| Revision as of 14:23, 7 September 2008 editArilang1234 (talk | contribs)12,102 edits →Righteous Harmony Society 義和團← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:14, 23 January 2025 edit undoMellk (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users61,712 edits Undid revision 1271400036 by 191.243.31.33 (talk) not mentioned in article, see MOS:INFOBOXPURPOSE | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1899–1901 anti-imperialist uprising in China}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict| | |||

| {{For|the rock band from London|The Boxer Rebellion (band)}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=August 2023}} | |||

| partof=| | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2024}} | |||

| campaign=| | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| image=]| | |||

| | partof = | |||

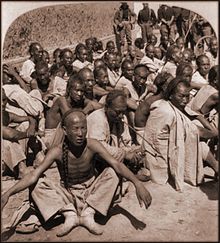

| caption=Boxer forces in Tianjin| | |||

| | conflict = Boxer Rebellion | |||

| date=], ]–], ]| | |||

| | image = Boxer-tianjing-left.jpeg | |||

| place=]| | |||

| | caption = A company of ] in 1901 | |||

| casus=], discontent of continuing Western and Japanese encroachment in China against the weak ]| | |||

| | date = 18 October 1899{{snd}}7 September 1901 | |||

| territory=| | |||

| | place = North China, ] | |||

| result=Alliance victory| | |||

| | result = ] victory | |||

| combatant1= | |||

| | combatant1 = {{udl|wrap= | |||

| ] (ordered by contribution): | |||

| ;] | |||

| {{flagicon|Empire of Japan}} ]<br> | |||

| :{{flag|British Empire}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Russia}} ]<br> | |||

| :{{flagcountry|Russian Empire}} | |||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br> | |||

| :{{flagcountry|Empire of Japan}} | |||

| {{flagicon|France}} ]<br> | |||

| :{{flagcountry|French Third Republic}} | |||

| {{flagicon|United States|1896}} ]<br> | |||

| {{ |

:{{flagcountry|German Empire}} | ||

| :{{flagcountry|United States|1896}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Italy|1861}} ]<br> | |||

| :{{flagcountry|Kingdom of Italy}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Austria-Hungary}} ]| | |||

| :{{flagcountry|Austria-Hungary}} | |||

| combatant2=] (Boxers) <br>{{flagicon|Qing Dynasty}} ]| | |||

| commander1={{flagicon|United Kingdom|size=23px}} ]<br>{{flagicon|German Empire|size=23px}} ]| | |||

| commander2={{flagicon|Qing Dynasty}} ]| | |||

| strength1=20,000 initially 49,000 total| | |||

| strength2=50,000–100,000 Boxers</br>70,000 Imperial troops| | |||

| casualties1=2,500 soldiers,<br> 526 foreigners and Chinese Christians| | |||

| casualties2="All" Boxers,<br> ? Imperial troops| | |||

| casualties3=Civilians = 18,952+ | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ---- | |||

| {{Campaignbox Boxer Rebellion}} | |||

| {{ubl | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Netherlands}} | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Spain|1874}} | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Belgium}} | |||

| }} | |||

| ---- | |||

| {{flagicon|Qing dynasty}} ] {{nwr|(after 1900)}} | |||

| | combatant2 = {{ubl | |||

| | ] ] | |||

| | {{flag|Qing dynasty}} {{nwr|(after 1900)}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | commander1 = {{udl|wrap= | |||

| ; Legations | |||

| : {{flagicon|UKGBI}} ] | |||

| ; Seymour Expedition | |||

| : {{flagicon|UKGBI}} ] | |||

| ; Gaselee Expedition | |||

| : {{flagicon|UKGBI}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|Empire of Japan|army}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|Empire of Japan|army}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|French Third Republic}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|United States|1896}} ] | |||

| ; Occupation Force | |||

| : {{flagicon|German Empire}} ] | |||

| ; Manchuria occupation | |||

| : {{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon image|Flag of CER (1897).svg}} ] | |||

| ; Mutual Defence Pact | |||

| : {{flagicon|Qing dynasty}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|Qing dynasty}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|Qing dynasty}} ] | |||

| : {{flagicon|Qing dynasty}} ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | commander2 = {{udl|wrap= | |||

| ; Imperial government | |||

| : ] | |||

| : ] | |||

| : ]{{Executed}} | |||

| ; Commander-in-chief | |||

| : ] | |||

| ; Hushenying | |||

| : ] | |||

| ; Tenacious Army | |||

| : ]{{KIA}} | |||

| ; Resolute Army | |||

| : ] | |||

| ; Gansu Army | |||

| : ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | strength1 = {{udl|wrap= | |||

| ; Seymour Expedition: 2,100{{nbnd}}2,188{{sfnp|Harrington|2001|p=29}} | |||

| ; Gaselee Expedition: 18,000{{sfnp|Harrington|2001|p=29}} | |||

| ; China Relief Expedition: 2,500<ref>{{Cite web |title=China Relief Expedition (Boxer Rebellion), 1900–1901 |url=http://www.veteranmuseum.org/chinarelief.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140716013130/http://www.veteranmuseum.org/chinarelief.html |archive-date=16 July 2014 |access-date=20 March 2017 |website=Veterans Museum and Memorial Center}}</ref> | |||

| ; Russian troops: 58,000<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Egorshina |first1=O. |last2=Petrova |first2=A. |year=2023 |publisher=Edition of the Russian Imperial Library |isbn=978-5-699-42397-2 |location=Moscow |page=719 |language=ru |script-title=ru:История русской армии |trans-title=The history of the Russian Army}}</ref> to 100,000<ref>Pronin, Alexander (7 November 2000). {{in lang|ru}}. '']''. Retrieved 6 July 2018.</ref> or 200,000<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hsü |first=Immanuel C. Y. |title=The Cambridge History of China |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1978 |isbn=978-0-521-22029-3 |editor-last=Fairbank |editor-first=John King |page=127 |chapter=Late Ch'ing Foreign Relations, 1866–1905 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pEfWaxPhdnIC&q=20%2C000%20russian%20manchuria&pg=PA127}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| | strength2 = {{udl|wrap= | |||

| ; Boxers: 100,000{{nbnd}}300,000 | |||

| ; Qing troops: 100,000{{sfnp|Xiang|2003|p=}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | casualties3 = {{ubl|32,000 Chinese Christians and 200 Western missionaries (northern China)<ref>{{Cite book |title=Hammond Atlas of the 20th Century |publisher=Hammond |year=1996 |isbn=978-0-8437-1149-3|page=22}}</ref>|100,000 total deaths<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Boxer Rebellion |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Boxer-Rebellion |date=13 September 2024}}</ref>}} | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Boxer Rebellion}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | t = 義和團運動 | |||

| | s = 义和团运动 | |||

| | p = Yìhétuán yùndòng | |||

| | tp = Yì-hé-tuán yùn-dòng | |||

| | w = {{tonesup|I4-ho2-t'uan2 yün4-tung4}} | |||

| | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|yi|4|.|h|e|2|.|t|uan|2|-|yun|4|.|d|ong|4}} | |||

| | bpmf = {{bpmfsp|ㄧˋ|ㄏㄜˊ|ㄊㄨㄢˊ|ㄩㄣˋ|ㄉㄨㄥˋ}} | |||

| | mnc = ᠴᡳᠣᠸᠠᠨ<br />ᠰᡝᡵᡝ<br />ᡝᡥᡝ<br />ᡥᡡᠯᡥᠠ ᡳ<br />ᡶᠠᠴᡠᡥᡡᠨ | |||

| | mnc_v = ciowan sere ehe hūlha i facuhūn | |||

| | l = Militia united in righteousness movement | |||

| | j = Ji6 wo4 tyun4 wan6 dung6 | |||

| | ci = {{IPAc-yue|j|i|6|-|w|o|4|-|t|yun|4|-|w|an|6|-|d|ung|6}} | |||

| | y = Yih-wòh-tyùhn wahn-duhng | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Contains special characters|Manchu}} | |||

| The '''Boxer Rebellion''', |

The '''Boxer Rebellion''', also known as the '''Boxer Uprising''', was an anti-foreign, ], and ] uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the ], by the ], known as the "Boxers" in English due to many of its members having practised ], which at the time were referred to as "Chinese boxing". It was defeated by the ] of foreign powers. | ||

| Following the ], villagers in North China feared the expansion of foreign ] and resented the extension of privileges to ], who used them to shield their followers. In 1898, North China experienced several natural disasters, including the ] flooding and droughts, which Boxers blamed on foreign and Christian influence. Beginning in 1899, the movement spread across ] and the ], destroying foreign property such as railroads, and attacking or murdering Christian missionaries and ]. The events came to a head in June 1900, when Boxer fighters, convinced they were invulnerable to foreign weapons, converged on Beijing with the slogan "Support the Qing government and exterminate the foreigners". | |||

