| Revision as of 09:49, 11 August 2005 view source80.126.25.210 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:51, 7 January 2025 view source Morning star (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users3,209 edits added timeline template | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Founder of the Latter Day Saint movement (1805–1844)}} | |||

| {{:Joseph Smith, Jr./Infobox | | |||

| {{about|the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement|other persons|Joseph Smith (disambiguation)}} | |||

| English name= Joseph Smith| | |||

| {{pp|reason=Persistent ]|small=yes}} | |||

| image= ]| | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| birth_name= Joseph Smith, Jr.| | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| birth_date= ], ]| | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=September 2023}} | |||

| birthplace= ]| | |||

| {{Use shortened footnotes|date=June 2022}} | |||

| prophet_date= ], ] | | |||

| {{Infobox Latter Day Saint biography | |||

| founder_date= ], ] | | |||

| president_date= ], ] | | |||

| predecessor= Founder| | |||

| successor=see ]| | |||

| dead=dead|death_date=], ]| | |||

| deathplace=]|}} | |||

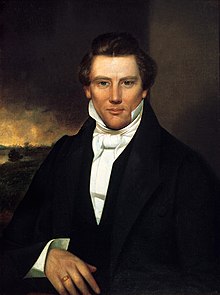

| | image = Joseph Smith, Jr. portrait owned by Joseph Smith III.jpg | |||

| '''Joseph Smith, Jr.''' (], ] – ], ]) was the founder and leader of the ].<!--*****NOTE TO EDITORS: Do not change this to read "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. There are many factions besides the LDS Church that follow Joseph Smith's teachings. "Latter Day Saint movement" should stand as is.*****--> His followers revere him as the first ] of the ]. Critics regarded him, his religion, and his politics with contempt sometimes resulting in violence: Smith and his brother ] were killed when a mob attacked the ] jail where the two were incarcerated. | |||

| | alt = Portrait of Joseph Smith Jr. | |||

| | caption = Portrait, {{circa|1842}} | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1805|12|23}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1844|06|27|1805|12|23}} | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | death_cause = ] | |||

| | resting_place = ],<br />], U.S. | |||

| | resting_place_coordinates = {{Coord|40.54052|-91.39244|type:landmark|display=inline|name=Smith Family Cemetery}} | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| * {{marriage|]|1827}} | |||

| * ]{{efn|name=Polygamy|{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=153}} notes the exact figure is debated. {{Harvtxt|Smith|1994|p=14}} counts 42 polygamous wives; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=587–88}} counts 46; {{Harvtxt|Compton|1997|p=11}} counts at least 33 total; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=437, 644}} accepts Compton's count, excepting one, resulting in a total of 32; {{Harvtxt|Davenport|2022|p=139}} counts 37.}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | children = {{hlist|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | parents = {{ubl|] (father)|] (mother)}} | |||

| | relatives = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] (brother) | |||

| * ] (brother) | |||

| * ] (brother) | |||

| * ] (brother) | |||

| * ] (sister) | |||

| * ] (brother) | |||

| * ] (sister) | |||

| }} | |||

| | signature = Joseph Smith Jr Signature.svg | |||

| | signature_size = 100px | |||

| | signature_alt = J Smith | |||

| <!-- Latter Day Saint Leadership --> | |||

| | position_or_quorum1 = 1st ] of the ]{{efn|Church of Christ was the official name on April 6, 1830.<ref>{{cite book |last=Shields |first=Steven |title=Divergent Paths of the Restoration |location=Independence, Missouri |publisher=Restoration Research |year=1990 |edition=fourth |isbn=0-942284-00-3}}</ref> In 1834, the official name was changed to ''Church of the Latter Day Saints''<ref>{{cite news |author=Joseph Smith |title=Minutes of a Conference |url=http://www.centerplace.org/history/ems/v2n20.htm |work=] |location=Kirtland, OH |page=160 |volume=2 |issue=20 |access-date=May 5, 2023}}</ref> and then in 1838 to ''Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints''. The spelling "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints" was adopted by the LDS Church in Utah in 1851, after Joseph Smith's death in 1844, and is today specified in ].<ref>{{cite web |title=D&C 115:4 |url=https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/dc-testament/dc/115.4?lang=eng}}</ref>}} | |||

| | successor1 = ]{{efn|], ], ], and ] each claimed succession.}} | |||

| | start_date1 = {{start date|1830|04|06}} | |||

| | end_date1 = {{end date|1844|06|27}} | |||

| | end_reason1 = ] | |||

| <!--Political Office Holders --> | |||

| | political_office1 = 2nd Mayor of ] | |||

| | term_start1 = {{start date|1842|05|19}}<ref name=Mayor>{{cite journal|last=Garr|first=Arnold K.|title=Joseph Smith: Mayor of Nauvoo|journal=Mormon Historical Studies|volume=1|issue=1|date=Spring 2002|url=http://mormonhistoricsites.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/MHS3.1Spring2002Garr.pdf|pages=5–6}}</ref> | |||

| | term_end1 = {{end date|1844|06|27}} | |||

| | office_predecessor1 = ] | |||

| | office_successor1 = Chancy Robison<ref>{{cite book|editor-last=Jenson|editor-first=Andrew|title=The Historical Record: A Monthly Periodical|location=Salt Lake City|page=843|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vPw8AAAAIAAJ|access-date=July 23, 2013|year=1888}}</ref> | |||

| | party = Independent | |||

| | portals = none | |||

| | known_for = Founding ]}} | |||

| {{Joseph Smith, Jr.|noimage=true}} | |||

| '''Joseph Smith Jr.''' (December 23, 1805{{spnd}}June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and the founder of ] and the ].<!--A number of churches claim Smith as their founder, so it is incorrect to assert that Smith is the founder only of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.--> Publishing the ] at the age of 24, Smith attracted tens of thousands of followers by the time of his death fourteen years later. The religion he founded is followed by millions of global adherents and several churches, the largest of which is ] (LDS Church). | |||

| Raised during an era of ] innovation, at the beginning of the ] movement, Smith built his ministry upon claims of ], ], visits from ]s, the discovery and translation of ancient writings, and the introduction of novel social, economic, and doctrinal ideas. Smith's call began, he later said, with a ], a ], in his adolescent years, where he received a forgiveness of his sins in a clearing of the woods near his home. Later, he claimed the influence of angels, who led him to restore what he claimed was the original ], as he believed it existed in the ]. | |||

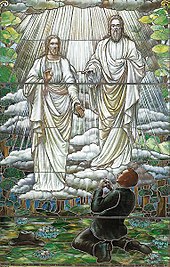

| Born in ], Smith moved with his family to ], following ] in 1816. Living in an area of intense religious revivalism during the ], Smith reported experiencing a series of visions. The ] was in 1820, when he saw "two personages" (whom he eventually described as ] and ]). In 1823, he said he was visited by ] who directed him to a buried book of ] inscribed with a Judeo-Christian history of an ancient American civilization. In 1830, Smith published the Book of Mormon, which he described as an English translation of those plates. The same year he organized the ], calling it a ] of the ]. Members of the church were later called "Latter Day Saints" or "Mormons". | |||

| Smith dictated numerous ]s, many of which he claimed were translated from ancient records, including the '']'' and the '']''. Smith also created his own ] of the '']'', and dictated many new revelations, many of which were later compiled and published as the '']''. | |||

| In 1831, Smith and his followers moved west, planning to build a ] ] in the American heartland. They first gathered in ], and established an outpost in ], which was intended to be Zion's "center place". During the 1830s, Smith sent out missionaries, published ], and supervised construction of the ]. Because of the collapse of the church-sponsored ], violent skirmishes with non-Mormon Missourians, and the ], Smith and his followers established a new settlement at ], of which he was the spiritual and political leader. In 1844, when the '']'' criticized Smith's power and his practice of ], Smith and the Nauvoo City Council ordered the destruction of its ], inflaming anti-Mormon sentiment. Fearing an invasion of Nauvoo, Smith rode to ], to stand trial, but ] by a mob that stormed the jailhouse. | |||

| In his later years, Smith attempted to form two utopian cities (] and ]), he commanded his own ], he married numerous wives ], he ran for ], and some of his followers anointed him as a king within the Kingdom of God. He had many loyal associates who were willing to give their life for him, and also many bitter, mortal enemies bent on his destruction. | |||

| During his ministry, Smith published numerous documents and texts, many of which he attributed to divine inspiration and revelation from ]. He dictated the majority of these in the first-person, saying they were the writings of ancient prophets or expressed the voice of God. His followers accepted his teachings as prophetic and revelatory, and several of these texts were ] by denominations of the Latter Day Saint movement, which continue to treat them as ]. Smith's teachings discuss God's nature, ], family structures, political organization, and religious community and authority. Mormons generally regard Smith as a prophet comparable to ] and ]. Several religious denominations identify as the continuation of the church that he organized, including the LDS Church and the ]. | |||

