| Revision as of 00:27, 24 December 2010 editDCGeist (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users34,204 edits →Punk revival: cite← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:48, 20 January 2025 edit undoRodw (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers775,437 editsm Disambiguating links to Big Boy (link changed to Big Boys (band)) using DisamAssist. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Genre of rock music}} | |||

| {{about|the music genre|the ] play of the same name|Punk Rock (play)}} | |||

| {{ |

{{other uses}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=October 2024}} | |||

| '''Punk rock''' is a ] genre that developed between 1974 and 1976 in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Rooted in ] and other forms of what is now known as ] music, punk rock bands eschewed the perceived excesses of mainstream 1970s rock. They created fast, hard-edged music, typically with short songs, stripped-down instrumentation, and often political, ] lyrics. Punk embraces a ] (do it yourself) ethic, with many bands self-producing their recordings and distributing them through informal channels. | |||

| {{Infobox music genre | |||

| | name = Punk rock | |||

| | other_names = Punk | |||

| | image = | |||

| | caption = | |||

| | stylistic_origins = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | cultural_origins = Mid-1970s, United States, United Kingdom, and Australia | |||

| | derivatives = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | subgenrelist = Punk rock subgenres | |||

| | subgenres = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | fusiongenres = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]<ref name="allmusic grunge">{{cite web |url=http://www.allmusic.com/style/grunge-ma0000002626 |title=Grunge |access-date=August 24, 2012 |website=] |archive-date=January 18, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170118220936/http://www.allmusic.com/style/grunge-ma0000002626 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | regional_scenes = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | local_scenes = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | other_topics = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Anarchism sidebar}} | |||

| '''Punk rock''' (also known as simply '''punk''') is a ] genre that emerged in the mid-1970s. Rooted in 1950s ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=A Short History of How Punk Became Punk: From Late 50s Rockabilly and Garage Rock to The Ramones & Sex Pistols {{!}} Open Culture |url=https://www.openculture.com/2019/02/a-short-history-of-punk-from-late-50s-rockabilly-and-garage-rock-to-the-ramones-sex-pistols.html |access-date=2023-11-24 |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Stegall |first=Tim |date=August 16, 2021 |title=10 rockers from the '50s who influenced rock 'n' roll, punk and more |url=https://www.altpress.com/rockabilly-influence-on-punk-elvis-johnny-cash-jerry-lee-lewis/ |access-date=2023-11-24 |website=Alternative Press Magazine |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Palmer |first=Robert |date=April 23, 1978 |title=Punks Have Only Re 'scovered Rockabilly |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1978/04/23/archives/the-punks-have-only-rediscovered-rockabilly-punk-and-rockabilly.html |access-date=2023-11-24 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> and 1960s ], punk bands rejected the corporate nature of mainstream 1970s rock music. They typically produced short, fast-paced songs with hard-edged melodies and singing styles with stripped-down instrumentation. Lyricism in punk typically revolves around ] and ] themes. Punk embraces a ]; many bands self-produce recordings and distribute them through ]s. | |||

| By late 1976, bands such as the ], in New York City, and the ] and ], in London, were recognized as the vanguard of a new musical movement. The following year saw punk rock spreading around the world, and it became a major cultural phenomenon in the United Kingdom. For the most part, punk took root in local scenes that tended to reject association with the mainstream. An associated ] emerged, expressing youthful rebellion and characterized by distinctive ] and a variety of ]. | |||

| The term "punk rock" was previously used by American ] in the early 1970s to describe the mid-1960s garage bands. Certain late 1960s and early 1970s Detroit acts, such as ] and ], and other bands from elsewhere created out-of-the-mainstream music that became highly influential on what was to come. ] in the UK and ] from New York have also been cited as key influences. Between 1974 and 1976, when the genre that became known as punk was developing, prominent acts included ], ], ], and the ] in New York City; ] in ]; the ], ], and ] in London, and the ] in Manchester. By late 1976, punk had become a major cultural phenomenon in the UK. It gave rise to a ] that expressed youthful rebellion through distinctive ], such as T-shirts with deliberately offensive graphics, leather jackets, studded or spiked bands and jewelry, safety pins, and bondage and S&M clothes. | |||

| By the beginning of the 1980s, faster, more aggressive styles such as ] and ] had become the predominant mode of punk rock. Musicians identifying with or inspired by punk also pursued a broad range of other variations, giving rise to ] and the ] movement. By the turn of the century, ] had been adopted by the mainstream, as bands such as ] and ] brought the genre widespread popularity. | |||

| In 1977, the influence of the music and subculture spread worldwide. It took root in a wide range of local scenes that often rejected affiliation with the mainstream. In the late 1970s, punk experienced a second wave, when new acts that had not been active during its formative years adopted the style. By the early 1980s, faster and more aggressive subgenres, such as ] (e.g., ]), ] (e.g., ]), ] (e.g., ]), and ] (e.g., ]), became some of the predominant modes of punk rock, while bands more similar in form to the first wave (e.g., ], ]) also flourished. Many musicians who identified with punk or were inspired by it went on to pursue other musical directions, giving rise to movements such as ], ], ], and ]. Following alternative rock's mainstream breakthrough in the 1990s with ], punk rock saw renewed major-label interest and mainstream appeal exemplified by the rise of the California bands ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ==Characteristics== | |||

| ===Philosophy=== | |||

| ]' 1976 ] laid down the musical "blueprint for punk",<ref>Erlewine, Stephen Thomas, , ''Allmusic''. Retrieved on October 11, 2007.</ref> while its cover image had a similarly formative influence on punk visual style.<ref name=RamonesCover>Bessman (1993), pp. 48, 50; Miles, Scott, and Morgan (2005), p. 136.</ref>]] | |||

| The first wave of punk rock aimed to be aggressively modern, distancing itself from the bombast and sentimentality of early 1970s rock.<ref name="RMB">Robb (2006), foreword by Michael Bracewell.</ref> According to ] drummer ], "In its initial form, a lot of stuff was innovative and exciting. Unfortunately, what happens is that people who could not hold a candle to the likes of ] started noodling away. Soon you had endless solos that went nowhere. By 1973, I knew that what was needed was some pure, stripped down, no bullshit rock 'n' roll."<ref>Ramone, Tommy, "Fight Club", '']'', January 2007.</ref> ], founding editor of '']'' magazine, recalls feeling "punk rock had to come along because the rock scene had become so tame that like ] and ] were being called rock and roll, when to me and other fans, rock and roll meant this wild and rebellious music."<ref name="MM">McLaren, Malcolm, , BBC News, August 18, 2006. Retrieved on January 17, 2006.</ref> In critic ]'s description, "It was also a subculture that scornfully rejected the political idealism and Californian flower-power silliness of hippie myth."<ref>Christgau, Robert, , ''New York Times Book Review'', 1996. Retrieved on January 17, 2007.</ref> ], in contrast, suggests in the documentary ''25 Years of Punk'' that the hippies and the punk rockers were linked by a common anti-establishment mentality. | |||

| The anti-government stance and nihilistic impression of the future provided by capitalism united the punk scene in the 1970s in the United Kingdom as other bands emerged in the 70s and 80s like X-Ray Spex and Steel Pulse. | |||

| Throughout punk rock history, technical accessibility and a ] spirit have been prized. In the early days of punk rock, this ethic stood in marked contrast to what those in the scene regarded as the ostentatious musical effects and technological demands of many mainstream rock bands.<ref>See, e.g., Rodel (2004), p. 237; Bennett (2001), pp. 49–50.</ref> Musical virtuosity was often looked on with suspicion. According to Holmstrom, punk rock was "rock and roll by people who didn't have very much skills as musicians but still felt the need to express themselves through music".<ref name="MM"/> In December 1976, the English ] ''Sideburns'' published a now-famous illustration of three chords, captioned "This is a chord, this is another, this is a third. Now form a band."<ref>Savage (1992), pp. 280–281, including reproduction of the original image. Several sources incorrectly ascribe the illustration to the leading fanzine of the London punk scene, '']'' (e.g., Wells , p. 5; Sabin , p. 111). Robb (2006) ascribes it to ]' in-house fanzine, ''Strangled'' (p. 311). In fact, ''Strangled'', which only began appearing in 1977, evolved out of ''Sideburns'' (see, e.g., {{cite web|url=http://www.xulucomics.com/strangled.html|title=''Strangled'' |publisher=Xulu Brand Comics|accessdate=2009-03-19}})</ref> The title of a 1980 single by New York punk band The Stimulators, "Loud Fast Rules!", inscribed a catchphrase for punk's basic musical approach.<ref>Blush (2001), pp. 173, 175. See also Killed By Death Records (September 21, 2006).</ref> | |||

