| Revision as of 05:51, 7 May 2011 editPfistermeister (talk | contribs)3,068 edits Undid revision 427801841 by 198.151.130.14 (talk)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:03, 12 January 2025 edit undo134.65.164.210 (talk) →Psychic apparatus | ||

| (938 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Psychological concepts by Sigmund Freud}} | |||

| {{Dablink|For other uses of ego and id, see ] and ].}} | |||

| {{Cleanup|reason=grammar, encyclopedic diction, as per WP:MOS|date=January 2025}} | |||

| {{Dablink|"Superego" redirects here. For the Superego Podcast, see ].}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=January 2024}} | |||

| {{redirect|Structural model|structural models in economics|Economic model|structural models in statistics|Structural equation modeling|and|Reduced form}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Ego (disambiguation)|ID (disambiguation)|Superego (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Citations missing|date=September 2008}} | |||

| {{Psychoanalysis |Concepts}} | |||

| {{psychoanalysis}} | |||

| The '''id, ego and superego''' are the three different, functionally interlocking main components of the human soul, as investigated and ] by ]'''.''' They represent the '''structural ]''' of ]. Freud himself used the ] terms ''das Es'', ''Ich'', and ''Über-Ich''. The ] terms id, ego and superego were chosen by his original translators and have remained in use. The terms soul and psyche here are ] in the sense of the human organism as a whole, focussing on the mental aspect without any option of concrete separability from matter and therefore in strict distinction to the religious concept of "soul". | |||

| '''Id''', '''ego''' and '''super-ego''' are the three parts of the ] defined in ] ] of the psyche; they are the three theoretical constructs in terms of whose activity and interaction mental life is described. According to this model of the psyche, the '''id''' is the set of uncoordinated instinctual trends; the '''ego''' is the organized, realistic part; and the '''super-ego''' plays the critical and moralising role.<ref name="Snowden">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Snowden | |||

| | first = Ruth | |||

| | authorlink = Ruth Snowden | |||

| | title = Teach Yourself Freud | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | pages = 105–107 | |||

| | isbn = 9780071472746 }}</ref> | |||

| The structural model of the soul was introduced in Freuds essay '']'' (1920). It describes the innate needs of the id located in the unconscious as a primary process, which the conscious mind - the secondary process - evaluates with participation of its socialisation and strives to satisfy via appropriate objects of external reality. This model - further refined and formalised in subsequent essays as ] - represents a response to the ambiguous/contradictory use of the terms conscious and unconscious in the topological model, the first one.<ref>''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'', Third Edition (1999) Allan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, Eds. pp. 256–257.</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Freud |first=Sigmund |url=https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_Beyond_P_P.pdf |title=The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVIII |date=1955 |publisher=The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis |year=1955 |location=London |pages=51 |translator-last=Strachey, Strachey, and Tyson}}</ref> | |||

| Even though the model is "structural" and makes reference to an "apparatus", the id, ego and super-ego are functions of the ] rather than parts of the brain and do not correspond one-to-one with actual somatic structures of the kind dealt with by ]. | |||

| According to Freud as well as ] the '''id''' is a set of uncoordinated ]ual needs; the '''superego''' plays the judgemental role via internalized experiences; and the '''ego''' is the perceiving, logically organizing agent that mediates between the id's innate ], the demands of external reality and those of the critical superego;<ref>Freud, Sigmund. ''The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud.'' Vol. XIX (1999) James Strachey, Gen. Ed. {{ISBN|0-09-929622-5}}</ref> Freud compared the ego - in its relation to the id - to a man on horseback: the rider must restrain and direct the superior energy of his animal and at times allow for a satisfaction of its urges if he wants to keep it alive and the species healthy. The ego is thus "in the habit of transforming the id's will into action, as if it were its own."<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Volume XIX (1923–26) ''The Ego and the Id and Other Works'' |last=Freud|first=Sigmund|publisher=Hogarth Press|others=Strachey, James., Freud, Anna, 1895–1982, Rothgeb, Carrie Lee, Richards, Angela., Scientific Literature Corporation.|year=1978|isbn=0701200677|location=London|pages=19|oclc=965512}}</ref> | |||

| The concepts themselves arose at a late stage in the development of Freud's thought: the 'structural model' (which succeeded his 'economic model' and 'topographical model') was first discussed in his 1920 essay "]" and was formalised and elaborated upon three years later in his "]". Freud's proposal was influenced by the ambiguity of the term "]" and its many conflicting uses. | |||

| ==Psychic apparatus == | |||

| ==Id== | |||

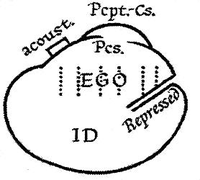

| ]). In general, this instance contains the socialization that takes place during childhood; this gives it its function as our ''conscience''. The borders between un- and consciousness aren't sharp: "Where id was, ego shall become."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Neue Folge der Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse |date=1933 |page=31. Vorlesung: Die Zerlegung der psychischen Persönlichkeit}}</ref>]]In order to overcome difficulties of understanding as far as possible, Freud formulated his "metapsychology" which for Lacan represents a ''technical elaboration''<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lacan |first1=Jaques |title=Freuds technische Schriften |date=1953 |publisher=Seminar of Jacques Lacan}}</ref> of the concepts of the soul model: dividing the organism into three instances the id is regarded as the germ from which the ego and the superego develop. Driven by an energy that Freud calls ''libido'' in direct reference to Plato's ],<ref>{{cite book |last1=Platon |title=Symposion}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse |pages=99}}</ref> the instances complement each other through their specific functions in a similar way to the ] of a cell or parts of a technical apparatus.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Gesammelte Werke. Bd. 14. Selbstdarstellung |pages=85}}</ref> | |||

| Further distinctions (as the coordinates of ''topology'', ''dynamics'' and ''economy'') encouraged Freud to assume that the metapsychological elaboration of the structural model would make it fully compatible with biological sciences such as evolutionary theory and enable a well-founded concept of mental health including a theory of human development, which naturally completed in three successive stages: the oral, anal and genital phase. However, as important as this is for the diagnostic process (illness can only be realised as a deviation from the optimal cooperation of all psycho-organic functions), Freud had to be modest and leave structural model in the unfinished state of a '']''<ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Gesammelte Werke. Bd. 14. Selbstdarstellung |pages=85}}</ref> because - as he stated one last time in ] - there was no well-founded primate research at the time.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Sigmund Freud: Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion |pages=180 (Kapitel 3, Abschnitt C)}}</ref> Without knowledge of the instinctive social behaviour with the corresponding structure of cohabitation of our genetically ] in realm of primates, Freud's thesis of Darwin's primordial horde (as presented for discussion in ]) can't be tested and, if possible, replaced by a realistic model. Horde life and its violent abolition through introduction of mononogamy (as an agreement between the sons who murdered the horde's polygamous father) embody the evolutionary as well as cultural-prehistorical core of psychoanalysis. It stands in contrast to the religiously enigmatic reports about the origin of ] on earth as an expression of divine will, but closer to the ancient trap to pacify political conflicts among the groups of Neolithic mankind. (See ]' uprising against Zeus, who created ] as a fatal wedding gift for Epimetheus to divide and rule the titanic brothers; Plato's myth of spherical men cut into isolated individuals for the same reason;<ref>{{cite book |last1=Plato |title=Symposion |chapter=Aristophanes' speech}}</ref> and the similarly resolved revolt of inferior gods in the Flood epic ]). Additional important assumptions are based on it, such as the ], the origin of moral-totemic rules like ] and, not least, Freud's '']''. Nonetheless, due to the lack of ethological primate research, these ideas remained an unproven belief of palaeo-anthropological science – only a ] or "''just so story'' as a not unpleasant English critic wittily called it. But I mean it honours a hypothesis if it shows capable of creating context and understanding in new areas."<ref name="Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse">{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse |publisher=textlog.de |pages=X - Die Masse und die Urhorde |url=https://www.textlog.de/freud/abhandlungen/massenpsychologie/x-die-masse-und-die-urhorde#fnref-1}}</ref> | |||

