| Revision as of 09:07, 14 December 2010 view sourceAladdinSE (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers3,071 editsm fixed dead link← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:49, 6 January 2025 view source Albertatiran (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,108 edits Undid revision 1267687149 by AlijanR313 (talk) RvTags: Undo Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Battle in 680 between Umar ibn Sa'd and Husayn ibn Ali}} | |||

| {{For|the battles in the ]|Battle of Karbala (2003) | Battle of Karbala (2007)}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| | partof = the ] | |||

| |caption= | |||

| | |

| image = Brooklyn Museum - Battle of Karbala - Abbas Al-Musavi - cropped.jpg | ||

| | caption = Abbas Al-Musavi's ''Battle of Karbala'', ] | |||

| ] | |||

| | conflict = Battle of Karbala | |||

| Hussein bin Ali with his infant son in his hand, as he addressed Yazid's army. | |||

| | date = 10 October 680 CE (10 Muharram 61 AH) | |||

| |partof= | |||

| | place = ], Iraq | |||

| |date=10 Muharram 61, October 10, 680 ] | |||

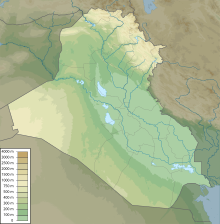

| | map_type = Iraq | |||

| |place=] | |||

| | map_relief = 1 | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|32|36|55|N|44|01|53|E|type:event|display=inline,title}} | |||

| |combatant1=] | |||

| | result = {{ublist|] victory}} | |||

| |combatant2=] | |||

| * Martyrdom of ] | |||

| |commander1=]<br />] <br /> ] <br /> ] ''(left his army and joined ] during the battle)'' {{KIA}}<sup></sup> | |||

| * Many of Husayn's family members taken prisoner | |||

| |commander2=]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| |strength1= 4,000<ref>http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/312214/Battle-of-Karbala</ref> or 5,000<ref name="al-islam.org">http://www.al-islam.org/short/Karbala.htm</ref> (at least) - 30,000<ref name="al-islam.org"/> or 100,000<ref>{{Cite book|title= Hamish Tathkirat al Khawass}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=al Muqarram |first= Abd al Razzaq |title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain |chapter= The Hosts |page=160}}</ref> (at most) | |||

| | combatant1 = ] | |||

| |strength2=72 including 6 months old baby boy ]<ref name="al-islam.org"/>|(72 adults, 54 children, 2 women) | |||

| | combatant2 = Husayn ibn Ali and his partisans | |||

| |casualties1=Heavy | |||

| | commander1 = ]<br />]<br /> ]<br /> ] ''(defected)'' | |||

| |casualties2=72 | |||

| | commander2 = ]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}}<br />]{{KIA}} | |||

| | notes = <ol style="list-style-type:lower-alpha"> | |||

| | strength1 = 4,000–5,000{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=65}}{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}}{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}}{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=109}}{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=9}}{{efn|name=fn1}} | |||

| <li>Hurr was originally one of the commanders of Ibn Ziyad's army but changed allegiance to Hussein along with his son, slave and brother on 10 Muharram 61, October 10, 680 ] | |||

| | strength2 = 70–145 | |||

| | casualties1 = 88 | |||

| | casualties2 = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Campaignbox Second Fitna}} | {{Campaignbox Second Fitna}} | ||

| {{Shia Islam}} | {{Shia Islam|collapsed=1}} | ||

| {{Husayn}} | |||

| The '''Battle of Karbala''' took place on ] 10, in the year 61 of the ]<ref name="al-islam.org"/> | |||

| (October 10, 680)<ref></ref><ref></ref> in ], in present day ]. On one side were supporters and relatives of ]'s grandson ], on the other side was a military detachment from the forces of ], the ] ]. | |||

| The '''Battle of Karbala''' ({{langx|ar|مَعْرَكَة كَرْبَلَاء|maʿraka Karbalāʾ}}) was fought on 10 October 680 (10 ] in the year 61 ] of the ]) between the army of the second ] ] ({{Reign|680|683}}) and a small army led by ], the grandson of the Islamic prophet ], at ], ] (modern-day southern ]). | |||

| The Battle of Karbala is commemorated during an annual 10-day period held every Muharram by the Shi'ah as well as many Sunnis, culminating on its tenth day, ].<ref>[http://www.aimislam.com/files/handouts/The%20Everlasting%20Stand.pdf: The Everlasting Stand - Muharram 1427</ref> | |||

| Prior to his death, the Umayyad caliph ] ({{Reign|661|680}}) had nominated his son Yazid as his successor. Yazid's nomination was contested by the sons of a few prominent companions of Muhammad, including Husayn, son of the fourth caliph ], and ], son of ]. Upon Mu'awiya's death in 680, Yazid demanded allegiance from Husayn and other dissidents. Husayn did not give allegiance and traveled to ]. The people of ], an Iraqi garrison town and the center of Ali's caliphate, were averse to the ]-based Umayyad caliphs and had a long-standing attachment to the house of Ali. They proposed Husayn overthrow the Umayyads. On Husayn's way to Kufa with a retinue of about 70 men, his caravan was intercepted by a 1,000-strong army of the caliph at some distance from Kufa. He was forced to head north and encamp in the plain of Karbala on 2 October, where a larger Umayyad army of 4,000{{efn|name=fn1|1=The Shi'a sources assert that the army was 30,000 strong.{{sfn|Munson|1988|p=23}}}} arrived soon afterwards. Negotiations failed after the Umayyad governor ] refused Husayn safe passage without submitting to his authority, a condition declined by Husayn. Battle ensued on 10 October during which Husayn was killed along with most of his relatives and companions, while his surviving family members were taken prisoner. The battle was the start of the ], during which the Iraqis organized two separate campaigns to avenge the death of Husayn; the first one by the ] and the other one by ] and his supporters. | |||

| ==Political background== | |||

| {{See also|Succession to Muhammad}} | |||

| The Battle of Karbala galvanized the development of the pro-]{{efn|1=Political supporters of Ali and his descendants (Alids).{{sfn|Donner|2010|p=178}}{{sfn|Kennedy|2004|p=89}}}} party (''Shi'at Ali'') into a distinct religious sect with its own rituals and ]. It has a central place in ] history, tradition, and theology, and has frequently been recounted in ]. For the Shi'a, Husayn's suffering and death became a symbol of sacrifice in the struggle for right against wrong, and for justice and truth against injustice and falsehood. It also provides the members of the Shi'a faith with a catalog of heroic norms. The ] during an annual ten-day period during the Islamic month of Muharram by Shi'a, culminating on tenth day of the month, known as the ]. On this day, Shi'a Muslims mourn, hold public processions, organize religious gathering, beat their chests and in some cases ]. ]s likewise regard the incident as a historical tragedy; Husayn and his companions are widely regarded as ]s by both Sunni and Shi'a Muslims. | |||

| The rule of the third Caliph ] concluded with a violent uprising. This uprising ended with the assassination of ] and for many days rebels seized and occupied the city of ]. Under the overwhelming pressure of the ], ] was elected as the fourth ] with massive numbers of people swearing their allegiance to him. His immediate steps were to ensure the unity of ]. He issued the orders of not attacking the rebels until order was restored. The governor of ], ], kinsman to the murdered Caliph Uthman, refused allegiance to ] and revolted against him, in part due to Ali's failure to bring the murders of Uthman to Justice. This resulted in armed confrontations between the Islamic Caliph ] and ]. Practically, the Muslim world became divided. At the death of ], his elder son ] succeeded him but soon signed a treaty with ] to avoid further bloodshed<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.al-islam.org/short/Karbala.htm|title= Karbala: Chain of events Section - PEACE AGREEMENT BETWEEN IMAM AL-HASAN AND MU'AWIYA | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. ] remained the ruler of ]. Prior to his death, ] was actively plotting a major deviation from Islamic norms<ref name="http">{{Cite web|url= http://www.al-islam.org/short/Karbala.htm|title= Karbala: Chain of events Section - MU'AWIYA DESIGNATES YAZID AS SUCCESSOR| publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. He was establishing his son ] as the next ruler hence establishing dynastic rule for the first time in ]. This was a move which was considered unacceptable by some leaders of the ] including the younger son of ], ]<ref name="http"/><ref>{{Cite book|last=al Muqarram |first= Abd al Razzaq |title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain |chapter=1. Al Husain's Uprising |pages=21–33}}</ref>. | |||

| ==Political background== | |||

| The majority of Muslims were observing the conduct of the leaders of prominent companion families, namely, ], ], ], ] and ]. In his written instructions to ], ] suggested specific strategies for each one of them. Muawiya warned Yazid specifically about ], since he was the only blood relative of the prophet Muhammad <ref>{{Cite book|last=al Muqarram |first= Abd al Razzaq |title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain |chapter=1. Al Husain's Uprising |page=32}}</ref>. Yazid was successful in coercing ], ] and Abdur Rehman Ibn Abu Bakr. ] took refuge in ]. ] believed the appointment of ] as the heir of the ] would lead to hereditary kingship, which was against the original political teachings of ]. Therefore, he resolved to confront ].<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.al-islam.org/short/Karbala.htm|title= Karbala: Chain of events Section - YAZID BECOMES RULER | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref> | |||