| == Characteristics == | |||

| Some of British punk rock's leading figures made a show of rejecting not only contemporary mainstream rock and the broader culture it was associated with, but their own most celebrated predecessors: "No ], ] or the ] in 1977", declared ] song "1977".<ref>Harris (2004), p. 202.</ref> The previous year, when the punk rock revolution began in Great Britain, was to be both a musical and a cultural "Year Zero".<ref name = "Reynolds p4">Reynolds (2005), p. 4.</ref> Even as nostalgia was discarded, many in the scene adopted a ] attitude summed up by the ] slogan "No Future";<ref name="RMB"/> in the later words of one observer, amid the unemployment and social unrest in 1977, "punk's nihilistic swagger was the most thrilling thing in England."<ref>Jeffries, Stuart. "A Right Royal Knees-Up". ''The Guardian''. July 20, 2007.</ref> While "self-imposed ]" was common among "drunk punks" and "gutter punks", there was always a tension between their nihilistic outlook and the "radical leftist utopianism"<ref>Washburne, Christopher, and Maiken Derno. ''Bad Music''. Routledge, 2004. Page 247.</ref> of bands such as ], who found positive, liberating meaning in the movement. As a Clash associate describes singer ]'s outlook, "Punk rock is meant to be our freedom. We're meant to be able to do what we want to do."<ref>Kosmo Vinyl, ''The Last Testament: The Making of London Calling'' (Sony Music, 2004).</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Punk subculture}} | |||

| <!-- not combined because a different direction for the reader --><!-- note deorphaning --> | |||

| ===Outlook=== | |||

| The issue of authenticity is important in the punk subculture—the pejorative term "]" is applied to those who associate with punk and adopt its stylistic attributes but are deemed not to share or understand the underlying values and philosophy. Scholar Daniel S. Traber argues that "attaining authenticity in the punk identity can be difficult"; as the punk scene matured, he observes, eventually "veryone got called a poseur".<ref>Traber, Daniel S., "L.A.'s 'White Minority': Punk and the Contradictions of Self-Marginalization", ''Cultural Critique'' 48 (spring 2001), pp. 30–64.</ref> | |||

| The first wave of punk rock was "aggressively modern" and differed from what came before.<ref name="RMB">Robb (2006), p. xi.</ref> According to ] drummer ], "In its initial form, a lot of 1960s stuff was innovative and exciting. Unfortunately, what happens is that people who could not hold a candle to the likes of ] started noodling away. Soon you had endless ] that went nowhere. By 1973, I knew that what was needed was some pure, stripped down, no bullshit rock 'n' roll."<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Ramone |first=Tommy |title=Fight Club |magazine=] |date=January 2007}}</ref> ], founding editor of '']'' magazine, recalls feeling "punk rock had to come along because the rock scene had become so tame that like ] and ] were being called rock and roll, when to me and other fans, rock and roll meant this wild and rebellious music."<ref name="MM">{{cite web |last=McLaren |first=Malcolm |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/5263364.stm |title=Punk Celebrates 30 Years of Subversion |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200115073013/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/5263364.stm |archive-date=January 15, 2020 |work=] |date=August 18, 2006 |access-date=January 17, 2007}}</ref> According to ], punk "scornfully rejected the political idealism and Californian flower-power silliness of ] myth."<ref>{{cite news |last=Christgau |first=Robert |author-link=Robert Christgau |url=http://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/bkrev/mcneil-nyt.php |title="Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain" (review) |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191020182250/http://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/bkrev/mcneil-nyt.php |archive-date=October 20, 2019 |work=] Book Review |date=1996 |access-date=January 17, 2007}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote box|quoted=1|quote=Hippies were rainbow extremists; punks are romantics of black-and-white. Hippies forced warmth; punks cultivate ]. Hippies kidded themselves about ]; punks pretend that ] is our condition. As symbols of protest, swastikas are no less fatuous than flowers.|source=—] in '']'' (1981)<ref>{{cite book |last=Christgau |first=Robert |author-link=Robert Christgau |year=1981 |title=Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies |publisher=] |isbn=978-0899190266 |chapter=Consumer Guide '70s: S |chapter-url=https://www.robertchristgau.com/get_chap.php?k=S&bk=70 |access-date=February 21, 2019|title-link=Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies |archive-date=April 13, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190413002147/https://www.robertchristgau.com/get_chap.php?k=S&bk=70 |url-status=live}}</ref>|width=20%|align=right|style=padding:8px;}} | |||

| ===Musical and lyrical elements=== | |||

| Punk rock bands often emulate the bare musical structures and arrangements of 1960s ].<ref>Murphy, Peter, "Shine On, The Lights Of The Bowery: The Blank Generation Revisited", ''Hot Press'', July 12, 2002; ], "Richard Hell: King Punk Remembers the Generation", '']'', March 2002.</ref> Typical punk rock instrumentation includes one or two electric guitars, an electric bass, and a drum kit, along with vocals. Punk rock songs tend to be shorter than those of other popular genres—on the Ramones' ], for instance, half of the fourteen tracks are under two minutes long. Most early punk rock songs retained a traditional rock 'n' roll ] and 4/4 ]. However, punk rock bands in the movement's second wave and afterward have often broken from this format. In critic Steven Blush's description, "The Sex Pistols were still rock'n'roll...like the craziest version of ]. ] was a radical departure from that. It wasn't verse-chorus rock. It dispelled any notion of what songwriting is supposed to be. It's its own form."<ref name="blush">Blush, Steven, "Move Over My Chemical Romance: The Dynamic Beginnings of US Punk", '']'', January 2007.</ref> | |||

| Technical accessibility and a ] (DIY) spirit are prized in punk rock. ] from 1972 to 1975 contributed to the emergence of punk rock by developing a network of small venues, such as pubs, where non-mainstream bands could play.<ref name="Laing, Dave 2015. p. 18">{{cite book |last=Laing |first=Dave |title=One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock |publisher=] |date=2015 |page=18}}</ref> Pub rock also introduced the idea of ]s, such as ], which put out basic, low-cost records.<ref name="Laing, Dave 2015. p. 18"/> Pub rock bands organized their own small venue tours and put out small pressings of their records. In the early days of punk rock, this DIY ethic stood in marked contrast to what those in the scene regarded as the ostentatious musical effects and technological demands of many mainstream rock bands.<ref>Rodel (2004), p. 237; Bennett (2001), pp. 49–50.</ref> Musical virtuosity was often looked on with suspicion. According to Holmstrom, punk rock was "rock and roll by people who didn't have very many skills as musicians but still felt the need to express themselves through music".<ref name="MM"/> In December 1976, the English ] ''Sideburns'' published a now-famous illustration of three chords, captioned "This is a chord, this is another, this is a third. Now form a band".<ref>Savage (1992), pp. 280–281, including reproduction of the original image. Several sources incorrectly ascribe the illustration to the leading fanzine of the London punk scene, '']'' (e.g., Wells , p. 5; Sabin , p. 111). Robb (2006) ascribes it to ]' in-house fanzine, ''Strangled'' (p. 311).</ref> | |||

| Punk rock vocals sometimes sound nasal,<ref>Wells (2004), p. 41; Reed (2005), p. 47.</ref> and lyrics are often shouted instead of sung in a conventional sense, particularly in hardcore styles.<ref name="S159">Shuker (2002), p. 159.</ref> The vocal approach is characterized by a lack of variety; shifts in pitch, volume, or intonational style are relatively infrequent—the Sex Pistols' ] constitutes a significant exception.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 58; Reynolds (2005), p. ix.</ref> Complicated guitar solos are considered self-indulgent and unnecessary, although basic guitar breaks are common.<ref>Chong, Kevin, , Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, August 2006. Retrieved on December 17, 2006.</ref> Guitar parts tend to include highly distorted ] or ], creating a characteristic sound described by Christgau as a "buzzsaw drone".<ref>Quoted in Laing (1985), p. 62.</ref> Some punk rock bands take a ] approach with a lighter, twangier guitar tone. Others, such as ], lead guitarist of ], have employed a wild, "]" attack, a style that stretches back through ] to the 1950s recordings of ].<ref>Palmer (1992), p. 37.</ref> Bass guitar lines are often uncomplicated; the quintessential approach is a relentless, repetitive "forced rhythm",<ref>Laing (1985), p. 62.</ref> although some punk rock bass players—such as ] of ] and ]—emphasize more technical bass lines. Bassists often use a ] due to the rapid succession of notes, which makes ] impractical. Drums typically sound heavy and dry, and often have a minimal set-up. Compared to other forms of rock, ] is much less the rule.<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 61–63.</ref> Hardcore drumming tends to be especially fast.<ref name="S159"/> Production tends to be minimalistic, with tracks sometimes laid down on home tape recorders<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 118–119.</ref> or simple four-track portastudios. The typical objective is to have the recording sound unmanipulated and "real", reflecting the commitment and "authenticity" of a live performance.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 53.</ref> Punk recordings thus often have a ] quality, with the sound left relatively unpolished in the ] process; recordings may contain dialogue between band members, false starts, and background noise. | |||

| British punk rejected contemporary mainstream rock, the broader culture it represented, and their musical predecessors: "No ], ] or ] in 1977", declared ] song "1977".<ref>Harris (2004), p. 202.</ref> 1976, when the punk revolution began in Britain, became a musical and a cultural "Year Zero".<ref name="Reynolds p4">Reynolds (2005), p. 4.</ref> As nostalgia was discarded, many in the scene adopted a ] attitude summed up by the ]' slogan "No Future";<ref name="RMB"/> in the later words of one observer, amid the unemployment and social unrest in 1977, "punk's nihilistic swagger was the most thrilling thing in England."<ref>Jeffries, Stuart. "A Right Royal Knees-Up". ''The Guardian''. July 20, 2007.</ref> While "self-imposed ]" was common among "drunk punks" and "gutter punks", there was always a tension between their nihilistic outlook and the "radical leftist utopianism"<ref>Washburne, Christopher, and Maiken Derno. ''Bad Music''. Routledge, 2004. Page 247.</ref> of bands such as ], who found positive, liberating meaning in the movement. As a Clash associate describes singer ]'s outlook, "Punk rock is meant to be our freedom. We're meant to be able to do what we want to do."<ref>{{cite book |author=Kosmo Vinyl |title=The Last Testament: The Making of London Calling |publisher=Sony Music |date=2004}}</ref> | |||

