| Revision as of 15:26, 26 October 2009 view sourceLawrencekhoo (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers29,834 edits Reverted to revision 321423399 by Ufim; This is about weight not sourcing. Find a reliable source that discuss economics and includes a discussion of thermoeconomics; otherwise it's fringe, and should not be included be← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:00, 21 January 2025 view source EvanBaldonado (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,823 editsm Replace hyphen with en-dash. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Social science}} | |||

| {{Otheruses4|the social science|textbook by Samuelson and Nordhaus|Economics (textbook)}} | |||

| {{ |

{{other uses}} | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef |

{{pp-semi-indef}} | ||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| ].|alt=A vegetable vendor in a marketplace.]] | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=August 2016}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=August 2016}} | |||

| {{CS1 config|mode=cs1}} | |||

| {{Economics sidebar|expanded=all}} | |||

| '''Economics''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|ɛ|k|ə|ˈ|n|ɒ|m|ᵻ|k|s|,_|ˌ|iː|k|ə|-}})<ref name="OED">{{Cite OED | term=economics |id=270555}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=ECONOMICS {{!}} Meaning & Definition for UK English |url=https://lexico.com/definition/economics |access-date=2024-04-13 |website=Lexico.com |archive-date=24 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220824032001/https://lexico.com/definition/economics |url-status=dead }}</ref> is a ] that studies the ], ], and ] of ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Krugman |first1=Paul |author-link=Paul Krugman |last2=Wells |first2=Robin |title=Economics |publisher=Worth Publishers |series= |volume= |edition=3rd |date=2012 |location= |page=2 |url= |doi= |id= |isbn=978-1464128738 |mr= |zbl= |jfm=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Backhouse |first=Roger |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/59475581 |title=The Penguin history of economics |date=2002 |isbn=0-14-026042-0 |oclc=59475581 |quote=The boundaries of what constitutes economics are further blurred by the fact that economic issues are analysed not only by 'economists' but also by historians, geographers, ecologists, management scientists, and engineers. |publisher=Penguin }}</ref> | |||

| Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of ] and how ] work. ] analyses what is viewed as basic elements within ], including individual agents and ], their interactions, and the outcomes of interactions. Individual agents may include, for example, households, firms, buyers, and sellers. ] analyses economies as systems where production, distribution, consumption, ], and ] interact, and factors affecting it: ], such as ], ], ], and ], ], ], and ] that have impact on ]. It also seeks to ]. | |||

| '''Economics''' is the ] that studies the ], ], and ] of ] and ]. The term ''economics'' comes from the ] ''{{lang|grc|]}}'' (''{{lang|grc-Latn|oikonomia}},'' "management of a household, administration") from ''{{lang|grc|]}}'' (''{{lang|grc-Latn|oikos}},'' "house") + ''{{lang|grc|]}}'' (''{{lang|grc-Latn|nomos}},'' "custom" or "law"), hence "rules of the house(hold)".<ref name="etymology">{{cite web | last = Harper | first = Douglas | authorlink = Douglas Harper | title = Online Etymology Dictionary — Economy | month = November | year = 2001 | url = http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=economy | dateformat = mdy | accessdate=October 27 2007}}</ref> Current economic models developed out of the broader field of ] in the late 19th century, owing to a desire to use an ] approach more akin to the physical sciences.<ref name="Clark">Clark, B. (1998). ''Political-economy: A comparative approach''. Westport, CT: Preager.</ref> | |||

| Other broad distinctions within economics include those between ], describing "what is", and ], advocating "what ought to be";<ref>{{cite book |last=Friedman |first=Milton |date=1953 |chapter=] |title=Essays in Positive Economics |publisher=University of Chicago Press |page=5}}</ref> between economic theory and ]; between ] and ]; and between ] and ].<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k2d8SFFyeNEC&pg=PP1 |title=The Foundations of Positive and Normative Economics: A Handbook |date=2008 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-532831-8 |editor-last=Caplin |editor-first=Andrew |editor-last2=Schotter |editor-first2=Andrew}}</ref> | |||

| A definition that captures much of modern economics is that of ] in a ]: "the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses."<ref>{{cite book | last = Robbins | first = Lionel | authorlink = Lionel Robbins | title = An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science | publisher = Macmillan and Co., Limited | year = 1945 | location = London | url = http://www.mises.org/books/robbinsessay2.pdf|format=PDF}}, p. 16</ref> ] means that available ] are insufficient to satisfy all wants and needs. Absent scarcity and alternative uses of available resources, there is no ]. The subject thus defined involves the study of ] as they are affected by incentives and resources.<!-- Robbins's (Brit.) spelling of "behaviour" preserved --> | |||

| Economic analysis can be applied throughout society, including ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dielman |first=Terry E. |title=Applied regression analysis for business and economics |date=2001 |publisher=Duxbury/Thomson Learning |isbn=0-534-37955-9 |oclc=44118027}}</ref> ], ],<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kianpour |first1=Mazaher |last2=Kowalski |first2=Stewart |last3=Øverby |first3=Harald |date=2021 |title=Systematically Understanding Cybersecurity Economics: A Survey |journal= Sustainability|volume= 13 |issue=24 |page=13677 |doi= 10.3390/su132413677|doi-access=free |hdl=11250/2978306 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Tarricone |first=Rosanna |date=2006 |title=Cost-of-illness analysis |journal=Health Policy |language=en |volume=77 |issue=1 |pages=51–63 |doi=10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.016 |pmid=16139925}}</ref> ]<ref name="Dharmaraj2010">{{Cite book |last=Dharmaraj |first=E. |title=Engineering Economics |location=Mumbai |publisher=Himalaya Publishing House |date=2010 |isbn=978-9350432471 |oclc=1058341272}} <!-- original citation mismatched publisher and year for 1st and 2nd(rev.) editions, so confirmation needed which is being cited --></ref> and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=King |first=David |title=Fiscal Tiers: the economics of multi-level government |date=2018 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-138-64813-5 |oclc=1020440881}}</ref> It is also applied to such diverse subjects as ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Becker |first=Gary S |date=January 1974 |chapter=Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach |title=Essays in the Economics of Crime and Punishment |editor-last1=Becker |editor-first1=Gary S. |editor-last2=Landes |editor-first2=William M. |pages=1–54 |publisher=] |isbn=0-87014-263-1 |chapter-url=https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c3625/c3625.pdf |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=13 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210913194049/https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c3625/c3625.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|date=2007 |title=Economics of Education |url=https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/7154 |publisher=] |last1=Hanushek |first1=Eric A. |last2=Woessmannr |first2=Ludger |series=Policy Research Working Papers |doi=10.1596/1813-9450-4122 |hdl=20.500.12323/2954 |s2cid=13912607 |access-date=17 December 2020 |archive-date=6 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220106142511/https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/7154 |url-status=live }}</ref> the ],<ref>{{Cite book |author-link=Gary Becker |last=Becker |first=Gary S. |orig-date=1981 |date=1991 |title=A Treatise on the Family |edition=Enlarged |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=0-674-90698-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NLB1Ty75DOIC |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730075050/https://books.google.com/books?id=NLB1Ty75DOIC |url-status=live }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite journal |author-link=Julie A. Nelson |last=Nelson |first=Julie A. |date=1995 |title=Feminism and Economics |journal=Journal of Economic Perspectives |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=131–148 |doi=10.1257/jep.9.2.131 |url=https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.9.2.131 |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=7 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220407203919/https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.9.2.131 |url-status=live }} | |||

| Economics aims to explain how ] work and how economic ] interact. Economic analysis is applied throughout society, in ], ] and ], but also in ],<ref>] (2002). ''The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.'' Accessed October 21, 2007. | |||

