| Revision as of 16:24, 25 April 2024 editNorfolkbigfish (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,904 edits Last remaining edits to remove what Borsoka considered copyvio or close paraphrasingTag: 2017 wikitext editor← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:42, 5 January 2025 edit undoNorfolkbigfish (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,904 edits →Popular crusading: fixing tagsTag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| (165 intermediate revisions by 26 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{about|the ideology and institutions associated with crusading|the expeditions themselves|Crusades}} | {{about|the ideology and institutions associated with crusading|the expeditions themselves|Crusades}} | ||

| {{other uses|Crusade (disambiguation)|Crusader (disambiguation)}} | {{other uses|Crusade (disambiguation)|Crusader (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=December 2024}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| [[File:The Church of the Holy Sepulchre-Jerusalem.JPG|thumb|upright=1.35|alt=photograph of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem| | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=June 2022}} | |||

| ] in Jerusalem. This is a site of Christian pilgrimage built where Christian Roman authorities pinpointed the purported location of Jesus' burial and resurrection in Jerusalem in 325.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=xxiii}} One of the objectives of the Crusades was to free the Holy Sepulchre from Muslim control.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=1}}]] | |||

| The ] in Jerusalem. This was constructed in 325, on the purported site of Jesus' burial and resurrection. It became a site of Christian pilgrimage, and one of the goals of the Crusades was to recover it from Muslim rule.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=xxiii}}{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=1}}]] | |||

| The '''crusading movement''' encompasses the framework of ] and ]s that described, regulated, and promoted the ]. The crusades were ]s that the ] ] initiated, supported, and sometimes directed in the ]. The members of the Church defined this movement in legal and ] terms that were based on the concepts of holy war and ]. In theological terms, the movement merged ideas of ] wars that were believed to have been instigated and assisted by God with ] ideas of forming ]. The institution of crusading developed with the encouragement of church reformers the 11th{{nbsp}}century in what is commonly known as the ] and declined after the 16th{{nbsp}}century Protestant ]. | |||

| The '''crusading movement''' encompasses the framework of ] and ]s that described, regulated, and promoted the ]. The crusades were ]s that the ] ] initiated, supported, and sometimes directed during the ]. The members of the church defined this movement in legal and ] terms based on the concepts of holy war and ]. The movement merged ideas of ] wars, that were believed to have had God's support, with ] ]. Crusading as an institution began with the encouragement of the church reformers who had undertaken what is commonly known as the ] in the 11th{{nbsp}}century. It declined after the ] began during the early 16th century. | |||

| The idea of crusading as holy war was based on the ] ]. A "just war" was one where a legitimate authority is the instigator, there is a valid cause, and it is waged with good intentions. The Crusades were seen by their adherents as a special ]{{snd}}a physical and spiritual journey authorised and protected by the Church. The actions were both a pilgrimage and ], Participants were considered part of Christ's army and demonstrated this by attaching crosses of cloth to their outfits. This marked them as followers and devotees of Christ and was in response to biblical passages exhorting Christian "to carry one's cross and follow Christ". Everyone could be involved, with the church considering anyone who died campaigning a ]. This movement was an important part of late-medieval western culture, that impacted politics, the economy and wider society. | |||

| The idea of crusading as holy war was based on the ] ]. This theory characterized a "just war" as one with a legitimate authority as the instigator, waged with a valid cause and good intentions. The crusades were seen by their adherents as a special ]{{snd}}a physical and spiritual journey authorized and protected by the church. They were acts of both pilgrimage and ]. Participants were considered part of Christ's army and demonstrated this by attaching crosses of cloth to their outfits. This marked them as followers and devotees of Christ, referencing biblical passages exhorting Christians "to carry cross and follow Christ". Everyone could be involved, with the church considering anyone who died campaigning a ]. This movement was an important part of late-medieval western culture: it impacted politics, the economy and wider society. | |||

| The original focus and objective was the liberation of ] and the sacred sites of Palestine from non-Christians. The city was considered to be Christ's legacy and it was symbolic of divine restoration. The site of Christ's redemptive acts was pivotal for the inception of the First Crusade and the subsequent establishment of crusading as an institution. The campaigns to reclaim the Holy Land were the ones that attrcated the greatest support, but the crusading movement's theatre of war extended wider than just Palestine. Crusades were waged in the ], northeastern Europe against the ], the ], campaigns were fought against those the church considered ]s in France, Germany, and Hungary, as well as in Italy where Pope's indulged in armed conflict with their opponents. By definition all the crusades were waged with ] approval and through this reinforced the Western European concept of a single, unified Christian Church under the ] | |||

| The original focus and objective of the crusading movement was to take ] and the sacred sites of Palestine from non-Christians. These locations were pivotal for the inception of the ] and the subsequent establishment of crusading as an institution. The campaigns to reclaim the Holy Land were the ones that attracted the greatest support, but the crusading movement's theatre of war extended wider than just Palestine. Crusades were waged in the ], ] against the ], and in the ]; other campaigns were fought against those the church considered ]s in France, Germany, and Hungary, as well as in Italy against opponents of the popes. By definition, all crusades were waged with ] approval and through this reinforced the Western European concept of a single, unified Christian church ]. | |||

| {{Campaignbox Crusades|state=expanded}} | {{Campaignbox Crusades|state=expanded}} | ||

| == Major features == | |||

| ==Major Features== | |||

| {{further|Cluniac Reform|Gregorian Reform|History of the papacy (1048–1257)}} | {{further|Cluniac Reform|Gregorian Reform|History of the papacy (1048–1257)}} | ||

| Historians trace the beginnings of the crusading movement to the changes enacted within the ] during the mid and late 11th century.{{sfn|Bull|1995|p=26}} These are known as the ], from a term popularized by the French historian ]. He named the changes after one of the leading reforming ]s, ]. The use of the term oversimplifies what was in fact numerous discrete initiatives, not all of which were the result of papal action.{{sfn|Morris|1989|pp=80–81}} | |||

| A group of ] took control of the governance of the church with ambitions to use this control to eradicate behaviour they viewed as corrupt.{{sfn|Bull|1995|p=26}} This takeover was initially supported by the ] and by ] in particular, but went on to lead to conflict with his son, ]. The reformers believed in ], meaning the Pope was the head of all of Christendom as heir of ]. Secular rulers, including the emperor, were subject to this and could be removed.{{sfn|Barber|2012|pp=93–94}} | |||

| The Crusading movement's origins can be found in the significant changes within the Latin church during the mid-eleventh century. In the 1040s church ] gained control of the papacy. The reformers viewed this as the most effective method to eliminate what they saw as corruption in the church.{{sfn|Bull|1995|pp=22-24}} They believed in ]. That the Pope, as heir of ], was the hierarchical leader of all Christendom, including Byzantium. Secular rulers were only appointees who could be removed. {{sfn|Barber|2012|pp=93, 97}} The takeover was with the initial support ], but later in conflict with his son ].{{sfn|Bull|1995|pp=22-24}} The French historian ] popularised the description ] for the resulting innovations, named after one of the leading reformers ]. This description oversimplifies the complexity of events. There were numerous initiatives which were not all initiated by the papacy which took place across Europe and in different elements of the Church. Reformers opposed practices like ], ], and papal authority. There was internal opposition to some of Gregory VII's policies which led to a rift with the emperor and a schism within the papacy.{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=81}} Despite this, this faction created an ideological framework and a cohort within the clergy who viewed themselves as God's agents for the moral and spiritual renewal of ].{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=110}} Historians now see this as a pivotal moment for the movement because these were men who stood behind a concept of ] and would eventually seek to enact it.{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=144}}{{sfn|Lock|2006|p=277}} | |||

| The reformist groups opposed previously widespread behaviour such as ] and ].{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=80}} The changes were not without opposition, causing ] within the church and between the church and the emperor.{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=82}} However, the reform faction successfully created an ideology for the men they saw as God's agents. From the second half of the 11th{{nbsp}}century, it empowered them to reshape the church according to the moral and spiritual principles they upheld.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=110}} Historians consider that this was a pivotal moment, because the church was now under the control of men who supported a concept of ] and would plan to make it happen.{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=144}} | |||