| ], performing in 1980]] | |||

| Punk rock lyrics are typically frank and confrontational; compared to the lyrics of other popular music genres, they frequently comment on social and political issues.<ref>Sabin (1999), pp. 4, 226; Dalton, Stephen, "Revolution Rock", ''Vox'', June 1993. See also Laing (1985), pp. 27–32, for a statistical comparison of lyrical themes.</ref> Trend-setting songs such as The Clash's "]" and ] "Right to Work" deal with unemployment and the grim realities of urban life.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 31.</ref> Especially in early British punk, a central goal was to outrage and shock the mainstream.<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 81, 125.</ref> The Sex Pistols classics "]" and "]" openly disparage the British political system and social mores. There is also a characteristic strain of anti-sentimental depictions of relationships and sex, exemplified by "Love Comes in Spurts", written by ] and recorded by him with The Voidoids. ], variously expressed in the poetic terms of Hell's "]" and the bluntness of the Ramones' "Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue", is a common theme. Identifying punk with such topics aligns with the view expressed by ], founder of San Francisco fanzine '']'': "Punk was a total cultural revolt. It was a hardcore confrontation with the black side of history and culture, right-wing imagery, sexual taboos, a delving into it that had never been done before by any generation in such a thorough way."<ref>Quoted in Savage (1991), p. 440. See also Laing (1985), pp. 27–32.</ref> However, many punk rock lyrics deal in more traditional rock 'n' roll themes of courtship, heartbreak, and hanging out; the approach ranges from the deadpan, aggressive simplicity of Ramones standards such as "I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend"<ref>{{cite web|author=Segal, David|title=Punk's Pioneer|work=Washington Post|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn?pagename=article&node=digest&contentId=A25121-2001Apr16|date=2001-04-17|accessdate=2007-10-23}}</ref> to the more unambiguously sincere style of many later pop punk groups. | |||

| ] has always been important in the punk subculture—the pejorative term "]" is applied to those who adopt its stylistic attributes but do not actually share or understand its underlying values and philosophy. Scholar Daniel S. Traber argues that "attaining authenticity in the punk identity can be difficult"; as the punk scene matured, he observes, eventually "everyone got called a poseur".<ref>{{cite journal |pages=30–64 |doi=10.1353/cul.2001.0040 |title=L.A.'s 'White Minority': Punk and the Contradictions of Self-Marginalization |year=2001 |last1=Traber |first1=Daniel S. |journal=Cultural Critique |volume=48|s2cid=144067070 | issn=0882-4371}}</ref> Cultural scholars and music journalists have often attributed 'true' punk rock as a movement and cultural fad confined to western world in the 1970s and 1980s. | |||

| === Musical and lyrical elements === | |||

| The early punk bands emulated the minimal musical arrangements of 1960s ].<ref>Murphy, Peter, "Shine On, The Lights Of The Bowery: The Blank Generation Revisited", ''Hot Press'', July 12, 2002; ], "Richard Hell: King Punk Remembers the Generation", '']'', March 2002.</ref> Typical punk rock instrumentation is stripped down to one or two guitars, bass, drums and vocals. Songs tend to be shorter than those of other rock genres and played at fast tempos.<ref>Laing, Dave. ''One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock''. PM Press, 2015. p. 80</ref> Most early punk rock songs retained a traditional rock 'n' roll ] and 4/4 ]. However, later bands often broke from this format.<ref name="blush">], "Move Over My Chemical Romance: The Dynamic Beginnings of US Punk", '']'', January 2007.</ref> Punk music was not a standalone movement in the 70s and 80s. Major punk communities gather across the globe as punk perseveres among contemporary musicians and listeners today. | |||

| The vocals are sometimes nasal,<ref>Wells (2004), p. 41; Reed (2005), p. 47.</ref> and the lyrics often shouted in an "arrogant snarl", rather than conventionally sung.<ref name="S159">Shuker (2002), p. 159.</ref><ref name="laing 21">Laing, Dave. ''One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock''. PM Press, 2015. p. 21</ref> Complicated ]s were considered self-indulgent, although basic guitar breaks were common.<ref>Chong, Kevin, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101203054425/http://www.cbc.ca/arts/music/guitarsolos.html |date=December 3, 2010 }}, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, August 2006. Retrieved on December 17, 2006.</ref> Guitar parts tend to include highly ] ]s or ]s, creating a characteristic sound described by Christgau as a "buzzsaw drone".<ref>Quoted in {{harvp|Laing|1985|p=62}}</ref> Some punk rock bands take a ] approach with a lighter, twangier guitar tone. Others, such as ], lead guitarist of ], have employed a wild, "]" attack, a style that stretches back through ] to the 1950s recordings of ].<ref>Palmer (1992), p. 37.</ref> Bass guitar lines are often uncomplicated; the quintessential approach is a relentless, repetitive "forced rhythm",{{sfn|Laing|1985|p=62}} although some punk rock bass players—such as ] of ] and ]—emphasize more technical bass lines. Bassists often use a ] due to the rapid succession of notes, making ] impractical. Drums typically sound heavy and dry, and often have a minimal set-up. Compared to other forms of rock, ] is much less the rule.<ref>{{harvp|Laing|1985|pp=61–63}}</ref> Hardcore drumming tends to be especially fast.<ref name="S159" /> Production tends to be minimalistic, with tracks sometimes laid down on home tape recorders{{sfn|Laing|1985|pp=118–19}} or four-track portastudios.{{sfn|Laing|1985|p=53}} | |||

| Punk rock lyrics are typically blunt and confrontational; compared to the lyrics of other popular music genres, they often focus on social and political issues.<ref>Sabin (1999), pp. 4, 226; Dalton, Stephen, "Revolution Rock", ''Vox'', June 1993. See also Laing (1985), pp. 27–32, for a statistical comparison of lyrical themes.</ref> Trend-setting songs such as the Clash's "]" and ]'s "Right to Work" deal with unemployment and the grim realities of urban life.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 31.</ref> Especially in early British punk, a central goal was to outrage and shock the mainstream.<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 81, 125.</ref> The Sex Pistols' "]" and "]" openly disparaged the British political system and social mores. Anti-sentimental depictions of relationships and sex are common, as in "Love Comes in Spurts", recorded by the ]. ], variously expressed in the poetic terms of Richard Hell's "]" and the bluntness of the Ramones' "]", is a common theme.<ref>Savage (1991), p. 440. See also Laing (1985), pp. 27–32.</ref> The controversial content of punk lyrics has frequently led to certain punk records being banned by radio stations and refused shelf space in major chain stores.<ref>Laing, Dave. ''One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock''. PM Press, 2015. p. 7</ref> Christgau said that "Punk is so tied up with the disillusions of growing up that punks do often age poorly."<ref>{{cite web|last=Christgau|first=Robert|date=April 14, 2021|url=https://robertchristgau.substack.com/p/xgau-sez-april-2021|title=Xgau Sez: April, 2021|work=And It Don't Stop|publisher=]|access-date=April 17, 2021|url-access=subscription|archive-date=April 17, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210417124959/https://robertchristgau.substack.com/p/xgau-sez-april-2021|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Visual and other elements=== | ===Visual and other elements=== | ||

| {{Further|Punk fashion}} | |||

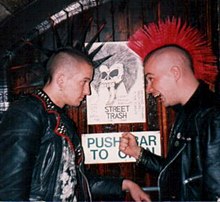

| The classic punk rock look among male U.S. musicians harkens back to the T-shirt, motorcycle jacket, and jeans ensemble favored by American ] of the 1950s associated with the ] scene and by British ] of the 1960s. The cover of the Ramones' 1976 debut album, featuring a shot of the band by ''Punk'' photographer Roberta Bayley, set forth the basic elements of a style that was soon widely emulated by rock musicians both punk and nonpunk.<ref name=RamonesCover/> Richard Hell's more androgynous, ragamuffin look—and reputed invention of the ]—was a major influence on Sex Pistols impresario ] and, in turn, British punk style.<ref name="RHV">{{cite web|author=Grant, Steven, Fleischmann, Mark; Sprague, David; Robbins, Ira |title=Richard Hell & the Voidoids|author=Isler, Scott; Robbins, Ira |work=]|url=http://www.trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=richard_hell_and_the_voidoids|accessdate=2007-10-23}}</ref><ref>Strongman (2008), pp. 58, 63, 64; Colegrave and Sullivan (2005), p. 78.</ref> (John Morton of Cleveland's ] may have been the first rock musician to wear a safety-pin-covered jacket.<ref>See {{cite web|author=Weldon, Michael|title=Electric Eels: Attendance Required |url=http://www.cleveland.com/music/index_story.ssf?/music/more/local/cle/2/index.html|publisher=Cleveland.com|accessdate=19 December 2010}}</ref>) McLaren's partner, fashion designer ], credits Johnny Rotten as the first British punk to rip his shirt, and Sex Pistols bassist ] as the first to use safety pins.<ref>{{cite web | author= Young, Charles M.| date= October 20, 1977| title=Rock Is Sick and Living in London| work=Rolling Stone| url=http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/thebeatles/articles/story/9437647/sex_pistols_rock_is_sick_and_living_in_london?source=thebeatles_rssfeed | accessdate=10 October 2006|archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060914225550/http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/thebeatles/articles/story/9437647/sex_pistols_rock_is_sick_and_living_in_london?source=thebeatles_rssfeed |archivedate = September 14, 2006|deadurl=yes}}</ref> Early female punk musicians displayed styles ranging from ]'s bondage gear to Patti Smith's "straight-from-the-gutter androgyny".<ref name="Strohm">Strohm (2004), p. 188.</ref> The former proved much more influential on female fan styles.<ref>See, e.g., Laing (1985), "Picture Section", p. 18.</ref> Over time, tattoos, ], and metal-studded and -spiked accessories became increasingly common elements of ] among both musicians and fans, a "style of adornment calculated to disturb and outrage".<ref>Wojcik (1997), p. 122.</ref> The typical male punk haircut was originally short and choppy; the ] later emerged as a characteristic style.<ref>Wojcik (1995), pp. 16–19; Laing (1985), p. 109.</ref> Those in hardcore scenes often adopt a ] look. | |||