| {{Cite book |author-link=Marianne A. Ferber |editor-last1=Ferber |editor-first1=Marianne A. |editor-last2=Nelson |editor-first2=Julie A. |date=October 2003 |orig-date=1993 |title=Feminist Economics Today: Beyond Economic Man |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0226242071 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DeWgyqLvmfsC |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730075049/https://www.google.com/books/edition/Feminist_Economics_Today/DeWgyqLvmfsC |url-status=live }}</ref> ],<ref>{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| </ref> ],<ref>] (2007). Accessed October 21, 2007.</ref> the ], ], ], ], religion,<ref>Iannaccone, Laurence R. (1998). "Introduction to the Economics of Religion," ''Journal of Economic Literature'', 36(3), .</ref> ], war,<ref>] (2002). "The Economic Consequences of a War with Iraq", in ''War with Iraq: Costs, Consequences, and Alternatives'', American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Cambridge, MA. Accessed October 21, 2007.</ref> and ].<ref>Arthur M. Diamond, Jr. (2008). "science, economics of," '']'', 2nd Edition, Basingstoke and New York: ]. Pre-publication </ref> The expanding domain of economics in the ]s has been described as ].<ref name="Imperialism">] (2000|. "Economic Imperialism," ''Quarterly Journal Economics'', 115(1)|, p–146. (larger print.)</ref><ref>] (1976). ''The Economic Approach to Human Behavior''. to arrow-page viewable chapter. University of Chicago Press.</ref> | |||

| |1 = {{Cite book |author-link=Richard A. Posner |last=Posner |first=Richard A. |orig-date=1972 |date=2007 |title=Economic Analysis of Law |edition=7th |publisher=Wolters Kluwer – Aspen Publishers |isbn=978-0735563544 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ooFDAQAAIAAJ |access-date=2022-07-01 }} | |||

| |2 = {{Cite book |author-link=Richard A. Posner |last=Posner |first=Richard A. |date=1983 |title=The Economics of Justice |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0674235267 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CKEN0F07ChUC |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730075050/https://books.google.com/books?id=CKEN0F07ChUC |url-status=live }} | |||

| }}</ref> ],<ref>{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| |1 = {{Cite book |author-link=Adam Smith |last=Smith |first=Adam |orig-date=1759 |date=1982 |title-link=The Theory of Moral Sentiments |title=The Theory of Moral Sentiments |editor-last1=Raphael |editor-first1=D. D. |editor-last2=Macfie |editor-first2=A. L. |location=Indianapolis |publisher=Liberty Classics 1976 |isbn=978-0-86597-012-0}} . | |||

| |2 = {{Cite journal |author-link=Kenneth E. Boulding |last=Boulding |first=Kenneth E. |date=1969 |title=Economics as a Moral Science |journal=American Economic Review |volume=59 |issue=1 |pages=1–12 |jstor=1811088 |url=https://en-econ.tau.ac.il/sites/economy_en.tau.ac.il/files/media_server/Economics/grad/mini%20courses/David%20Colander/Boulding.pdf |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=5 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211005213945/https://en-econ.tau.ac.il/sites/economy_en.tau.ac.il/files/media_server/Economics/grad/mini%20courses/David%20Colander/Boulding.pdf |url-status=live }} | |||

| |3 = {{Cite book |author-link=Robert Heilbroner |last=Heilbroner |first=Robert L. |orig-date=1953 |date=1999 |edition=7th |title=The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times, and Ideas of the Great Economic Thinkers |publisher=Touchstone |isbn=0-684-86214-X |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vIxtW9cw-DQC |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730075050/https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Worldly_Philosophers/vIxtW9cw-DQC |url-status=live }} <!-- original cite mismatches gbooks url and isbn --> | |||

| |4 = {{Cite book |author-link=Amartya Sen |last=Sen |first=Amartya |date=2009 |title-link=The Idea of Justice |title=The Idea of Justice |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0674036130}} <!-- title wikilink conflicts with url=https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Idea_of_Justice/enqMd_ze6RMC --> <!-- original cite mismatches 2009 Harvard pub with 2011 Belknap pub --> }}</ref> ], ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Iannaccone |first=Laurence R. |author-link=Laurence R. Iannaccone |date=September 1998 |title=Introduction to the Economics of Religion |journal=Journal of Economic Literature |volume=36 |issue=3 |pages=1465–1495 |jstor=2564806 |url=https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/262957/mod_resource/content/2/Iannaccone%20-%20Economics%20of%20Religion.pdf |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=9 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200209225107/https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/262957/mod_resource/content/2/Iannaccone%20-%20Economics%20of%20Religion.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> ], ],<ref>{{Cite book |author-link=William D. Nordhaus |last=Nordhaus |first=William D. |title=War with Iraq: Costs, Consequences, and Alternatives |date=2002 |veditors=Kaysen C, Miller SE, Malin MB, Nordhaus WD, Steinbruner JD |publisher=American Academy of Arts and Sciences |isbn=978-0-87724-036-5 |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |pages=51–85 |chapter=The Economic Consequences of a War with Iraq |access-date=21 October 2007 |chapter-url=http://nordhaus.econ.yale.edu/AAAS_War_Iraq_2.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070202005510/http://nordhaus.econ.yale.edu/AAAS_War_Iraq_2.pdf |archive-date=2 February 2007}}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |last=Diamond | first=Arthur M. Jr. |chapter=Science, economics of |date=2008 |edition=2nd |pages=328–334 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.1491 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |dictionary=] |editor-last1=Durlauf |editor-first1=Steven N. |editor-last2=Blume |editor-first2=Lawrence E. |chapter-url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_E000222 <!--chapter-url throws error with archive-url --> |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170929232007/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_E000222 |archive-date=2017-09-29}} (Note the page is broken in some browsers but is still readable through the source.)</ref> and ].<ref>{{Cite report |title=Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication |date=2011 |publisher=] |url=https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/126GER_synthesis_en.pdf |access-date=2022-07-01 |archive-date=26 March 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170326154152/https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/126GER_synthesis_en.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Definitions of economics == | |||

| Common distinctions are drawn between various dimensions of economics: between ] (describing "what is") and ] (advocating "what ought to be") or between economic theory and ] or between ] (more "orthodox" dealing with the "rationality-individualism-equilibrium nexus") and ] (more "radical" dealing with the "institutions-history-social structure nexus"<ref>Davis, John B. (2006). "Heterodox Economics, the Fragmentation of the Mainstream, and Embedded Individual Analysis,” in ''Future Directions in Heterodox Economics''. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.</ref>). However the primary textbook distinction is between ] ("small" economics), which examines the economic behavior of agents (including individuals and firms) and ] ("big" economics), addressing issues of unemployment, inflation, monetary and fiscal policy for an entire economy. | |||

| {{anchor|The term and its various definitions€}} | |||

| {{main|Definitions of economics}} | |||

| The earlier term for the discipline was "political economy", but since the late 19th century, it has commonly been called "economics".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Backhouse |first=Roger |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/59475581 |title=The Penguin history of economics |date=2002 |isbn=0-14-026042-0 |pages=117 |publisher=Penguin Adult |oclc=59475581}}</ref> The term is ultimately derived from ] {{lang|grc|]}} (''oikonomia'') which is a term for the "way (nomos) to run a household (oikos)", or in other words the know-how of an {{lang|grc|οἰκονομικός}} (''oikonomikos''), or "household or homestead manager". Derived terms such as "economy" can therefore often mean "frugal" or "thrifty".<ref name="etymology">The terms derive ultimately from {{lang|grc|]}} (''{{lang|grc-Latn|oikos}}'' "house") and {{lang|grc|]}} (''{{lang|grc-Latn|nomos}}'', "custom" or "law"). {{Cite encyclopedia |last=Harper |first=Douglas |author-link=Douglas Harper |date=February 2007 |dictionary=Online Etymology Dictionary |title=Economy |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=economic |access-date=27 October 2007 |archive-date=12 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130512162853/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=economic |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Free2010">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hRFadIRMaMsC&pg=PA8 |title=21st Century Economics: A Reference Handbook |publisher=Sage Publications |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-4129-6142-4 |editor-last=Free |editor-first=Rhona C. |volume=1 |page=8}}</ref><ref name="MarshallMarshall1888">{{cite book |last1=Marshall |first1=Alfred |author-link1=Alfred Marshall |last2=Marshall |first2=Mary Paley |author-link2=Mary Paley Marshall |title=The Economics of Industry |url=https://archive.org/details/economicsindust00marsgoog |year=1888 |publisher=Macmillan |page=|orig-year=1879}}</ref><ref name="Jevons1879">{{cite book |last=Jevons |first=William Stanley |author-link=William Stanley Jevons |title=The Theory of Political Economy |url=https://archive.org/details/theorypolitical00jevogoog |edition=2nd |year=1879 |publisher=Macmillan and Co |page=XIV}}</ref> By extension then, "political economy" was the way to manage a ] or state. | |||

