| Revision as of 06:24, 25 February 2010 view sourceGeoffrie (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users553 editsm →Nordic countries← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:23, 14 January 2025 view source Gonnym (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Template editors227,269 edits →Etymology: replace template per TfD; general fixesTag: AWB | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Christian commemoration of the resurrection of Jesus}} | |||

| {{For|other uses|Easter (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{About|the Christian and cultural festival}} | |||

| {{Infobox Holiday | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| |holiday_name=Easter | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| |image=Resurrection (24).jpg | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2023}} | |||

| |caption=Icon of the ] of ] ], which is the usual Orthodox icon for Pascha. | |||

| {{Infobox holiday | |||

| |observedby=]s | |||

| | holiday_name = Easter | |||

| |date2010=April 4 (both Western and Eastern) | |||

| | image = File:Chora Anastasis2.jpg | |||

| |date2011=April 24 (both Western and Eastern) | |||

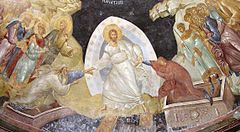

| | caption = Having ], ] is depicted flanked by saints, raising ] and ] from their graves and trampling ]. ] of the ] at ] ({{circa|1315}}) | |||

| |observances=], all-night vigil, sunrise service | |||

| | observedby = ] | |||

| |celebrations=Religious (church) services, festive family meals, ] hunts and gift-giving | |||

| | date = Variable, determined by the ] | |||

| |type=Christian | |||

| | date{{LASTYEAR}} = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| |significance=Celebrates the resurrection of ] | |||

| |relatedto=], of which it is regarded the Christian equivalent; ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] which lead up to Easter; and ], ], ], and ] which follow it. | |||

| }}{{portal|Christianity}} | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter |format=infobox |year={{LASTYEAR}}}} (Western) | |||

| '''Easter''' ({{lang-el|Πάσχα}} ''Paskha'', from ]: פֶּסַח ''Pesakh,'') is the most important annual religious feast in the ] ].<ref>Anthony Aveni, "The Easter/Passover Season: Connecting Time's Broken Circle," ''The Book of the Year: A Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 64-78.</ref> According to Christian scripture, ] was ] from the dead on the third day after his ]. Some Christians celebrate this resurrection on '''Easter Day''' or '''Easter Sunday'''<ref>'Easter Day' is the traditional name in English for the principal feast of Easter, used (for instance) by the '']'', but in the 20th century 'Easter Sunday' became widely used, despite this term also referring to the following Sunday.</ref> (also '''Resurrection Day''' or '''Resurrection Sunday'''), two days after ] and three days after ]. The ] of his death and resurrection is variously interpreted to be between ] 26 and AD 36. | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter (Eastern) |format=infobox |year={{LASTYEAR}}}} (Eastern) }} | |||

| Easter also refers to the ] of the church year called ] or the ]. Traditionally the Easter Season lasted for the forty days from Easter Day until ] Day but now officially lasts for the fifty days until ]. The first week of the Easter Season is known as Easter Week or the ]. Easter also marks the end of ], a season of fasting, prayer, and penance. | |||

| | date{{CURRENTYEAR}} = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter |format=infobox |year={{CURRENTYEAR}} |cite=y}} (Western) | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter (Eastern) |format=infobox |year={{CURRENTYEAR}} |cite=y}} (Eastern) }} | |||

| | date{{NEXTYEAR}} = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter |format=infobox |year={{NEXTYEAR}}}} (Western) | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter (Eastern) |format=infobox |year={{NEXTYEAR}}}} (Eastern) }} | |||

| | date{{NEXTYEAR|2}} = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter |format=infobox |year={{NEXTYEAR|2}}}} (Western) | |||

| | {{Calendar date |holiday=Easter (Eastern) |format=infobox |year={{NEXTYEAR|2}}}} (Eastern) }} | |||

| | observances = ], ], ] | |||

| | celebrations = ]s, festive family meals, ] decoration, and gift-giving | |||

| | significance = Celebrates the ] | |||

| | relatedto = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] which lead up to Easter; and ], ], ], ], ], and ], which follow it. | |||

| | type = Christian | |||

| | longtype = Religious, cultural | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Easter''',{{refn|1=Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '']''; "Easter Sunday", used by ] (<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Ussher |first1=James |last2=Elrington |first2=Charles Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P_82AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA345 |title=The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher – James Ussher, Charles Richard Elrington – Google Books |access-date=28 March 2023 |archive-date=1 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801065939/https://books.google.com/books?id=P_82AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA345 |url-status=live |date=1631 }}</ref>) and ] (<ref>{{Cite book |last=Pepys |first=Samuel |date=1665 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VxA5AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA585 |title=The Diary of Samuel Pepys M.A. F.R.S. |access-date=7 April 2023 |archive-date=9 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230409153747/https://books.google.com/books?id=VxA5AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA585 |url-status=live }}</ref>), as well as the single word "Easter" in books printed in ,<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gMNXPgAACAAJ |title=A Sermon of Christ Crucified, Preached at Paules Crosse the Fridaie Before ... |access-date=20 June 2015 |last=Foxe |first=John |date=1575 |archive-date=9 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230409153747/https://books.google.com/books?id=gMNXPgAACAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> ,<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-gEIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA15 |title=The Historie of Cambria |access-date=20 June 2015 |author=Caradoc (St. of Llancarfan) |date=1584 |archive-date=9 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230409153748/https://books.google.com/books?id=-gEIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA15 |url-status=live }}</ref> and .<ref>{{Cite web |last=(de Granada) |first=Luis |title=A Memoriall of a Christian Life: Wherein are Treated All Such Thinges, as ... |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O2M9AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA183 |access-date=20 June 2015 |date=1586 |archive-date=9 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230409153811/https://books.google.com/books?id=O2M9AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA183 |url-status=live }}</ref>|group="nb"}} also called '''Pascha'''{{refn|1=In the ], the Greek word ''Pascha'' is used for the celebration; in English, the analogous word is Pasch.<ref name="Ferguson2009">{{cite book |last=Ferguson |first=Everett |title=Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xC9GAdUGX5sC&pg=PA351 |access-date=23 April 2014 |date=2009 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing |isbn=978-0802827487 |page=351 |quote=The practices are usually interpreted in terms of baptism at the pasch (Easter), for which compare Tertullian, but the text does not specify this season, only that it was done on Sunday, and the instructions may apply to whenever the baptism was to be performed. |archive-date=1 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801082126/https://books.google.com/books?id=xC9GAdUGX5sC&pg=PA351 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Etymology">{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/europehistory00norm|url-access=registration|page=|title = Europe: A History|first=Norman |last=Davies|publisher = ]|quote=In most European languages Easter is called by some variant of the late Latin word ''Pascha'', which in turn derives from the Hebrew ''pesach'', meaning ''passover''. |date=1998 |isbn = 978-0060974688}}</ref>|group="nb"}} (], ], ]) or '''Resurrection Sunday''',{{refn|The term "Resurrection Sunday" is used particularly by Christian communities in the ].<ref name="GammanBindon2014">{{cite book |last1=Gamman |first1=Andrew |last2=Bindon |first2=Caroline |title=Stations for Lent and Easter |date=2014 |publisher=Kereru Publishing Limited |isbn=978-0473276812 |page=7 |quote=Easter Day, also known as Resurrection Sunday, marks the high point of the Christian year. It is the day that we celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. }}</ref><ref name="BodaSmith2006">{{cite book|last1=Boda|first1=Mark J.|last2=Smith|first2=Gordon T.|title=Repentance in Christian Theology|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lseYbjrdXhAC&pg=PA316|access-date=19 April 2014 |date=2006 |publisher=Liturgical Press|isbn=978-0814651759|page=316|quote=Orthodox, Catholic, and all Reformed churches in the Middle East celebrate Easter according to the Eastern calendar, calling this holy day "Resurrection Sunday", not Easter.|archive-date=4 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804060401/https://books.google.com/books?id=lseYbjrdXhAC&pg=PA316|url-status=live}}</ref>|group="nb"}} is a ] and cultural ] commemorating the ] from the dead, described in the ] as having occurred on the third day of ] following ] by the ] at ] {{circa|30 AD}}.<ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=gDbKexa1jfcC&q=easter+central+feast&pg=PA224 |title=Anniversaries and Holidays |first1=Bernard |last1=Trawicky |first2=Ruth Wilhelme |last2=Gregory |publisher=]|quote = Easter is the central celebration of the Christian liturgical year. It is the oldest and most important Christian feast, celebrating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. The date of Easter determines the dates of all movable feasts except those of Advent. |date=2000 |isbn = 978-0838906958|access-date = 17 October 2020|archive-date = 12 October 2017|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20171012025026/https://books.google.com/books?id=gDbKexa1jfcC|url-status = live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Aveni | first = Anthony | title = "The Easter/Passover Season: Connecting Time's Broken Circle", ''The Book of the Year: A Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays'' | publisher = ] |date=2004 | pages = 64–78 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=4Mmmvol6DvkC | isbn = 0-19-517154-3 | access-date = 17 October 2020 | archive-date = 8 February 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210208133723/https://books.google.com/books?id=4Mmmvol6DvkC | url-status = live }}</ref> It is the culmination of the ], preceded by ] (or ]), a 40-day period of ], ], and ]. | |||

