| Revision as of 20:31, 23 May 2008 editYaf (talk | contribs)12,537 editsm →Military service: moving to the appropriate section (Let U&M have their say in previous paragraph and move scholarly disagreement to its own paragraph)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:16, 26 December 2024 edit undoRobotGoggles (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,605 editsNo edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Right of citizens to possess weapons}} | |||

| {{POV|date=May 2008}} | |||

| {{redirect2|Bear arms|Right to bear arms|other uses|Bear arms (disambiguation)}}{{Redirect|Pro gun|the firearms advocacy group in the Philippines|PROGUN}}{{Lead too short|date=May 2022}} | |||

| The '''right to arms''' (or 'right to keep and bear arms', ], 'right to bear arms,' and similar expressions) is the concept that people, individually or collectively, have a right to weapons. Today this is usually interpreted to mean ]. This is a popular concept in the ], where the right is expressed in the ], drafted in ]. The right derived from popular conceptions of ] around the American Revolution, including a ] right to possess weapons, the ] (1689) and a statute, the ], dating back to ]. | |||

| {{Rights}} | |||

| ] scenarios with live ammunition at a video shooting range in Prague, Czech Republic in 2018]] | |||

| The '''right to keep and bear arms''' (often referred to as the '''right to bear arms''') is a legal right for people to possess ]s (arms) for the preservation of life, liberty, and property.<ref name=Halbrook1994p8>{{cite book |last=Halbrook |first=Stephen P. |year=1994 |title=That Every Man Be Armed: The Evolution of a Constitutional Right (Independent Studies in Political Economy) |url=https://archive.org/details/thateverymanbear0000halb/page/8 |page= |publisher=] |location=Oakland, CA |isbn=0945999380 |oclc=30659789 }}</ref> The purpose of gun rights is for ], as well as ] and ].<ref name="Levan">{{cite book |last=Levan |first=Kristine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h4aWFrgW74YC |title=Crime Prevention |publisher=Jones & Bartlett |year=2013 |isbn=978-1449615932 |editor1-last=Mackey |editor1-first=David A. |page=438 |chapter=4 Guns and Crime: Crime Facilitation Versus Crime Prevention |quote=They promote the use of firearms for self-defense, hunting, and sporting activities, and also promote firearm safety. |editor2-last=Levan |editor2-first=Kristine |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h4aWFrgW74YC&pg=PA93}}</ref>{{rp|96}}<ref name="Larry Pratt">{{cite web |author=Larry Pratt |title=Firearms: the People's Liberty Teeth |url=http://gunowners.org/fs9402.htm |access-date=December 30, 2008}}</ref> Countries that guarantee a right to keep and bear arms include ], ], ], ], the ], ], ], the ] and ]. | |||

| In the United States, the right to keep and bear arms is often presented in the context of military service and the broader right of ]. Whether this right pertains to individuals acting independently or individuals acting collectively is a matter of debate, and the basis for any right at all is hotly contested. | |||

| == |

==Background== | ||

| The ] allowed ] citizens of ] to "have Arms for their Defense suitable to their Conditions and as allowed by Law." This restricted the ability of the ] to have a ] or to interfere with Protestants' right to bear arms "when Papists were both Armed and Imployed contrary to Law" and established that Parliament, not the Crown, could regulate the right to bear arms.<ref name="c21WillMarSess2">{{cite web |url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/aep/WillandMarSess2/1/2/introduction |title=1688 c.2 1 Will. and Mar. Sess. 2 |publisher=The National Archives (UK) |access-date=July 2, 2014}}</ref><ref name=BBCBoR>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/dna/place-lancashire/plain/A727265 |title=BBC: Bill of Rights Act, 1689 – The Glorious Revolution |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |year=2002 |website=bbc.co.uk |publisher=BBC |access-date=July 2, 2014 |archive-date=July 14, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140714182517/http://news.bbc.co.uk/dna/place-lancashire/plain/A727265 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ===Military service=== | |||

| Some historians have found that prior to and through the Eighteenth century, usage of the expression "bear arms" appeared exclusively in military contexts, as opposed to the use of firearms by ]s.<ref name = "UM194">Uviller, H. Richard. & Merkel, William G.: ''The Militia and the Right to Arms, Or, How the Second Amendment Fell Silent '', pp 23, 194. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3017-2</ref><ref>Pepper, John; Petrie, Carol; Wellford, Charles F.: ''Firearms and violence'', Page 290. National Academies Press, 2004. ISBN 0309091241</ref><ref>]. ''To Keep and Bear Arms''. New York Review Of Books, Sept. 21, 1995.</ref><ref name="isbn0-300-09562-7">{{cite book| author=Williams, David H.|title=The mythic meanings of the Second Amendment: taming political violence in a constitutional republic| publisher=Yale University Press|location=New Haven, Conn|year=2003|pages=Pg 5|quote=The amendment thus guarantees a right to arms only within the context of a militia, not an individual right to arms for self-defense or hunting.|isbn=0-300-09562-7|oclc=|doi=}}</ref> | |||

| Sir ] wrote in the 18th century that the right to have arms was auxiliary to the "natural right of resistance and self-preservation" subject to suitability and allowance by law.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/blackstone_bk1ch1.asp |title=Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England |publisher=Avalon.law.yale.edu |access-date=2012-05-22}}</ref> The term ''arms'', as used in the 1600s, refers to the process of equipping for war;<ref>{{cite web|last1=Harper|first1=Douglas|title=arm (n.)|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=arm&allowed_in_frame=0|website=Online Etymology Dictionary|publisher=Douglas Harper|access-date=12 March 2015}}</ref> it is commonly used as a synonym for weapon.<ref>{{cite web|title=Arm|url=http://www.thefreedictionary.com/arm|website=Thefreedictionary.com|access-date=12 March 2015}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>"In late-eighteenth-century parlance, ''bearing arms'' was a term of art with an obvious military and legal connotation. ... As a review of the Library of Congress's data base of congressional proceedings in the revolutionary and early national periods reveals, the thirty uses of 'bear arms' and 'bearing arms' in bills, statutes, and debates of the Continental, Confederation, and United States' Congresses between 1774 and 1821 invariably occur in a context exclusively focused on the army or the militia."<ref name = "UM194">Uviller, H. Richard. & Merkel, William G.: ''The Militia and the Right to Arms, Or, How the Second Amendment Fell Silent '', Page 194. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3017-2</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Inclusion of this right in a written constitution is uncommon. In 1875, 17 percent of national constitutions included a right to bear arms. Since the early twentieth century, "the proportion has been less than 9 percent and falling".<ref name=Ginsburg>{{cite news |last1=Ginsburg |first1=Tom |last2=Elkins |first2=Zachary |last3=Melton |first3=James |title=U.S. Gun Rights Are Truly American Exceptionalism |work=Bloomberg |date=7 March 2013 |access-date=25 March 2016 |url=http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2013-03-07/u-s-gun-rights-truly-are-american-exceptionalism}}</ref> In an article titled "U.S. Gun Rights Truly Are ]," a historical survey and comparative analysis of constitutions dating back to 1789,<ref name=Ginsburg/> ] and colleagues "identified only 15 constitutions (in nine countries) that had ever included an explicit right to bear arms. Almost all of these constitutions have been in Latin America, and most were from the 19th century".<ref name=Elkins>{{cite news |author=Elkins, Zachary |title=Rewrite the Second Amendment |work=New York Times |date=4 April 2013 |access-date=29 March 2016 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/05/opinion/rewrite-the-second-amendment.html?_r=0}}</ref> | |||

| However, this unilateral conclusion is disputed and may be due to ] through the use of government documents, which overwhelmingly refer to matters of military service.<ref name="Cramer-Olson001">{{cite journal|author= Cramer, Clayton E.; Olson, Joseph|title= What Did "Bear Arms" Mean in the Second Amendment?|journal= Georgetown Journal of Law & Public Policy|volume= 6|issue= 2|year=2008}}</ref> Subsequently, other historians note: <blockquote>"Searching more comprehensive collections of English language works published before 1820 shows that there are a number of uses that...have nothing to do with military service... The common law was in agreement. Edward Christian’s edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries that appeared in the 1790’s described the rights of Englishmen (which every American colonist had been promised) in these terms 'everyone is at liberty to keep or carry a gun, if he does not use it for the destruction of game.' This right was separate from militia duties."<ref name="Cramer-Olson001"/></blockquote> | |||

| ==Countries recognizing the right to keep and bear arms== | |||

| The ] defines the term ''to bear arms'' as: ''"to serve as a soldier, do military service, fight,"'' dating to about the year 1330. And, defines the term ''to bear arms against'' as: ''"to be engaged in hostilities with."'' dating the usage back to about the year 1000 with the epic poem '']''.<ref>Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition, 1989</ref> | |||