| There are a variety of modern ]; some reflect evolving views of the subject or different views among economists.<ref name="Backhouse">{{cite encyclopedia |author-link1=Roger E. Backhouse |last1=Backhouse |first1=Roger E. |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |pages=720–722 |first2=Steven |last2=Medema |date=2008 |edition=2nd|editor-first1=Steven N. |editor-last1=Durlauf |editor-first2=Lawrence E. |editor-last2=Blume |chapter-url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_E000291 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.0442 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |chapter=Economics, definition of |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |access-date=23 December 2011 |archive-date=5 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171005001939/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_E000291 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="BackhouseMedema2009">{{cite journal |last1=Backhouse |first1=Roger E. |first2=Steven |last2=Medema |date=Winter 2009 |title=Retrospectives: On the Definition of Economics |journal=] |volume=23 |issue=1 |pages=221–233 |jstor=27648302 |doi=10.1257/jep.23.1.221|doi-access=free }}</ref> ] philosopher ] (1776) defined what was then called ] as "an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations", in particular as: | |||

| {{Economics sidebar}} | |||

| {{blockquote|text=a branch of the science of a statesman or legislator a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people ... to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue for the publick services.<ref name="Groenwegen">{{cite book |last=Smith |first=Adam |author-link=Adam Smith |date=1776 |title=An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations|title-link=An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations }} and Book IV, as quoted in {{cite encyclopedia |first=Peter |last=Groenwegen |date=2008 |pages=476–480 |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |edition=2nd |editor-first1=Steven N. |editor-last1=Durlauf |editor-first2=Lawrence E. |editor-last2=Blume |chapter-url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_P000114 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.1300 |chapter=Political Economy |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |access-date=4 October 2017 |archive-date=5 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171005000524/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_P000114 |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| ==History of economic thought== | |||

| ]|alt=A stele depicting a man sitting down]] | |||

| {{Main|History of economic thought}} | |||

| ] (1803), distinguishing the subject matter from its ] uses, defined it as the science ''of'' production, distribution, and consumption of ].<ref name="Say1803">{{cite book|last=Say|first=Jean Baptiste|author-link=Jean-Baptiste Say|title=A Treatise on Political Economy|year=1803|publisher=Grigg and Elliot|title-link=Say's Political Economy}}</ref> On the ] side, ] (1849) coined "]" as an ] for ], in this context, commonly linked to the pessimistic analysis of ] (1798).<ref name="Dismal">{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| The ] of ] developed a trade and market ] based originally on the ] of the ] which was a certain weight measure of ], while the ] and their city state neighbors later developed the earliest system of economics using a ] of various ], that was fixed in a legal code.<ref>Kramer, ''History Begins at Sumer'', pp. 52–55.</ref> The early law codes from Sumer could be considered the first (written) economic formula, and had many attributes still in use in the current ] today... such as codified amounts of ] for business deals (interest rates), fines in money for 'wrong doing', inheritance rules, laws concerning how private property is to be taxed or divided, etc.<ref name="yale2">{{Cite web|url=http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/medieval/hammint.htm|title=The Code of Hammurabi : Introduction|accessdate=September 14 2007|dateformat=mdy|publisher=Yale University|year=1915|author=Charles F. Horne, Ph.D.}}</ref><ref>http://history-world.org/reforms_of_urukagina.htm</ref> For a summary of the laws, see ] and ]. | |||

| |1 = {{cite magazine |last=Carlyle |first=Thomas |author-link=Thomas Carlyle |date=1849 |title=Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question |magazine=] |title-link=Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question }} | |||

| |2 = {{cite book |last=Malthus |first=Thomas Robert |author-link=Thomas Robert Malthus |date=1798 |title=An Essay on the Principle of Population |publisher=J. Johnson |location=London|title-link=An Essay on the Principle of Population }} | |||

| |3 = {{cite journal |last=Persky |first=Joseph |date=Autumn 1990 |title=Retrospectives: A Dismal Romantic |journal=Journal of Economic Perspectives |volume=4 |issue=4 |pages=165–172 |jstor=1942728 |doi=10.1257/jep.4.4.165|doi-access= }} | |||

| }}</ref> ] (1844) delimited the subject matter further: | |||

| {{blockquote|text=The science which traces the laws of such of the phenomena of society as arise from the combined operations of mankind for the production of wealth, in so far as those phenomena are not modified by the pursuit of any other object.<ref>{{cite book|last=Mill|first=John Stuart|author-link=John Stuart Mill|title=Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4TxQqkP40fYC&pg=PA99|year=2007|publisher=Cosimo|isbn=978-1-60206-978-7|chapter=On the Definition of Political Economy; and on the Method of Investigation Proper to It|orig-year=1844|access-date=4 October 2017|archive-date=1 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801073208/https://books.google.com/books?id=4TxQqkP40fYC&pg=PA99|url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| Economic thought dates from earlier ]n, ], ], ], Chinese, ] and ] civilizations. Notable writers include ], ] (also known as Kautilya), ], ] and ] through to the 14th century. ] initially considered the ] of the 14th to 17th centuries as "coming nearer than any other group to being the 'founders' of scientific economics" as to monetary, interest, and value theory within a ] perspective.<ref>Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1954). ''History of Economic Analysis'', pp. 97–115. Oxford.</ref> After discovering Ibn Khaldun's '']'', however, Schumpeter later viewed Ibn Khaldun as being the closest forerunner of modern economics,<ref>I. M. Oweiss (1988), "Ibn Khaldun, the Father of Economics", ''Arab Civilization: Challenges and Responses'', ], ISBN 0887066984.</ref> as many of his economic theories were not known in Europe until relatively modern times.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Boulakia, Jean David C. |date=1971 |title=Ibn Khaldun: A Fourteenth-Century Economist |journal=The Journal of Political Economy |volume=79 |issue=5 |pages=1105–1118 }}</ref> | |||

| ] provided a still widely cited definition in his textbook '']'' (1890) that extended analysis beyond ] and from the ] to the ] level: | |||

| Nonetheless, recent research indicates that the Indian scholar-philosopher ] (c. 340-293 BCE) predates ] by a millennium and a half as the forerunner of modern economics,<ref>L. K. Jha, K. N. Jha (1998). "Chanakya: the pioneer economist of the world", ''International Journal of Social Economics'' 25(2–4): 267–282.</ref><ref>Waldauer, C., Zahka, W.J. and Pal, S. (1996) . ''Indian Economic Review'' Vol. 31(1): 101–108.</ref><ref>Tisdell, C. (2003) ''Economic Theory, Applications and Issues Working Paper No. 18''. Brisbane: School of Economics, The University of Queensland.</ref><ref>Sihag, B.S. (2007) Kautilya on institutions, governance, knowledge, ethics and prosperity. ''Humanomics'' 23 (1): 5–28.</ref> and has written more expansively on this subject, particularly on political economy. His magnum opus, the '']'' (''The Science of Wealth and Welfare''),<ref>Sihag, B.S. (2005) Kautilya on public goods and taxation. ''History of Political Economy'' 37 (4): 723–753.</ref> is the genesis of economic concepts that include the opportunity cost, the demand-supply framework, diminishing returns, marginal analysis, public goods, the distinction between the short run and the long run, asymmetric information and the producer surplus.<ref>Sihag, B.S. (2009) An introduction to Kautilya and his Arthashastra. ''Humanomics'' 25(1).</ref> In his capacity as an advisor to the throne of the ] of ancient ], he has also advised on the sources and prerequisites of economic growth, obstacles to it and on tax incentives to encourage economic growth.<ref>Sihag, B.S. (2007) Kautilya on institutions, governance, knowledge, ethics and prosperity. ''Humanomics'' 23(1): 5–28.</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|text=Economics is a study of man in the ordinary business of life. It enquires how he gets his income and how he uses it. Thus, it is on the one side, the study of wealth and on the other and more important side, a part of the study of man.<ref>{{cite book|last=Marshall|first=Alfred|author-link=Alfred Marshall|title=Principles of Economics|url=https://archive.org/details/principlesecono00marsgoog|year=1890|publisher=Macmillan and Company|pages=–2}}</ref>}} | |||

| ]|alt=A seaport with a ship arriving]] | |||

| ] (1932) developed implications of what has been termed "erhaps the most commonly accepted current definition of the subject":<ref name="BackhouseMedema2009"/> | |||

