| Revision as of 19:53, 2 April 2012 editAuthorityTam (talk | contribs)3,283 edits →Jehovah's Witnesses: Simplify. Discussion of Luke 23:43 can occur at that article or perhaps JW salvation or JW beliefs.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:58, 10 January 2025 edit undoWikieditor662 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users595 edits Removed "not to be confused with heaven" | ||

| (487 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Place of exceptional happiness, delight, and bliss}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | {{Other uses}} | ||

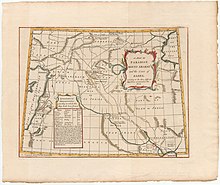

| ] |

] depicting people in paradise]] | ||

| In ] and ], '''paradise''' is a place of everlasting happiness, delight, and bliss.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Paradise {{!}} religion|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/paradise-religion|access-date=2021-01-14|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en}}</ref> Paradisiacal notions are often laden with ] imagery, and may be ], ], or both, often contrasted with the miseries of human civilization: in paradise there is only peace, prosperity, and happiness. Paradise is a place of contentment, a land of luxury and fulfillment containing ever-lasting bliss and delight. Paradise is often described as a "higher place", the holiest place, in contrast to ], or ]s such as ]. | |||

| In eschatological contexts, paradise is imagined as an ]. In ], ], and ], ] is a paradisiacal belief. In ] and ], paradise and ] are synonymous, with higher levels available to beings who have achieved special attainments of virtue and meditation. In old Egyptian beliefs, the underworld is ], the reed-fields of ideal hunting and fishing grounds where the dead lived after judgment. For the Celts, it was the ] of ]. For the classical Greeks, the ] was a paradisiacal land of plenty where adherents hoped the heroic and righteous dead would spend ]. In the Zoroastrian ], the "Best Existence"<!-- vahišta.ahu- --> and the "House of Song"<!-- garō.dəmāma- --> are places of the righteous dead. On the other hand, in ] contexts 'paradise' describes the world before it was tainted by ]. | |||

| '''Paradise''' (]: ''pairidaeza'') and (Modern ]: ''pardis'') is a place in which existence is positive, harmonious and timeless. It is conceptually a counter-image of the miseries of human ], and in paradise there is only ], ], and ]. Paradise is a place of contentment, but it is not necessarily a land of luxury and idleness. It is often used in the same context as that of ]. | |||

| The concept is a theme in art and literature, particularly of the pre-] era. ]'s '']'' is an example of such usage. | |||

| Paradisaical notions are cross-cultural, often laden with ] imagery, and may be ] or ] or both. In eschatological contexts, paradise is imagined as an ]. In Christian and Islamic understanding, ] is a paradisaical relief, evident for example in the ] when ] tells a ] crucified alongside him that they will be together in paradise. In old Egyptian beliefs, the other-world is ], the reed-fields of ideal hunting and fishing grounds where the dead lived after judgment. For the Celts, it was the ] of ]. For the classical Greeks, the ] was a paradisaical land of plenty where the heroic and righteous dead hoped to spend eternity. The ] held that the physical body was destroyed by fire but recreated and reunited in the ] in a state of bliss. In the Zoroastrian ], the "Best Existence"<!-- vahišta.ahu- --> and the "House of Song"<!-- garō.dəmāma- --> are places of the righteous dead. On the other hand, in ] contexts 'paradise' describes the world before it was tainted by ]. So for example, the ] associate paradise with the ], that is, the perfect state of the world prior to the fall from grace, and the perfect state that will be restored in the ]. | |||

| ==Etymology and concept history== | |||

| The concept is a topos' in art and literature, particularly of the pre-], a well-known representative of which is ]'s '']''. A paradise should not be confused with a ], which is an alternative society. | |||

| ] king ] (ruled 668–631 BCE) at ], with original color reconstitution. Irrigation canals radiate from an aqueduct. The king appears under the porch. ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Wall panel; relief British Museum |url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1856-0909-36_1 |website=The British Museum |language=en}}</ref><ref> in 2018 temporary exhibit "]"</ref>]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The word "paradise" entered English from the ] ''paradis'', inherited from the ] ''paradisus'', from ] ''parádeisos'' (παράδεισος), from an ] form, from ]''*parādaiĵah-'' "walled enclosure", whence ] 𐎱𐎼𐎭𐎹𐎭𐎠𐎶 ''p-r-d-y-d-a-m /paridaidam/'', ] ] ''pairi-daêza-''.<ref name="RSC">{{cite book |last1=Charnock |first1=Richard Stephen |title=Local Etymology: A Derivative Dictionary of Geographical Names |year=1859 |publisher=Houlston and Wright |page=201 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s1OpF1IdcgQC&pg=PA201 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="etymonline.com">{{cite web |title=Paradise: Origin and meaning of paradise by Online Etymology Dictionary |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/paradise |website=www.etymonline.com |language=en}}</ref> The literal meaning of this Eastern Old Iranian language word is "walled (enclosure)",<ref name="New Oxford"/> from ''pairi-'' 'around' (cognate with Greek ], English peri- of identical meaning) and ''-diz'' "to make, form (a wall), build" (cognate with Greek ] 'wall').<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=paradise |title= Online Etymology Dictionary |access-date=2 October 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20141006065930/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=paradise |archive-date=6 October 2014 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://dictionary.obspm.fr/index.php?showAll=1&&search=&&formSearchTextfield=form&&page=1 |title=An Etymological Dictionary of Astronomy and Astrophysics |access-date=15 January 2015 |url-status=live |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150115095513/http://dictionary.obspm.fr/index.php?showAll=1&&search=&&formSearchTextfield=form&&page=1 |archive-date=2015-01-15}}</ref> The word's etymology is ultimately derived from a ] ''*dheigʷ'' "to stick and set up (a wall)", and ''*per'' "around".<ref name="etymonline.com"/><ref name="New Oxford">'']''</ref><ref>], ''Etymological Dictionary of Greek'', Brill, 2009, p. 1151.</ref> | |||

| ], circa 1620]] | |||

| By the 6th/5th century BCE, the Old Iranian word had been borrowed into ] ''pardesu'' "domain". It subsequently came to indicate the expansive ] of the ], and was subsequently borrowed into Greek as παράδεισος ''parádeisos'' "park for animals" in the '']'' of the early 4th century BCE Athenian ], ] as ''pardaysa'' "royal park", and ] as ], "orchard" (appearing thrice in the ]; in the ] ({{bibleverse|Song|of Songs 4:13}}), ] ({{bibleverse|Ecclesiastes|2:5}}) and ] ({{bibleverse|Nehemiah|2:8}})). In the ] (3rd–1st centuries BCE), Greek παράδεισος ''parádeisos'' was used to translate both Hebrew פרדס ''pardes'' and Hebrew גן ''{{lang|he-Latn|gan}}'', "garden" (e.g. ({{bibleverse|Genesis|2:8}}, {{bibleverse|Ezekiel|28:13}}): it is from this usage that the use of "paradise" to refer to the ] derives. The same usage also appears in ] and in the ] as '']'' فردوس.<ref name="RSC"/> | |||

| The idea of a walled enclosure was not preserved in most Iranian usage, and generally came to refer to a plantation or other cultivated area, not necessarily walled. For example, the Old Iranian word survives as ''Pardis'' in New Persian as well as its derivative ''pālīz'' (or "jālīz"), which denotes a vegetable patch. | |||

