| Revision as of 18:01, 19 April 2006 edit12.217.178.159 (talk) →Popular Examples← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:22, 8 January 2025 edit undo151.177.92.239 (talk) →History | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Increasing levels in recorded music}} | |||

| The phrase '''loudness war''' (or '''loudness race''') refers to the practice of recording music at progressively higher and higher levels, to create CDs that are as loud as possible or louder than CDs from competing artists or recording labels. Louder CDs are perceived as sounding louder when played with the same equipment at the same settings. One reason for this practice is that when comparing two CDs, the louder one will sound better on first impression. This is partly due to the way in which the human ear behaves, as its frequency response will change according to different sound levels being heard, with the listener perceiving a greater amount of low and high frequencies as sound pressure levels increase. Higher levels can also result in subjectively better sounding recordings on low quality reproduction systems, such as web audio formats, AM radio, mono television and telephones, but since most of the material affected is delivered via CD audio, it is largely seen as detrimental to overall quality, given that one of the initial benefits of a CD was its enhanced dynamic range. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

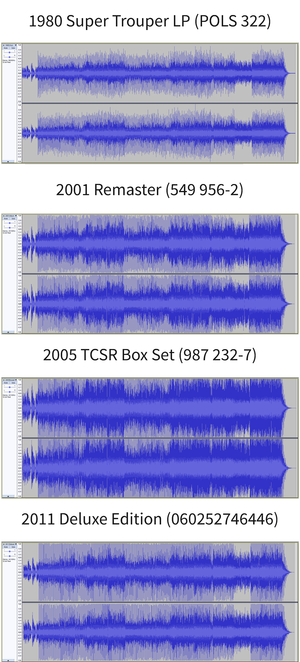

| ]'s 1980 song "]" show different levels of loudness compared to the original 1980 release. This is displayed in ], a basic ].|alt=]] | |||

| To educated ears this practice is unnecessary, since if listeners want to listen to loud music, they can simply turn up the volume on their playback equipment. If a CD is broadcast by a radio station, the station will have its own equipment that reduces the dynamic range of material it broadcasts to far more closely matching levels of absolute amplitude, regardless of the original recording's loudness. , | |||

| The '''loudness war''' (or '''loudness race''') is a trend of increasing audio levels in recorded music, which reduces audio fidelity and—according to many critics—listener enjoyment. Increasing ] was first reported as early as the 1940s, with respect to ] practices for ]s.<ref name=npr2009/> The maximum ] of analog recordings such as these is limited by varying specifications of electronic equipment along the chain from source to listener, including ] and ] players. The issue garnered renewed attention starting in the 1990s with the introduction of ] capable of producing further loudness increases. | |||

| This practice often results in a form of distortion known as ]. The loudness wars have reached a point at which most pop CDs, and many classical and jazz CDs, have large amounts of digital clipping, making them harsh and fatiguing to listen to, especially, ironically, on high quality equipment. On the CDs where clipping does not occur—or does not occur as frequently as would when simple digital amplification is involved—a process known as ] is used. While the resulting distortion is lessened from the final product this way, it unfortunately has the side effect of significantly reducing ] response, most often heard as lessened drum impact and, when taken to severe levels, can reduce the natural dynamic ranges of other instruments within the recording and, depending on the opinion of the listener, reduce sonic clarity. Both methods can be relatively transparent in moderate cases; however with the levels that are commonly demanded as of now this is seldom a possibility. | |||

| With the advent of the compact disc (CD), music is encoded to a ] with a clearly defined maximum peak amplitude. Once the maximum amplitude of a CD is reached, loudness can be increased still further through ] techniques such as ] and ]. Engineers can apply an increasingly high ratio of compression to a recording until it more frequently peaks at the maximum amplitude. In extreme cases, efforts to increase loudness can result in ] and other audible ].<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/opinion/what-these-grammy-songs-tell-us-about-the-loudness-wars.html |title=They Really Don't Make Music Like They Used To |first=Greg |last=Milner |date=7 February 2019 |newspaper=]}}</ref> Modern recordings that use extreme dynamic range compression and other measures to increase loudness therefore can sacrifice sound quality to loudness. The competitive escalation of loudness has led music fans and members of the musical press to refer to the affected albums as "victims of the loudness war". | |||

| Further, current compression equipment allows engineers to create a recording that has a nearly uniform dynamic range. When that level is set very close to the maximum allowed by the CD format, this creates near-continuous distortion throughout the disc. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| This situation has been widely condemned. Some have petitioned their favorite groups to rerelease some CDs with less distortion. Others have even said that recording engineers who knowingly push their recording equipment past clipping should be blacklisted and not allowed to "victimize artists or music lovers." Many have suggested boycotting recordings that they feel showcase the phenomenon to the point of significantly lessened satisfaction with the product (often to the point of lessened, or even nonexistent, listening as opposed to otherwise) to communicate the existence of disdain for the practice to the offending parties, though it is often stated that such an attempt would be interpreted by the music industry as wanton ]. | |||

| The practice of focusing on loudness in audio mastering can be traced back to the introduction of the compact disc,<ref name="Stuart Dredge" /> but also existed to some extent when the ] was the primary released recording medium and when ] were played on ] machines in clubs and bars. The so-called ''wall of sound'' (not to be confused with the ] ]) formula preceded the loudness war, but achieved its goal using a variety of techniques, such as instrument doubling and ], as well as ].<ref name="loudness-war-vickers">{{cite conference |url=https://www.sfxmachine.com/docs/loudnesswar/loudness_war.pdf |title=The Loudness War: Background, Speculation and Recommendations |last=Vickers |first=Earl |date=4 November 2010 |conference=129th Audio Engineering Society Convention |conference-url=https://www.aes.org/events/129/ |publisher=] |location=] |id=8175 |access-date=17 November 2020}}</ref> | |||

| Jukeboxes became popular in the 1940s and were often set to a predetermined level by the owner, so any record that was mastered louder than the others would stand out. Similarly, starting in the 1950s, producers would request louder 7-inch singles so that songs would stand out when auditioned by ]s for radio stations.<ref name=npr2009>{{Cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122114058&sc=nl&cc=mn-20100102 |publisher=NPR |title=The Loudness Wars: Why Music Sounds Worse |date=31 December 2009 |access-date=2 September 2010}}</ref> In particular, many ] records pushed the limits of how loud records could be made; according to one of their engineers, they were "notorious for cutting some of the hottest 45s in the industry."<ref name="bigsqueeze">{{citation |url=http://mixonline.com/mag/audio_big_squeeze/ |title=The Big Squeeze: Mastering engineers debate music's loudness wars |work=Mix Magazine |date=1 December 2005 |access-date=2 September 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100825003547/http://mixonline.com/mag/audio_big_squeeze/ |archive-date=25 August 2010 }}</ref> In the 1960s and 1970s, ]s of hits by multiple different artists became popular, and if artists and producers found their song was quieter than others on the compilation, they would insist that their song be ]ed to be competitive. | |||

| It should be made clear that this distortion is different from other kinds of distortion such as overdrive or feedback (see ]), which is created by electronic musical instruments, not by the recording process, and which can be an intentional and integral part of the performance (see ]). Digital clipping is created through the recording process, not by instruments creating sound naturally, though musicians have been accused of requesting the sorts of loudness that encourages this phenomenon. Ironically, sometimes ]-style distortion is used in the mastering process to achieve similar results, either through analog tape saturation and valve distortion prior to digital transfer or computer software used to emulate these processes; this is notably more common in ] recordings than ] ones. | |||

