| Revision as of 20:38, 23 October 2008 editJonH (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,464 edits →Shaded relief: more about top-left lighting← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:34, 5 January 2025 edit undoSalmoonlight (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users21,681 editsmNo edit summary | ||

| (150 intermediate revisions by 74 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Representation of surface shape on maps}} | |||

| ] topographic map of ] with contour lines at 20-foot intervals]] | |||

| {{broader|Cartographic design}} | |||

| ] topographic map of ] with contour lines at 20-foot intervals]] | |||

| ] or relief is an essential aspect of ], and as such its portrayal presents a central problem in ], and more recently ] and |

'''Terrain cartography''' or '''relief mapping''' is the depiction of the shape of the surface of the Earth on a map, using one or more of several techniques that have been developed. ] or relief is an essential aspect of ], and as such its portrayal presents a central problem in ], and more recently ]s and ]. | ||

| The most obvious way to depict relief is to imitate it at scale, as in molded or sculpted solid ]s and molded-plastic ]s. Because of the disparity between the horizontal and vertical scales of maps, raised relief is typically exaggerated. | |||

| On flat paper maps, terrain can be depicted in a variety of ways, outlined below: | |||

| ==Hill profiles== | ==Hill profiles== | ||

| ] by |

] by ], showing use of hill profiles]] | ||

| The most ancient form of relief depiction in cartography, '''hill profiles''' are simply illustrations of mountains and hills in profile, placed as appropriate on generally small-scale (broad area of coverage) maps. They are seldom used today except as part of an "antique" styling. | The most ancient form of relief depiction in cartography, '''hill profiles''' are simply illustrations of mountains and hills in profile, placed as appropriate on generally small-scale (broad area of coverage) maps. They are seldom used today except as part of an "antique" styling. | ||

| ===Physiographic illustration=== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1921, A.K. Lobeck published ''A Physiographic Diagram of the United States'', using an advanced version of the hill profile technique to illustrate the distribution of landforms on a small-scale map.<ref name="lobeck">Lobeck, A.K. (1921) , A.J. Nystrom & Co., digital scan at David Rumsey Map Collection, List No.7129.000</ref> ] further developed, standardized, and taught this technique, which uses generalized texture to imitate ] shapes over a large area.<ref name="raisz1948">{{cite book |last1=Raisz |first1=Erwin |title=General Cartography |date=1948 |publisher=McGraw-Hill |pages=103–123 |edition=2nd}}</ref> A combination of hill profile and shaded relief, this style of terrain representation is simultaneously idiosyncratic to its creator—often hand-painted—and found insightful in illustrating ] patterns. | |||

| ===Plan oblique relief=== | |||

| ] in the full-size version.]] | |||

| More recently, ] developed a computer-generated technique for mapping terrain inspired by Raisz's work, called ''plan oblique relief''.<ref name="jennypatterson">{{cite journal |last1=Jenny |first1=Bernhard |last2=Patterson |first2=Tom |title=Introducing Plan Oblique Relief |journal=Cartographic Perspectives |date=2007 |issue=57 |pages=21–40 |doi=10.14714/CP57.279 |url=http://www.shadedrelief.com/plan_oblique/plan_oblique.pdf}}</ref> This tool starts with a shaded relief image, then shifts pixels northward proportional to their elevation. The effect is to make mountains "stand up" and "lay over" features to the north, in the same fashion as hill profiles. Some viewers are able to see the effect more easily than others. | |||

| ==Hachures== | ==Hachures== | ||

| ] |

] (1907); this is a shaded hachure map.]] | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Hachure map}} | ||

| '''Hachures''' |

'''Hachures''', first standardized by the Austrian topographer Johann Georg Lehmann in 1799, are a form of shading using lines. They show the orientation of slope, and by their thickness and overall density they provide a general sense of steepness. Being non-numeric, they are less useful to a scientific survey than contours, but can successfully communicate quite specific shapes of terrain.<ref name="raisz1948" /> They are especially effective at showing relatively low relief, such as rolling hills. It was a standard on topographic maps of Germany well into the 20th Century. | ||

| There have been multiple attempts to recreate this technique using digital GIS data, with mixed results. | |||

| Hachure representation of relief was standardized by the Austrian topographer Johann Georg Lehmann in 1799. | |||

| ==Contour lines== |

==Contour lines== | ||

| {{Main|Contour line}} | |||

| ] with blue contours for ]s, and black contours and hachures for rock]] | |||

| First developed in France in the 18th Century, '''contour lines''' (or isohypses) are isolines of equal elevation. This is the most common way of visualizing elevation quantitatively, and is familiar from ]s. | |||

| {{main|Contour line}} | |||

| '''Contour lines''' (or isohypses) are isolines showing equal elevation. This is the most common way of numerically showing elevation, and is familiar from ]s. | |||

| Most 18th and early 19th |

Most 18th- and early 19th-century national ] did not record relief across the entire area of coverage, calculating only spot elevations at survey points. The ] (USGS) topographical survey maps included contour representation of relief, and so maps that show relief, especially with exact representation of elevation, came to be called topographic maps (or "topo" maps) in the ], and the usage has spread internationally. | ||

| ] (1877) with black, blue and brown contour lines at 30-meter intervals]] | |||

