| Revision as of 09:25, 29 March 2012 editOmen1229 (talk | contribs)947 edits Undid revision 484492312 by Koertefa (talk) source was not removal← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:35, 6 January 2025 edit undo94.253.183.158 (talk)No edit summary | ||

| (641 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|West Slavic ethnic group}} | ||

| {{for|information on the population of Slovakia|Demographics of Slovakia}} | |||

| |group='''Slovaks<br>(Slováci)''' | |||

| {{Update|part=Statistics|reason=Data present are from the early 1990s|date=August 2024}} | |||

| |image=] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2023}} | |||

| <small>], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]</small></div> | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| |poptime= ] '''6 - 6.5 million''' | |||

| | group = Slovaks<br /> ''Slováci'' | |||

| |popplace={{Flag icon|Slovakia}} ] 4,614,854<ref name = gov-stats>{{cite web | title =Slovakia: Ethnicity of the Population Section | publisher = Government of Slovakia |year=2010 | url =http://www.government.gov.sk/10134/slovakia.php?menu=1293 | accessdate = 5 Oct. 2010 }}</ref><br> | |||

| | native_name = | |||

| {{USA}}: 790,000<ref name="USZZ.sk">(2010 census)</ref><br> | |||

| | native_name_lang = | |||

| {{CZE}}: 200,000<ref></ref><br> | |||

| | flag = <!-- Don't add any flags as this article is about an ethnic group living in several different countries, and not about the citizens of, or about the, Republic of Slovakia. --> | |||

| {{CAN}}: 64,145-100,000<ref name="USZZ.sk"/><br> | |||

| | flag_caption = | |||

| {{SRB}}: 59,021<br> | |||

| | image = Map of the Slovak Diaspora in the World.svg | |||

| {{UK}}: 45,000<ref></ref><br> | |||

| | pop = '''{{circa}} 6–7 million'''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sme.sk/c/2422124/Ako-ziju-Slovaci-za-hranicami-Slovensko-mam-rad-ale-mojim-domovom-uz-nie-je.html|title=Ako žijú Slováci za hranicami? Slovensko mám rád, ale mojím domovom už nie je.|trans-title=How do Slovaks live abroad? I like Slovakia but it is no longer my home.|website=Sme.sk|access-date=2 August 2017|archive-date=3 August 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170803005021/https://www.sme.sk/c/2422124/ako-ziju-slovaci-za-hranicami-slovensko-mam-rad-ale-mojim-domovom-uz-nie-je.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {{IRL}}: 30,000<ref name="USZZ.sk"/><br> | |||

| | popplace = {{Flag icon|Slovakia}} ] 4,567,547<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.scitanie.sk/vysledky-v-kombinacii|title=Národnosť a materin. jazyk|website=scitanie.sk|access-date=2022-10-13|archive-date=2022-10-13|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221013214515/https://www.scitanie.sk/vysledky-v-kombinacii|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {{AUT}}: 25,000<ref name="USZZ.sk"/><br> | |||

| | region1 = {{USA}} | |||

| {{GER}}: 20,200<br> | |||

| | pop1 = 416,047 (2022); 750,000 (estimate) | |||

| {{HUN}}: 17,693<ref></ref><br> | |||

| | ref1 = <ref>{{cite web |title=Census Reporter: People Reporting Multiple Ancestry |url=https://censusreporter.org/data/table/?table=B04005&geo_ids=01000US&primary_geo_id=01000US#valueType{{!}}estimate |website=censusreporter.org |access-date=16 August 2024}}</ref><ref name="uszz">{{cite web |title=Office for Slovaks living abroad |url=https://www.uszz.sk/krajania/ |website=USZZ |language=sk-SK}}</ref> | |||

| {{ROU}}: 17.226<ref></ref><br> | |||

| | region2 = {{CZE}} | |||

| {{FRA}}: 13,000<br> | |||

| | pop2 = 162,578 (2021 census); 200,000–400,000 (estimates) | |||

| {{AUS}}: 12,000<br> | |||

| | ref2 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.tyden.cz/rubriky/domaci/slovaku-v-cesku-pribyva-tvori-petinu-vsech-cizincu-v-zemi_524806.html|title=Slováků v Česku přibývá, tvoří pětinu všech cizinců v zemi|website=týden.cz|date=15 June 2019|access-date=25 June 2020|archive-date=28 June 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200628080812/https://www.tyden.cz/rubriky/domaci/slovaku-v-cesku-pribyva-tvori-petinu-vsech-cizincu-v-zemi_524806.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| {{UKR}}: 6,397<br> | |||

| | region3 = {{CAN}} | |||

| {{HRV}}: 4,712<br> | |||

| | pop3 = 68,210; (including 14,910 first generation immigrants); 100,000 (estimate) | |||

| {{BEL}}: 4,000<ref name="USZZ.sk"/><br> | |||

| | ref3 = <ref>{{cite web |title=Ethnic or cultural origin by generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts |url=https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810033801 |website=www150.statcan.gc.ca |access-date=16 August 2024 |date=26 October 2022}} | |||

| {{POL}}: 2,000 | |||

| </ref><ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region4 = {{GER}} | |||

| Other: 120,000 (est.){{Citation needed|date=February 2007}} | |||

| | pop4 = 64,745; 80,000 (estimate) | |||

| |langs=] | |||

| | ref4 = <ref>{{cite web |title=Federal Statistical Office Germany - GENESIS-Online |url=https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online?operation=ergebnistabelleUmfang&levelindex=3&levelid=1723797138038&downloadname=12521-0002#abreadcrumb |website=www-genesis.destatis.de |access-date=16 August 2024 |language=en |date=16 August 2024}}</ref><ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| |rels= ] 73%,<br> ] 10.8%,<br> other or unspecified 3.2%, (including 50,363 Orthodox Christians), ], ] or ] 13% (2001 ] within Slovakia, extrapolated to outside Slovaks) | |||

| | region5 = {{AUT}} | |||

| |related=Other ], especially other ]<br><small>] are the most related</small><ref> | |||

| | pop5 = 63,621 (2020); 65,000 (estimate) | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| | ref5 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| |url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_family.asp?subid=292-16 | |||

| | region6 = {{UK}} | |||

| |title=Ethnologue - Slavic languages | |||

| | pop6 = 58,000; 135,000 (estimate) | |||

| |publisher=www.ethnologue.com | |||

| | ref6 = <ref>{{cite web |title=Population of the UK by country of birth and nationality: individual country data (Discontinued after June 2021) - Office for National Statistics |url=https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/datasets/populationoftheunitedkingdombycountryofbirthandnationalityunderlyingdatasheets |website=www.ons.gov.uk |access-date=16 August 2024}}</ref><ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| |accessdate=2011-03-16 | |||

| | region7 = {{SRB}} | |||

| |last= | |||

| | pop7 = 41,730 (2021); 40,000 (estimate) | |||

| |first= | |||

| | ref7 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| | region8 = {{HUN}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| | pop8 = 29,794 (2021); 75,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref8 = <ref name="KSH">{{cite book|last=Vukovich|first=Gabriella|url=http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/mikrocenzus2016/mikrocenzus_2016_12.pdf|title=Mikrocenzus 2016 - 12. Nemzetiségi adatok|trans-title=2016 microcensus - 12. Ethnic data|language=hu|publisher=Hungarian Central Statistical Office|location=Budapest|year=2018|access-date=9 January 2019|isbn=978-963-235-542-9|archive-date=8 August 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190808024307/http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/mikrocenzus2016/mikrocenzus_2016_12.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region9 = {{SUI}} | |||

| | pop9 = 20,581 (2021); 25,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref9 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region10 = {{BRA}} | |||

| | pop10 = 17,200 | |||

| | ref10 = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://epoca.globo.com/edic/214/soci1a.htm|access-date=January 31, 2008|title=Edição 214, Um atalho para a Europa|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090126010348/http://epoca.globo.com/edic/214/soci1a.htm|archive-date=26 January 2009|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| | region11 = {{DEN}}{{NOR}}{{SWE}} | |||

| | pop11 = 17,000 (estimated total in Scandinavian countries) | |||

| | ref11 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region12 = {{ESP}} | |||

| | pop12 = 12,350 (2021); 15,000(estimate) | |||

| | ref12 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region13 = {{IRL}} | |||

| | pop13 = 10,801; 15,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref13 = <ref name="CSO Emigration">{{cite web | url=http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/documents/census2011profile6/Profile%206%20Migration%20and%20Diversity%20Commentary.pdf | title=CSO Emigration | publisher=Census Office Ireland | access-date=January 29, 2013 | archive-date=November 13, 2012 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121113165431/http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/documents/census2011profile6/Profile%206%20Migration%20and%20Diversity%20Commentary.pdf | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region14 = {{ROU}} | |||

| | pop14 = 10,300 (2021 census) 13,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref14 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region15 = {{FRA}} | |||

| | pop15 = 9,768 (2017); 20,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref15 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region16 = {{ITA}} | |||

| | pop16 = 9,014 (2021); 20,000 (estimates) | |||

| | ref16 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region17 = {{NLD}} | |||

| | pop17 = 9,000 (2022); 15,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref17 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region18 = {{ISR}} | |||

| | pop18 = 8,000 (2020); up to 70,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref18 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region19 = {{BEL}} | |||

| | pop19 = 6,677 (2022 census); 10,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref19 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region20 = {{UKR}} | |||

| | pop20 = 6,700 (estimate) | |||

| | ref20 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region21 = {{AUS}} | |||

| | pop21 = 4,781 (2021 census), 9,000-15,000 (estimates) | |||

| | ref21 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | region22 = {{HRV}} | |||

| | pop22 = 3,688 (2021 census); 5,000 (estimate) | |||

| | ref22 = <ref name="uszz"></ref> | |||

| | langs = ] | |||

| | rels = Majority ] with Minorities of ], ], other | |||

| | related = ], other ]<br>{{hlist|(]|]|]|])}} | |||

| | region35 = Other | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Slovaks''' |

