| Revision as of 13:00, 2 March 2010 editJagged 85 (talk | contribs)87,237 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:14, 15 January 2025 edit undoApaugasma (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers17,906 edits Undid revision 1269657452 by EmaRazi (talk) please provide a reliable source talking about Persian writings by al-Razi; Modanlou 2008 plagiarized the 2006 version of this Misplaced Pages article: please see Talk:Abu Bakr al-Razi#Discovery of ethanol and sulfuric acidTag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|10th-century Iranian physician and polymath}} | |||

| {{redirect|Al-Razi|the Islamic theologian and philosopher|Fakhr al-Din al-Razi|other uses|Razi}} | |||

| {{About|the 10th-century physician and polymath|the 12th-century theologian and polymath|Fakhr al-Din al-Razi|other uses|Razi (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Weasel|date=February 2009}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2018}} | |||

| {{Infobox Philosopher | |||

| {{Infobox philosopher | |||

| <!-- Scroll down to edit this page --> | |||

| | era = ] | |||

| <!-- Philosopher Category --> | |||

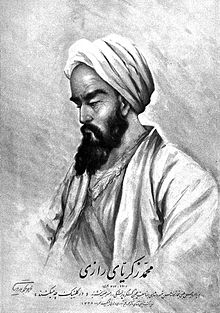

| | image = Portrait of Rhazes (al-Razi) (AD 865 - 925) Wellcome L0005053.jpg | |||

| | region = ] | |||

| | |

| alt = Statue of al-Razi in Vienna | ||

| | |

| caption = Portrait of Rhazes | ||

| | name = Abū Bakr al-Rāzī | |||

| | image_name = Al-RaziInGerardusCremonensis1250.JPG | |||

| | birth_date = 864 or 865 CE<br>250 or 251 ] | |||

| | image_caption = European depiction of the Persian doctor ], in ] "Receuil des traites de medecine" 1250-1260.<ref>"Inventions et decouvertes au Moyen-Age", Samuel Sadaune, p.44</ref> | |||

| | birth_place = ] (Iran) | |||

| | name = Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyā Rāzī | | |||

| | death_date = {{death year and age|925|864}} CE or<br>{{death year and age|935|864}} CE<br>313 or 323 AH | |||

| | birth_date = August 26,{{Citation needed|date=August 2008}} 865 | |||

| | |

| death_place = Ray (Iran) | ||

| | main_interests = Medicine, philosophy, ], criticism of religion | |||

| | ethnicity = ] | |||

| | language = ] (writings) | |||

| | school_tradition = ] | |||

| | influences = | |||

| | main_interests = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | |

| influenced = | ||

| | notable_ideas = The first to write up limited or extensive notes on diseases such as ] and ], a pioneer in ], author of the first book on ], making leading contributions in ] and ], also the author of several philosophical works. | |||

| | influenced = | |||

| | notable_ideas = The discovery of ], first to produce ] such as ], writing up limited or extensive notes on diseases such as ] and ], a pioneer in ] and ], making leading contributions in ] and ], also the author of several philosophical works. | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Abū Bakr al-Rāzī''' (full name: {{langx|ar|أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي|translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī|label=none}}),{{efn|For the spelling of his ] name, see for example {{harvnb|Kraus|1939}}. Sometimes it is also spelled {{langx|ar|زکریا|label=none}} ({{transliteration|ar|Zakariyyā}}) rather than {{langx|ar|زکریاء|label=none}} ({{transliteration|ar|Zakariyyāʾ}}), as for example in {{harvnb|Dānish-pazhūh|1964|loc=p. 1 of the edition}}, or in {{harvnb|Mohaghegh|1993|p=5}}. In modern ] his name is rendered as {{langx|fa|ابوبکر محمدبن زکریا رازی|label=none}} (see {{harvnb|Dānish-pazhūh|1964|loc=p. 1 of the introduction}}), though instead of {{langx|fa|زکریا|label=none}} one may also find {{langx|fa|زکریای|label=none}} (see {{harvnb|Mohaghegh|1993|p=18}}).}} {{circa|864 or 865–925 or 935 CE}},{{efn|For his date of birth, {{harvnb|Kraus|Pines|1913–1936}} give 864 CE / 250 AH ({{harvnb|Goodman|1960–2007}} gives 854 CE / 250 AH, but this is a typo), while {{harvnb|Richter-Bernburg|2003}} and {{harvnb|Adamson|2021a}} give 865 CE / 251 AH. For his date of death as 925 or 935 CE / 313 or 323 AH, see Goodman 1960–2007; some sources only give 925 CE / 313 AH ({{harvnb|Walker|1998}}; Richter-Bernburg 2003; {{harvnb|Adamson|2021a}}).}} often known as '''(al-)Razi''' or by his ] name '''Rhazes''', also rendered '''Rhasis''', was a Persian ], ] and ] who lived during the ]. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine,<ref>{{harvnb|Walker|1998}}; {{harvnb|Iskandar|2008}}; {{harvnb|Adamson|2021a}}.</ref> and also wrote on ], ] and ].<ref>Majid Fakhry, ''A History of Islamic Philosophy: Third Edition'', Columbia University Press (2004), p. 98.</ref> He is also known for his ], especially with regard to the concepts of ] and ]. However, the religio-philosophical aspects of his thought, which also included a belief in five "eternal principles", are fragmentary and only reported by authors who were often hostile to him.<ref>{{harvnb|Adamson|2021a}}</ref> | |||

| ''' Muhammad ibn Zakariyā Rāzī''' (''Mohammad-e Zakariā-ye Rāzi'': {{lang-fa|محمد زکریای رازی}}), known as '''Rhazes''' or '''Rasis''' after medieval ]ists, (August 26, 865, ]— 925, ]) was a ]<ref>{{Citation | |||

| | last =Robinson | |||

| | first =Victor | |||

| | author-link = | |||

| | year =1944 | |||

| | date = | |||

| | publication-date = | |||

| | title =The story of medicine | |||

| | edition = | |||

| | series = | |||

| | place = | |||

| | publication-place =New York | |||

| | publisher =New Home Library | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | id = | |||

| | isbn = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | oclc = | |||

| | url = | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{Citation | |||

| | last =Porter | |||

| | first =Dorothy | |||

| | author-link = | |||

| | publication-date =1999 | |||

| | date = | |||

| | year =2005 | |||

| | title =Health, civilization, and the state : a history of public health from ancient to modern times | |||

| | edition = | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | series = | |||

| | publication-place = | |||

| | place =New York | |||

| | publisher=Routledge | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | page =25 | |||

| | id = | |||

| | isbn =0415200369 | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | oclc = | |||

| | url = | |||

| | accessdate = | |||

| }}</ref> ], ], ], and ]. He is recognised as a ]<ref>History of civilizations of Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-1596-3, vol. IV, part two, p. 228.</ref> and often referred to as "probably the greatest and most original of all the physicians, and one of the most prolific as an author".<ref>{{Harvtxt|Browne|2001|p=44}}</ref> Biographies of Razi, based on his writings, describe him as “perhaps the greatest clinician of all times.” Numerous “firsts” in medical research, clinical care, and chemistry are attributed to him, including being the first to differentiate ] from ], the discovery of numerous compounds and chemicals including ] and ] among others. | |||

| <ref>{{Rhazes: His career and his writings Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Volume 12, Issue 3, Pages 266-272 B.Ligon}}</ref> | |||

| A comprehensive thinker, al-Razi made fundamental and enduring contributions to various fields, which he recorded in over 200 manuscripts, and is particularly remembered for numerous advances in medicine through his ]s and discoveries.<ref>Hakeem Abdul Hameed, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081006200548/http://salaam.co.uk/knowledge/hakeems.php |date=6 October 2008 }}</ref> An early proponent of ], he became a successful doctor, and served as chief physician of ] and ] hospitals.<ref name="ENW2">{{harvnb|Iskandar|2008}}.</ref><ref>Influence of Islam on World Civilization" by Prof. Z. Ahmed, p. 127.</ref> As a teacher of ], he attracted students of all backgrounds and interests and was said to be compassionate and devoted to the service of his patients, whether rich or poor.<ref>Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā, Fuat Sezgin, Māzin ʻAmāwī, Carl Ehrig-Eggert, and E. Neubauer. ''Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyāʼ ar-Rāzī (d. 313/925): texts and studies''. Frankfurt am Main: Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, 1999.</ref> He was the first to clinically distinguish between ] and ], and suggest sound treatment for the former.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=ANSARI|first=A. S. BAZMEE|title=Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Yahya Al-Razi: Universal Scholar and Scientist|date=1976|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/20847003|journal=Islamic Studies|volume=15|issue=3|pages=155–166|jstor=20847003|issn=0578-8072}}</ref> | |||

| Although Rhazes (or Razi) was a ] living in Iran, his work was published in both ] and ] lanugages, as such was the case for most Persian scientists during this era. Such multi-lingual publications in Persia were analogous to the later usage of the Latin language for scientific publications in Europe in the following centuries. | |||

