| Revision as of 09:47, 5 January 2025 editDay Creature (talk | contribs)990 edits added Category:Auschwitz concentration camp prisoners using HotCat← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:13, 13 January 2025 edit undoCanonNiAWB (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions1,781 editsm clean up, typo(s) fixed: November 6, 1890 → November 6, 1890,Tag: AWB | ||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ⚫ | {{copy edit|date=November 2024}} | ||

| {{Short description|Jewish-German Immigrant}} | {{Short description|Jewish-German Immigrant}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{copy edit|date=November 2024}} | ||

| '''Erich Dublon''' was a German-Jewish man living in ] during the rise of ] oppression. He fled Germany and attempted to immigrate to ] with his brother Wilhelm Dublon, his sister-in-law Erna Dublon, and his two young nieces, Lore and Eva.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Reinfelder |first=Georg |title=MS "St. Louis": die Irrfahrt nach Kuba : Frühjahr 1939 : Kapitän Gustav Schröder rettet 906 deutsche Juden vor dem Zugriff der Nazis |year=2002 |isbn=3933471303 |location=Germany}}</ref> The Dublon family boarded the ], a Cuban-bound ship that carried hundreds of European Jews desperate to escape persecution.<ref name=":4">{{Cite book |last=Ther |first=Philipp |title=The Outsiders: Refugees in Europe Since 1942 |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2021 |isbn=9780691207131}}</ref> After a sixteen-day transatlantic journey, the ] reached Cuba.<ref name=":0" /> Dublon and the other passengers remained in the Harbor in Havana while the authorities deliberated over allowing the refugees entry into the country.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Long Mullins |first=Robin |date=2013 |title=The SS St. Louis and the importance of reconciliation. |url=https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0034610 |journal=Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology |language=en |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=393–398 |doi=10.1037/a0034610 |issn=1532-7949}}</ref> The SS St. Louis refugees were ultimately denied entry into both Cuba and the United States.<ref name=":1" /> Dublon was sent back to Europe, settling in ].<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |title=Voyage of the "St. Louis," May 13-June 17, 1939 |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/map/voyage-of-the-st-louis-may-13-june-17-1939 |access-date=2024-02-28 |website=United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |language=}}</ref> As ] policies intensified, the Dublon family was rounded up and subsequently exterminated in the ].<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=Ogilvie, Miller |title=Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passangers and the Holocaust |publisher=University of Wisconsin Press |year=2010 |isbn=9780299219833 |location=Ukraine}}</ref> | '''Erich Dublon''' was a German-Jewish man living in ] during the rise of ] oppression. He fled Germany and attempted to immigrate to ] with his brother Wilhelm Dublon, his sister-in-law Erna Dublon, and his two young nieces, Lore and Eva.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Reinfelder |first=Georg |title=MS "St. Louis": die Irrfahrt nach Kuba : Frühjahr 1939 : Kapitän Gustav Schröder rettet 906 deutsche Juden vor dem Zugriff der Nazis |year=2002 |isbn=3933471303 |location=Germany}}</ref> The Dublon family boarded the ], a Cuban-bound ship that carried hundreds of European Jews desperate to escape persecution.<ref name=":4">{{Cite book |last=Ther |first=Philipp |title=The Outsiders: Refugees in Europe Since 1942 |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2021 |isbn=9780691207131}}</ref> After a sixteen-day transatlantic journey, the ] reached Cuba.<ref name=":0" /> Dublon and the other passengers remained in the Harbor in Havana while the authorities deliberated over allowing the refugees entry into the country.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Long Mullins |first=Robin |date=2013 |title=The SS St. Louis and the importance of reconciliation. |url=https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0034610 |journal=Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology |language=en |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=393–398 |doi=10.1037/a0034610 |issn=1532-7949}}</ref> The SS St. Louis refugees were ultimately denied entry into both Cuba and the United States.<ref name=":1" /> Dublon was sent back to Europe, settling in ].<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |title=Voyage of the "St. Louis," May 13-June 17, 1939 |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/map/voyage-of-the-st-louis-may-13-june-17-1939 |access-date=2024-02-28 |website=United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |language=}}</ref> As ] policies intensified, the Dublon family was rounded up and subsequently exterminated in the ].<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=Ogilvie, Miller |title=Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passangers and the Holocaust |publisher=University of Wisconsin Press |year=2010 |isbn=9780299219833 |location=Ukraine}}</ref> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| == Early life == | == Early life == | ||