The '''Slovaks''' ({{langx|sk|Slováci}} {{IPA|sk|ˈsɫɔvaːt͡si|}}, singular: ''Slovák'' {{IPA|sk|ˈslɔvaːk|}}, feminine: ''Slovenka'' {{IPA|sk|ˈsɫɔvɛŋka|}}, plural: ''Slovenky'') are a ] ] and ] native to ] who share a common ], ], ] and speak the ]. | ||

| In Slovakia, {{circa}} 4.4 million are ethnic Slovaks of 5.4 million total population. There are Slovak minorities in many neighboring countries including ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] and sizeable populations of immigrants and their descendants in ], ], ], ], ] and the ] among others, which are collectively referred to as the ]. | |||

| == Name == | |||

| {{anchor|Name}} | |||

| The name ''Slovak'' is derived from ''*Slověninъ'', plural ''*Slověně'', the old name of the ] (], around 863).{{efn| | |||

| The Slovaks and ] are the only current Slavic nations that have preserved the original name. For Slovenes, the adjective is still ''slovenski'' and the feminine ] "Slovene" is still also ''Slovenka'', but the ] noun has since changed to ''Slovenec''. The Slovak name for their language is ''slovenčina'' and the Slovene name for theirs is ''slovenščina''. The Slovak term for ] is ''slovinčina''; and the Slovenes call Slovak ''slovaščina''. The name is derived from proto-Slavic form ''slovo'' "word, talk" (cf. Slovak ''sluch'', which comes from the IE root *ḱlew-). Thus ''Slovaks'' as well as ''Slovenians'' would mean "people who speak (the same language)", i.e. people who understand each other.}} The original stem has been preserved in all Slovak words except the masculine noun; the feminine ] is ''Slovenka'', the ] is ''slovenský'', the language is ''slovenčina'' and the country is ''Slovensko''. The first written mention of adjective ''slovenský'' (Slovak) is in 1294 (''ad parvam arborem nystra slowenski breza ubi est meta'').{{sfn|Uličný|1986|p=102}} | |||

| The original name of Slovaks ''Slověninъ''/''Slověně'' was still recorded in Pressburg Latin-Czech Dictionary (the 14th century),{{sfn|Uličný|1986|p=101}} but it changed to ''Slovák'' under the influence of ] and ] (around 1400). The first written mention of new form in the territory of present-day Slovakia is from ] (1444, "''Nicoulaus Cossibor hauptman, Nicolaus Czech et Slowak, stipendiarii supremi''"). The mentions in Czech sources are older (1375 and 1385).{{sfn|Marek|2011|p=67}} The change is not related to the ethnogenesis of Slovaks, but exclusively to linguistic changes in the West Slavic languages. The word ''Slovak'' was used also later as a common name for all Slavs in Czech, Polish, and also Slovak together with other forms.{{sfn|Marek|2011|p=67}} | |||

| In Hungarian, "Slovak" is '']'' (pl: ''tótok''), an ]. It was originally used to refer to all ]s including ] and ]s, but eventually came to refer primarily to Slovaks. Many place names in Hungary such as ], ], and ] still bear the name. ] is a common Hungarian surname. | |||

| The Slovaks have also historically been variously referred to as ''Slovyenyn'', ''Slowyenyny'', ''Sclavus'', ''Sclavi'', ''Slavus'', ''Slavi'', ''Winde'', ''Wende'', or ''Wenden''. The final three terms are variations of the Germanic term ], which was historically used to refer to any Slavs living close to Germanic settlements. | |||

| == Ethnogenesis == | |||

| ] (portrait from 1885)]] | |||

| The early Slavs came to the territory of Slovakia in several waves from the 5th and 6th centuries and were organized on a tribal level. Original tribal names are not known due to the lack of written sources before their integration into higher political units. Weakening of tribal consciousness was probably accelerated by ], who did not respect tribal differences in the controlled territory and motivated remaining Slavs to join together and to collaborate on their defense. In the 7th century, Slavs founded a larger tribal union: ]. Regardless of Samo's empire, the integration process continued in other territories with various intensities.{{sfn|Marsina|2013|p=65}} | |||

| The final fall of the ] allowed new political entities to arise. The first such political unit documented by written sources is the ], one of the foundations of later common ethnic consciousness.{{sfn|Marsina|2013|p=67}} At this stage in history it is not yet possible to assume a common identity of all ancestors of Slovaks in the neighboring eastern territories, even if it was inhabited by closely related Slavs. The Principality of Nitra became a part of ], a common state of Moravians (Czech ancestors were joined only for a few years). The relatively short existence of Great Moravia prevented it from suppressing differences which resulted from its creation from two separate entities, and therefore a common "Slovak-Moravian" ethnic identity failed to develop.{{sfn|Marsina|2013|p=67}} The early political integration in the territory of present-day Slovakia was, however, reflected in linguistic integration. While dialects of the early ancestors of Slovaks were divided into West Slavic (western and eastern Slovakia) and non-West Slavic (central Slovakia), between the 8th and 9th centuries both dialects merged, thus laying the foundations of a later Slovak language. | |||

| The 10th century is a milestone in the Slovak ].{{sfn|Marsina|2009|p=16}} The fall of Great Moravia and further political changes supported their formation into a separate nation. At the same time, with the extinction of the ] language, between the 10th and 13th centuries Slovak evolved into an independent language (simultaneously with other Slavic languages). The early existence of the Kingdom of Hungary positively influenced the development of common consciousness and companionship among Slavs in the Northern Hungary, not only within boundaries of present-day Slovakia.{{sfn|Marsina|2013|p=67}} The clear difference between Slovaks and Hungarians made adoption of a specific name unnecessary and Slovaks preserved their original name (in Latin e.g. ''Slavus''), which was also used in communication with other Slavic peoples (Polonus, Bohemus, Ruthenus).{{sfn|Marsina|2013|p=71}} In political terms, the medieval Slovaks were a part of the multi-ethnic political nation '']'', together with Hungarians (or, more exactly, Magyars), Slavonians, Germans, Romanians and other ethnic groups in the Kingdom of Hungary. Since a medieval political nation did not consist of ordinary people but nobility, membership of the privileged class was necessary for all these peoples (''nobiles Hungary'').{{sfn|Marek|2011|p=13}} | |||

| Like other nations, the Slovaks began to transform into a modern nation from the 18th century under the idea of ]. The modern Slovak nation is the result of radical processes of modernization within the Habsburg Empire which culminated in the middle of the 19th century.<ref name="Auer">Stefan Auer, , Routledge, 2004, p. 135</ref> The transformation process was slowed down by conflict with Hungarian nationalism and the ethnogenesis of the Slovaks become a political question, particularly regarding their deprivation and preservation of their language and national rights. In 1722, ], professor of law at the ], published a theory that nobility and burghers of ] should not have same privileges as Hungarians, because they are descendants of ]'s people (inferior to Magyars). Neither Bencsik nor his Slovak opponent ] put the continuity of settlement into serious question. Also, the first history of Slovaks written by Georgius Papanek (or Juraj Papánek), traced the roots of the Slovaks to Great Moravia<ref name=Kamusella134>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009|p=134}}</ref> in ''Historia gentis Slavae. De regno regibusque Slavorum...'' (1780) ("History of the Slovak nation: On the kingdom and kings of the Slovaks").<ref>{{cite web |last1=Papánek |first1=Juraj |title=Historia gentis Slavae / Dejiny slovenského národa |url=https://www.databazeknih.cz/knihy/historia-gentis-slavae-dejiny-slovenskeho-naroda-386992 |website=Databazeknih.cz |publisher=Perfekt |access-date=21 June 2022 |archive-date=21 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220621100727/https://www.databazeknih.cz/knihy/historia-gentis-slavae-dejiny-slovenskeho-naroda-386992 |url-status=live }}</ref> Papánek's work became a basis for argumentation of the Slovak national revival movement. However, the Slovak national revival not only accepted the continuity of population but also emphasized it, thus proving that Slovaks are equal citizens of the state and neither a Hungarian "unique statesmanlike gift" nor Christianization was required for the foundation of the state. | |||

