| Revision as of 22:45, 23 March 2008 editGiano II (talk | contribs)22,233 edits reverting what can only be described as a trolling and daft edit. The greta fire of London is well known. London, England shows ignorance← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:58, 15 January 2025 edit undoNikkimaria (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users233,391 edits source?Tag: Manual revert | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Conflagration in 1666}} | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{pp-pc}} | |||

| {{About|the 1666 Fire of London|other "Great Fires"|List of historic fires |other notable fires in London|Early fires of London|and|Second Great Fire of London|the Peter Ackroyd novel|The Great Fire of London (novel)}} | |||

| {{Featured article}} | |||

| {{bots|deny=Citation bot}}{{Use British English|date=September 2019}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2022}} | |||

| ] on the evening of Tuesday, 4 September 1666. To the left is ]; to the right, the ]. ] is in the distance, surrounded by the tallest flames.]] | |||

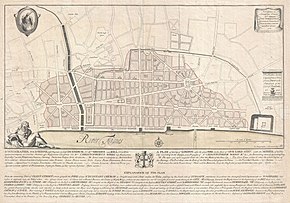

| ] in 1666, with the burnt area shown in pink and outlined in dashes (] origin{{efn|name=Pudding}} marked with a green line)]] | |||

| The '''Great Fire of London''' was a major ] that swept through central ] from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666,{{efn|All dates are given according to the ]. When recording British history, it is usual to use the dates recorded at the time of the event. Any dates between 1 January and 25 March have their year adjusted to start on 1 January according to the ].}} gutting the medieval ] inside the old ], while also extending past the wall to the west. The death toll is generally thought to have been relatively small,<ref name=tindeath/><ref name=porterdeath/> although some historians have challenged this belief.<ref name="Hanson 2001, 326–33"/> | |||

| ] from a boat in the vicinity of ]. The ] is on the right and ] on the left, with ] in the distance, surrounded by the tallest flames.]] | |||

| The '''Great Fire of London''' was a major ] that swept through the central parts of ] from Sunday, ] to Wednesday, ], ].<ref>All dates are given according to the ]: when recording British history it is usual to use the dates recorded at the time of the event with the year adjusted to start on the 1 January.</ref> The fire gutted the medieval ] inside the old ] ]. It threatened, but did not reach, the aristocratic district of ] (the modern ]), ]'s ], and most of the suburban ]s.<ref>Porter, 69–80.</ref> It consumed 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, ], and most of the buildings of the City authorities. It is estimated that it destroyed the homes of 70,000 of the City's ca. 80,000 inhabitants.<ref>Tinniswood, 4, 101.</ref> The death toll from the fire is unknown and is traditionally thought to have been small, as only a few verified deaths were recorded. This reasoning has recently been challenged on the grounds that the deaths of poor and middle-class people were not recorded anywhere, and that the heat of the fire may have cremated many victims, leaving no recognisable remains. | |||

| The fire started |

The fire started in a bakery in ] shortly after ] on Sunday 2 September, and spread rapidly. The use of the major ] technique of the time, the creation of ]s by means of removing structures in the fire's path, was critically delayed due to the indecisiveness of the ], Sir ]. By the time large-scale demolitions were ordered on Sunday night, the wind had already fanned the bakery fire into a ] which defeated such measures. The fire pushed north on Monday into the heart of the City. Order in the streets broke down as rumours arose of suspicious foreigners setting fires. The fears of the homeless focused on the French and Dutch, England's enemies in the ongoing ]; these substantial immigrant groups became victims of street violence. On Tuesday, the fire spread over nearly the whole city, destroying St Paul's Cathedral and leaping the ] to threaten ]'s court at ]. Coordinated firefighting efforts were simultaneously getting underway. The battle to put out the fire is considered to have been won by two key factors: the strong east wind dropped, and the ] garrison used ] to create effective firebreaks, halting further spread eastward. | ||

| The social and economic problems created by the disaster were overwhelming. |

The social and economic problems created by the disaster were overwhelming. Flight from London and settlement elsewhere were strongly encouraged by Charles II, who feared a London rebellion amongst the dispossessed refugees. Various schemes for rebuilding the city were proposed, some of them very radical. After the fire, London was reconstructed on essentially the same medieval street plan, which still exists today.<ref>Reddaway, 27</ref> | ||

| ==London in the 1660s== |

== London in the 1660s == | ||

| By the 1660s, London was by far the largest city in Britain and the third largest in the Western world, estimated at 300,000 to 400,000 inhabitants.<ref>Field, 7</ref><ref name=tin-london /> ], contrasting London to the ] magnificence of ] in 1659, called it a "wooden, northern, and inartificial congestion of Houses".<ref>], quoted in Tinniswood, 3</ref> By "inartificial", Evelyn meant unplanned and makeshift, the result of organic growth and unregulated ].<ref name="Porter, 80">Porter, 80</ref> London had become progressively more crowded inside its defensive city wall which dated to Roman times. It had also pushed outwards beyond the wall into extramural settlements such as ], ], ], ] and ], and the ]. To the West it reached along ] to the Royal Palace and Abbey at ].<ref name="Porter, 80" /><ref>Field, 7–9</ref> | |||

| By the late 17th century, the City proper—the area bounded by the city wall and the ]—was only a part of London, covering some {{convert|700|acres|km2 sqmi}},<ref>330 acres is the size of the area within the Roman wall, according to standard reference works (see, for instance, Sheppard, 37), although Tinniswood gives that area as a square mile (667 acres).</ref> and home to about 80,000 people, or one quarter of London's inhabitants. The City was surrounded by a ring of inner suburbs where most Londoners lived.<ref name=tin-london /> The City was then, as now, the commercial heart of the capital, and was the largest market and busiest port in England, dominated by the trading and manufacturing classes.<ref>Hanson, 80</ref> The City was traffic-clogged, polluted, and unhealthy, especially after it was hit by a devastating outbreak of ] in the ] of 1665.<ref name=tin-london>Tinniswood, 1–11</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| By the 1660s, ] was by far the largest city in Britain, estimated at half a million inhabitants, which was more than the next fifty towns in England combined.<ref>Morgan, 293–4.</ref> Comparing London to the ] magnificence of ], ] called it a "wooden, northern, and inartificial congestion of Houses," and expressed alarm about the fire hazard posed by the wood and the congestion.<ref>] in 1659, quoted in Tinniswood, 3. The section "London in the 1660s" is based on Tinniswood, 1–11, unless otherwise indicated.</ref> By "inartificial", Evelyn meant unplanned and makeshift, the result of organic growth and unregulated ]. A Roman settlement for four centuries, London had become progressively more overcrowded inside its defensive ]. It had also pushed outwards beyond the wall into squalid extramural ]s such as ], ], and ] and had reached to physically incorporate the independent city of ].<ref>Porter, 80.</ref> | |||

| The relationship between the City and the Crown was often tense. The City of London had been a stronghold of ] during the ] (1642–1651), and the wealthy and economically dynamic capital still had the potential to be a threat to Charles II, as had been demonstrated by several republican uprisings in London in the early 1660s. The City magistrates were of the generation that had fought in the Civil War, and could remember how ]'s grab for ] had led to that national trauma.<ref>See Hanson, 85–88, for the Republican temper of London</ref> They were determined to thwart any similar tendencies in his son, and when the Great Fire threatened the City, they refused the offers that Charles made of soldiers and other resources. Even in such an emergency, the idea of having the unpopular royal troops ordered into the City was political dynamite. By the time that Charles took over command from the ineffectual Lord Mayor, the fire was already out of control.<ref name="Wallington2005">Wallington, 18</ref><ref name=tin-london /> | |||

| By the late 17th century, the City proper—the area bounded by the City wall and the ]—was only one part of London, covering 700 acres (2.8 ]),<ref>330 acres is the size of the area within the Roman wall according to standard reference works (see, for instance, Sheppard, 37), although Tinniswood gives that area as a square mile (667 acres).</ref> and home to about 80,000 people, or one sixth of London's inhabitants. The City was surrounded by a ring of inner suburbs, where most Londoners lived. The City was then as now the commercial heart of the capital, the largest market and busiest port in England, dominated by the trading and manufacturing classes.<ref>Hanson, 80.</ref> The ] shunned the City and lived either in the countryside beyond the slum suburbs, or further west in the exclusive Westminster district (the modern ]), the site of ]'s court at Whitehall. Wealthy people preferred to live at a convenient distance from the always traffic-jammed, polluted, unhealthy City, especially after it was hit by a devastating outbreak of ] in the "]" of 1665. | |||

