| Revision as of 05:36, 20 November 2024 view sourceRemsense (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Template editors63,787 edits Undid revision 1258524069 by Akravus (talk): as it wasTag: Undo← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:12, 21 January 2025 view source Matarisvan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions3,059 edits Added Lazaris 2008 to biblio which I had forgotten, incorporated some of Laiou 2002Tag: Visual edit: Switched | ||

| (230 intermediate revisions by 26 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Continuation of the Roman Empire}} | {{Short description|Continuation of the Roman Empire (330–1453)}} | ||

| {{Redirect|Byzantine}} | {{Redirect|Byzantine}} | ||

| {{ |

{{protection padlock|small=yes}} | ||

| {{Featured article}} | {{Featured article}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2023}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2023}} | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

| {{end plainlist}} | {{end plainlist}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Byzantine Empire''', also referred to as the '''Eastern Roman Empire''', was the continuation of the ] centred in ] during ] and the ]. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the ] in the 5th century |

The '''Byzantine Empire''', also referred to as the '''Eastern Roman Empire''', was the continuation of the ] centred in ] during ] and the ]. The eastern half of the Empire survived the conditions that caused the ] in the 5th century{{Nbsp}}AD, and continued to exist until the ] to the ] in 1453. During most of its existence, the empire remained the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in the ]. The term "Byzantine Empire" was only coined following the empire's demise; its citizens referred to the polity as the "Roman Empire" and to themselves as "Romans".{{Efn|{{Langx|grc-x-medieval|Ῥωμαῖοι|Rhōmaîoi}}}} Due to the imperial seat's move from Rome to ], the ], and the predominance of ] instead of ], modern historians continue to make a distinction between the earlier ''Roman Empire'' and the later ''Byzantine Empire''. | ||

| During the earlier ] period, the western parts of the empire became ], while the eastern parts largely retained their preexisting ]. This created a dichotomy between the ]. These cultural spheres continued to diverge after ] ({{Reign|324|337}}) moved the capital to Constantinople and legalised ]. Under ] ({{Reign|379|395|lk=no}}), Christianity became the ], and other religious practices ]. Greek gradually replaced Latin for official use as Latin fell into disuse. | During the earlier ] period, the western parts of the empire became ], while the eastern parts largely retained their preexisting ]. This created a dichotomy between the ]. These cultural spheres continued to diverge after ] ({{Reign|324|337}}) moved the capital to Constantinople and legalised ]. Under ] ({{Reign|379|395|lk=no}}), Christianity became the ], and other religious practices ]. Greek gradually replaced Latin for official use as Latin fell into disuse. | ||

| The empire experienced several cycles of decline and recovery throughout its history, reaching its greatest extent after the fall of the west during the reign of ] ({{Reign|527|565|lk=no}}), who briefly reconquered much of Italy and the western ]. The ] and a ] exhausted the empire's resources; the ] that followed saw the loss of the empire's richest provinces—] and ]—to the ]. In 698, Africa ] to the ], but the empire subsequently stabilised under the ] dynasty. The empire was able to expand once more under the ], experiencing ]. This came to an end in 1071 |

The empire experienced several cycles of decline and recovery throughout its history, reaching its greatest extent after the fall of the west during the reign of ] ({{Reign|527|565|lk=no}}), who briefly reconquered much of Italy and the western ]. The ] and a ] exhausted the empire's resources; the ] that followed saw the loss of the empire's richest provinces—] and ]—to the ]. In 698, Africa ] to the ], but the empire subsequently stabilised under the ] dynasty. The empire was able to expand once more under the ], experiencing ]. This growth came to an end in 1071 after the defeat by the ] at the ]. Thereafter, periods of civil war and Seljuk incursion resulted in the loss of most of ]. The empire recovered during the ], and Constantinople remained the largest and wealthiest city in Europe until the 13th century. | ||

| The empire was largely dismantled in 1204, following the ] by Latin armies at the end of the ]; its former territories ] into competing Greek ]s and ]. Despite the eventual ] in 1261, the reconstituted empire |

The empire was largely dismantled in 1204, following the ] by Latin armies at the end of the ]; its former territories ] into competing Greek ]s and ]. Despite the eventual ] in 1261, the reconstituted empire wielded only regional power during its final two centuries of existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans in ] fought throughout the 14th and 15th centuries. The ] to the Ottomans in 1453 ultimately brought the empire to an end. Many refugees who had fled the city after its capture settled in Italy and throughout Europe, helping to ignite the ]. The fall of Constantinople is sometimes used to mark the dividing line between the Middle Ages and the ]. | ||

| == Nomenclature == | == Nomenclature == | ||

| {{See also |

{{See also|Names of the Greeks}} | ||

| The inhabitants of the empire, now generally termed Byzantines, thought of themselves as ] ({{transliteration|grc|Romaioi}}). Their Islamic neighbours similarly called their empire the "land of the Romans" ({{transliteration|ar|Bilād al-Rūm}}), but the people of medieval Western Europe preferred to call them "Greeks" (''Graeci''), due to having a contested legacy to Roman identity and to associate negative connotations from ancient Latin literature.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=2|2a1=Aschenbrenner|2a2=Ransohoff|2y=2022|2pp=1–2|Cormack|2008|3pp=8–9}} The adjective "Byzantine", which derived from ] (Latinised as {{lang|la|Byzantium}}), the name of the Greek settlement ] was established on, was only used to describe the inhabitants of that city; it did not refer to the empire, which they called {{transliteration|grc|Romanía}}—"Romanland".{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2022|1pp=349–351|Cormack|2008|2p=4}} | |||

| The inhabitants of the empire, now generally termed ], thought of themselves as ] ({{transliteration|grc|Romaioi}}). Their Islamic neighbours similarly called their empire the "land of the Romans" ({{transliteration|ar|Bilād al-Rūm}}), but the people of medieval Western Europe preferred to call them "Greeks" ({{lang|la|Graeci}}), due to having a contested legacy to Roman identity and to associate negative connotations from ancient Latin literature.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=2|2a1=Aschenbrenner|2a2=Ransohoff|2y=2022a|2pp=1–2|3a1=Cormack|3a2=Haldon| 3a3=Jeffreys|3y=2008|3pp=8–9}} The adjective "Byzantine", which derived from ] (Latinised as {{lang|la|Byzantium}}), the name of the Greek settlement ] was established on, was only used to describe the inhabitants of that city; it did not refer to the empire, which they called {{transliteration|grc|Romanía}}—"Romanland".{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2022|1pp=349–351|2a1=Cormack |2a2=Haldon|2a3=Jeffreys|2y=2008|2p=4}} | |||

| After the empire's fall, early modern scholars referred to the empire by many names, including the "Empire of Constantinople", the "Empire of the Greeks", the "Eastern Empire", the "Late Empire", the "Low Empire", and the "Roman Empire".{{sfn|Aschenbrenner|Ransohoff|2022|p=2}} The increasing use of "Byzantine" and "Byzantine Empire" likely started with the 15th-century historian ], whose works were widely propagated, including by ]. "Byzantine" was used adjectivally alongside terms such as "Empire of the Greeks" until the 19th century.{{sfn|Kaldellis|2022|pp=352–357}} It is now the primary term, used to refer to all aspects of the empire; some modern historians believe that, as an originally prejudicial and inaccurate term, it should not be used.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=2–3|Cormack|2008|2p=4}} | |||

| After the empire's fall, ] scholars referred to the empire by many names, including the "Empire of Constantinople", the "Empire of the Greeks", the "Eastern Empire", the "Late Empire", the "Low Empire", and the "Roman Empire".{{sfn|Aschenbrenner|Ransohoff|2022a|p=2}} The increasing use of "Byzantine" and "Byzantine Empire" likely started with the 15th-century historian ], whose works were widely propagated, notably by ]. "Byzantine" was used adjectivally alongside terms such as "Empire of the Greeks" until the 19th century.{{sfn|Kaldellis|2022|pp=352–357}} It is now the primary term, used to refer to all aspects of the empire; however, some modern historians believe that, as an originally prejudicial and inaccurate term, it should not be used.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=2–3|2a1=Cormack|2a2=Haldon|2a3=Jeffreys|2y=2008|2p=4}} | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| Line 86: | Line 87: | ||

| {{further|Byzantine Empire under the Constantinian and Valentinianic dynasties|Byzantine Empire under the Theodosian dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Leonid dynasty}} | {{further|Byzantine Empire under the Constantinian and Valentinianic dynasties|Byzantine Empire under the Theodosian dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Leonid dynasty}} | ||

| ] under the ] system established by ].|alt=A map showing the division of the Roman empire {{circa|300}}]] | ] under the ] system established by ].|alt=A map showing the division of the Roman empire {{circa|300}}]] | ||