| ===North America=== | |||

| ====Guatemala==== | |||

| {{quote box|align=right|quote= | |||

| ], author and history professor at ], has written of the origin of the term ''bear arms'': | |||

| The right to own weapons for personal use, not prohibited by the law, in the place of inhabitation, is recognized. There will not be an obligation to hand them over, except in cases ordered by a competent judge.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.businessinsider.com/2nd-amendment-countries-constitutional-right-bear-arms-2017-10|title=Only 3 countries in the world protect the right to bear arms in their constitutions: the US, Mexico, and Guatemala|first=Brennan Weiss, James|last=Pasley|website=Business Insider}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>"By legal and other channels, the Latin "''] ]''" entered deeply into the European language of war. Bearing arms is such a synonym for waging war that Shakespeare can call a just war "'' 'justborne arms''" and a civil war "''self-borne arms''." Even outside the special phrase "''bear arms''," much of the noun's use echoes Latin phrases: to be under arms (''] armis''), the call to arms (''] arma''), to follow arms (''arma ]''), to take arms (''arma ]''), to lay down arms (''arma pœnere''). "Arms" is a profession that one brother chooses the way another choose law or the church. An issue undergoes the arbitrament of arms." ... "One does not bear arms against a rabbit...".<ref name = "UM194"/></blockquote> | |||

| |source=Article 38 of Guatemala Constitution | |||

| |width=40%}} {{see also|Gun law in Guatemala}} | |||

| While protecting the right to keep arms, Guatemalan constitution specifies that this right extends only to "weapons not prohibited by law". | |||

| On the other hand, ] notes non-military usage of the phrase in the Pennsylvania ratifying convention:<blockquote>"he people have a right to bear arms for...the purpose of killing game; and no law shall be passed for disarming the people or any of them, unless for crimes committed."<ref name="Sayoko001">{{cite journal|author= Blodgett-Ford, Sayoko|title= The Changing Meaning of the Right to Bear Arms|journal= Seton Hall Constitutional Law Journal|date= Fall 1995 | |||

| |pages= 101}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ====Honduras==== | |||

| ], a professor of constitutional and criminal law, and a criminologist, has written in the ''Michigan Law Review'' that the Second Amendment clearly refers to personal weapons, since "bear" means "carry," and a person cannot carry certain military weapons, like artillery. According to Garry Wills, <blockquote>"this gets things exactly backwards, as "Bear Arms" refers to military service, which is why the plural is used (based on Greek 'hopla pherein' and Latin 'arma ferre') -- one does not bear arm, or bear an arm. The word means, etymologically, 'equipment' (from the root ar-* in verbs like 'ararisko', to fit out). It refers to the 'equipage' of war. Thus 'bear arms' can be used of naval as well as artillery warfare, since the "profession of arms" refers to all military callings."<ref>Wills, Garry (1999). ''A Necessary Evil'' pages 256–257. New York, NY. Simon & Schuster.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| {{quote box|align=right|quote= | |||

| Every person, in the exercise of their civil rights, may request a maximum of five (5) license for the possession and carrying of up to five (5) firearms by submitting an application with the following information<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/citation/quotes/9262|title=Licences to Possess and Carry Firearms (Licencias para la Tenencia y Portación de Armas de Fuego) |website=www.gunpolicy.org}}</ref> {{hidden|(...)| (1) Form with personal information and residence; (2) Brand, model, serial number, identification of modification of calibre, if any; as well as any other characteristics of the weapon; (3) Proof of having undertaken a ballistic test; (4) Payment of municipal matriculation and criminal background check; and, (5) Identification documents.}} | |||

| |source=Article 27 of Decree No. 69-2007, Modifying the Act on the Control of Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives and Other Related Materials (Honduras) | |||

| |width=40%}} The constitution of ] does not protect the right to keep and bear arms. | |||

| Although not explicitly mentioned in the legislation, every person is entitled to receive a license to keep and carry arms by Honduran Statute law, provided that they fulfill the conditions required by the law.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/region/honduras|title=Guns in Honduras – Firearms, gun law and gun control|website=www.gunpolicy.org|access-date=2019-08-23}}</ref> | |||

| ===Civilian usage definition=== | |||

| The people's right to have their own arms for their defense is described in the philosophical and political writings of Aristotle, Cicero, John Locke, Machiavelli, the English Whigs, and others.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book |author=Halbrook, Stephen P.|title=That Every Man Be Armed: The Evolution of a Constitutional Right (Independent Studies in Political Economy)|publisher=The Independent Institute|location=Oakland, CA|year=1994|pages=8|isbn=0-945999-38-0}}</ref> Though possessing arms appears to be distinct from "bearing" them, the possession of arms is recognized as necessary for and a logical precursor to the bearing of arms.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal|author=Schmidt, Christopher|title=An International Human Right to Keep and Bear Arms|date=February 2007|publisher=The College of William & Mary School of Law|location=Williamsburg, Virginia|volume=15|issue=3|pages=983}}</ref> Particularly in the event of oppression or slaughter of people by governments or racial majorities, researchers have noted that exercise of the right to bear arms internationally is intrinsically linked to a people's ability to possess them.<ref name="Kopel-Eisen-Gallant001"> | |||

| {{cite journal|journal= The Brown Journal of World Affairs|author= Kopel, David B.; Eisen, Joanne D.; Gallant, Paul|title= Guns Ownership and Human Rights|date= 2003|volume= 9|issue= 2|pages= 1-13|quote= And Bougainville is a reminder that sometimes neither the UN, developed democracies such as Australia, nor the "international community" will defend a people against rapine. The only protectors of the birthright of the people of Bougainville were the people themselves, bearing their "illicit" firearms.}}</ref> | |||

| ====Mexico==== | |||

| In commentary written by Justice Cummings in '']'', the ] concluded in 2001 that:<ref name="isbn0-8223-3017-2">{{cite book | |||

| {{quote box|align=right|quote= | |||

| |author=Merkel, William G.; Uviller, H. Richard | |||

| The inhabitants of the United Mexican States have the right to possess arms within their domicile, for their safety and legitimate defense, except those forbidden by Federal Law and those reserved for the exclusive use of the Army, Militia, Air Force and National Guard. Federal law shall provide in what cases, conditions, under what requirements and in which places inhabitants shall be authorized to bear arms.<ref name="auto">{{cite web | |||

| |title=The militia and the right to arms, or, How the second amendment fell silent | |||

| | url= http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Constitucion/articulos/10.pdf | |||

| |publisher=Duke University Press | |||

| | title= Mexican Constitution (As amended) | |||

| |location=Durham, N.C | |||

| |pages= Article 10}}</ref> | |||

| |year=2002 | |||

| |source=Article 10 of ] | |||

| |pages=Pg 19, Chapter 9 (pages 212-225) | |||

| |width=40%}} {{See also|Gun politics in Mexico}} | |||

| |isbn=0-8223-3017-2 | |||

| }}</ref> <blockquote>"there are numerous instances of the phrase 'bear arms' being used to describe a civilian's carrying of arms. Early constitutional provisions or declarations of rights in at least some ten different states speak of the right of the 'people' "to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state,' or equivalent words, thus indisputably reflecting that under common usage 'bear arms' was in no sense restricted to bearing arms in military service."<ref></ref></blockquote> | |||

| The Mexican constitution of 1857 first included the right to be armed. In its first version, the right was defined in similar terms as it is in the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution. A new Mexican ] revised the right, stating that its utilization must be in line with local police regulations. | |||

| The bearing of arms by civilians in this sense is exercised in Israel to prevent terrorist attacks on grade schools.<ref> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| |url= http://www.nationalreview.com/kopel/kopel200409022215.asp | |||

| |title= Follow the Leader: Israel and Thailand set an example by arming teachers. | |||

| |date= 2004-09-02 | |||

| |accessdate= 2008-05-17 | |||

| |quote= Teachers and kindergarten nurses now started to carry guns, schools were protected by parents (and often grandpas) guarding them in voluntary shifts. No school group went on a hike or trip without armed guards. The Police involved the citizens in a voluntary civil guard project “Mishmar Esrachi,” which even had its own sniper teams. The Army’s Youth Group program, “Gadna”, trained 15 to 16-year-old kids in gun safety and guard procedures and the older high-school boys got involved with the Mishmar Esrachi. During one noted incident, the “Herzliyah Bus massacre” (March ’78, hijacking of a bus, 37 dead, 76 wounded), these youngsters were involved in the overall security measures in which the whole area between North Tel Aviv and the resort town of Herzlyiah was blocked off, manning roadblocks with the police, guarding schools kindergartens, etc. | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Another change was included in 1917 Constitution. Since then, Mexicans have the right to be armed only within their home and further utilization of this right is subject to ]. | |||