| ==Etymology and semasiology== | |||

| ], Four seasons of paradise. 1660-64]] | |||

| ==Biblical== | |||

| The word "paradise" entered English from the ] ''paradis'', inherited from the ] ''paradisus'', from ] ''parádeisos'' (''παράδεισος''), and ultimately from an ] root, attested in ] as ''pairi.daêza-''.<ref name="New Oxford">New Oxford American dictionary</ref> The literal meaning of this Eastern Old Iranian language word is "walled (enclosure)",<ref name="New Oxford"/> from ''pairi-'' "around" + ''-diz'' "to create, make". The word is not attested in other Old Iranian languages (these may however be hypothetically reconstructed, for example as ] ''*paridayda-''). | |||

| ===Hebrew Bible=== | |||

| By the 6th/5th century BCE, the Old Iranian word had been adopted as ] ''pardesu'' and ] ''partetas'' "domain". It subsequently came to indicate walled estates, especially the carefully tended royal parks and ]s. The term eventually appeared in Greek as ''parádeisos'' "park for animals" in the '']'' of the early 4th century BCE Athenian gentleman-scholar ]. ] ''pardaysa'' similarly reflects "royal park". | |||

| ], ''Four seasons of paradise'', 1660–1664]] | |||

| The Hebrew word ''pardes'' appears only in the post-Exilic period (after 538 BCE); it occurs in the ] 4:13, ] 2:5, and ] 2:8, in each case meaning "park" or "garden", the original Persian meaning of the word, where it describes the royal parks of ] by ] in ]. | |||

| In ] era Judaism, "paradise" came to be associated with the ] and ], and transferred to ]. | |||

| Hebrew ''pardes'' appears thrice in the ]; in the ] 4:13, ] 2:5 and ] 2:8. In those contexts it could be interpreted as a park, a garden or an orchard. In the 3rd-1st century BCE '']'', Greek ''parádeisos'' was used to translate both Hebrew ''pardes'' and Hebrew ''{{lang|he-Latn|gan}}'', "garden": it is from this usage that the use of "paradise" to refer to the ] derives. This usage also appears in ] and the ] itself as ''firdaws''. | |||

| In the apocryphal ], ] are expelled from paradise (rather than Eden) after the ], having been tricked by the ]. After the death of Adam, the ] carries Adam's body to be buried in Paradise, in the ]. | |||

| The idea of a walled enclosure was not preserved in most Iranian usage, and generally came to refer to a plantation or other cultivated area, not necessarily walled. For example, the Old Iranian word survives in New Persian ''pālīz'' (or "jālīz"), which denotes a vegetable patch. However, the word ], as well as the similar complex of words that have the same ] root: ], ], ], ], ], etc., all refer simply to a deliberately ''enclosed'' area, but not necessarily an area enclosed by walls. | |||

| ===New Testament=== | |||

| For the connection between these ideas and that of the city, compare German ] ("fence"), English ] and Dutch ] ("garden"), or ] with Nordic ] and Slavic ] (both "city"). | |||

| The Greek word ''παράδεισος'' appears three times in the ]: | |||

| ==Religious use== | |||

| * Luke 23:43 – by Jesus on the ], in response to the thief's request that Jesus remember him when he came into his kingdom. | |||

| ===Judaism=== | |||

| * 2 Cor. 12:4 – in Paul's description of a ] paradise. | |||

| The word ''pardes'', borrowed from the Persian word, does not appear before the post-Exilic period (post-538 BCE); it occurs in the ] 4:13, ] 2:5, and ] 2:8, in each case meaning "park" or "garden", the original Persian meaning of the word, where it describes to the royal parks of ] by ] in ]. | |||

| * Rev. 2:7 – alluding to the ] mentioned at Gen.2:8. | |||

| ==Judaism== | |||

| Later in ] era Judaism "paradise" came to be associated with the ] and ], and transferred to ]. The ] uses the word around 30 times, both of Eden, (Gen.2:7 etc.) and of Eden restored (Ezek. 28:13, 36:35) etc. In the ], ] are expelled from paradise (instead of Eden) after having been tricked by the serpent. Later after the death of Adam, the ] carries the body of Adam to be buried in Paradise, which is in the ]. | |||

| {{See also|Paradise in Judaism}} | |||

| According to ],<ref name="Eshatology"> – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.</ref> the higher ] is called the "Garden of Righteousness". It has been created since the beginning of the world, and will appear gloriously at the end of time. The righteous dwelling there will enjoy the sight of the heavenly '']'' carrying the throne of God. Each of the righteous will walk with God, who will lead them in a dance. Its Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants are "clothed with garments of light and eternal life, and eat of the tree of life" (Enoch 58,3) near to God and His anointed ones.<ref name="Eshatology"/> This Jewish rabbinical concept of a higher Gan Eden is opposed by the Hebrew terms '']'' (the source, via ], of the English "Gehenna")<ref>], '']'', © 1968; ] edition, 1970, p. 127:<br/>"Gehenna... Hebrew: ''Gehinom'': 'Hell.' Literally: the Valley (''gay'') of Hinnom"</ref> and '']'', figurative names for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism, a place envisioned as being at the greatest possible distance from ]. | |||

| ===Rabbinic Judaism=== | |||

| Later in ] the word 'Pardes' recurs, but less often in the Second Temple context of Eden or restored Eden. Tosefta ]14b uses the word of the veil around mystic philosophy.<ref></ref> | |||

| In modern Jewish eschatology it is believed that history will complete itself and the ultimate destination will be when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.<ref>{{cite web|title=End of Days|date=11 January 2000|url=http://www.aish.com/ci/a/48925077.html|publisher=Aish|access-date=1 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| In the ] and the Jewish ],<ref name="Gan Eden"> – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.</ref> the scholars agree that there are two types of spiritual places called "Garden in Eden". The first is rather terrestrial, of abundant fertility and luxuriant vegetation, known as the "lower Gan Eden". The second is envisioned as being celestial, the habitation of righteous, Jewish and non-Jewish, immortal souls, known as the "higher Gan Eden". The ]s differentiate between ''Gan'' and Eden. Adam is said to have dwelt only in the ''Gan'', whereas Eden is said never to be witnessed by any mortal eye.<ref name="Gan Eden"/> In ], the word 'Pardes' recurs, but less often in the Second Temple context of Eden or restored Eden. A well-known reference is in the ], where the word may allude to mystic philosophy.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=65&letter=P#ixzz0ZWg2S0OP|title=JewishEncyclopedia.com|access-date=2 October 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111013054031/http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=65&letter=P#ixzz0ZWg2S0OP|archive-date=13 October 2011}}</ref> | |||

| The ] gives the word a mystical interpretation, and associates it with the four kinds of Biblical exegesis: ''peshat'' (literal meaning), ''remez'' (allusion), ''derash'' (anagogical), and ''sod'' (mystic). The initial letters of those four words then form {{lang|he|פָּרְדֵּס}} – '']'', which was in turn felt to represent the fourfold interpretation of the ] (in which ''sod'' – the mystical interpretation – ranks highest). | |||