| {{see also|Succession to Muhammad|First Fitna}} | |||

| ] following ], struck at the ] mint, dated AH 61 (AD 680/1), the year in which the Battle of Karbala occurred]] | |||

| After the third caliph ]'s ] in 656, the rebels and the townspeople of ] declared ], a cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet ], caliph. Some of Muhammad's ] including ], ] and ] (then governor of ]), and Muhammad's widow ], refused to recognize Ali. They called for revenge against Uthman's killers and the election of a new caliph through '']'' (consultation). These events precipitated the ] (First Muslim Civil War).{{sfn|Donner|2010|pp=157–160}} When Ali ] by ], a ], in 661, his eldest son ] succeeded him but soon signed a ] to avoid further bloodshed.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} In the treaty, Hasan was to hand over power to Mu'awiya on the condition that Mu'awiya be a just ruler and that he would not establish a dynasty.{{sfn|Donaldson|1933|pp=70–71}}{{sfn|Jafri|1979|pp=149–151}}{{sfn|Madelung|1997|pp=322–323}}{{efn|1=Several conflicting terms of the treaty have been reported. Most of the accounts mention various financial rewards to Hasan. Other conditions, different in different sources, include selection of new caliph through '']'' (consultation) after Mu'awiya's death, transfer of the caliphate to Hasan after Mu'awiya's death, general amnesty to Hasan's followers, rule according to ] and the ] of Muhammad, discontinuation of cursing of Ali from the pulpit, financial rewards to Husayn, and preferential treatment of the ] (clan of Muhammad). According to Vaglieri, conditions other than financial benefits are suspect and were probably invented later in order to mitigate criticism of Hasan for having abdicated.{{sfn|Vaglieri, L. Veccia|1971|pp=241–242}} Jafri, on the other hand, considers the terms in addition to financial compensation reliable.{{sfn|Jafri|1979|p=151}}}} After the death of Hasan in 670, his younger brother ] became the head of the ] clan to which the Islamic prophet Muhammad also belonged.{{sfn|Lammens|1927|p=274}} Though his father's supporters in ] gave him their allegiance, he would abide to the peace treaty between Hasan and Mu'awiya as long as the latter was alive.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} | |||

| The Battle of Karbala occurred within the crisis resulting from the succession of ].{{sfn|Hawting|2002|p=310}}{{sfn|Hitti|1961|p=221}} In 676, Mu'awiya nominated his son Yazid as successor,{{sfn|Madelung|1997|p=322}} a move labelled by the historian ] as breach of the Hasan–Muawiya treaty.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} With no precedence in Islamic history, hereditary succession aroused opposition from several quarters.{{sfn|Kennedy|2004|p=88}} Mu'awiya summoned a ''shura'', or consultative assembly, in Damascus and persuaded representatives from many provinces to agree to his plan by diplomacy and bribes.{{sfn|Lewis|2002|p=67}} He then ordered ], then the governor of Medina, where Husayn and several other influential Muslims resided, to announce the decision. Marwan faced resistance to this announcement, especially from Husayn, ], ] and ], the sons of Muhammad's prominent companions, all of whom, by virtue of their descent, could also lay claim to the caliphal title.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1927|p=145}}{{sfn|Hawting|2000|p=46}} Mu'awiya went to Medina and pressed the four dissenters to accede. He followed and threatened some of them with death, but they still refused to support him.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1927|pp=141–145}}{{sfn|Lewis|2002|page=67}} Nonetheless, Mu'awiya convinced the people of Mecca that the four had pledged their allegiance, and received allegiance from them for Yazid. On his return to Damascus, he secured allegiance from the people of Medina as well. There was no further overt protest against the plan for Yazid's succession.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1927|pp=141–145}}{{sfn|Lewis|2002|page=67}} According to the historians Fitzpatrick and Walker, Yazid's succession, which was considered as an "anomaly in Islamic history", transformed the government from a "consultative" form to a monarchy.{{sfn|Fitzpatrick|Walker|2014|p=657}} Before his death in April 680, Mu'awiya cautioned Yazid that Husayn and Ibn al-Zubayr might challenge his rule and instructed him to defeat them if they did. Yazid was further advised to treat Husayn with caution and not to spill his blood, since he was the grandson of Muhammad.{{sfn|Lammens|1921|pp=5–6}} | |||

| ==Events Before the Battle== | |||

| ] died on ] 22, 60 AH (680 CE). In violation of Islamic tradition and his own written agreement with ] {{Citation needed|date=September 2010}}, ] appointed his son ] as his successor, converting the ] into a dynasty. Few notables of the Islamic community were crucial to lending some legitimacy to this conversion of ] into a dynasty<ref name="ibn Habib 165">{{Cite book|last=ibn Habib |first= Mohammad |title= Nawadir al Makhtutat|chapter= (the Sixth Letter deals with assassinated personalities)|page=165}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book| title= Al Imamah wal Siyasah |chapter= Volume. 1 (1328 A.H./1910 A.D.: Al-Umma Press, Egypt)|page=141}}</ref>, even people like Said ibn Uthman (the third Caliph)<ref name="ibn Habib 165"/> and Al Ahnaf ibn Qays<ref>{{Cite book| title= Al Imamah wal Siyasah |chapter= Volume. 1 (1328 A.H./1910 A.D.: Al-Umma Press, Egypt)|page=141}}</ref> denounced his Caliphate<ref>{{Cite book|last=al Muqarram |first= Abd al Razzaq |title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain |chapter=1. Al Husain's Uprising |pages=29–30}}</ref>. ] was by the most significant threat to this dynastic rule, since he was the only living grandson of the prophet ]. ] instructed his Governor ] in ] to force ] to pledge allegiance to ]. ] refused it and uttered his famous words that "Anyone akin to me will never accept anyone akin to Yazid as a ruler." ] departed ] on ] 28, 60 AH (680 CE), two days after ] attempt to force him to submit to ] rule. He stayed in ] from the beginnings of the ] and all of ], ], as well as ]. | |||

| ==Prelude== | |||

| It is mainly during his stay in ] that he received many letters from ] assuring him their support and asking him to come over there and guide them. He answered their calls and sent ], his cousin, to ] as his representative in an attempt to consider the exact situation and public opinion. | |||

| On his succession, Yazid charged the governor of Medina, ], to secure allegiance from Husayn, Ibn al-Zubayr and Abd Allah ibn Umar, with force if necessary. Walid sought the advice of his Umayyad relative Marwan ibn al-Hakam, who suggested that Ibn al-Zubayr and Husayn should be forced to pledge allegiance as they were dangerous, while Ibn Umar should be left alone since he posed no threat.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1927|pp=145–146}}{{sfn|Howard|1990|pp=2–3}} Walid summoned the two, but Ibn al-Zubayr escaped to Mecca. Husayn answered the summons but declined to pledge allegiance in the secretive environment of the meeting, suggesting it should be done in public. Marwan told Walid to imprison or behead him, but due to Husayn's kinship with Muhammad, Walid was unwilling to take any action against him. A few days later, Husayn left for Mecca without acknowledging Yazid.{{sfn|Howard|1990|pp=5–7}} He arrived in Mecca at the beginning of May 680,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=61}} and stayed there until the beginning of September.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=64}} | |||

| Husayn had considerable support in Kufa, which had been the caliphal capital during the reigns of his father and brother. The Kufans had fought the Umayyads and their Syrian allies during the First Fitna, the five-year civil war which had established the Umayyad Caliphate.{{sfn|Daftary|1990|p=47}} They were dissatisfied with Hasan's abdication{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=61}} and strongly resented Umayyad rule.{{sfn|Daftary|1990|p=47}} While in Mecca, Husayn received letters from pro-] in Kufa informing him that they were tired of the Umayyad rule, which they considered to be oppressive, and that they had no rightful leader. They asked him to lead them in revolt against Yazid, promising to remove the Umayyad governor if Husayn would consent to aid them. Husayn wrote back affirmatively that a rightful leader is the one who acts according to the ] and promised to lead them with the right guidance. Then he sent his cousin ] to assess the situation in Kufa. Ibn Aqil attracted widespread support and informed Husayn of the situation, suggesting that he join them there. Yazid removed ] as governor of Kufa due to his inaction, and installed ], then governor of ], in his place. As a result of Ibn Ziyad's suppression and political maneuvering, Ibn Aqil's following began to dissipate and he was forced to declare the revolt prematurely. It was defeated and Ibn Aqil was killed.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=608}} Husayn had also sent a messenger to Basra, another garrison town in Iraq, but the messenger could not attract any following and was quickly apprehended and executed.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} | |||

