| Revision as of 06:32, 4 June 2008 editDanu Widjajanto (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,613 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:54, 13 January 2025 edit undoDOG OF VENICE (talk | contribs)45 editsm Adding Yvelines and Île-de-France | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Former royal residence in Versailles, France}} | |||

| {{Infobox World Heritage Site | |||

| {{Redirect|Versailles|the commune|Versailles, Yvelines|other uses|Versailles (disambiguation)}} | |||

| | WHS = Palace and Park of Versailles | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| | Image = ] | |||

| {{Infobox building | |||

| | State Party = {{FRA}} | |||

| | |

| name = Palace of Versailles | ||

| | native_name = {{native name|fr|Château de Versailles}} | |||

| | Criteria = i, ii, vi | |||

| | |

| logo = | ||

| | logo_size = 300 | |||

| | Region = ] | |||

| | |

| image = {{photomontage | ||

| | photo1a = Versailles-Chateau-Jardins02.jpg | |||

| | Session = 3rd | |||

| | photo2a = Chateau Versailles Galerie des Glaces.jpg | |||

| | Link = http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/83 | |||

| | photo3a = | |||

| | size = 300 | |||

| | color = transparent | |||

| | border = 0 | |||

| | foot_montage = Garden façade and fountains; ]}} | |||

| |mapframe-frame-width=300 | |||

| |mapframe=yes | |||

| |mapframe-caption=Interactive fullscreen map | |||

| |mapframe-zoom=14 | |||

| |mapframe-marker=museum | |||

| |mapframe-wikidata=yes | |||

| |coordinates={{WikidataCoord|display=it}} | |||

| | location = ], France | |||

| | start_date = {{Start date and age|1661}} | |||

| | architectural_style = ] and ] | |||

| | owner = Government of France | |||

| | website = {{URL|en.chateauversailles.fr}} | |||

| | embedded = {{Infobox UNESCO World Heritage Site | |||

| |child = yes | |||

| |Official_name = Chateau and Park of Versailles | |||

| |ID = 83 | |||

| |Year = 1979 | |||

| |Criteria = Cultural: i, ii, vi | |||

| |Area = {{convert|800|ha|abbr=on}} | |||

| |Buffer_zone = {{convert|9,467|ha|abbr=on}} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Palace of Versailles''', or simply '''Versailles''', is a royal ] in ], ]. | |||

| The '''Palace of Versailles''' ({{IPAc-en|v|ɛər|ˈ|s|aɪ|,_|v|ɜːr|ˈ|s|aɪ}} {{respell|vair|SY|,_|vur|SY}};<ref>{{cite web|title=Versailles|url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/versailles|website=]|access-date=1 July 2021}}</ref> {{langx|fr|château de Versailles}}<!--Not capitalized in French.--> {{IPA|fr|ʃɑto d(ə) vɛʁsɑj||LL-Q150 (fra)-Jules78120-Versailles.wav}}) is a former royal residence commissioned by King ] located in ], about {{convert|18|km}} west of ], in the ] of ] in ]. | |||

| In ], it is known as the '''Château de Versailles'''. When the château was built, Versailles was a country village; today, however, it is a suburb of ]. From 1682, when ] moved from Paris, until ] was forced to return to the capital in 1789, the '''Court of Versailles''' was the centre of power in ] France. Versailles is therefore famous not only as a building, but as a symbol of the system of ] which Louis XIV espoused. | |||

| The palace is owned by the government of France and since 1995 has been managed, under the direction of the ], by the ].<ref>{{cite web |title=The Public Establishment |url=https://en.chateauversailles.fr/public-establishment#our-missions |website=Palace of Versailles |date=31 October 2016 |access-date=20 December 2021}}</ref> About 15,000,000 people visit the palace, park, or ] every year, making it one of the most popular tourist attractions in the world.<ref>{{cite web|title=Palace of Versailles (Château de Versailles)|url=https://us.france.fr/en/paris/article/palace-versailles-chateau-versailles|work=Explore France|publisher=Government of France|date=18 June 2021|access-date=3 August 2021|archive-date=18 December 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221218123944/https://us.france.fr/en/paris/article/palace-versailles-chateau-versailles|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ==Origins and the first château: Louis XIII== | |||

| The earliest mention of the village of Versailles is found in a document dated 1142, the “Charte de l'abbaye Saint-Père de Chartres” (Charter of the Abbey of Saint-Père de Chartres). <ref>(Guérard, 1840)</ref> Of the signatories of the charter was one Hugo de Versailles, hence the name of the village. During this period, the village of Versailles centered on a small castle and church and the area was controlled by a local lord. The village's location on the road from Paris to Dreux and Normandy brought some prosperity to the village but following the Black Plague and the Hundred Years War, the village was largely destroyed and its population severely diminished. | |||

| ] built a hunting lodge at Versailles in 1623. His successor, Louis XIV expanded the château into a palace that went through several expansions in phases from 1661 to 1715. It was a favourite residence for both kings, and in 1682, Louis XIV moved the seat of his court and government to Versailles, making the palace the '']'' capital of France. This state of affairs was continued by Kings ] and ], who primarily made interior alterations to the palace, but in 1789 the royal family and French court returned to Paris. For the rest of the ], the Palace of Versailles was largely abandoned and emptied of its contents, and the population of the surrounding city plummeted. | |||

| In 1575, ], a Florentine, purchased the seigneury of Versailles. Gondi had arrived in France with ] and his family became influential in the French Parliament. In the early decades of the 17th century, Gondi invited Louis XIII on several hunting trips in the forests of Versailles. Following this initial introduction to the area, Louis XIII ordered the construction of a hunting chateau in 1624. Designed by ], the structure was constructed of stone and red brick with a slate roof. Eight years later, in 1632, Louis obtained the seigneury of Versailles from the Gondi family and began to make enlargements to the château. <ref>(Bluche, 1991); (Marie, 1968); (Nolhac, 1901); (Verlet, 1968)</ref> | |||

| ], following ], used the subsidiary palace, ], as a summer residence from 1810 to 1814, but did not use the main palace. Following the ], when the king was returned to the throne, he resided in Paris and it was not until the 1830s that meaningful repairs were made to the palace. A ] was installed within it, replacing the courtiers apartments of the southern wing. | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| * Bluche, François. ''Dictionnaire du Grand Siècle''. Paris: Arthème Fayard, 1991. | |||

| * Guérard, Benjamin éd. ''Cartulaire de l'abbaye de Saint-Père de Chartres''. Paris, 1840. | |||

| * Marie, Alfred. ''Naissance de Versailles''. Paris: Edition Vincent, Freal & Cie, 1968. | |||

| * Nolhac, Pierre de. ''La création de Versailles''. Versailles: L. Bernard, 1901. | |||

| * Verlet, Pierre. ''Versailles''. Paris: Arthème Fayard, 1961. | |||

| The palace and park were designated a ] by ] in 1979 for its importance as the centre of power, art, and science in France during the 17th and 18th centuries.<ref name = "unesco">{{cite web |url = http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/83 |title = Palace and Park of Versailles |website = UNESCO World Heritage Centre |publisher = United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |access-date = 9 October 2021}}</ref> The French Ministry of Culture has placed the palace, its gardens, and some of its ] on its ]. | |||

| ==Expansion under the rule of Louis XIV== | |||

| Louis' successor, ], had a great interest in Versailles. He had grown up in the disorders of the civil war between rival factions of aristocrats called the ], and wanted a site where he could organize and completely control a ] by absolute ]. He settled on the royal ] at Versailles, and over the following decades had it expanded into one of the largest palaces in the world. | |||

| Beginning in 1669, the architect, ], and the ], ], began a detailed renovation of the château. It was Louis XIV's hope to create a center for the royal court. Following the ] in 1678, the court and French government began to be moved to Versailles. The court was officially established there on ] ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| By moving the royal court and the seat of the French government, Louis XIV hoped to gain greater control of the government from the nobility, and to distance himself from the population of Paris. All the power of France emanated from this centre: there were government offices here, as well as the homes of thousands of courtiers, their retinues, and all the attendant functionaries of court. By requiring that nobles of a certain rank and position spend time each year at Versailles, Louis prevented them from developing their own ] at the expense of his own and kept them from countering his efforts to centralize the French government in an absolute monarchy. The meticulous and strict court etiquette that Louis XIV established, which overwhelmed his heirs with its petty boredoms, was epitomized in the elaborate procedures accompanying his rising in the morning, known as the '']'', divided into a ''petit lever'' for the most important and a ''grand lever'' for the whole court. Like other French court manners, "etiquette" was quickly imitated in other European courts. | |||

| {{Main article|History of the Palace of Versailles}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Evolution of Versailles== | |||

| Upon the death of Jules Cardinal ] in 1661, who had served as ] during the minority of Louis XIV, Louis XIV (b. 5 September 1638 at ]; d. 1 September 1715 at Versailles; reigned 14 May 1642 – 1 September 1715) began his personal reign by vowing to be his own prime minister. From this point, construction and expansion at Versailles became synonymous with the ] of Louis XIV. | |||