| {{Panorama | |||

| The relationship between the City and the Crown was very tense. During the ], 1642–1651, the City of London had been a stronghold of ], and the wealthy and economically dynamic capital still had the potential to be a threat to Charles II, as had been demonstrated by several Republican uprisings in London in the early 1660s. The City magistrates were of the generation that had fought in the Civil War, and could remember how Charles I's grab for ] had led to that national trauma.<ref>See Hanson, 85–88, for the Republican temper of London.</ref> They were determined to thwart any similar tendencies from his son, and when the Great Fire threatened the City, they refused the offers Charles made of soldiers and other resources. Even in such an emergency, the idea of having the unpopular Royal troops ordered into the City was political dynamite. By the time Charles took over command from the ineffectual Lord Mayor, the fire was already out of control. | |||

| {{Panorama simple | |||

| |image = Image:Panorama of London by Claes Van Visscher, 1616 no angels.jpg | |image = Image:Panorama of London by Claes Van Visscher, 1616 no angels.jpg | ||

| |fullwidth = 2555 | |fullwidth = 2555 | ||

| |fullheight = 290 | |fullheight = 290 | ||

| |caption = |

|caption = A ] in 1616 by ]. The ] on ] (far right) was a notorious death-trap in case of fire; much would be destroyed in a fire in 1633.<ref>{{cite web |title=Fire in the City |url=https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/london-metropolitan-archives/the-collections/Pages/fire-in-the-city.aspx |publisher=City of London |date=23 August 2018 |access-date=13 December 2018 |archive-date=15 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181215225057/https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/london-metropolitan-archives/the-collections/Pages/fire-in-the-city.aspx |url-status=dead }}</ref> | ||

| |height = 240 | |height = 240 | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Wide image|1647_Long_view_of_London_From_Bankside_-_Wenceslaus_Hollar.jpg|1000px|''Long View of London from Bankside'', a ] by ], 1647, notable for being rendered all from one viewpoint}} | |||

| ===Fire hazards in the City=== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The City was essentially medieval in its street plan, an overcrowded warren of narrow, winding, cobbled alleys. It had experienced ], the most recent in 1632. Building with wood and roofing with ] had been prohibited for centuries, but these cheap materials continued to be used.<ref>Hanson, 77–80. The section "Fire hazards in the City" is based on Hanson 77–101 unless otherwise indicated.</ref> The only major stone-built area was the wealthy centre of the City, where the mansions of the merchants and brokers stood on spacious lots, surrounded by an inner ring of overcrowded poorer ]es whose every inch of building space was used to accommodate the rapidly growing population. These parishes contained workplaces, many of which were fire hazards—], ], ]s—which were theoretically illegal in the City, but tolerated in practice. The human habitations mixed in with these sources of heat, sparks, and pollution were crowded to bursting-point and designed with uniquely risky features. "]" (projecting upper floors) were characteristic of the typical six- or seven-storey timbered London ] houses. These buildings had a narrow footprint at ground level, but would maximise their use of a given land plot by "encroaching", as a contemporary observer put it, on the street with the gradually increasing size of their upper storeys. The fire hazard posed when the top jetties all but met across the narrow alleys was well perceived—"as it does facilitate a conflagration, so does it also hinder the remedy", wrote one observer<ref>Rege Sincera (pseudonym), ''Observations both Historical and Moral upon the Burning of London, September 1666'', quoted by Hanson, 80.</ref>—but "the covetousness of the citizens and connivancy of ]s" worked in favour of jetties. In 1661, Charles II issued a proclamation forbidding overhanging windows and jetties, but this was largely ignored by the local government. Charles' next, sharper, message in 1665 warned of the risk of fire from the narrowness of the streets and authorised both imprisonment of recalcitrant builders and demolition of dangerous buildings. It too had little impact. | |||

| The riverfront was a key area for the development of the Great Fire. The Thames offered water for the firefighting effort and hope of escape by boat, but, with stores and cellars of combustibles, the poorer districts along the riverfront presented the highest conflagration risk of any. All along the wharves, the rickety wooden tenements and ] shacks of the poor were shoehorned amongst "old paper buildings and the most combustible matter of ]r, ], ], ], and ] which was all layd up thereabouts."<ref>Letter from an unknown correspondent to ], September 1666, quoted by Tinniswood, 45–46.</ref> London was also full of ], especially along the riverfront. Much of it was left in the homes of private citizens from the days of the English Civil War, as the former members of ]'s ] still retained their ] and the powder with which to load them. Five to six hundred tons of powder were stored in the Tower of London at the north end of ]. The ]s along the wharves also held large stocks, stored in wooden barrels. | |||

| London Bridge, the only physical connection between the City and the south side of the river Thames, was itself covered with houses and had been noted as a deathtrap in the fire of 1632. By Sunday's dawn these houses were burning, and ], observing the conflagration from the Tower of London, recorded great concern for friends living on the bridge.<ref>All quotes from and details involving Samuel Pepys come from his diary entry for the day referred to.</ref> There were fears that the flames would cross London Bridge to threaten the ] of ] on the south bank, but this danger was averted by an open space between buildings on the bridge which acted as a ].<ref>Robinson, Bruce, </ref> | |||

| The 18-foot (5.5 m) high Roman wall enclosing the City put the fleeing homeless at risk of being shut into the inferno. Once the riverfront was on fire and the escape route by boat cut off, the only way out was through the eight gates in the wall. During the first couple of days, few people had any notion of fleeing the burning City altogether: they would remove what they could carry of belongings to the nearest "safe house", in many cases the parish church, or the precincts of St. Paul's Cathedral, only to have to move again hours later. Some moved their belongings and themselves "four and five times" in a single day.<ref>Gough MSS London14, the ], quoted by Hanson, 123.</ref> The perception of a need to get beyond the walls only took root late on the Monday, and then there were near-panic scenes at the narrow gates as distraught refugees tried to get out with their bundles, carts, horses, and wagons. | |||

| The crucial factor in frustrating firefighting efforts was the narrowness of the streets. Even under normal circumstances, the mix of carts, wagons, and pedestrians in the undersized alleys was subject to frequent traffic jams and gridlock. During the fire, the passages were additionally blocked by refugees camping in them amongst their rescued belongings, or escaping outwards, away from the centre of destruction, as demolition teams and fire engine crews struggled in vain to move in towards it. | |||

| === Fire hazards in the city === | |||

| ===Seventeenth-century firefighting=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] in ], England, 1612.]] | |||

| ] on wheels: "These Engins, (which are the best) to quinch great Fire; are made by John Keeling in ] (after many years' Experience)."]] | |||

| Fires were common in the crowded wood-built city with its open fireplaces, candles, ovens, and stores of combustibles. There was no police or fire department to call, but London's local ], known as the Trained Bands or ], was at least in principle available for general emergencies, and watching for fire was one of the jobs of ], a thousand watchmen or "bellmen" who patrolled the streets at night.<ref>Hanson, 82. The section "Fire hazards in the City" is based on Tinniswood, 46–52, and Hanson, 75–78 unless otherwise indicated.</ref> Self-reliant community procedures for dealing with fires were in place, and were usually effective. Public-spirited citizens would be alerted to a dangerous house fire by muffled peals on the church bells, and would congregate hastily to use the available techniques, which relied on demolition and water. By law, the tower of every ] church had to hold equipment for these efforts: long ladders, leather buckets, axes, and "firehooks" for pulling down buildings (see illustration right).<ref>A firehook was a heavy pole perhaps {{convert|30|ft|m|0}} long with a strong hook and ring at one end, which would be attached to the roof trees of a threatened house and operated by means of ropes and pulleys to pull the building down. (Tinniswood, 49).</ref> Sometimes taller buildings were levelled to the ground quickly and effectively by means of controlled gunpowder explosions. This drastic method for creating firebreaks was increasingly used towards the end of the Great Fire, and modern historians believe it was what finally won the struggle.<ref>Reddaway, 25.</ref> | |||

| Demolishing the houses downwind of a dangerous fire by means of firehooks or explosives was often an effective way of containing the destruction. This time, however, demolition was fatally delayed for hours by the ]'s lack of leadership and failure to give the necessary orders.<ref>"Bludworth's failure of nerve was crucial" (Tinniswood, 52).</ref> By the time orders came directly from the King to "spare no houses", the fire had devoured many more houses, and the demolition workers could no longer get through the crowded streets. | |||