| The members of the Society of Right and Harmonious Fists were simply called "Boxers" by the Westerners due to the ] and ] they practiced. The uprising began as an anti-foreign, anti-] peasant-based movement in northern China. They attacked foreigners who were building railroads (railways) and violating ], as well as ]s, who were held responsible for the foreign domination of China. In June 1900, the Boxers invaded ] and killed 230 foreign diplomats and foreigners. Some Chinese Christians were also killed, mostly in ] and ] Provinces as part of the uprising. | |||

| Diplomats, missionaries, soldiers, and some Chinese Christians took refuge in the ], which the Boxers besieged. The Eight-Nation Alliance—comprising American, Austro-Hungarian, British, French, German, Italian, Japanese, and Russian troops—moved into China to lift the siege and on 17 June stormed the ] at ]. ], who had initially been hesitant, supported the Boxers and on 21 June issued ] that was a de facto declaration of war on the invading powers. Chinese officialdom was split between those supporting the Boxers and those favouring conciliation, led by ]. The supreme commander of the Chinese forces, the Manchu general ], later claimed he acted to protect the foreigners. Officials in the ] ignored the imperial order to fight against foreigners. | |||

| The government of ] was not helpful, and diplomats, foreign civilians, soldiers and some ] retreated to the legation quarter where they held out for fifty-five days until a multi nation coalition rushed 20,000 troops to their rescue. The Chinese government was forced to indemnify the victims and make many additional concessions. Subsequent reforms implemented after the crisis of 1900 laid, at least in part, the end of the ] and the establishment of the modern ]. | |||

| The Eight-Nation Alliance, after initially being turned back by the Imperial Chinese military and Boxer militia, brought 20,000 armed troops to China. They defeated the Imperial Army in Tianjin and arrived in Beijing on 14 August, relieving the 55-day ]. Plunder and looting of the capital and the surrounding countryside ensued, along with summary execution of those suspected of being Boxers in retribution. The ] of 7 September 1901 provided for the execution of government officials who had supported the Boxers, for foreign troops to be stationed in Beijing, and for 450 million ]s of silver—more than the government's annual tax revenue—to be paid as ] over the course of the next 39 years to the eight invading nations. The Qing dynasty's handling of the Boxer Rebellion further weakened their control over China, and led to the ]. | |||

| ==Perspective== | |||

| == Background == | |||

| In traditional Western histories, the Boxers were condemned as a product of irrationality and xenophobia among the common people. However, controversy still exists about the significance of the movement. Today, the Boxers are praised by the ], in accordance with the Eastern perspective, as ] and anti-imperialists.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} | |||

| === Christian missionary activity === | |||

| According to ]:<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fairbank |first=John King |title=The United States and China |year=1983 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-92438-3 |edition=4th |series=American foreign policy library |location=Cambridge, MA |page=202 |orig-date=1948}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>The opening of the country in the 1860s facilitated the great effort to Christianize China. Building on old foundations, the Roman Catholic establishment totaled by 1894 some 750 European missionaries, 400 native priests, and over half a million communicants. By 1894 the newer Protestant mission effort supported over 1300 missionaries, mainly British and American, and maintained some 500 stations-each with a church, residences, street chapels, and usually a small school and possibly a hospital or dispensary-in about 350 different cities and towns. Yet they had made fewer than 60,000 Chinese Christian converts.</blockquote> | |||

| There was limited success in terms of converts and establishing schools in a nation of about 400 million people.<ref>Nigel Dalziel, ''The Penguin Historical Atlas of the British Empire'' (2006) pp. 102–103.</ref><ref>Andrew N. Porter, ed. ''The Imperial Horizons of British Protestant Missions, 1880–1914'' (Eerdmans, 2003).</ref> The missions faced escalating anger directed at the threat of cultural imperialism. The main result was the Boxer Rebellion, in which missions were attacked and thousands of Chinese Christians were massacred to destroy Western influences. | |||

| === Origins of the Boxers === | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] arose in the inland sections of the northern coastal province of ],{{sfnp|Hammond|2023|p=131}} a region which had long been plagued by social unrest, religious sects, and martial societies. American Christian missionaries were probably the first people who referred to the well-trained, athletic young men as the "Boxers", because of the martial arts which they practised and the weapons training which they underwent. Their primary practice was a type of ] which involved the whirling of swords, violent prostrations, and incantations to deities.{{sfnp|Thompson|2009|p=7}} | |||

| The opportunities to fight against Western encroachment were especially attractive to unemployed village men, many of whom were teenagers.{{sfnp|Cohen|1997|p=}} The tradition of possession and invulnerability went back several hundred years but took on special meaning against the powerful new weapons of the West.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|pp=}} The Boxers, armed with rifles and swords, claimed supernatural invulnerability against cannons, rifle shots, and knife attacks. The Boxer groups popularly claimed that millions of soldiers would descend out of heaven to assist them in purifying China of foreign oppression.{{sfnp|Xiang|2003|p=}} | |||

| ==Empress Dowager most remembered sayings== | |||

| In 1895, despite ambivalence toward their heterodox practices, ], a Manchu who was the then prefect of ] and would later become provincial governor, cooperated with the ], whose original purpose was to fight bandits.<ref name="Cohen1997 pp. 19–20">{{harvp|Cohen|1997|pp=}}</ref> The German Catholic missionaries of the ] had built up their presence in the area, partially by taking in a significant portion of converts who were "in need of protection from the law".<ref name="Cohen1997 pp. 19–20" /> On one occasion in 1895, a large bandit gang defeated by the Big Swords Society claimed to be Catholics to avoid prosecution. "The line between Christians and bandits became increasingly indistinct", remarks historian ].<ref name="Cohen1997 pp. 19–20" /> | |||

| *(1)天下,乃我爱新覺羅之天下 | |||

| Translation: ] ], was the clan name of the Manchu emperors of the Qing dynasty . The word aisin means gold in the ] language, and "gioro" means clan in the Manchu language. | |||

| Some missionaries such as ] also used their privileges to intervene in lawsuits. The Big Swords responded by attacking Catholic properties and burning them.<ref name="Cohen1997 pp. 19–20" /> As a result of diplomatic pressure in the capital, Yuxian executed several Big Sword leaders but did not punish anyone else. More martial secret societies started emerging after this.<ref name="Cohen1997 pp. 19–20" /> | |||

| 天下,Literary it means everything under the heaven.Used in this context,it means China as a nation.Empress Dowager was saying China,is the property of the Aisin Gioro clan.It is our family's private property,and has got nothing to do with anyone else. | |||

| *(2)量中华之物力,结与国之欢心 | |||

| The early years saw a variety of village activities, not a broad movement with a united purpose. Martial folk-religious societies such as the ] ('Eight Trigrams') prepared the way for the Boxers. Like the Red Boxing school or the ], the Boxers of Shandong were more concerned with traditional social and moral values, such as filial piety, than with foreign influences. One leader, Zhu Hongdeng (Red Lantern Zhu), started as a wandering healer, specialising in skin ulcers, and gained wide respect by refusing payment for his treatments.{{sfnp|Cohen|1997|pp=}} Zhu claimed descent from ] emperors, since his surname was the surname of the Ming imperial family. He announced that his goal was to "Revive the Qing and destroy the foreigners" ({{lang|zh|扶清滅洋}} {{transl|zh|fu Qing mie yang}}).{{sfnp|Xiang|2003|p=}} | |||

| After the Manchu Dynasty's humiliating defeat by the Eight Nations Alliance,the western powers demanded huge compensations.To this,Empress replied:量中华之物力, 中华,the original,and the oldest name of China.The whole phrase translate:We have to put together,and offer whatever China can manage to supply.结与国之欢心 translate:Have to try to satisfy foreign nation's desires,and make them happy. Put the two phrase together,we can then work out,that Empress Dowager always put the interests of Aisin Gioro clan at first priority,anything else is secondly. | |||

| *(3)宁与友邦,不与家奴 ,was a statement made by Empress Dowager during the siege of Peking by the Eight Nation Alliance. 家奴,private slaves,because Manchu's ancestors was a nomadic tribe 女真 nuchen,or jurchen,there was only two social classes:master,slave.You are either master,or slave.So Manchu rulers called their subjects "slaves" 奴,奴才,which in itself is a Manchu word.In making this statement,Dowager was saying she would give away anythings the foreign nations demanded,and will not give it to her own slaves(her countryman) | |||

| The enemy was seen as foreign influence. They decided the "primary devils" were the Christian missionaries while the "secondary devils" were the Chinese converts to Christianity, which both had either to repent, be driven out or killed.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Purcell |first=Victor |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2MeUoD9G9xAC&pg=PA125 |title=The Boxer Uprising: A Background Study |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-521-14812-2 |page=125}}</ref>{{sfnp|Preston|2000|p=}} | |||