| Smith and his legacy continue to evoke strong emotion; his life and works are subject to considerable debate and research. ]s regard negative criticism as verification of a prophecy Smith gave at age thirty-four stating that seventeen years earlier he was told by an angel that his name and reputation "should be had for good and evil among all nations, kindreds, and tongues, or that it should be both good and evil spoken of among all people." | |||

| == |

==Life== | ||

| {{Template:Joseph Smith timeline}} | |||

| Smith was born in ], the fourth child of ] and ]. The Smiths suffered considerable financial problems and moved several times in and around ]. One of these moves was prompted by conditions incidental to the ]. | |||

| ===Early years (1805–1827)=== | |||

| {{Main|Early life of Joseph Smith}} | |||

| Joseph Smith was born on December 23, 1805, in ], on the border between the villages of ] and ], to ] and her husband ], a merchant and farmer.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=9, 30}}; {{Harvtxt|Smith|1832|p=1}}</ref> He was one of eleven children. At the age of seven, Smith had a bone infection and, after receiving surgery, used crutches for three years.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=21}}</ref> After an ill-fated business venture and three successive years of crop failures culminating in the 1816 ], the Smith family left Vermont and moved to ],<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=27–32}}</ref> and took out a mortgage on a {{convert|100|acre|ha|adj=on}} ] in the townships of ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Smith Family Log Home, Palmyra, New York |url=https://ensignpeakfoundation.org/smith-family-log-home/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221005104715/https://ensignpeakfoundation.org/smith-family-log-home/ |archive-date=October 5, 2022 |access-date=December 26, 2022 |website=Ensign Peak Foundation}}</ref> | |||

| The region was a ] during the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Martin |first=John H. |url=https://www.crookedlakereview.com/articles/136_150/137fall2005/137martin.html |title=Saints, Sinners and Reformers: The Burned-Over District Re-Visited |year=2005 |chapter=An Overview of the Burned-Over District |postscript=, |chapter-url=https://www.crookedlakereview.com/books/saints_sinners/martin1.html}} published in the .</ref><ref name=":7" /> Between 1817 and 1825, there were several camp meetings and revivals in the Palmyra area.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=36–37}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|p=136}}</ref> Smith's parents disagreed about religion, but the family was caught up in this excitement.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|p=xx}}; {{Harvtxt|Hill|1989|pp=10–11}}; {{Harvtxt|Brooke|1994|p=129}}</ref> Smith later recounted that he had become interested in religion by age 12, and as a teenager, may have been sympathetic to ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|pp=26–7}}; {{cite web |author=D. Michael Quinn |date=July 12, 2006 |title=Joseph Smith's Experience of a Methodist 'Camp-Meeting' in 1820 |url=https://www.dialoguejournal.com/articles/joseph-smiths-experience-of-a-methodist-camp-meeting-in-1820/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110927235221/http://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/QuinnPaperless.pdf |archive-date=September 27, 2011 |access-date=December 26, 2022 |website=Dialogue Paperless |page=3}}</ref> With other family members, he also engaged in ], a relatively common practice in that time and place.<ref>{{harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=30–31}}; {{harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=51}}; {{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|pp=7–8}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=16, 33}}; {{Harvtxt|Hill|1977|p=53}}</ref> Both his parents and his maternal grandfather reported having visions or dreams that they believed communicated messages from God.<ref>{{harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=14–16, 137}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=26, 36}}; {{Harvtxt|Brooke|1994|pp=150–51}}; {{Harvtxt|Mack|1811|p=25}}; {{Harvtxt|Smith|1853|pp=54–59, 70–74}}</ref> Smith said that, although he had become concerned about the welfare of his soul, he was confused by the claims of competing religious denominations.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=38–9}}; {{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|p=30}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|p=136}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=37}}</ref> | |||

| Smith had little formal schooling because he was needed at home on the farm. | |||

| Years later, Smith wrote that he had received ] that resolved his religious confusion.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=39}}; {{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|p=30}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|p=136}}</ref> He said that in 1820, while he had been praying in a ] near his home, ] and ] together appeared to him, told him his sins were forgiven, and said that all contemporary churches had "turned aside from the gospel".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=37–38}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=39}}; {{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|p=30}}</ref> Smith said he recounted the experience to a Methodist minister, who dismissed the story "with great contempt".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|p=30}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=40}}; {{Harvtxt|Harper|2019|p=9}}</ref> According to historian Steven C. Harper, "There is no evidence in the historical record that Joseph Smith told anyone but the minister of his vision for at least a decade", and Smith might have kept it private because of how uncomfortable that first dismissal was.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Harper|2019|pp=10–12}}</ref> During the 1830s, Smith orally described the vision to some of his followers, though it was not widely published among Mormons until the 1840s.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Harper|2019|pp=1, 51–55}}</ref> This vision later grew in importance to Smith's followers, who eventually regarded it as the first event in the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Allen |first=James B. |title=The Significance of Joseph Smith's "First Vision" in Mormon Thought |date=Autumn 1966 |url=https://scholarlypublishingcollective.org/uip/dial/article/1/3/28/247772/THE-SIGNIFICANCE-OF-JOSEPH-SMITH-S-FIRST-VISION-IN |journal=] |volume=1 |issue=3 |pages=29–46 |doi=10.2307/45223817 |jstor=45223817 |author-link=James B. Allen (historian) |s2cid=222223353|doi-access=free | issn = 0012-2157}}</ref> Smith himself may have originally considered the vision to be a personal conversion.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=39}}; {{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|p=30}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=39}}</ref> | |||

| Smith's leg became dangerously infected during the winter of ]-] when he was 8. Some doctors advised ], but Smith's family refused. Smith later recovered, though he used crutches for several years and was bothered with a limp for the rest of his life. | |||

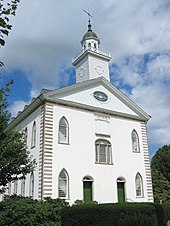

| ] at the ].]] | |||

| ] records show Smith was examined on ], ] regarding charges of "disorderly conduct" for money-digging activities. This action was probably brought by sons of Josiah Stowell, Smith's employer at the time. As his employer, Stowell had prevailed upon Smith to attempt to find buried treasure with magical powers. Smith informed Stowell that he had no magical powers. Still, Smith assisted Stowell in searching for Spanish treasure. Stowell terminated this fruitless "treasure digging” at Smith's advice. This created an enmity between some of Stowell's sons and Smith. Josiah felt that Smith was a harder worker than his sons were, presumably creating a degree of jealousy. At the examination (it was not a trial), seven witnesses were called and most of them affirmed that Smith had some sort of spiritual gift and the legal examination resulted in no action against Smith. Most scholars of the era acknowledge that "treasure digging" was a common form of ] (like water ]) and that Smith would have not been unique in its practice. | |||

| According to Smith's later accounts, while praying one night in 1823, he was visited by an angel named ]. Smith claimed this angel revealed the location of a buried book made of ], as well as other artifacts including a breastplate and a ] composed of two ] set in a frame, which had been hidden in ] near his home.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=136–38}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=43}}; {{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|pp=151–152}}</ref> Smith said he attempted to remove the plates the next morning, but was unsuccessful because Moroni returned and prevented him.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=50}}; {{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|p=38}}</ref> He reported that during the next four years he made annual visits to the hill, but, until the fourth and final visit, each time he returned without the plates.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=163–64}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=54}}</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, Smith's family faced financial hardship, due in part to the death of his oldest brother ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=42}}</ref> Family members supplemented their meager farm income by hiring out for odd jobs and working as treasure seekers,<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2008|p=21}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=33,48}}</ref> a type of ] common during the period.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Taylor |first=Alan |date=Spring 1986 |title=The Early Republic's Supernatural Economy: Treasure Seeking in the American Northeast, 1780–1830 |journal=American Quarterly |volume=38 |issue=1 |pages=6–34 |doi=10.2307/2712591|jstor=2712591 }}</ref> Smith was said to have an ability to locate lost items by looking into a seer stone, which he also used in treasure hunting, including, beginning in 1825, several unsuccessful attempts to find buried treasure sponsored by ], a wealthy farmer in ].<ref name="treasure">{{Harvtxt|Newell|Avery|1994|pp=17}}; {{Harvtxt|Brooke|1994|pp=152–53}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=43–44, 54–57}}; {{Harvtxt|Persuitte|2000|pp=33–53}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=45–53}}; {{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|p=29}}</ref> In 1826, Smith was brought before a Chenango County court for "glass-looking", or pretending to find lost treasure; Stowell's relatives accused Smith of tricking Stowell and faking an ability to perceive hidden treasure, though Stowell attested that he believed Smith had such abilities.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|pp=29–31}}</ref> The ] because primary sources report conflicting outcomes.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|p=33}}; {{cite journal |last=Vogel |first=Dan |title=Rethinking the 1826 Judicial Decision |url=http://mormonscripturestudies.com/ch/dv/1826.asp |journal=Mormon Scripture Studies: An e-Journal of Critical Thought |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110609204410/http://mormonscripturestudies.com/ch/dv/1826.asp |archive-date=June 9, 2011}}; {{cite web |title=Introduction to ''State of New York v. JS–A'' |url=https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/introduction-to-state-of-new-york-v-js-a/1 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221220004833/https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/introduction-to-state-of-new-york-v-js-a/1 |archive-date=December 20, 2022 |access-date=December 26, 2022 |website=] |postscript=,}}</ref> | |||