| Three initiatives were necessary before this could be but into action. Firstly, this reform of the ] into an independent force that was motivated by the belief it had divine authority for religious renewal. This belief would lead to conflicts with the Holy Roman Empire, Muslim states, other Christian groups, and pagans. Secondly, the creation of crusading as a social institution through which the church could act militarily supported by armed nobility considered ].{{sfn|Latham|2011|p=240}}{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=108}}{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=338}} Lastly, the development of formal army structures for the raising of armies through which the church could advance its ambitions.{{sfn|Latham|2011|p=240}}{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=108}} The developments would lead to violent conflicts between the Church and its adversaries and have an impact on broader social and political transformations. These factors enabled the crusading movement, and its decline corresponded with their decreasing significance.{{sfn|Latham|2011|pp=240–241}} | |||

| The reformers now viewed the church as an independent force with God-given authority to act in the secular world for religious regeneration. The creation of the institutions of crusading were a means by which the church could act militarily with the support of the armed aristocracy. This would in turn lead to creation of formal processes for the raising of armed forces through which the church could enforce its will. While these fundamentals applied the crusading movement flourished, when they ceased to be significant the movement declined.{{sfn|Latham|2011|pp=240–241}}{{sfn|Latham|2012|pp=128-129}} | |||

| ===Christianity and war=== | |||

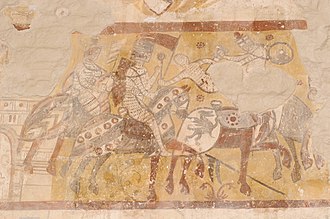

| ] from ] depicting the ] battling the ], the ]]] | |||

| {{further|Just war theory}} | |||

| Erdmann documented in ''The Origin of the Idea of Crusade'' the three stages of the development of a Christian institution of crusade: | |||

| * the argument that preserving Christian unity was a ''just cause'' for warfare; | |||

| * the ideas developed under ] that the conquest of pagans in an ''indirect missionary war'' was also in accordance; | |||

| * The paradigm developed under the reformist popes ], ], and ], in the face of ]ic conflict, that war should be waged to defend Christendom.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=121}} | |||

| Historians, such as Erdmann, believed that from the 10th{{nbsp}}century the ] movement restricted conflict between Christians. Certainly, this is evident in ]'s speeches, but it is now thought that the influence was limited and had even ended by the time of the crusades.{{sfn|Jotischky|2004|pp=30–38}} In the 11th{{nbsp}}century, the Church sponsored conflict with Muslims on the southern peripheries of Christendom, including the ] in what is now northern Spain and the ] of the ].{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=18–19, 289}} For the philosophers and combatants, the conflict in Spain provided practical foundational arguments for the movement.{{sfn|Madden|2013|p=15}} In 1074, Gregory VII planned a holy war in support of Byzantium's struggles with Muslims, which produced a template for a crusade, but he was unable to garner the required support, possibly because he stated he intended to lead the campaign himself.{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|p=16}} | |||

| The Church defined crusading in legal and theological terms based on the theory of holy war and the concept of ]. The theology developed from a merger of two themes. Firstly, the wars fought by the Israelites in the ]. It was believed these were instigated and assisted by God. Secondly, the ] concept of forming an individual relationship with Christ that came from the ]. Holy war was based on {{lang|la|bellum justum}} which was the ] ]. This was Christianised by a 4th-century theologian called ], and ] developed this further in the 11th{{nbsp}}century into {{lang|la| bellum sacrum}}. This is what became the ] of Christian holy war.}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=14–16,338,359}} Augustine's argument was that war was sinful, but a "just war" could be rationalised if three criteria were met. These criteria were that the war must be declared by a legitimate authority, it was defensive or for the recovery of rights or property and the combatants intentions must be good.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=98}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=14}} Later, ] consolidated the writing on just war theories into {{lang|la|Collectio Canonum}} or ''Collection of Canon Law''.{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|p=61}} In the 13th{{nbsp}}century these principles formed the foundation of a doctrine of ] developed by ] and others.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=14–15}} The church used canon law to justify ]. This was by judging Rome as the ] and any papal war as being waged by the church in purely defensive crusades to protect theoretical Christian territory.{{sfn|Jotischky|2004|pp=195–198}} | |||

| ===Penance and indulgence=== | === Penance and indulgence === | ||

| {{further|Crusade indulgence}} | {{further|Crusade indulgence}} | ||

| Before the crusading movement was established, the church had developed a ] that enabled Christians to gain forgiveness and ] from the church on behalf of God. They did this by demonstrating genuine ] through ] and acts of ]. In the latter part of the 11th{{nbsp}}century, Christianity's requirement to avoid violence was still a significant issue for the warrior class, so Gregory VII offered them a potential solution. This was that they too could have their sins forgiven if they supported him in fighting for papal causes, but only if this service was given altruistically.{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|p=61}}{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=123}} When ] launched the ] at ] in November 1095, he made two offers to those who would travel to Jerusalem and fight for control of the sites Christians considered sacred. Firstly, those who fought would receive exemption from ] for the sins they committed. Secondly, while they were on crusade, the church would protect their property from harm.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=69–70}} The enthusiasm of the crusading movement was a challenge to what had been conventional theology. A letter from ] to ],{{When|date=January 2025}} illustrates this point. Sigebert criticises ] and congratulates Robert on his safe return from Jerusalem but pointedly omits any reference to the fact that Robert had been on a crusade.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|p=80}} | |||

| Later popes developed the institution further, declaring that crusaders would not only avoid divine punishment for their sins, but that their guilt and the sins themselves would be expunged. This was achieved by the church granting what was called a ].{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=3}} ] extended the same privileges and protections of property to crusaders' relations.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=2}} ] reinforced the importance of the oaths crusaders took. He also emphasised the view that the forgiveness of sin was a ], not a reward for the suffering endured by the crusader while on crusade.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=235–237}}{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=524–525}} It was in the 1213 ] called {{lang|ln|]}} that he reached out beyond the noble warrior class, offering all Christians the opportunity to redeem their vows without going on crusade. The unforeseen consequence of this was the creation a market for religious rewards.{{Clarification|reason=I *think* this is talking about the movement from "your sins are forgiven if you go on crusade" to "your sins are forgiven if you pay the Church some money", but it's not very clear.|date=January 2025}} Later, this scandalized some devout Christians and thus became a catalyst for the 16th{{nbsp}}century ].{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=533–535}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=238–239}} At that time, some writers continued to seek atonement for their sins through the practice of crusading while ] (the English ]) and others saw this as "the impure ], and ]"{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|pp=40–41}} | |||

| Popes continued in the practice of issuing crusade bulls for generations, but ] and ] created{{When|date=January 2025}} an international rule of law that was secular rather than religious.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=919}} The wars against the ] and in defence of Europe were conflicts on which ], ], and ] could agree in principle. So the importance to recruitment of the granting of indulgences became increasingly redundant and declined.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=439-440}} | |||

| As late as the 16th{{nbsp}}century, writers were still looking for redemption in crusading, while others{{snd}}such as English ] ]{{snd}}saw them as "the impure ], and ]".{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|pp=40–41}} ], ], and ] could agree on other grounds for the Turkish wars and the role of the granting of indulgence declined.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=439-440}} ] and ] developed international laws of war that discounted religion as a cause, in contrast to popes, who persisted in issuing crusade bulls for generations.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=919}} | |||

| === |

=== Christianity and war === | ||

| ] from ] depicting the ] battling the ] during the 1242 ]]] | |||

| {{further|Chivalry|Knighthood}} | |||

| {{further|Just war theory}} | |||

| {{further|Miles Christianus|Churches Militant, Penitent, and Triumphant}} | |||

| The 4th-century theologian ] Christianized ] theories of {{lang|la|bellum justum}} or ].{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|pp=34-35}} In the 11th century, ] extended his thinking to create the paradigm of Christian {{lang|la|bellum sacrum}} ({{Gloss|holy war}}).{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=14–16, 338, 359}} This theory was based on the idea that if it met three criteria Christian warfare could be justified even though it was considered a sin. Firstly, it must be declared by an authority that the church considered legitimate. Secondly, the war must have defensive objectives or to be for the recovery of stolen property and rights. Lastly, the intentions of those taking part must be good.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=98}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=14}} Using this justification the church supported various Christian groups in conflicts with their Muslim neighbours at the borders of Christendom. In what is now Northern Spain, encouragement was given during the ]; the ] of Southern Italy were supported in their ] of the ] and in 1074 Gregory VII planned to lead a campaign himself in support of the Byzantine Empire. He was unable to gather the necessary support, possibly because his personal leadership was unacceptable. Despite this, his plans left a template for future crusades, as did the campaigns in Spain where leading thinkers and fighters developed practical and fundamental arguments for the crusading movement.{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|p=16}}{{sfn|Madden|2013|p=15}} | |||

