| Revision as of 19:45, 27 May 2009 editDr.K. (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers110,824 editsm Reverted edits by 72.10.109.105 (talk) to last version by Tasoskessaris← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:02, 19 January 2025 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,460,005 edits Add: author-link1, authors 1-1. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by RafaelTLS | #UCB_webform | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ancient Semitic maritime civilization}} | |||

| {{otherusesof|Phoenicia}} | |||

| {{Infobox |

{{Infobox former country | ||

| | native_name = | |||

| |native_name = <span dir="rtl">]]]]</span> <br> {{Polytonic| Φοινίκη}} | |||

| | life_span = {{circa|2500}}{{snd}}64 BC | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Canaan | |||

| | |

| conventional_long_name = Phoenicia | ||

| | common_name = Phoenicia | |||

| |national_motto = | |||

| | era = ] | |||

| |continent = Asia | |||

| | government_type = ]s ruled by ], with varying degrees of ] or ]; oligarchic ] in ] after c. 480 BC<ref>''Carthage and the Carthaginians'', ], p. 16</ref> | |||

| |region = Near east | |||

| | year_start = 2500 BC<ref name="Bentley-2000">{{cite book|first1=Jerry H. |last1=Bentley|first2=Herbert F. |last2=Ziegler|title=Traditions & Encounters: From the Beginnings to 1500|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1qtiYjVlmDgC|year=2000|publisher=McGraw Hill|isbn=978-0-07-004949-9}}</ref> | |||

| |era = ] | |||

| | year_end = 64 BC | |||

| |government_type = ] (]s) | |||

| | date_event1 = 969 BC | |||

| |year_start = 1200 BC | |||

| | event1 = ] becomes dominant city-state under the reign of ] | |||

| |date_event1 = 969 BC | |||

| | event2 = ] founded (in Roman accounts by ]) | |||

| |event_start = Byblos becomes the predominant Phoenician center | |||

| | date_event2 = 814 BC | |||

| |event1 = Tyre, under the reign of Hiram I, becomes the dominant city-state | |||

| | p1 = Canaanites | |||

| |event2 = Pygmalion founds ] | |||

| | p2 = Hittite Empire | |||

| |date_event2 = 814 BC | |||

| | p3 = Egyptian Empire | |||

| |event_end = ] conquers Phoenicia | |||

| | s1 = Roman Syria{{!}}Syria (Roman province) | |||

| |year_end = 333 BC | |||

| | flag_s1 = | |||

| |date_end = | |||

| | image_map =Phoenician maritime expansions across the Mediterranean.jpg | |||

| |p1 = | |||

| | image_map_caption = Phoenician settlements and trade routes across the Mediterranean starting from around 800 BC.<ref name="Matisoo-Smith et al 2018">{{cite journal |last1=Matisoo-Smith |first1=E. |last2=Gosling |first2=A. L. |last3=Platt |first3=D. |last4=Kardailsky |first4=O. |last5=Prost |first5=S. |last6=Cameron-Christie |first6=S. |last7=Collins |first7=C. J. |last8=Boocock |first8=J. |last9=Kurumilian |first9=Y. |last10=Guirguis |first10=M. |last11=Pla Orquín |first11=R. |last12=Khalil |first12=W. |last13=Genz |first13=H. |last14=Abou Diwan |first14=G. |last15=Nassar |first15=J. |last16=Zalloua |first16=P. |title=Ancient mitogenomes of Phoenicians from Sardinia and Lebanon: A story of settlement, integration, and female mobility |journal=PLOS ONE |date=10 January 2018 |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=e0190169 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0190169|doi-access=free |pmid=29320542 |pmc=5761892 |bibcode=2018PLoSO..1390169M }}</ref> | |||

| |s1 = Achaemenid Empire | |||

| | capital = None; dominant cities were ], ] and ]{{sfn|Aubet|2001|pp=18, 44}} | |||

| |flag_s1 = Achaemenid Empire.jpg | |||

| | common_languages = ], ] | |||

| |image_map = Phoenicia map-en.svg | |||

| | religion = ] | |||

| |image_map_caption = Map of Phoenicia | |||

| | leader1 = ] | |||

| |capital = ]<small><br/>(1200 BC – 1000 BC)</small><br/>]<small><br/>(1000 BC - 333BC)</small> | |||

| | year_leader1 = {{circa|1800 BC}} | |||

| |latd= 34 |latm= 07 |latNS= N |longd= 35 |longm= 39 |longEW= E | |||

| | leader2 = ] | |||

| |common_languages = ], ], ] | |||

| | year_leader2 = 969–936 BC | |||

| |religion = ] | |||

| | leader3 = ] | |||

| |leader1 = ] | |||

| | year_leader3 = 820–774 BC | |||

| |year_leader1 = ca. 1000 BC | |||

| | title_leader = Major kings of Phoenician cities | |||

| |leader2 = ] | |||

| | demonym = | |||

| |year_leader2 = 969 BC - 936 BC | |||

| |leader3 = ] | |||

| |year_leader3 = 820 BC - 774 BC | |||

| |title_leader = King | |||

| |legislature = | |||

| |stat_year1 = | |||

| |last= | |||

| |stat_area1 = | |||

| |stat_year2 = | |||

| |stat_area2 = | |||

| |stat_year3 = | |||

| |stat_area3 = | |||

| |stat_year4 = | |||

| |stat_area4 = | |||

| |stat_year1 = 1200 BC<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bartleby.com/67/109.html|title=Phoenicia|first=The Rise of Sidon|date=2001|work=The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Company|pages=1|language=English|accessdate=2008-12-11}}</ref> | |||

| |stat_pop1 = 200,000 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Phoenicia''' (]: <span dir="rtl">]]]]</span>, Canaan or Kana'an, nonstandardly, ''Phenicia''; {{pronEng|fɨˈnɪʃiə}}<ref>]</ref>, {{lang-el|Φοινίκη}}: Phoiníkē, {{lang-la|Phœnicia}}) was an ancient ] centered in the north of ancient ], with its heartland along the coastal regions of modern day ], extending to parts of ], ] and the ]. Phoenician civilization was an enterprising ] that spread across the ] during the period 1550 BCE to 300 BCE. Though ancient boundaries of such city-centered cultures fluctuated, the city of ] seems to have been the southernmost. ] (modern day Sarafand) between ] and Tyre, is the most thoroughly excavated city of the Phoenician homeland. The Phoenicians often traded by means of a ], a man-powered sailing vessel and are credited with the invention of the ].<ref>{{cite book | last = Casson | first = Lionel | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World | publisher = The Johns Hopkins University Press | date = December 1 1995 | location = | pages = 57–58 | url = http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=sDpMh0gK2OUC&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq=+bireme+Assyrian+Casson&ots=SzGT0dkwlq&sig=zyJHXe3O3BzTfuNZjMtm7NaoXNw#PPA57,M1 | doi = | id = | isbn = 978-0801851308 }}</ref> | |||

| The '''Phoenicians''' were an ] group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the ] region of the ], primarily modern ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Malaspina |first=Ann |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pfop0v79y7gC&q=phoenicia+lebanon&pg=PA19 |title=Lebanon |date=2009 |publisher=Infobase Publishing |isbn=978-1-4381-0579-6}}</ref> They developed a ] civilization which expanded and contracted throughout history, with the core of their culture stretching from ] in modern ] to ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Meir Edrey |title=Phoenician Identity in Context: Material Cultural Koiné in the Iron Age Levant |publisher=Ugarit-Verlag – Buch- und Medienhandel Münster |year=2019 |isbn=978-3-86835-282-5 |series=Alter Orient und Altes Testament |volume=469 |location=Germany |pages=23–24}}</ref> The Phoenicians extended their cultural influence through trade and colonization throughout the Mediterranean, from ] to the ], evidenced by thousands of ]. | |||

| It is uncertain to what extent the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single ethnicity. Their civilization was organized in ], similar to ]. Each city-state was an independent unit politically, although they could come into conflict, be dominated by another city-state, or collaborate in leagues or alliances. Tyre and Sidon were the most powerful of the Phoenician states in the ], but were not as powerful as the North African ones. {{Fact|date=July 2008}} | |||

| The Phoenicians directly succeeded the ] ]ites, continuing their cultural traditions after the decline of most major ] cultures in the ] and into the ] without interruption. They called themselves Canaanites and referred to their land as Canaan, but the territory they occupied was notably smaller than that of Bronze Age Canaan.{{sfn|Gates|2011|pp=189–190}} The name ''Phoenicia'' is an ] ] that did not correspond precisely to a cohesive culture or society as it would have been understood natively.{{sfn|Quinn|2017|p=xviii}}{{sfn|Lehmann|2024|p=75}} Therefore, the division between Canaanites and Phoenicians around 1200 BC is regarded as a modern and artificial construct.{{sfn|Gates|2011|pp=189–190}}{{sfn|Quinn|2017|p=16-24}} | |||

| The Phoenicians were also the first state-level society to make extensive use of the ], and the Canaanite-Phoenician alphabet is generally believed to be the ancestor of almost all modern alphabets. Phoenicians spoke the ], which belongs to the group of ] in the ]. Through their maritime trade, the Phoenicians spread the use of the ] to ] and ] where it was adopted by the ], who later passed it on to the ] and ].<ref>Edward Clodd, ''Story of the Alphabet'' (Kessinger) 2003:192ff</ref> In addition to their many inscriptions, there were a considerable number of other types of written sources left by the Phoenicians, which have not survived. '']'' by ] quotes extensively from ] and ]. | |||