| ] | |||

| The classic punk rock look among male American musicians harkens back to the T-shirt, motorcycle jacket, and jeans ensemble favored by American ] of the 1950s associated with the ] scene and by British ] of the 1960s. In addition to the T-shirt, and leather jackets they wore ripped jeans and boots, typically ]. The punk look was inspired to shock people. ]'s more androgynous, ragamuffin look—and reputed invention of the ]—was a major influence on Sex Pistols impresario ] and, in turn, British punk style.<ref name="RHV">{{cite web |author1=Isler, Scott |author2=Robbins, Ira |title=Richard Hell & the Voidoids |work=] |url=http://www.trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=richard_hell_and_the_voidoids |access-date=2007-10-23 |archive-date=October 22, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071022221054/http://trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=richard_hell_and_the_voidoids |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>Strongman (2008), pp. 58, 63, 64; Colegrave and Sullivan (2005), p. 78.</ref> (] of Cleveland's ] may have been the first rock musician to wear a safety-pin-covered jacket.)<ref>See {{cite web|author=Weldon, Michael|title=Electric Eels: Attendance Required|url=http://www.cleveland.com/music/index_story.ssf?/music/more/local/cle/2/index.html|publisher=Cleveland.com|access-date=December 19, 2010|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120123003715/http://www.cleveland.com/music/index_story.ssf?%2Fmusic%2Fmore%2Flocal%2Fcle%2F2%2Findex.html|archive-date=January 23, 2012}}</ref> McLaren's partner, fashion designer ], credits ] as the first British punk musician to rip his shirt, and Sex Pistols bassist ] as the first to use safety pins,<ref>{{cite magazine |author=Young, Charles M. |date=October 20, 1977| title=Rock Is Sick and Living in London |magazine=Rolling Stone |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/artists/thebeatles/articles/story/9437647/sex_pistols_rock_is_sick_and_living_in_london?source=thebeatles_rssfeed |access-date=October 10, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060914225550/http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/thebeatles/articles/story/9437647/sex_pistols_rock_is_sick_and_living_in_london?source=thebeatles_rssfeed |archive-date=September 14, 2006|url-status=dead}}</ref> although few of those following punk could afford to buy McLaren and Westwood's designs so famously worn by the Pistols, so they made their own, diversifying the 'look' with various different styles based on these designs. | |||

| Young women in punk demolished the typical female types in rock of either "coy sex kittens or wronged blues belters" in their fashion.<ref>Habell-Pallan, Michelle (2012). "Death to Racism and Punk Rock Revisionism", ''Pop: When the World Falls Apart: Music in the Shadow of Doubt''. p. 247-270. Durham : Duke University Press. {{ISBN|9780822350996}}.</ref> Early female punk musicians displayed styles ranging from ]'s bondage gear to ]'s "straight-from-the-gutter androgyny".<ref name="Strohm">Strohm (2004), p. 188.</ref> The former proved much more influential on female fan styles.<ref>See, e.g., Laing (1985), "Picture Section", p. 18.</ref> Over time, tattoos, ], and metal-studded and -spiked accessories became increasingly common elements of ] among both musicians and fans, a "style of adornment calculated to disturb and outrage".<ref>Wojcik (1997), p. 122.</ref> Among the other facets of the punk rock scene, a punk's hair is an important way of showing their freedom of expression.<ref name="Sklar">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1bfwAAAAQBAJ|title=Punk Style|last=Sklar|first=Monica|publisher=]|date=2013|access-date=December 23, 2021|pages=5–6, 26–27, 37–39|isbn=9781472557339}}</ref> The typical male punk haircut was originally short and choppy; the ] later emerged as a characteristic style.<ref>Wojcik (1995), pp. 16–19; Laing (1985), p. 109.</ref> Along with the mohawk, long spikes have been associated with the punk rock genre.<ref name="Sklar" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| The characteristic stage performance style of male punk musicians does not deviate significantly from the macho postures classically associated with rock music.<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 89, 97–98, 125.</ref> Female punk musicians broke more clearly from earlier styles. Scholar John Strohm suggests that they did so by creating personas of a type conventionally seen as masculine: "They adopted a tough, unladylike pose that borrowed more from the macho swagger of sixties garage bands than from the calculated bad-girl image of bands like ]."<ref name="Strohm"/> Scholar Dave Laing describes how bassist ] adopted fashion elements associated with male musicians only to generate a stage persona readily consumed as "sexy".<ref>Laing (1985), p. 92, 88.</ref> Laing focuses on more innovative and challenging performance styles, seen in the various erotically destabilizing approaches of Siouxsie Sioux, ]' ], and ]' ].<ref>Laing (1985), p. 89, 92–93.</ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| The lack of emphatic syncopation led ] to "deviant" forms. The characteristic style was originally the ].<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 34, 61, 63, 89–91.</ref> Sid Vicious, before he became the Sex Pistols' bassist, is credited with initiating the pogo in Britain as an attendee at one of their concerts.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 90; Robb (2006), pp. 159–160.</ref> ] is typical at hardcore shows. The lack of conventional dance rhythms was a central factor in limiting punk's mainstream commercial impact.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 34.</ref> | |||

| Between the late 16th and the 18th centuries, punk was a common, coarse synonym for prostitute; ] used it with that meaning in '']'' (1602) and '']'' (1603–4).<ref>Dickson (1982), p. 230.</ref> The term eventually came to describe "a young male hustler, a gangster, a hoodlum, or a ruffian".<ref>Leblanc (1999), p. 35.</ref> | |||

| The first known use of the phrase "punk rock" appeared in the '']'' on March 22, 1970, when ], co-founder of New York's anarcho-prankster band ] described his first solo album as "punk rock – redneck sentimentality".<ref name="flashbak1">{{cite web |first=J.P. |last=Robinson |url=https://flashbak.com/the-story-of-punk-421670/ |title=The Story Of 'Punk' |publisher=Flashbak |date=November 30, 2019 |access-date=2022-02-25}}</ref><ref>Shapiro (2006), p. 492.</ref> In 1969 Sanders recorded a song for an album called "Street Punk" but it was only released in 2008.<ref name="flashbak1" /> In the December 1970 issue of ], ], mocking more mainstream rock musicians, ironically referred to ] as "that Stooge punk".<ref>Bangs, Lester, "Of Pop and Pies and Fun" Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Creem, December 1970. Retrieved on November 29, 2007.</ref> ]'s ] credits this usage with inspiring his duo to bill its gigs as "punk music" or a "punk mass" for the next couple of years.<ref>Nobahkt (2004), p. 38.</ref> | |||

| Breaking down the distance between performer and audience is central to the punk ethic.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 82.</ref> Fan participation at concerts is thus important; during the movement's first heyday, it was often provoked in an adversarial manner—apparently perverse, but appropriately "punk". First-wave British punk bands such as the Pistols and ] insulted and otherwise goaded the audience into intense reactions. Laing has identified three primary forms of audience physical response to goading: can throwing, stage invasion, and spitting or "gobbing".<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 84–85.</ref> In the hardcore realm, stage invasion is often a prelude to ]. In addition to the numerous fans who have started or joined punk bands, audience members also become important participants via the scene's many amateur periodicals—in England, according to Laing, punk "was the first musical genre to spawn fanzines in any significant numbers".<ref>Laing (1985), p. 14.</ref> | |||

| In the March 1971 issue of Creem, critic ] wrote about the ]'s "hard-edge punk sound". In an April 1971 issue of '']'', he referred to a track by ] as "good, not too imaginative, punk rock and roll". The same month John Medelsohn described ]'s album '']'' as "nicely wrought mainstream punk raunch".<ref>{{cite web |first1=Mark |last1=Otto |first2=Jacob |last2=Thornton |others=Bootstrap contributors |url=https://www.alicecooperechive.com/articles/feature/rost/710415 |title=Rolling Stone: April 15, 1971 |publisher=Alice Cooper eChive |date=April 15, 1971 |access-date=2022-02-25}}</ref> ] used the term in the May 1971 issue of '']'', where he described ] as giving a "landmark exposition of punk rock".<ref>Shapiro (2006), p. 492. Taylor (2003) misidentifies the year of publication as 1970 (p. 16).</ref> Later in 1971, in his fanzine '']'', ] wrote about "what I have chosen to call "punkrock" bands—white teenage hard rock of '64–66 (], Kingsmen, ], etc.)".<ref>Gendron (2002), p. 348 n. 13.</ref>{{refn|group=nb|] writing for the Village Voice in October 1971 refers to "mid-60s punk" as a historical period of rock-and-roll.<ref name="Christgau (60s punk)">{{cite journal |last1=Christgau |first1=Robert |author1-link=Robert Christgau |title=Consumer Guide (20) |journal=The Village Voice |date=October 14, 1971 |url=http://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/cg/cg20.php |access-date=July 23, 2016 |archive-date=September 3, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160903214950/http://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/cg/cg20.php |url-status=live}}</ref>}} ] used the term "punk rock" in several articles written in the early 1970s to refer to mid-1960s garage acts.{{sfn|Bangs|2003|pp=8, 56, 57, 61, 64, 101}} | |||

