| Revision as of 07:44, 15 December 2005 edit4.225.172.140 (talk) →Way to Northern Expedition and death← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:31, 17 January 2025 edit undoGuardianH (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users59,659 edits →Names: ceTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Chinese revolutionary and statesman, founder of the Republic of China and Kuomintang (1866–1925)}} | |||

| {| cellpadding=3px cellspacing=0px bgcolor=#f7f8ff style="float:right; border:1px solid; margin:5px" | |||

| {{redirect|Sun Wen|the female footballer|Sun Wen (footballer)}} | |||

| |colspan=2 align=center style="border-top:1px solid"|] | |||

| {{Family name hatnote|]|lang=Chinese}} | |||

| |- | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2024}} | |||

| !style="background:#ccf; border-bottom:1px solid" colspan=2|] (]) | |||

| {{Infobox officeholder | |||

| |- | |||

| | |

| name = Sun Yat-sen | ||

| | native_name = {{nobold|孫逸仙}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | native_name_lang = zh | |||

| |align=right|]:||孫逸仙 | |||

| | image = 孙中山肖像.jpg | |||

| |- | |||

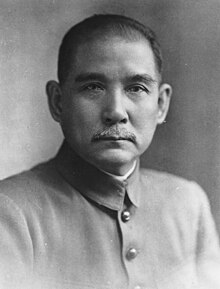

| | caption = Sun in 1922 | |||

| |align=right|]:||Sūn Yìxiān | |||

| | office = 1st ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | term_start = 1 January 1912 | |||

| |align=right|]:||Sun I-hsien | |||

| | term_end = 10 March 1912 | |||

| |- | |||

| | vicepresident = ] | |||

| |align=right style="border-top:1px solid"|Known to Chinese as:||style="border-top:1px solid"|孫中山 | |||

| | predecessor = ''Office established'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| |align=right|]:||Sūn Zhōngshān | |||

| | office2 = ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | predecessor2 = ''Office established'' | |||

| |align=right|]:||Sun Chung-shan | |||

| | successor2 = ] (as Chairman) | |||

| |- | |||

| | term_start2 = 10 October 1919 | |||

| |align=right style="border-top:1px solid"|Family name:||style="border-top:1px solid"|Sun | |||

| | term_end2 = 12 March 1925 | |||

| |- | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|df=y|1866|11|12}} | |||

| |align=right|]:||孫 | |||

| | birth_place = ], Guangdong, ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | birth_name = Sun Te-ming ({{lang|zh|孫德明}}) | |||

| |align=right|]:||孙 | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|df=y|1925|3|12|1866|11|12}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| |align=right style="border-top:1px solid"|Given||style="border-top:1px solid"|names | |||

| | resting_place = ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | party = ] | |||

| |align=right|Register name :||Deming (德明) | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{marriage|]|1885|1915|end=div}} | |||

| |align=right|Milk name :||Dixiang (帝象) | |||

| * {{marriage|]|1905|1906|end={{abbr|a.|abandoned}}}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{marriage|]|25 October 1915}} | |||

| |align=right|School name :||Wen (文) | |||

| * ] (], 1892–1925) | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] (concubine, 1897–1902) | |||

| |align=right|] :||Zaizhi (載之) | |||

| }} | |||

| |- | |||

| | children = 4, including ] | |||

| |align=right|] :||Rixin (日新), later | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | father = Sun Da-cheng ({{lang|zh|孫達成}}) | |||

| |align=right| ||Yixian (逸仙), | |||

| | signature = Signature of Sun Yat Sen - China Document 21 Jan 1912 - dark version.svg | |||

| |- | |||

| | blank1 = Signature (Chinese) | |||

| |align=right| ||pronounced similarly<br>in ] (Yat <br>San, Yat Sin, resp.) | |||

| | data1 = ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | branch = ] | |||

| |align=right|Alias :||Zhongshan (中山) | |||

| | serviceyears = 1917–1925 | |||

| |- | |||

| | rank = '']'' | |||

| |align=right style="border-top:1px solid"|Styled:||style="border-top:1px solid"|Guofu (國父), i.e. | |||

| | battles = * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] | |||

| |align=right valign=top| ||"Father of the Nation" | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] | |||

| |} | |||

| * ] | |||

| | module = {{Listen|pos=center|embed=yes|filename=民國13年 國父孫中山先生於廣州演講.oga|title=Sun Yat-sen's voice|type=speech|description=On the Three Principles of the People<br />Recorded in Guangzhou on 30 May 1924}} | |||

| | module2 = {{Infobox Chinese|child=yes|showflag=pj | |||

| | name1 = Common name in English | |||

| | t = 孫逸仙 | |||

| | s = 孙逸仙 | |||

| | p = Sūn Yìxiān | |||

| | tp = Sun Yì-sian | |||

| | hk = Suen Yat-sin | |||

| | w = {{tonesup|Sun1 Yi4-hsien1}} | |||

| | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|s|un|1|-|yi|4|.|x|ian|1}} | |||

| | bpmf = {{bpmfsp|ㄙㄨㄣ|ㄧˋ|ㄒㄧㄢ}} | |||

| | j = Syun1 Jat6-sin1 | |||

| | ci = {{IPAc-yue|s|yun|1|-|j|at|6|-|s|in|1}} | |||

| | y = Syūn Yaht-sīn | |||

| | poj = Sun E̍k-sian | |||

| | altname = Common name in Chinese | |||

| | s2 = 孙中山 | |||

| | t2 = 孫中山 | |||

| | p2 = Sūn Zhōngshān | |||

| | tp2 = Sun Jhong-shan | |||

| | w2 = {{tonesup|Sun1 Chung1-shan1}} | |||

| | mi2 = {{IPAc-cmn|s|un|1|-|zh|ong|1|.|sh|an|1}} | |||

| | bpmf2 = ㄙㄨㄣ ㄓㄨㄥ ㄕㄢ | |||

| | j2 = Syun1 Zung1-saan1 | |||

| | y2 = Syūn Jūng sāan | |||

| | ci2 = {{IPAc-yue|s|yun|1|-|z|ung|1|-|s|aan|1}} | |||

| | poj2 = Sun Tiong-san | |||

| | altname3 = ] | |||

| | t3 = 孫載之 | |||

| | s3 = 孙载之 | |||

| | p3 = Sūn Zàizhī | |||

| | tp3 = Sun Zài-jhih | |||

| | w3 = {{tonesup|Sun1 Tsai4-chih1}} | |||

| | mi3 = {{IPAc-cmn|s|un|1|-|z|ai|4|.|zhi|1}} | |||

| | bpmf3 = {{bpmfsp|ㄙㄨㄣ|ㄗㄞˋ|ㄓ}} | |||

| | j3 = Syun1 Zoi3-zi1 | |||

| | ci3 = {{IPAc-yue|s|yun|1|-|z|oi|3|-|z|i|1}} | |||

| | y3 = Syūn Joi-jī | |||

| }} | |||

| | education = {{avoid wrap|] (])}} | |||

| | honorific_prefix = '']'' 國父<br />Forerunner of the Revolution | |||

| | profession = {{Hlist|Physician|statesman}} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Sun Yat-sen''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|ʊ|n||'|j|ɑː|t|ˈ|s|ɛ|n}};<ref>{{multiref| {{Cite dictionary |year=2020 |title=Sun Yat-sen |dictionary=Collins English Dictionary |url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/sun-yat-sen}} | {{Cite dictionary |year=2023 |title=Sun Yat-sen |dictionary=Dictionary.com |url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/sun-yat-sen}} }}</ref> {{lang-zh|t=孫逸仙|s=孙逸仙|p=Sūn Yìxiān|first=t}}; 12 November 1866{{snd}}12 March 1925){{efn|Usually known as '''Sun Zhongshan''' ({{lang-zh|s=孙中山|t=孫中山|first=t}}) in Chinese; also known by ].}} was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and ] who founded the ] (ROC) and its first political party, the ] (KMT). As the paramount leader of the ], Sun is credited with overthrowing the ] and served as the first president of the ] (1912) and as the inaugural ].<ref name="Tung1" /> | |||

| Born to a peasant family in ], Sun was educated overseas in ] and returned to China to graduate from medical school in ]. He led underground ] revolutionaries in ], the ], and ] as one of the ] and rose to prominence as the founder of multiple ], including the ] and the ]. Although he is considered one of the most important figures of modern China, his political life campaigning against ] reign in favor of a Chinese republic featured constant struggles and frequent periods of exile. | |||

| '''Sun Yat-sen''' (], ] – ], ]) was a ] revolutionary leader who had a significant role in the overthrow of the ]. A founder of the ], Sun was the first provisional ] when the ] was founded in ]. He developed a ] known as the '']'' which still heavily influences ] today. | |||

| After the success of the 1911 Revolution, Sun proclaimed the ] but had to relinquish the presidency to general ], ultimately going into exile in Japan. He later returned to launch a revolutionary government in ] to challenge the ] who controlled much of the country following Yuan's death in 1916. In 1923, Sun invited representatives of the ] to ] to reorganize the KMT and formed the ] with the ] (CCP). He did not live to see his party unify the country under his successor, ], in the ]. While residing in ], Sun died of ] in 1925. | |||

| Sun was a uniting figure in ], and remains unique among ] Chinese politicians for being widely revered in both ] and ]. In Taiwan, he is known by the ] ''National Father, Mr. Sun Chungshan'' (國父 孫中山先生). On the ], Sun is also seen as a Chinese ], and is highly regarded as the ''Forerunner of the Revolution'' (革命先行者). | |||