| The city was essentially medieval in its street plan, an overcrowded warren of narrow, winding, cobbled alleys.<ref>Hanson, 78–79</ref> It had experienced several major fires before 1666, the most recent in 1633.<ref>Hanson, 82–83</ref> Building with wood and roofing with ] had been prohibited for centuries, but these cheap materials continued to be used.<ref>Hanson, 77–80. The section "Fire hazards in the City" is based on Hanson, 77–101 unless otherwise indicated.</ref> The only major area built with brick or stone was the wealthy centre of the city, where the mansions of the merchants and brokers stood on spacious lots, surrounded by an inner ring of overcrowded poorer parishes, in which all available building space was used to accommodate the rapidly growing population.<ref>Hanson, 80</ref><ref>{{cite book|page=69|title=Robert Hooke and the Rebuilding of London|last=Cooper|first=Michael|publisher=The History Press|year=2013|isbn=978-0-7524-9485-2}}</ref> | |||

| The use of water to extinguish the fire was also frustrated. In principle, water was available from a system of ] pipes which supplied 30,000 houses via a high ] at ], filled from the river at high tide, and also via a reservoir of Hertfordshire spring water in ].<ref>See Robinson, and Tinniswood, 48–49.</ref> It was often possible to open a pipe near a burning building and connect it to a hose to play on a fire, or fill buckets. Additionally, Pudding Lane was close to the river itself. Theoretically, all the lanes up to the bakery and adjoining buildings from the river should have been manned with double rows of firefighters passing full buckets up to the fire and empty buckets back down to the river. This did not happen, or at least was no longer happening by the time Pepys viewed the fire from the river at mid-morning on the Sunday. Pepys comments in his diary on how nobody was trying to put it out, but instead fleeing from it in fear, hurrying "to remove their goods, and leave all to the fire." The flames crept towards the riverfront with little interference from the overwhelmed community and soon torched the flammable warehouses along the wharves. The resulting conflagration not only cut off the firefighters from the immediate water supply of the river, but also set alight the ]s under London Bridge which pumped water to the Cornhill water tower; the direct access to the river and the supply of piped water failed together. | |||

| London possessed advanced fire-fighting technology in the form of ]s, which had been used in earlier large-scale fires. However, unlike the useful firehooks, these large pumps had rarely proved flexible or functional enough to make much difference. Only some of them had wheels, others were mounted on wheelless sleds.<ref>Compare Hanson, who claims they had wheels (76), and Tinniswood, who states they did not (50).</ref> They had to be brought a long way, tended to arrive too late, and, with spouts but no delivery hoses, had limited reach.<ref>The fire engines, for which a patent had been granted in 1625, were single-acting ]s worked by long handles at the front and back (Tinniswood, 50).</ref> On this occasion an unknown number of fire engines were either wheeled or dragged through the streets, some from across the City. The piped water that they were designed for had already failed, but parts of the river bank could still be reached. As gangs of men tried desperately to manoeuvre the engines right up to the river to fill their reservoirs, several of the engines toppled into the Thames. The heat from the flames was by then too great for the remaining engines to get within a useful distance; they could not even get into Pudding Lane. | |||

| The human habitations were crowded, and their design increased the fire risk. The typical multistorey timbered London ] houses had "]" (projecting upper floors). They had a narrow footprint at ground level, but maximised their use of land by "encroaching" on the street with the gradually increasing size of their upper storeys.<ref>Hanson, 80</ref> The fire hazard was well perceived when the top jetties all but met across the narrow alleys—"as it does facilitate a conflagration, so does it also hinder the remedy", wrote one observer.<ref>Rege Sincera (pseudonym), ''Observations both Historical and Moral upon the Burning of London, September 1666'', quoted by Hanson, 80</ref> In 1661, Charles II issued a proclamation forbidding overhanging windows and jetties, but this was largely ignored by the local government. Charles's next, sharper message in 1665 warned of the risk of fire from the narrowness of the streets and authorised both imprisonment of recalcitrant builders and demolition of dangerous buildings. It too had little impact.<ref>Hanson, 79</ref> | |||

| ==Development of the fire== | |||

| The personal experiences of many Londoners during the fire are glimpsed in letters and memoirs. The two most famous diarists of the ], ] (1633–1703) and ] (1620–1706), recorded the events and their own reactions day by day, and made great efforts to keep themselves informed of what was happening all over the City and beyond. For example, they both travelled out to the ] park area north of the City on the Wednesday—the fourth day—to view the mighty encampment of distressed refugees there, which shocked them. Their diaries are the most important sources for all modern retellings of the disaster. The most recent books on the fire, by Tinniswood (2003) and Hanson (2001), also rely on the brief ] of ] (1651–82), who was a fourteen-year-old schoolboy at ] in 1666. | |||

| The riverfront was important in the development of the Great Fire. The Thames offered water for firefighting and the chance of escape by boat, but the poorer districts along the riverfront had stores and cellars of combustibles which increased the fire risk. All along the wharves, the rickety wooden tenements and ] shacks of the poor were shoehorned amongst "old paper buildings and the most combustible matter of tarr, pitch, hemp, rosen, and flax which was all layd up thereabouts".<ref>Letter from an unknown correspondent to ], September 1666, quoted by Tinniswood, 45–46</ref><ref name=garrioch>{{cite journal|doi=10.1017/S0018246X15000382|title=1666 and London's fire history: a re-evalulation|journal=The Historical Journal|last=Garrioch|first=David|year=2016|volume=59|issue=2|pages=319–338|doi-access=free}}</ref> London was also full of ], especially along the riverfront where ] filled wooden barrels with their stocks. Much of it was left in the homes of private citizens from the days of the English Civil War. Five to six hundred tons of powder was stored in the ].<ref>Hanson, 101</ref> | |||

| After two rainy summers in 1664 and 1665, London had lain under an exceptional ] since November 1665, and the wooden buildings were tinder-dry after the long hot summer of 1666. The bakery fire in Pudding Lane spread at first due west, fanned by an eastern ]. | |||

| The high Roman wall enclosing the city impeded escape from the inferno, restricting exit to eight narrow gates. During the first couple of days, few people had any notion of fleeing the burning city altogether. They would remove what they could carry of their belongings to a safer area; some moved their belongings and themselves "four and five times" in a single day.<ref>Gough MSS London14, the ], quoted by Hanson, 123</ref> The perception of a need to get beyond the walls took root only late on the Monday, and then there were near-panic scenes at the gates as distraught refugees tried to get out with their bundles, carts, horses, and wagons.<ref>Hanson, 157–158</ref> | |||

| ===Sunday=== | |||

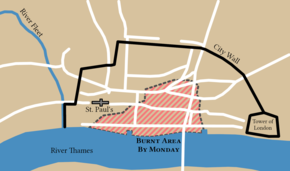

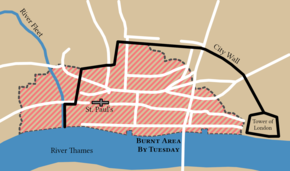

| ].<ref>The information in the day-by-day maps comes from Tinniswood, 58, 77, 97.</ref>]] | |||

| ] (1633–1703) painted by ] in 1666, the year of the Great Fire.]] | |||

| A fire broke out at Thomas Farriner's bakery in Pudding Lane a little after midnight on Sunday, ]. The family was trapped upstairs, but managed to climb from an upstairs window to the house next door, except for a maidservant who was too frightened to try, and became the first victim.<ref>Tinniswood 42–43.</ref> The neighbours tried to help douse the fire; after an hour the ]s arrived and judged that the adjoining houses had better be demolished to prevent further spread. The householders protested, and the ] Sir ], who alone had the authority to override their wishes, was summoned. When Bloodworth arrived, the flames were consuming the adjoining houses and creeping towards the paper warehouses and flammable stores on the riverfront. The more experienced firefighters were clamoring for demolition, but Bloodworth refused, on the argument that most premises were rented and the owners could not be found. Bloodworth is generally thought to have been appointed to the office of Lord Mayor as a ], rather than for any of the needful capabilities for the job; he panicked when faced with a sudden emergency.<ref>Tinniswood, 44: "He didn't have the experience, the leadership skills or the natural authority to take charge of the situation."</ref> Pressed, he made the often-quoted remark "Pish! A woman could piss it out", and left. After the City had been destroyed, Samuel Pepys, looking back on the events, wrote in his diary on ] ]: "People do all the world over cry out of the simplicity of my Lord Mayor in general; and more particularly in this business of the fire, laying it all upon him." | |||

