| Revision as of 17:50, 30 September 2005 view sourceJguk (talk | contribs)15,849 editsm rv - the spelling and the grammar were fine← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:05, 20 January 2025 view source Fgnievinski (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users67,467 edits →topTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App section source | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Prehistoric period before metal tools}} | |||

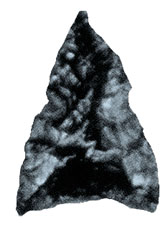

| ] ]head]] | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=October 2022}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| ] temples in ], Malta, {{Circa|3600}}–2500 BC, some of the world's oldest free-standing structures]] | |||

| {{Stone Age|260}} | |||

| {{History of technology sidebar}} | |||

| The '''Stone Age''' was a broad ] period during which ] was widely used to make ]s with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years<ref name="nhm.ac.uk">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2010/august/oldest-tool-use-and-meat-eating-revealed75831.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100818123718/http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2010/august/oldest-tool-use-and-meat-eating-revealed75831.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=18 August 2010|title=Oldest tool use and meat-eating revealed | Natural History Museum|date=18 August 2010}}</ref> and ended between 4000 ] and 2000 BC, with the advent of ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Stone Age|url=https://www.history.com/topics/pre-history/stone-age|website=HISTORY|language=en|access-date=2020-05-31}}</ref> It therefore represents nearly 99.3% of human history. | |||

| The '''Stone Age''' is a broad ] time period during which ]s widely used ] for toolmaking. | |||

| Though some simple metalworking of malleable metals, particularly the use of ] and ] for purposes of ornamentation, was known in the Stone Age, it is the melting and ] of copper that marks the end of the Stone Age.<ref>{{cite book |last=Goody |first=Jack |title=Metals, Culture, and Capitalism |date=2012}}</ref> In ], this occurred by about 3000 BC, when ] became widespread. The term ] is used to describe the period that followed the Stone Age, as well as to describe cultures that had developed techniques and technologies for working copper alloys (bronze: originally copper and arsenic, later copper and tin) into tools, supplanting stone in many uses. | |||

| ]s were made from a variety of different kinds of stone. For example, ] and ] were shaped (or '']'') for use as cutting tools and ]s, while ] and ] were used for ] tools, such as ]s. ], ], ], ] and other materials were widely used, too. During the most recent part of the period, ]s (like ]) were used to make ]. A series of metal ] innovations characterize the later ] (Copper Age), ], and ]. | |||

| Stone Age artifacts that have been discovered include tools used by modern humans, by their predecessor species in the ] '']'', and possibly by the earlier partly contemporaneous genera '']'' and '']''. ]s have been discovered that were used during this period as well but these are rarely preserved in the ]. The Stone Age is further subdivided by the types of ]s in use. | |||

| The period encompasses the first widespread use of ] in ] and the spread of ] from the ]s of ] to the rest of the ]. It ends with the development of ], the ] of certain animals and the ] of ] ] to produce metal. It is termed ''pre''historic, since humanity had not yet started ] -- the traditional start of ] (i.e., ]). | |||

| The Stone Age is the first period in the ] frequently used in ] to divide the timeline of human technological prehistory (especially in Europe and western Asia) into functional periods, with the next two being the ] and the ], respectively. The Stone Age is also commonly divided into three distinct periods: the earliest and most primitive being the ] era; a transitional period with finer tools known as the ] era; and the final stage known as the ] era. Neolithic peoples were the first to transition away from ] societies into the settled lifestyle of inhabiting ] as ]. In the chronology of prehistory, the Neolithic era usually overlaps with the ] ("Copper") era preceding the Bronze Age. | |||

| The term "Stone Age" was used by ] to designate this vast ] period whose stone ]s survived far more widely than tools made from other (softer) materials. It is the first age in the ] and was subdivided into the ], ], and ] periods, by ] in his now classic 1865 book ''Pre-historic Times''. These three periods are further subdivided. In reality, the succession of phases differs enormously from one ] (and ]) to another, indeed, humanity continued to expand into new areas even during the metal ages. Therefore, it is better to speak of ''a'' Stone Age, instead of ''the'' Stone Age. | |||

| The ] uses different markers to assign five periods which have different dates in different areas; the oldest period is the similarly named ]. | |||

| ==The Stone Age in archaeology== | |||

| {{TOC limit|4}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ==Historical significance== | |||

| The date range of this period is ambiguous, disputed, and variable according to the region in question. While it is possible to speak of a general 'stone age' period for the whole of humanity, some groups never developed metal-] technology, so remained in a 'stone age' until they encountered technologically developed cultures. However, in general, it is believed that this period began somewhere around 3 ], starting with the first ] tool-making in ]. Most ]s probably did not use stone tools (although they seem to be invented by ''] robustus'') but the study of their remains still falls within the remit of archaeologists studying the period. | |||

| ], Ethiopia, descendant of the Palaeo-Awash, source of the sediments in which the oldest Stone Age tools have been found]] | |||

| {{Human timeline}} | |||

| Due to the prevalence of stone ]s, which are frequently the only remains which still exist, ] is a major, and specialised, form of archaeological investigation for the period. This involves the measurement of the stone tools to determine their typology, function and the technology involved. This frequently involves an analysis of the ] of the raw materials, examining how the artefacts were actually made. This can also be examined through ], by attempting to create replica tools. This is done by ]s who reduce ]stone to a ]. | |||

| The Stone Age is contemporaneous with the evolution of the genus '']'', with the possible exception of the early Stone Age, when species prior to ''Homo'' may have manufactured tools.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Ko|first1=Kwang Hyun|title=Origins of human intelligence: The chain of tool-making and brain evolution|journal=Anthropological Notebooks|date=2016|volume=22|issue=1|pages=5–22|url=http://www.drustvo-antropologov.si/AN/PDF/2016_1/Anthropological_Notebooks_XXII_1_Ko.pdf}}</ref> According to the age and location of the current evidence, the cradle of the genus is the ] System, especially toward the north in ], where it is bordered by ]. The closest relative among the other living ]s, the genus '']'', represents a branch that continued on in the deep forest, where the primates evolved. The rift served as a conduit for movement into ] and also north down the ] into North Africa and through the continuation of the rift in the ] to the vast grasslands of Asia. | |||

| ===Modern use of the term=== | |||

| Starting from about 4 million years ago (]) a single ] established itself from South Africa through the rift, North Africa, and across Asia to modern China. This has been called "transcontinental 'savannahstan{{'"}} recently.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=106}}</ref> Starting in the grasslands of the rift, '']'', the predecessor of modern humans, found an ] as a tool-maker and developed a dependence on it, becoming a "tool-equipped ] dweller".<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=147}}</ref> | |||

| ]s]] | |||

| ==Stone Age in archaeology== | |||

| One problem with the term is that it implies that human advancement and time periods in prehistory are only measured by the type of tool material most widely used, rather than, for example, type of ], food sources exploited, or adaption to harsh ]s. This is a product of the level of knowledge of the distant past during the nineteenth century when the three age system was developed, a time when finds of ] were the main goal of an ]. Modern archaeological techniques stress a wider collection of information that has expanded our knowledge of prehistory and rendered neat divisions such as the term 'Stone Age' increasingly obsolete. We now know that the changes in past societies over the millennia were complex and involved multiple factors such as the adoption of ], ] or ] and that tool use is just one unrepresentative indicator of a society's practices and beliefs. | |||

| ===Beginning of the Stone Age=== | |||

| Another problem connected with the term Stone Age is that it was created to describe the ]s of ], and that it is inconvenient to use it in relation to regions such as some parts of the ] and ], where ] or ]s used stone for tools until European ] began. Metal-working was a much less important part of people's lives there and it is more useful to use other terms when dividing prehistory in those areas. The same incongruence applies to the Iron Age worldwide, because in the Americas iron (but not copper, ] or ]) was unknown until ], in Oceania until the ]. | |||

| ] ]]] | |||

| The oldest indirect evidence found of stone tool use is fossilised animal bones with tool marks; these are 3.4 million years old and were found in the Lower Awash Valley in Ethiopia.<ref name="nhm.ac.uk"/> Archaeological discoveries in Kenya in 2015, identifying what may be the oldest evidence of hominin use of tools known to date, have indicated that ''] platyops'' (a 3.2 to 3.5-million-year-old ] hominin fossil discovered in Lake Turkana, Kenya, in 1999) may have been the earliest tool-users known.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-32804177|title=Oldest tools pre-date first humans|first=Rebecca|last=Morelle|author-link=Rebecca Morelle|date=20 May 2015|work=BBC News}}</ref> | |||