| Smith married ] in secret on ], ]. The couple ] due to the Hale family's disapproval of Smith. | |||

| ], who married Joseph Smith in 1827.|307x307px]] | |||

| ===The First Vision=== | |||

| While boarding at the Hale house, located in the township of Harmony (now ]) in ], Smith met and courted ]. When he proposed marriage, her father, Isaac Hale, objected; he believed Smith had no means to support his daughter.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=53}}; {{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|p=89}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|p=164}}</ref> Hale also considered Smith a stranger who appeared "careless" and "not very well educated".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Newell|Avery|1994|pp=17–18}}</ref> Smith and Emma ] and married on January 18, 1827, after which the couple began boarding with Smith's parents in Manchester. Later that year, when Smith promised to abandon treasure seeking, his father-in-law offered to let the couple live on his property in Harmony and help Smith get started in business.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=53–54}}</ref> | |||

| ''Main article: ]'' | |||

| Smith made his last visit to the hill shortly after midnight on September 22, 1827, taking Emma with him.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=12}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=163–64}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=54, 59}}; {{Harvtxt|Easton-Flake|Cope|2020|p=126}}</ref> This time, he said he successfully retrieved the plates.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=59–60}}; {{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=153}}</ref> Smith said Moroni commanded him not to show the plates to anyone else,{{efn|However, eventually a total of eleven others published statements affirming having been shown the plates. See ] and ].}} but to translate them and publish their translation. He also said the plates were a religious record of ] and were engraved in an unknown language, called ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=9}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=54}}; {{Harvtxt|Howe|2007|pp=313–314}}; {{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|p=41}}</ref> He told associates that he was capable of reading and translating them.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2004|pp=238–242}}; {{Harvtxt|Howe|2007|p=313}}</ref> | |||

| Smith ascribed great importance to a vision he claimed to have witnessed during his adolescence. Over the years, beginning in ], Smith described this experience many times using varying details. In his last major written account of the event (]), he described his vision as an appearance of ] and ] sometime during the spring of ], when he was fourteen years old. In his 1838 account he testifies: | |||

| Although Smith had abandoned treasure hunting, former associates believed he had double crossed them and had taken the golden plates for himself, property they believed should be jointly shared.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=61}}; {{Harvtxt|Howe|2007|p=315}}; {{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|pp=36–38}}</ref> After they ransacked places where they believed the plates might have been hidden, Smith decided to leave Palmyra.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=12}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=55}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=60–61}}</ref> | |||

| ===Founding a church (1827–1830)=== | |||

| "...''I saw a pillar of light exactly over my head, above the brightness of the sun, which descended gradually until it fell upon me...When the light rested upon me I saw two Personages, whose brightness and glory defy all description, standing above me in the air. One of them spake unto me, calling me by name, and said, pointing to the other, 'This is my Beloved Son. Hear Him''!'..." | |||

| {{Main|Life of Joseph Smith from 1827 to 1830}} | |||

| In October 1827, Smith and Emma permanently moved to Harmony, aided by a relatively prosperous neighbor, ],<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=55–56}}; {{Harvtxt|Newell|Avery|1994|p=2}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=62–63}}</ref> who began serving as Smith's scribe in April 1828.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Easton-Flake|Cope|2020|p=129}}</ref> Although he and his wife, Lucy, were early supporters of Smith, by June 1828 they began to have doubts about the existence of the golden plates. Harris persuaded Smith to let him take ] to Palmyra to show a few family members, including his wife.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|pp=15–16}}; {{Harvtxt|Easton-Flake|Cope|2020|pp=117–119}}; {{Harvtxt|Smith|1853|pp=117–18}}</ref> While Harris had the manuscript in his possession—of which there was no other copy—it was lost.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=16}};{{Harvtxt|Easton-Flake|Cope|2020|pp=117–118}}</ref> Smith was devastated by this loss, especially since it came at the same time as the death of his first son, who died shortly after birth.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=67–68}}</ref> Smith said that as punishment for his having lost the manuscript, Moroni returned, took away the plates, and revoked his ability to translate.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=17}}</ref> During this period, Smith briefly attended Methodist meetings with his wife, until a cousin of hers objected to inclusion of a "practicing ]" on the Methodist class roll.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=68–70}}</ref> | |||

| ], original 1830 edition]] | |||

| Smith said that Moroni returned the plates to him in September 1828,<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=18}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=70, 578n46}}; {{Harvtxt|Phelps|1833|loc=sec. 2:4–5}}; {{Harvtxt|Smith|1853|p=126}}</ref> and he then dictated some of the book to his wife Emma.<ref name="Bushman 2005 70">{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=70}}</ref> In April 1829 he met ], who had also dabbled in folk magic; and with Cowdery as scribe, Smith began a period of "rapid-fire translation".<ref name="Bushman 2005 70"/> Between April and early June 1829, the two worked full time on the manuscript, then moved to ], where they continued the work at the home of Cowdery's friend, ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=70–74}}</ref> When the narrative described an institutional church and a requirement for ], Smith and Cowdery baptized each other.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=5–6,15–20}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=74–75}}</ref> Dictation was completed about July 1, 1829.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=78}}</ref> According to Smith, Moroni took back the plates once Smith finished using them.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=68}}</ref> | |||

| The completed work, titled the ], was published in Palmyra by printer ]<ref>{{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|p=43}}</ref> and was first advertised for sale on March 26, 1830.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=154}}</ref> Less than two weeks later, on April 6, 1830, Smith and his followers formally organized the ], and small branches were established in Manchester, Fayette, and ].<ref>For the April 6 establishment of a church organization, see {{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=154}}; for Fayette and Manchester (and some ambiguity over a Palmyra presence), see {{Harvtxt|Hill|1989|pp=27, 201n84}}; for the Colesville congregation, see {{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|p=57}};</ref> The Book of Mormon brought Smith regional notoriety and renewed the hostility of those who remembered the 1826 Chenango County trial.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=117}}; {{Harvtxt|Vogel|2004|pp=484–486; 510–512}}</ref> After Cowdery baptized several new church members, Smith's followers were threatened with mob violence. Before Smith could ] the newly baptized, he was arrested and charged with being a "disorderly person".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Hill|1989|p=28}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=116–18}}</ref> Although he was ], both he and Cowdery fled to Colesville to escape a gathering mob. Smith later claimed that, probably around this time, ], ], and ] had appeared to him and had ordained him and Cowdery to a higher priesthood.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=24–26}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=118}}</ref> | |||

| Although Smith's family received the news of the vision well, it was met with deep contempt from most of his community, particularly clergymen. | |||

| Smith's authority was undermined when Cowdery, ], and other church members also claimed to receive revelations.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Hill|1989|p=27}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=120}}</ref> In response, Smith dictated a revelation which clarified his office as a prophet and an ], stating that only he had the ability to declare doctrine and scripture for the church.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Hill|1989|pp=27–28}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=121}}; {{Harvtxt|Phelps|1833|p=67}}</ref> Smith then dispatched Cowdery, Peter Whitmer, and others on a mission to ] ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Hill|1989|p=28}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=112}}; {{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|pp=59–60, 93, 95}}</ref> Cowdery was also assigned the task of locating the site of the ], which was to be "on the borders" of the United States with what was then Indian territory.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Phelps|1833|p=68}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=122}}</ref> | |||

| ===Moroni=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Smith claimed he was visited by an angel named ], three times during the evening and night of ], ], and once more in the morning of ]. According to Smith, Moroni told him about ] or tablets hidden in a hill near the Smith farm. These plates were said to contain an account of a group of ancient inhabitants of ], inscribed in ]. | |||