| Erich Dublon was born on November |

Erich Dublon was born on November 6, 1890, in Apolda, Germany.<ref>{{cite web |title=Erich Dublon |url=https://www.geni.com/people/Erich-Dublon/6000000036776474970 |website=geni_family_tree |publisher=] |access-date=27 April 2024 |date=7 August 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |title=Voyage of the St. Louis |url=https://www.ushmm.org/online/st-louis/detail.php?PassengerId=144&letter=D&ord=150 |access-date=2024-02-28 |website=www.ushmm.org}}</ref> Later on, he resided in ] with his brother, sister-in-law, and nieces. Dublon and his brother, Willi Dublon, co-owned a shoe store called Salamander Schuhe.<ref name=":2" /> The Dublon family lived contently in Erfurt despite the increasingly repressive social and political climate.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| == Nazi persecution == | == Nazi persecution == | ||

| The aftermath of ] fostered a dangerous political, economic, and social climate in Germany. A severe financial crisis involving ], poverty, and mass unemployment contributed to the rise of ] fascist and staunchly antisemitic regime.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web |last=Michalczyk |first=John J. |title=Nazi Law : From Nuremberg to Nuremberg |url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&an=1625632&site=ehost-live&scope=site |access-date=2024-02-28 |website=search.ebscohost.com}}</ref> After the ] seized power in Germany, Nazi leaders began to implement harsh economic restrictions to isolate and eventually eliminate Jews from European society. The ], enacted in September |

The aftermath of ] fostered a dangerous political, economic, and social climate in Germany. A severe financial crisis involving ], poverty, and mass unemployment contributed to the rise of ] fascist and staunchly antisemitic regime.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web |last=Michalczyk |first=John J. |title=Nazi Law : From Nuremberg to Nuremberg |url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&an=1625632&site=ehost-live&scope=site |access-date=2024-02-28 |website=search.ebscohost.com}}</ref> After the ] seized power in Germany, Nazi leaders began to implement harsh economic restrictions to isolate and eventually eliminate Jews from European society. The ], enacted in September 1935, devised a legal distinction between Germans and Jews.<ref name=":3" /> These laws revoked Jewish rights to German citizenship, as well as legalized and encouraged the systemic persecution of Jews.<ref name=":3" /> Despite this Nazi tyranny, the Dublon family refused to uproot their lives and were hopeful that the period of antisemitism would pass.<ref name=":0" /> The Dublons accepted that living in Germany was no longer possible after the ] and several Nazi policies restricting Jewish economic life.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| == Immigration policies == | == Immigration policies == | ||