| The crucial factor which frustrated firefighting efforts was the narrowness of the streets. Even under normal circumstances, the mix of carts, wagons, and pedestrians in the undersized alleys was subject to frequent ] and accidents.<ref>Hanson, 78–79</ref> Refugees escaping outwards, away from the centre of destruction, were blocked by soldiers trying to keep the streets clear for firefighters, causing further panic.<ref>Hanson, 156</ref> | |||

| Around 7 a.m. on Sunday morning, Pepys, who was a significant official in the ], climbed the Tower of London to get an aerial view of the fire, and recorded in his diary that the eastern gale had turned it into a conflagration. It had burned down several churches and, he estimated, 300 houses, and reached the riverfront. The houses on London Bridge were burning. Taking a boat to inspect the destruction around Pudding Lane at close range, Pepys describes a "lamentable" fire, "everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into ] that layoff; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another." Pepys continued westward on the river to the court at ], "where people come about me, and did give them an account dismayed them all, and word was carried in to the King. So I was called for, and did tell the King and Duke of Yorke what I saw, and that unless his Majesty did command houses to be pulled down nothing could stop the fire. They seemed much troubled, and the King commanded me to go to my Lord Mayor from him, and command him to spare no houses, but to pull down before the fire every way." Charles' brother ], offered the use of the ] to help fight the fire.<ref>Pepys' diary, ] ].</ref> | |||

| === 17th-century firefighting === | |||

| A mile west of Pudding Lane, by ], young William Taswell, a schoolboy who had bolted from the early morning service in ], saw some refugees arrive in for-hire lighter boats, unclothed and covered only with blankets.<ref>Tinniswood, 93.</ref> The services of the lightermen had suddenly become extremely expensive, and only the luckiest refugees secured a place in a boat. | |||

| ] in Devon, England, 1612.]] | |||

| Fires were common in the crowded wood-built city with its open fireplaces, candles, ovens, and stores of combustibles. A thousand ] or "bellmen" who patrolled the streets at night watched for fire as one of their duties.<ref>Hanson, 81. The section "17th-century firefighting" is based on Tinniswood, 46–52, and Hanson, 75–78, unless otherwise indicated.</ref> Self-reliant community procedures were in place for dealing with fires, and they were usually effective. "Public-spirited citizens" would be alerted to a dangerous house fire by muffled peals on the church bells, and would congregate hastily to fight the fire.<ref>Tinniswood, 48</ref> | |||

| The fire spread quickly in the high wind. By mid-morning on Sunday, people abandoned attempts at extinguishing the fire and fled; their moving human mass and their bundles and carts made the lanes impassable for firefighters and carriages. Pepys took a coach back into the city from Whitehall, but only reached St. Paul's Cathedral before he had to get out and walk. Handcarts with goods and pedestrians were still on the move, away from the fire, heavily weighed down. The parish churches not directly threatened were filling up with furniture and valuables, which would soon have to be moved further afield. Pepys found Mayor Bloodworth trying to coordinate the firefighting efforts and near collapse, "like a fainting woman", crying out plaintively in response to the King's message that he ''was'' pulling down houses. "But the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it." Holding on to his civic dignity, he refused James' offer of soldiers and then went home to bed.<ref>Tinniswood, 53.</ref> Charles sailed down from Whitehall in the Royal barge to inspect the scene. He found that houses still were not being pulled down in spite of Bloodworth's assurances to Pepys, and daringly overrode the authority of Bloodworth to order wholesale demolitions west of the fire zone.<ref>'']'', ] ].</ref> The delay rendered these measures largely futile, as the fire was already out of control. | |||

| The firefighting methods relied on demolition and water. By law, every parish church had to hold equipment for these efforts: long ladders, leather buckets, axes, and "firehooks" for pulling down buildings.<ref>Hanson, 77</ref>{{efn|A firehook was a heavy pole perhaps {{convert|30|ft|m|0}} long with a strong hook and ring at one end, which would be attached to the roof trees of a threatened house and operated by means of ropes and pulleys to pull down the building.<ref>Tinniswood, 49</ref>}} Sometimes buildings were levelled quickly and effectively by means of controlled gunpowder explosions. This drastic method of creating firebreaks was increasingly used towards the end of the Great Fire, and modern historians believe that this in combination with the wind dying down was what finally won the struggle.<ref>Reddaway, 25</ref><ref>Field, 19</ref> Demolishing the houses downwind of a dangerous fire was often an effective way of containing the destruction by means of firehooks or explosives. This time, however, demolition was fatally delayed for hours by the Lord Mayor's lack of leadership and failure to give the necessary orders.<ref>"Bludworth's failure of nerve was crucial" (Tinniswood, 52).</ref> | |||

| By Sunday afternoon, 18 hours after the alarm was raised in Pudding Lane, the fire had become a raging ] which created its own weather. A tremendous uprush of hot air above the flames was driven by the ] wherever constrictions such as jettied buildings narrowed the air current and left a ] at ground level. The resulting strong inward winds did not tend to put the fire out, as might be thought;<ref>See ] and Hanson, 102–105.</ref> instead, they added fresh ] to the flames, and the ] created by the uprush made the wind veer erratically both north and south of the main, easterly, direction of the gale which was still blowing. | |||

| The use of water to extinguish the fire was frustrated. In principle, water was available from a system of ] pipes which supplied 30,000 houses via a high ] at ], filled from the river at high tide, and also via a reservoir of Hertfordshire spring water in ].<ref>Tinniswood, 48–49</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Robinson |first=Bruce |author-link=Bruce Robinson |title=London: Brighter Lights, Bigger City |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/brighter_lights_01.shtml|accessdate=12 August 2006 |publisher=BBC }}</ref> It was often possible to open a pipe near a burning building and connect it to a hose to spray on a fire or fill buckets. Further, the site where the fire started was close to the river: all the lanes from the river up to the bakery and adjoining buildings should have been filled with double chains of firefighters passing buckets of water up to the fire and then back down to the river to be refilled.<ref>Tinniswood, 48–49</ref> This did not happen, as inhabitants panicked and fled. The flames crept towards the riverfront and set alight the ]s under ], eliminating the supply of piped water.<ref name=tin-52>Tinniswood, 52</ref> | |||

| In the early evening, with his wife and some friends, Pepys went again on the river "and to the fire up and down, it still encreasing." They ordered the boatman to go "so near the fire as we could for smoke; and all over the Thames, with one's face in the wind, you were almost burned with a shower of firedrops." When the "firedrops" became unbearable, the party went on to an ] on the south bank and stayed there till darkness came and they could see the fire on London Bridge and across the river, "as only one entire arch of fire from this to the other side of the bridge, and in a bow up the hill for an arch of above a mile long: it made me weep to see it." | |||

| London possessed advanced fire-fighting technology in the form of ]s, which had been used in earlier large-scale fires. However, unlike the useful firehooks, these large pumps had rarely proved flexible or functional enough to make much difference. Only some of them had wheels; others were mounted on wheelless sleds.<ref>Compare Hanson, who claims that they had wheels (76), and Tinniswood, who states that they did not (50).</ref> They had to be brought a long way, tended to arrive too late, and had limited reach, with spouts but no delivery hoses.{{efn|A patent had been granted in 1625 for the fire engines; they were single-acting ]s worked by long handles at the front and back.<ref>Tinniswood, 50</ref>}} On this occasion, an unknown number of fire engines were either wheeled or dragged through the streets. Firefighters tried to manoeuvre the engines to the river to fill their tanks, and several of the engines fell into the Thames. The heat from the flames by then was too great for the remaining engines to get within a useful distance.<ref name=tin-52 /> | |||

| ===Monday=== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ] (1620–1706) in 1651.]] | |||

| By dawn on Monday, ], the fire was principally expanding north and west, the turbulence of the firestorm pushing the flames both more to the south and more to the north than the day before.<ref>The section "Monday" is based on Tinniswood, 58–74, unless otherwise indicated.</ref> The push to the south was in the main halted by the river itself, but had torched the houses on London Bridge, and was threatening to cross the bridge and endanger the borough of ] on the south riverbank. Southwark was preserved by a pre-existent firebreak on the bridge, a long gap between the buildings which had saved the south side of the Thames in the fire of 1632 and now did so again.<ref>Robinson, .</ref> The corresponding push to the north drove the flames into the financial heart of the City. The houses of the bankers on ] began to burn on Monday afternoon, prompting a rush to get their stacks of gold coins, so crucial to the wealth of the city and the nation, to safety before they melted away. Several observers emphasise the despair and helplessness which seemed to seize the Londoners on this second day, and the lack of efforts to save the wealthy, fashionable districts which were now menaced by the flames, such as the ]—combined ] and shopping mall—and the opulent consumer goods shops in ]. The Royal Exchange caught fire in the late afternoon, and was a smoking shell within a few hours. John Evelyn, courtier and diarist, wrote: | |||