| ==Pre-history== <!-- this section is a redirect from ] --> | |||

| In the liner notes of the 1972 anthology LP, '']'', musician and rock journalist ], later a member of the Patti Smith Group, used the term "punk rock" to describe the genre of 1960s garage bands and "garage-punk", to describe a song recorded in 1966 by the Shadows of Knight.<ref name="letitrock">Houghton, Mick, "White Punks on Coke", ''Let It Rock''. December 1975.</ref> ] referred to Iggy Pop as the "Punk Messiah of the Teenage Wasteland" in his review of ] July 1972 performance at ] in London for a British magazine called Cream (no relation to the more famous US publication).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.peterstanfield.com/blog/tag/Patrice+Kindl |title=Photographing Iggy and the Stooges at King Sound, Kings Cross, 1972 |website=peterstanfield.com |date=October 25, 2021 |access-date=December 9, 2021 }}</ref> In the January 1973 ''Rolling Stone'' review of ''Nuggets'', Greg Shaw commented "Punk rock is a fascinating genre... Punk rock at its best is the closest we came in the '60s to the original rockabilly spirit of Rock 'n Roll."<ref name="Shaw (Review of Nuggets)">{{cite magazine|last1=Shaw|first1=Greg|title=Punk Rock: the arrogant underbelly of Sixties pop (review of Nuggets)|magazine=Rolling Stone|page=68|date=January 4, 1973}}</ref> In February 1973, Terry Atkinson of the '']'', reviewing the debut album by a hard rock band, ], declared that it "achieves all that punk-rock bands strive for but most miss."<ref>Atkinson, Terry, "Hits and Misses", ''Los Angeles Times'', February 17, 1973, p. B6.</ref> A March 1973 review of an Iggy and the Stooges show in the '']'' dismissively referred to Pop as "the apotheosis of Detroit punk music".<ref>{{cite news |title=Detroit Press Ford review |date=March 30, 1973 |newspaper=Detroit Free Press |url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53086946/detroit-free-press-ford-review-30373/ |via=newspapers.com |access-date=December 9, 2021 }}</ref> In May 1973, Billy Altman launched the short-lived ''punk magazine'' in ] which was largely devoted to discussion of 1960s garage and psychedelic acts. | |||

| ===Garage rock and mod=== | |||

| <ref name="Laing (punk/Altman)">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZQZ_BwAAQBAJ&q=billy+altman+punk+magazine&pg=PA23|title=One Chord Wonders: Power and Meaning in Punk Rock|last1=Laing|first1=Dave|date=2015|publisher=PM Press|edition=Second|location=Oakland, CA|page=23|isbn=9781629630335|access-date=November 19, 2020|archive-date=May 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210507014413/https://books.google.com/books?id=ZQZ_BwAAQBAJ&q=billy+altman+punk+magazine&pg=PA23|url-status=live}} – Laing mentions original "punk" magazine. He indicates that much "punk" fanfare in the early 70s was in relation to mid-60s garage rock and artists perceived as following in that tradition.</ref><ref>Sauders, "Metal" Mike. "Blue Cheer More Pumice than Lava." ''punk magazine''. Fall 1973. In this ''punk magazine'' article Saunders discusses Randy Holden, former member of garage rock acts ] and ], then later protopunk/heavy rock band, Blue Cheer. He refers to an album by the Other Half as "acid punk."</ref> | |||

| {{Details3|] and ]}} | |||

| In the early and mid-1960s, garage rock bands that came to be recognized as punk rock's progenitors began springing up in many different locations around North America. ], a garage band from Portland, Oregon, had a breakout hit with their 1963 cover of "]", cited as "punk rock's defining ]".<ref>Sabin (1999), p. 157.</ref> The minimalist sound of many garage rock bands was influenced by the harder-edged wing of the ]. ]' hit singles of 1964, "]" and "]", have been described as "predecessors of the whole three-chord genre—the Ramones' 1978 'I Don't Want You,' for instance, was pure Kinks-by-proxy".<ref>Harrington (2002), p. 165.</ref> In 1965, ] quickly progressed from their debut single, "]", a virtual Kinks clone, to "]". Though it had little impact on the American charts, The Who's mod anthem presaged a more cerebral mix of musical ferocity and rebellious posture that characterized much early British punk rock: John Reed describes The Clash's emergence as a "tight ball of energy with both an image and rhetoric reminiscent of a young ]—speed obsession, pop-art clothing, art school ambition".<ref>Reed (2005), p. 49.</ref> The Who and fellow mods ] were among the few rock elders acknowledged by the Sex Pistols.<ref>Fletcher (2000), p. 497.</ref> By 1966, mod was already in decline. U.S. garage rock began to lose steam within a couple of years, but the aggressive musical approach and outsider attitude of "garage ]" bands like ] were picked up and emphasized by groups that were later seen as the crucial figures of protopunk. | |||

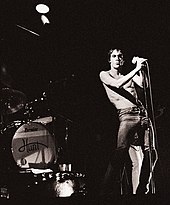

| ], the "godfather of punk"<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/iggy-pop-still-the-godfather-of-punk/|title=Iggy Pop: Still the 'godfather of punk'|date=January 8, 2017|work=CBS News|access-date=October 20, 2018|archive-date=February 25, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200225001946/https://www.cbsnews.com/news/iggy-pop-still-the-godfather-of-punk/|url-status=live}}</ref>]] | |||

| ===Protopunk=== | |||

| In May 1974, ''Los Angeles Times'' critic ] reviewed the second New York Dolls album, '']''. "I told ya the New York Dolls were the real thing," he wrote, describing the album as "perhaps the best example of raw, thumb-your-nose-at-the-world, punk rock since ]' '']''."<ref>Hilburn, Robert, "Touch of Stones in Dolls' Album", ''Los Angeles Times'', May 7, 1974, p. C12.</ref> In a 1974 interview for his fanzine ''Heavy Metal Digest'', ] told Iggy Pop "You went on record as saying you never were a punk" and Iggy replied "...well I ain't. I never was a punk."<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RwpJFOSyEmEC&pg=PT202|title=Gimme Danger: The Story of Iggy Pop|first=Joe|last=Ambrose|date=November 11, 2009|publisher=Omnibus Press|isbn=978-0-8571-2031-1|access-date=September 10, 2017|archive-date=August 19, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200819211657/https://books.google.com/books?id=RwpJFOSyEmEC&pg=PT202|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {{Details|Protopunk}} | |||

| In 1969, debut albums by two ]-based bands appeared that are commonly regarded as the central protopunk records. In January, Detroit's ] released '']''. "Musically the group is intentionally crude and aggressively raw", wrote critic ] in '']'': | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| Most of the songs are barely distinguishable from each other in their primitive two-chord structures. You've heard all this before from such notables as the Seeds, ], ], and the Kingsmen. The difference here ... is in the hype, the thick overlay of teenage-revolution and total-energy-thing which conceals these scrapyard vistas of clichés and ugly noise. ... "I Want You Right Now" sounds exactly (down to the lyrics) like a song called "I Want You" by ], a British group who came on with a similar sex-and-raw-sound image a couple of years ago (remember "]"?)<ref> review by Lester Bangs, '']'', April 5, 1969. Retrieved on January 16, 2007. {{Wayback|url=http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/mc5/albums/album/105316/review/5941601/kick_out_the_jams|date =20070205080821|bot=DASHBot}}</ref> | |||

| </blockquote>], the "godfather of punk"]] | |||

| That August, ], from ], premiered with a ]. According to critic ], the band, led by singer ], created "the sound of ]'s Airmobile—after thieves stripped it for parts".<ref>Marcus (1979), p. 294.</ref> The album was produced by ], a former member of New York's experimental rock group ]. Having earned a "reputation as the first underground rock band", The Velvet Underground inspired, directly or indirectly, many of those involved in the creation of punk rock.<ref>Taylor (2003), p. 49.</ref> | |||

| By 1975, ''punk'' was being used to describe acts as diverse as the ], the ], and ].<ref name="sav131">Savage (1991), p. 131.</ref> As the scene at New York's ] club attracted notice, a name was sought for the developing sound. Club owner ] called the movement ''"Street rock"''; ] credits '']'' magazine with using ''punk'' "to describe what was going on at CBGBs".<ref>Savage (1991), pp. 130–131.</ref> Holmstrom, ], and Ged Dunn's magazine '']'', which debuted at the end of 1975, was crucial in codifying the term.<ref>Taylor (2003), pp. 16–17.</ref> "It was pretty obvious that the word was getting very popular", Holmstrom later remarked. "We figured we'd take the name before anyone else claimed it. We wanted to get rid of the bullshit, strip it down to rock 'n' roll. We wanted the fun and liveliness back."<ref name="sav131" /> | |||