| ==Failure of the ]== | |||

| The ] ( 戊戌變法); 11 June 1898 - 21 September 1898) was started. The leaders of the ] were ], ] ( 康有為) and ] ( 梁啟超). Eventually, it ended in a ] led by Empress Dowager Cixi.<br /> | |||

| Even though ] was a physically and mentally weak person,he still hoped that the will turn China into a strong and modern nation.However,with the ] ] flexing her powerful political muscle behind,the ] failed in about 100 days.<br /> | |||

| === Causes === | |||

| The Dragon ] ,then staged a ] by putting then young ] under house arrest in the middle of a lake,and had trusted eunuchs to keep watch,even though the Emperor was her own nephew.However,the western powers preferred ] to stay at the throne,and kept on pressuring Dowager to cease control of the Emperor.<br /> | |||

| ] (United Kingdom), ] (Germany), ] (Russia), ] (France) and a samurai (Japan), while the Boxer leader ] protests]] | |||

| Dowager refused,and started plotting with some officials to punish the foreign powers by recruiting the Boxer to kill foreign ] and Chinese ],end up causing Peking,an ancient imperial capital,to be sacked and looted by an international army. | |||

| The Boxer Rebellion was an anti-imperialist movement which sought to expel foreigners from China and end the system of ] and ].{{sfnp|Hammond|2023|p=131}} The rebellion had multiple causes.{{sfnp|Driscoll|2020|p=211}} Escalating tensions caused Chinese to turn against "foreign devils" who engaged in the ] in the late 19th century.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bickers |first=Robert |author-link=Robert Bickers |title=The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832–1914 |publisher=Penguin |year=2011}}</ref>{{page needed|date=March 2024}} The Western success at controlling China, growing anti-imperialist sentiment, and extreme weather conditions sparked the movement. A drought followed by floods in Shandong province in 1897–98 forced farmers to flee to cities and seek food.{{sfnp|Thompson|2009|p=9}} | |||

| ==] 義和團== | |||

| A major source of discontent in northern China was missionary activity. The Boxers opposed German missionaries in Shandong and in the German concession in ].{{sfnp|Hammond|2023|p=131}} The ] and the ], signed in 1860 after the ], had granted foreign missionaries the freedom to preach anywhere in China and to buy land on which to build churches.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|p=77}} There was strong public indignation over the dispossession of Chinese temples that were replaced by Catholic churches which were viewed as deliberately anti-].{{sfnp|Driscoll|2020|p=211}} A further cause of discontent among Chinese people were the destruction of Chinese burial sites to make way for German railroads and telegraph lines.{{sfnp|Driscoll|2020|p=211}} In response to Chinese protests against German railroads, Germans shot the protestors.{{sfnp|Schuman|2021|p=271}} | |||

| Economic conditions in Shandong also contributed to rebellion.{{sfnp|Schuman|2021|p=270}} Northern Shandong's economy focused significantly on cotton production and was hampered by the importation of foreign cotton.{{sfnp|Schuman|2021|p=270}} Traffic along the ] was also decreasing, further eroding the economy.{{sfnp|Schuman|2021|p=270}} The area had also experienced periods of drought and flood.{{sfnp|Schuman|2021|p=270}} | |||

| *At the beginning of the 20th century,China,for the past 260 plus years,had been under the rule of a ] tribe,],which had a population of fewer then 500 thousands at the beginning.The conquering of China(the majority of the population was ] 漢族) was through brute force and ],resulting in the annihilation of tens of millions of people. | |||

| *The ] law "To keep your hair,you lose your head" 留髮不留頭,which killed millions of Han,was designed to cow Han people into submission,as ] chieftains forced ] male to shave off the hair on their forehead,and grow a pigtail at the back. When Dr.] called for a ] to overthrow the ] and ] Manchu tribal chieftains,he started with cutting off his own ],as a signal to the beginning of the ]. | |||

| *Manchu Emperors,even though they had copied ]'s Imperial system to govern the country,in essence they still treated all their subjects as slaves,and Master own everything,including the life of the slaves.When western diplomats came to Manchu palace to see the emperors,all diplomats had to kneel in front of the emperors too,same like the rest of the emperor's subjects.Moreover,] emperors treated all foreigners "]",even though they themselves were not far from it. | |||

| A major precipitating incident was anger at the German Catholic Priest Georg Stenz, who had allegedly serially raped Chinese women in Juye County, Shandong.{{sfnp|Driscoll|2020|p=211}} In an attack known as the ], Chinese rebels attempted to kill Stenz in his missionary quarters,{{sfnp|Driscoll|2020|p=211}} but failed to find him and killed two other missionaries. The German Navy's ] dispatched to occupy ] on the southern coast of the Shandong peninsula.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|p=}} | |||

| *When hungry ] from ] area started to form groups with name "]",their initial objectives were to fight the Manchu chieftains.One of the original slogans was "反清復明" "To end the ]'s rule,To bring back ] Dynasty"(Which was also the slogan of the present day Chinese underground ]) | |||

| *However,] saw the value in them.She sent her officials to turn this "]" into a mob that began killing foreign missionaries and native ].She wanted to punish those ] who supported ]'s ].She could not use the Imperial army,she had to find an alternative.Hence the beginning of the Boxer rebellion,with a new agenda,and ] "扶清滅洋".Literally,it means "To support Qing's rule,To ] all the things ]" | |||

| In December 1897, Wilhelm ], which triggered a "scramble for ]" by which Britain, France, Russia and Japan also secured their own ] in China.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|pp=129–130}} Germany gained exclusive control of developmental loans, mining, and railway ownership in Shandong province. Russia gained influence of all territory north of the ],<ref name="Dallin2013" /> plus the previous tax exemption for trade in ] and ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Paine |first=S. C. M. |title=Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier |publisher=M. E. Sharpe |year=1996 |isbn=978-1-56324-724-8 |page= |chapter=Chinese Diplomacy in Disarray: The Treaty of Livadia |access-date=22 February 2018 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/imperialrivalsch00pain |chapter-url-access=registration}}</ref> economic powers similar to Germany's over ], Jilin and ]. France gained influence of ], most of ] and ], Japan over ]. Britain gained influence of the whole ] valley<ref name="LoUpshur2008" /> (defined as all provinces adjoining the Yangtze, as well as Henan and Zhejiang<ref name="Dallin2013">{{Cite book |last=Dallin |first=David J. |title=The Rise of Russia in Asia |publisher=Read Books |year=2013 |isbn=978-1-4733-8257-2 |chapter=The Second Drive to the Pacific, Section Port Arthur}}</ref>), parts of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces and part of Tibet.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Tibet Justice Center – Legal Materials on Tibet – Treaties and Conventions Relating to Tibet – Convention Between Great Britain and Tibet (1904) |url=https://www.tibetjustice.org/materials/treaties/treaties10.html |website=www.tibetjustice.org}}</ref>{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} Only Italy's request for Zhejiang was declined by the Chinese government.<ref name="LoUpshur2008">{{Cite book |last=Lo Jiu-Hwa |first=Upshur |title=Encyclopedia of World History, Ackerman-Schroeder-Terry-Hwa Lo, 2008: Encyclopedia of World History |publisher=Fact on File |year=2008 |volume=7 |pages=87–88}}</ref> These do not include the lease and concession territories where the foreign powers had full authority. The Russian government militarily occupied their zone, imposed their law and schools, seized mining and logging privileges, settled their citizens, and even established their municipal administration on several cities.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Shan |first=Patrick Fuliang |title=The Development of the North Manchuria Frontier, 1900–1931 |publisher=McMaster University |year=2003 |location=Hamilton, ON |page=13}}</ref> | |||

| *During the siege of the ] legation which went on for two months,] did not step in to offer protection for foreign ] and their families.And the provision of protection to foreign diplomats is a universal law being adopted by human ] for thousands of years.In the years of 1900,] ] chieftains chose to remain ignorant and ] by murdering foreign diplomats and ],then they should not be surprised to see foreign soldiers marching into their ]. | |||

| In October 1898, a group of Boxers attacked the Christian community of Liyuantun village where a temple to the ] had been converted into a Catholic church. Disputes had surrounded the church since 1869, when the temple had been granted to the Christian residents of the village. This incident marked the first time the Boxers used the slogan "Support the Qing, destroy the foreigners" ({{zhi|c=扶清滅洋|p=fu Qing mie yang}}) that later characterised them.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|pp=143–144, 163}} | |||

| == BMS Missionaries Beheaded== | |||

| The Boxers called themselves the "Militia United in Righteousness" for the first time in October 1899, at the ], a clash between Boxers and Qing government troops.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|p=253}} By using the word "Militia" rather than "Boxers", they distanced themselves from forbidden martial arts sects and tried to give their movement the legitimacy of a group that defended orthodoxy.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|p=32}} | |||