| The Phoenicians, known for their prowess in trade, seafaring and navigation, dominated commerce across classical antiquity and developed an expansive maritime trade network lasting over a millennium. This network facilitated cultural exchanges among major ], such as ], ] and ]. The Phoenicians established colonies and trading posts across the Mediterranean; ], a settlement in northwest Africa, became a major civilization in its own right in the seventh century BC. | |||

| The Phoenicians were organized in ]s, similar to those of ], of which the most notable were ], ], and ].{{sfn|Aubet|2001|p=17}} Each city-state was politically independent, and there is no evidence the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single nationality.{{sfn|Quinn|2017|pp=201–203}} While most city-states were governed by some form of ]ship, merchant families probably exercised influence through ]. After reaching its zenith in the ninth century BC, the Phoenician civilization in the eastern Mediterranean gradually declined due to external influences and conquests such as by the ] and ]. Yet, their presence persisted in the central, southern and western Mediterranean until the ] in the mid-second century BC. | |||

| The Phoenicians were long considered a lost civilization due to the lack of indigenous written records; ] were first discovered by modern scholars in the 17th and 18th centuries. Only since the mid-20th century have historians and ] been able to reveal a complex and influential civilization.{{sfn|Markoe|2000|pp=10–12}} Their best known legacy is the world's ], whose origin was connected to the ],{{sfn|Coulmas|1996}} and which was transmitted across the Mediterranean and used to develop the ], ] and ] and in turn the ] and ]s.{{sfn|Markoe|2000|page=111}}{{sfn|Fischer|2004|p=153}} The Phoenicians are also credited with innovations in shipbuilding, navigation, industry, agriculture, and government. Their international trade network is believed to have fostered the economic, political, and cultural foundations of ].{{sfn|Niemeyer|2004|pp=245–250}}<ref>Scott, John C. (2018) "", Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 78 : No. 78, Article 4.</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| Being a society of independent city states, the Phoenicians apparently did not have a term to denote the land of Phoenicia as a whole;<ref>Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. In ''Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History''. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–2024. . (October 2004)</ref> instead, demonyms were often derived from the name of the city a person hailed from (e.g., ''Sidonian'' for ], ''Tyrian'' for ], etc.) There is no evidence that the peoples living in the area denoted as ''Phoenicia'' identified as "Phoenicians" or shared a common identity, although they may have referred to themselves as "Canaanites".{{sfn|Killebrew|2022|p=42}} Krahmalkov reconstructs the ] (dated to {{circa|900}} BC by ]) as containing a reference to the Phoenician homeland, calling it ''Pūt'' (]: 𐤐𐤕).<ref name=Honeyman>Honeyman, A. M. "" Iraq, vol. 6, no. 2, 1939, pp. 104–108 , number 8.</ref>{{sfn|Krahmalkov|2001|pp=1–2}} | |||

| Furthermore, as late as the first century BC, a distinction appears to have been made between 'Syrian' and 'Phoenician' people, as evidenced by the epitaph of ]: 'If you are a Syrian, Salam! If you are a Phoenician, Naidius! If you are a Greek, Chaire! (Hail), and say the same yourself.'<ref>Linda Jones Hall, ''Roman Berytus: Beirut in late antiquity'' (2004), p 131.</ref> | |||

| Obelisks at ] contain references to a "land of '']''", ''fnḫw'' being the plural form of ''fnḫ'', the Ancient Egyptian word for 'carpenter'. This "land of carpenters" is generally identified as Phoenicia, given that Phoenicia played a central role in the lumber trade of the Levant.<ref>James P. Allen (2010) ''Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs'', 2nd edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-521-51796-6}}, p. 345.</ref> As an ], ''fnḫw'' was evidently borrowed into Greek as {{lang|grc|φοῖνιξ}}, ''{{lang|grc-Latn|phoînix}}'', which meant variably 'Phoenician person', '], ]' or ']'. ] used it with each of these meanings.<ref>{{cite web |title=Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, φοῖνιξ |url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0057:entry=foi=nic |access-date=2017-02-03 |website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref> The word is already attested in ] script of ] from the 2nd millennium BC, as ''po-ni-ki-jo''. In those records, it means 'crimson' or 'palm tree' and does not denote a group of people.{{sfn|Quinn|2017|page=48}} The name ''Phoenicians'', like ] ''{{lang|la|Poenī}}'' (adj. ''{{lang|la|poenicus}}'', later ''{{lang|la|pūnicus}}''), comes from ] {{lang|grc|Φοινίκη}}, ''{{lang|grc-Latn|Phoiníkē}}''. According to Krahmalkov, '']'', a Latin comedic play written in the early 2nd century BC, appears to preserve a ] term for the Phoenician/Punic language which may be reconstructed as ''Pōnnīm'',{{sfn|Krahmalkov|2001|pp=1–2}} a point disputed by Joseph Naveh, a professor of West Semitic ] and ] at the ],<ref name="Naveh2001">{{cite journal |last1=Naveh |first1=Joseph |title=Review of A Phoenician–Punic Grammar (Handbook of Oriental Studies, Section One: The Near and Middle East 54) |journal=Israel Exploration Journal |date=2001 |volume=51 |issue=1 |pages=113–115 |jstor=27926965 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/27926965 |issn=0021-2059 |quote=Krahmalkov found that in the Punic text of Plautus's ''Poenulus'' the Phoenician/Punic language is called ''ponnim''. In order to corroborate this Krahmalkov emends parts of Psalms 45:12-14 and reads:השתחוי לו בת צר // כבדה בת מלך פנימה 'Show him respect, O daughter of Tyre, // Honor him, O daughter of the King the Phoenicians (Ponnima!)' Krahmalkov's eagerness for innovative readings results sometimes in nonsense.}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Main|Phoenician history}} | |||

| ===Origins: 2300-1200 BC=== | |||

| Since little has survived of Phoenician records or ], most of what is known about their origins and history comes from the accounts of other civilizations and inferences from their material culture excavated throughout the Mediterranean. The scholarly consensus is that the Phoenicians' period of greatest prominence was 1200 BC to the end of the Persian period (332 BC).<ref>{{Harvnb|Jigoulov|2021|p=13}}</ref> | |||

| {{History of Lebanon (ancient)}} | |||

| It is debated among historians and archaeologists whether Phoenicians were actually distinct from the broader group of Semitic-speaking peoples known as ]ites.<ref name="Scott-2018">{{cite journal |last=Scott |first=John C |date=2018 |title=The Phoenicians and the Formation of the Western World |url=https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol78/iss78/4 |journal=Comparative Civilizations Review |volume=78 |issue=78}}</ref>{{sfn|Quinn|2017|pp=24, 204}} Historian Robert Drews believes the term "Canaanites" corresponds to the ethnic group referred to as "Phoenicians" by the ancient Greeks;<ref>{{cite journal |last=Drews |first=Robert |date=1998 |title=Canaanites and Philistines |url=https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/030908929802308104 |journal=Journal for the Study of the Old Testament |volume=23 |issue=81 |pages=39–61 |doi=10.1177/030908929802308104 |s2cid=144074940}}</ref> archaeologist Jonathan N. Tubb argues that "]ites, ], ], and Phoenicians undoubtedly achieved their own cultural identities, and yet ethnically they were all Canaanites", "the same people who settled in farming villages in the region in the 8th millennium BC".{{sfn|Tubb|1998|pp=13–14}} Brian R. Doak states that scholars use "Phoenicians" as a short-hand for "Canaanites living in a set of cities along the northern Levantine coast who shared a language and material culture in the Iron I–II period and who also developed an organized system of colonies in the western Mediterranean world".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Doak |first=Brian R. |url=https://academic.oup.com/book/33589/chapter/288065678 |title=Ancient Israel's Neighbors |date=2020 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=9780190690632}}</ref> | |||

| Archaeologists argue that the Phoenicians are simply the descendants of coastal-dwelling Canaanites, who over the centuries developed a particular seagoing culture and skills. Other suggestions are that Phoenician culture must have been inspired from external sources (Egypt, North Africa etc.), that the Phoenicians were sea-traders from the ] who co-opted the Canaanite population; or that they were connected with the ], or the ] or the ] further south; or even that they represent the maritime activities of the coastal ] tribes like ], who from the Song of Deborah in Judges, are listed as being "amongst their ships". | |||

| ], ]; now in Archaeological Museum of Cádiz. The sarcophagus is thought to have been designed and paid for by a Phoenician merchant, and made in Greece with Egyptian influence.]] | |||

| The Mediterranean Phoenician - Aramaic derivative 'Semitic language' gave some evidence of invasion at the site of Byblos, which may suggest origins in the highly disputed 'wave of Semitic migration' that hit the ] between ca. 2300 and 2100 BC, some scholars, including ], believe that the Phoenicians' ethnogenesis included prior non-Semitic people of the area, suggesting a mixture between two populations. Both Sumerian and Akkadian armies had reached the Mediterranean in this area from the beginning of recorded history, but very little is known of Phoenicia before it was conquered by ] of Egypt around 1500 BC. The ] (ca. 1411-1358 BC) reveals that ] and ] were defeating the Phoenician cities that had been vassals to Egypt, especially ] of Byblos and ]/Abimelech of Tyre, but between 1350 and 1300 BC Phoenicia was reconquered by Egypt. Over the next century ] flourished, but was permanently destroyed at the end of it (ca. 1200 BC). | |||