| On maps produced by ], the color of the contour lines is used to indicate the type of ground: black for bare rock and ], blue for ice and underwater contours, brown for earth-covered ground.<ref>Swisstopo, .</ref> | |||

| On maps produced by ], the color of the contour lines is used to indicate the type of ground: black for bare rock and ], blue for ice and underwater contours, and brown for earth-covered ground.<ref> | |||

| Swisstopo, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080528053109/http://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/internet/swisstopo/en/home/products/maps/leisure/hiking.parsysrelated1.96279.downloadList.81398.DownloadFile.tmp/symbolsen.pdf |date=2008-05-28 }}. | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ===Tanaka (relief) contours=== | |||

| There are several rules to note when viewing topographic maps: | |||

| The '''Tanaka (relief) contours''' technique is a method used to illuminate contour lines in order to help visualize terrain. Lines are highlighted or shaded depending on their relationship to a light source in the Northwest. If the object being illustrated would shadow a section of contour line, that contour would be represented with a black band. Otherwise, slopes facing the light source would be represented by white bands. | |||

| *'''The rule of V's''': sharp-pointed vees usually are in stream valleys, with the drainage channel passing through the point of the vee, with the vee pointing upstream. This is a consequence of ]. | |||

| *'''The rule of O's''': closed loops are normally uphill on the inside and downhill on the outside, and the innermost loop is the highest area. If a loop instead represents a depression, some maps note this by short lines radiating from the inside of the loop, called "hachures". | |||

| *'''Spacing of contours''': close contours indicate a steep slope; distant contours a shallow slope. Two or more contour lines merging indicates a cliff. | |||

| This method was developed by Professor Tanaka Kitiro in 1950, but had been experimented with as early as 1870, with little success due to technological limitations in printing. The resulting terrain at this point was a grayscale image.<ref>Fundamentals of Cartography. Misra R. P. and A. Ramesh. Concept Publishing Company. 1989. pp. 389-390</ref> Cartographer ] later created software to digitally produce Tanaka Contours, and Patrick Kennelly, another cartographer, later found a way to add color to these maps, making them more realistic.<ref>Patrick Kennelly & A. Jon Kimerling (2001) Modifications of Tanaka's Illuminated Contour Method, Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 28:2, 111-123.</ref> | |||

| Of course, to determine differences in elevation between two points, the contour interval, or distance in altitude between two adjacent contour lines, must be known, and this is given at the bottom of the map. Usually contour intervals are consistent throughout a map, but there are exceptions. Sometimes intermediate contours are present in flatter areas; these can be dashed or dotted lines at half the noted contour interval. When contours are used with hypsometric tints on a small-scale map that includes mountains and flatter low-lying areas, it is common to have smaller intervals at lower elevations so that detail is shown in all areas. Conversely, for an island which consists of a plateau surrounded by steep cliffs, it is possible to use smaller intervals as the height increases.<ref>''] (Sercq)'', D Survey, Ministry of Defence, Series M 824, Sheet Sark, Edition 4 GSGS, 1965, ] . Scale 1:10,560. Contour intervals: 50 feet up to 200, 20 feet from 200 to 300, and 10 feet above 300.</ref> | |||

| There are a number of issues with this method. Historically, printing technology did not reproduce Tanaka contours well, especially the white lines on a gray background. This method is also very time-consuming. In addition, the terraced appearance does not look appealing or accurate in some kinds of terrain.<ref>"RELIEF (TERRAIN) DEPICTION." UNBC GIS LAB: GIS & Remote Sensing. University of Northern British Columbia, n.d. Web. 28 Sept. 2013.</ref> | |||

| ==Hypsometric tints== | ==Hypsometric tints== | ||

| {{main|Hypsometric tints}} | |||

| ]. The color scale represents elevation and is broken into two sections relative to sea level.]] | |||

| {{:Hypsometric tints}} | |||

| <!-- ] - The color of the map represents the elevation. The highest points are represented in red. The lowest points are represented in purple. In decending order the colors are red, orange, yellow, green, cyan, blue and purple.]] --> | |||

| '''Hypsometric tints''' are a variant on contour lines. They depict ranges of elevation as bands of color, usually in a graduated scheme. | |||

| ==Shaded relief== | |||

| The ] map firm ] is credited with popularizing the technique, and its color scheme has become conventional: dark greens at low elevations, progressing through yellows and ochers, to browns and then grays and white at the highest elevations. | |||

| {{Seealso|Geomorphometry#Illumination/Shaded Relief/Analytical Hillshading{{!}}Terrain analysis}} | |||

| ] area.<br />Bottom: the same map with sun shading.]] | |||

| Hypsometric tinting in maps is often accompanied by ] tinting in ]s, which indicates depths using a similar method | |||

| '''Shaded relief''', or hill-shading, shows the shape of the terrain in a realistic fashion by showing how the three-dimensional surface would be illuminated from a point light source. The ]s normally follow the convention of ] in which the light source is placed near the upper-left corner of the map. If the map is ] with north at the top, the result is that the light appears to come from the north-west. Although this is unrealistic lighting in the northern hemisphere, using a southern light source can cause ] illusions, in which the topography appears inverted.<ref>{{cite book| author = Eduard Imhof| title = Cartographic relief presentation| date = 2007-06-01| publisher = Esri Pr| isbn = 978-1-58948-026-1| url-access = registration| url = https://archive.org/details/cartographicreli0000imho}}</ref> | |||