| By 1900 , along with many other missioanry organisations, had sent hundreds of ] to China's ] province, including ], the main city.In August 1900, an article in the mission's magazine Missionary Herald published a letter from ] hinting that there was " terrible cloud that hangs fierce and ominous over China". The news gradually emerged that there had been a ].<br /> | |||

| Missionary Herald, through letters and telegrams, were able to tell readers and relatives in ],what did their loved ones went through during 1900.The suffering and humiliation,and death,endured by the missionaries and their families,was considered "'''the darkest and most tragic episodes of ] world mission's history'''.<br /> | |||

| Violence toward missionaries and Christians drew sharp responses from diplomats protecting their nationals, including Western seizure of harbors and forts and the moving in of troops in preparation for all-out war, as well as taking control of more land by force or by coerced long-term leases from the Qing.{{sfnp|Spence|2012|pp=222–223}} In 1899, the French minister in Beijing helped the missionaries to obtain an edict granting official status to every order in the Roman Catholic hierarchy, enabling local priests to support their people in legal or family disputes and bypass the local officials. After the German government took over Shandong, many Chinese feared that the foreign missionaries and possibly all Christian activities were imperialist attempts at "carving the melon", i.e., to colonise China piece by piece.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|pp=68–95}} A Chinese official expressed the animosity towards foreigners succinctly, "Take away your missionaries and your opium and you will be welcome."{{sfnp|Thompson|2009|p=12}} | |||

| One of the telegram on 10/1900 Missionary Herald :"Mission houses in ] burned…. Missionaries fled there… promised safety, immediately massacred, altogether thirty-three Protestants. "<br /> | |||

| 12/1900 Missionary Herald:"tells of their discovery in a cave, where for five days they had been without food, and how, after promise of escort to the coast, they were cast into prison and afterwards murdered inside the city gate… the entire mission staff in the Province of Shanxi has perished. "<br /> | |||

| Missionary Herald reported again:The Shanxi governor Yuxian,with the full support of the ], ordered:"Foreign religions are reckless and oppressive, disrespectful to the gods and oppressive to the people. '''The righteous people(read Boxer) will burn and kill'''. "<br /> | |||

| It was very clear that ],the ] Dynasty supreme ruler,was giving the orders to both its governor Yuxian,and the Boxer,"it is OK to kill foreign missionaries and ] converts,the Imperial Court will back you up"<br /> | |||

| Missionary Herald further reported that at Taiyuan,the then governor sent in soldiers to round up missionaries,stripped them to the waist,and beheaded them in front of the governor's residence.It was the same at Xinzhou,another city,where 8 missionaries were put into a dungeon for two weeks before they were beheaded at the gate of the city. | |||

| In 1899, the Boxer Rebellion developed into a mass movement.{{sfnp|Hammond|2023|p=131}} The previous year, the ], in which progressive Chinese reformers persuaded the ] to engage in modernizing efforts, was suppressed by ] and ].{{sfnp|Hammond|2023|pp=12–13}} The Qing political elite struggled with the question of how to retain its power.{{sfnp|Hammond|2023|p=13}} The Qing government came to view the Boxers as a means to help oppose foreign powers.{{sfnp|Hammond|2023|p=13}} The national crisis was widely perceived as caused by "foreign aggression" inside,{{sfnp|Cohen|1997|p=114}} even though afterwards a majority of Chinese were grateful for the actions of the alliance.<ref name="Liu2021">{{Cite book |last=Liu |first=Qikun |title=Ba guo lian jun nai zheng yi zhi shi |publisher=Shibao chuban |year=2021 |isbn=978-957-13-9199-1 |location=Taipei |trans-title=Eight-nation alliance |author-mask=Liu Qikun (劉淇昆) |language=zh}}</ref>{{page needed|date=October 2022}} The Qing government was corrupt, common people often faced extortions from government officials and the government offered no protection from the violent actions of the Boxers.<ref name="Liu2021" /> | |||

| ==== | |||

| == Qing forces == | |||

| ] ] church,had set up mission in China at the end of the seventeenth century.A former Buddhist temple near Beijing was converted into a church dedicated to Saint Nicholas, and church vestments and holy objects were sent from the Imperial Court in Russia.<br /> | |||

| The ] had been dealt a severe blow by the ] and this had prompted military reform that was still in its early stages when the Boxer rebellion occurred and they were expected to fight. The bulk of the fighting was conducted by the forces already around ] with troops from other provinces only arriving after the main fighting had ended.{{sfnp|Powell|1955|pp=107–113}} | |||

| When ] ] had discovered that local ] ] followed orders from the ],Emperor Kangxi and his successors began persecutions against].Because of persecution,the then ] Emperor ] asked the ] church to stay low key,not to upset the Ch'ing dynasty or other missionary.<br /> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| The orthodox church's record has shown:Quote:By June 1900, placards calling for the death of foreigners and Christians covered the walls around ]. Armed bands combed the streets of the city, setting fire to homes and "with imperial blessing" killing Chinese ] and foreigners.Unquoted.<br /> | |||

| |+Estimates of Qing strength 1898–1900{{sfnp|Powell|1955|pp=107–113}} | |||

| On 10/6/1900,about 70 followers of Saint Mitrophan,and his 8 years old son,were all stabbed and burnt to death. | |||

| !Army | |||

| !The Boards of | |||

| War/Revenue | |||

| (field troops only) | |||

| !Russian General | |||

| Staff | |||

| (field troops only) | |||

| !E.H. Parker | |||

| (Zhili alone) | |||

| !The London Times | |||

| (Zhili alone) | |||

| |- | |||

| !Total | |||

| |360,000 | |||

| |205,000 | |||

| |125,000–130,000 | |||

| |110,000–140,000 | |||

| |} | |||

| The failure of the Qing forces to withstand the Allied forces was not surprising given the limited time for reform and the fact that the best troops of China were not committed to the fight, remaining instead in Huguang and Shandong. The officer corps was particularly deficient; many lacked basic knowledge of strategy and tactics, and even those with training had not actively commanded troops in the field. In addition, the regular soldiers were noted for their poor marksmanship and inaccuracy, while cavalry was ill-organised and was not used to its full extent. Tactically, the Chinese still retained their belief in the superiority of defence, often withdrawing as soon as they were flanked, a tendency attributable to their lack of combat experience and training as well as a lack of initiative from commanders who would rather retreat than counterattack. However, accusations of cowardice were minimal; this was a marked improvement from the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, as Chinese troops did not flee en masse as before. If led by courageous officers, the troops would often fight to the death as occurred under Nie Shicheng and Ma Yukun.{{sfnp|Powell|1955|pp=116–118}} | |||

| On the other hand, Chinese artillery was well-regarded, and caused far more casualties than the infantry at Tientsin, and proving themselves superior to Allied artillery in counter-battery fire. The infantry, for their part, were commended for their good usage of cover and concealment in addition to their tenacity in resistance.{{sfnp|Powell|1955|pp=116–118}} | |||

| ==== | |||

| The Boxers also targeted Jewish groups in the region destroying their reputation and leading to Britain temporarily vacating their civilian workers from the front lines. | |||

| The ] priests,Father Isore and Father Andlauer,were both killed at a ],quote:Then they beheaded them and displayed the heads of the Jesuits on the village gates as a brutal warning of what awaited ] who did not return to their ancestral religion. Unquoted.<br /> | |||

| == Boxer War == | |||

| ==English == | |||

| === Intensifying crisis === | |||

| Prpfessor's great-grandfather was a larger then life figure.Among many things,he was <br /> | |||

| ], known as the ]]] | |||

| (1) a spy and advisor for ],the leader of China's ],<br /> | |||

| In January 1900, with a majority of conservatives in the imperial court, Cixi changed her position on the Boxers and issued edicts in their defence, causing protests from foreign powers. Cixi urged provincial authorities to support the Boxers, although few did so.{{sfnp|Schuman|2021|p=272}} In the spring of 1900, the Boxer movement spread rapidly north from Shandong into the countryside near Beijing. Boxers burned Christian churches, killed Chinese Christians and intimidated Chinese officials who stood in their way. American Minister ] cabled Washington, "the whole country is swarming with hungry, discontented, hopeless idlers".{{sfnp|Thompson|2009|p=42}} | |||

| (2) advisor on ] affairs for the Chinese president and self-declared emperor ],<br /> | |||

| (3) sold 23,000 horses for the Chinese army.<br /> | |||

| Professor Henry Hart's grandmother,enchanted him with tales about how her father had saved her and numerous missionary families during China's Boxer Rebellion.<br /> | |||