| Easter is a ], meaning it is not fixed in relation to the ]. The ] (325) established the date of Easter as the first Sunday after the full moon (the ]) following the ].<ref></ref> Ecclesiastically, the equinox is reckoned to be on March 21 (regardless of the astronomically correct date), and the "Full Moon" is not necessarily the astronomically correct date. The date of Easter therefore varies between March 22 and April 25. ] bases its calculations on the ] whose March 21 corresponds, during the twenty-first century, to April 3 in the ], in which calendar their celebration of Easter therefore varies between April 4 and May 8. | |||

| Easter-observing ] commonly refer to the week before Easter as ], which in ] begins on ] (marking the entrance of Jesus in Jerusalem), includes ] (on which the betrayal of Jesus is mourned),<ref name=Cooper2013>{{cite book |last=Cooper |first=J.HB. |title=Dictionary of Christianity |date=23 October 2013 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781134265466 |page=124 |quote=Holy Week. The last week in LENT. It begins on PALM SUNDAY; the fourth day is called SPY WEDNESDAY; the fifth is MAUNDY THURSDAY or HOLY THURSDAY; the sixth is Good Friday; and the last 'Holy Saturday', or the 'Great Sabbath'. }}</ref> and contains the days of the ] including ], commemorating the ] and ],<ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=dyWqm3hCMC0C&pg=PA113|title = The Companion to the Book of Common Worship|author = Peter C. Bower|publisher = ]|quote = Maundy Thursday (or ''le mandé''; Thursday of the ''Mandatum'', Latin, commandment). The name is taken from the first few words sung at the ceremony of the washing of the feet, "I give you a new commandment" (John 13:34); also from the commandment of Christ that we should imitate His loving humility in the washing of the feet (John 13:14–17). The term ''mandatum'' (maundy), therefore, was applied to the rite of foot-washing on this day.|access-date = 11 April 2009|isbn = 978-0664502324|date=2003 |archive-date = 8 June 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210608184343/https://books.google.com/books?id=dyWqm3hCMC0C&pg=PA113|url-status = live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Tbb9axN6qFwC&pg=PA33|title = Three Day Feast: Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter|publisher = ]|first=Gail |last=Ramshaw|quote = In the liturgies of the Three Days, the service for Maundy Thursday includes both, telling the story of Jesus' last supper and enacting the footwashing.|date=2004 |access-date = 11 April 2009|isbn = 978-1451408164|archive-date = 5 November 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211105035735/https://books.google.com/books?id=Tbb9axN6qFwC&pg=PA33|url-status = live}}</ref> as well as ], commemorating the crucifixion and death of Jesus.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uZFRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT125|title=New century reference library of the world's most important knowledge: complete, thorough, practical, Volume 3|publisher=Syndicate Pub. Co.|first=Leonard |last=Stuart|quote=Holy Week, or Passion Week, the week which immediately precedes Easter, and is devoted especially to commemorating the passion of our Lord. The Days more especially solemnized during it are ], ], ], and ]. |date=1909 |access-date=11 April 2009|archive-date=5 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211105035735/https://books.google.com/books?id=uZFRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT125|url-status=live}}</ref> In ], the same events are commemorated with the names of days all starting with "Holy" or "Holy and Great", and Easter itself might be called Great and Holy Pascha. In both Western and Eastern Christianity, ], the Easter or Paschal ], begins on Easter Sunday and lasts seven weeks, ending with the coming of the 50th day, ], but in Eastern Christianity the ] of the feast is on the 39th day, the day before the ]. | |||

| Easter is linked to the Jewish ] not only for much of its symbolism but also for its position in the calendar. In most European languages the feast called Easter in English is termed by the words for passover in those languages and in the older English versions of the Bible the term Easter was the term used to translate passover.<ref>Oxford English Dictionary</ref><ref>Francis X. Weiser, Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs, page 210, New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company - 1958</ref> | |||

| Easter and its related holidays are ]s, not falling on a fixed date; ] is computed based on a ] (solar year plus Moon phase) similar to the ], generating a number of ]. The ] (325) established common Paschal observance by all Christians on the first Sunday after the first ] on or after the vernal ].<ref name="oikoumene.org">{{cite web|url=http://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/wcc-commissions/faith-and-order-commission/i-unity-the-church-and-its-mission/frequently-asked-questions-about-the-date-of-easter.html|title=Frequently asked questions about the date of Easter|access-date=22 April 2009|archive-date=22 April 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110422235601/http://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/wcc-commissions/faith-and-order-commission/i-unity-the-church-and-its-mission/frequently-asked-questions-about-the-date-of-easter.html }}</ref> Even if calculated on the basis of the ], the date of that full moon sometimes differs from that of the astronomical first full moon after the ].<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1923JRASC..17..141W |title=Clarence E. Woodman, "Easter and the Ecclesiastical Calendar" in ''Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada'' |bibcode=1923JRASC..17..141W |access-date=12 May 2019 |archive-date=12 May 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190512191909/http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1923JRASC..17..141W |url-status=live |last=Woodman |first=Clarence E. |journal=Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada |date=1923 |volume=17 |page=141 }}</ref> | |||

| Relatively newer elements such as the ] and ] hunts have become part of the holiday's modern celebrations, and those aspects are often celebrated by many Christians and non-Christians alike. There are also some Christian denominations who do not celebrate Easter. | |||

| The English term is derived from the ] spring festival {{lang|ang|]}};<ref name="Gamber2014">{{cite book |last1=Gamber |first1=Jenifer |title=My Faith, My Life, Revised Edition: A Teen's Guide to the Episcopal Church |date=September 2014 |publisher=Church Publishing |isbn=978-0-8192-2962-5 |page=96 |language=en |quote=The word "Easter" comes from the Anglo-Saxon spring festival called Eostre. Easter replaced the pagan festival of Eostre.}}</ref> Easter is linked to the Jewish ] by its name (]: {{Lang|he|פֶּסַח}} ''pesach'', ]: {{lang|tmr|פָּסחָא}} ''pascha'' are the basis of the term Pascha), by its origin (according to the ], both the crucifixion and the resurrection took place during the week of Passover)<ref>{{Cite web|title=5 April 2007: Mass of the Lord's Supper {{!}} BENEDICT XVI|url=http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20070405_coena-domini.html|access-date=1 April 2021|website=www.vatican.va|archive-date=5 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210405050523/http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20070405_coena-domini.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Reno|first=R. R.|date=14 April 2017|title=The Profound Connection Between Easter and Passover |work=]|url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-profound-connection-between-easter-and-passover-1492173908|access-date=1 April 2021|issn=0099-9660|archive-date=17 December 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211217090449/https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-profound-connection-between-easter-and-passover-1492173908|url-status=live}}</ref> and by much of its symbolism, as well as by its position in the calendar. In most European languages, both the Christian Easter and the Jewish Passover are called by the same name; and in the older ] of the Bible, as well, the term Easter was used to translate Passover.<ref>{{cite book|first=Francis X.|last=Weiser|url=https://archive.org/details/handbookofchrist0000weis/page/214|title=Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs|page=|location=New York|publisher=Harcourt, Brace and Company |date=1958 |isbn=0-15-138435-5}}</ref> | |||

| == Theological significance == | |||

| The ] teaches that the resurrection of Jesus, which Easter celebrates, is a foundation of the Christian faith.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{bibleverse|1|Corinthians|15:12-20}}</ref> The resurrection established Jesus as the powerful son of God<ref name="ReferenceA"/> and is cited as proof that God will judge the world in righteousness.<ref>{{bibleverse||Acts|17:31}}</ref> God has given Christians "a new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead".<ref>{{bibleverse|1|Peter|1:3|HCSB}}</ref> Christians, through faith in the working of God<ref>{{bibleverse||Colossians|2:12}}</ref> are spiritually resurrected with Jesus so that they may walk in a new way of life.<ref>{{bibleverse||Romans|6:4}}</ref> | |||

