| Revision as of 16:20, 7 May 2008 editPiCo (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers44,429 edits Undid revision 210817052 by FaithF (talk)Faith, please take this to the Talk page and refrain from edit warring.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:19, 16 January 2025 edit undoDMacks (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Administrators187,055 editsm Reverted edit by 187.37.0.114 (talk) to last version by Feline HymnicTag: Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Hypothesis to explain the origins and composition of the Torah}} | |||

| {{redirect-acronym|JEPD|], ]}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}} | |||

| [[Image:Modern document hypothesis.svg|thumb|240px| | |||

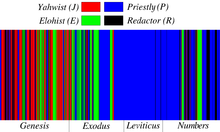

| [[File:Modern document hypothesis.svg|thumb|Diagram of the 20th century documentary hypothesis: | |||

| Diagram of the Documentary Hypothesis. | |||

| {{unbulleted list|J: ] (10th–9th century BCE){{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40}}{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|p=4}}|E: ] (9th century BCE){{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40}}|Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) ] historian|Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) ] historian|P*: ] (6th–5th century BCE){{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=41}}{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|p=4}}|D†: ]|R: redactor|DH: ] (books of ], ], ], ])}}]] | |||

| {| style="background:none" | |||

| |<nowiki>*</nowiki>||includes most of Leviticus | |||

| |- valign="top" | |||

| |<sup>†</sup>||includes most of Deuteronomy | |||

| |- valign="top" | |||

| |<sup>‡</sup>||"''Deuteronomic history''": Joshua, Judges, 1 & 2 Samuel, 1& 2 Kings | |||

| |} | |||

| ]] | |||

| The '''documentary hypothesis (DH)''' proposes that the first five books of the ] (], ], ], ] and ], known collectively as the ] or ]), represent a combination of documents from four originally independent sources. According to the influential version of the hypothesis formulated by ] (1844 - 1918) these sources and the approximate dates of their composition were: | |||

| * the J, or ], source; written c. 950 BC in the southern kingdom of Judah. (The name '']'' begins with a J in Wellhausen's native German.) | |||

| * the E, or ], source; written c. 850 BC in the northern kingdom of Israel. | |||

| * the D, or ], source; written c. 621 BC in Jerusalem during a period of religious reform. | |||

| * the P, or ], source; written c. 450 BC by Aaronid priests. | |||

| The editor who combined the sources into the final Pentateuch is known as R, for ], and might have been ]. | |||

| The '''documentary hypothesis''' ('''DH''') is one of the models used by biblical scholars to explain the origins and ] (or ], the first five books of the Bible: ], ], ], ], and ]).{{sfn|Patzia|Petrotta|2010|p=37}} A version of the documentary hypothesis, frequently identified with the German scholar ], was almost universally accepted for most of the 20th century.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=434}} It posited that the Pentateuch is a compilation of four originally independent documents: the ], ], ], and ] sources, frequently referred to by their initials.<ref group="Note">hence the alternative name ''JEDP'' for the documentary hypothesis</ref> The first of these, J, was dated to the ] (c. 950 BCE).{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40}} E was dated somewhat later, in the 9th century BCE, and D was dated just before the reign of ], in the 7th or 8th century BCE. Finally, P was generally dated to the time of ] in the 5th century BCE.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=41}}{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|p=4}} The sources would have been joined at various points in time by a series of editors or "redactors".{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=viii}} | |||

| :"Starting from the simple question of how to reconcile inconsistencies in the text, and refusing to accept forced explanations to harmonize them, scholars eventually arrived at the theory that the Torah was composed of selections woven together from several, at times inconsistent, sources dealing with the same and related subjects. The reasoning followed in this kind of analysis is somewhat similar to that of the Talmudic sages and later rabbis who held that inconsistent clauses and terminology in a single paragraph of the Mishna must have originated with different sages, and who recognized that Moses could not have written passages of the Torah that contain information unavailable to him, such as the last chapter of Deuteronomy, which describes his death and its aftermath."<ref>Jeffrey Tigay, JPS Torah Commentary on Deuteronomy, p. 502, quoted in </ref> | |||

| The consensus around the classical documentary hypothesis has now collapsed.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=434}} This was triggered in large part by the influential publications of ], ], and ] in the mid-1970s,{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=41}} who argued that J was to be dated no earlier than the time of the ] (597–539 BCE),{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|pp=41–43}} and rejected the existence of a substantial E source.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=436}} They also called into question the nature and extent of the three other sources. Van Seters, Schmid, and Rendtorff shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in complete agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=41}} As a result, there has been a revival of interest in "fragmentary" and "]" models, frequently in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=12}} Modern scholars also have given up the classical Wellhausian dating of the sources, and generally see the completed Torah as a product of the time of the Persian ] (probably 450–350 BCE), although some would place its production as late as the ] (333–164 BCE), after the conquests of ].{{sfn|Greifenhagen|2003|pp=206–207, 224 fn.49}} | |||

| According to Wellhausen, the four sources present a picture of Israel's religious history, which he saw as one of ever-increasing centralization and priestly power. Wellhausen's hypothesis became the dominant view on the origin of the Pentateuch for much of the 20th century. Most contemporary Bible experts accept some form of the documentary hypothesis,<ref name =”Harris”>], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> and scholars continue to draw on Wellhausen's terminology and insights.<ref>]. </ref> | |||

| == History of the documentary hypothesis == | |||

| {{BibleRelated}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ] (or Pentateuch) is collectively the first five books of the Bible: ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|McDermott|2002|p=1}} According to tradition, they were dictated by God to Moses,{{sfn|Kugel|2008|p=6}} but when modern critical scholarship began to be applied to the Bible, it was discovered that the Pentateuch was not the unified text one would expect from a single author.{{sfn|Campbell|O'Brien|1993|p=1}} As a result, the ] of the Torah had been largely rejected by leading scholars by the 17th century, with many modern scholars viewing it as a product of a long evolutionary process.{{sfn|Berlin|1994|p=113}}{{sfn|Baden|2012|p=13}}<ref group="Note" name="Moses">The reasons behind the rejection are covered in more detail in the article on ].</ref> | |||

| In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah.{{sfn|Berlin|1994|p=113}} In 1780, ], building on the work of the French doctor and ] ]'s "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the ] ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the ] ("E").{{sfn|Ruddick|1990|p=246}} These sources were subsequently found to run through the first four books of the Torah, and the number was later expanded to three when ] identified the ] as an additional source found only in Deuteronomy ("D").{{sfn|Patrick|2013|p=31}} Later still the Elohist was split into Elohist and ] ("P") sources, increasing the number to four.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=19}} | |||

| ==Composition of the Torah== | |||

| Following Wellhausen, scholars speak of four major sources for the Torah. | |||

| ===J, Jahwist source=== | |||

| {{main|Jahwist}} | |||

| The oldest source, concerned with narratives, making up half of Genesis and the first half of Exodus, plus fragments of Numbers. J describes a human-like ], called '']'' (or rather ]) throughout, and has a special interest in the territory of the ] and individuals connected with its history. J has an eloquent style. Originally composed c. 950 BC.<ref name =”Harris”>], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> | |||

| These documentary approaches were in competition with two other models, the fragmentary and the ].{{sfn|Viviano|1999|pp=38–39}} The fragmentary hypothesis argued that fragments of varying lengths, rather than continuous documents, lay behind the Torah; this approach accounted for the Torah's diversity but could not account for its structural consistency, particularly regarding chronology.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=38}} The supplementary hypothesis was better able to explain this unity: it maintained that the Torah was made up of a central core document, the Elohist, supplemented by fragments taken from many sources.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=38}} The supplementary approach was dominant by the early 1860s, but it was challenged by an important book published by ] in 1853, who argued that the Pentateuch was made up of four documentary sources, the Priestly, Yahwist, and Elohist intertwined in Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers, and the stand-alone source of Deuteronomy.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=18–19}} At around the same period, ] argued that the Yahwist and Elohist were the earliest sources and the Priestly source the latest, while ] linked the four to an evolutionary framework: the Yahwist and Elohist to a time of primitive nature and fertility cults, the Deuteronomist to the ethical religion of the Hebrew prophets, and the Priestly source to a form of religion dominated by ritual, sacrifice and law.{{sfn|Friedman|1997|p=24–25}} | |||