| Similarly, in a released Senate report on the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, Senator ], chairman, U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on the Constitution, states: {{quote|They argue that the Second Amendment's words "right of the people" mean "a right of the state" — apparently overlooking the impact of those same words when used in the First and Fourth Amendments. The "right of the people" to assemble or to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures is not contested as an individual guarantee. Still they ignore consistency and claim that the right to "bear arms" relates only to military uses. This not only violates a consistent constitutional reading of "right of the people" but also ignores that the second amendment protects a right to "keep" arms. "When our ancestors forged a land "conceived in liberty", they did so with musket and rifle. When they reacted to attempts to dissolve their free institutions, and established their identity as a free nation, they did so as a nation of armed freemen. When they sought to record forever a guarantee of their rights, they devoted one full amendment out of ten to nothing but the protection of their right to keep and bear arms against governmental interference. Under my chairmanship the Subcommittee on the Constitution will concern itself with a proper recognition of, and respect for, this right most valued by free men."<ref name="rkba1982">Right to Keep and Bear Arms, U.S. Senate. 2001 Paladin Press. ISBN 1581602545.</ref>}} | |||

| ====United States==== | |||

| Likewise, relative to '']'', No. 07-290, a case pending before the ], the earlier 2007 DC Circuit Court opinion dismissed the lawsuit in a 2-1 decision, summarizing its substantive ruling on the right protected by the Second Amendment on page 46 of the slip opinion (at the end of section III) as:<ref> {{cite web | url=http://pacer.cadc.uscourts.gov/docs/common/opinions/200703/04-7041a.pdf |title= Text of the decision] (slip opinion)}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote box | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | quote = A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.<ref>{{Cite web|title=U.S. Senate: Constitution of the United States|url=https://www.cop.senate.gov/civics/constitution_item/constitution.htm#amdt_2_(1791)|access-date=2021-12-30|website=www.cop.senate.gov}}</ref> | |||

| | source = ] | |||

| | width = 40% | |||

| }} {{Main|Right to keep and bear arms in the United States}} | |||

| {{further|Second Amendment to the United States Constitution}} | |||

| In the ], which has an English ] tradition, a longstanding common-law right to keep and bear arms was practiced prior to the creation of a written national constitution.<ref name=McAffeeQuinlan>{{cite journal |last1=McAffee |first1=Thomas B. |last2=Quinlan |first2=Michael J. |year=1997 |title=Bringing Forward The Right To Keep And Bear Arms: Do Text, History, or Precedent Stand In The Way? |url=http://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/512/ |journal=Scholarly Works |volume=Paper 512 |issue= |pages= }}</ref> Today, this right is specifically protected by the ] and many ].<ref name=Volokh2008>{{cite web |url=http://www2.law.ucla.edu/volokh/beararms/statecon.htm |title=State Constitutional Right to Keep and Bear Arms Provisions |last=Volokh |first=Eugene |date=2008 |website=law.ucla.edu |publisher= |accessdate= }}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|To summarize, we conclude that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to keep and bear arms. That right existed prior to the formation of the new government under the Constitution and was premised on the private use of arms for activities such as hunting and self-defense, the latter being understood as resistance to either private lawlessness or the depredations of a tyrannical government (or a threat from abroad). In addition, the right to keep and bear arms had the important and salutary civic purpose of helping to preserve the citizen militia. The civic purpose was also a political expedient for the Federalists in the First Congress as it served, in part, to placate their Antifederalist opponents. The individual right facilitated militia service by ensuring that citizens would not be barred from keeping the arms they would need when called forth for militia duty. Despite the importance of the Second Amendment's civic purpose, however, the activities it protects are not limited to militia service, nor is an individual's enjoyment of the right contingent upon his or her continued or intermittent enrollment in the militia.}} | |||

| ===Europe=== | |||

| == Historical sources, protections, and extinguishments of the right== | |||

| The right to keep and bear arms varies by country (see ]) and at times varies by ] within a ]. | |||

| ====Czech Republic==== | |||

| === Jurisdictions with English judicial origin === | |||

| {{main|English law}} | |||

| Frequently cited sources: | |||

| *] | |||

| *], 1689<ref name='englishbillorights'> {{cite web|url=http://www.duhaime.org/LegalResources/LawMuseum/tabid/345/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/110/1689-The-English-Bill-of-Rights.aspx |title=1689: The English Bill of Rights |accessdate=2008-05-10 |last=Duhaime |first=Lloyd |date=2007-05-07 }}</ref> | |||

| {{quote box|align=right|quote= | |||

| The responsibility to keep and bear arms in jurisdictions operating under ] follows a precedent that predates the invention of ], originating contemporaneously with the ] and the emergence of the ] system, during the reign of ], who promulgated the ] in ], which required ]s and freemen to keep arms and to bear them in service of the ].<ref>Taylor, H. (1908). . ''The science of jurisprudence: a treatise in which the growth of positive law is unfolded by the historical method, and its elements classified and defined by the analytical.'' New York: Macmillan.</ref> A Common Law right to have arms for self defense was codified in the English Bill of Rights of 1689 (also known as the English Declaration of Rights), at least for ]s. England, Ireland, the Colonies in North America (which became the United States), Canada, and Australia all received this Common Law inheritance and long maintained a responsibility to keep and bear arms tradition originating from this common basis. | |||

| The right to acquire, keep and bear firearms is guaranteed under conditions set by this law. | |||

| |source=Article 1 Subsection 1 of ] | |||

| |width=40%}} | |||

| {{quote box|align=right|quote= | |||

| (1) Everyone has the right to life. Human life is worthy of protection even before birth. <br />(2) Nobody may be deprived of their life. <br />(3) The death penalty is prohibited. <br />(4) Deprivation of life is not inflicted in contravention of this Article if it occurs in connection with conduct which is not criminal under the law. '''The right to defend own life or life of another person also with arms is guaranteed under conditions set out in the law'''.<ref name="Con am3">{{Citation | |||

| | last = 35 Members of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic | |||

| | year = 2019 | |||

| | title = Proposal of amendment of Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms | |||

| | location = Prague | |||

| | url = https://www.senat.cz/xqw/webdav/pssenat/original/92773/77778 | |||

| | access-date = 29 September 2017 | |||

| | language = cs | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| |source=Constitutional amendment of Czech ] passed in 2021. Most of the Article is preexisting, the last sentence in subsection 4 was newly added. | |||

| |width=40%}} {{Main|Gun laws in the Czech Republic}} {{further|History of Czech civilian firearms possession}} | |||

| Historically, the ] were at the forefront of the spreading of civilian firearms ownership.<ref name="zrizeni" /> In the 1420s and 1430s, firearms became indispensable tools for the mostly peasant ] whose amateur combatants, including women, fended off a series of invasions of professional crusader armies of well-armored warriors with cold weapons.<ref name="zrizeni" /> Throughout and after the Hussite wars, firearms' design underwent fast development and their possession by civilians became a matter of course.<ref name="zrizeni" /> | |||

| The English ] set out the right of Protestants to have arms suitable for their own defense as allowed by law.<ref name="brookhiser">{{cite book | last = Brookhiser | first = Richard | title = What Would the Founders Do? | edition = Paperback edition | origyear = 2006 | year = 2007 | publisher = Basic Books | location = New York, NY | pages = 35 | isbn = 978-0-465-00820-9 }}</ref> This was because of the fear the Protestants had in England of being disarmed that led to the ] and subsequently their guaranteed right to self-defense. | |||

| Their first firearms regulation was enacted in 1517 as a part of general accord between the nobles and ]s and later in 1524 as a standalone Enactment on Firearms (''zřízení o ručnicích''). The 1517 law explicitly stated that "all people of all standing have the right to keep firearms at home" while at the same time enacting a universal carry ban.<ref name="zrizeni" /> The 1524 enactment set out a process of issuing of permits for carrying of firearms and detailed enforcement and punishment for carrying without such a permit.<ref name="zrizeni">{{cite web | |||

| ] wrote in the eighteenth century about the right to have arms being a "natural right of resistance and self-preservation", espousing the individual right to protect oneself.<ref name="brookhiser"/> | |||

| | last = Gawron | |||

| | first = Tomáš | |||

| | title = Historie civilního držení zbraní: Zřízení o ručnicích – česká zbraňová legislativa v roce 1524 | |||

| | work = zbrojnice.com | |||

| | date = November 2019 | |||

| | url = https://zbrojnice.com/2019/11/01/historie-civilniho-drzeni-zbrani-zrizeni-o-rucnicich-ceska-zbranova-legislativa-v-roce-1524/ | |||

| | access-date = 1 November 2019 | |||

| | language = cs}} | |||

| </ref> Carrying later became permitless again until 1852, when Imperial Regulation No. 223 reintroduced carry permits. This law remained in force until the ].<ref name="zrizeni" /> | |||