| Through translation, his medical works and ideas became known among medieval European practitioners and profoundly influenced medical education in the Latin West.<ref name="ENW2" /> Some volumes of his work ''Al-Mansuri'', namely "On Surgery" and "A General Book on Therapy", became part of the medical curriculum in Western universities.<ref name="ENW2" /> ] considers him as "probably the greatest and most original of all the Muslim physicians, and one of the most prolific as an author".<ref>{{harvnb|Browne|1921|p=44}}.</ref> Additionally, he has been described as the father of ],<ref name="Tschanz2">{{cite journal|author=Tschanz David W., PhD|year=2003|title=Arab(?) Roots of European Medicine|journal=Heart Views|volume=4|issue=2}}</ref><ref name="Elgood2">{{cite book|title=A Medical History of Persia and The Eastern Caliphate|last1=Elgood|first1=Cyril|date=2010|publisher=Cambridge|isbn=978-1-108-01588-2|edition=1st|location=London|pages=202–203|quote=By writing a monograph on 'Diseases in Children' he may also be looked upon as the father of pediatrics.}}</ref> and a pioneer of ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.unhas.ac.id/rhiza/arsip/saintis/razi.html|title=Ar-Razi (Rhazes), 864–930 C.E.|website=www.unhas.ac.id|access-date=2020-02-27|quote=Ar-Razi was a pioneer in many areas of medicine and treatment and the health sciences in general. In particular, he was a pioneer in the fields of pediatrics, obstetrics and ophthalmology.|archive-date=20 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200220144536/http://www.unhas.ac.id/rhiza/arsip/saintis/razi.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Rhazes made fundamental and enduring contributions to the fields of ], ], ], and ], recorded in over 200 books and articles in various fields of science. He was well-versed in ], ] and ] knowledge and made numerous advances in medicine through own ]s and discoveries.<ref>Hakeem Abdul Hameed, </ref> | |||

| Well educated in music, mathematics, philosophy, and metaphysics, he finally chose ] as his professional field. As a physician, he was an early proponent of ] and is considered the father of ].<ref name=Tschanz>David W. Tschanz, PhD (2003), "Arab(?) Roots of European Medicine", ''Heart Views'' '''4''' (2).</ref> He was also a pioneer of ] and ].<ref>S Safavi-Abbasi, LBC Brasiliense, RK Workman (2007), "The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire", ''Neurosurg Focus'' '''23''' (1), E13, p. 3.</ref> He was among the first to use ] to distinguish one contagious disease from another. In particular, Razi was the first physician to distinguish ] and ] through his clinical characterization of the two diseases. And as an alchemist, Rhazes is known for his study of ] and for his discovery of ] and its refinement to use in ]. He became chief physician of Rayy and Baghdad hospitals. Razi Invented what today is known as rubbing alcohol. | |||

| Rhazes was a ] and very confident in the power of ]; he was widely regarded by his contemporaries and biographers as liberal and free from any kind of prejudice and very bold and daring in expressing his ideas without a qualm. | |||

| He traveled extensively but mostly in ]. As a teacher in medicine, he attracted students of all disciplines and was said to be compassionate and devoted to the service of his patients, whether rich or poor. | |||

| ==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| {{Cleanup-section|date=June 2007}} | |||

| Al-Razi was born in the city of ] (modern Rey, also the origin of his ] "al-Razi"),<ref name="auto">{{harvnb|Adamson|2021a}}.</ref> into a family of Persian stock and was a native speaker of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Kahl|2015|page=6}}<br/>{{nowrap|{{harvnb|Ruska|1937|page=4}}}}<br/>{{harvnb|Ullmann|1997|page=29}}<br />{{harvnb|Sarton|1927|page=590}}<br/>{{harvnb|Hitti|1969|page=188}}<br/>{{harvnb|Walzer|1962|page=18}}</ref> Ray was situated on the ] that for centuries facilitated trade and cultural exchanges between East and West. It is located on the southern slopes of the ] mountain range situated near ], Iran. | |||

| {{pagenumbers|section}} | |||

| {{Peacock|date=June 2008}} | |||

| In his youth, al-Razi moved to ] where he studied and practiced at the local ] (hospital). Later, he was invited back to Rey by ], then the governor of Ray, and became a bimaristan's head.<ref name="ENW2" /> He dedicated two books on medicine to Mansur ibn Ishaq, ''The Spiritual Physic'' and ''Al-Mansūrī on Medicine''.<ref name="ENW2" /><ref>{{Cite web | |||

| ] | |||

| | last = Rāzī | |||

| Rhazes was born on 28 August 865 CE and died on 6 October 925 CE.<ref>]</ref> His name ''Razi'' in ] means from the city of ], an ancient town called Ragha in ] and Ragâ in ].<ref> | |||

| | first = Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā | |||

| {{cite book | first1 = Mary | last1 =Boyce | first2= Grenet| last2=Frantz |authorlink=| title =History of Zoroastrianism: Under The Achaemenians| place = Leiden | publisher =Brill | year = 1982|isbn= 9004065067}} p. 8. See also ( | |||

| | title = The Book of Medicine Dedicated to Mansur and Other Medical Tracts – Liber ad Almansorem | |||

| {{cite encyclopedia | last = Gnoli| first = Gerardo| author = Gerardo Gnoli| authorlink = | coauthors = | editor = | encyclopedia = Encyclopaedia Iranica | title = AVESTAN GEOGRAPHY | url = http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/unicode/v3f1/v3f1a043.html | accessdate = | accessyear = | accessmonth = | edition = | date = | year = | month = | publisher = | volume = 3 | location = | id = | isbn =0710091214 | oclc = | doi = | pages = | quote = }} excerpt: "the question of the identification of Avestan Raya with the Raga in the inscription of Darius I at Bīsotūn with Ray has by no means been settled.")</ref> It is located on the southern slopes of the ] situated near ], ]. In this city (like ]) he accomplished most of his work<ref>. Free Health Encyclopedia, 2006</ref> | |||

| | work = World Digital Library | |||

| | language = la | |||

| | access-date = 2 March 2014 | |||

| | url = http://www.wdl.org/en/item/7381/ | |||

| }}</ref><ref name = "bookonmedicinededicatedtoalmansur">{{Cite web | |||

| | last = Rāzī | |||

| | first = Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā | |||

| | title = The Book on Medicine Dedicated to al-Mansur – الكتاب المنصوري في الطب | |||

| | work = World Digital Library | |||

| | language = am, ar | |||

| | access-date = 2 March 2014 | |||

| | url = http://www.wdl.org/en/item/4276/ | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | title = Commentary on the Chapter Nine of the Book of Medicine Dedicated to Mansur – Commentaria in nonum librum Rasis ad regem Almansorem | |||

| | work = World Digital Library | |||

| | language = la | |||

| | access-date = 2 March 2014 | |||

| | year = 1542 | |||

| | url = http://www.wdl.org/en/item/10672/ | |||

| }}</ref> Because of his newly acquired popularity as physician, al-Razi was invited to Baghdad where he assumed the responsibilities of a director in a new hospital named after its founder ] (d. 902 CE).<ref name="ENW2" /> Under the reign of Al-Mutadid's son, ] (r. 902–908) al-Razi was commissioned to build a new hospital, which should be the largest of the ]. To pick the future hospital's location, al-Razi adopted what is nowadays known as an ] approach suggesting having fresh meat hung in various places throughout the city and to build the hospital where meat took longest to rot.<ref>{{cite journal | pmc= 3644752 | pmid=23661862 | doi=10.4103/0257-7941.107357 | volume=31 | issue=4 | title=Rhazes' concepts and manuscripts on nutrition in treatment and health care |vauthors=Nikaein F, Zargaran A, Mehdizadeh A | journal=Anc Sci Life | pages=160–3| year=2012 | doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| He spent the last years of his life in his native Rey suffering from ]. His eye affliction started with cataracts and ended in total blindness.<ref>Magner, Lois N. ''A History of Medicine''. New York: M. Dekker, 1992, p. 140.</ref> The cause of his blindness is uncertain. One account mentioned by ] attributed the cause to a blow to his head by his patron, ], for failing to provide proof for his alchemy theories;<ref>{{Cite book| publisher = CRC Press| isbn = 978-0-8247-4360-4| last = Magner| first = Lois N.| title = A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded| date = 13 August 2002|page=60}}</ref> while ] and ] claimed that the cause was a diet of beans only.<ref>Pococke, E. ''Historia Compendosia Dynastiarum''. Oxford, 1663, p. 291.</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Long|first=George|title=The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Volume 19|year=1841|publisher=C. Knight|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/pennycyclopdias23longgoog|quote=rhazes.}}</ref> Allegedly, he was approached by a physician offering an ointment to cure his blindness. Al-Razi then asked him how many layers does the ] contain and when he was unable to receive an answer, he declined the treatment stating "my eyes will not be treated by one who does not know the basics of its anatomy".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ddc.aub.edu.lb/projects/saab/S16R27/html-640/003-002.html |title=Saab Medical Library – كتاب في الجدري و الحصبة – American University of Beirut |publisher=Ddc.aub.edu.lb |date=1 June 2003 |access-date=15 October 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120425001329/http://ddc.aub.edu.lb/projects/saab/S16R27/html-640/003-002.html |archive-date=25 April 2012 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| In his early life he could have been a musician or singer (see Ibn abi Usaibi'ah) but more likely a lute-player who shifted his interest from music to alchemy (cf. ibn Juljul, Sa'id, ], Usaibi'ah, al-Safadi). At the age of 30 (Safadi says after 40) he stopped his study of alchemy because his experimentation had caused an eye-disease (Cf. ]), obliging him to search for physicians and medicine to cure it. ], ] and others, say this was the reason why he began his medical studies. | |||