| A Stone Age was usually followed by a ], during which ] technology allowed ] (copper and ] or other metals) tools to become more common. The transition out of the Stone Age occurred between ] and ] for much of humanity living in North Africa, Asia and Europe. In some regions, such as ], the Stone Age was followed directly by an ]. It is generally believed that the ] and ]n regions progressed past Stone Age technology around 6000 BC. ], and the rest of ] became post-Stone Age ] by about ]. The ] cultures of ] continued at a Stone Age level until around ], when gold, copper and silver made their entrance, the rest following later. Australia remained in the Stone Age until the 17th century. | |||

| The oldest stone tools were excavated from the site of ] 3 in West ], northwestern Kenya, and date to 3.3 million years old.<ref name="Harmand 2015">{{cite journal|last1=Harmand|first1=Sonia|title=3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya|journal=Nature|date=21 May 2015|volume=521|issue=7552|pages=310–315|doi=10.1038/nature14464|display-authors=etal|pmid=25993961|bibcode=2015Natur.521..310H|s2cid=1207285}}</ref> Prior to the discovery of these "Lomekwian" tools, the oldest known stone tools had been found at several sites at ], on sediments of the paleo-], which serve to date them. All the tools come from the Busidama Formation, which lies above a ], or missing layer, which would have been from 2.9 to 2.7 ]. The oldest sites discovered to contain tools are dated to 2.6–2.55 mya.<ref>{{harvnb|Rogers|Semaw|2009|pp=162–163}}</ref> One of the most striking circumstances about these sites is that they are from the Late ], where prior to their discovery tools were thought to have evolved only in the ]. Excavators at the locality point out that:<ref>{{harvnb|Rogers|Semaw|2009|p=155}}</ref> | |||

| We also now know that the transition from a Stone Age to a Bronze Age was not a neat switch but a long, gradual process involving the working of gold and copper at what are technically ] sites. This "transition" period is known as the Copper age or ]. It was a short and more a regional development, because alloying ] with copper began quite soon, except in regions lacking tin. ] for instance, a ] from about ] carried with him a copper axe and a flint knife. Stone tool manufacture also continued long into the succeeding metal-using ages, possibly even until the ]. In Europe and North America, ]s were in use until deep the 20th century, and still are in many parts of the world. | |||

| {{blockquote|... the earliest stone tool makers were skilled ] ... The possible reasons behind this seeming abrupt transition from the absence of stone tools to the presence thereof include ... gaps in the geological record.}} | |||

| ==Human development during the Stone Age== | |||

| The species that made the Pliocene tools remains unknown. Fragments of '']'', '']'',<ref>As to whether ''aethiopicus'' is the genus '']'' or the genus '']'', broken out to include the more robust forms, anthropological opinion is divided and both usages occur in the professional sources.</ref> and ''Homo'', possibly '']'', have been found in sites near the age of the Gona tools.<ref>{{harvnb|Rogers|Semaw|2009|p=164}}</ref> | |||

| The Stone Age covers an immense time span, and during this period major climatic and other changes occurred, which affected the evolution of humans. Humans themselves evolved into their current ] form during the later period of the Stone Age. | |||

| In July 2018, scientists reported the discovery in ] of the known oldest stone tools outside Africa, estimated at 2.12 million years old.<ref name="NYT-20180711cz">{{cite news |last=Zimmer |first=Carl |author-link=Carl Zimmer |title=Archaeologists in China Discover the Oldest Stone Tools Outside Africa |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/11/science/hominins-tools-china.html |date=11 July 2018 |work=] |access-date=13 July 2018 }}</ref> | |||

| ''See also: ]'' | |||

| === |

===End of the Stone Age=== | ||

| Innovation in the technique of ] ] is regarded as the end of the Stone Age and the beginning of the ]. The first highly significant metal manufactured was ], an alloy of copper and ] or ], each of which was smelted separately. The transition from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age was a period during which modern people could smelt copper, but did not yet manufacture bronze, a time known as the ] (or more technically the ] or Eneolithic, both meaning 'copper–stone'). The Chalcolithic by convention is the initial period of the Bronze Age. The Bronze Age was followed by the ]. | |||

| The ] period runs from about 2 million years ago to the end of the ], 10,000 years ago. For areas with an early ], the Palaeolithic includes the ], and ends around 8,000 years ago. | |||

| The transition out of the Stone Age occurred between 6000 and 2500 ] for much of humanity living in ] and ].{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| ====Lower Palaeolithic==== | |||

| {{main|Lower Palaeolithic}} | |||

| Near the end of the ] ] in Africa, an early ancestor of modern humans, called '']'', developed the earliest known stone tools. These were relatively simple tools known as ]. ''Homo habilis'' is presumed to have mastered the ] era tool case which utilized stone ] and ]. This ] of stone tools is named after the site of ] in ]. These humans likely subsisted on scavenged meat and wild plants, rather than hunted ]. Around 1.5 million years ago, a more evolved human species, '']'', appeared. ''H. erectus'' learnt to control fire and created more complex chopper tools, as well as expanding ] to reach Asia, as shown by sites such as ] in ]. By 1 million years ago, the earliest evidence of humans in Europe is known, as well use of the more advanced ] tool. | |||

| The first evidence of human ] dates to between the ] and ] BC in the archaeological sites of the ], including ], ], ], ] in modern-day Serbia.<ref>{{cite journal | journal = ] | year = 2021 | issue = 2 | title = Early Balkan Metallurgy: Origins, Evolution and Society, 6200–3700 BC | first1 = Miljana | last1 = Radivojević | first2 = Benjamin W. | last2 = Roberts | volume = 34 | pages = 195–278 | doi = 10.1007/s10963-021-09155-7 | s2cid = 237005605 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ====Middle Palaeolithic==== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Middle Palaeolithic}} | |||

| This period began about 200,000 years ago and is most well-known as being the era during which the ]s lived (c. 120,000–35,000 years ago). The stone artefact technology of the Neanderthals is generally known as the ]. The Neanderthals eventually disappeared from the archaeological record, replaced by modern humans who first appeared in southern Africa around 100,000 years ago. Although often identified in the public's mind as primitive, there is evidence that Neanderthals nursed their elderly and practised ] burial indicating an organised society. The earliest evidence of settlement in ] dates ] when modern humans likely crossed from Asia by hopping from island to island. Middle Palaeolithic peoples demonstrate the earliest evidence for ] and other expressions of abstract thought such as ] body decoration. | |||

| ], a ] from about 3300 BC, carried with him a copper axe and a flint knife. | |||

| ====Upper Palaeolithic==== | |||

| ] of ] is an example of Upper Palaeolithic culture]] | |||

| {{main|Upper Palaeolithic}} | |||

| From 35,000 to 10,000 years ago (the end of the ]) modern humans spread out further across the ] during the period known as the Upper Palaeolithic. | |||

| <!--this happened earlier-->After the arrival of the first modern humans (]s) in Europe a relatively rapid succession of often complex stone artefact technologies took place during this period, including the ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| In some regions, such as ], the Stone Age was followed directly by the Iron Age.<ref>{{cite book|author1=S.J.S. Cookey|editor1-last=Swartz|editor1-first=B.K.|editor2-last=Dumett|editor2-first=Raymond E.|title=West African Culture Dynamics: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives|date=1980|publisher=Mouton de Gruyter|isbn=978-90-279-7920-9|page=329|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8_Z5N0gmNlsC&q=africa+Stone+Age+was+followed+directly+by+the+iron+age&pg=PA329|access-date=3 June 2016|chapter=An Ethnohistorical Reconstruction of Traditional Igbo Society}}</ref> The Middle East and ]n regions progressed past Stone Age technology around 6000 BC.{{citation needed|date=January 2016}} Europe, and the rest of Asia became post-Stone Age societies by about 4000 BC.{{citation needed|date=January 2016}} The ] cultures of South America continued at a Stone Age level until around 2000 BC, when gold, copper, and silver made their entrance. The peoples of the Americas notably did not develop a widespread behavior of smelting bronze or iron after the Stone Age period, although the technology existed.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Easby|first1=Dudley T.|title=Pre-Hispanic Metallurgy and Metalworking in the New World|journal=Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society|date=April 1965|volume=109|issue=2|pages=89–98}}</ref> Stone tool manufacture continued even after the Stone Age ended in a given area. In Europe and North America, ]s were in use until well into the 20th century, and still are in many parts of the world. | |||

| The Americas were colonised via the ] which was exposed during this period by lower sea levels. These people are called the ], and the earliest accepted dates are those of the ] sites, some 13,500 years ago. Globally, societies were ]s but evidence of regional identities begins to appear in the wide variety of stone tool types being developed to suit different environments. | |||