| The ] gives the word a mystical interpretation, and associates it with the four kinds of Biblical exegesis: ''peshat'' (literal meaning), ''remez'' (allusion), ''derash'' (anagogical), and ''sod'' (mystic). The initial letters of those four words then form {{lang|he|פַּרְדֵּס}} – '']'', which was in turn felt to represent the fourfold interpretation of the ] (in which ''sod'' – the mystical interpretation – ranks highest). | |||

| ===Christianity=== | |||

| {{seealso|World to Come}} | |||

| ==Christianity== | |||

| The New Testament use and understanding of paradise parallels that of contemporary Judaism. The word is used three times in the New testament writings: | |||

| {{See also|World to Come|Kingship and kingdom of God|Hades in Christianity}} | |||

| * Luke 23:43 - by Jesus on the ], in response to the thief's request that Jesus remember him when he came in his kingdom. | |||

| * 2 Cor.12:4 - in Paul's description of a man's description of a ] paradise, which may in fact be a vision Paul himself saw. | |||

| * Rev.2:7 - in a reference to the Gen.2:8 paradise and the ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In the 2nd century AD, ] distinguished paradise from heaven. In '']'', he wrote that only those deemed worthy would inherit a home in heaven, while others would enjoy paradise, and the rest live in the ] (which was mostly a ruin after the ] but was rebuilt beginning with ]). ] likewise distinguished paradise from heaven, describing paradise as the earthly "school" for souls of the righteous dead, preparing them for their ascent through the celestial spheres to heaven.<ref>, newadvent.org</ref> | |||

| ] in paradise, ], Serbia]] | |||

| In the 2nd century AD, ] distinguished paradise from ]. In '']'', he wrote that only those deemed worthy would inherit a home in heaven, while others would enjoy paradise, and the rest live in the ] (which was mostly a ruin after the ] but was rebuilt beginning with ] in the 4th century). ] likewise distinguished paradise from heaven, describing paradise as the earthly "school" for souls of the righteous dead, preparing them for their ascent through the celestial spheres to heaven.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080720032710/http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/04122.htm |date=2008-07-20 }}, newadvent.org</ref> | |||

| Many early Christians identified ] with paradise, where the souls of the righteous go until the ]; others were inconsistent in their identification of paradise, such as St. Augustine, whose views varied.<ref name="Delumeau1995">{{cite book|author=Jean Delumeau|title=History of paradise|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ubJDLvEV0vEC&pg=PA29|access-date=3 April 2013|year=1995|publisher=University of Illinois Press|isbn=978-0-252-06880-5|pages=29–}}</ref> | |||

| Tension between these two competing Christian views of paradise may be responsible for a textual difference in one of the three New Testament verses using the word, Luke 23:43. For example the two early ] versions translate Luke 23:43 differently. The ] read "Today I tell you that you will be with me in paradise", whereas the ] reads "I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise". Likewise the two earliest Greek codices with punctuation disagree: ] has a pause mark in the original ink after 'today', whereas ] has the "today in paradise" reading. Today almost all translations follow the "today in Paradise", although there is some support among classical Greek scholars for the reading "today that"<ref></ref> | |||

| In Luke 23:43, Jesus has a conversation with one of those crucified with him, who asks, "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom". Jesus answers him, "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+23&version=NIV|title=Luke 23|work=Bible Gateway|access-date=2 October 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170719035039/https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+23&version=NIV|archive-date=19 July 2017}}</ref> This has often been interpreted to mean that on that same day the thief and Jesus would enter the intermediate resting place of the dead who were waiting for the Resurrection.<ref name="Zwiep1997">{{cite book|author=A. W. Zwiep|title=The Ascension of the Messiah in Lukan Christology /|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QIW7JywiBhIC&pg=PA150|access-date=3 April 2013|year=1997|publisher=BRILL|isbn=978-90-04-10897-4|pages=150–}}</ref> Divergent views on paradise, and when one enters it, may have been responsible for a punctuation difference in Luke; for example, the two early ] versions translate Luke 23:43 differently. The ] read "Today I tell you that you will be with me in paradise", whereas the ] reads "I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise". Likewise the two earliest Greek codices with punctuation disagree: ] has a pause mark (a single dot on the baseline) in the original ink equidistant between 'today' and the following word (with no later corrections and no dot before "today"<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ministrymagazine.org/archive/2013/06/the-significance-of-a-comma:-an-analysis-of-luke-23:43|title=The Significance of a Comma: An Analysis of Luke 23:43 – Ministry Magazine|website=Ministry Magazine|access-date=8 May 2018|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417154457/https://www.ministrymagazine.org/archive/2013/06/the-significance-of-a-comma:-an-analysis-of-luke-23:43|archive-date=17 April 2017}}</ref>), whereas ] has the "today in paradise" reading. In addition, an adverb of time is never used in the nearly 100 other places in the Gospels where Jesus uses the phrase, "Truly I say to you".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.forananswer.org/Luke/Luke23_43.htm|title=For an Answer: Christian Apologetics – Luke 23:43|website=www.forananswer.org|access-date=8 May 2018|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170418182314/http://www.forananswer.org/Luke/Luke23_43.htm|archive-date=18 April 2017}}</ref> | |||

| In Christian art ]'s '']'' painting shows Paradise on its left side. There is a ] (and another tree) and a ] of liberated ]s. In the middle is a hole. In Muslim art it similarly indicates the presence of the Prophet or divine beings. It visually says, 'Those here cannot be depicted.' | |||

| In Christian art, ]'s '']'' painting shows Paradise on its left side. There is a ] (and another tree) and a ] of liberated ]. In the middle is a hole. In Muslim art it similarly indicates the presence of the Prophet or divine beings. It visually says, "Those here cannot be depicted". | |||

| ====Slavic Christianity==== | |||

| {{main|Rai (paradise)}} | |||

| Slavic languages, and Romanian which is not Slavic but Slavic-influenced, have a distinct term for "paradise", "raj" (read "rai") which is generally agreed to derive from Persian ''ray'' and co-exists alongside terms deriving from the Persian word ''pardeis''. | |||

| ===Jehovah's Witnesses=== | |||

| {{See also|Jehovah's Witnesses and salvation}} | {{See also|Jehovah's Witnesses and salvation}} | ||

| ] believe, from their interpretation of the ], that God's original purpose was, and is, to have the earth filled with the offspring of ] as caretakers of a global paradise. However, Adam and ] rebelled against God's sovereignty and were banished from the Garden of Eden, driven out of paradise into toil and misery. | |||

| ] believe that God's purpose from the start, was and is, to have the earth filled with the offspring of ] as caretakers of a global paradise. After God had magnificently designed this earth for human habitation, however, Adam and Eve rebelled against ] and so they were banished from the Garden of Eden, or Paradise. Jehovah's Witnesses also believe that the wicked people will be destroyed at ] and that many of the righteous (those faithful and obedient to Jehovah) will live eternally in an earthly Paradise. (Psalms 37:9, 10, 29; Prov. 2:21, 22). Joining the survivors will be resurrected righteous and unrighteous people who died prior to Armageddon (John 5:28, 29; Acts 24:15). The latter are brought back because they paid for their sins by their death, and/or also because they lacked opportunity to learn of Jehovah's requirements prior to dying (Rom. 6:23). These will be judged on the basis of their post-resurrection obedience to instructions revealed in new "scrolls" (Rev. 20:12). This provision does not apply to those that Jehovah deems to have sinned against his holy spirit (Matt. 12:31, Luke 12:5).<ref>''What Does the Bible Really Teach?'' (Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, 2005), Chapter 7</ref><ref>''Insight on the Scriptures'' (Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, 1988), 783-92</ref> | |||