| Because of the limitations of the vinyl format, the ability to manipulate loudness was also limited. Attempts to achieve extreme loudness could render the medium unplayable. One example was the ''hot'' master of '']'' by mastering engineer ] which caused some ] to mistrack; the album was recalled and issued with lower compression levels.<ref name="i728">{{cite magazine | last=Chun | first=Rene | title=Why Audiophiles Are Paying $1,000 for This Man's Vinyl | magazine=] | date=March 4, 2015 | url=https://www.wired.com/2015/03/hot-stampers/ | access-date=September 3, 2024 }}</ref> Digital media such as CDs remove these restrictions and as a result, increasing loudness levels have been a more severe issue in the CD era.<ref name="Austin">{{citation |url=http://www.austin360.com/music/content/music/stories/xl/2006/09/28cover.html |title=Everything Louder Than Everything Else |author=Joe Gross |date=2 October 2006 |publisher=Austin 360 |access-date=24 November 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061019013037/http://www.austin360.com/music/content/music/stories/xl/2006/09/28cover.html|archive-date=19 October 2006}}</ref> Modern computer-based digital audio effects processing allows mastering engineers to have greater direct control over the loudness of a song: for example, a ''brick-wall limiter'' can look ahead at an upcoming signal to limit its level.<ref name="performermag">{{citation |url=http://performermag.com/Archives/loudness.php |title=The Loudness War |author=Mark Donahue |publisher=Performer |access-date=24 November 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Another consequence of the loudness war is that even if there is no distortion, the sound of the CD utilizing the upper amplitude ranges will have a narrow dynamic range, with less rise, fall or sense of dynamic shaping. The music has been "squashed", so to speak. Pop music in general has not been interested in the expressive possibilities of crescendos, diminuendos, sudden loudness or quietness, or any of the other dynamic devices available to musicians, but the loudness war has eliminated even the possibility of dynamic expressiveness in recorded pop music. That said, lack of a wide dynamic range is not necessarily the result of attempting loudness, as loudness-based compressors (such as limiters) are designed to be as transparent of the original signal as possible, which means that macrodynamics (the difference in volume between sections of a song) are relatively unaffected by such processes. Often slow-acting, broadcast-style compression will be applied to the music to make the differences in volume between song sections more uniform for background listening or noisy environments (such as in the car), while multi-band compression is commonly used to make a mix more uniform and easier to balance, more compatible with low-end equipment and/or to achieve a certain "sound" or artistic effect. Often these sorts of compression are confused with the sort inherent in making loud CDs, and there are many cases where a loud CD can sound better than it does at the same level because other, non-loudness related mastering methods were used in excess. | |||

| ]'s song "]" show increasing loudness over time: 1983–2000–2008.<ref>"Sharp Dressed Man" plotted using MasVis, a freeware mastering analysis program.</ref>]] | |||

| == History == | |||

| ===1980s=== | |||

| ''(Note: Some of these examples are explained using ] ] values. In reference to CD audio, these values are based on the calculation of the average of ] ] with digital full scale used as a reference. It is a common way to determine the absolute loudness of a recording, though discrepancies in musical arrangements can cause inconsistencies in regards to aforementioned value versus perceived loudness.)'' | |||

| Since CDs were not the primary medium for popular music until the late 1980s, there was little motivation for competitive loudness practices then. The common practice of mastering music for CD involved matching the highest peak of a recording at, or close to, digital ], and referring to digital levels along the lines of more familiar analog ]s. When using VU meters, a certain point (usually −14 dB below the disc's maximum amplitude) was used in the same way as the saturation point (signified as 0 dB) of analog recording, with several dB of the CD's recording level reserved for amplitude exceeding the saturation point (often referred to as the ''red zone'', signified by a red bar in the meter display), because digital media cannot exceed 0 decibels relative to full scale (]).{{citation needed|reason=None of this is in Katz|date=September 2017}} The average ] level of the average rock song during most of the decade was around −16.8 dBFS.<ref name=Katz3rd />{{rp|246}} | |||

| ===1990s=== | |||

| Due to the high subjectiveness of audio listening amongst individuals, pinpointable stages of the loudness war and its impact will vary quite a bit chronologically depending on who you inquire. The practice of focusing on loudness in mastering for purposes of competition or otherwise can not only be traced back to the very introduction of the compact disc itself, but has also been said to exist during the period when vinyl was the primary released recording medium for popular music. However, because of the limitations of the vinyl format, loudness and compression on a released recording were restricted in order to make the physical medium playable—restrictions distant from the infinite possibilities of digital playback mediums such as CDs—and as a result never reached the significance that they have in the digital music age. Extraordinarily hot recording levels like those showcased by ] ] artist ], which are significantly louder than even the norm for popular CDs today, would be impossible on vinyl. | |||

| By the early 1990s, mastering engineers had learned how to optimize for the CD medium and the loudness war had not yet begun in earnest.<ref name="Stylus">{{cite magazine |author=Southall, Nick |url=http://www.stylusmagazine.com/articles/weekly_article/imperfect-sound-forever.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060612221324/http://www.stylusmagazine.com/articles/weekly_article/imperfect-sound-forever.htm |title=Imperfect Sound Forever |magazine=] |date=1 May 2006 |archive-date=12 June 2006}}</ref> However, in the early 1990s, CDs with louder music levels began to surface, and CD levels became more and more likely to bump up to the digital limit,<ref group="note">Up to 2 or 4 consecutive full-scale samples was considered acceptable.</ref> resulting in recordings where the peaks on an average rock or beat-heavy pop CD hovered near 0 dBFS,<ref group="note" name=":0">Usually in the range of −3 dB.</ref> but only occasionally reached it.{{citation needed|date=October 2017}} | |||

| The concept of making music releases ''hotter'' began to appeal to people within the industry, in part because of how noticeably louder some releases had become and also in part because the industry believed that customers preferred louder-sounding CDs, even though that may not have been true.<ref>{{Cite thesis|degree=Masters|last=Viney|first=Dave|date=December 2008|publisher=]|title=The Obsession With Compression|url=https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/8441718/DRD/project%20dissertation.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160421205047/https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/8441718/DRD/project%20dissertation.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=2016-04-21|page=54|access-date=24 July 2011|quote=there is no evidence of any significant correlation between loudness (& implied compression) and commercial success }}</ref> Engineers, musicians, and labels each developed their own ideas of how CDs could be made louder.<ref name=Milner /> In 1994, the first digital brick-wall limiter with look-ahead (the ]) was mass-produced; this feature, since then, has been commonly incorporated in digital mastering limiters and maximizers.<ref group="note">Look-ahead is a window of time in which the processor analyzes the audio amplitude in advance and predicts the amount of gain reduction needed to meet the requested output level (0 dBFS); this permits the limiter to react to incoming transients avoiding clipping. Since an audio ] is needed to achieve this, look-ahead is only possible in the digital domain and introduces a small amount of ] to the output signal.</ref> While the increase in CD loudness was gradual throughout the 1990s, some opted to push the format to the limit, such as on ]'s widely popular album '']'', whose RMS level averaged −8 dBFS on many of its tracks—a rare occurrence, especially in the year it was released (1995).<ref name="Stylus" /> ]'s '']'' (1999) represented another milestone, with prominent clipping occurring throughout the album.<ref name="Milner" /> | |||

| The stages of CD loudness is often generally split over the three decades of the medium's existence. Since CDs were not the primary listening medium for popular music up until the tail end of the ], there was little motivation for competitive loudness practices for the format during most of the decade. The fact that CD players were also very expensive and thus commonly exclusive to high-end systems that benefited less from advanced recording levels during this period can also be attributed as a major contributing factor. As a result, the two theoretical common practices of mastering CDs involved either matching the highest peak of a recording at, or close to, digital full scale, or referencing digital levels along the lines of more commonly familiarized analog VU meters, with a certain point (usually −6 dB, or 50% of the disc's amplitude on a linear scale) utilized in the same way as the saturation point (signified as 0db) of analog recording, with several dB of the CDs recording level reserved in the same way that a similar amount was for the amplitude exceeding the saturation point in analog tape (often referred to as the "red zone", signified by a red bar in the meter display), only in this case there would be no saturation of the peaks involved since the actual medium is digital. The RMS level of the average rock song during most of the decade was usually around −18 dB. | |||