| ===E, Elohist source=== | |||

| {{main|Elohist}} | |||

| E parallels J, often duplicating the narratives. Makes up a third of Genesis and the first half of Exodus, plus fragments of Numbers. E describes a human-like God initially called ''Elohim'', and ''Yahweh'' subsequent to the incident of the ], at which Elohim reveals himself as Yahweh. E focuses on the ] and on the ] priesthood, has a moderately eloquent style. Originally composed c. 850 BC.<ref name =”Harris”>], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> | |||

| === Wellhausen and the new documentary hypothesis === | |||

| ===D, Deuteronomist source=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Deuteronomist}} | |||

| In 1878, ] published ''Geschichte Israels, Bd 1'' ('History of Israel, Vol 1').{{sfn|Wellhausen|1878}} The second edition was printed as '']'' ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel") in 1883,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1883}} and the work is better known under that name.{{sfn|Kugel|2008|p=41}} (The second volume, a synthetic history titled ''Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte'' ,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1894}} did not appear until 1894 and remains untranslated.) Crucially, this historical portrait was based upon two earlier works of his technical analysis: "Die Composition des Hexateuchs" ('The Composition of the Hexateuch') of 1876–77, and sections on the "historical books" (Judges–Kings) in his 1878 edition of ]'s ''Einleitung in das Alte Testament'' ('Introduction to the Old Testament'). | |||

| D takes the form of a series of sermons about the Law, and consists of most of ]. Its distinctive term for God is ''YHWH Elohainu'', translated in English as "The Lord our God." Originally composed c. 650-621 BC.<ref name =”Harris”>], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> | |||

| Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis owed little to Wellhausen himself but was mainly the work of Hupfeld, ], Graf, and others, who in turn had built on earlier scholarship.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=20}} He accepted Hupfeld's four sources and, in agreement with Graf, placed the Priestly work last.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=19}} J was the earliest document, a product of the 10th century BCE and the court of ]; E was from the 9th century BCE in the northern ], and had been combined by a redactor (editor) with J to form a document JE; D, the third source, was a product of the 7th century BCE, by 620 BCE, during the reign of ]; P (what Wellhausen first named "Q") was a product of the priest-and-temple dominated world of the 6th century BCE; and the final redaction, when P was combined with JED to produce the Torah as we now know it.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=40–41}}{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=260}} | |||

| ===P, Priestly source=== | |||

| {{main|Priestly source}} | |||

| Preoccupied with the centrality of the priesthood, and with lists (especially genealogies), dates, numbers and laws. P describes a distant and unmerciful God, referred to as ''Elohim''. P partly duplicates J and E, but alters details to stress the importance of the priesthood. P consists of about a fifth of Genesis, substantial portions of Exodus and Numbers, and almost all of ]. P has a low level of literary style. Composed c. 550-400 BC.<ref name =”Harris”>], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> | |||

| Wellhausen's explanation of the formation of the Torah was also an explanation of the religious history of Israel.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=260}} The Yahwist and Elohist described a primitive, spontaneous, and personal world, in keeping with the earliest stage of Israel's history; in Deuteronomy, he saw the influence of the prophets and the development of an ethical outlook, which he felt represented the pinnacle of Jewish religion; and the Priestly source reflected the rigid, ritualistic world of the priest-dominated, post-exilic period.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=51}} His work, notable for its detailed and wide-ranging scholarship and close argument, entrenched the "new documentary hypothesis" as the dominant explanation of Pentateuchal origins from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.{{sfn|Barton|Muddiman|2010|p=19}}<ref group="Note" name="newer">The two-source hypothesis of Eichhorn was the "older" documentary hypothesis, and the four-source hypothesis adopted by Wellhausen was the "newer".</ref> | |||

| ===Composition=== | |||

| The redaction of the Torah began with the combination of J and E to create JE, ''c'' 750. The addition of D created JED. The redactors associated with P put the work into its final form ''c'' 400. | |||

| == |

== Critical reassessment == | ||

| ] | |||

| <!-- Unsourced image removed: ] proposed in the ''Tractatus theologico-politicus'' (1670) that ], not ], was the true author of the ].|{{deletable image-caption|1=Thursday, 17 April 2008}}]] --> | |||

| In the mid to late 20th century, new criticism of the documentary hypothesis formed.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=434}} Three major publications of the 1970s caused scholars to reevaluate the assumptions of the documentary hypothesis: '']'' by ], ''Der sogenannte Jahwist'' ("The So-Called Yahwist") by ], and ''Das überlieferungsgeschichtliche Problem des Pentateuch'' ("The Tradition-Historical Problem of the Pentateuch") by ]. These three authors shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=41}} | |||

| === Mosaic authorship === | |||

| Prior to the 17th century both Jews and Christians accepted the traditional view that ] had written down the ] under the direct inspiration—even dictation—of God. A few rabbis and philosophers asked how Moses could have described his own death, or given a list of the kings of ] before those kings ever lived, but none doubted the truth of the tradition, for the purpose of scholarship "was to underline the antiquity and authority of the teaching in the Pentateuch, not to demonstrate who wrote the books."<ref>]. "Exploring the Old Testament: Vol. 1, the Pentateuch," p160 (2003).</ref> | |||

| Van Seters and Schmid both forcefully argued that the Yahwist source could not be dated to the ] (c. 950 BCE) as posited by the documentary hypothesis. They instead dated J to the period of the ] (597–539 BCE), or the late monarchic{{clarify|date=November 2024|reason=unclear to lay reader: needs a wikilink}} period at the earliest.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|pp=41–43}} Van Seters also sharply criticized the idea of a substantial Elohist source, arguing that E extends at most to two short passages in Genesis.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=42}} | |||

| === The beginnings of the documentary hypothesis === | |||

| In ] ], in chapter 33 of ''Leviathan'', marshaled a battery of evidence that the Pentateuch could not all be by Moses, noting passages such as Deut 34:6 ("no man knoweth of his sepulchre to this day," implying an author living long after Moses' death); Gen 12:6 ("and the ] was then in the land," implying an author living in a time when the Canaanite was no longer in the land); and Num 21:14 (referring to a previous book of Moses' deeds), and concluded that none of these could be by Moses. Others, including ], ], ], and ] came to the same conclusion, but their works were condemned, several of them were imprisoned and forced to recant, and an attempt was made on Spinoza's life.<ref>For a brief overview of the Enlightenment struggle between scholarship and authority, see Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?", pp.20-21 (hardback original 1987, paperback HarperCollins edition 1989).</ref> | |||

| Some scholars, following Rendtorff, have come to espouse a fragmentary hypothesis, in which the Pentateuch is seen as a compilation of short, independent narratives, which were gradually brought together into larger units in two editorial phases: the Deuteronomic and the Priestly phases.{{sfn|Viviano|1999|p=49}}{{sfn|Thompson|2000|p=8}}{{sfn|Ska|2014|pp=133–135}} By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a ], which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=77}} | |||