| Two other groups, later called 'mercantilists' and 'physiocrats', more directly influenced the subsequent development of the subject. Both groups were associated with the rise of ] and ] in Europe. ] was an economic doctrine that flourished from the 16th to 18th century in a prolific pamphlet literature, whether of merchants or statesmen. It held that a nation's wealth depended on its accumulation of gold and silver. Nations without access to mines could obtain gold and silver from trade only by selling goods abroad and restricting imports other than of gold and silver. The doctrine called for importing cheap raw materials to be used in manufacturing goods, which could be exported, and for state regulation to impose protective tariffs on foreign manufactured goods and prohibit manufacturing in the colonies.<ref>NA (2007). "mercantilism," {{cite book | title=The New Encyclopædia Britannica| date=| pages=v. 8, p. 26| publisher=| id=}}</ref><ref>Blaug, Mark (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics". ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica'', v. 27, p. 343.</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote |text=Economics is the science which studies ] as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.<ref>{{cite book|last=Robbins|first=Lionel|title=An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nySoIkOgWQ4C&pg=PA15|year=2007|orig-year=1932|publisher=Ludwig von Mises Institute|isbn=978-1-61016-039-1|page=15}}</ref>}} | |||

| ], a group of 18th century French thinkers and writers, developed the idea of the economy as a ] of income and output. ] described their system "with all its imperfections" as "perhaps the purest approximation to the truth that has yet been published" on the subject. Physiocrats believed that only agricultural production generated a clear surplus over cost, so that agriculture was the basis of all wealth. | |||

| Robbins described the definition as not ''classificatory'' in "pick out certain ''kinds'' of behaviour" but rather ''analytical'' in "focus attention on a particular ''aspect'' of behaviour, the form imposed by the influence of ]."{{sfnp|Robbins|2007|p=16}} He affirmed that previous economists have usually centred their studies on the analysis of wealth: how wealth is created (production), distributed, and consumed; and how wealth can grow.{{sfnp|Robbins|2007|pp=4–7}} But he said that economics can be used to study other things, such as war, that are outside its usual focus. This is because war has as the goal winning it (as a sought after ''end''), generates both cost and benefits; and, ''resources'' (human life and other costs) are used to attain the goal. If the war is not winnable or if the expected costs outweigh the benefits, the deciding ''actors'' (assuming they are rational) may never go to war (a ''decision'') but rather explore other alternatives. Economics cannot be defined as the science that studies wealth, war, crime, education, and any other field economic analysis can be applied to; but, as the science that studies a particular common aspect of each of those subjects (they all use scarce resources to attain a sought after end). | |||

| Thus, they opposed the mercantilist policy of promoting manufacturing and trade at the expense of agriculture, including import tariffs. Physiocrats advocated replacing administratively costly tax collections with a single tax on income of land owners. Variations on such a ] were taken up by subsequent economists (including ] a century later) as a relatively non-] source of tax revenue. In reaction against copious mercantilist trade regulations, the physiocrats advocated a policy of ], which called for minimal government intervention in the economy.<ref>NA (2007). "physiocrat," {{cite book | title=The New Encyclopædia Britannica| date=| pages=v. 9, p. 414.| publisher=| id=}}</ref><ref>Blaug, Mark (1997, 5th ed.) ''Economic Theory in Retrospect'', pp, 24–29, 82–84. Cambridge.</ref> | |||

| Some subsequent comments criticised the definition as overly broad in failing to limit its subject matter to analysis of markets. From the 1960s, however, such comments abated as the economic theory of maximizing behaviour and ] modelling ] of the subject to areas previously treated in other fields.<ref name="Backhouse2009Stigler">{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| ===Classical political economy=== | |||

| |1 = {{cite journal |last1=Backhouse |first1=Roger E. |first2=Steven G. |last2=Medema |date=October 2009 |title=Defining Economics: The Long Road to Acceptance of the Robbins Definition |journal=Economica |volume=76 |issue=s1 |pages=805–820 |doi=10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00789.x|s2cid=148506444 |doi-access=free }} | |||

| {{Main|Classical economics}} | |||

| |2 = {{cite journal |author-link=George J. Stigler |last=Stigler |first=George J. |date=1984 |title=Economics – The Imperial Science? |journal=Scandinavian Journal of Economics |volume=86 |issue=3 |pages=301–313 |jstor=3439864|doi=10.2307/3439864 }} | |||

| Publication of ]'s '']'' in 1776, has been described as "the effective birth of economics as a separate discipline."<ref name="Blaug">] (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics". ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica'', v. 27, p. 343.</ref> The book identified land, labor, and capital as the three factors of production and the major contributors to a nation's wealth. | |||

| }}</ref> There are other criticisms as well, such as in scarcity not accounting for the ] of high unemployment.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |author-link=Mark Blaug |last=Blaug |first=Mark |date=15 September 2017 |title=Economics |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/economics |access-date=4 October 2017 |archive-date=25 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220625153920/https://www.britannica.com/topic/economics |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ], a contributor to the expansion of economics into new areas, described the approach he favoured as "combin assumptions of maximizing behaviour, stable ], and ], used relentlessly and unflinchingly."<ref>{{cite book|last=Becker|first=Gary S.|title=The Economic Approach to Human Behavior|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iwEOFKSKbMgC&pg=PA5|year=1976|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-04112-4|page=5}}</ref> One commentary characterises the remark as making economics an approach rather than a subject matter but with great specificity as to the "choice process and the type of ] that analysis involves." The same source reviews a range of definitions included in principles of economics textbooks and concludes that the lack of agreement need not affect the subject-matter that the texts treat. Among economists more generally, it argues that a particular definition presented may reflect the direction toward which the author believes economics is evolving, or should evolve.<ref name=BackhouseMedema2009/> | |||

| ] wrote '']''|alt=A man facing the right]] | |||

| Many economists including nobel prize winners ] and ] reject the method-based definition of Robbins and continue to prefer definitions like those of Say, in terms of its subject matter.<ref name="Backhouse2009Stigler"/> ] has for example argued that the definition of Robbins would make economics very peculiar because all other sciences define themselves in terms of the area of inquiry or object of inquiry rather than the methodology. In the biology department, it is not said that all biology should be studied with DNA analysis. People study living organisms in many different ways, so some people will perform DNA analysis, others might analyse anatomy, and still others might build game theoretic models of animal behaviour. But they are all called biology because they all study living organisms. According to Ha Joon Chang, this view that the economy can and should be studied in only one way (for example by studying only rational choices), and going even one step further and basically redefining economics as a theory of everything, is peculiar.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ha-joon-chang-economics_n_5120030 |title=Ha-Joon Chang: Economics Is A Political Argument |author=Seung-Yoon Lee |date=4 September 2014 |website=huffpost.com |publisher=Huffington Post |access-date= |quote= |archive-date=19 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211019151027/https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ha-joon-chang-economics_n_5120030 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In Smith's view, the ideal economy is a self-regulating market system that automatically satisfies the economic needs of the populace. He described the market mechanism as an "invisible hand" that leads all individuals, in pursuit of their own self-interests, to produce the greatest benefit for society as a whole. Smith incorporated some of the Physiocrats' ideas, including laissez-faire, into his own economic theories, but rejected the idea that only agriculture was productive. | |||

| == History of economic thought == | |||

| {{Main|History of economic thought|History of macroeconomic thought}} | |||

| {{Missing information|section|information and behavioural economics, contemporary microeconomics|date=September 2020}} | |||

| === From antiquity through the physiocrats === | |||

| ]|alt=A seaport with a ship arriving]] | |||

| Questions regarding distribution of resources are found throughout the writings of the ]n poet ] and several economic historians have described Hesiod as the "first economist".<ref>{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| |1 = {{cite book|last=Gordan|first=Barry J.|title=Economic analysis before Adam Smith: Hesiod to Lessius|publisher=MacMillan|date=1975|page=3|isbn=978-1-349-02116-1|doi=10.1007/978-1-349-02116-1|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YReyCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA3}} | |||

| |2 = {{cite book|last=Brockway|first=George P.|title=The End of Economic Man: An Introduction to Humanistic Economics|edition=4th|date=2001|page=128|publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |isbn=978-0-393-05039-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i8ZhZFqUl7kC|access-date=18 September 2020|archive-date=14 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414142715/https://books.google.com/books?id=i8ZhZFqUl7kC|url-status=live}} | |||