| In 1876, Hungarian linguist ] published a theory about missing continuity between Slovaks and Slavs before the arrival of the Hungarians. Hunfalvy tried to prove that ancestors of Slovaks did not live in the territory of the present-day Slovakia before arrival of the old Hungarians (Magyars), but Slovaks emerged later from other Slavs who came to the Kingdom of Hungary from neighbouring countries after the 13th century.{{sfn|Marsina|2009|p=18}} ] assumed that central and northern Slovakia were uninhabited (1901) and in his next work "Our historical right to the territorial integrity of our country" (1921) he claimed that the remainder of the original Slavs were assimilated by Magyars and modern Slovaks are descendants of immigrants from Upper Moravia and ] (the population density on these territories was too low in that time and large numbers of colonists coming from these areas was not possible{{sfn|Marsina|2009|p=18}}). The theory was then misused by inter-war Hungarian revisionists, who questioned continuity to support Hungarian claims on Slovakia. In 1982, when rich archaeological evidence proving the opposite was already available,{{sfn|Marsina|2009|p=19}} a similar theory was published by Hungarian historian ].{{sfn|Marsina|2009|p=19}} Györffy accepted that smaller groups of Slavs could remain in the territory of Slovakia, but stated that the Slovaks' origin was in sparse settlement of various Slavic groups strengthened by later colonization. According to Ferenc Makk, the medieval ] are not the ancestors of Slovaks and the majority of the Slovak people are descended from later Slavic newcomers.<ref>Ferenc, Makk, " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161031030309/http://www.lib.jgytf.u-szeged.hu/folyoiratok/tiszataj/96-10/makk.pdf |date=2016-10-31 }}", In: Tiszatáj, 1996-10, p. 76</ref> | |||

| Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent ] (circa 5,050,000). There are Slovak ] in the ], ], ] and sizeable populations of immigrants and their descendants in the ] and in ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The opposite theory, supporting the supposed ], thus also legitimizing the creation of the united ],<ref name=Marsina17>{{Harvnb|Marsina|1997|p=17}}</ref> gained political support in inter-war Czechoslovakia.<ref name=Marsina17/> Like Karácsonyi, Czech historian ] assumed that northern and central parts of Slovakia remained uninhabited until the 13th century and that the south-western part was inhabited by Czechs. Yet, in 1946 Chaloupecký assumed that the Slovak nation emerged from neighboring Slavs and had been formed only in the 17th century. His theory about the lack of population in the greater part of Slovakia covered by forests had already been scientifically refuted by ] (e.g. in ''O starý Liptov'', 1934), and was proven wrong by numerous archaeological finds<ref group="note">For example Slavic mounds in Krasňany near Žilina, cemetery in Martin, magnate mounds in Turčianska Blatnica, Malý Čepčín and Žabokreky, settlements in Liptovský Michal, Liptovská Mara (unearthed during construction of the water dam), Vlachy, Liptovská Štiavnica, Paludza, Sokolče, Lisková, Podtureň, Prosiek, Bobrovník, Likavka – all of them from 8–10th century. (Uhlár, 1992, p. 326)</ref> and rejected by Czechoslovak historiography. On the other hand, inter-war Slovak autonomists, opposing ethnic Czechoslovakism, dated the existence of the Slovak nation to the time of Pribina (trials to document existence of Slovaks in early Slavic era, i.e. in the time of Samo's empire, are marginal and exist outside of modern mainstream Slovak historiography). | |||

| After the ] in 1993, the formation of independent Slovakia motivated interest in a particularly Slovak national identity.<ref name="Warhola">{{cite web|url=http://www.umaine.edu/polisci/files/2010/04/mpsa05_proceeding_84621.pdf|title=Changing Rule Between the Danube and the Tatras: A study of Political Culture in Independent Slovakia, 1993 – 2005|last=W. Warhola|first=James|year=2005|work=The ]|publisher=Midwest Political Science Association 2005 Annual National Conference, April 9, 2005|location=], United States.|access-date=2011-06-15|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120915011227/http://www.umaine.edu/polisci/files/2010/04/mpsa05_proceeding_84621.pdf|archive-date=September 15, 2012}}</ref> One reflection of this was the rejection of the common Czechoslovak national identity in favour of a purely Slovak one.<ref name="Warhola"/> | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| Line 49: | Line 125: | ||

| === Great Moravia === | === Great Moravia === | ||

| ], ruler of Principality of Nitra |

], ruler of Principality of Nitra,<ref name=Kirschbaum25>{{Harvnb|Kirschbaum|1995| p=25}}</ref> established and ruled the ] from 839/840 to 861.<ref>{{cite book | ||

| | last = Bagnell Bury | | last = Bagnell Bury | ||

| | first = John | | first = John | ||

| Line 56: | Line 132: | ||

| | year = 1923 | | year = 1923 | ||

| | location = Cambridge | | location = Cambridge | ||

| | url = |

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=_9IHAAAAIAAJ&q=Balaton+Principality | ||

| | isbn = | |||

| | page = 211}}</ref>]] | | page = 211}}</ref>]] | ||

| ] (833 - |

] (833 – 902-907) was a Slavic state in the 9th and early 10th centuries, whose creators were the ancestors of the Czechs and Slovaks.<ref>Ference Gregory Curtis. Chronology of 20th-century eastern European history. Gale Research, Inc., 1994. {{ISBN|978-0-8103-8879-6}}, p. 103</ref><ref>{{cite book| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=5D4uAQAAIAAJ&q=%22great+moravia%22+ancestors+slovakq | title = The Great Moravia Exhibition: 1100 years of tradition of state and cultural life | last1 = Věd | first1 = Archeologický Ústav (Československá Akademie)| year = 1964}}</ref> Important developments took place at this time, including the mission of Byzantine monks ], the development of the ] alphabet (an early form of the ]), and the use of ] as the official and literary language. Its formation and rich cultural heritage have attracted somewhat more interest since the 19th century. | ||

| The original territory inhabited by the Slavic tribes included not only present-day Slovakia, but also parts of present-day Poland, southeastern Moravia and approximately the entire northern half of present-day Hungary.<ref>A history of Eastern Europe: crisis and change, Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries</ref> | The original territory inhabited by the Slavic tribes included not only present-day Slovakia, but also parts of present-day Poland, southeastern Moravia and approximately the entire northern half of present-day Hungary.<ref>A history of Eastern Europe: crisis and change, Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries</ref> | ||

| === Kingdom of Hungary === | === Kingdom of Hungary === | ||

| {{Main|History of Hungary}} | |||

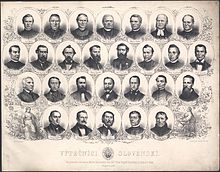

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]]] | ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]]] | ||

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ])]] | |||

| The territory of present |

The territory of present-day Slovakia was split in two parts between the ] (under Hungarian rule gradually from 907 to the early 14th century) to ] and ] (under the Habsburgs from 1527 – 1848 (see also ])) until the formation of ] in 1918.<ref name=Eberhardt105>{{Harvnb|Eberhardt|2003| p=105}}</ref> However, according to other historians, from 895 to 902, the whole area of the present-day Slovakia became part of the rising Principality of Hungary, and became (without gradation) part of the Kingdom of Hungary a century later.<ref>Kristó, Gyula (1996). Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 229. {{ISBN|963-482-113-8}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.historia.hu/archivum/2001/0103gyorffy.htm|title=Histria 2001/03. – GYRFFY GYRGY: Honfoglals a Krpt-medencben|website=Historia.hu|access-date=14 November 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140426200447/http://www.historia.hu/archivum/2001/0103gyorffy.htm|archive-date=26 April 2014|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>Kristó, Gyula (1993). A Kárpát-medence és a magyarság régmúltja (1301-ig) (The ancient history of the Carpathian Basin and the Hungarians – till 1301) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511173424/http://www.antikvarium.hu/ant/book.php?konyv-cim=a-karpat-medence-es-a-magyarsag-regmultja&ID=39250|date=2011-05-11}} Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 299. {{ISBN|963-04-2914-4}}.</ref> A separate entity called ], existed at this time within the Kingdom of Hungary. This duchy was abolished in 1107. The territory inhabited by the Slovaks in present-day Hungary was gradually reduced.<ref name="books.google.com">{{cite book|last1= Vauchez|first1= André|last2= Barrie Dobson|first2= Richard|first3= Michael|last3= Lapidge|title= Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages|volume= 1|year= 2000|publisher= Routledge|isbn= 9781579582821|page= 1363|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=om4olQhrE84C&q=slovakia+history+slavs&pg=PA1363|access-date= 2020-11-21|archive-date= 2023-04-07|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20230407092416/https://books.google.com/books?id=om4olQhrE84C&q=slovakia+history+slavs&pg=PA1363|url-status= live}}</ref> | ||