| Dublon's brother, Willi Dublon, was successful in securing spots on the St. Louis motor ship for himself and his entire family. This included Erich, Willi, Erna, twelve-year-old Lore, and six-year-old Eva.<ref name=":0" /> The passengers on the St. Louis were made up of mostly Jewish refugees who were also hoping to escape ].<ref name=":1" /> The immigrants were granted permits for their stay in Cuba by the Director of Immigration, Manuel Bonitez Gonzalez.<ref name=":1" /> Unbeknownst to Erich and many other St. Louis passengers, Gonzalez was a corrupt actor and the visas were never approved by the ].<ref name=":1" /> The Dublons intended to live in Cuba until they could gain entry into the United States.<ref name=":2" /> After WWI, the United States cracked down on immigration by enacting the ], which placed strict quotas on the number of foreigners allowed into the country.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |last=United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |title=United States Immigration and Refugee Law, 1921-1980 |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/united-states-immigration-and-refugee-law-1921-1980 |access-date=2024-03-01 |website=encyclopedia.ushmm.org |language=en}}</ref> In the wake of the ], Americans were highly distrustful of foreigners as they believed an immigrant labor force would threaten employment opportunities for domestic workers.<ref name=":5" /> There was also great suspicion of foreigners who held citizenship in enemy countries. Immigration quotas were set considerably low for countries with high volumes of Jewish immigrants, posing a significant obstacle that prevented numerous Jews from escaping to safety.<ref name=":5" /> | Dublon's brother, Willi Dublon, was successful in securing spots on the St. Louis motor ship for himself and his entire family. This included Erich, Willi, Erna, twelve-year-old Lore, and six-year-old Eva.<ref name=":0" /> The passengers on the St. Louis were made up of mostly Jewish refugees who were also hoping to escape ].<ref name=":1" /> The immigrants were granted permits for their stay in Cuba by the Director of Immigration, Manuel Bonitez Gonzalez.<ref name=":1" /> Unbeknownst to Erich and many other St. Louis passengers, Gonzalez was a corrupt actor and the visas were never approved by the ].<ref name=":1" /> The Dublons intended to live in Cuba until they could gain entry into the United States.<ref name=":2" /> After WWI, the United States cracked down on immigration by enacting the ], which placed strict quotas on the number of foreigners allowed into the country.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |last=United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |title=United States Immigration and Refugee Law, 1921-1980 |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/united-states-immigration-and-refugee-law-1921-1980 |access-date=2024-03-01 |website=encyclopedia.ushmm.org |language=en}}</ref> In the wake of the ], Americans were highly distrustful of foreigners as they believed an immigrant labor force would threaten employment opportunities for domestic workers.<ref name=":5" /> There was also great suspicion of foreigners who held citizenship in enemy countries. Immigration quotas were set considerably low for countries with high volumes of Jewish immigrants, posing a significant obstacle that prevented numerous Jews from escaping to safety.<ref name=":5" /> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| == SS St. Louis == | == SS St. Louis == | ||

| The St. Louis departed for Cuba on May |

The St. Louis departed for Cuba on May 13, 1939.<ref name=":1" /> There is an extensive and personal record of Erich Dublon's experience on the ship due to the recovery of his travel diary.<ref name=":0" /> The diary was kept by a family friend of the Dublons, Peter Heiman, who was able to successfully immigrate from Erfurt to the United States.<ref name=":2" /> Dublon describes the jovial and hopeful atmosphere on the St. Louis when the immigrants first boarded. The luxury accommodations, excellent food, and myriad of onboard activities inspired a sense of optimism in the Dublons and excitement for the beginning of their new lives.<ref name=":0" /> Erich also documents the strong feeling of community as he and his family were able to connect with fellow Erfurt immigrants.<ref name=":0" /> After sixteen days of sailing, the St. Louis arrived in ].<ref name=":4" /> | ||

| The ship remained stagnant in Havana's Harbor as authorities aboard the St. Louis negotiated with the Cuban government over the canceled visas. The ] attempted to persuade Cuba and the United States to accept the passengers under asylum, but their arguments were unsuccessful.<ref name=":1" /> While these deliberations were occurring, Dublon's diary reflects a great deal of uncertainty and grief among the passengers. It was unclear why the immigrants were not permitted to disembark and they were unaware that many of their visas had been illegally issued.<ref name=":0" /> On the fifth day of waiting in the harbor as it became evident something was amiss, Dublon's diary noted several passengers' suicides. On the seventh day of sitting in the harbor, the announcement was made to the passengers that they had been denied entry into Cuba.<ref name=":0" /> The St. Louis was escorted out of the harbor by several Cuban police boats, who had suggested the use of force if the ship resisted. The St. Louis also journeyed to ] where they also attempted to gain entry, but were again turned away.<ref name=":4" /> On June 10 1939, the passengers were informed that the St. Louis had no alternative but to return to Europe.<ref name=":1" /> Dublon's journal entries reflect the intense emotions and desperation of the passengers, many of whom where crying at the announcement of the ship's return to Europe.<ref name=":0" /> | The ship remained stagnant in Havana's Harbor as authorities aboard the St. Louis negotiated with the Cuban government over the canceled visas. The ] attempted to persuade Cuba and the United States to accept the passengers under asylum, but their arguments were unsuccessful.<ref name=":1" /> While these deliberations were occurring, Dublon's diary reflects a great deal of uncertainty and grief among the passengers. It was unclear why the immigrants were not permitted to disembark and they were unaware that many of their visas had been illegally issued.<ref name=":0" /> On the fifth day of waiting in the harbor as it became evident something was amiss, Dublon's diary noted several passengers' suicides. On the seventh day of sitting in the harbor, the announcement was made to the passengers that they had been denied entry into Cuba.<ref name=":0" /> The St. Louis was escorted out of the harbor by several Cuban police boats, who had suggested the use of force if the ship resisted. The St. Louis also journeyed to ] where they also attempted to gain entry, but were again turned away.<ref name=":4" /> On June 10, 1939, the passengers were informed that the St. Louis had no alternative but to return to Europe.<ref name=":1" /> Dublon's journal entries reflect the intense emotions and desperation of the passengers, many of whom where crying at the announcement of the ship's return to Europe.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| == Return to Europe == | == Return to Europe == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ], the ], ], and ] had approved the St. Louis refugees to seek temporary residence in their countries.<ref name=":6" /> Dublon and the rest of his family were assigned to live in Belgium and the St. Louis arrived in ] on June |