| On their way to ], Cowdery's party passed through northeastern ], where ] and over a hundred followers of his variety of ] ] converted to the Church of Christ, swelling the ranks of the new organization dramatically.<ref>Parley Pratt said that the Mormon mission baptized 127 within two or three weeks "and this number soon increased to one thousand". See {{Cite journal |last=McKiernan |first=F. Mark |date=Summer 1970 |title=The Conversion of Sidney Rigdon to Mormonism |journal=Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=71–78 |doi=10.2307/45224203 |jstor=45224203 |s2cid=254399092 |postscript=none|doi-access=free }}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=124}}; {{Harvtxt|Jortner|2022|pp=60–61}}</ref> After Rigdon visited New York, he soon became Smith's primary assistant.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McKiernan |first=F. Mark |date=Summer 1970 |title=The Conversion of Sidney Rigdon to Mormonism |journal=Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=71–78 |doi=10.2307/45224203 |jstor=45224203 |s2cid=254399092 |postscript=none|doi-access=free }} | |||

| On ], ], Smith went to Cumorah to recover the plates, but Moroni said he was unready. | |||

| ; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=124}}</ref> With growing opposition in New York, Smith announced a revelation that his followers should gather to ], establish themselves as a people and await word from Cowdery's mission.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=124–25}}; {{Harvtxt|Howe|2007|p=315}}</ref> | |||

| ===Life in Ohio (1831–1838)=== | |||

| Smith returned to the hill as directed by Moroni, on ], ], ], and ], and Moroni returned each night to counsel him. On ] ], with Emma in tow, Smith was allowed to take the plates, as well as the ], a breastplate to aid his translation. | |||

| {{Main|Life of Joseph Smith from 1831 to 1837}} | |||

| When Smith moved to Kirtland in January 1831, he encountered a religious culture that included enthusiastic demonstrations of ]s, including fits and trances, rolling on the ground, and ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=150–52}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=95}}</ref> Rigdon's followers were practicing a form of ]. Smith brought the Kirtland congregation under his authority and tamed ecstatic outbursts.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=154–55}}; {{Harvtxt|Hill|1977|p=131}}</ref> He had promised church ] that in Kirtland they would receive an ] of heavenly power, and at the June 1831 ], he introduced the greater authority of a ] to the church hierarchy.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=31–32}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=125, 156–60}}</ref> | |||

| ] Smith in 1832.]] | |||

| An official account of the First Vision and Smith's encounter with Moroni is contained in the ] in ], verses . | |||

| Converts poured into Kirtland. By the summer of 1835, there were fifteen hundred to two thousand Latter Day Saints in the vicinity,<ref name="Arrington 1979 21">{{Harvtxt|Arrington|Bitton|1979|p=21}}</ref> many expecting Smith to lead them shortly to the ] kingdom.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=81}}</ref> Though his mission to the Native Americans had been a failure,<ref>{{Harvtxt|Turner|2012|p=41}}</ref><ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=161}}</ref> Cowdery and the other missionaries with him were charged with finding a site for "a holy city". They found ]. After Smith visited in July 1831, he pronounced the frontier hamlet of ] the "center place" of ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=162–163}}; {{Harvtxt|Smith|Cowdery|Rigdon|Williams|1835|p=154}}</ref> | |||

| For most of the 1830s, the church was effectively based in Ohio.<ref name="Arrington 1979 21"/> Smith lived there, though he visited Missouri again in early 1832 to prevent a rebellion of prominent church members who believed the church in Missouri was being neglected.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=180–182}}</ref> Smith's trip was expedited by a mob of Ohio residents who were outraged over the church's presence and Smith's political power. The mob beat Smith and Rigdon unconscious, ] them, and left them for dead.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=109–10}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=178–80}}</ref> | |||

| ===Translation of the Book of Mormon=== | |||

| Smith translated portions of the plates from December ] to February ]; Emma and her brother Reuben acted as scribes. The faithful believe that Smith translated the plates using divine guidance and the ]. According to his scribes, Smith rarely, if ever, stopped and corrected himself. He would translate a sentence, the scribe would say "Written" and read it back to him. If the sentence was written correctly, Smith would continue. They would work through the day, often into the night. | |||

| In Jackson County, existing Missouri residents resented the Latter Day Saint newcomers for both political and religious reasons.<ref>See {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=113–15}}; {{Harvtxt|Arrington|Bitton|1979|p=61}})</ref> Additionally, their rapid growth aroused fears that they would soon constitute a majority in local elections, and thus "rule the county".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=222}}</ref> Tension increased until July 1833, when non-Mormons forcibly evicted the Mormons and destroyed their property. Smith advised his followers to bear the violence patiently until after they had been attacked multiple times, after which they could fight back.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=181–83,235}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=82–83}}</ref> Armed bands exchanged fire, killing one Mormon and two non-Mormons, until the old settlers forcibly expelled the Latter Day Saints from the county.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=83–84}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=222–27}}</ref> | |||

| ] acted as Smith's translation scribe from April to June of ]. In early April, ], Smith began translating again, with ] as scribe. Others also helped. When translation was complete, Smith said he returned the plates to ]. | |||

| After petitions to Missouri governor ] for aid were unsuccessful,<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=227–8}}; Bruce A. Van Orden, "" in ''We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps'' (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 123–134.</ref> Smith organized and led a small ] expedition, called ], to aid the Latter Day Saints in Missouri.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=115}}</ref> As a military endeavor, the expedition was a failure. The men of the expedition were disorganized, suffered from a ] outbreak and were severely outnumbered. By the end of June, Smith deescalated the confrontation, sought peace with Jackson County's residents, and disbanded Zion's Camp.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Hill|1989|pp=44–46}} (for Smith deescalating and disbanding the camp); {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=235–46}} (for the numerical limitations, social tension, and cholera outbreak in the camp).</ref> Nevertheless, Zion's Camp transformed Latter Day Saint leadership because many future church leaders came from among the participants.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=246–247}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=85}}</ref> | |||

| The scribes never physically saw the plates while Smith was translating. Instead, Smith hung a curtain between himself and the scribe, as commanded by Moroni. Later, ] and then ] were allowed to view the plates. The plates were presented to the three witnesses by an angel. The eight witnesses were shown the plates by Joseph Smith. ], who boarded Smith and Emma during the translation’s final phase, said Moroni showed her the plates. Emma and others reported touching and moving the plates as they lay under a heavy cloth or in a bag. | |||

| After the Camp returned to Ohio, Smith drew heavily from its participants to establish various governing bodies in the church.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=247}}; see also {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=100–104}} for a timeline of Smith introducing the new organizational entities.</ref> He gave a revelation announcing that in order to redeem Zion, his followers would have to receive an endowment in the ],<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=156–57}}; {{Harvtxt|Smith|Cowdery|Rigdon|Williams|1835|p=233}}<!-- D&C 105: https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/doctrine-and-covenants-1835/241; see also https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revelation-22-june-1834-dc-105/1-->; {{Harvtxt|Prince|1995|p=32 & n.104}}<!--D&C 105:10-12-->.</ref> which he and his followers constructed. In March 1836, at the temple's dedication, many who received the endowment reported seeing visions of angels and engaged in prophesying and speaking in tongues.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=310–19}}</ref> | |||

| The ] was first published on ], ]. | |||

| ] in 1836.]] | |||

| ===Church Founded=== | |||

| In January 1837, Smith and other churchleaders created a ], called the ], to act as a quasi-bank; the company issued ]s partly ] by real estate. Smith encouraged his followers to buy the notes, in which he invested heavily himself. The bank failed within a month.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=122–123}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=328–334}}</ref> As a result, Latter Day Saints in Kirtland suffered extreme high ] and intense pressure from debt collectors. Smith was held responsible for the failure, and there were widespread defections from the church, including many of Smith's closest advisers.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=124}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=331–32, 336–39}}</ref> | |||

| According to Cowdery and Smith, on ], ], ] appeared and ordained them to the ]. They baptized each other immediately thereafter, exercising their new authority. ], ], and ] also came to them during either May or June 1829 and ordained them to the ]. Latter Day Saints believe that the authority found in these priesthoods was necessary for a complete restoration of the Ancient Church. | |||

| The failure of the bank was one part of a series of internal disputes led to the demise of the Kirtland community.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brooke|1994|p=221}}</ref> Cowdery had accused Smith of engaging in a sexual relationship with a teenage servant in his home, ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=322}}; {{Harvtxt|Compton1997|pp=25–42}}</ref> Construction of the Kirtland Temple had only added to the church's debt, and Smith was hounded by creditors.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=217, 329}}</ref> After a warrant was issued for Smith's arrest on a charge of ], he and Rigdon fled for Missouri in January 1838.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=125}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=339–40}}; {{Harvtxt|Hill|1977|p=216}}</ref> | |||