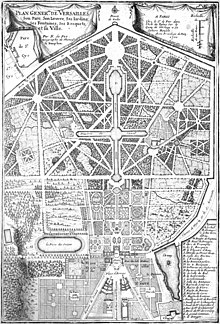

| In 1623,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=2}}{{sfn|Ayers|2004|p=333}} ], ], built a ] on a hill in a favourite hunting ground, {{convert|12|mi|order=flip}} west of ],{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=1–2}} and {{convert|10|mi|order=flip}} from his primary residence, the ].{{sfn|Hoog|1996|p=369}} The site, near a village named Versailles,{{efn|The name "Versailles", first used in 1038,{{sfn|City of Versailles: History}} from the Old French word ''versail'',{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=12}} comes from the Latin word ''vertere'';{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=1}} both mean "ploughed field".{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=12}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=1}}}} was a wooded wetland that Louis XIII's court scorned as being generally unworthy of a king;{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=15}} one of his courtiers, ], wrote that the lodge "would not inspire vanity in even the simplest gentleman".{{sfn|Ayers|2004|p=333}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=53}} From 1631 to 1634, architect ] replaced the lodge with a ] for Louis XIII,{{sfn|Jones|2018|pp=15–16}}{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=53}} who forbade his queen, ], from staying there overnight,{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=16}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=3}} even when an outbreak of ] at ] in 1641 forced Louis XIII to relocate to Versailles with his three-year-old heir, the future ].{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=16}}{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: History}} | |||

| The idea of Versailles was originally started when Louis XIV wanted to ensure that all of his advisors and the rulers of each region would be kept close to him. He feared that they would rise up against and start a revolt, which eventually happened anyway. He thought that if he kept all of his potential over-throwers near him, that they would be powerless and would not be able to attack because they would have to attack themselves to attack him. After the disgrace of ] in 1661 — Louis claimed the ] would not have been able to build his grand château at ] without having embezzled from the crown — Louis XIV, after confiscation of Fouquet’s estate, employed the talents of architect ], landscape architect ], and painter/decorator ] for his building campaigns at Versailles and elsewhere. For Versailles, there were four distinct building campaigns (after minor alterations and enlargements had been executed on the château and the gardens in 1662-1663), all of which corresponded to Louis XIV’s wars. | |||

| When Louis XIII died in 1643, Anne became Louis XIV's ],{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|p=58}} and Louis XIII's château was abandoned for the next decade. She moved the court back to Paris,{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=17}} where Anne and her ], ], continued Louis XIII's unpopular monetary practices. This led to ], a series of revolts against royal authority from 1648 to 1653 that masked a struggle between Mazarin and the ], Louis XIV's extended family, for influence over him.{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|pp=58, 60, 66}} In the aftermath of the Fronde, Louis XIV became determined to rule alone.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=26}}{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|p=66}} Following Mazarin's death in 1661,{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=18}} Louis XIV reformed his government to exclude his mother and the princes of the blood,{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|p=66}} moved the court back to Saint-Germain-en-Laye,{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=25}} and ordered the expansion of his father's château at Versailles into a palace.{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=16}}{{sfn|Hoog|1996|pp=369–70}} | |||

| ===1st building campaign=== | |||

| ]The First Building Campaign (1664-1668) commenced with the ] of 1664, a party that was held between 7th and 13th May 1664. The party was ostensibly given to celebrate the two queens of France — ], the ] and ], Louis XIV’s wife, but in reality celebrated the king’s mistress, ]. The fête of the Plaisirs de l’Île enchantée is often regarded as a prelude to the ], which Louis XIV waged against Spain — both the Queen Mother and Marie-Thérèse were Spanish by birth — from 1667 to 1668). The First Building Campaign (1664-1668) saw alterations in the château and gardens in order to accommodate the 600 guests invited to the party. | |||

| Louis XIV had hunted at Versailles in the 1650s,{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=53}}{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: History}} but did not take any special interest in Versailles until 1661.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=4–5}} On 17 August 1661,{{sfn|Bonney|2007|p=223}} Louis XIV was a guest at a sumptuous festival hosted by ], the ], at his palatial residence, the ].{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=18}}{{sfn|Blanning|2002|p=33}} Louis XIV was impressed by the château and its gardens,{{sfn|Blanning|2002|p=33}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=19}} which were the work of ], the ] since 1654, ], the royal gardener since 1657, and ],{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=53}} a painter in royal service since 1647.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Charles Le Brun}} Vaux-le-Vicomte's scale and opulence led him to imprison Fouquet that September, as he had also built an island fortress and a private army.{{sfn|Blanning|2002|p=33}}{{sfn|Berger|1994|pp=18–19}} But Louis XIV was also inspired by Vaux-le-Vicomte,{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=41}} and he recruited its authors for his own projects.{{sfn|Blanning|2002|p=40}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=42}} Louis XIV replaced Fouquet with ],{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|p=66}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=19}} a protégé of Mazarin and enemy of Fouquet,{{sfn|Bonney|2007|pp=208–10}} and charged him with managing the corps of artisans in royal employment.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=5}}{{sfn|Blanning|2002|p=36}} Colbert acted as the intermediary between them and Louis XIV,{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=20}} who personally directed and inspected the planning and construction of Versailles.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=9}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=35}}{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=25}} | |||

| ===2nd building campaign=== | |||

| ===Construction=== | |||

| The Second Building Campaign (1669-1672) was inaugurated with the signing of the ] (the treaty that ended the ]). During this campaign, the château began to assume some of the appearance that it has today. The most important modification of the château was Louis LeVau’s envelope of Louis XIII’s hunting lodge. The envelope — often referred to as the château neuf to distinguish it from the older structure of ] — enclosed the hunting lodge on the north, west, and south. The new structure provided new lodgings for members of the king and his family. The main floor — the piano nobile — of the château neuf was given over entirely to two apartments, one for the king and one for the queen. The ] occupied the northern part of the château neuf and ] occupied the southern part. The western part of the envelope was given over almost entirely to a terrace, which was later destroyed for construction of the Hall of Mirrors (]).] The ground floor of the northern part of the château neuf was occupied by the appartement des bains, which included a sunken octagonal tub with hot and cold running water. The king’s brother and sister-in-law, the duc and duchesse d’Orléans occupied apartments on the ground floor of the southern part of the château neuf. The upper story of the château neuf was reserved for private rooms for the king to the north and rooms for the king’s children above the queen’s apartment to the south. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| |image1=Chateau de Versailles 1668 Pierre Patel.jpg|caption1=Versailles in 1668, painted by ]|alt1=A painting of the Palace and Versailles and its gardens as it appeared in 1668 | |||

| |image2=Chateau de Versailles 1675FXD.jpg|caption2=Le Vau's garden façade around 1675|alt2=A painting of the garden façade built by Louis Le Vau from 1668 to 1670 | |||

| }} | |||

| Work at Versailles was at first concentrated on ],{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=55–63}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=4}} and through the 1660s, Le Vau only added two detached service wings and a forecourt to the château.{{sfn|Ayers|2004|p=334}}{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=54}} But in 1668–69,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=6}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=67}} as a response to the growth of the gardens,{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=62–63, 69}} and victory over Spain in the ],{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=6}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=67}} Louis XIV decided to turn Versailles into a full-scale royal residence.{{sfn|Ayers|2004|p=334}}{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=61}} He vacillated between replacing or incorporating his father's château, but settled on the latter by the end of the decade,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=6}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=67}}{{sfn|Berger|1994|pp=61, 64}} and from 1668 to 1671,{{sfn|Ayers|2004|pp=334–35}} Louis XIII's château was encased on three sides in a feature dubbed the '']''.{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=67}}{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=64}} This gave the château a new, ] façade overlooking the gardens, but preserved the courtyard façade,{{sfn|Hoog|1996|p=370}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=7}} resulting in a mix of styles and materials that dismayed Louis XIV{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=7}} and that Colbert described as a "patchwork".{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=24}} Attempts to homogenize the two façades failed, and in 1670 Le Vau died,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=7–8}} leaving the post of First Architect to the King vacant for the next seven years.{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=22}} | |||

| Significant to the design and construction of the grands appartements is that the rooms of both apartments are of the same configuration and dimensions — a hitherto unprecedented feature in French palace design. In his monograph “Il n’y plus des Pyrenées: the Iconography of the first Versailles of Louis XIV,” Kevin Olin Johnson posited the hypothesis that the unprecedented similarity to the king and queen’s apartments represented Louis XIV’s wish to establish his wife as queen of Spain. In doing so, a ] of sorts would have been created. Louis XIV’s rationale for the joining of the two kingdoms was seen largely as recompense for ]'s failure to pay his daughter Marie-Thérèse’s dowry, which was among the terms of capitulation to which Spain agreed with the promulgation of the ] (1659, ending the war between Spain and France that had been waged since 1635). Louis XIV regarded his father-in-law’s act as a breach of the treaty and consequently engaged in the War of Devolution. | |||

| Le Vau was succeeded at Versailles by his assistant, architect ].{{sfn|Berger|1985|p=22}} Work at the palace during the 1670s focused on its interiors, as the palace was then nearing completion,{{sfn|Hoog|1996|p=370}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=91}} though d'Orbay expanded Le Vau's service wings and connected them to the château,{{sfn|Hoog|1996|p=370}} and built a pair of pavilions for government employees in the forecourt.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: History}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=22}} In 1670, d'Orbay was tasked by Louis XIV with designing a city, also called ],{{sfn|City of Versailles: History}} to house and service Louis XIV's growing government and court.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=7–8}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=38}} The granting of land to courtiers for the construction of ] that resembled the palace began in 1671.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=7–8}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|pp=27–28}} The next year, the ] began and funding for Versailles was cut until 1674,{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=50–51}} when Louis XIV had work begun on the {{ill|Ambassadors' Staircase|fr|Escalier des Ambassadeurs}}, a grand staircase for the reception of guests, and demolished the last of the village of Versailles.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=9, 11}} | |||

| Both the grand appartement du roi and the grand appartement de la reine formed a suite of seven ] rooms. Each room is dedicated to one of the then-known ] and is personified by the appropriate ] deity. The decoration of the rooms, which was conducted under the direction of the ], depicted the “heroic actions of the king” and were represented in allegorical form by the actions of historical figures from the antique past (], Augustus, Cyrus, etc.). | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ===3rd building campaign=== | |||