| === Id === | |||

| The id comprises the disorganised part of the personality structure that contains the | |||

| Freud conceived the id as the unconscious source of all innate needs, emotional impulses and ], including the sexual drive.<ref name="Carlson">Carlson, N. R. (1999–2000) "Personality", ''Psychology: The Science of Behavior'' (Canadian ed.), p. 453. Scarborough, Ontario: Allyn and Bacon Canada.</ref> The id acts driven by aggression (energy), it's "the dark, inaccessible part of our personality". It seems limited to analysis of dreams and neurotic symptoms, and can only be described in terms of its contrast with the ego. It has no organisation and no collective will: It only demands immediate gratification of its instincts according to the ].<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933), ''New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis''. pp. 105–6.</ref> It is oblivious to reason and the presumptions of ordinary conscious life: "contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other. . . There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation. . . nothing which corresponds to the idea of time."<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933). p. 106.</ref> The id "knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality. ...Instinctual ] seeking discharge—that, in our view, is all there is in the id."<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933). p. 107.</ref> | |||

| basic drives. The id acts according to the "]", seeking to avoid pain or displeasure aroused by increases in instinctual tension.<ref name="Rycroft">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Rycroft | |||

| | first = Charles | |||

| | authorlink = Charles Rycroft | |||

| | title = A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year = 1968 }}</ref> | |||

| Developmentally, the id precedes the ego. The id consists of the basic instinctual drives that are present at birth, inherent in the somatic organization, and governed only by the pleasure principle.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last1=Lapsley |first1=Daniel K. |last2=Paul C. |first2=Stey |title=Encyclopedia of Human Behavior |chapter=Id, Ego, and Superego |year=2012 |pages=393–399 |chapter-url=https://www3.nd.edu/~dlapsle1/Lab/Articles_%26_Chapters_files/Entry%2520for%2520Encyclopedia%2520of%2520Human%2520BehaviorFInal%2520Submitted%2520Formatted4.pdf |doi=10.1016/B978-0-12-375000-6.00199-3 |isbn=9780080961804 |access-date=2018-10-22 |archive-date=2016-12-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161213073830/http://www3.nd.edu/~dlapsle1/Lab/Articles_%26_Chapters_files/Entry%20for%20Encyclopedia%20of%20Human%20BehaviorFInal%20Submitted%20Formatted4.pdf |url-status=dead }}Chapter of {{cite book |editor-last=Ramachandran |editor-first=Vilayanur S. |editor-link=V. S. Ramachandran |title=Encyclopedia of Human Behavior |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yASuxMCuhKkC |edition=2nd, revised |year=2012 |publisher=Academic Press |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |pages= |isbn=978-0-080-96180-4 }}</ref><ref>Freud, ''An Outline of Psycho-analysis'' (1940)</ref> The psychic apparatus begins as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured "ego", a concept of self that takes the ] into account. | |||

| The id is unconscious by definition: | |||

| Freud understands the id as "the great reservoir of ]",<ref>Sigmund Freud, ''The Ego and the Id'', ''On Metapsychology'' (Penguin Freud Library 11) p. 369.</ref> the energy of desire as expressed, for example, in the behaviours of sexuality, the incorporation of food or the baby-care (maternal love). In general, the nature of libido is that of Platonic '''Eros''', a universal desire that is inherent in all life instincts. They constantly strive to compensate for the processes of biological decay, rejuvenating the species of living beings by means of their ] and ]. | |||

| {{quote|'It is the dark, inaccessible part of our personality, what little we know of it we have learned from our study of the ] and of the construction of neurotic symptoms, and most of that is of a negative character and can be described only as a contrast to the ego. We approach the id with analogies: we call it a chaos, a cauldron full of seething excitations... It is filled with energy reaching it from the instincts, but it has no organisation, produces no collective will, but only a striving to bring about the satisfaction of the instinctual needs subject to the observance of the pleasure principle'.<ref>Sigmund Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis'' (Penguin Freud Library 2) p. 105-6</ref>}} In the id, | |||

| Complementing this constructive aspect of the libido, the author later postulated an inherent ], the '''Thanatos''' that has a decomposing effect and seeks "to lead organic life back into the inanimate state.<ref>Freud, ''On Metapsychology'' p. 380.</ref> For Freud, "the death instinct would thus seem to express itself—though probably only in part—as an ''instinct of destruction'' directed against the external world and other organisms"<ref>Freud, ''On Metapsychology'' p. 381.</ref> through aggression. Since libido energy encompasses all instinctive impulses, ] and Thanatos are regarded as fundamental forces of the id,<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933). p. 138.</ref> which co-operate despite their apparent incompatibility: The organism has the urge to 'synthetically' regenerate by integration of suitable molecules or energy into itself, for this purpose it must first deconstruct the ingested food complexes: the ‘analytical’ effect of stomach acid. | |||

| {{quote|'contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other out....There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation...nothing in the id which corresponds to the idea of time'.<ref>Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 106</ref>}} | |||

| === Ego === | |||

| Developmentally, the id is anterior to the ego; i.e. the psychic apparatus begins, at birth, as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured ego. Thus, the id: | |||

| The ego acts according to the ]. It analyses complex perceptions (things, ideas, dreams), synthesises the appropriate parts into logically coherent interpretations (also ]) and rules the muscular apparatus. Since the id's drives are frequently incompatible with the moral prescriptions and religious illusions of contemporary cultures,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Das Unbehagen in der Kultur}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Die Zukunft einer Illusion}}</ref> the ego attempts to direct the libidinal energy and satisfy its demands in accordance with the imperatives of that reality.<ref name="Child Development">{{cite journal |last1=Noam |first1=Gil G |last2=Hauser |first2=Stuart taque chinaz #14 T. |last3=Santostefano |first3=Sebastiano |last4=Garrison |first4=William |last5=Jacobson |first5=Alan M. |last6=Powers |first6=Sally I. |last7=Mead |first7=Merrill |date=February 1984 |title=Ego Development and Psychopathology: A Study of Hospitalized Adolescents |journal=Child Development |publisher=] on behalf of the ] |volume=55 |issue=1 |pages=189–194 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00283.x |pmid=6705621}}</ref> According to Freud the ego, in its role as mediator between the id and reality, is often "obliged to cloak the (unconscious) commands of the id with its own ] ], to conceal the id's conflicts with reality, to profess...to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding."<ref name="Freud, p. 110">Sigmund Freud (1933). p. 110</ref> | |||

| Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean the sense of self, but later expanded it to include psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, ], control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory. The ego is the organizing principle upon which thoughts and interpretations of the world are based.<ref name="Snowden">{{cite book|title=Teach Yourself Freud|last=Snowden|first=Ruth|publisher=]|year=2006|isbn=978-0-07-147274-6|pages=105–107}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|". . contains everything that is inherited, that is present at birth, is laid down in the constitution -- above all, therefore, the instincts, which originate from the somatic organisation, and which find a first psychical expression here (in the id) in forms unknown to us." <ref>Freud, ''An Outline of Psycho-analysis'' (1940)]</ref>}} | |||