| On ], ], Smith and five others formally established "The Church of Christ". (The church was later called “Church of Latter Day Saints” (1834), “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints” (1838) then “]”.) Smith and others quickly began ] and baptizing new members. | |||

| ===Life in Missouri (1838–39)=== | |||

| Smith asserted that he received many revelations throughout this period. These were compiled as ''The Book of Commandments'' at that time and were organized into the ] in ]. | |||

| {{Main|Life of Joseph Smith from 1838 to 1839}} | |||

| By 1838, Smith had abandoned plans to redeem Zion in Jackson County, and instead declared the town of ], in ], as the new "Zion".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Hill|1977|pp=181–82}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=345, 384}}</ref> In Missouri, the church also took the name "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints", and construction began on a new temple.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=210, 222–23}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=628}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=131}}</ref> In the weeks and months after Smith and Rigdon arrived at Far West, thousands of Latter Day Saints followed them from Kirtland.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=125}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=341–46}}</ref> Smith encouraged the settlement of land outside Caldwell County, instituting a settlement in ], in ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Walker |first=Jeffrey N. |date=2008 |title=Mormon Land Rights in Caldwell and Daviess Counties and the Mormon Conflict of 1838: New Findings and New Understandings |journal=BYU Studies |volume=47 |issue=1 |pages=4–55 |jstor=43044611 |postscript=none }}; {{Cite journal |last=LeSueur |first=Stephen C. |date=Fall 2005 |title=Missouri's Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons |journal=Journal of Mormon History |volume=31 |issue=2 |pages=113–144 |jstor=23289934 |postscript=none }}</ref> | |||

| Political and religious differences between old Missourians and newly arriving Latter Day Saint settlers provoked tensions between the two groups, much as they had in Jackson County. By this time, Smith's experiences with mob violence led him to believe that his faith's survival required greater militancy against ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=92}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=213}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=355}}</ref> Tensions between the Mormons and the native Missourians escalated quickly until, on August 6, 1838, non-Mormons in ], tried to prevent Mormons from voting, and a brawl ensued.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=357}}</ref> The election day scuffles initiated the ]. Non-Mormon ] raided and burned Mormon farms, while ] and other Mormons pillaged non-Mormon towns.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=134}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=96–99, 101}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=363}}</ref> In the ], a group of Mormons attacked the Missouri state militia, mistakenly believing them to be anti-Mormon vigilantes. Governor ] then ] that the Mormons be "exterminated or driven from the state".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=364–65}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=100}}</ref> On October 30, a party of Missourians surprised and killed seventeen Mormons in the ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=365–66}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=97}}</ref> | |||

| ==Ohio== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| To avoid conflict and persecution encountered in ] and ], Smith and Emma eventually moved to ] early in ]. They lived with ]’s family while a house was built for them on the Morley farm. Many of Smith's followers and associates settled in ], and also in ], where Smith said he was instructed by revelation to build ]. | |||

| The following day, the Mormons surrendered to 2,500 state troops and agreed to forfeit their property and leave the state.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=366–67}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=239}}</ref> Smith was immediately ], accused of ], and sentenced to be executed the next morning, but ], who was Smith's former attorney and a brigadier general in the Missouri militia, refused to carry out the order.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=242, 344, 367}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=241}}</ref> Smith was then sent to a state court for a ], where several of his former allies testified against him.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=369}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=225–26, 243–45}}</ref> Smith and five others, including Rigdon, were charged with treason, and transferred to the ] at ], to await trial.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=369–70}}</ref> | |||

| Smith bore his imprisonment stoically. Understanding that he was effectively on trial before his own people, many of whom considered him a fallen prophet, he wrote a personal defense and an apology for the activities of his followers. "The ]", he wrote, "have not been taken away from us".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|pp=136–37}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=245–46}};{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=101–102}}</ref> Though he directed his followers to collect and publish their stories of persecution, he also urged them to moderate their antagonism toward non-Mormons.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=377–378}}</ref> On April 6, 1839, after a ] hearing in Daviess County, Smith and his companions escaped custody, almost certainly with the connivance of the sheriff and guards.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=375}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=253–255}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=382, 635–36}}; {{cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Mormonism |title=Smith, Joseph: Legal Trials of Joseph Smith |year=1992 |last=Bentley |first=Joseph I. |publisher=] |location=New York |url=http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EoM/id/4208 |access-date=May 5, 2023 |isbn=0-02-879602-0 |pages=1346–1348 |editor-last=Ludlow |editor-first=Daniel H. |editor-link=Daniel H. Ludlow |title-link=Encyclopedia of Mormonism |oclc=24502140}}</ref> | |||

| In Kirtland, the church's first temple was built, and many extraordinary events were reported: appearances by ], ], ], ], and numerous ]s; speaking and singing in ], often with translations; ]ing; and other ]s. Some Mormons believed that Jesus' Millennial reign had come. Even those of other faiths reported a heavenly light "resting" upon the temple. | |||

| ===Life in Nauvoo, Illinois (1839–1844)=== | |||

| The early Church grew rapidly, but there were often conflict between Saints and their neighbors. These conflicts were sometimes violent: On the evening of ], ] in ], a group of men beat and ] Smith and his counselor ]. They threatened Smith with ] and with death, and one of his teeth was chipped when they attempted to force him to drink ]. The mob action led to the exposure and eventual death of Smith's adopted newborn twins. Sidney Rigdon suffered a severe concussion after being dragged on the ground. According to some accounts, Rigdon was delirious for several days. The reasons for this attack are uncertain, but likely were tied to a sermon given by Rigdon. | |||

| {{main|Life of Joseph Smith from 1839 to 1844}} | |||

| Many American newspapers criticized Missouri for the Haun's Mill massacre and the state's expulsion of the Mormons.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=246–247, 259}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=398}}</ref> Illinois then accepted Mormon refugees who gathered along the banks of the ],<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=381}}</ref> where Smith purchased high-priced, swampy woodland in the hamlet of ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=383–384}}</ref> He attempted to portray the Mormons as an oppressed minority and unsuccessfully petitioned the ] for help in obtaining ]s.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=392–94,398–99}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=259–60}}</ref> During the summer of 1839, while Mormons in Illinois suffered from a ] epidemic, Smith sent Young and other apostles to missions in Europe, where they made numerous converts, many of them poor factory workers.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=386, 409}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=258, 264–65}}</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| After tending to his wounds all night and into the early morning, Smith preached a sermon on forgiveness the following day. Though some reports state that members of the mob that had attacked him were present at this sermon, Smith did not mention the attack directly. | |||

| Smith also attracted a few wealthy and influential converts, including ], the Illinois ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=410–11}}</ref> Bennett used his connections in the ] to obtain an unusually liberal charter for the new city, which Smith renamed "]".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=267–68}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=412,415}}</ref> The charter granted the city virtual autonomy, authorized a university, and granted Nauvoo '']'' power—which allowed Smith to fend off ] to Missouri. Though Latter Day Saint authorities controlled Nauvoo's civil government, the city guaranteed ] for its residents.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1998|pp=106–08}}</ref> The charter also authorized the ], a militia whose actions were limited only by state and federal constitutions. Smith and Bennett became its commanders, and were styled ] and ] respectively. As such, they controlled by far the largest body of armed men in Illinois.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=271}}</ref> Smith appointed Bennett as Assistant President of the Church, and Bennett was elected Nauvoo's first mayor.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=410–411}}</ref> | |||

| ], which was completed after his death.]] | |||

| On ], ] Smith and Rigdon left Kirtland for ] in ], in Smith's words, "to escape mob violence, which was about to burst upon us under the color of legal process to cover the hellish designs of our enemies." Just prior to their departure, many Saints, (including prominent leaders), became disaffected in the wake of the ] debacle, in which Smith and several associates were accused of various illegal or unethical ] actions. | |||