| During those times,Boxers blamed “foreign devils” like his great-grandparents for causing northern China's drought and famine, exacerbating economic hardships by building railroads and telegraph lines (because such modern conveniences eliminated jobs), undermining the native textile industry with European imports, infecting and killing Chinese children with Christian prayers and for various other real and imagined infamies.<br /> | |||

| The great-grandfather had left him a journal,into it he wrote a first-person's account,on how, he and some hired ] fought off a group of ] attacking Boxers with wooden sticks,without firing a single shot from his old Winchester rifle.<br /> | |||

| Later on he led a group of fleeing ] for two months through the ] and the rest of ] to ].<br /> | |||

| The valuable information kept in the journal included the fact that the''' Boxer uprising ultimately claimed the lives of more than 32,000 Chinese Christians and several hundred foreign missionaries''' (historian Nat Brandt called it '''“the greatest single tragedy in the history of ] ]”). | |||

| ''' | |||

| On 30 May the diplomats, led by British Minister ], requested that foreign soldiers come to Beijing to defend the legations. The Chinese government reluctantly acquiesced, and the next day a multinational force of 435 navy troops from eight countries debarked from warships and travelled by train from the ] to Beijing. They set up defensive perimeters around their respective missions.{{sfnp|Thompson|2009|p=42}} | |||

| ==30,000 ]== | |||

| '''Reports on Oversea Missionary Fellowship on ]<br /> | |||

| ''' | |||

| Manchu Dynasty signing of the 1860 Peking Convention,enabled the ] Church to build ],] and ],resulting in large number of ] ] to work in China.<br /> | |||

| On 5 June 1900, the railway line to Tianjin was cut by Boxers in the countryside, and Beijing was isolated. On 11 June, at ], the secretary of the Japanese legation, Sugiyama Akira, was attacked and killed by the forces of General ], who were guarding the southern part of the Beijing walled city.{{sfnp|Preston|2000|p=70}} Armed with ] rifles but wearing traditional uniforms,{{sfnp|Elliott|2002|p=}} Dong's troops had threatened the foreign legations in the fall of 1898 soon after arriving in Beijing,{{sfnp|Xiang|2003|p=https://books.google.com/books?id=lAxresT12ogC&pg=PA207 207}} so much that ] had been called to Beijing to guard the legations.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Biggs |first=Chester M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S8YtE0SIDq0C&pg=PA25 |title=The United States Marines in North China, 1894–1942 |publisher=McFarland |year=2003 |isbn=0-7864-1488-X |page=25}}</ref> | |||

| The following list complied by the says it all:<br /> | |||

| Catholic ]<br /> | |||

| 30,000 ] ]<br /> | |||

| 2000 ] ]<br /> | |||

| 35 missionaries, 53 children<br /> | |||

| 47 ] ] & ]<br /> | |||

| ] losses - 58 missionaries, 21 children<br /> | |||

| Wilhelm was so alarmed by the Chinese Muslim troops that he requested Ottoman caliph ] to find a way to stop the Muslim troops from fighting.{{citation needed|date=October 2022}} Abdul Hamid agreed to the Kaiser's request and sent Enver Pasha (not to be confused with the ]) to China in 1901, but the rebellion was over by that time.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Karpat |first=Kemal H. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PvVlS3ljx20C&pg=PA237 |title=The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2001 |isbn=0-19-513618-7 |page=237}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=رشيد رضا |first=محمد |year=1901 |pages=229–230 |language=ar |script-title=ar:مجلة المنار؛ الجزء 4}}</ref> | |||

| First-hand eye-witness's account.<br /> | |||

| On 11 June, the first Boxer was seen in the ]. The German Minister ] and German soldiers captured a Boxer boy and inexplicably executed him.<ref>Weale, B. L. (]), ''Indiscreet Letters from Peking''. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1907, pp. 50–51.</ref> In response, thousands of Boxers burst into the walled city of Beijing that afternoon and burned many of the Christian churches and cathedrals in the city, burning some victims alive.{{sfnp|Edgerton|1997|p=}} American and British missionaries took refuge in the Methodist Mission, and an attack there was repulsed by US Marines. The soldiers at the British Embassy and German legations shot and killed several Boxers.{{sfn|Thompson|2009|pp=44–56}} The Kansu Braves and Boxers, along with other Chinese, then attacked and killed Chinese Christians around the legations in revenge for foreign attacks on Chinese.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Seagrave |first1=Sterling |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tURwAAAAMAAJ&q=kansu+braves+baron+von |title=Dragon Lady: The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China |last2=Seagrave |first2=Peggy |publisher=Knopf |year=1992 |isbn=978-0-679-40230-5 |page=320}}</ref> | |||

| (1) William S Fleming, an ], had become the first ] ]. Fleming died trying to protect his friend and assistant Pan Shoushan, a Black Miao convert. Pan Shoushan was also martyred.<br /> | |||

| (2) At the end of 1899, a missionary from the Society for the Propagation of the ] in Foreign Parts was murdered.<br /> | |||

| (3) On 24 June 1900, ] issued a decree ordering the destruction of all ‘foreign devils’. The hated barbarians were to be driven out of China.Westerners and Chinese Christians were hunted down, and houses, schools and churches burnt to the ground.<br /> | |||

| (4) Chang Yuwen, a 17-year-old Chinese Christian, was cut into pieces and his body nailed to a wall in Tangshan, Hebei Province. Others were shot, stabbed, stoned, run over by carts or strangled.<br /> | |||

| (5)Chen Xikong, another Christian in Hebei Province, had his heart cut out and placed on a stone. Some missionaries died, still kneeling in prayer.<br /> | |||

| (6)] worker Gilbert Ritchie wrote, ‘Alas, only a very few of my beloved fellow missionaries in the province of ] escaped the blood-stained hands of the Boxers.’ One of those ] was Ritchie’s Chinese helper, a converted ] priest.<br /> | |||

| (7) The Boxers entered ] waving the heads of murdered ], and were joined by imperial troops.<br /> | |||

| (8)One missionary, dying on the way to Hanzhou, whispered to her husband, ‘I wish I could have lived, I wish I could have gone back there to tell the people more about Jesus.’<br /> | |||

| (9)Those who escaped death, but had lost everything else, had only one thought - to return to their beloved Chinese as soon as possible.<br /> | |||

| (10)The Empress Dowager returned, and died in 1908, having given instructions for ] to be poisoned. She outlived him by one day, not realising that the ] itself had only three years to live. | |||

| === Seymour Expedition === | |||

| {{Main|Seymour Expedition}} | |||

| As the situation grew more violent, the Eight Powers authorities at Dagu dispatched a second multinational force to Beijing on 10 June 1900. This force of 2,000 sailors and marines was under the command of Vice Admiral ], the largest contingent being British. The force moved by train from Dagu to Tianjin with the agreement of the Chinese government, but the railway had been severed between Tianjin and Beijing. Seymour resolved to continue forward by rail to the break and repair the railway, or progress on foot from there, if necessary, as it was only 120 km from Tianjin to Beijing. The court then replaced Prince Qing at the Zongli Yamen with Manchu Prince Duan, a member of the imperial ] clan (foreigners called him a "Blood Royal"), who was anti-foreigner and pro-Boxer. He soon ordered the Imperial army to attack the foreign forces. Confused by conflicting orders from Beijing, General ] let Seymour's army pass by in their trains.{{sfnp|Leonhard|p=12}} | |||

| After leaving Tianjin, the force quickly reached ], but the railway was destroyed there. Seymour's engineers tried to repair the line, but the force found itself surrounded, as the railway in both behind directions was destroyed. They were attacked from all sides by Chinese irregulars and imperial troops. Five thousand of Dong Fuxiang's ] and an unknown number of Boxers won a costly but major victory over Seymour's troops at the ] on 18 June.{{sfnp|Leonhard|p=18}}{{sfnp|Cohen|1997|p=}} The Seymour force could not locate the Chinese artillery, which was raining shells upon their positions.{{sfnp|Smith|1901|loc=vol. 2, pp. 393, 441–448}}{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} Chinese troops employed mining, engineering, flooding, and simultaneous attacks. The Chinese also employed ]s, ambushes, and sniping with some success.{{sfnp|Smith|1901|loc=vol. 2, p. 446}}{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} | |||

| On 18 June, Seymour learned of attacks on the Legation Quarter in Beijing, and decided to continue advancing, this time along the ], toward ], {{convert|25|km|abbr=on}} from Beijing. By 19 June, the force was halted by progressively stiffening resistance and started to retreat southward along the river with over 200 wounded. The force was now very low on food, ammunition, and medical supplies. They happened upon ], a hidden Qing munitions cache of which the Eight Powers had had no knowledge until then. | |||