| Uniquely among 20th-century Chinese leaders, Sun is revered in both Taiwan (where he is officially the "]") and in the ] (where he is officially the "Forerunner of ]") for his instrumental role in ending Qing rule and overseeing the conclusion of the Chinese ]. His political philosophy, known as the ], sought to modernise China by advocating for ], ], and the ] in ] ('']'').<ref>{{Cite book |last=Schoppa |first=R. Keith |title=The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-231-50037-1 |pages=73, 165, 186}}</ref> The philosophy is commemorated as the ], which Sun composed. | |||

| Although Sun is considered one of the greatest leaders of modern China, his life was one of constant struggle and frequent ]. He quickly fell out of power in the newly-founded Republic, and led successive revolutionary governments as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the nation. Ultimately he was not able to bring about consolidation of power over the country, and soon after his death China plunged into ]. | |||

| == |

== Names == | ||

| {{Main|Names of Sun Yat-sen}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]: 1 yuan – Sun Yat Sen, 1927]] | |||

| ===Early years=== | |||

| Sun's {{ill|genealogical name|zh|谱名}} was '''Sun Deming''' (]: {{tlit|yue|Syūn Dāk-mìhng}}; {{lang|zh|孫德明}}).<ref name="singtao1">] daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. {{lang|zh|特別策劃}} section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition {{lang|zh|民國之父}}.</ref><ref name="sunbook2">{{cite book |last1=Wang |first1=Ermin |author-mask=Wang Ermin (王爾敏) |script-title=zh:思想創造時代:孫中山與中華民國 |publisher=Showwe Information |isbn=978-9862217078 |page=274 |year=2011 |language=zh}}</ref> As a child, his ] was Tai Tseung ({{tlit|yue|Dai-jeuhng}}; {{lang|zh|帝象}}).<ref name="singtao1" /> In school, a teacher gave him the name '''Sun Wen''' ({{tlit|yue|Syūn Màhn}}; {{lang|zh|孫文}}), which was used by Sun for most of his life. Sun's ] was Zaizhi ({{tlit|yue|Jai-jī}}; {{lang|zh|載之}}), and his baptized name was Rixin ({{tlit|yue|Yaht-sān}}; {{lang|zh|日新}}).<ref name="Sunbook1">{{cite book |last1=Wang |first1=Shounan |author-mask= Wang Shounan (王壽南) |year=2007 |title=Sun Zhong-san |publisher=] Taiwan |isbn=978-9570521566 |page=23}}</ref> While at school in ], he got the ] Yat-sen ({{zhi|c=逸仙|p=Yìxiān}}).<ref name="book2006">{{cite book |last=You |first=Zixiang |author-mask= You Zixiang (游梓翔) |language=zh |year=2006 |script-title=zh:領袖的聲音: 兩岸領導人政治語藝批評, 1906–2006 |publisher=Wu-nan wenhua |isbn=978-9571142685 |page=82}}</ref> '''Sun Zhongshan''' ({{tlit|yue|Syūn Jūng-sāan}}; {{lang|zh|孫中山}}, also romanized ''Chung Shan''), the most popular of his Chinese names in China, is derived from his ] ''Kikori Nakayama'' ({{Nihongo2|中山樵}}; {{tlit|ja|Nakayama Kikori}}), the pseudonym given to him by ] when he was in hiding in Japan.<ref name="singtao1" /> His birthplace city was renamed ] in his honour likely shortly after his death in 1925. Zhongshan is one of the few ] in China and has remained the official name of the city during Communist rule. | |||

| On ], ], Sun Yat-sen was born to a ] peasant family in the village of ], ] county, ] prefecture, ] province — though it is said he spoke the ] dialect of Cantonese. In ], when Sun Yat-sen died, the name of Xiangshan county was changed into Zhongshan county to honor his memory. Then in ] it was turned into the ] of Zhongshan, and in ] it was elevated and made the ] of Zhongshan, probably again to honor the home region of Sun Yat-sen. The village of Cuiheng is located 20 km (12 miles) southeast of downtown Zhongshan, and only 26 km (16 miles) north of ]. | |||

| == Early years == | |||

| Sun Yat-sen was the fifth out of six children born to ] (孫達成), a farmer by day and a midnight watchman by night, and the woman surnamed Yang. Sun was the fifth of six children. His eldest brother, ] (]: Dezhang 德彰), was born in ]. Sun also had an elder sister, Jinxing (金星) who died at age four, a brother, Deyou (德祐) who died at age six, a sister, Miaoxi (妙茜), and a younger sister, Qiuqi (秋綺). | |||

| === Birthplace and early life === | |||

| Sun Deming was born on 12 November 1866 to Sun Dacheng and ].<ref name="chron-nathall">{{Cite web |title=Chronology of Dr. Sun Yat-sen |url=http://www.yatsen.gov.tw/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=153&Itemid=129 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140416192520/http://www.yatsen.gov.tw/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=153&Itemid=129 |archive-date=16 April 2014 |access-date=12 March 2014 |publisher=] |location=Taipei}}</ref> His birthplace was the village of ], ] (now ] City), Canton Province (now ]).<ref name=chron-nathall /> He was of ] and ]<ref name="作者:门杰丹">{{cite web |url=http://www.chinanews.com/n/2003-12-04/26/376869.html |script-title=zh:浓浓乡情系中原—访孙中山先生孙女孙穗芳博士 |trans-title=Central Plains Nostalgia-Interview with Dr. Sun Suifang, granddaughter of Sun Yat-sen |language=zh |author=门杰丹 |website=China News |date=4 December 2003 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110708144937/http://www.chinanews.com/n/2003-12-04/26/376869.html| archive-date=8 July 2011| url-status=live}} {{Google translation|en|zh-CN|http://www.chinanews.com/n/2003-12-04/26/376869.html|Translate this Chinese article to English}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bohr |first1=P. Richard |title=Did the Hakka Save China? Ethnicity, Identity, and Minority Status in China's Modern Transformation |journal=Headwaters |date=2009 |volume=26 |issue=3 |page=16 |url=https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/3/}}</ref> descent. His father owned very little land and worked as a tailor in ] and as a journeyman and a porter.<ref>{{cite book |date=1998 |title=Sun Yat-sen |url=https://archive.org/details/sunyatsen00berg |url-access=registration|publisher=Stanford University Press |page= |isbn=978-0804740111 }}</ref> After finishing primary education and meeting childhood friend ],<ref name="singtao1" /> he moved to ] in the ], where he lived a comfortable life of modest wealth supported by his elder brother ].<ref name="Maui">{{cite news | last = Kubota | first = Gary | title = Students from China study Sun Yat-sen on Maui | url = https://www.staradvertiser.com/2017/08/20/breaking-news/students-from-china-study-sun-yat-sen-on-maui/ | work = ] | location = Honolulu | date = 20 August 2017 | access-date = 21 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="KHON2SunMei">{{cite news | author = KHON web staff | title = Chinese government officials attend Sun Mei statue unveiling on Maui | url = https://khon2.com/2013/06/03/chinese-government-officials-attend-sun-mei-statue-unveiling-on-maui/ | work = ] | location = ] | date = 3 June 2013 | access-date = 21 August 2017 | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170822100129/http://khon2.com/2013/06/03/chinese-government-officials-attend-sun-mei-statue-unveiling-on-maui/ | archive-date = 22 August 2017 | df = dmy-all }}</ref><ref name="MauiSunPark">{{cite web | title = Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park | url = https://www.hawaii-guide.com/maui/sights/sun_yat_sen_memorial_park | work = Hawaii Guide | access-date = 21 August 2017}}</ref><ref name="MauiCountySunPark">{{cite web | title = Sun Yet Sen Park | url = https://co.maui.hi.us/Facilities/Facility/Details/Sun-Yet-Sen-Park-173 | website = ] | access-date = 21 August 2017 }}{{dead link|date=December 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| === Education === | |||

| ], Hong Kong.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| During his stay in Honolulu, Sun began his education at the age of 10,<ref name="singtao1" /> attending secondary school in Hawaii.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Gonschor |first=Lorenz |date=2 January 2017 |title=Revisiting the Hawaiian Influence on the Political Thought of Sun Yat-sen |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2017.1319128 |journal=The Journal of Pacific History |volume=52 |issue=1 |pages=52–67 |doi=10.1080/00223344.2017.1319128 |issn=0022-3344 |s2cid=157738017}}</ref> In 1878, after receiving a few years of local schooling, a 13-year-old Sun went to live with his elder brother ],<ref name="singtao1" /> who would later make major contributions to overthrowing the ], and who financed Sun's attendance of the ].<ref name="Maui" /><ref name="KHON2SunMei" /><ref name="MauiSunPark" /><ref name="MauiCountySunPark" /> There, he studied English, ], mathematics, science, and Christianity.<ref name="singtao1" /> Sun was initially unable to speak English, but quickly acquired it, received a prize for academic achievement from King ], and graduated in 1882.<ref name="DrSenIolaniSchool">{{Cite web |title=Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (class of 1882) |url=http://www.iolani.org/wn_aboutiolani_100305_cc.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110720185610/http://www.iolani.org/wn_aboutiolani_100305_cc.htm |archive-date=20 July 2011 |website=]}}</ref> He then attended ] (now known as ]) for one semester.<ref name="singtao1" /><ref>{{Cite news |last=Brannon |first=John |date=16 August 2007 |title=Chinatown park, statue honor Sun Yat-sen |url=http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2007/Aug/16/ln/hawaii708160313.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121004215858/http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2007/Aug/16/ln/hawaii708160313.html |archive-date=4 October 2012 |access-date=17 August 2007 |work=Honolulu Star-Bulletin |quote=Sun graduated from Iolani School in 1882, then attended Oahu College—now known as Punahou School—for one semester.}}</ref> By 1883, Sun's interest in Christianity had become deeply worrisome for his brother—who, seeing his conversion as inevitable, sent Sun back to China.<ref name="singtao1" /> | |||