| ===Concept of the Stone Age=== | |||

| ===Epipalaeolithic/Mesolithic=== | |||

| The terms "Stone Age", "Bronze Age", and "Iron Age" are not intended to suggest that advancements and time periods in prehistory are only measured by the type of tool material, rather than, for example, ], ] exploited, adaptation to climate, adoption of agriculture, cooking, ], and religion. Like ], the typology of the stone tools combined with the relative sequence of the types in various regions provide a chronological framework for the evolution of humanity and society. They serve as diagnostics of date, rather than characterizing the people or the society. | |||

| ''Main articles: ], ]'' | |||

| ] | |||

| The period between the end of the last ice age, 10,000 years ago to around 6,000 years ago, is characterised by rising sea levels and a need to adapt to a changing environment and find new food sources. The development of ] tools began in response to these changes. They were derived from the previous Palaeolithic tools, hence the term Epipalaeolithic. However, in Europe the term ] (Middle Stone Age) is used, as the tools (and way of life) was imported from the ]. There, microlith tools permitted more efficient hunting, while more complex settlements, such as ] developed based around fishing. Domestication of the ] as a hunting companion probably dates to this period. | |||

| ] is a major and specialised form of archaeological investigation. It involves the measurement of ]s to determine their typology, function and technologies involved. It includes the scientific study of the ] of the raw materials and methods used to make the prehistoric artifacts that are discovered. Much of this study takes place in the laboratory in the presence of various specialists. In ], researchers attempt to create replica tools, to understand how they were made. ]s are craftsmen who use sharp tools to reduce ]stone to ]. | |||

| ===Neolithic=== | |||

| ] pottery is the oldest in the world.]] | |||

| {{main|Neolithic}} | |||

| The Neolithic (New Stone Age) is characterised by the adoption of ] (the so-called ]), the development of ] and more complex, larger settlements such as ] and ]. The first Neolithic cultures started around ] in the ]. Agriculture and the culture it led to spread to the ], the ], China, and ]. | |||

| ]s]] | |||

| Due to the increased need to harvest and process plants, ground stone and polished stone artefacts became much more widespread, including tools for grinding, cutting, chopping and adzing. The first large-scale constructions were built, including settlement towers and walls (e.g., Jericho) and ceremonial sites (e.g., ]). These show that there was sufficient resources and co-operation to enable large groups to work on these projects. To what extent this was the development of elites and social hierarchies is a matter of on-going debate. The earliest evidence for established ] exists in the Neolithic with newly settled people importing exotic goods over distances of many hundreds of miles. | |||

| In addition to lithic analysis, field prehistorians use a wide range of techniques derived from multiple fields. The work of archaeologists in determining the paleocontext and relative sequence of the layers is supplemented by the efforts of geologic specialists in identifying layers of rock developed or deposited over geologic time; of paleontological specialists in identifying bones and animals; of palynologists in discovering and identifying pollen, spores and plant species; of physicists and chemists in laboratories determining ages of materials by ], ] and other methods. The study of the Stone Age has never been limited to stone tools and archaeology, even though they are important forms of evidence. The chief focus of study has always been on the society and the living people who belonged to it. | |||

| ==Stone Age material culture== | |||

| Useful as it has been, the concept of the Stone Age has its limitations. The date range of this period is ambiguous, disputed, and variable, depending upon the region in question. While it is possible to speak of a general 'Stone Age' period for the whole of humanity, some groups never developed metal-] technology, and so remained in the so-called 'Stone Age' until they encountered technologically developed cultures. The term was innovated to describe the ]s of Europe. It may not always be the best in relation to regions such as some parts of the ] and Oceania, where ] or ]s used stone for tools until European ] began. | |||

| ===Food and drink=== | |||

| ] of the ] humans of the Stone Age included both animals and plants that were part of the ] in which these humans lived. These humans liked animal ] meats, including the ], ]s, and ]s. They consumed little ] or ]-rich plant foods like ]s or ]s. | |||

| ] engraved with human face found from ], ]<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.finna.fi/Record/musketti.M012:AKD32380:1#image|title=KM 11708 Kiuruveden kirves; Esinekuva|via=finna.fi|language=fi|access-date=2022-08-21}}</ref>]] | |||

| Current research indicates that two-thirds of the energy was derived from animal foods.{{ref|Diet}} The fat content of the diet was believed to be similar to that of the present day, but the ratio of the types of fats consumed differed: the ] to ] ratio was about 3:1 compared to 12:1 of today. | |||

| Archaeologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries CE, who adapted the ] to their ideas, hoped to combine cultural anthropology and archaeology in such a way that a specific contemporaneous tribe could be used to illustrate the way of life and beliefs of the people exercising a particular Stone-Age technology. As a description of people living today, the term ''Stone Age'' is controversial. The ] discourages this use, asserting:<ref>{{cite news | title=ASA Statement on the use of 'primitive' as a descriptor of contemporary human groups | newspaper=ASA News | date=27 August 2007 | publisher=Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth | url=http://www.theasa.org/news.shtml#asa | access-date=31 October 2011 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111114155909/http://www.theasa.org/news.shtml#asa | archive-date=14 November 2011 | url-status=dead | df=dmy-all }}</ref><blockquote>To describe any living group as 'primitive' or 'Stone Age' inevitably implies that they are living representatives of some earlier stage of human development that the majority of humankind has left behind.</blockquote> | |||

| Near the end of the ], 15,000 to 9,000 years ago, a large scale ] of large ]s (the ]) occurred in Asia, Europe, ] and Australia. This was the first ]. This event possibly forced modification in the dietary habits of the humans of that age and with the emergence of ], plant-based foods also became a regular part of the diet. | |||

| ===Three-stage system=== | |||

| A report in the National Geographic News indicated that "the first ] may have occurred when Neolithic humans slurped the juice of naturally ] ] from animal-skin pouches or crude wooden ]s."{{ref|wine}} | |||

| In the 1920s, South African archaeologists organizing the stone tool collections of that country observed that they did not fit the newly detailed Three-Age System. In the words of ]:<ref>{{harvnb|Clark|1970|p=22}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>It was early realized that the threefold division of culture into Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages adopted in the nineteenth century for Europe had no validity in Africa outside the Nile valley.</blockquote> | |||

| ===Shelters and habitats=== | |||

| Around 2 million years before present, ''Homo habilis'' is believed to have constructed first man-made structure in ], consisting of simple arrangements of stones to hold branches of trees in position. Almost similar stone arrangements in circle believed to be around 500,000 years old was discovered at ], near ] (]). Several human habitats dating back to the Stone Age have been discovered in different parts of the earth, including: | |||

| Consequently, they proposed a new system for Africa, the Three-stage System. Clark regarded the Three-age System as valid for North Africa; in sub-Saharan Africa, the Three-stage System was best.<ref>{{harvnb|Clark|1970|pp=18–19}}</ref> In practice, the failure of African archaeologists either to keep this distinction in mind, or to explain which one they mean, contributes to the considerable equivocation already present in the literature. There are in effect two Stone Ages, one part of the Three-age and the other constituting the Three-stage. They refer to one and the same artifacts and the same technologies, but vary by locality and time. | |||

| *A tent-like structure inside a cave near the ] , Nice, France. | |||

| *A structure with roof supported with timber, discovered in ], ], dates to around 23,000 BC. The walls were made of packed clay blocks and stones. | |||

| The three-stage system was proposed in 1929 by Astley John Hilary Goodwin, a professional archaeologist, and ], a civil engineer and amateur archaeologist, in an article titled "Stone Age Cultures of South Africa" in the journal ''Annals of the South African Museum''. By then, the dates of the Early Stone Age, or ], and Late Stone Age, or ] (''neo'' = new), were fairly solid and were regarded by Goodwin as absolute. He therefore proposed a relative chronology of periods with floating dates, to be called the Earlier and Later Stone Age. The Middle Stone Age would not change its name, but it would not mean ].<ref>{{harvnb|Deacon|Deacon|1999|pp=5–6}}</ref> | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| *Many huts made of ] bones were found in Eastern Europe and Siberia. The people who made these huts were specialised mammoth hunters. Examples have been found along the ] river valley of ], including near ], in ] (in the ]) and in southern ]. | |||

| The duo thus reinvented the Stone Age. In Sub-Saharan Africa, however, iron-working technologies were either invented independently or came across the Sahara from the north (see '']''). The Neolithic was characterized primarily by herding societies rather than large agricultural societies, and although there was ] as well as bronze smelting, archaeologists do not currently recognize a separate Copper Age or Bronze Age. Moreover, the technologies included in those 'stages', as Goodwin called them, were not exactly the same. Since then, the original relative terms have become identified with the technologies of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, so that they are no longer relative. Moreover, there has been a tendency to drop the comparative degree in favor of the positive: resulting in two sets of Early, Middle and Late Stone Ages of quite different content and chronologies. | |||