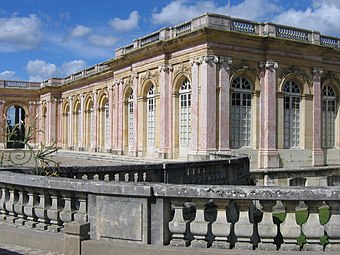

| Following the end of the Franco-Dutch War with French victory in 1678, Louis XIV appointed as First Architect ],{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=25}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=93}} an experienced architect in Louis XIV's confidence,{{sfn|Berger|1994|pp=86–87, 113}} who would benefit from a restored budget and large workforce of former soldiers.{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=50–51}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=18}} Mansart began his tenure with the addition from 1678 to 1681 of the ],{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=115}} a renovation of the courtyard façade of Louis XIII's château,{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=35}} and the expansion of d'Orbay's pavilions to create the ] in 1678–79.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Capital}} Adjacent to the palace, Hardouin-Mansart built a pair of ] called the ] and ] from 1679 to 1682{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=114}}{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Royal Stables}} and the {{ill|Grand Commun|fr}}, which housed the palace's servants and general kitchens, from 1682 to 1684.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Grand Commun}} Hardouin-Mansart also added two entirely new wings in Le Vau's Italianate style to house the court,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=10–11}} first at the south end of the palace from 1679 to 1681{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=43}} and then at its north end from 1685 to 1689.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: History}} | |||

| War and the resulting diminished funding slowed construction at Versailles for the rest of the 17th century.{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=50–51}} The ], which began in 1688, stopped work altogether until 1698.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=18}} Three years later, however, the even more expensive ] began and,{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=51}} combined with poor harvests in 1693–94 and 1709–10,{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=52}}{{sfn|Doyle|2001|p=190}} plunged France into crisis.{{sfn|Doyle|2001|p=190}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=51–52}} Louis XIV thus slashed funding and cancelled some of the work Hardouin-Mansart had planned in the 1680s, such as the remodelling of the courtyard façade in the Italianate style. Louis XIV and Hardouin-Mansart focused on a permanent ],{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=50–51}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=17–19}} the construction of which lasted from 1699 to 1710.{{sfn|Hoog|1996|p=370}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=53}} | |||

| ] With the signing of the ] (1678, which ended the ] of 1672-1678), the Third Building Campaign at Versailles began (1678-1684). Under the direction of the architect, ], the Palace of Versailles acquired much of the look that it has today. In addition to the Hall of Mirrors, Mansart designed the north and south wings (which were used by the nobility and Princes of the Blood, respectively), and the Orangerie. Charles Le Brun was occupied not only with the ] of the new additions of the palace, but also collaborated with André Le Notre in landscaping the palace gardens. As symbol of France’s new prominence as a European ], Louis XIV officially installed his court at Versailles in May of 1682. | |||

| ] (1745) by ]]] | |||

| ===4th building campaign=== | |||

| Louis XIV's successors, ] and ], largely left Versailles as they inherited it and focused on the palace's interiors. Louis XV's modifications began in the 1730s, with the completion of the ], a ] in the north wing, and the expansion of the ],{{Sfn|Jones|2018|p=59–60, 65}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=20–21}} which required the demolition of the Ambassadors' Staircase.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=9}} In 1748, Louis XV began construction of a palace theatre, the ] at the northernmost end of the palace,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=21}}{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Royal Opera}} but completion was delayed until 1770;{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Royal Opera}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=61}} construction was interrupted in the 1740s by the ] and then again in 1756 with the start of the ].{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=21}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=61}} These wars emptied the royal treasury<!--Spawforth p21--> and thereafter construction was mostly funded by ], Louis XV's favourite mistress.<!--{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=21, 23}}--> In 1771, Louis XV had the northern Ministers' Wing rebuilt in Neoclassical style by ], his court architect, as it was in the process of falling down. That work was also stopped by financial constraints,<!--{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=22–23}} and it was not completed until 1780.{{cn|date=September 2021}}--> and it remained incomplete when Louis XV died in 1774. In 1784, Louis XVI briefly moved the royal family to the ] ahead of more renovations to the Palace of Versailles, but construction could not begin because of financial difficulty and ].{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=21–24}} In 1789, the ] swept the royal family and government out of Versailles forever.{{sfn|Hoog|1996|p=370}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=24}} | |||

| ]Soon after the crushing defeat of the ] (1688-1697) and owing possibly to the pious influence of ], Louis XIV undertook his last building campaign at Versailles. The fourth building campaign (1699-1710) concentrated almost exclusively on construction of the Chapel Royal, designed by Mansart and finished by ] and his team of decorative designers. There were also some modifications in the king’s Petit Appartement, namely the construction of the ] and the King’s Bedchamber. With the completion of the chapel in 1710, virtually all construction at Versailles ceased; building would not be resumed at Versailles until some 20 years later during the reign of ]. | |||

| ===Role in politics and culture=== | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| ]'', painted by ]]] | |||

| *], ''Description sommaire du chasteau de Versailles'', (Paris, 1674) | |||

| *Pierre de Nolhac, ''La création de Versailles'', (Versailles, 1901). | |||

| *Pierre de Nolhac, ''Versailles, résidence de Louis XIV'', (Paris, 1925). | |||

| *Pierre de Nolhac, ''Histoire de Versailles''. 3 vol. (Paris, 1911). | |||

| *Kevin Olin Johnson, “Il n’y plus de Pyrenées : Iconography of the first Versailles of Louis XIV,” ''Gazette des Beaux-Arts'' (6e pér., vol. 97, janvier 1981) : 29-40. | |||

| The Palace of Versailles was key to Louis XIV's politics, as an expression and concentration of ] and ], and for the centralization of royal power.{{sfn|Blanning|2002|pp=33–40}}{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|pp=61–64}} Louis XIV first used Versailles to promote himself with a series of nighttime festivals in its gardens in 1664, 1668, and 1674,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=4–5}} the events of which were disseminated throughout Europe by print and engravings.{{sfn|Blanning|2002|p=49}}{{sfn|Walton|1986|pp=57, 59}} As early as 1669,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=6}} but especially from 1678,{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=26}} Louis XIV sought to make Versailles his seat of government, and he expanded the palace so as to fit the court within it.{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|p=62}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=42}}{{sfn|Doyle|2001|p=173}} The moving of the court to Versailles did not come until 1682,{{sfn|Doyle|2001|p=173}} however, and not officially, as opinion on Versailles was mixed among the ].{{sfn|Walton|1986|p=53}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=14}} | |||

| ==Features of the Palace of Versailles== | |||

| By 1687, however, it was evident to all that Versailles was the '']'' capital of France,{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Capital}}{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=15}} and Louis XIV succeeded in attracting the nobility to Versailles to pursue prestige and royal patronage within a strict court etiquette,{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|pp=61–64}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=42}}{{sfn|Blanning|2002|pp=31–34, 40}}{{efn|At any given moment during Louis XIV's reign, about 5% of France's nobles were at court in Versailles. Bohanan places the exact number of persons normally present at Versailles as 5,000 nobles and an equal number of commoners,{{sfn|Bohanan|2001|pp=62, 64}} while Blanning gives 1,000 nobles and 4,000 servants.{{sfn|Blanning|2002|p=36}}}} thus eroding their traditional provincial power bases.{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=42}}{{sfn|Doyle|2001|p=173}}{{sfn|Swann|2001|pp=143, 145}} It was at the Palace of Versailles that Louis XIV received the ], ] in 1685,{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Reception of the Doge of Genoa}} ] from the ] in 1686,{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Reception of the Ambassador of Siam}} and ] from ] in 1715.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Reception of the Ambassadors of Persia}} | |||