| According to Freud, "the ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. ...The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions... it is like a tug of war... with the difference that in the tug of war the teams fight against one another in equality, while the ego is against the much stronger 'id'."<ref>Freud,''The Ego and the Id'', ''On Metapsychology'' pp. 363–4.</ref> In fact, the ego is required to serve "three severe masters...the external world, the superego and the id."<ref name="Freud, p. 110"/> It seeks to find a balance between the natural drives of the id, the limitations imposed by reality, and the strictures of the superego. It is concerned with self-preservation: it strives to keep the id's instinctive needs within limits, adapted to reality and submissive to the superego. | |||

| The mind of a newborn child is regarded as completely "id-ridden", in the sense that it is a mass of instinctive drives and impulses, and needs immediate satisfaction, a view which equates a newborn child with an id-ridden individual—often humorously—with this analogy: an ] tract with no sense of responsibility at either end{{Citation needed|date=November 2010}}. | |||

| Thus "driven by the id, confined by the superego, repulsed by reality" the ego struggles to bring about harmony among the competing forces. Consequently, it can easily be subject to "realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the superego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id."<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933). pp. 110–11.</ref> The ego may wish to serve the id, trying to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts, while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the superego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of ], ], and inferiority. | |||

| The id is responsible for our basic drives, 'knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality...Instinctual cathexes seeking discharge - that, in our view, is all there is in the id'.<ref>Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 107</ref> It is regarded as 'the great reservoir of ]',<ref>Sigmund Freud, "The Ego and the Id", ''On Metapsychology'' (Penguin Freud Library 11)p. 369n</ref> the instinctive drive to create - the life instincts that are crucial to pleasurable survival. Alongside the life instincts came the death instincts — the ] which Freud articulated relatively late in his career in 'the hypothesis of a ''death instinct'', the task of which is to lead organic life back into the inanimate state'.<ref>Freud, ''On Metapsychology'' p. 380</ref> For Freud, 'the death instinct would thus seem to express itself - though probably only in part - as an ''instinct of destruction'' directed against the external world and other organisms'<ref>Freud, ''On Metapsychology'' p. 381</ref>: through aggression. Freud considered that 'the id, the whole person...originally includes all the instinctual impulses...the destructive instinct as well'<ref>Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 138</ref> as ] or the life instincts. | |||

| To overcome this the ego employs ]s. Defense mechanisms reduce the tension and anxiety by disguising or transforming the impulses that are perceived as threatening.<ref name="Meyers">{{cite book |last=Meyers |first=David G. |author-link=David Myers (academic) |title=Psychology Eighth Edition in Modules |publisher=Worth Publishers |year=2007 |chapter=Module 44 The Psychoanalytic Perspective |isbn=978-0-7167-7927-8}}</ref> ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. His daughter ] identified the concepts of ], ], ], ], ], ], inversion, ], ], and substitution. | |||

| ==Ego== | |||

| ], 1923)]]In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted as being half in the conscious, a quarter in the ], and the other quarter in the ]. | |||

| The Ego acts according to the ]; i.e. it seeks to please the id’s drive in realistic ways that will benefit in the long term rather than bringing grief.<ref name="Child Development">{{cite journal | |||

| | last1 = Noam | first1 = Gil G. | |||

| | last2 = Hauser | first2 = Stuart T. | |||

| | last3 = Santostefano | first3 = Sebastiano | |||

| | last4 = Garrison | first4 = William | |||

| | last5 = Jacobson | first5 = Alan M. | |||

| | last6 = Powers | first6 = Sally I. | |||

| | last7 = Mead | first7 = Merrill | |||

| | title = Ego Development and Psychopathology: A Study of Hospitalized Adolescents | |||

| | journal = Child Development | |||

| | volume = 55 | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| | pages = 189–194 | |||

| | publisher = ] on behalf of the ] | |||

| | date = February 1984 | |||

| }}</ref> At the same time, Freud concedes that as the ego 'attempts to mediate between id and reality, it is often obliged to cloak the ''Ucs.'' commands of the id with its own ''Pcs.'' ]s, to conceal the id's conflicts with reality, to profess...to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding'.<ref name="Freud, p. 110">Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 110</ref> | |||

| === Superego === | |||

| The Ego comprises that organised part of the personality structure that includes defensive, perceptual, intellectual-cognitive, and executive functions. Conscious awareness resides in the ego, although not all of the operations of the ego are conscious. Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean a sense of self, but later revised it to mean a set of psychic functions such as judgement, tolerance, reality-testing, control, planning, defence, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory.<ref name="Snowden"/> The ego separates out what is real. It helps us to organize our thoughts and make sense of them and the world around us.<ref name="Snowden"/>"The ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world ... The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions ... in its relation to the id it is like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse; with this difference, that the rider tries to do so with his own strength, while the ego uses borrowed forces".<ref>Freud,''The Ego and the Id'', ''On Metapsychology'' p. 363-4</ref> Still worse, "it serves three severe masters...the external world, the super-ego and the id".<ref name="Freud, p. 110"/> Its task is to find a balance between primitive drives and reality while satisfying the id and super-ego. Its main concern is with the individual's safety and allows some of the id's desires to be expressed, but only when consequences of these actions are marginal. "Thus the ego, driven by the id, confined by the super-ego, repulsed by reality, struggles... bringing about harmony among the forces and influences working in and upon it", and readily "breaks out in anxiety - realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the super-ego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id".<ref>Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 110-1</ref> It has to do its best to suit all three, thus is constantly feeling hemmed by the danger of causing discontent on two other sides. It is said, however, that the ego seems to be more loyal to the id, preferring to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the super-ego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of ], ], and inferiority. | |||

| The superego reflects the internalization of cultural rules, mainly as absorbed from parents, but also other authority figures, and the general cultural ethos. Freud developed his concept of the superego from an earlier combination of the ] and the "special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured...what we call our 'conscience'."<ref>Freud, ''On Metapsychology'' pp. 89–90.</ref> For him the superego can be described as "a successful instance of identification with the parental agency", and as development proceeds it also absorbs the influence of those who have "stepped into the place of parents — educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models". | |||

| {{blockquote|Thus a child's super-ego is in fact constructed on the model not of its parents but of its parents' super-ego; the contents which fill it are the same and it becomes the vehicle of tradition and of all the time-resisting judgments of value which have propagated themselves in this manner from generation to generation.<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933). pp. 95–6.</ref>}} | |||

| The superego aims for perfection.<ref name="Meyers"/> It is the part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency, commonly called "]", that criticizes and prohibits the expression of drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions. Thus the superego works in contradiction to the id. It is an internalized mechanism that operates to confine the ego to socially acceptable behaviour, whereas the id merely seeks instant self-gratification.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Calian|first=Florian|title=Plato's Psychology of Action and the Origin of Agency|publisher=L'Harmattan|year=2012|isbn=978-963-236-587-9|pages=17–19}}</ref> | |||

| To overcome this the ego employs ]s. The defense mechanisms are not done so directly or consciously. They lessen the tension by covering up our impulses that are threatening.<ref name="Meyers">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Meyers | |||

| | first = David G. | |||

| | authorlink = David Myers (academic) | |||

| | title = Psychology Eighth Edition in Modules | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year = 2007 | |||

| | chapter = Module 44 The Psychoanalytic Perspective | |||

| | isbn = 9780716779278 }}</ref> | |||

| Ego defense mechanisms are often used by the ego when id behavior conflicts with reality and either society's morals, norms, and taboos or the individual's expectations as a result of the internalisation of these morals, norms, and their taboos. | |||

| The superego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the ].<ref name="Sédat">{{cite journal | |||