| }}</ref> However, the word ], the Greek word from which the word economy derives, was used for issues regarding how to manage a household (which was understood to be the landowner, his family, and his slaves<ref>{{Cite book |last=Backhouse |first=Roger |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/59475581 |title=The Penguin history of economics |date=2002 |publisher=Penguin Adult |isbn=0-14-026042-0 |oclc=59475581 |access-date=3 June 2022 |archive-date=30 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730075150/https://www.worldcat.org/title/penguin-history-of-economics/oclc/59475581 |url-status=live }}</ref>) rather than to refer to some normative societal system of distribution of resources, which is a more recent phenomenon.<ref>Cameron, Gregory. (2008). Oikos and Economy: The Greek Legacy in Economic Thought.</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Oikos Meaning in Bible – New Testament Greek Lexicon – New American Standard|url=https://www.biblestudytools.com/lexicons/greek/nas/oikos.html|access-date=2021-11-19|website=biblestudytools.com|language=en|archive-date=19 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211119121115/https://www.biblestudytools.com/lexicons/greek/nas/oikos.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Jameson|first=Michael H.|date=2015-12-22|title=houses, Greek|url=https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-3169|access-date=2021-11-19|website=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics|language=en|doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.3169|isbn=978-0-19-938113-5|archive-date=19 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211119121120/https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-3169|url-status=live}}</ref> ], the author of the ], is credited by ] for being the source of the word economy.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lowry |first=S. Todd |title=Xenophons Oikonomikos, Über einen Klassiker der Haushaltsökonomie |publisher=Verlag Wirtschaft und Finanzen |year=1998 |isbn=3878811276 |location=] |pages=77 |language=de}}</ref> ] described 16th and 17th century ] writers, including ], ], and ], as "coming nearer than any other group to being the 'founders' of scientific economics" as to ], ], and ] theory within a ] perspective.<ref>{{cite book |last=Schumpeter |first=Joseph A. |date=1954 |title=History of Economic Analysis |publisher=Routledge |pages=97, 101, 112|isbn=978-0-415-10888-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pl4DABZfGREC&pg=PA97}}</ref> | |||

| Two groups, who later were called "mercantilists" and "physiocrats", more directly influenced the subsequent development of the subject. Both groups were associated with the rise of ] and ] in Europe. ] was an economic doctrine that flourished from the 16th to 18th century in a prolific pamphlet literature, whether of merchants or statesmen. It held that a nation's wealth depended on its accumulation of gold and silver. Nations without access to mines could obtain gold and silver from trade only by selling goods abroad and restricting imports other than of gold and silver. The doctrine called for importing inexpensive raw materials to be used in manufacturing goods, which could be exported, and for state regulation to impose protective ]s on foreign manufactured goods and prohibit manufacturing in the colonies.<ref>{{unbulleted list citebundle|{{cite encyclopedia |title=Mercantilism |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |date=26 August 2016 |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/mercantilism |access-date=24 October 2017 |archive-date=31 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171031160310/https://www.britannica.com/topic/mercantilism |url-status=live }}|{{harvp|Blaug|2017|page=343}}.}}</ref> | |||

| ], a group of 18th-century French thinkers and writers, developed the idea of the economy as a ] of income and output. Physiocrats believed that only agricultural production generated a clear surplus over cost, so that agriculture was the basis of all wealth.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bertholet|first=Auguste|date=2021|title=Constant, Sismondi et la Pologne|url=https://www.slatkine.com/fr/editions-slatkine/75250-book-05077807-3600120175625.html|journal=Annales Benjamin Constant|volume=46|pages=78–81|access-date=20 January 2022|archive-date=12 May 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512143530/https://www.slatkine.com/fr/editions-slatkine/75250-book-05077807-3600120175625.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Thus, they opposed the mercantilist policy of promoting manufacturing and trade at the expense of agriculture, including import tariffs. Physiocrats advocated replacing administratively costly tax collections with a single tax on income of land owners. In reaction against copious mercantilist trade regulations, the physiocrats advocated a policy of '']'',<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Bertholet |first1=Auguste |url=https://www.sgeaj.ch/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/bertholet-kapossy-la-physiocratie-et-la-suisse-2023.pdf |title=La Physiocratie et la Suisse |last2=Kapossy |first2=Béla |publisher=Slatkine |year=2023 |isbn=9782051029391 |location=Geneva |language=fr}}</ref> which called for minimal government intervention in the economy.<ref>{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| |1 = {{cite encyclopedia|title=Physiocrat|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online|date=7 March 2014|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/physiocrat|access-date=24 October 2017|archive-date=25 October 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171025023645/https://www.britannica.com/topic/physiocrat|url-status=live}} | |||

| |2 = {{cite book|last=Blaug|first=Mark|title=Economic Theory in Retrospect|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4nd6alor2goC&pg=PA24|edition=5th|year=1997|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-57701-4|pages=24–29, 82–84}} | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ] (1723–1790) was an early economic theorist.<ref>{{cite book|last=Hunt|first=E. K.|title=History of Economic Thought: A Critical Perspective|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=duYaugxYHdIC&pg=PA36|year=2002|publisher=M.E. Sharpe|isbn=978-0-7656-0606-8|page=36}}</ref> Smith was harshly critical of the mercantilists but described the physiocratic system "with all its imperfections" as "perhaps the purest approximation to the truth that has yet been published" on the subject.<ref>{{cite book|last=Skousen|first=Mark|title=The Making of Modern Economics: The Lives and Ideas of the Great Thinkers|url=https://archive.org/details/makingo_sko_2001_00_5649|url-access=registration|year=2001|publisher=M.E. Sharpe|isbn=978-0-7656-0479-8|page=}}</ref> | |||

| === Classical political economy === | |||

| {{Main|Classical economics}} | |||

| ]'s '']'' in 1776 is considered to be the first formalisation of economic thought.|alt=Picture of Adam Smith facing to the right]] | |||

| The publication of ]'s '']'' in 1776, has been described as "the effective birth of economics as a separate discipline."{{sfnp|Blaug|2017|p=343}} The book identified land, labour, and capital as the three factors of production and the major contributors to a nation's wealth, as distinct from the physiocratic idea that only agriculture was productive. | |||

| Smith discusses potential benefits of specialisation by ], including increased ] and ], whether between town and country or across countries.<ref>{{cite web |author-link=Alan Deardorff |last=Deardorff |first=Alan V. |date=2016 |title=Division of labor |website=Deardorffs' Glossary of International Economics |publisher=University of Michigan |url=http://www-personal.umich.edu/~alandear/glossary/d.html#DivisionOfLabor |access-date=1 March 2012 |archive-date=16 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200316082342/http://www-personal.umich.edu/~alandear/glossary/d.html#DivisionOfLabor |url-status=live }}</ref> His "theorem" that "the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market" has been described as the "core of a ] and ]" and a "fundamental principle of economic organization."<ref>{{cite journal |author-link=George J. Stigler |last=Stigler |first=George J. |date=June 1951 |title=The Division of Labor Is Limited by the Extent of the Market |journal=Journal of Political Economy |volume=59 |issue=3 |pages=185–193 |jstor=1826433 |url=https://www.sfu.ca/~allen/stigler.pdf |doi=10.1086/257075 |s2cid=36014630 |access-date=26 August 2017 |archive-date=25 August 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160825225559/http://www.sfu.ca/~allen/stigler.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> To Smith has also been ascribed "the most important substantive proposition in all of economics" and foundation of ] theory—that, under ], resource owners (of labour, land, and capital) seek their most profitable uses, resulting in an equal rate of return for all uses in ] (adjusted for apparent differences arising from such factors as training and unemployment).<ref>{{cite journal |last=Stigler |first=George J. |date=December 1976 |title=The Successes and Failures of Professor Smith |journal=Journal of Political Economy |volume=84 |issue=6 |pages=1199–1213 |jstor=1831274 |doi=10.1086/260508|s2cid=41691663 }} Also published as {{cite report |title=The Successes and Failures of Professor Smith |work=Selected Papers, No. 50 |url=http://testwww.chicagobooth.edu/research/selectedpapers/sp50c.pdf |publisher=Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago |date= |access-date=16 August 2010 |archive-date=25 August 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160825213630/http://testwww.chicagobooth.edu/research/selectedpapers/sp50c.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In his famous ] analogy, Smith argued for the seemingly ]ical notion that competitive markets tended to advance broader ''social'' interests, although driven by narrower ''self''-interest. The general approach that Smith helped initiate was called ] and later ]. It included such notables as ], ], and ] writing from about 1770 to 1870.<ref>Blaug, Mark (1987). "Classical Economics", ], v. 1, pp. 434–35. Blaug notes less widely used datings and uses of 'classical economics', including those of ] and ].</ref> | |||