| *An animal hide tent dated to around 15,000 to 10,000 BC (in the ]) was discovered at ], France. | |||

| *]s, multi-chambered, and ]s, single-chambered, were ] with a huge stone slab stacked over other similarly large stone slabs. They have been discovered all across Europe, and were built in the Neolithic. Several tombs with copper and bronze tools have also been discovered, illustrating the problems of attempting to define periods based on technology. | |||

| By voluntary agreement,{{citation needed|reason=what does this even mean? Which archeologists? What did they agree to? Why? This is very dubious sounding without a good source|date=December 2018}} archaeologists respect the decisions of the ], which meets every four years to resolve the archaeological business brought before it. Delegates are actually international; the organization takes its name from the topic.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Arnott|first=D. W.|date=June 1959|title=J. Desmond Clark and Sonia Cole (ed.): Third Pan-African Congress on Prehistory, Livingstone, 1955. xxxix, 440 pp., 7 col. plates. London: Chatto & Windus, 1957. 75s.|journal=Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies|language=en|volume=22|issue=2|pages=400|doi=10.1017/S0041977X00069135|s2cid=162906190|issn=1474-0699}}</ref> ] hosted the first one in ] in 1947. It adopted Goodwin and Lowe's 3-stage system at that time, the stages to be called Early, Middle and Later. | |||

| ===Problem of the transitions=== | |||

| The problem of the transitions in archaeology is a branch of the general philosophic continuity problem, which examines how discrete objects of any sort that are ] in any way can be presumed to have a relationship of any sort. In archaeology, the relationship is one of ]. If Period B can be presumed to descend from Period A, there must be a boundary between A and B, the A–B boundary. The problem is in the nature of this boundary. If there is no distinct boundary, then the population of A suddenly stopped using the customs characteristic of A and suddenly started using those of B, an unlikely scenario in the process of ]. More realistically, a distinct border period, the A/B transition, existed, in which the customs of A were gradually dropped and those of B acquired. If transitions do not exist, then there is no proof of any continuity between A and B. | |||

| The Stone Age of Europe is characteristically in deficit of known transitions. The 19th and early 20th-century innovators of the modern ] recognized the problem of the initial transition, the "gap" between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. ] provided something of an answer by proving that man evolved in Africa. The Stone Age must have begun there to be carried repeatedly to Europe by migrant populations. The different phases of the Stone Age thus could appear there without transitions. The burden on African archaeologists became all the greater, because now they must find the missing transitions in Africa. The problem is difficult and ongoing. | |||

| After its adoption by the First Pan African Congress in 1947, the Three-Stage Chronology was amended by the Third Congress in 1955 to include a First Intermediate Period between Early and Middle, to encompass the ] and ] technologies, and the Second Intermediate Period between Middle and Later, to encompass the ] technology and others. The chronologic basis for the definition was entirely relative. With the arrival of scientific means of finding an absolute chronology, the two intermediates turned out to be ]s. They were in fact ] and ]. Fauresmith is now considered to be a ] of ], while Sangoan is a facies of ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | first=Glynn | last=Isaac | author-link=Glynn Isaac | title=The Earliest Archaeological Traces | editor-first=J. Desmond | series=Volume | editor-last=Clark | encyclopedia=The Cambridge History of Africa | volume=I: From the Earliest Times to C. 500 BC | page=246 | location=Cambridge | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1982 }}</ref> Magosian is "an artificial mix of two different periods".<ref>{{cite book | last=Willoughby | first=Pamela R. | year=2007 | title=The evolution of modern humans in Africa: a comprehensive guide | location=Lanham, Maryland | publisher=AltaMira Press | page=54}}</ref> | |||

| Once seriously questioned, the intermediates did not wait for the next Pan African Congress two years hence, but were officially rejected in 1965 (again on an advisory basis) by Burg Wartenstein Conference #29, ''Systematic Investigation of the African Later Tertiary and Quaternary'',<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=477}}</ref> a conference in anthropology held by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, at Burg Wartenstein Castle, which it then owned in Austria, attended by the same scholars that attended the Pan African Congress, including Louis Leakey and ], who was delivering a pilot presentation of her typological analysis of Early Stone Age tools, to be included in her 1971 contribution to ''Olduvai Gorge'', "Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960–1963."<ref>{{cite web | title=History: Systematic Investigation of the African Later Tertiary and Quaternary | url=http://wennergren.org/history/conferences-seminars-symposia/wenner-gren-symposia/cumulative-list-wenner-gren-symposia/we-23 | publisher=The Wenner-Gren Foundation | access-date=3 March 2011 | archive-date=28 July 2011 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110728172827/http://wennergren.org/history/conferences-seminars-symposia/wenner-gren-symposia/cumulative-list-wenner-gren-symposia/we-23 | url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| However, although the intermediate periods were gone, the search for the transitions continued. | |||

| ==Chronology== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1859 ] first proposed a division of the Stone Age into older and younger parts based on his work with Danish ]s that began in 1851.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | title=Worsaae, Jens Jacob Asmussen | encyclopedia=] }}</ref> In the subsequent decades this simple distinction developed into the archaeological periods of today. The major subdivisions of the Three-age Stone Age cross two ] boundaries on the ]: | |||

| * The geologic ]–] boundary (highly glaciated climate) | |||

| ** The ] period of archaeology | |||

| * The geologic ]–] boundary (modern climate) | |||

| ** ] or ] period of archaeology | |||

| ** ] period of archaeology | |||

| The succession of these phases varies enormously from one region (and ]) to another. | |||

| ===Three-age chronology=== | |||

| {{Main|Paleolithic|Human evolution|Three-age system}} | |||

| The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (from Greek: παλαιός, ''palaios'', "old"; and λίθος, '']'', "stone" lit. "old stone", coined by archaeologist ] and published in 1865) is the earliest division of the Stone Age. It covers the greatest portion of humanity's time (roughly 99% of "human technological history",<ref name=Thoth&Schick>{{Cite book |title=Handbook of Paleoanthropology | first1=Nicholas | last1=Toth |series=Volume | first2=Kathy | last2=Schick | year=2007 | volume=3 | contribution=21 Overview of Paleolithic Archaeology | editor-first=H.C. Winfried | editor-last=Henke | editor2-first=Thorolf | editor2-last=Hardt | editor3-first=Ian | editor3-last=Tattersall | location=Berlin; Heidelberg; New York | publisher=Springer-Verlag |isbn=978-3-540-32474-4 | page=1944 |doi=10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_64 }}</ref> where "human" and "humanity" are interpreted to mean the genus '']''), extending from 2.5 or 2.6 million years ago, with the first documented use of stone tools by ]s such as '']'', to the end of the ] around 10,000 BC.<ref name="Thoth&Schick"/> The Paleolithic era ended with the ], or in areas with an early ], the ]. | |||

| ====Lower Paleolithic==== | |||

| {{main|Lower Paleolithic}} | |||

| At sites dating from the Lower Paleolithic Period (about 2,500,000 to 200,000 years ago), simple pebble tools have been found in association with the remains of what may have been the earliest human ancestors. A somewhat more sophisticated Lower Paleolithic tradition, known as the ] industry, is widely distributed in the Eastern Hemisphere. This tradition is thought to have been the work of the hominin species named '']''. Although no such fossil tools have yet been found, it is believed that ''H. erectus'' probably made tools of wood and bone as well as stone. | |||