| Since its inception during the Hussite revolution, the right to keep firearms endured over five-hundred years until the Nazi gun ban during the ] in the 20th century. Firearms possession later became severely restricted during the ]. After the ], the Czech Republic instated a shall-issue permitting process, under which all residents can keep and bear arms subject to the fulfillment of regulatory conditions.<ref name="zrizeni" /> | |||

| In modern usage, "arms" is often considered synonymous with "firearms". Historically, however, "arms" has referred to a variety of weapons and armor.<ref> ] ''To Keep and Bear Arms''. New York Review Of Books, Sept. 21, 1995.</ref> In the United States, the term has been used to refer to edged weapons such as the ] and ].<ref>David B. Kopel, Clayton E. Cramer, Scott G. Hattrup, ''A Tale of Three Cities: The Right to Bear Arms in State Supreme Courts'' Temple Law Review.</ref> | |||

| In the Czech Republic, every resident that meets conditions laid down in Act No. 119/2002 Coll.<ref name="Firearms Act">{{Citation | |||

| Over the last 80 years, in all the countries that derive their laws from English Common Law except the United States, ] has permitted ] to be developed that extinguishes the historical common law right to have arms for self defense. Similarly, in the United States, the courts have widely allowed local jurisdictions in some states (e.g., New York, Illinois, California, New Jersey) to license and regulate historical common law rights to have arms for self defense. | |||

| | last = Parliament of the Czech Republic | |||

| | year = 2002 | |||

| | title = Act No. 119/2002 Coll., on Firearms and Ammunition | |||

| | location = Prague | |||

| | url = http://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2002-119 | |||

| | language = cs | |||

| }}</ref> has the right to have a firearms license issued and can then obtain a firearm.<ref name="Firearms Act-p8">''Firearms Act, Section 8''</ref><ref name="Firearms Act-p16(1)">''Firearms Act, Section 16(1)''</ref> Holders of ''D'' (exercise of profession) and ''E'' (self-defense) licenses, which are also ], can carry up to two concealed firearms for protection.<ref name="Firearms Act-p28(3)(B), 28(4)(C)">''Firearms Act, Section 28(3)(B), 28(4)(C)''</ref> The right to be armed is statutorily protected. | |||

| A proposal to have the right to keep and bear arms included in the constitution was entered in the Czech Parliament in December 2016.<ref name="Con am">{{Citation | |||

| ====United Kingdom==== | |||

| | last = Ministry of Interior | |||

| {{see|English law|Scots Law|Northern Ireland law}} | |||

| | year = 2016 | |||

| Although a right to have and use arms once existed in ] and ], this is no longer the case and has not been so for many decades. Some argue that a general right to keep or bear arms has not existed for centuries. In any case, the modern legal situation is that the possession of firearms is effectively a privilege granted only to persons who can demonstrate both a need and that they are sufficiently responsible. | |||

| | title = Proposal of amendment of constitutional act no. 110/1998 Col., on Security of the Czech Republic | |||

| | location = Prague | |||

| The ] of 1689 included the provision that "the subjects which are Protestants may have Arms for their Defence suitable to their Conditions, and as allowed by Law."<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://apps.odok.cz/veklep-detail?pid=KORNAGNGZSFW | |||

| | url = http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=12995#s11 | |||

| | access-date = 16 December 2016 | |||

| | title = House of Lords Journal Volume 14 | |||

| | language = cs | |||

| | date = 12 February 1689 | |||

| }}</ref> The proposal was approved by vote of 139 to 9 on 28 June 2017 by the Chamber of Deputies. It later failed to reach necessary support in Senate, where only 28 out of 59 Senators present supported it (with constitutional majority being 36 votes).<ref>{{Citation | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-03-07 | |||

| | year = 2017 | |||

| }}</ref> The words "as allowed by Law" indicate in England this is considered a qualified rather than an absolute right. However this provision, along with many other pieces of ancient law, has been overruled by the doctrine of ], the Bill of Rights had no special legal protection as a result of ]. | |||

| | title = Právo nosit zbraň pro zajištění bezpečnosti Česka Senát neschválil | |||

| | url = https://zpravy.idnes.cz/zbrane-senat-pravo-bezpecnost-statu-ustava-novela-fw8-/domaci.aspx?c=A171206_215545_domaci_lre | |||

| The ] enacted almost identical provisions to the Bill of Rights in Scotland prior to the creation of the ] and contained the provision that "the disarming of Protestants... contrary to law". | |||

| | access-date = 6 December 2017 | |||

| | language = cs | |||

| The English Bill of Rights should not be equated to the ]. In the United Kingdom, ] is the ultimate authority and legislation is not constrained by a central ] constitution like that of the United States. More recent statements of rights, such as the UK ] have contained no mention of a right to bear arms, and whilst the law of the ] makes certain provisions relating to gun ownership, they are focused on the harmonisation of national laws for trade purposes.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| | url = http://eur-lex.europa.eu/smartapi/cgi/sga_doc?smartapi!celexapi!prod!CELEXnumdoc&lg=EN&numdoc=31991L0477&model=guichett | |||

| | title = Council Directive 91/477/EEC of 18 June 1991 on control of the acquisition and possession of weapons | |||

| |accessdate = 2007-03-07}}</ref> | |||

| ]s, ]s, ]s and ] were first controlled by the ], which made it illegal to possess these weapons without first obtaining a certificate from the police. Similar provisions were introduced for shotguns in 1967.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.parliament.uk/post/pn087.pdf | |||

| | title = ''Report 87: Psychological Evaluation and Gun Control'' | |||

| | publisher = Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology | |||

| | date = 1996 | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-03-07}}</ref> | |||

| The ] placed an absolute ban on certain types of weapons, including automatic or self-loading guns.<ref>{{UK-SLD|1628564|the Firearms Act 1968}}</ref> Since then only the armed forces and police have had access to these types of arms. The ] extended the provision of the 1968 Act, including control of imitation firearms. The ] and ] introduced further very significant restrictions.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.opsi.gov.uk/ACTS/acts1997/1997005.htm | |||

| | title = Firearms (Amendment) Act 1997 | |||

| | publisher = Office of Public Sector Information | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-03-07}} and {{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.opsi.gov.uk/ACTS/acts1997/1997064.htm | |||

| | title = Firearms (Amendment) (No. 2) Act 1997 | |||

| | publisher = Office of Public Sector Information | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-03-07}}</ref> This has led, in effect, to a total ban on private possession of pistols even for competitive sporting purposes. ] rifles remain permitted for competition however. | |||

| Following the ], the ] criminalised the possession of virtually all ] in the United Kingdom. | |||

| The ] has brought certain types of air weapons into the categories of control created by the firearms acts.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.met.police.uk/firearms-enquiries/new_legis.htm | |||

| | title = ''New Legislation'' | |||

| | publisher = The Metropolitan Police | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-03-07}}</ref> | |||

| ] often gives considerable powers to ministers to issue regulations that control the way the various acts are applied. In relation to firearms this power generally falls to the ]. The ] therefore has some control of the conditions under which firearms can be licensed. On a few occasions over the years permits have been granted to private individuals to keep firearms for personal protection, for example during "]" in ], however these are very limited and exceptional cases. | |||

| ====United States of America==== | |||

| {{see|Law of the United States|Firearm case law in the United States|Gun laws in the United States (by state)}} | |||

| According to gun-control proponent ], founder of the ], in the United States the meaning of "bear arms" is a matter of recent dispute and continuing political debate, although this belief is controversial.<ref name="Brady000">{{cite book | |||

| | title = A Good Fight | |||

| | first = Sarah | |||

| | last = Brady | |||

| | publisher = Public Affairs | |||

| | year = 2002 | |||

| | id = ISBN 1586481053 | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="Spitzer000">{{cite book | |||

| | title = The Second Amendment "Right to Bear Arms" and United States v. Emerson | |||

| | first = Robert J. | |||

| | last = Spitzer | |||

| | publisher = 77 St. John's L. Rev | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| }}</ref> One argument is whether the expression involves the rights of an '']'' to 'keep and bear arms', or whether, according to Sarah Brady, it relates exclusively to a military service meaning of 'bear arms' as with the functioning and maintenance of an organized '']'', although this belief is controversial.<ref name="Brady000">(Brady 2002) pp. 102-104</ref> | |||

| Historically, the right to keep and bear arms, whether considered an individual or a collective or a militia right, did not originate fully-formed in the ] in 1791; rather, the ] was the codification of the six centuries old responsibility to keep and bear arms for king and country that was inherited from the English Colonists that settled North America, tracing its origin back to the ] of 1181 that occurred during the reign of Henry II. Through being codified in the ], the common law right was continued and guaranteed for the People, and statutory law enacted subsequently by Congress cannot extinguish the pre-existing common law right to keep and bear arms. | |||