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. However, his daughter ] clarified and identified the concepts of ], ], ], ], ], ], inversion, ], ], and substitution. | |||

| ], 1923)]]In a diagram of the ], the ego is depicted to be half in the consciousness, while a quarter is in the ] and the other quarter lies in the ]. | |||

| In modern English, ego has many meanings. It could mean one’s self-esteem, an inflated sense of self-worth, or in philosophical terms, one’s self. Ego development is known as the development of multiple processes, cognitive function, defenses, and interpersonal skills or to early adolescence when ego processes are emerged.<ref name="Child Development"/> | |||

| ==Super-ego== | |||

| Freud developed his concept of the super-ego from an earlier combination of the ego ideal and the 'special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured...what we call our "conscience"'.<ref>Freud, ''On Metapsychology'' p. 89-90</ref> For him 'the installation of the super-ego can be described as a successful instance of identification with the parental agency', while as development proceeds 'the super-ego also takes on the influence of those who have stepped into the place of parents - educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models'.<ref>Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 95-6</ref> | |||

| The Super-ego aims for perfection.<ref name="Meyers"/> It comprises that organised part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ], spiritual goals, and the psychic agency (commonly called "conscience") that criticises and prohibits his or her drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions. 'The Super-ego can be thought of as a type of conscience that punishes misbehavior with feelings of guilt. For example, for having extra-marital affairs'.<ref>Arthur S. Reber, ''The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology'' (1985)</ref> | |||

| The Super-ego works in contradiction to the id. The Super-ego strives to act in a socially appropriate manner, whereas the id just wants instant self-gratification. The Super-ego controls our sense of right and wrong and guilt. It helps us fit into society by getting us to act in socially acceptable ways.<ref name="Snowden"/><br />The Super-ego's demands oppose the id’s, so the ego has a hard time in reconciling the two.<ref name="Meyers"/> | |||

| Freud's theory implies that the super-ego is a symbolic internalisation of the ] and cultural regulations. The super-ego tends to stand in opposition to the desires of the id because of their conflicting objectives, and its aggressiveness towards the ego. The super-ego acts as the ], maintaining our sense of morality and proscription from taboos. The super-ego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the ].<ref name="Sédat">{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Sédat | first = Jacques | | last = Sédat | first = Jacques | ||

| | author-link = Jacques Sédat | |||

| | title = Freud | | title = Freud | ||

| | journal = Collection Synthèse | | journal = Collection Synthèse | ||

| | volume = 109 | | volume = 109 | ||

| | isbn = |

| isbn = 978-2-200-21997-0<!--, 1590510062--> | ||

| | publisher = ] | | publisher = ] | ||

| | year = 2000 }}</ref> |

| year = 2000 }}</ref> In the case of the little boy, it forms during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex, through a process of identification with the father figure, following the failure to retain possession of the mother as a love-object out of ]. Freud described the superego and its relationship to the father figure and Oedipus complex thus: | ||

| {{ |

{{blockquote|The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on—in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt.<ref>Freud, '']''.</ref>}} | ||

| In '']'', Freud presents "the general character of harshness and cruelty exhibited by the ideal — its dictatorial ''Thou shalt''". The earlier in the child's development, the greater the estimate of parental power. | |||

| The concept of super-ego and the Oedipus complex is subject to criticism for its perceived sexism. Women, who are considered to be already castrated, do not identify with the father, and therefore, for Freud, 'their super-ego is never so inexorable, so impersonal, so independent of its emotional origins as we require it to be in men....they are often more influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility'.<ref>Sigmund Freud, ''On Sexuality'' (Penguin Freud Library 7) p. 342</ref> He went on however to modify his position to the effect 'that the majority of men are also far behind the masculine ideal and that all human individuals, as a result of their bisexual disposition and of cross-inheritance, combine in themselves both masculine and feminine characteristics'.<ref>Freud, ''On Sexuality'' p. 342</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|. . . nor must it be forgotten that a child has a different estimate of his parents at different periods of his life. At the time at which the Oedipus complex gives place to the super-ego they are something quite magnificent; but later, they lose much of this. Identifications then come about with these later parents as well, and indeed they regularly make important contributions to the formation of character; but in that case they only affect the ego, they no longer influence the super-ego, which has been determined by the earliest parental images.|''New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis'', p. 64.}} | |||

| Thus when the child is in rivalry with the parental imago<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://dictionary.apa.org/imago|title = APA Dictionary of Psychology}}</ref> it feels the dictatorial ''Thou shalt''—the manifest power that the imago represents—on four levels: (i) the auto-erotic, (ii) the narcissistic, (iii) the anal, and (iv) the phallic.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Pederson|first1=Trevor|title=The Economics of Libido: Psychic Bisexuality, the Superego, and the Centrality of the Oedipus Complex|date=2015|publisher=Karnac}}</ref> Those different levels of mental development, and their relations to parental imagos, correspond to specific id forms of aggression and affection.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hommel|first=Bernhard|date=2019-10-01|title=Affect and control: A conceptual clarification|url=https://zenodo.org/record/3634804|journal=International Journal of Psychophysiology|language=en|volume=144|pages=1–6|doi=10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.07.006|pmid=31362029|s2cid=198998249|issn=0167-8760|hdl=1887/81987|hdl-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In Sigmund Freud's work ''Civilization and Its Discontents'' (1930) he also discusses the concept of a "cultural super-ego". Freud suggested that the demands of the super-ego 'coincide with the precepts of the prevailing cultural super-ego. At this point the two processes, that of the cultural development of the group and that of the cultural development of the individual, are, as it were, always interlocked'.<ref>Sigmund Freud, ''Civilization, Society and Religion'' (Penguin Freud Library 12) p. 336</ref> ] are a central element in the demands of the cultural super-ego, but Freud (as analytic moralist) protested against what he called 'the unpsychological proceedings of the cultural super-ego...the ethical demands of the cultural super-ego. It does not trouble itself enough about the facts of the mental constitution of human beings'.<ref>Freud, ''Civilization'' p. 337</ref> | |||

| The concept of the Oedipus complex internalised in the superego - anchored by Freud in the hypothetical murder of the forefather of the Darwinian horde by his sons - has been criticised for its supposed sexism. Women, who cannot develop a fear of castration due to their different genital make-up, do not identify with the father. Therefore, ‘their superego is never as implacable, as impersonal, as independent of its emotional origins as we demand of men...they are often more influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility.’ - not by fear of castration, as was the case with ‘Little Hans’ in his conflict with his father over his wife and mother.<ref>Sigmund Freud, ''On Sexuality'' (Penguin Freud Library 7) p. 342.</ref> However, Freud went on to modify his position to the effect "that the majority of men are also far behind the masculine ideal and that all human individuals, as a result of their human identity, combine in themselves both masculine and feminine characteristics, otherwise known as human characteristics."<ref>Freud, ''On Sexuality'' p. 342.</ref> | |||