| When crusading began ] was just developing, but in time it played a central role in the crusading ethos, by shaping the ideals and principles of knights. The knighthood was separate from the aristocracy while being praised in literature.{{sfn|Bull|1995|p=22}} The control of fortifications dominated society. The men who manned these became the basis of the knighthood. Simultaneosly, new military tactics based on the use of heavy cavalry combined with the growing naval capability of Italy's ], made the First Crusade feasible. The new methods of warfare led to codes, ethics, and ideologies. Knighthood required combat training, leading to solidarity and the rise of combat as sport.{{sfn|Morris|1989|pp=150, 335}} The resulting tournaments were used by crusade preachers to obtain vows of support from attendees, conduct campaigns of persuasion, and make announcements of senior figures taking of the cross.{{sfn|Lloyd|1995|pp=43–44}} Despite the courage of knights and some notable generalship, the crusades in the ] were typically unimpressive. Military strategy and medieval institutions were immature in feudal Europe at the time and power was too fragmented for the creation of disciplined units.{{sfn|Honig|2001|pp=113—114}} | |||

| Around 1083, the thoughts and writing on these theories were consolidated into {{lang|la|Collectio Canonum}} or ''Collection of Canon Law'' by ].{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|p=61}}{{sfn|Morris|1989|pp=127-128}} ] and others extended these theories in the 13th{{nbsp}}century into a concept of ].{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=14–15}} This enabled various popes to use canon law in the call for crusades against their ]. The argument was that Rome was the estate of St Peter, so the popes' Italian campaigns were considered defensive and fought for the preservation of Christian territory.{{sfn|Jotischky|2004|pp=195–198}} | |||

| The idealised perfect knight was represented in literature such as the c1130 romance Alexandre. This related adventurous ideas of the courage, charity, and good manners. These ideals of excellence, martial glory, and romantic love conflicted with the spiritual views of the Church. While the Church feared this knightly caste, it also co-opted it for support. The Church developed liturgical ]s to sanctify new knights..{{sfn|Morris|1989|pp=335-336}} Kings even began depicting themselves as knights to order to project their power.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=53}} | |||

| The thinking of church on these themes combined two ideas in the creation of crusading, one from the ] and one from the ]. The first was that the wars of the Jews were believed to have been instigated by the will of God. The second was the ] ideas related to Christians forming individual relationships with Christ that came from the New Testament. In this way the church was able to combine the ideas of holy war and ] to create the legal and theocratic justifications for the crusading movement.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=14–16, 338, 359}} The historian Carl Erdmann mapped out the three stages for the argument creating the institution of the crusading movement: | |||

| Crusade participation was considered integral to idealised knightly behaviour.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=50}} It became part of the knightly class's self-identification, in a way that created a cultural gap with other social classes.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=64}} From the ] onward, crusading became an adventure that was normalised in Europe. This altered the relationship between knightly enterprise, religious, and worldly motivation.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|p=84}} | |||

| * Defending Christian unity was a just cause. | |||

| * ] and his followers' ideas for missionary conquest were also in accordance. | |||

| * ] should be fought in defence of Christendom, an idea developed under the reformist popes ], ], and Gregory VII.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=121}} | |||

| === |

=== Knights, chivalry and the military orders === | ||

| {{further|Chivalry|Knighthood|Military order (religious society)}} | |||

| ] with senior knights, wearing the ] on their habits. Dedicatory miniature in ''Gestorum Rhodie obsidionis commentarii'' (account of the ]), BNF Lat 6067 fol. 3v, dated 1483/4.]] | |||

| ] with senior knights, wearing the ] on their habits. Dedicatory miniature in ''{{lang|la|Gestorum Rhodie obsidionis commentarii}}'' (account of the ] in 1480), BNF Lat 6067 fol. 3v, dated 1483/4.]] | |||

| {{further|Military order (religious society)}} | |||

| Innovations in military technology and thinking made the first crusades feasible. Military tactics developed to utilize heavily armoured cavalry and control of society was achieved by the development of ]. These required men for garrisons, the extensive training or which in turn created new social mores and led to the rise of combat as sport. At sea increasingly large navies were deployed, built by Italy's ]. {{sfn|Morris|1989|pp=150, 335}} At this time although knights were praised in literature they remained distinct from the aristocracy. Crusading and ] developed together, and in time chivalry helped shape the ethos, ideals and principles of crusaders.{{sfn|Bull|1995|p=22}} Tournaments were held where knights could exhibit their martial prowess. This provided venues where the crusading movement could recruit, spread propaganda and announce the recruitment of senior figures.{{sfn|Lloyd|1995|pp=43–44}} However, even though crusading knights and some notable commanders demonstrated courage and commitment in military terms the campaigns in the ] were not typically impressive. In feudal Europe, the formation of disciplined units was a significant challenge, strategic approaches and institutional frameworks were underdeveloped, and power was too fragmented to support cohesive organisation.{{sfn|Honig|2001|pp=113–114}} | |||

| There were few innovations in the crusading movement that originated from the polities created in the ] following the First Crusade. These polities are generally known as the ] and they tended to follow the customs of western European homelands. One of the exceptions was the creation of military religious orders.<ref>{{harvnb| Prawer|2001| p=252}}</ref> | |||

| Literature presented the exemplar of an idealized, perfect knight in works such as ] written around 1130. These works celebrated adventure, courage, charity, and refined manners. However, the Church could not fully embrace all of these values they promoted. Its' spiritual views contrasted with ideas of excellence, achieved glory through military deeds and romantic love. While the church feared the warrior class, it still needed to co-opt its power and demonstrated this symbolically through the development of liturgical ]s to sanctify new knights.{{sfn|Morris|1989|pp=335–336}} In time, kings represented themselves as members of the knighthood for propaganda purposes and crusading became to be seen as integral to the ideas of this ideal.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=53}}{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=50, 64}} From the time of the ], crusading became an adventure normalized in Europe, thus creating a divide between the knights and other social classes and altering the relationship between knightly adventure, religious, and secular motivation.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|p=84}} | |||

| The ] were delivering ongoing medical functions in Jerusalem before the First Crusade but added a martial element to their to become a much larger military order. The ] were founded around 1119 by a small band of knights who dedicated themselves to protecting pilgrims en route to Jerusalem. Many other orders followed.<ref>{{harvnb|Asbridge|2012|pp=168-169}}</ref> These military orders were Latin Christendom's first professional armies, supporting the ] and the other crusader states. <ref>{{harvnb| Asbridge|2012| p= 168}}</ref> In time they developed a reach that crossed national borders. This was through papal support that led rich donations of land and revenue across Europe, a steady flow of recruits and the wealth to maintain multiple fortifications. Eventually, the orders even developed independent autonomous powers.<ref>{{harvnb| Asbridge|2012|pp=169–170}}</ref> | |||

| In the polities created by the crusading movement in the ] known as the ] the creation of military religious orders was one of the few innovations from outside Europe.{{sfn|Prawer|2001|p=252}} In 1119 a small band of knights formed to protect pilgrims journeying to Jerusalem. These became the ] and many other orders followed this template. The ] were already providing medical services to which was added a military wing leading to a much larger organisation. These orders became Latin Christendom's first professional fighting forces and played a major part in the defence of the ] and the other crusader states.{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=168–169}} Papal acknowledgement of the orders encouraged significant donations of money, land and recruits from across western Europe. The orders used this to build their own castles and to develop international autonomy.{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=169–170}} When the final Christian ruled territory in the Holy Land was lost following the ], the Hospitallers relocated to ]. Later the order conquered and ruled ] (1309–1522) and finally settled in ] (1530–1798). King ] dissolved the Templar order around 1312, likely driven by financial and political motives. He exerted pressure on ] to disband the Templars. The resulting charges of ], magic, and heresy cited in ] such as {{lang|la|]}} and {{lang|la|]}} were probably unfounded.{{sfn|Davies|1997|p=359}} | |||