| ==The uprising== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] circa 1900.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The Imperial court's ]. One of the first signs of unrest appeared in a small village in Shandong province, where there had been a long dispute over the property rights of a temple between locals and the ] authorities. The Catholics claimed that the temple was originally a church abandoned for decades after the ] banned ] in China. The local court ruled in favor of the church, and angered villagers who claimed the temple for rituals. After the local authorities turned over the temple to the Catholics, the villagers (led by the Boxers) attacked the church building. | |||

| There they dug in and awaited rescue. A Chinese servant slipped through the Boxer and Imperial lines, reached Tianjin, and informed the Eight Powers of Seymour's predicament. His force was surrounded by Imperial troops and Boxers, attacked nearly around the clock, and at the point of being overrun. The Eight Powers sent a relief column from Tianjin of 1,800 men (900 Russian troops from Port Arthur, 500 British seamen, and other assorted troops). On 25 June the relief column reached Seymour. The Seymour force destroyed the Arsenal: they spiked the captured field guns and set fire to any munitions that they could not take (an estimated £3 million worth). The Seymour force and the relief column marched back to Tientsin, unopposed, on 26 June. Seymour's casualties during the expedition were 62 killed and 228 wounded.{{sfnp|Preston|2000|pp=100–104}} | |||

| The exemption from many Chinese laws of missionaries further alienated some Chinese. ] pointed to the policy pursued by Catholic missionaries. In 1899, with the help of the French Minister in Peking, they obtained an edict from the Chinese Government granting official rank to each order in the Roman Catholic hierarchy. The Catholics, by means of this official status, were able to more powerfully support their people and oppose ].<ref>Broomhall (1901), 7.</ref> cayla*** | |||

| === Conflict within the Qing imperial court === | |||

| The early months of the movement's growth coincided with the ] (]–], ]), during which the ] sought to improve the central administration, though the process was reversed by several court reactionaries. After the Boxers were mauled by loyal Imperial troops in October 1898, they dropped their anti-government slogans and turned their attention to foreign ] (such as those of the ]) and their converts, whom they saw as agents of foreign imperialist influence. | |||

| Meanwhile, in Beijing, on 16 June, Empress Dowager Cixi summoned the imperial court for a mass audience and addressed the choice between using the Boxers to evict the foreigners from the city, and seeking a diplomatic solution. In response to a high official who doubted the efficacy of the Boxers, Cixi replied that both sides of the debate at the imperial court realised that popular support for the Boxers in the countryside was almost universal and that suppression would be both difficult and unpopular, especially when foreign troops were on the march.{{sfnp|Esherick|1987|pp=https://books.google.com/books?id=jVESdBSMasMC 289–290}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Purcell |first=Victor |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2MeUoD9G9xAC&q=cannot%20rely%20charms%20heart%20people%20lose&pg=PA250 |title=The Boxer Uprising: A Background Study |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-521-14812-2 |page=250}}</ref> | |||

| === Siege of the Beijing legations === | |||

| :Veteran missionary ] noted afterward: | |||

| {{main|Siege of the International Legations}} | |||

| :{{cquote|''It is the height of folly to look at the present movement as anti-missionary. It is anti-missionary as it is anti-everything that is foreign...The movement is at first and last an anti-foreign movement, and has for its aim the casting out of every foreigner and all his belongings.''<ref>Broomhall (1901), 10.</ref>}} | |||

| ] | |||

| On 15 June, Qing imperial forces deployed electric ]s in the ] to prevent the Eight-Nation Alliance from sending ships to attack.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/reportsonmilita01divigoog |title=Reports on Military Operations in South Africa and China |publisher=Government Printing Office |year=1901 |location=Washington, D.C. |page=}}</ref>{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} With a difficult military situation in Tianjin and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence significantly. On 17 June, Allied forces under Russian Admiral ] took the Dagu Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought increasing numbers of troops on shore. When Cixi received an ultimatum that same day demanding that China surrender total control over all its military and financial affairs to foreigners,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Laidler |first=Keith |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QLPZ7294oSIC&pg=PA221 |title=The Last Empress: The She-Dragon of China |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=2003 |isbn=0-470-86426-5 |page=221}}</ref> she defiantly stated before the entire ], "Now they have started the aggression, and the extinction of our nation is imminent. If we just fold our arms and yield to them, I would have no face to see our ancestors after death. If we must perish, why don't we fight to the death?"<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tan |first=Chester C. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_gcOAQAAMAAJ&q=extinction+nation |title=The Boxer catastrophe |publisher=Octagon |year=1967 |isbn=0-374-97752-6 |edition=Repr. |page=73 |issue=Issue 583 of Columbia Studies in the Social Sciences}}</ref> It was at this point that Cixi began to blockade the legations with the armies of the ], which began the siege. Cixi stated that "I have always been of the opinion, that the allied armies had been permitted to escape too easily in 1860. Only a united effort was then necessary to have given China the victory. Today, at last, the opportunity for revenge has come", and said that millions of Chinese would join the cause of fighting the foreigners since the Manchus had provided "great benefits" on China.<ref>{{Cite book |last=O'Connor |first=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P4NxAAAAMAAJ&q=extinction+imminent |title=The Spirit Soldiers: A Historical Narrative of the Boxer Rebellion |publisher=Putnam |year=1973 |isbn=978-0-399-11216-4 |edition=Illustrated |page=85}}</ref> On receipt of the news of the attack on the ]s on 19 June, Empress Dowager Cixi immediately sent an order to the legations that the diplomats and other foreigners depart Beijing under escort of the Chinese army within 24 hours.<ref>Tan, p. 75</ref> | |||

| The next morning, diplomats from the besieged legations met to discuss the Empress's offer. The majority quickly agreed that they could not trust the Chinese army. Fearing that they would be killed, they agreed to refuse the Empress's demand. The German Imperial Envoy, Baron ], was infuriated with the actions of the Chinese army troops and determined to take his complaints to the royal court. Against the advice of the fellow foreigners, the baron left the legations with a single aide and a team of porters to carry his sedan chair. On his way to the palace, von Ketteler was killed on the streets of Beijing by a Manchu captain.{{sfnp|Edgerton|1997|p=}} His aide managed to escape the attack and carried word of the baron's death back to the diplomatic compound. At this news, the other diplomats feared they also would be murdered if they left the legation quarter and they chose to continue to defy the Chinese order to depart Beijing. The legations were hurriedly fortified. Most of the foreign civilians, which included a large number of missionaries and businessmen, took refuge in the British legation, the largest of the diplomatic compounds.{{sfnp|Preston|2002|p=87}} Chinese Christians were primarily housed in the adjacent palace (Fu) of ], who was forced to abandon his property by the foreign soldiers.{{sfnp|Preston|2002|p=79}} | |||

| Now with a majority of conservative reactionaries in the Imperial Court, the Empress Dowager issued edicts in defence of the Boxers, drawing heated complaints from foreign diplomats in January, 1900. In June 1900 the Boxers, now joined by elements of the Imperial army, attacked foreign compounds in the cities of ] and ]. The ]s of the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], the ], the ], ] and ] were all located on the ] close to the ] in Peking. The legations were hurriedly linked into a fortified compound that became a refuge for foreign citizens in Peking. The Spanish and Belgian legations were a few streets away, and their staff were able to arrive safely at the compound. The German legation on the other side of the city was stormed before the staff could escape. When the Envoy for the German Empire, ], was murdered on ] by a Manchu banner man, the foreign powers demanded redress. On ] ] declared war against all Western powers, but regional governors refused to cooperate. Shanghai's Chinese elite supported the provincial governors of southeastern China in resisting the imperial declaration of war.<ref>Chen (1994).</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Siege in Peking== | |||

| On 21 June, Cixi issued ] stating that hostilities had begun and ordering the regular Chinese army to join the Boxers in their attacks on the invading troops. This was a {{lang|la|de facto}} declaration of war, but the Allies also made no formal declaration of war.{{sfnp|Klein|2008}} Regional governors in the south, who commanded substantial modernised armies, such as ] at Guangzhou, ] in Shandong, ]{{sfnp|Rhoads|2000|pp=}} at Wuhan, and ] at Nanjing, formed the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Luo |first=Zhitian |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=avlyBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA19 |title=Inheritance within Rupture: Culture and Scholarship in Early Twentieth Century China |publisher=Brill |year=2015 |isbn=978-90-04-28766-2 |page=19}}</ref> They refused to recognise the imperial court's declaration of war, which they declared a {{tlit|zh|luan-ming}} (illegitimate order) and withheld knowledge of it from the public in the south. Yuan Shikai used his own forces to suppress Boxers in Shandong, and Zhang entered into negotiations with the foreigners in Shanghai to keep his army out of the conflict. The neutrality of these provincial and regional governors left the majority of Chinese military forces out of the conflict.{{sfnp|Hsü|2000|pp=395–398}} The republican revolutionary Sun Yat-sen even took the opportunity to submit a proposal to Li Hongzhang to declare an independent democratic republic, although nothing came of the suggestion.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Teng |first1=Ssu-yü |title=China's Response to the West A Documentary Survey, 1839–1923 |last2=Fairbank |first2=John King |publisher=Harvard University Press |year=1979 |isbn=978-0-674-12025-9 |volume=1–2 |page=226}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Siege of the Foreign Legations}} | |||