| ===Grands Appartements=== | |||

| Louis XIV died at Versailles on 1 September 1715 and was succeeded by his five-year-old great-grandson, ],{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=52}}{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Death of Louis XIV}} then the ],{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=57}} who was moved to the ] and then to Paris by Louis XV's regent, ].{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Death of Louis XIV}} Versailles was neglected until 1722,{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: History}} when Philippe II removed the court to Versailles to escape the unpopularity of his regency,{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=20}}{{sfn|Jones|2018|p=58}} and when Louis XV began his majority.{{sfn|Swann|2001|p=201}} The 1715 move, however, broke the cultural power of Versailles,{{sfn|Doyle|2001|p=91}} and during the reign of ], courtiers spent their leisure in Paris, not Versailles.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: History}} | |||

| As a result of ]’s envelope of Louis XIII’s château, the king and queen had new apartments in the new addition, known at the time as the château neuf. The State Apartments – Grands Appartements, which are known respectively as the grand appartement du roi and the grand appartement de la reine, occupied the main or principal floor of the château neuf. LeVau’s design for the state apartments closely followed Italian models of the day, as evidenced by the placement of the apartments on the next floor up from the ground level — the piano nobile — a convention the architect borrowed from 16th and 17th century Italian palace design. | |||

| ] during his stay at the palace]] | |||

| ====Grand Appartement du roi==== | |||

| During Christmas 1763, ] Versailles and dined with the King. The 7-year-old ] played several works during his stay and later dedicated his first two harpsichord sonatas, published in 1764 in Paris, to ], daughter of Louis XV.<ref>{{cite web |title=Visit from the child Mozart (1763-1764) |url=https://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/key-dates/visit-child-mozart-1763-1764 |website=The Palace of Versailles |date=23 August 2018 |access-date=10 July 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Le Vau’s plan called for an enfilade of seven rooms, each dedicated to one of the then-known planets and their associated titular Roman deity. LeVau’s plan was bold as he designed a heliocentric system that centered on the salon d’Apollon (Salon of Apollo).] The salon d’Apollon originally was designed as the king’s bedchamber, but served as a ].<ref>During the reign of Louis XIV (until 1689), a solid silver throne stood on a ] covered dais on the south wall of this room.</ref> The original arrangement of the enfilade of rooms was thus: | |||

| In 1783, the palace was the site of the signing of the last two of the three treaties of the ], which ended the ]. On 3 September, British and American delegates, led by ], signed the ] at the Hôtel d'York (now 56 Rue Jacob) in Paris, granting the United States independence. On 4 September, Spain and France signed separate treaties with Britain at the Palace of Versailles, formally ending the war.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.constitutionfacts.com/us-declaration-of-independence/treaty-of-paris/|title=The Treaty of Paris|website=www.constitutionfacts.com}}</ref> | |||

| * ] (Diana, Roman goddess of the hunt; associated with the Moon)<ref>This room originally served as the west landing of the Ambassadors’ Staircase and formed the main entrance to the grand appartement du roi.</ref> | |||

| * ] (Mars, Roman god of war; associated with the ]) | |||

| * ] (Mercury, Roman god of trade, commerce, and the Liberal Arts; associated with the ]) | |||

| * ] (Apollo, Roman god of the Fine Arts; associated with the Sun) | |||

| * ] (Jupiter, Roman god of law and order; associated with the ]) | |||

| * ] (Saturn, Roman god of agriculture and harvest; associated with the planet Saturn) | |||

| * ] (Venus, ]; associated with the ]) | |||

| The King and Queen learned of the ] in Paris on 14 July 1789, while they were at the palace, and remained isolated there as the ] in Paris spread. The growing anger in Paris led to the ] on 5 October 1789. A crowd of several thousand men and women, protesting the high price and scarcity of bread, marched from the markets of Paris to Versailles. They took weapons from the city armoury, besieged the palace, and compelled the King and royal family and the members of the ] to return with them to Paris the following day.{{Sfn|Lacaille|2012|pp=16–17}} | |||

| The configuration of the grand appartement du roi conformed to contemporary conventions in palace design.<ref>Baillie, Hugh Murray. "Etiquette and the Planning of State Apartments in Baroque Palaces," Archeologia CI (1967): 169-199.</ref> However, owing to Louis XIV’s personal tastes<ref> and with the apartment’s northern exposure, Louis XIV found the rooms too cold and opted to live in the rooms previously occupied by his father.</ref> the grand appartement du roi was reserved for court functions — such as the thrice-weekly appartement evenings given by Louis XIV. | |||

| As soon as the royal family departed, the palace was closed. In 1792, the ], the new revolutionary government, ordered the transfer of all the paintings and sculptures from the palace to the ]. In 1793, the Convention declared the abolition of the monarchy and ordered all of the royal property in the palace to be sold at auction. The auction took place between 25 August 1793 and 11 August 1794. The furnishings and art of the palace, including the furniture, mirrors, baths, and kitchen equipment, were sold in seventeen thousand lots. All fleurs-de-lys and royal emblems on the buildings were chambered or chiselled off. The empty buildings were turned into a storehouse for furnishings, art and libraries confiscated from the nobility. The empty grand apartments were opened for tours beginning in 1793, and a small museum of French paintings and art school was opened in some of the empty rooms.{{Sfn|Lacaille|2012|p=18}} | |||

| The rooms were decorated by ] and demonstrated Italian influences (LeBrun met and studied with the famed Tuscan artist ], whose decorative style of the ] in Florence LeBrun adapted for use at Versailles). The quadratura style of the ceilings evoke Cortona’s ''Sale dei Planeti'' at the Pitti, but LeBrun’s decorative schema is more complex. In his 1674 publication about the grand appartement du roi, André Félibien described the scenes depicted in the coves of the ceilings of the rooms as allegories depicting the “heroic actions of the king.”<ref>André Félibien, Description sommaire du chasteau de Versailles, (Paris, 1674).</ref> Accordingly, one finds scenes of the exploits of Augustus, Alexander the Great, and Cyrus alluding to the deeds of Louis XIV. For example, in the salon d’Apollon, the cove painting “Augustus building the port of Misenum”<ref>Located in the western cove of the ] and painted by ] ca. 1674.</ref> alludes to the construction of the port at ]; or, depicted in the south cove of the salon de Mercure], was offered to Louis XIV in 1706. It is the only piece of furniture from the Grand Appartement that has survived, however the original ] marquetry case has been replaced.]] is “Ptolemy II Philadelphus in his Library”, which alludes to Ptolemy’s construction of the ] and which accordingly serves as an allegory to Louis XIV’s expansion of the Bibliothèque du roi.<ref>Located in the southern cove of the ceiling of the salon de Mercure and painted by Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne ca. 1674.</ref><ref>For a more detailed discussion regarding the ceiling decor of the grand appartement du roi, see Gérard Sabatier, “Versailles, ou la figure du roi,” (Paris: Albin Michel, 1999). For an analysis of the symbolism in the decor of the grand appartement du roi, see Edward Lighthart, “Archétype et symbole dans le style Louis XIV versaillais: réflexions sur l’imago rex et l’imago patriae au début de l’époque moderne,” (Doctoral thesis, 1997).</ref> Complementing the rooms’ decors were pieces of massive silver furniture. Regrettably, owing to the War of the League of Augsburg, in 1689 Louis XIV ordered all of this silver furniture to be sent to the mint, to be melted down to help defray the cost of the war. | |||

| By virtue of an order issued by the Versailles district directorate in August 1794, the ] was destroyed, the Cour Royale was cleared and the Cour de Marbre lost its precious floor.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Heitzmann |first1=Annick |last2=Didier |first2=Frédéric |title=La Grille et la Cour royales |journal=Versalia. Revue de la Société des Amis de Versailles |date=2007 |volume=10 |pages=26–43 |doi=10.3406/versa.2007.871 |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/versa_1285-8412_2007_num_10_1_871 |access-date=7 June 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Maral |first1=Alexandre |title=Octobre 1789: Versailles déserté |date=24 October 2018 |url=http://www.lescarnetsdeversailles.fr/2018/10/octobre-1789-versailles-deserte/ |access-date=7 June 2023}}</ref> | |||

| LeVau’s original plan for the grand appartement du roi was short-lived. With the inauguration of the 2nd building campaign, which suppressed the terrace linking the king and queen’s apartments and the salons of Jupiter, Saturn and Venus for the construction of the ], the configuration of the grand appartement du roi was altered. The decor of the salon de Jupiter was removed and reused in the decoration of the salle des gardes de la reine; and elements of the decoration of the first salon de Vénus, which opened onto the terrace, were reused in the salon de Vénus that we see today.<ref>Originally, the room that is known today as the salon de Vénus formed part of the apartment of the king’s mistress, ]. Owing to her involvement with ], during which time its was alleged she had been giving the king love potions, she fell from grace in 1678 and her apartments were taken over by Louis XIV at which time the new salon de Vénus was installed.</ref> | |||

| === 19th century – history museum and government venue === | |||

| From 1678 to the end of Louis XIV’s reign, the grand appartement du roi served as the venue for the king’s thrice-weekly evening receptions, known as les soirées de l’appartement. For these parties, the rooms assumed specific functions: | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] in the ], August 1855 by ]]] | |||

| ], 18 January 1871'', 1877 by ]]] | |||

| When ] became Emperor of the French in 1804, he considered making Versailles his residence but abandoned the idea because of the cost of the renovation. Prior to his marriage with ] in 1810, he had the ] restored and refurnished as a springtime residence for himself and his family, in the style of furnishing that it is seen today.{{Sfn|Lacaille|2012|page=19}} | |||