| ==Shaded relief== | |||

| ] area<br />Bottom: the same map with sun shading]] | |||

| Shaded relief was traditionally drawn with ], ] and other artist's media. The Swiss cartographer ] is widely regarded as a master of manual hill-shading technique and theory. Shaded relief is today almost exclusively computer-generated from ]s (DEM). The mathematical basis of ''analytical hillshading'' is to calculate the ] at each location, then calculate the angle between that vector and the vector pointing to the illumination using the ]; the smaller that angle, the more illumination that location is receiving. However, most software implementations use algorithms that shorten those calculations. This tool is available in a variety of GIS and graphics software, including ], ], ] or ]'s Spatial Analyst extension. | |||

| '''Shaded relief''', or hill-shading, simulates the cast ] thrown upon a raised relief map, or more abstractly upon the planetary surface represented. The shadows normally follow the convention of ] in which the light source is placed near the upper-left corner of the map. If the map is ] with north at the top, the result is that the light appears to come from the north-west. Many people have pointed out that this is unrealistic for maps of the northern hemishere, because the sun does not shine from that direction, and they have proposed using southern lighting. However, the normal convention is followed to avoid ] illusions (i.e. crater/hill confusion).<ref>E. Imhof, ''Cartographic Relief Presentation'', Walter de Gruyter, 1982, reissued by ESRI Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1-58948-026-1, pp. 178-185.</ref> | |||

| While these relatively simple tools have made shaded relief almost ubiquitous in maps, many cartographers{{weasel word|date=June 2023}} have been unhappy with the product,{{which|date=June 2023}} and have developed techniques to improve its appearance, including the following: | |||

| Traditionally drawn with ], ] and other artist's media, shaded relief is today almost exclusively computer-generated using ]s, with a resulting different look and feel. Much work has been done in digitally recreating the work of Swiss master ], widely regarded as the master of manual hill-shading technique and theory. Imhof's contributions included a multi-color approach to shading, with purples in valleys and yellows on peaks. | |||

| ===Illuminated shading=== | |||

| The use of illumination and shadow to produce an appearance of ] on a flat-surfaced ] closely parallels the painting technique known as ]. | |||

| Imhof's contributions included a multi-color approach to shading, with purples in valleys and yellows on peaks, which is known as “illuminated shading.” Illuminating the sides of the terrain facing the light source with yellow colors provides greater realism (since direct sunlight is more yellow, and ambient light is more blue), enhances the sense of the three-dimensional nature of the terrain, and make the map more aesthetically pleasing and artistic-looking.<ref>{{cite journal |first1=Bernhard |last1=Jenny |first2=Lorenz |last2=Hurni |title=Swiss-Style Colour Relief Shading Modulated by Elevation and by Exposure to Illumination |journal=The Cartographic Journal |volume=43 |number=3 |year=2006 |pages=198–207 |doi=10.1179/000870406X158164|bibcode=2006CartJ..43..198J }}</ref> Much work has been done in digitally recreating the work of ], which has been fairly successful in some cases.<ref>Tom Patterson, "See the light: How to make illuminated shaded relief in Photoshop 6.0," http://www.shadedrelief.com/illumination/ (accessed 30 October 2017).</ref> | |||

| ===Multi-directional shading=== | |||

| ==Physiographic illustration== | |||

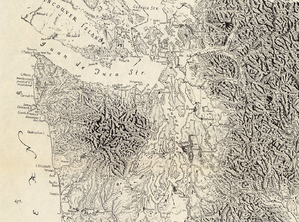

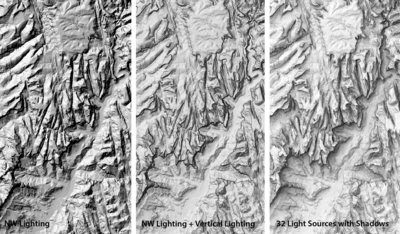

| ], ], showing the effect of multi-directional hillshading. Left: one light source, standard northwest azimuth; Middle: average of two light sources, northwest + vertical; Right: average of 32 light sources from all directions but concentrated in the northwest, each with shadows added. Note the decreasing starkness, increasing realism, and increasing clarity of cliffs, canyons, and mountains in this area of over 1,000 m of local relief.]] | |||

| Pioneered by Hungarian-American cartographer ], this technique uses generalized texture to imitate landform shapes over a large area. A combination of hill profile and shaded relief, this style of relief representation is simultaneously idiosyncratic to its creator and very useful in illustrating geomorphological patterns. | |||