| ] vary across the ], and include ]s or ]; exclamations and exchanges of ]s; ];<ref name="Whitehouse2022">{{cite book |last1=Whitehouse |first1=Bonnie Smith |title=Seasons of Wonder: Making the Ordinary Sacred Through Projects, Prayers, Reflections, and Rituals: A 52-week devotional |date=15 November 2022 |publisher=Crown Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-593-44332-3 |pages=95–96 |language=en}}</ref> the wearing of ]s by women; ];<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198607663.001.0001/acref-9780198607663-e-201 | title=clipping the church | publisher=Oxford University Press | work=Oxford Reference | doi=10.1093/acref/9780198607663.001.0001 | date=2003 | last1=Simpson | first1=Jacqueline | last2=Roud | first2=Steve | isbn=9780198607663 | access-date=31 March 2013 | archive-date=12 April 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200412143800/http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198607663.001.0001/acref-9780198607663-e-201 | url-status=live }}</ref> and the decoration and the communal breaking of ]s (a symbol of the ]).<ref name="Jordan2000">{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=mzKVPZthGHUC&q=easter+egg+Christian&pg=PA51|title = Christianity|publisher = ]|first=Anne |last=Jordan|quote = Easter eggs are used as a Christian symbol to represent the empty tomb. The outside of the egg looks dead but inside there is new life, which is going to break out. The Easter egg is a reminder that Jesus will rise from His tomb and bring new life. Eastern Orthodox Christians dye boiled eggs red to represent the blood of Christ shed for the sins of the world. |date=2000 |access-date=7 April 2012 |isbn=978-0748753208 |archive-date=8 February 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210208133819/https://books.google.com/books?id=mzKVPZthGHUC&q=easter+egg+Christian&pg=PA51|url-status = live}}</ref><ref name="tomb1">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hPMVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA119|title=The Guardian, Volume 29|publisher=H. Harbaugh|quote=Just so, on that first Easter morning, Jesus came to life and walked out of the tomb, and left it, as it were, an empty shell. Just so, too, when the Christian dies, the body is left in the grave, an empty shell, but the soul takes wings and flies away to be with God. Thus you see that though an egg seems to be as dead as a stone, yet it really has life in it; and also it is like Christ's dead body, which was raised to life again. This is the reason we use eggs on Easter. (In olden times they used to color the eggs red, so as to show the kind of death by which Christ died, – a ''bloody'' death.) |date=1878 |access-date=7 April 2012|archive-date=4 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804014344/https://books.google.com/books?id=hPMVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA119|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="tomb2">{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Wn-38NunUnAC&pg=PT120|title = Christian belief and practice|publisher = ]|author = Gordon Geddes, Jane Griffiths|quote = Red eggs are given to Orthodox Christians after the Easter Liturgy. They crack their eggs against each other's. The cracking of the eggs symbolizes a wish to break away from the bonds of sin and misery and enter the new life issuing from Christ's resurrection.|date=2002 |access-date = 7 April 2012|isbn = 978-0435306915|archive-date = 29 July 2020|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200729113653/https://books.google.com/books?id=Wn-38NunUnAC&pg=PT120|url-status = live}}</ref> The ], a symbol of the resurrection in Western Christianity,<ref>{{cite news|title=Easter Lily Tradition and History|url=http://guardianlv.com/2014/04/easter-lily-tradition-and-history/|last=Collins|first=Cynthia|date=19 April 2014|newspaper=The Guardian|access-date=20 April 2014|quote=The Easter Lily is symbolic of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Churches of all denominations, large and small, are filled with floral arrangements of these white flowers with their trumpet-like shape on Easter morning.|archive-date=17 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200817151814/https://guardianlv.com/2014/04/easter-lily-tradition-and-history/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Schell|first=Stanley |title=Easter Celebrations|url=https://archive.org/details/EasterCelebrations |date=1916 |publisher=Werner & Company|page=|quote=We associate the lily with Easter, as pre-eminently the symbol of the Resurrection.}}</ref> traditionally decorates the ] area of ] on this day and for the rest of Eastertide.<ref>{{cite book|title=Luther League Review: 1936–1937|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4GDTAAAAMAAJ|date=1936|publisher=Luther League of America|access-date=20 June 2015|archive-date=3 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803094720/https://books.google.com/books?id=4GDTAAAAMAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> Additional customs that have become associated with Easter and are observed by both Christians and some non-Christians include ]s, communal dancing (Eastern Europe), the ] and ]ing.<ref name="Duchak2002" /><ref name="Sifferlin2015" /><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GZsHDG1-4X0C&pg=PT109|title=The Church Standard, Volume 74|publisher=Church Publishing, Inc.|quote=In parts of Europe, the eggs were dyed red and were then cracked together when people exchanged Easter greetings. Many congregations today continue to have Easter egg hunts for the children after the services on Easter Day.|first=Vicki K. |last=Black |date=2004|access-date=7 April 2012|isbn=978-0819225757|archive-date=4 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804005753/https://books.google.com/books?id=GZsHDG1-4X0C&pg=PT109|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=c4FPAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA844|title=The Church Standard, Volume 74|publisher=Walter N. Hering|quote=When the custom was carried over into Christian practice the Easter eggs were usually sent to the priests to be blessed and sprinkled with holy water. In later times the coloring and decorating of eggs was introduced, and in a royal roll of the time of Edward I., which is preserved in the Tower of London, there is an entry of 18d. for 400 eggs, to be used for Easter gifts.|date=1897|access-date=7 April 2012|archive-date=30 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200830235433/https://books.google.com/books?id=c4FPAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA844|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=if70Aqo36WYC&pg=PR5|title = From Preparation to Passion|quote = So what preparations do most Christians and non-Christians make? Shopping for new clothing often signifies the belief that Spring has arrived, and it is a time of renewal. Preparations for the Easter Egg Hunts and the Easter Ham for the Sunday dinner are high on the list too.|date=2010 |access-date = 7 April 2012|isbn = 978-1609577650|last1 = Brown|first1 = Eleanor Cooper| publisher=Xulon Press |archive-date = 4 August 2020|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200804020716/https://books.google.com/books?id=if70Aqo36WYC&pg=PR5|url-status = live}}</ref> There are also traditional ]s that vary by region and culture. | |||

| Easter is linked to the ] and ] recorded in the ] through the ] and ] that preceded the resurrection. According to the narratives of the New Testament, Jesus gave the Passover meal a new meaning, as he prepared himself and his disciples for his death in the ] during the Last Supper. He identified the loaf of bread and cup of wine as symbolizing ] soon to be ] and ] soon to be shed. {{bibleverse|1|Corinthians|5:7|NIV}} states, "Get rid of the old yeast that you may be a new batch without yeast—as you really are. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed"; this refers to the Passover requirement to have no yeast in the house and to the allegory of Jesus as the ].<ref>{{bibleverse||John|1:29}}, {{bibleverse||Revelation|5:6}}, {{bibleverse|1|Peter|1:19}}, {{bibleverse|1|Peter|1:2}}, and the associated notes and Passion Week table in {{cite book|editor=Barker, Kenneth|title=Zondervan NIV Study Bible|publisher=]|location=]|year=2002|isbn=0310929555|page=1520}}</ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| One interpretation of the ] is that Jesus, as the Passover lamb, was crucified at roughly the same time as the Passover lambs were being slain in the temple, on the afternoon of ].<ref>{{bibleverse||Exodus|12:6}}.</ref><ref>The scriptural instructions specify that the lamb is to be slain "between the two evenings", that is, at twilight. By the Roman period, however, the sacrifices were performed in the mid-afternoon. Josephus, ''Jewish War'' 6.10.1/423 ("They sacrifice from the ninth to the eleventh hour"). Philo, ''Special Laws'' 2.27/145 ("Many myriads of victims from noon till eventide are offered by the whole people").</ref> This interpretation, however, is inconsistent with the ] in the ]. It assumes that text literally translated "the preparation of the passover" in {{bibleverse||John|19:14|YLT}} refers to Nisan 14 (Preparation Day for the Passover) and not necessarily to ] (Friday, Preparation Day for ])<ref>{{bibleverse||John|13:2}}, {{bibleverse||John|18:28}}, {{bibleverse||John|19:14}}, and the associated notes in {{cite book|editor=Barker, Kenneth|title=Zondervan NIV Study Bible|publisher=]|location=]|year=2002|isbn=0310929555}}</ref> and that the priests' desire to be ritually pure in order to "eat the passover" in {{bibleverse||John|18:28|YLT}} refers to eating the Passover lamb, not to the public offerings made during the days of Unleavened Bread ({{bibleverse||Leviticus|23:8|KJV}}). | |||