| In a series of conflicts between the third and first centuries{{Nbsp}}BC, the ] gradually established hegemony over the ], while ] ultimately transformed into the one-person rule of ]. The ] enjoyed a period of ] until ], when a combination of external threats and internal instabilities caused the Roman state to splinter as regional armies acclaimed their generals as "soldier-emperors".{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=233|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=16–17|Treadgold|1997|3pp=4–7}} One of these, ] ({{reign|284|305}}), seeing that the state was too big to be ruled by one man, attempted to fix the problem by instituting a ], or rule of four, and dividing the empire into eastern and western halves. Although the Tetrarchy system quickly failed, the division of the empire proved an enduring concept.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=233–235|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=17–18|Treadgold|1997|3pp=14–18}} | In a series of conflicts between the third and first centuries{{Nbsp}}BC, the ] gradually established hegemony over the ], while ] ultimately transformed into the one-person rule of ]. The ] enjoyed a period of ] until ], when a combination of external threats and internal instabilities caused the Roman state to splinter as regional armies acclaimed their generals as "soldier-emperors".{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=233|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=16–17|Treadgold|1997|3pp=4–7}} One of these, ] ({{reign|284|305}}), seeing that the state was too big to be ruled by one man, attempted to fix the problem by instituting a ], or rule of four, and dividing the empire into eastern and western halves. Although the Tetrarchy system quickly failed, the division of the empire proved an enduring concept.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=233–235|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=17–18|Treadgold|1997|3pp=14–18}} | ||

| ] ({{reign|306|337}}) secured sole power in 324. Over the following six years, he rebuilt the city of ] as a ], which was renamed ]. |

]'s reforms significantly altered governmental structure, reach and taxation, and these reforms also had the effect of downgrading the first capital, ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=20-21, 34|Treadgold|1997|2pp=39, 45, 85|Rotman|2022|3pp=41–43|Greatrex|2008|3p=234–235}} ] ({{reign|306|337}}) secured sole power in 324. Over the following six years, he rebuilt the city of ] as a ], which was renamed ]. Rome was further from the important eastern provinces and in a less strategically important location; it was not esteemed by the "soldier-emperors" who ruled from the frontiers or by the empire's population who, ], considered themselves "Roman".{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=335|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=16–20|Treadgold|1997|3pp=39–40}} Constantine extensively reformed the empire's military and civil administration and instituted the ] as a stable currency.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=335–337|Kaldellis|2023|2loc=chapter 2|Treadgold|1997|3p=40}} He favoured ], which ] in 312.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=336–337|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=81–84|Treadgold|1997|3pp=31–33, 40–47}} | ||

| Constantine's dynasty fought ] against ] and ended in 363 after the death of his son-in-law ].{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=337–338|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=92–99, 106–111|Treadgold|1997|3pp=52–62}} The short ], occupied with ], religious debates, and anti-corruption campaigns, ended in the East after the death of ] at the ] in 378.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=239–240|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=114–118, 121–123|Treadgold|1997|3pp=63–67}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| Valens's successor, ] ({{reign|379|395}}), restored political stability in the east by allowing the ] to settle in Roman territory;{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=240|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=128–129|Treadgold|1997|3p=73}} he also twice intervened in the western half, defeating the usurpers ] and ] in 388 and 394 respectively.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=241|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=129–137|Treadgold|1997|3pp=74–75}} He ], confirmed the primacy of ] over ], and established ].{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=240–241|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=126–128|Treadgold|1997|3pp=71–74}} He was the last emperor to rule both the western and eastern halves of the empire;{{sfn|Kaldellis|2023|p=136}} after his death, the West |

Valens's successor, ] ({{reign|379|395}}), restored political stability in the east by allowing the ] to settle in Roman territory;{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=240|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=128–129|Treadgold|1997|3p=73}} he also twice intervened in the western half, defeating the usurpers ] and ] in 388 and 394 respectively.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=241|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=129–137|Treadgold|1997|3pp=74–75}} He ], confirmed the primacy of ] over ], and established ].{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=240–241|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=126–128|Treadgold|1997|3pp=71–74}} He was the last emperor to rule both the western and eastern halves of the empire;{{sfn|Kaldellis|2023|p=136}} after his death, the West was destabilised by a succession of "soldier-emperors", unlike the East, where administrators continued to hold power. ] ({{reign|408|450}}) largely left the rule of the east to officials such as ], who constructed the ] to defend Constantinople, now firmly entrenched as Rome's capital.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=242|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=165–167|Treadgold|1997|3pp=87–90}} | ||

| Theodosius' reign was marked by the theological dispute over ], which was eventually deemed ], and by the formulation of the '']'' law code.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=242|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=172–178|Treadgold|1997|3pp=91–92, 96–99|Shepard|2009|4p=23}} It also saw the arrival of ]'s ], who ravaged the ] and exacted a massive ] from the empire; Attila however switched his attention to the ], and his people fractured after his death in 453.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=242–243|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=193–196, 200|Treadgold|1997|3pp=94–95, 98}} After ] ({{reign|457|474}}) failed in his ] the west, the warlord ] deposed ] in 476, killed his titular successor ] in 480, and the office of western emperor was formally abolished.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=243–244|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=209, 214–215|Treadgold|1997|3pp=153, 158–159}} | Theodosius' reign was marked by the theological dispute over ], which was eventually deemed ], and by the formulation of the '']'' law code.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=242|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=172–178|Treadgold|1997|3pp=91–92, 96–99|Shepard|2009|4p=23}} It also saw the arrival of ]'s ], who ravaged the ] and exacted a massive ] from the empire; Attila however switched his attention to the ], and his people fractured after his death in 453.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=242–243|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=193–196, 200|Treadgold|1997|3pp=94–95, 98}} After ] ({{reign|457|474}}) failed in his ] the west, the warlord ] deposed ] in 476, killed his titular successor ] in 480, and the office of western emperor was formally abolished.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1pp=243–244|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=209, 214–215|Treadgold|1997|3pp=153, 158–159}} | ||

| Through a combination of luck, cultural factors, and political decisions, the Eastern empire never suffered from rebellious barbarian vassals and was never ruled by barbarian warlords—the problems which ensured the downfall of the West.{{sfn|Kaldellis|2023|pp=243–246}} ] ({{reign|474|491}}) convinced the problematic ] king ] to take control of Italy from Odoacer, which he did; dying |

Through a combination of luck, cultural factors, and political decisions, the Eastern empire never suffered from rebellious barbarian vassals and was never ruled by barbarian warlords—the problems which ensured the downfall of the West.{{sfn|Kaldellis|2023|pp=243–246}} ] ({{reign|474|491}}) convinced the problematic ] king ] to take control of Italy from Odoacer, which he did; dying when the empire was at peace, Zeno was succeeded by ] ({{reign|491|518}}).{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=244|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=220–221|Treadgold|1997|3pp=162–164}} Although his ] brought occasional issues, Anastasius was a capable administrator and instituted several successful financial reforms including the abolition of the ]. He was the first emperor, since Diocletian, who did not face any serious problems affecting his empire.{{sfnm|Greatrex|2008|1p=244|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=223–226|Treadgold|1997|3pp=164–173}} | ||

| === 518–717 === | === 518–717 === | ||

| {{ |

{{further|Byzantine Empire under the Justinian dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Heraclian dynasty}} | ||

| {{Multiple image | {{Multiple image | ||

| | perrow = 2 | | perrow = 2 | ||

| Line 113: | Line 116: | ||

| <!--The Acacian schism should be discussed in the Religion section. Whether the renovatio imperii existed at all is not within the scope of this article.--> | <!--The Acacian schism should be discussed in the Religion section. Whether the renovatio imperii existed at all is not within the scope of this article.--> | ||

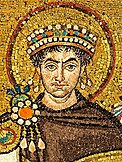

| The reign of ] was a watershed in Byzantine history.{{sfnm|Haldon| |

The reign of ] was a watershed in Byzantine history.{{sfnm|Haldon|2008a|1p=250|Louth|2009a|2p=106|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=257–258|Treadgold|1997|4p=174}} Following his accession in 527, the law-code was rewritten as the influential '']'' and Justinian produced extensive legislation on provincial administration;{{sfnm|Louth|2009a|1pp=108–109|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=269–271|Sarris|2002|3p=45|Treadgold|1997|4pp=178–180}} he reasserted imperial control over religion and morality through purges of non-Christians and "deviants";{{sfnm|Sarris|2002|1pp=43–45|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=271–274|Louth|2009a|3pp=114–119}} and having ruthlessly subdued ] he rebuilt much of Constantinople, including the original ].{{sfnm|Louth|2009a|1pp=111–114|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=274–277|Sarris|2002|3p=46}} Justinian took advantage of political instability in Italy to attempt the reconquest of lost western territories. The ] in North Africa ] by the general ], who ]; the ] was destroyed in 554.{{sfnm|Sarris|2002|1p=46|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=279–283, 287–288, 305–307|Moorhead|2009|3pp=202–209}} | ||

| In the 540s, however, Justinian began to suffer reversals on multiple fronts. Taking advantage of Constantinople's preoccupation with the West, ] of the ] invaded Byzantine territory and sacked ] in 540.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=297|Treadgold|1997|2pp=193–194|Haldon| |