| When most of Hungary was conquered by the ] in 1541 (see ]), the territory of present-day ] became the new center of the reduced kingdom<ref name=Eberhardt104>{{Harvnb|Eberhardt|2003| p=104}}</ref> that remained under Hungarian, and later ] rule, officially called Royal Hungary.<ref name=Eberhardt104/> Some ] settled around and in present-day ] for similar reasons. Also, many ] settled in the Kingdom of Hungary,<ref name=Eberhardt104/> especially in the towns, as work-seeking colonists and mining experts from the 13th to the 15th century. ] and ] also formed significant populations within the territory.<ref name=Eberhardt104/> During the period, most of present-day Slovakia was part of Habsburg rule, but Ottoman ruled southern and southeasternmost parts of it. | |||

| After the Ottoman Empire was forced to retreat from present-day Hungary around 1700, thousands of Slovaks were gradually settled in depopulated parts of the restored Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Hungary, ], ], and ]) under ], and that is how present-day Slovak enclaves (like ], ]) in these countries arose. | |||

| After ], Upper Hungary (present-day Slovakia) was the most advanced part of the Kingdom of Hungary for centuries, but in the 19th century, when ]/] became the new capital of the kingdom, the importance of the territory, as well as other parts within the Kingdom fell, and many Slovaks were impoverished. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Slovaks emigrated to North America, especially in the late 19th and early 20th century (between cca. 1880–1910), a total of at least 1.5 million emigrants. | |||

| When most of ] was conquered by the ] in 1541 (see ]), ] (now the territory of present day ]) became the new center of the "reduced" kingdom<ref name=Eberhardt104>{{Harvnb|Eberhardt|2003| p=104}}</ref> that remained under Hungarian, and later ] rule, officially called ].<ref name=Eberhardt104/> Some ] settled around and in present-day ] for similar reasons. Also, many ] settled in the ],<ref name=Eberhardt104/> especially in the towns, as work-seeking colonists and mining experts from the 13th to the 15th century. Jews and Gypsies also formed significant populations within the territory.<ref name=Eberhardt104/> | |||

| Slovakia exhibits a very rich folk culture. A part of Slovak customs and ] are common with those of other nations of the former ] (the Kingdom of Hungary was in ] with the Habsburg monarchy from 1867 to 1918). | |||

| After the ] were forced to retreat from present-day Hungary around 1700, thousands of Slovaks were gradually settled in depopulated parts of the restored Kingdom of Hungary (present-day ], ], ], and ]) under ], and that is how present-day Slovak enclaves (like ], ]) in these countries arose. | |||

| After Transylvania, ] (the territory of present day Slovakia), was the most advanced part of the Kingdom of Hungary for centuries (the most urbanized part, intense mining of gold and silver), but in the 19th century, when ]/] became the new capital of the kingdom, the importance of the territory, as well as other parts within the Kingdom fell, and many Slovaks were impoverished. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Slovaks emigrated to ], especially in the late 19th and early 20th century (between cca. 1880–1910), a total of at least 1.5 million emigrants (~2/3 of them were part of some minority). | |||

| Slovakia exhibits a very rich folk culture. A part of Slovak customs and social convention are common with those of other nations of the former ] (the Kingdom of Hungary was in ] with the Habsburg monarchy from 1867 to 1918). | |||

| === Czechoslovakia === | === Czechoslovakia === | ||

| {{Main|History of Czechoslovakia}} | {{Main|History of Czechoslovakia}} | ||

| People of Slovakia spent most part of the 20th century within the framework of ], a new state formed after |

People of Slovakia spent most part of the 20th century within the framework of ], a new state formed after World War I. Significant reforms and post-World War II ] took place during this time. ] was strongly influenced by ] during this period.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uqOVrtwe4EYC&q=world+war+2+slovak+language+czech&pg=PA111|title=When East Met West: Sociolinguistics in the Former Socialist Bloc|first1=Jeffrey|last1=Harlig|first2=Csaba|last2=Pléh|date=11 January 1995|publisher=Walter de Gruyter|access-date=11 January 2018|via=Google Books|isbn=9783110145854|archive-date=7 April 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230407174603/https://books.google.com/books?id=uqOVrtwe4EYC&q=world+war+2+slovak+language+czech&pg=PA111|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| == Culture == | |||

| {{see also|List of Slovaks}} | |||

| The political transformations of ], ] and the accession to the ] in 2004 brought new liberties, which have considerably improved the outlook and prospects of all Slovaks. | |||

| The art of Slovakia can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when some of the greatest masterpieces of the country's history were created. Significant figures from this period included the many ]s, among them the ] and ]. More contemporary art can be seen in the shadows of ],<ref name=Cavendish>{{cite book |title=World and Its Peoples|last= Marshall Cavendish Corporation|year=2009 |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |volume=7|isbn= 9780761478836|chapter=Slovakia; Cultural expression|page=993}}</ref> ], ],<ref name=Miku>{{Harvnb|Mikuš|1977| p=108}}</ref> ],<ref name=Cavendish/> ].<ref name=Cavendish/> Julius Koller and Stanislav Filko, in the 21st century Roman Ondak, ]. The most important Slovak composers have been ], ], and ], in the 21st century Vladimir Godar and ]. | |||

| Contemporary Slovak society organically combines elements of both folk traditions and Western European lifestyles. | |||

| == Name and ethnogenesis == | |||

| ] (portrait from 1885)]] | |||

| The origin of the Slovaks is disputed among scholars and it is very contentious. The term of "Slovak" is problematic in relation of the medieval period, because it is essentially the product of the modern nationalism as it emerged after the 18th century.<ref>William Mahoney, , ABC-CLIO, 2011, p. 34</ref> Throughout history, the diverse theories regarding the ] of the Slovaks were used to justify or unjustify historical situations from variant historical perspectives,<ref name=Marsina17/> as the argument of ‘my-nation-was-here-first’ type was, and still remains to be a useful instrument of legitimizing a nation-state’s ownership of a given territory or its claim to an area outside its current borders.<ref name=Kamusella948>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=948}}</ref> The ] that the Slovaks are descended from the ] who inhabited the territory of present-day Slovakia ] has a long story and it is connected with the ambition of the Slovaks to reach ] or ] within ] (mostly under ] of the 19th century and during the Slovak ]). This continuity theory, supporting the supposed ], thus also legitimizating the creation of the united ],<ref name=Marsina17/> gained political subvention during the formation of ].<ref name=Marsina17/> After the ] in 1993, and the formation of independent Slovakia motivated interest in a particularly Slovak national identity.<ref name="Warhola">{{cite web|url=http://www.umaine.edu/polisci/files/2010/04/mpsa05_proceeding_84621.pdf|title=Changing Rule Between the Danube and the Tatras: A study of Political Culture in Independent Slovakia, 1993 - 2005|last=W. Warhola|first=James|year=2005|work=The ]|publisher=Midwest Political Science Association 2005 Annual National Conference, April 9, 2005|location=], ].|accessdate=2011-06-15}}</ref> One reflection of this was the rejection of the common Czechoslovak national identity in favour of a pure Slovak one.<ref name="Warhola"/> Although the definition and identification of the inhabitants of ] proved to be politically imperative and difficult,<ref name=Kirschbaum35/> additionally historical records are anything else but precise in this question,<ref name=Kirschbaum35/> the current consensus among most of the Slovak historians is that Slovaks exist as a people with consciousness of their national identity since the 9th or 10th century,<ref name=Kirschbaum37>{{Harvnb|Kirschbaum|1995| p=37}}</ref> therefore we can identify the Slavic inhabitants living on the territory of this realm as Slovaks. Other Slovak scholars view is, that the emergence of sense of a common Slovak nationhood did not appear until the 18th or 19th century.<ref name="Warhola"/> According to ] scholar ] tracing the roots of the Slovak nation to the times of Great Moravia, claiming the polity to have been the first Slovak state is nothing else but ''"ethnolinguistic Slovak nationalism"''.<ref name=Kamusella131>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=131}}</ref> This 'continuity theory' also contradicts with the internationally accepted theory that distinct Slavic nations had not yet emerged by the 9th century and the culture and language of various ] in ] were indistinguishable from each other.<ref name="bartl">{{cite journal|title=Ďurica, M. S.: Dejiny Slovenska a Slovákov|journal=Historický časopis|year=1997|first=Július|last=Bartl|coauthors=|volume=45|issue=1|pages=114–122|id= |url=|format=}}</ref> Naming various institutions after the saintly brothers and Great Moravian rulers and devoting commemorative plaques and monuments to them became widespread in post-1993 Slovakia.<ref name=Kamusella887>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=887}}</ref><ref group="note">The University in Nitra was named after St Cyril, and later the university in Trnava added both St Cyril and St Methodius to its name. Kamusella p.887</ref> The laudation of the imagined history of Slovak culture and language led to the myth of the Cyrillo-Methodian dawn of the Slovak nation and was incorporated into the 1991 Slovak ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.constitution.org/cons/slovakia.txt |title= Constitution of the Slovak Republic|author= Slovak National Council|year=1991 |work= |publisher= |accessdate=June 12, 2011}}</ref><ref name=Kamusella528>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=528}}</ref> which adverts the spiritual heritage of ] and the historical heritage of the Great Moravian Empire as inherently Slovak:<ref name=Kamusella528/> | |||