| ===2000s=== | |||

| At the turn of the decade CDs louder than this common reference level began to surface, and CDs steadily became more and more apt to have peaks exceeding the digital limit as long as such amplification would not involve the clipping of more than approximately 2-4 digital samples, resulting in recordings where the peaks on an average rock or beat-heavy pop CD hovered close (usually in the range of 3 dB) to full scale but only occasionally reached it. ]'s ] album '']'' is an early example of this, with RMS levels averaging −15 dB for all the tracks. In the early ], however, some mastering engineers decided to take this a step further, and treat the CDs levels exactly as they would the levels of an analog tape and equate digital full scale with the analog saturation point, with the recording just loud enough so that each (or almost every) beat would peak at or over full scale. Though there were some early cases (such as ]'s self-titled ] in ]), albums mastered in this fashion generally did not appear until ]. ]'s '']'', ]'s ] and ]'s '']'' are some examples of this from said year. This time period (1988-1992) was an extremely erratic time for CD mastering. The loudness of CDs varied massively depending on the philosophies of the engineer (and others involved in the mastering process) as CD mastering became more lenient as opposed to what it was in the early stages of the medium's existence. ] was arguably the year in which this style of "hot" mastering became commonplace, though exceptions, such as the album '']'' by ] from the same year, still existed. The most common loudness for a rock CD in terms of RMS power was around −12 dB, though depending on how an album was mixed it could be higher or lower (as was the case with the ] album '']'', a consistently-peaking melodic metal album released in ] averaging −14db, as well as the aforementioned 1991 Metallica release). Overall, most rock and pop CDs released in the '90s followed this method to a certain extent. | |||

| ] comparison showing how the CD release of ''Death Magnetic'' (top) employed heavy compression resulting in higher average levels than the ''Guitar Hero'' downloadable version (bottom)|alt=|300x300px]] | |||

| By the early 2000s, the loudness war had become fairly widespread, especially with some remastered re-releases and greatest hits collections of older music. In 2008, loud mastering practices received mainstream media attention with the release of ]'s '']'' album. The CD version of the album has a high average loudness that pushes peaks beyond the point of digital clipping, causing distortion. This was reported by customers and music industry professionals, and covered in multiple international publications, including '']'',<ref name="rs_history"> | |||

| {{cite magazine | |||

| | last = Kreps | |||

| | first = Daniel | |||

| | title = Fans Complain After 'Death Magnetic' Sounds Better on "Guitar Hero" Than CD | |||

| | magazine = Rolling Stone | |||

| | date = 18 September 2008 | |||

| | url = https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/fans-complain-after-death-magnetic-sounds-better-on-guitar-hero-than-cd-20080918 | |||

| | access-date = 15 March 2011 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> '']'',<ref name="wsj_history"> | |||

| {{cite news | |||

| | last = Smith | |||

| | first = Ethan | |||

| | title = Even Heavy-Metal Fans Complain That Today's Music Is Too Loud!!! | |||

| | access-date = 17 October 2008 | |||

| | date = 25 September 2008 | |||

| | newspaper = The Wall Street Journal | |||

| | url = https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB122228767729272339 | |||

| }}</ref> ],<ref name="bbc_radio_history"> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| |title = 'Death Magnetic' Sound Quality Controversy Focus Of BBC RADIO 4 Report | |||

| |publisher = BlabberMouth.net | |||

| |date = 10 October 2008 | |||

| |url = http://www.roadrunnerrecords.com/blabbermouth.net/news.aspx?mode=Article&newsitemID=106612 | |||

| |access-date = 17 October 2008 | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081013163314/http://www.roadrunnerrecords.com/blabbermouth.net/news.aspx?mode=Article&newsitemID=106612 | |||

| |archive-date = 13 October 2008 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> '']'',<ref name="wired_history"> | |||

| {{Cite magazine | |||

| | last = Van Buskirk | |||

| | first = Eliot | |||

| | title = Analysis: Metallica's Death Magnetic Sounds Better in Guitar Hero | |||

| | magazine = Wired | |||

| | date = 16 September 2008 | |||

| | url = http://blog.wired.com/music/2008/09/does-metallicas.html | |||

| | access-date = 17 September 2008 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> and '']''.<ref name="guardian_history"> | |||

| {{cite news | |||

| | last = Michaels | |||

| | first = Sean | |||

| | title = Death Magnetic 'loudness war' rages on | |||

| | newspaper = The Guardian | |||

| | date = 1 October 2008 | |||

| | url = https://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/oct/01/metallica.popandrock | |||

| | access-date = 17 October 2008 | |||

| | location=London | |||

| }}</ref> ], a mastering engineer involved in the ''Death Magnetic'' recordings, criticized the approach employed during the production process.<ref> | |||

| {{cite news | |||

| | url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/sep/17/metallica.guitar.hero.loudness.war | |||

| | title=Metallica album latest victim in 'loudness war'? | |||

| | newspaper=The Guardian | |||

| | date=17 September 2008 | |||

| | access-date=17 September 2008 | |||

| | location=London | |||

| | first=Sean | |||

| | last=Michaels}}</ref> When a version of the album without dynamic range compression was included in the ] for the video game '']'', copies of this version were actively sought out by those who had already purchased the official CD release. The ''Guitar Hero'' version of the album songs exhibit much higher dynamic range and less clipping than those on the CD release, as can be seen from the illustration.<ref name="musicradar_history"> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| | last = Vinnicombe | |||

| | first = Chris | |||

| | title = Death Magnetic Sounds Better in Guitar Hero | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | date = 16 September 2008 | |||

| | url = http://www.musicradar.com/news/guitars/blog-death-magnetic-sounds-better-in-guitar-hero-173961 | |||

| | access-date = 18 September 2008 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| In late 2008, mastering engineer ] offered three versions of the ] album '']'' for approval to co-producers ] and Caram Costanzo. They selected the one with the least compression. Ludwig wrote, "I was floored when I heard they decided to go with my full dynamics version and the loudness-for-loudness-sake versions be damned." Ludwig said the "fan and press backlash against the recent heavily compressed recordings finally set the context for someone to take a stand and return to putting music and dynamics above sheer level."<ref name="Ludwig 2008"> | |||

| However, with the advent of CDs being taken to this level, the concept of making CDs "hotter" began to enter the minds of people within the industry due to how noticeably louder CDs had become than in the past decade. Engineers, musicians and labels developed their own ideas of how much of the peaks could be compromised as some became fascinated with the concept of making a CD louder than another one. During the late '90s, the ethics of simply stopping at a general transparency point were steadily thrown out the window. Of course, while the process was for the most part gradual, some opted to push the format to the limit as soon as the means arose, such as ], whose widely popular album '']'' hit a whopping −8 dB on many of its tracks, something almost completely unheard of, especially in the year it was released (]), as well as Iggy Pop, who in ] assisted in the remix and remaster of the ] album '']'' by his former band ], which to this day is arguably the loudest rock CD ever recorded, hitting a staggering −4 dB in places, and still barely touched by today's standards. Eventually, however, the standards of loudness would reach its limit in the ]. And while some may debate the severity of the loudness war during its humble beginnings in the 1990s, there is little doubt in the minds of the vast majority of audio enthusiasts that nearly all rock and pop CDs released on large corporate labels (and not just RIAA-owned ones; independent metal label Century Media has been stated as being a major offender, for example) in the 21st century are simply unacceptable sound-wise, with −10 dB being the standard for the past several years, very often being pushed to −9 dB (and on some occasions, even a dB or two louder!). Exceptions to today's hot standards are practically non-existant at this point, and the chances of the situation reversing are very slim due to the fact that knowledge of and concern over the loudness war is still mostly exclusive to audio enthusiasts and individuals within the audio field, demographics who make up an extremely small portion of music buyers. | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| | url=http://www.gatewaymastering.com/gateway_LoudnessWars.asp | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090131045144/http://gatewaymastering.com/gateway_LoudnessWars.asp | |||

| | url-status=dead | |||

| | archive-date=31 January 2009 | |||

| | title=Guns 'N Roses: Dynamics and quality win the Loudness Wars | |||

| | last=Ludwig | |||

| | first=Bob | |||

| | author-link=Bob Ludwig | |||

| | date=25 November 2008 | |||

| | work=Loudness Wars | |||

| | publisher=Gateway Mastering | |||

| | access-date=29 March 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| ===2010s=== | |||