| {{main|Ēostre|Names of Easter}} | |||

| The modern English term ''Easter'', ] with modern ] {{lang|nl|ooster}} and ] {{lang|de|Ostern}}, developed from an ] word that usually appears in the form {{lang|ang|Ēastrun}}, {{lang|ang|Ēastron}}, or {{lang|ang|Ēastran}}; but also as {{lang|ang|Ēastru}}, {{lang|ang|Ēastro}}; and {{lang|ang|Ēastre}} or {{lang|ang|Ēostre}}.<ref group="nb">{{IPA|ang|ˈæːɑstre, ˈeːostre}}</ref> ] provides the only documentary source for the etymology of the word, in his eighth-century '']''. He wrote that {{lang|ang|Ēosturmōnaþ}} (Old English for 'Month of Ēostre', translated in ]'s time as "Paschal month") was an English month, corresponding to April, which he says "was once called after a ] of theirs named ], in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month".<ref>{{cite book|last=Wallis|first=Faith|title=Bede: The Reckoning of Time|date=1999 |publisher=Liverpool University Press|isbn=0853236933|page=|title-link=The Reckoning of Time}}</ref> | |||

| In Latin and Greek, the Christian celebration was, and still is, called {{transliteration|grc|Pascha}} (Greek: {{lang|grc|Πάσχα}}), a word derived from ] {{lang|arc|פסחא}} ({{transliteration|arc|Paskha}}), cognate to the Hebrew {{lang|hbo|{{Script/Hebrew|פֶּסַח}}}} ({{transliteration|hbo|Pesach}}). The word originally denoted the Jewish festival known in English as ], commemorating the ].<ref name="HC">{{cite web | url=http://www.history.com/topics/history-of-easter/videos#history-of-the-holidays-easter-video | title=History of Easter | publisher=A&E Television Networks | work=The History Channel website | access-date=9 March 2013 | archive-date=31 May 2013 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130531191802/http://www.history.com/topics/history-of-easter/videos#history-of-the-holidays-easter-video | url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C&pg=PA21|title = The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History|author = Karl Gerlach|publisher = Peeters Publishers|quote = The second century equivalent of easter and the paschal Triduum was called by both Greek and Latin writers "Pascha (πάσχα)", a Greek transliteration of the Aramaic form of the Hebrew פֶּסַח, the Passover feast of Ex. 12.|page = xviii|date=1998 |isbn = 978-9042905702|access-date = 9 January 2020|archive-date = 8 August 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210808003356/https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C&pg=PA21|url-status = live}}</ref> As early as the 50s of the 1st century, ], writing from ] to the Christians in ],<ref>{{bibleverse|1 Corinthians|5:7}}</ref> applied the term to Christ, and it is unlikely that the ] were the first to hear Exodus 12 interpreted as speaking about the ], not just about the Jewish Passover ritual.<ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C&q=%22Pascha%22+name&pg=PA21|title = The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History|author = Karl Gerlach|publisher = Peters Publishers|quote = For while it is from Ephesus that Paul writes, "Christ our Pascha has been sacrificed for us", Ephesian Christians were not likely the first to hear that Ex 12 did not speak about the rituals of Pesach, but the death of Jesus of Nazareth.|page = 21|date=1998 |isbn = 978-9042905702|access-date = 17 October 2020|archive-date = 28 December 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211228004322/https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C&q=%22Pascha%22+name&pg=PA21|url-status = live}}</ref> In most languages, the feast is known by names derived from the Greek and Latin {{transliteration|grc|Pascha}}.<ref name="Etymology"/><ref name="Passover"/> Pascha is also a name by which Jesus himself is remembered in the Orthodox Church, especially in connection with his resurrection and with the season of its celebration.<ref>Orthros of Holy Pascha, Stichera: "Today the sacred Pascha is revealed to us. The new and holy Pascha, the mystical Pascha. The all-venerable Pascha. The Pascha which is Christ the Redeemer. The spotless Pascha. The great Pascha. The Pascha of the faithful. The Pascha which has opened unto us the gates of Paradise. The Pascha which sanctifies all faithful."</ref> Others call the holiday "Resurrection Sunday" or "Resurrection Day", after the Greek {{langx|grc|Ἀνάστασις|Anastasis|Resurrection|label=none}} day.<ref name="GammanBindon2014" /><ref name="BodaSmith2006" /><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.simplycatholic.com/easter-or-resurrection-day/|publisher=Simply Catholic|title=Easter or Resurrection day?|date=17 January 2019|access-date=4 April 2021|archive-date=8 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210608184717/https://www.simplycatholic.com/easter-or-resurrection-day/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.christianpost.com/news/easter-facts-about-resurrection-sunday.html|publisher=Christian Post|title=Easter: 5 facts you need to know about resurrection sunday|date=1 April 2018|access-date=4 April 2021|archive-date=22 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211122123930/https://www.christianpost.com/news/easter-facts-about-resurrection-sunday.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == Origins and etymology == | |||

| === Anglo-Saxon and German === | |||

| ] (1909).]] | |||

| {{Main|Ēostre}} | |||

| The modern English term ''Easter'' is speculated to have developed from ] word ''Ēastre'' or ''Ēostre'' or ''Eoaster'', which itself developed prior to 899. The name refers to ''Eostur-monath'', a month of the ] attested by ] as named after the ] ] of ].<ref name=EASTETYM>] ''The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology'' (1995) ISBN 0-06-270084-7.</ref> Bede notes that Eostur-monath was the equivalent to the month of April, and that feasts held in her honor during Ēostur-monath had died out by the time of his writing, replaced with the Christian custom of Easter.<ref>''De Temporum Ratione'' 15: "Eosturmonath, qui nunc paschalis mensis interpretatur, quondam a dea illorum quae Eostre vocabatur et cui in illo festa celebrabant nomen habuit. A cuius nomine nunc paschale tempus congnominant, consueto antiquae observationis vocabulo gaudia novae solemnitatis vocantes." (Eosturmonath, which now is taken to mean Paschal month, once had its name from their goddess who was called Eostre, and to whom they celebrated a festival in that month. Now they call the Paschal season by the name of this month, calling the joys of the new rite by the old observance's customary name.)</ref> Using comparative linguistic evidence from continental Germanic sources, the 19th century scholar ] proposed the existence of an equivalent form of Eostre among the pre-Christian beliefs of the ], whose name he reconstructed as ''Ostara''. | |||

| == Theological significance == | |||

| The implications of the goddess have resulted in scholarly theories about whether or not Eostre is an invention of Bede, theories connecting Eostre with records of Germanic folk custom (including ]s and ]), and as descendant of the ] through the ] of her name. Grimm's reconstructed Ostara has had some influence in modern popular culture. Modern German has ''Ostern'', but otherwise, Germanic languages have generally borrowed the form pascha, see below. | |||

| ], a concept integral to the foundation of Easter<ref name=Passover>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=CRvzTM0kev4C&pg=PA96|title = Welcome to the Church Year: An Introduction to the Seasons of the Episcopal Church|author = Vicki K. Black|publisher = Church Publishing, Inc.|quote = Easter is still called by its older Greek name, ''Pascha'', which means "Passover", and it is this meaning as the Christian Passover-the celebration of Jesus's triumph over death and entrance into resurrected life-that is the heart of Easter in the church. For the early church, Jesus Christ was the fulfillment of the Jewish Passover feast: through Jesus, we have been freed from slavery of sin and granted to the Promised Land of everlasting life.|date=2004 |isbn = 978-0819219664|access-date = 9 January 2020|archive-date = 8 August 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210808003357/https://books.google.com/books?id=CRvzTM0kev4C&pg=PA96|url-status = live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C&pg=PA21|title = The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History|author = Karl Gerlach|publisher = Peeters Publishers|quote = Long before this controversy, Ex 12 as a story of origins and its ritual expression had been firmly fixed in the Christian imagination. Though before the final decades of the 2nd century only accessible as an exegetical tradition, already in the Pauline letters the Exodus saga is deeply involved with the celebration of bath and meal. Even here, this relationship does not suddenly appear, but represents developments in ritual narrative that must have begun at the very inception of the Christian message. Jesus of Nazareth was crucified during Pesach-Mazzot, an event that a new covenant people of Jews and Gentiles both saw as definitive and defining. Ex 12 is thus one of the few reliable guides for tracing the synergism among ritual, text, and kerygma before the Council of Nicaea.|page = 21|date=1998 |isbn = 978-9042905702|access-date = 9 January 2020|archive-date = 8 August 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210808003356/https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C&pg=PA21|url-status = live}}</ref>]] | |||