| ==Advantages of the structural model== | |||

| == Structural model and neuropsychoanalysis == | |||

| Freud's earlier, topographical model of the mind had divided the mind into the three elements of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. At its heart was 'the dialectic of unconscious traumatic memory versus consciousness...which soon became a conflict between System Ucs versus System Cs'.<ref>James S. Grotstein, in Neville Symington, ''Narcissism: A New Theory'' (London 2003) p. x</ref> With what Freud called the 'disagreeable discovery that on the one hand (super-)ego and conscious and on the other hand repressed and unconscious are far from coinciding',<ref>Sigmund Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis'' (Penguin Freud Library 2) p. 101</ref> Freud took the step in the structural model to 'no longer use the term "unconscious" in the systematic sense', and to rename 'the mental region that is foreign to the ego... in future call it the "id"'.<ref>Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 104</ref> The partition of the psyche defined in the structural model is thus one that cuts across the topographical model's partition of "conscious vs. unconscious". | |||

| ] | |||

| Freud's basic metapsychological thesis is that the living ''soul'' with their needs, consciousness and memory resembles a psychological apparatus to which ''"spatial extension and composition of several pieces"'' can be attributed (...) and wich ''"locus ... is the brain (nervous system)"''.<ref>Sigmund Freud: ''Abriß der Psychoanalyse''. (1938), p. 6</ref> | |||

| Modern technology has made possible to observe the bioelectrical activity of neurones in the living brain. <ref name="Solms 133–145">{{Cite journal|last1=Solms|first1=Mark|last2=Turnbull|first2=Oliver H.|date=January 2014|title=What Is Neuropsychoanalysis?|journal=Neuropsychoanalysis|volume=13|issue=2|pages=133–145}}</ref> This led to the realisation in which area of the brain the needs for food, skin desire etc. begin to show themselves neuronally; where the highest performances of consciously thinking ego take place (s. ]); and that other parts of the brain are specialised in storing memorys: one of the main function of the superego. | |||

| 'The new terminology which he introduced has a highly clarifying effect and so made further clinical advances possible'.<ref>Angela Richards "Editor's Introduction" Freud, ''On Metapsychology'' p. 344-5</ref> Its value lies in the increased degree of precision and diversification made possible: although the id is unconscious by definition, the ego and the super-ego are both partly conscious and partly unconscious. What is more, with this new model Freud achieved a more systematic classification of mental disorder than had been available previously: | |||

| {{quote|"] correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; ], to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and ], to one between the ego and the external world."|Freud|'']'' (1923)}} | |||

| Decisive for this view was Freuds ]. Written in 1895, it develops the thesis that experiences are stored into the neuronal network through ''"a permanent change after an event"''. Freud soon abandoned this attempt and left it unpublished.<ref>Freud, Sigmund. 1966 . "." Pp. 347–445 in '']'' 3, edited by ]. London: ].</ref> Insights into the neuronal processes that permanently store experiences in the brain – like engraving the proverbial ] with some code – belongs to the ] branch of science and lead in a different direction of research than the psychological question of what the differences between consciousness and unconsciousness are. Freud's point of view was that ''consciousness'' is directly given – cannot be explained by insights into physiological details. Essentially, two things were known about the living soul: The brain with its nervous system extending over the entire organism and the acts of consciousness. According to Freud, therefore haphazard phenomena can be integrated between "''both endpoints of our knowledge''" (findings of modern neurology just as well as the position of our planet in the universe, for example), but this only contribute to the spatial "''localisation of the acts of consciousness''", not to their understanding.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Freud |first1=Sigmund |title=Abriß der Psychoanalyse, Gesammelte Werke |date=1940 |pages=63−138, here S. 67}}</ref> | |||

| It is important to realise however 'the three newly presented entities, the id, the ego and the superego, all had lengthy past histories (two of them under other names)'<ref>Angela Richards, "Editor's Introduction" in ''On Metapsychology'' p. 345</ref> - the id as the systematic unconscious, the super-ego as conscience/ego ideal. Equally, Freud never abandoned the topographical division of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious - though as he noted ruefully 'the three qualities of consciousness and the three provinces of the mental apparatus do not fall together into three peaceful couples...we had no right to expect any such smooth arrangement'.<ref>Freud, ''New Introductory Lectures'' p. 104-5</ref> | |||

| == Advantages of the structural model == | |||

| ==Translation== | |||

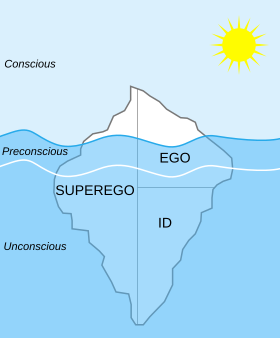

| ] metaphor. It is often used to illustrate the spatial relationship between Freud's first model and his new structural model of the soul (id, ego, superego).]] | |||

| In the '''topographic model''' of the soul, his first one, Freud divided mental phenomena into three regions: the Conscious, of whose contents the mind is aware at every moment, including information and stimuli from internal and external sources; the preconscious, whose material is merely latent (not directly present to thinking and feeling, but capable of becoming so without great effort); and the unconscious, which consists of biological needs and impulses that are made inaccessible to the conscious mind as a result of traumatic experiences in such a way that Freud describes this process as the pathological act of ]. With the introduction of the structural model, Freud intended to separate the terms unconscious and conscious from their spatially opposing meanings by formulating the three instances of id, ego and superego, which interlock with each other through their specific functions in a similar way to the organelles of a cell or parts of a machine, for example. The subdivision of the psyche outlined in the structural model is not a replacement for the topological division into ‘conscious vs. unconscious’, but rather a supplement."<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933). p. 104.</ref> | |||

| The terms "id," "ego," and "super-ego" are not Freud's own. They are latinisations by his translator ]. Freud himself wrote of "'''das Es'''," "'''das Ich'''," and "'''das Über-Ich'''"—respectively, "the It," "the I," and the "Over-I" (or "Upper-I"); thus to the German reader, Freud's original terms are more or less self-explanatory. Freud borrowed the term "das Es" from ], a German physician to whose unconventional ideas Freud was much attracted (Groddeck's translators render the term in English as "the It").<ref name="Groddeck">{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Groddeck | |||

| | first = Georg | |||

| | authorlink = Georg Groddeck | |||

| | title = The Book of the It | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | issue = 49 | |||

| | year = 1928 }}</ref> | |||

| The word ''ego'' is taken directly from ], where it is the ] of the first person singular ] and is translated as "I myself" to express emphasis. | |||

| Freud conceptualised the structural model because it allowed for a greater degree of precision and diversification. While the need contents of the id are initially unconscious (can become unconscious again as a result of an act of repression), the contents of the ego (such as thinking, perception) and the superego (memory; imprinting) can be both conscious and unconscious. Freud argued that his new model included the option of scientifically describing the structure and functions of the mentally healthy living being and therefore represented an effective diagnostic tool for clarifying the causes of mental disorders: {{blockquote|] correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; ], to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and ], to one between the ego and the external world.<ref>Freud, '']''</ref>}} | |||

| Figures like ] have criticized the way 'the English translations impeded students' efforts to gain a true understanding of Freud'<ref>Quoted in Neville Symington, ''Narcissism: A New Theory'' (London 1996) p. 10</ref> by substituting the formalised language of the ] for the homely immediacy of Freud's own language. | |||