| The lectures of al-Razi attracted many students. As ] relates in '']'', al-Razi was considered a '']'', an honorary title given to one entitled to teach and surrounded by several circles of students. When someone raised a question, it was passed on to students of the 'first circle'; if they did not know the answer, it was passed on to those of the 'second circle', and so on. When all students would fail to answer, al-Razi himself would consider the query. Al-Razi was a generous person by nature, with a considerate attitude towards his patients. He was charitable to the poor, treated them without payment in any form, and wrote for them a treatise ''Man La Yaḥḍuruhu al-Ṭabīb'', or ''Who Has No Physician to Attend Him'', with medical advice.<ref>Porter, Roy. ''The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity''. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997, p. 97.</ref> One former pupil from ] came to look after him, but as ] wrote, al-Razi rewarded him for his intentions and sent him back home, proclaiming that his final days were approaching.<ref name="Brilliant Biruni">Kamiar, Mohammad. ''Brilliant Biruni: A Life Story of Abu Rayhan Mohammad Ibn Ahmad''. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press, 2009.</ref> According to Biruni, al-Razi died in Rey in 925 sixty years of age.<ref name="Al-Birūni">Ruska, Julius. ''Al-Birūni als Quelle für das Leben und die Schriften al-Rāzi's''. Bruxelles: Weissenbruch, 1922.</ref> Biruni, who considered al-Razi his mentor, among the first penned a short biography of al-Razi including a bibliography of his numerous works.<ref name="Al-Birūni" /> | |||

| He studied medicine under ], known as Ali ibn Rabban al-Tabari or Ali ibn Sahl, (''Cf.'' al-Qifti, Usaibi'ah), a physician and philosopher born in Merv about 192 AH (808 C.E.) (d. approx. 240 AH (855 C.E.)). ] belonged to the medical school of ] or ]). | |||

| ] recorded an account by al-Razi of a ] student who copied down all of ]'s works in ] as al-Razi read them to him out loud after the student learned fluent Arabic in 5 months and attended al-Razi's lectures.<ref name="NeedhamWang1954">{{cite book|author1=Joseph Needham|author2=Ling Wang|title=中國科學技術史|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lNXZGQVdz_gC&pg=PA219|year=1954|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-05799-8|pages=219–}}</ref><ref name="Gernet1996">{{cite book|author=Jacques Gernet|title=A History of Chinese Civilization|url=https://archive.org/details/historyofchinese00gern|url-access=registration|date=31 May 1996|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-49781-7|pages=–}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.physique48.org/serv/razi.htm|title=الرازي|first=فيزياء|last=غليزان|access-date=24 December 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303224956/http://www.physique48.org/serv/razi.htm|archive-date=3 March 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nooonbooks.com/media/downloadable/files/links/2/5/pages/25058/OPS/Text/chapter-012.xml|title=قلم لنكبرده ولساكسه , قلم الصين|access-date=2 November 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304223624/http://www.nooonbooks.com/media/downloadable/files/links/2/5/pages/25058/OPS/Text/chapter-012.xml|archive-date=4 March 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Razi became famous in his native city as a physician. He became Director of the hospital of Rayy (''Cf.'' ibn Juljul, al-Qifti, ibn abi Usaibi'ah), during the reign of Mansur ibn Ishaq ibn Ahmad ibn Asad who was Governor of Rayy from 290-296 AH (902-908 C.E.) on behalf of his cousin Ahmad ibn Isma'il ibn Ahmad, second Samanian ruler. Razi dedicated his ''al-Tibb al-'Mansuri''to Mansur ibn Ishaq ibn Ahmad, which was verified in a handwritten manuscript of his book. This was refuted by ibn al-Nadim', but al-Qifti and ibn abi Usaibi'ah confirmed that the named Mansur was indeed Mansur ibn Isma'il who died in 365 AH (975 C.E.). Razi moved from Rayy to Baghdad during Caliph Muktafi's reign (approx. 289-295 AH (901-907 C.E.)) where he again held a position as Chief Director of a hospital. | |||

| After his death, his fame spread beyond the Middle East to Medieval Europe, and lived on. In an undated catalog of the library at ], most likely from the 14th century, al-Razi is listed as a part author of ten books on medicine.<ref>Gunton, Simon. The History of the Church of Peterborough. London, Richard Chiswell, publisher, 1686. Facsimile edition published by Clay, Tyas, and Watkins in Peterborough and Stamford (1990). Item Fv. on pp. 187–8.</ref> | |||

| After al-Muktafi's death in 295 AH (907 C.E.) Razi allegedly returned to Rayy where he gathered many students around him. As ] relates in '']'', Razi was then a '']'' (title given to one entitled to teach), surrounded by several circles of students. When someone arrived with a scientific question, this question was passed on to students of the 'first circle'. if they did not know the answer, it was passed on to those of the 'second circle'... and so on and on, until at last, when all others had failed to supply an answer, it came to Razi himself. We know of at least one of these students who became a physician. Razi was a very generous man, with a humane behavior towards his patients, and acting charitable to the poor. He used to give them full treatment without charging any fee, nor demanding any other payment. {{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} | |||

| ==Contributions to medicine== | |||

| Some {{Who|date=October 2009}}say the cause of his blindness was that he used to eat too many broad beans (''baqilah'').{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} His eye affliction started with cataracts and ended in total blindness. The rumor goes that he refused to be treated for cataract, declaring that he "had seen so much of the world that he was tired of it.{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}}" However, this seems to be an anecdote more than a historical fact. One of his pupils from Tabaristan came to look after him, but, according to al-Biruni, he refused to be treated proclaiming it was useless as his hour of death was approaching. Some days later he died in Rayy, on the 5th of Sha'ban 313 AH (27 October, 925 C.E.). | |||

| ], 1894–1968)]] | |||

| {{More citations needed section| date= May 2012}} | |||

| == |

===Psychology and psychotherapy=== | ||

| Al-Razi was one of the world's first great medical experts. He is considered the father of psychology and psychotherapy.<ref name="Claude Philips">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jAO0CgAAQBAJ&q=al+razi+father+of+ophthalmology&pg=PA111|title=No Wonder You Wonder!: Great Inventions and Scientific Mysteries|last=Phipps|first=Claude|date=2015-10-05|publisher=Springer|isbn=9783319216805|language=en|page=111}}</ref> | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=June 2007}} | |||

| {{Cleanup-rewrite|2=section|date=May 2009}}however, ] indicates that he studied philosophy under al-Bakhi, who had travelled much and possessed great knowledge of philosophy and ancient sciences. Some even say that Razi attributed some of al-Balkhi's books on philosophy to himself. We know nothing about this man called al-Balkhi, not even his full name.<ref>. U.S. National | |||

| {{Peacock|date=June 2008}} | |||

| {{Weasel|date=February 2009}} | |||

| Razi studied medicine under ], Library of Medicine, 1998</ref><ref>. Dr. A. Zahoor, 1997</ref> | |||

| Razi's opponents, on the contrary, are well-known. They are the following: | |||

| *], chief of the ''Mu'tazilah'' of Baghdad (d. 319 AH/931 CE), a contemporary of Razi who wrote many refutations about Razi's books, especially in his ''Ilm al-Ilahi''. His disagreements with Razi entailed his thoughts on the concept of 'Time'. | |||

| *], with whom Razi had many controversies; one of these was on the concept of 'Pleasure', expounded in his ''Tafdll Ladhdhat al-Nafs'' which ] quotes in his work ''Siwan al-Hikmah''. Al-Balkhi died prior to 329 AH/940 CE. | |||

| *Abu Hatim al-Razi (Ahmad ibn Hamdan). an Isma'ili missionary, was one of his most influential opponents (d. 322 AH/933-934 CE). He published his controversies with Razi in his book ''A'lam al-Nubuwwah''. Because of this book, Razi's thoughts on Prophets and Religion are preserved to the present time. | |||

| *] (seemingly being ], according to Kraus) was a physician who had some disputes with Razi, as documented by Abu Hatim al-Razi in ''A'lam al-Nubuwwah''. Ibn al-Tammar disagreed with Razi's book ''al-Tibb al-Ruhani'' but Razi rebutted him in two antitheses: | |||

| :First refutation of al-Tammar's disagreement with ''Misma'i'' concerning 'Matter'. | |||

| : Second refutation of al-Tammar's opinion of 'the Atmosphere of subterranean habitations'. | |||

| *Following are authors as described by Razi in his writings: | |||

| **Al-Misma'i, a ''Mutakallim'', who opposed 'materialists', counteracted Razi's treatise. | |||

| **Jarir, a physician who had a theory about 'The eating of black mulberries after consuming water-melon'. | |||

| **Al-Hasan ibn Mubarik al-Ummi, to whom Razi wrote two epistles with commentaries. | |||

| **Al-Kayyal, a ''Mutakallim'': al-Razi wrote a book on about his ''Theory of the Imam''. | |||

| **Mansur ibn Talhah, being the author of the book "''Being''", which was criticized by al-Razi. | |||

| **Muhammad ibn al-Laith al-Rasa'ili whose opposition against alchemists was disputed by al-Razi. | |||