| Jehovah's Witnesses believe that disobedient and wicked people will be destroyed by Christ at ] and those obedient to Christ will live eternally in a restored earthly paradise. Joining the survivors will be the resurrected righteous and unrighteous people who died prior to Armageddon. The latter are brought back because they paid for their sins by their death and/or because they lacked opportunity to learn of Jehovah's requirements before dying. These will be judged on the basis of their post-resurrection obedience to instructions revealed in new "scrolls". They believe that resurrection of the dead to paradise earth is made possible by ] and the ]. This provision does not apply to those whom Christ as Judge deems to have sinned against God's holy spirit.<ref>''What Does the Bible Really Teach?'' (Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, 2005), Chapter 7</ref><ref>''Insight on the Scriptures'' (Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, 1988), 783–92</ref> | |||

| One of ] were the words to an evildoer hanging alongside him on a torture stake: “You will be with me in Paradise.”—Luke 23:43. <!--Notice the placement of the comma is after the word 'today', indicating that there are two separate phrases, 1. 'I tell you today' and 2. 'You will be with me in Paradise'. This distinction differs from other Christian understanding of this verse where they read it as 1. 'I tell you' and 2. 'Today you will be with me in Paradise'. Some scriptures that Jehovah's Witnesses use to support their belief are (John 3:13-15); (Acts 24:15). -->Witnesses believe Scriptures such as and and and show that Jesus himself expected an interval of three days between his own death and resurrection, making impossible a reunion in Paradise on the same day as Jesus' ''"you will be with me in Paradise"'' statement.<ref>"Meeting the Challenge of Bible Translation", ''The Watchtower'', June 15, 1974, page 362-363</ref> | |||

| One of ] were the words to a man hanging alongside him, "you will be with me in Paradise."<ref>{{bibleverse|Luke|23:43}}</ref> The ] places a comma after the word 'today', dividing it into two separate phrases, "I tell you today" and "you will be with me in Paradise". This differs from standard translations of this verse as "I tell you today you will be with me in Paradise".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://biblehub.com/luke/23-43.htm|title=Luke 23:43|access-date=2 October 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/20141003144036/http://biblehub.com/luke/23-43.htm|archive-date=3 October 2014}}</ref> Based on scriptures such as , , and , Witnesses believe Jesus' expectation that he would be bodily resurrected after three days precluded his being in paradise on the same day that he died.<ref>"Meeting the Challenge of Bible Translation", ''The Watchtower'', June 15, 1974, page 362–363</ref> | |||

| ====Mormonism==== | |||

| In ] theology, paradise usually refers to the ]. That is, the place where spirits dwell following death and awaiting the resurrection. In that context, "paradise" is the state of the righteous after death. In contrast, the wicked and those who have not yet learned the gospel of Jesus Christ await the resurrection in ]. After the universal resurrection, all persons will be assigned to a particular ]. This may also be termed "paradise". | |||

| === |

===Mormonism=== | ||

| In ] theology, paradise usually refers to the ], the place where spirits dwell following death and awaiting the resurrection. In that context, "paradise" is the state of the righteous after death.<ref>Duane S. Crowther – Chapter 5 – Paradise of the Wicked – Retrieved 8 July 2014.</ref> In contrast, the wicked and those who have not yet learned the gospel of Jesus Christ await the resurrection in ]. After the universal resurrection, all persons will be assigned to a particular ]. This may also be termed "paradise". | |||

| ==Islam== | |||

| {{Main|Jannah}} | {{Main|Jannah}} | ||

| ] (upper right) visiting Paradise while riding ], accompanied by the angel ] (upper left)]] | |||

| In the ], Paradise is denoted as ''jannah'' (garden), with the highest level being called ''firdaus''. The etymologically equivalent word is derived from the original ] counterpart, and used instead of Heaven to describe the ultimate pleasurable place after death, accessible by those who pray, donate to charity, read the Qur'an, believe in: God, the angels, his revealed books, his prophets and messengers, the Day of Judgement and the afterlife, and follow God's will in their life. Heaven in Islam is used to describe the ]. It is also used in the Qur'an to describe skies in the literal sense, i.e., above earth. In Islam, the bounties and beauty of Heaven are immense, so much so that they are beyond the abilities of mankind’s worldly mind to comprehend. | |||

| In the ], Heaven is denoted as ''Jannah'' (garden), with the highest level being called ''Firdaus'', i.e. Paradise. It is used instead of Heaven to describe the ultimate pleasurable place after death, accessible by those who pray, donate to charity, and believe in: ], the ], his ], his ], the ] and divine decree (]), and follow God's will in their life. Heaven in Islam is used to describe skies in the literal sense and metaphorically to refer to the ]. In Islam, the bounties and beauty of Heaven are immense, so much so that they are beyond the abilities of mankind's worldly mind to comprehend. | |||

| There are eight doors of Jannah. These are eight grades of Jannah: | |||

| * 1. Jannah al-Mawa | |||

| * 2. Dar al-Maqam | |||

| * 3. Dar al-Salam | |||

| * 4. Dar al-Khuld | |||

| * 5. Jannah al-Adn | |||

| * 6. Jannah al-Na'im | |||

| * 7. Jannah al-Kasif | |||

| * 8. Jannah al-Firdaus | |||

| Jannah al-Mawa is in the lowest, Jannah al-Adn is the middle and Jannah al-Firdaus is the highest. | |||

| Imam Bukhari has also recorded the tradition in which the Prophet said, | |||

| ===The Urantia Book=== | |||

| ] portrays Paradise as the "] center of the universe of universes," and as "the abiding place of the ], the ], the ], and their ] co-ordinates and associates." The book states that paradise is the primal origin and the final ] for all spirit personalities, and for all the ascending creatures of the ] worlds of ] and ].<ref>http://www.urantia.org/en/urantia-book-standardized/paper-11-eternal-isle-paradise</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|'When you ask from ], ask Him for Al-Firdaus, for it is the middle of Paradise and it is the highest place and from it the ] flow.' (Bukhari, Ahmad, Baihaqi)}} | |||

| In this tradition, it is evident that Al-Firdaus is the highest place in Paradise, yet, it is stated that it is in the middle. While giving an explanation of this description of Al-Firdaus, the great scholar, Ibn Hibban states, | |||

| {{Blockquote|'Al-Firdaus being in the middle of Paradise means that with respect to the width and breadth of Paradise, Al-Firdaus is in the middle. And with respect to being 'the highest place in Paradise', it refers to it being on a height.'}} | |||

| This explanation is in agreement to the explanation which has been given by Abu Hurairah (r.a.) who said that | |||

| {{Blockquote|'Al Firdaus is a mountain in Paradise from which the rivers flow.' (Tafseer Al Qurtubi Vol. 12 pg. 100)}} | |||