| ===Common people=== | === Common people === | ||

| {{further|Popular crusades}} | {{further|Popular crusades}} | ||

| ] leading the ]. From the ''{{lang|es|]}}'' (14th century)]] | |||

| From the Mid-20th Century historians took a greater interest than before questioning why significant numbers of the lower classes travelled on the early crusades or took part in the unsanctioned popular outbreaks of the 13th and 14th- centuries.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|pp=8–9}} The papacy wanted to recruit warriors who could fight, but in the early years of the movement it was impossible to exclude others, including women. Indeed, retinues included many to provide services who could also fight in emergencies.{{sfn|Bull|1995|p=25}} The church considered that engaging in crusade must be entirely voluntary. Recruitment propaganda used understandable mediums which could also be unclear. For the poor the institution of the crusade was offensive, while in church doctrines it was an act of self-defence.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|pp=8–9}} | |||

| From the 12th{{nbsp}}century onwards, the crusading movement generated propaganda material to spread the word. A good example was the work of a Dominican friar called ]. In 1268 he gathered the best crusading arguments in one work.{{sfn|Lloyd|1995|pp=46–48}}{{sfn|Morris|1989|pp=458, 495}} The poor had different viewpoints to the theologians. Often based on an end of the world ] belief. When Acre was lost to the Egyptians there were resulting popular but brief outbursts of crusade fervour.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=263}} However, the most Christians did not typically crusade to Jerusalem. Instead, they would often build models of the ] or dedicate places of worship. These were acts that existed before the crusading movement, but they became increasingly popular in association. They may have formed part of other forms of regular religious devotion. In 1099 Jerusalem was known as "the remotest place", but these practices made crusading tangible.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=xxv}} | |||

| In 1096, 1212, 1251, 1309, and 1320 uncontrolled peasant crusading erupted. Except for the ] of 1212, these were all accompanied by violent ]. It is not known why 1212 was the exception. The literate classes were hostile to this particular unauthorised crusade but mytho-historicised it so effectively that it has become one of the most evocative verbal accounts from the Middle Ages and this has remained in European and American imagination. The term "Children's Crusade" requires clarification in that neither word "children"{{snd}}in Latin {{lang|la|pueri}}{{snd}}nor the word "crusade"{{snd}}described in Latin as {{lang|la|peregrinatio}}, {{lang|la|iter}}, {{lang|la|expeditio}}, or {{lang|la|crucesignatio}}{{snd}}are a completely accurate or inaccurate description.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|p=xiii}} Although, there are a numerous written sources they are of doubtful veracity. They differ on dates and details and utilise mytho-historical motifs and plot lines.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|pp=9–14}} At the time, clerics used the sexual purity and "innocence" of the {{lang|la|pueri}} as a critique of the sexual misbehaviour seen in the formal crusades. This misbehaviour was considered to be the source of God's anger and the ultimate reason for the failure of campaigns.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|p=24}} | |||

| Unsanctioned popular crusading exploded in 1096, 1212, 1251, 1309, and 1320. These all exhibited violent ] with the exception of the ] of 1212. Despite hostility from the literate these crusades became so mytho-historicised in the written histories that they are some of the most highly remembered events transmitted by word of mouth from the period. That said "Children's Crusade" is not a precise definition. The "Children's Crusade" of 1212 did not consist solely of children, despite its name. Contemporary and later chroniclers described the participants as pueri, which is Latin for "youths". However, the term could refer to an unmarried boy, someone below the age of maturity and to denote someone of low social status, such as a shepherd, regardless of age.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|pp=629-630}}{{sfn|Madden|2013|p=137}} The many surviving written sources are of questionable accuracy. Dates and details are not consistent and they are interwoven with typical myth-history stories and ideas.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|pp=9–14}} Clerical writing contrasted the imagined innocence of the {{lang|la|pueri}} with the sexual licence that was seen on the official crusades. It was the sin of the crusaders that was believed to bring God's displeasure and explain why the crusades were not successful.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|p=24}} | |||

| ===Perception of Muslims=== | |||

| === Perception of Muslims === | |||

| {{further|Christianity and Islam}} | {{further|Christianity and Islam}} | ||

| ] from an ] of the ''{{lang|fr|Grandes chroniques de France}}'' (15th century), currently preserved in the ], ]]] | |||

| Ethnic identity was a social construct in medieval times. In the opinion of Christians, all humanity shared descent from ] and ]. Differences were cultural, rather than racial. ]rs of the First Crusade often use the ethno-cultural term inherited from the Greeks of ] of barbarians or {{lang|la|barbarae nationes}}. This is best understood in medieval terms as a differentiator from the self-identity of the word Latins, that the crusaders used for themselves.{{sfn|Jubb|2005|p=226}} | |||

| Literature such as the 11th-century {{lang|fr|chanson de geste}} '']'' did not explicitly mention the crusades. But is likely there were propaganda motivations behind presenting the Muslim characters in monstrous terms and as idolators. Whatever the motivation Christian writers continued to use these representations.{{sfn|Routledge|1995|p=93}} Muslim characters were depicted as evil and dehumanized, with their physical traits described as devilish and their skin portrayed as dark. Islamic rituals were mocked, and insults were directed at ]. This caricature persisted long after territorial conflicts had ended. The term "Muslim" was never used; instead, they were referred to as "]s" alongside other derogatory labels such as ], ], enemy of God, and ]. This literature reinforced the Church's portrayal of the Crusades as a ] struggle between good and evil.{{sfn|Jubb|2005|pp=227–229}} Historian ] suggests that the Church's intent was to eliminate its rivals' ideology in order to justify Christianity's participation in aggressive and violent conflicts.{{sfn|Jubb|2005|p=232}} This prejudice was not derived from ethnic identity or race. The church considered that all of humanity were descended from ] and ]. Typical of medieval opinion this was a social construct in which the differentiators were cultural. For example, the ] Chroniclers adopted terminology inherited from the Greeks of ]. They use the ethno-cultural term {{lang|la|barbarae nationes}} 'barbarious nations' for the Muslims, and self-identified crusaders as ].{{sfn|Jubb|2005|p=226}} | |||

| There are no specific crusading references in the 11th{{nbsp}}century {{lang|fr|chanson de geste}} {{lang|fr|]}} but the author presents a twisted representation of Muslims as monsters and idolators. Possibly this is for intentional propaganda purposes. Christian writers repeated this imagery elsewhere.<ref>{{Harvnb|Routledge|1995|p=93}}</ref> Muslims were represented as evil, dehumanised, monstrous aliens with black complexions and devilish faces. Even after wars for territory had declined, this representation of Muslims continued. The noun Muslim was unused in the chronicles instead Saracen was used. This described a member of an Islamic community not a race. Infidel, gentile, enemy of God, and pagan were also used. For Christian clergy the conflict was a ] contest between good and evil.{{sfn|Jubb|2005|pp=227–228}} Muslims were represented antagonistically, inaccurately and as degenerate beasts. Islamic rites were caricatured and ] was insulted.{{sfn|Jubb|2005|p=229}} Historian ] argues that to self-justify Christianity's move to war, their enemies needed to be ideologically destroyed.{{sfn|Jubb|2005|p=232}} | |||

| As contact increased respect for the Turks developed. {{lang|la|]}} presents some negativity but also respect for them as opponents. It was considered values of chivalry were shared. In the {{lang|fr|]}} they were presented as equals following the same codes of conduct. By the time of the ] the class differences were shown as within camps rather the between camps. The elite warrior class in both camps shared an identity that was not divided on religious or political groups. Epics began to include incidents of conversion to Christianity. This in part may have offered hope for a positive resolution at a time when military failure pointed to defeat.{{sfn|Jubb|2005|pp=234–235}} | |||

| There remain a number of ] from the many crusaders who also wrote poetry such as ], ], and ]. In return for ] from the leaders of the crusades, poets wrote praising the ideals of the nobility.{{sfn|Routledge|1995|pp=94–95}} These relationships were of a feudal nature and were presented in this context. To demonstrate this, the crusaders were God's vassals fighting the restore to him the (Holy) land.{{sfn|Routledge|1995|pp=97}} Muslims were presented as having stolen this land. Their mistreatment of its Christian inhabitants was considered an injustice for which revenge was required. In return, the perception of the Islamic ] resulted in an opposing position. This encouraged violent resistance to the idea of the imposition Christian governance on these terms.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=120}} | |||

| The origins of the crusading movement lie within the nature of Western Christian society in the late eleventh century rather than any external provocation, despite intense propaganda about the ] actions. While the ] Turks' incursions into ] increased after the Byzantine defeat at the ] in 1071, Islam had controlled Jerusalem since 638 without eliciting a comparable Western reaction. Urban II's appeal at Clermont in 1095 resonated strongly because it aligned with attitudes already prevalent in Western Christian experience.{{sfn|Barber|2012|p=117}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| == History == | |||