| A common criticism of computer-generated analytical hillshading is its stark, artificial look, in which slopes facing the light are solid white, and slopes facing away are solid black. Raisz called it "plastic shading," and others have said it looks like a moonscape.<ref name="raisz1948" /> One solution is to incorporate multiple lighting directions to imitate the effect of ambient lighting, creating a much more realistic looking product. Multiple techniques have been proposed for doing this, including using ] software for generating multiple shaded relief images and averaging them together, using 3-d modeling software to ],<ref>Huffman, Daniel P. (2014) , 9th ICA Mountain Cartography Workshop</ref> and custom software tools to imitate natural lighting using up to hundreds of individual sources.<ref>Kennelly, J., & Stewart, J. (2006). A Uniform Sky Illumination Model to Enhance Shading of Terrain and Urban Areas. Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 33(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1559/152304006777323118.</ref> This technique has been found to be most effective for very rugged terrain at medium scales of 1:30,000 to 1:1,000,000. | |||

| ===Texture/bump mapping=== | |||

| More recently, ] created a of the United States using Erwin Raisz's work as a starting point. | |||

| ], ], using texture mapping to subtly indicate vegetation cover]] | |||

| {{main | Bump mapping }} | |||

| It is possible to make the terrain look more realistic by imitating the three-dimensional look of not only the bare land surface, but also the features covering that land surface, such as buildings and plants. Texture mapping or bump mapping is a technique adapted from ] that adds a layer of shaded texture to the shaded surface relief that imitates the look of the local land cover.<ref name="Blinn">Blinn, James F. , Computer Graphics, Vol. 12 (3), pp. 286-292 ]-ACM (August 1978)</ref> This texture can be generated in several ways: | |||

| * '''Texture substitution''': Copying, abstracting, and merging ] imagery of land cover.<ref name="patterson2002">{{cite journal |last1=Patterson |first1=Tom |title=Getting Real: Reflecting on the New Look of National Park Service Maps |journal=Cartographic Perspectives |date=2002 |issue=43 |pages=43–56 |doi=10.14714/CP43.536|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| * '''Texture generation''': Creating a simulated land cover elevation layer in GIS, such as a random scattering of "trees," then generating a shaded relief of this.<ref name="nighbert">{{cite journal |last1=Nighbert |first1=Jeffrey |title=Using Remote Sensing Imagery to Texturize Layer Tinted Relief |journal=Cartographic Perspectives |date=2000 |issue=36 |pages=93 |doi=10.14714/CP36.827 |url=https://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/view/cp36-nighbert/pdf}}</ref> | |||

| * '''Elevation measurement''': Using fine resolution remote sensing techniques, especially ] and ], to directly or indirectly (through ]) measure the height and or shape of land cover features, and shade that elevation surface. | |||

| This technique is most useful at producing realistic maps at relatively large scales, 1:5,000 to 1:50,000. | |||

| ===Resolution mixing or bumping=== | |||

| ] and ], ]/]. Left: 200 m resolution shaded relief, middle: shaded relief after 7000 m smoothing filter, right: 65%/35% mix. The original image looks uniformly rugged, while the one on the right emphasizes the larger mountains and canyons.]] | |||

| One challenge with shaded relief, especially at small scales (1:500,000 or less), is that the technique is very good at visualizing local (high-frequency) relief, but may not effectively show larger features. For example, a rugged area of hills and valleys will show as much or more variation than a large, smooth mountain. Resolution bumping is a hybrid technique developed by ] cartographer Tom Patterson to mitigate this problem.<ref>Patterson, Tom., "Resolution bumping GTOPO30 in Photoshop: How to Make High-Mountains More Legible," http://www.shadedrelief.com/bumping/bumping.html (accessed 24 September 2012)</ref> A fine-resolution DEM is averaged with a heavily smoothed version (i.e., significantly coarser resolution). When the hillshading algorithm is applied to this, it has the effect of blending the fine details of the original terrain model with the broader features brought out by the smoothed model. This technique works best at small scales and in regions that are consistently rugged. | |||

| ==Oblique view== | |||

| ] by ]. ]] | |||

| {{main | Pictorial map}} | |||

| A three-dimensional view (projected onto a two-dimensional medium) of the surface of the Earth, along with the geographic features resting on it. Imagined aerial views of cities were first produced during the late ], but these "bird's eye views" became very popular in the ] during the 1800s. The advent of ] (especially recent advances in 3-D and global visualization) and ] has made the production of realistic aerial views relatively easy, although the execution of quality ] on these models remains a challenge.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Patterson |first1=Tom |title=Looking Closer: A Guide to Making Bird's-eye Views of National Park Service Cultural and Historical Sites |journal=Cartographic Perspectives |date=2005 |issue=52 |pages=59–75 |doi=10.14714/CP52.379 |url=https://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/view/cp52-patterson/pdf|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Raised-relief map== | |||

| ] in scale 1: 50 000]] | |||

| {{main | Raised-relief map}} | |||

| This is a map in which relief is shown as a three-dimensional object. The most intuitive way to depict relief is to imitate it at scale. Hand-crafted dioramas may date back to 200BCE in China, but mass production did not become available until ] with the invention of ], and ] to create molds efficiently. Machining is also used to create large custom models from substrates such as high-density foam, and can even color them based on aerial photography by placing an ] printhead on the machining device. The advent of ] has introduced a much more economical means to produce raised-relief maps, although most 3D printers are too small to efficiently produce large dioramas.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Adams |first1=Aaron |title=A Comparative Usability Assessment of Augmented Reality 3-D Printed Terrain Models and 2-D Topographic Maps |date=July 2019 |location=New Mexico State University |url=https://www.proquest.com/openview/2d2ba6f6f378dab8c217440f2d608e96/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y |access-date=17 April 2022|via=ProQuest }}</ref> | |||