| Easter celebrates Jesus' supernatural resurrection from the dead, which is one of the chief tenets of the Christian faith.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Torrey |first1=Reuben Archer |author-link1=Reuben Archer Torrey |title=Torrey's New Topical Textbook |chapter-url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/torrey/ttt.html |access-date=31 March 2013 |date=1897 |chapter=The Resurrection of Christ |archive-date=20 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211120170816/https://www.ccel.org/ccel/torrey/ttt.html |url-status=live }} (interprets primary source references in this section as applying to the Resurrection)<br />{{cite encyclopedia | url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/137622/The-Letter-of-Paul-to-the-Corinthians | title=The Letter of Paul to the Corinthians | publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | access-date=10 March 2013 | archive-date=24 April 2015 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150424020543/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/137622/The-Letter-of-Paul-to-the-Corinthians | url-status=live }}</ref> Paul writes that, for those who trust in Jesus's death and resurrection, "death is swallowed up in victory". The ] declares that God has given believers "a new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead". Christian theology holds that, through faith in the working of God, those who follow Jesus are spiritually resurrected with him so that they may walk in a new way of life and receive eternal ], and can hope to be physically resurrected to dwell with him in the ].<ref name="Jesus EB">{{cite encyclopedia | url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/303091/Jesus-Christ | title=Jesus Christ | publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica | encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online | access-date=11 March 2013 | archive-date=3 May 2015 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150503100711/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/303091/Jesus-Christ | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Easter is linked to ] and the ] recorded in the ] through the ], ], and ] that preceded the resurrection.<ref name=Passover/> According to the three ], Jesus gave the Passover meal a new meaning, as in the ] during the Last Supper he prepared himself and his disciples for his death.<ref name=Passover/> He identified the bread and cup of wine as ], soon to be sacrificed, and ], soon to be shed. The Apostle ] states in his ]: "Get rid of the old yeast that you may be a new batch without yeast—as you really are. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed." This refers to the requirement in Jewish law that Jews eliminate all {{transliteration|he|]}}, or leavening, from their homes in advance of Passover, and to the allegory of Jesus as the ].<ref>{{cite book|editor=Barker, Kenneth|title=Zondervan NIV Study Bible|publisher=]|location=]|date=2002|isbn=0-310-92955-5|page=1520}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C|title = The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History|author = Karl Gerlach|publisher = Peeters Publishers|pages = 32, 56|date=1998 |isbn = 978-9042905702|access-date = 9 January 2020|archive-date = 27 December 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211227231601/https://books.google.com/books?id=PB-zfFmR0I0C|url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| === Semitic, Romance, Celtic and other Germanic languages === | |||

| ]'' by ], completed 1515]] | |||

| == Early Christianity == | |||

| The Greek word Πάσχα and hence the ] form ''Pascha'' is derived from Hebrew ''Pesach'' ({{lang|he|פֶּסַח}}) meaning the festival of ]. In Greek the word Ανασταση, (upstanding, up-rising, resurrection) is used also as an alternative. | |||

| ] celebrated by Jesus and his disciples. The early Christians, too, would have celebrated this meal to commemorate Jesus's death and subsequent resurrection.]] | |||

| As the Gospels assert that both the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus occurred during the week of Passover, the first Christians timed the observance of the annual celebration of the resurrection in relation to Passover.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Landau|first=Brent|title=Why Easter is called Easter, and other little-known facts about the holiday|url=http://theconversation.com/why-easter-is-called-easter-and-other-little-known-facts-about-the-holiday-75025|access-date=3 April 2021|website=The Conversation |date=12 April 2017 |archive-date=12 August 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210812003604/https://theconversation.com/why-easter-is-called-easter-and-other-little-known-facts-about-the-holiday-75025|url-status=live}}</ref> Direct evidence for a more fully formed Christian festival of Pascha (Easter) begins to appear in the mid-2nd century. Perhaps the earliest extant primary source referring to Easter is a mid-2nd-century Paschal ] attributed to ], which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one.<ref name="Melito"> | |||

| Christians speaking ] or other ] generally use names ] to ''Pesach''. For instance, the second word of the Arabic name of the festival {{lang|ar|عيد الفصح}} ''{{transl|ar|DIN|ʿĪd al-Fiṣḥ}}'' has the ] F-Ṣ-Ḥ, which given the ]s applicable to Arabic is cognate to Hebrew P-S-Ḥ, with "Ḥ" realized as {{IPA|/x/}} in Modern Hebrew and {{IPA|/ħ/}} in Arabic. Arabic also uses the term {{lang|ar|عيد القيامة}} ''{{transl|ar|DIN|ʿĪd al-Qiyāmah}}'', meaning "festival of the resurrection," but this term is less common. In ] the word is ''L-Għid''. In ] and the modern ] of ] and ], two forms exist: ፋሲካ ("Fasika," ''fāsīkā'') from Greek ''Pascha'', and ትንሣኤ ("Tensae," ''tinśā'ē''), the latter from the Semitic root N-Ś-', meaning "to rise" (cf. Arabic ''nasha'a'' - ś merged with "sh" in Arabic and most non-]). | |||

| {{cite journal| last = ]| title = Homily on the Pascha| journal = ]| publisher = ]| url = http://www.kerux.com/documents/KeruxV4N1A1.asp| access-date = 28 March 2007| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070312203732/http://www.kerux.com/documents/KeruxV4N1A1.asp| archive-date = 12 March 2007 | df = dmy-all}}</ref> Evidence for another kind of annually recurring Christian festival, those commemorating the martyrs, began to appear at about the same time as the above homily.<ref>Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., ''The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition'', Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 474.</ref> | |||

| While martyrs' days (usually the individual dates of martyrdom) were celebrated on fixed dates in the local solar calendar, the date of Easter was fixed by means of the local Jewish<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Genung|first=Charles Harvey|title=The Reform of the Calendar|jstor=25105305|journal=The North American Review|volume=179|issue=575|date=1904|pages=569–583}}</ref> ]. This is consistent with the celebration of Easter having entered Christianity during its earliest, ], but does not leave the question free of doubt.<ref>Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., ''The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition'', Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 459: " is the only feast of the Christian Year that can plausibly claim to go back to apostolic times ... must derive from a time when Jewish influence was effective ... because it depends on the lunar calendar (every other feast depends on the solar calendar)."</ref> | |||

| In all ] the name of the Easter festival is derived from the Latin ''Pascha''. In Spanish, Easter is ''Pascua'', in Italian ''Pasqua'', in Portuguese ''Páscoa'' and in Romanian ''Paşti''. In French, the name of Easter ''Pâques'' also derives from the Latin word but the ''s'' following the ''a'' has been lost and the two letters have been transformed into a ''â'' with a ] accent by ]. | |||

| The ecclesiastical historian ] attributes the observance of Easter by the church to the ], "just as many other customs have been established", stating that neither Jesus nor his ] enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. Although he describes the details of the Easter celebration as deriving from local custom, he insists the feast itself is universally observed.<ref>Socrates, ''Church History'', 5.22, in {{cite web| last = Schaff| first = Philip| title = The Author's Views respecting the Celebration of Easter, Baptism, Fasting, Marriage, the Eucharist, and Other Ecclesiastical Rites.| work = Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories| publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library| date = 13 July 2005| url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.viii.xxiii.html| access-date = 28 March 2007| archive-date = 16 March 2010| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100316220259/http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.viii.xxiii.html| url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| In all modern ] the term for Easter is derived from Latin. In ] this has yielded Welsh ''Pasg'', ] and ] ''Pask''. In ] the word was borrowed before these languages had re-developed the /p/ sound and as a result the initial /p/ was replaced with /k/. This yielded Irish ''Cáisc'', ] ''Càisg'' and ] ''Caisht''. These terms are normally used with the ] in Goidelic languages, causing ] in all cases: ''An Cháisc'', ''A' Chàisg'' and ''Y Chaisht''. | |||