| This right is often presented in the United States as synonymous with the ], although this belief is controversial. {{Fact|date=May 2008}} | |||

| *] Protects the pre-existing right to keep and bear arms. | |||

| {{cquote|A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the People to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.}} | |||

| The right is often presented in the United States as being an unenumerated, pre-existing right, such as provided for by the ], although this belief is controversial. | |||

| *] Provides for unenumerated rights, including implicitly a right to keep and bear arms and a right to have arms for defense, hunting, sport, etc.. | |||

| {{cquote|The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.}} | |||

| Some have seen the Second Amendment as derivative of a common law right to keep and bear arms; Thomas B. McAffee & Michael J. Quinlan, writing in the North Carolina Law Review, March 1997, Page 781, have stated ''"... Madison did not invent the right to keep and bear arms when he drafted the Second Amendment--the right was pre-existing at both common law and in the early state constitutions."''<ref name='nclr'> {{cite journal|title=BRINGING FORWARD THE RIGHT TO KEEP AND BEAR ARMS: DO TEXT, HISTORY, OR PRECEDENT STAND IN THE WAY?|journal=North Carolina Law Review|date=1997-03|first=Thomas B.|last=McAffee|coauthors=Michael J. Quinlan|volume=|issue=|pages=781|id= |url=|format=|accessdate=2008-05-10 }}</ref> | |||

| Akhil Reed Amar similarly notes in the Yale Law Journal, April 1992, Page 1193, the basis of Common Law for the first ten amendments of the U.S. Constitution, "following John Randolph Tucker's famous oral argument in the 1887 Chicago anarchist case, Spies v. Illinois": <blockquote>''Though originally the first ten Amendments were adopted as limitations on Federal power, yet insofar as they secure and recognize '''fundamental rights -- common law rights -- of the man, they make them privileges and immunities of the man as citizen of the United States'''...''<ref name='ylj1'> {{cite journal|title=THE BILL OF RIGHTS AND THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT|journal=Yale Law Journal|date=1992-04|first=Akhil|last=Amar|coauthors=|volume=|issue=|pages=1193|id= |url=|format=|accessdate=2008-05-10 }}</ref> </blockquote> | |||

| A new proposal was entered by 35 Senators in September 2019<ref>{{Citation | |||

| Uviller and Merkel hold that the right to bear arms was not reserved for the state, but rather was an individual and personal right for arms only to the extent needed to maintain a well regulated militia to support the state. They also hold that a militia recognizable to the framers of the Constitution has ceased to exist in the United States resulting from deliberate Congressional legislation and also societal neglect; nonetheless, "Technically, all males aged seventeen to forty-five are members of the unorganized militia, but that status has no practical legal significance."<ref name="isbn0-300-09562-7">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Senate of the Czech Republic | |||

| |author=Williams, David H. | |||

| | year = 2020 | |||

| |title=The mythic meanings of the Second Amendment: taming political violence in a constitutional republic | |||

| | title = Detail historie tisku č. 135 | |||

| |publisher=Yale University Press | |||

| | publisher = Senate of the Czech Republic | |||

| |location=New Haven, Conn | |||

| | location = Prague | |||

| |year=2003 | |||

| | url = https://senat.cz/xqw/xervlet/pssenat/historie?ke_dni=17.8.2020&O=12&action=detail&value=4471 | |||

| |pages=Pg 78 | |||

| | access-date = 17 August 2020 | |||

| |isbn=0-300-09562-7 | |||

| | language = cs | |||

| |quote=Technically, all males aged seventeen to forty-five are members of the unorganized militia, but that status has no practical legal significance. Such "militia members" are not required to own guns, to drill together, or to learn virtue. The statutory provision creating this "universal militia" is nothing more than a dim memory of a distant hope. | |||

| }}</ref> and then approved on 21 July 2021, adding a new sentence, according to which "the right to defend one's own life or the life of another person even with the use of a weapon is guaranteed under the conditions set by the law."<ref>{{Cite web|date=2021-07-21|title=The right to bear arms in self-defense is embedded in the Czech constitution|url=https://www.expats.cz/czech-news/article/right-to-arms-embedded-in-czech-consitution|access-date=2021-07-22|website=www.expats.cz|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| |doi= | |||

| The provision is interpreted as guaranteeing legal accessibility of arms in a way that must ensure possibility of effective self-defense<ref>{{cite book | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="isbn0-8223-3017-2">{{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Bartošek | |||

| |author=Merkel, William G.; Uviller, H. Richard | |||

| | first1 = Jan | |||

| |title=The militia and the right to arms, or, How the second amendment fell silent | |||

| | last2 = Bačkovská | |||

| |publisher=Duke University Press | |||

| | first2 = Milena | |||

| |location=Durham, N.C | |||

| | author-link = | |||

| |year=2002 | |||

| | date = 2021 | |||

| |pages=Chapter 7, pages 151-152 | |||

| | title = Zbraně a střelivo | |||

| |isbn=0-8223-3017-2 | |||

| | url = https://search.mlp.cz/cz/titul/zbrane-a-strelivo/4634451/ | |||

| |quote=Given the continued vitality of the social role of armed troops, has the institution of the militia evolved into a viable military force in America today? Medieval monks might enjoy the question: is a military force that developed out of an ancient construct known as "the militia" still a militia though it boasts none of the defining characteristics of that form of military organization, and is, actually, in character the contradiction of many of them? It's a little like the parable of Aristotle's knife: if I break the blade of my knife and replace it, and then put a new handle on it, is it still the same knife? | |||

| | location = Praha | |||

| |oclc= | |||

| | publisher = C. H. Beck | |||

| |doi= | |||

| | page = 209 | |||

| | isbn = 978-80-7400-843-6 | |||

| }}</ref> and as constitutional stipulation which underscores the individual right to be prepared with arms against an eventual attack, i.e. that courts cannot draw a negative inference from the fact that a defender had been preparing to avert a possible attack with use of weapons.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Gawron | |||

| | first = Tomáš | |||

| | author-link = | |||

| | date = 2023 | |||

| | title = Nutná obrana v právní praxi | |||

| | url = https://knihovna.usoud.cz/arl-us/cs/detail-us_us_cat-0054718-Nutna-obrana-v-pravni-praxi/?disprec=1&iset=1 | |||

| | location = Brno | |||

| | publisher = Václav Klemm | |||

| | page = 30 | |||

| | isbn = 978-80-87713-23-5 | |||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| ====Switzerland==== | |||

| <blockquote>"From the text as well as a fair understanding of the contemporary ethic regarding arms and liberty, it seems to us overwhelmingly evident that the principal purpose of the Amendment was to secure a personal, individual entitlement to the possession and use of arms. We cannot, however, (as the individual rights contingent generally does) disregard entirely the first part of the text proclaiming a well regulated militia necessary to the security of a free state."<ref name = "UM23">Uviller, H. Richard. & Merkel, William G.: ''The Militia and the Right to Arms, Or, How the Second Amendment Fell Silent '', Page 23. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3017-2</ref></blockquote> | |||

| {{quote box|align=right|quote= | |||

| The right to acquire, keep and bear arms is guaranteed within boundaries of this law. | |||

| |source=Article 3 of Swiss Firearms Act | |||

| |width=40%}} | |||

| {{Further|Gun laws in Switzerland}} | |||

| The Swiss have a statutory right to bear arms under Article 3 of the 1997 Weapons Act.<ref name=WG>{{cite web |url=http://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19983208/index.html |title=SR 514.54 Bundesgesetz über Waffen, Waffenzubehör und Munition (Waffengesetz WG) |publisher=The Swiss Federal Council |location=Berne, Switzerland |type=official site |language=de, it, fr |date=1 July 2016 |access-date=2015-06-10}}</ref>{{refn|group=lower-alpha|"Art. 3 Recht auf Waffenerwerb, Waffenbesitz und Waffentragen: Das Recht auf Waffenerwerb, Waffenbesitz und Waffentragen ist im Rahmen dieses Gesetzes gewährleistet." (The right to acquire, possess and carry arms is guaranteed in the framework of this law.)}} ] practices ], which requires that all able-bodied male citizens keep a firearm at home in case of a call-up. Each male between the ages of 20 and 34 is considered a candidate for conscription into the military, and following a brief period of active duty will commonly be enrolled in the ] until age or an inability to serve ends his obligation.<ref>.</ref> Until December 2009, these men were required to keep their government-issued ] combat rifles and semi-automatic handguns in their homes as long as they were enrolled in the armed forces.<ref name="jrlnr">{{cite news|last=Lott |first=John R. |url=http://www.nationalreview.com/comment/lott200310020833.asp |title=Swiss Miss|work=National Review|date=October 2, 2003 |access-date=March 17, 2010}}</ref> Since January 2010, they have had the option of depositing their personal firearm at a government arsenal.<ref>{{cite web|title=Hinterlegung der persönlichen Waffe|url=http://www.lba.admin.ch/internet/lba/de/home/themen/pers0/bewaffnung/hinterlegung_der_persoenlichen.html|publisher=Logistikbasis der Armee, Eidgenössisches Departement für Verteidigung, Bevölkerungsschutz und Sport|access-date=4 May 2013}}</ref> Until September 2007, soldiers received 50 rounds of government-issued ammunition in a sealed box for storage at home; after 2007 only about 2,000 specialist troops are allowed to keep the ammunition at home.<ref>{{cite news|title= Soldiers can keep guns at home but not ammo |publisher=]|date=27 September 2007|url=http://www.swissinfo.org/eng/search/Result.html?siteSect=882&sid=8470114}}</ref> | |||