| == Interpretations == | |||

| In March 2010, mastering engineer ] organised the first Dynamic Range Day,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dynamicrangeday.co.uk|title=Dynamic Range Day}}</ref> a day of online activity intended to raise awareness of the issue and promote the idea that "Dynamic music sounds better". The day was a success and its follow-ups in the following years have built on this, gaining industry support from companies like ], ], ] and ] as well as engineers like ], Guy Massey and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dynamicrangeday.co.uk/about/ |title=What do Steve Lillywhite, Guy Massey and Bob Ludwig think of Dynamic Range Day? |author=Ian Shepherd |date=14 March 2011 |publisher=DynamicRangeDay.com |access-date=17 September 2014}}</ref> Shepherd cites research showing there is no connection between sales and loudness, and that people prefer more dynamic music.<ref name="loudness-war-vickers"/><ref>{{cite web |author=Earl Vickers |url=http://www.sfxmachine.com/docs/loudnesswar |title=The Loudness War: Background, Speculation and Recommendations - Additional material |access-date=17 November 2020}}</ref> He also argues that file-based ] will eventually render the war irrelevant.<ref>{{cite web |author=Ian Shepherd |url=http://productionadvice.co.uk/ian-shepherd-aes-mexico/ |title=Lust for Level – Audio perception and the battle for great sound |access-date=8 February 2012}}</ref> | |||

| One of the biggest albums of 2013 was ]'s '']'', with many reviews commenting on the album's great sound.<ref>{{cite web |author=Mark Richardson |url= http://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/18028-daft-punk-random-access-memories/ |title=Random Access Memories – Pitchfork Review |website= ] |access-date=6 February 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |author=Melissa Maerz |url=https://ew.com/article/2013/06/25/random-access-memories/ |title=Random Access Memories – Music Review |magazine=Entertainment Weekly |access-date=6 February 2014}}</ref> Mixing engineer ] deliberately chose to use less compression on the project, commenting "We never tried to make it loud and I think it sounds better for it."<ref>{{cite web |author=Michael Gallant |url=http://www.uaudio.com/blog/artist-interview-mic-guzauski/ |title=Mick Guzauski on Mixing Daft Punk |access-date=6 February 2014}}</ref> In January 2014, the album won five Grammy Awards, including Best Engineered Album (Non-Classical).<ref>{{cite news |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-25850644/ |title=Daft Punk get lucky at Grammy Awards | access-date=6 February 2014|date=27 January 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| As stated before, views regarding the impact of the loudness war are heavily subjective. Many hold the opinion that only a handful of albums (such as the ] ] release '']'', a CD with such excessive amounts of high-frequency digital clipping that casual listeners in addition to audio enthusiasts have made complaints against it) are worth considering as examples, while other, more fanatical types believe any CD where digital full scale is frequently utilized (or when mastering processes are used solely to prevent such when attempting the same volume) should be considered unacceptable. Some consider it a minor annoyance, others find themselves completely unable to listen to albums they feel are noticeable victims of loudness-based mastering. | |||

| Analysis in the early 2010s suggests that the loudness trend may have peaked around 2005 and subsequently reduced, with a pronounced increase in ] (both overall and minimum) for albums since 2005.<ref name="SOS_Dynamic_Range" /> | |||

| It can be said that the definable point in which the loudness of a music format can become audibly intrusive on the sound is when the peaks of the pre-processed recording's ] would exceed full scale when amplified to the desired level on more than numerous occasions; in rock music this can be identified by each individual drum beat. The effects that this will have on the sound itself are widely variable and become exponentially more severe the more the sound is pushed over the digital limit, ranging from almost completely transparent in all but the most trained and focused ear, to detrimentally fatiguing for nearly all listeners and listening environments. The "sweet spot" between transparent and unsatisfactory loudness-based mastering is oft identified at the level where the lowest-peaking snare drum (or in some cases the kick drum) transient during a charged rock beat just reaches the threshold where waveform alteration (either via clipping or processing) occurs; many mastering engineers use this as their "golden standard". | |||

| In 2013, mastering engineer ] predicted that the loudness war would be over by mid-2014, claiming that mandatory use of ] by Apple would lead to producers and mastering engineers to turn down the level of their songs to the standard level, or Apple will do it for them. He believed this would eventually result in producers and engineers making more dynamic masters to take account of this factor.<ref>{{cite web |author=Bob Katz |url=http://www.digido.com/forum/announcement/id-6.html |title=The Loudness War Has Been Won: Press Release |access-date=6 February 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Hugh Robjohns |url=http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/feb14/articles/loudness-war.htm |title=The End of the Loudness War? |work=Sound on Sound |access-date=6 February 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Ian Shepherd |url=http://productionadvice.co.uk/has-the-loudness-war-been-won/ |title=Has The Loudness War Been Won? |access-date=6 February 2014|date=24 October 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| Although mastering engineers are the ones who create the hot CDs themselves, many of them proclaim their actions to be forced upon them, often blaming a variety of parties. The most commonly accused is the recording label, who are said to demand CDs of "competitive" playback levels and disallow the release of any disc that is not up to their commercially-oriented ideal of CD loudness and will simply hand the job over to another, usually less experienced mastering engineer if the originally assigned one refuses to perform such a task, concurrently resulting in the defiant engineer being blacklisted by the label and deprived of their potential salary or even their career. Some accuse the artists and/or producers of being ignorant or apathetic of proper recording practices and requesting their CDs be made as loud as possible, while others blame mixing engineers with similar mindsets or lack of experience for compressing or distorting the mix prior to sending it off for mastering. | |||

| ] reissued much of its catalog as part of its ''Full Dynamic Range'' series, intended to counteract the loudness war and ensure that fans hear the music as it was intended.<ref>{{Cite web |last= |title=Earache Records Closes Chapter On "Loudness War" With Full Dynamic Range Vinyl Reissues |url=https://bravewords.com/news/earache-records-closes-chapter-on-loudness-war-with-full-dynamic-range-vinyl-reissues |date=February 21, 2017 |access-date=2022-12-21 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| == Popular Examples == | |||

| ===2020s=== | |||

| Here are some of the more commonly touted examples of excessive loudness-based mastering. These CDs represent some of the most extreme examples of sonic degradation via compression and distortion in popular music: | |||

| By the late 2010s/early 2020s, most major U.S. streaming services began ] audio by default.<ref name="masteringthemix">{{cite web |title=Mastering audio for Soundcloud, iTunes, Spotify, Amazon Music and Youtube |url=https://www.masteringthemix.com/blogs/learn/76296773-mastering-audio-for-soundcloud-itunes-spotify-and-youtube |website=Mastering The Mix |access-date=8 June 2020}}</ref> Target loudness for normalization varies by platform: | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| |+ style="text-align: center;" | Audio normalization per streaming service | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| ! scope="col" | Service !! scope="col" | Loudness (measured in ]) | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| | −13 LUFS<ref name=SageAudio/> | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| | −16 LUFS<ref name=SageAudio>{{cite web |title=Mastering for Streaming: Platform Loudness and Normalization Explained |url=https://www.sageaudio.com/blog/mastering/mastering-for-streaming-platform-loudness-and-normalization-explained.php |website=Sage Audio |access-date=12 October 2022}}</ref> | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| | −14 LUFS<ref name=SageAudio/> | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| |- | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| * ] - '']'' | |||

| | −14 LUFS, −11 and −19 available in premium<ref>{{cite web |title=Help - Loudness normalization - Spotify for Artists |url=https://artists.spotify.com/help/article/loudness-normalization |access-date=12 October 2022}}</ref><ref name="Vice Spotify">{{cite web |last1=Romani |first1=Bruno |title=Why Spotify Lowered the Volume of Songs and Ended Hegemonic Loudness |url=https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/ywgeek/why-spotify-lowered-the-volume-of-songs-and-ended-hegemonic-loudness |website=VICE News |date=28 July 2017 |access-date=8 June 2020}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | −14 (default) or −18 LUFS<ref>{{cite web |last=Shepherd |first=Ian |title=Tidal Loudness |url=https://productionadvice.co.uk/tidal-loudness/ |website=Production Advice |date=17 November 2016 |access-date=5 November 2021 |quote=Over AirPlay, normalisation will be at −18 LUFS, whereas on mobile devices and browsers, all music will be initially be played back at an integrated loudness of −14 LUFS.}}</ref><ref name=SageAudio/> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | ] | |||

| | −14 LUFS<ref>{{cite web|last=Shepherd |first=Ian |title=YouTube Changes Loudness Reference to −14 LUFS |url=https://www.meterplugs.com/blog/2019/09/18/youtube-changes-loudness-reference-to-14-lufs.html |website=MeterPlugs |access-date=5 November 2021 |date=18 September 2019}}</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| Measured LUFS may further vary among streaming services due to differing measurement systems and adjustment algorithms. For example, Amazon, Tidal, and YouTube do not increase the volume of tracks.<ref name=SageAudio/> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == External links == | |||