In the 540s, however, Justinian began to suffer reversals on multiple fronts. Taking advantage of Constantinople's preoccupation with the West, ] of the ] invaded Byzantine territory and sacked ] in 540.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=297|Treadgold|1997|2pp=193–194|Haldon|2008a|3pp=252–253}} Meanwhile, the emperor's internal reforms and policies began to falter, not helped by ] that killed a large proportion of the population and severely weakened the empire's social and financial stability.{{sfnm|Sarris|2002|1p=49|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=298–301}} The most difficult period of the Ostrogothic war, against their king ], came during this decade, while divisions among Justinian's advisors undercut the administration's response.{{sfnm|Treadgold|1997|1pp=196–207|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=298–299, 305–306|Moorhead|2009|3pp=207–208}} He also did not fully heal the divisions in ], as the ] failed to make a real difference.{{sfnm|Treadgold|1997|1pp=210–211, 214|Louth|2009a|2pp=117–118|Haldon|2008a|3p=253}} Justinian died in 565; his reign saw more success than that of any other Byzantine emperor, yet he left his empire under massive strain.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=318–319|Treadgold|1997|2p=217|Sarris|2002|3p=51}} | ||

| Financially and territorially overextended, ] ({{reign|565|578}}) was soon at war on many fronts. The ], fearing the aggressive ], conquered much of northern Italy by 572.{{sfnm|Sarris|2002|1p=51|Haldon| |

Financially and territorially overextended, ] ({{reign|565|578}}) was soon at war on many fronts. The ], fearing the aggressive ], conquered much of northern Italy by 572.{{sfnm|Sarris|2002|1p=51|Haldon|2008a|2p=254|Treadgold|1997|3pp=220–222}} The ] that year, and continued until the emperor ] finally emerged victorious in 591; by that time, the Avars and ], causing great instability.{{sfnm|Louth|2009a|1pp=124–127|Haldon|2008a|2p=254|Sarris|2002|3p=51}} Maurice ] during the 590s, but although he managed to re-establish Byzantine control up to the ], he pushed his troops too far in 602—they mutinied, proclaimed an officer named ] as emperor, and executed Maurice.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=336–338|Treadgold|1997|2pp=232–235|Haldon|2008a|3p=254}} The Sasanians seized their moment and ]; Phocas was unable to cope and soon faced ] led by ]. Phocas lost Constantinople in 610 and was soon executed, but the destructive civil war accelerated the empire's decline.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=347–350|Haldon|2008a|2p=254|Louth|2009b|3pp=226–227|Treadgold|1997|4p=241}} | ||

| {{multiple image | {{multiple image | ||

| | align = left | | align = left | ||

| | direction = vertical | | direction = vertical | ||

| | width = |

| width = 270 | ||

| | image1 = The Sasanian Empire at its apex under Khosrow II-es.svg | | image1 = The Sasanian Empire at its apex under Khosrow II-es.svg | ||

| | alt1 = A map centred on West Asia, with the territories controlled by the Sassanian Empire colored light brown. All of modern day Iran, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Syria, Iraq, Israel, Palestine; southern Yemen, northern Arabia and Egypt along with a bulge through Turkey are colored light brown | | alt1 = A map centred on West Asia, with the territories controlled by the Sassanian Empire colored light brown. All of modern day Iran, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Syria, Iraq, Israel, Palestine; southern Yemen, northern Arabia and Egypt along with a bulge through Turkey are colored light brown | ||

| Line 130: | Line 133: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| Under ], the Sassanids occupied the ] and Egypt and pushed into Asia Minor, while Byzantine control of Italy slipped and the Avars and Slavs ran riot in the Balkans.{{sfnm|Haldon| |

Under ], the Sassanids occupied the ] and Egypt and pushed into Asia Minor, while Byzantine control of Italy slipped and the Avars and Slavs ran riot in the Balkans.{{sfnm|Haldon|2008a|1pp=254–255|Treadgold|1997|2pp=287–293|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=351–355}} Although Heraclius repelled ] in 626 and ] in 627, this was a ].{{sfnm|Sarris|2002|1pp=56–58|Haldon|2008a|2p=255|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=364–367, 369, 372|Louth|2009b|4pp=227–229|Treadgold|1997|5pp=397–400}} The ] soon saw the conquest of ], ], and ] by the newly-formed Arabic ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=375|Haldon|2008a|2p=256|Louth|2009b|3pp=229–230}} By Heraclius' death in 641, the empire had been severely reduced economically as well as territorially—the loss of the wealthy eastern provinces had deprived Constantinople of three-quarters of its revenue.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=387|Haldon|2008a|2p=256|Treadgold|2002|3p=129}} | ||

| The next seventy-five years are poorly documented.{{sfn|Kaldellis|2023|p=387}} ] began almost immediately, and the Byzantines resorted to holding fortified centres and avoiding battle at all costs; although it was invaded annually, Anatolia avoided permanent Arab occupation.{{sfnm|Haldon| |

The next seventy-five years are poorly documented.{{sfn|Kaldellis|2023|p=387}} ] began almost immediately, and the Byzantines resorted to holding fortified centres and avoiding battle at all costs; although it was invaded annually, Anatolia avoided permanent Arab occupation.{{sfnm|Haldon|2008a|1p=257|Kaldellis|2023|2p=387}} The outbreak of the ] in 656 gave Byzantium breathing space, which it used wisely: some order was restored in the Balkans by ] ({{reign|641|668}}),{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=389|Louth|2009b|2pp=230–231}} who began the administrative reorganisation known as the "]", in which troops were allocated to defend specific provinces.{{sfnm|Treadgold|1997|1pp=315–316|Louth|2009b|2pp=239–240}} With the help of the recently rediscovered ], ] ({{reign|668|685}}) repelled the Arab efforts to ],{{sfnm|Treadgold|1997|1pp=323–327|Haldon|2008a|2p=257|Louth|2009b|3pp=232–233}} but suffered ] against the ], who soon established ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=403|Haldon|2008a|2pp=257–258|Treadgold|2002|3pp=134–135}} Nevertheless, he and Constans had done enough to secure the empire's position, especially as the ] was undergoing ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=403|Treadgold|2002|2p=135}} | ||

| ] sought to build on the stability secured by his father Constantine but was overthrown in 695 after attempting to exact too much from his subjects; over the next twenty-two years, six more rebellions followed in ].{{sfnm|Treadgold|2002|1pp=136–138|Haldon| |

] sought to build on the stability secured by his father Constantine but was overthrown in 695 after attempting to exact too much from his subjects; over the next twenty-two years, six more rebellions followed in ].{{sfnm|Treadgold|2002|1pp=136–138|Haldon|2008a|2p=257|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=438–440}} The reconstituted caliphate sought to break Byzantium by taking Constantinople, but the newly crowned ] managed to ], the first major setback of the Muslim conquests.{{sfnm|Treadgold|2002|1pp=137–138|Haldon|2008a|2p=257|Auzépy|2009|3p=265}} | ||

| === 718–867 === | === 718–867 === | ||

| {{ |

{{further|Byzantine Empire under the Isaurian dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Nikephorian dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Amorian dynasty}}] (left), and his son and heir, ] (right)|alt=Two gold coins, each depicting a man]] | ||

| Leo and his son ] ({{reign|741|775}}), two of the most capable Byzantine emperors, withstood continued Arab attacks, civil unrest, and natural disasters, and reestablished the state as a major regional power.{{sfnm|Haldon| |

Leo and his son ] ({{reign|741|775}}), two of the most capable Byzantine emperors, withstood continued Arab attacks, civil unrest, and natural disasters, and reestablished the state as a major regional power.{{sfnm|Haldon|2008a|1pp=258–259|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=443, 451–452|Auzépy|2009|3pp=255–260}} Leo's reign produced the '']'', a new code of law to succeed that of Justinian II,{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=444–445|Auzépy|2009|2pp=275–276}} and continued to reform the "theme system" in order to lead offensive campaigns against the Muslims, culminating in ].{{sfnm|Auzépy|2009|1pp=265–273|Kaegi|2009|2pp=385–385|Kaldellis|2023|3p=450}} Constantine overcame an early civil war against his brother-in-law ], made peace with the new ], ] against the Bulgars, and continued to make administrative and military reforms.{{sfnm|Haldon|2008a|1p=260|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=450–454|Treadgold|2002|3pp=140–141}} However, due to both emperors' support for the ], which opposed the use of ], they were later vilified by Byzantine historians;{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=443, 447–449, 454–459|Haldon|2008a|2pp=258–261|Auzépy|2009|3pp=253–254}} Constantine's reign also saw the loss of ] to the ], and the beginning of a split with the ].{{sfnm|Treadgold|2002|1pp=140–141|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=459–561|Auzépy|2009|3pp=284–287}} | ||