| In an argument that includes "one of the most famous passages in all economics,"{{sfnp|Samuelson|Nordhaus|2010|p=30|loc=ch. 2, "Markets and Government in a Modern Economy", The Invisible Hand}} Smith represents every individual as trying to employ any capital they might command for their own advantage, not that of the society,{{efn|"Capital" in Smith's usage includes ] and ]. The latter includes wages and labour maintenance, money, and inputs from land, mines, and fisheries associated with production.{{sfn|Smith|1776|loc=Bk. II: ch. 1, 2, and 5}}}} and for the sake of profit, which is necessary at some level for employing capital in domestic industry, and positively related to the value of produce.{{sfnp|Smith|1776|loc=Bk. IV: Of Systems of political Œconomy, ch. II, "Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be Produced at Home", IV.2.3 para. 3–5 and 8–9}} In this: | |||

| While Adam Smith emphasized the production of income, David Ricardo focused on the distribution of income among landowners, workers, and capitalists. Ricardo saw an inherent conflict between landowners on the one hand and labor and capital on the other. He posited that the growth of population and capital, pressing against a fixed supply of land, pushes up rents and holds down wages and profits. | |||

| {{blockquote|He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.{{sfnp|Smith|1776|loc=Bk. IV: Of Systems of political Œconomy, ch. II, "Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be Produced at Home", para. 9}} }} | |||

| ] cautioned law makers on the effects of poverty reduction policies|alt=A man facing the viewer]] | |||

| Thomas Robert Malthus used the |

The ] ] (1798) used the concept of ] to explain low living standards. ], he argued, tended to increase geometrically, outstripping the production of food, which increased arithmetically. The force of a rapidly growing population against a limited amount of land meant diminishing returns to labour. The result, he claimed, was chronically low wages, which prevented the standard of living for most of the population from rising above the subsistence level.<ref>{{cite book |last=Malthus |first=Thomas |date=1798 |title=An Essay on the Principle of Population |publisher=J. Johnson Publisher|title-link=An Essay on the Principle of Population }}</ref>{{Primary source inline|date=November 2021}} Economist ] has criticised Malthus's conclusions.<ref>{{cite book|last=Simon|first=Julian Lincoln|title=The Ultimate Resource|year=1981|publisher=Princeton University Press|title-link=The Ultimate Resource}}; and {{cite book|last=Simon|first=Julian Lincoln|title=The Ultimate Resource 2|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wVyDwYqq5fMC&pg=PP1|year=1996|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-00381-8}}</ref> | ||

| While Adam Smith emphasised production and income, ] (1817) focused on the distribution of income among landowners, workers, and capitalists. Ricardo saw an inherent conflict between landowners on the one hand and labour and capital on the other. He posited that the growth of population and capital, pressing against a fixed supply of land, pushes up rents and holds down wages and profits. Ricardo was also the first to state and prove the principle of ], according to which each country should specialise in producing and exporting goods in that it has a lower ''relative'' cost of production, rather relying only on its own production.<ref>{{cite book |first=David |last=Ricardo |date=1817 |title=On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation |publisher=John Murray|title-link=On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation }}</ref> It has been termed a "fundamental analytical explanation" for ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|author-link=Ronald Findlay |first=Ronald |last=Findlay |date=2008 |edition=2nd |editor-first1=Steven N. |editor-last1=Durlauf |editor-first2=Lawrence E. |editor-last2=Blume |chapter-url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_C000254 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.0274 |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |pages=28–33 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |chapter=Comparative advantage |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |access-date=16 August 2010 |archive-date=11 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171011021521/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_C000254 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Malthus also questioned the automatic tendency of a ] to produce full employment. He blamed unemployment upon the economy's tendency to limit its spending by saving too much, a theme that lay forgotten until ] revived it in the 1930s. | |||

| Coming at the end of the |

Coming at the end of the classical tradition, ] (1848) parted company with the earlier classical economists on the inevitability of the distribution of income produced by the market system. Mill pointed to a distinct difference between the market's two roles: allocation of resources and distribution of income. The market might be efficient in allocating resources but not in distributing income, he wrote, making it necessary for society to intervene.<ref>{{cite book |last=Mill |first=John Stuart |date=1848 |title=Principles of Political Economy |publisher=John W. Parker Publisher|title-link=Principles of Political Economy }}</ref> | ||

| Value theory was important in classical theory. Smith wrote that the "real price of every thing |

Value theory was important in classical theory. Smith wrote that the "real price of every thing ... is the toil and trouble of acquiring it". Smith maintained that, with rent and profit, other costs besides wages also enter the price of a commodity.{{sfnp|Smith|1776|loc=Bk. 1, Ch. 5, 6}} Other classical economists presented variations on Smith, termed the ']'. Classical economics focused on the tendency of any market economy to settle in a ]. | ||

| === |

=== Marxian economics === | ||

| {{Main|Marxian economics}} | {{Main|Marxian economics}} | ||

| ].|alt= |

] ] comes from the work of German philosopher ].|alt=Photograph of Karl Marx facing the viewer]] | ||

| Marxist (later, Marxian) economics descends from classical economics and it derives from the work of ]. The first volume of Marx's major work, {{lang|de|]}}, was published in 1867. Marx focused on the ] and ]. Marx wrote that they were mechanisms used by capital to exploit labour.<ref name="Roemer">{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| |1 = {{cite encyclopedia |author-link=John Roemer |last=Roemer |first=J. E. |date=1987 |dictionary=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |editor-first1=John |editor-last1=Eatwell |editor-first2=Murray |editor-last2=Milgate |editor-first3=Peter |editor-last3=Newman |chapter-url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001420 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.3052 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |chapter=Marxian value analysis |pages=1–6 |access-date=19 October 2017 |archive-date=20 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171020033131/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001420 |url-status=live }} | |||

| |2 = {{cite encyclopedia |author-link=Ernest Mandel |last=Mandel |first=Ernest |date=1987 |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |editor-first1=John |editor-last1=Eatwell |editor-first2=Murray |editor-last2=Milgate |editor-first3=Peter |editor-last3=Newman |pages=372, 376 |url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001419 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.3051 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |chapter=Marx, Karl Heinrich (1818–1883) |access-date=19 October 2017 |archive-date=20 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171020032814/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001419 |url-status=live }} | |||

| }}</ref> The labour theory of value held that the value of an exchanged commodity was determined by the labour that went into its production, and the theory of surplus value demonstrated how workers were only paid a proportion of the value their work had created.<ref name="THOMAS FULLER">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/18/world/asia/18laos.html|work=The New York Times|first=Thomas|last=Fuller|title=Communism and Capitalism Are Mixing in Laos|date=17 September 2009|access-date=24 February 2017|archive-date=22 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170222010636/http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/18/world/asia/18laos.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Marxian economics was further developed by ] (1854–1938)'s ''The Economic Doctrines of Karl Marx'' and '']'', ]'s (1877–1941) '']'', ] (1870–1924)'s '']'' and '']'', and ] (1871–1919)'s '']''. | |||

| Marxist (later, Marxian) economics descends from classical economics. It derives from the work of ]. The first volume of Marx's major work, '']'', was published in German in 1867. In it, Marx focused on the ] and what he considered to be the exploitation of labour by capital.<ref name="Roemer"> ] (1987). "Marxian Value Analysis". '']'', v. 3, 383.</ref><ref>] (1987). "Marx, Karl Heinrich", ''The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economicsv. 3, pp. 372, 376.</ref> The labour theory of value held that the value of a thing was determined by the labor that went into its production. This contrasts with the modern understanding that the value of a thing is determined by what one is willing to give up to obtain the thing. | |||

| ===Neoclassical economics=== | === Neoclassical economics === | ||

| {{Main|Neoclassical economics}} | {{Main|Neoclassical economics}} | ||

| A body of theory later termed 'neoclassical economics' or ']' formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term 'economics' was popularized by such neoclassical economists as ] as a concise synonym for 'economic science' and a substitute for the earlier, broader term ']'.<ref> | |||