| In 1753 ] printed (anonymously) ''Conjectures sur les memoires originaux, dont il parait que Moses s'est servi pour composer le livre de la Genèse'' ("Conjectures on the original accounts of which it appears Moses availed himself in composing the Book of Genesis"). Astruc's motive was to refute Hobbes and Spinoza - "the sickness of the last century," as he called their work. To do this, he applied to Genesis the tools of literary analysis which scholars were already using with Classical texts such as the ] to sift variant traditions and arrive at the most authentic text. He began by identifying two markers which seemed to identify consistent variations, the use of "Elohim" or "YHWH" (Yahweh) as the name for God, and the appearance of duplicated stories, or ], such as the two accounts of the creation in the first and second chapters of Genesis and the two accounts of Sarah and a foreign king (Gen.12 and Gen.20). He then ruled columns and assigned verses to these, the "Elohim" verses in one column, the "YHWH" verses in another, and the members of the doublets in their own columns beside these. The four parallel columns thus constructed contained two long narratives and two short ones. Astruc suggested that these were the original documents used by Moses, and that Genesis as written by Moses had looked just like this, four parallel accounts meant to be read separately. According to Astruc, a later editor had combined the four columns into a single narrative, creating the confusions and repetitions noted by Hobbes and Spinoza.<ref>Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: Volume 1, the Pentateuch", (2003), PP.162-163.</ref> | |||

| Some scholars use these newer hypotheses in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another.{{sfn|Van Seters|2015|p=12}} The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of ] as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses.{{sfn|Otto|2014|p=605}} Most scholars also agree that some form of Priestly source existed, although its extent, especially its end-point, is uncertain.{{sfn|Carr|2014|p=457}} The remainder is called collectively non-Priestly, a grouping which includes both pre-Priestly and post-Priestly material.{{sfn|Otto|2014|p=609}} | |||

| The tools adapted by Astruc for biblical ] were vastly developed by subsequent scholars, most of them German. From 1780 onwards ] extended Astruc's analysis beyond Genesis to the entire Pentateuch, and by ] he had concluded that Moses had had no part in writing any of it. In 1805 ] concluded that ] represented a third independent source. About ] ] identified ] as a continuation of the Pentateuch via Deuteronomy, while others identified signs of the Deuteronomist in ], ], and ]. In 1853 ] suggested that the Elohist was really two sources and should be split, thus isolating the Priestly source; Hupfeld also emphasized the importance of the Redactor, or final editor, in producing the Torah from the four sources. Not all the Pentateuch was traced to one or other of the four sources: numerous smaller sections were identified, such as the ] contained in ] 17 to 26.<ref>, and Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?", pp.22-24.</ref> | |||

| The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the ] (539–333 BCE).{{sfn|Greifenhagen|2003|pp=206–207}}{{sfn|Whisenant|2010|p=679|ps=, "Instead of a compilation of discrete sources collected and combined by a final redactor, the Pentateuch is seen as a sophisticated scribal composition in which diverse earlier traditions have been shaped into a coherent narrative presenting a creation-to-wilderness story of origins for the entity 'Israel.'"}} A minority of scholars would place its final compilation somewhat later, however, in the ] (333–164 BCE).{{sfn|Greifenhagen|2003|pp=206–207, 224 n. 49}} | |||

| Scholars also attempted to identify the sequence and dates of the four sources, and to propose who might have produced them, and why. De Wette had concluded in 1805 that none of the Pentateuch was composed before the time of ]; Since Spinoza, D was connected with the priests of the Temple in Jerusalem during the reign of ] in ]; beyond this, scholars argued variously for composition in the order PEJD, or EJDP, or JEDP: the subject was far from settled.<ref>Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?", p.25., and Alexander Rofe, "Introduction to the Composition of the Pentateuch", (1999), ch.2. See also .</ref> | |||

| A revised neo-documentary hypothesis still has adherents, especially in North America and Israel.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=271}} This distinguishes sources by means of plot and continuity rather than stylistic and linguistic concerns, and does not tie them to stages in the evolution of Israel's religious history.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=271}} Its resurrection of an E source is probably the element most often criticised by other scholars, as it is rarely distinguishable from the classical J source and European scholars have largely rejected it as fragmentary or non-existent.{{sfn|Gaines|2015|p=272}} | |||

| == The Wellhausen (or Graf-Wellhausen) hypothesis == | |||

| == The Torah and the history of Israel's religion == | |||

| In 1876/77 ] published ''Die Komposition des Hexateuch'' ("The Composition of the Hexateuch"), in which he set out the four-source hypothesis of Pentateuchal origins; this was followed in 1878 by '']'' ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel"), a work which traced the development of the religion of the ancient Israelites from an entirely secular, non-supernatural standpoint. Wellhausen contributed little that was new,{{Fact|date=December 2007}} but sifted and combined the previous century of scholarship into a coherent, comprehensive theory on the origins of the Torah and of Judaism, one so persuasive that it dominated scholarly debate on the subject for the next hundred years.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} | |||

| {{See also|History of ancient Israel and Judah|Origins of Judaism}} | |||

| Wellhausen used the sources of the Torah as evidence of changes in the history of Israelite religion as it moved (in his opinion) from free, simple and natural to fixed, formal and institutional.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=182}} Modern scholars of Israel's religion have become much more circumspect in how they use the Old Testament, not least because many have concluded that the Hebrew Bible is not a reliable witness to the religion of ancient Israel and Judah,<ref name="Lupovitch">{{cite book |last1=Lupovitch |first1=Howard N. |date=2010 |title=Jews and Judaism in World History |chapter=The world of the Hebrew Bible |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s7uLAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA5 |location=] |publisher=] |pages=5–10 |isbn=978-0-203-86197-4}}</ref> representing instead the beliefs of only a small segment of the ancient Israelite community centered in ] and devoted to the exclusive worship of the god ].{{sfn|Stackert|2014|p=24}}{{sfn|Wright|2002|p=52}} | |||

| === Distinguishing the sources === | |||

| Wellhausen's criteria for distinguishing between sources were those developed by his predecessors over the previous century: style (including but not exclusively the choice of vocabulary); divine names; doublets and occasionally triplets. J was identified with a rich narrative style, E was somewhat less eloquent, P's language was dry and legalistic. Vocabulary items such as the names of God, or the use of Horeb (E and D) or Sinai (J and P) for God's mountain; ritual objects such as the ], mentioned frequently in J but never in E; the status of judges (never mentioned in P) and prophets (mentioned only in E and D); the means of communication between God and man (J's God meets in person with Adam and Abraham, E's God communicates through dreams, P's can only be approached through the priesthood): all these and more formed the toolkit for discriminating between sources and allocating verses to them.<ref>Richard Elliott Friedman, "The Bible with Sources Revealed", 2003; and .</ref> | |||

| === Dating the sources === | |||

| ] with ]]] | |||

| Wellhausen's starting point for dating the sources was the event described in 2 Kings 22:8-20: a "scroll of Torah" (which can be translated "instruction" or "law") is discovered in the Temple in Jerusalem by the High Priest ] in the eighteenth year of king ], who had ascended the throne as a child of eight. What Josiah reads there causes him to embark on a campaign of religious reform, destroying all altars except that in the Temple, prohibiting all sacrifice except at the Temple, and insisting on the exclusive worship of Yahweh. In the 4th century ] had speculated that the scroll may have been Deuteronomy; de Wette in 1805 suggested that it might have been only the law-code at Deuteronomy 12-26 that Hilkiah found, and that he might have written it himself, alone or in collaboration with Josiah. The Deuteronomistic historian certainly held Josiah in high regard: 1 Kings 13 names him as one who will be sent by Yahweh to slaughter the apostate priests of ], in a prophecy allegedly made 300 years before his birth. <ref>Richard Elliott Friedman, "Who Wrote the Bible?" esp. p.188 ff.</ref> | |||