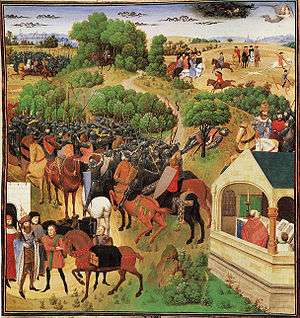

| ], ], '']'', BnF Fr{{nbsp}}5594, {{Circa|1475}} ]] | |||

| ], ], ''{{lang|fr|]}}'', BnF Fr{{nbsp}}5594, {{Circa|1475|lk=no}} ]] | |||

| {{further|Res publica Christiana|First Crusade}} | {{further|Res publica Christiana|First Crusade}} | ||

| In the late 11th and early 12th{{nbsp}}centuries, the papacy became an entity capable of organized violence in the same manner as secular kingdoms and principalities. This required command and control systems that were not always fully developed or efficient. The result was the papacy leading secular fighting forces for its own ends.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=117}} | |||

| This was begun by ] around 1059. He involved the papacy in the long running conflict with Muslims in the Mediterranean region. The church became involved in, and gave approval for, campaigns in ], ] and ] where the church worked with the republics of ] and ].{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=147}} | |||

| Urban II laid the foundations of the Crusading movement at the ] in 1095. He was responding to requests for military support from the Byzantine Emperor ] that he received during the earlier ]. Alexios was fighting ] who were migrating into ], threatened ] and had formed the ]. Urban expressed two key objectives for the Crusade. Firstly, the freeing of Christians from Muslim rule. Secondly, freeing the church known as the Holy Sepulchre from Muslim control. This was believed to mark the location of Chris's tomb in Jerusalem.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=65, 69-70}}{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=1}} | |||

| In the 12th{{nbsp}}century, ] and the ] elaborated on ]. Aquinas continued this in the 13th{{nbsp}}century.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=14,21}} This extended the reformers philosophy to end secular control of the Latin church and impose control over the ]. It developed further the paradigm of working in the secular world for the imposition of what the church considered justice.{{sfn|Latham|2012|p=118}} After the initial success of the early Crusades the settlers who remained or later migrated were militarily vulnerable. During the 12th and 13th centuries, frequent supportive expeditions were required to maintain territory that had been gained. A cycle developed of military failure, pleas for support and declarations of Crusades from the church.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=36}} | |||

| At the Council of Clermont, Urban II laid the foundation of the crusading movement. The catalyst was an embassy from the Byzantine Emperor ] to the earlier ], requesting military support in his conflict with the ]. These ] were expanding into ] and threatening ]. Urban's two expressed objectives for the campaign were freeing Christians and the Holy Sepulchre{{snd}}the tomb of Christ in Jerusalem{{snd}}from Muslim control{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=65, 69-70}}.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=1}} | |||

| The military vulnerability of the settlers in the East required further supportive expeditions throughout the 12th and 13th centuries. In each generation, these followed the pattern of a military setback in the East, followed by a request for aid, and then crusade declarations from the papacy.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=36}} | |||

| === 12th century === | === 12th century === | ||

| ] granting the captured ] to ]]] | ] granting the captured ] to ]]] | ||

| The success of the First Crusade that began the Crusading movement and the century was seen as astonishing. The explanation for this was given that it was only possible through the will of God.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|pp=78–80}} Paschal succeeded Urban as pope before news of the outcome reached Europe. He had experience of the fighting in Spain so readily applied similar remissions of sin to the combatants there, without the need for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=293}} He did not stop there with the application of the institutions of Crusading. He also did this against the Orthodox Christians of Byzantium in favour of ] for political reasons in Italy.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=335}} | |||

| It was in certain social and feudal networks that early Crusade recruitment concentrated. Not only did these groups provide manpower, but also funding. Although it may have been pragmatic acceptance of the pressure of the reform movement that prompted the sales of churches and ]. These families often had a history of pilgrimage, along with connections to ] and the reformed papacy. They honoured the same saints. With inter-marriage this cultural mores were spread through society.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|p=87}} Paschal's successor ] shared his Spanish interests. In 1123, at the ] it was decided that crusading would be deployed in both Iberia and the ]. The outcome was a campaign by ] against Granada in 1125.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=2}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=293}} | |||

| The first century of crusading was simultaneous with the ]. Crusading themes were used in the writing that was developing in France and Germany. There are ] versions, and in the literary language of southern France{{snd}}], of ] such as the {{lang|fr|]}} about the ] and the {{lang|fr|]}} about the ]. In French, these were known as {{lang|fr|]}}, taken literally from the Latin for deeds done.<ref>{{Harvnb|Routledge|1995|pp=91–92}}</ref> ]s dedicated to crusading are rare. But many works survive in Occitan, French, German, Spanish, and Italian that include crusading as a topic or use it as an ], from the time of the Second Crusade onward. Occitan ] ] and ] wrote songs with themes called {{lang|fr|]}} and about absent loves called {{lang|fr|]}}. Crusading became the subject of songs and poems rather than creating a new genre. Many songs about the third and fourth crusades remain, written by troubadours, and their northern French {{lang|fr|]}} and German {{lang|gn|]}} equivalents.<ref>{{Harvnb|Routledge|1995|pp=93–94}}</ref> Crusade songs served multiple purposes. They provided material, variations on ], allegories, and paradigms. Through song audiences learnt about crusading in a way unmediated by the Church. These songs reinforced the nobility's identity and its position in society. They also provided for the expression of injustice and criticism of mismanagement when events did not go well.<ref>{{Harvnb|Routledge|1995|p=111}}</ref> | |||

| The First crusade's success was astonishing and seen as only possible through God's will.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|pp=78–80}} Urban's successor, Paschal II's Spanish experience led him to offer Spaniads sin remission to fight Muslims in their homeland, rather than journey to Jerusalem.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=293}} He also did this gain support to suppress political opposition in Italy in support of ]'s campaign against Byzantium.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=335}} Early crusade recruitment concentrated in certain families and networks of vassals. These groups demonstrated their commitment through funding, although the sale of churches and ] may have been a pragmatic acceptance that retaining these properties was unsustainable in the face of the reform movement in the Church. These kinship groups often exhibited traditions of pilgrimage to Jerusalem, association with ], the reformed papacy, and the veneration of certain saints. Marriage spread these values into other groups.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|p=87}} ] was another with Spanish experience. In 1123, He proposed that crusading should be conducted in both Iberia in the ] with ] XI at the ]. This led to the campaign by ] against Granada in 1125.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=2}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=293}} | |||

| Strategically, the crusaders could not hold Jerusalem in isolation, which led to the establishment of other western polities known as the Latin East. Even then, these required regular defensive expeditions, supported by the developing military orders. The movement expanded into Spain with campaigns in 1114, 1118, and 1122. Eugenius III he drew ideological links between fighting the ], the reconquest of Spain and the ]. The crusade in the East was not a success, which left the movement at the lowest ebb that it would be until the 1400s. There were still three campaigns in Spain, and in 1177 one in the East, but the movement remained diminished until news of the defeat at the hands of the Muslims in the ] created consternation throughout Europe and reignited enthusiasm.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=2}} | |||