| Marshall, Alfred, and Mary Paley Marshall (1879). '' p. 2. </ref><ref>] (1879, 2nd ed.) p. xiv.</ref> This corresponded to the influence on the subject of mathematical methods used in the ]s.<ref name="Clark">Clark, B. (1998). ''Political-economy: A comparative approach'', 2nd ed., Westport, CT: Preagerp. p. 32..</ref> | |||

| At its inception as a social science, ''economics'' was defined and discussed at length as the study of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth by Jean-Baptiste Say in his ''Treatise on Political Economy or, The Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Wealth'' (1803). These three items were considered only in relation to the increase or diminution of wealth, and not in reference to their processes of execution.{{efn|"This science indicates the cases in which commerce is truly productive, where whatever is gained by one is lost by another, and where it is profitable to all; it also teaches us to appreciate its several processes, but simply in their results, at which it stops. Besides this knowledge, the merchant must also understand the processes of his art. He must be acquainted with the commodities in which he deals, their qualities and defects, the countries from which they are derived, their markets, the means of their transportation, the values to be given for them in exchange, and the method of keeping accounts. The same remark is applicable to the agriculturist, to the manufacturer, and to the practical man of business; to acquire a thorough knowledge of the causes and consequences of each phenomenon, the study of political economy is essentially necessary to them all; and to become expert in his particular pursuit, each one must add thereto a knowledge of its processes." {{harv|Say|1803|page=XVI}} }} Say's definition has survived in part up to the present, modified by substituting the word "wealth" for "goods and services" meaning that wealth may include non-material objects as well. One hundred and thirty years later, ] noticed that this definition no longer sufficed,{{efn|"And when we submit the definition in question to this test, it is seen to possess deficiencies which, so far from being marginal and subsidiary, amount to nothing less than a complete failure to exhibit either the scope or the significance of the most central generalisations of all." {{harv|Robbins|2007|p=5}} }} because many economists were making theoretical and philosophical inroads in other areas of human activity. In his '']'', he proposed a definition of economics as a study of human behaviour, subject to and constrained by scarcity,{{efn|"The conception we have adopted may be described as analytical. It does not attempt to pick out certain kinds of behaviour, but focuses attention on a particular aspect of behaviour, the form imposed by the influence of scarcity. {{harv|Robbins|2007|p=17}} }} which forces people to choose, allocate scarce resources to competing ends, and economise (seeking the greatest welfare while avoiding the wasting of scarce resources). According to Robbins: "Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses".{{sfnp|Robbins|2007|p=16}} Robbins' definition eventually became widely accepted by mainstream economists, and found its way into current textbooks.<ref>{{cite conference |title=Defining Economics: the Long Road to Acceptance of the Robbins Definition |first1=Roger E. |last1=Backhouse |first2=Steven G. |last2=Medema |work=Lionel Robbins's essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science, 75th anniversary conference proceedings |date=10 December 2007 |pages=209–230 |url=http://darp.lse.ac.uk/papersdb/LionelRobbinsConferenceProveedingsVolume.pdf#page=213 |conference= |access-date=30 July 2014 |archive-date=4 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304060656/http://darp.lse.ac.uk/papersdb/LionelRobbinsConferenceProveedingsVolume.pdf#page=213 |url-status=live }} also published in {{cite journal |title=Defining Economics: The Long Road to Acceptance of the Robbins Definition |journal=Economica |date=October 2009 |volume=76 |issue=Supplement 1 |pages=805–820 |jstor=40268907 |doi=10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00789.x|last1=Backhouse |first1=Roger E |last2=Medema |first2=Steve G |s2cid=148506444 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Although far from unanimous, most mainstream economists would accept some version of Robbins' definition, even though many have raised serious objections to the scope and method of economics, emanating from that definition.{{sfnp|Backhouse|Medema|2007|page=223|ps=: "There remained division over whether economics was defined by a method or a subject matter but both sides in that debate could increasingly accept some version of the Robbins definition."}} | |||

| Neoclassical economics systematized ] as joint determinants of price and quantity in market equilibrium, affecting both the allocation of output and the distribution of income. It dispensed with the ] inherited from classical economics in favor of a ] theory of value on the demand side and a more general theory of costs on the supply side.<ref name=>Campos, Antonietta (1987). "Marginalist Economics", ''The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics'', v. 3, p. 320</ref> | |||

| A body of theory later termed "neoclassical economics" formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term "economics" was popularised by such neoclassical economists as ] and ] as a concise synonym for "economic science" and a substitute for the earlier "]".<ref name="MarshallMarshall1888" /><ref name="Jevons1879"/> This corresponded to the influence on the subject of mathematical methods used in the ]s.<ref name="Clark">{{cite book |last=Clark |first=Barry |title=Political Economy: A Comparative Approach |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3wpiDzS45PsC&pg=PP1 |edition=2nd |year=1998 |publisher=Praeger |isbn=978-0-275-95869-5}}</ref> | |||

| In ], neoclassical economics represents incentives and costs as playing a pervasive role in shaping ]. An immediate example of this is the ] of individual demand, which isolates how prices (as costs) and income affect quantity demanded. In ] it is reflected in an early and lasting ] with Keynesian macroeconomics.<ref>] (1937). "Mr. Keynes and the 'Classics': A Suggested Interpretation," ''Econometrica'', 5(2), p.</ref><ref>Blanchard, Olivier Jean (1987). "Neoclassical Synthesis", ''The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics'', v. 3, pp. 634–36.</ref> | |||

| Neoclassical economics systematically integrated ] as joint determinants of both price and quantity in market equilibrium, influencing the allocation of output and income distribution. It rejected the classical economics' ] in favour of a ] theory of value on the demand side and a more comprehensive theory of costs on the supply side.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |chapter=Marginalist economics |chapter-url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001393 |access-date=27 October 2017 |last=Campus |first=Antonietta |date=1987 |editor-last1=Eatwell |editor-first1=John |edition=first |volume=III |pages=1–6 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.3031 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171027231849/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001393 |archive-date=27 October 2017 |dictionary=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |editor-first2=Murray |editor-last2=Milgate |editor-first3=Peter |editor-last3=Newman |url-status=live}}</ref> In the 20th century, neoclassical theorists departed from an earlier idea that suggested measuring total utility for a society, opting instead for ], which posits behaviour-based relations across individuals.<ref name="Hicks" /><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |access-date=27 October 2017 |last=Black |first=R.D. Collison |date=2008 |editor-last1=Durlauf |editor-first1=Steven N. |edition=2nd |pages=577–581 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.1781 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171028042451/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_U000047 |archive-date=28 October 2017 |editor-first2=Lawrence E. |editor-last2=Blume |chapter-url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_U000047 |chapter=Utility |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Neoclassical economics is occasionally referred as ''orthodox economics'' whether by its critics or sympathizers. Modern ] builds on neoclassical economics but with many refinements that either supplement or generalize earlier analysis, such as ], ], analysis of ] and ], and the ] of ] for analyzing long-run variables affecting ]. | |||

| In ], neoclassical economics represents incentives and costs as playing a pervasive role in shaping ]. An immediate example of this is the ] of individual demand, which isolates how prices (as costs) and income affect quantity demanded.<ref name="Hicks"/> In ] it is reflected in an early and lasting ] with Keynesian macroeconomics.<ref name="Blanchard2008"/><ref name="Hicks">{{cite journal |author-link=John Hicks |last=Hicks |first=J.R. |date=April 1937 |title=Mr. Keynes and the "Classics": A Suggested Interpretation |journal=Econometrica |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=147–159 |jstor=1907242 |doi=10.2307/1907242 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Keynesian economics=== | |||

| {{Main|Keynesian economics|Post-Keynesian economics|}} | |||

| ] (above, right), widely considered a towering figure in economics.|alt=Two men in suits converse with each other]] | |||

| Neoclassical economics is occasionally referred as ''orthodox economics'' whether by its critics or sympathisers. Modern ] builds on neoclassical economics but with many refinements that either supplement or generalise earlier analysis, such as ], ], analysis of ] and ], and the ] of ] for analysing long-run variables affecting ]. | |||