| In the early 1970s, the ] updated the original wildness of 1950s rock 'n' roll in a fashion that later became known as ].<ref>Harrington (2002), p. 538.</ref> The New York duo ] played spare, experimental music with a confrontational stage act inspired by that of The Stooges. At the Coventry club in the New York City borough of ], ] used rock as a vehicle for wise-ass attitude and humor.<ref>Bessman (1993), pp. 9–10.</ref> In Boston, ], led by Velvet Underground devotee ], gained attention with a minimalistic style. In 1974, an updated garage rock scene began to coalesce around the newly opened ] club in ]. Among the leading acts were the ], founded by former Modern Lover ]; ], whose frontman had been a member of the Velvet Underground for a few months in 1971; and Mickey Clean and the Mezz.<ref>Andersen and Jenkins (2001), p. 12. {{cite web | last =Vaughan| first = Robin| title = Reality Bites| work = Boston Phoenix| url = http://bostonphoenix.com/boston/music/cellars/documents/02927794.htm|date = June 6–12, 2003| accessdate =}} {{cite web | last =Harvard| first = Joe| title = Mickey Clean and the Mezz| work = Boston Rock Storybook | url = http://www.rockinboston.com/themezz.htm| accessdate =}} {{cite web | last =Robbins | first = Ira| title = Wille Alexander| work = Trouser Press Guide | url = http://trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=willie_alexander_and_the_boom_boom_band| accessdate = 2007-11-27}}</ref> In 1974, as well, the Detroit band ]—made up of three African-American brothers—recorded "scorching blasts of feral ur-punk", but couldn't arrange a release deal.<ref name=Rubin>{{cite news | author =Rubin, Mike | title = This Band Was Punk Before Punk Was Punk| work = New York Times | url = http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/15/arts/music/15rubi.html|date=2009-03-12| accessdate = 2009-03-15}}</ref> In Ohio, a small but influential underground rock scene emerged, led by ] in ] and ] and by Cleveland's ], Mirrors and ]. In 1975, Rocket from the Tombs split into ] and ]. The Electric Eels and Mirrors both broke up, and ] emerged from the fallout.<ref>Klimek, Jamie, , ''Jilmar Music''; Jäger, Rolf, , ''Rent a Dog''. Both retrieved on November 27, 2007.</ref> | |||

| ==1960s–1973: Precursors== <!-- this section is a redirect from ] --> | |||

| Britain's ], in the late 1960s, played in a range of psychedelic styles with a satiric, anarchic edge and a penchant for ]-style spectacle presaging the Sex Pistols by almost a decade.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thanatosoft.freeserve.co.uk/supermarketfiles/strangedays.htm|title=Interview with Mick Farren|publisher = ''Strange Days'' (Japan)|first=Toshikazu|last=Ohtaka|co-author=Akagawa, Yukiko |accessdate=2008-01-10|quote=Soundwise, we wanted to be incredibly loud and violent! That says it all. The hippies wanted to be nice and gentle, but our style was the opposite of that peaceful, natural attitude.|archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080508000420/http://www.thanatosoft.freeserve.co.uk/supermarketfiles/strangedays.htm |archivedate = May 8, 2008|deadurl=yes}}</ref> In 1970, the act evolved into the ], which carried on in a similar vein.<ref>Unterberger (1998), pp. 86–91.</ref> With his ] persona, ] made artifice and exaggeration central—elements, again, that were picked up by the Pistols and certain other punk acts.<ref>Laing (1985), pp. 24–26.</ref> The ] built on Bowie's presentation concepts, while moving musically in the direction that would become identified with punk. Bands in London's ] scene stripped the music back to its basics, playing hard, R&B-influenced rock 'n' roll. By 1974, the scene's top act, ], was paving the way for others such as ] and ] that would play a role in the punk explosion. Among the pub rock bands that formed that year was ], whose lead singer would soon adopt the name Joe Strummer.<ref>Robb (2006), p. 51.</ref> | |||

| ===Garage rock and beat=== | |||

| Bands anticipating the forthcoming movement were appearing as far afield as ], West Germany, where "punk before punk" band ] formed in 1971, building on the ] tradition of groups such as ].<ref name="trouser2">{{cite web | last =Neate| first = Wilson| title = NEU! | work = Trouser Press | url = http://www.trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=neu | accessdate = 2007-01-11}}</ref> In Japan, the anti-establishment Zunō Keisatsu (Brain Police) mixed garage psych and folk. The combo regularly faced censorship challenges, their live act at least once including onstage masturbation.<ref>Anderson (2002), p. 588.</ref> A new generation of Australian garage rock bands, inspired mainly by The Stooges and MC5, was coming even closer to the sound that would soon be called "punk": In ], ] also recalled the raw live sound of the British ], who had made a notorious tour of Australia and New Zealand in 1965.<ref>Unterberger (2000), p. 18.</ref> ], cofounded by Detroit expatriate ] in 1974, was playing gigs to a small but fanatical following in ]. | |||

| {{See also|garage rock|mod (subculture)|beat music}} | |||

| The early to mid-1960s garage rock bands in the United States and elsewhere are often recognized as punk rock's progenitors. ]'s "]" is often cited as punk rock's defining "]".{{sfn|Sabin|1999|p=157}}{{refn|group=nb|In the Kingsmen's version, the song's "El Loco Cha-Cha" riffs were pared down to a more simple and primitive rock arrangement providing a stylistic model for countless garage rock bands.<ref name="Pareles (Berry Obituary)">{{cite news |last1=Pareles |first1=Jon |title=Richard Berry, Songwriter of 'Louie Louie,' Dies at 61 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1997/01/25/arts/richard-berry-songwriter-of-louie-louie-dies-at-61.html |work=] |access-date=April 27, 2016 |date=January 25, 1997 |archive-date=March 26, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160326174905/http://www.nytimes.com/1997/01/25/arts/richard-berry-songwriter-of-louie-louie-dies-at-61.html |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Avant-Mier |first=Roberto |date=2008 |title=Rock the Nation: Latin/o Identities and the Latin Rock Diaspora |page=99 |publisher=] |location=London |isbn=978-1441164483}}</ref>}} After the success of the ], the garage phenomenon gathered momentum around the US.{{sfn|Lemlich|1992|pp=2–3}} By 1965, the harder-edged sound of British acts, such as ], ], and ], became increasingly influential with American garage bands.{{sfn|Sabin|1999|p=159}} The raw sound of U.S. groups such as ] and ] predicted the style of later acts.{{sfn|Sabin|1999|p=159}} In the early 1970s some rock critics used the term "punk rock" to refer to the mid-1960s garage genre,<ref name="laing 21" /> as well as for subsequent acts perceived to be in that stylistic tradition, such as the Stooges.{{sfn|Bangs|2003|p=101}} | |||

| In Britain, largely under the influence of the ] movement and beat groups, the Kinks' 1964 hit singles "]" and "]", were both influenced by "Louie, Louie".<ref>{{cite book |last=Kitts |first=Thomas M. |title=Ray Davies: Not Like Everybody Else |publisher=] |date=2007 |page=41}}</ref>{{refn|group=nb|The Ramones' 1978 'I Don't Want You,' was largely Kinks-influenced.<ref>Harrington (2002), p. 165.</ref>}} In 1965, ] released the mod anthem "]", which according to John Reed, anticipated the kind of "cerebral mix of musical ferocity and rebellious posture" that would characterize much of the later British punk rock of the 1970s.{{sfn|Reed|2005|p=49}}{{refn|group=nb|Reed describes the Clash's emergence as a "tight ball of energy with both an image and rhetoric reminiscent of a young ]—speed obsession, pop-art clothing, art school ambition."{{sfn|Reed|2005|p=49}} The Who and ] were among the few rock elders acknowledged by the Sex Pistols.<ref>Fletcher (2000), p. 497.</ref>}} The garage/beat phenomenon extended beyond North America and Britain.<ref name="Unterberger (Trans World)">{{cite web |last1=Unterberger |first1=Richie |title=Trans-World Punk Rave-Up, Vol. 1–2 |website=AllMusic |url=http://www.allmusic.com/album/trans-world-punk-rave-up-vol-1-2-mw0000938459 |access-date=June 22, 2017 |archive-date=March 14, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160314084101/http://www.allmusic.com/album/trans-world-punk-rave-up-vol-1-2-mw0000938459 |url-status=live}}</ref> In America, the ] movement birthed an array of garage bands that would later become influences on punk, ] described the ] as a band who can lay claim to influencing the movement, "the seeds of punk remain blatant in the howling ultimatum ] transferred from his previous teen combo to the Elevators"<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.austinchronicle.com/music/2019-08-02/the-origins-of-austin-punk-in-the-aftermath-of-the-13th-floor-elevators/|title=The Origins of Austin Punk in the Aftermath of the 13th Floor Elevators|website=www.austinchronicle.com}}</ref> as well as describing other bands in the ], Texas ] scene as "a prime example of the opaque ] undertow at the heart of the best ]". Hippie ] ] of ]'s ] was the first person to use the word "]" in a song title and also directly influenced ].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.loudersound.com/features/the-tale-of-david-peel-the-dope-smoking-hippy-who-became-the-king-of-punk | title=The strange tale of David Peel, the dope-smoking hippy who became the King of Punk | date=March 22, 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Etymology=== | |||