| Hussain's representative to ], ] was welcomed by the people of ], and most of them swore allegiance to him. After this initial observation, ] wrote to ] that the situation in ] was favorable. However, after the arrival of the new Governor of ], ], the scenario changed. ] and his host, ], were executed on ] 9, 60AH (September 10, 680 CE) without any considerable resistance of the people. This shifted the loyalties of the people of ], in favor of ] against ]<ref>The Tragedy of Karbala, pg. 23</ref>. ] also realized a deep conspiracy that ] had appointed `Amr ibn Sa`ad ibn al As as the head of an army, ordering him to take charge of the pilgrimage caravans and to kill ] wherever he could find him during ]<ref>{{Cite book|last=al Gulpaygani |first= Shaykh Lutfullah |title= Muntakhab al Athar fi Akhbar al Imam al Thani ‘Ashar, Radiyaddin al Qazwini |pages=304, 10th Night}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=al Muqarram |first= Abd al Razzaq |title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain |chapter=The Journey to Iraq |page=130}}</ref>, and hence decided to leave ] on 08th ] 60 ] corresponding with the English calendar as 12 September 680 AD, just a day before ] and was contented with ], due to his concern about potential violation of the sanctity of the ]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Nama |first= ibn |title=Muthir al Ahzan |page=89}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|author=Al-Tabari |title= Tarikh |volume=06 |page=177}}</ref>. | |||

| He delivered a famous sermon in ] highlighting his reasons to leave that he didn't want the sanctity of ] to be violated, since his opponents had crossed any norm of decency and were willing to violate all tenets of Islam. | |||

| Husayn was unaware of the change of political circumstances in Kufa and decided to depart. ] and Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr advised him not to move to Iraq, or if he was determined, not to take women and children with him. The sincerity of Ibn al-Zubayr's advice has been doubted by many historians, however, as he had his own plans for leadership and was supposedly happy to be rid of Husayn.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}}{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=64}}{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=608}} Nevertheless, he offered Husayn support if he would stay in Mecca and lead the opposition to Yazid from there. Husayn refused this, citing his abhorrence of bloodshed in the sanctuary,{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=69}} and decided to go ahead with his plan.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=608}} | |||

| ==Journey towards Kufa== | |||

| On their way to ], the small caravan received the sad news of execution of ] and the indifference of the people of ]<ref>{{Cite book|author=Al-Tabari |title= Tarikh |Volume=6 |page=995}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=al Muqarram |first= Abd al Razzaq |title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain |chapter=Zarud |page=141}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Kathir |first= Ibn |title= Al Bidaya |volume=08 |page=168}}</ref>. Instead of turning back, Hussain decided to continue the journey and sent ] as messenger to talk to the nobles of ]. The messenger was captured in the vicinity of Kufa but managed to tear the letter to pieces to hide names of its recipients. Just like ], ] was executed. | |||

| {{Location map+ | Middle East2 | |||

| ==The Events of Battle== | |||

| | width = 300 | |||

| ]]] | |||

| | caption = Husayn traveled from Mecca to Kufa through the ]. | |||

| Husayn and his followers were two days' journey away from Kufa when they were intercepted by the vanguard of Yazid's army; about 1000 men led by ]. Upon interception by vanguards Husayn asked: "With us or against us?" They replied: "Of course against you, oh Aba Abd Allah!" ] said: "If you are different from what I received from your letters and from your messengers then I will return to where I came from." Their leader, ], refused Husain's request to let him return to ]. The caravan of the ]'s family arrived at ] on ] 2, 61AH (October 2, 680 CE)<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.al-islam.org/short/Karbala.htm|title= Karbala: Chain of events Section – On the Way to Karbala | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. They were forced to pitch a camp on dry, bare land and ] stationed his army nearby. | |||

| | AlternativeMap = Middle East geographic.jpg | |||

| | places = | |||

| {{Location map~ | Middle East2 | |||

| | marksize = 6 | |||

| | label = ] | |||

| | lat_deg = 26 | lat_min = 30 | lat_dir = N | |||

| | lon_deg = 33 | lon_min = 40 | lon_dir = E | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Location map~ | Middle East2 | |||

| | marksize = 6 | |||

| | label = ] | |||

| | lat_deg = 23 | lat_min = 0 | lat_dir = N | |||

| | lon_deg = 34 | lon_min = 10 | lon_dir = E | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Location map~ |Middle East2 | |||

| | marksize = 6 | |||

| | label = ] | |||

| | location = left | |||

| | lat_deg = 35 | lat_min = 00 | lat_dir = N | |||

| | lon_deg = 39 | lon_min = 36 | lon_dir = E | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Location map~ | Middle East2 | |||

| | marksize = 6 | |||

| | label = ] | |||

| | lat_deg = 35 | lat_min = 40 | lat_dir = N | |||

| | lon_deg = 39 | lon_min = 20 | lon_dir = E | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| Husayn left Mecca with some fifty men and his family on 9 September 680 (8 Dhu al-Hijjah 60 AH), a day before ].{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=64}}{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=608}} He took the northerly route through the ].{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=9}} On persuasion of Husayn's cousin ], the governor of Mecca ] sent his brother and Ibn Ja'far after Husayn in order to assure him safety in Mecca and bring him back. Husayn refused to return, relating that Muhammad had ordered him in a dream to move forward irrespective of the consequences. At a place known as Tan'im, he seized a caravan carrying dyeing plants and clothes sent by the governor of ] to Yazid. Further on the way, at a place called Tha'labiyya, the small caravan received the news of the execution of Ibn Aqil and the indifference of the people of Kufa. Husayn at this point is reported to have considered turning back, but was persuaded to push forward by Ibn Aqil's brothers, who wanted to avenge his death;{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}}{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=64}} according to Madelung and I. K. A. Howard, these reports are doubtful.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}}{{sfn|Howard|1986|p=128}} Later, at Zubala, Husayn learned of the capture and execution of his messenger ], whom he had sent from the ] (western Arabia) to Kufa to announce his arrival.{{efn|1=According to other accounts, the person was Husayn's foster brother Abd Allah ibn Yaqtur whom he had sent after learning of Ibn Aqil's execution.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|pp=105–106}}}} He informed his followers of the situation and asked them to leave. Most of the people who had joined him on the way left, while his companions from Mecca decided to stay with him.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}} | |||

| ] appointed ] to command the battle against Husain ibn Ali. At first Umar ibn Sa'ad rejected the leadership of the army but he accepted after Ibn Ziyad threatened to depose him from the governorship of ] city and also to get his position replaced by ].<ref name="ReferenceA">{{Cite web|url= http://www.al-islam.org/short/Karbala.htm|title= Karbala: Chain of events Section –Karbala | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref> ] also urged ] to initiate the battle on the sixth day of ]<ref>{{Cite book|last=al Qazwini |first= Radiyaddin ibn Nabi |title= Tazallum al Zahra |page=101}}</ref>. ] moved towards the battlefield with a 30,000<ref name="al-islam.org"/>-men army and arrived at Karbala on Muharram 2, 61 AH (October 3, 680 CE). | |||

| Ibn Ziyad had stationed troops on the routes into Kufa. Husayn and his followers were intercepted by the vanguard of Yazid's army, about 1,000 men led by ], south of Kufa near ].{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}} Husayn said to them: <blockquote>I did not come to you until your letters were brought to me, and your messengers came to me saying, 'Come to us, for we have no imām. God may unite us in the truth through you.' Since this was your view, I have come to you. Therefore, if you give me what you guaranteed in your covenants and sworn testimonies, I will come to your town. If you will not and are averse to my coming, I will leave you for the place from which I came to you.{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=93}}</blockquote> He then showed them the letters he had received from the Kufans, including some in Hurr's force. Hurr denied any knowledge of the letters and stated that Husayn must go with him to Ibn Ziyad, which Husayn refused to do. Hurr responded that he would not allow Husayn to either enter Kufa or go back to Medina, but that he was free to travel anywhere else he wished. Nevertheless, he did not prevent four Kufans from joining Husayn. Husayn's caravan started to move towards Qadisiyya, and Hurr followed them. At Naynawa, Hurr received orders from Ibn Ziyad to force Husayn's caravan to halt in a desolate place without fortifications or water. One of Husayn's companions suggested that they attack Hurr and move to the fortified village of al-Aqr. Husayn refused, stating that he did not want to start the hostilities.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}} On 2 October 680 (2 Muharram 61 AH), Husayn arrived at ], a desert plain {{convert|70|km|sp=us}} north of Kufa, and set up camp.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=65}}{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=9}} | |||

| ] sent a brief letter to Umar ibn Sa'd that commanded: "Prevent Husayn and his disciples from accessing water and do not allow them to drink a drop of water. Ibn Sa'ad ordered 5000 horsemen to cut Husain's camp off from the ] to stop them from accessing water. | |||