| The early Nauvoo years were a period of doctrinal innovation. Smith introduced ] in 1840, and in 1841 construction began on the ] as a place for recovering lost ancient knowledge.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=448–49}}; {{Harvtxt|Park|2020|pp=57–61}}</ref> An 1841 revelation promised the restoration of the "fullness of the priesthood"; and in May 1842, Smith inaugurated a revised endowment or "first anointing".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=113}}</ref> The endowment resembled the rites of ] that Smith had observed two months earlier when he had been initiated "]" into the Nauvoo Masonic lodge.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=449}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=114–15}}</ref> At first, the endowment was open only to men, who were initiated into a special group called the ]. For women, Smith introduced the ], a ] and ] within which Smith predicted women would receive "the keys of the kingdom".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=634}}</ref> Smith also elaborated on his plan for a Millennial kingdom; no longer envisioning the building of Zion in Nauvoo, he viewed Zion as encompassing all of North and South America, with Mormon settlements being "]" of Zion's metaphorical tent.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=384,404}}</ref> Zion also became less a refuge from an impending ] than a great building project.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=415}}</ref> In the summer of 1842, Smith revealed a plan to establish the millennial Kingdom of God, which would eventually establish ] rule over the whole Earth.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=111–12}}</ref> | |||

| It was around this time that Smith began secretly marrying additional wives, a practice called ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=427–28}}</ref> He introduced the doctrine to a few of his closest associates, including Bennett, who used it as an excuse to seduce numerous women, wed and unwed.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=460}}{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=311–12}}</ref> When rumors of polygamy (called "spiritual wifery" by Bennett) got abroad, Smith forced Bennett's resignation as Nauvoo mayor. In retaliation, Bennett left Nauvoo and began publishing sensational accusations against Smith and his followers.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Ostling|Ostling|1999|p=12}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=461–62}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=314}}</ref> | |||

| Most remaining church members left Kirtland for ]. | |||

| By mid-1842, popular opinion in Illinois had turned against the Mormons. After an unknown assailant shot and wounded Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs in May 1842, anti-Mormons circulated rumors that Smith's bodyguard, ], was the gunman.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=468}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=323}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=113}}</ref> Though the evidence was circumstantial, Boggs ordered Smith's extradition. Certain he would be killed if he ever returned to Missouri, Smith went into hiding twice during the next five months, until the ] for Illinois argued that his extradition would be unconstitutional.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=468–75}}</ref> (Rockwell was later tried and acquitted.) In June 1843, enemies of Smith convinced a reluctant ] ] to extradite Smith to Missouri on an old charge of treason. Two law officers arrested Smith but were intercepted by a party of Mormons before they could reach Missouri. Smith was then released on a writ of ''habeas corpus'' from the Nauvoo municipal court.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=504–08}}</ref> While this ended the Missourians' attempts at extradition, it caused significant political fallout in Illinois.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=508}}</ref> | |||

| ===Plural marriage=== | |||

| Most believe that Smith began practicing a form of ] called celestial marriage (later called ]) perhaps as early as 1833 . ] (marriage to multiple partners) was illegal in many U.S. States, including Illinois, and was felt by some to be an immoral or misguided practice. | |||

| There is disagreement as to the precise number of wives Smith may have had: one historian, Todd M. Compton, who contends that polygamy was a mistake for the Church, tried to document, using Utah LDS sources, at least thirty-three plural marriages or sealings during Smith's lifetime. See ] for a list of these wives. It is without question that Joseph had multiple wives (as marriage certificates are available for some); but, as Compton states multiple times in his work "bsolutely nothing is known of this marriage after the ceremony"; that is, it is unclear how many (if any) of these marriages Smith consummated. Information on the intention of some of the ] is similarly ambiguous; Smith has been sealed to many people as a father or a brother as well as those instances of being a husband. If these marriage sealings were indeed sexual unions it would be reasonable to expect some children from them as there were from Smith's first marriage. One of the plural wives made an allegation that Smith had fathered one of her children, but this is disputed, as is the theory that Smith fathered children with some of his plural wives that were raised as though they were the children of their other husbands. Dr. Scott Woodward and others are conducting DNA evidence of possible descendants of Joseph Smith. To date, none of these plural marriages has been shown to have produced genetic offspring of Joseph Smith . | |||

| ] by ] sometime in 1844; the photograph was published in 2022 in the '']''.<ref name="daguerreotype">{{cite journal |last1=Romig |first1=Ronald |last2=Mackay |first2=Lachlan |date=Spring–Summer 2022 |title=Hidden Things Shall Come to Light: The Visual Image of Joseph Smith Jr. |journal=John Whitmer Historical Association Journal |volume=42 |issue=1 |pages=28–60 |issn=0739-7852}}</ref><ref>There is disagreement among historians about the identification and provenance of this daguerrotype; for an overview of arguments and positions for and against, see {{cite news |last=Stack |first=Peggy Fletcher |date=July 29, 2022 |title='The Whole Affect Feels Off to Me' — Why Some Historians Doubt That's a Photo of Joseph Smith |work=] |url=https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2022/07/29/is-it-him-or-isnt-it-historians/}}</ref>]] | |||

| The ] believes that polygamy was instituted according to revelation, as it was in the times of many Old Testament prophets. The LDS Church publicly announced the practice in ] in ], after which the doctrine was generally accepted, but not widely practiced. Plural marriage was later formally discontinued by the LDS Church, which currently excommunicates members who practice it. The ] (formerly Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) denied for many years that Smith ever taught or practiced polygamy. More recently, Community of Christ historians have publicly supported the view that Smith taught the doctrine. {{ref|compton}} Many splinter groups of the Latter Day Saint Movement descended from the LDS Church continue to practice plural marriage. | |||

| In December 1843, Smith petitioned ] to make Nauvoo an independent territory with the right to call out federal troops in its defense.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=356}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=115–116}}</ref> Smith then wrote to the leading presidential candidates, asking what they would do to protect the Mormons. After receiving noncommittal or negative responses, he announced ] for ], suspended regular proselytizing, and sent out the Quorum of the Twelve and hundreds of other political missionaries.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=118–119}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=514–515}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=362–364}}</ref> In March 1844—following a dispute with a federal bureaucrat—he organized the secret ], which was given the authority to decide which national or state laws Mormons should obey, as well as establish its own government for Mormons.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=519}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=120–22}}</ref> Before his death the Council also voted unanimously to elect Smith "Prophet, Priest, and King".<ref>{{cite magazine |date=March 20, 2020 |title=How Joseph Smith and the Early Mormons Challenged American Democracy |url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/03/30/how-joseph-smith-and-the-early-mormons-challenged-american-democracy |access-date=April 18, 2023 |magazine=The New Yorker |language=en-US}}</ref> The Council was likewise appointed to select a site for a large Mormon settlement in the ], ], or ] (then controlled by ]), where Mormons could live under theocratic law beyond the control of other governments.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=517}}</ref> | |||

| Although Smith publicly denied plural marriage during the early days of the church, he practiced it secretly, and introduced a small number of followers into the practice. In the early Latter Day Saint era, some followers who practiced plural marriage said they were uncomfortable with it when it was first introduced to them, but believed it was commissioned by God. | |||

| ===Death=== | |||

| By most accounts, Emma Smith was at times supportive, but often troubled by ]; nevertheless, she eventually accepted the doctrine along with the others Joseph had revealed. | |||

| {{Main|Killing of Joseph Smith}} | |||

| ] | |||

| By early 1844, a rift developed between Smith and a half dozen of his closest associates.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=527–28}}</ref> Most notably, ], his trusted counselor, and Robert Foster, a ] of the Nauvoo Legion, disagreed with Smith about how to manage Nauvoo's economy.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=368–9}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=528}}</ref> Both also said that Smith had proposed marriage to their wives.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Ostling|Ostling|1999|p=14}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=369–371}}; {{Harvtxt|Van Wagoner|1992|p=39}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=660–61}}</ref> Believing these men were plotting against his life, Smith excommunicated them on April 18, 1844.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=549, 531}}</ref> Law and Foster subsequently formed a ], and in the following month, at the ] in ], they procured indictments against Smith for ] (as Smith publicly denied having more than one wife) and polygamy.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=373}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=531, 538}}; {{Harvtxt|Park|2020|p=227}}</ref> | |||

| On June 7, the dissidents published the first (and only) issue of the '']'', calling for reform within the church but also appealing politically to non-Mormons.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=539}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=374}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=138}}</ref> The paper alluded to Smith's theocratic aspirations, called for a repeal of the Nauvoo city charter, and decried his new "doctrines of many Gods". (Smith had recently given his ], in which he said that God was once a man, and that men and women could become gods.)<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=539}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=375}}; {{Harvtxt|Marquardt|1999|p=312}}; {{Harvtxt|Ulrich|2017|pp=113–114}}</ref> It also attacked Smith's practice of polygamy, implying that he was using religion as a pretext to draw unassuming women to Nauvoo to seduce and marry them.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Oaks|Hill|1975|p=14}}; {{Harvtxt|Davenport|2022|pp=147–148}}. The text of the ].</ref> | |||