| With D anchored in history, Wellhausen proceeded to place the remaining sources around it. He accepted ]'s conclusion that the sources were written in the order J-E-D-P. This was contrary to the general opinion of scholars at the time, who saw P as the earliest of the sources, "the official guide to approved divine worship", and Wellhausen's sustained argument for a late P was the great innovation of the ''Prolegomena''.<ref>Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament", p.171.</ref> J and E he ascribed to the early monarchy, approximately 950 BCE for J and 850 BCE for E; P he placed in the early Persian post-Exilic period, around 500 BCE. His argument for these dates was based on what was seen in his day as the natural evolution of religious practice: in the pre-and early monarchic society described in Genesis and Judges and Samuel, altars were erected wherever the Patriarchs or heroes such as ] chose, anyone could offer the sacrifice, and portions were offered to priests as the one offering the sacrifice chose; by the late monarchy sacrifice was beginning to be centralized and controlled by the priesthood, while pan-Israelite festivals such as ] were instituted to tie the people to the monarch in a joint celebration of national history; in post-Exilic times the temple in Jerusalem was firmly established as the only sanctuary, only the descendants of ] could offer sacrifices, festivals were linked to the calendar instead of to the seasons, and the schedule of priestly entitlements was strictly mandated.<ref>This is a highly schematised account of a complex argument: see Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament", pp.167-171.</ref> | |||

| The four were combined by a series of Redactors (editors), first J with E to form a combined JE, then JE with D to form a JED text, and finally JED with P to form JEDP, the final Torah. Taking up a scholarly tradition stretching back to Spinoza and Hobbes, Wellhausen named ], the post-Exilic leader who re-established the Jewish community in Jerusalem at the behest of the Persian emperor ] in 458 BC, as the final redactor | |||

| == After Wellhausen == | |||

| For much of the 20th century Wellhausen's hypothesis formed the framework within which the origins of the Pentateuch were discussed, and even the ], a staunch critic of secular biblical scholarship in the 19th century, came to accept the methods, if not the findings, of ] and ].<ref>"Let the interpreter then, with all care and without neglecting any light derived from recent research, endeavor to determine the peculiar character and circumstances of the sacred writer, the age in which he lived, the sources written or oral to which he had recourse and the forms of expression he employed." , 1943.</ref> Some important modifications were introduced, notably by ] and ], who argued for the oral transmission of ancient core beliefs - guidance out of Egypt, conquest of the Promised Land, covenants, revelation at Sinai/Horeb, etc.<ref>Albecht Alt, "The God of the Fathers", 1929, and Martin Noth, "A History of Pentateuchal Traditions", 1948.</ref> Simultaneously, the work of the American school of ] such as ] and ] seemed to confirm that even if ] and ] were only given their final form in the first millennium BC, they were still firmly grounded in the material reality of the second millennium.<ref>, an overview of archaeology and the Patriarchal period.</ref> The overall effect of such refinements was to aid the wider acceptance of the basic hypothesis, by reassuring believers that even if the final form of the Pentateuch was not due to Moses himself, and "despite the late date of the Pentateuch, we can nevertheless recover a credible picture of the period of Moses and even of the patriarchal age. Hence opposition to the documentary hypothesis gradually waned, and by the mid-twentieth century it was almost universally accepted."<ref></ref> | |||

| The collapse of the consensus began in the late 1960s, with the spread of new scholarly tools and a growing recognition of the limitations of Wellhausen's analytical framework. The result has been proposals which modify the documentary model so far as to become unrecognizable, or even abandon it entirely in favour of alternative models which see the Pentateuch as the product of a single author, or as the end-point of a process of creation by the entire community. Thus, to mention some of the major figures from the last decades of the 20th century, ] almost completely eliminated J, allowing only a late Deuteronomical redactor;<ref>H. H. Schmid, "Der sogenannte Jahwist" (''"The So-called Yahwist"''), 1976.</ref> ] and ] saw the Pentateuch developing from the gradual accretion of small units into larger and larger works, a process which removes both J and E, and, significantly, implied a supplemental rather than a documentary model for Old Testament origins;<ref>Rolf Rendtdorff, ''The Problem of the Process of Transmission in the Pentateuch,'' Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement 89, 1990.</ref> and ], using a similar model, envisaged an ongoing process of supplementation in which later authors modified earlier compositions and changed the focus of the narratives.<ref>John Van Seters, "Abraham in History and Tradition", 1975.</ref> With the idea of identifiable sources disappearing, the question of dating also changes its terms. The most radical contemporary proposal has come from ], who suggests that the final redaction of the Torah occurred as late as the early ] monarchy.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} | |||

| The challenge to the Wellhausen consensus was perhaps best summed up by ], who pointed out that of the various possible models for the composition of the Pentateuch - documentary, supplemental and fragmentary - the documentary was the most difficult to demonstrate, for while the supplemental and fragmentary models propose relatively simple, logical processes and can account for the unevenness of the final text, the process envisaged by the DH is both complex and extremely specific in its assumptions about ancient Israel and the development of its religion. Whybray went on to assert that these assumptions were illogical and contradictory, and did not offer real explanatory power: why, for example, should the authors of the separate sources avoid duplication, while the final redactor accepted it? "Thus the hypothesis can only be maintained on the assumption that, while consistency was the hallmark of the various documents, inconsistency was the hallmark of the redactors!"<ref>R.N. Whybray, "The Making of the Pentateuch", 1987, quoted in Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament", 2003, pp.173-174.</ref> | |||

| ]'s "Who Wrote the Bible?" (1987) and "]" (2003) were in essence an extended response to Whybray, explaining, in terms based on the history of ancient Israel, how the redactors could have tolerated inconsistency, contradiction and repetition, indeed had it forced upon them by the historical setting in which they worked. Friedman's classic four-source division differed from Wellhausen in accepting ]'s dating of P to the reign of ];<ref>Yehezkel Kaufmann, "The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile", 1961.</ref> this in itself is no small modification of Wellhausen, for whom a late dating of P was essential to his model of the historical development of Israelite religion. Friedman argued that J appeared a little before 722 BCE, followed by E, and a combined JE soon after that. P was written as a rebuttal of JE (c. 715-687 BCE), and D was the last to appear, at the time of Josiah (c. 622 BCE), before the Redactor, whom Friedman identifies as Ezra, collated the final Torah. | |||

| Antony F. Campbell and Mark A. O’Brien's "Sources of the Pentateuch" subsequently presented the Pentateuchal text sorted into continuous sources following the divisions of Martin Noth. But while the terminology and insights of the documentary hypothesis continue to inform scholarly debate about the origins of the Pentateuch, it no longer dominates that debate as it did for the first two thirds of the 20th century.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ], Jewish scholar who was critical of the documentary hypothesis | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], a similar theory for the construction of the ] | |||

| * ] (19th century literary hoax with bearing on the DH) | |||

| == Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| {{Reflist |group="Note"}} | |||

| <!--See http://en.wikipedia.org/Wikipedia:Footnotes for an explanation of how to generate footnotes using the <ref(erences/)> tags--> | |||

| <references/> | |||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| * ]. ''A Survey of Old Testament Introduction.'' Chicago: Moody, 1994. | |||

| * Blenkinsopp, Joseph ''The Pentateuch : an introduction to the first five books of the Bible'', Doubleday, NY, USA 1992. ISBN 038541207X | |||

| * ] and Rosenberg, David ''The Book of J'', Random House, NY, USA 1990. ISBN 0-8021-4191-9. | |||

| * ] "Gods and Heroes of the Levant: 1500–500 B.C." ''The Masks of God 3: Occidental Mythology'', Penguin Books, NY, USA, 1964. | |||

| * Campbell, Antony F., and O’Brien, Mark A. ''Sources of the Pentateuch'', Fortress, Minneapolis, 1993. | |||

| * Clines, David J. A. ''The Theme of the Pentateuch.'' JSOTSup. 10. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1978. | |||