| *Ahmad ibn al-Tayyib al-Sarakhasi (d. 286 AH/899 CE), was an older contemporary of al-Razi. Al-Razi disagreed with him on the question of 'bitter taste'. He moreover opposed his teacher Ya'qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi, regarding his writings, in which he discredited alchemists. | |||

| More names could be added to this list of all people opposed by al-Razi, specifically the ''Mu'tazilah'' and different ''Mutakallimin''. | |||

| ==Contributions to medicine== | |||

| ===Smallpox vs. measles=== | ===Smallpox vs. measles=== | ||

| <!-- Commented out: ] -->Al-Razi wrote: | |||

| ] | |||

| As chief physician of the ] hospital, Razi formulated the first known description of ]: | |||

| <blockquote>Smallpox appears when blood "boils" and is infected, resulting in vapours being expelled. Thus juvenile blood (which looks like wet extracts appearing on the skin) is being transformed into richer blood, having the color of mature wine. At this stage, smallpox shows up essentially as "bubbles found in wine" (as blisters)... this disease can also occur at other times (meaning: not only during childhood). The best thing to do during this first stage is to keep away from it, otherwise this disease might turn into an epidemic.</blockquote>Al-Razi's book ''al-Judari wa al-Hasbah'' (''On Smallpox and Measles'') was the first book describing ] and ] as distinct diseases.<ref>{{cite book| author=Fuat Sezgin| title=Ar-Razi. In: Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine| date=1970| publisher=E. J. Brill| location=Leiden| pages=276, 283|author-link = Fuat Sezgin}}</ref> | |||

| The work was translated into Syriac, then into Greek. It became known in Europe through this Greek translation, as well as Latin translations based on the Greek text, and was later translated into several European languages.<ref name="A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Rhazes"></ref> Neither the date nor the author of the Syriac and Greek versions is known; but the Greek was created at the request of one of the ] emperors.<ref name="A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, Rhazes"/> | |||

| Its lack of dogmatism and its ] reliance on clinical observation show al-Razi's medical methods. For example, he wrote:<blockquote>The eruption of smallpox is preceded by a continued fever, pain in the back, itching in the nose and nightmares during sleep. These are the more acute symptoms of its approach together with a noticeable pain in the back accompanied by fever and an itching felt by the patient all over his body. A swelling of the face appears, which comes and goes, and one notices an overall inflammatory color noticeable as a strong redness on both cheeks and around both eyes. One experiences a heaviness of the whole body and great restlessness, which expresses itself as a lot of stretching and yawning. There is a pain in the throat and chest and one finds it difficult to breathe and cough. Additional symptoms are: dryness of breath, thick spittle, hoarseness of the voice, pain and heaviness of the head, restlessness, nausea and anxiety. (Note the difference: restlessness, nausea and anxiety occur more frequently with "measles" than with smallpox. At the other hand, pain in the back is more apparent with smallpox than with measles). Altogether one experiences heat over the whole body, one has an inflamed colon and one shows an overall shining redness, with a very pronounced redness of the gums. (Rhazes, Encyclopaedia of Medicine)</blockquote> | |||

| === Meningitis === | |||

| This diagnosis is acknowledged by the '']'' (1911), which states: "The most trustworthy statements as to the early existence of the disease are found in an account by the 9th-century Persian physician Rhazes, by whom its symptoms were clearly described, its pathology explained by a humoral or fermentation theory, and directions given for its treatment." | |||

| Al-Razi compared the outcome of patients with ] treated with ] with the outcome of those treated without it to see if blood-letting could help.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66204/|title=Testing Treatments: Better Research for Better Healthcare|last1=Evans|first1=Imogen|last2=Thornton|first2=Hazel|last3=Chalmers|first3=Iain|last4=Glasziou|first4=Paul|date=1 January 2011|publisher=Pinter & Martin|isbn=9781905177486|edition=2nd|location=London|pmid=22171402}}</ref> | |||

| Razi's book: ''al-Judari wa al-Hasbah'' (On Smallpox and Measles) was the first book describing ] and ] as distinct diseases. It was translated more than a dozen times into ] and other European languages. Its lack of dogmatism and its ] reliance on clinical observation show Razi's medical methods. For example: | |||

| "The eruption of smallpox is preceded by a continued fever, pain in the back, itching in the nose and nightmares during sleep. These are the more acute symptoms of its approach together with a noticeable pain in the back accompanied by fever and an itching felt by the patient all over his body. A swelling of the face appears, which comes and goes, and one notices an overall inflammatory color noticeable as a strong redness on both cheeks and around both eyes. One experiences a heaviness of the whole body and great restlessness, which expresses itself as a lot of stretching and yawning. There is a pain in the throat and chest and one finds it difficult to breath and cough. Additional symptoms are: dryness of breath, thick spittle, hoarseness of the voice, pain and heaviness of the head, restlessness, nausea and anxiety. (Note the difference: restlessness, nausea and anxiety occur more frequently with 'measles' than with smallpox. At the other hand, pain in the back is more apparent with smallpox than with measles). Altogether one experiences heat over the whole body, one has an inflamed colon and one shows an overall shining redness, with a very pronounced redness of the gums." | |||

| ===Allergies and fever=== | |||

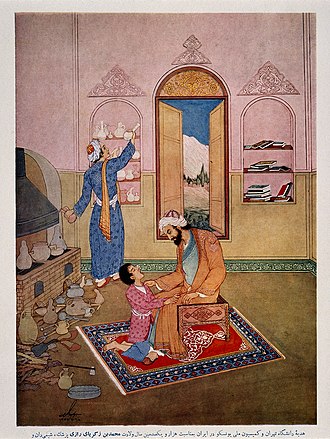

| ]'s ''Recueil des traités de médecine'' translated by ], second half of 13th century.]] | |||

| Razi is also known for having discovered "allergic asthma," and was the first physician ever to write articles on ] and ]. In the ''Sense of Smelling'' he explains the occurrence of ']' after smelling a rose during the Spring: | |||

| ''Article on the Reason Why Abou Zayd Balkhi Suffers from Rhinitis When Smelling Roses in Spring''. In this article he discusses seasonal 'rhinitis', which is the same as allergic asthma or ]. Razi was the first to realize that ] is a natural defense mechanism, the body's way of fighting disease. | |||

| ===Pharmacy=== | ===Pharmacy=== | ||

| Al-Razi contributed in many ways to the early practice of ]<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.islamicmedicine.org/alrazi3.htm | title=The valuable contributions of Al-Razi (Rhazes) in the history of pharmacy during the middle ages | access-date=16 June 2017 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171204104627/http://www.islamicmedicine.org/alrazi3.htm | archive-date=4 December 2017 | url-status=dead }}</ref> by compiling texts, in which he introduces the use of "] ointments" and his development of apparatus such as mortars, flasks, spatulas and phials, which were used in pharmacies until the early twentieth century.{{citation needed|date=September 2021}} | |||

| ===Ethics of medicine=== | ===Ethics of medicine=== | ||

| On a professional level, Razi introduced many practical, progressive, medical and psychological ideas. He attacked ]s and fake doctors who roamed the cities and countryside selling their ] |

On a professional level, al-Razi introduced many practical, progressive, medical and psychological ideas. He attacked ]s and fake doctors who roamed the cities and countryside selling their ] and "cures". At the same time, he warned that even highly educated doctors did not have the answers to all medical problems and could not cure all sicknesses or heal every disease, which was humanly speaking impossible. To become more useful in their services and truer to their calling, al-Razi advised practitioners to keep up with advanced knowledge by continually studying medical books and exposing themselves to new information. He made a distinction between curable and incurable diseases. Pertaining to the latter, he commented that in the case of advanced cases of cancer and ] the physician should not be blamed when he could not cure them. To add a humorous note, al-Razi felt great pity for physicians who took care for the well being of princes, nobility, and women, because they did not obey the doctor's orders to restrict their diet or get medical treatment, thus making it most difficult being their physician. | ||

| He also wrote the following on medical ethics: | He also wrote the following on ]: | ||

| {{blockquote|sign=|source=|The doctor's aim is to do good, even to our enemies, so much more to our friends, and my profession forbids us to do harm to our kindred, as it is instituted for the benefit and welfare of the human race, and God imposed on physicians the oath not to compose mortiferous remedies.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070922222605/http://muslimheritage.com/topics/default.cfm?ArticleID=570 |date=22 September 2007 }}, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.</ref>}} | |||

| ] (from a Latin translation of a work by al-Razi, 1466)]] | |||

| {{quote|"The doctor's aim is to do good, even to our enemies, so much more to our friends, and my profession forbids us to do harm to our kindred, as it is instituted for the benefit and welfare of the human race, and God imposed on physicians the oath not to compose mortiferous remedies."<ref>, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.</ref>}} | |||

| ===Books and articles on medicine=== | ===Books and articles on medicine=== | ||

| ;'']'' | |||

| *'''''The Virtuous Life''''' ('''''al-Hawi''''' '''''الحاوي'''''). | |||

| This 23-volume set medical textbooks contains the foundation of gynaecology, obstetrics and ophthalmic surgery.<ref name="Claude Philips" /> | |||