| One of the disciples of Husain ibn Ali met Umar ibn Sa'ad and negotiated to get access to water, which the latter denied. The water blockade continued up to the end of the battle on Muharram 10 night (October 10, 680 CE)<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , The Watering place, pg.162 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] received an order from ] to start the battle immediately and not to postpone it further. The army started stealthily advancing toward Husain's camp on the afternoon of 9th of Muharram. At this time Husain sent Abbas ibn Ali to ask ibn Sa'ad for another delay, until the next morning, so that he and his men could spend the night praying. Ibn Sa'ad agreed the respite<ref name="ReferenceA"/><ref>{{Cite book|last=Tabari |first=Al |title= Tarikh |volume=06 |page=337}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Day Nine, pg.169 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. | |||

| On the following day, a 4,000-strong Kufan army arrived under the command of ].{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|pp=65–66}} He had been appointed governor of ] to suppress a local rebellion, but then recalled to confront Husayn. Initially, he was unwilling to fight Husayn, but complied following Ibn Ziyad's threat to revoke his governorship. After negotiations with Husayn, Ibn Sa'd wrote to Ibn Ziyad that Husayn was willing to return. Ibn Ziyad replied that Husayn must surrender or he should be subdued by force,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|pp=65–66}} and that to compel him, he and his companions should be denied access to the ] river.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} Ibn Sa'd stationed 500 horsemen on the route leading to the river. Husayn and his companions remained without water for three days before a group of fifty men led by his half-brother ] was able to access the river. They could only fill twenty water-skins.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}}{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=111}} | |||

| Husayn and Ibn Sa'd met during the night to negotiate a settlement; it was rumored that Husayn made three proposals: either he be allowed to return to Medina, submit to Yazid directly, or be sent to a border post where he would fight alongside the Muslim armies. According to Madelung, these reports are probably untrue as Husayn at this stage is unlikely to have considered submitting to Yazid. A '']'' of Husayn's wife later claimed that Husayn had suggested that he be allowed to leave, so that all parties could allow the fluid political situation to clarify.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} Ibn Sa'd sent the proposal, whatever it was, to Ibn Ziyad, who is reported to have accepted but then persuaded otherwise by ]. Shemr argued that Husayn was in his domain and letting him go would be to demonstrate weakness.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=111}} Ibn Ziyad then sent Shemr with orders to ask Husayn for his allegiance once more and to attack, kill and disfigure him if he was to refuse, as "a rebel, a seditious person, a brigand, an oppressor and he was to do no further harm after his death".{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}} If Ibn Sa'd was unwilling to carry out the attack, he was instructed to hand over command to Shemr. Ibn Sa'd cursed Shemr and accused him of foiling his attempts to reach a peaceful settlement but agreed to carry out the orders. He remarked that Husayn would not submit because there was "a proud soul in him".{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=609}}{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} | |||

| On the night before the battle, Husain gathered his men and told them that they were all free to leave the camp in the middle of the night, under cover of darkness, rather than face certain death if they stayed with him. None of Husain's men wished to defect and remained with him. Husain and his followers held a vigil to pray all night<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Those Whose Conscience is Free, pg.170 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. | |||

| The army advanced toward Husayn's camp on the evening of 9 October. Husayn sent Abbas to ask Ibn Sa'd to wait until the next morning, so that they could consider the matter. Ibn Sa'd agreed to this respite.{{sfn|Howard|1990|pp=112–114}} Husayn told his men that they were all free to leave, with his family, under the cover of night, since their opponents only wanted him. Very few availed themselves of this opportunity. Defense arrangements were made: tents were brought together and tied to one another and a ditch was dug behind the tents and filled with wood ready to be set alight in case of attack. Husayn and his followers then spent the rest of the night praying.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}}{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} | |||

| ====Day of the battle==== | |||

| <!--] painting of Ashura afternoon, after the death of Husain ibn Ali. The paining shows Husayn's children and sister weeping around his thoroughbred horse when it came back toward their tents. — By Iranian miniaturist ''Mahmoud Farshchiyan''.<ref></ref>]]--> | |||

| ==Battle== | |||

| On ] 10 also called ], ] offered his morning prayers with his companions. He appointed ] to command the right flank, ] to command the left flank and his half-brother ] as standard bearer of his army. There is controversy regarding gregorian date for the day of Ashura. October 10, is a calculated date through calculators<ref></ref><ref></ref>. But,these calculators are not always correct. According to book Maqtal al Hussain Muharram 9 is October 12, 680, so it appears that the date was October 12, 680 A.D. | |||

| After the morning prayer on 10 October, both parties took up battle positions. Husayn appointed ] to command the right flank of his army, ] to command the left flank, and his half-brother Abbas as the standard bearer.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}} Husayn's companions, according to most accounts, numbered thirty-two horsemen and forty infantrymen; although forty-five horsemen and one hundred foot-soldiers, or a total of a few hundred men have been reported by some sources.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=105}} Ibn Sa'd's army totaled 4,000. According to the Shi'a sources, however, more troops had joined Ibn Sa'd in preceding days, swelling his army to 30,000 strong.{{sfn|Munson|1988|p=23}} The ditch containing wood was set alight.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=66}} Husayn then delivered a speech to his opponents reminding them of his status as Muhammad's grandson and reproaching them for inviting and then abandoning him. He asked to be allowed to leave. He was told that first he had to submit to Yazid's authority, which he refused to do.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}} Husayn's speech moved Al-Hurr ibn Yazid Al-Tamimi to defect to his side.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=66}} | |||

| ] in Karbala]] | |||

| The companions of ] were 32 horsemen and 40 infantrymen.<ref>Lohouf ({{lang-ar|اللهوف}}), By Sayyid ibn Tawoos ({{lang-ar|سید ابن طاووس}}). Tradition No. 140</ref> Husayn rode on his horse ]. | |||

| After Husayn's speech, Zuhayr ibn Qayn attempted to dissuade Ibn Sa'd's soldiers from killing Husayn, but in vain. Ibn Sa'd's army fired several volleys of arrows. This was followed by duels{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}} in which several of Husayn's companions were slain. The right wing of the Kufans, led by Amr ibn al-Hajjaj, attacked Husayn's force, but was repulsed. Hand-to-hand fighting paused and further volleys of arrows were exchanged. Shemr, who commanded the left wing of the Umayyad army, launched an attack, but after losses on both sides he was repulsed.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}}{{sfn|Howard|1990|pp=138–139}} This was followed by cavalry attacks. Husayn's cavalry resisted fiercely and Ibn Sa'd brought in armoured cavalry and five hundred archers. After their horses were wounded by arrows, Husayn's cavalrymen dismounted and fought on foot.{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=139}} | |||

| ] called the people around him to join him for the sake of ] and to defend ]'s family. His speech affected ], the commander of the ] and ] tribes who had stopped ] from his journey. He abandoned ] and galloped his horse to ]'s small force<ref name="Naqviz.org">{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Al-Hurr Repents, pg.189 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. | |||

| Since Umayyad forces could approach Husayn's army from the front only, Ibn Sa'd ordered the tents to be burned. All except the one which Husayn and his family were using were set on fire. Shemr wanted to burn that one too, but was prevented by his companions. The plan backfired and flames hindered the Umayyad advance for a while. After noon prayers, Husayn's companions were encircled, and almost all of them were killed. Husayn's relatives, who had not taken part in the fighting so far, joined the battle. Husayn's son ] was killed; then Husayn's half-brothers, including Abbas,{{sfn|Calmard|1982|pp=77–79}} and the sons of ], ] and Hasan ibn Ali were slain.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}} The account of Abbas' death is not given in the primary sources, ] and ], but a prominent Shi'a theologian ] states in his account in '']'' that Abbas went to the river together with Husayn but became separated, was surrounded, and killed.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}}{{sfn|Calmard|1982|pp=77–79}} At some point, a young child of Husayn's, who was sitting on his lap, was hit by an arrow and died.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}} | |||

| On the other side, Yazid had sent ] (his chief commander) to replace ] ibn Yazid as the commander. He reorganized his army and by afternoon, he had come to know that ] along with his son had defected to ] army.<ref name="Naqviz.org"/><ref>{{Cite book|last=Tabari |first=Al |title= Tarikh |volume=06 |page=244}}</ref><ref>Book "Martyrdom Of Hussain"</ref> | |||

| === Death of Husayn ibn Ali === | |||

| =====The battle starts===== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] advanced and fired an arrow at ] army, saying: "Give evidence before the governor that I was the first thrower." Then his army started showering ]'s army with weapons<ref>{{Cite book|last=Maqrizi |first=Al |title= Khutat |volume=02 |page=287}}</ref><ref name="naqviz.com">{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , The First Campaign, pg.190 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. Hardly any men from ] army escaped from being shot by an arrow<ref name="naqviz.com"/><ref>{{Cite book|last=al Bahraini |first=Abdullah Nurallah |title= Maqtal al Awalim |page=84}}</ref>. Both sides began fighting. Successive assaults resulted in the death of a group of ] companions<ref name="naqviz.com"/><ref>{{Cite book|last=Majlisi |first=Al |title= Bihar al Anwar |quote=Mohammad ibn Abutalib}}</ref>. | |||