| == Development of the fire == | |||

| {{cquote|The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirred to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seen but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods, such a strange consternation there was upon them.<ref>All quotes from and details involving John Evelyn come from his diary.</ref>}} | |||

| === Sunday === | |||

| ] origin{{efn|name=Pudding}} is short vertical road in lower right damage area)|outline=gray}}<ref>The information in the day-by-day maps comes from Tinniswood, 58, 77, 97.</ref>]] | |||

| A fire broke out at ]'s bakery in ]{{efn|name=Pudding|Contemporary maps record the site as 23 Pudding Lane. The plot is now "within the roadway of Monument Street".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.countrylife.co.uk/country-life/where-the-great-fire-of-london-began-83288|website=Country Life|date=12 February 2016|title=Where the Great Fire of London began}}</ref>}} a little after midnight on Sunday 2 September. The family were trapped upstairs but managed to climb from an upstairs window to the house next door, except for a maidservant who was too frightened to try, thus becoming the first victim.<ref>Tinniswood, 42–43</ref> The neighbours tried to help douse the fire; after an hour, the ]s arrived and judged that the adjoining houses had better be demolished to prevent further spread. The householders protested, and ] Sir ] was summoned to give his permission.<ref>Tinniswood, 44</ref> | |||

| Evelyn lived four miles (6 km) outside the City, in ], and so did not see the early stages of the disaster. On Monday, joining many other upper-class people, he went by coach to Southwark to watch the view that Pepys had seen the day before, of the burning City across the river. The conflagration was much larger now: "the whole City in dreadful flames near the water-side; all the houses from the Bridge, all Thames-street, and upwards towards Cheapside, down to the Three Cranes, were now consumed."<ref>Evelyn, 10.</ref> In the evening, Evelyn reported that the river was covered with barges and boats making their escape piled with goods. He observed a great exodus of carts and pedestrians through the bottleneck City gates, making for the open fields to the north and east, "which for many miles were strewed with movables of all sorts, and tents erecting to shelter both people and what goods they could get away. Oh, the miserable and calamitous spectacle!" | |||

| When Bloodworth arrived, the flames were consuming the adjoining houses and creeping towards the warehouses and flammable stores on the riverfront. The more experienced firemen were clamouring for demolition, but Bloodworth refused on the grounds that most premises were rented and the owners could not be found. Bloodworth is generally thought to have been appointed to the office of Lord Mayor as a ], rather than by possessing requisite capabilities for the job. He panicked when faced with a sudden emergency and, when pressed, made the oft-quoted remark, "A woman might piss it out", and left.<ref>Hanson, 115</ref><ref>Tinniswood, 44: "He didn't have the experience, the leadership skills or the natural authority to take charge of the situation."</ref> Jacob Field notes that although Bloodworth "is frequently held culpable by contemporaries (as well as some later historians) for not stopping the Fire in its early stages... there was little could have done" given the state of firefighting expertise and the sociopolitical implications of antifire action at that time.<ref>Field, 12</ref> | |||

| ]–], with an account of the Great Fire. Click on the image to enlarge and read.]] | |||

| Suspicion soon arose in the threatened city that the fire was no accident. The swirling winds carried sparks and burning flakes long distances to lodge on thatched roofs and in wooden ]s, causing seemingly unrelated house fires to break out far from their source and giving rise to rumours that fresh fires were being set on purpose. Foreigners were immediately suspect due to the ongoing ]. As fear and suspicion hardened into certainty on the Monday, reports circulated of imminent ], and of foreign undercover agents seen casting "fireballs" into houses, or caught with hand grenades or matches.<ref>Hanson, 139.</ref> There was a wave of street violence.<ref>Reddaway, 22, 25.</ref> William Taswell saw a mob loot the shop of a French painter and level it to the ground, and watched in horror as a blacksmith walked up to a Frenchman in the street and hit him over the head with an iron bar. The fears of terrorism received an extra boost from the disruption of communications and news as vital facilities were devoured by the fire. The ] in ], through which post for the entire country passed, burned down early on Monday morning. The '']'' just managed to put out its Monday issue before the printer's premises went up in flames (this issue contained mainly society gossip, with a small note about a fire that had broken out on Sunday morning and "which continues still with great violence"). The whole nation depended on these communications, and the void they left filled up with rumours. There were also religious alarms of renewed ]s. As suspicions rose to panic and collective paranoia on the Monday, both the Trained Bands and the Coldstream Guards focused less on firefighting and more on rounding up foreigners, Catholics, and any odd-looking people, arresting them, rescuing them from mobs, or both together. | |||

| ], 1666]] | |||

| The inhabitants, especially the upper class, were growing desperate to remove their belongings from the City. This provided a source of income for the able-bodied poor, who hired out as porters (sometimes simply making off with the goods), and especially for the owners of carts and boats. Hiring a cart had cost a couple of ]s on the Saturday before the fire; on the Monday it rose to as much as forty pounds, a small fortune (equivalent to over £4000 in 2005).<ref>Hanson, 156–57.</ref> Seemingly every cart and boat owner within reach of London made their way towards the City to share in these opportunities, the carts jostling at the narrow gates with the panicked inhabitants trying to get out. The chaos at the gates was such that the magistrates ordered the gates shut on Monday afternoon, in the hope of turning the inhabitants' attention from safeguarding their own possessions to the fighting of the fire: "that, no hopes of saving any things left, they might have more desperately endeavoured the quenching of the fire."<ref>Quoted by Hanson, 158.</ref> This headlong and unsuccessful measure was rescinded the next day. | |||

| ] ascended the Tower of London on Sunday morning to view the fire from the battlements. He recorded in his diary that the eastern gale had turned it into a conflagration. It had burned down an estimated 300 houses and reached the riverfront. The houses on London Bridge were burning. He took a boat to inspect the destruction around Pudding Lane at close range and describes a "lamentable" fire, "everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into ] that lay off; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another." Pepys continued westward on the river to the court at ], "where people come about me, and did give them an account dismayed them all, and the word was carried into the King. So I was called for, and did tell the King and Duke of Yorke what I saw, and that unless His Majesty did command houses to be pulled down nothing could stop the fire. They seemed much troubled, and the King commanded me to go to my Lord Mayor from him and command him to spare no houses, but to pull down before the fire every way." Charles' brother ], offered the use of the ] to help fight the fire.<ref>Pepys' diary, 2 September 1666</ref><ref>Tinniswood, 45–46, 53</ref> | |||

| Even as order in the streets broke down, especially at the gates, and the fire raged unchecked, Monday marked the beginning of organised action. Bloodworth, who as Lord Mayor was responsible for coordinating the fire-fighting, had apparently left the City; his name is not mentioned in any contemporary accounts of the Monday events.<ref>Tinnisworth, 71.</ref> In this state of emergency, Charles again overrode the City authorities and put his brother ], in charge of operations. James set up command posts round the perimeter of the fire, ] any men of the lower classes found in the streets into teams of well-paid and well-fed firefighters. Three courtiers were put in charge of each post, with authority from Charles himself to order demolitions. This visible gesture of solidarity from the Crown was intended to cut through the citizens' misgivings about being held financially responsible for pulling down houses. James and his life guards rode up and down the streets all Monday, rescuing foreigners from the mob and attempting to keep order. "The Duke of York hath won the hearts of the people with his continual and indefatigable pains day and night in helping to quench the Fire", wrote a witness in a letter on ].<ref>Spelling modernised for clarity; quoted by Tinniswood, 80.</ref> | |||

| The fire spread quickly in the high wind and, by mid-morning on Sunday, people abandoned attempts at extinguishing it and fled. The moving human mass and their bundles and carts made the lanes impassable for firemen and carriages. Pepys took a coach back into the city from Whitehall, but reached only St Paul's Cathedral before he had to get out and walk. Pedestrians with handcarts and goods were still on the move away from the fire, heavily weighed down. They deposited their valuables in parish churches away from the direct threat of fire.<ref name=tin-53 /> | |||

| On the Monday evening, hopes that the massive stone walls of ], ], the western counterpart of the ], would stay the course of the flames were dashed and this historic royal palace was completely consumed, burning all night.<ref>Walter George Bell (1929) ''The Story of London's Great Fire'': 109-11. John Lane: London.</ref> | |||