| Upon returning to China, a 17-year-old Sun met with his childhood friend Lu Haodong at the Beiji Temple ({{lang|zh|北極殿}}) in Cuiheng,<ref name="singtao1" /> where villagers engaged in traditional ] and worshipped an ] of the ]. Feeling contemptuous of these practices,<ref name="singtao1" /> Sun and Lu incurred the wrath of their fellow villagers by breaking the wooden idol; as a result, Sun's parents felt compelled to dispatch him to Hong Kong.<ref name="singtao1" /><ref name="big5">{{Cite web |script-title=zh:基督教與近代中國革命起源:以孫中山為例 |url=http://big5.chinanews.com:89/hb/2011/04-02/2950599.shtml |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111028210411/http://big5.chinanews.com:89/hb/2011/04-02/2950599.shtml |archive-date=28 October 2011 |access-date=26 September 2011 |publisher=Big5.chinanews.com:89}}</ref> In November 1883, Sun began attending the Diocesan Home and Orphanage on ] (now the ]),<ref>{{Cite web |title=Central and Western Heritage Trail |url=https://www.amo.gov.hk/en/trails_west1.php?tid=18 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210709185852/https://www.amo.gov.hk/en/trails_west1.php?tid=18 |archive-date=9 July 2021 |access-date=6 July 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=17 November 2017 |title=The Diocesan Home and Orphanage |url=https://www.sunyatsenhistoricaltrail.hk/en/spots2.html |access-date=6 July 2021 |website=Sun Yat-sen Historic Trail}}</ref> and from 15 April 1884 he attended The Government Central School on ] (now ]), until graduating in 1886.<ref>{{Cite web |script-title=zh:中山史蹟徑一日遊 |url=http://www.lcsd.gov.hk/ce/Museum/Monument/yfoh/b5/sun_yat_sen.php |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111102031359/http://www.lcsd.gov.hk/ce/Museum/Monument/yfoh/b5/sun_yat_sen.php |archive-date=2 November 2011 |access-date=26 September 2011 |publisher=Lcsd.gov.hk}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=14 January 2018 |title=The Government Central School |url=https://www.sunyatsenhistoricaltrail.hk/en/spots5.html |access-date=6 July 2021 |website=Sun Yat-sen Historic Trail}}</ref> | |||

| After receiving a few years of local schooling, at age thirteen, Sun went to live with his elder brother Sun Mei, twelve years Sun Yat-sen's senior, who had immigrated to ], as a laborer and had become a prosperous ]. Sun studied at the ] where he learned ], ] and ]. Originally knowing nothing about the ], Sun Yat-sen picked up the language so quickly that he received a prize for outstanding achievement in English from ]. Sun then enrolled in ] for further studies but he was soon sent home to China as his brother, Sun Mei, was afraid that Sun Yat-sen was about to embrace ]. | |||

| In 1886, Sun studied medicine at the ] under the Christian missionary ].<ref name="singtao1" /> According to his book "Kidnapped in London", in 1887 Sun heard of the opening of the ] (the forerunner of the ]).<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Sun |first=Yat-sen |url=https://en.wikisource.org/Kidnapped_in_London/Chapter_1 |title=Kidnapped in London |chapter=The Imbroglio}}</ref> He immediately sought to attend, and went on to obtain a license to practice medicine from the institution in 1892;<ref name="singtao1" /><ref name="book2006" /> out of a class of twelve students, Sun was one of two who graduated.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Growing with Hong Kong: the University and its graduates: the first 90 years |publisher=Hong Kong University Press |year=2003 |isbn=978-962-209-613-4}}</ref><ref name="singtao2">''] Daily''. 28 February 2011. 特別策劃 section A10. "Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition".</ref><ref name="scmp1999">''South China Morning Post. "Birth of Sun heralds dawn of revolutionary era for China". 11 November 1999.</ref> | |||

| When he returned home in ], he was greatly troubled by what he saw as a backward China that demanded exorbitant taxes and levies from its people. The people were ], and the schools maintained their ancient methods leaving no opportunity for expression of thought or opinions. Under the influence of Christian missionaries in Hawaii, Sun had developed a disdain for superstition. One day, Sun and his childhood friend ] passed by ], a temple in Cuiheng Village, where they saw many villagers worshipping the Beiji (lit. '']'') Emperor-God in the temple and they broke off the hand of the statue. For this act the pair incurred the wrath of fellow villagers and escaped to ]. | |||

| == Religious views and Christian baptism == | |||

| Sun studied English at the Anglican Diocesan Home and Orphanage (current ], renamed in ]) in Hong Kong. In April ], Sun was transferred to the Central School of Hong Kong, later renamed ] in ]. Sun was later baptised in Hong Kong by Hickley, an American missionary of the Congressional Church of the United States, to his brother's concern. Sun pictured a ] as similar to the salvation mission of the Christian church]. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement. As a result, his baptismal name, Rixin, means refreshing the old with the new day by day. | |||

| In the early 1880s, Sun Mei had sent his brother to ʻIolani School, which was under the supervision of the ] and directed by an ] prelate, ], with the language of instruction being English. At the school, the young Sun first came in contact with Christianity. | |||

| Sun was later ] in Hong Kong on 4 May 1884 by ] ],<ref>"...At present there are some seven members in the interior belonging to our mission, and two here, one I baptized last Sabbath, a young man who is attending the Government Central School. We had a very pleasant communion service yesterday..." – Hager to Clark, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.17, p.3</ref><ref>"...We had a pleasant communion yesterday and received one Chinaman into the church..." – Hager to Pond, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.18, p.3 postscript</ref><ref>Rev. C. R. Hager, 'The First Citizen of the Chinese Republic', The Medical Missionary v.22 1913, p.184</ref> an American missionary of the ] (]), to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.<ref>]: 26</ref><ref name="Soong, 1997 p. 151-178">Soong, (1997) p. 151-178</ref> Sun attended To Tsai Church ({{lang|zh-hant|]}}), founded by the ] in 1888,<ref name="Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum">{{citation|url=http://hk.drsunyatsen.museum/download/brochure_07_a.pdf |script-title=zh:孫中山先生史蹟徑 |trans-title=Dr Sun Yat-sen Historical Trail |language=zh, en |author=中西區區議會 |work=Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum |location=Hong Kong, China |date=November 2006 |page=30 |access-date=15 September 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120224001159/http://hk.drsunyatsen.museum/download/brochure_07_a.pdf |archive-date=24 February 2012 }}</ref> while he studied medicine in ]. Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of the ]. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.<ref name="Soong, 1997 p. 151-178" /> | |||

| Ultimately, he earned a degree as a ] from the ] (the forerunner of ]) in ], of which he was one of the first two graduates. He subsequently practiced medicine in that city briefly in ]. He had an ] with fellow villager ] at age twenty; she bore him a son ], who would grow up to become a high ranking official in the government, and two daughters, Sun Yan and Sun Wan. | |||

| == Becoming a revolutionary == | |||

| ===Sun Yat-sen's early influence by Western ideology=== | |||

| === Four Bandits === | |||

| ]: ] (left), ] (middle), ] (right), and Guan Jingliang ({{lang|zh-hant|關景良}}, standing) at the ], circa 1888]] | |||

| During the Qing-dynasty rebellion around 1888, Sun was in Hong Kong with a group of revolutionary thinkers, nicknamed the ], at the ].<ref name="bard">Bard, Solomon. ''Voices from the past: Hong Kong, 1842–1918''. (2002). HK University Press. {{ISBN|978-9622095748}}. p. 183.</ref> | |||

| === From Furen Literary Society to Revive China Society === | |||

| Sun attached particular importance to the ideas of ] and ]. Sun often said that the formulation from Lincoln's ], "government of the people, by the people, for the people," had been the inspiration for the '']''. He incorporated these ideas, later in life, in two highly influential books. One, ''The Vital Problem of China'' (1917), analyzed some of the problems of ]: Sun warned that "…the ] treat nations as the ] farmer treats his worms; as long as they produce ], he cares for them well; when they stop, he feeds them to the fish." The second book, ''International Development of China'' (1921), presented detailed proposals for the development of ] in China, and attacked the ideology of ], as well as that of ] adhering more to the ideas of ]'s, particularly . His ideology remained flexible, however, reflecting his audience as much as his personal convictions. He presented himself as a strident ] to the nationalists, as a ] to the socialists, and an ] to the anarchists, declaring at one point that "the goal of the ] is to create ] and ]." It is an open matter of debate whether this eclecticism reflected a sincere effort to incorporate ideas from the multiple competing schools of thought or was simply opportunistic posturing. In any case, his ideological flexibility allowed him to become a key figure in the Nationalist movement since he was one of very few people who had good relations with all of the movements factions. | |||