| The Quran also gave a warning that not all Muslims or even the believers will assuredly be permitted to enter Jannah except those who had struggled in the name of God and tested from God's trials as faced by the messengers of God or ancient prophets: | |||

| <blockquote>''Or do you think that you will enter Paradise while such has not yet come to you as came to those who passed on before you? They were touched by poverty and hardship and were shaken until messenger and those who believed with him said,"When is the help of Allah ?" Unquestionably, the help of Allah is near.'' <br/>— </blockquote>Other instances where paradise is mentioned in the Qur'an includes descriptions of springs, silk garments, embellished carpets and women with beautiful eyes.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Fairchild |first=Ruggles |title=Islamic Gardens and Landscapes |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2008 |location=Pennsylvania |pages=89 |language=English}}</ref> These elements can also be seen as depicted within Islamic art and architecture. <blockquote>"''The semblance of Paradise (Jannah) promised the pious and devout (is that of a garden) with streams of water that will not go rank, and rivers of milk whose taste will not undergo a change, and rivers of wine delectable to drinkers, and streams of purified honey, and fruits of every kind in them, and forgiveness from their Lord."'' (47:15).<ref name=":0" /></blockquote> | |||

| === References to Paradise (Jannah) in the Qur'an as reflected in Islamic art === | |||

| The Qur'an contains multiple passages in which paradise, or 'Jannah', is referred to. The Holy Book contains 166 references to gardens, of which nineteen mention 'Jannah', connoting both images of paradise through gardens, water features, and fruit-bearing trees.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Mehdi |first=Aqsa |date=2021 |title=A Comparative Study Between the Qur'an's Vision of Paradise and the Mughal Islamic Gardens of Lahore |url=http://www.adjournal.net/articles/93/931.pdf |journal=Online Journal of Art and Design |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=7 |via=Adjournal}}</ref> Scholars are unable to confirm that certain artistic choices were solely intended to reflect the Qur'an's description of paradise, since there are not extensive historical records to reference to. However, many elements of Islamic art and architecture can certainly be interpreted as being intended to reflect paradise as described in the Qur'an, and there are particular historical records which support a number of case studies in this claim. | |||

| Historical evidence does support the claim that certain Islamic garden structures and mosaics, particularly those of Spanish, Persian and Indian origins, were intended to mirror a scene of paradise as described in the Qur'an. | |||

| === Water features in Islamic gardens === | |||

| '''The Alhambra, Court of the Lions, Grenada, Spain''' | |||

| The structural layout of the gardens of the Alhambra in Grenada, embodies the idea of water as a symbol of representing paradise within Islamic gardens. In particular, the Courtyard of the Lions, which follows the Quarter Garden, or the 'Chahar-Bagh' layout, typical to Islamic gardens, features a serene water fountain at its centre.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fang |first=Chenyu |date=2020 |title=Analysis on the Water-Making Art of Islamic Gardens |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/2345535132 |journal=Journal of Landscape Research |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=86 |id={{ProQuest|2345535132}} |via=ProQuest}}</ref> The fountain is carved with stone lions, with the water emerging from the mouths of these lions. The static nature of the locally sourced water features within the Courtyard of the Lions at the Alhambra, adds to the atmosphere of serenity and stillness which is typical of Islamic gardens that utilise water features, resembling the image of paradise as found in the Qur'an.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fang |first=Chenyu |date=2020 |title=Analysis on the Water-Making Art of Islamic Gardens |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/2345535132 |journal=Journal of Landscape Research |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=87 |id={{ProQuest|2345535132}} |via=ProQuest}}</ref> | |||

| ], Grenada]] | |||

| === Tomb Gardens as representing Paradise === | |||

| There is not yet concrete evidence that Islamic gardens were solely intended to represent images of paradise. However, it can be deduced from certain inscriptions and intentions of structures, that creating an atmosphere of divinity and serenity were part of the artists' intentions. | |||

| Tombs became the metaphorical 'paradise on Earth' for Islamic architecture and gardens; they were a place of eternal peace were devout followers of God could rest.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fairchild |first=Ruggles |title=Islamic Gardens and Landscapes |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2008 |location=Pennsylvania |pages=103 |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| '''The Taj Mahal''' | |||

| Upon the exterior of the tomb mausoleum of the Taj Mahal, inscriptions of passages from the Qur'an adorn the exterior facades, encasing the iwans. These inscriptions rehearse passages of an eschatological nature, referencing the Day of Judgement and themes of paradise.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fairchild |first=Ruggles |title=Islamic Gardens and Landscapes |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2008 |location=Pennsylvania |pages=113 |language=English}}</ref> Similarly, the placement of the tomb structure within the waterscape garden environment heightens the conceptual relationship between tomb gardens and a place of paradise as discussed in the Qur'an.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fairchild |first=Ruggles |title=Islamic Gardens and Landscapes |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2008 |location=Pennsylvania |pages=115 |language=English}}</ref> Similarly, the white marble used for the construction of the tomb mausoleum, furthers the relationship between the purity and divinity of the tomb, elevating the status of the tomb to that of paradise. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| === Mosaic representations of paradise within Islamic Architecture === | |||

| Preserved historical writings from an interview with the artisan of the Prophet's Mosque at Medina between 705 and 715, revealed how the mosaic depictions of gardens within this mosque were in fact created ''"according to the picture of the Tree of Paradise and its palaces"''.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fairchild |first=Ruggles |title=Islamic Gardens and Landscapes |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2008 |location=Pennsylvania |pages=95 |language=English}}</ref> Structures that are similarly adorned with naturalistic mosaics, and were created during the same period as the Prophet's Mosque at Medina, can be said to have had the same intended effect. | |||

| '''The mosaic of the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem''' | |||

| Constructed between 690 and 692, the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem features a large-scale mosaic on the interior of the domed structure. It is likely that this richly embellished and detailed mosaic was intended to replicate an image of paradise, featuring fruit-bearing trees, vegetal motifs and flowing rivers. Accompanied by a calligraphic frieze, the mosaic depicts symmetrical and vegetal vine scrolls, surrounded by trees of blue, green and turquoise mosaics. Jewel-like embellishments as well as gold pigment complete the mosaic. Not only did mosaics of this kind seek to reflect paradise as described in the Qur'an, but they were also thought to represent and proclaim Muslim victories.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kaptan |first=Kubilay |date=2013 |title=Early Islamic Architecture and Structural Configurations |url=https://tarjomefa.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/6356-English-TarjomeFa.pdf |journal=International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=7–8 }}</ref> | |||

| '''The mosaic of The Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria''' | |||

| In a similar instance, the mosaic within the Great Mosque of Damascus, constructed within a similar timeframe to the Dome of the Rock, features the most noticeable elements of a paradisiacal garden as described in the Qur'an. Therefore, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that the mosaic on the exterior facade of the Great Mosque of Damascus, was similarly intended to replicate an image of paradise in the viewer's mind. | |||

| ==Gnosticism== | |||

| ], a text from the ] held in ancient ], describes Paradise as being located outside the circuit of the Sun and Moon in the luxuriant Earth east in the midst of stones. The Tree of Life, which will provide for the souls of saints after they come out of their corrupted bodies, is located in the north of Paradise besides the ] that contains the power of God.<ref>{{cite book|author1=]|author2=]|title=The Gnostic Bible|publisher=]|chapter=On the Origin of the World|url=http://gnosis.org/naghamm/origin-Barnstone.html|date=2009|access-date=2021-10-20}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | |||

| <div style="column-count:2;-moz-column-count:2;-webkit-column-count:2"> | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| </div> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==External links |

==External links== | ||

| {{ |

{{Wikiquote|Paradise}} | ||

| {{Wikibooks|God and Religious Toleration/Paradise Meditation}} | |||

| * , Balashon.com | * , Balashon.com | ||

| * , etymonline.com | * , etymonline.com | ||

| * {{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Paradise |volume=20 |pages=751–752 |short=1 |first=Thomas Kelly |last=Cheyne}} | |||

| {{Heaven}} | {{Heaven}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:58, 10 January 2025

Place of exceptional happiness, delight, and bliss For other uses, see Paradise (disambiguation).