| The Umayyad soldiers hesitated to attack Husayn directly, but he was struck in the mouth by an arrow as he went to the river to drink.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} He collected his blood in a cupped hand and cast towards the sky, complaining to God of his suffering.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}} Later, he was surrounded and struck on the head by Malik ibn Nusayr. The blow cut through his hooded cloak, which Husayn removed while cursing his attacker. He put a cap on his head and wrapped a turban around it to staunch the bleeding. Ibn Nusayr seized the bloodied cloak and retreated.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}}{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=153}} | |||

| Shemr advanced with a group of foot soldiers towards Husayn, who was now prepared to fight as few people were left on his side. A young boy from Husayn's camp escaped from the tents, ran to him, tried to defend him from a sword stroke and had his arm cut off. Ibn Sa'd approached the tents, and Husayn's sister ] complained to him: "'Umar b. Sa'd, will Abu 'Abd Allah (the kunya of Husayn) be killed while you stand and watch?"{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}} Ibn Sa'd wept but did nothing. Husayn is said to have killed many of his attackers. They were, however, still unwilling to kill him and each of them wanted to leave this to somebody else. Eventually Shemr shouted: "Shame on you! Why are you waiting for the man? Kill him, may your mothers be deprived of you!"{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=160}} The Umayyad soldiers then rushed Husayn and wounded him on his hand and shoulder. He fell on the ground face-down and an attacker named ] stabbed and then ] him.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}}{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=160}} | |||

| The first skirmish was between the right flank of Imam Husain's army with the left of the Syrian army. A couple of dozens men under the command of Zuhayr ibn Qain fought heroically and repulsed the initial infantry attack and in the process destroyed the left flank of the Syrian army which in disarray collided with the middle of the army. Seeing this, the Syrian army quickly retreated and broke the pre-war verbal agreement of not using arrows and lances. This agreement was made in view of the small number of ] companions. ] on advice of 'Amr ibn al Hajjaj ordered his army not to come out for any duel and to attack ] army together<ref name="Tabari 249">{{Cite book|last=Tabari |first=Al |title= Tarikh |volume=06 |page=249}}</ref><ref name="Maqtal_al-Husain pg.193">{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , The Right Wing Remains Firm, pg.193 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| `Amr ibn al-Hajjaj attacked ] right wing, but the men were able to maintain their ground, kneeling down as they planted their lances. They were thus able to frighten the enemy's horses. When the horsemen came back to charge at them again, al-H. usain's men met them with their arrows, killing some of them and wounding others<ref name="Maqtal_al-Husain pg.193"/><ref>{{Cite book|last=al Kathir|first=Ibn |title= Al-Kamil |volume=04 |page=27}}</ref>. `Amr ibn al-Hajjaj kept saying the following to his men, "Fight those who abandoned their creed and who deserted the jam`a!" Hearing him say so, ] said to him, "Woe unto you, O `Amr! Are you really instigating people to fight me?! Are we really the ones who abandoned their creed while you yourself uphold it?! As soon as our souls part from our bodies, you will find out who is most worthy of entering the fire!<ref name="Maqtal_al-Husain pg.193"/><ref>{{Cite book|last=al Kathir|first=Ibn |title= Al-Bidaya |volume=08 |page=182}}</ref> | |||

| ] viewed the battle]] | |||

| In order to prevent random and indiscriminate showering of arrows on ] camp which had women and children in it, Husain's followers went out to single combats. Men like Burayr ibn Khudhayr<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Burayr ibn Khudayr, pg.201 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>, Muslim ibn Awsaja<ref name="Tabari 249"/><ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Muslim ibn Awsajah, pg.193 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref> and ]<ref name="Tabari 251">{{Cite book|last=Tabari |first=Al |title= Tarikh |volume=06 |page=251}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Habib ibn Mazahir, pg.196 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref> were slain in the fighting. They were attempting to save Husain's life by shielding him. Every casualty had a considerable effect on their military strength since they were vastly outnumbered by ] army. Husain's companions were coming, one by one, to say goodbye to him, even in the midst of battle. Almost all of ] companions were killed by the onslaught of arrows or lances. | |||

| Seventy or seventy-two people died on Husayn's side, of whom about twenty were descendants of ], the father of ]. This included two of Husayn's sons, six of his paternal brothers, three sons of Hasan ibn Ali, three sons of Jafar ibn Abi Talib, and three sons and three grandsons of Aqil ibn Abi Talib.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} Following the battle, Husayn's clothes were stripped, and his sword, shoes and baggage were taken. The women's jewelry and cloaks were also seized. Shemr wanted to kill Husayn's only surviving son ], who had not taken part in the fighting because of illness, but was prevented by Ibn Sa'd.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}}{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=66}} There are reports of more than sixty wounds on Husayn's body,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=66}} which was then trampled with horses as previously instructed by Ibn Ziyad.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} The bodies of Husayn's companions were decapitated.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=67}} There were eighty-eight dead in Ibn Sa'd's army, who were buried before he left.{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=163}} After his departure, members of the Banu Asad tribe, from the nearby village of Ghadiriya, buried the headless bodies of Husayn's companions.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=611}} | |||

| After almost all of ] companions were killed, his relatives asked his permission to fight. The men of ], the clan of ] and ], went out one by one. ], the middle son of ], was the first one of ] who received permission from his father.<ref name="Tabari 251"/><ref>], ibn-Tavoos, et al.</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Martyrdom of Ahl al Bayt, Ali al Akbar, pg.206 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref> | |||

| Husayn's family, along with the heads of the dead, were sent to Ibn Ziyad.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=67}} He poked Husayn's mouth with a stick and intended to kill Ali Zayn al-Abidin, but spared him after the pleas of Husayn's sister Zaynab.{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=167}} The heads and the family were then sent to Yazid,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=67}} who also poked Husayn's mouth with a stick. The historian ] has suggested that this is a duplication of the report regarding Ibn Ziyad.{{sfn|Lammens|1921|p=171}} Yazid was compassionate towards the women and Ali Zayn al-Abidin,{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=67}} and cursed Ibn Ziyad for murdering Husayn, stating that had he been there, he would have spared him.{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=169}}{{sfn|Lammens|1921|p=172}} One of his courtiers asked for the hand of a captive woman from Husayn's family in marriage, which resulted in heated altercation between Yazid and Zaynab.{{sfn|Howard|1990|pp=171–172}}{{sfn|Lammens|1921|p=173}} The women of Yazid's household joined the captive women in their lamentation for the dead. After a few days, the women were compensated for their belongings looted in Karbala and were sent back to Medina.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=612}} | |||

| Casualties from ] were sons of ], sons of ], son of ], son of ] and ], sons of ], as well as a son of ]. There were seventy-two ] dead in all (including ])<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.naqviz.com/Maqtal_al-Husain.pdf|title= Maqtal al Husain : Martyrdom epic of Imam al Husain , Martyrdom of Ahl al Bayt, pg.206-235 | publisher=] |accessdate=2010-07-07}}</ref>. | |||

| === |

===Tawwabin uprising=== | ||

| {{main|Tawwabin uprising}} | |||

| ] advanced toward ] branch along a dyke. Abbas ibn Ali continued his advance into the heart of ibn Sa'ad's army.<ref>Lohouf, Tradition 174 and 175.</ref> He was under heavy shower of arrows but was able to penetrate them and get to the branch leaving heavy casualties from the enemy. He immediately started filling the water skin. In a remarkable and immortal gesture of loyalty to his brother and ]'s grandson he didn't drink any water despite being severely thirsty. He put the water skin on his right shoulder and started riding back toward their tents. ] ordered an outright assault on ] saying that if ] succeeds in taking water back to his camp, we won't be able to defeat them till the end of time. A massive enemy army blocked his way and surrounded him. He was ambushed from behind a bush and his right arm was cut off. ] put the water skin on his left shoulder and continued his way but his left arm was also cut off. ] now held the water skin with his teeth. The army of ibn Sa'ad started shooting arrows at him, one arrow hit the water skin and water poured out of it, now he turned his horse back towards the army and charge towards them but one arrow hit his eyes and someone hit a gurz on his head and he fell off the horse. | |||

| A few prominent Alid supporters in Kufa felt guilty for abandoning Husayn after having invited him to revolt. To atone for what they perceived as their sin, they began a movement known as the Tawwabin, under ], a companion of Muhammad, to fight the Umayyads. As long as Iraq was in Umayyad hands, the movement remained underground. After the death of Yazid in November 683, the people of Iraq drove out the Umayyad governor Ibn Ziyad; the Tawwabin called on the people to avenge Husayn's death, attracting large-scale support.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|pp=71–74}} Lacking any political program, they intended to punish the Umayyads or sacrifice themselves in the struggle. Their slogan was "Revenge for Husayn".{{sfn|Sharon|1983|pp=104–105}} Mukhtar al-Thaqafi, another prominent pro-Alid of Kufa, attempted to dissuade the Tawwabin from this endeavor in favor of an organized movement to take control of the city, but Ibn Surad's stature as a companion of Muhammad and an old ally of Ali, prevented most of his followers from accepting Mukhtar's proposal.{{sfn|Dixon|1971|p=37}} Although 16,000 men enlisted to fight, only 4,000 ]ed. In November 684, the Tawwabin left to confront the Umayyads, after mourning for a day at Husayn's grave in Karbala. The armies met in January 685 at the three-day ] in present-day northern Syria; most of the Tawwabin, including Ibn Surad, were killed. A few escaped to Kufa and joined Mukhtar.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|pp=71–74}} | |||