| ;''The Virtuous Life'' (''al-Hawi'' ''الحاوي''). | |||

| ::This monumental medical ] in nine volumes — known in Europe also as ''The Large Comprehensive'' or ''Continens Liber'' (''جامع الكبير'') —<!-- and also as ''The Embody''--> contains considerations and criticism on the Greek philosophers ] and ], and expresses innovative views on many subjects. Because of this book alone, many scholars consider Razi the greatest medical doctor of the ]. | |||

| This monumental medical encyclopedia in nine volumes—known in Europe also as ''The Large Comprehensive'' or ''Continens Liber'' (''جامع الكبير'')—contains considerations and criticism on the Greek philosophers ] and ], and expresses innovative views on many subjects.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| ::The ''al-Hawi'' is not a formal medical encyclopedia, but a posthumous compilation of Razi's working notebooks, which included knowledge gathered from other books as well as original observations on diseases and therapies, based on his own clinical experience. It is significant since it contains a celebrated monograph on smallpox, the earliest one known. It was translated into Latin in 1279 by ], a physician of Sicilian-Jewish origin employed by ], and after which it had a considerable influence in Europe. | |||

| | last = Rāzī | |||

| | first = Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā | |||

| | title = The Comprehensive Book on Medicine – كتاب الحاوى فى الطب | |||

| | work = World Digital Library | |||

| | access-date = 2 March 2014 | |||

| | url = http://www.wdl.org/en/item/7458 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | title = The Comprehensive Book on Medicine – كتاب الحاوي | |||

| | work = World Digital Library | |||

| | language = ar | |||

| | access-date = 2 March 2014 | |||

| | orig-year = Around 1674 CE | |||

| | url = http://www.wdl.org/en/item/9715 | |||

| | year = 1674 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | last = Rāzī | |||

| | first = Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā | |||

| | title = The Comprehensive Book on Medicine—Continens Rasis | |||

| | work = World Digital Library | |||

| | language = la | |||

| | access-date = 2 March 2014 | |||

| | year = 1529 | |||

| | url = http://www.wdl.org/en/item/9553 | |||

| }}</ref> Because of this book alone, many scholars consider al-Razi the greatest medical doctor of the ]. | |||

| The ''al-Hawi'' is not a formal medical encyclopedia, but a posthumous compilation of al-Razi's working notebooks, which included knowledge gathered from other books as well as original observations on diseases and therapies, based on his own clinical experience. It is significant since it contains a celebrated monograph on smallpox, the earliest one known. It was translated into Latin in 1279 by ], a physician of Sicilian-Jewish origin employed by ], and after which it had a considerable influence in Europe. | |||

| ::The ''al-Hawi'' also criticized the views of ], after Razi had observed many clinical cases which did not follow Galen's descriptions of fevers. For example, he stated that Galen's descriptions of ] ]s were inaccurate as he had only seen three cases, while Razi had studied hundreds of such cases in ] of ] and ].<ref>Emilie Savage-Smith (1996), "Medicine", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., '']'', Vol. 3, p. 903-962 . ], London and New York.</ref> | |||

| The ''al-Hawi'' also criticized the views of ], after al-Razi had observed many clinical cases which did not follow Galen's descriptions of fevers. For example, he stated that Galen's descriptions of ] ]s were inaccurate as he had only seen three cases, while al-Razi had studied hundreds of such cases in ] of ] and Rey.<ref>] (1996), "Medicine", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., '']'', Vol. 3, pp. 903–962 . ], London and New York.</ref> | |||

| *'''''A medical adviser for the general public''''' ('''''Man la Yahduruhu Al-Tabib''''') ('''''من لا يحضره الطبيب''''') | |||

| ;''For One Who Has No Physician to Attend Him'' (''Man la Yahduruhu Al-Tabib'') (''من لا يحضره الطبيب'')—A medical adviser for the general public | |||

| ::Razi was possibly the first Persian doctor to deliberately write a home Medical Manual (]) directed at the general public. He dedicated it to the poor, the traveler, and the ordinary citizen who could consult it for treatment of common ailments when a doctor was not available. This book, of course, is of special interest to the history of pharmacy since similar books were very popular until the 20th century. Razi described in its 36 chapters, diets and drug components that can be found in either an apothecary, a market place, in well-equipped kitchens, or and in military camps. Thus, every intelligent person could follow its instructions and prepare the proper recipes with good results. | |||

| Al-Razi was possibly the first Persian doctor to deliberately write a home medical manual (]) directed at the general public. He dedicated it to the poor, the traveller, and the ordinary citizen who could consult it for treatment of common ailments when a doctor was not available. This book is of special interest to the history of pharmacy since similar books were very popular until the 20th century. Al-Razi described in its 36 chapters, diets and drug components that can be found in either an apothecary, a market place, in well-equipped kitchens, or and in military camps. Thus, every intelligent person could follow its instructions and prepare the proper recipes with good results. | |||

| ::Some of the illnesses treated were headaches, colds, coughing, melancholy and diseases of the eye, ear, and stomach. For example, he prescribed for a feverish headache: " 2 parts of ''duhn'' (oily extract) of ], to be mixed with 1 part of vinegar, in which a piece of ] cloth is dipped and compressed on the forehead". He recommended as a ], " 7 ]s of dried ] flowers with 20 ]s, ] and well mixed, then strained. Add to this ], 20 drams of ] for a drink. In cases of melancholy, he invariably recommended prescriptions, which included either ] or its juice (]), '']'' (clover dodder) or both. For an eye-remedy, he advised ], ], and ], 2 drams each, to be mixed with 1 dram of ] formed into ]s. Each tablet was to be dissolved in a sufficient quantity of ] and used as eye drops. | |||

| *'''''Doubts About ]''''' ('''''Shukuk 'ala alinusor''''') | |||

| Some of the illnesses treated were headaches, colds, coughing, melancholy and diseases of the eye, ear, and stomach. For example, he prescribed for a feverish headache: " 2 parts of ''duhn'' (oily extract) of ], to be mixed with 1 part of vinegar, in which a piece of ] cloth is dipped and compressed on the forehead". He recommended as a ], " 7 ] of dried ] flowers with 20 pears, ] and well mixed, then strained. Add to this ], 20 drams of sugar for a drink. In cases of melancholy, he invariably recommended prescriptions, which included either ] or its juice (]), '']'' (clover dodder) or both. For an eye-remedy, he advised ], ], and ], 2 drams each, to be mixed with 1 dram of ] formed into ]. Each tablet was to be dissolved in a sufficient quantity of ] water and used as eye drops. | |||

| ::Razi's independent mind is revealed in this book and G. Stolyarov II quotes: | |||

| ]<!-- Commented out but usefull image: ] (by Pietro Antonio Rustico, fl. 1486–1522)]]--> | |||

| :::"In the manner of numerous Greek thinkers, including ] and ], Razi rejected the ] and pioneered the concept of ] and self-esteem as being essential to a patient's welfare. This "sound mind, healthy body" connection prompted him to frequently communicate with his patients on a friendly level, encouraging them to heed his advice as a path to their recovery and bolstering their fortitude and determination to resist the illness and resulting in a speedy convalescence." | |||

| ;''Book for al-Mansur ({{lang|ar|Kitāb al-Manṣūrī}})'' | |||

| Al-Razi dedicated this work to his patron ], the ] governor of Ray.<ref>{{harvnb|Adamson|2021b|p=17}}.</ref> It was translated into Latin by ] around 1180.<ref>{{cite web |title=Rāzī, Liber Almansoris (Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 9213) |url=https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-09213/1 |website=Cambridge Digital Library |access-date=22 November 2023}}</ref> A Latin translation of it was edited in the 16th century by the Dutch anatomist and physician ].<ref name="auto"/> | |||

| ;''Doubts about Galen'' ({{transliteration|ar|al-Shukūk ʿalā Jalīnūs}}) | |||

| ::In his book ''Doubts about ]'', Razi rejects several claims made by the Greek physician, as far as the alleged superiority of the ] and many of his ] and medical views. He links medicine with philosophy, and states that sound practice demands independent thinking. He reports that Galen's descriptions do not agree with his own clinical observations regarding the run of a ]. And in some cases he finds that his clinical experience exceeds ]'s. | |||

| In his book ''Doubts about Galen'',<ref>Edited and translated into French by {{harvnb|Koetschet|2019}}. An older edition is {{harvnb|Mohaghegh|1993}}.</ref> al-Razi rejects several claims made by the Greek physician, as far as the alleged superiority of the ] and many of his ] and medical views. He links medicine with philosophy, and states that sound practice demands independent thinking. He reports that Galen's descriptions do not agree with his own clinical observations regarding the run of a fever. And in some cases he finds that his clinical experience exceeds Galen's. | |||

| ::He criticized moreover Galen's theory that the body possessed four separate "]s" (liquid substances), whose balance are the key to health and a natural body-temperature. A sure way to upset such a system was to insert a liquid with a different temperature into the body resulting in an increase or decrease of bodily heat, which resembled the temperature of that particular fluid. Razi noted that a warm drink would heat up the body to a degree much higher than its own natural temperature. Thus the drink would trigger a response from the body, rather than transferring only its own warmth or coldness to it. (''Cf.'' I. E. Goodman) | |||