], the ], ], and ] had approved the St. Louis refugees to seek temporary residence in their countries.<ref name=":6" /> Dublon and the rest of his family were assigned to live in Belgium and the St. Louis arrived in ] on June 17, 1939.<ref name=":2" /> Dublon's nieces, Lore and Eva, had difficulties adjusting to their new life in Antwerp. They particularly struggled with the language barrier between themselves and their classmates.<ref name=":2" /> Despite the hardships they experienced, the Dublon family remained relationally close. They enjoyed weekly nature walks together and slowly became accustomed to their new lives in Antwerp.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

| == Deportation == | == Deportation == | ||

| Belgium had remained a neutral country amid ] when Dublon initially moved there in 1939.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web |last=United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |title=Belgium |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/belgium |access-date=2024-03-02 |website=encyclopedia.ushmm.org |language=en}}</ref> However, in May |

Belgium had remained a neutral country amid ] when Dublon initially moved there in 1939.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web |last=United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |title=Belgium |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/belgium |access-date=2024-03-02 |website=encyclopedia.ushmm.org |language=en}}</ref> However, in May 1940, the German military was victorious in capturing Belgium for the Nazi Regime.<ref name=":7" /> The Germans immediately began implementing Nazi policies to consolidate and eventually exterminate Belgium's Jewish population. The Germans conducted an extensive census that attempted to identify all Jews residing in the area.<ref name=":2" /> Dublon was sent to the ] at the age of 50 and was later deported to ]. Instead of immediately being sent to the gas chambers to be murdered, Dublon was selected for harsh forced labor within the camp.<ref name=":2" /> Auschwitz records reflect that Dublon died of a heart attack in the camp on September 3, 1942.<ref name=":2" /> Dublon's brother Willi was also discovered by the ] and subsequently sent to the ] on December 23, 1943.<ref name=":2" /> Erna Dublon and her two daughters Lore and Eva were also captured on January 8, 1944. The remainder of the Dublon family was moved to Auschwitz on January 17, 1944.<ref name=":2" /> Fifty-four-year-old Willi, forty-year-old Erna, and ten-year-old Eva were all exterminated in the gas chambers upon arrival in Auschwitz. Sixteen-year-old Lore was deemed desirable for forced labor by Nazi officials. She was consequently relocated to the Golleschau camp where she eventually died.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

| == Legacy == | == Legacy == | ||

| Line 31: | Line 32: | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{improve categories|date=November 2024}} | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Dublon, Erich}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Dublon, Erich}} | ||

| Line 36: | Line 39: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | {{improve categories|date=November 2024}} | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:13, 13 January 2025