| The legations of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, Russia and Japan were located in the ] south of the ]. The Chinese army and Boxer irregulars besieged the Legation Quarter from 20 June to 14 August 1900. A total of 473 foreign civilians, 409 soldiers, marines and sailors from eight countries, and about 3,000 Chinese Christians took refuge there.{{sfnp|Thompson|2009|pp=84–85}} Under the command of the British minister to China, ], the legation staff and military guards defended the compound with small arms, three machine guns, and one old muzzle-loaded cannon, which was nicknamed the ''International Gun'' because the barrel was British, the carriage Italian, the shells Russian and the crew American. Chinese Christians in the legations led the foreigners to the cannon and it proved important in the defence. Also under siege in Beijing was the ] (''Beitang'') of the Catholic Church. The cathedral was defended by 43 French and Italian soldiers, 33 Catholic foreign priests and nuns, and about 3,200 Chinese Catholics. The defenders suffered heavy casualties from lack of food and from mines which the Chinese exploded in tunnels dug beneath the compound.{{sfnp|Thompson|2009|pp=85, 170–171}} The number of Chinese soldiers and Boxers besieging the Legation Quarter and the Beitang is unknown.{{sfnp|Rhoads|2000| p=}} Zaiyi's bannermen in the ] led attacks against the Catholic cathedral church.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Landor |first=Arnold Henry Savage |author-link=Arnold Henry Savage Landor |title=China and the allies, Volume 1 |publisher=Charles Scribner's Sons |year=1901 |page=24}}</ref>{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} | |||

| The fortified legation compound in Peking remained under siege from Boxer forces from ] to ]. Under the command of the British minister to China, ], the legation staff and security personnel defended the compound with one old muzzle-loaded cannon; it was nicknamed the "International Gun" because the barrel was British, the carriage was Italian, the shells were Russian, and the crew were from the United States. | |||

| On 22 and 23 June, Chinese soldiers and Boxers set fire to areas north and west of the British Legation, using it as a "frightening tactic" to attack the defenders. The nearby ], a complex of courtyards and buildings that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship ... the oldest and richest library in the world", caught fire. Each side blamed the other for the destruction of the invaluable books it contained.<ref>{{Cite news |title=Destruction of Chinese Books in the Peking Siege of 1900. Donald G. Davis, Jr. University of Texas at Austin, Cheng Huanwen Zhongshan University, PRC |url=http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla62/62-davd.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080919024848/http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla62/62-davd.htm |archive-date=19 September 2008 |access-date=26 October 2008 |publisher=International Federation of Library Association}}</ref> | |||

| Foreign media described the fighting going on in Peking as well as the alleged torture and murder of captured foreigners. Whilst it is true that tens of thousands of Chinese Christians were massacred in north China, many horrible stories that appeared in world newspapers were based on a deliberate fraud<ref> Preston (2000) Page 173-4.</ref>. Nonetheless a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment arose in Europe, the United States and Japan. <ref>Elliott (1996)</ref> | |||

| ]{{snd}}''The destruction of a Chinese temple on the bank of the Pei-Ho'', by ]]] | |||

| The poorly armed Boxer rebels were unable to break into the compound, which was relieved by an international army of the ] in July. | |||

| After the failure to burn out the foreigners, the Chinese army adopted an anaconda-like strategy. The Chinese built barricades surrounding the Legation Quarter and advanced, brick by brick, on the foreign lines, forcing the foreign legation guards to retreat a few feet at a time. This tactic was especially used in the Fu, defended by Japanese and Italian sailors and soldiers, and inhabited by most of the Chinese Christians. Fusillades of bullets, artillery and firecrackers were directed against the Legations almost every night—but did little damage. Sniper fire took its toll among the foreign defenders. Despite their numerical advantage, the Chinese did not attempt a direct assault on the Legation Quarter although in the words of one of the besieged, "it would have been easy by a strong, swift movement on the part of the numerous Chinese troops to have annihilated the whole body of foreigners ... in an hour".{{sfnp|Smith|1901|loc=vol. 2, pp. 393, 316–317}}{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} American missionary ] and his crew of "fighting parsons" fortified the Legation Quarter,<ref>Weale, Putnam. ''Indiscreet Letters from Peking''. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1907, pp. 142–143</ref>{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} but impressed Chinese Christians to do most of the physical labour of building defences.<ref>Payen, Cecile E. "Besieged in Peking". ''The Century Magazine'', January 1901, pp. 458–460</ref>{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} | |||

| The Germans and the Americans occupied perhaps the most crucial of all defensive positions: the ]. Holding the top of the {{convert |45|ft|m|abbr=on}} tall and {{convert |40|ft|m|abbr=on}} wide wall was vital. The German barricades faced east on top of the wall and {{convert |400|yd|m|abbr=on}} west were the west-facing American positions. The Chinese advanced toward both positions by building barricades even closer. "The men all feel they are in a trap", said the US commander Capt. ], "and simply await the hour of execution".<ref>Myers, Captain John T. "Military Operations and Defenses of the Siege of Peking". ''Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute'', September 1902, pp. 542–550.</ref> On 30 June, the Chinese forced the Germans off the Wall, leaving the American Marines alone in its defence. In June 1900, one American described the scene of 20,000 Boxers storming the walls:{{sfnp|Roark|Johnson|Furstenburg|Cline Cohen|2020}}{{sfnp|Roark|Johnson|Furstenburg|Cline Cohen|2020}} | |||

| ==Eight-Nation Alliance== | |||

| {{main|Eight-Nation Alliance}} | |||

| The rebellion was stopped by an alliance of eight nations, including ], ], ], ], ], ], the ] and the ]. | |||

| {{blockquote|Their yells were deafening, while the roar of gongs, drums, and horns sounded like thunder ... They waved their swords and stamped on the ground with their feet. They wore red turbans, sashes, and garters over blue cloth ... They were now only twenty yards from our gate. Three or four volleys from the ]s of our marines left more than fifty dead on the ground.}} | |||

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]. Japanese print, 1900.]] | |||

| At the same time, a Chinese barricade was advanced to within a few feet of the American positions, and it became clear that the Americans had to abandon the wall or force the Chinese to retreat. At 2 am on 3 July 56 British, Russian and American marines and sailors, under the command of Myers, launched an assault against the Chinese barricade on the wall. The attack caught the Chinese sleeping, killed about 20 of them, and expelled the rest of them from the barricades.<ref>Oliphant, Nigel, ''A Diary of the Siege of the Legations in Peking''. London: Longman, Greens, 1901, pp 78–80</ref>{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} The Chinese did not attempt to advance their positions on the Tartar Wall for the remainder of the siege.<ref>Martin, W. A. P. ''The Siege in Peking''. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1900, p. 83</ref>{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} | |||

| ===Reinforcements=== | |||

| Foreign navies started building up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. On ], before the sieges had started and upon the request of foreign embassies in Beijing, an International force of 435 navy troops from eight countries were dispatched by train from ] to the capital (75 French, 75 Russian, 75 British, 60 U.S., 50 German, 40 Italian, 30 Japanese, 30 Austrian); these troops joined the legations and were able to contribute to their defence. | |||

| Sir Claude MacDonald said 13 July was the "most harassing day" of the siege.{{sfnp|Fleming|1959|pp=157–158}} The Japanese and Italians in the Fu were driven back to their last defence line. The Chinese detonated a mine beneath the French Legation pushing the French and Austrians out of most of the French Legation.{{sfnp|Fleming|1959|pp=157–158}} On 16 July, the most capable British officer was killed and the journalist ] was wounded.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Thompson |first1=Peter |title=The Man who Died Twice: The Life and Adventures of Morrison of Peking |last2=Macklin |first2=Robert |publisher=Allen & Unwin |year=2005 |location=Crow's Nest, Australia |pages=190–191}}</ref> American Minister ] established contact with the Chinese government and on 17 July, and an armistice was declared by the Chinese.{{sfnp|Conger|1909|p=135}}{{primary source inline|date=October 2022}} | |||

| ===First intervention (Seymour column)=== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| As the situation worsened, a second International force of 2,000 marines under the command of the British Vice Admiral ], the largest contingent being British, was dispatched from ] to Beijing on June 10. The troops were transported by train from Takou to ] (Tien-Tsin) with the agreement of the Chinese government, but the railway between Tianjin and Beijing had been severed. Seymour however resolved to move forward and repair the rail or such as the train, or progress on foot as necessary, keeping in mind that the distance between Tianjin and Beijing was only 120 kilometers. | |||