| Pepys found Bloodworth trying to coordinate the fire-fighting efforts and near to collapse, "like a fainting woman", crying out plaintively in response to the King's message that he ''was'' pulling down houses: "But the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it." Holding on to his "dignity and civic authority", he refused James's offer of more soldiers and then went home to bed.<ref name=tin-53>Tinniswood, 53</ref> ] sailed down from Whitehall in the Royal barge to inspect the scene. He found that houses were still not being pulled down, in spite of Bloodworth's assurances to Pepys, and daringly overrode the authority of Bloodworth to order wholesale demolitions west of the fire zone.<ref>'']'', 3 September 1666</ref><ref>Tinniswood, 54–55</ref> | |||

| ===Tuesday=== | |||

| ]. The fire did not spread significantly on Wednesday, ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Tuesday, ], was the day of greatest destruction.<ref>The section "Tuesday" is based on Tinniswood, 77–96.</ref> The Duke of York's command post at ], at the conjunction of ] and ], was supposed to stop the fire's westward advance towards the Palace of Whitehall itself. Making a stand with his firefighters from the Fleet Bridge and down to the Thames, James hoped that the ] would form a natural firebreak. However, early on Tuesday morning, the flames jumped over the Fleet, driven by the unabated easterly gale, and outflanked them, forcing them to run for it. There was consternation at the palace as the fire continued implacably westward: "Oh, the confusion there was then at that court!" wrote Evelyn. | |||

| By Sunday afternoon, the fire had become a raging ] that created its own weather. A tremendous uprush of hot air above the flames was driven by the ] wherever constrictions narrowed the air current, such as the constricted space between ], and this left a ] at ground level. The resulting strong inward winds fueled the flames.<ref>See ] and Hanson, 102–05</ref> The fire pushed towards the city's centre "in a broad, bow-shaped arc".<ref>Tinniswood, 55</ref> By Sunday evening it "was already the most damaging fire to strike London in living memory", having travelled {{convert|500|m}} west along the river.<ref>Field, 14</ref> | |||

| Working to a plan at last, James' firefighters had also created a large firebreak to the north of the conflagration. It contained the fire until late afternoon, when the flames leaped across and began to destroy the wide, affluent luxury shopping street of ]. | |||

| === Monday === | |||

| Everybody had thought ] an absolute refuge, with its thick stone walls and natural firebreak in the form of a wide, empty surrounding plaza. It had been crammed full of rescued goods and its ] filled with the tightly packed stocks of the printers and booksellers in adjoining ]. However, in an enormous stroke of bad luck the building was covered in wooden scaffolding, awaiting restoration by ]. The scaffolding caught fire on Tuesday night. Leaving school, young William Taswell stood on Westminster Stairs a mile away and watched as the flames crept round the cathedral and the burning scaffolding ignited the timbered roof beams. Within half an hour, the ] roof was melting, and the books and papers in the crypt caught with a roar. "The stones of Paul's flew like ], the melting lead running down the streets in a stream, and the very pavements glowing with fiery redness, so as no horse, nor man, was able to tread on them", reported Evelyn in his diary. The cathedral was quickly a ruin. | |||

| ]'' for 3–10 September, facsimile front page with an account of the Great Fire]] | |||

| Throughout Monday, the fire spread to the west and north.<ref>Tinniswood, 72. The section "Monday" is based on Tinniswood, 58–74, unless otherwise indicated.</ref> The spread to the south was mostly halted by the river, but it had torched the houses on London Bridge and was threatening to cross the bridge and endanger the borough of ] on the south bank of the river. London Bridge, the only physical connection between the City and the south side of the river Thames, had been noted as a deathtrap in the fire of 1633.<ref>Hanson, 82–83</ref> However, Southwark was preserved by an open space between buildings on the bridge which acted as a firebreak.<ref>Field, 12</ref><ref name=rob-burning>{{cite web|last=Robinson|first= Bruce|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/great_fire_02.shtml |title=London's Burning: The Great Fire|publisher=BBC|year=2011|accessdate=8 December 2021}}</ref> | |||

| During the day, the flames began to move due ''east'' from the neighbourhood of Pudding Lane, straight against the prevailing east wind towards Pepys' home on ] and the Tower of London with its gunpowder stores. After waiting all day for requested help from James' official firefighters, who were busy in the west, the garrison at the Tower took matters into their own hands and created firebreaks by blowing up houses in the vicinity on a large scale, halting the advance of the fire. | |||

| The fire's spread to the north reached "the financial heart of the City".<ref name=han160 /> The houses of the bankers in ] began to burn on Monday afternoon, prompting a rush to rescue their stacks of gold coins before they melted.<ref>Tinniswood, 67</ref><ref name=han160>Hanson, 160</ref> Several observers emphasise the despair and helplessness which seemed to seize Londoners on this second day,<ref>Tinniswood, 63</ref> and the lack of efforts to save the wealthy, fashionable districts which were now menaced by the flames, such as the ]—combined ] and shopping centre<ref>Tinniswood, 3</ref>—and the opulent consumer goods shops in ]. The Royal Exchange caught fire in the late afternoon, and was a "smoking shell" within a few hours.<ref>Tinniswood, 70, 72</ref><ref>Hanson, 164</ref> ], courtier and diarist, wrote: | |||

| ===Wednesday=== | |||

| ].]] The wind dropped on Tuesday evening, allowing the firebreaks created by the garrison to finally begin to take effect on Wednesday, ].<ref>The section "Wednesday" is based on Tinniswood, 101–10, unless otherwise indicated.</ref> Pepys walked all over the smouldering city, getting his feet hot, and climbed the ] of ], from which he viewed the destroyed City, "the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw." There were many individual fires still burning themselves out, but the Great Fire was over. Pepys visited ], a large public park immediately north of the City, and saw a great encampment of homeless refugees, "poor wretches carrying their good there, and every body keeping his goods together by themselves", and noted that the price of bread in the environs of the park had doubled. Evelyn also went out to Moorfields, which was turning into the main point of assembly for the homeless, and was horrified at the numbers of distressed people filling it, some under tents, others in makeshift shacks: "Many without a rag or any necessary utensils, bed or board... reduced to extremest misery and poverty."<ref>Quoted Tinniswood, 104.</ref> Evelyn was impressed by the pride of these distressed Londoners, "tho' ready to perish for hunger and destitution, yet not asking one pennie for relief." | |||

| {{cquote|The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirred to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seen but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods, such a strange consternation there was upon them.<ref>All quotes from and details involving John Evelyn come from his '']''.</ref>}} | |||

| Fears of foreign terrorists and of a French and Dutch invasion were as high as ever among the traumatised fire victims, and on Wednesday night there was an outbreak of general panic at the encampments at ], Moorfields and ]. A light in the sky over Fleet Street started a story that 50,000 French and Dutch immigrants, widely rumoured to have started the fire, had risen and were marching towards Moorfields to finish what the fire had begun: to cut the men's throats, rape the women, and steal their few possessions. Surging into the streets, the frightened mob fell on any foreigners they happened to encounter, and were, according to Evelyn, only "with infinite pains and great difficulty" appeased and pushed back into the fields by the Trained Bands, troops of Life Guards, and members of the court. The mood was now so volatile that Charles feared a full-scale London rebellion against the monarchy. Food production and distribution had been disrupted to the point of non-existence, and Charles announced that supplies of bread would be brought into the City every day, and safe markets set up round the perimeter. These markets were for buying and selling; there was no question of distributing emergency aid. | |||

| Evelyn lived in ], four miles (6 km) outside the City, and so he did not see the early stages of the disaster. He went by coach to Southwark on Monday, joining many other upper-class people, to see the view which Pepys had seen the day before of the burning City across the river. The conflagration was much larger now: "the whole City in dreadful flames near the water-side; all the houses from the Bridge, all Thames-street, and upwards towards Cheapside, down to the Three Cranes, were now consumed".<ref name="Ev10">Evelyn, 10</ref> In the evening, Evelyn reported that the river was covered with barges and boats making their escape piled with goods. He observed a great exodus of carts and pedestrians through the bottleneck City gates, making for the open fields to the north and east, "which for many miles were strewed with moveables of all sorts, and tents erecting to shelter both people and what goods they could get away. Oh, the miserable and calamitous spectacle!"<ref name="Ev10" /> | |||

| ==Deaths and destruction== | |||

| ] published in 1666 giving an account of the fire, and of the limits of its destruction. Click on the image to enlarge and read.]] | |||