| Some services do not normalize audio, for example ].<ref name=SageAudio/> | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * (against ]) | |||

| * | |||

| ==Radio broadcasting== | |||

| When music is broadcast over radio, the station applies its own ], further reducing the dynamic range of the material to closely match levels of absolute amplitude, regardless of the original recording's loudness.<ref name="omni"> also available from the </ref> | |||

| Competition for listeners between radio stations has contributed to a loudness war in radio broadcasting.<ref name="radioworld">{{cite web| title=Interview with Inovonics CEO Jim Wood at Radioworld |url=http://www.rwonline.com/reference-room/special-report/03_rwf_wood.shtml| url-status=usurped | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20041104073923/http://www.rwonline.com/reference-room/special-report/03_rwf_wood.shtml |archive-date=4 November 2004 }}</ref> Loudness jumps between television broadcast channels and between programmes within the same channel, and between programs and intervening adverts are a frequent source of audience complaints.<ref>{{citation |publisher=] |title=Loudness in TV Sound |first=Jean Paul |last=Moerman |url=http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=12650 |date=1 May 2004 |quote=We started this paper with viewer complaints. At Belgian National Broadcasters VRT, located in Brussels, about 140 complaints per year were about sound. Since the implementation of the master plan there was a spectacular downfall to 3 complaints in 2003. This demonstrates again the efficiency of the master plan.}}</ref> The ] has addressed this issue in the EBU PLOUD Group with publication of the ] recommendation. In the U.S., legislators passed the ], which led to enforcement of the formerly voluntary ] standard for loudness management. | |||

| ==Criticism== | |||

| In 2007, Suhas Sreedhar published an article about the loudness war in the engineering magazine '']''. Sreedhar said that the greater possible dynamic range of CDs was being set aside in favor of maximizing loudness using digital technology. Sreedhar said that the over-compressed modern music was fatiguing, that it did not allow the music to ''breathe''.<ref name="future_of_music">{{cite web |url=https://spectrum.ieee.org/print/5429 |title=The Future of Music |work=] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071014231310/https://spectrum.ieee.org/print/5429 |archive-date=14 October 2007|date=August 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| The production practices associated with the loudness war have been condemned by recording industry professionals including ] and ],<ref name="Times">{{citation |first=Sherwin |last=Adam |url=http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/music/article1878724.ece |archive-url=https://archive.today/20080511195735/http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/music/article1878724.ece |url-status=dead |archive-date=11 May 2008 |title=Why music really is getting louder |work=The Times |date=7 June 2007 |access-date=12 June 2007}}</ref> along with mastering engineers ], ], and ].<ref name="bigsqueeze" /> Musician ] has also condemned the practice, saying, "You listen to these modern records, they're atrocious, they have sound all over them. There's no definition of nothing, no vocal, no nothing, just like—static."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/5277574.stm|title=Dylan rubbishes modern recordings|access-date=11 July 2019 | work=BBC News | date=23 August 2006}}</ref><ref name="Llewellyn Hinkes-Jones" /> Music critics have complained about excessive compression. The ]–produced albums '']'' and '']'' have been criticised for loudness by '']''; the latter was also criticised by '']''.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.audioholics.com/news/metallica-death-magnetic-sounds-better-on-guitar-hero-iii|title=Metallica Death Magnetic Sounds Better on Guitar Hero III|date=19 September 2008 }}</ref><ref name=guardian2>{{cite news | url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2008/sep/17/death.magnetic.too.loud | title=Was the Metallica album too loud for you? | date=17 September 2008 | first=Dan | last=Martin | newspaper=The Guardian | access-date=26 March 2020 }}</ref> '']'' said the former suffered from so much digital clipping that "even non-audiophile consumers complained about it".{{r|"Stylus"}} | |||

| Opponents have called for immediate changes in the music industry regarding the level of loudness.<ref name="Llewellyn Hinkes-Jones" /> In August 2006, ], the vice-president of ] for One Haven Music (a Sony Music company), in an open letter decrying the loudness war, claimed that mastering engineers are being forced against their will or are preemptively making releases louder to get the attention of industry heads.<ref name="Austin"/> Some bands are being petitioned by the public to re-release their music with less distortion.<ref name="Times" /> | |||

| The nonprofit organization Turn Me Up! was created by ], ], and Allen Wagner in 2007 with the aim of certifying albums that contain a suitable level of dynamic range<ref name="digitalmusic">, ''The Guardian'', 10 January 2008</ref> and encourage the sale of quieter records by placing a Turn Me Up! sticker on certified albums.<ref name="baltimore">{{Cite news|url=https://www.baltimoresun.com/2007/11/25/audio-gain-in-volume-signals-loss-for-listeners/ |title=Audio gain in volume signals loss for listeners |last=Emery |first=Chris |journal=The Baltimore Sun |date=25 November 2007 |access-date=2 September 2010}}</ref> {{as of|2019}}, the group has not produced an objective method for determining what will be certified.<ref>{{cite web |publisher=Turn Me Up! |url=http://www.turnmeup.org/about_us.shtml |title=About Us |access-date=2 January 2019}}</ref> | |||

| A hearing researcher at ] is concerned that the loudness of new albums could possibly harm listeners' hearing, particularly that of children.<ref name="baltimore" /> The ] has published a paper suggesting increasing loudness may be a risk factor in hearing loss.<ref name="forbes">{{Cite news|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/evaamsen/2019/07/30/why-we-dont-turn-down-the-volume-when-the-music-gets-louder/ |title=Why We Don't Turn Down The Volume When The Music Gets Louder |last=Amsen |first=Eva |journal=Forbes |date=30 July 2019 |access-date=5 August 2019}}</ref><ref name="Internal">{{Cite journal|title=Temporal Trends in the Loudness of Popular Music over Six Decades |last=Hourmazd |first=Haghbayan |journal=General Internal Medicine |date=24 July 2019 |volume=35 |issue=1 |pages=394–395 |doi=10.1007/s11606-019-05210-4 |pmid=31342330 |pmc=6957604 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| A two-minute YouTube video addressing this issue by audio engineer Matt Mayfield<ref name="mayfield">{{YouTube | id=3Gmex_4hreQ | title=The Loudness War}}</ref> has been referenced by '']''<ref>, The Wall St. Journal, 25 September 2008</ref> and the '']''.<ref name="chicago_tribune">, ''Chicago Tribune'', 4 January 2008</ref> Pro Sound Web quoted Mayfield, "When there is no quiet, there can be no loud."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.prosoundweb.com/article/video_the_loudness_wars_exposed/ |title=Video: The Loudness Wars Exposed: "When there is no quiet, there can be no loud." |work=Study Hall |publisher=Pro Sound Web |date=30 March 2011 |access-date=4 April 2011}}</ref> | |||

| The book ''Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music'', by Greg Milner, presents the loudness war in radio and music production as a central theme.<ref name=Milner>{{cite book |isbn=9781847086051 |publisher=Granta Publications |title=Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music |first=Greg |last=Milner |date=2012}}</ref> The book ''Mastering Audio: The Art and the Science'', by Bob Katz, includes chapters about the origins of the loudness war and another suggesting methods of combating the war.<ref name=Katz3rd>{{cite book |title=Mastering Audio: The Art and the Science |first=Bob |last=Katz |date=2013 |edition=3rd |publisher=Focal Press |isbn=978-0-240-81896-2}}</ref>{{rp|241}} These chapters are based on Katz's presentation at the 107th Audio Engineering Society Convention (1999) and subsequent ''Audio Engineering Society Journal'' publication (2000).<ref name="Journal Article"> () accessed 24 February 2019.</ref> | |||

