| Revision as of 17:08, 2 February 2006 view sourceKaisershatner (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users17,557 editsm →Muslim military references: title← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:55, 12 January 2025 view source AirshipJungleman29 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors45,153 edits close GAR Misplaced Pages:Good article reassessment/Battle of Badr/1 as delist (GANReviewTool) | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|First major battle in early Islam (624)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| {{pp-protect|small=yes}} | |||

| |conflict=Battle of Badr | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2020}} | |||

| |partof=] | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |image=] | |||

| | |

| conflict = Battle of Badr | ||

| | partof = the ] | |||

| |date= March 17, 624 CE/17 Ramadan, 2 AH | |||

| | image = Siyer-i Nebi - Imam Ali und Hamza bei dem vorgezogenen Einzelkampf in Badr gegen die Götzendiener.jpg | |||

| |place=], just outside ] | |||

| | caption = Scene from ], Hamza and Ali leading the Muslim armies at Badr. The writing is ] ]. | |||

| |result=Muslim victory | |||

| | date = 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan 2 AH) | |||

| |combatant1=] of ] | |||

| | map_type = Saudi Arabia | |||

| |combatant2=] of ] | |||

| | map_relief = 1 | |||

| |commander1=]<br>]<br> ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|23|44|N|38|46|E|region:SA_type:event|display=it}} | |||

| |commander2=] (aka "Abu Jahl")<br>] | |||

| | place = ], ], ] | |||

| |strength1=305-350 | |||

| | result = {{ublist|] victory}} | |||

| |strength2=<900-1000 | |||

| *Survival of the ] | |||

| |casualties1=14 killed | |||

| *Start of ] | |||

| |casualties2=50-70 killed<br>43-70 captured}} | |||

| | combatant1 = ] | |||

| {{Campaignbox Rise of Islam}} | |||

| | combatant2 = ] | |||

| '''The Battle of Badr''' (Arabic بدر), fought ], ] ] (17 ] 2 ] in the ]) in the ] of western ] (present-day ]), was a key battle in the early days of ] and a turning point in ]'s war against his ]<ref>Quraish refers to the tribe in control of Mecca. The plural and adjective are Quraishi. The terms "Quraishi" and "Meccan" are used interchangeably between the ] and the Muslim ].</ref> opponents in ]. Although it is one of the few battles mentioned by name in the Muslim holy book, the ], virtually all contemporary knowledge of the Battle of Badr comes from traditional Islamic accounts, both ] and biographies of Muhammad, written down decades after the battle. | |||

| | commander1 = ''']'''<br /> ] <br />]<br /> ]<br /> ]<br /> ]<br />] {{KIA}}<br />] | |||

| | commander2 = ''']'''{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}} | |||

| | strength1 = '''Total''': 313<br /> | |||

| * ]: 82 | |||

| * ]: 231 | |||

| ** ]: 61 | |||

| ** ]: 170 | |||

| * 2 horses | |||

| * 70 camels | |||

| | strength2 = '''Total''': 1,000<br /> | |||

| * 100 horses | |||

| * 170 camels | |||

| | casualties1 = '''Total''': 14 killed<br /> | |||

| * Muhajirun: 6 | |||

| * Ansar: 8 | |||

| ** Khazraj: 6 | |||

| ** Aws: 2 | |||

| | casualties2 = 70 killed, 70 prisoners<ref>Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 4, Book 52, Number 276</ref>{{cref|f}} | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Campaigns of Muhammad}} | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Battle of Badr''' ({{langx|ar|غَزْوَةُ بَدْرٍ}} {{IPA|ar|ɣazwatu badr|}} (Urdu transliteration: ''Ghazwah-i-Badr''), also referred to as '''The Day of the Criterion''' ({{Langx|ar|يَوْمُ الْفُرْقَانْ}}, {{IPA|ar|jawm'ul fur'qaːn}}) in the ] and by Muslims, was fought on 13 March 624 CE (17 ], 2 ]),<ref>W. Montgomery Watt (1956), Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 12. Watt notes that the date for the battle is also recorded as the 19th or the 21st of Ramadan (15 or 17 March 624).</ref> near the present-day city of ], ] in ]. ], commanding an army of his ], defeated an army of the ] led by ], better known among Muslims as Abu Jahl. The battle marked the beginning of the six-year war between ] and his tribe. Prior to the battle, the Muslims and the Meccans had fought several smaller ] in late 623 and early 624. | |||

| Prior to the battle, the Muslims and Meccans had fought several smaller ] in late 623 and early 624, as the Muslim '']'' plundering raids grew increasingly commonplace, but this was their first large-scale battle. Muhammad was leading a raiding party against a ] when he was surprised by a much larger Quraishi army. Advancing to a strong ], Muhammad's well-disciplined men managed to shatter the Meccan lines, killing several important leaders including Muhammad's chief opponent, ]. The battle has been passed down in Muslim history as a decisive victory ascribed to either ] or the genius of Muhammad. | |||

| Muhammad took keen interest in capturing Meccan caravans after ], seeing it as repayment for his people, the ]. A few days before the battle, when he learnt of a Makkan caravan returning from the ] led by ], Muhammad gathered a small ] to capture it. Abu Sufyan, learning of the Muslim plan to ] his caravan, changed course and took a longer route away from Muhammad's base at ] and sent a messenger to Mecca, asking for help. Amr Bin Hisham commanded an army nearly one-thousand strong, approaching Badr and encamping at the sand dune al-'Udwatul Quswa. | |||

| For the early Muslims, the battle was extremely significant because it was the first sign that they might eventually overcome their enemies in Mecca, one of the richest and most powerful ] cities in Arabia, which fielded an army three times larger than the Muslim one. It also marked the beginning of the end of traditional warfare in Arabia, demonstrating the success of the well-drilled and well-organized Muslim army against a Quraishi army that was more tribal and ad-hoc in nature. | |||

| Badr was the first large-scale engagement between the Muslims and Quraysh Meccans. Advancing from the north, the Muslims faced the Meccans. The battle began with duels between the warriors on both sides, following which the Meccans charged upon the Muslims under a cover of ]s. The Muslims countered their charge and broke the Meccan lines, killing several important Quraishi leaders including ] and ]. | |||

| == Background == | |||

| {{Islam}} | |||

| === Muhammad === | |||

| {{main|Muhammad}} | |||

| At the time of the battle, Arabia was scantly populated by a number of Arabic-speaking peoples. Some were ], pastoral ]s organized in tribes. Some were agriculturalists, living either in oases in the north, or in the more fertile and thickly settled areas to the south (now ] and ]). At that time, the majority of Arabs followed various ] ]s, although a few tribes followed ], ] (including ]), and ]. | |||

| The Muslim victory strengthened Muhammad's position; The Medinese eagerly joined his future expeditions and tribes outside Medina openly allied with Muhammad.<ref>{{cite book|title=Muhammad at Medina|publisher=Clarendon Press|year=1956|author=William Montgomery Watt|page=17|quote=The people of Medina were much readier to join Muhammad's expeditions...The friendly tribes between Medina and the sea were presumably more ready to help Muhammad openly...Pagan nomads in the neighbourhood of Medina were much readier to profess Islam.}}</ref> The battle has been passed down in ] as a decisive victory attributable to ], and by other sources to the strategic prowess of Muhammad. | |||

| Muhammad was born in Mecca around 570 CE into the ] clan, a clan in the ] ]. When he was about forty years old, he is said to have experienced a divine revelation while he was meditating in a cave outside Mecca. After an initial period of doubt and fear, he started to preach to his kinfolk and then in public, to all Meccans. He attracted followers and also created enemies. At first, Muhammad was protected by ]. However, he died in 619 and the leadership of the Banu Hashim passed to one of Muhammad's enemies, ],<ref>The hatred many Muslims had towards Hisham can be seen in his popular nickname, "] ]" (Father of Ignorance), which how the overwhelming majority of Muslims refer to him even to this day.</ref> who withdrew the protection and stepped up persecution of the Muslim community. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| In 622, with open acts of violence being committed against the Muslims by their fellow Quraishi tribesman, Muhammad and many of his followers fled to the neighboring city of ]. This migration is called the '']'' and marked the beginning of Muhammad's reign as a secular chief, in addition to religious leader. | |||

| {{Main|Muhammad in Mecca}} | |||

| {{See also|Hegira|label 1=Hijra}} | |||

| ===The ''Ghazawāt''=== | |||

| After the ] (migration to ]) in 622 CE, the population of Medina chose Muhammad to be the leader of the community. Muhammad's followers decided to raid the caravans of the Meccans as they passed by Medina. This decision was taken in response to the Meccans persecution of the Muslims and their forceful seizing of Muslim land and property following the Hijra.<ref name="Esposito4">John Esposito, ''Islam'', Expanded edition, Oxford University Press, p.4-5</ref> | |||