| ==Rendering== | |||

| ] of ] terrain based on ] data]] | |||

| '''Terrain rendering''' covers a variety of methods of depicting real-world or ] ]s. Most common ] ] is the depiction of ]'s surface. | |||

| It is used in various applications to give an observer a ]. It is also often used in combination with rendering of non-terrain objects, such as ]s, ]s, ]s, etc. | |||

| There are two major modes of terrain rendering: ] and ] rendering. Top-down terrain rendering has been known for centuries in the way of ] maps. Perspective terrain rendering has also been known for quite some time. However, only with the advent of computers and ] perspective rendering has become mainstream. | |||

| ===Structure=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| A typical terrain rendering application consists of a terrain ], a ] (CPU), a dedicated ] (GPU), and a display. A ] is configured to start at initial location in the ]. The output of the application is screen space representation of the real world on a display. The software application uses the CPU to identify and load terrain data corresponding to initial location from the terrain database, then applies the required ] to build a ] of points that can be rendered by the GPU, which completes geometrical transformations, creating screen space objects (such as ]s) that create a picture closely resembling the location of the real world. | |||

| ===Texture=== | |||

| There are a number of ways to ] the terrain surface. Some applications benefit from using artificial textures, such as elevation coloring, ], or other generic textures. Some applications attempt to recreate the real-world surface to the best possible representation using ] and ]. | |||

| In ], ] is used to texture the terrain surface. | |||

| ===Generation=== | |||

| {{main|Scenery generator}} | |||

| There are a great variety of methods to generate terrain surfaces. The main problem solved by all these methods is managing number of processed and rendered polygons. It is possible to create a very detailed picture of the world using billions of data points. However such applications are limited to static pictures. Most uses of terrain rendering are moving images, which require the software application to make decisions on how to simplify (by discarding or approximating) source terrain data. Virtually all terrain rendering applications use ] to manage number of data points processed by CPU and GPU. There are several modern algorithms for terrain surfaces generating.<ref>Stewart J. (1999), “Fast Horizon Computation at All Points of a Terrain With Visibility and Shading Applications”, IEEE Transactions on visualization and computer graphics 4(1).</ref><ref>Bashkov E., Zori S., Suvorova I. (2000), “Modern Methods of Environment Visual Simulation”, In Simulationstechnik, 14. Symposium in Hamburg SCS, pp. 509-514. Europe BVBA, Ghent, Belgium, | |||

| </ref><ref>Bashkov E.A., Zori S.A. (2001), “Visual Simulation of an Earth Surface by Fast Horizon Computation Algorithm”, In Simulation und Visualisierung, pp. 203-215. Institut fur Simulation und Graphik, Magdeburg, Deutschland</ref><ref>Ruzinoor Che Mat & Norani Nordin, 'Silhouette Rendering Algorithm Using Vectorisation Technique from Kedah Topography Maps', Proceeding 2nd National Conference on Computer Graphics and Multimedia (CoGRAMM’04), Selangor, December 2004. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/30969013/449317633605827_1.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1505553957&Signature=7GA1T7nvGM5BOhLQ0OCELIKVYbY%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3D3D_Silhouette_Rendering_Algorithms_using.pdf{{dead link|date=March 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ===Applications=== | |||

| Terrain rendering is widely used in ]s to represent both Earth's surface and imaginary worlds. Some games also have ] (or deformable terrain). | |||

| One important application of terrain rendering is in ] systems. Pilots flying aircraft benefit greatly from the ability to see terrain surface at all times regardless of conditions outside the aircraft. | |||

| ==Skeletal, structural, or break lines== | |||

| {{expand section|date=June 2014}} | |||

| Emphasizes ] ] and watershed streams. | |||

| ==Forums and associations== | ==Forums and associations== | ||

| Portrayal of relief is especially important in ]ous regions. The of the ] is the best-known forum for discussion of theory and techniques for mapping these regions. | Portrayal of relief is especially important in ]ous regions. The of the ] is the best-known forum for discussion of theory and techniques for mapping these regions. | ||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (Real-time optimally adapting mesh) | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Topographic shading}} | |||

| {{portalpar|Atlas|BlankMap-World.png|65}} | |||

| * | * , a website by Tom Patterson | ||

| * , a website of the Institute of Cartography at ] | |||

| * | |||

| * ], a tutorial on creating shaded relief maps using free and open source software | |||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:34, 5 January 2025

Representation of surface shape on maps For broader coverage of this topic, see Cartographic design.

Terrain cartography or relief mapping is the depiction of the shape of the surface of the Earth on a map, using one or more of several techniques that have been developed. Terrain or relief is an essential aspect of physical geography, and as such its portrayal presents a central problem in cartographic design, and more recently geographic information systems and geovisualization.

Hill profiles

The most ancient form of relief depiction in cartography, hill profiles are simply illustrations of mountains and hills in profile, placed as appropriate on generally small-scale (broad area of coverage) maps. They are seldom used today except as part of an "antique" styling.