| The crusaders established polities known as the Latin East, because it was impossible to defend Jerusalem in isolation. Despite this, regular campaigns were required in addition to the capability provided by the military orders. In Spain further expeditions were launched in 1114, 1118, and 1122. Eugenius III developed an equivalence between fighting the ], fighting the Muslims in Spain and the Muslims in Syria. The later crusade failed, with the result that the movement suffered its largest crisis until the 1400s. Fighting continued in Spain where there were three campaigns and another in the East during 1177. But it was the news of the crusaders defeat by the Muslims at the ] that restored the energy and commitment of the movement.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=2}} | |||

| From the latter part of the century, Europeans adopted the terms {{lang|la|crucesignatus}} or {{lang|la|crucesignata}}, meaning "one signed by the cross". Crusaders identified themselves by attaching cloth crosses to their clothing. This fashion derived from the biblical passages in ]:23, ]:34 and ]:24 "to carry one's cross and follow Christ".{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=478}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=2}} Through this action, a personal relationship between Crusaders and God was formed. This was a mark of the crusader's spirituality. Anyone could become a crusader, irrespective of gender, wealth, or social standing. This was known as an {{lang|la|imitatio Christi}}, an "]", a sacrifice motivated by charity for fellow Christians. Those who died campaigning were martyrs.{{sfn|Buck|2020|p=298}} | |||

| The ] coincided with the early years of crusading. Crusading themes were the subject of developing ] literature in the languages of Western Europe. Examples of ] include the {{lang|fr|]}} describing the events in the 1268 ] and {{lang|fr|]}} about the ] against the ] in Southern France. These are given the collective name of {{lang|fr|]}} in the ] which is borrowed from Latin for the term deeds done.{{sfn|Routledge|1995|pp=91–92}} Surviving ] about Crusading are rarer. But there are examples in the literary language of southern France, ], French, German, Spanish, and Italian that touch on the topic in an allegorical that date from the later half of the century. Two notable Occitan ] were ] and ]. They composed songs in the styles called {{lang|fr|]}} and {{lang|fr|]}} on the subject of lost love. Crusading wasn't a distinct genre, but the subject. The troubadours had northern French equivalents called {{lang|fr|]}} and German ones called {{lang|de|]}}. Collectively they left bodies of works themed on the crusades later in the century.{{sfn|Routledge|1995|pp=93–94}} This material transmitted information about crusading unmediated by the church. It is reinforced the status quo, the class identity of the nobility and its position in society. When the outcomes of events was less positive this was also a method of spreading criticisms of organization and behaviour.{{sfn|Routledge|1995|p=111}} | |||

| ===13th century=== | |||

| Crusade ] was intricately linked with a prophetic sensibility at the end of the 12th{{nbsp}}century. ] included the war against the infidels in his cryptic conflations of history combining past, present, and future.{{sfn|Barber|2012|p=408}} Foreshadowing the Children's Crusade, he believed that the third of his three ages of history was the age of the Holy Spirit. The representatives of this were children, or {{lang|la|pueri}}. ] such as ] saw themselves as {{lang|la|ordo parvulorum}}{{snd}}an "order of little ones" amongst a revivalist enthusiasm and a spirit of ]. The '']'' added apocalyptic elements of mytho-history to the Children's Crusade. In 1213, Innocent III called for the ] by announcing that the days of Islam were over.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|pp=24–26}} | |||

| In the latter part of the century Europeans developed language, fashion and cultural mores for crusading. Terms were adopted for those involved such as {{lang|la|crucesignatus}} or {{lang|la|crucesignata}}. These indicated that they were marked by the cross. This was reinforced by cloth crosses that they attached to their clothes. All of this was taken from the Bible. ]:23, ]:34 and ]:24 all implored believers to pick up their cross and follow Christ.{{sfn|Morris|1989|p=478}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=2}} It was a personal relationship with God that these crusaders were attempting to form. It demonstrated their belief. It enabled anyone to become involved, irrespective of gender, wealth, or social standing. This was {{lang|la|imitatio Christi}}, an "]", a sacrifice motivated by charity for fellow Christians. It began to be considered that all those who died campaigning were martyrs.{{sfn|Buck|2020|p=298}} | |||

| ====Propaganda==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The crusading movement brought together supporters within papal circles, monastic orders, ] friars, and the developing universities. Despite this seeming unity achieving uniformity in medieval Christendom was in practice challenging. Central church authority lacked the bureaucratic infrastructure and control necessary to make this happen.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=20}} The Cistercian Order, the ] and Franciscans provided propaganda for campaigns. The message varied, but the aim of papal control remained. Aristocratic families and feudal hierarchies played key roles in disseminating messaging. Courts and tournaments were useful gatherings where stories, songs, poems, and news were exchanged. The ] were hostile following the Albigensian Crusade in their homeland, but songs about the crusades gained popularity. Books, churches, and palaces included visual representations that contributed to the dissemination of information. Church art and architecture, including murals, stained glass windows, and sculptures, often depicted themes related to the movement.{{sfn|Forey|1995|p=196}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=117}} Crusading themes featured in literary works include include romances, travelogues like ], poems such as ] and ]'s ], and works by ].{{sfn|Madden|2013|p=155}}{{sfn|Housley|2002|p=29}}{{sfn|Mannion|2014|p=21}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=330}} Nationalism was largely absent. Instead great men were praised, such as ] and members of leading families.{{sfn|Richard|2005|p=207}} | |||

| === |

=== 13th century === | ||

| {{further|Papal income tax}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| From 1198 when he was elected pope, Innocent III reformed the ideology and practices of crusading. He created a new executive office to organise the Fourth Crusade. In each province of the Church he appointed executors and utilised freelance preachers such as ]. By the time of the Fifth Crusade this system developed into executive boards with ] power, while the papacy codified preaching. ]s and archdioceses were required to report to these bodies on promotional policy. Implementation was pragmatic and ad-hoc because of political circumstance, but local propaganda was more coherent and greater than before.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=46}} Innocent III increased campaign funding through the introduction of taxation and by encouraging donations.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=235–237}}{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=524–525}} In 1199, he became the first pope to enforce papal rights by deploying the conceptual and legal apparatus developed for crusading against his Christian opponents.{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=533–535}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=238–239}} From the 1220s, crusader privileges were regularly granted to those who fought those Christians the papacy considered ], heretics, or ]atics.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=336}} | |||

| Towards the end of the 12th{{nbsp}}century, the crusading movement existed in a culture where it was believed that everything that happened was predestined, either by God or fate. This ] meant that the population welcomed, accepted and believed in a wide range of prophecy. One significant example of this was the writing of ]. He included the fighting of the infidel in opaque works that combined writings on the past, on the present, and on the future.{{sfn|Barber|2012|p=408}} These works foreshadowed the Children's Crusade. Joachim believed all history and the future could be divided into three ages. The third of these was the age of the Holy Spirit. The representatives of this age were children, or {{lang|la|pueri}}. Others aligned themselves to this idea. ] and other ] self described themselves as {{lang|la|ordo parvulorum}}, literally 'order of little ones'. Another example of this ] can be seen in elements of the '']'', an apocalyptic mythic history that incorporated descriptions of the Children's Crusade. Innocent III built on this in 1213 announcing the end of Islam in the calls for the ] by announcing that the days of were over.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|pp=24–26}} | |||

| The crusading movement found that creating a single accepted ideology and an understanding of that ideology was a practical challenge. This was because the church did not have the necessary bureaucratic systems to consolidate thinking across the papacy, the monastic orders, ] friars, and the developing universities.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=20}} Ideas were transmitted through inclusion in literary works that included romances, travelogues like '']'', poems such as ] and ]'s '']'', and works by ].{{sfn|Madden|2013|p=155}}{{sfn|Housley|2002|p=29}}{{sfn|Mannion|2014|p=21}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=330}} At this point in time the ideas of nationalism were largely absent. A more atomized society meant that literature tended to rather praise individual deeds of heroes like ] and the actions of major families.{{sfn|Richard|2005|p=207}} Innocent III developed new practices and revised the ideology of crusading from 1198 when he became pope. This included a new executive office constituted for the organization of the Fourth Crusade. Executives were appointed in each church province in addition to autonomous preaching by the like of ]. This led to papal sanctioned provincial administrations and the codification of preaching. Local church authorities were required to report to these administrators on crusading policy. Propaganda was now more coherent despite an occasionally ad-hoc implementation.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=46}} Funding was increased through the introduction of ] and greater donations.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=235–237}}{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=524–525}} He was also the first pope to deploy the apparatus of crusading against his fellow Christians.{{sfn|Asbridge|2012|pp=533–535}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=238–239}} This innovation became a frequent approach by the papacy that was used against those it considered ], heretics, or ]atics.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=336}} | |||