Jewish-German Immigrant| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (November 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Erich Dublon was a German-Jewish man living in Erfurt, Germany during the rise of Nazi oppression. He fled Germany and attempted to immigrate to Cuba with his brother Wilhelm Dublon, his sister-in-law Erna Dublon, and his two young nieces, Lore and Eva. The Dublon family boarded the SS St. Louis, a Cuban-bound ship that carried hundreds of European Jews desperate to escape persecution. After a sixteen-day transatlantic journey, the SS St. Louis reached Cuba. Dublon and the other passengers remained in the Harbor in Havana while the authorities deliberated over allowing the refugees entry into the country. The SS St. Louis refugees were ultimately denied entry into both Cuba and the United States. Dublon was sent back to Europe, settling in Antwerp, Belgium. As Nazi extermination policies intensified, the Dublon family was rounded up and subsequently exterminated in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Early life

Erich Dublon was born on November 6, 1890, in Apolda, Germany. Later on, he resided in Erfurt, Germany with his brother, sister-in-law, and nieces. Dublon and his brother, Willi Dublon, co-owned a shoe store called Salamander Schuhe. The Dublon family lived contently in Erfurt despite the increasingly repressive social and political climate.

Nazi persecution

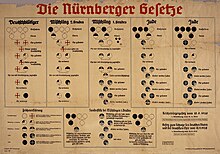

The aftermath of WWI fostered a dangerous political, economic, and social climate in Germany. A severe financial crisis involving hyperinflation, poverty, and mass unemployment contributed to the rise of Adolf Hitler's fascist and staunchly antisemitic regime. After the Third Reich seized power in Germany, Nazi leaders began to implement harsh economic restrictions to isolate and eventually eliminate Jews from European society. The Nuremberg Laws, enacted in September 1935, devised a legal distinction between Germans and Jews. These laws revoked Jewish rights to German citizenship, as well as legalized and encouraged the systemic persecution of Jews. Despite this Nazi tyranny, the Dublon family refused to uproot their lives and were hopeful that the period of antisemitism would pass. The Dublons accepted that living in Germany was no longer possible after the Kristallnacht Pogroms and several Nazi policies restricting Jewish economic life.

Immigration policies

Dublon's brother, Willi Dublon, was successful in securing spots on the St. Louis motor ship for himself and his entire family. This included Erich, Willi, Erna, twelve-year-old Lore, and six-year-old Eva. The passengers on the St. Louis were made up of mostly Jewish refugees who were also hoping to escape Nazi persecution. The immigrants were granted permits for their stay in Cuba by the Director of Immigration, Manuel Bonitez Gonzalez. Unbeknownst to Erich and many other St. Louis passengers, Gonzalez was a corrupt actor and the visas were never approved by the Cuban Government. The Dublons intended to live in Cuba until they could gain entry into the United States. After WWI, the United States cracked down on immigration by enacting the Immigration Act of 1924, which placed strict quotas on the number of foreigners allowed into the country. In the wake of the Great Depression, Americans were highly distrustful of foreigners as they believed an immigrant labor force would threaten employment opportunities for domestic workers. There was also great suspicion of foreigners who held citizenship in enemy countries. Immigration quotas were set considerably low for countries with high volumes of Jewish immigrants, posing a significant obstacle that prevented numerous Jews from escaping to safety.

SS St. Louis

The St. Louis departed for Cuba on May 13, 1939. There is an extensive and personal record of Erich Dublon's experience on the ship due to the recovery of his travel diary. The diary was kept by a family friend of the Dublons, Peter Heiman, who was able to successfully immigrate from Erfurt to the United States. Dublon describes the jovial and hopeful atmosphere on the St. Louis when the immigrants first boarded. The luxury accommodations, excellent food, and myriad of onboard activities inspired a sense of optimism in the Dublons and excitement for the beginning of their new lives. Erich also documents the strong feeling of community as he and his family were able to connect with fellow Erfurt immigrants. After sixteen days of sailing, the St. Louis arrived in Havana, Cuba.