| In 1891, Sun met revolutionary friends in Hong Kong including ] who was the leader and founder of the ].<ref name="Curthoys">Curthoys, Ann; Lake, Marilyn (2005). ''Connected worlds: history in transnational perspective''. ANU publishing. {{ISBN|978-1920942441}}. p. 101.</ref> The group was spreading the idea of overthrowing the Qing. In 1894, Sun wrote an 8,000-character petition to Qing ] ] presenting his ideas for modernizing China.<ref name="Wei">Wei, Julie Lee. Myers Ramon Hawley. Gillin, Donald G. (1994). ''Prescriptions for saving China: selected writings of Sun Yat-sen''. Hoover press. {{ISBN|978-0817992811}}.</ref><ref name="gtong146">{{cite book |author=王恆偉 |year=2006 |script-title=zh:中國歷史講堂 |script-chapter=zh:#5 清 |trans-chapter=Chapter 5. Qing dynasty |publisher=中華書局 |isbn=9628885286 |page=146}}</ref><ref>]: 39–40</ref> He traveled to ] to personally present the petition to Li but was not granted an audience.<ref>]: 40–41</ref> After that experience, Sun turned irrevocably toward revolution. He left China for Hawaii and founded the ], which was committed to revolutionizing China's prosperity. It was the first Chinese nationalist revolutionary society.<ref name="Yang 2023">{{cite book |last=Yang |first=Zhiyi |title=Poetry, History, Memory: Wang Jingwei and China in Dark Times |publisher=University of Michigan Press |publication-place=Ann Arbor, MI |date=2023 |isbn=978-0-472-07650-5 |doi=10.3998/mpub.12697845 |id={{OCLC|1404445939|1417484741}}|page=31|url=https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/121550 }}</ref> Members were drawn mainly from Chinese expatriates, especially from the lower social classes. The same month in 1894, the Furen Literary Society was merged with the Hong Kong chapter of the Revive China Society.<ref name="Curthoys" /> Thereafter, Sun became the secretary of the newly merged Revive China Society, which Yeung Ku-wan headed as president.<ref name="yang-bio">(Chinese) Yang, Bayun; Yang, Xing'an (2010). ''Yeung Ku-wan – A Biography Written by a Family Member''. Bookoola. p. 17. {{ISBN|978-9881804167}}</ref> They disguised their activities in Hong Kong under the running of a business under the name "Kuen Hang Club"<ref>{{cite book|last=Faure|first=David|title=Society|publisher=Hong Kong University Press|date=1997|isbn=978-9622093935|url=https://archive.org/details/documentaryhisto00davi}}, founder ]'s account</ref>{{rp|90}} ({{lang|zh-hant|乾亨行}}). | |||

| === Heaven and Earth Society and overseas travels to seek financial support === | |||

| Sun's admiration for these ideas filled him with dissatisfaction with the Qing government of China, and he began his political career by attempting to organize reform groups of Chinese exiles in Hong Kong. In October 1894 he founded the ] to unveil the goal of a prospering China and as the platform for future revolutionary activities. | |||

| A "Heaven and Earth Society" sect known as ] had been around for a long time.<ref name="Pina">João de Pina-Cabral. (2002). ''Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao''. Berg publishing. {{ISBN|978-0-8264-5749-3}}. p. 209.</ref> The group has also been referred to as the "three cooperating organizations", as well as the ].<ref name="Pina" /> Sun mainly used the group to leverage his overseas travels to gain further financial and resource support for his revolution.<ref name="Pina" /> | |||

| === |

=== First Sino-Japanese War === | ||

| In 1895, China suffered a serious defeat during the ]. There were two types of responses. One group of intellectuals contended that the ] Qing government could restore its legitimacy by successfully modernizing.<ref name="Bevir">Bevir, Mark (2010). ''Encyclopedia of Political Theory''. Sage publishing. {{ISBN|978-1412958653}}. p 168.</ref> Stressing that overthrowing the Manchu would result in chaos and would lead to China being carved up by imperialists, intellectuals like ] and ] supported responding with initiatives like the ].<ref name="Bevir" /> In another faction, Sun Yat-sen and others like ] wanted a revolution to replace the dynastic system with a modern ] in the form of a ].<ref name="Bevir" /> The Hundred Days' reform turned out to be a failure by 1898.<ref>Lin, Xiaoqing Diana. (2006). Peking University: ''Chinese Scholarship And Intellectuals, 1898–1937''. SUNY Press, {{ISBN|978-0791463222}}. p. 27.</ref> | |||

| == First uprising and exile == | |||

| In ] a ] he plotted failed, and for the next sixteen years Sun was an ] in ], the ], ], and ], raising money for his revolutionary party and bankrolling uprisings in China. In Japan, where he was known as Nakayama Shō (]: 中山樵, lit. ''The Woodcutter of Middle Mountain''), he joined ] Chinese groups (which later became the ]) and soon became their leader. He was expelled from Japan and went to the United States. | |||

| === First Guangzhou Uprising === | |||

| ] marking the site of a house at 4 Warwick Court, WC1, in which Sun Yat-sen lived in exile]] | |||

| ] announcing to him that he has assumed the Presidency of the Provisional Republican Government of China, dated 21 January 1912]] | |||

| In the second year of the establishment of the Revive China Society, on 26 October 1895, the group planned and launched the ] against the Qing in ].<ref name="gtong146" /> ] directed the uprising starting from Hong Kong.<ref name="yang-bio" /> However, plans were leaked out, and more than 70 members, including ], were captured by the Qing government. The uprising was a failure. Sun received financial support mostly from his brother, who sold most of his 12,000 acres of ranch and cattle in Hawaii.<ref name="Maui" /> Additionally, members of his family and relatives of Sun would take refuge at the home of his brother Sun Mei at Kamaole in ], ].<ref name="Maui" /><ref name="KHON2SunMei" /><ref name="MauiSunPark" /><ref name="MauiCountySunPark" /><ref name="MauiMagazine" /> | |||

| === Exile in the United Kingdom === | |||

| On ], ], a military ] in which Sun had no direct involvement (at that moment Sun was still on exile and ] was in charge of the revolution), began a process that ended over two thousand years of imperial rule in China. When he learned of the successful rebellion against the ] emperor from press reports, Sun immediately returned to China from the United States. Later, on ], a meeting of representatives from provinces in ] elected Sun as the provisional ] and set the ] of 1912 as the first day of the First Year of the Republic. This republic calendar system is still used in ] today. | |||

| While in exile in ] in 1896, Sun raised money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. While the events leading up to it are unclear, Sun Yat-sen was detained at the ], where the Chinese secret service planned to smuggle him back to China to execute him for his revolutionary actions.<ref>{{cite web |url = https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sun-Yat-sen |title = Sun Yat-sen {{!}} Chinese leader |website = Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date = 31 March 2018}}</ref> He was released after 12 days by the efforts of ], '']'', '']'', and the ], which left Sun a hero in the United Kingdom.{{NoteTag|Contrary to a popular legend, Sun entered the Legation voluntarily although he was prevented from leaving. The Legation planned to execute him and to return his body to Beijing for ritual beheading. Cantlie, his former teacher, was refused a writ of '']'' because of the Legation's ], but he began a campaign through '']''. Through diplomatic channels, the ] persuaded the Legation to release Sun.<ref>{{cite book |title = The Origins of a Heroic Image: SunYat Sen in London, 1896–1987 |last = Wong |first = J.Y. |year = 1986 |publisher = Oxford University Press |location=Hong Kong}} | |||

| <br /> as summarized in | |||

| <br />{{cite book |title = The Most Fundamental Legal Right: Habeas Corpus in the Commonwealth |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=B9rYW5xPYEwC&q=Chinese+Legation+London&pg=PA162 |last = Clark |first = David J. |author2=Gerald McCoy |year = 2000 |page = 162 |publisher = Oxford University Press |location = Oxford|isbn = 978-0198265849}}</ref>}} James Cantlie, Sun's former teacher at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, maintained a lifelong friendship with Sun and later wrote an early biography of him<ref>{{cite book |last=Cantlie |first=James |title = Sun Yat Sen and the Awakening of China |year=1913 |publisher=Jarrold & Sons |location=London}}</ref> Sun wrote a book in 1897 about his detention, "Kidnapped in London."<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| === Exile in Japan === | |||

| The official history of the ] (and for that matter, the ]) emphasizes Sun's role as the first provisional President, but many historians now question the importance of Sun's role in the 1911 revolution and point out that he had no direct role in the Wuchang uprising and was in fact out of the country at the time. In this interpretation, his naming as the first provisional President was precisely because he was a respected but rather unimportant figure and therefore served as an ideal compromise candidate between the revolutionaries and the conservative ]. | |||

| Sun traveled by way of ] to ] to begin his exile there. He arrived in ] on 16 August 1897 and met with the Japanese politician ]. Most Japanese who actively worked with Sun were motivated by a ] opposition to ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://old.japanfocus.org/_Sato_Kazuo-Sun_Yat_sen_s_1911_Revolution_had_Its_Seeds_in_Tokyo |title=JapanFocus |publisher=Old.japanfocus.org |access-date=26 September 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120316134631/http://old.japanfocus.org/_Sato_Kazuo-Sun_Yat_sen_s_1911_Revolution_had_Its_Seeds_in_Tokyo |archive-date=16 March 2012 }}</ref> In Japan, Sun also met ], a diplomat of the ].<ref>Thornber, Karen Laura. (2009). ''Empire of Texts in Motion: Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Transculturations of Japanese Literature''. Harvard University Press. p. 404.</ref> | |||

| Sun is highly regarded as the National Father of modern China. His political philosophy, known as the '']'', was proclaimed in August ]. In his ''Methods and Strategies of Establishing the Country'' completed in ], he suggested using his Principles to establish ultimate ], ], and ] in the country. | |||