| * ]: buffet tables were arranged to display food and drink for the king’s guests. | |||

| * ]: served as a ]. | |||

| * ]: served as a ballroom. | |||

| * ]: served as a gaming (cards) room. | |||

| * ]: served as a concert or music room. | |||

| * | |||

| In the 18th century during the reign of Louis XV, the grand appartement du roi was expanded to include the Salon de l’Abondance (Hall of Plenty) — formerly the entry vestibule of the ] — and the ] — occupying the tribune level of the former chapel of the château. | |||

| In 1815, with the final downfall of Napoleon, ], the younger brother of Louis XVI, became king, and considered returning the royal residence to Versailles, where he had been born. He ordered the restoration of the royal apartments, but the task and cost was too great. Louis XVIII had the far end of the south wing of the ''Cour Royale'' demolished and rebuilt (1814–1824) to match the Gabriel wing of 1780 opposite, which gave greater uniformity of appearance to the front entrance.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|p=244}} Neither he nor his successor ] lived at Versailles.{{Sfn|Lacaille|2012|page=19}} | |||

| ====Grand Appartement de la reine==== | |||

| Forming a parallel enfilade with that of the grand appartement du roi, the grand appartement de la reine served as the residence of three queens of France — Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche, wife of Louis XIV; Marie Leszczyska, wife of Louis XV; and Marie-Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI (additionally, Louis XIV’s granddaughter-in-law, Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie, as duchesse de Bourgogne, occupied these rooms from 1697 (the year of her marriage) to her death in 1712). ] | |||

| The ] brought a new monarch, ] to power, and a new ambition for Versailles. He did not reside at Versailles but began the creation of the ], dedicated to "all the glories of France", which had been used to house some members of the royal family. The museum was begun in 1833 and inaugurated on 30 June 1837. Its most famous room is the ] (Hall of Battles), which lies on most of the length of the second floor of the south wing.{{sfn|Hoog|1996|pp=369–374}} The museum project largely came to a halt when Louis Philippe was overthrown in 1848, though the paintings of French heroes and great battles still remain in the south wing. | |||

| When Louis Le Vau’s envelope of the château vieux was completed, the grand appartement de la reine came to include a suite of seven enfilade rooms with an arrangement that mirrored almost exactly the grand appartement du roi. The configuration was: | |||

| Emperor ] used the palace on occasion as a stage for grand ceremonies. One of the most lavish was the banquet that he hosted for ] in the ] on 25 August 1855.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/key-dates/visit-queen-victoria-1855|title=Visit of Queen Victoria, 1855|date=22 November 2016|website=Palace of Versailles}}</ref> | |||

| * Chapel — which was pendant with the salon de Diane in the grand appartement du roi<ref>This chapel was the second of chapels built in the château of Versailles</ref> | |||

| * Salle de gardes — which was pendant with the salon de Mars in the grand appartement du roi | |||

| * Antichambre — which was pendant with the salon de Mercure in the grand appartement du roi | |||

| * Chambre — which was pendant with the salon d’Apollon in the grand apartment du roi | |||

| * Grand cabinet — which was pendant with the salon de Jupiter in the grand appartement du roi | |||

| * Oratory — which was pendant with the salon de Saturne in the grand appartement du roi | |||

| * Petit cabinet — which was pendant with the salon de Vénus in the grand appartement du roi<ref>Owing to the construction of the Hall of Mirrors — the central project of Louis XIV’s 3rd building campaign — and the death of Marie-Thérèse in 1683, the grand cabinet, the oratory, and the petit cabinet were destroyed for the construction of the Hall of Mirrors and the Salon de la paix. Of these three rooms, only fragments of the ceiling decoration of the Grand cabinet have survived; no evidence regarding the decoration of the oratory or the petit cabinet has been found. See Nicole Reynaud and Jacques Villain, “Fragments retrouvés de la décoration du Grand Appartement de la Reine Marie-Thérèse,” Revue du Louvre, #4-5 (1970): 231-238.</ref> | |||

| During the ] of 1870–1871, the palace was occupied by the ] of the victorious German Army. Parts of the château, including the Hall of Mirrors, were turned into a military hospital. The creation of the ], combining ] and the surrounding German states under ], was formally ] on 18 January 1871. The Germans remained in the palace until the signing of the armistice in March 1871. In that month, the government of the new ], which had departed Paris during the war for ] and then ], moved into the palace. The ] held its meetings in the Opera House.{{Sfn|Lacaille|2012|page=12}} | |||

| As with the decoration of the ceiling in the grand appartement du roi, which depicted the heroic actions of Louis XIV as allegories from events taken from the antique past, the decoration of the grand appartement de la reine likewise depicted heroines from the antique past and harmonized with the general theme of a particular room’s decor.<ref>On an interesting note, not only were women depicted in the decoration of the grand appartement de la reine, but women contributed to the decoration of these rooms. Most notable of these ladies would be ], who painted the over-door painting in the salle des gardes.</ref> | |||

| The uprising of the ] in March 1871, prevented the French government, under ], from returning immediately to Paris. The military operation which suppressed the Commune at the end of May was directed from Versailles, and the prisoners of the Commune were marched there and put on trial in military courts. In 1875 a second parliamentary body, the ], was created and held its meetings for the election of a President of the Republic in a new hall created in 1876 in the south wing of the palace. The French Senate and National Assembly continue to meet in the palace in ] on special occasions, such as the amendment of the ].{{Sfn|Lacaille|2012|page=20}} | |||

| With the construction of the Hall of Mirrors, which began in 1678, the configuration of the grand appartement de la reine changed. The chapel was transformed into the salle des gardes de la reine and it was in this room that the decorations from the salon de Jupiter were reused.<ref>With the creation of this room, a new chapel — the château’s third — was built in the adjacent room to the east. In 1682, when the third chapel was built (where the salon d’Hercule is now located), this room was renamed la grande salle des gardes de la reine. In the 19th century, this room was rebaptized salle du sacre owing to the installation of Jean-Louis David’s Coronation of Napoléon I.</ref> The salle des gardes de la reine communicates with a loggia that issues from the escalier de la reine, which formed a parallel pendant (albeit a smaller, though similarly-decorated example) with the escalier des ambassadeurs in the grand appartement du roi. The loggia also provides access to the appartement du roi, the suite of rooms in which Louis XIV lived. Toward the end of Louis XIV’s reign, the escalier de la reine became the principal entrance to the château, with the escalier des ambassadeurs used on rare state occasions. After the destruction of the escalier des ambassadeurs in 1752, the escalier de la reine became the main entrance to the château. | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| From 1682, the grand appartement de la reine included: | |||

| ]'' by ]]] | |||

| The end of the 19th and the early 20th century saw the beginning of restoration efforts at the palace, first led by ], poet and scholar and the first conservator, who began his work in 1892. The conservation and restoration were interrupted by two world wars but have continued until the present day.{{Sfn|Lacaille|2012|page=13}} | |||

| * Salle des gardes de la reine | |||

| * Antichambre (formerly the salle des gardes) | |||

| * Grand cabinet | |||

| * Chambre de la reine | |||

| The palace returned to the world stage in June 1919, when, after six months of negotiations, the ], formally ending the First World War, was signed in the ]. Between 1925 and 1928, the American philanthropist and multi-millionaire ] gave $2,166,000, the equivalent of about thirty million dollars today, to restore and refurbish the palace.<ref>Iverson, Jeffrey, ''France Today'', 19 July 2014</ref> | |||

| With the death of Louis XIV in 1715, the court moved to ] and later to Paris. In 1722, Louis XV reinstalled the court at Versailles and began modifications to the château’s interior. Among the most noteworthy of the building projects during Louis XV’s reign, the redecoration of the chamber de la reine must be cited. | |||

| More work took place after World War II, with the restoration of the ]. The theatre was reopened in 1957, in the presence of Queen ] of the United Kingdom.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.versailles3d.com/en/over-the-centuries/xxe/1957.html|title=1957 – XXth century – Over the centuries – Versailles 3d|website=www.versailles3d.com}}</ref> | |||

| To commemorate the birth of his only son and heir, ], in 1729, Louis XV ordered a complete redecoration of the room. Elements of the chamber de la reine as it had been used by Marie-Thérèse and ] were removed and a new, more modern decor was installed.<ref>The decoration of this room was an important expression in French interior design. It heralded the transition from the ] style, which prevailed from the death of Louis XIV through to 1732(with the decoration of the Salon de la princesse at the ]), and the Rococo (or style Louis XV), the style that prevailed for the greater part of the reign of Louis XV.</ref> | |||

| In 1978, parts of the palace were heavily damaged in a ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1978/06/26/archives/versailles-palace-is-damaged-by-bomb-heavy-explosion-wrecks-three.html |title=Versailles Palace Is Damaged By Bomb |work=The New York Times |date=26 June 1978 |access-date=10 April 2020}}</ref> | |||