| The three newly presented entities, however, remained closely connected to their previous conceptions, including those that went under different names – the systematic unconscious for the id, and the conscience/ego ideal for the superego.<ref>Angela Richards, "Editor's Introduction" in ''On Metapsychology'' p. 345.</ref> Freud never abandoned the topographical division of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious, though he noted that "the three qualities of consciousness and the three provinces of the mental apparatus do not fall together into three peaceful couples...we had no right to expect any such smooth arrangement."<ref>Sigmund Freud (1933). pp. 104–5.</ref> | |||

| ==Notable appearances in popular culture== | |||

| {{In popular culture|date=April 2011}} | |||

| *In the classic 1956 movie ], the destructive forces at large on the planet Altair IV are finally revealed to be "monsters from the id" -- destructive psychological urges unleashed upon the outside world through the operation of the Krells' 'mind-materialisation machine'. The example is of significance because of the unusual degree of insight it demonstrates: the creature eventually revealed follows classical psychoanalytic theory in being literally a dream-like primary process 'condensation' of different animal parts. The plaster cast of its footprint, for example, reveals a feline pad combined with an avian claw. As a crew member observes: "Anywhere in the galaxy this is a nightmare". | |||

| ] | |||

| The iceberg metaphor shows nothing of the physiological (real) structure of the brain, the possible organic correspondences of the three psychic instances or their functions. Instead it is a commonly used visual metaphor depicting the relationship between the ego, id and superego agencies (structural model) and the conscious and unconscious psychic systems (topographic model). In the iceberg metaphor the entire id and part of both the superego and the ego are submerged in the underwater portion representing the unconscious region of the psyche. The remaining portions of the ego and superego are displayed above water in the conscious region.<ref name="Carlson"/> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| '''People:''' | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| ==History and translation of the terms== | |||

| '''Related topics:''' | |||

| The terms "id", "ego", and "superego" are not Freud's own; they are Latinizations by his translator ]. Freud himself wrote of "''] ]''",<ref name="Es">{{cite book |first1=Jean |last1=Laplanche |first2=Jean-Bertrand |last2=Pontalis |author-link1=Jean Laplanche |author-link2=Jean-Bertrand Pontalis |chapter=Id |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RptYDwAAQBAJ&q=%22Id+%3D+D.\+Es%22&pg=PT363 |title=The Language of Psychoanalysis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RptYDwAAQBAJ |publisher=] |location=] |year=2018 |orig-date=1973 |isbn=978-0-429-92124-7}}</ref> "''das ]''",<ref name="Ich">Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (2018) . "".</ref> and "''das ]Ich''"<ref name="Über-Ich">Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (2018) . "".</ref>—respectively, "the It", "the I", and "the Over-I". Thus, to the German reader, Freud's original terms are to some degree self-explanatory. The term "''das Es''" was originally used by ], a physician whose unconventional ideas were of interest to Freud (Groddeck's translators render the term in English as "the It").<ref name="Groddeck">Original German: {{cite book |last=Groddeck |first=Georg |author-link=Georg Groddeck |title=Das Buch vom Es. Psychoanalytische Briefe an eine Freundin |url=https://archive.org/details/Groddeck_1923_Das_Buch_vom_Es_k |publisher=Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag |location=] |year=1923|language=de}}<br/>English translation: {{cite book |last=Groddeck |first=Georg |author-mask=3 |title=The Book of the It: Psychoanalytic Letters to a Friend |url=https://archive.org/details/b29815101 |year=1928 |place=New York / Washington |publisher=Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company}}</ref> The word '']'' is taken directly from ], where it is the ] of the first person singular ] and is translated as "I myself" to express emphasis. | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| Figures like ] have criticised the way "the English translations impeded students' efforts to gain a true understanding of Freud"<ref>Quoted in Neville Symington, ''Narcissism: A New Theory'' (London 1996) p. 10.</ref> by substituting the formalised language of the ] for the quotidian immediacy of Freud's own language. | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == See also == | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| {{div col}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link|Censorship (psychoanalysis)}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link|Ego death}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link|Plato's theory of soul}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link|Psychology of self}} | |||

| * {{Annotated link|Resistance (psychoanalysis)}} | |||

| {{div end}} | |||

| ==References== | == References == | ||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | == Further reading == | ||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Freud | first1 = Sigmund | date = April 1910 | title = The Origin and Development of Psychoanalysis | jstor = 1413001| journal = ] | volume = 21 | issue = 2| pages = 181–218| doi = 10.2307/1413001 }} | |||

| * Freud, Sigmund (1920), '']''. | |||

| * Freud, Sigmund (1923), ''Das Ich und das Es'', Internationaler Psycho-analytischer Verlag, Leipzig, Vienna, and Zurich. English translation, '']'', ] (trans.), Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-analysis, London, UK, 1927. Revised for ''The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud'', ] (ed.), W.W. Norton and Company, New York City, NY, 1961. | |||

| * Freud, Sigmund (1923), "Neurosis and Psychosis". The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923–1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works, 147–154 | |||

| * Gay, Peter (ed., 1989), ''The Freud Reader''. W.W. Norton. | |||

| * ] (root text): Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche (commentary), Peter Roberts (translator) (2001) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120324044909/http://www.rinpoche.com/teachings/conwisdom.pdf |date=2012-03-24 }} | |||

| * Kurt R. Eissler: | |||

| == External links == | |||

| *Freud, Sigmund (1910), "The Origin and Development of Psychoanalysis", ''American Journal of Psychology'' 21(2), 196–218. | |||

| * | |||

| *Freud, Sigmund (1920), ''Beyond the Pleasure Principle''. | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211023012047/http://12palmsrehab.com/blog/sigmund-freud-and-the-freud-archives.html |date=2021-10-23 }} | |||

| *Freud, Sigmund (1923), ''Das Ich und das Es'', Internationaler Psycho-analytischer Verlag, Leipzig, Vienna, and Zurich. English translation, ''The Ego and the Id'', ] (trans.), Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-analysis, London, UK, 1927. Revised for ''The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud'', ] (ed.), W.W. Norton and Company, New York, NY, 1961. | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110903210026/http://allpsych.com/psychology101/ego.html |date=2011-09-03 }}, Chapter 3: Personality Development Psychology 101. | |||

| *Freud, Sigmund (1923), "Neurosis and Psychosis". The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923–1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works, 147-154 | |||

| * | |||

| *Gay, Peter (ed., 1989), ''The Freud Reader''. W.W. Norton. | |||

| * , ] | |||

| *] (root text): Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche (commentary), Peter Roberts (translator) (2001) | |||

| * | |||

| *Kurt R. Eissler: | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Sigmund Freud}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| *, Chapter 3: Personality Development Psychology 101. | |||

| * | |||

| *, ] | |||

| * | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Id, Ego, And Super-Ego}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Id, Ego, And Super-Ego}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:03, 12 January 2025

Psychological concepts by Sigmund Freud| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: grammar, encyclopedic diction, as per WP:MOS. Please help improve this article if you can. (January 2025) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

For other uses, see Ego (disambiguation), ID (disambiguation), and Superego (disambiguation).

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

Sigmund Freud's couch Sigmund Freud's couch |

| Concepts |

| Important figures |

Important works

|

| Schools of thought |

| Training |

| See also |

The id, ego and superego are the three different, functionally interlocking main components of the human soul, as investigated and defined by Sigmund Freud. They represent the structural model of psychoanalysis. Freud himself used the German terms das Es, Ich, and Über-Ich. The Latin terms id, ego and superego were chosen by his original translators and have remained in use. The terms soul and psyche here are synonymous in the sense of the human organism as a whole, focussing on the mental aspect without any option of concrete separability from matter and therefore in strict distinction to the religious concept of "soul".