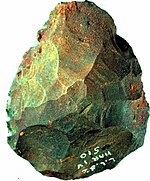

| About 700,000 years ago, a new Lower Paleolithic tool, the hand axe, appeared. The earliest European hand axes are assigned to the ], which developed in northern France in the valley of the ]; a later, more refined hand-axe tradition is seen in the ], evidence of which has been found in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Some of the earliest known hand axes were found at ] (Tanzania) in association with remains of ''H. erectus''. Alongside the hand-axe tradition, there developed a distinct and very different stone-tool industry, based on flakes of stone: special tools were made from worked (carefully shaped) flakes of flint. In Europe, the ] is one example of a flake tradition. The early flake industries probably contributed to the development of the ] flake tools of the ], which is associated with the remains of ].<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/439507/Paleolithic-Period | title=Paleolithic Period | Definition, Dates, & Facts| date=7 August 2023}}</ref> | |||

| =====Oldowan in Africa===== | |||

| {{Main|Oldowan}} | |||

| ] from the western Sahara]] | |||

| The earliest documented ]s have been found in eastern Africa, manufacturers unknown, at the 3.3 million-year-old site of Lomekwi 3 in Kenya.<ref name="Harmand 2015" /> Better known are the later tools belonging to an ] known as ], after the type site of ] in Tanzania. | |||

| The tools were formed by knocking pieces off a river pebble, or stones like it, with a hammerstone to obtain large and small pieces with one or more sharp edges. The original stone is called a core; the resultant pieces, flakes. Typically, but not necessarily, small pieces are detached from a larger piece, in which case the larger piece may be called the ] and the smaller pieces the ]. The prevalent usage, however, is to call all the results flakes, which can be confusing. A split in half is called bipolar flaking. | |||

| Consequently, the method is often called "core-and-flake". More recently, the tradition has been called "small flake" since the flakes were small compared to subsequent ].<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=130}}.</ref> | |||

| {{quote|The essence of the Oldowan is the making and often immediate use of small flakes.{{attribution needed|date=October 2024}}}} | |||

| Another naming scheme is "Pebble Core Technology (PBC)":<ref>{{harvnb|Shea|2010|p=49}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|Pebble cores are ... artifacts that have been shaped by varying amounts of hard-hammer percussion.{{attribution needed|date=October 2024}}}} | |||

| Various refinements in the shape have been called choppers, discoids, polyhedrons, subspheroid, etc. To date no reasons for the variants have been ascertained:<ref name=Shea50>{{harvnb|Shea|2010|p=50}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|From a functional standpoint, pebble cores seem designed for no specific purpose.{{attribution needed|date=October 2024}}}} | |||

| However, they would not have been manufactured for no purpose:<ref name=Shea50/> | |||

| {{quote|Pebble cores can be useful in many cutting, scraping or chopping tasks, but ... they are not particularly more efficient in such tasks than a sharp-edged rock.{{attribution needed|date=October 2024}}}} | |||

| The whole point of their utility is that each is a "sharp-edged rock" in locations where nature has not provided any. There is additional evidence that Oldowan, or Mode 1, tools were used in "percussion technology"; that is, they were designed to be gripped at the blunt end and strike something with the edge, from which use they were given the name of ]. Modern science has been able to detect mammalian blood cells on Mode 1 tools at ], Member 5 East, in South Africa. As the blood must have come from a fresh kill, the tool users are likely to have done the killing and used the tools for butchering. Plant residues bonded to the ] of some tools confirm the use to chop plants.<ref name="Barham 2008 132">{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=132}}</ref> | |||

| Although the exact species authoring the tools remains unknown, Mode 1 tools in Africa were manufactured and used predominantly by '']''. They cannot be said to have developed these tools or to have contributed the tradition to technology. They continued a tradition of yet unknown origin. As ]s sometimes naturally use percussion to extract or prepare food in the wild, and may use either unmodified stones or stones that they have split, creating an Oldowan tool, the tradition may well be far older than its current record.{{citation needed|reason=Original Research?|date=November 2015}} | |||

| Towards the end of Oldowan in Africa the new species ''Homo erectus'' appeared over the range of ''Homo habilis''. The earliest "unambiguous" evidence is a whole ], KNM-ER 3733 (a find identifier) from ] in Kenya, dated to 1.78 mya.<ref name=B&M126-127>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|pp=126–127}}.</ref> An early skull fragment, KNM-ER 2598, dated to 1.9 mya, is considered a good candidate also.<ref name=B&M128>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=128}}</ref> Transitions in paleoanthropology are always hard to find, if not impossible, but based on the "long-legged" ] shared by ''H. habilis'' and '']'' in East Africa, an evolution from one of those two has been suggested.<ref name=B&M145>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=145}}</ref> | |||

| The most immediate cause of the new adjustments appears to have been an increasing aridity in the region and consequent contraction of parkland ], interspersed with trees and groves, in favor of open grassland, dated 1.8–1.7 mya. During that transitional period the percentage of grazers among the fossil species increased from around 15–25% to 45%, dispersing the food supply and requiring a facility among the hunters to travel longer distances comfortably, which ''H. erectus'' obviously had.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=146}}.</ref> The ultimate proof is the "dispersal" of ''H. erectus'' "across much of Africa and Asia, substantially before the development of the Mode 2 technology and use of fire".<ref name=B&M145/> ''H. erectus'' carried Mode 1 tools over Eurasia. | |||

| According to the current evidence (which may change at any time) Mode 1 tools are documented from about 2.6 mya to about 1.5 mya in Africa,<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=112}}</ref> and to 0.5 mya outside of it.<ref>{{harvnb|Shea|2010|p=57}}</ref> The genus Homo is known from ''H. habilis'' and ''H. rudolfensis'' from 2.3 to 2.0 mya, with the latest habilis being an upper jaw from Koobi Fora, Kenya, from 1.4 mya. ''H. erectus'' is dated 1.8–0.6 mya.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=73}}</ref> <!--Tool manufacture is not species-specific: It had been an early Leakey hypothesis at Olduvai that Mode 1 tools implied ''Homo habilis'' and Mode 2, ''Homo erectus''. Subsequent methods of obtaining more precise dates made that hypothesis at least partially obsolete.<ref name=B&M126-127>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|pp=126–127}}.</ref>--> | |||

| According to this chronology Mode 1 was inherited by ''Homo'' from unknown ], probably '']'' and '']'', who must have continued on with Mode 1 and then with Mode 2 until their extinction no later than 1.1 mya. Meanwhile, living contemporaneously in the same regions ''H. habilis'' inherited the tools around 2.3 mya. At about 1.9 mya ''H. erectus'' came on stage and lived contemporaneously with the others. Mode 1 was now being shared by a number of Hominans over the same ranges, presumably subsisting in different niches, but the archaeology is not precise enough to say which. | |||

| =====Oldowan out of Africa===== | |||

| Tools of the Oldowan tradition first came to archaeological attention in Europe, where, being intrusive and not well defined, compared to the Acheulean, they were puzzling to archaeologists. The mystery would be elucidated by African archaeology at Olduvai, but meanwhile, in the early 20th century, the term "Pre-Acheulean" came into use in ]. C. E. P. Brooks, a British climatologist working in the United States, used the term to describe a "chalky boulder clay" underlying a layer of gravel at ], central England, where Acheulean tools had been found.<ref>{{citation | first=Charles E. P. |last=Brooks | contribution=The Correlation of the Quaternary Deposits of the British Isles with Those of the Continent of Europe | title=Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution 1917 | year=1919 | location=Washington | publisher=Government Pronting Office | page=277}}</ref> Whether any tools would be found in it and what type was not known. ], a contemporary German archaeologist working in Spain, stated:<!--previously "quipped" which implies humour, but this is not humorous--> | |||

| {{quote|Unfortunately, the stage of human industry which corresponds to these deposits cannot be positively identified. All we can say is that it is pre-Acheulean.}} | |||

| This uncertainty was clarified by the subsequent excavations at Olduvai; nevertheless, the term is still in use for pre-Acheulean contexts, mainly across Eurasia, that are yet unspecified or uncertain but with the understanding that they are or will turn out to be pebble-tool.<ref>{{cite book | first=Hugo |last=Obermaier | author-link=Hugo Obermaier |author2=Christine Matthew |author3=Henry Osborne | title=Fossil Man in Spain | location=New Haven | publisher=Yale University Press for the Hispanic Society of America | year=1924 | page=272}}</ref> | |||

| There are ample associations of Mode 2 with ''H. erectus'' in Eurasia. ''H. erectus'' – Mode 1 associations are scantier but they do exist, especially in the Far East. One strong piece of evidence prevents the conclusion that only ''H. erectus'' reached Eurasia: at ], Israel, Mode 1 tools have been found dating to 2.4 mya,<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|pp=106–107}}</ref> about 0.5 my earlier than the known ''H. erectus'' finds. If the date is correct, either another Hominan preceded ''H. erectus'' out of Africa or the earliest ''H. erectus'' has yet to be found. | |||

| After the initial appearance at Gona in Ethiopia at 2.7 mya, pebble tools date from 2.0 mya at ], Member 5, South Africa, and from 1.8 mya at El Kherba, Algeria, North Africa. The manufacturers had already left pebble tools at ], Israel, at 2.4 mya, ], Pakistan, at 2.0 mya, and Renzidong, South China, at over 2 mya.<ref name=Shea55-57>{{harvnb|Shea|2010|pp=55–57}}</ref> The identification of a fossil skull at Mojokerta, Pernung Peninsula on ], dated to 1.8 mya, as ''H. erectus'', suggests that the African finds are not the earliest to be found in Africa, or that, in fact, erectus did not originate in Africa after all but on the plains of Asia.<ref name=B&M145/> The outcome of the issue waits for more substantial evidence. Erectus was found also at ], Georgia, from 1.75 mya in association with pebble tools. | |||