| Following the hijra, tensions between Mecca and Medina escalated and hostilities broke out in 623 when the Muslims began a series of raids (called '']'' in Arabic) on Quraishi caravans. ''Ghazawāt'' (s. ''ghazw'') were plundering raids organized by nomadic Bedouin warriors against either rival tribes or wealthier, sedentary neighbors. Since Medina was located just off Mecca's main trade route, the Muslims were in an ideal position to do this. Even though many Muslims were Quraish themselves, they believed that they were entitled to steal from them because the Meccans had expelled them from their homes and tribes, a serious offense in hospitality-oriented Arabia.<ref>Quran: Sura 22:39-40.</ref> Also, there was a tradition in Arabia of poor tribes raiding richer tribes, and Mecca was one of the richest cities in the ]. It also provided a means for the Muslim community to carve out an independent economic position at Medina, where their political position was far from secure. The Meccans obviously took a different view, seeing the Muslim raids as ] at best, as well as a potential threat to their livelihood and prestige.<ref>Hodgson, Pages 174-175.</ref> | |||

| In early 624, a caravan of the Quraysh led by ] carrying wealth and ] from the ] (possibly Gaza{{Sfn|Watt|1956|p=10-11}}) was returning to Mecca. It was carrying merchandise worth 50,000 dinars and guarded by 70 men.{{Sfn|Watt|1956|p=10-11}} The caravan was extraordinarily large, possibly because several smaller caravans may have grouped together for safety. All the leading Meccan financiers had a share in this trading venture,{{Sfn|Ramadan|2007|p=100-101}} and thus had a strong interest in it returning.{{Sfn|Watt|1956|p=10-11}} | |||

| In late 623 and early 624, the Muslim ''ghazawāt'' grew increasingly brazen and commonplace. In September 623, Muhammad himself led a force of 200 in an unsuccessful raid against a large caravan. Shortly thereafter, the Meccans launched their own "raid" against Medina, although its purpose was just to steal some Muslim livestock.<ref>http://www.quraan.com/index.aspx?tabindex=4&tabid=11&bid=7&cid=24.</ref> In January 624, the Muslims ambushed a Meccan caravan near ], only forty kilometers outside of Mecca, killing one of the guards and formally inaugurating a ] with the Meccans.<ref>Though the Muslims would claim it had started when they were expelled.</ref> Worse, from a Meccan standpoint, the raid occurred in the month of ], a ] month sacred to the Meccans in which fighting was prohibited and a clear affront to their pagan traditions.<ref>Hodgson, Page 175.</ref> It was in this context that the Battle of Badr took place. | |||

| Muhammad learned of the caravan and decided to intercept it for two reasons. First, was the continuation of the policy to recover wealth from the Quraysh, as the Quraysh had confiscated Muslims' properties in Mecca after the hijrah. Secondly, a successful attack would impress the Meccans and could act as a deterrent against a future attack on Medina.{{Sfn|Ramadan|2007|p=100-101}} | |||

| ==The Battle== | |||

| ] | |||

| Abu Sufyan sent word to Mecca that the caravan was in danger, asking for reinforcements to cover the caravan as it passed by Medina. Traditional Muslim sources write that Abu Sufyan's spies had informed him of Muslim preparations to attack, a view accepted by Ramadan.{{Sfn|Ramadan|2007|p=100-101}} But Watt writes given that it took the Meccan army a week to get to Badr, Abu Sufyan must have sent his request before the Muslim preparations began.{{Sfn|Watt|1986|p=867-868}} Watt points out Abu Sufyan was "one of the most astute men in Mecca" and must have anticipated the Muslim attack.{{Sfn|Watt|1956|p=10-11}} | |||

| In the spring of 624, Muhammad received word from his intelligence sources that one of the richest trade caravans of the year, commanded by ] and guarded by thirty to forty men, was travelling from ] to Mecca. Because of the caravan's size, or perhaps because of the previous failures to intercept a caravan, Muhammad gathered an army of over 300 men, the largest army the Muslims had ever put in the field.<ref>. Sources vary as to the precise number.</ref> | |||

| Muhammad had gathered a small ] of around 300 men to intercept the caravan. Abu Sufyan's spies informed him of the Muslims' plot to ] his caravan. Fearing the loss of wealth that was imminent, Abu Sufyan sent the messenger Damdam bin 'Amr al-Ghifari to the Quraish. Damdam, upon his arrival at the ], cut off the nose and ears of his camel, turned its saddle upside down, tore off his shirt and cried:<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Mubārakfūrī |first=Ṣafī al-Raḥmān |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r_80rJHIaOMC&pg=PA267 |title=The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet |date=2002 |publisher=Darussalam |isbn=978-9960-899-55-8 |language=en}}</ref><blockquote> | |||

| ===The March to Badr=== | |||

| "O Quraish! Your merchandise! It is with Abu Sufyan. The caravan is being intercepted by Muhammad and his companions. I cannot say what would have happened to them. Help! Help!"<ref name=":0" /></blockquote>Abu Sufyan had rerouted his caravan toward the ] and escaped the Muslim threat by Damdam's arrival at Mecca. | |||

| == Battlefield == | |||

| Muhammad commanded the army himself and brought many of his top lieutenants, including ] and future ] ], ], and ]. The Muslims also brought seventy camels and three horses, meaning that they either had to walk or fit three to four men per camel.<ref>Lings, Page 138-139</ref> However, many early Muslim sources, including the Quran, indicate that no serious fighting was expected,<ref></ref> and the future Caliph ] stayed behind to care for his sick wife, one of Muhammad's daughters.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{refimprove|section|date=March 2022}} | |||

| ]The valley of Badr is surrounded by two large sand dunes to the east, called ''al-'Udwatud Dunya'' (the near side of the valley) and ''al-'Udwatul Quswa'' (the far side of the valley). The Qur'an speaks of these two in Surah 8, verse 42. The west of the valley was covered by the al-Asfal Mountain (''Jabal Al-Asfal'') with an opening between it and another hill in the northwest. | |||

| Between al-'Udwatud Dunya and al-'Udwatul Quswa was an opening, which was the primary route to ]. Muhammad and his army did not approach the battlefield from here, they came from the north, as they were originally planning to target the caravan, which was moving from the ] in the north, to ] in the south. Between al-'Udwatul Quswa and the hill covering the southern part of the battlefield was another opening, which was the primary route from Mecca. | |||

| As the caravan approached Medina, Abu Sufyan began hearing from travelers and riders about Muhammad's planned ambush. He sent a messenger named Damdam to Mecca to warn the Quraish and get reinforcements. Alarmed, the Quraish assembled an army of 900-1000 men to rescue the caravan. Many of the Quraishi nobles, including ], ], Shaiba, and ], joined the army. Their reasons varied: some were out to protect their financial interests in the caravan; others wanted to avenge Ibn al-Hadrami, the guard killed at Nakhlah; finally, a few must have wanted to take part in what was expected to be an easy victory against the Muslims.<ref>Martin Lings, Page 139-140.</ref> Amr ibn Hashim is described as shaming at least one noble, Umayah ibn Khalaf, into joining the expedition. | |||

| <ref></ref> | |||

| The Quraish had ] in the south-eastern portion of the valley near the road to Mecca, while Muhammad and his army had encamped in some ] in the north. They had taken a well near the center of the western margin of al-'Udwatul Dunya and destroyed the other wells near the road to Medina to prevent the Makkans from getting any water. Another well situated at the end of the road to Mecca was later filled with the bodies of the dead Makkans. | |||

| By this time Muhammad's army was approaching the wells where he planned to waylay the caravan, at Badr, along the Syrian trade route where the caravan would be expected to stop. However, several Muslim scouts were discovered by scouts from the caravan<ref>Ibn Ishaq says that Abu Sufyan himself rode ahead to reconoiter the area and discovered the Muslim scouts via the ] left in their camels' droppings</ref> and Abu Sufyan made a hasty turn towards ].<ref>Martin Lings, Page 140</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Rainfall === | ||

| On the night of 11 March (15 Ramadan), it had rained over the battlefield and the surrounding region. Muslims believe this was a blessing from Allah for the believers and a curse for the disbelievers, who suffered hardship in trying to climb the muddy slope.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| == Battle == | |||

| <blockquote>''"Behold! Allah promised you one of the two (enemy) parties, that it should be yours: Ye wished that the one unarmed should be yours, but Allah willed to justify the Truth according to His words and to cut off the roots of the Unbelievers;"'' '''Quran Surah 8:7'''</blockquote> | |||

| === Muslim march to Badr === | |||

| Around this time word reached the the Muslim army about the departure of the Meccan army. Muhammad immediately called a ], since there was still time to retreat and because many of the fighters there were recent converts (Called '']'' or "Helpers" to distinguish them from the Quraishi Muslims), who had only pledged to defend Medina. Under the terms of the ], they would have been within their rights to refuse to fight and leave the army. However, according to tradition, they pledged to fight as well, with Sa'd bin 'Ubada declaring, "If you order us to plunge our horses into the sea, we would do so."<ref></ref> However, the Muslims still hoped to avoid a pitched battle and continued to march towards Badr. | |||