The structural model of the soul was introduced in Freuds essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). It describes the innate needs of the id located in the unconscious as a primary process, which the conscious mind - the secondary process - evaluates with participation of its socialisation and strives to satisfy via appropriate objects of external reality. This model - further refined and formalised in subsequent essays as The Ego and the Id - represents a response to the ambiguous/contradictory use of the terms conscious and unconscious in the topological model, the first one.

According to Freud as well as ego psychology the id is a set of uncoordinated instinctual needs; the superego plays the judgemental role via internalized experiences; and the ego is the perceiving, logically organizing agent that mediates between the id's innate desires, the demands of external reality and those of the critical superego; Freud compared the ego - in its relation to the id - to a man on horseback: the rider must restrain and direct the superior energy of his animal and at times allow for a satisfaction of its urges if he wants to keep it alive and the species healthy. The ego is thus "in the habit of transforming the id's will into action, as if it were its own."

Psychic apparatus

In order to overcome difficulties of understanding as far as possible, Freud formulated his "metapsychology" which for Lacan represents a technical elaboration of the concepts of the soul model: dividing the organism into three instances the id is regarded as the germ from which the ego and the superego develop. Driven by an energy that Freud calls libido in direct reference to Plato's Eros, the instances complement each other through their specific functions in a similar way to the organelles of a cell or parts of a technical apparatus.

Further distinctions (as the coordinates of topology, dynamics and economy) encouraged Freud to assume that the metapsychological elaboration of the structural model would make it fully compatible with biological sciences such as evolutionary theory and enable a well-founded concept of mental health including a theory of human development, which naturally completed in three successive stages: the oral, anal and genital phase. However, as important as this is for the diagnostic process (illness can only be realised as a deviation from the optimal cooperation of all psycho-organic functions), Freud had to be modest and leave structural model in the unfinished state of a torso because - as he stated one last time in Moses and Monotheism - there was no well-founded primate research at the time. Without knowledge of the instinctive social behaviour with the corresponding structure of cohabitation of our genetically closest relatives in realm of primates, Freud's thesis of Darwin's primordial horde (as presented for discussion in Totem and Taboo) can't be tested and, if possible, replaced by a realistic model. Horde life and its violent abolition through introduction of mononogamy (as an agreement between the sons who murdered the horde's polygamous father) embody the evolutionary as well as cultural-prehistorical core of psychoanalysis. It stands in contrast to the religiously enigmatic reports about the origin of monogamous couples on earth as an expression of divine will, but closer to the ancient trap to pacify political conflicts among the groups of Neolithic mankind. (See Prometheus' uprising against Zeus, who created Pandora as a fatal wedding gift for Epimetheus to divide and rule the titanic brothers; Plato's myth of spherical men cut into isolated individuals for the same reason; and the similarly resolved revolt of inferior gods in the Flood epic Atra-Hasis). Additional important assumptions are based on it, such as the Oedipus complex, the origin of moral-totemic rules like Incest taboo and, not least, Freud's Unease in Culture. Nonetheless, due to the lack of ethological primate research, these ideas remained an unproven belief of palaeo-anthropological science – only a hypothesis or "just so story as a not unpleasant English critic wittily called it. But I mean it honours a hypothesis if it shows capable of creating context and understanding in new areas."

Id

Freud conceived the id as the unconscious source of all innate needs, emotional impulses and desires, including the sexual drive. The id acts driven by aggression (energy), it's "the dark, inaccessible part of our personality". It seems limited to analysis of dreams and neurotic symptoms, and can only be described in terms of its contrast with the ego. It has no organisation and no collective will: It only demands immediate gratification of its instincts according to the pleasure principle. It is oblivious to reason and the presumptions of ordinary conscious life: "contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other. . . There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation. . . nothing which corresponds to the idea of time." The id "knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality. ...Instinctual cathexes seeking discharge—that, in our view, is all there is in the id."

Developmentally, the id precedes the ego. The id consists of the basic instinctual drives that are present at birth, inherent in the somatic organization, and governed only by the pleasure principle. The psychic apparatus begins as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured "ego", a concept of self that takes the principle of reality into account.

Freud understands the id as "the great reservoir of libido", the energy of desire as expressed, for example, in the behaviours of sexuality, the incorporation of food or the baby-care (maternal love). In general, the nature of libido is that of Platonic Eros, a universal desire that is inherent in all life instincts. They constantly strive to compensate for the processes of biological decay, rejuvenating the species of living beings by means of their metabolism and reproduction.

Complementing this constructive aspect of the libido, the author later postulated an inherent death drive, the Thanatos that has a decomposing effect and seeks "to lead organic life back into the inanimate state. For Freud, "the death instinct would thus seem to express itself—though probably only in part—as an instinct of destruction directed against the external world and other organisms" through aggression. Since libido energy encompasses all instinctive impulses, Eros and Thanatos are regarded as fundamental forces of the id, which co-operate despite their apparent incompatibility: The organism has the urge to 'synthetically' regenerate by integration of suitable molecules or energy into itself, for this purpose it must first deconstruct the ingested food complexes: the ‘analytical’ effect of stomach acid.

Ego

The ego acts according to the reality principle. It analyses complex perceptions (things, ideas, dreams), synthesises the appropriate parts into logically coherent interpretations (also models) and rules the muscular apparatus. Since the id's drives are frequently incompatible with the moral prescriptions and religious illusions of contemporary cultures, the ego attempts to direct the libidinal energy and satisfy its demands in accordance with the imperatives of that reality. According to Freud the ego, in its role as mediator between the id and reality, is often "obliged to cloak the (unconscious) commands of the id with its own preconscious rationalizations, to conceal the id's conflicts with reality, to profess...to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding."

Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean the sense of self, but later expanded it to include psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory. The ego is the organizing principle upon which thoughts and interpretations of the world are based.

According to Freud, "the ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. ...The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions... it is like a tug of war... with the difference that in the tug of war the teams fight against one another in equality, while the ego is against the much stronger 'id'." In fact, the ego is required to serve "three severe masters...the external world, the superego and the id." It seeks to find a balance between the natural drives of the id, the limitations imposed by reality, and the strictures of the superego. It is concerned with self-preservation: it strives to keep the id's instinctive needs within limits, adapted to reality and submissive to the superego.

Thus "driven by the id, confined by the superego, repulsed by reality" the ego struggles to bring about harmony among the competing forces. Consequently, it can easily be subject to "realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the superego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id." The ego may wish to serve the id, trying to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts, while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the superego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority.

To overcome this the ego employs defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms reduce the tension and anxiety by disguising or transforming the impulses that are perceived as threatening. Denial, displacement, intellectualization, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalization, reaction formation, regression, repression, and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. His daughter Anna Freud identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealization, identification, introjection, inversion, somatization, splitting, and substitution.

In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted as being half in the conscious, a quarter in the preconscious, and the other quarter in the unconscious.

Superego

The superego reflects the internalization of cultural rules, mainly as absorbed from parents, but also other authority figures, and the general cultural ethos. Freud developed his concept of the superego from an earlier combination of the ego ideal and the "special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured...what we call our 'conscience'." For him the superego can be described as "a successful instance of identification with the parental agency", and as development proceeds it also absorbs the influence of those who have "stepped into the place of parents — educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models".