| The Phoenician ] is largely unknown.<ref name="Jig2021_18">{{harvnb|Jigoulov|2021|p=18}}</ref> The two most important sites are ] and Sidon-Dakerman (near Sidon), although, as of 2021, well over a hundred sites remain to be excavated, while others that have been are yet to be fully analysed.<ref name="Jig2021_18" /> The ] was a generally peaceful time of increasing population, trade, and prosperity, though there was competition for natural resources.<ref name="Jig2021_20" /> In the ], rivalry between Egypt, the Mittani, the Hittites, and Assyria had a significant impact on Phoenician cities.<ref name="Jig2021_20">{{harvnb|Jigoulov|2021|pp=18–9}}</ref> | |||

| In terms of archaeology, language, and religion, there is little to set the Phoenicians apart as markedly different from other local cultures of Canaan, because they were Canaanites themselves. However, they are unique in their remarkable seafaring achievements. Indeed, in the ] of the ] they call themselves ''Kenaani'' or''Kinaani'' (Canaanites). Note, however, that the Amarna letters predate the invasion of the ] by over a century. Much later in the ], ] writes that Phoenicia was formerly called ''χνα'', a name ] later adopted into his mythology as his eponym for the Phoenicians: "Khna who was afterwards called Phoinix". Egyptian seafaring expeditions had already been made to ] to bring back "]" as early as the ]. | |||

| ===Origins=== | |||

| Stories of their emigrating from various places to the eastern Mediterranean are probably founded in 'oral fact', but researchers are pursuing DNA tests to verify this assertion. ]'s account (written c. 440 BC) refers to the Io and Europa myths. (''History,'' I:1). | |||

| {{Main|Canaan|Retjenu|Prehistory of the Levant}} | |||

| The Canaanite culture that gave rise to the Phoenicians apparently developed ''in situ'' from the earlier ] ] culture. The Ghassulian culture itself developed from the ], which in turn developed from a fusion of their ancestral ] and ] cultures with ] (PPNB) farming cultures. These practiced the ] during the ], which led to the ] in the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Zarins |first=Juris |year=1992 |chapter=Pastoral Nomadism in Arabia: Ethnoarchaeology and the Archaeological Record—A Case Study |editor-first=O. |editor-last=Bar-Yosef |editor2-first=A. |editor2-last=Khazanov |title=Pastoralism in the Levant |location=Madison |publisher=Prehistory Press |isbn=0-9629110-8-9 }}</ref> The Late Bronze Age state of ] is considered Canaanite,{{sfn|Tubb|1998|p=73}} even though the ] does not belong to the ] proper,<ref>{{Cite book |first=Roger |last=Woodard |year=2008 |title=The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia |location=New York |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-68498-9 }}</ref><ref name="Naveh-1987"> | |||

| {{Cite book |first=Joseph |last=Naveh |year=1987 |chapter=Proto-Canaanite, Archaic Greek, and the Script of the Aramaic Text on the Tell Fakhariyah Statue |editor1-last=Miller |title=Ancient Israelite Religion |publisher=Fortress Press |display-editors=etal |isbn=0-8006-0831-3 |chapter-url-access=registration |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/ancientisraelite00unse }}. {{harvp|Coulmas|1996}}.</ref> and some of the texts on clay tablets discovered there indicate that the inhabitants of Ugarit did not consider themselves Canaanites.{{sfn|Tubb|1998|pp=16, 72}} | |||

| The fourth-century BC Greek historian ] claimed that the Phoenicians had migrated from the ] around 2750 BC and the first-century AD geographer ] reports a claim that they came from Tylos and Arad (] and ]).<ref>Herodotos ''Histories'' 1.1, 2.44 & 7.89; Strabo, ''Geography'' 16.3.4.</ref><ref name="Bowersock, G.W.-1986">{{cite book |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2hmbc9evgB0C&pg=PA401 |title=Bahrain Through The Ages – the Archaeology |publisher=Routledge |year=1986 |isbn=0-7103-0112-X |chapter=Tylos and Tyre. Bahrain in the Graeco-Roman World |editor-last2=Rice |editor-first2=Michael |author=Bowersock, G.W. |editor-last1=Khalifa |editor-first1=Haya Ali |pages=401–2 }}</ref><ref name="Rice, Michael-1994">{{cite book|title=The Archaeology of the Arabian Gulf|publisher=Routledge|year=1994|isbn=0-415-03268-7 |author=Rice, Michael|page=20}}</ref><ref name="R. A. Donkin-1998">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=leHFqMQ9mw8C&pg=PA48 |title=Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-fishing : Origins to the Age of Discoveries, Volume 224 |page=48 |author=R. A. Donkin|isbn=0-87169-224-4 |year=1998 |publisher=American Philosophical Society }}</ref> Some archaeologists working on the ] have accepted these traditions and suggest a migration connected with the collapse of the ] {{circa|1750}} BC.<ref name="Bowersock, G.W.-1986"/><ref name="Rice, Michael-1994"/><ref name="R. A. Donkin-1998"/> However, most scholars reject the idea of a migration; archaeological and historical evidence alike indicate millennia of population continuity in the region, and recent genetic research indicates that present-day Lebanese derive most of their ancestry from a Canaanite-related population.<ref name="Habercetera">{{cite journal |title=Continuity and Admixture in the Last Five Millennia of Levantine History from Ancient Canaanite and Present-Day Lebanese Genome Sequences |journal=American Journal of Human Genetics |year=2017 |doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.013 |pmid=28757201|doi-access=free |last1=Haber |first1=Marc |last2=Doumet-Serhal |first2=Claude |last3=Scheib |first3=Christiana |last4=Xue |first4=Yali |last5=Danecek |first5=Petr |last6=Mezzavilla |first6=Massimo |last7=Youhanna |first7=Sonia |last8=Martiniano |first8=Rui |last9=Prado-Martinez |first9=Javier |last10=Szpak |first10=Michał |last11=Matisoo-Smith |first11=Elizabeth |last12=Schutkowski |first12=Holger |last13=Mikulski |first13=Richard |last14=Zalloua |first14=Pierre |last15=Kivisild |first15=Toomas |last16=Tyler-Smith |first16=Chris |volume=101 |issue=2 |pages=274–282 |pmc=5544389 }}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|According to the ] best informed in history, the Phoenicians began the quarrel. These people, who had formerly dwelt on the shores of the ], having migrated to the Mediterranean and settled in the parts which they now inhabit, began at once, they say, to adventure on long voyages, freighting their vessels with the wares of Egypt and Assyria...}} | |||

| ===Emergence during the Late Bronze Age (1479–1200 BC)=== | |||

| An example of a 19th century view is that of ] who thought that the ancient Phoenicians were of Cushite or Hamite origin. Speaking of their stupendous architectural remains, he wrote:- The Cushite origin of these cities is so plain that those most influenced by the strange monomania which transforms the Phoenicians into Semites now admit that the Cushites were the civilizers of Phoenicia. “Prehistoric Nations” pg 145. | |||

| The first known account of the Phoenicians relates the conquests of Pharaoh ] (1479–1425 BC), including the subjugation of those the Egyptians called '']'' ('carpenters').{{sfn|Bresciani|1997|p=233}} The Egyptians targeted the coastal cities such as Byblos, Arwad, and Ullasa for their crucial geographic and commercial links with the interior (via the ] and the ]). The cities provided Egypt with access to Mesopotamian trade and abundant stocks of the region's ], of which there was no equivalent in the Egyptian homeland. {{sfn|Markoe|2000|pp=1–19}} ] himself visited Sidon, where the purchase of lumber from Lebanon was arranged.{{sfn|Bryan|2000|p=79}} | |||

| By the mid-14th century BC, the Phoenician city-states were considered "favored cities" by the Egyptians. Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and Byblos were regarded as the most important. The Phoenicians had considerable autonomy, and their cities were reasonably well developed and prosperous. Byblos was the leading city; it was a center for bronze-making and the primary terminus of trade routes for precious goods such as ] and ] from as far east as ]. Sidon and Tyre also commanded the interest of Egyptian governmental officials,{{sfn|Cohen|2000|p=94}} beginning a pattern of commercial rivalry that would span the next millennium. | |||

| TV journalist ] asserts that, because the Phoenicians' legendary sailing abilities are not well attested before the invasions of the ] around 1200 BC, that these Sea Peoples would have merged with the local population to produce the Phoenicians, whom he says gained these abilities rather suddenly at that time. There is also archaeological evidence that the Philistines, often thought of as related to the Sea Peoples, were culturally linked to ] Greeks, who were also known to be great sailors even in this period. | |||

| The ] report that from 1350 to 1300 BC, neighboring ] and ] were capturing Phoenician cities, especially in the north. Egypt subsequently lost its coastal holdings from Ugarit{{sfn|Murnane|2000|p=110}} in northern Syria to Byblos near central Lebanon. | |||