In religion and folklore, paradise is a place of everlasting happiness, delight, and bliss. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical, eschatological, or both, often contrasted with the miseries of human civilization: in paradise there is only peace, prosperity, and happiness. Paradise is a place of contentment, a land of luxury and fulfillment containing ever-lasting bliss and delight. Paradise is often described as a "higher place", the holiest place, in contrast to this world, or underworlds such as hell.

In eschatological contexts, paradise is imagined as an abode of the virtuous dead. In Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, heaven is a paradisiacal belief. In Hinduism and Buddhism, paradise and heaven are synonymous, with higher levels available to beings who have achieved special attainments of virtue and meditation. In old Egyptian beliefs, the underworld is Aaru, the reed-fields of ideal hunting and fishing grounds where the dead lived after judgment. For the Celts, it was the Fortunate Isle of Mag Mell. For the classical Greeks, the Elysian fields was a paradisiacal land of plenty where adherents hoped the heroic and righteous dead would spend eternity. In the Zoroastrian Avesta, the "Best Existence" and the "House of Song" are places of the righteous dead. On the other hand, in cosmogonical contexts 'paradise' describes the world before it was tainted by evil.

The concept is a theme in art and literature, particularly of the pre-Enlightenment era. John Milton's Paradise Lost is an example of such usage.

Etymology and concept history

The word "paradise" entered English from the French paradis, inherited from the Latin paradisus, from Greek parádeisos (παράδεισος), from an Old Iranian form, from Proto-Iranian*parādaiĵah- "walled enclosure", whence Old Persian 𐎱𐎼𐎭𐎹𐎭𐎠𐎶 p-r-d-y-d-a-m /paridaidam/, Avestan 𐬞𐬀𐬌𐬭𐬌⸱𐬛𐬀𐬉𐬰𐬀 pairi-daêza-. The literal meaning of this Eastern Old Iranian language word is "walled (enclosure)", from pairi- 'around' (cognate with Greek περί, English peri- of identical meaning) and -diz "to make, form (a wall), build" (cognate with Greek τεῖχος 'wall'). The word's etymology is ultimately derived from a PIE root *dheigʷ "to stick and set up (a wall)", and *per "around".

By the 6th/5th century BCE, the Old Iranian word had been borrowed into Assyrian pardesu "domain". It subsequently came to indicate the expansive walled gardens of the First Persian Empire, and was subsequently borrowed into Greek as παράδεισος parádeisos "park for animals" in the Anabasis of the early 4th century BCE Athenian Xenophon, Aramaic as pardaysa "royal park", and Hebrew as פַּרְדֵּס pardes, "orchard" (appearing thrice in the Tanakh; in the Song of Solomon (Song of Songs 4:13), Ecclesiastes (Ecclesiastes 2:5) and Nehemiah (Nehemiah 2:8)). In the Septuagint (3rd–1st centuries BCE), Greek παράδεισος parádeisos was used to translate both Hebrew פרדס pardes and Hebrew גן gan, "garden" (e.g. (Genesis 2:8, Ezekiel 28:13): it is from this usage that the use of "paradise" to refer to the Garden of Eden derives. The same usage also appears in Arabic and in the Quran as firdaws فردوس.

The idea of a walled enclosure was not preserved in most Iranian usage, and generally came to refer to a plantation or other cultivated area, not necessarily walled. For example, the Old Iranian word survives as Pardis in New Persian as well as its derivative pālīz (or "jālīz"), which denotes a vegetable patch.

Biblical

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew word pardes appears only in the post-Exilic period (after 538 BCE); it occurs in the Song of Songs 4:13, Ecclesiastes 2:5, and Nehemiah 2:8, in each case meaning "park" or "garden", the original Persian meaning of the word, where it describes the royal parks of Cyrus the Great by Xenophon in Anabasis.

In Second Temple era Judaism, "paradise" came to be associated with the Garden of Eden and prophecies of restoration of Eden, and transferred to heaven.

In the apocryphal Apocalypse of Moses, Adam and Eve are expelled from paradise (rather than Eden) after the Fall of man, having been tricked by the serpent. After the death of Adam, the Archangel Michael carries Adam's body to be buried in Paradise, in the Third Heaven.

New Testament

The Greek word παράδεισος appears three times in the New Testament:

- Luke 23:43 – by Jesus on the cross, in response to the thief's request that Jesus remember him when he came into his kingdom.

- 2 Cor. 12:4 – in Paul's description of a third heaven paradise.

- Rev. 2:7 – alluding to the tree of life mentioned at Gen.2:8.

Judaism

See also: Paradise in JudaismAccording to Jewish eschatology, the higher Gan Eden is called the "Garden of Righteousness". It has been created since the beginning of the world, and will appear gloriously at the end of time. The righteous dwelling there will enjoy the sight of the heavenly chayot carrying the throne of God. Each of the righteous will walk with God, who will lead them in a dance. Its Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants are "clothed with garments of light and eternal life, and eat of the tree of life" (Enoch 58,3) near to God and His anointed ones. This Jewish rabbinical concept of a higher Gan Eden is opposed by the Hebrew terms gehinnom (the source, via Yiddish, of the English "Gehenna") and sheol, figurative names for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism, a place envisioned as being at the greatest possible distance from heaven.

Rabbinic Judaism

In modern Jewish eschatology it is believed that history will complete itself and the ultimate destination will be when all mankind returns to the Garden of Eden.

In the Talmud and the Jewish Kabbalah, the scholars agree that there are two types of spiritual places called "Garden in Eden". The first is rather terrestrial, of abundant fertility and luxuriant vegetation, known as the "lower Gan Eden". The second is envisioned as being celestial, the habitation of righteous, Jewish and non-Jewish, immortal souls, known as the "higher Gan Eden". The rabbis differentiate between Gan and Eden. Adam is said to have dwelt only in the Gan, whereas Eden is said never to be witnessed by any mortal eye. In Rabbinic Judaism, the word 'Pardes' recurs, but less often in the Second Temple context of Eden or restored Eden. A well-known reference is in the Pardes story, where the word may allude to mystic philosophy.

The Zohar gives the word a mystical interpretation, and associates it with the four kinds of Biblical exegesis: peshat (literal meaning), remez (allusion), derash (anagogical), and sod (mystic). The initial letters of those four words then form פַּרְדֵּס – p(a)rd(e)s, which was in turn felt to represent the fourfold interpretation of the Torah (in which sod – the mystical interpretation – ranks highest).