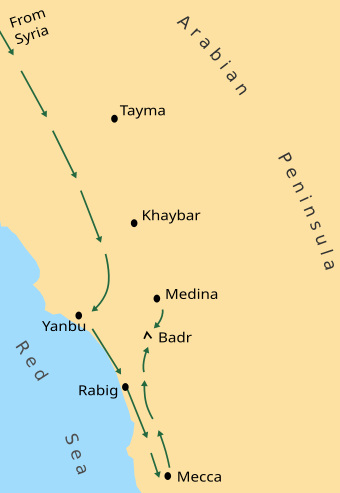

| ] to protect his caravan from the ] to ], the route taken by ] (Abu Jahl) from Mecca to ] and the route taken by Muhammad and the Muslims from Medina to Mecca. ]]Muhammad was able to gather an army of 313–317 men. Sources vary upon the exact number, but the generally accepted number is 313. This army consisted of 82 ], 61 men from the ] and 170 men from the ].<ref name=":0" /> They were not well-equipped for a major conflict nor prepared. They only had two horses, and those belonged to ] and ]. The entire army had 70 camels, meaning that they had one camel for two to three men to ride alternatively.<ref name="Lings, pp. 138–139">Lings, pp. 138–139</ref><ref name=":0" /> Muhammad shared a camel with ] and Marthad ibn Abi Marthad al-Ghanawi.<ref name=":0" /> The guardianship and administration of ] was entrusted with ], but later with ].<ref name=":0" /> Muhammad handed a white standard to ].<ref name=":0" /> The army was divided into two battalions: one of the 82 Muhajirun and the other of the 231 ].<ref name=":0" /> The flag of the Muhajirun was carried by 'Ali ibn Abu Talib, while that of the Ansar was carried by ].<ref name=":0" /> az-Zubayr commanded the right flank, while al-Miqdad commanded the left.<ref name=":0" /> And the rear of the army was commanded by Qays bin Abi Sa'sa'ah. | |||

| With Muhammad in the lead, the army marched out along the main road to Mecca, from the north.<ref name=":0" /> At Safra', he dispatched Basbas al-Juhani and 'Adi al-Juhani to scout for the Quraish. The future Caliph ] stayed behind to care of his sick wife ], the daughter of Muhammad, who later died from illness.<ref>{{cite web|title=Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 4, Book 53, Number 359|url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/053.sbt.html#004.053.359|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100720142403/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/053.sbt.html|archive-date=20 July 2010|access-date=16 September 2010|publisher=Usc.edu}}</ref> ] also could not join the battle, as he was still not a free man.<ref>{{cite web|date=16 September 2002|title=Witness-pioneer.org|url=http://www.witness-pioneer.org/vil/Books/SM_tsn/ch4s5.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100205021747/http://www.witness-pioneer.org/vil/Books/SM_tsn/ch4s5.html|archive-date=5 February 2010|access-date=19 March 2010|publisher=Witness-pioneer.org}}</ref> | |||

| By March 15 both armies were about a day's march from Badr. Several Muslim warriors who had rode ahead of the main column captured two Meccan water carriers at the Badr wells. Expecting them to say they were with the caravan, the Muslims were horrified to hear them say they were with the main Quraishi army. Convinced they were lying, the Muslims began to beat them until the prisoners said they were with the caravan. However, according to tradition Muhammad put a stop to this.<ref> | |||

| </ref> Some traditions also say that, upon hearing the names of all the Quraishi nobles accompanying the army, he exclaimed "Mecca hath thrown unto you the best morsels of her liver."<ref>Martin Lings, Page 142</ref> The next day Muhammad ordered a forced march to Badr and arrived before the Meccans. | |||

| === Qurayshi advance toward Badr === | |||

| The Badr wells were located on the gentle slope on the eastern side of a valley called "Yalyal". The western side of the valley was hemmed in by a large hill called 'Aqanqal. When the Muslim army arrived from the east, Muhammad initially chose to form his army at the first well he encountered, but he was apparently persuaded by one of his soldiers to move his army westwards and occupy the well closest to the Quraishi army. Muhammad then gave the order to fill in the remaining wells, so that the Meccans would have to fight the Muslims for the sole remaining water source. | |||

| All of the clans of the Quraish except the ] quickly assembled an excited army of around 1300 men, 100 horses and a large number of camels. Moving swiftly towards ], they passed the valleys of 'Usfan, Qadid and al-Juhfah. At al-Juhfah, another messenger from Abu Sufyan informed them of the safety of their merchandise and wealth. Upon receiving this message, the Makkan army expressed delight and showed a desire to return home. ] was not interested in returning and insisted on proceeding to Badr, and holding a ] there to show the Muslims and the surrounding tribes that they were superior. Despite Abu Jahl's threat and insistence, the ], numbering around 300, broke away from the army and returned to Mecca, on the advice of ]. Muhammad's clan, the ], also attempted to break away but were threatened by Abu Jahl to stay.<ref name=":0" /> Many of the Qurayshi nobles, including ], ], '], and ], joined the Meccan army. Their reasons varied: some were out to protect their financial interests in the caravan; others wanted to avenge Ibn al-Hadrami, a guard killed in one of the caravan ambushes at ]; finally, a few must have wanted to take part in what was expected to be an easy victory against the Muslims.<ref>Martin Lings, pp. 139–140.</ref> Amr ibn Hishām is described as shaming Umayyah ibn Khalaf into joining the expedition.<ref>{{cite web|title=Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 5, Book 59, Number 286|url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/059.sbt.html#005.059.286|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100816202325/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/059.sbt.html|archive-date=16 August 2010|access-date=16 September 2010|publisher=Usc.edu}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Plans of action === | ||

| ]'': The approach of the Meccan army over 'Aqanqal.]] | |||

| ''<blockquote>" Arabs will hear how we marched forth and of our mighty gathering, and they will stand in awe of us forever."'' '''- Amr ibn Hashim'''</blockquote> | |||

| ==== Muslim council near Badr ==== | |||

| By contrast, while little is known about the progress of the Quraishi army from the time it left Mecca until its arrival just outside Badr, several things are worth noting: although many Arab armies brought their women and children along on campaigns both to motivate and care for the men, the Meccan army did not. Also, the Quraish apparently made little or no effort to contact the many ] allies they had scattered throughout the Hijaz.<ref>Lings, Page 154.</ref> Both facts suggest the Quraish lacked the time to prepare for a proper campaign in their haste to protect the caravan. | |||

| ] at ]]] | |||

| Muhammad held a ] to review the situation and decide on a plan-of-action. According to some Muslim scholars, the following verses of ], ], were revealed in lieu of some Muslims fearing the encounter. ] was the first to speak at the meeting and he reassured Muhammad.<ref name=":0" /> '] was next. Then, ] got up and said:<ref name=":0" /><ref name="The Message">{{cite book|last1=Subhani|first1=Ayatullah Jafar|title=The Message|publisher=Islamic Seminary Publications|location=Karachi, Pakistan|chapter=30}}</ref><blockquote>"O ]! Proceed where Allah directs you to, for we are with you. We will not say as the ] said to ]: "Go you and your Lord and fight and we will stay here;" rather we shall say: "Go you and your Lord and fight and we will fight along with you." By Allah! If you were to take us to Birk al-Ghimad, we will still fight resolutely with you against its defenders until you gained it."<ref name=":0" /><ref name="The Message" /></blockquote>Muhammad then praised him and supplicated for him, but the three who had spoken were of the ], who only constituted around one-third of the Muslim men in ]. Muhammad wanted the opinion of the ], who were not committed to fighting beyond their territories in the ]. Muhammad then indirectly asked the Ansar to speak, which ] understood and asked for permission to speak. Muhammad immediately gave him permission to speak and Sa'd said:<ref name=":0" /><blockquote> | |||

| When the Quraishi reached Juhfah, just south of Badr, they recieved a message from Abu Sufyan telling them the caravan was safely behind them, and that they could therefore return to Mecca.<ref>Lings, Page 142.</ref> At this point, according to Karen Armstrong, a power struggle broke out in the Meccan army. Amr ibn Hisham wanted to continue, but several of the clans present, including ] and ], promptly went home. Armstrong suggests they may have been concerned about the power the Hisham would gain from crushing the Muslims. A contingent of ], hesitant to fight their own clansmen, also left with them.<ref>Armstrong, Page 174</ref> Despite these losses, Hisham was still determined to fight, boasting "We will not go back until we have been to Badr." During this period, Abu Sufyan and several other men from the caravan joined the main army.<ref>Lings, Pages 142-143.</ref> | |||

| "O ]! We believe in you and we bear witness to what you have brought is the Truth. We give you our firm pledge of obedience and sacrifice. We will obey you most willingly in whatever you command us, and by Allah, Who has sent you with the Truth, if you were to ask us to throw ourselves into the sea, we will do that most readily and not a man of us will stay behind. We do not deny the idea of encounter with the enemy. We are experienced in war and we are trustworthy in control. We hope that Allah will show you through our hands those deeds of bravery which will please your eyes. Kindly lead us to the battlefield in the Name of Allah."<ref name=":0" /></blockquote>Muhammad, impressed with his loyalty and spirit of sacrifice, ordered the march towards Badr to continue.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| === |