| During her life at Versailles, ] (1703-1768) lived in the grand apartment de la reine, to which she annexed the salon de la paix to serve as a music room. In 1770, when the Austrian archduchess Marie-Antoinette married the dauphin, later Louis XVI, she took up residence in these rooms. Upon Louis XVI’s ascension to the throne in 1774, Marie-Antoinette ordered major redecoration of the grand appartement de la reine. At this time, the queen’s apartment achieved the arrangement that we see today. | |||

| Starting in the 1950s, when the museum of Versailles was under the directorship of Gérald van der Kemp, the objective was to restore the palace to its state – or as close to it as possible – in 1789 when the royal family left the palace. Among the early projects was the repair of the roof over the Hall of Mirrors; the publicity campaign brought international attention to the plight of post-war Versailles and garnered much foreign money including a grant from the ]. | |||

| * Salle des gardes de la reine — this room remained virtually unchanged by Marie-Antoinette.<ref>It was via this room that the Paris mob, which stormed the château during the night of 6/7 October 1789, gained access to the château. During the mêlée, members of the garde Suisse, which formed part the queen’s bodyguard, were killed in their attempts to protect the queen.</ref> | |||

| * Antichambre — this room was transformed into the antichambre du grand couvert. It was in this room that the king, queen, and members of the royal family dined in public. Occasionally, this room served as a theater for the château. | |||

| * Grand cabinet — this room was transformed into the salon des nobles. Following the tradition established by her predecessor, Marie-Antoinette would hold formal audiences in this room. When not used for formal audiences, the salon des nobles served as an antechamber to the queen’s bedroom. | |||

| * Chambre de la reine — this room was used as the queen’s bedroom, and was of exceptional splendor. On the night of 6/7 October 1789, Marie-Antoinette fled from the Paris mob by escaping through a private corridor that connected her apartment with that of the king. | |||

| One of the more costly endeavours for the museum and the ] has been to repurchase as much of the original furnishings as possible. Consequently, because furniture with a royal provenance – and especially furniture that was made for Versailles – is a highly sought-after commodity on the international market, the museum has spent considerable funds on retrieving much of the palace's original furnishings.<ref>{{harvnb|Kemp|1976|page=135–137}}</ref> | |||

| ====Sources==== | |||

| ===21st century=== | |||

| The following imprints represent current understanding of the Grands appartements at Versailles. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 2003, a new restoration initiative – the "Grand Versailles" project – was started, which began with the replanting of the gardens, which had lost over 10,000 trees during ] on 26 December 1999. One part of the initiative, the restoration of the ], was completed in 2006.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lexpress.fr/mag/arts/dossier/patrimoine/dossier.asp?ida=451314 |last=Leloup |first=Michèle |date=7 September 2006 |title=Versailles en grande toilette |language=fr |work=] |access-date=4 January 2021 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080215140113/http://www.lexpress.fr/mag/arts/dossier/patrimoine/dossier.asp?ida=451314 |archive-date=15 February 2008}}</ref> Another major project was the further restoration of the backstage areas of the ] in 2007 to 2009.{{sfn|Palace of Versailles: Royal Opera}} | |||

| The Palace of Versailles is currently owned by the French state. Its formal title is the ]. Since 1995, it has been run as a Public Establishment, with an independent administration and management supervised by the ].<ref>Site of the Public Establishment of the Chateau of Versailles (en.chateauversailles.fr)</ref> | |||

| '''Primary Monographs''' | |||

| The grounds of the palace hosted the equestrian competition during the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Château de Versailles |url=https://www.paris2024.org/en/venue/chateau-de-versailles/ |access-date=29 July 2022 |website=Paris 2024 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| * Combes, sieur de. ''Explication historique de ce qu'il y a de plus remarquable dans la maison royale de Versailles''. (Paris: C. Nego, 1681.) | |||

| * Félibien, André. ''Description sommaire du chasteau de Versailles''. (Paris, 1674). | |||

| * Félibien, André. ''La descriptioon du château de Versailles, de ses peintures, et des autres ouvrags fait pour le roy''. (Paris: Antoine Vilette, 1694.) | |||

| * Félibien, Jean-François. ''Description sommaire de Versailles ancienne et nouvelle.'' (Paris: A. Chrétien, 1703.) | |||

| * Monicart, Jean-Baptiste de. ''Versailles immortailisé''. (Paris: E. Ganeau, 1720.) | |||

| * Piganiol de la Force, Jean-Aymar. ''Nouvelle description des châteaux et parcs de Versailles et Marly''. (Paris: Chez Florentin de la lune, 1701.) | |||

| ==Architecture and plan== | |||

| '''Modern Research''' | |||

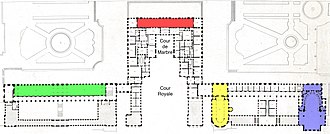

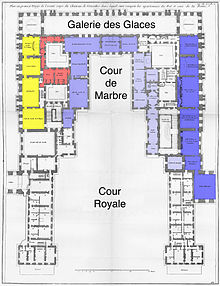

| ] in red, the ] in green, the ] in yellow, and the ] in blue]] | |||

| The Palace of Versailles is a visual history of French architecture from the 1630s to the 1780s. Its earliest portion, the '']'', was built for ] in the ] with brick, marble, and ],{{sfn|Ayers|2004|p=333}} which Le Vau surrounded in the 1660s with ''Enveloppe'', an edifice that was inspired by ] Italian villas.{{sfn|Berger|1985|pp=23–25}} When ] made further expansions to the palace in the 1680s, he used the ''Enveloppe'' as the model for his work.{{sfn|Spawforth|2008|pp=10–11}} ] additions were made to the palace with the remodelling of the ] in the 1770s, by ], and after the ].{{sfn|Jones|2018|pp=61–62, 122}} | |||

| * Batiffol, Louis. “Le château de Versailles de Louis XIII et son architecte Philbert le Roy.“ ''Gazette des Beaux-Arts'' 4 pér., vol. 10 (novembre 1913): 341-371. | |||

| * Batiffol, Louis. “Origine du château de Versailles.“ ''La Revue de Paris'' (avril 1909): 841-869. | |||

| * Berger, Robert W. “The chronology of the Enveloppe of Versailles.“ ''Architectura'' 10 (1980): 105-133. | |||

| * Bottineau, Yves. “Essais sur le Versailles de Louis XIV II: le style et l'iconographie.“ ‘‘Gazette des Beaux-Arts’’ 6 pér., vol. 112 (octobre 1988): 119-132. | |||

| * Brière, Gaston. “Le replacement des peintures décoratives au 'grands appartements' de Versailles.“ ''Bulletin de la société de l'histoire de l'art français'' (1938): 197-216. | |||

| * Constans, Claire. “Les tableaux du Grand Appartement du Roi.“ ''Revue du Louvre'' #3 (1976): 157-173. | |||

| * Gruyer, Paul. “Les plafonds de Versailles.“ ''La Renaissance de l'Art Francais'' (janvier 1920): 250-259. | |||

| * Hoog, Simone. “Les sculptures du Grand Appartement du Roi.“ ''Revue du Louvre'' #3 (1976): 147-156. | |||

| * Josephson, Ragnar. “Relation de la visite de Nicodème Tessin à Marly, Versailles, Rueil, et St-Cloud en 1687.“ ''Revue de l'Histoire de Versailles'' (1926): 150-67, 274-300 | |||

| * Kimball, Fiske. “Genesis of the Château Neuf at Versailles, 1668-1671.“ ''Gazette des Beaux-Arts'' 6 pér., vol. 35 (1949): 353-372. | |||

| * LeGuillou, Jean-Claude. “Aperçu sur un projet insolit (1668) pour le château de Versailles.“ ''Gazette des Beaux-Arts'' 6 pér., vol. 113 (février 1989): 79-104. | |||

| * LeGuillou, Jean-Claude. “Le château-neuf ou enveloppe de Versailles: concept et evolution du premier projet.“ ''Gazette des Beaux-Arts'' 6 pér., vol. 102 (decembre 1983): 193-207. | |||

| * LeGuillou, Jean-Claude. “Remarques sur le corps central du château de Versailles.“ ''Gazette des Beaux-Arts'' 6 pér., vol. 87 (février 1976): 49-60. | |||

| * Lemoine, Pierre. “La chambre de la Reine.“ ''Revue du Louvre'' #3 (1976): 139-145. | |||

| * Lighthart, E. “Archétype et symbole dans le style Louis XIV versaillais: réflexions sur l’imago rex et l’imago patriae au début de l’époque moderne,” (Doctoral thesis, 1997). | |||

| * Marie, Alfred. ''Naissance de Versailles''. (Paris: Edition Vincent, Freal & Cie, 1968.) | |||

| * Marie, Alfred and Jeanne. ''Mansart à Versailles''. (Paris: Editions Jacques Freal, 1972.) | |||

| * Marie, Alfred and Jeanne. ''Versailles au temps de Louis XIV''. (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1976.) | |||

| * Marie, Alfred and Jeanne. ''Versailles au temps de Louis XV''. (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1984.) | |||

| * Mauricheau-Beaupré, Charles. Le château de Versailles. (Paris: D. A. Longuet, 1929.) | |||