| Only a few deaths from the fire are officially recorded, and actual deaths are also traditionally supposed to have been few. Porter gives the figure as eight<ref>Porter, 87.</ref> and Tinniswood as "in single figures", although he adds that some deaths must have gone unrecorded and that, besides direct deaths from burning and ], refugees also perished in the impromptu camps.<ref>Tinniswood, 131–35.</ref> Hanson takes issue with the whole notion that there were only a few deaths, enumerating known deaths from hunger and ] among survivors of the holocaust, "huddled in shacks or living among the ruins that had once been their homes" in the cold winter that followed, including, for instance, the dramatist ] and his wife. Hanson also maintains that "it stretches credulity to believe that the only ]s or foreigners being beaten to death or lynched were the ones rescued by the Duke of York", that official figures say very little about the fate of the undocumented poor, and that the heat at the heart of the firestorms, far higher than the heat of an ordinary house fire, was sufficient to fully consume bodies, or leave only a few skull fragments. The fire, fed not merely by wood, fabrics, and thatch, but also by the oil, pitch, coal, tallow, fats, sugar, alcohol, turpentine, and gunpowder stored in the riverside district, melted the imported ] lying along the wharves (] between 1,250 °C (2,300 F) and 1,480 °C (2,700 F)) and the great ] chains and locks on the City gates (melting point between 1,100 °C (2,000 F) and 1,650 °C (3000 F)). Nor would anonymous bone fragments have been of much interest to the hungry people sifting through the tens of thousands of tons of rubble and debris after the fire, looking for valuables, or to the workmen clearing away the rubble later for the rebuilding. Appealing to common sense and "the experience of every other major urban fire down the centuries", Hanson emphasises that the fire attacked the rotting tenements of the poor with furious speed, surely trapping at the very least "the old, the very young, the halt and the lame" and burying the dust and ashes of their bones under the rubble of cellars; making for a death toll not of four or eight, but of "several hundred and quite possibly several thousand."<ref>Hanson, 326–33.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The material destruction has been computed at 13,500 houses, 87 parish churches, 44 ] Halls, the ], the ], St. Paul's Cathedral, the ] and other City prisons, the ], and the three western city gates, ], ], and ].<ref>Porter, 87–88.</ref> The monetary value of the loss, first estimated at £100,000,000 in the currency of the time, was later reduced to an uncertain £10,000,000<ref>Reddaway, 26.</ref> (over £1,000,000,000 in 2005 pounds).<ref></ref> Evelyn believed that he saw as many as "200,000 people of all ranks and stations dispersed, and lying along their heaps of what they could save" in the fields towards ] and ].<ref>Reddaway, 26.</ref> | |||

| Suspicion soon arose in the threatened city that the fire was no accident.<ref>Tinniswood, 58</ref> The swirling winds carried sparks and burning flakes long distances to lodge on thatched roofs and in wooden ], causing seemingly unrelated house fires to break out far from their source and giving rise to rumours that fresh fires were being set on purpose. Foreigners were immediately suspected because of the ongoing ]. Fear and suspicion hardened into certainty on Monday, as reports circulated of imminent invasion and of foreign undercover agents seen casting "fireballs" into houses, or caught with hand grenades or matches.<ref>Hanson, 139</ref><ref>Tinniswood, 59</ref><ref>Field, 15</ref> There was a wave of street violence.<ref>Reddaway, 22, 25</ref> | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| The fears of terrorism received an extra boost from the disruption of communications and news. The ] in ], through which post passed for the entire country, burned down early on Monday morning. The '']'' just managed to put out its Monday issue before the printer's premises went up in flames.<ref>Tinniswood, 64–66</ref> Suspicions rose to panic and collective paranoia on Monday, and both the ] and the ] focused less on fire fighting and more on rounding up foreigners and anyone else appearing suspicious, arresting them, rescuing them from mobs, or both.<ref>Field, 15–16</ref><ref>Tinniswood, 58–63</ref> | |||

| An example of the urge to identify scapegoats for the fire is the acceptance of the confession of a simple-minded French watchmaker, ], who claimed he was an agent of the ] and had started the Great Fire in Westminster.<ref>The section "Aftermath" is based on Reddaway, 27 ff. and Tinniswood, 213–37, unless otherwise indicated.</ref> He later changed his story to say that he had started the fire at the bakery in Pudding Lane. Hubert was convicted, despite some misgivings about his ], and hanged at ] on ], ]. After his death, it became apparent that he had not arrived in London until two days after the fire started.<ref>Tinniswood, 163–68.</ref> These allegations that Catholics had started the fire were exploited as powerful political propaganda by opponents of pro-Catholic Charles II's court, mostly during the ] and the exclusion crisis later in his reign.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | last = Porter | first = Stephen | title = The great fire of London | encyclopedia = Oxford Dictionary of National Biography | publisher = ] | date = October 2006 | url = http://www.oxforddnb.com/public/themes/95/95647.html | accessdate = 2006-11-28 }}</ref> | |||

| The inhabitants, especially the upper class, were growing desperate to remove their belongings from the City.<ref>Tinniswood, 63–64</ref> This provided a source of income for the able-bodied poor, who hired out as porters (sometimes simply making off with the goods), being especially profitable for the owners of carts and boats. Hiring a cart had cost a couple of ]s the week before the fire; on Monday, it rose to as much as £40,<ref>Hanson, 156–157</ref> a fortune equivalent to roughly £133,000 in 2021.<ref>Using relative income. {{cite web|url=https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ukcompare/relativevalue.php|website=MeasuringWorth|accessdate=24 December 2021|title=Relative Values – UK £}}</ref> Seemingly every cart and boat owner in the area of London came to share in these opportunities, the carts jostling at the narrow gates with the panicked inhabitants trying to get out. The chaos at the gates was such that the magistrates briefly ordered the gates shut, in the hope of turning the inhabitants' attention from safeguarding their own possessions to fighting the fire: "that, no hopes of saving any things left, they might have more desperately endeavoured the quenching of the fire."<ref>Quoted by Hanson, 158</ref><ref>Tinniswood, 68</ref> | |||

| In the chaos and unrest after the fire, Charles II feared another London rebellion. He encouraged the homeless to move away from London and settle elsewhere, immediately issuing a proclamation that "all Cities and Towns whatsoever shall without any contradiction receive the said distressed persons and permit them the free exercise of their manual trades." A special Fire Court was set up to deal with disputes between tenants and landlords and decide who should rebuild, based on ability to pay. The Court was in session from February 1667 to September 1672. Cases were heard and a verdict usually given within a day, and without the Fire Court, lengthy legal wrangles would have seriously delayed the rebuilding which was so necessary if London was to recover. | |||

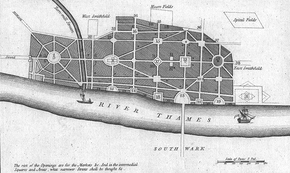

| Encouraged by Charles, radical rebuilding schemes for the gutted City poured in. If it had been rebuilt under these plans, London would have rivalled Paris in ] magnificence (see Evelyn's plan on the right). The Crown and the City authorities attempted to establish "to whom all the houses and ground did in truth belong" in order to negotiate with their owners about compensation for the large-scale re-modelling that these plans entailed, but that unrealistic idea had to be abandoned. Exhortations to bring workmen and measure the plots on which the houses had stood were mostly ignored by people worried about day-to-day survival, as well as by those who had left the capital; for one thing, with the shortage of labour following on the fire, it was impossible to secure workmen for the purpose. Apart from Wren and Evelyn, it is known that ], ] and ] proposed rebuilding plans. | |||

| Monday marked the beginning of organised action, even as order broke down in the streets, especially at the gates, and the fire raged unchecked. Bloodworth was responsible as Lord Mayor for coordinating the firefighting, but he had apparently left the City; his name is not mentioned in any contemporaneous accounts of the Monday's events.<ref>Tinniswood, 71</ref> In this state of emergency, the King put his brother James, Duke of York, in charge of operations. James set up command posts on the perimeter of the fire. Three courtiers were put in charge of each post, with authority from Charles himself to order demolitions. James and his life guards rode up and down the streets all Monday, "rescuing foreigners from the mob" and attempting to keep order.<ref>Tinniswood, 74–75</ref> "The Duke of York hath won the hearts of the people with his continual and indefatigable pains day and night in helping to quench the Fire," wrote a witness in a letter on 8 September.<ref>Spelling modernised for clarity; quoted by Tinniswood, 80</ref> | |||