| ==Debate== | |||

| In September 2011, Emmanuel Deruty wrote in '']'', a recording industry magazine, that the loudness war has not led to a decrease in dynamic variability in modern music, possibly because the original digitally recorded source material of modern recordings is more dynamic than ] material. Deruty and Tardieu analyzed the ''loudness range'' (LRA) over a 45-year span of recordings and observed that the ] of recorded music diminished significantly between 1985 and 2010, but the LRA remained relatively constant.<ref name="SOS_Dynamic_Range">{{Cite news | last = Deruty | first = Emmanuel | title = 'Dynamic Range' & The Loudness War | work = Sound on Sound | access-date = 24 October 2013 | date = September 2011 | url = http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/sep11/articles/loudness.htm}}</ref> Deruty and Damien Tardieu criticized Sreedhar's methods in an AES paper, saying that Sreedhar had confused crest factor (peak to RMS) with ] (pianissimo to fortissimo).<ref>{{Cite journal |author=Emmanuel Deruty, Damien Tardieu |date=January 2014 |title=About Dynamic Processing in Mainstream Music | journal = Journal of the Audio Engineering Society |volume=62 | issue = 1/2 | pages = 42–55 |doi=10.17743/jaes.2014.0001 }}</ref> | |||

| This analysis was also challenged by ] and Bob Katz on the basis that the LRA was designed for assessing loudness variation within a track while the EBU R128 peak to loudness ratio (PLR) is a measure of the peak level of a track relative to a reference loudness level and is a more helpful metric than LRA in assessing overall perceived dynamic range. PLR measurements show a trend of reduced dynamic range throughout the 1990s.<ref>{{cite web |author=Ian Shepherd |url=http://productionadvice.co.uk/loudness-war-dynamic-range/ |title=Why the Loudness War hasn't reduced 'Loudness Range' |access-date=6 February 2014|date=18 August 2011 }}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |author=Jason Victor Serinus |url=http://www.stereophile.com/content/winning-loudness-wars |title=Winning the Loudness Wars |magazine=Stereophile |access-date=6 February 2014|date=23 November 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| Debate continues regarding which measurement methods are most appropriate to evaluating the loudness war.<ref>{{cite web |author = Esben Skovenborg | publisher = AES 132nd Convention |date=April 2012 |url=http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=16254 |title=Loudness Range (LRA) – Design and Evaluation |access-date=25 October 2014 |url-access=subscription }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author = Jon Boley, Michael Lester and Christopher Danner | publisher = AES 129th Convention |date=November 2010 |url=http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=15601 |title=Measuring Dynamics: Comparing and Contrasting Algorithms for the Computation of Dynamic Range |access-date=25 October 2014|url-access=subscription }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |author=Jens Hjortkjær, Mads Walther-Hansen |date=January 2014 |url=http://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=17085 |title=Perceptual Effects of Dynamic Range Compression in Popular Music Recordings | journal = Journal of the Audio Engineering Society |volume=62 | issue = 1/2 | pages = 42–55 |access-date=6 June 2014|url-access=subscription }}</ref> | |||

| == Examples of loud albums == | |||

| Albums that have been criticized for their sound quality include: | |||

| <!--All entries in this table should include significant coverage in reliable sources--> | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| |- | |||

| !scope="col"| Artist | |||

| !scope="col"| Album | |||

| !scope="col"| Release date | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Stylus" /> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2006|1|23}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref>{{Cite news | url = https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/09/arts/music/black-sabbaths-new-album-13.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&/ | title = Black Sabbath's New Album, '13' | newspaper = The New York Times | date = 7 June 2013 | last1 = Ratliff | first1 = Ben }}</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2013|6|10}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Austin" /> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2006|8|9}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref>{{cite magazine| url = http://thequietus.com/articles/00617-the-cure| title = Review The Cure 4:13 Dream| magazine = The Quietus| first = John| last = Doran| date = 27 September 2008| access-date = 30 June 2011| archive-url = https://archive.today/20120715083240/http://thequietus.com/articles/00617-the-cure| archive-date = 15 July 2012| url-status = dead}}</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2008|10|27}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="2"|] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']'' (2010 remaster)<ref name="DuranRemasters">{{cite magazine| url = https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/jul/15/emi-defends-remastered-duran-albums| title = EMI defends Duran Duran remasters| magazine = The Guardian| first = Sean| last = Michaels| date = 15 July 2010| access-date = 25 July 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | rowspan="2"|{{dts|format=dmy|2010|03|29}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |scope="row"| '']'' (2010 remaster)<ref name="DuranRemasters" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Stylus" /><ref group="note">Won Grammy Award in 2006 for ]</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2006|4|3}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="RollingStoneDeathHiFi">{{cite magazine | last = Levine | first = Robert | url = https://www.rollingstone.com/news/story/17777619/the_death_of_high_fidelity/print | title = The Death of High Fidelity: In the age of MP3s, sound quality is worse than ever | magazine = Rolling Stone | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080701220047/http://www.rollingstone.com/news/story/17777619/the_death_of_high_fidelity/print | archive-date = 1 July 2008 | url-status = dead | access-date = 1 December 2010 }}</ref><ref group=note>The 2015 remaster of this compilation does not have the same quality issues.</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2007|11|12}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="RollingStoneDeathHiFi" /> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2006|7|13}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Austin" /> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2006|7|18}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref>{{cite magazine | url = https://www.rollingstone.com/rockdaily/index.php/2008/10/01/metallica-faces-criticism-over-sound-quality-of-death-magnetic/ | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081002211017/http://www.rollingstone.com/rockdaily/index.php/2008/10/01/metallica-faces-criticism-over-sound-quality-of-death-magnetic/ | url-status = dead | archive-date = 2 October 2008 | title = Metallica Face Criticism Over Sound Quality of 'Death Magnetic' | magazine = Rolling Stone }}</ref><ref>{{cite news | last = Smith | first = Ethan | url = https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB122228767729272339 | title = Even Heavy-Metal Fans Complain That Today's Music Is Too Loud!!! | newspaper = The Wall Street Journal }}</ref><ref group=note>The '']'' version and 2015 remaster of this album do not have the same quality issues.</ref>{{r|guardian2}} | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2008|09|12}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Miranda Lambert - Revolution |url=http://www.countryweekly.com/miranda_lambert/reviews/737 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091030004000/http://www.countryweekly.com/miranda_lambert/reviews/737 |archive-date=2009-10-30 |magazine=] |date=19 October 2009}}</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2009|09|29}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Stylus" /> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|1995|10|2}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref>{{Cite news | url = https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2008/jan/10/digitalmusic| title = Will the loudness wars result in quieter CDs? | newspaper = The Guardian | first = Tim | last = Anderson | date = 10 January 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2007|6|4}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Anderson">Anderson, Tim (18 January 2007). Retrieved on 12 March 2012.</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2006|5|9}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Stylus" /> || {{dts|format=dmy|2002|08|27}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''{{r|guardian2}}<ref name="Stylus" /> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|1999|06|08}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref name="Anderson"/><ref group=note>The 2013 remix & remaster of this album does not have the same quality issues.</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2002|05|14}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']'' (1997 remix & remaster)<ref name="Anderson" /> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|1997|4|22}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |scope="row"| '']''<ref>{{cite magazine |author=Matt Medved |url=https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/code/6538870/taylor-swift-1989-louder-acdc-back-in-black |title=Taylor Swift's '1989' Is Louder Than AC/DC's 'Back in Black' – Here's Why |magazine=] |access-date=29 March 2018}}</ref> | |||

| | {{dts|format=dmy|2014|10|27}} | |||

| |} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=20em}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{Reflist|group=note}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist|refs= | |||

| <ref name="Llewellyn Hinkes-Jones">{{cite magazine |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2013/11/the-real-reason-musics-gotten-so-loud/281707/ |title=The Real Reason Music's Gotten So Loud |author=Llewellyn Hinkes-Jones |date=2013-11-25 |magazine=]}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Stuart Dredge">{{cite news |title=Pop music is louder, less acoustic and more energetic than in the 1950s |url=https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/nov/25/pop-music-louder-less-acoustic |newspaper=] |author=Stuart Dredge |date=25 November 2013 |access-date=25 November 2013}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{citation |url=http://tech.ebu.ch/docs/techreview/trev_310-lund.pdf |title=Level and distortion in digital broadcasting |author=Thomas Lund |date=April 2007 |publisher=EBU}} | |||

| * {{citation |url=http://tech.ebu.ch/docs/techreview/trev_2010-Q3_loudness_Camerer.pdf |title=On the way to Loudness Nirvana – Audio levelling with EBU R 128 |author=Florian Camerer |date=2010 |publisher=EBU}} | |||