| ====Popular crusading==== | |||

| ==== Popular crusading ==== | |||

| Academic views on the breadth of the crusading movement are varied. Riley-Smith excludes popular crusades by definition, while Gary Dickson has produced in depth research.{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|p=223}} The 1212 Children's Crusade was the inaugural independent popular crusade. This began a tradition of outbreaks of ] that lasted until the 1514 ]. The children's crusade was prompted by preaching for the Albigensian Crusade and processions seeking divine intervention for the Iberian crusades. Crusades such as these were considered illegitimate because they were unauthorised by the Church and lacked papal endorsement. The participants were also unconventional crusaders.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=258-260}} Little evidence remains for what these poor crusaders thought or felt.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|pp=66-67}} Although rare sources cast doubt on whether these poor crusaders were in fact poor. The anonymous author of the ] included what they claimed was a verbatim lyric of the marching song of children on the march to the East. This offers one evidential window into their eschatological beliefs.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|p=14}} The church could not understand poor secular leaders like ] who used ] when recruiting large followings.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|p=101-102}} | |||

| {{further|Popular crusades}} | |||

| In 1212, an outbreak of popular crusading occurred that is now known as the Children's Crusade. This was the first of a number of similar events which lasted until the ] in 1514. What these all had in common was that they were independent of the church. The first seems to have been a response to the preaching of the Albigensian Crusade and also religious processions seeking God's support for the fighting in Iberia. The church considered such outbreaks by rather unconventional crusaders as unauthorized and therefore illegitimate.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=258–260}} There is little remaining evidence for the identities, thoughts and feelings of those who took part.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995b|pp=66-67}} One unaccredited piece is the ]. This includes allegedly verbatim lyrics of the marching song of children heading east and offers evidence of eschatological beliefs.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|p=14}} The church was unable to comprehend the charisma of impoverished non-priestly leaders like ] and how this could be used in recruiting such large followings.{{sfn|Dickson|2008|p=101–102}} Modern academic opinion is split on the definition of a crusade. Riley-Smith disregards these popular uprisings as not meeting the criteria, while Gary Dickson has produced in depth research.{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|p=223}} | |||

| His research challenges traditional interpretations of the crusades by focusing on the social and religious dimensions of popular participation, particularly in the "Children's Crusade" of 1212. He demonstrates that the term pueri referred to youths or individuals of low social status, and that this movement was not solely composed of children but included marginalized groups like shepherds and agricultural workers. Dickson's work interprets the "Children's Crusade" as a form of social critique driven by a desire to return to apostolic simplicity and dissatisfaction with societal leaders. Additionally, his examination of the early 19th-century historiography of the crusades highlights a tendency to view them through a lens of materialism and romanticism. His research also emphasizes the importance of including popular crusades and unsanctioned outbreaks in the broader study of the crusading movement, arguing that rigid definitions can obscure the complexity and variety of the phenomenon. He notes that historians have "reinvented" or reinterpreted the crusades throughout history.{{sfn|Housley|2006|pp=1,6,9,33}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2011|p=223, 227, 241}} | |||

| ====Early century==== | |||

| ==== Early century ==== | |||

| Cardinal ] of Segni led teams of preachers in ] and northern Italy between 1217 and 1221. He played a part in loosening the church funding and crusade recruitment rules by using five percent income tax on the Church known as the "clerical twentieth" to pay for the mercenaries who joined the Fifth Crusade and for grants to {{lang|la|crucesignati}}.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=620}} He took the name Pope Gregory IX when elected pope in 1227.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=648}} In 1239 Gregory IX excommunicated Frederick II when the emperor attempted to expand into papal territory. In 1241 Frederick threatened Rome, so Gregory deployed the crusading tools of indulgences, privileges, and taxes against him.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=351-352}}{{sfn|Jotischky|2004|p=211}}. | |||

| In the years between 1217 and 1221 Cardinal ] of Segni led preaching campaigns and helped relax controls on funding and recruitment. He used the five per cent income tax on the church known as the "clerical twentieth" to pay mercenaries in the Fifth Crusade and other {{lang|la|crucesignati}}.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=620}} In 1227, Hugo became pope and adopted the name Gregory IX.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=648}} He clashed with Frederick II over territory in Italy, excommunicating him in 1239 and deploying the crusading tools of indulgences, privileges, and taxes in 1241.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=351-352}}{{sfn|Jotischky|2004|p=211}} The Christian right to land ownership was foundational to crusading ideology, although ] acknowledged Muslim rights he considered these only existed under the authority of Christ.{{sfn|Jotischky|2004|pp=256–257}} ] continued the policies of both Gregory IX and Innocent IV from his ascension in 1254 which led to further crusading against the Hohenstaufen dynasty.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=352}} | |||

| ] agreed with Muslims land ownership but in his view this was only under the authority of Christ. The Christians' right to ownership was foundational to crusading ideology. {{sfn|Jotischky|2004|pp=256–257}} ] continued the policies of Gregory IX and Innocent IV after he succeeded to the papacy in 1254. In practice this led to crusading against the Hohenstaufen dynasty.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=352}} In the face of a significant low point of the movement in 1274, the ] began the gathering of ideas to improve crusading organisation and finance. This demonstrated the resilience that would enable the movement's continuing existence.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=260}} | |||

| ====Criticism==== | ==== Criticism ==== | ||

| {{Main|criticism of crusading}} | |||

| Early ] and the conduct of crusaders is evident. While the concept itself was seldom questioned in the 12th and 13th centuries, there were vigorous objections to crusades targeting heretics and Christian secular powers. The assault on Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade and the diversion of resources against Church enemies in Europe, such as the Albigensian heretics and the Hohenstaufen, drew condemnation. Troubadours in southern France expressed discontent with expeditions, lamenting the neglect of the Holy Land. The behavior of participants was seen as falling short of the expectations of a holy war, with chroniclers and preachers decrying instances of sexual immorality, greed, and arrogance. Western Europeans attributed failures and setbacks, such as those during the First Crusade and the defeat of the kingdom of Jerusalem at Hattin by Saladin, to human frailty. Gerhoh of Reichersberg linked the shortcomings of the Second Crusade to the arrival of the Antichrist and accused the movement of fostering increased puritanism.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=247}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=28}} | |||

| During the 12th and 13th{{nbsp}}centuries, the concepts behind the crusading movement were rarely questioned, but there is evidence that practice was criticized. Events such as crusades against non-conforming Christians, the sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade, crusading against the German Hohenstaufen dynasty and the southern French Albigensian all drew condemnation. Questions were raised about the objectives of these and whether they were a distraction from the primary cause of fighting for the Holy Land. In particular, ] Troubadours expressed discontent with expeditions in their southern French homeland. Additionally, reports of sexual immorality, greed, and arrogance exhibited by crusaders was viewed as incompatible with the ideals of a holy war. This gave commentators excuses or reasons for failures and setbacks in what was otherwise considered God's work. In this was defeats experienced such as during the First Crusade, by Saladin at Hattin and the defeat of ] at the ] in 1250 could be explained. Some, such as Gerhoh of Reichersberg, linked this to the expected coming of the Antichrist and increased puritanism. {{sfn|Tyerman|2006|p=247}}{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=28}} This puritanism was the church's response to criticism, and included processions and reforms such as gambling bans and restrictions on women. Primary sources include the ''Würzburg Annals'' and Humbert of Romans's work ''De praedicatione crucis'' which translates as ''concerning the preaching of the cross''. Crusaders were thought to have fallen under satanic influence and doubts were raised about forcible conversion.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|p=314}} | |||