| * ] ''What Did The Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?'' William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2001. ISBN 0-8028-4794-3 | |||

| * ] and ] ''The Bible Unearthed'', Simon and Schuster, NY, USA, 2001. ISBN 0-684-86912-8 | |||

| * ], ''The Unauthorized Version''. A classics scholar offers a measured view for the layman. | |||

| * ] ''Who Wrote The Bible?'', Harper and Row, NY, USA, 1987. ISBN 0-06-063035-3. This work does not constitute a standard reference for the documentary hypothesis, as Friedman in part describes his own theory of the origin of one of the sources. Rather, it offers an excellent introduction for the layman. | |||

| * ] ''The Hidden Book in the Bible'', HarperSan Francisco, NY, USA, 1998. | |||

| * ] ''The Bible with Sources Revealed'', HarperSanFrancisco, 2003. ISBN 0-06-053069-3. | |||

| * Garrett, Duane A. ''Rethinking Genesis: The Sources and Authorship of the First Book of the Bible'', Mentor, 2003. ISBN 1-85792-576-9. | |||

| * Kaufmann, Yehezkel, ''The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile'', University of Chicago Press, 1960. (Translated by Moishe Greenberg) | |||

| * Mendenhall, George E. ''The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition'', The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973. | |||

| * Mendenhall, George E. ''Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context'', Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0-664-22313-3 | |||

| * Nicholson, Ernest Wilson. ''The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen'', Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0198269587 | |||

| * Rofe, Alexander. ''Introduction to the Composition of the Pentateuch'', Sheffield Academic Press, 1999. | |||

| * Rogerson, J. ''Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century: England and Germany'', SPCK/Fortress, 1985. | |||

| * Shafer, Kenneth W. ''Searching for J'', Gateway Press, Baltimore, 2003, ISBN 0-9747457-1-5, (Amazon) | |||

| * ] ''A Theologico-Political Treatise'' Dover, New York, USA, 1951, Chapter 8. | |||

| * Tigay, Jeffrey H. "An Empirical Basis for the Documentary Hypothesis" ''Journal of Biblical Literature'' Vol.94, No.3 Sept. 1975, pages 329–342. | |||

| * Tigay, Jeffrey H., (ed.) ''Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism'' University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, USA 1986. ISBN 081227976X | |||

| * Van Seters, John. ''Abraham in History and Tradition'' Yale University Press, 1975. | |||

| * Van Seters, John. ''In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History'' Yale University Press, 1983. | |||

| * Van Seters, John. ''Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis'' Westminster/John Knox, Louisville, Kentucky, 1992. ISBN 0664219675 | |||

| * Van Seters, John. ''The Life of Moses: The Yahwist as Historian in Exodus–Numbers'' Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox, 1994. ISBN 0-664-22363-X | |||

| * , (the first English edition, with William Robertson Smith's Preface, from Project Guttenberg) | |||

| * Wenham, Gordon. "", ''Themelios'' 22.1 (October 1996): 3–13. | |||

| * Whybray, R. N. ''The Making of the Pentateuch: A Methodological Study'' JSOTSup 53. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987. | |||

| == |

== Bibliography == | ||

| {{Refbegin|}} | |||

| * Explanation of the DH, based on the Anchor Bible Dictionary entry on source criticism. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Baden|first=Joel S.|title=The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis|publisher=Yale University Press|year=2012|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Beg7LeeNGlkC|isbn=978-0-300-15263-0|series=Anchor Yale Reference Library}} | |||

| * A brief overview of the history of the DH, concentrating on the work of major scholars. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Barton|first=John|chapter=Biblical Scholarship on the European Continent, in the UK, and Ireland|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rMzUBQAAQBAJ&q=%22sure+of+only+two+things+about+the+sources+of+the+Pentateuch%22&pg=PA311|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| * | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Barton|first1=John|last2=Muddiman|first2=John|title=The Pentateuch|year=2010|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ldMUDAAAQBAJ&q=%221860s%22%22leading+scholars%22%22supplementary+hypothesis%22&pg=PA18|isbn=978-0-19-958024-8}} | |||

| * — from SimpleToRemember.com Judaism Online website: a conservative Jewish Orthodox analysis of the DH. | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Berlin|first=Adele|title=Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative|publisher=Eisenbrauns|year=1994|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eLoBhPENIBQC&q=%22source+criticism%22%22detecting+in+the+text+evidence+of+its+earlier+stages%22&pg=PA113|isbn=978-1-57506-002-6}} | |||

| * | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism |last=Berman |first=Joshua A. |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2017 |isbn=978-0-19-065880-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rWBwvgAACAAJ}} | |||

| * | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Brettler|first=Marc Zvi|editor1-last=Berlin|editor1-first=Adele|editor2-last=Brettler|editor2-first=Marc Zvi|title=The Jewish Study Bible|chapter=Torah: Introduction|date=2004|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780195297515|url-access=registration|isbn=978-0-19-529751-5}} | |||

| * Smith, Colin: , June 2002. Retrieved from the Alpha and Omega Ministries website on ] 2006. | |||

| *{{cite book|last1=Campbell|first1=Antony F.|last2=O'Brien|first2=Mark A.|title=Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations|publisher=Fortress Press|year=1993|url=https://archive.org/details/sourcesofpentate0000camp|url-access=registration|isbn=978-1-4514-1367-0}} | |||

| * | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Carr|first1=David M.|chapter=Genesis|editor1-last=Coogan|editor1-first=Michael David|editor2-last=Brettler|editor2-first=Marc Zvi|editor3-last=Newsom|editor3-first=Carol Ann|title=The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2007|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=%22collapse+of+consensus%22%22debate+surrounding+virtually+every+aspect%22&pg=PA434|isbn=978-0-19-528880-3}} | |||