====Muslim plan of action==== | ||

| By Sunday, 11 March (15 Ramadan), both armies were about a day's march from Badr. Muhammad and Abu Bakr had conducted a scouting operation and managed to locate the camp of the Quraish. They came across an old bedouin nearby from whom they managed to find out the exact strength of their army and their location. In the evening, Muhammad dispatched 'Ali, az-Zubayr and ] to scout for the Makkans. They captured two Meccan water-bearers at the wells of Badr. Expecting them to say they were with the caravan, the Muslims were horrified to hear them say they were with the main Quraishi army.<ref name="book19">{{cite web |url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/muslim/019.smt.html#019.4394 |title=Sahih Muslim: Book 19, Number 4394 |publisher=Usc.edu |access-date=16 September 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100820122650/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/muslim/019.smt.html#019.4394 |archive-date=20 August 2010 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Unsatisfied with their answer, while Muhammad was praying, some of the Muslims beat the two boys into lying and Muhammad strictly condemned this action later. Muhammad then extracted the details of the Makkans from the boys. The next day Muhammad ordered a march to Badr and arrived before the Meccans.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| When the Muslim army arrived from the east, Muhammad initially chose to encamp at the first well he encountered. al-Hubab ibn al-Mundhir, however, asked him if this choice was from divine instruction or Muhammad's own opinion. When Muhammad responded in the latter, Hubab suggested that the Muslims occupy the well closest to the Quraishi army, and block off or destroy the other ones. Muhammad accepted this decision and the plan was carried out at midnight.<ref name=":0" /> Muhammad had also given strict orders to not begin an attack without his sole permission.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| At dawn on March 17, the Quraish broke camp and marched into the valley of Badr. It had rained the previous day and they struggled to move their horses and camels up the hill of 'Aqanqal (Sources say the sun was already up by the time they reached the summit).<ref>Armstrong, Page 175.</ref> After they descended from 'Aqanqal, the Meccans set up another camp inside the valley. While they rested, they sent out a scout, ] to reconoiter the Muslim lines. Umayr reported that Muhammad's army was small, and that there were no other Muslim reinforcements which might join the battle.<ref>Lings, Pages 143-144.</ref> However, he also predicted extremely heavy Quraishi casualties in the event of an attack (One hadith refers to him seeing "the camels of laden with certain death").<ref>Armstrong, Pages 174-175.</ref> This further demoralized the Quraish, as Arab battles were traditionally low-casualty affairs, and set off another round of bickering among the Quraishi leadership. However, according to Muslim traditions Amr ibn Hashim quashed the remaining dissent by appealing to the Quraishi's sense of honor and demanding that they fulfill their blood vengeance.<ref>Lings, Pages 144-146.</ref> | |||

| Muhammad spent the whole night of 12 March (16 Ramadan) praying near a tree. The Muslim army enjoyed a refreshing night of sleep, again believed by Muslims, to be a blessing from Allah.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| The battle started with champions from both armies emerging to engage in combat. Three of the Ansar emerged from the Muslim ranks, only to be shouted back by the Meccans, who were nervous about starting any unnecessary feuds and only wanted to fight the Quraishi Muslims. So the Muslims sent out Ali, Ubaydah, and Hamzah. The Muslims dispatched the Meccan champions in a three-on-three melee, although Ubaydah was mortally wounded.<ref></ref> | |||

| ====Meccan plan of action==== | |||

| Now both armies began firing arrows at each other. Two Muslims and an unknown number of Quraish were killed. Before the battle started, Muhammad had given orders for the Muslims to attack with their ranged weapons, and only engage the Quraish with ] weapons when they advanced.<ref></ref> Now he gave the order to charge, throwing a handful of pebbles at the Meccans in what was probably a traditional Arabian gesture while yelling "Defaced be those faces!"<ref>Armstrong, Page 176. Lings, Page 148.</ref> The Muslim army yelled ''"Yā manṣūr amit!"''<ref>"O thou whom God hath made victorious, slay!"</ref> and rushed the Quraishi lines. The sheer force of the Muslim attack can be seen in several Quranic verses, which refer to thousands of angels descending from Heaven at Badr to slaughter the Quraish.<ref>Lings, Pages 148. Quran: Sura 3:123-125.</ref> It should be noted that early Muslim sources take this account literally, and there are several hadith where Muhammad discusses the Angel ] and the role he played in the battle. In any case the Meccans, understrength and unenthusiastic about fighting, promptly broke and ran. The battle itself only lasted a few hours and was over by the early afternoon.<ref>Armstrong, Page 176.</ref> | |||

| While little is known about the progress of the Quraishi army from the time it left Mecca until its arrival just outside Badr, several things are worth noting: although many Arab armies brought their women and children along on campaigns both to motivate and care for the men, the Meccan army did not. The Quraish apparently made little or no effort to contact the many allies they had scattered throughout the ].<ref>Lings, p. 154.</ref> Both facts suggest the Quraish lacked the time to prepare for a proper campaign in their haste to protect the caravan. Besides, it is believed they expected an easy victory. | |||

| Since Muhammad's army had either destroyed or taken all the wells in the city, a few Makkans approached the well controlled by Muslims to draw out water. All were shot except ], who later accepted ]. At midnight on 13 March (17 Ramadan), the Quraish broke camp and marched into the valley of Badr. ] made a survey of the Muslim position and reported 300 men keen on fighting to the last man.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1">Lings, pp. 143–144.</ref><ref>Armstrong, pp. 174–175.</ref> After another scouting mission, he reported that neither were the Muslims going to be reinforced, nor were they planning any ambushes.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> This further demoralized the Quraish, as Arab battles were traditionally low-casualty affairs, and set off another round of bickering among the Quraishi leadership. However, according to Arab traditions Amr ibn Hishām quashed the remaining dissent by appealing to the Quraishis' sense of honor and demanding that they fulfill their blood vengeance.<ref>Lings, pp. 144–146.</ref> | |||

| ===Important participants=== | |||

| ]'': The Meccan army sends out its champions.]] | |||

| === |

===Duels=== | ||

| The battle began with al-Aswad bin 'Abdul-Asad al-Makhzumi, one of the men from Abu Jahl's clan, the ], swearing that he would drink from the well of the Muslims or otherwise destroy it or die for it. In response to his cries, ], one of Muhammad's uncles, came out and they began fighting in a duel. Hamza struck al-Aswad's leg before dealing him another blow that killed him. Seeing this, three men protected by armor and shields, ], alongside his brother, ] and son, al-Walid ibn 'Utbah, emerged from the Makkan ranks. Three of the Madani ] emerged from the Muslim ranks, only to be shouted back by the Meccans, who were nervous about starting any unnecessary feuds and only wanted to fight the Muhajirun, keeping the dispute within the tribe. So Hamza approached and called on ] and ] to join him. The first two duels between 'Ali and al-Walid and Hamza and Shaybah were quick with both managing to kill their opponents swiftly. After the fight between Ali and Walid, Hamza looked at 'Ubaydah to find him seriously wounded. He then fell upon and killed Shaybah. Ali and Hamza then carried Ubaydah back into the Muslim lines. He died later due to a disease.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Razwy|first1=Sayed Ali Asgher|title=A Restatement of the History of Islam & Muslims|pages=136–137}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{cite book|last1=Muir|first1=Sir William|title=The Life of Mohammed|date=1877|location=London}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Glubb|first1=Sir John|title=The Great Arab Conquests|date=1963}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> A shower of arrows from both sides followed these duels and this was followed by several other duels, most of which were won by the Muslims.<ref name=":0" /> The Makkans now took the offensive and charged upon the Muslim lines.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| (Listed in alphabetical order)<br> | |||