| In 780, Empress ] assumed power on behalf of her son ].{{sfnm|Haldon|2008|1p=261|Treadgold|2002|2pp=141–142|Magdalino|2002|3p=170}} Although she was a capable administrator who temporarily resolved the iconoclasm controversy,{{sfnm|Haldon|2008|1p=261|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=464–469}} the empire was destabilized by her feud with her son. The Bulgars and Abbasids meanwhile inflicted numerous defeats on the Byzantine armies, and the papacy crowned ] as Roman emperor in 800.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=470–473|Magdalino|2002|2pp=169–171|Haldon|2008|3p=261}} In 802, the unpopular Irene was overthrown by ]; he reformed the empire's administration but died ] in 811.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=473–474, 478–481}} Military defeats and societal disorder, especially the resurgence of iconoclasm, characterised the next eighteen years.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=265|Auzépy|2009|2pp=257, 259, 289|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=482–483, 485–491}} | |||

| In 780, Empress ] assumed power on behalf of her son ].{{sfnm|Haldon|2008a|1p=261|Treadgold|2002|2pp=141–142|Magdalino|2002|3p=170}} Although she was a capable administrator who temporarily resolved the iconoclasm controversy,{{sfnm|Haldon|2008a|1p=261|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=464–469}} the empire was destabilized by her feud with her son. The Bulgars and Abbasids meanwhile inflicted numerous defeats on the Byzantine armies, and the papacy crowned ] as Roman emperor in 800.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=470–473|Magdalino|2002|2pp=169–171|Haldon|2008a|3p=261}} In 802, the unpopular Irene was overthrown by ]; he reformed the empire's administration but died ] in 811.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=473–474, 478–481}} Military defeats and societal disorder, especially the resurgence of iconoclasm, characterised the next eighteen years.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=265|Auzépy|2009|2pp=257, 259, 289|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=482–483, 485–491}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Stability was somewhat restored during the reign of ] ({{reign|829|842}}), who exploited economic growth to complete construction programs, including rebuilding the ], overhaul provincial governance, and wage inconclusive campaigns against the Abbasids.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=491–495|Holmes|2008|2p=265|Auzépy|2009|3pp=273–274}} After his death, his empress ], ruling on behalf of her son ], permanently extinguished the iconoclastic movement;{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=498–501|Holmes|2008|2p=266}} the empire prospered under their sometimes-fraught rule. However, Michael was posthumously vilified by historians loyal to the dynasty of his successor ], who assassinated him in 867 and who was given credit for his predecessor's achievements.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1pp=265–266|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=504–505|Auzépy|2009|3p=254|Tougher|2009|4pp=292–293, 296}} | Stability was somewhat restored during the reign of ] ({{reign|829|842}}), who exploited economic growth to complete construction programs, including rebuilding the ], overhaul provincial governance, and wage inconclusive campaigns against the Abbasids.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=491–495|Holmes|2008|2p=265|Auzépy|2009|3pp=273–274}} After his death, his empress ], ruling on behalf of her son ], permanently extinguished the iconoclastic movement;{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=498–501|Holmes|2008|2p=266}} the empire prospered under their sometimes-fraught rule. However, Michael was posthumously vilified by historians loyal to the dynasty of his successor ], who assassinated him in 867 and who was given credit for his predecessor's achievements.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1pp=265–266|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=504–505|Auzépy|2009|3p=254|Tougher|2009|4pp=292–293, 296}} | ||

| === 867–1081 === | === 867–1081 === | ||

| {{further|Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Doukas dynasty}} | {{further|Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Doukas dynasty}} | ||

| Basil I ({{reign|867|886}}) continued Michael's policies.{{sfnm|Tougher|2009|1pp=292, 296|Holmes|2008|2p=266}} His armies campaigned with mixed results in Italy but ] the ].{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=266|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=522–524|Treadgold|1997|3pp=455–458}} His successor ] ({{reign|886|912}}){{efn|Leo VI was officially the son of Basil I, but a persistent rumour alleged that he had been fathered by Michael III, who had previously taken Leo's mother ] as his mistress. One of Leo's first acts was to rebury Michael III in Basil's mausoleum in the ] complex, which exacerbated the rumours.{{sfnm|Tougher|2009|1p=296|Kaldellis|2023|2p=526}}}} compiled and propagated a huge number of written works. These included the '']'', a Greek translation of Justinian I's law-code which included over 100 new laws created by Leo; the '']'', a military treatise; and the '']'', which codified Constantinople's trading regulations.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=493, 496–498|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=429–433|Holmes|2008|3p=267}} In non-literary contexts Leo was less successful: the empire ] and ],{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=267|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=534–535}} while he provoked theological scandal by marrying four times in an attempt to father a legitimate heir.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=537–539|Holmes|2008|2p=267|Shepard|2009b|3p=503}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Basil I ({{reign|867|886}}) continued Michael's policies.{{sfnm|Tougher|2009|1pp=292, 296|Holmes|2008|2p=266}} His armies campaigned with mixed results in Italy but ] the ].{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=266|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=522–524|Treadgold|1997|3pp=455–458}} His successor ] ({{reign|886|912}}){{efn|Leo VI was officially the son of Basil I, but a persistent rumour alleged that he had been fathered by Michael III, who had previously taken Leo's mother ] as his mistress. One of Leo's first acts was to rebury Michael III in Basil's mausoleum, which exacerbated the rumours.{{sfnm|Tougher|2009|1p=296|Kaldellis|2023|2p=526}}}} compiled and propagated a huge number of written works. These included the '']'', a Greek translation of Justinian I's law-code which included over 100 new laws of Leo's devising; the '']'', a military treatise; and the '']'', which codified Constantinople's trading regulations.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=493, 496–498|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=429–433|Holmes|2008|2p=267}} In non-literary contexts Leo was less successful: the empire ] and ],{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=267|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=534–535}} while he provoked theological scandal by marrying four times in an attempt to father a legitimate heir.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=537–539|Holmes|2008|2p=267|Shepard|2009b|3p=503}} | |||

| The early reign of that heir, ], was tumultuous, as his mother ], his uncle ], the patriarch ], the powerful ], and other influential figures jockeyed for power.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1p=505|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=540–543|Holmes|2008|3p=267}} In 920, the admiral ] used his fleet to secure power, crowning himself and demoting Constantine to the position of junior co-emperor.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=543–544|Shepard|2009b|2pp=505–507}} His reign, which brought ] and successes in the east under the general ], was ended in 944 by the machinations of his sons, whom Constantine soon usurped in turn.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=508–509|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=546–552|Holmes|2008|3p=268}} Constantine's ineffectual sole rule has often been construed as ], but while several works were compiled, they were largely intended to legitimise and glorify the emperor's ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=553–555|Holmes|2008|2p=268}} ] died young; under two soldier-emperors, ] ({{reign|963|969}}) and ] ({{reign|969|976}}), the Roman army claimed numerous military successes, including the ] and ], and a ] in 971. John in particular was an astute administrator who reformed military structures and implemented effective fiscal policies.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=563–573|Holmes|2008|2p=268–269|Magdalino|2002|3p=176}} | The early reign of that heir, ], was tumultuous, as his mother ], his uncle ], the patriarch ], the powerful ], and other influential figures jockeyed for power.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1p=505|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=540–543|Holmes|2008|3p=267}} In 920, the admiral ] used his fleet to secure power, crowning himself and demoting Constantine to the position of junior co-emperor.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=543–544|Shepard|2009b|2pp=505–507}} His reign, which brought ] and successes in the east under the general ], was ended in 944 by the machinations of his sons, whom Constantine soon usurped in turn.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=508–509|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=546–552|Holmes|2008|3p=268}} Constantine's ineffectual sole rule has often been construed as ], but while several works were compiled, they were largely intended to legitimise and glorify the emperor's ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=553–555|Holmes|2008|2p=268}} ] died young; under two soldier-emperors, ] ({{reign|963|969}}) and ] ({{reign|969|976}}), the Roman army claimed numerous military successes, including the ] and ], and a ] in 971. John in particular was an astute administrator who reformed military structures and implemented effective fiscal policies.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=563–573|Holmes|2008|2p=268–269|Magdalino|2002|3p=176}} | ||

| After John's death, Constantine VII's grandsons ] and ] ruled jointly for half a century, although the latter exercised no real power.{{sfn|Holmes|2008|pp=268}} Their early reign was occupied by conflicts against two prominent generals, ] and ], which ended in 989 with the former's death and the latter's submission, and with a power struggle against the eunuch ], who was dismissed in 985.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=522–526|Magdalino|2002|2p=202|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=573–578}} Basil, who for unknown reasons never married or had children, subsequently refused to delegate any authority: he sidelined the military establishment by taking personal command of the army and promoting officers loyal to him.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=526, 531|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=578–579|Holmes|2008|3p=269}} His reign was preoccupied with ], which ended in total Byzantine victory at the ] in 1018.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=269|Shepard|2009b|2pp=526–29|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=579–582}} Diplomatic efforts, critical for that success,{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1p=529|Holmes|2008|2p=271}} also contributed to the ] in the 1020s and coexistence with the new ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=584|Holmes|2008|2pp=270–271|Magdalino|2002|3p=180}} When he died in 1025, Basil's empire stretched from the Danube and Sicily in the west to the ] in the east; his swift expansion was, however, unaccompanied by administrative reforms.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=531–536|Holmes|2008|2p=271}} | |||