| ===Revolt of Mukhtar al-Thaqafi=== | |||

| In his last moments when Abbas ibn Ali was wiping the blood in his eyes to enable him to see ] face, ] said not to take his body back to the camps because he had promised to bring back water but couldn't and so couldn't face Sukainah, the daughter of ]. Then he call Imam Husayn, "brother" for the first time in his life. Before the death of Abbas, Imam Husayn was noted to have said "Abbas, your death is like the breaking of my back." | |||

| {{main|Mukhtar al-Thaqafi}} | |||

| Mukhtar was an early settler of Kufa, having arrived in Iraq following its initial conquest by the Muslims.{{sfn|Kennedy|2004|p=95}} He had participated in the failed rebellion of Muslim ibn Aqil, for which he was imprisoned by Ibn Ziyad, before being released after the intervention of Abd Allah ibn Umar. Mukhtar then went to Mecca and had a short-lived alliance with ], who had established himself in Mecca in opposition to Yazid. After Yazid's death, he returned to Kufa where he advocated revenge against Husayn's killers and the establishment of an Alid caliphate in the name of Husayn's half-brother ], and declared himself his representative.{{sfn|Daftary|1990|p=52}} The defeat of the Tawwabin left the leadership of the Kufan pro-Alids in his hands. In October 685, Mukhtar and his supporters, a significant of number of whom consisted of local converts (''mawali''), overthrew Ibn al-Zubayr's governor and seized Kufa. His control extended to most of Iraq and parts of northwestern Iran.{{sfn|Dixon|1971|p=45}} His attitude towards ''mawali'', whom he awarded many favors and equal status with Arabs, provoked a rebellion by the dissatisfied Arab aristocracy. After crushing the rebellion, Mukhtar executed Kufans involved in the killing of Husayn, including Ibn Sa'd and Shemr, while thousands of people fled to Basra.{{sfn|Donner|2010|p=185}} He then sent his general ] to fight an approaching Umayyad army, led by Ibn Ziyad, which had been sent to reconquer the province. The Umayyad army was routed at the ] in August 686 and Ibn Ziyad was slain.{{sfn|Hawting|2000|p=53}} Meanwhile, Mukhtar's relations with Ibn al-Zubayr worsened and Kufan refugees in Basra persuaded ], the governor of the city and younger brother of Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, to attack Kufa. Facing defeat in open battle, Mukhtar and his remaining supporters took refuge in the palace of Kufa and were besieged by Mus'ab. Four months later, in April 687, Mukhtar was killed while some 6,000–8,000 of his supporters were executed.{{sfn|Dixon|1971|pp=73–75}} According to Mohsen Zakeri, Mukhtar's attitude towards ''mawali'' was one of the reasons behind his failure, as Kufa was not ready for such "revolutionary measures".{{sfn|Zakeri|1995|p=208}} Mukhtar's supporters survived the collapse of his revolution and evolved into a sect known as the ]. The Hashimiyya, a splinter group of the Kaysanites, was later taken over by the ] and eventually overthrew the Umayyads in 750.{{sfn|Hawting|2000|p=51}} | |||

| ==Primary and classic sources== | |||

| =====Death of Husayn ibn Ali===== | |||

| {{See also|Maqtal al-Husayn}} | |||

| Husain ibn Ali told Yazid's army to offer him single battle, and they gave his request. He killed everybody that fought him in single battles.<ref>Lohouf, Tradition No.177</ref> He frequently forced his enemy into retreat, killing a great number of opponents. Husayn and earlier his son Hazrat Ali Akbar were the two warriors who penetrated and dispersed the core of Ibn-Saad's army (Qalb-e-Lashkar), a sign of extreme chaos in traditional warfare. | |||

| The primary source of the Karbala narrative is the work of the Kufan historian ] titled ''Kitab Maqtal Al-Husayn''.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=608}} Other early monographs on the death of Husayn, which have not survived, were written by al-Asbagh al-Nubata, Jabir ibn Yazid al-Ju'fi, Ammar ibn Mu'awiya al-Duhni, ], ], ], Nasr ibn Muzahim, and ]; of these al-Nubta's monograph was perhaps the earliest.{{sfn|Howard|1986|pp=124–125}} Although Abu Mikhnaf's date of birth is unknown, he was an adult by the time of the revolt of ], which occurred in 701, some twenty years after the Battle of Karbala. As such he knew many eyewitnesses and collected firsthand accounts and some with very short chains of transmission, usually only one or two intermediaries.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1927|pp=vii–viii}} The eyewitnesses were of two kinds: those from Husayn's side; and those from Ibn Sa'd's army. Since few people from Husayn's camp survived, most eyewitnesses were from the second category. According to ], most of them regretted their actions in the battle and embellished the accounts of the battle in favor of Husayn in order to dilute their guilt.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=68}} Although as an Iraqi, Abu Mikhnaf had pro-Alid tendencies, his reports generally do not contain much bias on his part.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1927|p=ix}} Abu Mikhnaf's original text seems to have been lost and the version extant today has been transmitted through secondary sources such as the '']'', also known as ''The History of Tabari'', by ]; and '']'' by ]. Nevertheless, four manuscripts of a ''Maqtal'' located at ] (No. 1836), ] (Sprenger, Nos. 159–160), ] (No. 792), and ] (Am No. 78) libraries have been attributed to Abu Mikhnaf.{{sfn|Jafri|1979|p=215}} Tabari quotes either directly from Abu Mikhnaf or from his student Ibn al-Kalbi, who took most of his material from Abu Mikhnaf.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=608}} Tabari occasionally takes material from Ammar ibn Mu'awiya,{{sfn|Howard|1986|p=126}} Awana{{sfn|Howard|1986|p=132}} and other primary sources, which, however, adds little to the narrative.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=67}} Baladhuri uses same sources as Tabari. Information on the battle found in the works of ] and ] is also based on Abu Mikhnaf's ''Maqtal'',{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=608}} although they occasionally provide some extra notes and verses.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=67}} Other secondary sources include ]'s '']'', ]'s ''Kitab al-Futuh'', Shaykh al-Mufid's ''Kitab al-Irshad'', and ]'s ''Maqatil al-Talibiyyin''.{{sfn|Howard|1986|p=125}} Most of these sources took material from Abu Mikhnaf, in addition to some from the primary works of Awana, al-Mada'ini and Nasr ibn Muzahim.{{sfn|Howard|1986|pp=139–142}} | |||

| Although Tabari and other early sources contain some miraculous stories,{{sfn|Jafri|1979|p=215}} these sources are mainly historical and rational in nature,{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=15}} in contrast to the literature of later periods, which is mainly ] in nature.{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=15}}{{sfn|Günther|1994|p=208}} | |||

| Imam Husayn advanced very deep in the back ranks of the Syrian army. When the enemies stood between him and the tents he shouted: <blockquote>"Woe betide you oh followers of ]'s dynasty! If no religion has ever been accepted by you and you have not been fearing the resurrection day then be noble in your world ..."<ref>"ویلکم یا شیعه آل ابی سفیان! ان لم یکن لکم دین و کنتم لا تخافون المعاد فکونو احرارا فی دنیاکم هذه و ارجعوا الی احسابکم ان کنتم عربا کما تزعمون" Lohouf, Tradition No.179</ref> </blockquote> Then his enemies invaded back toward him. | |||

| They continuously attacked each other,<ref>" و هو فی ذلک یطلب شربة من ماء فلا یجد ..." Lohouf, Tradition No.181</ref> Until his numerous injuries caused him to stay a moment. At this time he was hit on his forehead with a stone. He was cleaning blood from his face while he was hit on the heart with arrow and he said: "In the name of Allah, and by Allah, and on the religion of the messenger of Allah." Then he raised his head up and said: "Oh my God! You know that they are killing a man that there is son of daughter of a prophet on the earth except him." <ref>Lohouf, Tradition No.182</ref> | |||

| The Battle of Karbala was also reported by an early Christian source. A history by the Syriac Christian scholar ], who was chief astrologer in the ] between 775 and 785, is partially preserved in a number of extant Christian chronicles, including those by ] and the Byzantine historian ].{{sfn|Howard-Johnston|2010|pp=195–198}} Theophilus's history corroborates the death in battle of Husayn and most of his men at Karbala after suffering from thirst. But in contrast to all Muslim sources, which state that Husayn fought Yazid, Theophilus appears to have written that Husayn was killed by Muawiyah as the final engagement of the ] between the Umayyads and Ali's supporters.{{sfn|Howard-Johnston|2010|p=386}} | |||