| === Makkan charge and Muslim counter-attack === | |||

| ] (Meccan Commander, Killed)<br> | |||

| As the Makkans charged upon the Muslims, Muhammad kept asking Allah, stretching his hands toward the ]:<blockquote>"O Allah! Should this group (of Muslims) be defeated today, You will no longer be worshipped."</blockquote>Muhammad kept reciting his prayer until his cloak fell off his shoulders, at which point Abu Bakr picked it up and put it back on his shoulders and said:<blockquote>"O Prophet of Allah, you have cried out enough to your Lord. He will surely fulfil what He has promised you."</blockquote>Muhammad gave the order to carry out a counterattack against the enemy now, throwing a handful of pebbles at the Makkans in what was probably a traditional Arabian gesture while yelling "Defaced be those faces!"<ref name="armstrong176">Armstrong, p. 176.</ref><ref name="lings148">Lings, p. 148.</ref> or "Confusion seize their faces."<ref name=":0" /> The Muslim army yelled in reply, ''"Yā manṣūr amit!"'' meaning "O thou whom God hath made victorious, slay!" and rushed the Qurayshi lines. The Makkans, understrength and unenthusiastic about fighting, promptly broke and ran. Muslims attribute their fear of fighting and fleeing from the battlefield to divine intervention, with the Qur'an stating in Chapter 8, verse 12, that Allah inspired angels to strengthen those who have believed, and cast terror into the hearts of those who disbelieved. The battle itself only lasted a few hours and was over by early afternoon.<ref name="armstrong176" /> The Qur'an describes the force of the Muslim attack in many verses, which refer to thousands of angels descending from Heaven at Badr to terrify the Quraish.<ref name="lings148" /><ref>Quran: ] {{cite Quran|3|123|end=125|t=y|tn=y|style=nosup|expand=no|quote=Allah had helped you at Badr, when ye were a contemptible little force; then fear Allah; thus May ye show your gratitude. Remember thou saidst to the Faithful: "Is it not enough for you that Allah should help you with three thousand angels (Specially) sent down? "Yea, – if ye remain firm, and act aright, even if the enemy should rush here on you in hot haste, your Lord would help you with five thousand angels Making a terrific onslaught.}}</ref> It also describes how ], the Leader of the ], mentioned to have taken the form of ], fled the battlefield upon seeing the angels.<ref name=":0" /> Muslim sources take this account literally, and there are several ] where Muhammad discusses the Angel ] and the role he played in the battle.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ] · ] (Killed) · ] · ] (Killed) · ] · ] (Killed) · ] (Killed) · ] (Killed) · ] (Killed) · ] · ] (Prisoner) | |||

| <br style="clear:both;"> | |||

| ====Muslims==== | |||

| ]'': The Muslim army sends out its champions.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| '''+''' Indicates ] | |||

| ] (Muslim Commander, Prophet of Islam)<br> | |||

| ] · ] (Future Caliph) · ] · ] · ] (Future Caliph) · ]'''+''' · ] · ] · ] · ] · ]'''+''' (Killed) · ]'''+''' (Killed) · ] (Died) · ] (Killed) · ] (Future Caliph) | |||

| == Aftermath == | == Aftermath == | ||

| ] | |||

| ===Casualties and prisoners=== | |||

| ===Imprisonment of captives and their ransom=== | |||

| ] reports that on the Muslim side six Quraishi Muslims and eight Ansar were killed, and that fifty Meccans were killed with forty-three taken prisoner.{{fact}} ] lists Meccan losses as seventy dead and seventy captured,<ref></ref> which would be 15%-16% of the Quraishi army, unless the actual number of Meccan troops present at Badr was significantly lower, in which case the perecentage of troops lost would have been higher. Muslim losses are commonly listed at fourteen killed, about 4% of their engaged forces.<ref>Lings, Page 148.</ref> Sources do not indicate the number of wounded on either side, and the major discrepencies between the casualties totals on each side suggests that the fighting was extremely brief and that most of the Meccans were killed during the retreat. | |||

| Three days after the battle,<ref name=":0" /> ] left ] for ]. As far as the treatment of prisoners was concerned, ] was of the opinion that they should be ransomed, since they were all of their own kin. '] argued against this, saying that there is no notion of blood relationships as far as Islam is concerned, and that all the prisoners should be executed, and that everyone should execute him who is closest to him by blood. '] should kill his brother ], ] should behead his brother '], and that he himself would kill someone close to him. Muhammad accepted Abu Bakr's suggestion to ransom the captives.{{Sfn|Rippin|2009|p=213}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Nomani|first=Shibli|author-link=Shibli Nomani|translator=Zafar Ali Khan|translator-link=Zafar Ali Khan|title=Al-Farooq: the life of Omar the Great|url=https://archive.org/details/AlFarooqEnglishByShaykhAllamahShibliNomanir.a_201601|volume=I|page=|year=1939|publisher=Sh. Muhammad Ashraf|location=Kashmiri Bazar, Lahore}}</ref> Some 70 prisoners were taken captive and are noted to have been treated humanely, including a number of Quraysh leaders.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/hadith/bukhari/052-sbt.php| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121013003022/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/hadith/bukhari/052-sbt.php| url-status=dead| archive-date=13 October 2012| title=Sahih Bukhari, Volume 4, Book 52, Number 252| quote=Narrated Jabir bin 'Abdullah: When it was the day (of the battle) of Badr, prisoners of war were brought including Al-Abbas who was undressed. The Prophet looked for a shirt for him. It was found that the shirt of 'Abdullah bin Ubai would do, so the Prophet let him wear it. That was the reason why the Prophet took off and gave his own shirt to 'Abdullah. (The narrator adds, "He had done the Prophet some favor for which the Prophet liked to reward him.")| access-date=20 September 2015}}</ref><ref name="The Life of Mahomet">{{cite book|last1=Muir|first1=William|title=The Life of Mahomet|date=1861|publisher=Smith, Elder and Co.|location=London|page=122|edition=Volume 3|url=https://archive.org/stream/lifemahometandh02muirgoog#page/n138/mode/2up|access-date=26 February 2015}}</ref> Most of the prisoners were released upon payment of ransom and those who were literate were released on the condition that they teach ten persons how to read and write and this teaching was to count as their ransom.<ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FLoUAAAAYAAJ&q=teach | title=The Life of Mahomet: With Introductory Chapters on the Original Sources for the Biography of Mahomet, and on the Pre-Islamite History of Arabia |author= William Muir |volume= 1 |page=ix |year= 1861 |location= London |publisher=Smith, Elder and Co | isbn=9780524073797 | access-date=19 January 2016}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.al-islam.org/life-muhammad-prophet-sayyid-saeed-akhtar-rizvi/battles|title=Battles|date=18 October 2012|website=www.al-islam.org}}</ref> | |||

| ] wrote of this period: | |||

| During the course of the fighting, the Muslims took a number of Meccan Quraish prisoner. Their fate sparked an immediate controversy in the Muslim army.<ref>Quran:Sura 8:67-70. The initial fear was that the Meccan army might rally and that the Muslims couldn't spare any men to guard the prisoners (a similar incident appears in the ] ]</ref> | |||

| {{quote|In pursuance of Mahomet's commands, the citizens of Medîna, and such of the Refugees as possessed houses, received the prisoners, and treated them with much consideration. "Blessings be on the men of Medina!" said one of these prisoners in later days; "they made us ride, while they themselves walked: they gave us wheaten bread to eat when there was little of it, contenting themselves with dates. It is not surprising that when, some time afterwards, their friends came to ransom them, several of the prisoners who had been thus received declared themselves adherents of Islam...Their kindly treatment was thus prolonged, and left a favourable impression on the minds even of those who did not at once go over to Islam"<ref name="The Life of Mahomet" />|], ''The Life of Mahomet''}} | |||

| Sad and Umar were in favor of killing the prisoners, but Abu Bakr argued for clemency, and Muhammad eventually sided with Abu Bakr. Most prisoners were spared, either because of clan relations (One was Muhammad's son-in-law), desire for ransom, or the hope that they would later convert to Islam. (In fact, several later would)<ref>Lings, Pages 149-151</ref> | |||

| ===Casualties=== | |||

| At least two high-ranking Meccans, ] and Umayyah, were executed after the battle, and two other Quraish who had dumped a bucket of sheep excrement over Muhammad during his days at Mecca were also killed during the return to Medina.<ref>Lings, Pages 149-152</ref> In the case of Umayyah, his former slave ] was so intent on killing him that he even stabbed one of the Muslims guarding Ummayah.<ref>.</ref> | |||

| Despite scholars estimating Meccan casualties at around 70, only the names of the more prominent ones are known. However, the names of the 14 Muslims who were killed during the course of the war or later (due to injuries sustained during the war) are all known.], ] beheading ] in the presence of Muhammad and his ].]] | |||

| ==== Meccan casualties ==== | |||

| Shortly before he departed Badr, Muhammad also gave the order for over twenty of the dead Quraishis to be thrown into the well at Badr.<ref>.</ref> Multiple hadiths refer to this incident, which was apparently a major cause for outrage among the Quraish of Mecca. Shortly thereafter, several Muslims who had been recently captured by allies of the Meccans were brought into the city of Mecca and executed in revenge for the defeat.<ref></ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Well-known Meccans who were killed during the battle included ], ], '], ], al-Walid ibn 'Utbah, al-Aswad bin and 'Abdul-Asad al-Makhzumi. ] and ] were also killed, though the circumstances of their deaths are unclear. According to some sources the last two were killed during fighting in the field of battle at Badr and subsequently buried in a pit,<ref name=":32" /><ref>]: Volume 1, Book 9, Number 499</ref><ref>Al Tabaqat-al-Kubra, Muhammad Ibn Sa'd, Volume 2, p. 260, ghazwatul Badr, Darul Ihya'it-Turathil-'Arabi, Beirut, Lebanon, First Edition, (1996)</ref> while ] writes that these two were taken as prisoners and subsequently executed by ].<ref name=":0"/><ref name=":32">]: Volume 1, Book 4, Number 241</ref> | |||