| He criticized Galen's theory that the body possessed four separate "]" (liquid substances), whose balance are the key to health and a natural body-temperature. A sure way to upset such a system was to insert a liquid with a different temperature into the body resulting in an increase or decrease of bodily heat, which resembled the temperature of that particular fluid. Al-Razi noted that a warm drink would heat up the body to a degree much higher than its own natural temperature. Thus the drink would trigger a response from the body, rather than transferring only its own warmth or coldness to it. (''Cf.'' I. E. Goodman) | |||

| ::This line of criticism essentially had the potentiality to destroy completely Galen's ] including Aristotle's theory of the ], on which it was grounded. Razi's own alchemical experiments suggested other qualities of matter, such as "oiliness" and "sulphurousness", or ] and ], which were not readily explained by the traditional fire, water, earth, and air division of elements. | |||

| This line of criticism essentially had the potential to completely refute Galen's theory of humors, as well as Aristotle's theory of the ], on which it was grounded. Al-Razi's own alchemical experiments suggested other qualities of matter, such as "oiliness" and "sulphurousness", or ] and ], which were not readily explained by the traditional fire, water, earth, and air division of elements. | |||

| ::Razi's challenge to the current fundamentals of medical theory were quite controversial. Many accused him of ignorance and arrogance, even though he repeatedly expressed his praise and gratitude to Galen for his commendable contributions and labors. saying: | |||

| Al-Razi's challenge to the current fundamentals of medical theory was quite controversial. Many accused him of ignorance and arrogance, even though he repeatedly expressed his praise and gratitude to Galen for his contributions and labours, saying: | |||

| :::"I prayed to God to direct and lead me to the truth in writing this book. It grieves me to oppose and criticize the man ] from whose sea of knowledge I have drawn much. Indeed, he is the Master and I am the disciple. Although this reverence and appreciation will and should not prevent me from doubting, as I did, what is erroneous in his theories. I imagine and feel deeply in my heart that Galen has chosen me to undertake this task, and if he were alive, he would have congratulated me on what I am doing. I say this because Galen's aim was to seek and find the truth and bring light out of darkness. I wish indeed he were alive to read what I have published." | |||

| <blockquote>I prayed to God to direct and lead me to the truth in writing this book. It grieves me to oppose and criticize the man ] from whose sea of knowledge I have drawn much. Indeed, he is the Master and I am the disciple. Although this reverence and appreciation will and should not prevent me from doubting, as I did, what is erroneous in his theories. I imagine and feel deeply in my heart that Galen has chosen me to undertake this task, and if he were alive, he would have congratulated me on what I am doing. I say this because Galen's aim was to seek and find the truth and bring light out of darkness. I wish indeed he were alive to read what I have published.<ref>Bashar Saad, Omar Said, ''Greco-Arab and Islamic Herbal Medicine: Traditional System, Ethics, Safety, Efficacy, and Regulatory Issues'', John Wiley & Sons, 2011. {{ISBN|9781118002261}}, </ref></blockquote> | |||

| ::# Crystallization of ancient knowledge, and the refusal to accept the fact that new data and ideas indicate that present day knowledge ultimately might surpass that of previous generations. | |||

| ;''The Diseases of Children'' | |||

| ::Razi believed that contemporary scientists and scholars are by far better equipped, more knowledgeable, and more competent than the ancient ones, due to the accumulated knowledge at their disposal. Razi's attempt to overthrow blind acceptance of the unchallenged authority of ancient Sages, encouraged and stimulated research and advances in the arts, technology, and sciences. | |||

| Al-Razi's ''The Diseases of Children'' was the first monograph to deal with pediatrics as an independent field of medicine.<ref name="Tschanz2"/><ref name="Elgood2"/> | |||

| *'''''The Diseases of Children''''' | |||

| ==Alchemy<!-- ] redirects here; please edit the redirect (via 'what links here') when changing the name of the section heading or the place where Sirr al-asrar is discussed -->== | |||

| ::Al-Razi is considered the father of ] for writing ''The Diseases of Children'', the first book to deal with pediatrics as an independent field of medicine.<ref name=Tschanz/> | |||

| ] painting by Ernest Board, {{Circa|1912}})]] | |||

| {{more citations needed section|date=September 2021}} | |||

| {{See also|Sulfuric acid#History}} | |||

| === |

===The transmutation of metals=== | ||

| Al-Razi's interest in alchemy and his strong belief in the possibility of ] of lesser metals to silver and gold was attested half a century after his death by ]'s book, ''The Philosopher's Stone'' (''Lapis Philosophorum'' in Latin). Nadim attributed a series of twelve books to al-Razi, plus an additional seven, including his refutation to ]'s denial of the validity of alchemy. Al-Kindi (801–873 CE) had been appointed by the Abbasid Caliph Ma'mun founder of Baghdad, to 'the ]' in that city, he was a philosopher and an opponent of alchemy. Al-Razi's two best-known alchemical texts, which largely superseded his earlier ones: ''al-Asrar'' (الاسرار "The Secrets"), and ''Sirr al-Asrar'' (سر الاسرار "The Secret of Secrets"), which incorporates much of the previous work. | |||

| This is a partial list of Razi's books and articles in medicine, according to ]. Some books may have been copied or printed under different names. | |||

| * '']'' (الحاوي), ''al-Hawi al-Kabir'' (الحاوي الكبير). Also known as ''The Virtuous Life'', ''Continens Liber''. The large medical Encyclopedia containing mostly recipes and Razi's notebooks. | |||

| * ''Isbateh Elmeh Pezeshki'' (Persian اثبات علم پزشكى), An Introduction to Medical Science. | |||

| *''Dar Amadi bar Elmeh Pezeshki'' (Persian درآمدى بر علم پزشكى) | |||

| *''Rade Manaategha 'tibb jahez'' | |||

| *''Rade Naghzotibbeh Nashi'' | |||

| *''The Experimentation of Medical Science and its Application'' | |||

| *''Guidance'' | |||

| *''Kenash'' | |||

| *''The Classification of Diseases'' | |||

| *''Royal Medicine'' | |||

| *''For One Without a Doctor'' (من لايحضره الطبيب) | |||

| *''The Book of Simple Medicine'' | |||

| *''The Great Book of Krabadin'' | |||

| *''The Little Book of Krabadin'' | |||

| *''The Book of Taj'' or ''The Book of the Crown'' | |||

| *''The Book of Disasters'' | |||

| *''Food and its Harmfulness'' | |||

| * ''al-Judari wa al-Hasbah'', Translation: ''A treatise on the Small-pox and Measles''<ref>A Treatise on the Small-pox and Measles, Translated by ], Published by Printed for the Sydenham Society , 1848, pp. 252, </ref> | |||

| *''Ketab dar Padid Amadaneh Sangrizeh'' (Persian كتاب در پديدآمدن سنگريزه) (Stones in the Kidney and Bladder) | |||

| *''Ketabeh Dardeh Roodeha'' (Persian كتاب درد رودهها) | |||

| *''Ketab dar Dard Paay va Dardeh Peyvandhayyeh Andam'' (Persian كتاب در درد پاى و درد پيوندهاى اندام) | |||

| *''Ketab dar Falej'' | |||

| *''The Book of Tooth Aches'' | |||

| *''Dar Hey'ateh Kabed'' (Persian در هيأت كبد) | |||

| *''Dar Hey'ateh Ghalb'' (About Heart Ache) | |||

| *''About the Nature of Doctors'' | |||

| *''About the Earwhole''<!--Is that correct?--> | |||

| *''Dar Rag Zadan'' (Persian در رگ زدن) | |||

| *''Seydeh neh/sidneh'' | |||

| *''Ketabeh Ibdal'' | |||

| *''Food For Patients'' | |||

| *''Soodhayeh Serkangabin'' (Persian سودهاى سركنگبين) or ''Benefits of Honey and Vinegar Mixture'' | |||

| *''Darmanhayeh Abneh'' | |||

| *''The Book of Surgical Instruments'' | |||

| *''The Book on Oil'' | |||

| *''Fruits Before and After Lunch'' | |||

| *''Book on Medical Discussion'' (with ]) | |||

| *''Book on Medical Discussion II'' (with ]) | |||

| *''About the Menstrual Cycle'' | |||

| *''Ghi Kardan'' or ''vomiting'' (Persian قى كردن) | |||

| *''Snow and Medicine'' | |||

| *''Snow and Thirst'' | |||

| *''The Foot'' | |||

| *''Fatal Diseases'' | |||

| *''About Poisoning'' | |||

| *''Hunger'' | |||

| *''Soil in Medicine'' | |||

| *''The Thirst of Fish'' | |||

| *''Sleep Sweating'' | |||

| *''Warmth in Clothing'' | |||

| *''Spring and Disease'' | |||

| *''Misconceptions of a Doctors Capabilities'' | |||

| *''The Social Role of Doctors'' | |||

| Apparently al-Razi's contemporaries believed that he had obtained the secret of turning iron and copper into gold. Biographer Khosro Moetazed reports in ''Mohammad Zakaria Razi'' that a certain General Simjur confronted al-Razi in public, and asked whether that was the underlying reason for his willingness to treat patients without a fee. "It appeared to those present that al-Razi was reluctant to answer; he looked sideways at the general and replied":<blockquote>I understand alchemy and I have been working on the characteristic properties of metals for an extended time. However, it still has not turned out to be evident to me, how one can transmute gold from copper. Despite the research from the ancient scientists done over the past centuries, there has been no answer. I very much doubt if it is possible...</blockquote> | |||