| ]'s plan never carried out, for rebuilding a radically different ].]] | |||

| On Monday evening, hopes were dashed that the massive stone walls of ], ] would stay the course of the flames, the western counterpart of the ]. This historic royal palace was completely consumed, burning all night.<ref>Bell, 109–111</ref> | |||

| ].]]] | |||

| With the complexities of ownership unresolved, none of the grand Baroque schemes for a City of piazzas and avenues could be realised; there was nobody to negotiate with, and no means of calculating how much compensation should be paid. Instead, the old street plan was re-created in the new City, with improvements in hygiene and fire safety: wider streets, open and accessible wharves along the length of the Thames, with no houses obstructing access to the river, and, most importantly, buildings constructed of brick and stone, not wood. New public buildings were created on their predecessors' sites; perhaps the most famous is ] and its smaller cousins, ]. | |||

| === Tuesday === | |||

| On Charles' initiative, a ], designed by ] and ], was erected near Pudding Lane after the fire. Standing 61 metres tall and known simply as "The Monument", it is a familiar London landmark which has given its name to a ]. In 1668 accusations against the Catholics were added to the Monument which read, in part: | |||

| ] | |||

| ] in flames, with ] in the distance (square tower without the spire) now catching flames. Oil painting by anonymous artist, {{circa|1670}}.]] | |||

| Tuesday, 4 September was the day of greatest destruction.<ref>The section "Tuesday" is based on Tinniswood, 77–96, unless otherwise indicated.</ref> The Duke of York's command post at ], where ] meets ], was supposed to stop the fire's westward advance towards the Palace of Whitehall. He hoped that the ] would form a natural firebreak, making a stand with his firemen from the Fleet Bridge and down to the Thames. However, early on Tuesday morning, the flames jumped over the Fleet and outflanked them, driven by the unabated easterly gale, forcing them to run for it.<ref>Tinniswood, 75–77</ref><ref>Field, 16</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Here by permission of heaven, hell broke loose upon this Protestant city.....the most dreadful Burning of this City; begun and carried on by the treachery and malice of the Popish faction...Popish frenzy which wrought such horrors, is not yet quenched...}} | |||

| By mid-morning the fire had breached the wide affluent luxury shopping street of ].<ref>Tinniswood, 78</ref> James's firefighters created a large firebreak to the north of the conflagration,<ref>Tinniswood, 80</ref> although it was breached at multiple points.<ref>Tinniswood, 84</ref> Through the day, the flames began to move eastward from the neighbourhood of Pudding Lane, straight against the prevailing east wind and towards the Tower of London with its gunpowder stores.<ref>Tinniswood, 86</ref> The garrison at the Tower took matters into their own hands after waiting all day for requested help from James's official firemen, who were busy in the west. They created firebreaks by blowing up houses on a large scale in the vicinity, halting the advance of the fire.<ref>Tinniswood, 96</ref> | |||

| Aside from the four years of ]'s rule from 1685 to 1689, the inscription remained in place until 1830 and the passage of the ].<ref>{{cite web | last = Wilde | first = Robert | title = The Great Fire of London – 1666 | publisher = ] | url = http://europeanhistory.about.com/od/ukandireland/a/agreatfirelon_4.htm | accessdate = 2006-11-28 }}</ref> | |||

| Everybody had thought ] a safe refuge, with its thick stone walls and natural firebreak in the form of a wide empty surrounding plaza. It had been crammed full of rescued goods and its ] filled with the tightly packed stocks of the printers and booksellers in adjoining ]. However, the building was covered in wooden scaffolding, undergoing piecemeal restoration by ]. The scaffolding caught fire on Tuesday night. Within half an hour, the ] roof was melting, and the books and papers in the crypt were burning. The cathedral was quickly a ruin.<ref>Tinniswood, 91–95</ref><ref>Field, 17–18</ref> | |||

| Another monument, the ] in ], marks the spot where the fire stopped. According to the inscription, the fact that the fire started at Pudding Lane and stopped at Pye Corner was an indication that the Fire was evidence of God's wrath on the City of London for the sin of ]. | |||

| === Wednesday === | |||

| The ] epidemic of 1665 is believed to have killed a sixth of London's inhabitants, or 80,000 people,<ref>Porter, 84.</ref> and it is sometimes suggested, given the fact that plague epidemics did not recur in London after the fire,<ref>Hanson, 249–50.</ref> that the Great Fire saved lives in the long run by burning down so much unsanitary housing with the accompanying ]s and their ]s (which transmitted the plague). Historians disagree as to whether the fire played a part in preventing future major outbreaks. The ] website claims that there was a connection,<ref>, ], accessed ], ].</ref> while historian ] points out that the fire left the most insalubrious parts of London, the slum suburbs, untouched.<ref>"The plague-ravaged parts—extramural settlements like ], ], ], ] and ] that housed the most squalid slums—were, sadly, little touched by the Fire (burning down was what they needed)" (Porter, 80).</ref> Alternative ] explanations have been put forward, along with the observation that the disease disappeared from almost every other European city at the same time.<ref>Hanson, 249–50.</ref> | |||

| The wind dropped on Tuesday evening, and the firebreaks created by the garrison finally began to take effect on Wednesday, 5 September.<ref>The section "Wednesday" is based on Tinniswood, 101–110, unless otherwise indicated.</ref><ref>Field, 19</ref> Pepys climbed the ] of ], from which he viewed the destroyed City, "the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw".<ref>Quoted in Tinniswood, 101</ref> There were many separate fires still burning, but the Great Fire was over. It took some time until the last traces were put out: coal was still burning in cellars two months later.<ref>{{cite journal|title=1666 and London's fire history: A re-evaluation|journal=The Historical Journal|volume=59|issue=2|year=2016|pages=319–338|first=David |last=Garrioch|doi=10.1017/S0018246X15000382|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In ], a large public park immediately north of the City, there was a great encampment of homeless refugees. Evelyn was horrified at the numbers of distressed people filling it, some under tents, others in makeshift shacks: "Many without a rag or any necessary utensils, bed or board ... reduced to extremest misery and poverty."<ref>Quoted in Tinniswood, 104</ref> Most refugees camped in any nearby available unburned area to see if they could salvage anything from their homes.<ref>Tinniswood, 103</ref> The mood was now so volatile that Charles feared a full-scale London rebellion against the monarchy. Food production and distribution had been disrupted to the point of non-existence; Charles announced that supplies of bread would be brought into the City every day, and markets set up round the perimeter.<ref>Tinniswood, 105–107</ref> | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| Fears of foreign terrorists and of a French and Dutch invasion were as high as ever among the traumatised fire victims. There was panic on Wednesday night in the encampments at ], Moorfields, and Islington: a light in the sky over Fleet Street started a story that 50,000 French and Dutch immigrants had risen, and were marching towards Moorfields to murder and pillage. Surging into the streets, the frightened mob fell on any foreigners whom they happened to encounter, and were pushed back into the fields by the Trained Bands, troops of Life Guards, and members of the court.<ref>Tinniswood, 108–110</ref> The light turned out to be a flareup east of Inner Temple, large sections of which burned despite an effort to halt the fire by blowing up Paper House.<ref>Tinniswood, 111</ref> | |||

| ==References== | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Evelyn |first=John |authorlink=John Evelyn |title=Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, F.R.S. |url=http://books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC20137959&id=JiH6MSVCzmsC&pg=PA10&vq=fire&dq=%22John+evelyn%22+diary&as_brr=1 |accessdate=2006-11-05 |year=1854 |publisher=Hursst and Blackett |location=London}} Also in text version:{{cite book |last=Evelyn |first=John |authorlink=John Evelyn |title=Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, F.R.S. |url=http://nils.lib.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2000.01.0023;query=page%3D%2311;layout=;loc= |accessdate=2007-01-01 |year=1857 |ed=William Bray |location=London}} | |||

| == Deaths and destruction == | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Hanson |first=Neil |title=The Dreadful Judgement: The True Story of the Great Fire of London |year=2001 |month= |publisher=Doubleday |location=New York}} For a review of Hanson's work, see {{cite web |last=Lauzanne |first=Alain |title=Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone |publisher=Cercles |url=http://www.cercles.com/review/r1/hanson.html |accessdate=2006-10-12 |language=English}} | |||

| ] published in 1666 giving an account of the fire, and of the limits of its destruction]] | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Morgan |firs=Kenneth O. |year=2000 |title=Oxford Illustrated History of Britain |location=Oxford |publisher=Oxford}} | |||