| He became very weak and stopped fighting. The soldiers approaching him gave up confrontation, seeing his position. One soldier, however, walked up to Imam Husayn and hit him on his head with his sword. None wanting to be remembered as the murderer of Hussain ibn Ali. | |||

| ==Historical analysis== | |||

| Umar ibn Sa'ad ordered a man to dismount and to finish the job. Khowali ibn Yazid al-Asbahiy preceded the man but feared and did not do it. While Imam Hussayn was taking rest against the tree, Lanti Shimr knew that Imam Hussayn was unable to fight and sent one of his men to go and kill him. The man went and seeing Imam Hussayn's Eyes, he became extremely frightened and ran back to his camp. When Shimr asked why he hadn't killed Imam Hussayn, the man replied that looking into his eyes he saw the prophet ]. Angrily, Shimr sent another man. This one was so frightened that he dropped his sword and ran back to his camp. This time when Lanti Shimr asked him why he hadn't killed him, he said he saw into his eyes and saw the angry look of Moula ].Lanati Shimr was angry, said that he would have to do it himself and wearing his iron boots, he went to where Imam Hussayn was. Using his iron boots he kicked Imam Hussayn in the ribs. Imam Hussayn fell to the floor, when Shimr disrespected and sat on top of him. Using a blunt knife, he ruggedly dragged it twelve times against Imam Hussayn's throat. Imam Hussayn said "get up! Your blunt knife will not work here, this is the area that was kissed by my mother's father, the Prophet Mohammad! Let me prostrate, and pray for the well being of my people". While his head was down in sujdo, Shimr removed his head from body. | |||

| Based on an official report sent to caliph Yazid, which describes the battle very briefly, stating that it lasted for no longer than a ], Lammens concludes that there was no battle at all but a quick massacre that was over in an hour; he suggests that the detailed accounts found in the primary sources are Iraqi fabrications, since their writers were dissatisfied with their hero being killed without putting up a fight.{{sfn|Lammens|1921|p=169}} This is countered by the historian ], who argues that despite there being some fabricated accounts, all of the contemporary accounts together form "a coherent and credible narrative". She criticizes Lammens' hypothesis as being based on a single isolated report and being devoid of critical analysis.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}} Similarly, Madelung and Wellhausen assert that the battle lasted from sunrise to sunset and that the overall account of the battle is reliable.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}}{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|pp=67–68}} Vaglieri and Madelung explain the length of the battle despite the numerical disparity between the opposing camps as Ibn Sa'd's attempt to prolong the fight and pressure Husayn into submission instead of attempting to quickly overwhelm and kill him.{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|p=610}}{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} | |||

| According to Wellhausen, the compassion that Yazid showed to the family of Husayn, and his cursing of Ibn Ziyad was only for show. He argues that if killing Husayn was a crime its responsibility lay with Yazid and not Ibn Ziyad, who was only performing his duty.{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=70}} Madelung holds a similar view; according to him, early accounts place the responsibility for Husayn's death on Ibn Ziyad instead of Yazid. Yazid, Madelung argues, wanted to end Husayn's opposition, but as a caliph of Islam could not afford to be seen as publicly responsible and so diverted blame onto Ibn Ziyad by hypocritically cursing him.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} According to Howard, some traditional sources have a tendency to exonerate Yazid at the cost of Ibn Ziyad and lower authorities.{{sfn|Howard|1986|pp=131–133}} | |||

| The army of Ibn Sa'ad rushed to loot the tents. The daughters of Mohammad's family were expelled from the tents, unveiled and barefooted, while weeping and crying for their slain relatives. The army set all the tents on fire. The women were asking: "By Allah, will you make us pass the site of the murder of Husayn?" And when they saw the martyrs and wailed.<ref>Lohouf, Tradition No. 209, 211, 213</ref> Then ] (Death, 117 AH) embraced her father's body until some people dragged her away.<ref>Lohouf, Tradition 214</ref> | |||

| ===Modern historical views on motivations of Husayn=== | |||

| Umar ibn Sa'ad called volunteering horsemen to trample Imam Husayn's body. Ten horsemen trampled his body such that his chest and back were ground. | |||

| Wellhausen has described Husayn's revolt as a premature and ill-prepared campaign by an ambitious person. He writes "He reaches out to the moon like a child. He makes the greatest demands and does not do the slightest; the others should do everything... As soon as he encounters resistance, it is over with him; he wants to go back when it is too late."{{sfn|Wellhausen|1901|p=71}} Lammens has agreed to this view and he sees in Husayn a person who disturbs public peace.{{sfn|Lammens|1921|pp=162, 165–166}} According to ], this was a struggle for political leadership between the second generation of Muslims, in which the poorly equipped pretender ended up losing.{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=16}} ], ], and ] see Husayn's revolt as an attempt to regain what his brother Hasan had renounced.{{sfn|Donner|2010|p=178}}{{sfn|Hawting|2000|pp=49–50}}{{sfn|Kennedy|2004|p=89}} | |||

| Vaglieri, on the other hand, considers him to be motivated by ideology, saying that if the materials that have come down to us are authentic, they convey an image of person who is "convinced that he was in the right, stubbornly determined to achieve his ends..."{{sfn|Vaglieri|1971|pp=614–615}} Holding a similar view, Madelung has argued that Husayn was not a "reckless rebel" but a religious man motivated by pious convictions. According to him, Husayn was convinced that "the family of the Prophet was divinely chosen to lead the community founded by Moḥammad, as the latter had been chosen, and had both an inalienable right and an obligation to seek this leadership." He was, however, not seeking martyrdom and wanted to return when his expected support did not materialize.{{sfn|Madelung|2004|pp=493–498}} ] holds that Husayn considered the Umayyad rule oppressive and misguided, and revolted to reorient the Islamic community in the right direction.{{sfn|Dakake|2007|p=82}} A similar view is held by ].{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=93}} ] proposes that Husayn, although motivated by ideology, did not intend to secure leadership for himself. Husayn, Jafri asserts, was from the start aiming for martyrdom in order to jolt the collective conscience of the Muslim community and reveal what he considers to be the oppressive and anti-Islamic nature of the Umayyad regime.{{sfn|Jafri|1979|pp=201–202}} ] sides with Jafri, citing the reports that Husayn was warned about the collapse of the Shia revolt in Kufa. Instead of changing his course, however, he pressed on toward Kufa, urging his supporters to leave him and save their lives.{{Sfn|Momen|1985|pp=31{{ndash}}32}} | |||

| Traditionally, it is believed that Imam Husayn's body was | |||

| martyred but his 'noor' (light) and Imamat were passed on to his son Ali who became | |||

| Imam Ali Zainul Abideen (Sahifa-e-Sajjadiya is a collection of his supplications). | |||

| == |

==Impact== | ||

| ] during '']'']] | |||

| Umar ibn Sa'ad sent Husayn's head to ibn Ziyad on Ashura afternoon and ordered to sever heads of his comrades to send them to Kufa. The heads were distributed to various tribes enabling them to gain favor of ibn Ziyad. Ibn Sa'ad remained in Karbala until the next noon.<ref>Lohouf, Tradition No. 222, 223</ref> | |||

| The killing of the grandson of Muhammad shocked the Muslim community.{{sfn|Kennedy|2004|p=89}} The image of Yazid suffered and gave rise to sentiment that he was impious.{{sfn|Donner|2010|p=179}} The event has had an emotional impact on Sunnis,{{sfn|Hawting|2000|p=50}} who remember the event as a tragic incident and those killed in the company of Husayn as martyrs.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|pp=134–135}} The impact on Shi'a Islam has been much deeper.{{sfn|Hawting|2000|p=50}}{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|pp=134–135}} | |||

| ===Shi'a Islam=== | |||

| After ibn Sa'ad's army went out of ], some people from Banu Asad tribe came there and buried their dead.<ref>Lohouf, Tradition No. 226</ref> | |||

| Prior to the Battle of Karbala, the Muslim community was divided into two political factions. Nonetheless, a religious sect with distinct theological doctrines and specific set of rituals had not developed.{{sfn|Donner|2010|p=178}}{{sfn|Kennedy|2004|p=89}}{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=108}} Karbala gave this early political party of pro-Alids a distinct religious identity and helped transform it into a distinct religious sect.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=161}}{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=16}} Heinz Halm writes: "There was no religious aspect to Shi'ism prior to 680. The death of the third imam and his followers marked the 'big bang' that created the rapidly expanding cosmos of Shi'ism and brought it into motion."{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=16}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Husayn's death at Karbala is believed by Shi'as to be a sacrifice made to prevent the corruption of Islam by tyrannical rulers and to protect its ideology.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=162}} He is, as such, believed to have been fully aware of his fate and the outcome of his revolt, which was divinely ordained.{{sfn|Brunner|2013|p=293}} He is thus remembered as the prince of martyrs (''Sayyed al-Shuhada'').{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=161}} The historian G. R. Hawting describes the Battle of Karbala as a "supreme" example of "suffering and martyrdom" for Shi'as.{{sfn|Hawting|2000|p=50}} According to ], it is seen by Shi'as the climax of suffering and oppression, revenge for which came to be one of the primary goals of many Shi'a uprisings. This revenge is believed to be one of the fundamental objectives of the future revolution of the twelfth Shi'a Imam ], whose return is awaited.{{sfn|Sachedina|1981|pp=157–158}} With his return, Husayn and his seventy-two companions are expected to be resurrected along with their killers, who will then be punished.{{sfn|Sachedina|1981|pp=62, 165–166}} | |||