| Pebble tools are found the latest first in southern Europe and then in northern Europe. They begin in the open areas of Italy and Spain, the earliest dated to 1.6 mya at Pirro Nord, Italy. The mountains of Italy are rising at a rapid rate in the framework of geologic time; at 1.6 mya they were lower and covered with grassland (as much of the highlands still are). Europe was otherwise mountainous and covered over with dense forest, a formidable terrain for warm-weather savanna dwellers. Similarly there is no evidence that the Mediterranean was passable at Gibraltar or anywhere else to ''H. erectus'' or earlier hominins. They might have reached Italy and Spain along the coasts. | |||

| In northern Europe, pebble tools are found earliest at ], United Kingdom, from 0.8 mya. The last traces are from ], dated 0.5 mya. By that time ''H. erectus'' is regarded as having been extinct; however, a more modern version apparently had evolved, '']'', who must have inherited the tools.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=24}}</ref> He{{who?|date=October 2024}} also explains the last of the Acheulean in Germany at 0.4 mya. | |||

| In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, archaeologists worked on the assumption that a succession of hominins and cultures prevailed, that one replaced another. Today the presence of multiple hominins living contemporaneously near each other for long periods is accepted as proven true; moreover, by the time the previously assumed "earliest" culture arrived in northern Europe, the rest of Africa and Eurasia had progressed to the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, so that across the earth all three were for a time contemporaneous. In any given region there was a progression from Oldowan to Acheulean, Lower to Upper, no doubt. | |||

| =====Acheulean in Africa===== | |||

| {{Main|Acheulean}} | |||

| ] tool, not worked over the entire surface]] | |||

| The end of Oldowan in Africa was brought on by the appearance of ], or Mode 2, ]s. The earliest known instances are in the 1.7–1.6 mya layer at ], West Turkana, Kenya.<ref name=B&M128/> At ], South Africa, they are in Member 5 West, 1.7–1.4 mya.<ref name="Barham 2008 132"/> The 1.7 is a fairly certain, fairly standard date. Mode 2 is often found in association with ''H. erectus''. It makes sense that the most advanced tools should have been innovated by the most advanced hominin; consequently, they are typically given credit for the innovation. | |||

| A Mode 2 tool is a biface consisting of two concave surfaces intersecting to form a cutting edge all the way around, except in the case of tools intended to feature a point. More work and planning go into the manufacture of a Mode 2 tool. The manufacturer hits a slab off a larger rock to use as a blank. Then large flakes are struck off the blank and worked into bifaces by hard-hammer percussion on an anvil stone. Finally the edge is retouched: small flakes are hit off with a bone or wood soft hammer to sharpen or resharpen it. The core can be either the blank or another flake. Blanks are ported for manufacturing supply in places where nature has provided no suitable stone. | |||

| Although most Mode 2 tools are easily distinguished from Mode 1, there is a close similarity of some Oldowan and some Acheulean, which can lead to confusion. Some Oldowan tools are more carefully prepared to form a more regular edge. One distinguishing criterion is the size of the flakes. In contrast to the Oldowan "small flake" tradition, Acheulean is "large flake": "The primary technological distinction remaining between Oldowan and the Acheulean is the preference for large flakes (>10 cm) as blanks for making large cutting tools (handaxes and cleavers) in the Acheulean."<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=130}}</ref> "Large Cutting Tool" (LCT) has become part of the standard terminology as well.<ref name="Shea50"/> | |||

| In North Africa, the presence of Mode 2 remains a mystery, as the oldest finds are from Thomas Quarry in ] at 0.9 mya.<ref name=Shea55-57/> Archaeological attention, however, shifts to the Jordan Rift Valley, an extension of the East African Rift Valley (the east bank of the Jordan is slowly sliding northward as East Africa is thrust away from Africa). Evidence of use of the Nile Valley is in deficit, but Hominans could easily have reached the palaeo-] from ] along the shores of the ], one side or the other. A crossing would not have been necessary, but it is more likely there than over a theoretical but unproven land bridge through either ] or ]. | |||

| Meanwhile, Acheulean went on in Africa past the 1.0 mya mark and also past the extinction of ''H. erectus'' there. The last Acheulean in East Africa is at ], Kenya, dated to about 0.9 mya. Its owner was still ''H. erectus'',<ref name=Shea55-57/> but in South Africa, Acheulean at ], 1.0–0.6 mya, is associated with ], classified as ''H. heidelbergensis'', a more advanced, but not yet modern, descendant most likely of ''H. erectus''. The Thoman Quarry Hominans in ] similarly are most likely ],<ref>{{cite journal | journal=Quaternary International | issue=223–224 | year=2010 | pages=369–382 | title=Hominid Cave at Thomas Quarry I (Casablanca, Morocco): Recent findings and their context | author=Jean-Paul Raynal | url=http://www.eva.mpg.de/evolution/staff/hublin/pdf/Raynal%20et%20al%202010%20Quat%20Intl.pdf | display-authors=etal | doi=10.1016/j.quaint.2010.03.011 | volume=223–224 | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110228231758/http://www.eva.mpg.de/evolution/staff/hublin/pdf/Raynal%20et%20al%202010%20Quat%20Intl.pdf | archive-date=28 February 2011 | df=dmy-all | bibcode=2010QuInt.223..369R }}</ref> in the same evolutionary status as ''H. heidelbergensis''. | |||

| <!--''H. erectus'' learned to control fire and created more complex chopper tools, as well as expanding ] to reach Asia, as shown by sites such as ] in China. By 1 million years ago, the earliest evidence of humans in Europe is known, as well as use of the more advanced ] tool.--> | |||

| =====Acheulean out of Africa===== | |||

| Mode 2 is first known out of Africa at '], Israel, a site now on the ], then frequented over the long term (hundreds of thousands of years) by ] on the shore of a variable-level palaeo-lake, long since vanished. The geology was created by successive "transgression and regression" of the lake<ref>{{harvnb|Belmaker|2006|p=9}}</ref> resulting in four cycles of layers. The tools are located in the first two, Cycles Li (Limnic Inferior) and Fi (Fluviatile Inferior), but mostly in Fi. The cycles represent different ecologies and therefore different cross-sections of fauna, which makes it possible to date them. They appear to be the same faunal assemblages as the Ferenta Faunal Unit in Italy, known from excavations at Selvella and Pieterfitta, dated to 1.6–1.2 mya.<ref>{{harvnb|Belmaker|2006|pp=119–120}}</ref> | |||

| At 'Ubeidiya the marks on the bones of the animal species found there indicate that the manufacturers of the tools butchered the kills of large predators, an activity that has been termed "scavenging".<ref>{{harvnb|Belmaker|2006|p=149}}</ref> There are no living floors, nor did they process bones to obtain the marrow. These activities cannot be understood therefore as the only or even the typical economic activity of Hominans. Their interests were selective: they were primarily harvesting the meat of ]s,<ref>{{harvnb|Belmaker|2006|p=147}}</ref> which is estimated to have been available without spoiling for up to four days after the kill. | |||

| The majority of the animals at the site were of "Palaearctic biogeographic origin".<ref>{{harvnb|Belmaker|2006|p=67}}</ref> However, these overlapped in range on 30–60% of "African biogeographic origin".<ref>{{harvnb|Belmaker|2006|p=21}}</ref> The ] was Mediterranean, not savanna. The animals were not passing through; there was simply an overlap of normal ranges. Of the Hominans, ''H. erectus'' left several cranial fragments. Teeth of undetermined species may have been ''H. ergaster''.<ref>{{harvnb|Belmaker|2006|p=20}}</ref> The tools are classified as "Lower Acheulean" and "Developed Oldowan". The latter is a disputed classification created by ] to describe an Acheulean-like tradition in Bed II at ]. It is dated 1.53–1.27 mya. The date of the tools therefore probably does not exceed 1.5 mya; 1.4 is often given as a date. This chronology, which is definitely later than in Kenya, supports the "out of Africa" hypothesis for Acheulean, if not for the Hominans. | |||

| ] at ] foothill, ], National Museum of Iran]] | |||

| From Southwest Asia, as the Levant is now called, the Acheulean extended itself more slowly eastward, arriving at ], India, about 1.2 mya. It does not appear in China and Korea until after 1mya and not at all in Indonesia. There is a discernible boundary marking the furthest extent of the Acheulean eastward before 1 mya, called the ], after its proposer, ]. On the east side of the line the small flake tradition continues, but the tools are additionally worked Mode 1, with flaking down the sides. In Athirampakkam at ] in ] the Acheulean age started at 1.51 mya and it is also prior than North India and Europe.<ref>{{cite web|title=Acheulian stone tools discovered near Chennai|url=http://www.hindu.com/2011/03/25/stories/2011032564021300.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110823111619/http://www.hindu.com/2011/03/25/stories/2011032564021300.htm|url-status=dead|work=]|date=2011-03-25|archive-date=2011-08-23}}</ref> | |||