| ==Missouri== | |||

| The Missouri period was marked by many violent conflicts and legal difficulties for Smith and his followers. Many people saw their new LDS neighbors as a religious and political threat. Mormons also tended to vote in blocks, giving them a degree of political influence wherever they settled. Additionally, Mormons purchased vast amounts of land in which to establish settlements. Some Saints felt that God had promised them control of the area and this view only fueled the growing tension. | |||

| Fearing the ''Expositor'' would provoke a new round of violence against the Mormons, the Nauvoo City Council declared the newspaper a public nuisance, and Smith ordered the Nauvoo Legion to assist the police force in destroying its ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Park|2020|pp=228–230}}; {{Harvtxt|Marquardt|1999|p=312}}</ref> During the council debate, Smith vigorously urged the council to order the press destroyed,<ref>{{Harvtxt|Park|2020|pp=229–230}}</ref> not realizing that destroying a newspaper was more likely to incite an attack than any of the newspaper's accusations.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=541}}</ref> | |||

| In response to the consistent persecution, a small group of Latter Day Saints organized themselves into a ] group called the ]. Headed by Sampson Avard, Smith disapproved of the group, and Avard was excommunicated for his activities. | |||

| ] | |||

| Soon the "old Missourians" and the LDS settlers were engaged in a conflict sometimes referred to as the ] ]. One key skirmish was the ], which involved Missouri state troops and a group of Saints. There is some debate as to whether the Mormons knew their opponents were government officials, but the battle's aftermath was pivotal in Church history. | |||

| Destruction of the newspaper provoked a strident call to arms from ], editor of the '']'' and longtime critic of Smith.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Ulrich|2017|p=114}}; {{Harvtxt|Park|2020|p=230}}</ref> Fearing mob violence, Smith mobilized the Nauvoo Legion on June 18 and declared ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Park|2020|pp=231–232}}; {{Harvtxt|McBride|2021|pp=186–187}}</ref> Officials in Carthage responded by mobilizing a small detachment of the state militia, and Governor Ford intervened, threatening to raise a larger militia unless Smith and the Nauvoo City Council surrendered themselves.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Ostling|Ostling|1999|p=16}}</ref> Smith initially fled across the Mississippi River, but shortly returned and surrendered to Ford.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=546}}; {{Harvtxt|Park|2020|p=233}}</ref> On June 25, Smith and his brother ] arrived in Carthage to stand trial for inciting a riot.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Ostling|Ostling|1999|p=17}}; {{Harvtxt|Park|2020|p=234}}; {{Harvtxt|McBride|2021|p=191}}</ref> Once the Smiths were in custody, the charges were increased to treason, preventing them from posting ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Mormonism |title=Smith, Joseph: Legal Trials of Joseph Smith |year=1992 |last=Bentley |first=Joseph I. |publisher=] |location=New York |url=http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/EoM/id/4208 |access-date=May 5, 2023 |isbn=0-02-879602-0 |pages=1346–1348 |editor-last=Ludlow |editor-first=Daniel H. |editor-link=Daniel H. Ludlow |title-link=Encyclopedia of Mormonism |oclc=24502140}}; {{Harvtxt|Oaks|Hill|1975|p=18}}; {{Harvtxt|Park|2020|p=234}}</ref> ] and ] voluntarily accompanied the Smiths in ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|McBride|2021|p=192}}</ref> | |||

| ]s of Joseph Smith (left) and ] (right)]] | |||

| This battle led to reports of a "Mormon insurrection" and the death of apostle ]. In consequence of these reports and the political influence of pro-slavery politicians, Missouri Governor ] issued an executive order known as the "]" on ] ]. The order stated that the Mormon community was in "open and avowed defiance of the laws, and of having made war upon the people of this State ... the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace—their outrages are beyond all description." The Extermination Order wasn't until ] by Governor ]. | |||

| On June 27, 1844, an armed mob with blackened faces stormed ], where Joseph and Hyrum were being detained. Hyrum, who was trying to secure the door, was killed instantly with a shot to the face. Smith fired three shots from a ] pistol that his friend, ], had lent him, wounding three men,<ref>{{Harvtxt|Oaks|Hill|1975|p=52}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=393}}</ref> before he sprang for the window.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=549}}</ref> (Smith and his companions were staying in the jailer's bedroom, which did not have bars on the windows.) He was shot multiple times before falling out of the window, crying, "Oh Lord my God!" He died shortly after hitting the ground, but was shot several more times by an improvised ] before the mob dispersed.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=393–94}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=549–50}}</ref> | |||

| Soon after the "Extermination Order" was issued, vigilantes attacked an outlying Mormon settlement and killed 17. This event is identified as the ]. Soon afterward, the 2,500 troops from the state militia converged on the Mormon headquarters at ]. Smith and several other Church leaders surrendered to state authorities on ] charges. Although they were civilians, the militia leader threatened to try Smith and others in a military tribunal and have them immediately executed. Were it not for the actions of General ] in defense of ], the plans of the militia leaders likely would have been carried out. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| The legality of Boggs' “Extermination Order” was debated in the legislature, but its objectives were achieved. Most of the Mormon community in Missouri either left or were forced out by the spring of ]. | |||

| {{Main|Legacy of Joseph Smith}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Immediate aftermath=== | |||

| Instead of execution, Smith and others spent several months in ] awaiting a trial that never came. With shaky legal grounds for imprisonment, authorities eventually allowed their escape. They joined the rest of the Church in Illinois. | |||

| Following Smith's death, non-Mormon newspapers were nearly unanimous in portraying Smith as a religious fanatic.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=332, 557–59}}</ref> Conversely, within the Latter Day Saint community, Smith was viewed as a prophet, ] to seal the testimony of his faith.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=558}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|pp=396–97}}</ref> | |||

| After a public funeral and viewing of the deceased brothers, Smith's widow—who feared hostile non-Mormons might try to ] the bodies—had their remains buried at night in a secret location, with substitute coffins filled with ]s interred in the publicly attested grave.<ref name=":8">{{cite journal |last=Wiles |first=Lee |date=Summer 2013 |title=Monogamy Underground: The Burial of Mormon Plural Marriage in the Graves of Joseph and Emma Smith |journal=Journal of Mormon History |volume=39 |issue=3 |pages=vi–59 |doi=10.2307/24243852 |jstor=24243852 |s2cid=254486845 |postscript=none}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Bernauer |first=Barbara Hands |date=1991 |title=Still 'Side by Side'—The Final Burial of Joseph and Hyrum Smith |journal=John Whitmer Historical Association Journal |volume=11 |pages=17–33 |jstor=43200879 |postscript=none}}</ref> The bodies were later moved and reburied under an outbuilding on the Smith property off the Mississippi River.<ref name=":9">{{cite journal |last=Mackay |first=Lachlan |date=Fall 2002 |title=A Brief History of the Smith Family Nauvoo Cemetery |url=https://ensignpeakfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/MHS3.2Fall2002SmithFamilyNauvooCemetery.pdf |journal=Mormon Historical Studies |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=240–252}}</ref> Members of the ] (RLDS Church), under the direction of then-RLDS Church president ] (Smith's grandson) searched for, located, and disinterred the Smith brothers' remains in 1928 and reinterred them, along with Smith's wife, in Nauvoo at the ].<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /> | |||

| ==Nauvoo== | |||

| ] | |||

| After leaving Missouri in 1839, Smith and his followers made headquarters in a town called ] on the banks of the ], which they renamed ] (meaning "to be beautiful"; - the word is found in the Hebrew of Isaiah 52:7 - Latter Day Saints often referred to Nauvoo as "the city beautiful", or "the city of Joseph"—which was actually the name of the city for a short time after the city charter was revoked—or other similar nicknames) after being granted a charter by the state of ]. Nauvoo was quickly built up by the faithful, including many new arrivals. | |||

| ===Impact and assessment=== | |||

| In October 1839, Smith and others left for ] to meet with ], then the ]. Smith and his delegation sought redress for the persecution and loss of property suffered by the Saints in Missouri. Van Buren told Smith, "Your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you." | |||

