisher=Ministry for Culture and Heritage |url=http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/people/ernest-rutherford |access-date=29 December 2010 |archive-date=1 December 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121201203746/http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/people/ernest-rutherford |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1933, Rutherford was one of the two inaugural recipients of the ], which was established by the ] as an award for outstanding scientific research.<ref>{{cite web |title=Background of the Medal |url=http://www.royalsociety.org.nz/programmes/awards/sidey-medal/background/ |publisher=] |access-date=7 August 2015 |archive-date=19 September 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160919031437/http://www.royalsociety.org.nz/programmes/awards/sidey-medal/background/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Recipients |url=http://www.royalsociety.org.nz/programmes/awards/sidey-medal/recipients/ |publisher=] |access-date=7 August 2015 |archive-date=9 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170409021241/http://royalsociety.org.nz/programmes/awards/sidey-medal/recipients/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Throughout his life, Rutherford received a number of awards from the British Crown: he was ] in 1914, awarded an Order of Merit in 1925, and made a Baron in 1931, decorating his coat of arms with a ] and a ] warrior.<ref>{{cite web |title=Ernest Rutherford - Biography |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/ernest-rutherford |website=New Zealand History |access-date=23 June 2023}}</ref><ref>{{London Gazette |issue=12647 |date=27 February 1914 |page=269 |city=Edinburgh}}</ref> | |||

| Additionally, Rutherford received a number of awards from the British Crown. He was ] in 1914.<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=12647 |date=27 February 1914 |page=269 |city=Edinburgh}}</ref> He was appointed to the ] in the ].<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=14089 |date=2 January 1925 |page=4 |city=Edinburgh}}</ref> Between 1925 and 1930, he served as ], and later as president of the ] which helped almost 1,000 university refugees from Germany.<ref name="eb"/> In 1931 was raised to Baron of the United Kingdom under the title '''Baron Rutherford of Nelson''',<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=33683 |date=23 January 1931 |page=533}}</ref> decorating his coat of arms with a ] and a ] warrior.<ref>{{cite web |title=Ernest Rutherford – Biography |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/ernest-rutherford |website=New Zealand History |access-date=23 June 2023 |archive-date=23 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230623110402/https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/ernest-rutherford |url-status=live }}</ref> The title became extinct upon his unexpected death in 1937. | |||

| Since 1992 his portrait appears on the ]. | |||

| In 1925, Rutherford pushed calls to the ] to support education and research, which led to the formation of the ] in the following year.<ref>{{cite web |first=Emma |last=Brewerton |date=15 December 2014 |title=Ernest Rutherford |publisher=Ministry for Culture and Heritage |url=http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/people/ernest-rutherford}}</ref> Between 1925 and 1930, he served as ], and later as president of the ] which helped almost 1,000 university refugees from Germany.<ref name="eb" /> He was appointed to the ] in the ]<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=14089 |date=2 January 1925 |page=4 |city=Edinburgh}}</ref> and raised to the peerage as '''Baron Rutherford of Nelson''', New Zealand and of Cambridge in the County of Cambridge in 1931,<ref>{{London Gazette |issue=33683 |date=23 January 1931 |page=533}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1908 |url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1908/rutherford/biographical/ |access-date=16 April 2022 |website=NobelPrize.org |language=en-US}}</ref> a title that became extinct upon his unexpected death in 1937. In 1933, Rutherford was one of the two inaugural recipients of the ], set up by the ] as an award for outstanding scientific research.<ref>{{cite web |title=Background of the Medal |url=http://www.royalsociety.org.nz/programmes/awards/sidey-medal/background/ |publisher=] |access-date=7 August 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Recipients |url=http://www.royalsociety.org.nz/programmes/awards/sidey-medal/recipients/ |publisher=] |access-date=7 August 2015}}</ref> | |||

| == Personal life and death == | == Personal life and death == | ||

| Around 1888 Rutherford made his grandmother a wooden potato masher which is now in the collection of the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ernest Rutherford's potato masher |url=https://prints.royalsociety.org/products/ernest-rutherfords-potato-masher-rs-8469 |access-date=2023-08-10 |website=Royal Society Print Shop |archive-date=10 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230810231752/https://prints.royalsociety.org/products/ernest-rutherfords-potato-masher-rs-8469 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Royal Society Picture Library {{!}} Potato masher,Potato masher |url=https://pictures.royalsociety.org/image-rs-8469 |access-date=2023-08-10 |website=pictures.royalsociety.org |archive-date=10 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230810231608/https://pictures.royalsociety.org/image-rs-8469 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In 1900, Rutherford married Mary Georgina Newton (1876–1954),<ref>{{Cite web| last=Intergen| title=General| url=https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz/|access-date=2023-02-08|website=www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz}}</ref> to whom he had become engaged before leaving New Zealand, at ] in ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/christchurch-life/560019/Family-history-in-from-the-cold |title=Family history in from the cold |date=18 March 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| first=Fiona| last=Summerfield| url=http://anglicantaonga.org.nz/news/tikanga_pakeha/new_lease_of_life_for_historic_chch_church|title=Historic St Paul's Church in the Christchurch suburb of Papanui is being fully restored|website=Anglican Taonga|date=9 November 2012}}</ref> | |||

| They had one daughter, Eileen Mary (1901–1930), who married the physicist ]. | |||