| ===Translations=== | |||

| Razi's notable books and articles on medicine (in English) include: | |||

| * ''Mofid al Khavas'', The Book for the Elite. | |||

| * ''The Book of Experiences'' | |||

| * ''The Cause of the Death of Most Animals because of Poisonous Winds'' | |||

| * ''The Physicians' Experiments'' | |||

| * ''The Person Who Has No Access to Physicians'' | |||

| * ''The Big Pharmacology'' | |||

| * ''The Small Pharmacology'' | |||

| * ''Gout'' | |||

| * ''Al Shakook ala Jalinoos'', The Doubt on Galen | |||

| * ''Kidney and Bladder Stones'' | |||

| * ''Ketab tibb ar-Ruhani'',''The Spiritual Physik of Rhazes''. | |||

| ===Major works on alchemy=== | |||

| ==Alchemy== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=November 2021}} | |||

| ===The Transmutation of Metals=== | |||

| Al-Razi's works present the first systematic classification of carefully observed and verified facts regarding chemical substances, reactions and apparatus, described in a language almost entirely free from mysticism and ambiguity. | |||

| Razi's interest in alchemy and his strong belief in the possibility of ] of lesser metals to ] and ] was attested half a century after his death by ]'s book (''The Philosophers Stone''-Lapis Philosophorum in Latin). Nadim attributed a series of twelve books to Razi, plus an additional seven, including his refutation to ]'s denial of the validity of alchemy. Al-Kindi (801-873 CE) had been appointed by the Abbasid Caliph Ma'mum founder of Baghdad, to 'the ]' in that city, he was a philosopher and an opponent of alchemy.<br /> Finally we will mention Razi's two best-known alchemical texts, which largely superseded his earlier ones: ''al-Asrar'' ("The Secrets"), and ''Sirr al-Asrar'' ("The Secret of Secrets"), which incorporates much of the previous work. | |||

| ==== ''The Secrets'' ({{transliteration|ar|Al-Asrar}}) ==== | |||

| Apparently Razi's contemporaries believed that he had obtained the secret of turning ] and ] into ]. Biographer ] reports in ''Mohammad Zakaria Razi'' that a certain ] confronted Razi in public, and asked whether that was the underlying reason for his willingness to treat patients without a fee. "It appeared to those present that Razi was reluctant to answer; he looked sideways at the general and replied": | |||

| :"I understand alchemy and I have been working on the characteristic properties of metals for an extended time. However, it still has not turned out to be evident to me, how one can transmute gold from copper. Despite the research from the ancient scientists done over the past centuries, there has been no answer. I very much doubt if it is possible..." | |||

| ''<nowiki/>'The Secrets'<nowiki/>'' (''al-Asrar'', ''Kitāb al-Asrār'', ''<nowiki/>'Book of Secrets''') was written in response to a request from al-Razi's close friend, colleague, and former student, Abu Muhammad ibn Yunis ], a Muslim mathematician, philosopher, and ]. | |||

| ===Chemical instruments and substances=== | |||

| Razi developed several chemical instruments that remain in use to this day. He is known to have perfected methods of ] and ], which have led to his discovery of ], by dry distillation of ] (''al-zajat''), and ]. These discoveries paved the way for other Persian alchemists, as did the discovery of various other ]s by ] (known as Geber in Europe). As a pioneer of ], Razi was the first to distill/refine petroleum and produce ] (later used as lamp oil and jet fuel). | |||

| ==== ''Secret of Secrets'' ({{transliteration|ar|Sirr al-Asrar}}) ==== | |||

| Razi dismissed the idea of ] and dispensed with magic, meaning the reliance on symbols as causes. Although Razi does not reject the idea that miracles exist, in the sense of unexplained phenomena in nature, his alchemical stockroom was enriched with products of Persian mining and manufacturing, even with ] a Chinese discovery. He relied predominantly on the concept of 'dominant' forms or essences, which is the ] conception of causality rather than an intellectual approach or a mechanical one. Razi's alchemy brings forward such empiric qualities as salinity and inflammability -the latter associated to 'oiliness' and 'sulphurousness'. These properties are not readily explained by the traditional composition of the elements such as: fire, water, earth and air, as ] and others after him were quick to note, influenced by critical thoughts such as Razi had. | |||

| {{Distinguish|text=] (also known as Sirr al-Asrar, 'The Secret Book of Secrets')}}This is al-Razi's most famous book. Here he gives systematic attention to basic chemical operations important to the history of pharmacy. In this book al-Razi divides the subject of "]' into three categories, as in his previous book {{transliteration|ar|Al-Asrar}}. | |||

| # Knowledge and identification of the medical components within substances derived from plants, animals, and minerals, and descriptions of the best types for medical treatments. | |||

| # Knowledge of equipment and tools of interest to and used by either alchemists or ]. | |||

| # Knowledge of seven ] procedures and techniques: sublimation and condensation of ], precipitation of sulfur, and arsenic calcination of ] (gold, silver, copper, lead, and iron), salts, glass, ], ], and ]ing. | |||

| : This last category contains additional descriptions of other methods and applications used in ]: | |||

| ===Major works on alchemy=== | |||

| :* The added mixture and use of solvent vehicles. | |||

| Razi's achievements are of exceptional importance in the history of chemistry, since in his books we find for the first time a systematic classification of carefully observed and verified facts regarding chemical substances, reactions and apparatus, described in a language almost entirely free from mysticism and ambiguity. Razi's scheme of classification of the substances used in chemistry shows sound research on his part. | |||

| :* The amount of heat (fire) used, 'bodies and stones', ({{transliteration|ar|al-ajsad}} and {{transliteration|ar|al-ahjar}}) that can or cannot be transmuted into corporal substances such of metals and salts ({{transliteration|ar|al-amlah}}). | |||

| * '''''The Secret''''' ('''''Al-Asrar''''') | |||

| :* The use of a liquid ] which quickly and permanently colors lesser metals for more lucrative sale and profit. | |||

| Similar to the commentary on the 8th century text on ]s ascribed to ], al-Razi gives methods and procedures of coloring a silver object to imitate gold (]) and the reverse technique of removing its color back to silver. ] and ] of other metals (], calcium salts, iron, copper, and ]) are also described, as well as how colors will last for years without tarnishing or changing. | |||

| ::This book was written in response to a request from Razi's close friend, colleague, and former student, ] of ], a Muslim ], philosopher, a highly reputable ].<br /> In his book ''Sirr al-Asrar'', Razi divides the subject of "Matter' into three categories as he did in his previous book ''al-Asrar''. | |||

| ::# Knowledge and identification of drug components of plant-, animal- and mineral-origin and the description of the best type of each for utilization in treatment. | |||

| ::# Knowledge of equipment and tools of interest to and used by either alchemist or apothecary. | |||

| ::# Knowledge of seven ] procedures and techniques: sublimation and condensation of ], precipitation of sulfur and arsenic calcination of ] (], ], ], ], and ]), ]s, ], ], ]s, and ]ing. | |||

| Al-Razi classified minerals into six divisions: | |||

| ::This last category contains additionally a description of other methods and applications used in transmutation: <br />* The added mixture and use of solvent vehicles.<br /> * The amount of heat (fire) used, 'bodies and stones', ''('al-ajsad' and 'al-ahjar)'' that can or cannot be transmuted into corporal substances such of metals and Id salts ''('al-amlah')''. <br />* The use of a liquid mordant which quickly and permanently colors lesser metals for more lucrative sale and profit. | |||

| # Four spirits ({{transliteration|ar|al-arwah}}): ], ], ], and arsenic sulphide (] and ]). | |||

| ::Similar to the commentary on the 8th century text on amalgams ascribed to Al- Hayan (Jabir), Razi gives methods and procedures of coloring a silver object to imitate gold (]) and the reverse technique of removing its color back to silver. ] and ] of other metals (alum, calcium salts, iron, copper, and tutty) are also described, as well as how colors will last for years without tarnishing or changing. Behind these procedures one does not find a deceptive motive rather a technical and economic deliberation. This becomes evident from the author's quotation of market prices and the expressed triumph of artisan, craftsman or alchemist declaring the results of their efforts "to make it look exactly like gold!". However, another motive was involved, namely, to manufacture something resembling gold to be sold quickly so to help a good friend who happened to be in need of money fast. Could it be Razi's alchemical technique of silvering and gilding metals which convinced many Muslim biographers that he was first a jeweler before he turned to the study of alchemy? | |||

| # ] ({{transliteration|ar|al-ajsad}}): silver, gold, copper, iron, black lead ({{transliteration|ar|plumbago}}), ] ({{transliteration|ar|kharsind}}), and ]. | |||

| # Thirteen ] ({{transliteration|ar|al-ahjar}}): ] ({{transliteration|ar|marqashita}}), ], ], ] ({{transliteration|ar|tutiya}}, zinc oxide), ], ], ], ], ] (iron oxide), arsenic oxide{{which|date=November 2021}}, ], ], and glass (then identified as made of sand and alkali of which the transparent crystal damascene is considered the best). | |||