| ==== Muslim casualties ==== | |||

| According to the traditional ] (similar to ]) any Meccans related to those killed at Badr would feel compelled to take vengeance against members of the tribe who had killed their relatives. For example, ]'s wife ], whose brother was killed at Badr, swore to eat the liver of Hamzah, who killed her brother. She later did so after he had been killed at the Battle of Uhud. Likewise, there was also a heavy desire on the Muslim side for vengeance, as they had been persecuted and tortured by the Quraishi Meccans for years. Generally, the Muslims took better care of their prisoners, even going so far as to house them with Muslim families in Medina. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |+Muslims casualties at Badr | |||

| |- | |||

| |Haritha bin Suraqa al-Khazraji | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|حارثہ بن سراقة الخزرجي}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Zish Shamalain bin 'Abdi 'Amr al-Muhajiri | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|ذو الشمالين بن عبد عمر المهاجري}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Rafi' bin al-Mu'alla al-Khazraji | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|رافع بن المعلاء الخزرجي}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Sa'd bin Khaythama al-Awsi | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|سعد بن خيثمة الأوسي}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Safwan bin Wahb al-Muhajiri | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|صفوان بن وهب المهاجري}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |'Aaqil bin al-Bukayr al-Muhajiri | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|عاقل بن البكير المهاجري}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |'Ubayda bin al-Harith al-Muhajiri | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|عبيدة بن الحارث المهاجري}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |'Umayr bin al-Humam al-Khazraji | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|عمير بن الحمام الخزرجي}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |'Umayr bin Abu Waqqas al-Muhajiri | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|عمير بن أبو وقاس المهاجري}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |'Awf bin al-Harith al-Khazraji | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|عوف بن الحارث الخزرجي}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Mubashir bin 'Abdul Mundhir al-Awsi | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|مبشر بن عبدالمنذر الأوسي}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Mu'awwidh bin al-Harith al-Khazraji | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|معوذ بن الحارث الخزرجي}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Mihja' bin Salih al-Muhajiri | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|مهجاء بن صالح المهاجري}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Yazid bin al-Harith bin Fushum al-Khazraji | |||

| |{{Lang|ar|يزيد بن الحارث بن فصحم الخزرجي}} | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Implications=== | === Implications === | ||

| The Battle of Badr was extremely influential in the rise of two men who determined the course of Arabian history in the next century. The first was ], who was transformed overnight from a Meccan outcast into the leader of a new community and ] at ]. Marshall Hodgson adds that Badr forced the other Arabs to "regard the Muslims as challengers and potential inheritors to the prestige and the political role of the ." Shortly thereafter he expelled the ], one of the Jewish tribes in Medina for assaulting a Muslim woman which led to their expulsion for breaking the peace treaty. The tribe is also known for having threatened Muhammad's political position. At the same time ], Muhammad's chief opponent in Medina, found his own position seriously weakened. He was only able to mount limited challenges to Muhammad.<ref>Hodgson, pp. 176–178.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The other major beneficiary of the Battle of Badr was ], safely away from the battle leading the caravan. The death of ], as well as many other Quraishi nobles,<ref>Including the elderly ], who was not at Badr but died within days of the army's return.</ref> gave Abu Sufyan the opportunity, almost by default, to become chief of the ]. As a result, when Muhammad ] six years later, it was Abu Sufyan who helped negotiate its peaceful surrender. Abu Sufyan subsequently became a high-ranking official in the Muslim Empire, and his son ] later went on to found the ]. | |||

| The Battle of Badr was extremely influential in the rise of two men who would determine the course of history on the Arabian peninsula for the next century. The first was Muhammad, who was transformed overnight from a Meccan outcast into a major leader. According to Karen Armstrong, "for years Muhammad had been the butt of scorn and insults, but after this spectacular and unsought success everybody in Arabia would have to take him seriously."<ref>Armstrong, Page 176.</ref> Marshall Hodgson also adds that Badr forced the other Arabs to "regard the Muslims as challengers and potential inheritors to the prestige and the political role of the ." The victory at Badr also allowed Muhammad to consolidate his own position at Medina. Shortly thereafter, one of the Jewish tribes at Medina who had been threating his political position, the ], was expelled. At the same time ], Muhammad's chief political opponent at Medina, found his own position seriously weakened. Henceforth, he would only be able to mount limited challenges to the Muslims.<ref>Hodgson, Pages 176-178.</ref> | |||

| ] had performed especially well during the battle of Badr, killing one of the leaders and a number of high-ranking officials of the Quraysh. In retaliation, the Quraysh put a bounty on his head. ] killed him at ] and the Quraysh followed by publicly mutilating Hamza.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cook |first=David |url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/ocm70867078 |title=Martyrdom in Islam |date=2007 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-85040-7 |series=Themes in islamic history |location=Cambridge, UK ; New York |pages=24-25 |oclc=ocm70867078}}</ref> | |||

| The other major beneficiary of the Battle of Badr was ]. The death of Amr ibn Hashim, as well as many other Quraishi nobles<ref>Including the elderly ], who was not at Badr but died within days of the army's return.</ref> gave Abu Sufyan the opportunity, almost by default, to become chief of the ]. As a result, when Muhammad marched into Mecca six years later, it was Abu Sufyan who helped negotiate its peaceful surrender. Abu Sufyan subsequently became a high-ranking official in the Muslim Empire, and his son ] would later defeat Muhammad's son-in-law ] and go on to found the ]. | |||

| In later days, the battle of Badr became so significant that ] included a complete name-by-name roster of the Muslim army in his biography of Muhammad. In many hadiths, veterans who fought at Badr are identified as such as a formality, and they may have even received a stipend in later years.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/059.sbt.html#005.059.357 |title=Sahih al-Bukhari: Volume 5, Book 59, Number 357 |publisher=Usc.edu |access-date=16 September 2010| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100816202325/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/059.sbt.html| archive-date= 16 August 2010 | url-status=live}}</ref> The death of the last of the Badr veterans occurred during the ].<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100816202325/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/059.sbt.html#005.059.358 |date=16 August 2010 }}.</ref> | |||

| ==Historical sources== | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| === Badr in the Quran === | |||

| {{Quote box|Indeed, there was a sign for you in the two armies that met in battle—one fighting for the cause of Allah and the other in denial. The believers saw their enemy twice their number. But Allah supports with His victory whoever He wills. Surely in this is a lesson for people of insight. Indeed, Allah made you victorious at Badr when you were vastly outnumbered. So be mindful of Allah, perhaps you will be grateful.|], '']'' ], 3:13 and 3:123 (tr. ])<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.islamawakened.com/quran/3/st69.htm|title=al-Imran (The Family of Imran, The House of Imran) at IslamAwakened.com|website=www.islamawakened.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.al-islam.org/alphabetical-index-holy-quran/battle-badr|title=Battle Of Badr|date=28 June 2016|website=www.al-islam.org}}</ref>| width = 500px}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In the ], the battle is referred to as '''Yawm al-Furqan''' ({{Langx|ar|يَوْمُ الْفُرْقَانْ|lit=The Day of the Criterion}}; {{IPA|ar|jawm'ul fur'qaːn}}). The story of the Battle of Badr has been passed down in Islamic history throughout the centuries, before being combined in the multiple ] that exist today. It is mentioned in the Quran, and all knowledge of the battle comes from traditional Islamic accounts, recorded and compiled sometime after the battle. There is little evidence beside these and there are no written descriptions of the battle prior to the 9th century, and as such, the historicity and authenticity of the battle are debated by contemporary historians.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8oYLyS_pIAgC&pg=PA23|title=The Development of Exegesis in Early Islam: The Authenticity of Muslim Literature from the Formative Period|first=Herbert|last=Berg|date=16 October 2000|publisher=Psychology Press|isbn=9780700712243 |via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Al-Anfal}} | |||

| "Badr" has become popular among Muslim armies and paramilitary organizations. "]" was used to describe ]'s offensive in the 1973 ] as well as ]'s actions in the 1999 ]. ] against Iraq in the late 1980s were also named after Badr.<ref name=wright89>{{cite book|last=Wright|first=Robin|title=In the name of God: The Khomeini decade|year=1989|publisher=Simon & Schuster|location=New York|isbn=9780671672355|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/innameofgodkhome00wrig/page/133}}</ref> During the ], the rebel leadership stated that they selected the date of the assault on Tripoli to be the 20th of Ramadan, marking the anniversary of the Battle of Badr.<ref>Laub, Karin (21 August 2011). . ] (via '']''). Retrieved 21 August 2011.</ref> | |||