| In ], voters rejected a citizens' initiative that would have obliged members of the armed services to store their rifles and pistols on military compounds and required that privately owned firearms be registered.<ref name="bbc.co.uk">{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-12441834 |title=Switzerland rejects tighter gun controls |date=13 February 2011 |newspaper=]}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>"...we understand the Second Amendment as though it read: ''"Inasmuch as and so long as a well regulated Militia shall be necessary to the security of a free state and so long as privately held arms shall be essential to the maintenance thereof, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed."'' "..to us, the language of the Amendment cannot support a right to personal weaponry independent of the social value of a regulated organization of armed citizens.."<ref name = "UM24">Uviller, H. Richard. & Merkel, William G.: ''The Militia and the Right to Arms, Or, How the Second Amendment Fell Silent '', Page 24. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3017-2</ref></blockquote> | |||

| <!-- THERE IS NOTHING IN THE TEXT SUGGESTING LEGAL RECOGNITION OF RKBA IN UKRAINE. DO NOT ADD UKRAINE WITHOUT PROPER EXPLANATION HOW RKBA IS RECOGNIZED IN NATIONAL LAW. MAY ISSUE SYSTEM IS ANTITHESIS OF RKBA | |||

| ====Ukraine==== | |||

| {{Further|Gun law in Ukraine}} | |||

| The right to keep and bear arms in Ukraine was expanded to include open carry by all citizens on February 23, 2022,<ref>{{Cite news |last=Reuters |date=2022-02-23 |title=Ukraine MPs vote to give permission for civilians to carry firearms |language=en |work=Reuters |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraine-mps-vote-give-permission-civilians-carry-firearms-2022-02-23/ |access-date=2022-09-14}}</ref> in response to the ] The move to expand the right to carry arms for all citizens of Ukraine was viewed as highly popular by Ukrainians.<ref name="Ukrainians Take Up Arms in Self Defense – Reason – J.D. Tuccille">{{cite web |last1=Tuccille |first1=J.D. |title=Ukrainians Take Up Arms in Self Defense |url=https://reason.com/2022/03/02/ukrainians-take-up-arms-in-self-defense/ |website=reason.com |date=2 March 2022 |publisher=Reason |access-date=11 March 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ===== Early commentary about the right to bear arms in state courts of the United States ===== | |||

| --> | |||

| The Second Amendment of the United States Constitution is a Federal provision. Each of the fifty states also has its own state constitution addressing their specific state. Forty-four states have chosen to embody explicitly a right to bear arms into their state's constitution,<ref name='staterkba'> {{cite web|url=http://www.law.ucla.edu/volokh/beararms/statecon.htm |title=State Constitutional Right to Keep and Bear Arms Provisions |accessdate=2008-05-10 |last=Volokh |first=Eugene |date=2006 |publisher=UCLA }}</ref> and six states have chosen explicitly not to do so. | |||

| ====United Kingdom==== | |||

| Of the forty-four states that have chosen to embody explicitly a right to bear arms into their state's constitution, approximately thirty-one have explicitly chosen to include the right to arms for "individual right", "defense of self", "defense of home" or similarly worded reasons. Approximately thirteen states, as with the Federal Constitution, did not choose to include explicitly "individual", "self" or "home" wording associated with a right to bear arms for their specific state. | |||

| {{quote box | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | quote = That the Subjects which are Protestants may have Arms for their Defence suitable to their Conditions and as allowed by Law. | |||

| | source = Bill of Rights 1689 | |||

| | width = 40% | |||

| }} | |||

| {{See also|Firearms policy in the United Kingdom}} | |||

| {{See also|Self-defence in English law}} | |||

| {{See also|Offensive weapon#UK}} | |||

| In the ], there is no automatic right to bear arms,<ref name="SydneySchoolOfPublicHealth2015">{{cite web|author1=Alpers, Philip |author2=Wilson, Marcus |author3=Rossetti, Amélie |author4=Salinas, Daniel |url=http://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/region/united-kingdom |title=United Kingdom – Gun Facts, Figures and the Law – Gun regulation, Right to Possess Firearms |publisher=Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney|date=2015-04-29 |access-date=2015-05-13}}</ref> although citizens may possess certain firearms on obtaining an appropriate licence.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/518193/Guidance_on_Firearms_Licensing_Law_April_2016_v20.pdf |title=Guide on Firearms Licensing Law |website=www.gov.uk |date=April 2016}}</ref> Ordinary members of the public may own sporting rifles and shotguns, subject to licensing, while ]s, ], and ] ] weapons are illegal to possess without special additional conditions.<ref name="SydneySchoolOfPublicHealth2015"/><ref>{{cite journal| last =Kopel| first =David| title =It isn't about duck hunting: The British origins of the right to arms| journal =Michigan Law Review| issue =6| pages =1333–1362| publisher =Michigan Law Review Association| year =1995| volume =93| doi =10.2307/1289883| jstor =1289883| url =http://www.guncite.com/journals/dk-dhunt.html| access-date = 7 April 2013}}</ref> | |||

| When not attended, all licensed firearms must be stored securely (locked) and separate from their ammunition. ] are less stringent and air pistols with a muzzle energy not exceeding 6 foot-pounds force (8.1 joules) and other airguns with a muzzle energy not exceeding 12 ft⋅lbf (16 J) do not require any certificates or licensing, although the same storage requirement applies. | |||

| The first serious control on firearms was established with the passing of the ],<ref>{{cite web|author=John Pate |url=http://www.dvc.org.uk/dunblane/pistolsact.html |title=Dunblane Massacre Resource Page – Pistols Act, 1903 |publisher=Dvc.org.uk |date=1903-08-11 |access-date=2012-05-22}}</ref> handgun restrictions being added in response to the 1996 ] in which 18 people died. | |||

| Historically the English ] allowed: | |||

| Of the forty-four states, approximately twenty-eight have explicitly chosen to include the right to bear arms for "security of a free state", "defense of state", "common defense" or similarly worded reasons, as with the Federal Constitution. Approximately sixteen states did not choose to include explicitly "free state", "defense of state" or "common defense" wording for their specific state. Whether the inclusion of these kinds of wording in state constitutions has relevance to the issue of whether implicit "individual" rights exist, or whether such rights (if any) are implicitly protected by the states' constitutions or by the Federal Constitution's Second Amendment, remains a matter of dispute. | |||

| {{blockquote|That the Subjects which are ] may have Arms for their Defence suitable to their Conditions and as allowed by Law.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/aep/WillandMarSess2/1/2/introduction/data.htm|title=Bill of Rights |website=www.legislation.gov.uk}}</ref>}} | |||

| Since 1953, it has been a criminal offence in the United Kingdom to carry a knife (with the exception of non-locking folding knives with a cutting edge of 3 inches (7.62 centimetres) or less) or any "]" in a public place without lawful authority (e.g. police or security forces) or reasonable excuse (e.g. tools that are needed for work). The cutting edge of a knife is separate to the blade length. The only manner in which an individual may carry arms is on private property or any property to which the public does not have a lawful right of access (e.g., a person's own home, private land, the area in a shop where the public have no access, etc.), as the law only creates the offence when it occurs in public.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Eliz2/1-2/14/section/1/data.htm|title=Prevention of Crime Act 1953|website=www.legislation.gov.uk|access-date=2019-08-23}}</ref><ref name="cps.gov.uk">{{cite web|url=https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/offensive-weapons-knives-bladed-and-pointed-articles|title=Offensive Weapons, Knives, Bladed and Pointed Articles {{!}} The Crown Prosecution Service|website=www.cps.gov.uk|access-date=2019-08-23}}</ref> Furthermore, ] Section 141 specifically lists all ]s that cannot technically be owned, even on private property, by way of making it illegal to sell, trade, hire, etc. an offensive weapon to another person.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/33/section/141/data.htm|title=Criminal Justice Act 1988|website=www.legislation.gov.uk|access-date=2019-08-23}}</ref> | |||