| === Infighting among officials and commanders === | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| After Tianjin however, the convoy was surrounded, the railway behind and in front of them was destroyed, and they were attacked from all parts by Chinese irregulars and even Chinese governmental troops. News arrived on June 18 regarding attacks on foreign legations. Seymour decided to continue advancing, this time along the ] river, towards ], 25 kilometers from Beijing. By the 19th, they had to abandon their efforts due to progressively stiffening resistance, and started to retreat southward along the river with over two hundred wounded. Commandeering four civilian Chinese ]s along the river, they loaded all their wounded and remaining supplies onto them and pulled them along with ropes from the riverbanks. By this point, they were very low on food, ammunition and medical supplies. Luckily, they then happened upon ], a hidden Qing munitions cache that the western powers had had no knowledge of until then. They immediately captured and occupied it, discovering not only German Krupp made field guns, but rifles with millions of rounds in ammunition, along with millions of pounds of rice. Further, medical supplies were ample too. There they dug in and awaited rescue. A Chinese servant was able to infiltrate through the boxer and Qing lines, informing the western powers of their predicament. Surrounded and attacked nearly around the clock by Qing troops and boxers, they were at the point of being overrun. On June 25 however a ] composed of 1800 men, (900 Russian troops from ], 500 British seamen, with an ad hoc mix of other assorted western troops) finally arrived. Spiking the mounted field guns and setting fire to any munitions that they could not take (an estimate £3 million worth), they departed the Hsi-Ku Arsenal in the early morning of ], with the loss of 62 killed and 228 wounded.<ref>Account of the Seymour column in "The Boxer Rebellion", pgs 100-104, Diane Preston</ref> | |||

| General ] concluded that it was futile to fight all of the powers simultaneously and declined to press home the siege.{{sfnp|Cohen|1997|p=54}} Zaiyi wanted artillery for Dong's troops to destroy the legations. Ronglu blocked the transfer of artillery to Zaiyi and Dong, preventing them from attacking.{{citation needed|date=August 2024}} Ronglu forced Dong Fuxiang and his troops to pull back from completing the siege and destroying the legations, thereby saving the foreigners and making diplomatic concessions.{{sfnp|Cohen|1997|p=}} Ronglu and Prince Qing sent food to the legations and used their bannermen to attack the Gansu Braves of Dong Fuxiang and the Boxers who were besieging the foreigners. They issued edicts ordering the foreigners to be protected, but the Gansu warriors ignored it, and fought against bannermen who tried to force them away from the legations. The Boxers also took commands from Dong Fuxiang.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Elleman |first=Bruce A. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Md801mHEeOkC&pg=PA124 |title=Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 |publisher=Psychology Press |year=2001 |isbn=0-415-21474-2 |page=124}}</ref> Ronglu also deliberately hid an Imperial Decree from ]. The Decree ordered him to stop fighting the Boxers because of the foreign invasion, and also because the population was suffering. Due to Ronglu's actions, Nie continued to fight the Boxers and killed many of them even as the foreign troops were making their way into China. Ronglu also ordered Nie to protect foreigners and save the railway from the Boxers.{{sfnp|Xiang|2003|p=https://books.google.com/books?id=lAxresT12ogC&pg=PA235 235}} Because parts of the railway were saved under Ronglu's orders, the foreign invasion army was able to transport itself into China quickly. Nie committed thousands of troops against the Boxers instead of against the foreigners, but was already outnumbered by the Allies by 4,000 men. He was blamed for attacking the Boxers, and decided to sacrifice his life at Tietsin by walking into the range of Allied guns.{{sfnp|Elliott|2002|p=499}} | |||

| ], who had served as the envoy to many of the same states under siege in the Legation Quarter, argued that "the evasion of extraterritorial rights and the killing of foreign diplomats are unprecedented in China and abroad".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Zhao |first=Erxun |title=Qing shi gao |publisher=Xinhua Bookstore |location=Beijing |year=1976 |language=zh |oclc=17045858 |ref=none |author-mask=Zhao Erxun (趙爾巽)}}</ref>{{page needed|date=October 2022}} Xu and five other officials urged Empress Dowager Cixi to order the repression of Boxers, the execution of their leaders, and a diplomatic settlement with foreign armies. The Empress Dowager was outraged, and sentenced Xu and the five others to death for "willfully and absurdly petitioning the imperial court" and "building subversive thought". They were executed on 28 July 1900 and their severed heads placed on display at ] in Beijing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=資料連結 |url=http://archive.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/ttscgi/ttsquery?0:0:mctauac:TM%3D%B3%5C%B4%BA%BC%E1 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20121222084857/http://archive.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/ttscgi/ttsquery?0:0:mctauac:TM%3D%B3%5C%B4%BA%BC%E1 |archive-date=22 December 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ===Second intervention=== | |||

| {{Boxer Rebellion}} | |||

| With a difficult military situation in Tianjin, and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence significantly. On June 17, they took the ] commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought increasing numbers of troops on shore. | |||

| Reflecting this vacillation, some Chinese soldiers were quite liberally firing at foreigners under siege from its very onset. Cixi did not personally order imperial troops to conduct a siege, and on the contrary had ordered them to protect the foreigners in the legations. Prince Duan led the Boxers to loot his enemies within the imperial court and the foreigners, although imperial authorities expelled Boxers after they were let into the city and went on a looting rampage against both the foreign and the Qing imperial forces. Older Boxers were sent outside Beijing to halt the approaching foreign armies, while younger men were absorbed into the Muslim Gansu army.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hayter-Menzies |first=Grant |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sNPFc7kkjwAC&pg=PA88 |title=Imperial masquerade: the legend of Princess Der Ling |publisher=Hong Kong University Press |year=2008 |isbn=978-962-209-881-7 |page=88}}</ref> | |||

| The international force, with British ] ] acting as the commanding officer, called the ], eventually numbered 54,000, with the main contingent being composed of Japanese soldiers: Japanese (20,840), Russian (13,150), British (12,020), French (3,520), U.S.(3,420), German (900), Italian (80), ] (75), and anti-Boxer Chinese troops.<ref></ref> The international force finally captured Tianjin on ] under the command of the Japanese colonel ], after one day of fighting. | |||

| With conflicting allegiances and priorities motivating the various forces inside Beijing, the situation in the city became increasingly confused. The foreign legations continued to be surrounded by both Qing imperial and Gansu forces. While Dong's Gansu army, now swollen by the addition of the Boxers, wished to press the siege, Ronglu's imperial forces seem to have largely attempted to follow Cixi's decree and protect the legations. However, to satisfy the conservatives in the imperial court, Ronglu's men also fired on the legations and let off firecrackers to give the impression that they, too, were attacking the foreigners. Inside the legations and out of communication with the outside world, the foreigners simply fired on any targets that presented themselves, including messengers from the imperial court, civilians and besiegers of all persuasions.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hayter-Menzies |first=Grant |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sNPFc7kkjwAC&pg=PA88 |title=Imperial Masquerade: The Legend of Princess Der Ling |publisher=Hong Kong University Press |year=2008 |isbn=978-962-209-881-7 |page=89}}</ref> Dong Fuxiang was denied artillery held by Ronglu which stopped him from levelling the legations, and when he complained to Empress Dowager Cixi on 23 June, she dismissively said that "Your tail is becoming too heavy to wag." The Alliance discovered large amounts of unused Chinese ]s and shells after the siege was lifted.{{sfnp|Fleming|1959|p=226}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Notable exploits during the campaign were the seizure of the ] commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by ]. The march from Tianjin to Beijing of about 120 km consisted of about 20,000 allied troops. On ] there were approximately 70,000 Imperial troops with anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Boxers along the way. They only encountered minor resistance and the battle was engaged in ], about 30 km outside Tianjin, where the ] of the U.S. and British troops led the assault. However, the weather was a major obstacle, extremely humid with temperatures sometimes reaching 110 ] (43]). | |||

| === Gaselee Expedition === | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Gaselee Expedition}} | |||

| The International force reached and occupied Beijing on ]. The United States was able to play a secondary, but significant role in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion largely due to the presence of U.S. ships and troops deployed in the ] since the U.S conquest of the ] and ]. In the ], the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion was known as the ]. | |||

| Foreign navies started building up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. Several international forces were sent to the capital, with varying success, and the Chinese forces were ultimately defeated by the Alliance. Independently, the Netherlands dispatched three cruisers in July to protect its citizens in Shanghai.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cNcUAAAAIAAJ |title=Acta Historiae Neerlandica: Historical Studies in the Netherlands |publisher=Brill |year=1970 |editor-last=Nordholt |editor-first=J. W. Schulte |volume=IV |pages=160–161, 163–164 |editor-last2=van Arkel |editor-first2=D.}}</ref> | |||