| * Mauricheau-Beaupré, Charles. ''Versailles''. (Paris: Draeger et Veive, 1949.) | |||

| * Nolhac, Pierre de. “La construction de Versailles de LeVau.“ ''Revue de l'Histoire de Versailles'' (1899): 161-171. | |||

| * Nolhac, Pierre de. ''La création de Versailles''. (Versailles: L. Bernard, 1901.) | |||

| * Nolhac, Pierre de. ''Versailles, résidence de Louis XIV''. (Paris: L. Conrad, 1925.) | |||

| * Nolhac, Pierre de. ''Versailles au XVIIIe siècle''. (Paris: Louis Conard, 1926.) | |||

| * Reynaud, Nicole et Jacques Vilain. “Fragments retrouvés de la décoration du Grand Appartement de la Reine Marie-Thérèse.“ ''Revue du Louvre'' #4-5 (1970): 231-238. | |||

| * Sabatier, Gérard. “Le parti figuratif dans les appartements, l'escalier et la galerie de Versailles.“ ''XVIIe siècle'' no. 161 (octobre/décember 1988): 401-426. | |||

| * Saule, Beatrix. “Le premier goût du Roi à Versailles: décoration et ameublement.“ ''Gazette des Beaux-Arts'' vol. 120 (octobre 1992): 137-148. | |||

| * Verlet, Pierre. ''Le château de Versailles''. (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1985.) | |||

| * Verlet, Pierre. ''Versailles''. (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1961.) | |||

| * Walton, Guy. “'L'Envelope' de Versailles: refelxcions nouvelles de dessins indedits.“ ''Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de l'Art français''. (1977): 127-144. | |||

| The palace was largely completed by the death of Louis XIV in 1715. The eastern facing palace has a U-shaped layout, with the corps de logis and symmetrical advancing secondary wings terminating with the Dufour Pavilion on the south and the Gabriel Pavilion to the north, creating an expansive ] known as the Royal Court (Cour Royale). Flanking the Royal Court are two enormous asymmetrical wings that result in a façade of {{convert|402|m|ft}} in length.<ref>{{cite news|title=History of Art|newspaper=Visual Arts Cork|url=http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/versailles-palace.htm|access-date=10 August 2016}}</ref> Covered by around {{convert|10|ha|e6sqft|abbr=off}} of roof, the palace has 2,143 windows, 1,252 chimneys, and 67 staircases.<ref>Ayers 2004, also includes 700 rooms. {{p.|333}}.</ref> | |||

| ===Appartement du roi (King's Private Apartments)=== | |||

| The palace and its grounds have had a great influence on architecture and horticulture from the mid-17th century to the end of the 18th century. Examples of works influenced by Versailles include ]'s work at ], ], the ], ],{{sfn|UNESCO: Palace and Park of Versailles}} ], ], ],{{sfn|Kaufmann|1995|pp=320–22}} ], ],{{sfn|UNESCO: Palace and Park of Versailles}}{{sfn|Kaufmann|1995|pp=323–24}} and ].{{sfn|Kaufmann|1995|p=338}} | |||

| {{main article|Appartement du roi}} | |||

| ==Royal Apartments== | |||

| ===Le petit appartement du Roi; l’appartement interieur du roi=== | |||

| (dates Blondel's plan to c. 1742).</ref> showing the '']'' in dark blue, the '']'' in medium blue, the '']'' in light blue, the '']'' in yellow, and the '']'' in red]] | |||

| {{main article|Petit appartement du roi}} | |||

| The construction in 1668–1671 of ]'s ''enveloppe'' around the outside of ]'s red brick and white stone château added state apartments for the king and the queen. The addition was known at the time as the ''château neuf'' (new château). The ''grands appartements'' (Grand Apartments, also referred to as the State Apartments{{sfn|Saule|Meyer|2000|p=18, 22}}<ref>Michelin Tyre 1989, p. 182.</ref>) include the '']'' and the '']''. They occupied the main or principal floor of the ''château neuf'', with three rooms in each apartment facing the garden to the west and four facing the garden parterres to the north and south, respectively. The private apartments of the king (the '']'' and the '']'') and those of the queen (the '']'') remained in the ''château vieux'' (old château). Le Vau's design for the state apartments closely followed Italian models of the day, including the placement of the apartments on the main floor (the '']'', the next floor up from the ground level), a convention the architect borrowed from Italian palace design.<ref>{{harvnb|Berger|1985|p=24–25}}; {{harvnb|Ayers|2004|pg=335}}</ref> | |||

| ===Le petit appartement de la reine=== | |||

| The king's State Apartment consisted of an ] of seven rooms, each dedicated to one of the known ] and their associated titular ]. The queen's apartment formed a parallel enfilade with that of the ''grand appartement du roi''. After the addition of the ] (1678–1684) the king's apartment was reduced to five rooms (until the reign of ], when two more rooms were added) and the queen's to four. | |||

| {{main article|Petit appartement de la reine}} | |||

| The queen's apartments served as the residence of three queens of France – ], wife of ], ], wife of Louis XV, and ], wife of ]. Additionally, Louis XIV's granddaughter-in-law, ], duchess of Burgundy, wife of ], occupied these rooms from 1697 (the year of her marriage) to her death in 1712.<ref group=lower-alpha>Six kings were born in this room: ], Louis XV, Louis XVI, ], ], and ].</ref> | |||

| ===Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors)=== | |||

| {{main article|Galerie des Glaces}} | |||

| === |

===Ambassador's Staircase=== | ||

| ] | |||

| {{main article|Chapels of Versailles}} | |||

| The {{ill|Ambassadors' Staircase|fr|Escalier des Ambassadeurs}} (''Escalier des Ambassadeurs'') was an ] built from 1674 to 1680 by ]. Until Louis XV had it demolished in 1752 to create a courtyard for his private apartments,{{sfn|Berger|1985|p=32}} the staircase was the primary entrance into the Palace of Versailles and the royal apartments especially.{{sfn|Yerkes|2015|p=51}} It was entered from the ] via a ] that, cramped and dark, contrasted greatly with the tall, open space of the staircase – famously lit naturally with a ] – so as to overawe visitors.{{sfn|Berger|1985|pp=32–33}}{{sfn|Yerkes|2015|pp=67, 69}} | |||

| ===L’Opéra=== | |||

| {{main article|l'Opéra of the Palace of Versailles}} | |||

| The staircase and walls of the room that contained it were clad in ] marble and ] bronze,{{sfn|Versailles 3D: 1752}} with decor in the Ionic order.{{sfn|Yerkes|2015|p=72}} ] painted the walls and ceiling of the room according to a festive theme to celebrate Louis XIV's victory in the ].{{sfn|Berger|1985|pp=32–36}} On the wall immediately above the staircase were '']'' paintings of people from the ] looking into the staircase over a balustrade, a motif repeated on the ceiling fresco.{{sfn|Yerkes|2015|pp=72–73}}{{sfn|Berger|1985|p=36}} There they were joined by allegorical figures for the twelve months of the year and various Classical Greek figures such as the ].{{sfn|Berger|1985|pp=35–36}} A marble bust of Louis XIV, sculpted by ] in 1665–66,{{sfn|Berger|1994|p=7}} was placed in a ] above the first landing of the staircase.{{sfn|Versailles 3D: 1752}} | |||

| ==Gardens of Versailles== | |||

| ===The State Apartments of the King=== | |||

| {{mainarticle|Gardens of Versailles}} | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="170"> | |||

| File:Paolo Veronese - Le Repas chez Simon le Pharisien - Google Art Project.jpg|''Meal at the House of Simon the Pharisee'' by ] in the ] | |||

| File:France-000333 - Abundance Salon (14825986264).jpg|Salon of Abundance | |||

| File:Salon de Vénus.jpg|Salon of Venus | |||

| File:Salon de Mercure, Versailles.jpg|Salon of Mercury | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| The construction of the Hall of Mirrors between 1678 and 1686 coincided with a major alteration to the State Apartments. They were originally intended as his residence, but the King transformed them into galleries for his finest paintings, and venues for his many receptions for courtiers. During the season from ] in November until ], these were usually held three times a week, from six to ten in the evening, with various entertainments.{{Sfn|Saule|2013|page=20}} | |||

| ==Subsidiary structures== | |||

| ====The Salon of Hercules==== | |||

| {{mainarticle|Subsidiary structures of the Palace of Versailles}} | |||

| This was originally a chapel. It was rebuilt beginning in 1712 under the supervision of the ], ], to showcase two paintings by ], ''Eleazar and Rebecca'' and ''Meal at the House of Simon the Pharisee'', which was a gift to Louis XIV from the ] in 1664. The painting on the ceiling, ''The Apotheosis of Hercules'', by ], was completed in 1736, and gave the room its name.{{Sfn|Saule |2013 |page=20}}{{sfn|Pérouse de Montclos|1991|pages=262–264}} | |||

| ====The Salon of Abundance==== | |||

| ==Post-royal: Museum of the History of France== | |||

| The Salon of Abundance was the antechamber to the Cabinet of Curios (now the Games Room), which displayed Louis XIV's collection of precious jewels and rare objects. Some of the objects in the collection are depicted in ]'s painting ''Abundance and Liberality'' (1683), located on the ceiling over the door opposite the windows. | |||