| The cause of the Movius Line remains speculative, whether it represents a real change in technology or a limitation of archeology, but after 1 mya evidence not available to Movius indicates the prevalence of Acheulean. For example, the Acheulean site at Bose, China, is dated 0.803±3K mya.<ref>{{cite web | title=Bose, China | work=What Does It Mean to be Human? | publisher=Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History | url=http://humanorigins.si.edu/research/asian-research/bose-china| date=28 January 2010 }}</ref> The authors of this chronologically later East Asian Acheulean remain unknown, as does whether it evolved in the region or was brought in. | |||

| There is no named boundary line between Mode 1 and Mode 2 on the west; nevertheless, Mode 2 is equally late in Europe as it is in the Far East. The earliest comes from a rock shelter at Estrecho de Quípar in Spain, dated to greater than 0.9 mya. Teeth from an undetermined Hominan were found there also.<ref>{{cite journal | first=Rex | last=Dalton | title=Europe's oldest axes discovered | journal=Nature News | date=2 September 2009 | url=http://www.nature.com/news/2009/090902/full/news.2009.878.html | doi=10.1038/news.2009.878}}</ref> The last Mode 2 in Southern Europe is from a deposit at Fontana Ranuccio near ] in Italy dated to 0.45 mya, which is generally linked to '']'', a "late variant of ''H. erectus''", a fragment of whose skull was found at Ceprano nearby, dated 0.46 mya.<ref>{{cite journal | journal=Earth and Planetary Science Letters | volume=286 | issue=1–2 | year=2009 | pages=255–268 | doi=10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.032 |author=Giovanni Muttoni | title=Pleistocene magnetochronology of early hominid sites at Ceprano and Fontana Ranuccio, Italy | url=http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~dvk/dvk_REPRINTS/Muttoni+2009b.pdf|display-authors=etal | bibcode=2009E&PSL.286..255M}}</ref> | |||

| ====Middle Paleolithic==== | |||

| {{main|Middle Paleolithic}} | |||

| This period is best known as the era during which the ]s lived in Europe and the Near East (c. 300,000–28,000 years ago). Their technology is mainly the ], but Neanderthal physical characteristics have been found also in ambiguous association with the more recent ] archeological culture in Western Europe and several local industries like the ] in Eastern Europe/Eurasia. There is no evidence for Neanderthals in Africa, Australia or the Americas. | |||

| Neanderthals nursed their elderly and practised ] burial indicating an organised society. The earliest evidence (]) of settlement in Australia dates to around ] when modern humans likely crossed from Asia by island-hopping. Evidence for symbolic behavior such as body ornamentation and burial is ambiguous for the Middle Paleolithic and still subject to debate. The ] exhibit the earliest traces of human life in India, some of which are approximately 30,000 years old. | |||

| ====Upper Paleolithic==== | |||

| {{main|Upper Paleolithic}} | |||

| ] found in the north-west ]]] | |||

| From 50,000 to 10,000 years ago in Europe, the Upper Paleolithic ends with the end of the Pleistocene and onset of the Holocene era (the end of the ]). Modern humans spread out further across the Earth during the period known as the Upper Paleolithic. | |||

| The Upper Paleolithic is marked by a relatively rapid succession of often complex stone artifact technologies and a large increase in the creation of art and personal ornaments. During period between 35 and 10 kya evolved: from 38 to 30 kya ], 40–28 ], 28–22 ], 22–17 ], and 18–10 ]. All of these industries except the Châtelperronian are associated with anatomically modern humans. Authorship of the Châtelperronian is still the subject of much debate. | |||

| Most scholars date the arrival of ] at 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, with a possible range of up to 125,000 years ago. The earliest ] remains found in Australia (and outside of Africa) are those of ]; they have been dated at 42,000 years old.<ref name = "pmid1259451">{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1038/nature01383| pmid = 12594511| title = New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia| journal = Nature| volume = 421| issue = 6925| pages = 837–840| year = 2003| last1 = Bowler | first1 = J.M. | last2 = Johnston | first2 = H. | last3 = Olley | first3 = J. M. | last4 = Prescott | first4 = J. R. | last5 = Roberts | first5 = R. G. | last6 = Shawcross | first6 = W. | last7 = Spooner | first7 = N. A. | bibcode = 2003Natur.421..837B| s2cid = 4365526}}</ref><ref name = "doisj.quascirev.2005.07.022">{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.07.022| title = Single-grain optical dating of grave-infill associated with human burials at Lake Mungo, Australia| journal = Quaternary Science Reviews| volume = 25| issue = 19–20| pages = 2469–2474| year = 2006| last1 = Olley | first1 = J. M. | last2 = Roberts | first2 = R. G. | last3 = Yoshida | first3 = H. | last4 = Bowler | first4 = J. M. | bibcode = 2006QSRv...25.2469O}}</ref> | |||

| The Americas were colonised via the ] which was exposed during this period by lower sea levels. These people are called the ], and the earliest accepted dates are those of the ] sites, some 13,500 years ago. Globally, societies were ]s but evidence of regional identities begins to appear in the wide variety of stone tool types being developed to suit very different environments. | |||

| ====Epipaleolithic/Mesolithic==== | |||

| {{main|Epipaleolithic|Mesolithic}} | |||

| The period starting from the end of the last ], 10,000 years ago, to around 6,000 years ago was characterized by ] and a need to adapt to a changing environment and find new food sources. The development of Mode 5 (]) tools began in response to these changes. They were derived from the previous Paleolithic tools, hence the term Epipaleolithic, or were intermediate between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic, hence the term ] (Middle Stone Age), used for parts of Eurasia, but not outside it. The choice of a word depends on exact circumstances and the inclination of the archaeologists excavating the site. Microliths were used in the manufacture of more efficient composite tools, resulting in an intensification of hunting and fishing and with increasing social activity the development of more complex settlements, such as ]. Domestication of the dog as a hunting companion probably dates to this period. | |||

| The earliest known battle occurred during the Mesolithic period at a site in Egypt known as ]. | |||

| ====Neolithic==== | |||

| {{Main|Neolithic}} | |||

| ], Scotland: Europe's most complete ] village]] | |||

| ], 3300 to 2400 BC, ], France]] | |||

| The ], or New Stone Age, was approximately characterized by the adoption of agriculture. The shift from food gathering to food producing, in itself one of the most revolutionary changes in human history, was accompanied by the so-called ]: the development of ], polished stone tools, and construction of more complex, larger settlements such as ] and ]. Some of these features began in certain localities even earlier, in the transitional Mesolithic. The first Neolithic cultures started around 7000 BC in the ] and spread concentrically to other areas of the world; however, the Near East was probably not the only nucleus of agriculture, the cultivation of maize in Meso-America and of ] in the Far East being others. | |||

| Due to the increased need to harvest and process plants, ground stone and polished stone artifacts became much more widespread, including tools for grinding, cutting, and chopping. ], located in ], ], is one of Europe's best examples of a Neolithic village. The community contains stone beds, shelves and even an indoor toilet linked to a stream. The first large-scale constructions were built, including settlement towers and walls, e.g., Jericho (]) and ceremonial sites, e.g. ]. The ] temples of Gozo in the Maltese archipelago are the oldest surviving free standing structures in the world, erected {{Circa|3600}}–2500 BC. The earliest evidence for established trade exists in the ] with newly settled people importing exotic goods over distances of many hundreds of miles. | |||

| These facts show that there were sufficient resources and co-operation to enable large groups to work on these projects. To what extent this was a basis for the development of elites and social hierarchies is a matter of ongoing debate.<ref>{{Cite book | first=Ian | last=Kuijt | editor-first=Ian |editor-last=Kuijt | year=2000 | title=Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and differentiation | contribution=Chapter 13: Near Eastern Neolithic Research: Directions and Trends | series=Fundamental Issues in Archaeology | page=317 | location=New York | publisher=Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers }}</ref> Although some late Neolithic societies formed complex stratified chiefdoms similar to Polynesian societies such as the ]ans, based on the societies of modern tribesmen at an equivalent technological level, most Neolithic societies were relatively simple and ].<ref>{{Cite book |title=Evolutionary Origins of Morality: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives | editor-first=Leonard D. | editor-last=Katz |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=inmTyPPdR5oC&q=Neolithic+egalitarianism&pg=RA1-PA158 | year=2000 | first=Christopher | last=Boehm | contribution=The Origin of Morality as Social Control | location=Thorverton | page=158 | publisher=Imprint Academic | series=Journal of Consciousness Studies |volume=7 | isbn=978-0-7190-5612-3 }}</ref> A comparison of art in the two ages leads some theorists to conclude that Neolithic cultures were noticeably more hierarchical than the ] cultures that preceded them.<ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3u6JNwMyMCEC&q=paleolithic+history+violence&pg=PA422 | title=The Nature of Paleolithic Art | first=Russell Dale | last=Guthrie | pages=419–420 | location=Chicago | publisher=University of Chicago Press | year=2005 | isbn=978-0-226-31126-5}}</ref> | |||