| * on Religioustolerance.org, with the first ten chapters of Genesis color-coded by source | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Carr|first=David M.|chapter=Changes in Pentateuchal Criticism|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=could+be+presupposed+as+a+givenfor+over+a+hundred+years&pg=PA434|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| * . "New Directions in Pooh Stiudies". A humorous look at the pitfalls of various critical methodologies, including source criticism and its most famous offspring, the documentary hypothesis. | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch|last=Frei|first=Peter|publisher=SBL Press|year=2001|isbn=9781589830158|location=Atlanta, GA|pages=6|editor-last=Watts|editor-first=James|chapter=Persian Imperial Authorization: A Summary}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Friedman|first=Richard Elliott|title=Who Wrote the Bible?|publisher=HarperOne|year=1997}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Gaines|first=Jason M.H.|title=The Poetic Priestly Source|publisher=Fortress Press|year=2015|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pnHhCwAAQBAJ&q=%22documentary+hypothesis%22%22still+has+adherents%22&pg=PA271|isbn=978-1-5064-0046-4}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last1=Gertz|first1=Jan C.|last2=Levinson|first2=Bernard M.|last3=Rom-Shiloni|first3=Dalit|chapter=Convergence and Divergence in Pentateuchal Theory|editor1-last=Gertz|editor1-first=Jan C.|editor2-last=Levinson|editor2-first=Bernard M.|editor3-last=Rom-Shiloni|editor3-first=Dalit|title=The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America|publisher=Mohr Siebeck|year=2017|volume=44 |issue=4 |page=481 |chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/30485934}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Gmirkin|first=Russell|title=Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus|publisher=Bloomsbury|year=2006|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CKuoAwAAQBAJ&q=%22no+reference+to+a+written+torah%22&pg=PA32|isbn=978-0-567-13439-4}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Greifenhagen|first=Franz V.|title=Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map|publisher=Bloomsbury|year=2003|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r1evAwAAQBAJ&q=%22final+form+sometime+in+the+Persian+period%22&pg=PA207|isbn=978-0-567-39136-0}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Houston|first=Walter|title=The Pentateuch|publisher=SCM Press|year=2013|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IbALAQAAQBAJ&q=%22two+other+possibilities%22%22are+now+being+revived%22&pg=PA93|isbn=978-0-334-04385-0}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Kawashima|first=Robert S.|chapter=Sources and Redaction|editor1-last=Hendel|editor1-first=Ronald|title=Reading Genesis|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2010|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H4JvhWo04oEC&q=%22biblicists+generally+refer+to+these+sources+as%22&pg=PA52|isbn=978-1-139-49278-2}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Kratz|first=Reinhard G.|chapter=Rewriting Torah|editor1-last=Schipper|editor1-first=Bernd|editor2-last=Teeter|editor2-first=D. Andrew|title=Wisdom and Torah: The Reception of 'Torah' in the Wisdom Literature of the Second Temple Period|year=2013|publisher=BRILL|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nbDKAQAAQBAJ&q=%22+in+particular+in+the+documentary+and+fragmentary+hypothesis%22&pg=PA282|isbn=9789004257368}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Kratz|first=Reinhard G.|title=The Composition of the Narrative Books of the Old Testament|year=2005|publisher=A&C Black|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g0WnSW4Pc8oC|isbn=9780567089205}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Kugel|first=James L.|author-link=James L. Kugel|title=How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now|publisher=FreePress|year=2008|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=msdh9mmGHN4C|isbn=978-0-7432-3587-7}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Kurtz|first=Paul Michael|title=Kaiser, Christ, and Canaan: The Religion of Israel in Protestant Germany, 1871–1918|publisher=Mohr Siebeck|year=2018|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LmuKDwAAQBAJ|isbn=978-3-16-155496-4}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Levin|first=Christoph|title=Re-Reading the Scriptures|publisher=Mohr Siebeck|year=2013|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aSNZ76USaYgC&q=Levin+Re-Reading+the+SCriptures|isbn=978-3-16-152207-9}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=McDermott|first=John J.|title=Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction|publisher=Pauline Press|year=2002|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Dkr7rVd3hAQC&q=not+the+work+of+a+single+authorcomposed+over+several+centuries&pg=PA21|isbn=978-0-8091-4082-4}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=McEntire|first=Mark|title=Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch|publisher=Mercer University Press|year=2008|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VwOs9f1FpmsC&q=%22Josianic+Reform+of+the+late+seventh+century+BCE%22&pg=PA7|isbn=978-0-88146-101-5}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=McKim|first=Donald K.|title=Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms|year=1996|publisher=Westminster John Knox|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UJ9PYdzKf90C&q=dictionary+documentary+hypothesis&pg=PA81|isbn=978-0-664-25511-4}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last1=Miller|first1=Patrick D.|title=Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays|year=2000|publisher=A&C Black|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wKRiloF-00oC|isbn=978-1-84127-142-2}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Monroe|first=Lauren A.S.|title=Josiah's Reform and the Dynamics of Defilement|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2011|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bqpoAgAAQBAJ&q=%22date+of+Deuteronomy+into+the+exilic%22&pg=PA135|isbn=978-0-19-977536-1}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Moore|first1=Megan Bishop|last2=Kelle|first2=Brad E.|title=Biblical History and Israel's Past|year=2011|publisher=Eerdmans|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qjkz_8EMoaUC&pg=PA81|isbn=978-0-8028-6260-0}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Nicholson|first=Ernest Wilson|title=The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century|year=2003|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=opBBTHT13yoC|isbn=978-0-19-925783-6}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Otto|first=Eckart|chapter=The Study of Law and Ethics in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=%22This+change+of+research+paradigms%22&pg=PA609|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Patrick|first=Dale|title=Deuteronomy|year=2013|publisher=Chalice Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NkP4QlnlEmYC&q=%22De+Wette%27s+identification%22%22large+majority+of+critical+biblical+scholars%22&pg=PA69|isbn=978-0-8272-0566-6}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Patzia|first1=Arthur G.|last2=Petrotta|first2=Anthony J.|title=Pocket Dictionary of Biblical Studies|year=2010|publisher=InterVarsity Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=btEJAwAAQBAJ&q=dictionary+documentary+hypothesis&pg=PA37|isbn=978-0-8308-6702-8}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Empirical Models Challenging Biblical Criticism |last=Person |first=Raymond F. |publisher=SBL Press |year=2016 |isbn=978-0-88414-149-5 |editor-last=Person |editor-first=Raymond F. |chapter=The Problem of “Literary Unity” from the Perspective of the Study of Oral Traditions |editor-last2=Rezetko |editor-first2=Robert |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ViYiDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA217}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=How the Bible is Written |last=Rendsburg |first=Gary |publisher=Hendrickson Publishers |year=2019 |isbn=978-1-68307-197-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O7nFEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA468}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Ruddick|first=Eddie L.|chapter=Elohist|editor1-last=Mills|editor1-first=Watson E.|editor2-last=Bullard|editor2-first=Roger Aubrey|title=Mercer Dictionary of the Bible|publisher=Mercer University Press|year=1990|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=goq0VWw9rGIC&q=%22These+studies+later+guided+Eichhorn%22&pg=PA246|isbn=978-0-86554-373-7}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Ska|first=Jean-Louis|title=Introduction to reading the Pentateuch|year=2006|isbn=9781575061221|publisher=Eisenbrauns|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7cdy67ZvzdkC&pg=PA217}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Ska|first=Jean Louis|chapter=Questions of the 'History of Israel' in Recent Research|editor1-last=Saeboe|editor1-first=Magne|editor2-last=Ska|editor2-first=Jean Louis|editor3-last=Machinist|editor3-first=Peter|title=Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism|publisher=Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht|year=2014|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8fcxBgAAQBAJ&q=%22Persian+period+as+the+most+important%22&pg=PA430|isbn=978-3-525-54022-0}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Stackert|first=Jeffrey|title=A Prophet Like Moses: Prophecy, Law, and Israelite Religion|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2014|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DsCiAwAAQBAJ|isbn=978-0-19-933645-6}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Thompson|first=Thomas L.|title=Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources|year=2000|publisher=BRILL|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RwrrUuHFb6UC&q=long+folk+history+long+antedating&pg=PA8|isbn=9004119434}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Van Seters|first=John|title=The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary|year=2015|publisher=Bloomsbury T&T Clark|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=42-_CQAAQBAJ&q=%22new+supplementary+model%3A+van+seters%22&pg=PA55|isbn=978-0-567-65880-7}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Viviano|first=Pauline A.|chapter=Source Criticism|editor1-last=Haynes|editor1-first=Stephen R.|editor2-last=McKenzie|editor2-first=Steven L.|title=To Each Its Own Meaning: An Introduction to Biblical Criticisms and Their Application|year=1999|publisher=Westminster John Knox|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kpDceeylCjYC&q=Viviano+%22source+criticism%22&pg=PA35|isbn=978-0-664-25784-2}} | |||

| * {{cite book |first=Julius |last=Wellhausen |title=Geschichte Israels |date=1878 |volume=1 |location=Berlin |publisher=Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer |url=https://archive.org/details/geschichteisrae00wellgoog}} | |||

| * {{cite book |first=Julius |last=Wellhausen |title=Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels |date=1883 |volume=1 |edition=2nd |location=Berlin |publisher=Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer |url=https://archive.org/details/prolegomenazurg01wellgoog}} ; | |||

| * {{cite book |first=Julius |last=Wellhausen |title=Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte |date=1894 |volume=2 |location=Berlin |publisher=Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer |url=https://archive.org/details/israelitischeun00wellgoog}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Whisenant |first=Jessica |title=''The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance'' by Gary N. Knoppers, Bernard M. Levinson |journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society |volume=130 |issue=4 |year=2010 |pages=679–681 |jstor=23044597 }} | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Wright|first1=J. Edward|title=The Early History of Heaven|year=2002|publisher=Oxford University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lKvMeMorNBEC&q=Mesopotamian&pg=PA42|isbn=978-0-19-534849-1}} | |||

| {{Refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Wikiversity|Bible, English, King James, According to the documentary hypothesis}} | |||

| *{{Commons category-inline}} | |||

| *] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:19, 16 January 2025

Hypothesis to explain the origins and composition of the Torah

- J: Yahwist (10th–9th century BCE)