| {{Quote|''We, the Slovak nation, mindful of the political and cultural heritage of our forebears, and of the centuries of experience from the struggle for national existence and our own statehood, in the sense of the spiritual heritage of Cyril and Methodius and the historical legacy of the Great Moravian Empire, proceeding from the natural right of nations to self-determination...''|Preamble, Constitution of the Slovak Republic (1991)}} | |||

| There are Slovak historians who suggest that:<ref name=Kirschbaum35/> | |||

| {{Quote|''It is not correct to label Great Moravia as the first state of the Czechs and the Slovaks for the simple reason that the membership of the Czechs in this state had been short lived.''|Stanislav, Kirschbaum (1995), A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival, p. 35.}} | |||

| As Stanislav Kirschbaum points out:<ref name=Kirschbaum35>{{Harvnb|Kirschbaum|1995| p=35}}</ref> | |||

| {{Quote|''Slavist and literary historians consider the Cyrillo-Methodian literature as the heritage of all Slavs. Other claim that it is the heritage of the Slavs who laid the bases of the Empire of Great Moravia, namely the Slovaks, the Moravians and the Slovenes. Slovak scholars have been saying for three centuries that the literature created in Great Moravia or translated by Sts. Cyril and Methodius and their disciples for the ancestors of the Slovaks are rather part of the Slovak cultural heritage.''|Stanislav, Kirschbaum (1995), A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival, p. 35.}} | |||

| Cyrilo-Methodian motif has its stable place in the creation process of means of payment and money in Slovakia. However, there are not only motifs with religious or sacral subject matters. Considering multidimension – not only religious, but also humanistic, cultural, social, political, educational and scientific – importance of Sts. Cyril and Methodius’ missions, their portraits are traditionally depicted on medals, too, as these are related to the above mentioned fields of human activities. This fact aptly illustrates the importance of Slovak ancestors’ teachers whose humanistic message is still alive and topical in the present time.<ref>http://www.ukm.ff.ukf.sk/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/Kniha%20PoznavanieKDCM.pdf</ref> | |||

| Slovak holidays are based on the tradition and Slovak history. 5th of July, Memory of St. Cyril and St. Methodius – Brothers Cyril and Methodius compiled the Slavic alphabet and translated it into liturgical and biblical texts. They established several schools and training centers. One of the universities in Slovakia, in Trnava, is called Univerzita sv. Cyrila a Metoda (University of Sts. Cyril and Methodius).<ref>http://www.slovak-republic.org/holidays/</ref> | |||

| In this interpretation, the Slovaks have the oldest tradition of ] in ],<ref name=Kamusella134>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=134}}</ref> but unfortunately, the ']’ caused them to ‘forget’ their proud traditions.<ref name=Kamusella134/> Although the idea of the Cyrillo-Methodian heritage is very prevalent in nowadays ]. Some scholars claim there is no continuity in politics, culture<ref>Aviel Roshwald, , Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 9</ref>, or ] between this early Slavic polity and the modern Slovak nation.<ref name=Kamusella131/> | |||

| It seems reasonable to propose that the modern Slovaks may be descendants of the Great Moravian population,<ref name=Kamusella131/> this proposition is also true in the case of many modern Central European countries.<ref name=Kamusella131/> In fact denial of the continuity of the Slavs living in the territory of what is today Slovakia (before the eleventh century and those who have been living there since the eleventh century) is (also) incorrect. In particular the oldest local names in a written form can serve as evidence. On the basis of the known development of the (Slovak) language these names can serve for determining the time of their formation (before the thirteenth century; in the tenth century or before the tenth century). Therefore it should be adequate to deal with the ethnogenesis of Slovaks in more detail.<ref>http://www.sav.sk/journals/hum/full/hum197b.pdf</ref> The Catholic Church in Slovakia claims the ] from Great Moravia is still preserved in Slovakia, mainly in eastern Slovakia.<ref>http://www.kbs.sk/?cid=1184747346</ref> According to ] Timothy Haughton:<ref name="Haughton2005">{{cite book|author=Timothy Haughton|title=Constraints and opportunities of leadership in post-Communist Europe|url=|accessdate=12 June 2011|year=2005|publisher=Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.|isbn=978-0-7546-3903-9|pages=109}}</ref> | |||

| {{Quote|''The Great Moravian Empire is viewed by some as a kind of golden age of Slovak nationalism. Such harking back to distant history is not retricted to expat nationalist Slovak historians , but is also enshrined in the preamble to the Slovak constitution. The golden age view has much to do with the fact that the Great Moravian Empire was followed by what is labeled as '1000 years of Magyar rule', followed by seventy years of second class citizenship in Czechoslovakia.|Timothy, Haughton; (2005) Constraints and opportunities of leadership in post-Communist Europe, p. 109.}} | |||

| ] 9th century ruler of ] was erected on the courtyard of ] with a misleading inscription on the pedestal ''"which describes Svatopluk as a Slovak ruler when a separate Slovak identity did not emerge"''.<ref name=Sspect/> Slovak archaeologists recommended the removal of the inscription and ''"if the sculptor of the statue, does not agree with this, then the statue should be transferred to the ] as an example of political manoeuvring and mythologizing..."''<ref name=Sspect>{{Cite web | last =Vilikovská | first =Zuzana | title = Expert commission recommends relocating statue of Svätopluk from castle courtyard - The Slovak Spectator | url = http://spectator.sme.sk/articles/view/40027/10/expert_commission_recommends_relocating_statue_of_svatopluk_from_castle_courtyard.html | publisher = | date = | accessdate = 12 June 2011 }}</ref>]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The theory of the "Great Moravian" and "Cyrillo-Methodian" heritage dates back to the 18th century. In his writing (''Historia gentis Slavae. De regno regibusque Slavorum'' ) Georgius Papanek (or Juraj Papánek) traces the roots of the Slovaks to Great Moravia.<ref name=Kamusella134/> | |||

| According to the Czech priest ], Great Moravia was located in ] and ] (i.e. Present-day ] and ]). Writers of Slavic origin like Juraj Sklenár, and ] praised Great Moravia as opposed to the ‘heathen Magyars’ who destroyed this realm.<ref name=Kamusella479>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=479}}</ref> In 1879, ] wrote that Great Moravia was a common state of Slovaks and Moravians.<ref name=Kamusella816>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=816}}</ref> František Viktor Sasinek asseted in his work ''"Die Slovaken. Eine Ethnographische Skizze"'' (The Slovaks: An ethnographic outline) that Great Moravia was the state of the Slovaks, Moravians and Bohemians.<ref name=Kamusella814>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=814}}</ref> According to ] (''"O methode dejepisu Slovenska" '') Great Moravia was the state of the Czechoslovak nation,<ref name=Kamusella814/> but he agreed that the separate Slovak nation emerged after the Hungarians destroyed the polity.<ref name=Kamusella814/> Slovak historian Julius Botto Jr. asserted (''"Slováci. Vývin ich národného povedomia"'' ) that Great Moravia was solely a Slovak realm.<ref name=Kamusella814/> Interestingly, Samuel Timon ] priest claimed (''"Imago antiquae Hungariae"'' ) that the ], had liberated the Slovaks from the ] yoke.<ref name=Kamusella819>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=819}}</ref> It was ] who imprinted the idea of Great Moravia and the Cyrillo-Methodian literacy on the ideological blueprint of Slovak nationalism with his poems (''Svatopluk, 1833; Cyrilo-Methodiana, 1835; Slav, 1839'').<ref name=Kamusella479/> When the Slovaks and Czechs ] it was suggested that Great Moravia was the equal legacy of both nations.<ref name=Kirschbaum35/> However, Russian historian ] asserted that Great Moravia is the legacy exclusively of the Czechs.<ref name=Kirschbaum35/> | |||

| The opinion of ] historian János Karácsonyi was, that the indigenous Slavs had died out or they had been assimilated by Hungarians,<ref name=Marsina15/> therefore contemporary Slovaks are the progeny of the ]<ref name=Marsina15>{{Harvnb|Marsina|1997| p=15}}</ref> (arrived from the north and north-west by the twelfth century in to ]) the Czech (]n, ]n), Polish (]) and German (]n, ], ]n) settlers who came to Hungary during 10th–18th century. According to this theory, only a small part of present-day Slovakia was inhabited during the reign of ],<ref name=Marsina16>{{Harvnb|Marsina|1997| p=16}}</ref> thus there is no direct connection between the autochthonous Slavic population living in the territory of present-day Slovakia before the 12th century and modern Slovaks.<ref name=Marsina16-17>{{Harvnb|Marsina|1997| pp=16–17}}</ref> After the ], the theory of Karácsonyi became very popular among Hungarian politicians and it was utilized to prove the Hungarian view that the separation of the territory of Slovakia from Hungary was unjustified.<ref name=Marsina17/> Czech historian Václav Chaloupecký also admitted that most of the territory of present-day Slovakia (except the southern parts) was a primeval forest until the thirteenth century and an intentionally unpopulated frontier region of the ].<ref name=Marsina16/> Chaloupecký asserted that Slovaks are ] by origin but their almost 1000-years existence in the ] led to their separation from the Czech nation.<ref name=Marsina15/> Furthermore, he also considered that the ],<ref name=Marsina16/> especially in the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries were significant agents in the ethnogenesis of the Slovaks.<ref name=Marsina16/> However Chaloupecký had no doubts about that after the eleventh century the Slavonic inhabitants of south-western Slovakia were descendants of those Slavs who had lived there in the ninth and the tenth centuries.<ref name=Marsina17>{{Harvnb|Marsina|1997| p=17}}</ref> Regardless of the fact that modern historical and archaeological exploration in the | |||