| The question of the Phoenicians' origin persists. Archaeologists have pursued the origin of the Phoenicians for generations, basing their analyses on excavated sites, the remains of material culture, contemporary texts set into contemporary contexts, as well as ]. In some cases, the debate is characterized by modern cultural agendas. Ultimately, the origins of the Phoenicians are still unclear: where they came from and just when (or if) they arrived, and under what circumstances, are all still energetically disputed. | |||

| ===Ascendance and high point (1200–800 BC)=== | |||

| ] of the ] has conducted ] studies which demonstrate that male populations of ], ], ] and other areas which are past Phoenician settlements, share a common m89 chromosome Y type,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0410/feature2/online_extra.html|publisher=National Geographic|title=In the Wake of the Phoenicians: DNA study reveals a Phoenician-Maltese link |date=] ]}}</ref> while male populations which are related with the Minoans or with the Sea Peoples have completely different genetic markers. This implies that Minoans and Sea Peoples probably didn't have any ancestral relation with the Phoenicians. | |||

| Sometime between 1200 and 1150 BC, the ] severely weakened or destroyed most civilizations in the region, including those of the Egyptians and the Hittites. The Phoenicians were able to survive and navigate the challenges of the crisis, and by 1230 BC city-states such as Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos maintained political independence, asserted their maritime interests, and enjoyed economic prosperity. | |||

| The period sometimes described as a "Phoenician renaissance" had begun, and by the end of the 11th century BC, an alliance formed between Tyre and Israel had created a new geopolitical status quo in the Levant. Commercial maritime activity now involved not just mercantilism, but colonization as well, and Phoenician expansion into the Mediterranean was well under way.{{sfn|Stieglitz|1990|pp=9, 11}} The Phoenician city-states during this time were Tyre, Sidon, Byblos, Aradus, Beirut, and Tripoli. They filled the power vacuum caused by the Late Bronze Age collapse and created a vast mercantile network.<ref name="Scott-2018" /> | |||

| The recovery of the Mediterranean economy can be credited to Phoenician mariners and merchants, who re-established long-distance trade between Egypt and Mesopotamia in the 10th century BC.<ref name="Bentley-1999">{{cite journal|first=Jerry H.|last=Bentley|title=Sea and Ocean Basins as Frameworks for Historical Analysis|journal=Geographical Review|volume= 89|issue=2|year=1999|pages=215–219|doi=10.1111/j.1931-0846.1999.tb00214.x}}</ref> | |||

| In 2004, two ] educated geneticists and leading scientists of the National Geographic ], Dr. Pierre Zalloua and Dr. ] identified the haplogroup of the Phoenicians as ] ], with avenues open for future research. As Dr. Wells commented, "The Phoenicians were the Canaanites—and the ancestors of today's Lebanese."<ref> - National Geographic Magazine, October 2004 - The Malta Independent Online. Accessed on March 10, 2008</ref> The male populations of Tunisia and Malta were also included in this study and shown to share overwhelming genetic similarities with the Lebanese-Phoenicians. In 2008, scientists from the Genographic Project announce that "as many as 1 in 17 men living today on the coasts of North Africa and southern Europe may have a Phoenician direct male-line ancestor." See ]. | |||

| Early in the ], the Phoenicians established ports, warehouses, markets, and settlements all across the Mediterranean and up to the southern Black Sea. Colonies were established on ], ], the ], ], and ], as well as the coasts of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula.<ref>{{cite book|last=Barnes|first=William H.|title=Studies in the Chronology of the Divided Monarchy of Israel|location=Atlanta|publisher=Scholars Press|year=1991|pages=29–55}}</ref> Phoenician ] dated to this period bears lead isotope ratios matching ores in Sardinia and Spain, indicating the extent of Phoenician trade networks.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Chamorro|first1=Javier G.|year=1987|title=Survey of Archaeological Research on Tartessos|journal=American Journal of Archaeology|volume=91|issue=2|pages=197–232|doi=10.2307/505217|jstor=505217|s2cid=191378720 }}</ref> | |||

| ===High point: 1200–800 BC=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] remarked in ''The Perspective of the World'' that Phoenicia was an early example of a "world-economy" surrounded by empires. The high point of Phoenician culture and seapower is usually placed ca. 1200–800 BC. | |||

| By the tenth century BC, Tyre rose to become the richest and most powerful Phoenician city-state, particularly during the reign of ] ({{circa|969–936}} BC). The expertise of Phoenician artisans sent by Hiram I of Tyre in significant construction projects during the reign of ], the King of Israel, is alluded to in the Hebrew Bible,{{sfn|Gates|2011|pp=189–190}} although the reliability of this biblical history is dismissed by scientific researchers in modern times.{{sfn|Na'aman|2019|p=75}} | |||

| Many of the most important Phoenician settlements had been established long before this: ], ], ], ], ], and ] all appear in the Amarna tablets; and indeed, the first appearance in archaeology of cultural elements clearly identifiable with the Phoenician zenith is sometimes dated as early as the third millennium BC. | |||

| During the rule of the priest ] (887–856 BC), Tyre expanded its territory as far north as Beirut and into part of Cyprus; this unusual act of aggression was the closest the Phoenicians ever came to forming a unitary territorial state. Once his realm reached its largest territorial extent, Ithobaal declared himself "King of the Sidonians", a title that would be used by his successors and mentioned in both Greek and Jewish accounts.{{sfn|Boyes|2012|p=33}} | |||

| This league of independent ] ports, with others on the islands and along other coasts of the ], was ideally suited for trade between the ] area, rich in natural resources, and the rest of the ancient world. Suddenly, during the early ], in around 1200 BC an unknown event occurred, historically associated with the appearance of the ] from the north who were perhaps driven south by crop failures and mass starvation following the eruption at the island Thera. The powers that had previously dominated the area, notably the ]ians and the ], became weakened or destroyed; and in the resulting power vacuum a number of Phoenician cities established themselves as significant maritime powers. | |||

| The Late Iron Age saw the height of Phoenician shipping, mercantile, and cultural activity, particularly between 750 and 650 BC. The Phoenician influence was visible in the "orientalization" of Greek cultural and artistic conventions.<ref name="Scott-2018" /> Among their most popular goods were fine textiles, typically dyed with ]. Homer's '']'', which was composed during this period, references the quality of Phoenician clothing and metal goods.<ref name="Scott-2018" /> | |||

| Authority seems to have stabilized because it derived from three power-bases: the king; the temple and its priests; and councils of elders. Byblos soon became the predominant center from where they proceeded to dominate the Mediterranean and Erythraean (Red) Sea routes, and it is here that the first inscription in the Phoenician alphabet was found, on the sarcophagus of ] (ca. 1200 BC). However, by around 1000 BC Tyre and Sidon had taken its place, and a long hegemony was enjoyed by Tyre beginning with ] (969-936 BC), who subdued a rebellion in the colony of ]{{Fact|date=February 2007}}. The priest ] (887-856 BC) ruled Phoenicia as far north as Beirut, and part of Cyprus. ] was founded in 814 BC under ] (820-774 BC). The collection of city-kingdoms constituting Phoenicia came to be characterized by outsiders and the Phoenicians themselves as ''Sidonia'' or ''Tyria'', and Phoenicians and Canaanites alike came to be called ''Zidonians'' or ''Tyrians'', as one Phoenician conquest came to prominence after another. | |||

| === |

===Foundation of Carthage=== | ||

| {{Main|Carthage|Ancient Carthage|History of Carthage|Punic Wars}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Carthage was founded by Phoenicians coming from Tyre, probably to provide an anchorage and supplies to the Tyrian merchants in their voyages.{{sfn|Warmington|1960|pp=24}} The city's name in ], {{lang|phn-Latn|Qart-Ḥadašt}} {{nowrap|({{script|Phnx|𐤒𐤓𐤕 𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕}})}}, means 'New City'.{{sfn|Charles-Picard|Picard|1968|pp=28–35}} There is a tradition in some ancient sources, such as ], for an "early" foundation date of around 1215 BC—before the ] in 1180 BC. However, ], a Greek historian from Sicily {{circa|300}} BC, places the foundation of Carthage in 814 BC, which is the date generally accepted by modern historians.{{sfn|Lancel|1995|pp=20–23}} Legend, including ]'s ], assigns the founding of the city to Queen ]. Carthage would grow into a multi-ethnic empire spanning North Africa, Sardinia, Sicily, Malta, the Balearic Islands, and southern Iberia, but would ultimately be destroyed by Rome in the ] (264–146 BC). It was eventually rebuilt as a Roman city by ] in the period from 49 to 44 BC, with the official name ''Colonia Iulia Concordia Carthago''.<ref name="Hoyos2020">{{cite book |last1=Hoyos |first1=Dexter |title=Carthage: A Biography |year=2020 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-32816-5 |page=88 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DGwJEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT88}}</ref> | |||

| ===Vassalage under the Assyrians and Babylonians (858–538 BC)=== | |||

| ] conquered Phoenicia in 539 BC. Phoenicia was divided into four vassal kingdoms by the Persians: ], ], ], and ], and prospered, furnishing fleets for the Persian kings. However, Phoenician influence declined after this. It is also reasonable to suppose that much of the Phoenician population migrated to ] and other colonies following the Persian conquest, as it is roughly then (under King ]) that we first hear of Carthage as a powerful maritime entity. In 350 or 345 BC a rebellion in Sidon led by ] was crushed by ], and its destruction was described, perhaps too dramatically, by ]. | |||