- E: Elohist (9th century BCE)

- Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- P*: Priestly (6th–5th century BCE)

- D†: Deuteronomist

- R: redactor

- DH: Deuteronomistic history (books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings)

The documentary hypothesis (DH) is one of the models used by biblical scholars to explain the origins and composition of the Torah (or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). A version of the documentary hypothesis, frequently identified with the German scholar Julius Wellhausen, was almost universally accepted for most of the 20th century. It posited that the Pentateuch is a compilation of four originally independent documents: the Jahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist, and Priestly sources, frequently referred to by their initials. The first of these, J, was dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE). E was dated somewhat later, in the 9th century BCE, and D was dated just before the reign of King Josiah, in the 7th or 8th century BCE. Finally, P was generally dated to the time of Ezra in the 5th century BCE. The sources would have been joined at various points in time by a series of editors or "redactors".

The consensus around the classical documentary hypothesis has now collapsed. This was triggered in large part by the influential publications of John Van Seters, Hans Heinrich Schmid, and Rolf Rendtorff in the mid-1970s, who argued that J was to be dated no earlier than the time of the Babylonian captivity (597–539 BCE), and rejected the existence of a substantial E source. They also called into question the nature and extent of the three other sources. Van Seters, Schmid, and Rendtorff shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in complete agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it. As a result, there has been a revival of interest in "fragmentary" and "supplementary" models, frequently in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another. Modern scholars also have given up the classical Wellhausian dating of the sources, and generally see the completed Torah as a product of the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (probably 450–350 BCE), although some would place its production as late as the Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE), after the conquests of Alexander the Great.

History of the documentary hypothesis

The Torah (or Pentateuch) is collectively the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. According to tradition, they were dictated by God to Moses, but when modern critical scholarship began to be applied to the Bible, it was discovered that the Pentateuch was not the unified text one would expect from a single author. As a result, the Mosaic authorship of the Torah had been largely rejected by leading scholars by the 17th century, with many modern scholars viewing it as a product of a long evolutionary process.

In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah. In 1780, Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and exegete Jean Astruc's "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the Jehovist ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the Elohist ("E"). These sources were subsequently found to run through the first four books of the Torah, and the number was later expanded to three when Wilhelm de Wette identified the Deuteronomist as an additional source found only in Deuteronomy ("D"). Later still the Elohist was split into Elohist and Priestly ("P") sources, increasing the number to four.

These documentary approaches were in competition with two other models, the fragmentary and the supplementary. The fragmentary hypothesis argued that fragments of varying lengths, rather than continuous documents, lay behind the Torah; this approach accounted for the Torah's diversity but could not account for its structural consistency, particularly regarding chronology. The supplementary hypothesis was better able to explain this unity: it maintained that the Torah was made up of a central core document, the Elohist, supplemented by fragments taken from many sources. The supplementary approach was dominant by the early 1860s, but it was challenged by an important book published by Hermann Hupfeld in 1853, who argued that the Pentateuch was made up of four documentary sources, the Priestly, Yahwist, and Elohist intertwined in Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers, and the stand-alone source of Deuteronomy. At around the same period, Karl Heinrich Graf argued that the Yahwist and Elohist were the earliest sources and the Priestly source the latest, while Wilhelm Vatke linked the four to an evolutionary framework: the Yahwist and Elohist to a time of primitive nature and fertility cults, the Deuteronomist to the ethical religion of the Hebrew prophets, and the Priestly source to a form of religion dominated by ritual, sacrifice and law.

Wellhausen and the new documentary hypothesis

In 1878, Julius Wellhausen published Geschichte Israels, Bd 1 ('History of Israel, Vol 1'). The second edition was printed as Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel") in 1883, and the work is better known under that name. (The second volume, a synthetic history titled Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte , did not appear until 1894 and remains untranslated.) Crucially, this historical portrait was based upon two earlier works of his technical analysis: "Die Composition des Hexateuchs" ('The Composition of the Hexateuch') of 1876–77, and sections on the "historical books" (Judges–Kings) in his 1878 edition of Friedrich Bleek's Einleitung in das Alte Testament ('Introduction to the Old Testament').

Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis owed little to Wellhausen himself but was mainly the work of Hupfeld, Eduard Eugène Reuss, Graf, and others, who in turn had built on earlier scholarship. He accepted Hupfeld's four sources and, in agreement with Graf, placed the Priestly work last. J was the earliest document, a product of the 10th century BCE and the court of Solomon; E was from the 9th century BCE in the northern Kingdom of Israel, and had been combined by a redactor (editor) with J to form a document JE; D, the third source, was a product of the 7th century BCE, by 620 BCE, during the reign of King Josiah; P (what Wellhausen first named "Q") was a product of the priest-and-temple dominated world of the 6th century BCE; and the final redaction, when P was combined with JED to produce the Torah as we now know it.

Wellhausen's explanation of the formation of the Torah was also an explanation of the religious history of Israel. The Yahwist and Elohist described a primitive, spontaneous, and personal world, in keeping with the earliest stage of Israel's history; in Deuteronomy, he saw the influence of the prophets and the development of an ethical outlook, which he felt represented the pinnacle of Jewish religion; and the Priestly source reflected the rigid, ritualistic world of the priest-dominated, post-exilic period. His work, notable for its detailed and wide-ranging scholarship and close argument, entrenched the "new documentary hypothesis" as the dominant explanation of Pentateuchal origins from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.

Critical reassessment

In the mid to late 20th century, new criticism of the documentary hypothesis formed. Three major publications of the 1970s caused scholars to reevaluate the assumptions of the documentary hypothesis: Abraham in History and Tradition by John Van Seters, Der sogenannte Jahwist ("The So-Called Yahwist") by Hans Heinrich Schmid, and Das überlieferungsgeschichtliche Problem des Pentateuch ("The Tradition-Historical Problem of the Pentateuch") by Rolf Rendtorff. These three authors shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.

Van Seters and Schmid both forcefully argued that the Yahwist source could not be dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE) as posited by the documentary hypothesis. They instead dated J to the period of the Babylonian captivity (597–539 BCE), or the late monarchic period at the earliest. Van Seters also sharply criticized the idea of a substantial Elohist source, arguing that E extends at most to two short passages in Genesis.

Some scholars, following Rendtorff, have come to espouse a fragmentary hypothesis, in which the Pentateuch is seen as a compilation of short, independent narratives, which were gradually brought together into larger units in two editorial phases: the Deuteronomic and the Priestly phases. By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.

Some scholars use these newer hypotheses in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another. The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses. Most scholars also agree that some form of Priestly source existed, although its extent, especially its end-point, is uncertain. The remainder is called collectively non-Priestly, a grouping which includes both pre-Priestly and post-Priestly material.

The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the Persian period (539–333 BCE). A minority of scholars would place its final compilation somewhat later, however, in the Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE).

A revised neo-documentary hypothesis still has adherents, especially in North America and Israel. This distinguishes sources by means of plot and continuity rather than stylistic and linguistic concerns, and does not tie them to stages in the evolution of Israel's religious history. Its resurrection of an E source is probably the element most often criticised by other scholars, as it is rarely distinguishable from the classical J source and European scholars have largely rejected it as fragmentary or non-existent.