| During the ] and the ], Sun helped Ponce procure weapons that had been salvaged from the ] and ship the weapons to the Philippines. By helping the Philippine Republic, Sun hoped that the Filipinos would retain their independence so that he could be sheltered in the country in staging another Chinese revolution. However, as the war ended in July 1902, the United States emerged victorious from a bitter three-year war against the Republic. Therefore, Sun did not have the opportunity to ally with the Philippines in his revolution in China.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Ocampo|first1=Ambeth|title=Looking Back 2|date=2010|publisher=Anvil Publishing|location=Pasig|pages=8–11}}</ref> | |||

| ===Republic of China=== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1897, through an introduction by ], Sun Yat-sen met ] of the political organization ]. Through Tōyama, he received financial support for his activities and living expenses in Tokyo from {{ill|Hiraoka Kotarō|lt=|ja|平岡浩太郎}}. Additionally, his residence, a 2,000-square-meter mansion in Waseda-Tsurumaki-cho, was arranged by ]. | |||

| After taking the oath of office, Sun Yat-sen sent ]s to the leaders of all provinces, requesting them to elect and send new ]s to establish the ]. Then the provisional government organizational guidelines and the provisional law of the Republic were declared as the basic law of the country by the Assembly. | |||

| In 1899, the ] occurred.<ref>義和団事件 大辞林 第三版</ref> The following year, Sun Yat-sen attempted another uprising in Huizhou, but it ended in failure. In 1902, despite already having a wife in China, he married the ] woman ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|author=久保田文治|year=2010|title=孫文と大月薫・宮川冨美子|journal=孫文研究|volume=47|page=}}</ref> Furthermore, he kept {{ill|Asada Haru|lt=|ja|浅田春}} as a mistress and frequently had her accompany him. | |||

| The provisional government was in a very weak position. The southern provinces of China had declared independence from the Qing dynasty, but most of the northern provinces had not. Moreover, the provisional government did not have military forces of its own, and its control over elements of the ] that had mutinied was limited, and there were still significant forces which had not declared against the Qing. | |||

| == From failed uprisings to revolution == | |||

| The major issue before the provisional government was gaining the support of ], the man in charge of the ], the military of northern China. After promising Yuan the presidency of the new Republic, Yuan sided with the revolution and forced the ] to abdicate. Later, Yuan proclaimed himself emperor and afterwards opposition snowballed against Yuan's dictatorial methods. In ] Sun led an unsuccessful revolt against Yuan, and he was forced to seek asylum in Japan, where he reorganized the Kuomintang. He married ], one of the ], in Japan on ], ], without divorcing his first wife Lu Muzhen due to opposition from the Chinese community. Lu pleaded with him to take Soong as a concubine but this was also unacceptable to Sun's ]. | |||

| === Huizhou Uprising === | |||

| On 22 October 1900, Sun ordered the launch of the ] to attack ] and provincial authorities in Guangdong.<ref>Gao, James Zheng. (2009). ''Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949)''. Scarecrow Press. {{ISBN|978-0810849303}}. Chronology section.</ref> That came five years after the failed Guangzhou Uprising. This time, Sun appealed to the ] for help.<ref>]: 86</ref> The uprising was another failure. Miyazaki, who participated in the revolt with Sun, wrote an account of the revolutionary effort under the title "33-Year Dream" ({{lang|zh-hant|三十三年之夢}}) in 1902.<ref>{{cite book |author=劉崇稜 |year=2004 |script-title=zh:日本近代文學精讀 |isbn=978-9571136752 |page=71|publisher=五南圖書出版股份有限公司 }}</ref><ref>Frédéric, Louis. (2005). ''Japan Encyclopedia''. Harvard University Press. {{ISBN|978-0674017535}}. p. 651.</ref><ref> Taiwan Ebook, ]</ref> | |||

| === Getting support from Siamese Chinese === | |||

| ===Guangzhou militarist government=== | |||

| In 1903, Sun made a secret trip to ] in which he sought funds for his cause in Southeast Asia. His loyal followers published newspapers, providing invaluable support to the dissemination of his revolutionary principles and ideals among ] in ]. In Bangkok, Sun visited ], in the city's ]. On that street, Sun gave a speech claiming that ] were "the Mother of the Revolution." He also met the local Chinese merchant Seow Houtseng,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://dspace.wul.waseda.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2065/39825/3/AjiaTaiheiyoTokyu_21_Murashima.pdf|title=The Origins of Chinese Nationalism in Thailand|author=Eiji Murashima|publisher=Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies (Waseda University)|access-date=30 March 2017|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170330180058/https://dspace.wul.waseda.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2065/39825/3/AjiaTaiheiyoTokyu_21_Murashima.pdf|archive-date=30 March 2017}}</ref> who sent financial support to him. | |||

| Sun's speech on Yaowarat Road was commemorated by the street later being named "Sun Yat Sen Street" or "Soi Sun Yat Sen" ({{langx|th|ซอยซุนยัตเซ็น}}) in his honour.<ref>{{cite web|author=Eric Lim|url=http://www.tour-bangkok-legacies.com/soi-sun-yat-sen.html |title=Soi Sun Yat Sen the legacy of a revolutionary|publisher=Tour Bangkok Legacies |access-date=30 March 2017}}</ref> | |||

| In the late ], China was greatly divided by different military leaders without a proper central government. Sun saw the danger of this, and returned to China in ] to advocate unification. He started a self-proclaimed military government in ] (now Guangzhou), southern China, in ], and was elected as president and general. | |||

| ===Getting support from American Chinese=== | |||

| In ], he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed his '']'' as the foundation of the country and the ] as the guideline for the political system and bureaucracy. Part of the speech was made into the ]. | |||

| According to Lee Yun-ping, chairman of the Chinese historical society, Sun needed a certificate to enter the United States since the ] would have otherwise blocked him.<ref name="sfworldjournal">{{cite news |script-title=zh:孫中山思想 3學者演說精采 |url=http://sf.worldjournal.com/view/full_sf/12160552/article-孫中山思想-3學者演說精采?instance=top_rec |work=World journal |date=4 March 2011 |access-date=26 September 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130513181852/http://sf.worldjournal.com/view/full_sf/12160552/article-%E5%AD%AB%E4%B8%AD%E5%B1%B1%E6%80%9D%E6%83%B3-3%E5%AD%B8%E8%80%85%E6%BC%94%E8%AA%AA%E7%B2%BE%E9%87%87?instance=top_rec |archive-date=13 May 2013}}</ref> | |||

| In March 1904, while residing in ], ], Sun Yat-sen obtained a Certificate of Hawaiian Birth, issued by the ], stating that "he was born in the ] on the 24th day of November, A.D. 1870."<ref name="Certificate of Live Birth in Hawaii">{{cite web |url=https://www.scribd.com/doc/9830547/Sun-Yatsen-Certification-of-Live-Birth-in-Hawaii |title=Sun Yat-sen: Certification of Live Birth in Hawaii |publisher=] |location=San Francisco, CA, US |access-date=15 September 2012}}</ref><ref name=smys00honu /> He renounced it after it served its purpose to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act.<ref name="smys00honu">Smyser, A.A. (2000). . Honolulu Star Bulletin. "Sun renounced it in due course. It did, however, help him circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which became applicable when Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898."</ref> Official files of the United States show that Sun had United States nationality, moved to China with his family at age 4, and returned to Hawaii 10 years later.<ref name="NARA">{{cite web |url=http://media.nara.gov/pacific/san-francisco/gallery/9995-Cabin-Sun-Yat-Sen.pdf |title=Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925 |author=Department of Justice. Immigration and Naturalization Service. San Francisco District Office |author-link=Immigration and Naturalization Service |work=<!-- https://research.archives.gov/description/414 --> Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004 ] |id={{NARA catalog record|296446|Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925}} |pages=92–152 |publisher=] |location=Washington, DC, US |access-date=15 September 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131016060255/http://media.nara.gov/pacific/san-francisco/gallery/9995-Cabin-Sun-Yat-Sen.pdf |archive-date=16 October 2013}} Note that one immigration official recorded that Sun was born in ], a district of ], Hawaii.</ref> | |||

| To develop the military power needed for the ] against the militarists at ], he established the ] near Guangzhou, with ] as its ] and with such party leaders as ] and ] as political instructors. The Academy kept running during the rest of the Republic of China and continues to serve as a major military school in the ] today. | |||

| On 6 April 1904, on his first attempt to enter the United States, Sun Yat-sen landed in ]. He was detained and faced with possible deportation.<ref name="sfworldjournal" /> Sun, represented by the law firm of Ralston & Siddons, based in ], filed an appeal with the Commissioner-General of Immigration on 26 April 1904. On 28 April 1904, the acting secretary of the ] in a four-page decision contained in the case file, set aside the order of deportation and ordered the Commissioner of Immigration in San Francisco to "permit the said Sun Yat-sen to land." Sun was then freed to embark on his fundraising tour in the United States.<ref name="sfworldjournal" /> | |||

| ===Way to Northern Expedition and death=== | |||

| ] | |||

| === Returned to exile in Japan === | |||

| In the early ] Sun received help from the ] for his reorganization of the Kuomintang as a ] ] Party and negotiated the ]. In ], in order to hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active cooperation with the ]. | |||

| In 1900, Sun Yat-sen temporarily ]d himself to Japan again. During his stay in Japan, he expressed his thoughts to ], saying, "The ] is the first step of the Chinese revolution, and the Chinese revolution is the second step of the Meiji Restoration."<ref>『孫文選集(第三巻)』社会思想社、1989、 ISBN 4390602802</ref> | |||