The ship remained stagnant in Havana's Harbor as authorities aboard the St. Louis negotiated with the Cuban government over the canceled visas. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee attempted to persuade Cuba and the United States to accept the passengers under asylum, but their arguments were unsuccessful. While these deliberations were occurring, Dublon's diary reflects a great deal of uncertainty and grief among the passengers. It was unclear why the immigrants were not permitted to disembark and they were unaware that many of their visas had been illegally issued. On the fifth day of waiting in the harbor as it became evident something was amiss, Dublon's diary noted several passengers' suicides. On the seventh day of sitting in the harbor, the announcement was made to the passengers that they had been denied entry into Cuba. The St. Louis was escorted out of the harbor by several Cuban police boats, who had suggested the use of force if the ship resisted. The St. Louis also journeyed to Florida where they also attempted to gain entry, but were again turned away. On June 10, 1939, the passengers were informed that the St. Louis had no alternative but to return to Europe. Dublon's journal entries reflect the intense emotions and desperation of the passengers, many of whom where crying at the announcement of the ship's return to Europe.

Return to Europe

Great Britain, the Netherlands, France, and Belgium had approved the St. Louis refugees to seek temporary residence in their countries. Dublon and the rest of his family were assigned to live in Belgium and the St. Louis arrived in Antwerp on June 17, 1939. Dublon's nieces, Lore and Eva, had difficulties adjusting to their new life in Antwerp. They particularly struggled with the language barrier between themselves and their classmates. Despite the hardships they experienced, the Dublon family remained relationally close. They enjoyed weekly nature walks together and slowly became accustomed to their new lives in Antwerp.

Deportation

Belgium had remained a neutral country amid World War II when Dublon initially moved there in 1939. However, in May 1940, the German military was victorious in capturing Belgium for the Nazi Regime. The Germans immediately began implementing Nazi policies to consolidate and eventually exterminate Belgium's Jewish population. The Germans conducted an extensive census that attempted to identify all Jews residing in the area. Dublon was sent to the Mechelen Transit camp at the age of 50 and was later deported to Auschwitz. Instead of immediately being sent to the gas chambers to be murdered, Dublon was selected for harsh forced labor within the camp. Auschwitz records reflect that Dublon died of a heart attack in the camp on September 3, 1942. Dublon's brother Willi was also discovered by the Gestapo and subsequently sent to the Mechelen Transit camp on December 23, 1943. Erna Dublon and her two daughters Lore and Eva were also captured on January 8, 1944. The remainder of the Dublon family was moved to Auschwitz on January 17, 1944. Fifty-four-year-old Willi, forty-year-old Erna, and ten-year-old Eva were all exterminated in the gas chambers upon arrival in Auschwitz. Sixteen-year-old Lore was deemed desirable for forced labor by Nazi officials. She was consequently relocated to the Golleschau camp where she eventually died.

Legacy

Erich Dublon's travel diary has provided critical insight into the voyage of the SS St. Louis. It created a meticulous record of the everyday lives of the St. Louis passengers and captures the emotional distress when the immigrants were denied entry into Havana. The recovery of Erich's diary has made significant contributions to the historical record of Jewish immigration during World War II and the journey of the SS St. Louis.

References

- ^ Reinfelder, Georg (2002). MS "St. Louis": die Irrfahrt nach Kuba : Frühjahr 1939 : Kapitän Gustav Schröder rettet 906 deutsche Juden vor dem Zugriff der Nazis. Germany. ISBN 3933471303.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ther, Philipp (2021). The Outsiders: Refugees in Europe Since 1942. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691207131.

- ^ Long Mullins, Robin (2013). "The SS St. Louis and the importance of reconciliation". Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. 19 (4): 393–398. doi:10.1037/a0034610. ISSN 1532-7949.

- ^ "Voyage of the "St. Louis," May 13-June 17, 1939". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Ogilvie, Miller (2010). Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passangers and the Holocaust. Ukraine: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299219833.

- "Erich Dublon". geni_family_tree. Geni.com. 7 August 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "Voyage of the St. Louis". www.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Michalczyk, John J. "Nazi Law : From Nuremberg to Nuremberg". search.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "United States Immigration and Refugee Law, 1921-1980". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "Belgium". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

| This article needs additional or more specific categories. Please help out by adding categories to it so that it can be listed with similar articles. (November 2024) |