Physiographic illustration

In 1921, A.K. Lobeck published A Physiographic Diagram of the United States, using an advanced version of the hill profile technique to illustrate the distribution of landforms on a small-scale map. Erwin Raisz further developed, standardized, and taught this technique, which uses generalized texture to imitate landform shapes over a large area. A combination of hill profile and shaded relief, this style of terrain representation is simultaneously idiosyncratic to its creator—often hand-painted—and found insightful in illustrating geomorphological patterns.

Plan oblique relief

More recently, Tom Patterson developed a computer-generated technique for mapping terrain inspired by Raisz's work, called plan oblique relief. This tool starts with a shaded relief image, then shifts pixels northward proportional to their elevation. The effect is to make mountains "stand up" and "lay over" features to the north, in the same fashion as hill profiles. Some viewers are able to see the effect more easily than others.

Hachures

Hachures, first standardized by the Austrian topographer Johann Georg Lehmann in 1799, are a form of shading using lines. They show the orientation of slope, and by their thickness and overall density they provide a general sense of steepness. Being non-numeric, they are less useful to a scientific survey than contours, but can successfully communicate quite specific shapes of terrain. They are especially effective at showing relatively low relief, such as rolling hills. It was a standard on topographic maps of Germany well into the 20th Century.

There have been multiple attempts to recreate this technique using digital GIS data, with mixed results.

Contour lines

Main article: Contour lineFirst developed in France in the 18th Century, contour lines (or isohypses) are isolines of equal elevation. This is the most common way of visualizing elevation quantitatively, and is familiar from topographic maps.

Most 18th- and early 19th-century national surveys did not record relief across the entire area of coverage, calculating only spot elevations at survey points. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) topographical survey maps included contour representation of relief, and so maps that show relief, especially with exact representation of elevation, came to be called topographic maps (or "topo" maps) in the United States, and the usage has spread internationally.

On maps produced by Swisstopo, the color of the contour lines is used to indicate the type of ground: black for bare rock and scree, blue for ice and underwater contours, and brown for earth-covered ground.

Tanaka (relief) contours

The Tanaka (relief) contours technique is a method used to illuminate contour lines in order to help visualize terrain. Lines are highlighted or shaded depending on their relationship to a light source in the Northwest. If the object being illustrated would shadow a section of contour line, that contour would be represented with a black band. Otherwise, slopes facing the light source would be represented by white bands.

This method was developed by Professor Tanaka Kitiro in 1950, but had been experimented with as early as 1870, with little success due to technological limitations in printing. The resulting terrain at this point was a grayscale image. Cartographer Berthold Horn later created software to digitally produce Tanaka Contours, and Patrick Kennelly, another cartographer, later found a way to add color to these maps, making them more realistic.

There are a number of issues with this method. Historically, printing technology did not reproduce Tanaka contours well, especially the white lines on a gray background. This method is also very time-consuming. In addition, the terraced appearance does not look appealing or accurate in some kinds of terrain.

Hypsometric tints

Main article: Hypsometric tintsHypsometric tints (also called layer tinting, elevation tinting, elevation coloring, or hysometric coloring) are colors placed between contour lines to indicate elevation. These tints are shown as bands of color in a graduated scheme or as a color scheme applied to contour lines themselves; either method is considered a type of Isarithmic map. Hypsometric tinting of maps and globes is often accompanied by a similar method of bathymetric tinting to convey differences in water depth.

Shaded relief

See also: Terrain analysis

Bottom: the same map with sun shading.

Shaded relief, or hill-shading, shows the shape of the terrain in a realistic fashion by showing how the three-dimensional surface would be illuminated from a point light source. The shadows normally follow the convention of top-left lighting in which the light source is placed near the upper-left corner of the map. If the map is oriented with north at the top, the result is that the light appears to come from the north-west. Although this is unrealistic lighting in the northern hemisphere, using a southern light source can cause multistable perception illusions, in which the topography appears inverted.

Shaded relief was traditionally drawn with charcoal, airbrush and other artist's media. The Swiss cartographer Eduard Imhof is widely regarded as a master of manual hill-shading technique and theory. Shaded relief is today almost exclusively computer-generated from digital elevation models (DEM). The mathematical basis of analytical hillshading is to calculate the surface normal at each location, then calculate the angle between that vector and the vector pointing to the illumination using the Dot product; the smaller that angle, the more illumination that location is receiving. However, most software implementations use algorithms that shorten those calculations. This tool is available in a variety of GIS and graphics software, including Photoshop, QGIS, GRASS GIS or ArcMap's Spatial Analyst extension.

While these relatively simple tools have made shaded relief almost ubiquitous in maps, many cartographers have been unhappy with the product, and have developed techniques to improve its appearance, including the following:

Illuminated shading

Imhof's contributions included a multi-color approach to shading, with purples in valleys and yellows on peaks, which is known as “illuminated shading.” Illuminating the sides of the terrain facing the light source with yellow colors provides greater realism (since direct sunlight is more yellow, and ambient light is more blue), enhances the sense of the three-dimensional nature of the terrain, and make the map more aesthetically pleasing and artistic-looking. Much work has been done in digitally recreating the work of Eduard Imhof, which has been fairly successful in some cases.