| == Date == | |||

| In ], Easter is known as ''pasen'' and in the ] Easter is known as ''påske'' (Danish and Norwegian), ''påsk'' (Swedish), ''páskar'' (Icelandic) and ''páskir'' (Faeroese). The name is derived directly from Hebrew Pesach.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=kZIOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA126&lpg=PA126&dq=dutch+word+for+easter+derived+from+hebrew+pesach&source=bl&ots=tUhDdxdLDT&sig=Lzibv_ypo6KEpe46i-i3G8qVPEM&hl=en&ei=mHXZSZqJL5eWMYyY6PkO&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7 |title=A Dictionary of True Etymologies |publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul Books |accessdate=2009-04-05}}</ref> The letter ] is a double a pronounced /o/, and an alternate spelling is ''paaske'' or ''paask''. | |||

| {{Main|Date of Easter}} | |||

| Easter and the holidays that are related to it are ]s, in that they do not fall on a fixed date in the ] or ] calendars (both of which follow the cycle of the sun and the seasons). Instead, the date for Easter is determined on a ] similar to the ]. | |||

| === |

=== Early Church controversies === | ||

| {{Main|Easter controversy}} | |||

| In most Slavic languages, the name for Easter either means "Great Day" or "Great Night". For example, ''Wielkanoc'', ''Veľká noc'' and ''Velikonoce'' mean "Great Night" or "Great Nights" in Polish, ] and ], respectively. Велигден (''Veligden''), Великдень (''Velykden''), Великден (''Velikden''), and Вялікдзень (''Vyalikdzyen''') mean "The Great Day" in ], ], ], and ], respectively. | |||

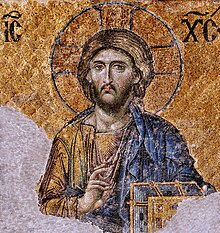

| ] icon depicting the Easter story. ] Christians use a different computation for the date of Easter from the Western churches.]] | |||

| The precise date of Easter has at times been a matter of contention. By the later 2nd century, it was widely accepted that the celebration of the holiday was a practice of the ] and an undisputed tradition. The ] controversy, the first of several ], arose concerning the date on which the holiday should be celebrated.<ref name="NEW ADVENT 1909">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Thurston|first=Herbert| title=Easter Controversy | encyclopedia =The Catholic Encyclopedia | date=1909-05-01 | url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05228a.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230423124325/https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05228a.htm|archive-date=April 23, 2023| access-date=2023-04-23 |publisher=New York: Robert Appleton Company|volume=5|via=New Advent}}</ref> | |||

| In ], however, the day's name reflects a particular theological connection: it is called ''Uskrs'', meaning "Resurrection". It is also called ''Vazam'' (''Vzem'' or ''Vuzem'' in Old Croatian), which is a noun that originated from the ] verb ''vzeti'' (now ''uzeti'' in Croatian, meaning "to take"). In ] Easter is called ''Vaskrs,'' a liturgical form inherited from the Serbian recension of ]. The archaic term ''Velja noć'' (''velmi'': Old Slavic for "great"; ''noć'': "night") was used in Croatian while the term ''Velikden'' ("Great Day") was used in Serbian. It is believed that ], the "holy brothers" who baptized the Slavic people and translated Christian books from Greek into Old Church Slavonic, invented the word ''Uskrs'' from the Croatian word ''krsnuti'' which means "to enliven".<ref>{{CathEncy|wstitle=Sts. Cyril and Methodius}}</ref> It should be noted that in these languages the prefix ''Velik'' (Great) is used in the names of the ] and the three feast days preceding Easter. | |||

| The term "Quartodeciman" refers to the practice of ending the Lenten fast on ] 14 of the ], "the {{LORD}}'s passover".<ref>{{bibleverse|Leviticus|23:5|ESV}}</ref> According to the church historian ], the Quartodeciman ] (bishop of ], by tradition a disciple of ]) debated the question with ] (bishop of Rome). The ] was Quartodeciman, while the Roman and Alexandrian churches continued the fast until the Sunday following (the Sunday of Unleavened Bread), wishing to associate Easter with Sunday. Neither Polycarp nor Anicetus persuaded the other, but they did not consider the matter ] either, parting in peace and leaving the question unsettled.<ref name="Christian Classics Ethereal Library 2">{{cite web |first1=Philip|last1=Schaff|first2=Tim|last2=Perrine|title= NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine|via= Christian Classics Ethereal Library| url=https://ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf201/npnf201.ii.html | access-date=2023-04-23|series=Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220730023344/https://ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf201/npnf201.i.html|archive-date=July 30, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| Another exception is Russian, in which the name of the feast, Пасха (''Paskha''), is a borrowing of the Greek form via ].<ref>], Russisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Heidelberg, 1950-1958.</ref> | |||

| Controversy arose when ], bishop of Rome a generation after Anicetus, attempted to ] ] and all other bishops of Asia for their Quartodecimanism. According to Eusebius, a number of synods were convened to deal with the controversy, which he regarded as all ruling in support of Easter on Sunday.<ref>Eusebius, Church History 5.23.</ref> Polycrates ({{circa|190}}), however, wrote to Victor defending the antiquity of Asian Quartodecimanism. Victor's attempted excommunication was apparently rescinded, and the two sides reconciled upon the intervention of bishop ] and others, who reminded Victor of the tolerant precedent of Anicetus.<ref name="Kelly 1978 p. ">{{cite book | last=Kelly | first=J. N. D. | title=Early Christian doctrines | publication-place=San Francisco | date=1978 | isbn=0-06-064334-X | oclc=3753468 | publisher=Harper & Row | page=}}</ref><ref name="Grace Communion International 2018">{{cite web | title=The Passover-Easter-Quartodeciman Controversy | website=Grace Communion International | date=2018-11-22 | url=https://www.gci.org/articles/the-passover-easter-quartodeciman-controversy/ | access-date=2023-04-23}}</ref> | |||

| === Finno-Ugric languages === | |||

| In Finnish the name for Easter ''pääsiäinen'', traces back to the verb ''pääse-'' meaning ''to be released'', as does the ] word ''Beassážat''. The ] name ''lihavõtted'' and the Hungarian ''húsvét'', however, literally mean ''the taking of the meat'', relating to the end of the Great Lent fasting period. | |||

| Quartodecimanism seems to have lingered into the 4th century, when ] recorded that some Quartodecimans were deprived of their churches by ]<ref>Socrates, ''Church History'', 6.11, at {{cite web| last = Schaff| first = Philip| title = Of Severian and Antiochus: their Disagreement from John.| work = Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories| publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library| date = 13 July 2005| url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.ix.xii.html| access-date = 28 March 2009| archive-date = 13 October 2010| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20101013152952/http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.ix.xii.html| url-status = live}}</ref> and that some were harassed by ].<ref>Socrates, ''Church History'' 7.29, at {{cite web| last = Schaff| first = Philip| title = Nestorius of Antioch promoted to the See of Constantinople. His Persecution of the Heretics.| work = Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories| publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library| date = 13 July 2005| url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.x.xxix.html| access-date = 28 March 2009| archive-date = 13 October 2010| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20101013184700/http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.x.xxix.html| url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| == Easter in the early Church == | |||

| ] in ] on the ] from the ] to the ].]] | |||

| It is not known how long the Nisan 14 practice continued. But both those who followed the Nisan 14 custom, and those who set Easter to the following Sunday, had in common the custom of consulting their Jewish neighbors to learn when the month of Nisan would fall, and setting their festival accordingly. By the later 3rd century, however, some Christians began to express dissatisfaction with the custom of relying on the Jewish community to determine the date of Easter. The chief complaint was that the Jewish communities sometimes erred in setting Passover to fall before the ] spring equinox.<ref>Eusebius, ''Church History'', 7.32.</ref><ref>Peter of Alexandria, quoted in the ]. In Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., ''Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume 14: The Writings of Methodius, Alexander of Lycopolis, Peter of Alexandria, And Several Fragments'', Edinburgh, 1869, p. 326, at {{cite web| last = Donaldson| first = Alexander| title = That Up to the Time of the Destruction of Jerusalem, the Jews Rightly Appointed the Fourteenth Day of the First Lunar Month.| work = Gregory Thaumaturgus, Dionysius the Great, Julius Africanus, Anatolius and Minor Writers, Methodius, Arnobius| publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library| date = 1 June 2005| url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf06.ix.vi.v.html| access-date = 28 March 2009| archive-date = 15 April 2009| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090415004506/http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf06.ix.vi.v.html| url-status = live}}</ref> The ]<ref>MS Verona, Biblioteca Capitolare LX(58) folios 79v–80v.</ref> confirms these complaints, for it indicates that the Jews of some eastern Mediterranean city (possibly ]) fixed Nisan 14 on dates well before the spring equinox on multiple occasions.<ref>Sacha Stern, ''Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE – Tenth Century CE'', Oxford, 2001, pp. 124–132.</ref> | |||