Christianity

See also: World to Come, Kingship and kingdom of God, and Hades in Christianity

In the 2nd century AD, Irenaeus distinguished paradise from heaven. In Against Heresies, he wrote that only those deemed worthy would inherit a home in heaven, while others would enjoy paradise, and the rest live in the restored Jerusalem (which was mostly a ruin after the Jewish–Roman wars but was rebuilt beginning with Constantine the Great in the 4th century). Origen likewise distinguished paradise from heaven, describing paradise as the earthly "school" for souls of the righteous dead, preparing them for their ascent through the celestial spheres to heaven.

Many early Christians identified Abraham's bosom with paradise, where the souls of the righteous go until the resurrection of the dead; others were inconsistent in their identification of paradise, such as St. Augustine, whose views varied.

In Luke 23:43, Jesus has a conversation with one of those crucified with him, who asks, "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom". Jesus answers him, "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise". This has often been interpreted to mean that on that same day the thief and Jesus would enter the intermediate resting place of the dead who were waiting for the Resurrection. Divergent views on paradise, and when one enters it, may have been responsible for a punctuation difference in Luke; for example, the two early Syriac versions translate Luke 23:43 differently. The Curetonian Gospels read "Today I tell you that you will be with me in paradise", whereas the Sinaitic Palimpsest reads "I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise". Likewise the two earliest Greek codices with punctuation disagree: Codex Vaticanus has a pause mark (a single dot on the baseline) in the original ink equidistant between 'today' and the following word (with no later corrections and no dot before "today"), whereas Codex Alexandrinus has the "today in paradise" reading. In addition, an adverb of time is never used in the nearly 100 other places in the Gospels where Jesus uses the phrase, "Truly I say to you".

In Christian art, Fra Angelico's Last Judgement painting shows Paradise on its left side. There is a tree of life (and another tree) and a circle dance of liberated souls. In the middle is a hole. In Muslim art it similarly indicates the presence of the Prophet or divine beings. It visually says, "Those here cannot be depicted".

Jehovah's Witnesses

See also: Jehovah's Witnesses and salvationJehovah's Witnesses believe, from their interpretation of the Book of Genesis, that God's original purpose was, and is, to have the earth filled with the offspring of Adam and Eve as caretakers of a global paradise. However, Adam and Eve rebelled against God's sovereignty and were banished from the Garden of Eden, driven out of paradise into toil and misery.

Jehovah's Witnesses believe that disobedient and wicked people will be destroyed by Christ at Armageddon and those obedient to Christ will live eternally in a restored earthly paradise. Joining the survivors will be the resurrected righteous and unrighteous people who died prior to Armageddon. The latter are brought back because they paid for their sins by their death and/or because they lacked opportunity to learn of Jehovah's requirements before dying. These will be judged on the basis of their post-resurrection obedience to instructions revealed in new "scrolls". They believe that resurrection of the dead to paradise earth is made possible by Christ's blood and the ransom sacrifice. This provision does not apply to those whom Christ as Judge deems to have sinned against God's holy spirit.

One of Jesus' statements before he died were the words to a man hanging alongside him, "you will be with me in Paradise." The New World Translation places a comma after the word 'today', dividing it into two separate phrases, "I tell you today" and "you will be with me in Paradise". This differs from standard translations of this verse as "I tell you today you will be with me in Paradise". Based on scriptures such as Matthew 12:40, 27:63, Mark 8:31 and 9:31, Witnesses believe Jesus' expectation that he would be bodily resurrected after three days precluded his being in paradise on the same day that he died.

Mormonism

In Latter Day Saint theology, paradise usually refers to the spirit world, the place where spirits dwell following death and awaiting the resurrection. In that context, "paradise" is the state of the righteous after death. In contrast, the wicked and those who have not yet learned the gospel of Jesus Christ await the resurrection in spirit prison. After the universal resurrection, all persons will be assigned to a particular kingdom or degree of glory. This may also be termed "paradise".

Islam

Main article: Jannah

In the Quran, Heaven is denoted as Jannah (garden), with the highest level being called Firdaus, i.e. Paradise. It is used instead of Heaven to describe the ultimate pleasurable place after death, accessible by those who pray, donate to charity, and believe in: Allah, the angels, his revealed books, his prophets and messengers, the Day of Judgement and divine decree (Qadr), and follow God's will in their life. Heaven in Islam is used to describe skies in the literal sense and metaphorically to refer to the universe. In Islam, the bounties and beauty of Heaven are immense, so much so that they are beyond the abilities of mankind's worldly mind to comprehend. There are eight doors of Jannah. These are eight grades of Jannah:

- 1. Jannah al-Mawa

- 2. Dar al-Maqam

- 3. Dar al-Salam

- 4. Dar al-Khuld

- 5. Jannah al-Adn

- 6. Jannah al-Na'im

- 7. Jannah al-Kasif

- 8. Jannah al-Firdaus

Jannah al-Mawa is in the lowest, Jannah al-Adn is the middle and Jannah al-Firdaus is the highest.

Imam Bukhari has also recorded the tradition in which the Prophet said,

'When you ask from Allah, ask Him for Al-Firdaus, for it is the middle of Paradise and it is the highest place and from it the rivers of Paradise flow.' (Bukhari, Ahmad, Baihaqi)

In this tradition, it is evident that Al-Firdaus is the highest place in Paradise, yet, it is stated that it is in the middle. While giving an explanation of this description of Al-Firdaus, the great scholar, Ibn Hibban states,

'Al-Firdaus being in the middle of Paradise means that with respect to the width and breadth of Paradise, Al-Firdaus is in the middle. And with respect to being 'the highest place in Paradise', it refers to it being on a height.'

This explanation is in agreement to the explanation which has been given by Abu Hurairah (r.a.) who said that

'Al Firdaus is a mountain in Paradise from which the rivers flow.' (Tafseer Al Qurtubi Vol. 12 pg. 100)

The Quran also gave a warning that not all Muslims or even the believers will assuredly be permitted to enter Jannah except those who had struggled in the name of God and tested from God's trials as faced by the messengers of God or ancient prophets:

Or do you think that you will enter Paradise while such has not yet come to you as came to those who passed on before you? They were touched by poverty and hardship and were shaken until messenger and those who believed with him said,"When is the help of Allah ?" Unquestionably, the help of Allah is near.

— Qur'an 2:214 (Al-Baqarah) (Saheeh International)

Other instances where paradise is mentioned in the Qur'an includes descriptions of springs, silk garments, embellished carpets and women with beautiful eyes. These elements can also be seen as depicted within Islamic art and architecture.

"The semblance of Paradise (Jannah) promised the pious and devout (is that of a garden) with streams of water that will not go rank, and rivers of milk whose taste will not undergo a change, and rivers of wine delectable to drinkers, and streams of purified honey, and fruits of every kind in them, and forgiveness from their Lord." (47:15).

References to Paradise (Jannah) in the Qur'an as reflected in Islamic art

The Qur'an contains multiple passages in which paradise, or 'Jannah', is referred to. The Holy Book contains 166 references to gardens, of which nineteen mention 'Jannah', connoting both images of paradise through gardens, water features, and fruit-bearing trees. Scholars are unable to confirm that certain artistic choices were solely intended to reflect the Qur'an's description of paradise, since there are not extensive historical records to reference to. However, many elements of Islamic art and architecture can certainly be interpreted as being intended to reflect paradise as described in the Qur'an, and there are particular historical records which support a number of case studies in this claim.