The Torah and the history of Israel's religion

See also: History of ancient Israel and Judah and Origins of JudaismWellhausen used the sources of the Torah as evidence of changes in the history of Israelite religion as it moved (in his opinion) from free, simple and natural to fixed, formal and institutional. Modern scholars of Israel's religion have become much more circumspect in how they use the Old Testament, not least because many have concluded that the Hebrew Bible is not a reliable witness to the religion of ancient Israel and Judah, representing instead the beliefs of only a small segment of the ancient Israelite community centered in Jerusalem and devoted to the exclusive worship of the god Yahweh.

See also

- Authorship of the Bible

- Biblical criticism

- Books of the Bible

- Dating the Bible

- Mosaic authorship

- Umberto Cassuto, Jewish scholar who was critical of the documentary hypothesis

- Q Source, a similar theory for the construction of the Synoptic Gospels

Notes

- hence the alternative name JEDP for the documentary hypothesis

- The reasons behind the rejection are covered in more detail in the article on Mosaic authorship.

- The two-source hypothesis of Eichhorn was the "older" documentary hypothesis, and the four-source hypothesis adopted by Wellhausen was the "newer".

References

- ^ Viviano 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Gmirkin 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Viviano 1999, p. 41.

- Patzia & Petrotta 2010, p. 37.

- ^ Carr 2014, p. 434.

- Van Seters 2015, p. viii.

- ^ Van Seters 2015, p. 41.

- ^ Van Seters 2015, pp. 41–43.

- Carr 2014, p. 436.

- ^ Van Seters 2015, p. 12.

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207, 224 fn.49.

- McDermott 2002, p. 1.

- Kugel 2008, p. 6.

- Campbell & O'Brien 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Berlin 1994, p. 113.

- Baden 2012, p. 13.

- Ruddick 1990, p. 246.

- Patrick 2013, p. 31.

- ^ Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 19.

- Viviano 1999, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Viviano 1999, p. 38.

- Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 18–19.

- Friedman 1997, p. 24–25.

- Wellhausen 1878.

- Wellhausen 1883.

- Kugel 2008, p. 41.

- Wellhausen 1894.

- Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 20.

- Viviano 1999, p. 40–41.

- ^ Gaines 2015, p. 260.

- Viviano 1999, p. 51.

- Van Seters 2015, p. 42.

- Viviano 1999, p. 49.

- Thompson 2000, p. 8.

- Ska 2014, pp. 133–135.

- Van Seters 2015, p. 77.

- Otto 2014, p. 605.

- Carr 2014, p. 457.

- Otto 2014, p. 609.

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207.

- Whisenant 2010, p. 679, "Instead of a compilation of discrete sources collected and combined by a final redactor, the Pentateuch is seen as a sophisticated scribal composition in which diverse earlier traditions have been shaped into a coherent narrative presenting a creation-to-wilderness story of origins for the entity 'Israel.'"

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207, 224 n. 49.

- ^ Gaines 2015, p. 271.

- Gaines 2015, p. 272.

- Miller 2000, p. 182.

- Lupovitch, Howard N. (2010). "The world of the Hebrew Bible". Jews and Judaism in World History. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 5–10. ISBN 978-0-203-86197-4.

- Stackert 2014, p. 24.

- Wright 2002, p. 52.

Bibliography

- Baden, Joel S. (2012). The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis. Anchor Yale Reference Library. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15263-0.

- Barton, John (2014). "Biblical Scholarship on the European Continent, in the UK, and Ireland". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Barton, John; Muddiman, John (2010). The Pentateuch. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958024-8.

- Berlin, Adele (1994). Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-002-6.

- Berman, Joshua A. (2017). Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-065880-9.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2004). "Torah: Introduction". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-529751-5.

- Campbell, Antony F.; O'Brien, Mark A. (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-1367-0.

- Carr, David M. (2007). "Genesis". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-528880-3.

- Carr, David M. (2014). "Changes in Pentateuchal Criticism". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Frei, Peter (2001). "Persian Imperial Authorization: A Summary". In Watts, James (ed.). Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781589830158.

- Friedman, Richard Elliott (1997). Who Wrote the Bible?. HarperOne.

- Gaines, Jason M.H. (2015). The Poetic Priestly Source. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-5064-0046-4.

- Gertz, Jan C.; Levinson, Bernard M.; Rom-Shiloni, Dalit (2017). "Convergence and Divergence in Pentateuchal Theory". In Gertz, Jan C.; Levinson, Bernard M.; Rom-Shiloni, Dalit (eds.). The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America. Vol. 44. Mohr Siebeck. p. 481.

- Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Greifenhagen, Franz V. (2003). Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-39136-0.

- Houston, Walter (2013). The Pentateuch. SCM Press. ISBN 978-0-334-04385-0.

- Kawashima, Robert S. (2010). "Sources and Redaction". In Hendel, Ronald (ed.). Reading Genesis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49278-2.

- Kratz, Reinhard G. (2013). "Rewriting Torah". In Schipper, Bernd; Teeter, D. Andrew (eds.). Wisdom and Torah: The Reception of 'Torah' in the Wisdom Literature of the Second Temple Period. BRILL. ISBN 9789004257368.

- Kratz, Reinhard G. (2005). The Composition of the Narrative Books of the Old Testament. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567089205.

- Kugel, James L. (2008). How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now. FreePress. ISBN 978-0-7432-3587-7.

- Kurtz, Paul Michael (2018). Kaiser, Christ, and Canaan: The Religion of Israel in Protestant Germany, 1871–1918. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-155496-4.

- Levin, Christoph (2013). Re-Reading the Scriptures. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-152207-9.

- McDermott, John J. (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction. Pauline Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4082-4.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-88146-101-5.

- McKim, Donald K. (1996). Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-25511-4.

- Miller, Patrick D. (2000). Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-142-2.

- Monroe, Lauren A.S. (2011). Josiah's Reform and the Dynamics of Defilement. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977536-1.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.

- Nicholson, Ernest Wilson (2003). The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925783-6.

- Otto, Eckart (2014). "The Study of Law and Ethics in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Patrick, Dale (2013). Deuteronomy. Chalice Press. ISBN 978-0-8272-0566-6.

- Patzia, Arthur G.; Petrotta, Anthony J. (2010). Pocket Dictionary of Biblical Studies. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-6702-8.

- Person, Raymond F. (2016). "The Problem of "Literary Unity" from the Perspective of the Study of Oral Traditions". In Person, Raymond F.; Rezetko, Robert (eds.). Empirical Models Challenging Biblical Criticism. SBL Press. ISBN 978-0-88414-149-5.

- Rendsburg, Gary (2019). How the Bible is Written. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 978-1-68307-197-6.

- Ruddick, Eddie L. (1990). "Elohist". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Ska, Jean Louis (2014). "Questions of the 'History of Israel' in Recent Research". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Stackert, Jeffrey (2014). A Prophet Like Moses: Prophecy, Law, and Israelite Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933645-6.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2000). Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources. BRILL. ISBN 9004119434.

- Van Seters, John (2015). The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary. Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-65880-7.

- Viviano, Pauline A. (1999). "Source Criticism". In Haynes, Stephen R.; McKenzie, Steven L. (eds.). To Each Its Own Meaning: An Introduction to Biblical Criticisms and Their Application. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-25784-2.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1878). Geschichte Israels. Vol. 1. Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1883). Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer. Project Gutenberg edition; full text at sacred-texts.com

- Wellhausen, Julius (1894). Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte. Vol. 2. Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer.

- Whisenant, Jessica (2010). "The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance by Gary N. Knoppers, Bernard M. Levinson". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 130 (4): 679–681. JSTOR 23044597.

- Wright, J. Edward (2002). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534849-1.

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Documentary hypothesis at Wikimedia Commons

- Wikiversity – The King James Version according to the documentary hypothesis