Multi-directional shading

A common criticism of computer-generated analytical hillshading is its stark, artificial look, in which slopes facing the light are solid white, and slopes facing away are solid black. Raisz called it "plastic shading," and others have said it looks like a moonscape. One solution is to incorporate multiple lighting directions to imitate the effect of ambient lighting, creating a much more realistic looking product. Multiple techniques have been proposed for doing this, including using Geographic information systems software for generating multiple shaded relief images and averaging them together, using 3-d modeling software to render terrain, and custom software tools to imitate natural lighting using up to hundreds of individual sources. This technique has been found to be most effective for very rugged terrain at medium scales of 1:30,000 to 1:1,000,000.

Texture/bump mapping

It is possible to make the terrain look more realistic by imitating the three-dimensional look of not only the bare land surface, but also the features covering that land surface, such as buildings and plants. Texture mapping or bump mapping is a technique adapted from Computer graphics that adds a layer of shaded texture to the shaded surface relief that imitates the look of the local land cover. This texture can be generated in several ways:

- Texture substitution: Copying, abstracting, and merging remote sensing imagery of land cover.

- Texture generation: Creating a simulated land cover elevation layer in GIS, such as a random scattering of "trees," then generating a shaded relief of this.

- Elevation measurement: Using fine resolution remote sensing techniques, especially Lidar and drones, to directly or indirectly (through Photogrammetry) measure the height and or shape of land cover features, and shade that elevation surface.

This technique is most useful at producing realistic maps at relatively large scales, 1:5,000 to 1:50,000.

Resolution mixing or bumping

One challenge with shaded relief, especially at small scales (1:500,000 or less), is that the technique is very good at visualizing local (high-frequency) relief, but may not effectively show larger features. For example, a rugged area of hills and valleys will show as much or more variation than a large, smooth mountain. Resolution bumping is a hybrid technique developed by NPS cartographer Tom Patterson to mitigate this problem. A fine-resolution DEM is averaged with a heavily smoothed version (i.e., significantly coarser resolution). When the hillshading algorithm is applied to this, it has the effect of blending the fine details of the original terrain model with the broader features brought out by the smoothed model. This technique works best at small scales and in regions that are consistently rugged.

Oblique view

A three-dimensional view (projected onto a two-dimensional medium) of the surface of the Earth, along with the geographic features resting on it. Imagined aerial views of cities were first produced during the late Middle Ages, but these "bird's eye views" became very popular in the United States during the 1800s. The advent of GIS (especially recent advances in 3-D and global visualization) and 3-D graphics modeling software has made the production of realistic aerial views relatively easy, although the execution of quality Cartographic design on these models remains a challenge.

Raised-relief map

This is a map in which relief is shown as a three-dimensional object. The most intuitive way to depict relief is to imitate it at scale. Hand-crafted dioramas may date back to 200BCE in China, but mass production did not become available until World War II with the invention of vacuum-formed plastic maps, and computerized machining to create molds efficiently. Machining is also used to create large custom models from substrates such as high-density foam, and can even color them based on aerial photography by placing an inkjet printhead on the machining device. The advent of 3D printing has introduced a much more economical means to produce raised-relief maps, although most 3D printers are too small to efficiently produce large dioramas.

Rendering

Terrain rendering covers a variety of methods of depicting real-world or imaginary world surfaces. Most common terrain rendering is the depiction of Earth's surface. It is used in various applications to give an observer a frame of reference. It is also often used in combination with rendering of non-terrain objects, such as trees, buildings, rivers, etc.

There are two major modes of terrain rendering: top-down and perspective rendering. Top-down terrain rendering has been known for centuries in the way of cartographic maps. Perspective terrain rendering has also been known for quite some time. However, only with the advent of computers and computer graphics perspective rendering has become mainstream.

Structure

A typical terrain rendering application consists of a terrain database, a central processing unit (CPU), a dedicated graphics processing unit (GPU), and a display. A software application is configured to start at initial location in the world space. The output of the application is screen space representation of the real world on a display. The software application uses the CPU to identify and load terrain data corresponding to initial location from the terrain database, then applies the required transformations to build a mesh of points that can be rendered by the GPU, which completes geometrical transformations, creating screen space objects (such as polygons) that create a picture closely resembling the location of the real world.

Texture

There are a number of ways to texture the terrain surface. Some applications benefit from using artificial textures, such as elevation coloring, checkerboard, or other generic textures. Some applications attempt to recreate the real-world surface to the best possible representation using aerial photography and satellite imagery.

In video games, texture splatting is used to texture the terrain surface.

Generation

Main article: Scenery generatorThere are a great variety of methods to generate terrain surfaces. The main problem solved by all these methods is managing number of processed and rendered polygons. It is possible to create a very detailed picture of the world using billions of data points. However such applications are limited to static pictures. Most uses of terrain rendering are moving images, which require the software application to make decisions on how to simplify (by discarding or approximating) source terrain data. Virtually all terrain rendering applications use level of detail to manage number of data points processed by CPU and GPU. There are several modern algorithms for terrain surfaces generating.

Applications

Terrain rendering is widely used in computer games to represent both Earth's surface and imaginary worlds. Some games also have terrain deformation (or deformable terrain).