| last decades showed the opinions of both Karácsonyi and Chaloupecký to be wrong, their views can be considered in a way identical as they both wanted to put forward arguments for the integrity and legitimacy of the Kingdom of Hungary and Czechoslovakia in the period of writing their works. None of them concealed their intentions, they even underlined it.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sav.sk/journals/hum/full/hum197b.pdf |title=ETHNOGENESIS OF SLOVAKS |publisher=SAV |accessdate=January 29, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ===Origin of the word 'Slovak'=== | |||

| {{anchor|Name}} | |||

| The Slovaks and ] are the only current Slavic nations that have preserved the old name of the ] (singular: ''slověn'') in their name - the ] "Slovak" is still ''slovenský'' and the feminine ] "Slovak" is still ''Slovenka'' in the Slovak language; only the ] noun "Slovak" changed to ''Slovenin'', probably in the ], and finally (under Czech and ] influence) to ''Slovák'' around 1400. For Slovenes, the adjective is still ''slovenski'' and the feminine ] "Slovene" is still ''Slovenka'', but the ] noun has since changed to ''Slovenec''. The Slovak name for their language is ''slovenčina'' and the Slovene name for theirs is ''slovenščina''. The Slovak term for the Slovene language is ''slovinčina''; and the Slovenes call Slovak ''slovaščina''. The name is derived from proto-Slavic form ''slovo'' "word, talk" (cf. Slovak ''sluch'', which comes from the IE root *ḱlew-). Thus ''Slovaks'' as well as ''Slovenians'' would mean "people who speak (the same language)", i.e. people who understand each other. | |||

| According to ] and modern Slavic linguists, the above-mentioned word ''slověn'' probably was the original name of all Slavs, but most Slavs (Czechs, Poles, Croats, etc.) took other names in the ]. Although the Slovaks themselves seem to have had a slightly different word for "Slavs" (''Slovan''), they were called "Slavs" by Latin texts approximately up to the High Middle Ages. Thus, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish when Slavs in general and when Slovaks are meant. One proof of the use of "Slavs" in the sense of "Slovaks" are documents of the ] which mention Bohemians (]), ] under a different name.<ref name="books.google.com"/> Slovaks of Hungary were dubbed as ''"Slavi Pannonii"''<ref name=Kamusella132>{{Harvnb|Kamusella|2009| p=132}}</ref> and Czechs as ''"Slavi Bohemii"''.<ref name=Kamusella132/> The semantic closeness of the ethnonym ‘Slovak’ to that of ‘Slav’ endowed the Slovak national movement with the myth that of all the Slavic nations the Slovaks are the most direct descendants of the original Slavs, and the Slovak language the most direct continuation of Old Slavic.<ref name=Kamusella132/> | |||

| ===Ethnic affiliations and genetic origins=== | |||

| Slovaks -as other slavonic ethnical groups in ]- carry ]n lineages as a consequence of admixture with ]n ], who ]d into Central and ] in the ].<ref>Malyarchuk, BA; Vanecek, T; Perkova, MA; Derenko, MV; Sip, M. "Mitochondrial DNA variability in the Czech population, with application to the ethnic history of Slavs; Hum Biol. 2006 Dec;78(6):681-96.". Institute of Biological Problems of the North, ]. Portovaya str. 18, 685000 Magadan, Russia.</ref> Slovak populations do not cluster together.<ref name=Genetics/> Western Slovaks are located together with the ] and ]s, while eastern Slovaks are placed close to ].<ref name=Genetics>{{Harvnb|Malyarchuk|Perkova|Derenko|Vanecek|Lazur|Gomolcak|2008| p=}}</ref> Slovak ]s belong to the common ]n ] ]s,<ref name=Genetics/> but characterized by a small frequency of East ]n (2,8 percent)<ref name=Genetics/> and ]-specific (2,8 percent)<ref name=Genetics/> mtDNA lineages.<ref name=Genetics/> Furthermore, ]n mtDNAs (L2a) are present in the population from the eastern part of the country.<ref name=Genetics/> About 3 percent of mtDNAs from eastern ] encompass Gypsy-specific lineages,<ref name=Genetics/> which belong to the ]n-specific haplogroups M5a1 and M35.<ref name=Genetics/> The Gypsy related J1 haplotype appeares in 2,9 percent of persons from eastern Slovakia.<ref name=Genetics/> The identified M-haplotype in Slovaks is also known among ]s, ] and ] from ].<ref name=Genetics/> | |||

| ===Quotes from important chronicles=== | |||

| This is how Nestor in his ] (historically correctly) describes the Slovaks{{Citation needed|date=November 2008}}: ''Slavs that were settled along the Danube, which have been occupied by the Hungarians, the Czechs, the Lachs, and Poles that are now known as the Rus''. Nestor calls these Slavs "Slavs of Hungary" in another place of the text, and mentions them in the first place in a list of Slavic nations (besides Moravians, Bohemians, Poles, Russians, etc.), because he considers the ] (including what is today Slovakia) the original Slavic territory. | |||

| Anonymus, in his ], calls the Slovaks (around 1200 with respect to past developments) ''Sclavi'', i.e. Slavs (as opposed to "Boemy" - the Bohemians, and "Polony" - the Poles) or in another place ''Nytriensis Sclavi'', i.e. ] Slavs. | |||

| And this is how Slovaks were called in various very precise sources approximately from 1200 to about 1400: ''Slovyenyn, Slowyenyny; Sclavus, Sclavi, Slavus, Slavi; Tóth; Winde, Wende, Wenden''. | |||

| == Culture == | |||

| :''See also ]'' | |||

| The most famous ]s can indubitably be attributed to invention and technology. Such people include ], the inventor of wireless telegraphy; ], ], inventor of the modern parachute; ], inventor of the bionic arm and pioneer in thermodynamics; and, more recently, ], father of modern acoustic string instruments. Hungarian inventors ] and ] were born of Slovak fathers. | |||

| The art of Slovakia can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when some of the greatest masterpieces of the country's history were created. Significant figures from this period included the many Masters, among them the ] and ]. More contemporary art can be seen in the shadows of ],<ref name=Cavendish>{{cite book |title=World and Its Peoples|last= Marshall Cavendish Corporation|first=|authorlink= |coauthors= |year=2009 |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |location= |volume=7|isbn= 0-7614-7883-3, 9780761478836|chapter=Slovakia; Cultural expression|page=993|pages= |url= |accessdate=|quote=|ref=harv}}</ref> ], ],<ref name=Miku>{{Harvnb|Mikuš|1977| p=108}}</ref> ],<ref name=Cavendish/> ].<ref name=Cavendish/> Julius Koller and Stanislav Filko, in the 21st century Roman Ondak, ]. The most important Slovak composers have been ], ], and ], in the 21st century Vladimir Godar and ]. | |||

| Slovakia is also known for its ], of whom include ], ], ], and its political revolutionaries, such ] and ]. | |||

| The most famous ]s can indubitably be attributed to invention and technology. Such people include ], the inventor of wireless telegraphy; ], ], inventor of the modern parachute; ], inventor of the bionic arm and pioneer in thermodynamics; and, more recently, ], father of modern acoustic string instruments. | |||

| Štefan Anián Jedlík | |||

| Slovakia is also known for its polyhistors, of whom include ], ], ], and its political revolutionaries, such ] and ]. | |||

| There were two leading persons who codified |

There were two leading persons who codified Slovak. The first one was ] whose concept was based on the dialect of western Slovakia (1787). It was the enactment of the first national standard language for the Slovaks. The second notable man was ]. His formation of Slovak had principles in the dialect of central Slovakia (1843). | ||

| The best known Slovak hero was ] (the Slovak equivalent of ]). |

The best known Slovak hero was ] (the Slovak equivalent of ]). The prominent explorer and diplomat ] was Slovak as well (he comes from Vrbové in present-day Slovakia and is e.g. listed as "nobilis Slavicus – Slovak nobleman" in his secondary school registration). | ||

| In terms of sports, the Slovaks are probably best known (in North America) for their hockey personalities, especially ], ], ], ] |