Thus a child's super-ego is in fact constructed on the model not of its parents but of its parents' super-ego; the contents which fill it are the same and it becomes the vehicle of tradition and of all the time-resisting judgments of value which have propagated themselves in this manner from generation to generation.

The superego aims for perfection. It is the part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency, commonly called "conscience", that criticizes and prohibits the expression of drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions. Thus the superego works in contradiction to the id. It is an internalized mechanism that operates to confine the ego to socially acceptable behaviour, whereas the id merely seeks instant self-gratification.

The superego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the Oedipus complex. In the case of the little boy, it forms during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex, through a process of identification with the father figure, following the failure to retain possession of the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration. Freud described the superego and its relationship to the father figure and Oedipus complex thus:

The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on—in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt.

In The Ego and the Id, Freud presents "the general character of harshness and cruelty exhibited by the ideal — its dictatorial Thou shalt". The earlier in the child's development, the greater the estimate of parental power.

. . . nor must it be forgotten that a child has a different estimate of his parents at different periods of his life. At the time at which the Oedipus complex gives place to the super-ego they are something quite magnificent; but later, they lose much of this. Identifications then come about with these later parents as well, and indeed they regularly make important contributions to the formation of character; but in that case they only affect the ego, they no longer influence the super-ego, which has been determined by the earliest parental images.

— New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, p. 64.

Thus when the child is in rivalry with the parental imago it feels the dictatorial Thou shalt—the manifest power that the imago represents—on four levels: (i) the auto-erotic, (ii) the narcissistic, (iii) the anal, and (iv) the phallic. Those different levels of mental development, and their relations to parental imagos, correspond to specific id forms of aggression and affection.

The concept of the Oedipus complex internalised in the superego - anchored by Freud in the hypothetical murder of the forefather of the Darwinian horde by his sons - has been criticised for its supposed sexism. Women, who cannot develop a fear of castration due to their different genital make-up, do not identify with the father. Therefore, ‘their superego is never as implacable, as impersonal, as independent of its emotional origins as we demand of men...they are often more influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility.’ - not by fear of castration, as was the case with ‘Little Hans’ in his conflict with his father over his wife and mother. However, Freud went on to modify his position to the effect "that the majority of men are also far behind the masculine ideal and that all human individuals, as a result of their human identity, combine in themselves both masculine and feminine characteristics, otherwise known as human characteristics."

Structural model and neuropsychoanalysis

Freud's basic metapsychological thesis is that the living soul with their needs, consciousness and memory resembles a psychological apparatus to which "spatial extension and composition of several pieces" can be attributed (...) and wich "locus ... is the brain (nervous system)".

Modern technology has made possible to observe the bioelectrical activity of neurones in the living brain. This led to the realisation in which area of the brain the needs for food, skin desire etc. begin to show themselves neuronally; where the highest performances of consciously thinking ego take place (s. frontal lobe); and that other parts of the brain are specialised in storing memorys: one of the main function of the superego.

Decisive for this view was Freuds Project for a Scientific Psychology. Written in 1895, it develops the thesis that experiences are stored into the neuronal network through "a permanent change after an event". Freud soon abandoned this attempt and left it unpublished. Insights into the neuronal processes that permanently store experiences in the brain – like engraving the proverbial tabula rasa with some code – belongs to the physiological branch of science and lead in a different direction of research than the psychological question of what the differences between consciousness and unconsciousness are. Freud's point of view was that consciousness is directly given – cannot be explained by insights into physiological details. Essentially, two things were known about the living soul: The brain with its nervous system extending over the entire organism and the acts of consciousness. According to Freud, therefore haphazard phenomena can be integrated between "both endpoints of our knowledge" (findings of modern neurology just as well as the position of our planet in the universe, for example), but this only contribute to the spatial "localisation of the acts of consciousness", not to their understanding.

Advantages of the structural model

In the topographic model of the soul, his first one, Freud divided mental phenomena into three regions: the Conscious, of whose contents the mind is aware at every moment, including information and stimuli from internal and external sources; the preconscious, whose material is merely latent (not directly present to thinking and feeling, but capable of becoming so without great effort); and the unconscious, which consists of biological needs and impulses that are made inaccessible to the conscious mind as a result of traumatic experiences in such a way that Freud describes this process as the pathological act of repression. With the introduction of the structural model, Freud intended to separate the terms unconscious and conscious from their spatially opposing meanings by formulating the three instances of id, ego and superego, which interlock with each other through their specific functions in a similar way to the organelles of a cell or parts of a machine, for example. The subdivision of the psyche outlined in the structural model is not a replacement for the topological division into ‘conscious vs. unconscious’, but rather a supplement."

Freud conceptualised the structural model because it allowed for a greater degree of precision and diversification. While the need contents of the id are initially unconscious (can become unconscious again as a result of an act of repression), the contents of the ego (such as thinking, perception) and the superego (memory; imprinting) can be both conscious and unconscious. Freud argued that his new model included the option of scientifically describing the structure and functions of the mentally healthy living being and therefore represented an effective diagnostic tool for clarifying the causes of mental disorders:

Transference neuroses correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; narcissistic neuroses, to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and psychoses, to one between the ego and the external world.

The three newly presented entities, however, remained closely connected to their previous conceptions, including those that went under different names – the systematic unconscious for the id, and the conscience/ego ideal for the superego. Freud never abandoned the topographical division of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious, though he noted that "the three qualities of consciousness and the three provinces of the mental apparatus do not fall together into three peaceful couples...we had no right to expect any such smooth arrangement."

The iceberg metaphor shows nothing of the physiological (real) structure of the brain, the possible organic correspondences of the three psychic instances or their functions. Instead it is a commonly used visual metaphor depicting the relationship between the ego, id and superego agencies (structural model) and the conscious and unconscious psychic systems (topographic model). In the iceberg metaphor the entire id and part of both the superego and the ego are submerged in the underwater portion representing the unconscious region of the psyche. The remaining portions of the ego and superego are displayed above water in the conscious region.

History and translation of the terms

The terms "id", "ego", and "superego" are not Freud's own; they are Latinizations by his translator James Strachey. Freud himself wrote of "das Es", "das Ich", and "das Über-Ich"—respectively, "the It", "the I", and "the Over-I". Thus, to the German reader, Freud's original terms are to some degree self-explanatory. The term "das Es" was originally used by Georg Groddeck, a physician whose unconventional ideas were of interest to Freud (Groddeck's translators render the term in English as "the It"). The word ego is taken directly from Latin, where it is the nominative of the first person singular personal pronoun and is translated as "I myself" to express emphasis. Figures like Bruno Bettelheim have criticised the way "the English translations impeded students' efforts to gain a true understanding of Freud" by substituting the formalised language of the elaborated code for the quotidian immediacy of Freud's own language.

See also

- Censorship (psychoanalysis) – Barrier of the conscious and unconscious

- Ego death – Complete loss of subjective self-identity

- Plato's theory of soul – Plato's account of the soul as consisting of logical, spirited, and appetitive parts

- Psychology of self – Study of the representation of one's identity

- Resistance (psychoanalysis) – Term used in psychoanalysis describing oppositional behaviors

References

- The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, Third Edition (1999) Allan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, Eds. pp. 256–257.