| By this time, Sun was convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period of political tutelage that would culminate in the transition to ]. Sun then prepared for the later Northern Expedition with help from foreign powers such as Japan and the U.S. until his death. | |||

| Around this time, Sun married ], the second daughter of {{ill|Soong Jiashu|lt=|ja|宋嘉澍}}, who was also a Hakka like him. There are various theories about the year of their marriage, but it is generally believed to have taken place between ] and ] while Sun was exiled in Japan. The arrangement of their marriage was supported by ], a Japanese supporter who provided financial aid.<ref name="NHK2007-02-25">2007年2月25日NHK BS1 『世界から見たニッポン~大正編』</ref><ref name="yomiuri2002-10">{{Cite book|editor=読売新聞西部本社|editor-link=読売新聞|date=October 2002|title=梅屋庄吉と孫文 盟約ニテ成セル|publisher=海鳥社|isbn=4-87415-405-0|ref=読売新聞2002}}</ref> | |||

| ---------------- | |||

| Yeah, deomcracy at end of his gun. Fucked the south and fucked every god damn Chinese until they know how great Sun's version of bull shit is. Please.... go fucked yourself before writing this farce! You wouldn't know the first thing about democracy!! | |||

| At that time, ], a prominent figure in Japan’s political and business circles, invited Sun to his villa, the Nihonkan, located where the current restaurant "Kochuan" in Shirokane Happo-en stands. Kuhara offered Sun the newly built "Orchid Room" to encourage and support his friend living in a foreign land. | |||

| Iron_Jackal_Tw | |||

| The Orchid Room was equipped with a secret escape route known as "Sun Yat-sen's Escape Passage." This precautionary measure included a hidden door behind the fireplace, which led to an underground tunnel, providing an escape route in case of emergencies. | |||

| ----------------- | |||

| ===Unifying forces of Tongmenghui in Tokyo=== | |||

| On ] ], Sun traveled north and delivered another speech to suggest gathering a conference for the Chinese people and the abolition of all unfair treaties with the Western powers. Two days later, he yet again traveled to ] (now Beijing) to discuss the future of the country, despite his deteriorating health and the ongoing civil war of the ]s. Although ill at the time, he was still head of the southern government. On ] ] Sun traveled to Japan and gave a remarkable ] at ] ]. He left Canton to hold peace talks with the northern regional leaders on the unification of China. Sun died of ] on ], ], at the age of fifty eight, in Beijing. | |||

| {{Main|Tongmenghui}} | |||

| ] in Hong Kong]] | |||

| In 1904, Sun Yat-sen came about with the goal "to expel the ] barbarians (specifically, the Manchu), to revive ], to establish a Republic, and to ] equally among the people" ({{lang|zh-hant|驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權}}).<ref name="chinahistvol1">計秋楓, 朱慶葆. (2001). 中國近代史, Volume 1. Chinese University Press. {{ISBN|978-9622019874}}. p. 468.</ref> One of Sun's major legacies was the creation of his political philosophy of the ]. These Principles included the principle of nationalism (minzu, {{lang|zh|民族}}), of democracy (minquan, {{lang|zh-hant|民權}}), and of welfare (minsheng, {{lang|zh|民生}}).<ref name="chinahistvol1" /> | |||

| On 20 August 1905, Sun joined forces with revolutionary Chinese students studying in Tokyo to form the unified group ] (United League), which sponsored uprisings in China.<ref name="chinahistvol1" /><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.countriesquest.com/asia/china/history/imperial_china/the_manchu_qing_dynasty_1644-1911/internal_threats.htm |title=Internal Threats – The Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) – Imperial China – History – China – Asia |publisher=Countriesquest.com |access-date=26 September 2011}}</ref> By 1906 the number of Tongmenghui members reached 963.<ref name="chinahistvol1" /> | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| === Getting support from Malayan Chinese === | |||

| A struggle for Sun's power between Chiang Kai-shek and ] broke out immediately after Sun's death. This created much inefficiency in the administration of the country and largely delayed the Northern Expedition. | |||

| {{Main|Chinese revolutionary activities in Malaya}} | |||

| ] featuring Sun's items and photos]] | |||

| ] in ], ], ], where he planned the ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Streets of George Town, Penang|url=https://archive.org/details/streetsofgeorget00khoo|url-access=registration|year=2007|publisher=Areca Books|isbn=978-9839886009|pages=–}}</ref>]] | |||

| Sun's notability and popularity extended beyond the ] region, particularly to ] (Southeast Asia), where a large concentration of ] resided in ] (] and Singapore). In Singapore, he met the local Chinese merchants Teo Eng Hock ({{lang|zh-hant|張永福}}), Tan Chor Nam ({{lang|zh-hant|陳楚楠}}) and Lim Nee Soon ({{lang|zh-hant|林義順}}), which mark the commencement of direct support from the ] Chinese. The Singapore chapter of the Tongmenghui was established on 6 April 1906,<ref name="yanq">Yan, Qinghuang. (2008). ''The Chinese in Southeast Asia and beyond: socioeconomic and political dimensions''. World Scientific publishing.{{ISBN|978-9812790477}}. pp. 182–187.</ref> but some records claim the founding date to be end of 1905.<ref name="yanq" /> The ] used by Sun was known as ].<ref name="yanq" /><ref name="wanqingyuan1">{{cite web |url=http://www.wanqingyuan.org.sg/ |title=Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall |publisher=Wanqingyuan.org.sg |access-date=7 May 2015 |archive-date=20 August 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130820170031/http://www.wanqingyuan.org.sg/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> Singapore then was the headquarters of the Tongmenghui.<ref name="yanq" /> | |||

| After founding the Tongmenghui, Sun advocated the establishment of the '']'' as the alliance's mouthpiece to promote revolutionary ideas. Later, he initiated the establishment of reading clubs across Singapore and Malaysia to disseminate revolutionary ideas by the lower class through public readings of newspaper stories. The United Chinese Library, founded on 8 August 1910, was one such reading club, first set up at leased property on the second floor of the Wan He Salt Traders in North Boat Quay.<ref>{{cite web |title=United Chinese Library |url=https://roots.sg/Content/Places/historic-sites/united-chinese-library |website=Roots |publisher=National Heritage Board |access-date=15 September 2019 |archive-date=3 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191203123922/https://roots.sg/Content/Places/historic-sites/united-chinese-library |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| In addition, Sun is also one of the primary ]s of the ]ese ] ]. | |||

| The first actual United Chinese Library building was built between 1908 and 1911 below Fort Canning, on 51 Armenian Street, commenced operations in 1912. The library was set up as a part of the 50 reading rooms by the Chinese republicans to serve as an information station and liaison point for the revolutionaries. In 1987, the library was moved to its present site at Cantonment Road. | |||

| ===Power struggle=== | |||

| === Uprisings === | |||

| After Sun's death, a power struggle between his young ''protégé'' Chiang Kai-shek and his old revolutionary comrade Wang Jingwei split the KMT. At stake in this struggle was the right to lay claim to Sun's ambiguous legacy. When the Communists and the Kuomintang split in ], marking the start of the ], each group claimed to be his true heirs. In addition, during ], both the anti-Japanese government of Chiang Kai-shek and the pro-Japanese ] of ] claimed to be the rightful heirs of Sun's legacy. | |||

| On 1 December 1907, Sun led the ] against the Qing at ], which is the border between ] and ].<ref name="Khoo">Khoo, Salma Nasution. (2008). ''Sun Yat Sen in Penang''. Areca publishing. {{ISBN|978-9834283483}}.</ref> The uprising failed after seven days of fighting.<ref name="Khoo" /><ref>Tang Jiaxuan (2011). ''Heavy Storm and Gentle Breeze: A Memoir of China's Diplomacy''. HarperCollins publishing. {{ISBN|978-0062067258}}.</ref> In 1907, there were a total of four failed uprisings, including ], ] and ].<ref name="yanq" /> In 1908, two more uprisings failed: the ] and ].<ref name="yanq" /> | |||

| === Anti-Sun factionalism === | |||

| The official veneration of Sun's memory (especially in the Kuomintang) was a virtual ], which centered around his tomb in ]. His widow, the former Soong Ching-ling, sided with the Communists during the Chinese Civil War and served from ] to ] as Vice President (or Vice Chairwoman) of the ] and as Honorary President shortly before her death in 1981. | |||

| Because of the failures, Sun's leadership was challenged by elements from within the Tongmenghui who wished to remove him as leader. In Tokyo, members from the recently merged ] raised doubts about Sun's credentials.<ref name="yanq" /> ] and ] publicly denounced Sun in an open leaflet, "A declaration of Sun Yat-sen's Criminal Acts by the Revolutionaries in Southeast Asia",<ref name="yanq" /> which was printed and distributed in reformist newspapers like ''Nanyang Zonghui Bao''.<ref name="yanq" /><ref>Nanyang Zonghui bao. The Union Times paper. 11 November 1909 p2.</ref> The goal was to target Sun as a leader leading a revolt only for ].<ref name="yanq" /> | |||

| The revolutionaries were polarized and split between pro-Sun and anti-Sun camps.<ref name="yanq" /> Sun publicly fought off comments about how he had something to gain financially from the revolution.<ref name="yanq" /> However, by 19 July 1910, the Tongmenghui headquarters had to relocate from Singapore to Penang to reduce the anti-Sun activities.<ref name="yanq" /> It was also in Penang that Sun and his supporters would launch the first Chinese "daily" newspaper, the '']'', in December 1910.<ref name="Khoo" /> | |||