| Regarding the state interpretations of these state and the federal constitutional rights to bear arms, state courts have addressed the meaning of these specific rights in considerable detail. Two different models have emerged from state ]: an individual right and a collective right. | |||

| Furthermore, the law does not allow an offensive weapon or ordinary item intended or adapted as an offensive weapon to be carried in public before the threat of violence arises. This would only be acceptable in the eyes of the law if the person armed themselves immediately preceding or during an attack (in a public place). This is known as a "]" or "instantaneous arming".<ref name="cps.gov.uk"/> | |||

| In ''Bliss v. Commonwealth'' (1822, KY),<ref name="bliss v commonwealth">{{cite court |litigants=Bliss v. Commonwealth |vol=2 |reporter=Littell |opinion=90 |date=KY 1882 |url=http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/usr/wbardwel/public/nfalist/bliss_v_commonwealth.txt}}</ref> which evaluated the right to bear arms in defence of themselves and the state pursuant to Section 28 of the Second Constitution of ] (1799), the right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state was interpreted as an individual right, for the case of a concealed sword cane. This case has been described as about “a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons was violative of the Second Amendment””. <ref name = "1967hearing">United States. Anti-Crime Program. Hearings Before Ninetieth Congress, First Session. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off, 1967, p. 246.</ref> As stated by the Kentucky High Court, "But it should not be forgotten, that it is not only a part of the right that is secured by the constitution; it is the right entire and complete, as it existed at the adoption of the constitution; and if any portion of that right be impaired, immaterial how small the part may be, and immaterial the order of time at which it be done, it is equally forbidden by the constitution."<ref name="bliss v commonwealth"/> The "constitution" mentioned in this quote refers to Kentucky's Constitution.<ref name="rkba1982">Right to Keep and Bear Arms, U.S. Senate. 2001 Paladin Press. ISBN 1581602545.</ref> As mentioned in this quotation "as it existed at the adoption of the constitution" was the pre-existing right in force when Kentucky's First Constitution was drawn in 1799.<ref>The Second Amendment became effective ], ], and was still a new concept in 1799.</ref> | |||

| ===Other=== | |||

| The case prompted outrage in the Kentucky House, all the while recognizing that Section 23 of the Second Constitution of Kentucky (1799), which stated "That the right of the citizens to bear arms in defence of themselves and the State shall not be questioned."<ref>Commonwealth of KY Const. of 1799, art. , x§ 23</ref> did guarantee individuals the right to bear arms. | |||

| ====Sharia law==== | |||

| The result was that the law of the Commonwealth of Kentucky was eventually over-turned by constitutional amendment with Section 26 in Kentucky's Third Constitution (1850) banning the future carrying of concealed weapons, while still asserting that the bearing of arms in defense of themselves and the state was an individual and collective right in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. This recognition, has remained to the present day in the Commonwealth of Kentucky's Fourth Constitution enacted in 1891, in Section 1, Article 7, that guarantees "The right to bear arms in defense of themselves and of the State, subject to the power of the General Assembly to enact laws to prevent persons from carrying concealed weapons." As noted in the Northern Kentucky Law Review Second Amendment Symposium: Rights in Conflict in the 1980’s, vol. 10, no. 1, 1982, p. 155, "The first state court decision resulting from the "right to bear arms" issue was ''Bliss v. Commonwealth''. The court held that "the right of citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State must be preserved entire, . . ."" "This holding was unique because it stated that the right to bear arms is absolute and unqualified."<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pierce |first=Darell R. |title=Second Amendment Survey |journal=Northern Kentucky Law Review Second Amendment Symposium: Rights in Conflict in the 1980's |volume=10 |issue=1 |date=1982 |pagest=155}}</ref><ref>Two states, ] and ], do not require a permit or license for carrying a concealed weapon to this day, following Kentucky's original position.</ref> | |||

| Under ], there is an intrinsic freedom to own arms. However, in times of civil strife or internal violence, this right can be temporarily suspended to keep peace and prevent harm, as mentioned by Imam ash-Shatibi in his works on Maqasid ash-Shari'ah (The Intents and Purposes of Shari'ah).<ref name="p.60 Imam Al-Shatibi's Theory of the Higher Objectives and Intents of Islamic Law">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Zt8I2GwVZs8C|author=Aḥmad Raysūnī |title=Imam Al-Shatibi's Theory of the Higher Objectives and Intents of Islamic Law |year=2005 |page=60 |publisher=International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT) |isbn=978-1565644120 |access-date=October 13, 2012}}</ref><ref name="Purpose of Islamic Law">{{cite web |url=http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/1565644123/mower.shocksale-20 |title=Purpose of Law |format=Book |work=Imam Al-Shatibi's Theory of the Higher Objectives and Intents of Islamic Law (Paperback) | |||

| }}</ref> Citizens not practicing Islam are prohibited from bearing arms and are required to be protected by the military, the state for which they pay the ]. In exchange they do not need to pay the ].<ref name="isbn0-8133-3885-9">{{cite book |author1=Goldschmidt, Arthur |author2=Goldscmidt Jr., Arthur |title=A concise history of the Middle East |publisher=Westview Press |location=Boulder, Colo |year=2002 |page= |isbn=0813338859 |url=https://archive.org/details/concisehistoryof00gold/page/108 }}</ref><ref>حر عاملی، وسائل الشیعه، بیروت، ۱۴۰۳، ج۳، ص۳۸، باب۲۴، ح۲، و کلینی، محمد بن یعقوب، فروع کافی، تهران، ۱۳۱۲، ج۲، ص۱۱۷، و نجفی، محمد حسن، جواهر الکلام، بیروت، چاپ مؤسسة تاریخ عربی، ج ۱۱، ص ۳۳۱.</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.isna.ir/news/92100100355/%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%AC%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%87-%DA%86%D9%87-%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AD%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%B3%D8%AA-%D9%85%DB%8C-%DA%AF%DB%8C%D8%B1%D9%86%D8%AF-%D8%AA%D8%B5%D8%A7%D9%88%DB%8C%D8%B1 | title=امامان جمعه چه سلاحی دست میگیرند؟ + تصاویر | date=22 December 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.yjc.news/fa/news/7006374/%D8%AA%DA%A9%DB%8C%D9%87-%D8%A8%D8%B1-%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AD-%D8%B6%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%A7%D8%B2-%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AD-%D8%AA%D9%88%D8%B3%D8%B7-%D8%AE%D8%B7%DB%8C%D8%A8-%D8%AC%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%87-%D9%81%DB%8C%D9%84%D9%85 | title=تکیه بر سلاح؛ ضرورت استفاده از سلاح توسط خطیب جمعه +فیلم }}</ref> | |||

| ====Yemen==== | |||

| That the decision of ''Bliss'' not be viewed as being solely about the Commonwealth of Kentucky's law is also seen from the defense subsequently given against a murder charge in Kentucky against Mattews Ward, who in 1852 pulled out a concealed pistol and fatally wounded his brother's teacher over an accusation regarding eating chestnuts in class. Ward's defense team consisted of eighteen lawyers, including U.S. Senator ], former Governor of Kentucky, and former ]. The defense successfully defended Ward in 1854 through an assertion that “a man has a right to carry arms; I am aware of nothing in the laws of God or man, prohibiting it. The Constitution of Kentucky and our Bill of Rights guarantee it. The Legislature once passed an act forbidding it, but it was decided unconstitutional, and overruled by our highest tribunal, the Court of Appeals.” As noted by Cornell, “Ward's lawyers took advantage of the doctrine advanced in ''Bliss'' and wrapped their client's action under the banner of a constitutional right to bear arms. Ward was acquitted.”<ref name="Saul_Cornell_AWRM_Ward">{{cite book | |||

| {{quote box|align=right|quote=The citizens of the Republic shall have the right to hold the necessary rifles, machine guns, revolvers, and hunting rifles for their personal use with an amount of ammunition for the purpose of legitimate defense.<ref>, ''Gunpolicy.org'' (accessed 29 August 2019)</ref> | |||

| |author=Cornell, Saul | |||

| |source=Law Regulating Carrying Firearms, Ammunition & their Trade | |||

| |title=A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA -- The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America | |||

| |width=40%}} {{main|Gun law in Yemen}} | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| Yemen recognizes statutory right to keep and bear arms. Firearms are both easily and legally accessible.<ref name="Yemeni gun market">, Yemeni gun market.</ref><ref name="Yemeni gun laws">, Gun policy in Yemen</ref> | |||