| ] in 1204.|alt=A 3D model of a large city bordered on two sides by water]] | |||

| After John's death, Constantine VII's grandsons ] and ] ruled jointly for half a century, although the latter exercised no real power before Basil's death in 1025.{{sfn|Holmes|2008|pp=268, 271}} Their early reign was occupied by conflicts against two prominent generals, ] and ], which ended in 989 with the former's death and the latter's submission.{{sfnm|Shepard|2009b|1pp=522–526|Magdalino|2002}} | |||

| Between 1021 and 1022, following years of tensions, ] led a series of victorious campaigns against the ], resulting in the annexation of several Georgian provinces to the empire. Basil's successors also annexed ] in 1045. Importantly, both Georgia and Armenia were significantly weakened by the Byzantine administration's policy of heavy taxation and abolishing of the levy. The weakening of Georgia and Armenia played a significant role in the Byzantine ] in 1071.<ref name="RappCrego2018">{{Cite book |last=Toumanoff |first=Cyril |author-link=Cyril Toumanoff |title=Languages and Cultures of Eastern Christianity: Georgian |publisher=Taylor & Francis |year=2018 |isbn=978-1-351-92326-2 |editor-last=Rapp |editor-first=Stephen H. |editor-link=Stephen H. Rapp Jr |location=London and New York |pages=62 |chapter=Caucasia and Byzantium |access-date=30 December 2018 |editor-last2=Crego |editor-first2=Paul |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rH10DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT62 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727162836/https://books.google.com/books?id=rH10DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT62 |archive-date=27 July 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> Basil II is considered among the most capable Byzantine emperors and his reign as the apex of the empire in the ]. By 1025, the date of Basil II's death, the Byzantine Empire stretched from Armenia in the east to ] in southern Italy in the west.{{Sfn|Browning|1992|p=116}} Many successes had been achieved, ranging from the conquest of Bulgaria to the annexation of parts of Georgia and Armenia, and the ], ], and the important city of ]. These were not temporary tactical gains but long-term reconquests.{{Sfn|Browning|1992|p=96}} | |||

| ] (1031) by the Byzantines under ] and the counterattack by the ]|alt=Depiction of an army attacking a walled town]] | ] (1031) by the Byzantines under ] and the counterattack by the ]|alt=Depiction of an army attacking a walled town]] | ||

| After Constantine VIII's death in 1028, his daughters, the empresses ] ({{reign|1028|1052}}) and ] ({{reign|1042|1056}}), held the keys to power: four emperors (], ], ], and ]) ruled only because of their connection to Zoe, while ] ({{reign|1056|1057}}) was selected by Theodora.{{sfnm|Magdalino|2002|1pp=202–203|Holmes|2008|2pp=271–272|Angold|2009|3pp=587–588|Kaldellis|2023|4pp=588–589}} This political instability, regular budget deficits, a string of expensive military failures, and other problems connected to over-extension led to substantial issues in the empire;{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=590, 593|Magdalino|2002|2pp=181–182|Angold|2009|3pp=587–598}} its strategic focus moved from maintaining its hegemony to prioritizing defence.{{sfn|Kaldellis|2023|p=602}} | |||

| The empire soon came under sustained assault on three fronts, from the ], the ] in the north, and the ]. The Byzantine army struggled with confronting these enemies, who did not organise themselves as traditional states and were thus untroubled by defeats in set-piece battles.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1pp=272–273|Magdalino|2002|2p=182|Kaldellis|2023|3p=636}} The year 1071 brought two consequential reverses: ], the last remaining Byzantine settlement in Italy, was ], while the Seljuks won a decisive victory at the ], taking the emperor ] prisoner.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=273|Magdalino|2002|2pp=184–185, 189}} The latter event sparked a decade-long civil war, during which the Seljuks took possession of Anatolia up to the ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=629–637|Angold|2009|2pp=609–610}} | |||

| At the same time, Byzantium was faced with new enemies. Its provinces in southern Italy were threatened by the ] who arrived in Italy at the beginning of the 11th century. During a period of strife between Constantinople and Rome culminating in the ], the ] gradually into ].{{sfn|Vasiliev|1928–1935|p=}} ], the capital of the tagma of Calabria, was captured in 1060 by ], followed by ] in 1068. ], the main Byzantine stronghold in ], was besieged in August 1068 and ].{{Sfnm|2=2000|1p=157|Stephenson|2a1=Hooper|2a2=Bennett|2y=1996|2p=82}} | |||

| === 1081–1204 === | |||

| About 1053, ] disbanded what the historian ] calls the "Iberian Army", which consisted of 50,000 men, and it was turned into a contemporary ]. Two other knowledgeable contemporaries, the former officials ] and ], agree with Skylitzes that by demobilising these soldiers, Constantine did catastrophic harm to the empire's eastern defences. The emergency lent weight to the military aristocracy in Anatolia, who in 1068 secured the election of one of their own, ], as emperor. In the summer of 1071, Romanos undertook a massive eastern campaign to draw the ] into a general engagement with the Byzantine army. At the ], Romanos suffered a surprise defeat against ] ] and was captured. Alp Arslan treated him with respect and imposed no harsh terms on the Byzantines.<ref name="PM">Markham, Paul. "". 1 August 2005. UMass Lowell Faculty. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160429203111/http://faculty.uml.edu/ethan_spanier/Teaching/documents/TheBattleofManzikert.pdf|date=29 April 2016}}".</ref> In Constantinople a coup put in power ], who soon faced the opposition of ] and ]. By 1081, the Seljuks had expanded their rule over virtually the entire Anatolian plateau from Armenia in the east to ] in the west, and had established their capital at ], just {{Convert|90|km|0|abbr=off}} from Constantinople.<ref name=":0">{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Byzantine Empire |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Byzantine-Empire |last1=MacGillivray Nicol |first1=Donald |date= 2024|author-link=Donald Nicol |last2=Teall |first2=John L.}}; Markham, Paul. "". 1 August 2005. UMass Lowell Faculty {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160429203111/http://faculty.uml.edu/ethan_spanier/Teaching/documents/TheBattleofManzikert.pdf|date=29 April 2016}}".</ref> | |||

| {{further|Byzantine Empire under the Komnenos dynasty|Byzantine Empire under the Angelos dynasty}} | |||

| One prominent general, ], usurped the throne in 1081. In contrast to the prior turmoil, the three reigns of Alexios ({{reign|1081|1118}}), his son ] ({{reign|1118|1143}}), and his grandson ] ({{reign|1143|1180}}) lasted a century and ] for the final time.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1pp=273–274|Angold|2009|2p=611}} Alexios immediately faced the Normans under ], who were ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=639–642|Holmes|2008|2p=275|Magdalino|2002|3p=190}} He then targeted the Pechenegs, who ] with help from the ], who were in turn defeated three years later.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=642–644|Holmes|2008|2p=275|Angold|2009|3pp=611–612}} Finally, looking to recover Asia Minor from the Seljuks, he approached ] for help {{circa|1095}}. He did not anticipate the scale of western Christendom's response—the ] led to the recapture of western Anatolia, although Alexios soon fell out with its leaders.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=275|Magdalino|2002|2p=190|Angold|2009|3p=621–623}} The rest of his reign was spent ] and Seljuks, establishing a new, loyal aristocracy to ensure stability, and carrying out fiscal and ecclesiastical reforms.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1pp=274–275|Angold|2009|2pp=612–613, 619–621, 623–625|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=645–647, 659–663}} | |||

| === Komnenian dynasty and the Crusades === | |||

| {{See also|Byzantine Empire under the Komnenos dynasty}} | |||

| ], founder of the ]|alt=A mosaic depicting a haloed crowned man holding a book.]] | |||

| ==== Alexios I and the First Crusade ==== | |||

| {{See also|First Crusade}} | |||

| ] in modern Istanbul, dating from the ], has some of the finest Byzantine frescoes and mosaics.|alt=A color photograph of a domed stone structure with a tree at front center]] | |||

| The ] attained full power under ] in 1081. From the outset of his reign, Alexios faced a formidable attack from the Normans under Guiscard and his son ], who ] and ] and laid siege to ] in ]. Guiscard's death in 1085 temporarily eased the Norman problem. The following year, the Seljuq sultan died, and the sultanate was split due to internal rivalries. By his own efforts, Alexios defeated the ], who were caught by surprise and annihilated at the ] on 28 April 1091.<ref name="Br">{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Byzantine Empire |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Byzantine-Empire |last1=MacGillivray Nicol |first1=Donald |date= 2024|author-link=Donald Nicol |last2=Teall |first2=John L.}}</ref> | |||