| # Seven ]s ({{transliteration|ar|al-zajat}}): ] ({{transliteration|ar|al-shabb}} {{lang|ar|الشب}}), and white ({{transliteration|ar|qalqadis}} {{lang|ar|القلقديس}}), black, red ({{transliteration|ar|suri}} {{lang|ar|السوري}}), and yellow ({{transliteration|ar|qulqutar}} {{lang|ar|القلقطار}}) vitriols (the impure sulfates of iron, copper, etc.), green ({{transliteration|ar|qalqand}} {{lang|ar|القلقند}}). | |||

| # Seven ]s: ], and impure sodium borate. | |||

| # Eleven salts ({{transliteration|ar|al-amlah}}): including brine, ], ]es, ], live ], and ], ], and ]s. Then he separately defines and describes each of these substances, the best forms and colours of each, and the qualities of various adulterations. | |||

| Al-Razi gives also a list of apparatus used in alchemy. This consists of 2 classes: | |||

| :Of great interest in the text is Razi's classification of ]s into six divisions, showing his discussion a modern chemical connotation: | |||

| # Instruments used for the dissolving and melting of metals such as the blacksmith's hearth, bellows, crucible, thongs (tongue or ladle), {{linktext|macerator}}, stirring rod, cutter, grinder (pestle), file, shears, {{linktext|descensory}}, and semi-cylindrical iron mould. | |||

| # Four ]s (''AL-ARWAH'') : ], ], ], and ] sulphate (orpiment and realgar). | |||

| # Utensils used to carry out the process of transmutation and various parts of the distilling apparatus: the retort, ], shallow iron pan, potters kiln and blowers, large oven, cylindrical stove, glass cups, flasks, ]s, beakers, glass funnel, crucible, ], heating lamps, mortar, cauldron, hair-cloth, sand- and water-bath, sieve, flat stone mortar and chafing-dish. | |||

| # Seven ] ''(AL-AJSAD)'' : ], ], ], ], black lead (plumbago), ] (Kharsind), and ]. | |||

| # Thirteen ]s : (''AL-AHJAR)'' Pyrites ] (''marqashita''), ], ], ] Zinc oxide ''(tutiya)'', ], ], ], azurite, magnesia , haematite (iron oxide), arsenic oxide, mica and asbestos and ] (then identified as made of sand and alkali of which the transparent crystal ] is considered the best), | |||

| # Seven ]s (AL-ZAJAT) : ] ''(ak-shubub)'', and white ''(qalqadzs)'', black , red, and yellow ''(qulqutar)'' vitriols (the impure sulfates of iron, copper, etc.), green ''(qalqand)''. | |||

| # Seven ]s : ], and impure sodium borate. | |||

| # Eleven ]s ''(AL-AMLAH)'': including brine, common (table) ], ]es, ], live ], and ], ], and ]s. Then he separately defines and describes each of these substances and their top choice, best colors and various adulterations. | |||

| :Razi gives also a list of apparatus used in alchemy. This consists of 2 classes: | |||

| # Instruments used for the dissolving and melting of metals such as the Blacksmith's hearth, bellows, crucible, thongs (tongue or ladle), macerator, stirring rod, cutter, grinder (pestle), file, shears, descensory and semi-cylindrical iron mould. | |||

| # Utensils used to carry out the process of transmutation and various parts of the distilling apparatus: the retort, alembic, shallow iron pan, potters kiln and blowers, large oven, cylindrical stove, glass cups, flasks, phials, beakers, glass funnel, crucible, alundel, heating lamps, mortar, cauldron, hair-cloth, sand- and water-bath, sieve, flat stone mortar and chafing-dish. | |||

| *'''''Secret of Secrets''''' ('''''Sirr Al-asrar''''') | |||

| :This is Razi's most famous book which has gained a lot of recognition in the West. Here he gives systematic attention to basic chemical operations important to the history of pharmacy. | |||

| ===Books on alchemy=== | |||

| Here is a list of Razi's known books on alchemy, mostly in ]: | |||

| *''Modkhele Taalimi'' | |||

| *''Elaleh Ma'aaden'' | |||

| *''Isbaate Sanaa'at'' | |||

| *''Ketabeh Sang'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Tadbir'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Aksir'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Sharafe Sanaa'at'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Tartib'', ''Ketabe Rahat'', ''The Simple Book'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Tadabir'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Shavahed'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Azmayeshe Zar va Sim'' (''Experimentation on Gold'') | |||

| *''Ketabe Serre Hakimaan'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Serr'' (''The Book of Secrets'') | |||

| *''Ketabe Serre Serr'' (''The Secret of Secrets'') | |||

| *''The First Book on Experiments'' | |||

| *''The Second Book on Experiments'' | |||

| *''Resaale'ei Be Faan'' | |||

| *''Arezooyeh Arezookhah'' | |||

| *''A letter to Vazir Ghasem ben Abidellah'' | |||

| *''Ketabe Tabvib'' | |||

| ==Philosophy== | ==Philosophy== | ||

| Although al-Razi wrote extensively on philosophy, most of his works on this subject are now lost.<ref>See the list of 35 works given by {{harvnb|Daiber|2017|pp=389–396}}. Of these, only three are extant in full (see p. 396), though fragments of many other works also survive (edited by {{harvnb|Kraus|1939}}).</ref> Most of his religio-philosophical ideas, including his belief in five "eternal principles", are only known from fragments and testimonies found in other authors, who were often strongly opposed to his thought.<ref>{{Citation |last=Adamson |first=Peter |title=Abu Bakr al-Razi |date=2021 |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/abu-bakr-al-razi/ |encyclopedia=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N. |access-date=2023-12-21 |edition=Summer 2021 |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University|quote=While we have ample surviving evidence for his medical thought, his philosophical ideas mostly have to be pieced together on the basis of reports found in other authors, who are often hostile to him.}}</ref> | |||

| ===On existence=== | |||

| Razi believed that a competent physician must also be a ] well versed in the fundamental questions regarding existence: | |||

| :"He proclaimed the absolutism of ] ] and ] time as the natural foundation of the world in which men lived, but resolved the dilemma of existent infinities by synthesizing this outlook with the atomic theory of ], which recognized that matter existed in the form of indivisible and fathomable ]. The continuity of space, however, holds due to the existence of ], or a region lacking matter... This is remarkably close to the systems yielded by the discoveries of such later European scientists as ] and ], as well as the observational and theoretical works of modern astronomer Halton Arp and Objectivist philosopher ]. Progress, in the view of all these men, is not to be obstructed by a jumble of haphazard and contradictory relativistic assertions which result in metaphysical hodge-podge instead of a sturdy intellectual base. Even in regard to the task of the philosopher, Rhazes considered it to be progressing beyond the level of one's teachers, expanding the accuracy and scope of one's doctrine, and individually elevating oneself onto a higher intellectual plane." (G. Stolyarov II) | |||

| Razi is known to have been a free-thinking philosopher, since he was well-trained in ancient Greek science and philosophy although his approach to chemistry was rather naturalistic. Moreover, he was well versed in the theory of music, as so many other Islamic scientists of that time. | |||

| ===Metaphysics=== | ===Metaphysics=== | ||

| Al-Razi's metaphysical doctrine derives from the theory of the "five eternals", according to which the world is produced out of an interaction between God and four other eternal principles (], ], time, and ]).<ref name="oxford">{{Cite book| publisher = Oxford University Press| isbn = 9780195379488| last = Marenbon| first = John| title = The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Philosophy| date = 14 June 2012|pages=69–70}}</ref> He accepted a pre-socratic type of ] of the bodies, and for that he differed from both the ] and the ].<ref name="oxford" /> While he was influenced by ] and the medical writers, mainly ], he rejected ] and thus expressed criticism about some of their views. This is evident from the title of one of his works, ''Doubts About Galen''.<ref name="oxford" /> | |||

| His ideas on ] were also based on the works of the ancient Greeks: | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==Views on religion== | |||

| :"The metaphysical ] of Razi, insofar as it can be reconstructed, derives from his concept of the five eternal ]. God, for him, does not 'create' the world from nothing but rather arranges a ] out of pre-existing principles. His account of the soul features a mythic origin of the world in which God out of pity fashions a physical playground for the soul in response to its own desires; the soul, once fallen into the new realm God has made for it, requires God's further gift of intellect in order to find its way once more to ] and ]. In this scheme, intellect does not appear as a separate principle but is rather a later grace of God to the soul; the soul becomes intelligent, possessed of reason and therefore able to discern the relative value of the other four principles. Whereas the five principles are eternal, intellect as such is apparently not. Such a doctrine of intellect is sharply at odds with that of all of Razi's philosophical contemporaries, who are in general either adherents of some form of Neoplatonism or of Aristotelianism. The remaining three principles, ], matter and ], serve as the non-animate components of the natural world. Space is defined by the relationship between the individual particles of ], or ], and the void that surrounds them. The greater the density of material atoms, the heavier and more solid the resulting object; conversely, the larger the portion of void, the lighter and less solid. Time and matter have both an absolute, unqualified form and a limited form. Thus there is an absolute matter - pure extent - that does not depend in any way on place, just as there is a time, in this sense, that is not defined or limited by ]. The absolute time of al-Razi is, like ], ]; it thus transcends the time which Aristotle confined to the measurement of motion. Razi, in the cases of both time and matter, knew well how he differed from Aristotle and also fully accepted and intended the consequences inherent in his anti-Peripatetic positions." (Paul E. Walker) | |||