| Modern biographers and scholars—Mormon and non-Mormon alike—agree that Smith was one of the most influential, charismatic, and innovative figures in American religious history.<ref name="innovative">{{Harvtxt|Bloom|1992|pp=96–99}}; {{Harvtxt|Persuitte|2000|p=1}}; {{Harvtxt|Remini|2002|p=ix}}</ref> In a 2015 compilation of the 100 Most Significant Americans of All Time, ] ranked Smith first in the category of religious figures.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Lloyd |first=R. Scott |date=January 9, 2015 |title=Joseph Smith, Brigham Young Rank First and Third in Magazine's List of Significant Religious Figures |work=Church News |url=https://www.thechurchnews.com/2015/1/9/23212603/joseph-smith-brigham-young-rank-first-and-third-in-magazines-list-of-significant-religious-figures}}</ref> In popular opinion, non-Mormons in the U.S. generally consider Smith a "charlatan, scoundrel, and heretic", while outside the U.S. he is "obscure".<ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Turner |first=John G. |date=May 6, 2022 |title=Why Joseph Smith Matters |url=https://themarginaliareview.com/why-does-joseph-smith-matter/ |url-status=live |magazine=Marginalia Review |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220817102528/https://themarginaliareview.com/why-does-joseph-smith-matter/ |archive-date=August 17, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| Within the Latter Day Saint movement, Smith's legacy varies between denominations:<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal |last=Launius |first=Roger D. |date=Winter 2006 |title=Is Joseph Smith Relevant to the Community of Christ? |journal=Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought |volume=39 |issue=4 |pages=58–67 |doi=10.2307/45227214 |jstor=45227214 |s2cid=254402921 |postscript=none |doi-access=free }}</ref> ] (LDS Church) and its members consider Smith the founding prophet of their church,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Oaks |first=Dallin H. |date=2005 |title=Joseph Smith in a Personal World |department=The Worlds of Joseph Smith: A Bicentennial Conference at the Library of Congress |journal=Brigham Young University Studies |volume=44 |issue=4 |pages=153–172 |jstor=43045057 |postscript=none }}</ref> on par with ] and ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=vii}}; {{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|p=37}}; {{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|p=xx}}; {{Harvtxt|Widmer|2000|p=97}}</ref> Meanwhile, Smith's reputation is ambivalent in the ], which continues "honoring his role" in the church's founding history but deemphasizes his human leadership.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Moore |first=Richard G. |date=Spring 2014 |title=LDS Misconceptions about the Community of Christ |url=https://ensignpeakfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/LDS-Misconceptions.pdf |url-status=live |journal=Mormon Historical Studies |volume=15 |issue=1 |pages=1–23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211120065445/https://ensignpeakfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/LDS-Misconceptions.pdf |archive-date=November 20, 2021}}</ref> Conversely, Woolleyite ] has deified Smith within a cosmology of many gods.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rosetti |first=Cristina |date=Fall 2021 |title=Praise to the Man: The Development of Joseph Smith Deification in Woolleyite Mormonism, 1929–1977 |url=https://scholarlypublishingcollective.org/uip/dial/article/54/3/41/291779/Praise-to-the-Man-The-Development-of-Joseph-Smith |journal=Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought |volume=54 |issue=3 |pages=41–65 |doi=10.5406/dialjmormthou.54.3.0041 |s2cid=246647004 |postscript=none |doi-access=free}}</ref> {{multiple image | |||

| In March ], Smith was initiated as a ] (as an Entered Apprentice Mason on ], and ] the next day—the usual month wait between degrees was waived by the Illinois Lodge Grandmaster, Abraham Jonas) at the Nauvoo Lodge, one of less than a half-dozen Masonic meetings he attended. He was introduced by ], a Mason from the northeast. | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | header = Buildings named in honor of Smith | |||

| | header_align = center | |||

| | image1 = JSMB main.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 164 | |||

| | caption1 = The ] in ] | |||

| | image2 = BYU_JSB.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 145 | |||

| | caption2 = The ] on the campus of ] | |||

| }} | |||

| Memorials to Smith include the ] in ]<ref>{{cite web |last1=Rockwell |first1=Ken |last2=Neatrour |first2=Anna |last3=Muir-Jones |first3=James |date=2018 |title=Repurposing Secular Buildings |url=https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/religious-diversity-in-salt-lake-city/page/repurposing-secular-buildings |website=Religious Diversity in Salt Lake City |publisher=University of Utah}}</ref> the former Joseph Smith Memorial building on the campus of ] as well as the ] there,<ref>{{cite web |last=Cook |first=Emily |date=June 18, 2018 |title=Joseph Smith Memorial Building (JSB) |url=https://www.intermountainhistories.org/items/show/228 |access-date=December 22, 2022 |website=Intermountain Histories |language=en}}</ref> a ] marking Smith's birthplace,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Erekson |first=Keith A. |date=Summer–Fall 2005 |title=The Joseph Smith Memorial Monument and Royalton's 'Mormon Affair': Religion, Community, Memory, and Politics in Progressive Vermont |url=https://vermonthistory.org/journal/73/04_Erekson.pdf |journal=Vermont History |volume=73 |pages=118–151}}</ref> and a fifteen-foot-tall bronze statue of Smith in the World Peace Dome in ], India.<ref name=":6">{{Cite news |last=Stack |first=Peggy Fletcher |date=November 26, 2022 |title=What's a Giant Statue of Mormonism's Joseph Smith Doing in India? |work=Salt Lake Tribune |url=https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2022/11/26/whats-giant-statue-mormonisms/}}</ref> | |||

| <!--This part about the temple needs a lot of expansion, probably on another page--> | |||

| Work on a ] in ] began in the autumn of ]. The cornerstones were laid during a conference on ], ]. Construction took five years and it was dedicated on ], ]; about four months after Nauvoo was abandoned by the majority of the citizens. The temple was burned in ] and the remnants of the structure were destroyed by a ] later that year. The Church retained ownership of the site and converted it into a landmark with the temple's cornerstones still in place. This remained until 2002 when, after an exact reconstruction project, the temple was rededicated. | |||

| ===Successors and denominations=== | |||

| Nauvoo's population peaked in ] when it may have had as many as 12,000 inhabitants — rivaling ], whose 1845 population was about 15,000. | |||

| {{See also|Succession crisis (Latter Day Saints)|List of denominations in the Latter Day Saint movement}} | |||

| Smith's death resulted in a succession crisis within the Latter Day Saint movement.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=143}}; {{Harvtxt|Brodie|1971|p=398}}</ref> He had proposed several ways to choose his successor, but never clarified his preference.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Shipps|1985|pp=83–84}}; {{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|p=143}}; {{Harvtxt|Davenport|2022|p=159}}</ref> The two strongest succession candidates were Young, senior member and president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and Rigdon, the senior remaining member of the First Presidency. In a church-wide conference on August 8, most of the Latter Day Saints present elected Young. They eventually left Nauvoo and settled the ], ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=556–557}}; {{Harvtxt|Davenport|2022|p=163}}</ref> | |||

| Nominal membership in Young's denomination, which became the LDS Church, surpassed 17 million in 2023.<ref>{{cite news |last=Walch |first=Tad |date=April 6, 2024 |title=Latter-day Saint membership passed 17.25 million in 2023, according to new church statistical report |work=Deseret News |url=https://www.deseret.com/faith/2024/04/06/latter-day-saint-mormon-membership-increased-this-much-in-2023-church-statistical-report/}}</ref> Smaller groups followed Rigdon and ], who had based his claim on a ] ostensibly written by Smith but which some scholars believe was ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Bushman|2005|pp=555–557}}</ref> Some hundreds followed ] to establish a community in Texas.<ref>{{Harvtxt|McBride|2021|p=205}}</ref> Others followed ].<ref>{{Harvtxt|Quinn|1994|pp=198–09}}</ref> Many members of these smaller groups, including most of Smith's family,<ref>{{cite podcast |url=https://www.projectzionpodcast.org/podcast/519-cuppa-joe-theo-history-plano-period/ |title=Theo-History: Plano Period |website=Cuppa Joe |publisher=Project Zion Podcast |date=October 14, 2022 |time=1:52 and 9:47 |last=Peter |first=Karin |last2=Mackay |first2=Lachlan |last3=Chvala-Smith |first3=Tony}}</ref> eventually coalesced in 1860<ref>{{Cite web |last=Howlett |first=David J. |date=December 11, 2022 |title=Community of Christ |url=https://wrldrels.org/2022/12/11/21325/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230110200318/https://wrldrels.org/2022/12/11/21325/ |archive-date=January 10, 2023 |website=World Religions and Spirituality Project |postscript=none}}</ref> under the leadership of ] and formed the RLDS Church (Community of Christ), which has about 250,000 members.<ref>{{Cite web |date=April 15, 2004 |title=Community of Christ |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Community-of-Christ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123023756/https://www.britannica.com/topic/Community-of-Christ |archive-date=January 23, 2023 |website=] |postscript=none}}</ref> | |||

| ===Controversy in the City Beautiful=== | |||

| On the evening of ], ], a gunman shot through a window in Governor Boggs' home, hitting him four times. Sheriff J.H. Reynolds discovered a revolver at the scene, still loaded with ] and surmised that the suspect lost his firearm in the dark rainy night. | |||

| ==Family and descendants== | |||