In terms of sports, the Slovaks are probably best known (in North America) for their ice hockey personalities, especially ], ], ], ], ] and ]. For a list see ]. ] is only the second European captain in history of the ] that led his team to win the ], winning it with the ] in the season ]. | ||

| For a list of the most notable Slovak writers and poets, see ]. | For a list of the most notable Slovak writers and poets, see ]. | ||

| == Maps == | |||

| <gallery> | <gallery> | ||

| File:Vojvodina west east slavs.png|Slovaks in Vojvodina, Serbia (2002 census) | |||

| File:MUTTICH 4.JPG|Girl from Slovakia | |||

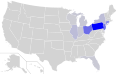

| File:Slovak USC2000 PHS.svg|The language spread of Slovak in the United States according to U. S. Census 2000 and other resources interpreted by research of U. S. English Foundation, percentage of home speakers | |||

| File:Jizda Kralu Vlcnov Czech Rep.jpg|Moravian-Slovak folk festival | |||

| File:Veľkonočný pondelok1.jpg|Easter in Slovakia | |||

| File:Campesino eslovaco de losMontes tatra.jpg|Slovak peasant from the Tatra mountains, 1908 | |||

| File:Daniela Hantuchová - Bank of the West Classic.jpg|Tennis player ] | |||

| File:Viola Valachová table.jpg| Viola Valachová a Partisan | |||

| File:Jana Kirschner KVIFF.jpg| ] pop singer | |||

| File:Adriana Sklenarikova Karembeu 2006.jpg| ] fashion model | |||

| File:RimSobota francisci rimavsky.jpg| Jan Francisci-Rimavsky poet and revolutionary | |||

| File:Stan Mikita.jpg| ] | |||

| File:Peter Stastny1.jpg| ] | |||

| File:Operace Anthropoid - Jozef Gabčík.jpg| ] Slovak soldier, assassin of Reinhard Heydrich | |||

| File:Michael Strank.jpg| ], U.S Marine of Slovak ancestry, One of the men who raised the flag in Iwo Jima. | |||

| File:Miroslaw Iringh Stanko.jpg| ], one of the Warsaw Uprising organisers. | |||

| File:] | |||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| ==Statistics== | == Statistics == | ||

| There are approximately 5.4 million autochthonous Slovaks in Slovakia. Further Slovaks live in the following countries (''the list shows estimates of embassies etc. and of associations of Slovaks abroad in the first place, and official data of the countries as of 2000/2001 in the second place''). | There are approximately 5.4 million autochthonous Slovaks in Slovakia. Further Slovaks live in the following countries (''the list shows estimates of embassies etc. and of associations of Slovaks abroad in the first place, and official data of the countries as of 2000/2001 in the second place''). | ||

| The list stems from Claude Baláž, a Canadian Slovak, the current plenipotentiary of the Government of the Slovak Republic for Slovaks abroad (see e.g.: <sup>6</sup>) |

The list stems from Claude Baláž, a Canadian Slovak, the current ] of the Government of the Slovak Republic for Slovaks abroad (see e.g.: <sup>6</sup>): | ||

| * |

* United States (1,200,000 / 821,325*) – 19th – 21st century emigrants; see also ]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/c2kbr-35.pdf|title=Ancestry: 2000 : Census 2000 Brief|website=Census.gov|access-date=2017-08-02|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040920132346/http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/c2kbr-35.pdf|archive-date=2004-09-20}}</ref> | ||

| * ] (350 |

* ] (350,000 / 183,749*) – due to the existence of former ] | ||

| * |

* Hungary (39,266 / 17,693) | ||

| * |

* Canada (100,000 / 50,860) – 19th – 21st century migrants | ||

| * |

* Serbia (60,000 / 59,021*) ];<small>*excl. the ]</small>] – 18th & 19th century settlers | ||

| * |

* Poland (2002) (47,000 / 2,000*) – ancient minority and due to border shifts during the 20th century | ||

| * |

* Romania (18,000 / 17,199) – ancient minority | ||

| * |

* Ukraine (17,000 / 6,397) ]] – ancient minority and due to the existence of former ] | ||

| * |

* France (13,000 / n.a.) | ||

| * |

* Australia (12,000 / n.a.) – 20th – 21st century migrants | ||

| * |

* Austria (10,234 / 10,234) – 20th – 21st century migrants | ||

| * |

* United Kingdom (10,000 / n.a.) | ||

| * |

* Croatia (5,000 / 4,712) – 18th & 19th century settlers | ||

| * other countries | * other countries | ||

| The number of Slovaks living outside Slovakia in line with the above data was estimated at max. 2 |

The number of Slovaks living outside Slovakia in line with the above data was estimated at max. 2,016,000 in 2001 (2,660,000 in 1991), implying that, in sum, there were max. some 6,630,854 Slovaks in 2001 (7,180,000 in 1991) in the world. The estimate according to the right-hand site chart yields an approximate population of Slovaks living outside Slovakia of 1.5 million. | ||

| Other (much higher) estimates stemming from the Dom zahraničných Slovákov (House of Foreign Slovaks) can be found on ].<ref>{{ |

Other (much higher) estimates stemming from the Dom zahraničných Slovákov (House of Foreign Slovaks) can be found on '']''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sme.sk/c/2422124/Ako-ziju-Slovaci-za-hranicami-Slovensko-mam-rad-ale-mojim-domovom-uz-nie-je.html|title=Ako žijú Slováci za hranicami? Slovensko mám rád, ale mojím domovom už nie je|website=Sme.sk|access-date=2 August 2017|archive-date=3 August 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170803005021/https://www.sme.sk/c/2422124/ako-ziju-slovaci-za-hranicami-slovensko-mam-rad-ale-mojim-domovom-uz-nie-je.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| ==See also== | == See also == | ||

| {{Portal|Slovakia}} | |||

| {{Div col}} | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| {{Reflist|group=note}} | {{Reflist|group=note}} | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| # ] | |||

| # | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| # | |||

| #Baláž, Claude: Slovenská republika a zahraniční Slováci. 2004, Martin | |||

| #Baláž, Claude: (a series of articles in:) Dilemma. 01/1999 – 05/2003 | |||

| ==Sources== | ==Sources== | ||

| * | |||

| *{{cite book |title= Ethnogenesis of Slovaks, Human Affairs, 7, 1997, 1|last= Marsina|first=Richard |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=1997 |publisher=Faculty of Humanities, ] |location= ], ]|isbn= |page= |pages= |url= |accessdate=|ref=harv}} | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927225441/http://www.nepszamlalas.hu/eng/volumes/24/tables/load1_4_1.html |date=27 September 2007 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title= The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe|last= Kamusella |first= Tomasz|authorlink= Tomasz Kamusella|coauthors= |year= 2009|publisher=]|location=], UK (Foreword by Professor ]) |isbn=978023055070 |page= |pages= |url= |accessdate=2009-01-04|ref=harv}} | |||

| *Baláž, Claude: Slovenská republika a zahraniční Slováci. 2004, Martin | |||

| *Baláž, Claude: (a series of articles in:) Dilemma. 01/1999 – 05/2003 | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| {{See also|List of Slavic studies journals}} | |||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| | title = Nové pohľady historickej vedy na slovenské dejiny. I. časť. Najstaršie obdobie slovenských dejín (do prelomu 9.-10. storočia) | |||

| | last = Kirschbaum | |||

| | |

| last = Marsina | ||

| | first = Richard | |||

| | authorlink = http://web.as.uky.edu/ssa/biblio/biblio_kirschbaum.htm | |||

| | year = 1995 | |||

| | title = A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival | |||

| | publisher = |

| publisher = Metodické centrum mesta Bratislavy | ||

| | |

| location= Bratislava | ||

| | |

| language = sk | ||

| | isbn = 978-80-7164-069-1 | |||

| | url = http://us.macmillan.com/ahistoryofslovakia | |||

| }} | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-312-10403-0 | |||

| *{{cite book |title= Ethnogenesis of Slovaks, Human Affairs, 7, 1997, 1|last= Marsina|first=Richard |year=1997 |publisher=Faculty of Humanities, ] |location= ], ]}} | |||

| | page = 25 | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| | ref=harv}} | |||

| | title = Etnogenéza Slovákov | |||

| *{{cite journal|last1=Malyarchuk|first1=B.A.|last2=Perkova|first2=M.A.|last3=Derenko|first3=M.V.|last4=Vanecek|first4=T.|last5=Lazur|first5=J.|last6=Gomolcak|first6=P.|year= 2008|title= Mitochondrial DNA Variability in Slovaks, with Application to the Roma Origin|journal=Annals of Human Genetics|volume=72|page= |pages= 228|publisher= Journal compilation 2008 University College London|location=|doi= 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00410.x|url= http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/119387744/PDFSTART|language= |format=|ref=harv |accessdate=|issue=2 }} | |||

| | editor1-last = Marsina | |||

| | editor1-first = Richard | |||

| | editor2-last = Mulík | |||

| | editor2-first = Peter | |||

| | chapter = K problematike etnogenézy Slovákov a ich pomenovania | |||

| | last = Marsina | |||

| | first = Richard | |||

| | year = 2009 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | location= Martin | |||

| | language = sk | |||

| | isbn = 978-80-7090-940-9 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| | title = Národnosti Uhorska | |||

| | trans-title = Nationalities in the Kingdom of Hungary | |||

| | last = Marek | |||

| | first = Miloš | |||

| | year = 2009 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | location= Trnava | |||

| | language = sk | |||

| | isbn = 978-80-8082-470-9 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | journal = Slovenská Reč | |||