| {{Main|Phoenicia under Assyrian rule|Phoenicia under Babylonian rule}} | |||

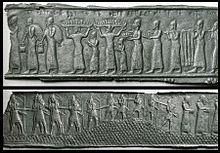

| ]n palace gate depicting the collection of tribute from the Phoenician cities of ] and ] (859–824 BC). British Museum.]] | |||

| As mercantile city-states concentrated along a narrow coastal strip of land, the Phoenicians lacked the size and population to support a large military. Thus, as neighboring empires began to rise, the Phoenicians increasingly fell under the sway of foreign rulers, who to varying degrees circumscribed their autonomy.{{sfn|Woolmer|2021|pp=49–50}} | |||

| ] took Tyre in 332 BC following the ]. Alexander was exceptionally harsh to Tyre, executing 2000 of the leading citizens, but he maintained the king in power. He gained control of the other cities peacefully: the ruler of Aradus submitted; the king of Sidon was overthrown. The rise of ] gradually ousted the remnants of Phoenicia's former dominance over the Eastern Mediterranean trade routes, and Phoenician culture disappeared entirely in the motherland. However, its North African offspring, Carthage, continued to flourish, mining iron and ]s from Iberia, and using its considerable naval power and mercenary armies to protect its commercial interests, until it was finally destroyed by Rome in 146 BC at the end of the ]. | |||

| The Assyrian domination of Phoenicia began with King ]. He rose to power in 858 BC and began a series of campaigns against neighboring states. Although he did not invade Phoenicia and maintained good relations with the Phoenician cities,{{sfn|Aubet|2008|p=184}} he demanded tribute from the "kings of the seacoast", a group which probably included the Phoenician city-states.{{sfn|Woolmer|2021|p=44}} According to Aubet, Tyre, Sidon, Arwad and Byblos paid tribute in bronze and bronze vessels, tin, silver, gold, ebony and ivory.{{sfn|Aubet|2008|p=184}} Initially, they were not annexed outright—they were allowed a certain degree of freedom.{{sfn|Hodos|2011|p=25}} This changed in 744 BC with the ascension of ]. By 738 BC, most of the Levant, including northern Phoenicia, were annexed;{{sfn|Faust|2021|p=37}}{{sfn|Bunnens|2022|p=67}} only Tyre and Byblos, the most powerful city-states, remained tributary states outside of direct Assyrian control.{{sfn|Elayi|2018|p=149}} | |||

| As for the Phoenician homeland, following Alexander it was controlled by a succession of Hellenistic rulers: ] (323 BC), ] (320), ] (315), ] (301), and ] (296). Between 286 and 197 BC, Phoenicia (except for Aradus) fell to the Ptolemies of Egypt, who installed the high priests of ] as vassal rulers in Sidon (], ], ]). In 197 BC, Phoenicia along with Syria reverted to the Seleucids, and the region became increasingly Hellenized, although Tyre actually became autonomous in 126 BC, followed by Sidon in 111. Syria, including Phoenicia, were seized by king ] from 82 until 69 BC when he was defeated by ], and in 65 BC ] finally incorporated it as part of the Roman province of Syria. | |||

| Tyre, Byblos, and Sidon all rebelled against Assyrian rule. In 721 BC, ] besieged Tyre and crushed the rebellion. His successor ] suppressed further rebellions across the region. During the seventh century BC, Sidon rebelled and was destroyed by ], who enslaved its inhabitants and built a new city on its ruins. By the end of the century, the Assyrians had been weakened by successive revolts, which led to their destruction by the ].{{citation needed|date=September 2024}} | |||

| ==Trade== | |||

| ] | |||

| The Babylonians, formerly vassals of the Assyrians, took advantage of the empire's collapse and rebelled, quickly establishing the ] in its place. Phoenician cities revolted several times throughout the reigns of the first Babylonian King, ] (626–605 BC), and his son ] ({{circa|605}} – {{circa|562}} BC). Nebuchadnezzar besieged Tyre, his siege commonly having been thought to have lasted thirteen years, although the city was not destroyed and suffered little damage. The consensus opinion in contemporary Phoenician historiography is that the thirteen-year siege began soon after the conquest of Jerusalem in 587 BC, and lasted from 585 BC through 573 BC. Among the writings of ancient historians, this detail about the length of the Nebuchadnezzar II's supposed thirteen-year siege of Tyre in the early sixth century BC can be found only in Josephus' first century writings, recorded almost 700 years after the date of the purported event. Helen Dixon proposes that the putative 'thirteen-year' siege was more likely several small-scale interventions in the region, or a limited blockade between the land-side city and its port.{{sfn|Dixon|2022|pp=165–170}} | |||

| The Phoenicians were amongst the greatest traders of their time and owed a great deal of their prosperity to trade. The Phoenicians' initial trading partners were the ], with whom they used to trade wood, slaves, glass and a Tyrian Purple powder. This powder was used by the Greek elite to color clothes and other garments and was not available anywhere else. Without trade with the Greeks they would not be known as Phoenicians, as the word for Phoenician is derived from the ] word ''phoinikèia'' meaning "purple". | |||

| ===Persian period (539–332 BC)=== | |||

| In the centuries following 1200 BC, the Phoenicians formed the major naval and trading power of the region. Phoenician trade was founded on ], a violet-purple dye derived from the '']'' sea-snail's shell, once profusely available in coastal waters of the eastern Mediterranean Sea but exploited to local extinction. ]'s excavations at ] in present day Lebanon revealed crushed Murex shells and pottery containers stained with the dye that was being produced at the site. The Phoenicians established a second production center for the purple dye in ], in present day ]. Brilliant textiles were a part of Phoenician wealth, and Phoenician ] was another export ware. It is also widely accepted{{Who|May 2009|date=May 2009}} that the Phoenicians were very important in the establishment of many ancient dog breeds through the Mediterranean basin. They traded unrefined, prick-eared hunting dogs of Asian or African origin which locally developed into many breeds such as the ]]]]]] and ] | |||

| {{Main|Achaemenid Phoenicia}} | |||

| ]s for ] during the ] in 480 BC (1915 drawing by A. C. Weatherstone).]] | |||

| In 539 BC, ], king and founder of the Persian ], took Babylon.<ref name="Katzenstein-1979">{{cite journal|last=Katzenstein|first=Jacob|title=Tyre in the Early Persian Period (539-486 B.C.E.)|journal=The Biblical Archaeologist|volume=42|issue=1|year=1979|page=31|doi=10.2307/3209545|jstor=3209545|s2cid=165757132|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3209545}}</ref> As Cyrus began consolidating territories across the Near East, the Phoenicians apparently made the pragmatic calculation of " themselves to the Persians".<ref></ref> Most of the Levant was consolidated by Cyrus into a single ]y (province) and forced to pay a yearly tribute of 350 ], which was roughly half the tribute that was required of Egypt and Libya.<ref></ref> | |||

| From elsewhere they obtained other materials, perhaps the most important being ] from ] and ] from ], the latter of which when smelted with ] (from ]) created the durable metal ] ]. ] states that there was a highly lucrative Phoenician trade with Britain for tin. | |||

| The Phoenician area was later divided into four vassal kingdoms—Sidon, Tyre, Arwad, and Byblos—which were allowed considerable autonomy. Unlike in other areas of the empire, there is no record of Persian administrators governing the Phoenician city-states. Local Phoenician kings were allowed to remain in power and given the same rights as Persian satraps (governors), such as hereditary offices and minting their coins.<ref name="Katzenstein-1979" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://brewminate.com/a-history-of-phoenician-civilization/|title=A History of Phoenician Civilization|last=MAMcIntosh|date=2018-08-29|website=Brewminate|language=en-US|access-date=2020-04-20}}</ref> | |||

| The Phoenicians established commercial outposts throughout the ], the most strategically important being ] in ], directly across the narrow straits in below). However, ancient Gaelic mythologies of origin attribute a Phoenician/Scythian influx to Ireland by a leader called ]. Others also sailed south along the coast of ]. A Carthaginian expedition led by ] explored and colonized the Atlantic coast of Africa as far as the ]; and according to Herodotus, a Phoenician expedition sent down the ] by pharaoh ] of Egypt (c. 600 BC) even ] Africa and returned through the ] in three years. | |||

| ]-era coin of ] of Sidon, who is seen at the back of the chariot, behind the Persian King]] | |||

| ==Important cities and colonies== | |||

| The Phoenicians remained a core asset to the Achaemenid Empire, particularly for their prowess in maritime technology and navigation;<ref name="Katzenstein-1979" /> they furnished the bulk of the Persian fleet during the ] of the late fifth century BC.<ref></ref> Phoenicians under ] built the ] and the pontoon bridges that allowed his forces to cross into mainland Greece.<ref></ref> Nevertheless, they were harshly punished by the Persian King following his defeat at the ], which he blamed on Phoenician cowardice and incompetence.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{Prose|date=April 2009}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In the mid-fourth century BC, King ] of Sidon led a failed rebellion against ], enlisting the help of the Egyptians, who were subsequently drawn into a war with the Persians.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/16C*.html|title=LacusCurtius • Diodorus Siculus — Book XVI Chapters 40‑65|website=penelope.uchicago.edu|access-date=2020-04-20}}</ref> The resulting destruction of Sidon led to the resurgence of Tyre, which remained the dominant Phoenician city for two decades until the arrival of Alexander the Great. | |||