| The first Christians, ] and Gentile, were certainly aware of the ] ({{bibleverse||Acts|2:1}}; {{bibleverse-nb||Acts|12:3}}; {{bibleverse-nb||Acts|20:6}}; {{bibleverse-nb||Acts|27:9}}; {{bibleverse|1|Cor|16:8}}), but there is no direct evidence that they celebrated any specifically Christian annual festivals. The observance by Christians of non-Jewish annual festivals is believed by some to be an innovation postdating the ]. The ecclesiastical historian ] (b. 380) attributes the observance of Easter by the church to the perpetuation of its custom, "just as many other customs have been established," stating that neither ] nor his ] enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. However, when read in context, this is not a rejection or denigration of the celebration—which, given its currency in Scholasticus' time would be surprising—but is merely part of a defense of the diverse methods for computing its date. Indeed, although he describes the details of the Easter celebration as deriving from local custom, he insists the feast itself is universally observed.<ref>Socrates, ''Church History'', 5.22, in {{cite web | |||

| | last = Schaff | |||

| | first = Philip | |||

| | title = The Author’s Views respecting the Celebration of Easter, Baptism, Fasting, Marriage, the Eucharist, and Other Ecclesiastical Rites. | |||

| | work = Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories | |||

| | publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library | |||

| |date=July 13, 2005 | |||

| | url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.viii.xxiii.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-03-28}}</ref> | |||

| Because of this dissatisfaction with reliance on the Jewish calendar, some Christians began to experiment with independent computations.{{refn|Eusebius reports that Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria, proposed an 8-year Easter cycle, and quotes a letter from Anatolius, Bishop of Laodicea, that refers to a 19-year cycle.<ref>Eusebius, ''Church History'', 7.20, 7.31.</ref> An 8-year cycle has been found inscribed on a statue unearthed in Rome in the 17th century, and since dated to the 3rd century.<ref>Allen Brent, ''Hippolytus and the Roman Church in the Third Century'', Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995.</ref>|group=nb}} Others, however, believed that the customary practice of consulting Jews should continue, even if the Jewish computations were in error.<ref name="NEW ADVENT (Church Fathers)">{{cite encyclopedia| title=Church History, Book II (Eusebius) |series=Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, second series|volume=1|publisher=Christian Literature Publishing Co.|date=January 1, 1890|url=https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250102.htm | via=New Advent|translator=Arthur Cushman McGiffert| access-date=2023-04-23|editor1=Philip Schaff|editor2=Henry Wace}}</ref> | |||

| Perhaps the earliest extant primary source referencing Easter is a mid-2nd century Paschal ] attributed to ], which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one.<ref name = "Melito"> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| | first = Melito | |||

| | authorlink = ] | |||

| | title = Homily on the Pascha | |||

| | publisher = ]: The Journal of ]. | |||

| | url = http://www.kerux.com/documents/KeruxV4N1A1.asp | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-03-28}}</ref> Evidence for another kind of annual Christian festival, the commemoration of martyrs, begins to appear at about the same time as evidence for the celebration of Easter.<ref>Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., ''The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition'', Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 474.</ref> But while martyrs' "birthdays" were celebrated on fixed dates in the local solar calendar, the date of Easter was fixed by means of the local Jewish ] calendar. This is consistent with the celebration of Easter having entered Christianity during its earliest, ], but does not leave the question free of doubt.<ref>Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., ''The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition'', Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 459:" is the only feast of the Christian Year that can plausibly claim to go back to apostolic times... must derive from a time when Jewish influence was effective....because it depends on the lunar calendar (every other feast depends on the solar calendar)."</ref> | |||

| === First Council of Nicaea (325 AD) === | |||

| ===Second-century controversy=== | |||

| {{main|First Council of Nicaea}} | |||

| {{details|Quartodecimanism}} | |||

| ], with Arius depicted as defeated by the council, lying under the feet of ]]] | |||

| {{See also|Easter controversy|Passover (Christian holiday)}} | |||

| By the later second century, it was accepted that the celebration of Pascha (Easter) was a practice of the ] and an undisputed tradition. The ] controversy, the first of several ], then arose concerning the date on which Pascha should be celebrated. | |||

| The settlement of the ] caused by the ] practice of Asian ] is listed in our principal source for the works of the ], ]'s ''Ecclesiastical History'', as one of the two reasons for which emperor ] convened the Council in 325.<ref>{{cite book|last=Mosshammer|first=Alden A.|title=The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era|date=2008|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-954312-0|pages=50}}</ref> The Canons of the Council preserved by ] and his successors do not include any relevant provision, but letters of individuals present at the Council mention a decision prohibiting Quartodecimanism and requiring that all Christians adopt a common method to independently determine Paschal observance following the churches of Rome and Alexandria, the latter "since ]."<ref>{{cite book|last=Mosshammer|first=Alden A.|title=The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era|date=2008|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-954312-0|pages=51, 65}}</ref> | |||

| The term "Quartodeciman" refers to the practice of celebrating Pascha or Easter on ] 14 of the ], "the {{LORD}}'s passover" ({{bibleverse||Leviticus|23:5}}). According to the church historian ], the Quartodeciman ] (bishop of Smyrna, by tradition a disciple of ]) debated the question with ] (bishop of Rome). The ] was Quartodeciman, while the Roman and Alexandrian churches continued the fast until the Sunday following, wishing to associate Easter with Sunday. Neither Polycarp nor Anicetus persuaded the other, but they did not consider the matter ] either, parting in peace and leaving the question unsettled. | |||

| Already in the end of the 4th century and, later on, ] and others following him maintained that the bishops assembled at Nicaea had promulgated the celebration of Easter on the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after the vernal equinox and that they had adopted the use of the 19-year lunar cycle, better known as ], to determine the date; subsequent scholarship has refuted this tradition, but, with regards to the rule of the equinox, evidence that the church of Alexandria had implemented it before 325 suggests that the Council of Nicaea implicitly endorsed it.<ref>{{cite book|last=Mosshammer|first=Alden A.|title=The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era|date=2008|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-954312-0|pages=50–52, 53, 62–65}}</ref> | |||

| Canons<ref>Apostolic Canon 7: "If any bishop, presbyter, or deacon shall celebrate the holy day of Easter before the vernal equinox with the Jews, let him be deposed." ''A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church'', Second Series, Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Eerdmans, 1956, p. 594.</ref> and sermons<ref>St. John Chrysostom, "Against those who keep the first Passover", in ''Saint John Chrysostom: Discourses against Judaizing Christians'', translated by Paul W. Harkins, Washington, DC, 1979, pp. 47ff.</ref> condemning the custom of computing Easter's date based on the Jewish calendar indicate that this custom (called "protopaschite" by historians) did not die out at once, but persisted for a time after the Council of Nicaea.<ref name="McGuckin 2011 p.223 ">{{cite book | last=McGuckin | first=John Anthony | title=The encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity | publisher=Wiley-Blackwell | publication-place=Maldin, MA | date=2011 | isbn=978-1-4443-9253-1 | oclc=703879220 | page=223}}</ref> In any case, in the years following the council, the computational system that was worked out by the church of Alexandria came to be normative. The Alexandrian system, however, was not immediately adopted throughout Christian Europe. Following ]' treatise {{lang|la|De ratione Paschae}} (On the Measurement of Easter), Rome retired the earlier ] in favor of Augustalis' 84-year ] cycle, which it used until 457. It then switched to ]'s adaptation of the Alexandrian system.<ref name="Mosshammer 2008 239–244">{{cite book|last=Mosshammer|first=Alden A.|title=The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era|date=2008|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-954312-0|pages=239–244}}</ref><ref name="Holford-Strevens, Leofranc 1999 808–809">{{cite book|last1=Holford-Strevens |first1=Leofranc |last2= Blackburn |first2= Bonnie |title=The Oxford Companion to the Year|date=1999|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=0-19-214231-3|pages=|url=https://archive.org/details/oxfordcompaniont00blac/page/808}}</ref> | |||

| Controversy arose when ], bishop of Rome a generation after Anicetus, attempted to excommunicate ] and all other bishops of Asia for their Quartodecimanism. According to Eusebius, a number of synods were convened to deal with the controversy, which he regarded as all ruling in support of Easter on Sunday.<ref>Eusebius, Church History 5.23.</ref> Polycrates (c. 190), however wrote to Victor defending the antiquity of Asian Quartodecimanism. Victor's attempted excommunication was apparently rescinded and the two sides reconciled upon the intervention of bishop ] and others, who reminded Victor of the tolerant precedent of Anicetus. | |||