| From the late 16th through the 18th century, '']'' was a common, coarse synonym for ''prostitute''; William Shakespeare used it with that meaning in ''The Merry Wives of Windsor'' (1602) and ''Measure for Measure'' (1623).<ref>Dickson (1982), p. 230.</ref> The term eventually came to describe "a young male hustler, a gangster, a hoodlum, or a ruffian".<ref>Leblanc (1999), p. 35.</ref> As ] explains, "On TV, if you watched cop shows, '']'', '']'', when the cops finally catch the mass murderer, they'd say, 'you dirty Punk.' It was what your teachers would call you. It meant that you were the lowest."<ref>Quoted in Leblanc (1999), p. 35.</ref> The first known use of the phrase ''punk rock'' appeared in the '']'' on March 22, 1970, attributed to ], cofounder of New York's anarcho-prankster band ]. Sanders was quoted describing a solo album of his as "punk rock—redneck sentimentality".<ref>Shapiro (2006), p. 492.</ref> In the December 1970 issue of '']'', Lester Bangs, mocking more mainstream rock musicians, ironically referred to Iggy Pop as "that Stooge punk".<ref>Bangs, Lester, , ''Creem'', December 1970. Retrieved on November 29, 2007.</ref> Suicide's ] credits this usage with inspiring his duo to bill its gigs as a "punk mass" for the next couple of years.<ref>Nobahkt (2004), p. 38.</ref> | |||

| === Proto-punk === | |||

| ], performing in 1976]] | |||

| {{main|proto-punk}} | |||

| ] was the first music critic to employ the term ''punk rock'': In the May 1971 issue of ''Creem'', he described ], one of the most popular 1960s garage rock acts, as giving a "landmark exposition of punk rock".<ref>Shapiro (2006), p. 492. Note that Taylor (2003) misidentifies the year of publication as 1970 (p. 16).</ref> Later in 1971, in his fanzine '']'', ] wrote about "what I have chosen to call 'punk rock' bands—white teenage hard rock of '64-66 (], Kingsmen, ], etc.)".<ref>Gendron (2002), p. 348 n. 13.</ref> ] used the term "classic garage-punk," in reference to a song recorded in 1966 by The Shadows of Knight, in the liner notes of the anthology album '']'', released in 1972.<ref name="letitrock">Houghton, Mick, "White Punks on Coke", ''Let It Rock''. December 1975.</ref> In June 1972, the fanzine ''Flash'' included a "Punk Top Ten" of 1960s albums.<ref>Taylor (2003), p. 16.</ref> In February 1973, Terry Atkinson of the '']'', reviewing the debut album by a hard rock band, ], declared that it "achieves all that punk-rock bands strive for but most miss."<ref>Atkinson, Terry, "Hits and Misses", ''Los Angeles Times'', February 17, 1973, p. B6.</ref> Three months later, Billy Altman launched the short-lived ''punk magazine''.<ref>Laing (1985), p. 13; , ''Punk Magazine'', July 20, 2001. Retrieved on March 4, 2008.</ref> | |||

| In August 1969, ], from ], premiered with a ]. According to critic ], the band, led by singer ], created "the sound of ]'s ]—after thieves stripped it for parts".<ref>Marcus (1979), p. 294.</ref> The album was produced by ], a former member of New York's experimental rock group ], who inspired many of those involved in the creation of punk rock.<ref>Taylor (2003), p. 49.</ref> The ] updated 1950s' rock 'n' roll in a fashion that later became known as ].<ref>Harrington (2002), p. 538.</ref> The New York duo ] played spare, experimental music with a confrontational stage act inspired by that of the Stooges.<ref>Bessman (1993), pp. 9–10.</ref> In Boston, ], led by ], gained attention for their minimalistic style. In 1974, as well, the Detroit band ]—made up of three African-American brothers—recorded "scorching blasts of feral ur-punk", but could not arrange a release deal.<ref name="Rubin">{{cite news |last=Rubin |first=Mike |title=This Band Was Punk Before Punk Was Punk |work=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/15/arts/music/15rubi.html |date=March 12, 2009 |access-date=2009-03-15 |archive-date=July 1, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170701073322/http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/15/arts/music/15rubi.html |url-status=live}}</ref> In Ohio, a small but influential underground rock scene emerged, led by ] in ]<ref name="WaPo">{{cite news|last1=Sommer|first1=Tim|title=How the Kent State massacre helped give birth to punk rock|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/how-the-kent-state-massacre-changed-music/2018/05/03/b45ca462-4cb6-11e8-b725-92c89fe3ca4c_story.html|newspaper=The Washington Post|access-date=2018-05-03|date=May 8, 2018|archive-date=May 8, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180508211408/https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/how-the-kent-state-massacre-changed-music/2018/05/03/b45ca462-4cb6-11e8-b725-92c89fe3ca4c_story.html|url-status=live}}</ref> and ] and by Cleveland's ], ] and ]. | |||

| In May 1974, ''Los Angeles Times'' critic Robert Hilburn reviewed the second New York Dolls album, ]. "I told ya the New York Dolls were the real thing", he wrote, describing the album as "perhaps the best example of raw, thumb-your-nose-at-the-world, punk rock since ]' '']''.'"<ref>Hilburn, Robert, "Touch of Stones in Dolls' Album", ''Los Angeles Times'', May 7, 1974, p. C12.</ref> Bassist Jeff Jensen of Boston's Real Kids reports of a show that year, "A reviewer for one of the free entertainment magazines of the time caught the act and gave us a great review, calling us a 'punk band.' ... e all sort of looked at each other and said, 'What's punk?'"<ref>Harvard, Joe, , ''Boston Rock Storybook''. Retrieved on November 27, 2007. {{Wayback|url=http://www.rockinboston.com/realkids.htm|date =20071226183408|bot=DASHBot}}</ref> | |||

| Bands anticipating the forthcoming movement were appearing as far afield as ], West Germany, where "punk before punk" band ] formed in 1971, building on the ] tradition of groups such as ].<ref name="trouser2">{{cite magazine |last=Neate |first=Wilson |title=NEU! |magazine=Trouser Press |url=http://www.trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=neu |access-date=2007-01-11 |archive-date=November 12, 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061112175958/http://www.trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=neu |url-status=live}}</ref> In Japan, the anti-establishment Zunō Keisatsu (Brain Police) mixed ] and ]. The combo regularly faced censorship challenges, their live act at least once including onstage masturbation.<ref>Anderson (2002), p. 588.</ref> In Peru, founded in 1964, the group ], used fast tempos, aggressive riffing, hoarses and screamed vocals along with souped-up tracks about prison escapes, funerals and destruction has led some publication to retrospectively credit them as pioneering punk rock.<ref>{{cite news |last=Watts |first=Jonathan |title=Where did punk begin? A cinema in Peru |work=] |url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/sep/14/where-punk-begin-cinema-peru |date=September 14, 2012 |access-date=2024-12-24 |archive-date=May 24, 2024 |archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20240524130713/https://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/sep/14/where-punk-begin-cinema-peru |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=García |first=Julio |title=Ni Sex Pistols ni Ramones; el punk empezó en Perú y en español |work=] |url=https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2011/12/111223_saicos_precursores_punk_peruano_jgc |date=December 24, 2011 |access-date=2024-12-24 |archive-date=December 26, 2023 |archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20231226085034/https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2011/12/111223_saicos_precursores_punk_peruano_jgc |url-status=live}}</ref> A new generation of Australian garage rock bands, inspired mainly by the Stooges and ], was coming closer to the sound that would soon be called "punk": In ], ] evoked the live sound of the British ], who had toured Australia and New Zealand in 1975.<ref>Unterberger (2000), p. 18.</ref> | |||

| By 1975, ''punk'' was being used to describe acts as diverse as the ], the ], and ].<ref name="sav131">Savage (1991), p. 131.</ref> As the scene at New York's ] club attracted notice, a name was sought for the developing sound. Club owner ] called the movement "street rock"; John Holmstrom credits '']'' magazine with using ''punk'' "to describe what was going on at CBGBs".<ref>Savage (1991), pp. 130–131.</ref> Holmstrom, McNeil, and Ged Dunn's magazine '']'', which debuted at the end of 1975, was crucial in codifying the term.<ref>Taylor (2003), pp. 16–17.</ref> "It was pretty obvious that the word was getting very popular", Holmstrom later remarked. "We figured we'd take the name before anyone else claimed it. We wanted to get rid of the bullshit, strip it down to rock 'n' roll. We wanted the fun and liveliness back."<ref name="sav131"/> | |||