| ===African chronology=== | |||

| {{main|African archaeology}} | |||

| ====Early Stone Age (ESA)==== | |||

| {{main|Paleolithic|Lower Paleolithic}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] is not to be identified with "Old Stone Age", a translation of Paleolithic, or with Paleolithic, or with the "Earlier Stone Age" that originally meant what became the Paleolithic and Mesolithic. In the initial decades of its definition by the Pan-African Congress of Prehistory, it was parallel in Africa to the ] and ]. However, since then ] has shown that the Middle Stone Age is in fact contemporaneous with the ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | first=J. Desmond | last=Clark | author-link=J. Desmond Clark | title=The Culture of the Middle Paleolithic/Middle Stone Age | editor-first=J. Desmond | series=Volume | editor-last=Clark | encyclopedia=The Cambridge History of Africa | volume=I: From the Earliest Times to C. 500 BC | page=248 | location=Cambridge | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1982 }}</ref> The Early Stone Age therefore is contemporaneous with the ] and happens to include the same main technologies, ] and ], which produced Mode 1 and Mode 2 ]s respectively. A distinct regional term is warranted, however, by the location and chronology of the sites and the exact typology. | |||

| ====Middle Stone Age (MSA)==== | |||

| {{main|Middle Stone Age}} | |||

| The Middle Stone Age was a period of African prehistory between Early Stone Age and Late Stone Age. It began around 300,000 years ago and ended around 50,000 years ago.<ref>McBrearty and Brooks 2000</ref> It is considered as an equivalent of European ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.accessexcellence.org/BF/bf02/klein/bf02e3.html|title=Biological origins of modern humans}}</ref> It is associated with anatomically modern or almost modern '']''. Early physical evidence comes from Omo<ref>McDougall et al. 2005</ref> and Herto,<ref>White et al. 2003</ref> both in Ethiopia and dated respectively at c. 195 ka and at c. 160 ka. | |||

| ====Later Stone Age (LSA)==== | |||

| {{main|Later Stone Age}} | |||

| The Later Stone Age (LSA, sometimes also called the '''Late Stone Age''') refers to a period in African prehistory. Its beginnings are roughly contemporaneous with the European Upper Paleolithic. It lasts until historical times and this includes cultures corresponding to Mesolithic and Neolithic in other regions. | |||

| ==Material culture== | |||

| ===Tools=== | |||

| ]s were made from a variety of stones. For example, ] and ] were shaped (or '']'') for use as cutting tools and ]s, while ] and ] were used for ] tools, such as ]s. Wood, bone, ], ] (deer) and other materials were widely used, as well. During the most recent part of the period, ]s (such as ]) were used to make ]. Agriculture was developed and certain animals were ] as well. | |||

| Some species of non-]s are able to use stone tools, such as the ], which breaks ] shells with them. ]s can both use and manufacture stone tools. This combination of abilities is more marked in ]s and humans, but only humans, or more generally ]s, depend on tool use for survival.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=74}}</ref> The key anatomical and behavioral features required for tool manufacture, which are possessed only by hominins, are the larger thumb and the ability to hold by means of an assortment of grips.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=108}}</ref> | |||

| ===Food and drink=== | |||

| {{main|Paleolithic diet|Paleolithic#Diet and nutrition|l2=Paleolithic diet and nutrition}} | |||

| Food sources of the Palaeolithic ]s were wild plants and animals harvested from the ]. They liked animal ] meats, including the ]s, ]s and ]s. Large seeded ]s were part of the human diet long before the ], as is evident from archaeobotanical finds from the ] layers of ], in Israel.<ref name="doi10.1016/j.jas.2004.11.006">{{cite journal |first1=Efraim |last1=Lev | first2=Mordechai E. |last2=Kislev|first3= Ofer |last3=Bar-Yosef |title=Mousterian vegetal food in Kebara Cave, Mt. Carmel |journal=Journal of Archaeological Science |volume=32 |issue=3 |pages=475–484 |date=March 2005 |doi=10.1016/j.jas.2004.11.006 | bibcode=2005JArSc..32..475L}}</ref> Moreover, recent evidence indicates that humans processed and consumed wild cereal grains as far back as 23,000 years ago in the ].<ref name="pmid15295598">{{cite journal|first1=Dolores R. |last1=Piperno |first2=Ehud |last2=Weiss |first3=Irene |last3=Holst |first4=Dani |last4=Nadel |title=Processing of wild cereal grains in the Upper Palaeolithic revealed by starch grain analysis |journal=Nature |volume=430 |issue=7000 |pages=670–673 |date=5 August 2004 |pmid=15295598 |doi=10.1038/nature02734 |url=http://anthropology.si.edu/archaeobio/Ohalo%20II%20Nature.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110504082225/http://anthropology.si.edu/archaeobio/Ohalo%20II%20Nature.pdf |archive-date=4 May 2011 |bibcode=2004Natur.430..670P |s2cid=4431395 }}</ref> | |||

| Near the end of the ], 15,000 to 9,000 years ago, mass extinction of ] such as the ] occurred in Asia, Europe, North America and Australia. This was the first ]. It possibly forced modification in the dietary habits of the humans of that age and with the emergence of ], plant-based foods also became a regular part of the diet. A number of factors have been suggested for the extinction: certainly over-hunting, but also deforestation and climate change.<ref>{{Cite book | editor-first=Samuel T. | editor-last=Turvey | first=Samuel T. |last=Turvey | title=Holocene Extinctions | contribution=Chapter 2: In the shadow of the megafauna: prehistoric mammal and bird extinctions across the Holocene | series=Oxford Biology | location=Oxford | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=2009 | pages=16–17 }}</ref> The net effect was to fragment the vast ranges required by the large animals and extinguish them piecemeal in each fragment. | |||

| ===Shelter and habitat=== | |||

| Around 2 million years ago, '']'' is believed to have constructed the first man-made structure in East Africa, consisting of simple arrangements of stones to hold branches of trees in position. A similar stone circular arrangement believed to be around 380,000 years old was discovered at ], near ], France. (Concerns about the dating have been raised: see ].) Several human habitats dating back to the Stone Age have been discovered around the globe, including: | |||

| * A tent-like structure inside a cave near the ], Nice, France. | |||

| * A ] with a roof supported with timber, discovered in ], the ], dates to around 23,000 BC. The walls were made of packed clay blocks and stones. | |||

| * Many huts made of ] bones have been found in East-Central Europe and ]. The people who made these huts were expert mammoth hunters. Examples have been found along the ] river valley of ], including near ], in ], Czech Republic and in southern Poland. | |||

| * An animal hide tent dated to around 15000 to ], in the ], was discovered at Plateau Parain, France. | |||

| ===Art=== | ===Art=== | ||

| ] |

] is visible in the artifacts. ] is inferred from found instruments, while ] can be found on rocks of any kind. The latter are petroglyphs and rock paintings. The art may or may not have had a religious function.<ref name="Ranger1976">{{cite book|last1=Ranger|first1=Terence O.|last2=Kimambo|first2=Isaria N.|title=The Historical Study of African Religion|date=1976|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-03179-1|page=30|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KPcGrcVAlowC&pg=PA30|access-date=25 September 2017|language=en}}</ref> | ||

| ====Petroglyphs==== | ====Petroglyphs==== | ||

| {{main|Petroglyph}} | {{main|Petroglyph}} | ||

| ], Australia]] | |||

| ]s appeared in the New Stone Age, commonly known as Neolithic period. A Petroglyph is an abstract or symbolic image recorded on stone, usually by prehistoric peoples, by means of ''carving'', pecking or otherwise incised on natural rock surfaces. They were a dominant form or pre-writing symbols used in communication. Petroglyphs have been discovered in different parts of the world, including ] (]), ] (]), ] (], ]), and Europe (]). | |||

| ]s appeared in the ]. A Petroglyph is an ] abstract or symbolic image engraved on natural stone by various methods, usually by prehistoric peoples. They were a dominant form of pre-writing symbols. Petroglyphs have been discovered in different parts of the world, including Australia (]), Asia (]), North America (]), South America (], Peru), and Europe (]). | |||

| ====Rock paintings==== | ====Rock paintings==== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| {{main|Cave painting}} | {{main|Cave painting}} | ||