| Because this Victorian cycle differed from the unmodified Alexandrian cycle in the dates of some of the Paschal full moons, and because it tried to respect the Roman custom of fixing Easter to the Sunday in the week of the 16th to the 22nd of the lunar month (rather than the 15th to the 21st as at Alexandria), by providing alternative "Latin" and "Greek" dates in some years, occasional differences in the date of Easter as fixed by Alexandrian rules continued.<ref name="Mosshammer 2008 239–244"/><ref name="Holford-Strevens, Leofranc 1999 808–809"/> The Alexandrian rules were adopted in the West following the tables of Dionysius Exiguus in 525.<ref name="Declercq 2000 p.143-144">{{cite book | last=Declercq | first=Georges | title=Anno Domini : the origins of the Christian era | publisher=Turnhout |location= Belgium | date=2000 | isbn=2-503-51050-7 | oclc=45243083 | pages=143–144}}</ref> | |||

| Quartodecimanism seems to have lingered into the fourth century, when ] recorded that some Quartodecimans were deprived of their churches by ]<ref>Socrates, ''Church History'', 6.11, at {{cite web | |||

| | last = Schaff | |||

| | first = Philip | |||

| | title = Of Severian and Antiochus: their Disagreement from John. | |||

| | work = Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories | |||

| | publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library | |||

| |date=July 13, 2005 | |||

| | url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.ix.xii.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2009-03-28}}</ref> and that some were harassed by ].<ref>Socrates, ''Church History'' 7.29, at {{cite web | |||

| | last = Schaff | |||

| | first = Philip | |||

| | title = Nestorius of Antioch promoted to the See of Constantinople. His Persecution of the Heretics. | |||

| | work = Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories | |||

| | publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library | |||

| |date=July 13, 2005 | |||

| | url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf202.ii.x.xxix.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2009-03-28}}</ref> | |||

| Early Christians in Britain and Ireland also used an 84-year cycle. From the 5th century onward this cycle set its equinox to 25 March and fixed Easter to the Sunday falling in the 14th to the 20th of the lunar month inclusive.<ref>{{cite book|last=Mosshammer|first=Alden A.|title=The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era|date=2008|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-954312-0|pages=223–224}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Holford-Strevens |first1=Leofranc |last2= Blackburn |first2= Bonnie|title=The Oxford Companion to the Year|date=1999|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=0-19-214231-3|pages=|url=https://archive.org/details/oxfordcompaniont00blac/page/870}}</ref> This 84-year cycle was replaced by the Alexandrian method in the course of the 7th and 8th centuries. Churches in western continental Europe used a late Roman method until the late 8th century during the reign of ], when they finally adopted the Alexandrian method. Since 1582, when the ] adopted the Gregorian calendar while most of Europe used the Julian calendar, the date on which Easter is celebrated has again differed.<ref>{{cite web |title=Orthodox Easter: Why are there two Easters? |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/48067272 |publisher=BBC Newsround |date=20 April 2020 |access-date=4 April 2021 |archive-date=23 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211223235240/https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/48067272 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Third/fourth-century controversy and Council === | |||

| It is not known how long the Nisan 14 practice continued. But both those who followed the Nisan 14 custom, and those who set Easter to the following Sunday (the Sunday of Unleavened Bread) had in common the custom of consulting their Jewish neighbors to learn when the month of Nisan would fall, and setting their festival accordingly. By the later 3rd century, however, some Christians began to express dissatisfaction with the custom of relying on the Jewish community to determine the date of Easter. The chief complaint was that the Jewish communities sometimes erred in setting Passover to fall before the ] spring equinox. ] in the later third century wrote:<blockquote> | |||

| Those who place in and fix the Paschal fourteenth day accordingly, make a great and indeed an extraordinary mistake<ref>Eusebius, ''Church Histor''y, 7.32.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Peter, ] (died 312), had a similar complaint | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| On the fourteenth day of , being accurately observed after the equinox, the ancients celebrated the Passover, according to the divine command. Whereas the men of the present day now celebrate it before the equinox, and that altogether through negligence and error.<ref>Peter of Alexandria, quoted in the ]. In Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., ''Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume 14: The Writings of Methodius, Alexander of Lycopolis, Peter of Alexandria, And Several Fragments'', Edinburgh, 1869, p. 326, at {{cite web | |||

| | last = Donaldson | |||

| | first = Alexander | |||

| | title = That Up to the Time of the Destruction of Jerusalem, the Jews Rightly Appointed the Fourteenth Day of the First Lunar Month. | |||

| | work = Gregory Thaumaturgus, Dionysius the Great, Julius Africanus, Anatolius and Minor Writers, Methodius, Arnobius | |||

| | publisher = Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library | |||

| | date=June 1, 2005 | |||

| | url = http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf06.ix.vi.v.html | |||

| | accessdate =2009-03-28}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| The ]<ref>MS Verona, Biblioteca Capitolare LX(58) folios 79v-80v.</ref> confirms these complaints, for it indicates that the Jews of some eastern Mediterranean city (possibly ]) fixed Nisan 14 on March 11 (Julian) in A.D. 328, on March 5 in A.D. 334, on March 2 in A.D. 337, and on March 10 in A.D. 339, all well before the spring equinox.<ref>Sacha Stern, ''Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE - Tenth Century CE,'' Oxford, 2001, pp. 124-132.</ref> | |||

| Because of this dissatisfaction with reliance on the Jewish calendar, some Christians began to experiment with independent computations.<ref>Eusebius reports that Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria, proposed an 8-year Easter cycle, and quotes a letter from Anatolius, Bishop of Laodicea, that refers to a 19-year cycle. Eusebius, ''Church History'', 7.20, 7.31. An 8-year cycle has been found inscribed on a statue unearthed in Rome in the 17th century, dated to the third century. Allen Brent, ''Hippolytus and the Roman Church in the Third Centur''y, Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1995.</ref> Others, however, felt that the customary practice of consulting Jews should continue, even if the Jewish computations were in error. A version of the ] used by the sect of the ] advised:<blockquote> | |||

| Do not do your own computations, but instead observe Passover when your brethren from the ] do. If they err , it is no matter to you....<ref>Epiphanius, ''Adversus Haereses'' Heresy 70, 10,1, in Frank Williams, ''The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis Books II and II'', Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1994, p. 412. Also quoted in Margaret Dunlop Gibson, ''The Didascalia Apostolorum in Syriac'', London, 1903, p. vii.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Two other objections that some Christians may have had to maintaining the custom of consulting the Jewish community in order to determine Easter are implied in Constantine's letter from the Council of Nicea to the absent bishops:<blockquote> | |||

| It appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews...For we have it in our power, if we abandon their custom, to prolong the due observance of this ordinance to future ages by a truer order...For their boast is absurd indeed, that it is not in our power without instruction from them to observe these things....Being altogether ignorant of the true adjustment of this question, they sometimes celebrate Passover twice in the same year.<ref>Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 3.18, in A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils'', Eerdmans, 1956, p. 54.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| The reference to Passover twice in the same year might refer to the geographical diversity that existed at that time in the Jewish calendar, due in large measure to the breakdown of communications in the Empire. Jews in one city might determine Passover differently from Jews in another city.<ref>Sacha Stern, ''Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE - Tenth Century CE'', Oxford, 2001, pp. 72-79.</ref> The reference to the Jewish "boast", and, indeed, the strident anti-Jewish tone of the whole passage, suggests another issue: some Christians thought that it was undignified for Christians to depend on Jews to set the date of a Christian festival. | |||

| This controversy between those who advocated independent computations, and those who wished to continue the custom of relying on the Jewish calendar, was formally resolved by the ] in 325 (''see below''), which endorsed the move to independent computations, effectively requiring the abandonment of the old custom of consulting the Jewish community in those places where it was still used. That the older custom (called "protopaschite" by historians) did not at once die out, but persisted for a time, is indicated by the existence of canons<ref>Apostolic Canon 7: If any bishop, presbyter, or deacon shall celebrate the holy day of Easter before the vernal equinox with the Jews, let him be deposed''. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils'', Eerdmans, 1956, p. 594.</ref> and sermons<ref>St. John Chrysostom, "Against those who keep the first Passover", in ''Saint John Chrysostom: Discourses against Judaizing Christians'', translated by Paul W. Harkins, Washington, D.C., 1979, p. 47ff.</ref> against it. | |||