| ===National Father=== | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| === 1911 revolution === | |||

| Sun Yat-sen remains unique among twentieth-century Chinese leaders for having a high reputation both in ] and in Taiwan. In Taiwan, he is seen as the Father of the ], and is known by the ] ''National Father, Mr. Sun Chungshan'' (]: 國父 孫中山先生, where the one-character space is a traditional homage symbol). His picture is still almost always found in ceremonial locations such as in front of legislatures and classrooms of public schools (from elementary to senior high school), and he continues to appear in new coinage and currency. | |||

| {{Main|Wuchang Uprising|Xinhai Revolution}} | |||

| ] fighting in the ]]] | |||

| To sponsor more uprisings, Sun made a personal plea for financial aid at the ], held on 13 November 1910 in Malaya.<ref name="Bergere188">]: 188</ref> The high-powered preparatory meeting of Sun's supporters was subsequently held in Ipoh, Singapore, at the villa of Teh Lay Seng, the chairman of the Tungmenghui, to raise funds for the ], also known as the Yellow Flower Mound Uprising.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Chan|first=Sue Meng|title=Road to Revolution: Dr. Sun Yat Sen and His Comrades in Ipoh. Singapore|publisher=Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall|year=2013|isbn=978-9810782092|location=Singapore|page=17}}</ref> The Ipoh leaders were Teh Lay Seng, Wong I Ek, Lee Guan Swee, and Lee Hau Cheong.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Khoo & Lubis|first=Salma Nassution & Abdur-Razzaq|title=Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development|publisher=Areca Books|year=2005|page=231}}</ref> The leaders launched a major drive for donations across the ]<ref name=Bergere188 /> and raised ]187,000.<ref name=Bergere188 /> | |||

| On 27 April 1911, the revolutionary ] led the ] Uprising against the Qing. The revolt failed and ended in disaster. The bodies of only 72 revolutionaries were identified of the 86 that were found.<ref name="gtong195">王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 5 清. 中華書局. {{ISBN|9628885286}}. pp. 195–198.</ref> The revolutionaries are remembered as ].<ref name="gtong195" /> | |||

| This stands in sharp contrast to ], whose pictures were mostly removed from public places in the ], and whose likeness has gradually disappeared from coinage and currency. Much of the difference may be attributed to the fact that unlike Chiang, Sun played no role in governing Taiwan, so invoking Sun produces much less of a negative reaction among supporters of ] than invoking other figures of the Kuomintang. | |||

| Despite the failure of this uprising, which was due to a leak, it was successful in triggering off the trend of nation-wide revolts.<ref></ref> | |||

| On 10 October 1911, the military ] took place and was led again by Huang Xing. The uprising expanded to the ], also known as the "Chinese Revolution", to overthrow the last emperor, ].<ref>Carol, Steven. (2009). ''Encyclopedia of Days: Start the Day with History''. iUniverse publishing. {{ISBN|978-0595482368}}.</ref> Sun had no direct involvement in it, as he was in ], ], and had spent much of the year in the United States in search of support from ]. That made Huang be in charge of the revolution that ended over 2000 years of imperial rule in China. On 12 October, when Sun learned of the successful rebellion against the Qing emperor from press reports, he returned to China from the United States and was accompanied by his closest foreign advisor, the American "General" ], an adventurer whom Sun had met in London when they attempted to arrange British financing for the future Chinese republic. Both sailed for China, arriving there on 21 December 1911.<ref>]: 210</ref> | |||

| --------------------------- | |||

| {{clear left}} | |||

| He is a creator for the republic of bull shit. Insincere attempt to bull shit more people to give up their rights. There is only one democracy for the future, and that's Taiwanese democracy with a US Consitution. You can take that Sun shit and shovel it back down your own throat. | |||

| == Republic of China with multiple governments == | |||

| The most powerful branch in America is the Congress not the President, and those power are given to them by the people with our consent. Sun was educated in British. He can take his British shit and eat it. Of course, he already did. History and time are true judgment of that!! | |||

| === Provisional government === | |||

| {{Main|Provisional Government of the Republic of China (1912)}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| On 29 December 1911, a meeting of representatives from provinces in Nanjing elected Sun as the ].<ref>Lane, Roger deWardt. (2008). ''Encyclopedia Small Silver Coins''. {{ISBN|978-0615244792}}.</ref> 1 January 1912 was set as the ] of the new ].<ref name="Well">Welland, Sasah Su-ling. (2007). ''A Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sisters''. Rowman Littlefield Publishing. {{ISBN|978-0742553149}}. p. 87.</ref> ] was made provisional vice-president, and Huang Xing became the minister of the army. A new ] for the Republic of China was created, along with a ]. Sun is credited for funding the revolutions and for keeping revolutionary spirit alive, even after a series of false starts. His successful merger of smaller revolutionary groups into a single coherent party provided a better base for those who shared revolutionary ideals. Under Sun's provisional government, several innovations were introduced, such as the aforementioned calendar system, and fashionable ]. | |||

| === Beiyang government === | |||

| Iron_Jackal_Tw | |||

| {{Main|Beiyang government}} | |||

| ], who was in control of the ], had been promised the position of president of the Republic of China if he could get the Qing court to abdicate.<ref name="Fu" /> On 12 February 1912, the Emperor did abdicate the throne.<ref name="Well" /> Sun stepped down as president, and Yuan became the new provisional president in Beijing on 10 March 1912.<ref name="Fu" /> The provisional government did not have any military forces of its own. Its control over elements of the new army that had mutinied was limited, and significant forces still had not declared against the Qing. | |||

| Sun Yat-sen sent telegrams to the leaders of all provinces to request them to elect and to establish the ] in 1912.<ref>]: 226</ref> In May 1912, the legislative assembly moved from Nanjing to Beijing, with its 120 members divided between members of the Tongmenghui and a republican party that supported Yuan Shikai.<ref name="chien">Ch'ien Tuan-sheng. ''The Government and Politics of China 1912–1949''. Harvard University Press, 1950; rpr. Stanford University Press. {{ISBN|978-0804705516}}. pp. 83–91.</ref> Many revolutionary members were already alarmed by Yuan's ambitions and the northern-based ]. | |||

| ===Sun's posthumous popularity on Mainland China=== | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| === New Nationalist party in 1912, failed Second Revolution and new exile === | |||

| On the ], Sun is also seen as a Chinese ] and proto-], and is highly regarded as the ''Forerunner of the Revolution''. He is mentioned by name in the preamble to the ]. In most major Chinese cities one of the main streets is named 中山 "Zhongshan" to memorialize him (along with 人民路 "Renmin Lu", or '''The People's Road''' and 解放路 "Jiefang Lu", or '''Liberation Road'''). | |||

| The Tongmenghui member ] quickly tried to control the assembly. He mobilized the old Tongmenghui at the core with the mergers of a number of new small parties to form a new political party, the ] (Chinese Nationalist Party, commonly abbreviated as "KMT") on 25 August 1912 at ], Beijing.<ref name="chien" /> The ] was considered a huge success for the KMT, which won 269 of the 596 seats in the lower house and 123 of the 274 seats in the upper house.<ref name="Fu">Fu, Zhengyuan. (1993). ''Autocratic tradition and Chinese politics''(Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|978-0521442282}}). pp. 153–154.</ref><ref name="chien" /> In retaliation, the KMT leader ] was assassinated, almost certainly by a secret order of Yuan, on 20 March 1913.<ref name="Fu" /> The ] took place by Sun and KMT military forces trying to overthrow Yuan's forces of about 80,000 men in an armed conflict in July 1913.<ref>Ernest Young, "Politics in the Aftermath of Revolution", in John King Fairbank, ed., ''The Cambridge History of China: Republican China 1912–1949'', Part 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1983; {{ISBN|978-0521235419}}), p. 228.</ref> The revolt against Yuan was unsuccessful. In August 1913, Sun fled to Japan, where he later enlisted financial aid by the politician and industrialist ].<ref>Altman, Albert A., and Harold Z. Schiffrin. "Sun Yat-Sen and the Japanese: 1914–16." Modern Asian Studies, vol. 6, no. 4, 1972, pp. 385–400. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/311539</ref> | |||

| === Warlords chaos === | |||

| In recent years, the leadership of the ] has been increasingly invoking Sun, partly as a way of bolstering ] in light of ] and partly to increase connections with supporters of the ] on ] which the PRC sees as allies against Taiwanese independence. Sun's tomb was one of the first stops made by the leaders of both the ] and the ] on their trips to mainland China in ]. Furthermore, a massive picture of Sun now appears in ] for ] while pictures of ] and ] no longer appear. | |||

| In 1915, Yuan proclaimed the ] with himself as ]. Sun took part in the ] of the ] and also supported bandit leaders like ] during the ], which marked the beginning of the ]. In 1915, Sun wrote to the ], a ]-based organization in ], and asked it to send a team of specialists to help China set up the world's first socialist republic.<ref>''South China Morning post''. Sun Yat-sen's durable and malleable legacy. 26 April 2011.</ref> The same year, Sun received the ]n communist ] as a guest.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Thampi |first1=Madhavi |title=India and China in the Colonial World |publisher=Taylor & Francis |page=229}}</ref> There were then ] of what China could be. In the political mess, both Sun Yat-sen and ] were announced as president of the Republic of China.<ref>South China morning post. 1913–1922. 9 November 2003.</ref> | |||