| From the ], their expansive culture established cities and colonies throughout the Mediterranean. Canaanite deities like ] and ] were being worshipped from Cyprus to Sardinia, Malta, Sicily, Spain, Portugal, and most notably at Carthage in modern Tunisia. | |||

| ===Hellenistic period (332–152 BC)=== | |||

| In the Phoenician homeland: | |||

| Phoenicia was one of the first areas to be conquered by ] during his ]. Alexander's main target in the Persian Levant was Tyre, now the region's largest and most important city. It capitulated after a roughly ], during which some of its non-combatant citizens were sent to Carthage.{{sfn|Millar|2006|p=58}} Tyre's refusal to allow Alexander to visit its temple to ], culminating in the killing of his envoys, led to a brutal reprisal: 2,000 of its leading citizens were ] and a puppet ruler was installed. The rest of Phoenicia easily came under his control, with Sidon surrendering peacefully.<ref name="Stockwell-2010" /> | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (Classical Aradus) | |||

| * ] (''Greek'' Βηρυτός; ''Latin'' Berytus;<br>''Arabic'' بيروت; ''English'' ]) | |||

| * Botrys (modern ]) | |||

| * Gebal (''Greek'' ]) | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (modern Sarafand) | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (]) | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| ]'s ] (332 BC). Drawing by ], 1888–89.]] | |||

| Phoenician colonies, including some of lesser importance (this list might be incomplete): | |||

| Alexander's empire had a ] policy, whereby Hellenic culture, religion, and sometimes language were spread or imposed across conquered peoples. However, Hellenisation was not enforced most of the time and was just a language of administration until his death. This was typically implemented in other lands through the founding of new cities, the settlement of a Macedonian or Greek urban elite, and the alteration of native place names to Greek. However, there was no organized Hellenization in Phoenicia, and with one or two minor exceptions, all Phoenician city-states retained their native names, while Greek settlement and administration appear to have been very limited.{{sfn|Millar|2006|p=66}} | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** ] (modern ]) | |||

| ** Malaca (modern ]) | |||

| ** Igigili (modern ]) | |||

| ** ] (modern ]) | |||

| ** Ikosium (modern ]) | |||

| ** Iol (modern ]) | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** Kition (modern ]) | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** Mainland | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** Karalis (modern ]) | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** ]<ref>Claudian, B. Gild. 518</ref> | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** Ziz, Classical Lilybeaum (modern ]) | |||

| *** ] | |||

| *** Solus (modern Solunto) | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** Oea (modern ]) | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *The ] islands of Malat (modern ]) | |||

| **Maleth (modern ])<ref>http://www.edrichton.com/MdinaHistory.htm ''History of Mdina''</ref> | |||

| **]<ref>J.G. Baldacchino & T.J. Dunbabin, “Rock tomb at Għajn Qajjet, near Rabat, Malta”, Papers of the British School at Rome, 21 (1953) 32-41.</ref> | |||

| **]<ref name= "History">http://members.ziggo.nl/bezver/romans.html ''A History of Malta''</ref> | |||

| **]<ref>Annual Report on the Working of the Museum Department 1926-27, Malta 1927, 8; W. Culican, “The repertoire of Phoenician pottery”, Phönizier im Westen, Mainz 1982, 45-82.</ref> | |||

| **]<ref>Annual Report on the Working of the Museum Department 1916-7, Malta 1917, 9-10.</ref> | |||

| **] in ]<ref name= "History"/> | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ]<ref>C. Michael Hogan, ''Mogador: promontory fort'', The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham, Nov. 2, 2007 </ref> | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** Gytta | |||

| ** ] (modern ]) | |||

| ** Tingis (modern ]) | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** ] (modern ]) | |||

| ** Abyla (modern ]) | |||

| ** Akra Leuke (modern ]) | |||

| ** Gadir (modern ]) | |||

| ** Ibossim (modern ]) | |||

| ** Malaca (modern ]) | |||

| ** Onoba (modern ]) | |||

| ** ] (''Greek'' Νέα Καρχηδόνα; ''Latin'' Carthago Nova; ''Spanish'' ]) | |||

| ** Rusadir (modern ]) | |||

| ** ] (modern ]) | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** Olissipona (modern ]) | |||

| ** Ossonoba (modern ]) | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** ] (modern ]) | |||

| ** Hippo Diarrhytos (modern ]) | |||

| ** ] (''Greek'' Καρχηδόνα; ''Latin'' Carthago; ''English'' ]) | |||

| ** ] (near modern ]) | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * Located in modern ] | |||

| ** Phoenicus (modern ]) | |||

| * Other colonies | |||

| ** ] (modern ]) | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| The Phoenicians maintained cultural and commercial links with their western counterparts. ] recounts how the Seleucid King ] escaped from Rome by boarding a Carthaginian ship that was delivering goods to Tyre.{{sfn|Millar|2006|p=58}} The adaptation to Macedonian rule was probably aided by the Phoenicians' historical ties with the Greeks, with whom they shared some mythological stories and figures; the two peoples were even sometimes considered "relatives". | |||

| ==Culture== | |||

| ===Language and literature=== | |||

| {{main|Phoenician languages|Phoenician alphabet|Alphabet}} | |||

| When Alexander's empire collapsed after his death in 323 BC, the Phoenicians came under the control of the largest of its successors, the ]. The Phoenician homeland was repeatedly contested by the ] of Egypt during the forty-year ], coming under Ptolemaic rule in the third century BC. The Seleucids reclaimed the area the following century, holding it until the mid-first 2nd century BC. Under their rule, the Phoenicians were allowed a considerable degree of autonomy and self-governance. | |||

| The Phoenicians are credited with spreading the ] throughout the Mediterranean world.<ref>{{cite book | last = Beck | first = Roger B. | authorlink = | coauthors = Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, Dahia Ibo Shabaka, | title = World History: Patterns of Interaction | publisher = McDougal Littell | date = 1999 | location = Evanston, IL | pages = | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 0-395-87274-X }}</ref> It was a variant of the Semitic alphabet of the Canaanite area developed centuries earlier in the Sinai region, or in central Egypt. Phoenician traders disseminated this writing system along Aegean trade routes, to coastal Anatolia, the Minoan civilization of Crete, ], and throughout the Mediterranean. | |||

| During the ] (157–63 BC), the Phoenician cities were mainly self-governed. Many of them were fought for or over by the warring factions of the Seleucid royal family. Some Phoenician regions were under Jewish influence, after the Jews revolted and succeeded in defeating the Seleucids in 164 BC. A significant portion of the Phoenician diaspora in North Africa thus converted to Judaism in the late millennium BC.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Feldman |first1=Louis H. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pACJYw0bg3QC&pg=PA195 |title=Studies in Hellenistic Judaism |date=1996 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-10418-1 |language=en}}</ref><ref>Rives, 1995 p.220</ref><ref name="Selzer1984">{{cite book |last1=Selzer |first1=Claudia |title=The Cambridge History of Judaism: The late Roman-Rabbinic period |year=1984 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-77248-8 |editor1-last=Davies |editor1-first=William David |page=69 |language=en |chapter=The Jews in Carthage and Western North Africa, 66-235 CE |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BjtWLZhhMoYC&pg=PA68}}</ref> The Seleucid Kingdom was seized by ] of ] in 74/73 BC, ending the Hellenistic influence on the Levant.{{sfn|Wright|2011|p=128}}{{sfn|Hoover|2007|p=298}} | |||

| This alphabet has been termed an '']'' or a script that contains no vowels. A ] ''abjad'' originated to the north in ], a Canaanite city of northern Syria, in the ]. Their language, ], is classified as in the ] subgroup of Northwest ]. Its later descendant in ] is termed ]. | |||

| ==Demographics== | |||

| ] (''The Louvre'')]] | |||

| The people now known as Phoenicians were a group of ] that emerged in the ] in at least the third millennium BC.<ref name="Scott-2018" /> Phoenicians did not refer themselves as "Phoenicians" but rather are thought to have broadly referred to themselves as "Kenaʿani", meaning ']'. Phoenicians identified themselves specifically with the name of the city they hailed from (e.g., ''Sidonian'' for ], ''Tyrian'' for ], etc.). | |||

| The earliest known inscriptions in Phoenician come from Byblos and date back to ca. 1000 BC. Phoenician inscriptions are found in Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Cyprus and other locations, as late as the early centuries of the Christian Era. In Phoenician colonies around the western Mediterranean, beginning in the ], Phoenician evolved into Punic. Punic Phoenician was still spoken in the 5th century CE: ], for example, grew up in ] and was familiar with the language. | |||

| === |

===Genetic studies=== | ||

| ] of Sidon (reigned c. 549 BC – c. 539 BC), now in the ]]] | |||

| Phoenician art had no unique characteristic that could be identified with. This is due to the fact that Phoenicians were influenced by foreign designs and artistic cultures mainly from ], ] and ]. Phoenicians who were taught on the banks of the ] and the ] gained a wide artistic experience and finally came to create their own art, which was an amalgam of foreign models and perspectives.<ref name="NYT">{{cite web|url=http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9800E4DF123EE73BBC4D53DFB7668382669FDE&oref=slogin|title=Phoenician Art|format=.pdf|work = The New York Times |accessdate=2008-06-20}}</ref> In an article from ], published on January 5, 1879, Phoenician art was described by the following: <blockquote>He entered into other men's labors and made most of his heritage. The ] of Egypt became ], and its new form was transplanted to ] on the one side and to Greece on the other. The rosettes and other patterns of the ] cylinders were introduced into the handiwork of Phoenicia, and so passed on to the West, while the hero of the ancient ] epic became first the ] ]h, and then the ] of Hellas.</blockquote> | |||