Historical evidence does support the claim that certain Islamic garden structures and mosaics, particularly those of Spanish, Persian and Indian origins, were intended to mirror a scene of paradise as described in the Qur'an.

Water features in Islamic gardens

The Alhambra, Court of the Lions, Grenada, Spain

The structural layout of the gardens of the Alhambra in Grenada, embodies the idea of water as a symbol of representing paradise within Islamic gardens. In particular, the Courtyard of the Lions, which follows the Quarter Garden, or the 'Chahar-Bagh' layout, typical to Islamic gardens, features a serene water fountain at its centre. The fountain is carved with stone lions, with the water emerging from the mouths of these lions. The static nature of the locally sourced water features within the Courtyard of the Lions at the Alhambra, adds to the atmosphere of serenity and stillness which is typical of Islamic gardens that utilise water features, resembling the image of paradise as found in the Qur'an.

Tomb Gardens as representing Paradise

There is not yet concrete evidence that Islamic gardens were solely intended to represent images of paradise. However, it can be deduced from certain inscriptions and intentions of structures, that creating an atmosphere of divinity and serenity were part of the artists' intentions.

Tombs became the metaphorical 'paradise on Earth' for Islamic architecture and gardens; they were a place of eternal peace were devout followers of God could rest.

The Taj Mahal

Upon the exterior of the tomb mausoleum of the Taj Mahal, inscriptions of passages from the Qur'an adorn the exterior facades, encasing the iwans. These inscriptions rehearse passages of an eschatological nature, referencing the Day of Judgement and themes of paradise. Similarly, the placement of the tomb structure within the waterscape garden environment heightens the conceptual relationship between tomb gardens and a place of paradise as discussed in the Qur'an. Similarly, the white marble used for the construction of the tomb mausoleum, furthers the relationship between the purity and divinity of the tomb, elevating the status of the tomb to that of paradise.

Mosaic representations of paradise within Islamic Architecture

Preserved historical writings from an interview with the artisan of the Prophet's Mosque at Medina between 705 and 715, revealed how the mosaic depictions of gardens within this mosque were in fact created "according to the picture of the Tree of Paradise and its palaces". Structures that are similarly adorned with naturalistic mosaics, and were created during the same period as the Prophet's Mosque at Medina, can be said to have had the same intended effect.

The mosaic of the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem

Constructed between 690 and 692, the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem features a large-scale mosaic on the interior of the domed structure. It is likely that this richly embellished and detailed mosaic was intended to replicate an image of paradise, featuring fruit-bearing trees, vegetal motifs and flowing rivers. Accompanied by a calligraphic frieze, the mosaic depicts symmetrical and vegetal vine scrolls, surrounded by trees of blue, green and turquoise mosaics. Jewel-like embellishments as well as gold pigment complete the mosaic. Not only did mosaics of this kind seek to reflect paradise as described in the Qur'an, but they were also thought to represent and proclaim Muslim victories.

The mosaic of The Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria

In a similar instance, the mosaic within the Great Mosque of Damascus, constructed within a similar timeframe to the Dome of the Rock, features the most noticeable elements of a paradisiacal garden as described in the Qur'an. Therefore, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that the mosaic on the exterior facade of the Great Mosque of Damascus, was similarly intended to replicate an image of paradise in the viewer's mind.

Gnosticism

On the Origin of the World, a text from the Nag Hammadi library held in ancient Gnosticism, describes Paradise as being located outside the circuit of the Sun and Moon in the luxuriant Earth east in the midst of stones. The Tree of Life, which will provide for the souls of saints after they come out of their corrupted bodies, is located in the north of Paradise besides the Tree of Knowledge that contains the power of God.

See also

- Deylaman

- Dilmun

- Eridu

- El Dorado

- Fiddler's Green

- Golden Age

- Goloka

- Heaven

- Nirvana

- Paradise garden

- Shangri-La

- Tír na nÓg

- Valhalla

References

- "Paradise | religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- British Museum notice in 2018 temporary exhibit "I am Ashurbanipal king of the world, king of Assyria"

- ^ Charnock, Richard Stephen (1859). Local Etymology: A Derivative Dictionary of Geographical Names. Houlston and Wright. p. 201.

- ^ "Paradise: Origin and meaning of paradise by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ New Oxford American Dictionary

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "An Etymological Dictionary of Astronomy and Astrophysics". Archived from the original on 2015-01-15. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1151.

- ^ Eshatology – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.

- Leo Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish, © 1968; Pocket Books edition, 1970, p. 127:

"Gehenna... Hebrew: Gehinom: 'Hell.' Literally: the Valley (gay) of Hinnom" - "End of Days". Aish. 11 January 2000. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ Gan Eden – JewishEncyclopedia; 02-22-2010.

- "JewishEncyclopedia.com". Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Church fathers: De Principiis (Book II) Origen Archived 2008-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, newadvent.org

- Jean Delumeau (1995). History of paradise. University of Illinois Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-252-06880-5. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- "Luke 23". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- A. W. Zwiep (1997). The Ascension of the Messiah in Lukan Christology /. BRILL. pp. 150–. ISBN 978-90-04-10897-4. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- "The Significance of a Comma: An Analysis of Luke 23:43 – Ministry Magazine". Ministry Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "For an Answer: Christian Apologetics – Luke 23:43". www.forananswer.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- What Does the Bible Really Teach? (Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, 2005), Chapter 7

- Insight on the Scriptures (Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, 1988), 783–92

- Luke 23:43

- "Luke 23:43". Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "Meeting the Challenge of Bible Translation", The Watchtower, June 15, 1974, page 362–363

- Duane S. Crowther – Life Everlasting Chapter 5 – Paradise of the Wicked – Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ Fairchild, Ruggles (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 89.

- Mehdi, Aqsa (2021). "A Comparative Study Between the Qur'an's Vision of Paradise and the Mughal Islamic Gardens of Lahore" (PDF). Online Journal of Art and Design. 9 (3): 7 – via Adjournal.

- Fang, Chenyu (2020). "Analysis on the Water-Making Art of Islamic Gardens". Journal of Landscape Research. 12 (1): 86. ProQuest 2345535132 – via ProQuest.

- Fang, Chenyu (2020). "Analysis on the Water-Making Art of Islamic Gardens". Journal of Landscape Research. 12 (1): 87. ProQuest 2345535132 – via ProQuest.

- Fairchild, Ruggles (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 103.

- Fairchild, Ruggles (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 113.

- Fairchild, Ruggles (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 115.

- Fairchild, Ruggles (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 95.

- Kaptan, Kubilay (2013). "Early Islamic Architecture and Structural Configurations" (PDF). International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development. 3 (2): 7–8.

- Marvin Meyer; Willis Barnstone (2009). "On the Origin of the World". The Gnostic Bible. Shambhala. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

External links

- Etymology of "paradise", Balashon.com

- Etymology OnLine, etymonline.com

- Cheyne, Thomas Kelly (1911). "Paradise" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 751–752.