| == Alliance with Communist Party and Northern Expedition == | |||

| ===Sun and the overseas Chinese=== | |||

| {{Further|Northern Expedition}} | |||

| === Guangzhou militarist government === | |||

| Sun's notability and popularity extends beyond the ] region, particularly to ] where a large concentration of ] reside in ]. Sun recognised the contributions which the large number of overseas Chinese can make beyond the sending of remittances to their ancestral homeland, and therefore made multiple visits to spread his revolutionary message to these communities around the world. | |||

| ], ], Sun Yat-sen and ] at the founding of the ] in 1924]] | |||

| China had become divided among regional military leaders. Sun saw the danger and returned to China in 1916 to advocate ]. In 1921, he started a self-proclaimed military government in ] and was elected ].<ref name="Bergere273">]: 273</ref> Between 1912 and 1927, three governments were set up in South China: the ], the Military government in Guangzhou (1921–1925), and the National government in Guangzhou and later ] (1925–1927).<ref>Kirby, William C. (2000). ''State and economy in republican China: a handbook for scholars'', volume 1. Harvard publishing. {{ISBN|978-0674003682}}. p. 59.</ref> The governments in the south were established to rival the Beiyang government in the north.<ref name=Bergere273 /> Yuan Shikai had banned the KMT. The short-lived ] was a temporary replacement for the KMT. On 10 October 1919, Sun resurrected the KMT with the new name ] ], or "Nationalist Party of China."<ref name="chien" /> | |||

| === First United Front === | |||

| Sun made a total of eight visits to Singapore between ] and ]. His first visit made on ] ] was to rescue ], who was arrested there, an act which also resulted in his own arrest and a ban from visiting the island for five years. Upon his next visit in June ], he met local Chinese merchants ], ] and ] in a meeting which was to mark the commencement of direct support from the Nanyang Chinese. Upon hearing their reports on overseas Chinese revolutionists organising themselves in ] and ], he urged them to establish the Singapore chapter of the ], which came officially into being on ] the following year upon his next visit. | |||

| {{Main|First United Front}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Sun was now convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period of {{ill|Outline of the Founding of the National Government|lt=political tutelage|zh|國民政府建國大綱}}, which would culminate in the transition to democracy. To hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active co-operation with the ] (CCP). Sun and the ]'s ] signed the ] in January 1923.<ref name="Tung1">Tung, William L. (1968). ''The political institutions of modern China''. Springer publishing. {{ISBN|978-9024705528}}. pp. 92, 106.</ref> Sun received help from the ] for his acceptance of communist members into his KMT. Sun received assistance from Soviet advisor ], whom Sun described as his "]".<ref name="Crean">{{Cite book |last=Crean |first=Jeffrey |title=The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History |date=2024 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-350-23394-2 |edition= |series=New Approaches to International History series |location=London, UK |pages=}}</ref>{{Rp|page=54}} The Russian revolutionary and socialist leader ] praised Sun and his KMT for its ideology, principles, attempts at social reformation, and fight against foreign imperialism.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=I2cSSVPogpoC&q=lenin+sun+principles+of+the+people&pg=PA22|title=Mao Tse-tung: Ruler of Red China|author=Robert Payne|year=2008|publisher=Read Books|page=22|isbn=978-1443725217|access-date=28 June 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vnOFYI3g-N4C&q=Lenin,+who+viewed+the+revolutionary+struggle+of+the+Chinese+people+with+great+sympathy,+had+a+high+regard+for+Sun+Yat-sen's+work+and+referred+to+him+as+%22a+revolutionary+democrat,+endowed+with+nobility+and+heroism%22|title=Great Soviet Encyclopedia|page=237|access-date=28 June 2010|year=1980|last1=Ross|first1=Harold Wallace|last2=White|first2=Katharine Sergeant Angell}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mF0NAQAAMAAJ&q=Lenin,+who+viewed+the+revolutionary+struggle+of+the+Chinese+people+with+great+sympathy,+had+a+high+regard+for+Sun+Yat-sen's+work+and+referred+to+him+as+%22a+revolutionary+democrat,+endowed+with+nobility+and+heroism%22&pg=PA237|title=Great Soviet encyclopedia, Volume 25|author=Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov|year=1982|publisher=Macmillan|access-date=28 June 2010}}</ref> Sun also returned the praise by calling Lenin a "great man" and indicated that he wished to follow the same path as Lenin.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lSVK8qxOsG8C&q=lenin+sun+principles+of+the+people&pg=PA170|title=Aunt Mae's China|author=Bernice A Verbyla|year=2010|publisher=Xulon Press|page=170|isbn=978-1609574567|access-date=28 June 2010}}</ref> In 1923, after having been in contact with Lenin and other Moscow communists, Sun sent representatives to study the ], and in turn, the Soviets sent representatives to help reorganize the KMT at Sun's request.<ref>{{cite book |title=M.N. Roy's Mission to China |publisher=University of California Press |pages=19–20}}</ref> | |||

| With the Soviets' help, Sun was able to develop the military power needed for the ] against the military at the north. He established the ] near Guangzhou with ] as the ] of the ] (NRA).<ref>Gao. James Zheng. (2009). ''Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949)''. Scarecrow press. {{ISBN|978-0810849303}}. p. 251.</ref> Other Whampoa leaders include ] and ] as political instructors. This full collaboration was called the ]. | |||

| The chapter was housed in a ] known as ] (晚晴园) and donated for the use of revolutionalists by Teo. In ], the chapter grew in membership to 400, and in ], when Sun was in Singapore to escape the Qing government in the wake of the failed ], the chapter had become the regional headquarters for Tongmenghui branches in ]. Sun and his followers travelled from Singapore to ] and Indonesia to spread their revolutionary message, by which time the alliance already had over twenty branches with over 3,000 members around the world. | |||

| === Financial concerns === | |||

| Sun's foresight in tapping on the help and resources of the overseas Chinese population was to bear fruit on his subsequent revolutionary efforts. In one particular instance, his personal plea for financial aid at the ] held on ] ] in ], helped launch a major drive for donations across the ], an effort which helped finance the ] (also commonly known as the ]) in 1911. | |||

| In 1924 Sun appointed his brother-in-law ] to set up the first Chinese central bank, the ].<ref>] (1990). '']''. ]. {{ISBN|978-0-393-30780-1}}. p. 345.</ref> To establish national capitalism and a banking system was a major objective for the KMT.<ref>Ji, Zhaojin. (2003). ''A history of modern Shanghai banking: the rise and decline of China's finance capitalism''. M.E. Sharpe Publishing. {{ISBN|978-0765610034}}. p. 165.</ref> However, Sun met opposition by the ] against him. | |||

| == Final years== | |||

| Today, Sun's legacy is remembered in Nanyang at Wan Qing Yuan, which has since been preserved and renamed as the ], and gazetted as a ] of Singapore on ] ]. | |||

| === Final speeches === | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| ] (seated next to him) in ], Japan in 1924]] | |||

| {{main|Names of Sun Yat-sen}} | |||

| In February 1923, Sun made a presentation to the ] in ] and declared that the corruption of China and the ] of Hong Kong had turned him into a revolutionary.<ref>Ho, Virgil K.Y. (2005). ''Understanding Canton: Rethinking Popular Culture in the Republican Period''. Oxford University Press. {{ISBN|0199282714}}</ref><ref>Carroll, John Mark. ''Edge of Empires:Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong''. Harvard University Press. {{ISBN|0674017013}}</ref> The same year, he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed his ] as the foundation of the country and the ] as the guideline for the political system and bureaucracy. Part of the speech was made into the ]. | |||

| On 10 November 1924, Sun traveled north to ] and delivered a speech to suggest a gathering for a "national conference" for the Chinese people. He called for the end of warlord rules and the abolition of all ] with the ].<ref>Ma Yuxin (2010). ''Women journalists and feminism in China, 1898–1937''. Cambria Press. {{ISBN|978-1604976601}}. p. 156.</ref> Two days later, he traveled to Beijing to discuss the future of the country despite his deteriorating health and the ongoing civil war of the warlords. Among the people whom he met was the Muslim warlord General ], who informed Sun that he would welcome Sun's leadership.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.elycn.com/gs/lx/015/003.htm |script-title=zh:马福祥,临夏回族自治州马福祥,马福祥介绍{{snd}}走遍中国|website=www.elycn.com|access-date=23 June 2017|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130513183437/http://www.elycn.com/gs/lx/015/003.htm|archive-date=13 May 2013}}</ref> On 28 November 1924 Sun traveled to Japan and gave a ] at ], Japan.<ref>Calder, Kent; Ye, Min (2010). ''The Making of Northeast Asia''. Stanford University Press. {{ISBN|978-0804769228}}.</ref> | |||

| Like many other Chinese historical figures, Sun Yat-sen used several names throughout his life, and he is known under several of these names, which can be quite confusing for the Westerner. Names, which are not taken lightly in ], are central to Chinese culture. This reverence goes as far back as ] and his insistence on using correct names. This can be confusing to foreigners. In addition to the names and ]es listed below, Sun also used many other aliases while he was a revolutionary in exile. According to one study, he used as many as thirty different names. | |||

| === Illness and death === | |||

| The "real" name of Sun Yat-sen (the concept of real or original name is not as clear-cut in China as it is in the Western world, as will become obvious below), the name inscribed in the genealogical records of his family, is '''Sun Deming''' (孫德明). This "]" is the name under which his extended relatives of the Sun family would have known him; and it was a name that was used on formal occasions, such as when he got married. | |||