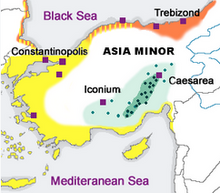

| ] before the ] (1095–1099)|alt=A map showing most of Greece under Byzantine rule and most of Anatolia under Seljuk rule.]] | |||

| Having achieved stability in the West, Alexios could turn his attention to the severe economic difficulties and the disintegration of the empire's traditional defences.{{Sfn|Birkenmeier|2002|p=234}} However, he still did not have enough manpower to recover the lost territories in Asia Minor and to the advance by the Seljuks. At the ] in 1095, envoys from Alexios spoke to ] about the suffering of the Christians of the East and underscored that without help from the West, they would continue to suffer under Muslim rule. Urban saw Alexios' request as a dual opportunity to cement Western Europe and reunite the ] with the ] under his rule.{{Sfnm|Harris|2014|Read|2000|Watson|1993|1p=55|2p=124|3p=12}} On 27 November 1095, Urban called the ] and urged all those present to take up arms under the sign of the ] and launch an armed ] to recover Jerusalem and the East from the Muslims. The response in Western Europe was overwhelming.<ref name="Br" /> Alexios was able to recover a number of important cities, islands and much of western Asia Minor. The Crusaders agreed to become Alexios' vassals under the ] in 1108, which marked the end of the Norman threat during Alexios' reign.{{sfn|Komnene|1928|loc= }}{{sfn|Birkenmeier|2002|p=46}} | |||

| ==== John II, Manuel I, and the Second Crusade ==== | |||

| {{See also|Second Crusade}} | |||

| ] from the ] of Constantinople (modern Istanbul), depicting ] and ], flanked by ] (left) and his wife ] (right), 12th century|alt=A mosaic depicting a haloed woman holding a baby, flanked by a man and woman, both crowned and haloed]] | ] from the ] of Constantinople (modern Istanbul), depicting ] and ], flanked by ] (left) and his wife ] (right), 12th century|alt=A mosaic depicting a haloed woman holding a baby, flanked by a man and woman, both crowned and haloed]] | ||

| Alexios' concentration of power in the hands of his ] meant the most serious political threats came from within the imperial family—before his coronation, John II had to overcome ] and ], and the primary threat during his reign was ].{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=274|Magdalino|2009|2pp=629–630}} John campaigned annually and extensively—he fought the Pechenegs in 1122, the ], and the Seljuks throughout his reign, notably waging ] in his final years—but did not achieve large territorial gains.{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=275|Magdalino|2009|2pp=631–633|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=664–670}} In 1138, John raised the imperial standard over the Crusader ] to intimidate the city into allying with the Byzantines, but chose not to attack, fearing that it would provoke western Christendom to respond.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=669|Holmes|2008|2p=275}} | |||

| Alexios's son ] succeeded him in 1118 and ruled until 1143. John was a pious and dedicated emperor who was determined to undo the damage to the empire suffered at the Battle of Manzikert half a century earlier.{{Sfn|Norwich|1998|p=267}} Famed for his piety and his remarkably mild and just reign, John was an exceptional example of a moral ruler at a time when cruelty was the norm.{{Sfn|Ostrogorsky|1969|p=377}} For this reason, he has been called the Byzantine ]. During his twenty-five-year reign, John made alliances with the ] in the West and decisively defeated the Pechenegs at the ].{{Sfn|Birkenmeier|2002|p=90}} He thwarted Hungarian and Serbian threats during the 1120s, and in 1130 he allied himself with ], the ] against the Norman King ].{{Sfn|Cinnamus|1976|pp=74–75}} | |||

| Manuel I utilised his father's overflowing imperial treasury in pursuit of his ambitions and to secure the empire's position in an increasingly multilateral geopolitical landscape.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=670, 676–677|Magdalino|2009|2pp=644–646}} Through a combination of ], he cultivated a ring of allies and clients around the empire: the Turks of the ], the ], the ], Balkan princes, Italian and Dalmatian cities, and most importantly Antioch and the ], marrying ] in 1161.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=678, 683–688|Holmes|2008|2pp=275–276}} Manuel averted the threat of war during the tumultuous passage of the ] through Byzantine territories in 1147, but the campaign's failure was blamed on the Byzantines by western contemporaries.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=679–681|Magdalino|2009|2pp=637–638}} He was less successful militarily: an invasion of ] was decisively defeated by ] in 1156, leading to tensions with ], the Holy Roman Emperor;{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=682–683|Magdalino|2002|2p=194|Magdalino|2009|3pp=638–641}} two decades later, an invasion of Anatolia was resoundingly defeated at the ].{{sfnm|Magdalino|2009|1pp=643–644|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=692–693}} | |||

| In the later part of his reign, John focused his activities on the East, personally leading ] in Asia Minor. His campaigns fundamentally altered the balance of power in the East, forcing the Turks onto the defensive, while retaking many towns, fortresses, and cities across the peninsula for the Byzantines. He defeated the ] of ] and reconquered all of ],{{Sfn|Harris|2014|p=87}} while forcing ], Prince of Antioch, to recognise Byzantine suzerainty.{{Sfn|Harris|2014|p=93}} In an effort to demonstrate the emperor's role as the leader of the Christian world, John marched into the ] at the head of the combined forces of the empire and the Crusader states; yet despite his efforts in leading the campaign, his hopes were disappointed by the treachery of his Crusader allies.{{Sfn|Harris|2014|pp=95–97}} In 1142, John returned to press his claims to Antioch, but he died in the spring of 1143 following a hunting accident.<ref>{{Cite web |date=4 April 2024 |title=John II Comnenus |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-II-Comnenus |access-date=2024-09-02 |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| John's chosen heir was his fourth son, ], who campaigned aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and east. In Palestine, Manuel allied with the Crusader ] and sent a large fleet to participate in a combined ] of ]. Manuel reinforced his position as overlord of the Crusader states, with his hegemony over Antioch and Jerusalem secured by agreement with ], Prince of Antioch, and ].{{Sfn|Magdalino|2002a|p=74}} In an effort to restore Byzantine control over the ports of southern Italy, he sent an expedition to Italy in 1155, but disputes within the coalition led to the eventual failure of the campaign. Despite this military setback, Manuel's armies successfully invaded the southern parts of the ] in 1167, defeating the Hungarians at the ]. By 1168, nearly the whole of the eastern Adriatic coast lay in Manuel's hands.{{Sfn|Sedlar|1994|p=372}} Manuel made several alliances with the pope and Western Christian kingdoms, and he successfully handled the passage of the crusaders through his empire.{{Sfn|Magdalino|2002a|p=67}} | |||

| In the East, Manuel suffered a major defeat in 1176 at the ] against the Turks. These losses were quickly recovered, and in the following year Manuel's forces inflicted a defeat upon a force of "picked Turks".{{Sfn|Birkenmeier|2002|p=128}} The Byzantine commander ], who destroyed the Turkish invaders at the ], brought troops from the capital and was able to gather an army along the way, a sign that the Byzantine army remained strong and that the defensive program of western Asia Minor was still successful.{{Sfn|Birkenmeier|2002|p=196}} John and Manuel pursued active military policies, and both deployed considerable resources on sieges and city defences; aggressive fortification policies were at the heart of their imperial military policies.{{Sfn|Birkenmeier|2002|pp=185–186}} Despite the defeat at Myriokephalon, the policies of Alexios, John and Manuel resulted in vast territorial gains, increased frontier stability in Asia Minor, and secured the stabilisation of the empire's European frontiers. From {{Circa|1081}} to {{Circa|1180}}, the Komnenian army assured the empire's security, enabling Byzantine civilisation to flourish.{{Sfn|Birkenmeier|2002|p=1}} | |||

| This allowed the Western provinces to achieve an economic revival that continued until the close of the century. It has been argued that Byzantium under the Komnenian rule was more prosperous than at any time since the Persian invasions of the 7th century. During the 12th century, population levels rose and extensive tracts of new agricultural land were brought into production. Archaeological evidence from both Europe and Asia Minor shows a considerable increase in the size of urban settlements, together with a notable upsurge in new towns. Trade was also flourishing; the Venetians, the ] and others opened up the ports of the Aegean to commerce, shipping goods from the Crusader states and Fatimid Egypt to the west and trading with the empire via Constantinople.{{Sfnm|Day|1977|Harvey|2003|1pp=289–290|2pp=241–243}} | |||

| === Decline and disintegration === | |||

| {{Main|Decline of the Byzantine Empire}} | |||

| ==== Angelid dynasty ==== | |||

| {{Main|Byzantine Empire under the Angelos dynasty}} | |||

| Manuel's death on 24 September 1180 left his 11-year-old son ] on the throne. Alexios was highly incompetent in the office, and with his mother ]'s Frankish background, his regency was unpopular.{{Sfn|Norwich|1998|p=291}} Eventually, ], a grandson of Alexios I, overthrew Alexios II in a violent ''coup d'état''. After eliminating his potential rivals, he had himself crowned as co-emperor in September 1183. He eliminated Alexios II and took his 12-year-old wife ] for himself.{{Sfn|Norwich|1998|p=292}} | |||