| After the Revolution the paintings and sculpture, like the crown jewels, were consigned to the new ] as part of the cultural patrimony of France. Other contents went to serve a new and moral public role: books and medals went to the ], clocks and scientific instruments (Louis XVI was a connoisseur of science) to the ]. Versailles was still the most richly-appointed royal palace of Europe until a long series of auction sales took place on the premises, which unrolled for months during the Revolution, emptying Versailles slowly of every shred of amenity, at derisory prices, mostly to professional ''brocanteurs''. The immediate purpose was to raise desperately-needed funds for the armies of the people, but the long-range strategy was to ensure that there was no Versailles for any king ever to come back to. The strategy worked. Though Versailles was declared an imperial palace, Napoleon never spent a summer's night there. | |||

| ====The Salon of Venus==== | |||

| Versailles remained both royal and unused through the ]. In 1830, the politic ] declared the château a museum dedicated to "''all'' the glories of France," raising it for the first time above a Bourbon dynastic monument. At the same time, ] from the private apartments of princes and courtiers were removed and found their way, without provenance, into the incipient art market in Paris and London for such panelling. What remained were 120 rooms, the modern "''Galeries Historiques''". The curator Pierre de Nohlac began the conservation of the palace in the 1880s, but did not have the necessary funding until ]'s gift of 60 million francs in 1924-1936. Its promotion as a tourist site started in the 1930s and accelerated in the 1950s and 1960s.<ref>Fabien Oppermann, "Images et usages du château de Versailles au XXe siècle", thesis, Ecole des Chartes, 2004.</ref> | |||

| This salon was used for serving light meals during evening receptions. The principal feature in this room is ]'s life-size statue of Louis XIV in the costume of a Roman emperor. On the ceiling in a gilded oval frame is another painting by Houasse, ''Venus subjugating the Gods and Powers'' (1672–1681). '']'' paintings and sculpture around the ceiling illustrate mythological themes.{{Sfn|Saule|2013|page=22}} | |||

| ====The Salon of Mercury==== | |||

| In the 1960s, ], the greatest writer on the history of ] managed to get some royal furnishings returned from the museums and ministries and ambassadors' residences where they had become scattered from the central warehouses of the Mobilier National. He conceived the bold scheme of refurnishing Versailles, and the refurnished royal ''Appartements'' that tourists view today are due to Verlet's successful initiative, in which textiles were even rewoven to refurbish the state beds. | |||

| The Salon of Mercury was the original State Bedchamber when Louis XIV officially moved the court and government to the palace in 1682. The bed is a replica of the original commissioned by King ] in the 19th century when he turned the palace into a museum. The ceiling paintings by the Flemish artist ] depict the god ] in his chariot, drawn by a rooster, and ] and ] surrounded by scholars and philosophers. The Automaton Clock was made for the King by the royal clockmaker Antoine Morand in 1706. When it chimes the hour, figures of Louis XIV and Fame descend from a cloud.{{Sfn|Saule|2013|page=25}} | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="200"> | |||

| Versailles retains the political function of hosting the ] when a dual meeting of the French Legislature considers a revision to the ]. | |||

| File:Chateau de Versailles, France (8132698654).jpg|Salon of Mars | |||

| File:Plafond-Salon d'Apollon-Versailles.jpg|Ceiling in the Salon of Apollo, depicting the Sun Chariot of ] | |||

| File:Château de Versailles, salon de Diane, buste de Louis XIV, Bernin (1665) 00.jpg|] in the Salon of Diana | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ====The Salon of Mars==== | |||

| ==Cost== | |||

| The Salon of Mars was used by the royal guards until 1782, and was decorated on a military theme with helmets and trophies. It was turned into a concert room between 1684 and 1750, with galleries for musicians on either side. Portraits of ] and his Queen, ], by the Flemish artist ] decorate the room today. | |||

| One of the most baffling aspects to the study of Versailles is the cost - how much Louis XIV and his successors spent on Versailles. Owing to the nature of the construction of Versailles and the evolution of the role of the palace, construction costs were essentially a private matter. Initially, Versailles was planned to be an occasional residence for Louis XIV and was referred to as the “king’s house.”<ref>(LaVarende, 1959)</ref> Accordingly, much of the early funding for construction came from the king’s own purse, funded by revenues received from his appanage as well as revenues from the province of New France (Canada), which, while part of France, was a private possession of the king and therefore exempt from the control of the Parliaments.<ref>(Bluche, 1986; 1991)</ref> | |||

| ====The Salon of Apollo==== | |||

| Once Louis XIV embarked on his building campaigns, expenses for Versailles became more of a matter for public record, especially after Jean-Baptiste Colbert assumed the post of finance minister. Expenditures on Versailles have been recorded in the compendium known as the ''Comptes des bâtiments du roi sous le règne de Louis XIV'' and which was edited and published in five volumes by Jules Guiffrey in the 19{{th}} century. These volumes provide valuable archival material pursuant to the financial expenditures of all aspects of Versailles from the payments dispursed to artists to mole catchers.<ref> Guiffrey, 1880-1890)</ref> | |||

| The Salon of Apollo was the royal throne room under Louis XIV, and was the setting for formal audiences. The eight-foot-high silver throne was melted down in 1689 to help pay the costs of an expensive war, and was replaced by a more modest throne of gilded wood. The central painting on the ceiling, by ], depicts the Sun Chariot of ], the King's favourite emblem, pulled by four horses and surrounded by the four seasons. | |||

| ====The Salon of Diana==== | |||

| To counter the costs of Versailles during the early years of Louis XIV’s personal reign, Colbert decided that Versailles should be the “showcase” of France. Accordingly, all materials that went into the construction and decoration of Versailles were manufactured in France.<ref>Even the mirrors used in the decoration of the Hall of Mirrors were made in France. While Venice in the 17{{th}} had the monopoly on the manufacture of mirrors, Colbert succeeded in enticing a number of artisans from Venice to make the mirrors for Versailles. However, owing to Venetian proprietary claims on the technology of mirror manufacture, the Venetian government ordered the assassination of the artisans to keep the secrets proprietary to the Venetian Republic.</ref> Accordingly, Colbert nationalized the tapestry factory owned by the Gobelin family, to become the Manufature royale des Gobelins.] In 1667, the name of the enterprise was changed to the Manufacture royale des Meubles de la Couronne.<ref>(Bluche, 1991.)</ref> The Gobelins were charged with all decoration needs of the palace, which was under the direction of ]. | |||

| The Salon of Diana was used by Louis XIV as a billiards room, and had galleries from which courtiers could watch him play. The decoration of the walls and ceiling depicts scenes from the life of the goddess ]. The celebrated ] made during the famous sculptor's visit to France in 1665 is on display here.{{Sfn|Saule|2013|page=23}} | |||

| ===Private apartments of the King and Queen=== | |||

| One of the most costly elements in the furnishing of the Grands Appartements during the early years of the personal reign of Louis XIV was the silver furniture, which can be taken as a standard – with other criteria – for determining a plausible cost for Versailles. The ''Comptes'' meticulously list the expenditures on the silver furniture – disbursements to artists, final payments, delivery – as well as descriptions and weight of items purchased. Entries for 1681 and 1682 concerning the silver balustrade used in the Salon de Mercure serve as an example: | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="200"> | |||

| File:Appartement du Roi (Versailles).jpg|King's bedchamber | |||

| File:Versailles Queen's Chamber.jpg|Queen's bedchamber | |||

| File:Cabinet dore Marie-Antoinette Versailles.jpg|Gilded cabinet of Marie Antoinette | |||

| File:Chateau Versailles cabinets interieurs de la Reine cabinet du Billard.jpg|Billiard Room of Marie Antoinette | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ====Private apartments of the King==== | |||

| * Year 1681 | |||

| {{Main|Appartement du roi|Petit appartement du roi}} | |||

| II. 5 In anticipation: For the silver balustrade for the king’s bedroom: 90,000 ''livres''</br> | |||

| II. 7 18 November to Sieur du Metz, 43,475 ''livres'' 5 sols for delivery to Sr. Lois et to Sr. de Villers for payment of 142,196 ''livres'' for the silver balustrade that they are making for the king’s bedroom and 404 ''livres'' for tax: 48,861 ''livres'' 5 sol.</br> | |||

| II. 15 16 June 1681 – 23 January 1682 to Sr. Lois and Sr. de Villers silversmiths on account for the sliver balustrade that they are making for the king’s use (four payments): 88,457 ''livres'' 5 sols.</br> | |||

| II. 111 25 March – 18 April to Sr. Lois et Sr. de Villers silversmiths who are working on a silver balustrade for the king, for continued work (two payments): 40,000 ''livres'' | |||

| The apartments of the King were the heart of the château; they were in the same location as the rooms of ], the creator of the château, on the first floor (second floor US style). They were set aside for the personal use of ] in 1683. He and his successors ] and ] used these rooms for official functions, such as the ceremonial '']'' ("waking up") and the ''coucher'' ("going to bed") of the monarch, which was attended by a crowd of courtiers. | |||

| * Year 1682 | |||