| On ] 11 (October 11, 680 CE), all captives including all women and children were then loaded onto camels with neither saddle nor shade and were moved toward Kufa. As they approached Kufa, its people gathered to see them. Some women of Kufa gathered veils for them upon knowing that they are relatives of ]. Among the captives were Hazrat ], who was gravely ill, as well as Hazrat Hassan ibn Hassan al-Muthanna, who was seriously injured in the battle of Karbala.<ref>Lohouf, Tradition No. 227, 228, 229, 230</ref> | |||

| ====Shi'a observances==== | |||

| ] pointed at the people to be quiet. Then she addressed the people of Kufa: <blockquote>"The praise is exclusively attributed to Allah. And greetings to my father (grand father), Muhammad, and to his pure and benevolent family. And then, Oh people of Kufa! Oh deceitful and reneger people! Do you weep? So let tears not be dried and let groans not be finished. ... Beware, such a bad preparation you have made for yourself that Allah became furious of you and you will be at punishment forever. Do you weep and cry? Yeah, by Allah, do weep numerously and do laugh less! Since you brought its shame and fault on yourself and you will not be able to cleanse it forever. ..."<ref>الحمد لله و الصلوة علی ابی محمد و آله الطیبین الاخیار. اما بعد یا اهل الکوفة! یا اهل الختل و الغدر! اتبکون؟ فلا رقات الدمعة و لا هدات الرنة ... الا ساء ما قدمت لکم انفسکم ان سخط الله علیکم و فی العذاب انتم خالدون. اتبکون و تنتحبون؟ ای والله فابکوا کثیرا و اضحکوا قلیلا فلقد ذهبتم بعارها و شنارها و لن ترحضوها بغسل بعدها ابدا. ... Lohouf, Tradition No. 233 to 241</ref> </blockquote> | |||

| {{main|Mourning of Muharram}} | |||

| Shi'a Muslims consider pilgrimages to ] to be a source of divine blessings and rewards.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=167}} According to Shi'a tradition the first such visit was performed by Husayn's son Ali Zayn al-Abidin and the surviving family members during their return from Syria to Medina. The first historically recorded visit is Sulayman ibn Surad and the Penitents going to Husayn's grave before their departure to Syria. They are reported to have lamented and beaten their chests and to have spent a night by the tomb.{{sfn|Calmard|2004|pp=498–502}} Thereafter this tradition was limited to the Shi'a imams for several decades, before gaining momentum under the sixth Shi'a imam ] and his followers. ] and ] also encouraged this practice.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=167}} Special visits are paid on 10 Muharram ('']'' Pilgrimage) and 40 days after the anniversary of Husayn's (]).{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=163}} The soil of Karbala is considered to have miraculous healing effects.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=167}} | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| Mourning for Husayn is considered by Shi'as to be a source of salvation in the afterlife,{{sfn|Aghaie|2004|pp=9–10}} and is undertaken as a remembrance of his suffering.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|pp=143–144}} After the death of Husayn, when his family was being taken to Ibn Ziyad, Husayn's sister Zaynab is reported to have cried out after seeing his headless body: "O Muhammad!... Here is Husayn in the open, stained with blood and with limbs torn off. O Muhammad! Your daughters are prisoners, your progeny are killed, and the east wind blows dust over them."{{sfn|Howard|1990|p=164}} Shi'a Muslims consider this to be the first instance of wailing and mourning over the death of Husayn.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=163}} Husayn's son Zayn al-Abideen is reported to have spent the rest of his life weeping for his father. Similarly, Husayn's mother ] is believed to be weeping for him in paradise and the weeping of believers is considered to be a way of sharing her sorrows.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|pp=143–144}} Special gatherings (''majalis''; sing. ''majlis'') are arranged in places reserved for this purpose, called '']''.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=163}} In these gatherings the story of Karbala is narrated and various elegies (''rawda'') are recited by professional reciters (''rawda khwan'').{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=164}} | |||

| During the journey from Karbala to Kufa, and from Kufa to Damascus, Husayn's sister Zaynab bint Ali and Umm-Kulthoom bint Ali, and son Ali ibn Husayn gave various speeches that exposed the truth about Yazid and told the Muslim world of the various atrocities committed in Karbala. After being brought to Yazid's court, Zaynab courageously gave a famous speech in which she denounced Yazid's claim to the caliphate and eulogized Husayn's uprising. | |||

| ]'' in a Muaharram procession]] | |||

| During the month of Muharram, elaborate public processions are performed in commemoration of the Battle of Karbala. In contrast to pilgrimage to Husayn's tomb and simple lamenting, these processions do not date back to the time of the battle, but arose during tenth century. Their earliest recorded instance was in Baghdad in 963 during the reign of the first Buyid ruler ].{{sfn|Aghaie|2004|p=10}} The processions start from a ''husayniyya'' and the participants parade barefoot through the streets, wailing and beating their chests and heads before returning to the ''husayniyya'' for a ''majlis''.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|p=169}}{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=154}} Sometimes, chains and knives are used to inflict wounds and physical pain.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|pp=154–155}} In ], an ornately ] horse called '']'', representing Husayn's battle horse, is also led riderless through the streets.{{sfn|Pinault|2001|p=113}} In Iran, the battle scenes of Karbala are performed on stage in front of an audience in a ritual called '']'' (passion play), also known as ''shabih''.{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=63}}{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=155}} In India however, ''taziya'' refers to the coffins and replicas of Husayn's tomb carried in processions.{{sfn|Halm|1997|p=63}}{{sfn|Pinault|2001|p=18}} | |||

| The prisoners were held in Damascus for a year. During this year, some prisoners died of grief, most notably ]. The people of Damascus began to frequent the prison, and Zaynab and Ali ibn Husayn used that as an opportunity to further propagate the message of Husayn and explain to the people the reason for Husayn's uprising. As public opinion against Yazid began to foment in Syria and parts of Iraq, Yazid ordered their release and return to Medina, where they continued to tell the world of Husayn's cause. | |||

| Most of these rituals take place during the first ten days of Muharram, reaching a climax on the tenth day, although ''majalis'' can also occur throughout the year.{{sfn|Ayoub|1978|p=155}}{{sfn|Halm|1997|pp=61–62}} Occasionally, especially in the past, some Sunni participation in ''majalis'' and processions has been observed.{{sfn|Aghaie|2004|p=14}}{{sfn|Hyder|2006|p=21}} According to ], the rituals of Muharram have an "important" effect in the "invoking the memory of Karbala", as these help consolidate the collective identity and memory of the Shi'a community.{{sfn|Nakash|1993|pp=165, 181}} Anthropologist ] states that commemoration of the Battle of Karbala by the Shi'a is not only the retelling of the story, but also presents them with "life models and norms of behavior" which are applicable to all aspects of life, which he calls the Karbala Paradigm.{{sfn|Gölz|2019|pp=39–40}} According to Olmo Gölz, the Karbala Paradigm provide Shi'as with heroic norms and a martyr ethos, and represents an embodiment of the battle between good and evil, justice and injustice.{{sfn|Gölz|2019|p=41}} Rituals involving self-flagellation have been criticized by many Shi'a scholars as they are considered to be ] damaging reputation of Shi'ism. Iranian supreme leader ] has banned the practice in Iran since 1994.{{sfn|Brunner|2013|p=293}} | |||

| ==Historiography of the battle of Karbala== | |||

| {{See also|Maqtal Al-Husayn}} | |||

| === |

===Politics=== | ||

| {{multiple image | |||

| The first historian to systematically collect the reports of eyewithnesses of this event was ] (died in 157 AH, 774 CE) in a work titled "'''Kitab Maqtal Al-Husayn'''".<ref name=autogenerated3></ref> | |||

| | align = right | |||

| Abi Mikhnaf's original seems to have been lost and that which has reached today has been transmitted through his student Hisham Al-Kalbi (died in 204 AH.) There are four manuscripts of the Maqtal, located at Gotha (No. 1836), Berlin (Sprenger, Nos. 159-160), Leiden (No. 792), and St. Petersburg (Am No. 78) libraries.<ref>Syed Husayn M. Jafri, "The Origins and Early Development of Shi'a Islam", Oxford University Press, USA (April 4, 2002), ISBN 978-0195793871</ref> | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 220 | |||

| | image1 = Mourning of Muharram in cities and villages of Iran-342 16 (136).jpg | |||

| | caption1 = '']'' in Iran | |||

| | image2 = Muharram (Ta'ziya) procession Barabanki India (Jan 2009).jpg | |||

| | caption2 = ''Taziya'' in India | |||

| }} | |||