| The Battle of Badr is one of the few battles explicitly discussed in the ]. It is even mentioned by name in ] 3:123, as part of a comparison with the Battle of Uhud. | |||

| The Battle of Badr was featured in the 1976 film '']'', the 2004 animated movie '']'', the 2012 TV series '']'' and the 2015 animated movie ''].'' | |||

| <blockquote>''Allah had helped you at Badr, when ye were a contemptible little force; then fear Allah; thus May ye show your gratitude. Remember thou saidst to the Faithful: "Is it not enough for you that Allah should help you with three thousand angels (Specially) sent down? "Yea, - if ye remain firm, and act aright, even if the enemy should rush here on you in hot haste, your Lord would help you with five thousand angels Making a terrific onslaught.'' '''Quran: Sura 3:123-125'''</blockquote> | |||

| According to Yusuf Ali, the term "gratitude" may be a reference to discipline. At Badr, the Muslim forces had allegedly maintained firm discipline, whereas at Uhud they broke ranks to pursue the Meccans, allowing Meccan cavalry to flank and route their army. The idea of Badr as a ], an Islamic miracle, is mentioned again in the same surah. | |||

| <blockquote>''"There has already been for you a Sign in the two armies that met (in combat): One was fighting in the cause of Allah, the other resisting Allah; these saw with their own eyes Twice their number. But Allah doth support with His aid whom He pleaseth. In this is a warning for such as have eyes to see."'' '''Quran: Sura 3:13'''</blockquote> | |||

| Badr is also the subject of the controverisal Sura 8: '']'', which details military conduct and operations. Though the Sura does not name Badr, it describes the battle several times, including a reference to the pre-battle debate in the Muslim army over whether to pursue the caravan or fight the Meccan army, as well as verses that highlighted both the chance encounter of the battle (both sides had blundered into each other), as well as the underestimation of both the size of Meccan army by the Muslims and the fierceness of the Muslim army by the Meccans. "Al-Anfal" means "the spoils" and is a reference to the post-battle discussion in the Muslim army over how to divide up the plunder from the Quraishi army. | |||

| === Traditional Muslim accounts === | |||

| ] | |||

| Virtually all contemporary knowledge of the Battle of Badr comes from traditional Islamic accounts, both ] and biographies of Muhammad, written down decades after the battle. There are several reasons for this: first, many Arabs of the Arabian peninsula were ] (Including Muhammad) and oral traditions were the default method of passing on information. By the time the Armies of Islam had conquered the more literate Arabs of ] and ], practically all Quraish had been converted to Islam, eliminating any chance of a non-Muslim account of the battle. Second, as Muslim hadith compilations were assembled, the original manuscripts became redundant and were destroyed at what Hugh Kennedy called a "depressingly high" rate.<ref>{{Book_reference|Author=Kennedy, Hugh |Title=The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphate|Publisher=]|Year=1985|ID=ISBN 0-5824-0525-4}}. Page 355.</ref> Finally, the Muslims killed at Badr are regarded as ] by most pious Muslims, which has most likely stymied many serious attempts at archeological excavation at Badr. | |||

| ==Cultural implications and references== | |||

| In later days having fought Badr became so significant that ] included a complete name-by-name roster of the Muslim army in his biography of Muhammad. In many hadiths, individuals who fought at Badr are identified as such as a formality, and they may have even received a stipend in later years.<ref></ref> The death of the last of the Badr veterans occurred during the ].<ref>.</ref> According Karen Armstrong, one of the most lasting impacts of Badr may be the fasting during ], which the Muslims initially began as a way of commemorating the victory at Badr.<ref>Armstrong, Page 179.</ref> | |||

| ===Modern military references=== | |||

| Because of its place in Muslim history and connotations of victory-against-all odds, the name "Badr" has become popular among both Muslim armies and paramilitary organizations. "]" was used to describe ]'s role in the 1973 ] and ]'s actions in the 1999 ]. In Iraq, the armed wing of the ] calls itself the ]. | |||

| ===Film=== | |||

| The Battle of Badr was also featured on the big screen in the 1976 film '']''. Although the film was reasonably faithful to the event, it made some notable changes: | |||

| * The Quraishi army was depicted as having women in tow, when the women were noticeably absent. | |||

| * Abu Sufyan refused to take part in the battle. | |||

| * The champion combat consisted of three one-on-one fights, instead of a three-on-three melee. | |||

| * Neither Muhammad nor Ali were shown, though Ali's sword was shown. (This was because many Muslims believe that images of the two are forbidden) As a result, Hamza became the nominal commander of the army. | |||

| * The Quraishi army was extremely aggressive, launching a massive charge on the Muslim lines which in real life might have routed the smaller army. | |||

| * Amr ibn Hashim and Umayyah were killed in battle instead of being executed afterwards. In fact, all post-battle executions were absent from the film, which presented a highly-sterlized version of the event. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| ==Footnotes== | ==Footnotes== | ||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| Instructions for adding a footnote: | |||

| NOTE: Footnotes in this article use names for internal cross-reference, but display numbers. Please see ] for details. | |||

| 1) Assign your footnote a unique name, for example Willard_28. | |||

| 2) Take note of the highest-numbered footnote that was in the article prior to your cite insertion. For example, if the list of footnotes went from 1 to 67, you should note the number "67" as the highest. | |||

| 2) Add the text {{Note_label|Willard_28|(footnote number)|a}} to the end of the footnote list. For example, for a list that went from 1 to 67, your (footnote number) would be 68 (67 + 1). You would thus add the code snippet {{Note_label|Willard_28|68|a}} to the list. | |||

| 4) If the exact source and page number are already listed, then DO NOT add your code to the end of the text. Instead, find the line in the list where your source and page number are listed. Next, take note of the highest-lettered snippet already on that line. For example, if this highest snippet was {{Note_label|Willard_28|68|d}}, then you must take note of the letter "d". You would then add the snippet {{Note_label|Willard_28|68|e}}, choosing the letter "e" (which is one letter higher than "d". | |||

| 4) Add #{{Ref_label|Willard_28|(footnote number)|(footnote letter)}} to the body of the text, where you want the inline cite to appear. | |||

| 5) Again, multiple footnotes to the same reference are possible using the auxiliary template {{note_label|(footnote name)|(footnote number)|(footnote letter)}} and {{ref_label|(footnote name)|(footnote number)|(footnote letter)}}. See ] and ] for more details and help. | |||

| NOTE: It is extremly important to give the footnote the correct number and letter, and to add it to either the end of the list or to line that contains footnotes that share your desired footnote's source and page number. Not doing so will result in introduced mismatches between inline cite numbering and the corresponding footnote numbers. | |||

| --> | |||

| <div style="font-size: 85%"><references/></div> | |||

| <!-- #{{note_label|Badr_Armstrong_176|1|a}} Armstrong, Page 176.--> | |||

| <!-- #{{note_label|Badr_Armstrong_179|2|a}} Armstrong, Page 179.--> | |||

| <!-- #{{note_label|Badr_Quran_22:39-40|3|a}} '''Quran: Sura 22:39-40''': ''To those against whom war is made, permission is given (to fight), because they are wronged;- and verily, Allah is most powerful for their aid; (They are) those who have been expelled from their homes in defiance of right,- (for no cause) except that they say, "our Lord is Allah.. Did not Allah check one set of people by means of another, there would surely have been pulled down monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques, in which the name of Allah is commemorated in abundant measure. Allah will certainly aid those who aid his (cause);- for verily Allah is full of Strength, Exalted in Might, (able to enforce His Will).''</div> --> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| ===Books and articles=== | |||