| {{See also||Canaan#Genetic studies|Lebanese people#Genetics}} | |||

| A 2008 study led by ] found that six subclades of ] (J2)—thought to have originated between the ], ] and the ]—were of a "Phoenician signature" and present amongst the male populations of coastal Lebanon as well as the wider Levant (the "Phoenician Periphery"), followed by other areas of historic Phoenician settlement, spanning Cyprus through to Morocco. This deliberate sequential sampling was an attempt to develop a methodology to link the documented historical expansion of a population with a particular geographic genetic pattern or patterns. The researchers suggested that the proposed genetic signature stemmed from "a common source of related lineages rooted in ]".<ref name="Zalloua 2008">{{cite journal |last=Zalloua |first=Pierre A.|author-link=Pierre Zalloua |title=Identifying Genetic Traces of Historical Expansions: Phoenician Footprints in the Mediterranean |journal=] |year=2008 |volume=83 |issue=5 |pages=633–642 |doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.012 |pmid=18976729 |pmc=2668035|display-authors=et al.}}</ref> Another study in 2006 found evidence for the genetic persistence of Phoenicians in the Spanish island of ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tomàs |first1=Carme|title=Differential maternal and paternal contributions to the genetic pool of Ibiza Island, Balearic Archipelago |journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology |date=2006 |volume=129 |issue=2 |pages=268–278 |doi=10.1002/ajpa.20273 |pmid=16323196 }}</ref> | |||

| In 2016, the rare ] maternal haplogroup was identified in the DNA of a 2,500-year-old male skeleton excavated from a Punic tomb in Tunisia. The lineage of this "Young Man of Byrsa" is believed to represent early gene flow from ] to the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Matisoo-Smith |first1=Elizabeth A. |last2=Gosling |first2=Anna L. |last3=Boocock |first3=James |last4=Kardailsky |first4=Olga |last5=Kurumilian |first5=Yara |last6=Roudesli-Chebbi |first6=Sihem |date=25 May 2016 |title=A European Mitochondrial Haplotype Identified in Ancient Phoenician Remains from Carthage, North Africa |journal=] |volume=11 |issue=5 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0155046 |display-authors=et al. |pages=e0155046 |pmid=27224451 |pmc=4880306|bibcode=2016PLoSO..1155046M |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Gods=== | |||

| {{Prose|date=April 2009}} | |||

| {{see|Canaanite religion}} | |||

| According to a 2017 study published by the ], present-day Lebanese derive most of their ancestry from a ]ite-related population, which therefore implies substantial genetic continuity in the Levant since at least the ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Harb|first1=Marc|display-authors=etal|date=July 2017|title=Continuity and Admixture in the Last Five Millennia of Levantine History from Ancient Canaanite and Present-Day Lebanese Genome Sequences|url=|journal=American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=101|issue=2|pages=274–282|doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.013|pmc=5544389|pmid=28757201}}</ref><ref name=latimes/> More specifically, the research of geneticist Chris Tyler-Smith and his team at the ] in Britain, who compared "sampled ancient DNA from five ] who lived 3,750 and 3,650 years ago" to modern people, revealed that 93 percent of the genetic ancestry of people in Lebanon came from the ] (the other 7 percent was of a ] population).<ref name=latimes>{{cite web |url=https://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-canaanite-lebanese-genetics-20170727-story.html |title=The DNA of ancient Canaanites lives on in modern-day Lebanese, genetic analysis shows |last=Abed |first=Mira |work=Los Angeles Times |date=27 July 2017 |access-date=5 August 2021 |url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210809223800/https://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-canaanite-lebanese-genetics-20170727-story.html|archive-date=Aug 9, 2021}}</ref> | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| ====Attested 2nd Millennium==== | |||

| *] | |||

| *Amen (]) | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] "Lady of Byblos" | |||

| *] consort of Baalat Gebal | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *Venerable ] (Reshef of the Arrow) | |||

| Gebory-Kon | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| One 2018 study of mitochondrial lineages in Sardinia concluded that the Phoenicians were "inclusive, multicultural and featured significant female mobility", with evidence of indigenous ] integrating "peacefully and permanently" with Semitic Phoenician settlers. The study also found evidence suggesting that south Europeans may have likewise settled in the area of modern Lebanon.<ref>{{Cite web |date=10 January 2018 |title=Ancient Phoenician life was mixed and multicultural |url=https://cosmosmagazine.com/biology/ancient-phoenician-life-was-mixed-and-multicultural |access-date=2020-04-25 |website=Cosmos Magazine |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ====Attested 1st Millennium==== | |||

| *Chusor | |||

| *Dagon | |||

| *Eshmun-Melqart | |||

| *Milkashtart | |||

| *Reshef-Shed | |||

| *Shed-Horon | |||

| *Tanit-Astarte | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| In a 2020 study published in the ], researchers have shown that there is substantial genetic continuity in Lebanon since the ] interrupted by three significant admixture events during the ], ], and ] period. In particular, the Phoenicians can be modeled as a mixture of the local Bronze Age population (63–88%) and a population coming from the North, related to ancient ]ns or ancient ] (12–37%). The results show that a ], typically found in Europeans, appears in the region starting from the Iron Age.<ref name="doi_10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.05.008">{{cite journal|last1=Haber|first1=Marc|last2=Nassar|first2=Joyce|last3=Almarri|first3=Mohamed A.|last4=Saupe|first4=Tina|last5=Saag|first5=Lehti|last6=Griffith|first6=Samuel J.|last7=Doumet-Serhal|first7=Claude|last8=Chanteau|first8=Julien|last9=Saghieh-Beydoun|first9=Muntaha|last10=Xue|first10=Yali|last11=Scheib|first11=Christiana L.|year=2020|title=A Genetic History of the Near East from an aDNA Time Course Sampling Eight Points in the Past 4,000 Years|journal=American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=107|issue=1|pages=149–157|doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.05.008|pmc=7332655|pmid=32470374|last12=Tyler-Smith|first12=Chris}}</ref> | |||

| ==Influence in the Mediterranean region== | |||

| ] from ], ca. 560–550 BC, ]]] | |||

| Phoenician culture had a huge effect upon the cultures of the Mediterranean basin in the early Iron Age, and had also been affected in reverse. For example, in Phoenicia, the tripartite division between ], ] and ] seems to have been influenced by the Greek division between ], ] and ]. Phoenician temples in various Mediterranean ports sacred to Phoenician ], during the classical period, were recognized as sacred to ]. Stories like the ], and the coming of ] also draw upon Phoenician influence. | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| The recovery of the Mediterranean economy after the late ], seems to have been largely due to the work of Phoenician traders and merchant princes, who re-established long distance trade between Egypt and Mesopotamia in the 10th century BC. The Ionian revolution was, at least in legend, led by ] such as ] or ], both of whom had Phoenician fathers. Phoenician motifs are also present in the ] of ], and Phoenicians also played a formative role in ] in Tuscany. | |||

| ===Trade=== | |||

| There are many countries and cities around the world that derive their names from the Phoenician Language. Below is a list with the respective meanings: | |||

| {{See also|Phoenicians and wine}} | |||

| * ]: City in Algeria, SW of Carthage. From Phoenician: "Iltabrush" | |||

| ] | |||

| * ]: City in Sardinia: From Phoenician "Bis'en" | |||

| The Phoenicians served as intermediaries between the disparate civilizations that spanned the Mediterranean and Near East, facilitating the exchange of goods and knowledge, culture, and religious traditions. Their expansive and enduring trade network is credited with laying the foundations of an economically and culturally cohesive Mediterranean, which would be continued by the Greeks and especially the Romans.<ref name="Bentley-1999" /> | |||

| * ]: City in Spain: From Phoenician "Gadir" | |||

| * ] (Idalion): City in Central Cyprus: From Phoenician "Idyal" | |||

| * ]: City in Sicily: From Phoenician "Eryx" | |||

| * ]: Island in the Mediterranean: From Phoenician "Malat" ('refuge') | |||

| * ]: City in West Cyprus: From Phoenician "Aymar" | |||

| * ]: City in Algeria: From Phoenician: "Idiqra" | |||

| * Spain: From Phoenician: "I-Shaphan", meaning "Land of Hyraxes". Later Latinized as "]" | |||

| ] | |||

| ==In the Bible== | |||

| Phoenician ties with the Greeks ran deep. The earliest verified relationship appears to have begun with the ] on Crete (1950–1450 BC), which together with the ] (1600–1100 BC) is considered the progenitor of classical Greece.<ref>{{cite book|first=Fernand|last=Braudel|title=Memory and Mediterranean|translator-first=Sian|translator-last=Reynolds|location=New York|publisher=Alfred A. Knopf|year=2001|pages=112–113}}</ref> Archaeological research suggests that the Minoans gradually imported Near Eastern goods, artistic styles, and customs from other cultures via the Phoenicians. | |||