| | title = Najstarší výskyt slova slovenský z roku 1294 | |||

| | last = Uličný | |||

| | first = Ferdinand | |||

| | year = 1986 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | publisher = Slovak Academic Press | |||

| | location= Bratislava | |||

| | language = sk | |||

| | url = http://www.juls.savba.sk/ediela/sr/1986/2/sr1986-2-lq.pdf | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | journal = Slovenská Reč | |||

| | title = Osídlenie Liptova a dolnoliptovské nárečia | |||

| | last = Uhlár | |||

| | first = Vlado | |||

| | year = 1992 | |||

| | publisher = Slovak Academic Press | |||

| | location= Bratislava | |||

| | language = sk | |||

| | url = http://www.juls.savba.sk/ediela/sr/1992/6/sr1992-6-lq.pdf | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title= The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe|last= Kamusella |first= Tomasz|author-link= Tomasz Kamusella|year= 2009|publisher=]|location=], UK (Foreword by Professor ]) |isbn=9780230550704 }} | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| |last = Kirschbaum | |||

| |first = Stanislav J. | |||

| |title = A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival | |||

| |publisher = ]; ] | |||

| |date = March 1995 | |||

| |location = New York | |||

| |url = http://us.macmillan.com/ahistoryofslovakia | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-312-10403-0 | |||

| |page = 25 | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080925041206/http://us.macmillan.com/ahistoryofslovakia | |||

| |archive-date = 2008-09-25 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book | *{{cite book | ||

| |last = Eberhardt | |last = Eberhardt | ||

| |first = Piotr | |first = Piotr | ||

| |authorlink = | |||

| |title = Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis | |title = Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis | ||

| |publisher = M.E. Sharpe | |publisher = M.E. Sharpe | ||

| |series = | |||

| |year = 2003 | |year = 2003 | ||

| |doi = | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-7656-0665-5 | |isbn = 978-0-7656-0665-5 | ||

| |

}} | ||

| *{{cite book |title=Slovakia and the Slovaks |last= Mikuš|first=Joseph A. |

*{{cite book |title=Slovakia and the Slovaks |last= Mikuš|first=Joseph A.|year=1977 |publisher=Three Continents Press |isbn= 9780914478881|quote=The work is superbly illustrated by Martin Benka, a Slovak painter of comparable}} | ||

| == Maps == | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| Image:Vojvodina west east slavs.png|Slovaks in Vojvodina, Serbia (2002 census) | |||

| File:Slovak USC2000 PHS.svg|The language spread of Slovak in the United States according to U. S. Census 2000 and other resources interpreted by research of U. S. English Foundation, percentage of home speakers | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{commons category|Slovaks}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Americana Poster}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| {{Slovakia topics}} | |||

| {{Slavic ethnic groups}} | {{Slavic ethnic groups}} | ||

| {{commons category|Slovaks}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:35, 6 January 2025

West Slavic ethnic group For information on the population of Slovakia, see Demographics of Slovakia.| Parts of this article (those related to Statistics) need to be updated. The reason given is: Data present are from the early 1990s. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (August 2024) |

Ethnic group

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 6–7 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 416,047 (2022); 750,000 (estimate) | |

| 162,578 (2021 census); 200,000–400,000 (estimates) | |

| 68,210; (including 14,910 first generation immigrants); 100,000 (estimate) | |

| 64,745; 80,000 (estimate) | |

| 63,621 (2020); 65,000 (estimate) | |

| 58,000; 135,000 (estimate) | |

| 41,730 (2021); 40,000 (estimate) | |

| 29,794 (2021); 75,000 (estimate) | |

| 20,581 (2021); 25,000 (estimate) | |

| 17,200 | |

| 17,000 (estimated total in Scandinavian countries) | |

| 12,350 (2021); 15,000(estimate) | |

| 10,801; 15,000 (estimate) | |

| 10,300 (2021 census) 13,000 (estimate) | |

| 9,768 (2017); 20,000 (estimate) | |

| 9,014 (2021); 20,000 (estimates) | |

| 9,000 (2022); 15,000 (estimate) | |

| 8,000 (2020); up to 70,000 (estimate) | |

| 6,677 (2022 census); 10,000 (estimate) | |

| 6,700 (estimate) | |

| 4,781 (2021 census), 9,000-15,000 (estimates) | |

| 3,688 (2021 census); 5,000 (estimate) | |

| Languages | |

| Slovak | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Roman Catholics with Minorities of Lutherans, Eastern Catholics, other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pannonian Rusyns, other West Slavs | |

The Slovaks (Slovak: Slováci [ˈsɫɔvaːt͡si], singular: Slovák [ˈslɔvaːk], feminine: Slovenka [ˈsɫɔvɛŋka], plural: Slovenky) are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak the Slovak language.

In Slovakia, c. 4.4 million are ethnic Slovaks of 5.4 million total population. There are Slovak minorities in many neighboring countries including Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia and Ukraine and sizeable populations of immigrants and their descendants in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, United Kingdom and the United States among others, which are collectively referred to as the Slovak diaspora.

Name

The name Slovak is derived from *Slověninъ, plural *Slověně, the old name of the Slavs (Proglas, around 863). The original stem has been preserved in all Slovak words except the masculine noun; the feminine noun is Slovenka, the adjective is slovenský, the language is slovenčina and the country is Slovensko. The first written mention of adjective slovenský (Slovak) is in 1294 (ad parvam arborem nystra slowenski breza ubi est meta).

The original name of Slovaks Slověninъ/Slověně was still recorded in Pressburg Latin-Czech Dictionary (the 14th century), but it changed to Slovák under the influence of Czech and Polish (around 1400). The first written mention of new form in the territory of present-day Slovakia is from Bardejov (1444, "Nicoulaus Cossibor hauptman, Nicolaus Czech et Slowak, stipendiarii supremi"). The mentions in Czech sources are older (1375 and 1385). The change is not related to the ethnogenesis of Slovaks, but exclusively to linguistic changes in the West Slavic languages. The word Slovak was used also later as a common name for all Slavs in Czech, Polish, and also Slovak together with other forms.

In Hungarian, "Slovak" is Tót (pl: tótok), an exonym. It was originally used to refer to all Slavs including Slovenes and Croats, but eventually came to refer primarily to Slovaks. Many place names in Hungary such as Tótszentgyörgy, Tótszentmárton, and Tótkomlós still bear the name. Tóth is a common Hungarian surname.

The Slovaks have also historically been variously referred to as Slovyenyn, Slowyenyny, Sclavus, Sclavi, Slavus, Slavi, Winde, Wende, or Wenden. The final three terms are variations of the Germanic term Wends, which was historically used to refer to any Slavs living close to Germanic settlements.

Ethnogenesis

The early Slavs came to the territory of Slovakia in several waves from the 5th and 6th centuries and were organized on a tribal level. Original tribal names are not known due to the lack of written sources before their integration into higher political units. Weakening of tribal consciousness was probably accelerated by Avars, who did not respect tribal differences in the controlled territory and motivated remaining Slavs to join together and to collaborate on their defense. In the 7th century, Slavs founded a larger tribal union: Samo's empire. Regardless of Samo's empire, the integration process continued in other territories with various intensities.

The final fall of the Avar Khaganate allowed new political entities to arise. The first such political unit documented by written sources is the Principality of Nitra, one of the foundations of later common ethnic consciousness. At this stage in history it is not yet possible to assume a common identity of all ancestors of Slovaks in the neighboring eastern territories, even if it was inhabited by closely related Slavs. The Principality of Nitra became a part of Great Moravia, a common state of Moravians (Czech ancestors were joined only for a few years). The relatively short existence of Great Moravia prevented it from suppressing differences which resulted from its creation from two separate entities, and therefore a common "Slovak-Moravian" ethnic identity failed to develop. The early political integration in the territory of present-day Slovakia was, however, reflected in linguistic integration. While dialects of the early ancestors of Slovaks were divided into West Slavic (western and eastern Slovakia) and non-West Slavic (central Slovakia), between the 8th and 9th centuries both dialects merged, thus laying the foundations of a later Slovak language.

The 10th century is a milestone in the Slovak ethnogenesis. The fall of Great Moravia and further political changes supported their formation into a separate nation. At the same time, with the extinction of the Proto-Slavic language, between the 10th and 13th centuries Slovak evolved into an independent language (simultaneously with other Slavic languages). The early existence of the Kingdom of Hungary positively influenced the development of common consciousness and companionship among Slavs in the Northern Hungary, not only within boundaries of present-day Slovakia. The clear difference between Slovaks and Hungarians made adoption of a specific name unnecessary and Slovaks preserved their original name (in Latin e.g. Slavus), which was also used in communication with other Slavic peoples (Polonus, Bohemus, Ruthenus). In political terms, the medieval Slovaks were a part of the multi-ethnic political nation Natio Hungarica, together with Hungarians (or, more exactly, Magyars), Slavonians, Germans, Romanians and other ethnic groups in the Kingdom of Hungary. Since a medieval political nation did not consist of ordinary people but nobility, membership of the privileged class was necessary for all these peoples (nobiles Hungary).