| * {{Cite news |title=Pop music too loud and all sounds the same: official |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-science-music-idUSBRE86P0R820120726 |date=26 July 2012 |last=Wickham |first=Chris|work=Reuters }} | |||

| * {{cite journal |date=26 July 2012 |title=Measuring the Evolution of Contemporary Western Popular Music |journal=Scientific Reports |volume=2 |page= 521|arxiv=1205.5651 |pmid= 22837813|pmc= 3405292|bibcode=2012NatSR...2E.521S |doi=10.1038/srep00521 | last1 = Serrà | first1 = J | last2 = Corral | first2 = A | last3 = Boguñá | first3 = M | last4 = Haro | first4 = M | last5 = Arcos | first5 = JL}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal | last1 = Devine | first1 = K. | title = Imperfect sound forever: Loudness wars, listening formations and the history of sound reproduction | doi = 10.1017/S0261143013000032 | journal = Popular Music | volume = 32 | issue = 2 | pages = 159–176 | year = 2013 | s2cid = 162636724 | url = http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/3883/1/Devine-LoudnessWars-PopularMusic-Final.pdf | hdl = 10852/59847 | hdl-access = free }} | |||

| * {{citation |url=https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/popmusicforum_articles/1/ |title=Song Dynamics, the Chiaroscuro of Loudness in Selected Pop/Rock Recordings, 1971-2021 |author=Robert Toft |date=2023 |publisher=Popular Music Forum, Western University}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Music production}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Loudness War}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 12:22, 8 January 2025

Increasing levels in recorded music

The loudness war (or loudness race) is a trend of increasing audio levels in recorded music, which reduces audio fidelity and—according to many critics—listener enjoyment. Increasing loudness was first reported as early as the 1940s, with respect to mastering practices for 7-inch singles. The maximum peak level of analog recordings such as these is limited by varying specifications of electronic equipment along the chain from source to listener, including vinyl and Compact Cassette players. The issue garnered renewed attention starting in the 1990s with the introduction of digital signal processing capable of producing further loudness increases.

With the advent of the compact disc (CD), music is encoded to a digital format with a clearly defined maximum peak amplitude. Once the maximum amplitude of a CD is reached, loudness can be increased still further through signal processing techniques such as dynamic range compression and equalization. Engineers can apply an increasingly high ratio of compression to a recording until it more frequently peaks at the maximum amplitude. In extreme cases, efforts to increase loudness can result in clipping and other audible distortion. Modern recordings that use extreme dynamic range compression and other measures to increase loudness therefore can sacrifice sound quality to loudness. The competitive escalation of loudness has led music fans and members of the musical press to refer to the affected albums as "victims of the loudness war".

History

The practice of focusing on loudness in audio mastering can be traced back to the introduction of the compact disc, but also existed to some extent when the vinyl phonograph record was the primary released recording medium and when 7-inch singles were played on jukebox machines in clubs and bars. The so-called wall of sound (not to be confused with the Phil Spector Wall of Sound) formula preceded the loudness war, but achieved its goal using a variety of techniques, such as instrument doubling and reverberation, as well as compression.

Jukeboxes became popular in the 1940s and were often set to a predetermined level by the owner, so any record that was mastered louder than the others would stand out. Similarly, starting in the 1950s, producers would request louder 7-inch singles so that songs would stand out when auditioned by program directors for radio stations. In particular, many Motown records pushed the limits of how loud records could be made; according to one of their engineers, they were "notorious for cutting some of the hottest 45s in the industry." In the 1960s and 1970s, compilation albums of hits by multiple different artists became popular, and if artists and producers found their song was quieter than others on the compilation, they would insist that their song be remastered to be competitive.

Because of the limitations of the vinyl format, the ability to manipulate loudness was also limited. Attempts to achieve extreme loudness could render the medium unplayable. One example was the hot master of Led Zeppelin II by mastering engineer Bob Ludwig which caused some cartridges to mistrack; the album was recalled and issued with lower compression levels. Digital media such as CDs remove these restrictions and as a result, increasing loudness levels have been a more severe issue in the CD era. Modern computer-based digital audio effects processing allows mastering engineers to have greater direct control over the loudness of a song: for example, a brick-wall limiter can look ahead at an upcoming signal to limit its level.

1980s

Since CDs were not the primary medium for popular music until the late 1980s, there was little motivation for competitive loudness practices then. The common practice of mastering music for CD involved matching the highest peak of a recording at, or close to, digital full scale, and referring to digital levels along the lines of more familiar analog VU meters. When using VU meters, a certain point (usually −14 dB below the disc's maximum amplitude) was used in the same way as the saturation point (signified as 0 dB) of analog recording, with several dB of the CD's recording level reserved for amplitude exceeding the saturation point (often referred to as the red zone, signified by a red bar in the meter display), because digital media cannot exceed 0 decibels relative to full scale (dBFS). The average RMS level of the average rock song during most of the decade was around −16.8 dBFS.

1990s

By the early 1990s, mastering engineers had learned how to optimize for the CD medium and the loudness war had not yet begun in earnest. However, in the early 1990s, CDs with louder music levels began to surface, and CD levels became more and more likely to bump up to the digital limit, resulting in recordings where the peaks on an average rock or beat-heavy pop CD hovered near 0 dBFS, but only occasionally reached it.

The concept of making music releases hotter began to appeal to people within the industry, in part because of how noticeably louder some releases had become and also in part because the industry believed that customers preferred louder-sounding CDs, even though that may not have been true. Engineers, musicians, and labels each developed their own ideas of how CDs could be made louder. In 1994, the first digital brick-wall limiter with look-ahead (the Waves L1) was mass-produced; this feature, since then, has been commonly incorporated in digital mastering limiters and maximizers. While the increase in CD loudness was gradual throughout the 1990s, some opted to push the format to the limit, such as on Oasis's widely popular album (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, whose RMS level averaged −8 dBFS on many of its tracks—a rare occurrence, especially in the year it was released (1995). Red Hot Chili Peppers's Californication (1999) represented another milestone, with prominent clipping occurring throughout the album.

2000s

By the early 2000s, the loudness war had become fairly widespread, especially with some remastered re-releases and greatest hits collections of older music. In 2008, loud mastering practices received mainstream media attention with the release of Metallica's Death Magnetic album. The CD version of the album has a high average loudness that pushes peaks beyond the point of digital clipping, causing distortion. This was reported by customers and music industry professionals, and covered in multiple international publications, including Rolling Stone, The Wall Street Journal, BBC Radio, Wired, and The Guardian. Ted Jensen, a mastering engineer involved in the Death Magnetic recordings, criticized the approach employed during the production process. When a version of the album without dynamic range compression was included in the downloadable content for the video game Guitar Hero III, copies of this version were actively sought out by those who had already purchased the official CD release. The Guitar Hero version of the album songs exhibit much higher dynamic range and less clipping than those on the CD release, as can be seen from the illustration.

In late 2008, mastering engineer Bob Ludwig offered three versions of the Guns N' Roses album Chinese Democracy for approval to co-producers Axl Rose and Caram Costanzo. They selected the one with the least compression. Ludwig wrote, "I was floored when I heard they decided to go with my full dynamics version and the loudness-for-loudness-sake versions be damned." Ludwig said the "fan and press backlash against the recent heavily compressed recordings finally set the context for someone to take a stand and return to putting music and dynamics above sheer level."

2010s

In March 2010, mastering engineer Ian Shepherd organised the first Dynamic Range Day, a day of online activity intended to raise awareness of the issue and promote the idea that "Dynamic music sounds better". The day was a success and its follow-ups in the following years have built on this, gaining industry support from companies like SSL, Bowers & Wilkins, TC Electronic and Shure as well as engineers like Bob Ludwig, Guy Massey and Steve Lillywhite. Shepherd cites research showing there is no connection between sales and loudness, and that people prefer more dynamic music. He also argues that file-based loudness normalization will eventually render the war irrelevant.

One of the biggest albums of 2013 was Daft Punk's Random Access Memories, with many reviews commenting on the album's great sound. Mixing engineer Mick Guzauski deliberately chose to use less compression on the project, commenting "We never tried to make it loud and I think it sounds better for it." In January 2014, the album won five Grammy Awards, including Best Engineered Album (Non-Classical).