| |location=New York, New York | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |pages=pp. 147-149 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-19-514786-5 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| In contrast, in ''State v. Buzzard'' (1842, Ark), the Arkansas high court adopted a militia-based, political right, reading of the right to bear arms under state law, and upheld the 21st section of the second article of the Arkansas Constitution that declared, "that the free white men of this State shall have a right to keep and bear arms for their common defense",<ref name="state v buzzard">{{Cite court |litigants=State v. Buzzard |vol=4 |reporter=Ark. (2 Pike) |opinion=18 |date=1842 |url=http://www.constitution.org/2ll/2ndcourt/state/191st.htm}}</ref> while rejecting a challenge to a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons. Buzzard had carried a concealed weapon and stood "indicted by virtue of the authority of the 13th section of an act of the Legislature prohibiting any person wearing a ], ], large knife or sword-cane concealed as a weapon, '''unless upon a journey''', under the penalties of fine and imprisonment." The Arkansas high court further declared "That the words "a well regulated militia being necessary for the security of a free State", and the words "common defense" clearly show the true intent and meaning of these Constitutions and prove that it is a political and not an individual right, and, of course, that the State, in her legislative capacity, has the right to regulate and control it: This being the case, then the people, neither individually nor collectively, have the right to keep and bear arms." Joel Prentiss Bishop’s influential ''Commentaries on the Law of Statutory Crimes'' (1873) took Buzzard's militia-based interpretation, a view that Bishop characterized as the “Arkansas doctrine", as the orthodox view of the right to bear arms in American law.<ref name="state v buzzard"/><ref name="Saul_Cornell_AWRM_Bishop">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Cornell, Saul | |||

| |title=A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA -- The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |location=New York, New York | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |pages=p. 188 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-19-514786-5 | |||

| |quote=”Dillon endorsed Bishop's view that ''Buzzard's'' “Arkansas doctrine,” not the libertarian views exhibited in ''Bliss, captured the dominant strain of American legal thinking on this question.” | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == Gun violence and the politics of the right to bear arms == | |||

| Modern gun rights advocates have disputed this history, claiming that the ''individual right'' was the orthodox view of the right to bear arms under state law in the 19th century, citing the previously-mentioned ''Bliss v. Commonwealth'', and even ''State v. Buzzard'', which recognized the right of an individual to carry a weapon concealed, when '''upon a journey''', in an affirmative defense. Similarly, political scientist Earl Kruschke has categorized both ''Bliss'' and ''Buzzard'' as being “cases illustrating the individual view.”<ref name="Kruschke_individual_rights">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Kruschke, Earl R. | |||

| |title=Gun control: a reference handbook | |||

| |publisher=ABC-CLIO | |||

| |location=Santa Barbara, Calif | |||

| |year=1995 | |||

| |pages=pp. 140-143 | |||

| |isbn=0-87436-695-X | |||

| |oclc= | |||

| |doi= | |||

| }}</ref> Since 1873, some legal and constitutional historians have sided with Bishop and not the individual rights model.<ref> See the symposium in Chicago Kent Law Review 76 and the Fordham Law Review vol. 73</ref> Other legal and constitutional historians have sided with the individual rights model.<ref name="Volokh">{{Cite journal |last=Volokh |first=Eugene |title=Testimony of Eugene Volokh on the Second Amendment, Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution, Sept. 23, 1998 |journal=] |date=November/December 1988 |pages=pp. 23 |url=http://www.law.ucla.edu/volokh/beararms/testimon.htm#14 |quote="A recent exhaustive study reveals that there was exactly one statement in the 1800s cases or commentaries supporting the collective rights view, a concurring opinion in an 1842 Arkansas state court case."}}</ref> | |||

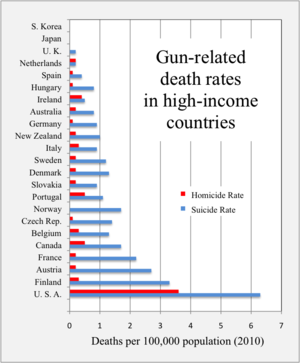

| ] countries, 2010, countries in graph ordered by total death rates (homicide plus suicide plus other gun-related deaths)<ref name="AJM201603">{{cite journal |last1=Grinshteyn |first1=Erin |last2=Hemenway |first2=David |title=Violent Death Rates: The US Compared with Other High-income OECD Countries, 2010 |journal=] |date=March 2016 |volume=129 |issue=3 |pages=266–273 |doi=10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025 |pmid=26551975 |doi-access=free }} (). ().</ref>]] | |||

| In 1905, the ] Supreme Court in ''Salina v. Blaksley''<ref>{{Cite court |litigants=City of Salina v. Blaksley |vol=72 |reporter=Kan. |opinion=230 |date=1905 |url=http://www-2.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/user/wbardwel/public/nfalist/salina_v_blaksley.txt}}</ref> made the first ''collective right'' judicial interpretation.<ref name="Saul_Cornell_AWRM_Salina">{{cite book | |||

| ] | |||

| |author=Cornell, Saul | |||

| Legal restrictions on the right to keep and bear arms are usually put in place by legislators in an attempt to reduce ] and crime.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://abcnews.go.com/WNT/International/Story?id=3066193&page=1 |title=U.K. Response to School Massacre: Ban Handguns |first=David |last=Wright |date=April 22, 2007 |work=ABC News }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/11/29/europe/union.php |title=EU legislators push tougher gun controls |work=] |date=November 29, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080208193010/http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/11/29/europe/union.php |archive-date=February 8, 2008 }} </ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1999/12/01/us/clinton-calls-brady-law-a-success-and-backs-more-limits.html |title=President Clinton Calls Brady Law a Success and Backs More Limits |work=] |date=December 1, 1999 }}</ref> Their actions may be the result of political groups advocating for such regulations. The ], ], and the ] are examples of campaigns calling for tighter restrictions on the right to keep and bear arms. Accident statistics can be hard to obtain, but much data is available on the issue of gun ownership and gun related deaths. | |||

| |title=A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA -- The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |location=New York, New York | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |pages=p. 258 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-19-514786-5 | |||

| |quote=”... the Kansas Supreme Court had used a similar formulation of the the right to bear arms a decade earlier, describing this right as one that “refers to the people as a collective body.”” | |||

| }}</ref> The Kansas high court declared: "That the provision in question applies only to the right to bear arms as a member of the state militia, or some other military organization provided for by law, is also apparent from the second amendment to the federal Constitution, which says: "A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed."" | |||

| === United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute === | |||

| A modern formulation of the debate over the Second Amendment as an individual/collective rights dichotomy “was the emergence of the collective rights reading of '']''"<ref name="Saul_Cornell_AWRM_Emery">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Cornell, Saul | |||

| |title=A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA -- The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |location=New York, New York | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |pages=p. 198 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-19-514786-5 | |||

| }}</ref> that became better known when it was employed in “a short but influential article”<ref name="Saul_Cornell_AWRM_Emery">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Cornell, Saul | |||

| |title=A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA -- The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |location=New York, New York | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |pages=p. 198 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-19-514786-5 | |||

| }}</ref> in the '']'' article in 1915 by the Chief Justice of the ] Supreme Court, Lucilius A. Emery. He noted that "the right guaranteed is not so much to the individual for his private quarrels or feuds as to the people collectively for the common defense against the common enemy, foreign or domestic."<ref name="Emery">{{Cite journal |title=The Constitutional Right to Keep and Bear Arms |volume=28 |journal=] |pages=473–477 |last=Emery |first=Lucilius A. |year=1914–1915 |url=http://www.guncite.com/journals/har1915.html}}</ref> | |||

| The ] (UNICRI) has made comparisons between countries with different levels of gun ownership and investigated the correlation between gun ownership levels and gun homicides, and between gun ownership levels and gun suicides. A "substantial correlation" is seen in both:<ref name="UNICRI">{{cite book |last=Killias |first=Martin |year=1993 |chapter=Gun Ownership, Suicide and Homicide: An International Perspective |editor1-first=Anna |editor1-last=Alvazzi del Frate |editor2-first=Ugljesa |editor2-last=Zvekic |editor3-first=Jan J. M. |editor3-last=van Dijk |title=Understanding Crime, Experiences of Crime and Crime Control – Acts of the International Conference, Rome, 18–20 Nov 1992 |pages=289–306 |location=Rome |publisher=United Nations International Crime & Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) |isbn=9290780231 |chapter-url=http://www.unicri.it/wwk/publications/books/series/understanding/19_GUN_OWNERSHIP.pdf |quote=During the 1989 and 1992 International Crime Surveys data on gun ownership in eighteen countries have been collected on which WHO data on suicide and homicide committed with guns and other means are also available. The results ... based on the fourteen countries surveyed during the first ICS and on rank correlations...suggested that gun ownership may increase suicides and homicides using firearms, while it may not reduce suicides and homicides with other means. |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080107174528/http://www.unicri.it/wwk/publications/books/series/understanding/19_GUN_OWNERSHIP.pdf |archive-date=2008-01-07 }}</ref> | |||

| ===== Modern commentary about the right to keep and bear arms in the United States: three models ===== | |||