| Andronikos began his reign well; in particular, the measures he took to reform the government of the empire have been praised by historians. According to the historian ], Andronikos was determined to root out corruption: under his rule, the sale of offices ceased; selection was based on merit, rather than favouritism; and officials were paid an adequate salary to reduce the temptation of bribery. In the provinces, Andronikos's reforms produced a speedy and marked improvement.{{Sfn|Ostrogorsky|1969|p=397}} Gradually, however, Andronikos's reign deteriorated. The aristocrats were infuriated against him, and to make matters worse, Andronikos seemed to have become increasingly unbalanced; executions and violence became increasingly common, and his reign turned into a reign of terror.{{Sfn|Harris|2014|p=118}} Andronikos seemed almost to seek the extermination of the aristocracy as a whole. The struggle against the aristocracy turned into wholesale slaughter, while the emperor resorted to ever more ruthless measures to shore up his regime.{{Sfn|Ostrogorsky|1969|p=397}} | |||

| Despite his military background, Andronikos failed to deal with ] of Cyprus, ] who ] Croatian territories into Hungary, and ] who declared his independence from the Byzantine Empire. Yet, none of these troubles compared to ]'s invasion force of 300 ships and 80,000 men, arriving in 1185 and ].{{Sfn|Norwich|1998|p=293}} Andronikos mobilised a small fleet of 100 ships to defend the capital, but other than that he was indifferent to the populace. He was finally overthrown when ], surviving an imperial assassination attempt, seized power with the aid of the people and had Andronikos killed.{{Sfn|Norwich|1998|pp=294–295}} | |||

| The reign of Isaac II, and more so that of his brother ], saw the collapse of what remained of the centralised machinery of Byzantine government and defence. Although the Normans were driven out of Greece, in 1186 the ] and Bulgars began a rebellion that led to the formation of the ]. The internal policy of the Angeloi was characterised by the squandering of the public treasure and fiscal maladministration. Imperial authority was severely weakened, and the growing power vacuum at the centre of the empire encouraged fragmentation. There is evidence that some Komnenian heirs had set up a semi-independent state in ] before 1204.{{Sfnm|Angold|1997|2a1=Paparrigopoulos|2a2=Karolidis|2p=216|2y=1925|1pp=305–307}} According to the historian ], "the dynasty of the Angeloi, Greek in its origin, ... accelerated the ruin of the Empire, already weakened without and disunited within."{{sfn|Vasiliev|1928–1935|p=}} | |||

| ==== Fourth Crusade and aftermath ==== | |||

| {{further|Fourth Crusade|Frankokratia|Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty}} | |||

| ], by ] (1840)|alt=A painting of an army marching into a city gate with much smoke burning in the background]] | ], by ] (1840)|alt=A painting of an army marching into a city gate with much smoke burning in the background]] | ||

| Manuel's death left the empire rudderless and it soon came under intense pressure.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=695}} His son ] was too young to rule, and his troubled regency was soon overthrown by ], who was himself replaced by ] in 1185.{{sfnm|Magdalino|2002|1p=194|Holmes|2008|2p=276}} Centrifugal forces swirled at the borders as ambitious rulers seized their chance: Hungary and the Turks captured Byzantine territories, ] seized Cyprus; and most injuriously, ] caused the foundation of a ].{{sfnm|Holmes|2008|1p=276|Magdalino|2002|2pp=194–195|Magdalino|2009|3p=655}} Relations with the west deteriorated further after Constantinople allied with ], the vanquisher of the ], whose leaders also conflicted with Byzantium as they passed through its territory.{{sfnm|Magdalino|2002|1pp=195–196|Magdalino|2009|2pp=648–651|Kaldellis|2023|3pp=706–710}} In 1195, Isaac II was deposed by his brother ]; this particular quarrel proved fatal.{{sfn|Holmes|2008|p=276}} | |||

| The ] was originally intended to target ], but amid strategic difficulties, Isaac II's son ] convinced the crusaders to restore his father to the throne in exchange for a huge tribute.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=718–720|Magdalino|2009|2pp=651–652}} They ], reinstating Isaac II and his son to the throne. The new rulers grew swiftly unpopular and were deposed by ], which the crusaders used as a pretext to ], ransacking the wealth it had accumulated over nine centuries.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=720–724|Magdalino|2009|2pp=652–653}} | |||

| In 1198, ] broached the subject of a new crusade through ] and ] letters.{{Sfn|Norwich|1998|p=299}} The stated intent of the crusade was to conquer ], the centre of Muslim power in the Levant. The Crusader army arrived at ] in the summer of 1202 and hired the Venetian fleet to transport them to Egypt. As a payment to the Venetians, they captured the (Christian) port of ] in ], which was a vassal city of Venice, it had rebelled and placed itself under Hungary's protection in 1186.<ref name="BrC">Britannica Concise, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070706062040/http://concise.britannica.com/ebc/article-9383275/Siege-of-Zara |date=6 July 2007 }}.</ref> Shortly afterward, ], son of the deposed and blinded Emperor Isaac II, made contact with the Crusaders. Alexios offered to reunite the Byzantine church with Rome, pay the Crusaders 200,000 silver marks, join the crusade, and provide all the supplies they needed to reach Egypt.{{Sfn|Norwich|1998|p=301}} | |||

| ===1204–1453=== | |||

| ], {{Circa|1204}}|alt=A map showing the competing states after the Fourth Crusade.]] | |||

| ], {{Circa|1204}}.{{sfnm|Laiou|2008|1p=280|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=733–734|Reinert|2002|3pp=250–253|Angold|2009b|4p=731}}|alt=A map showing the competing states after the Fourth Crusade.]] | |||

| The crusaders arrived at Constantinople in the summer of 1203 and ], starting a major fire that damaged large parts of the city, and briefly seized control. Alexios III fled from the capital, and Alexios Angelos was elevated to the throne as Alexios IV along with his blind father Isaac. Alexios IV and Isaac II were unable to keep their promises and were deposed by ]. The crusaders again ], and Constantinople was subjected to pillage and massacre by the rank and file for three days. Many priceless icons, relics and other objects later turned up in ], a large number in Venice. According to chronicler ], a prostitute was even set up on the patriarchal throne.{{sfn|Choniates|1912|loc=}} When order had been restored, the crusaders and the Venetians proceeded to implement their agreement; ] was elected emperor of a new ], and the Venetian ] was chosen as patriarch. The lands divided up among the leaders included most of the former Byzantine possessions.<ref name="Br40 million">{{Cite encyclopedia |title=The Fourth Crusade and the Latin Empire of Constantinople |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Crusades/The-Fourth-Crusade-and-the-Latin-empire-of-Constantinople |last1=Madden |first1=Thomas F. |author-link=Thomas F. Madden |last2=Dickson |first2=Gary|date=2024 }}</ref> Although Venice was more interested in commerce than conquering territory, it took key areas of Constantinople, and the ] took the title of "''Lord of a Quarter and Half a Quarter of the Roman Empire''".{{Sfn|Norwich|1982|pp=11.1–11.2, 127–143}} | |||

| {{further|Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty}} | |||

| Byzantine territories fragmented into competing political entities. The crusaders crowned ] as the ruler of a new ] in Constantinople; it soon suffered ] against the Bulgarians in 1205. It also failed to expand west or east, where three Greek successor states had formed: the ] and the ] in Asia Minor, and the ] on the Adriatic. The Venetians acquired many ports and islands, and the ] emerged in southern Greece.{{sfnm|Laiou|2008|1p=280|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=733–734|Reinert|2002|3pp=250–253|Angold|2009b|4p=731}} Trebizond ] the key port of ] in 1214 and thereafter was unable to affect matters away from the southeastern Black Sea.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=755–758|Angold|2009b|2p=737}} For a time, it seemed like Epirus was the one most likely to reclaim Constantinople from the Latins, and its ruler ] crowned himself emperor, but he suffered ] in 1230 and Epirote power waned.{{sfnm|Laiou|2008|1p=283|Reinert|2002|2p=254|Angold|2009b|3pp=737–738|Kaldellis|2023|4pp=766–770}} | |||

| Nicaea, ruled by the ] and composed of a mixture of Byzantine refugees and native Greeks, blocked the Latins and the Seljuks of Rum from expanding east and west respectively.{{sfnm|Reinert|2002|1p=253|Kaldellis|2023|2pp=760–762}} ] ({{reign|1221|1254}}) was a very capable emperor.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=771|Laiou|2008|2pp=282–283}} His ] economic policies strongly encouraged Nicaean ],{{sfnm|Angold|2009b|1p=740|Laiou|2008|2pp=282–283|Kaldellis|2023|3p=772}} while he made many diplomatic treaties, especially after ] armies ] and ] between 1237 and 1243. This chaos was an opportunity for John, who fought numerous successful campaigns against the states which bore the brunt of the ].{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=774–781|Reinert|2002|2p=254}} Soon after his death, ] was usurped by ], founder of the ], who ] in 1261.{{sfnm|Laiou|2008|1p=283|Reinert|2002|2p=254}} | |||