Analysis in the early 2010s suggests that the loudness trend may have peaked around 2005 and subsequently reduced, with a pronounced increase in dynamic range (both overall and minimum) for albums since 2005.

In 2013, mastering engineer Bob Katz predicted that the loudness war would be over by mid-2014, claiming that mandatory use of Sound Check by Apple would lead to producers and mastering engineers to turn down the level of their songs to the standard level, or Apple will do it for them. He believed this would eventually result in producers and engineers making more dynamic masters to take account of this factor.

Earache Records reissued much of its catalog as part of its Full Dynamic Range series, intended to counteract the loudness war and ensure that fans hear the music as it was intended.

2020s

By the late 2010s/early 2020s, most major U.S. streaming services began normalizing audio by default. Target loudness for normalization varies by platform:

| Service | Loudness (measured in LUFS) |

|---|---|

| Amazon Music | −13 LUFS |

| Apple Music | −16 LUFS |

| SoundCloud | −14 LUFS |

| Spotify | −14 LUFS, −11 and −19 available in premium |

| Tidal | −14 (default) or −18 LUFS |

| YouTube | −14 LUFS |

Measured LUFS may further vary among streaming services due to differing measurement systems and adjustment algorithms. For example, Amazon, Tidal, and YouTube do not increase the volume of tracks.

Some services do not normalize audio, for example Bandcamp.

Radio broadcasting

When music is broadcast over radio, the station applies its own signal processing, further reducing the dynamic range of the material to closely match levels of absolute amplitude, regardless of the original recording's loudness.

Competition for listeners between radio stations has contributed to a loudness war in radio broadcasting. Loudness jumps between television broadcast channels and between programmes within the same channel, and between programs and intervening adverts are a frequent source of audience complaints. The European Broadcasting Union has addressed this issue in the EBU PLOUD Group with publication of the EBU R 128 recommendation. In the U.S., legislators passed the CALM act, which led to enforcement of the formerly voluntary ATSC A/85 standard for loudness management.

Criticism

In 2007, Suhas Sreedhar published an article about the loudness war in the engineering magazine IEEE Spectrum. Sreedhar said that the greater possible dynamic range of CDs was being set aside in favor of maximizing loudness using digital technology. Sreedhar said that the over-compressed modern music was fatiguing, that it did not allow the music to breathe.

The production practices associated with the loudness war have been condemned by recording industry professionals including Alan Parsons and Geoff Emerick, along with mastering engineers Doug Sax, Stephen Marcussen, and Bob Katz. Musician Bob Dylan has also condemned the practice, saying, "You listen to these modern records, they're atrocious, they have sound all over them. There's no definition of nothing, no vocal, no nothing, just like—static." Music critics have complained about excessive compression. The Rick Rubin–produced albums Californication and Death Magnetic have been criticised for loudness by The Guardian; the latter was also criticised by Audioholics. Stylus Magazine said the former suffered from so much digital clipping that "even non-audiophile consumers complained about it".

Opponents have called for immediate changes in the music industry regarding the level of loudness. In August 2006, Angelo Montrone, the vice-president of A&R for One Haven Music (a Sony Music company), in an open letter decrying the loudness war, claimed that mastering engineers are being forced against their will or are preemptively making releases louder to get the attention of industry heads. Some bands are being petitioned by the public to re-release their music with less distortion.

The nonprofit organization Turn Me Up! was created by Charles Dye, John Ralston, and Allen Wagner in 2007 with the aim of certifying albums that contain a suitable level of dynamic range and encourage the sale of quieter records by placing a Turn Me Up! sticker on certified albums. As of 2019, the group has not produced an objective method for determining what will be certified.

A hearing researcher at House Ear Institute is concerned that the loudness of new albums could possibly harm listeners' hearing, particularly that of children. The Journal of General Internal Medicine has published a paper suggesting increasing loudness may be a risk factor in hearing loss.

A two-minute YouTube video addressing this issue by audio engineer Matt Mayfield has been referenced by The Wall Street Journal and the Chicago Tribune. Pro Sound Web quoted Mayfield, "When there is no quiet, there can be no loud."

The book Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music, by Greg Milner, presents the loudness war in radio and music production as a central theme. The book Mastering Audio: The Art and the Science, by Bob Katz, includes chapters about the origins of the loudness war and another suggesting methods of combating the war. These chapters are based on Katz's presentation at the 107th Audio Engineering Society Convention (1999) and subsequent Audio Engineering Society Journal publication (2000).

Debate

In September 2011, Emmanuel Deruty wrote in Sound on Sound, a recording industry magazine, that the loudness war has not led to a decrease in dynamic variability in modern music, possibly because the original digitally recorded source material of modern recordings is more dynamic than analogue material. Deruty and Tardieu analyzed the loudness range (LRA) over a 45-year span of recordings and observed that the crest factor of recorded music diminished significantly between 1985 and 2010, but the LRA remained relatively constant. Deruty and Damien Tardieu criticized Sreedhar's methods in an AES paper, saying that Sreedhar had confused crest factor (peak to RMS) with dynamics in the musical sense (pianissimo to fortissimo).

This analysis was also challenged by Ian Shepherd and Bob Katz on the basis that the LRA was designed for assessing loudness variation within a track while the EBU R128 peak to loudness ratio (PLR) is a measure of the peak level of a track relative to a reference loudness level and is a more helpful metric than LRA in assessing overall perceived dynamic range. PLR measurements show a trend of reduced dynamic range throughout the 1990s.

Debate continues regarding which measurement methods are most appropriate to evaluating the loudness war.

Examples of loud albums

Albums that have been criticized for their sound quality include:

| Artist | Album | Release date |

|---|---|---|

| Arctic Monkeys | Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not | 23 January 2006 |

| Black Sabbath | 13 | 10 June 2013 |

| Christina Aguilera | Back to Basics | 9 August 2006 |

| The Cure | 4:13 Dream | 27 October 2008 |

| Duran Duran | Duran Duran (2010 remaster) | 29 March 2010 |

| Seven and the Ragged Tiger (2010 remaster) | ||

| The Flaming Lips | At War with the Mystics | 3 April 2006 |

| Led Zeppelin | Mothership | 12 November 2007 |

| Lily Allen | Alright, Still | 13 July 2006 |

| Los Lonely Boys | Sacred | 18 July 2006 |

| Metallica | Death Magnetic | 12 September 2008 |

| Miranda Lambert | Revolution | 29 September 2009 |

| Oasis | (What's the Story) Morning Glory? | 2 October 1995 |

| Paul McCartney | Memory Almost Full | 4 June 2007 |

| Paul Simon | Surprise | 9 May 2006 |

| Queens of the Stone Age | Songs for the Deaf | 27 August 2002 |

| Red Hot Chili Peppers | Californication | 8 June 1999 |

| Rush | Vapor Trails | 14 May 2002 |

| The Stooges | Raw Power (1997 remix & remaster) | 22 April 1997 |

| Taylor Swift | 1989 | 27 October 2014 |

See also

- Alignment level

- Audio noise measurement

- Audio system measurements

- Fader creep

- Headroom

- Loudness monitoring

- Needle drop

- Overproduction

- Pitch inflation

- Up to eleven

Notes

- Up to 2 or 4 consecutive full-scale samples was considered acceptable.

- Usually in the range of −3 dB.

- Look-ahead is a window of time in which the processor analyzes the audio amplitude in advance and predicts the amount of gain reduction needed to meet the requested output level (0 dBFS); this permits the limiter to react to incoming transients avoiding clipping. Since an audio buffer is needed to achieve this, look-ahead is only possible in the digital domain and introduces a small amount of latency to the output signal.

- Won Grammy Award in 2006 for Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical

- The 2015 remaster of this compilation does not have the same quality issues.

- The Guitar Hero version and 2015 remaster of this album do not have the same quality issues.

- The 2013 remix & remaster of this album does not have the same quality issues.

References

- ^ "The Loudness Wars: Why Music Sounds Worse". NPR. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- Milner, Greg (7 February 2019). "They Really Don't Make Music Like They Used To". The New York Times.

- Stuart Dredge (25 November 2013). "Pop music is louder, less acoustic and more energetic than in the 1950s". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2013.