| Hiram (also spelled Huran) associated with the building of the temple. | |||

| To Egypt the Phoenicians sold logs of cedar for significant sums,{{sfn|Cunliffe|2008|pp=241–242}} and ] beginning in the eighth century. The wine trade with Egypt is vividly documented by shipwrecks discovered in 1997 in the open sea {{convert|50|km|-1}} west of ], Israel.<ref>{{cite book |first=L. E. |last=Stager |chapter=Phoenician shipwrecks in the deep sea |title=Sea routes: From Sidon to Huelva: Interconnections in the Mediterranean, 16th–6th c. BC |year=2003 |pages=233–248 |publisher=Museum of Cycladic Art |isbn=978-960-7064-40-0 }}</ref> Pottery kilns at ] and ] produced the large terracotta jars used for transporting wine. From Egypt, the Phoenicians bought ]n gold. | |||

| {{cquote|2 Chronicles 2:13—The son of a woman of the daughters of Dan, and his father a man of Tyre, skillful to work in gold, silver, brass, iron, stone, timber, royal purple(from the Murex), blue, and in crimson, and fine linens; also to grave any manner of graving, and to find out every device which shall be put to him...}} | |||

| ] found in Cádiz, Spain, thought to have been imported from the Phoenician homeland around Sidon.<ref>A. B. Freijeiro, R. Corzo Sánchez, Der neue anthropoide Sarkophag von Cadiz. In: Madrider Mitteilungen 22, 1981.</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lapuente |first1=P. |last2=Rodà |first2=I. |last3=Gutiérrez Garcia-M |first3=A. |last4=Brilli |first4=M. |title=Addressing the controversial origin of the marble source used in the Phoenician anthropoid sarcophagi of Gadir (Cadiz, Spain) |journal=Archaeometry |date=June 2021 |volume=63 |issue=3 |pages=467–480 |doi=10.1111/arcm.12623|s2cid=225150177 |url=http://zaguan.unizar.es/record/108415 }}</ref> Archaeological Museum of Cádiz.]] | |||

| This is the architect of the Temple, ] of ] lore. They are vastly famous for their purple dye. | |||

| From elsewhere, they obtained other materials, perhaps the most crucial being ], mostly from ] and the ]. Tin for making ] "may have been acquired from ] by way of the Atlantic coast of southern Spain; alternatively, it may have come from northern Europe (] or ]) via the ] and coastal ]".{{sfn|Markoe|2000|p=103}} ] states that there was a highly lucrative Phoenician trade with Britain for tin via the ], whose location is unknown but may have been off the northwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Hawkes|first=Christopher|title=Britain and Julius Caesar|journal=Proceedings of the British Academy|issue=63|year=1977|pages=124–192}}</ref> | |||

| Later, reforming prophets railed against the practice of drawing royal wives from among foreigners: ] execrated ], the princess from Tyre who became a consort of King ] and introduced the ]. | |||

| ===Industry=== | |||

| Long after Phoenician culture had flourished, or Phoenicia had existed as any political entity, Hellenized natives of the region where Canaanites still lived were referred to as "Syro-Phoenician", as in the '']'' 7:26: "The woman was a Greek, a Syrophoenician by birth..." | |||

| ] with hunting scene (8th century BC). The clothing and hairstyle of the figures are Egyptian. At the same time, the subject matter of the central scene conforms with the ]n theme of combat between man and beast. Phoenician artisans frequently adapted the styles of neighboring cultures.]] | |||

| Phoenicia lacked considerable natural resources other than its ] wood. Timber was probably the earliest and most lucrative source of wealth; neither Egypt nor Mesopotamia had adequate wood sources. Unable to rely solely on this limited resource, the Phoenicians developed an industrial base manufacturing a variety of goods for both everyday and luxury use.<ref name="Scott-2018" /> The Phoenicians developed or mastered techniques such as ], engraved and ] metalwork (including bronze, iron, and gold), ivory carving, and woodwork.<ref name="Markoe-1990b" /> | |||

| The Phoenicians were early pioneers in mass production, and sold a variety of items in bulk. They set up trade networks to market their glassware and became its leading source in antiquity, shipping flasks, beads, and other glass objects across the Mediterranean in their vessels.{{sfn|Herm|1975|p=80}} Excavations of colonies in Spain suggest they also used the ].<ref>{{cite book|first1=Karl|last1=Moore|first2=David|last2=Lewis|title=Birth of the Multinational|location=Copenhagen|publisher=Copenhagen Business School Press|year=1999|page=85}}</ref> Their exposure to a wide variety of cultures allowed them to manufacture goods for specific markets.<ref name="Markoe-1990b">{{cite journal|last1=Markoe|first1=Glenn|last2= McGovern|first2=Patrick E.|title=A Nation of Artisans|journal=Archaeology|volume=43|issue=2|date=March 1990|pages=32–33|jstor=41765806|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41765806}}</ref> The ''Iliad'' suggests Phoenician clothing and metal goods were highly prized by the Greeks.<ref name="Scott-2018" /> Specialized goods were designed specifically for wealthier clientele, including ivory reliefs and plaques, carved ] shells, sculpted amber, and finely detailed and painted ostrich eggs. | |||

| The word '']'' itself ultimately derives through Greek from the word ] which means ], and not from the Hellenised Phoenician city of Byblos (which was called Gebal), before it was named by the Greeks as ]. The Greeks called it Byblos because it was through Gebal that bublos (Bύβλος ) was imported into Greece. Present day Byblos is under the current Arabic name of Jbeil (جبيل Ǧubayl) derived from Gebal. | |||

| ====Tyrian purple==== | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| ] tomb ({{circa|350}} BC) depicting a man wearing an all-purple '']'']] | |||

| The name ''Phoenician'', through ] ''punicus'', comes from ] ''phoînix'', often suggested as "], crimson; ]" (from ''phoinos'' "blood red"<ref>Gove, Philip Babcock, ed. ''Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged''. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 1993.</ref>). The Phoenician's nickname "Purple People" came from the purple dye they manufactured for royalty in Mesopotamia and ]. | |||

| The most prized Phoenician goods were fabrics dyed with ], which formed a major part of Phoenician wealth. The violet-purple dye derived from the ] of the '']'' marine snail, once profusely available in coastal waters of the eastern Mediterranean Sea but now exploited to local extinction. Phoenicians may have discovered the dye as early as 1750 BC.<ref>{{cite book|last=St. Clair|first=Kassia|year=2016|title=The Secret Lives of Colour|location=London|publisher=John Murray|pages=162–164}}</ref> The Phoenicians established a second production center for the dye in ], in present-day ].<ref>{{cite book|title=The Phoenicians: A Captivating Guide to the History of Phoenicia and the Impact Made by One of the Greatest Trading Civilizations of the Ancient World|year=2019|isbn=978-1647482053|page=60|last1= History|first1= Captivating|publisher=Captivating History }}</ref> | |||

| The Phoenicians' exclusive command over the production and trade of the dye, combined with the labor-intensive extraction process, made it very expensive. Tyrian purple subsequently became associated with the upper classes. It soon became a ] in several civilizations, most notably among the Romans. Assyrian tribute records from the Phoenicians include "garments of brightly colored stuff" that most likely included Tyrian purple. While the designs, ornamentation, and embroidery used in Phoenician textiles were well-regarded, the techniques and specific descriptions are unknown.<ref name="Markoe-1990b" /> | |||

| ==''Hippoi''== | |||

| The Greeks had two names for Phoenician ships: ''hippoi'' and ''galloi''. Galloi means tubs and hippoi means horses. These names are readily explained by depictions of Phoenician ships in the palaces of Assyrian kings from the 7th and 8th centuries, as the ships in these images are tub shaped (galloi) and have horse heads on the ends of them (hippoi.) It is possible that these hippoi come from Phoenician connections with the Greek god Poseidon. | |||

| ===Depictions=== | |||

| ====Shalmaneser, Tel Balawat Gates, 850 BCE==== | |||

| ====Mining==== | |||

| These gates are found in the palace of Shalamaneser,an Assyrian king, near Nimrud. They are made of bronze, and they portray ships coming to honor Shalamaneser <ref>Markoe, G. E. 2000. Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians. Los Angeles: University of California Press </ref>. To see the ships on the Tel Balawat Gates, go to http://www.qsov.com/UK2006/718BM.JPG | |||

| Mining operations in the Phoenician homeland were limited; iron was the only metal of any worth. The first large-scale mining operations by Phoenicians probably occurred in Cyprus, principally for copper. Sardinia may have been colonized almost exclusively for its mineral resources; Phoenician settlements were concentrated in the southern parts of the island, close to sources of copper and lead. Piles of ] and copper ingots, which appear to predate Roman occupation, suggest the Phoenicians mined and processed metals on the island. The Iberian Peninsula was the richest source of numerous metals in antiquity, including gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, and lead.{{sfn|Rawlinson|1889|p=313}} The output of silver during the Phoenician and Carthaginian occupation there was enormous.{{sfn|Rawlinson|1889|p=314}} The Carthaginians relied on slave labor almost exclusively in their mining operations, and according to Rawlinson, because they likely continued the established practices of their predecessors in Iberia, the Phoenicians themselves probably also used slave labor.{{sfn|Rawlinson|1889|pp=317–318}} | |||

| ====Viticulture==== | |||

| ====Sargon II, Khorsabad, 7th Century BCE==== | |||