| Keynesian economics derives from ], in particular his book '']'' (1936), which ushered in contemporary ] as a distinct field.<ref>{{cite book |last=Keynes |first=John Maynard |title=] |publisher= Macmillan|year=1936 |location=London |isbn=1-57392-139-4 }}</ref><ref>Blaug, Mark (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics," ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica'', v. 27, p. 347. Chicago.</ref> The book focused on determinants of national income in the short run when prices are relatively inflexible. Keynes attempted to explain in broad theoretical detail why high labour-market unemployment might not be self-correcting due to low "]" and why even price flexibility and monetary policy might be unavailing. Such terms as "revolutionary" have been applied to the book in its impact on economic analysis.<ref>Tarshis, L. (1987). "Keynesian Revolution", ''The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics'', v. 3, pp. 47–50.</ref><ref>Samuelson, Paul A., and William D. Nordhaus (2004). '']'', p. 5.</ref><ref>Blaug, Mark (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics," ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica'', v. 27, p. 346. Chicago.</ref> | |||

| Neoclassical economics studies the behaviour of ]s, ]s, and ]s (called economic actors, players, or agents), when they manage or use ] resources, which have alternative uses, to achieve desired ends. Agents are assumed to act rationally, have multiple desirable ends in sight, limited resources to obtain these ends, a set of stable preferences, a definite overall guiding objective, and the capability of making a choice. There exists an economic problem, subject to study by economic science, when a ] (choice) is made by one or more players to attain the best possible outcome.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Leigh |last=Tesfatsion |title=Agent-Based Computational Economics: Growing Economies from the Bottom Up |journal=] |date=Winter 2002 |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=55–82 |url=https://www2.econ.iastate.edu/tesfatsi/acealife.pdf |pmid=12020421 |doi=10.1162/106454602753694765 |citeseerx=10.1.1.194.4605 |s2cid=1345062 |access-date=24 June 2020 |archive-date=26 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201126182912/https://www2.econ.iastate.edu/tesfatsi/acealife.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Keynesian economics has two successors. ] also concentrates on macroeconomic rigidities and adjustment processes. Research on micro foundations for their models is represented as based on real-life practices rather than simple optimizing models. It is generally associated with the ] and the work of ].<ref>Harcourt, G.C.(1987). "Post-Keynesian Economics", ''The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics'', v. 3, pp. 47–50.</ref> | |||

| === Keynesian economics === | |||

| ] is also associated with developments in the Keynesian fashion. Within this group researchers tend to share with other economists the emphasis on models employing micro foundations and optimizing behavior but with a narrower focus on standard Keynesian themes such as price and wage rigidity. These are usually made to be endogenous features of the models, rather than simply assumed as in older Keynesian-style ones. | |||

| {{Main|Keynesian economics}} | |||

| ], a key economics theorist]] | |||

| Keynesian economics derives from ], in particular his book '']'' (1936), which ushered in contemporary ] as a distinct field.<ref>{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| |1 = {{cite book |last=Keynes |first=John Maynard |title=The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money |publisher= Macmillan|year=1936 |location=London |isbn=978-1-57392-139-8 |title-link=The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money }} | |||

| |2 = {{harvp|Blaug|2017|p=347}} | |||

| }}</ref> The book focused on determinants of national income in the short run when prices are relatively inflexible. Keynes attempted to explain in broad theoretical detail why high labour-market unemployment might not be self-correcting due to low "]" and why even price flexibility and monetary policy might be unavailing. The term "revolutionary" has been applied to the book in its impact on economic analysis.<ref>{{unbulleted list citebundle | |||

| |1 = {{cite encyclopedia |last=Tarshis |first=L. |author-link=Lorie Tarshis |date=1987 |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |edition= |editor-first1=John |editor-last1=Eatwell |editor-first2=Murray |editor-last2=Milgate |editor-first3=Peter |editor-last3=Newman |volume=III |pages=47–50 |url=http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001226 |doi=10.1057/9780230226203.2888 |isbn=978-0-333-78676-5 |chapter=Keynesian Revolution |access-date=27 October 2017 |archive-date=28 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171028042612/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde1987_X001226 |url-status=live |doi-access=free }} | |||

| |2 = {{harvp|Samuelson|Nordhaus|2010|p=5}} | |||

| |3 = {{harvp|Blaug|2017|p=346}} | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| During the following decades, many economists followed Keynes' ideas and expanded on his works. ] and ] developed the ] which was a simple formalisation of some of Keynes' insights on the economy's short-run equilibrium. ] and ] developed important theories of ] and ], respectively, two major components of ]. ] built the first ], applying the Keynesian thinking systematically to the ].<ref>Blanchard et al. (2017), p. 510.</ref> | |||

| ===Chicago School of economics=== | |||

| {{Main|Chicago school (economics)}} | |||

| The Chicago School of economics is best known for its free market advocacy and ] ideas. According to ] and monetarists, market economies are inherently stable ] and depressions result only from government intervention.<ref>{{cite book|title=Macroeconomics and New Macroeconomics|author=Felderer, Bernhard}}</ref> Friedman, for example, argued that the Great Depression was result of a contraction of the money supply, controlled by the ], and not by the lack of investment as Keynes had argued. ], current Chairman of the Federal Reserve, is among the economists today generally accepting Friedman's analysis of the causes of the Great Depression.<ref name="fed">{{cite web|url=http://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2002/20021108/default.htm|title=Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke |publisher=The Federal Reserve Board|accessdate=2008-02-26|date=2002-11-08|author=Ben Bernanke}}</ref> | |||

| === Post-WWII economics === | |||

| Milton Friedman effectively took many of the basic principles set forth by ] and the classical economists and modernized them. One example of this is his article in the September 1970 issue of The New York Times Magazine, where he claims that the social responsibility of business should be “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits...(through) open and free competition without deception or fraud.” <ref>Friedman, Milton. "The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits." The New York Times Magazine 13 Sep. 1970.</ref> | |||

| Immediately after World War II, Keynesian was the dominant economic view of the United States establishment and its allies, Marxian economics was the dominant economic view of the Soviet Union nomenklatura and its allies. | |||

| ===Other schools and approaches=== | |||

| {{Main|Schools of economics}} | |||

| Other well-known schools or trends of thought referring to a particular style of economics practiced at and disseminated from well-defined groups of academicians that have become known worldwide, include the ], the ], the ], ] and the ]. Contemporary ] is sometimes separated into the Saltwater approach of those universities along the ] and ] coasts of the US, and the Freshwater, or Chicago-school approach. | |||

| ==== Monetarism ==== | |||

| Within macroeconomics there is, in general order of their appearance in the literature; ], ], the neoclassical synthesis, ], ], ], and ]. Alternative developments include ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| {{Main|Monetarism}} | |||

| Monetarism appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, its intellectual leader being ]. Monetarists contended that monetary policy and other monetary shocks, as represented by the growth in the money stock, was an important cause of economic fluctuations, and consequently that monetary policy was more important than fiscal policy for ].<ref>Blanchard et al. (2017), p. 511.</ref><ref name="fed">{{cite web|url=http://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2002/20021108/default.htm|title=Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke|publisher=The Federal Reserve Board|date=8 November 2002|first=Ben|last=Bernanke|access-date=22 February 2009|archive-date=24 March 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200324160935/https://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2002/20021108/default.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> Friedman was also skeptical about the ability of central banks to conduct a sensible active monetary policy in practice, advocating instead using simple rules such as a steady rate of money growth.<ref>Blanchard et al. (2017), p. 512.</ref> | |||

| ==Microeconomics== | |||

| {{Main|Microeconomics}} | |||

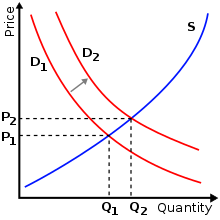

| Microeconomics looks at interactions through individual markets, given scarcity and ]. A given market might be for a ''product'', say fresh corn, or the ''services of a ]'', say bricklaying. The theory considers ] of ''quantity demanded'' by buyers and ''quantity supplied'' by sellers at each possible price per unit. It weaves these together to describe how the market may reach equilibrium as to price and quantity or respond to market changes over time. | |||

| Monetarism rose to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s, when several major central banks followed a monetarist-inspired policy, but was later abandoned because the results were unsatisfactory.<ref>Blanchard et al. (2017), p. 483–484.</ref><ref name="Historical">{{cite web |title=Federal Reserve Board - Historical Approaches to Monetary Policy |url=https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/historical-approaches-to-monetary-policy.htm |website=Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |access-date=29 October 2023 |language=en |date=8 March 2018}}</ref> | |||