| * {{Web reference | title=Translation of Sahih al-Bukhari. | work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts | url=http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/fundamentals/hadithsunnah/bukhari/ | date=January | year=2006}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Ali, Abdullah Yusuf|author-link=Abdullah Yusuf Ali |title=The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation & Commentary|publisher=Tahrike Tarsile Qur'an; Reissue edition|year=1987|isbn=0-940368-32-3}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Armstrong, Karen|author-link=Karen Armstrong | title=Muhmmad: Biography of the Prophet|publisher=HarperCollins|year=1992|isbn=0-06-250886-5|title-link=Muhammad: a Biography of the Prophet (book) }} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Crone, Patricia|author-link= Patricia Crone|title = Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam|publisher=Blackwell|year=1987}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Hayward |first1=Joel |author1-link=Joel Hayward |title=The Warrior Prophet: Muhammad and War |year=2022 |publisher=Claritas Books |isbn=9781800110045}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Hodgson, Marshall|author-link=Marshall Hodgson|title=The Venture of Islam: The Classical Age of Islam|publisher=]|year=1974|isbn=0-226-34683-8|url=https://archive.org/details/ventureofislamco00hodg}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Lings, Martin|author-link=Martin Lings|title=Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources|publisher=Inner Traditions International|year=1983|isbn=0-89281-170-6}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Mubarakpuri |first=Safi-ul-Raḥmān |title=Ar-Raheeq Al Makhtum: The Sealed Nectar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r_80rJHIaOMC&pg=PA267 |year=2002 |publisher=Darussalam |isbn=9960-899-55-1 |access-date=2016-03-16}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Nicolle, David|author-link=David Nicolle |title=Armies of the Muslim Conquest|publisher=]|year=1993|isbn=1-85532-279-X}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Ramadan|first=Tariq | author-link=Tariq Ramadan | title=In the Footsteps of the Prophet | location=United States of America | publisher=] | year=2007 | isbn=978-0-19-530880-8 | url=https://archive.org/details/infootstepsofpro00rama }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Rippin |first=Andrew |title=The Blackwell Companion to the Qur'an |publisher=Blackwell Publishing |year=2009 |isbn=978-1-4051-8820-3 |location=Chichester, West Sussex |url-access=}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Watt|first= W. Montgomery|author-link=Montgomery Watt|title=Muhammad at Medina|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1956|title-link=Muhammad at Medina (book)}} | |||

| *{{cite encyclopedia | |||

| | title = Badr | |||

| | encyclopedia = THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF ISLAM: NEW EDITION | |||

| | last=Watt | |||

| | first= W. Montgomery | |||

| | volume = 1 | |||

| | pages = 867-868 | |||

| | publisher = E. J. Brill | |||

| | year = 1986 | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Online references=== | |||

| *{{Book_reference|Author=] |Title=The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation & Commentary|Publisher=Tahrike Tarsile Qur'an; Reissue edition|Year=1987|ID=ISBN 0-9403-6832-3}} | |||

| * {{cite web| title=Translation of Malik's Muwatta.| work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts| url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/muwatta/| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101017073827/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/muwatta/| archive-date=17 October 2010| url-status=dead}} | |||

| * {{cite web| title=Translation of Sahih Muslim.| work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts| url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/muslim/| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101017073822/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/muslim/| archive-date=17 October 2010| url-status=dead}} | |||

| * {{cite web|title=Translation of Sahih al-Bukhari. |work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts |url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101017071704/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/ |archive-date=17 October 2010 |url-status=dead }} | |||

| * {{cite web| title=Partial Translation of Sunan Abu-Dawud.| work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts| url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/abudawud/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101017073817/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/abudawud/| archive-date=17 October 2010| url-status=dead}} | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| *{{Book_reference|Author=] | Title=Muhmmad: Biography of the Prophet|Publisher=HarperCollins|Year=1992|ID=ISBN 0-0625-0886-5}} | |||

| * ] (2002). ''The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet ﷺ.'' ]: ]. {{ISBN|978-603-50011-0-6}}. | |||

| *{{Book_reference|Author=]|Title=The Venture of Islam: The Classical Age of Islam|Publisher=]|Year=1974|ID=ISBN 0-226-34683-8}} | |||

| * Najeebabadi, Akbar Shah (2000). ''The History of Islam''. ]: ]. | |||

| * Abu Khalil, Shauqi (2003). ''Atlas of the Qur'an: Places. Nations. Landmarks.'' ]: ] {{ISBN|9960-897-54-0}}. | |||

| *{{Book_reference|Author=]|Title=Muhammad: His Life Base on the Earliest Sources|Publisher=Inner Traditions International|Year=1983|ID=ISBN 0-8928-1170-6}} | |||

| * {{Web reference | title=Translation of Malik's Muwatta. | work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts | url=http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/fundamentals/hadithsunnah/muwatta/ | date=January | year=2006}} | |||

| * {{Web reference | title=Translation of Sahih Muslim. | work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts | url=http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/fundamentals/hadithsunnah/muslim/ | date=January | year=2006}} | |||

| *{{Book_reference|Author=Nicolle, David |Title=Armies of the Muslim Conquest|Publisher=]|Year=1993|ID=ISBN 1-8553-2279-X}} | |||

| * {{Web reference | title=Partial Translation of Sunan Abu-Dawud. | work=USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts | url=http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/fundamentals/hadithsunnah/abudawud/ | date=January | year=2006}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{wikiquote}} | {{wikiquote}} | ||

| {{Commons category|Battle of Badr}} | |||

| {{wikisource}} | |||

| {{Wikisource|The Holy Qur'an/Al-Anfal}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * |

* : Islamic Occasions Network | ||

| * |

* : Analysis of Qur'anic verses by Irshaad Hussain. | ||

| *: Islamic Occasions Network | |||

| * A nice multimedia presentation at IslamOnline.Net | |||

| *: Analysis of Quranic verses by Irshaad Hussain. | |||

| {{Characters and names in the Quran}} | |||

| {{start box}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{succession box | before = ]| title = Life of the ]|years= Year: 624 CE| after = ]}}}} | |||

| {{end box}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:55, 12 January 2025

First major battle in early Islam (624)

| Battle of Badr | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Muslim–Quraysh War | |||||||

Scene from Siyer-i Nebi, Hamza and Ali leading the Muslim armies at Badr. The writing is Ottoman Naskh. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Muslim forces from Medina | Quraysh forces from Mecca | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Muhammad Ali ibn Abi Talib Zubayr ibn al-Awwam al-Miqdad bin 'Amr Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib Umar ibn al Khattab Ubaydah ibn al-Harith † Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi |

Amr ibn Hisham † Utbah ibn Rabi'ah † Umayyah ibn Khalaf † Shaybah ibn Rabi'ah † Walid ibn Utbah † Uqba ibn Abi Mu'ayt † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 313 |

Total: 1,000

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total: 14 killed

| 70 killed, 70 prisoners | ||||||

| |||||||

| Campaigns of Muhammad | |

|---|---|

| Further information: Military career of Muhammad |

The Battle of Badr (Arabic: غَزْوَةُ بَدْرٍ [ɣazwatu badr] (Urdu transliteration: Ghazwah-i-Badr), also referred to as The Day of the Criterion (Arabic: يَوْمُ الْفُرْقَانْ, Arabic pronunciation: [jawm'ul fur'qaːn]) in the Qur'an and by Muslims, was fought on 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan, 2 AH), near the present-day city of Badr, Al Madinah Province in Saudi Arabia. Muhammad, commanding an army of his Sahaba, defeated an army of the Quraysh led by Amr ibn Hishām, better known among Muslims as Abu Jahl. The battle marked the beginning of the six-year war between Muhammad and his tribe. Prior to the battle, the Muslims and the Meccans had fought several smaller skirmishes in late 623 and early 624.

Muhammad took keen interest in capturing Meccan caravans after his migration to Medina, seeing it as repayment for his people, the Muhajirun. A few days before the battle, when he learnt of a Makkan caravan returning from the Levant led by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, Muhammad gathered a small expeditionary force to capture it. Abu Sufyan, learning of the Muslim plan to ambush his caravan, changed course and took a longer route away from Muhammad's base at Medina and sent a messenger to Mecca, asking for help. Amr Bin Hisham commanded an army nearly one-thousand strong, approaching Badr and encamping at the sand dune al-'Udwatul Quswa.

Badr was the first large-scale engagement between the Muslims and Quraysh Meccans. Advancing from the north, the Muslims faced the Meccans. The battle began with duels between the warriors on both sides, following which the Meccans charged upon the Muslims under a cover of arrows. The Muslims countered their charge and broke the Meccan lines, killing several important Quraishi leaders including Abu Jahl and Umayyah ibn Khalaf.

The Muslim victory strengthened Muhammad's position; The Medinese eagerly joined his future expeditions and tribes outside Medina openly allied with Muhammad. The battle has been passed down in Islamic history as a decisive victory attributable to divine intervention, and by other sources to the strategic prowess of Muhammad.

Background

Main article: Muhammad in Mecca See also: HijraAfter the Hijra (migration to Medina) in 622 CE, the population of Medina chose Muhammad to be the leader of the community. Muhammad's followers decided to raid the caravans of the Meccans as they passed by Medina. This decision was taken in response to the Meccans persecution of the Muslims and their forceful seizing of Muslim land and property following the Hijra.

In early 624, a caravan of the Quraysh led by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb carrying wealth and goods from the Levant (possibly Gaza) was returning to Mecca. It was carrying merchandise worth 50,000 dinars and guarded by 70 men. The caravan was extraordinarily large, possibly because several smaller caravans may have grouped together for safety. All the leading Meccan financiers had a share in this trading venture, and thus had a strong interest in it returning.

Muhammad learned of the caravan and decided to intercept it for two reasons. First, was the continuation of the policy to recover wealth from the Quraysh, as the Quraysh had confiscated Muslims' properties in Mecca after the hijrah. Secondly, a successful attack would impress the Meccans and could act as a deterrent against a future attack on Medina.