| ==1974–1976: First wave== | |||

| ==Early history== | |||

| ===North America=== | ===North America=== | ||

| ====New York City==== | ====New York City==== | ||

| ], New York]] | |||

| {{Listen | |||

| The origins of New York's punk rock scene can be traced back to such sources as the late 1960s ] and an early 1970s ] movement centered on the ] in ], where the ] performed.{{sfn|Savage|1991|pp=86–90, 59–60}} In early 1974, a new scene began to develop around the ] club, also in ]. At its core was ], described by critic John Walker as "the ultimate garage band with pretensions".<ref name="W">Walker (1991), p. 662.</ref> Their influences ranged from ] to the staccato guitar work of ]'s ].<ref>Strongman (2008), pp. 53, 54, 56.</ref> The band's bassist/singer, ], created a look with cropped, ragged hair, ripped T-shirts, and black leather jackets credited as the basis for punk rock visual style.<ref name="S89">Savage (1992), p. 89.</ref> In April 1974, ] came to CBGB for the first time to see the band perform.<ref>Bockris and Bayley (1999), p. 102.</ref> A veteran of independent theater and performance poetry, Smith was developing an intellectual, feminist take on rock 'n' roll. On June 5, she recorded the single "]"/"]", featuring Television guitarist ]; released on her own Mer Records label, it heralded the scene's DIY ethic and has often been cited as the first punk rock record.<ref>{{cite web|title=Patti Smith—Biography|publisher=Arista Records|url=http://www.arista.com/psmith/smithbio.html|access-date=2007-10-23|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071103053048/http://www.arista.com/psmith/smithbio.html |archive-date=November 3, 2007|url-status=dead}} Strongman (2008), p. 57; Savage (1991), p. 91; Pareles and Romanowski (1983), p. 511; Bockris and Bayley (1999), p. 106.</ref> By August, Smith and Television were gigging together at ].<ref name="S89" /> | |||

| |filename=Television-Blank Gen (Live).ogg | |||

| ] performing in ] in 1976. The Ramones are often described as the first true punk band, popularizing the punk movement in the United States. They are regarded as highly influential in today's ].]] | |||

| |title="Blank Generation" | |||

| In ], the ] drew on sources ranging from the Stooges to ] and ] to ] and 1960s girl groups, and condensed rock 'n' roll to its primal level: {{" '}}1–2–3–4!' bass-player ] shouted at the start of every song as if the group could barely master the rudiments of rhythm."{{sfn|Savage|1991|pp=90–91}} The band played its first show at CBGB in August 1974.<ref>Gimarc (2005), p. 14</ref> By the end of the year, the Ramones had performed seventy-four shows, each about seventeen minutes long.<ref>Bessman (1993), p. 27.</ref> "When I first saw the Ramones", critic ] later remembered, "I couldn't believe people were doing this. The dumb brattiness."{{sfn|Savage|1991|pp=132–33}}{{Listen | |||

| |description=The original anthem of the punk scene, performed live by ] in 1974 or 1975, with ] on lead vocals. The verse, described by ] as defying melody, yields to the chorus, "set to a descending pattern reminiscent of ]'s "]".<ref>Valentine (2006), p. 54.</ref> ]'s virtuosic guitar style would lead the band away from what became the typical punk approach.<ref>Valentine (2006), pp. 52–55.</ref>}} | |||

| | filename = | |||

| The origins of New York's punk rock scene can be traced back to such sources as late 1960s ] and an early 1970s ] movement centered on the ] in ], where the ] performed.<ref>Savage (1991), pp. 86–90, 59–60.</ref> In early 1974, a new scene began to develop around the ] club, also in ]. At its core was ], described by critic John Walker as "the ultimate garage band with pretensions".<ref name="W">Walker (1991), p. 662.</ref> Their influences ranged from the Velvet Underground to the staccato guitar work of ]'s ].<ref>Strongman (2008), pp. 53, 54, 56.</ref> The band's bassist/singer, ], created a look with cropped, ragged hair, ripped T-shirts, and black leather jackets credited as the basis for punk rock visual style.<ref name="S89">Savage (1992), p. 89.</ref> In April 1974, ], a member of the Mercer Arts Center crowd and a friend of Hell's, came to CBGB for the first time to see the band perform.<ref>Bockris and Bayley (1999), p. 102.</ref> A veteran of independent theater and performance poetry, Smith was developing an intellectual, feminist take on rock 'n' roll. On June 5, she recorded the single "]"/"]", featuring Television guitarist ]; released on her own Mer Records label, it heralded the scene's ] (DIY) ethic and has often been cited as the first punk rock record.<ref>{{cite web|title=Patti Smith—Biography|publisher=Arista Records|url=http://www.arista.com/psmith/smithbio.html|accessdate=2007-10-23|archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20071103053048/http://www.arista.com/psmith/smithbio.html |archivedate = November 3, 2007|deadurl=yes}} Strongman (2008), p. 57; Savage (1991), p. 91; Pareles and Romanowski (1983), p. 511; Bockris and Bayley (1999), p. 106.</ref> By August, Smith and Television were gigging together at another downtown New York club, ].<ref name="S89"/> | |||

| | title = "I Wanna Be Sedated" | |||

| | description = The 1978 single "]" was described by the author Brian J. Bow as one of the Ramones' "most classic" pieces of music. After a show in London, singer ] told manager ]: "Put me in a wheelchair and get me on a plane before I go insane."<ref>Bowe 2010, p. 52.</ref> This quote would be the chorus to "I Wanna Be Sedated", whose lyrics invoke the stress which the band was under during touring. It is the most downloaded song from the catalog by the Ramones.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Schinder|first1=Scott|last2=Schwartz|first2=Andy|title=Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever|year=2007|publisher=]|volume=2|isbn=978-0-313-33847-2|page=550}}</ref> | |||

| | format = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| That spring, Smith and Television shared a two-month-long weekend residency at CBGB that significantly raised the club's profile.<ref>Bockris and Bayley (1999), p. 119.</ref> The Television sets included Richard Hell's "Blank Generation", which became the scene's emblematic anthem.<ref>Savage (1992) claims that "Blank Generation" was written around this time (p. 90). However, the Richard Hell anthology album ''Spurts'' includes a live Television recording of the song that he dates "spring 1974."</ref> Soon after, Hell left Television and founded a band featuring a more stripped-down sound, ], with former New York Dolls ] and ].<ref name="RHV" /> In August, Television recorded a single, "Little Johnny Jewel". In the words of John Walker, the record was "a turning point for the whole New York scene" if not quite for the punk rock sound itself – Hell's departure had left the band "significantly reduced in fringe aggression".<ref name="W" /> | |||

| ], New York]] | |||

| Out in ], several miles from lower Manhattan, the members of a newly formed band adopted a common surname. Drawing on sources ranging from the Stooges to ] and ] to ] and 1960s ]s, the ] condensed rock 'n' roll to its primal level: "'1-2-3-4!' bass-player ] shouted at the start of every song, as if the group could barely master the rudiments of rhythm."<ref>Savage (1991), pp. 90–91.</ref> The band played its first gig at CBGB on August 16, 1974. Another new act, ], also debuted at the club that month. By the end of the year, the Ramones had performed seventy-four shows, each about seventeen minutes long.<ref>Bessman (1993), p. 27.</ref> "When I first saw the Ramones", critic Mary Harron later remembered, "I couldn't believe people were doing this. The dumb brattiness."<ref>Savage (1991), pp. 132–133.</ref> The Dictators, with a similar "playing dumb" concept, were recording their debut album. '']'' came out in March 1975, mixing absurdist originals such as "Master Race Rock" and loud, straight-faced covers of cheese pop like ]'s "]".<ref>{{cite web|author=Deming, Mark|title="''The Dictators Go Girl Crazy!''" (review)|publisher=Allmusic|url={{Allmusic|class=album|id=r61283|pure_url=yes}}|accessdate=2007-12-27}}</ref> | |||

| Early in 1976, Hell left the Heartbreakers to form ], described as "one of the most harshly uncompromising bands".<ref>Pareles and Romanowski (1983), p. 249.</ref> That April, the Ramones' debut album was released by ]; the first single was "]", opening with the rallying cry "Hey! Ho! Let's go!" According to a later description, "Like all cultural watersheds, '']'' was embraced by a discerning few and slagged off as a bad joke by the uncomprehending majority."<ref name="trouser3">{{cite web|title=Ramones|author1=Isler, Scott|author2=Robbins, Ira|work=Trouser Press|url=http://trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=ramones|access-date=2007-10-23|archive-date=November 2, 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071102185040/http://www.trouserpress.com/entry.php?a=ramones|url-status=live}}</ref> ], whose core members were from ] and ], had debuted at CBGB in November 1976, opening for the Dead Boys. They were soon playing regularly at Max's Kansas City and CBGB.<ref>Porter (2007), pp. 48–49; Nobahkt (2004), pp. 77–78.</ref> | |||

| That spring, Smith and Television shared a two-month-long weekend residency at CBGB that significantly raised the club's profile.<ref>Bockris and Bayley (1999), p. 119.</ref> The Television sets included Richard Hell's "Blank Generation", which became the scene's emblematic anthem.<ref>Savage (1992) claims that "Blank Generation" was written around this time (p. 90). However, the Richard Hell anthology album ''Spurts'' includes a live Television recording of the song that he dates "spring 1974."</ref> Soon after, Hell left Television and founded a band featuring a more stripped-down sound, ], with former New York Dolls ] and ]. The pairing of Hell and Thunders, in one critical assessment, "inject a poetic intelligence into mindless self-destruction".<ref name="RHV"/> A July festival at CBGB featuring over thirty new groups brought the scene its first substantial media coverage.<ref>Strongman (2008), p. 96; Savage (1992), p. 130.</ref> In August, Television—with Fred Smith, former Blondie bassist, replacing Hell—recorded a single, "Little Johnny Jewel", for the tiny Ork label. In the words of John Walker, the record was "a turning point for the whole New York scene" if not quite for the punk rock sound itself—Hell's departure had left the band "significantly reduced in fringe aggression".<ref name="W"/> | |||