| In response to criticism, the movement implemented ceremonial processions, calls for reform, bans on gambling and extravagance, and restrictions on the participation of women. The ''Würzburg Annals'' condemned the conduct of the crusaders, attributing it to diabolical influence. The defeat of ] at the ] in 1250 triggered debates on crusading in sermons and writings, including Humbert of Romans's work ''De praedicatione crucis''—concerning the preaching of the cross. Humbert raised doubts about the method of forcible conversion.{{sfn|Tyerman|2006c|p=314}} | |||

| ==== Latter century ==== | |||

| The expense of maintaining armies resulted in taxation, a notion vehemently opposed by ], ], and ]. Critics expressed apprehensions regarding Franciscan and Dominican friars exploiting the vow redemption system for monetary benefits. While the peaceful conversion of Muslims was considered a possibility, there is no indication that it reflected the prevailing public sentiment, as the ongoing crusades suggest otherwise.{{sfn|Siberry|2006|pp=299–301}} | |||

| The movement continued developing innovative organisational financial methods. However, in 1274 it faced a significant low.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=260}} In response the ] initiated the search for new ideas. The response to which showed a resilience that would enable the continuation of the movement.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=260}} This was not without opposition. Matthew Paris in ''{{lang|la|]}}'' and Richard of Mapham, the ] both raised noteworthy concerns and the Teutonic Order for one, among others of the military orders were criticized for arrogance, greed, using their great wealth to pay for luxurious lifestyles, and an inadequate response in the Holy Land. Collaboration was difficult because of open conflict between the Templars and Hospitallers and among Christians in the Baltic. The autonomy of the orders was viewed in the church as leading to a loss of effectiveness in the East and overly friendlt relations with Muslims. A minority within the church including ] made the case that aggression in areas like the Baltic actually hindered conversion.{{sfn|Forey|1995|p=211}} ] developed the objective of reunification with the Greek church as an essential prerequisite for further crusades.{{sfn|Tyerman|2019|pp=399-401}} In planning the funding of this crusade he created a complex tax gathering regime by Latin Christendom into twenty-six collectorates, each directed by a general collector. In order to tackle fraud each collector would further delegate tax liability assessment. This system raised vast amounts which in turn prompted further clerical criticism of obligatory taxation.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=57}} | |||

| ====Later century==== | |||

| === 14th century === | |||

| The triumph of the Egyptian ] in the Holy Land plunged the crusading movement into turmoil. Despite successes in Spain, ], and Italy, the loss of the Holy Land remained irreparable. This crisis encompassed both a crisis of faith and military strategy, deemed religiously disgraceful by the ].{{sfn|MacEvitt|2006c}} | |||

| ]}}'', in a French translation by ], from a manuscript of the 1330s]] | |||

| Prominent critics such as Matthew Paris in ''{{lang|la|]}}'' and Richard of Mapham, the ], voiced notable concerns at the council. The military orders, especially the Teutonic Order, faced censure for their arrogance, greed, luxurious lifestyles funded by their wealth, and inadequate deployment of forces in the Holy Land. Internal conflicts between the Templars and Hospitallers, as well as among Christians in the Baltic, hindered collaborative efforts. The Church perceived military actions in the East as less effective due to the independence of these orders and their perceived reluctance to engage in combat with Muslims, with whom critics believed they maintained overly cordial relations. A minority perspective, advocated by ] and others, argued that aggressive actions, particularly in the Baltic, impeded the conversion efforts.{{sfn|Forey|1995|p=211}} | |||

| {{Main|Teutonic Order|Holy League}} | |||

| The movement continued to exhibit traits of innovation, commitment, resilience, and flexibility by consolidating methods of organisation and finance, which facilitated its survival.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=260}} General opinion did not consider the loss of the Holy Land as final, only later when the ] began in 1337 did hopes for recovery fade.{{sfn|MacEvitt|2006c}} One of ]'s objectives was the reunification of the Latin and Greek churches, which he viewed as essential for a new crusade. At the Second Council of Lyon, he demanded the Eastern Orthodox delegation accept all Latin teaching. In return, Gregory offered a reversal of papal support for ], the king of Sicily, to meet the Byzantines' primary motivation of the cessation of Western attacks. However, there was little interest from European monarchs, who were focussed on their own conflicts.{{sfn|MacEvitt|2006c}} Gregory created a complex tax gathering system for the funding of crusading, dividing Latin Christendom in 1274 into twenty-six collectorates. Each of these was under the direction of a general collector who further delegated the assessment of tax liability to reduce fraud. The vast amounts raised by this system led to clerical criticism of obligatory taxation.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=57}} | |||

| The 14th{{nbsp}}century saw further outbreaks of popular and unsanctioned crusading enthusiasm. These were often prompted by major events such as the Mongol victory at the ]. At the grassroots movements in France and Germany continued.{{sfn|Housley|1995|pp=262–265}} The ] recruited crusaders in Prussia and ]. This was without authorization from the church, but the order utilized privileges granted half a century earlier by Innocent IV. The campaigns known as journeys or {{lang|de|Reisen}} were popular and attracted knights from across the Catholic states of Europe. In this way they became a chivalric cult.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=275}} Following the tradition started by Innocent III, popes requested advice on strategies that could be implemented in the recovery of the Holy Land. Over twenty example papers remain from the period that is book-ended by the 1274 council of Lyon and the 1314 council of Vienna. The movement continued ] with developments for the intended funding of professional armies, including a six-year tithe on clerical incomes. However, the politics of the ] and ] prevented progress. Egypt was not blockaded and no new foothold was established in the East.{{sfn|Housley|1995|pp=262–265}} | |||

| ===14th century=== | |||

| In 1132 a new approach and crusading institution was devised. This was a ], the first of several temporary alliances between the church and other Christian polities. In 1344, the ] successfully captured Smyrni. The precedent was later followed successfully in the 1571 ] and in the late 17th{{nbsp}}century for the recovery of territory in the ].{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=4}} Italy experienced a state of political anarchy. As a result, the church granted crusade indulgences to anyone who could be recruited to fight against the threat presented by ] and for the popes and the papacy that was now based in ]. In 1378 the papacy was divided in what is known as the ]. The rival popes called for crusades against each other.{{Clarification needed|reason=This is moving much too fast: where did these rival popes come from? Who were they? How did all this happen?|date=January 2025}} Eventually the movement and the papacy united in the face of the growing threat of the ].{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=270}} By the end of the century, the {{lang|de|Reisen}} was obsolete and the only contact that common people had with the movement was the preaching of the indulgence. While the success or failure of propaganda varied in extent, local attitude and capability, there is no evidence that it was popular apathy or hostility that caused of the mobilization failure of large scale crusading against the Turks.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=281}} | |||

| ]'', in a French translation by ], from a manuscript of the 1330s]] | |||

| === 15th and 16th centuries === | |||

| Between the councils of Lyon in 1274 and Vienna in 1314, there existed over twenty treatises concerning the recovery of the Holy Land. These were instigated by Popes who, following the lead of Innocent III, sought counsel on the matter. This led to unfulfilled strategies for the blockading Egypt and possible expeditions to establish a foothold that would pave the way for full-scale crusades with professional armies. Discussions among writers often revolved around the intricacies of ] and ] dynastic politics. Periodic bursts of popular crusading occurred throughout the decades, spurred by events like the Mongol victory at ] and grassroots movements in France and Germany. Despite numerous obstacles, the papacy's establishment of taxation, including a six-year tithe on clerical incomes, to fund contracted professional crusading armies, represented a remarkable feat of institutionalisation.{{sfn|Housley|1995|pp=262–265}} The 1320 {{lang|la|pastores}} of the ] was the first time that the papacy decried a popular crusade.{{sfn|Dickson|2006|pp=975–979}} | |||

| Beginning in 1304 and lasting the entire 14th{{nbsp}}century, the ] used the privileges Innocent IV had granted in 1245 to recruit crusaders in Prussia and ], in the absence of any formal crusade authority. Knightly volunteers from every Catholic state in western Europe flocked to take part in campaigns known as {{lang|de|Reisen}}, or journeys, as part of a chivalric cult.{{sfn|Housley|1995|p=275}} Commencing in 1332, the numerous ]s in the form of temporary alliances between interested Christian powers, were a new manifestation of the movement. Successful campaigns included the ] in 1344, the ] in 1571, and the recovery of territory in the ] between 1684 and 1697.{{sfn|Riley-Smith|1995|p=4}} | |||