| After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Latin crusaders, two Byzantine successor states were established: the ] and the ]. A third, the ], was created after ], commanding the ] expedition in ]<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Vasiliev |first=A. A. |author-link=Alexander Vasiliev (historian) |year=1936 |title=The Foundation of the Empire of Trebizond (1204–1222) |journal=] |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=18ff |doi=10.2307/2846872 |jstor=2846872}}</ref> a few weeks before the sack of Constantinople, found himself ] emperor and established himself in Trebizond. Of the three successor states, Epirus and Nicaea stood the best chance of reclaiming Constantinople. The Nicaean Empire struggled to survive the next few decades, however, and by the mid-13th century it had lost much of southern Anatolia.{{Sfnm|Kean|2006|Madden|2005|1pp=150, 164|2p=162}} The weakening of the ] following the ] allowed many ] and ] to set up their own principalities in Anatolia, weakening the Byzantine hold on Asia Minor.{{Sfn|Köprülü|1992|pp=33, 41}} Two centuries later, one of the Beys of these beyliks, ], would establish the ] that would eventually conquer Constantinople.{{Sfn|Köprülü|1992|pp=3–4}} However, the Mongol invasion also gave Nicaea a temporary respite from Seljuk attacks, allowing it to concentrate on the Latin Empire to its north. | |||

| Michael chose to expand the empire, gaining only short-term success. To avoid another sacking of the capital by the Latins, he forced the Church to submit to Rome, again a temporary solution for which the peasantry hated Michael and Constantinople.{{Sfn|Reinert|2002|p=257}} The efforts of ] and later his grandson ] marked Byzantium's last genuine attempts to restore the glory of the empire. However, the use of mercenaries by Andronikos II often backfired, like the time the ] ravaged the countryside, which increased public resentment towards Constantinople.{{Sfn|Reinert|2002|p=261}} | |||

| The Empire of Nicaea, founded by the ], managed to ] in 1261 and defeat ]. This led to a short-lived revival of Byzantine fortunes under ], but the war-ravaged empire was ill-equipped to deal with the enemies that surrounded it. To maintain his campaigns against the Latins, Michael pulled troops from Asia Minor and levied crippling taxes on the peasantry, causing much resentment.{{Sfnm|Madden|2005|Reinert|2002|1p=179|2p=260}} Massive construction projects were completed in Constantinople to repair the damage of the Fourth Crusade, but none of these initiatives were of any comfort to the farmers in Asia Minor suffering raids from Muslim ghazis.{{Sfn|Reinert|2002|p=257}} | |||

| Rather than holding on to his possessions in Asia Minor, Michael chose to expand the empire, gaining only short-term success. To avoid another sacking of the capital by the Latins, he forced the Church to submit to Rome, again a temporary solution for which the peasantry hated Michael and Constantinople.{{Sfn|Reinert|2002|p=257}} The efforts of ] and later his grandson ] marked Byzantium's last genuine attempts to restoring the glory of the empire. However, the use of mercenaries by Andronikos II often backfired, with the ] ravaging the countryside and increasing resentment towards Constantinople.{{Sfn|Reinert|2002|p=261}} | |||

| === Fall === | |||

| {{Main|Byzantine–Ottoman wars|Fall of Constantinople}} | |||

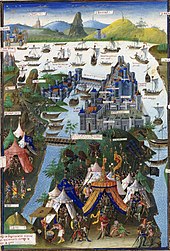

| ] in 1453, depicted in a 15th-century French miniature|alt=A painting of a siege of a city]] | ] in 1453, depicted in a 15th-century French miniature|alt=A painting of a siege of a city]] | ||

| The situation became worse for Byzantium during the civil wars after Andronikos III died. A ] devastated the empire, allowing the Serbian ruler ] to overrun most of the empire's remaining territory and establish a ]. In 1354, an earthquake at ] devastated the fort, allowing the ] |

The situation became worse for Byzantium during the civil wars which erupted after Andronikos III died. A ] devastated the empire, allowing the Serbian ruler ] to overrun most of the empire's remaining territory and establish a ].{{sfn|Vasiliev|1964|pp=617–619}} In 1354, an earthquake at ] devastated the fort, allowing the ] to ] and establish themselves in Europe, after originally being hired as mercenaries during the civil war by ].{{Sfnm|Reinert|2002|1p=268|Vasiliev|1964|2p=622}} By the time the Byzantine civil wars ended, the Ottomans had ] and subjugated them as vassals. After the ], much of the Balkans became dominated by the Ottomans.{{Sfn|Reinert|2002|p=270}} | ||

| Constantinople by this stage was underpopulated and dilapidated. The population of the city had collapsed so severely that it was now little more than a cluster of villages separated by fields. On 2 April 1453, ]'s army of 80,000 men and large numbers of irregulars laid siege to the city.{{Sfn|Runciman|1990|pp=84–86}} Despite a desperate last-ditch defence of the city by the massively outnumbered Christian forces (c. 7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were foreign),{{sfnm|Runciman|1990|1pp=84–85}} Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans after a two-month siege on 29 May 1453. The final Byzantine emperor, ], was last seen casting off his imperial regalia and throwing himself into hand-to-hand combat after the walls of the city were taken.{{Sfn|Hindley|2004|p=300}} | |||

| == Geography == | |||

| {{Main|Outline of the Byzantine Empire#Geography of the Byzantine Empire}} | |||

| The Empire was centred in what is now ] and ] with ] as its capital.{{sfnm|Stathakopoulos|2023|1p=29|Herrin|2009|2p=24}} In the 5th century, it controlled the eastern basis of the Mediterranean running east from ] (modern ]) in a line through the ] and south to ].{{sfn|Herrin|2009|p=24}} This encompassed most of the ], all of modern Greece, Turkey, ], ]; North Africa, primarily with modern ] and ]; the ] along with ], ] and ], and a small settlement in ].{{sfnm|Stathakopoulos|2023|1p=29|Herrin|2009|2p=24}} | |||

| The landscape of the Empire was defined by the fertile fields of ], long mountain ranges and rivers such as the ].{{sfn|Stathakopoulos|2023|pp=29–30}} In the north and west were the Balkans, the corridors between the mountain ranges of ], the ], the ] and the ]. In the south and east were Anatolia, the ] and the ]-] range, which served as passages for armies, while the ] lay between the Empire and its eastern neighbours.{{sfn|Stathakopoulos|2023|p=30}} | |||

| Constantinople at this stage was underpopulated and dilapidated. The population of the city had collapsed so severely that it was now little more than a cluster of villages separated by fields. On 2 April 1453, ]'s army of 80,000 men and large numbers of irregulars laid siege to the city.{{Sfn|Runciman|1990|pp=84–86}} Despite a desperate last-ditch defence of the city by the massively outnumbered Christian forces (c. 7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were foreign),{{sfnm|Runciman|1990|1pp=84–85}} Constantinople finally fell to the Ottomans after ]. The final Byzantine emperor, ], was last seen casting off his imperial regalia and throwing himself into hand-to-hand combat after the walls of the city were taken.{{Sfn|Hindley|2004|p=300}} | |||

| ] connected the Empire by land, with the ] running from Constantinople to the Albanian coast through ] and the ] to Adrianople (modern ]), Serdica (modern ]) and Singidunum.{{sfn|Stathakopoulos|2023|pp=30–31}} By water, Crete, Cyprus and Sicily were key naval points and the main ports connecting Constantinople were Alexandria, Gaza, ] and Antioch.{{sfnm|Stathakopoulos|2023|1p=30|Herrin|2009|2p=25}} The ] was considered an internal lake within the Empire.{{sfn|Stathakopoulos|2023|p=30}} | |||

| == Government == | == Government == | ||

| Line 251: | Line 206: | ||

| === Governance === | === Governance === | ||

| {{See also|Roman emperor|Coronation of the Byzantine emperor|Byzantine bureaucracy and aristocracy}} | {{See also|Roman emperor|Coronation of the Byzantine emperor|Byzantine bureaucracy and aristocracy}} | ||

| The patriarch inaugurated emperors from 457 onwards, while the crowds of Constantinople proclaimed their support, thus legitimizing their rule.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1pp=35, 189, 222|Nicol|1988|2p=63|Howard-Johnston|2024|3p=8}} The ] originally had its own identity but later became a ceremonial extension of the emperor's court.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=35|Howard-Johnston|2024|2p=8|Browning|1992|3p=98}} The reign of Phocas ({{Reign|602|610}}) was the first military coup after the third century, and he was one of 43 emperors violently removed from power.{{sfnm|Kaldellis|2023|1p=338|Treadgold|1997|2p=326|Nicol|1988|3p=64}} From Heraclius' accession in 610 till 1453, a total of nine dynasties ruled the Empire. During this time, for only 30 of the 843 years were the reigning emperors unrelated by blood or kinship, largely due to the practice of co-emperorship.{{sfn|Nicol|1988|p=63}} | |||