One important application of terrain rendering is in synthetic vision systems. Pilots flying aircraft benefit greatly from the ability to see terrain surface at all times regardless of conditions outside the aircraft.

Skeletal, structural, or break lines

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2014) |

Emphasizes hydrological drainage divide and watershed streams.

Forums and associations

Portrayal of relief is especially important in mountainous regions. The Commission on Mountain Cartography of the International Cartographic Association is the best-known forum for discussion of theory and techniques for mapping these regions.

See also

- Cartographic labeling

- Pictorial map

- Geomipmapping

- Geometry Clipmaps

- ROAM (Real-time optimally adapting mesh)

References

- Lobeck, A.K. (1921) A Physiographic Diagram of the United States, A.J. Nystrom & Co., digital scan at David Rumsey Map Collection, List No.7129.000

- ^ Raisz, Erwin (1948). General Cartography (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 103–123.

- Jenny, Bernhard; Patterson, Tom (2007). "Introducing Plan Oblique Relief" (PDF). Cartographic Perspectives (57): 21–40. doi:10.14714/CP57.279.

- Swisstopo, Conventional Signs Archived 2008-05-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Fundamentals of Cartography. Misra R. P. and A. Ramesh. Concept Publishing Company. 1989. pp. 389-390

- Patrick Kennelly & A. Jon Kimerling (2001) Modifications of Tanaka's Illuminated Contour Method, Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 28:2, 111-123.

- "RELIEF (TERRAIN) DEPICTION." UNBC GIS LAB: GIS & Remote Sensing. University of Northern British Columbia, n.d. Web. 28 Sept. 2013.

- Eduard Imhof (2007-06-01). Cartographic relief presentation. Esri Pr. ISBN 978-1-58948-026-1.

- Jenny, Bernhard; Hurni, Lorenz (2006). "Swiss-Style Colour Relief Shading Modulated by Elevation and by Exposure to Illumination". The Cartographic Journal. 43 (3): 198–207. Bibcode:2006CartJ..43..198J. doi:10.1179/000870406X158164.

- Tom Patterson, "See the light: How to make illuminated shaded relief in Photoshop 6.0," http://www.shadedrelief.com/illumination/ (accessed 30 October 2017).

- Huffman, Daniel P. (2014) Shaded Relief in Blender, 9th ICA Mountain Cartography Workshop

- Kennelly, J., & Stewart, J. (2006). A Uniform Sky Illumination Model to Enhance Shading of Terrain and Urban Areas. Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 33(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1559/152304006777323118.

- Blinn, James F. "Simulation of Wrinkled Surfaces", Computer Graphics, Vol. 12 (3), pp. 286-292 SIGGRAPH-ACM (August 1978)

- Patterson, Tom (2002). "Getting Real: Reflecting on the New Look of National Park Service Maps". Cartographic Perspectives (43): 43–56. doi:10.14714/CP43.536.

- Nighbert, Jeffrey (2000). "Using Remote Sensing Imagery to Texturize Layer Tinted Relief". Cartographic Perspectives (36): 93. doi:10.14714/CP36.827.

- Patterson, Tom., "Resolution bumping GTOPO30 in Photoshop: How to Make High-Mountains More Legible," http://www.shadedrelief.com/bumping/bumping.html (accessed 24 September 2012)

- Patterson, Tom (2005). "Looking Closer: A Guide to Making Bird's-eye Views of National Park Service Cultural and Historical Sites". Cartographic Perspectives (52): 59–75. doi:10.14714/CP52.379.

- Adams, Aaron (July 2019). A Comparative Usability Assessment of Augmented Reality 3-D Printed Terrain Models and 2-D Topographic Maps. New Mexico State University. Retrieved 17 April 2022 – via ProQuest.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stewart J. (1999), “Fast Horizon Computation at All Points of a Terrain With Visibility and Shading Applications”, IEEE Transactions on visualization and computer graphics 4(1).

- Bashkov E., Zori S., Suvorova I. (2000), “Modern Methods of Environment Visual Simulation”, In Simulationstechnik, 14. Symposium in Hamburg SCS, pp. 509-514. Europe BVBA, Ghent, Belgium,

- Bashkov E.A., Zori S.A. (2001), “Visual Simulation of an Earth Surface by Fast Horizon Computation Algorithm”, In Simulation und Visualisierung, pp. 203-215. Institut fur Simulation und Graphik, Magdeburg, Deutschland

- Ruzinoor Che Mat & Norani Nordin, 'Silhouette Rendering Algorithm Using Vectorisation Technique from Kedah Topography Maps', Proceeding 2nd National Conference on Computer Graphics and Multimedia (CoGRAMM’04), Selangor, December 2004. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/30969013/449317633605827_1.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1505553957&Signature=7GA1T7nvGM5BOhLQ0OCELIKVYbY%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3D3D_Silhouette_Rendering_Algorithms_using.pdf

External links

- Shaded Relief, a website by Tom Patterson

- Relief Shading, a website of the Institute of Cartography at ETH Zurich

- Misplaced Pages Graphic Lab, a tutorial on creating shaded relief maps using free and open source software

- Rendering a map using relief shading technique in Photoshop

- Virtual Terrain Project

- Underwater Relief Shading